Abstract

Background

Worldwide, physical inactivity (PIA) and sedentary behavior (SB) are recognized as significant challenges hindering the achievement of the United Nations (UN) sustainable development goals (SDGs). PIA and SB are responsible for 1.6 million deaths attributed to non-communicable diseases (NCDs). The World Health Organization (WHO) has urged governments to implement interventions informed by behavioral theories aimed at reducing PIA and SB. However, limited attention has been given to the range of theories, techniques, and contextual conditions underlying the design of behavioral theories. To this end, we set out to map these interventions, their levels of action, their mode of delivery, and how extensively they apply behavioral theories, constructs, and techniques.

Methods

Following the scoping review methodology of Arksey and O’Malley (2005), we included peer-reviewed articles on behavioral theories interventions centered on PIA and SB, published between 2010 and 2023 in Arabic, French, and English in four databases (Scopus, Web of Science [WoS], PubMed, and Google Scholar). We adopted a framework thematic analysis based on the upper-level ontology of behavior theories interventions, Behavioral theories taxonomies, and the first version (V1) taxonomy of behavior change techniques(BCTs).

Results

We included 29 studies out of 1,173 that were initially screened/searched. The majority of interventions were individually focused (n = 15). Few studies have addressed interpersonal levels (n = 6) or organizational levels (n = 6). Only two interventions can be described as systemic (i.e., addressing the individual, interpersonal, organizational, and institutional factors)(n = 2). Most behavior change interventions use four theories: The Social cognitive theory (SCT), the socioecological model (SEM), SDT, and the transtheoretical model (TTM). Most behavior change interventions (BCIS) involve goal setting, social support, and action planning with various degrees of theoretical use (intensive [n = 15], moderate [n = 11], or low [n = 3]).

Discussion and conclusion

Our review suggests the need to develop systemic and complementary interventions that entail the micro-, meso- and macro-level barriers to behavioral changes. Theory informed BCI need to integrate synergistic BCTs into models that use micro-, meso- and macro-level theories to determine behavioral change. Future interventions need to appropriately use a mix of behavioral theories and BCTs to address the systemic nature of behavioral change as well as the heterogeneity of contexts and targeted populations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12889-024-19600-9.

Keywords: Sedentary behavior, Physical inactivity, Behavioral change theories, Behavior change techniques, Workplace, Non-communicable diseases

Background

Currently, physical inactivity (PIA) and sedentary behavior (SB) are considered global health challenges hampering the achievement of the United Nations' (UN) third sustainable development goal (SDG). PIA and SB are responsible for 1.6 million deaths per year (27% due to diabetes and 20% due to cardiovascular disease [CVD]) [1]. More than 31% of premature deaths attributed to non-communicable diseases (NCDs) occur in physically inactive populations and are responsible for US $54 billion per year of direct care costs and US $14 billion per year of indirect costs (i.e., a loss of productivity) [1].

It is important to differentiate between three unique concepts: physical activity (PA), PIA, and SB. The WHO defines PA as “any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that requires energy expenditure.” The WHO defines PIA as any activity below the threshold of 150 min per week of moderate or vigorous PA. SB is defined as any waking behavior that leads a person to consume 1.5 metabolic equivalents or less (e.g., sitting, reclining, or lying down) [2].

A recent meta-analysis revealed that prolonged SB is associated with an elevated risk of morbidity and mortality from NCDs. This risk can be reduced or even eliminated by engaging in PA. However, if SB is very high (SB time exceeding 7 h) the risk of mortality and morbidity from NCDs is independent of the level of PA [3]. Both PIA and SB carry a high risk of developing an NCD. PIA is a major risk factor for CVD [4], type 2 diabetes [5], high blood pressure [6], cancer [7] and drug use [8]. However, SB is associated with a 30% increase in CVD [9] as well as a 55% increase in the risk of endometrial cancer [10] and elevated blood pressure [11]. These risks are exacerbated when combined with insufficient PA [12]. Thus, interventions aimed at reducing PIA and SB are estimated to reduce the risk of CVD, type 2 diabetes, depression, and cancer by 35%, 40%, and 35%, respectively [1].

In recent years, increased attention has been given to designing combined interventions, targeting both PIA and SB, to appropriately prevent and contribute to the management of NCDs for better health and well-being outcomes [13]. These interventions need to involve behavioral changes and to be informed by behavioral theories according to the WHO and other global health institutions, communities of researchers, practitioners, and policymakers [14–17].

Behavioral theories and Behavior Change Techniques (BCT)

Behavioral theories explain why, when, and how an individual behavior does (or does not) occur. They highlight that the mechanism of change at play, if targeted, will alter the behavior at the individual, interpersonal, or community level. These mechanisms are central to the design of theory-informed behavior change interventions (BCI) [19], which are complex social adaptive systems (e.g., multiple health behavioral change interventions (BCIs) targeting simultaneously or sequentially two or more health behaviors, that comprise interacting components and sensitivity to context, with emergent intended and unintended effects at different levels: the individual, interpersonal, community (organizational, environmental, national, and global) levels [20–23].

According to Hayden [24], behavioral theories can be classified into three categories based on their levels of action: 1) Intrapersonal or individual-level theories focus on personal determinants that influence behavior (e.g., knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and motivation). Examples include the health belief model (HBM) (Hoch, Baum 1958; [25], the theory of planned behavior (TPB) [26], and self-determination theory (SDT) [27]. 2) Interpersonal level theories highlight the influence of others in shaping one’s behavior; social cognitive theory (SCT) [28] is the most commonly used interpersonal-level theory. 3) Community-level theories aim to affect or modify the social systems within which actors interact. These social systems include organizations institutions, and public policies, among others. Examples of community-level theories include diffusion of innovation theory (Valente & Rogers, 1995) [29] and the social ecological model (SEM) [30].

In practice, behavioral theories are translated into BCIs; these are implemented through the use of BCTs, which are interactive, reproducible elements of an intervention that facilitate the alteration of the mechanism of change or the causal pathway toward the intended behavioral outcome [31, 32].

Recent research has urged scholars to place more emphasis on understanding how and in which context a BCI addressing PIA or SB will lead to desired or unexpected outcomes and impacts [33]. However, the answer remains elusive. To close this gap, we aimed to map out the different types of BCIs geared toward PIA and SB and their underlying theories and techniques. We focused on mapping out different interventions to reduce PIA and SB and identified the underlying behavioral theories and BCTs used. We also aimed to assess the extent of behavioral theories use in the design of BCIs. Our review will provide decision-makers and behavioral designers with a unique systematic and comprehensive mapping of BCI targeting PA and SB using behavioral change theories, tools, and techniques.

Methods

We adopted the scoping review methodology as defined by Arksey and O’Malley [34] and refined by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) [35].

Specifying the review question

During different research team meetings, we iteratively refined our review question as follows: What are the different behavioral theories and BCTs used in theory-informed interventions focused on PIA and SB? To construct a suitable search strategy, we employed the health behavior, health context, exclusion, models, and theories (BeHEMoth) framework [36, 37] (see Table 1), which is especially relevant for identifying interventions based on behavioral theories. We then followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) reporting guidelines to report the results of our scoping review [38].

Table 1.

The BeHEMoth framework

| Health behavior | Sedentary behavior OR Physical inactivity |

|---|---|

| Health context | "Behavioral change intervention" OR "best buys" OR "best practices" OR "behavioral change" |

| Exclusion | Clinical interventions (primary use of medication and clinical treatment), interventions addressing other types of health behaviors such as nutrition, smoking, and sleep) |

| Moth models and theories |

"Logic model" "Theory of change" "Outcome of change" “Program* theory” “Program*logic” "Logical framework" |

We included only interventions addressing PIA and SB or both. We excluded interventions adressing other health behaviors such as,nutrition, smoking, and sleep (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Inclusion criteria for the population, concept, and context models

| Population | General population, including healthy and unhealthy children, adults, women, and elderly people |

|---|---|

| Concept | Theory based Behavioral change interventions implemented in real-world settings addressing SB, PIA/PA, or both |

| Context | Healthcare |

Search strategy

We searched four databases (Scopus, Web of Science [WoS], PubMed, and Google Scholar) (see Supplementary file 1 and Table 2). We manually searched for gray literature on institutional sites and used reference tracking to identify additional papers. We combined search terms for theories (“Logic model” OR “Theory of change” OR “Outcome of change” OR “Program* theory” OR "Program*logic" OR “Logical framework” AND “Behavioral change intervention”) with search terms addressing BCIs: “Behavioral change interventions” AND keywords for “physical activity” OR “sedentary” OR “physical inactivity” OR “exercise” OR “fitness.”

Study selection

The study selection was carried out by two researchers, HK and ZB. We included only empirical studies of interventions addressing SB, PIA, or PA that explicitly used behavioral theories in the context of healthcare. Table 2 guided the definition of our inclusion criteria using the PCC (population, concept, context) framework (JBI) [35]. We included papers published in French, English, and Arabic between January 2010 and November 2023. All study designs were included. We excluded reviews, study protocols, feasibility studies, books, book chapters, commentaries, and letters to editors (See supplementary file 2).

Data charting

Data extraction was guided by, and adapted from the Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Review of Interventions for describing the characteristics of interventions [39] (see Table 3). We first extracted data about the general characteristics of the included studies (author, year, country, type of article, study population). Then, we extracted data about the following characteristics of behavioral theories -informed interventions: 1) theories, models or conceptual frameworks; 2) types of interventions; 3) behavioral theories; 4) BCTs; 5) targeted behavior (SB, PIA, PA, or both); and 6) level of intervention (individual, interpersonal, and environmental) (see supplementary file 3).

Table 3.

Data charting form adapted from Higgins et al. (2019)

| Author name(s), journal, year |

| Study design |

| Unit of analysis |

| Sampling method(s) |

| Types of interventions: organizational, professional, or educational |

| Participants’ characteristics: profession, administrative position, level of training, clinical specialty, age, time since graduation |

| Settings: location, country, district level primary or secondary level, rural of urban area |

| Intervention characteristics |

| A. Country/Year/Duration of the program/Frequency |

| B. Program components/Underlying theory of change/BCT used |

Data analysis, coding and synthesis

BCI

As we aimed to identify the underlying behavioral theories and BCTs used to inform the design of BCIs, we employed a BCI upper-level ontology [40] that coded different forms of BCIs. This taxonomy provides a helpful model for systematically and uniformly describing the upper-level components of BCIs; this enabled us to describe BCIs based on theory and to create a map of the different contexts, BCI content, mode of delivery, and BCI outcomes (see Table 4 and supplementary file 4).

Table 4.

Thematic analysis, coding using different taxonomies of BCT interventions, theories, and techniques

| Label | Description | Taxonomy used |

|---|---|---|

| Context | An aggregate of entities that is independent of the intervention but may influence the effect of a BCT intervention on its outcome behavior | Intervention characteristics using the Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews of Interventions |

| Mode of delivery | An attribute of delivery that is the physical or informational medium through which a BCI is provided. This includes informational and environmental change versus somatic alteration (individual versus group-based, unit-directional versus interactional, synchronous versus asynchronous, push versus pull, gamification and arts features) | The ontology of modes of delivery developed by Marques [41] |

| Content of BCIs | A planned process that is part of a BCI and is intended to be causally active in influencing the outcome behavior. This includes BCTs and behavioral change techniques | The upper-level ontology developed by Michie [40] |

| Behavioral theories | This comprises a comprehensive description of the definition of a theories, interest, use, the context of theory development, and related constructs based on the ABC book of behavior theories | The taxonomy of behavior theories proposed by Michie et al. [19] and refined by JBI (2019) |

| Behavioral change techniques | A behavioral change technique is described as an “observable, replicable, and irreducible component of an intervention designed to alter or redirect causal processes that regulate behavior, that is, a technique that is proposed to be an active ingredient” [104] | V1 taxonomy of behavioral change techniques developed by Michie et al. [104] |

Mode of delivery

We coded the different modes of delivery using the taxonomy developed by [41].

Behavioral theories

To comprehensively describe the theories used to inform the design of interventions, we used the taxonomy of behavioral theories developed by Michie [19] and we refined it based on Hayden [24]. This taxonomy outlines key behavioral theory constructs (definitions, interest, use, the context of theory development).

We further assessed the intensity and degree of theory use in BCIs (an analysis of how interventions have actually been implemented according to the stated theory) as developed by Michie, 2010 [42] and refined by Bluethmann, 2017 [43] to fit the context of PA. This taxonomy included the following criteria: 1) a theory was mentioned, 2) relevant constructs were targeted, 3) each intervention technique was explicitly linked to at least one theoretical construct, 4) participants were selected or screened based on prespecified criteria (e.g., a construct or predictor), 5) interventions were tailored to different subgroups, 6) at least one construct or theory mentioned in relation to the intervention was measured post-intervention, 7) all measures of theory were presented with some evidence of their reliability, and 8) the results were discussed in relation to the theory.

The most prevalent theories are the transtheoretical model (TTM) of change [44], the TPB [26], SCT [28], information motivation behavior (IMB) [45], the HBM [46], SDT [27], and the health action process approach (HAPA) [19, 47].

Behavioral change techniques (BCTs)

We finally coded the BCTs using the V1 taxonomy [31]. The taxonomy of BCTs synthesizes 93 BCTs classified into 16 domains: 1) goals and planning, 2) feedback and monitoring, 3) social support, 4) shaping knowledge, 5) natural consequences, 6) comparison of behavior, 7) associations, 8) repetition and substitution, 9) comparison of outcomes, 10) rewards and threats, 11) regulation, 12) antecedents, 13) identity, 14) scheduled consequences, 15) self-belief, and 16) covert learning.

Results

Search results

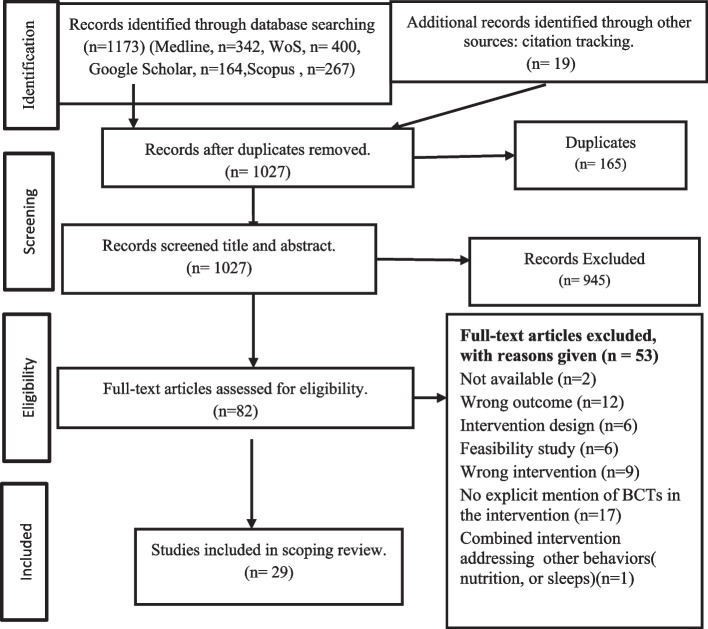

As indicated in Fig. 1, we identified a total of 1,173 studies during systematic searches in four electronic databases. After removing duplicates (n = 165), we screened 1,027 articles for eligibility. We excluded 945 studies during the title and abstract screening. We extracted and analyzed 82 full-text studies for eligibility and excluded 53 (see the reasons for exclusion in Fig. 1 and Supplementary File 2). We screened the reference lists of the included studies for additional relevant articles (n = 19). We finally included a total of 29 articles.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flowchart

In the following paragraphs, we describe the general characteristics of the included studies, the features of theory-informed BCIs (the intervention model, behavioral theories, and BCTs), and the extent of theory use in the included studies.

General characteristics of the included studies

Most of the included studies were carried out in high-income countries (n = 23): the US (n = 5) [48–52], the UK (n = 5) [53–56], Australia (n = 3) [57–59], Belgium (n = 3) [60–62], the Netherlands (n = 2) [63, 64], Canada (n = 2) [65, 66], Jordan (n = 2) [67, 68], Iran (n = 2) [69, 70], Italy (n = 1) [71], Qatar (n = 1) [72], Portugal (n = 1) [73], Spain (n = 1) [74], and Germany (n = 1) [75].

Intervention duration

The duration of the BCIs varied from six weeks to three years. Most interventions were carried out in a short period, ranging from one to four months (n = 14); others lasted five to six months (n = 7). Only six interventions lasted over twelve months (n = 6) (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Generals characteristics of included studies

| Types of interventions | First Author's, year | Study type | Country | Targeted populations | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical activity intervention | Alsaleh 2016 [68] | M-RCTc | Jordan | Jordanian outpatients with CHD | 6 months |

| Alsaleh, 2023 [67] | RCT | Jordan | Students at a Jordanian University | 6 months | |

| Corella,2019 [74] | QES | Spain | University students | 20 Weeks | |

| Krebs, 2020 [75] | RCT | Germany | Employees German automotive industry | 09 weeks (Follow up 10 W, 6,12 M) | |

| Liu JYW, 2023 [55] | Cluster RCT | UK | Frail older adults | 16-weeks | |

| Mahmoudi, 2020 [70] | QES | Iran | Airport Employees | 10 months | |

| Plotnikoff, RC, 2013 [65] | RCT | Canada | Adults wtith T2DM | 18 months | |

| Prestwich, A, 2012 [56] | RCT | UK | Public Sector Employees 15 city councils | 6 months | |

| Seghers et al,2014 [62] | RCT | Belgium | Sedentary adult aged 18 to 65 Years | 12 weeks | |

| Shamizadeh T, 2019 [69] | Cluster RCT | Iran | Prediabetic rural people | 4 months | |

| Van Dyck D, 2016 [60] | RCT | Belgium | Recently retired adults | 1 month | |

| Van Hoye K,2018 [53] | RCT | UK | Adults with low physical activity | 4 weeks + follow up one year | |

| Van Nimwegen,2013 [64] | Multicentric RCT | Netherlands | Patients with Parkinson's disease | 2 years | |

| Vildeira Silva, 2021 [73] | QES | Portugal | Overweighted adolescents aged 12–17 | 12 months | |

| Yeom, HA, 2014 [76] | QES | US | community-dwelling older | 12 weeks | |

| Combined PA & SB | Balducci, 2017 [71] | RCT | Italy | Patient with diabetes type II | Once annually, 3 years |

| Lynch,2019 [59] | RCTb | Australia | Breast cancer survivors | 6 months | |

| O’Dwyer,2013 [54] | Cluster RCT | UK | Pre-schoolers under the age of 5 years old | 6 weeks | |

| Single SB interventions | Adams,2013 [48] | QES | US | Obese women | 6 weeks |

| Ashe, 2015 [66] | RCT | Canada | Retired women | 6 months | |

| Biddle,,2015 [18] | RCT | UK | Adult at risk of diabetes type II | 12 months | |

| Brakenridge, 2016 [58] | Cluster RCT | Australia | International Company Employees | 3 months | |

| Carr,,2013 [77] | RCT | US | University Employees Overweighted | 12-week | |

| Cocker, 2016 [78] | RCT | Belgium | University & Environmental agency Employees | 3 months | |

| Hadgraft, 2017 [57] | Cluster-RCT | Australia | Government department Employees | 12 Months | |

| Ismail,2022 [72] | QES | Qatar | Different sectors Employees | 66 days | |

| Mendoza2016 [51], | Cluster RCT | US | Pre-schoolers 3–5 years | 7–8 weeks | |

| VanDantzig2011 [63] | QES | Netherlands | Office workers at different companies | 6 weeks | |

| Yan 2009, [52] | QESa | US | Community-dwelling older adults > 50 years | 6 months |

a QES quasi-experimental study b RCT Randomized control trial c M-RCT Multicentric RCTs

Study design, context, and participants

All studies used experimental designs, including randomized controlled trials (n = 13), cluster randomized trials (n = 6), and multisite RCTs (n = 2) and quasi-experimental studies (n = 8). These studies took place in diverse settings and targeted various populations (see Table 5).

Nine studies were conducted in the workplace [50, 56–58, 61, 63, 70, 72, 75]. Seven studies reported interventions for people with chronic illnesses, diabetes (n = 3) [65, 69, 71], obesity (n = 1) [48], cardiovascular disease (n = 1) [68], and Parkinson’s disease (n = 1) [64] as well as for survivors of breast cancer (n = 1) [59]. Other studies included different groups such as older adults (n = 4) [52, 55, 66, 76], healthy adults (n = 2) (53. 62), university students (n = 2) [67, 74], and preschool children (n = 2) [51, 54] (see Table 5).

Description of theory based BCI

In our scoping review, we identified 29 articles describing interventions informed by behavioral theories targeting SB and PIA. Among these, fifteen articles aimed to address PIA to meet guideline recommendations, while eleven focused on reducing SB. Three articles combined interventions to reduce SB and increase PA (see Table 6).

Table 6.

Description of interventions according to the behavioral change intervention ontology

| Authors | BCI context | BCI mode of delivery (MoD) | BCI Level of delivery | BCI content | BCI Outcome on target behavior |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alsaleh E, 2016 [68] | Jordanian outpatients with CHD | Face to face individual based MoD,distance electronic MoD: messaging | Individual level |

C Gr: usual care from physicians: general advice about the benefits of PA and instructions to engage in moderate-intensity PA int Gr: Communication strategy: Face to face consultation 20–30 Mn for motivational interviewing Digital intervention: Text- message phone patient received six telephone call (15,20') One per month. and received prompts and reminders to be PA by mobile text message |

Increased PA |

| Alsaleh E, 2023 [67] | students at a Jordanian University | Face to face Group and Individual based MoD electronic MoD: web site, messaging, and mobile application | Individual level |

C Gr: Educational session (60 min lecture every month) about PA’s health advantage, risks from PIA, as well as methods for increasing PA int Gr: Communication strategy: consultations: individual face to face; Digital intervention: text message phone, reminder and motivational text messages and Facebook Using Devices: pedometer |

Increased PA |

| Corella et al, 2019 [74] | University students | Face to face group-based MoD Electronic computer and mobile digital device MoD | Individual level |

C Gr: PA habits int Gr: Educational: Cognitive phase: educational/ (7 weeks, with eight 60 min sessions) Behavioral phase: training exercise (13 weeks, with a total of thirty 60 min sessions). both group: Digital intervention: using device accelerometers (Actigraph GT3X y GT3X +) |

No change on PA |

| Krebs S, 2020 [75] | Employees of a German automotive and industrial supplier | Face to face group and individual based Mod Printed material (letter) MoD, at-a-distance MoD | Individual level |

All participants received PA promotion program: Control gr PA: Educational intervention: 4 courses modules (90 Mn each), followed by a 90-min practical PA unit (variety activities and intensity) Int Gr PA + C: Educational intervention: 4 course modules (90 Mn each) + coaching intervention (30-min psychological coaching unit including motivational and volitional strategies of behavior modification. followed by a 60-min practical PA unit, Participants of the PA C group additionally received two booster modules: a postal reminder (BM1) three weeks and a telephone contact (BM2) five weeks after the end of CM4 |

Increased PA |

| Liu JYW, 2023 [55] | Frail older adults | Face to face group and individual based MoD` | Individual level |

C Gr: Education received health talks (health issues, such as preventing falls and maintaining a healthy The experimental group (COMB) received a 16-week program with a combination of individualized exercise training (A weekly, 45–60 min,) the BCE program: Communication strategy (motivational interview) (six face-to-face one-hour sessions plus two booster sessions) based on HAPA Booster Sessions The active control group: received 16-week program with a combination of exercise (by physiotherapist) and health talks |

Increased PA |

| Mahmoudi et al., 2020 [70] | Airport Staff | Face to face group-based MoD and Printed (brochure)material, electronic messaging MoD | Individual level |

C Gr: Educational meeting and Distribution of educational brochure at the end of the research lnt Gr: Educational meeting for training sessions per week and educational brochure in the start of the intervention and Digital intervention: monitored weekly by short message services (SMS) for four times |

Increased PA |

| Plotnikoff, RC, 2013 [65] | Adults wtithT2DM |

Printed materials (brochures)Mod Face to face individual based Electronic MoD: mobile digital device and at-a-distance MoD |

Individual level |

ADAPT: Alberta Diabetes and Physical Activity Trial: 3 group C Gr: Educational intervention: standards print materials Intervention Gr1: face to face evaluation of stage of change for PA + Educational intervention: PA guidelines as well as stage-based, print materials developed to address issues specific to the PA; Digital intervention: devices Intervention G2: same materials intervention of intG1 and CG + communication strategy: telephone counselling (type 2 diabetes, PA, older adults, communication approaches including motivational interviewing) |

No change in PA |

| Prestwich, A, 2012 [56] | Employees from 15 councils (public sector organization) | Face to face group-based intervention And Printed material (Texte)MoD Pair-based MoD |

Individual level Interpersonal level |

C Gr: Educational session: guidelines explanation (PA goal, text about benefits of PA to prevent heart diseases Int Gr 1: Collaborative implementation intentions: this group with informed that taking a partner to attain their goal is more helpful, and they were asked to discuss with partner and make plans to increase their PA in the form: "IF- THEN" and to identify different scenarios Int Gr 2: Partner only: were asked to have a partner to help them to be more Physically active but not asked to form a collaborative implementation intention Int Gr3: Implementation intentions participant were asked to plane their the action according "IF–THEN" but without a partner |

Increased PA |

| Seghers et al, 2014 [62] | Sedentary adult aged 18 to 65 Years in the community | Face to face group and individual based MoD |

Individual level Interpersonal level |

Fit in 12 weeks” Standard-intervention Gr: Educational: progressive cycle ergometer test and measurement of height and weight, followed by a discussion in small groups of 4 to maximal 8 participants: information about PA et her benefit, instruction about performing PA, self-monitoring Extra-intervention Gr: intervention Gr + Brief coaching session, targeting self-efficacy by elaborating PA intentions, was added to the existing intervention |

Increased PA |

| Shamizadeh T, 2019 [69] | Prediabetic rural people | Face to face group-based MoD and Interactional MoD |

Individual level Interpersonal level |

C Gr: Routine care for diabetes with general information Int Gr: Educational: 1 session/week (90mn for encouraging on doing PA (plan to do encouraged to support each one + tips on Brochure on haw to do PA |

Increased PA & decreased SB |

| Van Dyck D, 2016 [60] | Recently retried Adult | Electronic computer, e mail and website MoD | Individual level |

‘MyPlan1.0.: 3 modules: Both group: questions on PA evaluation C Gr: Received no intervention Int Gr: evaluation questionnaires on PA and received the self-regulation eHealth intervention ‘ Digital intervention: Desktop intervention: module 1 (T0): Pre-intentional processes: PA were assessed by IPAQ and compared with the health guidelines + reading information about PA; Post-intentional processes: inviting participants to make an action plan ( how, when, where, with whom) to bridge the gap between intentions and behavior, and coping planning module 2 (1 WEEK): participants received feedback about their behavioral change process and their goal and participants had the possibility to adapt their action plan. Adaptations could consist of formulating new goals; Module 3: (1 months after module 2) and was identical to module 2 |

Increased PA |

| Van Hoye K,2018 [53] | Adult with Low Physical activity | Face to face group-based MoD electronic MOD: mobile digital device electronic MoD: wearable electronic device Face to face individual based MoD | Individual level |

all group received educational intervention: information on objectively measured daily PA and recommendation Four group were randomized and received different types of feed-back the Minimal Intervention Gr: who received no feedback during the intervention, Pedometer Gr: Digital intervention received continuous feedback on steps by a pedometer, Display Gr: who received continuous feedback on steps, moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA), and energy expenditure (EE) by the Digital intervention SWA (Sense Wear Armband), Coaching Gr (Coach): Coaching Strategy personal coach (face to face meeting 30 min /week) with personal feed-back in addition to digital intervention continuous feedback by a SWA |

Increased PA |

| Van Nimwegen et al., 2013 [64] | Patients with Parkinson's disease | Face to face individual based MoD and Printed materiel MoD | Individual level |

Park fit program: physical therapy & training/exercises sessions C Gr: Patients received a general physiotherapy and identical brochure to Park-Fit patients an active lifestyle was not explicitly stimulated Individual intervention: 1) training /exercises: who guided each patient towards a more active lifestyle during monthly coaching sessions; 2) Regular physiotherapy sessions, the therapist and patient jointly formulated individually tailored aims of treatment Educational brochure: the benefits of PA and suitable activities for patients with Parkinson’s disease; |

Increased PA |

| Videira-Silva et al, 2021 [73] | Overweighted adolescents aged 12–17 | Printed materiel (brochure) Face to face individual based intervention | Individual level |

C Gr: standard care: Educational: participants received a brochure with PA guidelines with examples of physical exercises at their first visit and Digital intervention: an accelerometer Experimental group I: standard care plus coaching strategy PA counselling based on the transtheoretical model and self-determination theory Experimental group II (EGII) standard care, coaching strategy PA Counselling and training intervention two weekly structured physical exercise sessions in phase one of intervention |

Increased PA |

| Yeom, HA, 2014 [76] | Community-dwelling older | Printed materiel (letters) Face to face group-based intervention and Interactional MoD |

Individual level Interpersonal level |

Motivational Physical Activity Intervention (MPAI) within a culturally context C Gr: Educational intervention: received biweekly newsletters focusing on older health issues( nutrition, stress management, oral health..)and they no received any information or support specifically to increase physical activity during the intervention period Int Gr MPAI: Physical activity training 1-h sessions held twice a week for 12 week, including 10-min warm up using flexibility exercises, 10-min balance training, and 20-min moderate intensity walking; coaching strategy including: social support operationalized through group process, goal setting, and interaction; empowering education and motivational support for enhancing motivational appraisal and skills to initiate and sustain regular physical activity |

Increased PA |

| Balducci et al., 2017 [71] | Patient with diabetes type II | Face to face group-based MoD Electronic intervention mobile digital device MoD` |

Individual level Organizasional level |

Multidisciplinary teams /patients Educational intervention: for physician: increase knowledge, prescribing and counselling on PA, f Exercise specialist: how to assess physical fitness and PA volume and supervising exercise session both of theme: how to retain participant in the trial C Gr: Standard care with PA advice Int Gr: Educational and coach strategy: theorical counselling session: face-to-face, seven-step counselling session, and training / exercise Theoretical and Practical Counselling Sessions Digital intervention: using device uniaxial piezoelectric accelerometer, |

Increased PA & decreased SB |

| Lynch et al., 2019 [59] | Breast cancer survivors | Face to face individual based MoD and Printed material (publication) Electronic wearable electronic and at a distance MoD | Individual level |

Composed of three components and is delivered across a 12-week period: (i): Educational session on Behavioural feedback and goal setting: a single face-to-face session with an ACTIVATE Trial staff member. In this session, participants receive a workbook that provides information on the field (ii) digital intervention: intervention using devices Wearable technology activity monitor: Participants are provided with a Garmin Vivofit2® activity monitor, (iii) individual intervention: Telephone-delivered behavioural counselling: to facilitate maintenance of behaviour change |

Increased PA & decreased SB |

| O’Dwyer et al, 2013 [54] | Pre-schoolers under the age of 5 years old | Face to face group-based MoD Gamification MoD |

Individual level Organizasional level |

C Gr: continue to deliver their usual PA provision int gr: Educational active play program and educational: for staff and children in preschool settings: instruction followed by construction of preschool staff in conjunction with active play. Independent instruction by preschool staff members was supported by the active play professionals |

No changes in SB and PA |

| Adams et al., 2013 | Obese women | Face to face group-based intervention & electronic MoD computer and mobile digital device ` | Individual level |

C Gr: waitlisted control: no intervention Int Gr: Educational intervention: face-to-face contact: information about SB risk, alternatives behavior, workbook for monitoring activities (using Actigraph); Digital Intervention: Online Interventions via a Computer: (e-mails messages): 3 to 6 weeks: Seven individualized emails (goal reminders, goal feedback, or examples of less SB) and Using Devices Actigraph and pedometer for self-evaluation and goal setting during the intervention |

Decreased SB |

| Ashe et al, 2015 [66] | Retired women |

Face to face individual and group-based MoD Electronic wearable electronic device |

Individual level Interpersonal level |

C Gr: Educational intervention: 3 sessions but no interactions with the exercise professionals nor did they receive Fitbit monitors Int Gr: Multicomponent Everyday Activity Supports You (EASY) model: Educational intervention: group-based education and social support 2) individualized PA prescription and Digital intervention: using devices FIT BIT |

Increased PA & decreased SB |

| Biddle et al., 2015 [16, 18] | Adult at risk of diabetes type II | Face to face group-based intervention and at distance Mod and mobile digital device MoD | Individual level |

Project STAND three distinctive phases Education: participant attend to a single 3-h group-based structured education workshop delivered by two trained educators (knowledge and perceptions of prevalent risk factors for type 2 diabetes and promoting SB change) A follow-up phone call six weeks after their attendance at the workshop (review their progress, and to discuss their goals and barriers and support their behavior change) Digital intervention: using devices: |

No changes in SB and PA |

| Brakenridge et al. 2016 [58] | International Company Employees |

Environmental change MoD: Printed materiel (publication): face to face individual and group based + At distance MoD |

Individual level Interpersonal level Organizational level |

Based on STAND UP Australia intervention: Organizational level intervention: recruitment of workplace champion,( for recruitment, delivery of the intervention, distribution and collection of equipment, and communications) Education: the booklet contained information on sitting and health implications, an introduction to the Stand Up Lendlease program, recommendations and tips Feed-back: five fortnightly tips emails developed by researcher and champion, individual interview feedback and focus group Executive Management Support:. Their participation in the study was communicated to participants by the champion Digital intervention: using devices Activity tracker |

Decreased SB |

| Carr et al, 2013 [50, 77] | University Employees Overweighted |

Environmental change MoD Electronic MoD: computer and mobile digital devices |

Individual level Organizational level |

“Pedal Work: The intervention comprised three primary components: [1] Environmental intervention: access to a portable pedal machine (MagneTrainer, 3D Innovations, Greeley, Colorado, USA) at their worksite; [2] Digital intervention: Desktop intervention access to a motivational website (Walker Tracker, Portland, Oregon, USA) to receive tips and reminders focused on reducing sedentary behaviours throughout the day and [3] Digital intervention: Intervention using devices pedometer |

Decreased SB |

| Cocker et al.,2016 [78] | University / Environmental agency Employees | Electronic computer and mobile digital devices MoD | Individual level |

C Gr: wait-list control received the generic intervention after completing all measurements Int Gr1: tailored group computer-tailored advice: personalized feedback and tips on reducing or interrupting workplace sitting Int Gr2: Generic advice received a Web-based intervention: containing generic information and tips on reducing or interrupting workplace sitting Digital intervention: online via computer: personalized computer-tailored advice on their sitting, including tips and suggestions on how to interrupt) and reduce sitting time + intervention using devices"activPAL" |

Decreased SB |

| Hadgraft et al., 2017 [57] | Government department Employees |

Face to face and at a distance MoD individual base Environmental change MoD Interactional MoD |

Individual level Interprsonal level Organizational level |

Individual level: participants receive face-to-face and telephone health coaching (self-monitoring of behavior, personalized feed -back,) organizational l level: A dual-screen sit–stand workstation with a work surface accessory was installed for the duration of the study social level: engagement of stakeholders throughout the entire intervention process, including the selection of strategies to implement and the designation of a 'champion' |

Decreased SB |

| Ismail et al., 2022 [72] | Different sectors Employees |

Environmental change Electronic and mobile application MoD Electronic computer and application mobile and digital device MoD |

Individual level Organizational level |

C Gr: received static reminders, the app provided location, weather and time information Intervention group: Digital intervention (M-health)First,: PA evaluation by online International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) the participants were given the mobile app that automatically logs their step count, received context-aware motivational messages, sending motivational messages every 40 min, and the duration of the breaks was estimated as 1–3 min |

Decreased SB No effect on PA |

| Mendoza et al, 2016 [51] | Pre-schoolers 3–5 years | Face to face group-based intervention and Printed MoD |

Individual level Organizational level |

Educational: seven themes for children: each composed of five to six lesson plans of 15–30 min organized around the theme and newsletter sent home weekly to inform parents of the lessons and to provide optional home activities to complete with their pre-schoolers | Decreased SB |

| Van Dantziget al,2011 | Office workers at different companies |

Electronic MOD comprising mobile application MoD Gamification: wearable electronic devices and computer MoD |

Individual level Organizational level |

Sit-Coach: Digital intervention: intervention using M-health: a smart phone application, prompting users to take regular active breaks and measures physical activity by means of the built-in accelerometer and reminds SitCoach reminds users to take a break after a configurable number of inactive minutes in the second experiment, participants received a commercial activity monitor and had a small piece of software installed on their computer to measure computer activity |

Increased PA & Decreased SB |

| Yan et al., 2021 | Community-dwelling older adults > 50 years | Face to face and group-based MoD |

Individual level Interprsonal level |

Active Start Program: C Gr: Int Gr: Active Living Every Day (ALED)(4weeks): group support Participants meet 1 h a week, in a group setting, to set goals, identify barriers, and establish social support systems ExerStart began (after 4 weeks of ALED) is a low-intensity program designed for sedentary older adults. It comprised 43 exercises focusing on aerobic strength, flexibility, and balance |

Decreased SB |

C Gr control Group, Int G Intervention Group

In the following, we will describe the content of BCIs, levels of interventions, mode of delivery and reported outcomes (see Table 6).

Content of BCIs

Most BCI interventions adopted educational methods (n = 20) aimed at raising awareness of the importance of meeting PA recommendations and breaking the vicious cycle of SB [18, 48, 51, 53–56, 59, 62, 64–67, 69–71, 73, 75, 76, 79]. These interventions also included communication strategies (n = 14): motivational interviews (n = 4) [68, 75, 76, 80], and coaching (n = 10) (face-to-face consultations or phone calls) [18, 53, 57, 59, 62, 64, 65, 67, 71, 73]. Social support to implement interventions was used nine times [51, 52, 56, 57, 62, 66, 69, 76, 79], and physical exercise training was used 8 times [52, 54, 64, 66, 70, 71, 73–76, 80]. Finally, digital interventions (devices, desktops, m-health) were used in most interventions (n = 16)0.2

Levels of interventions

The majority of interventions involved individual-level BCIs (n = 15). Few studies combined the individual level of the interpersonal level (e.g., peer support) (n = 6) [52, 56, 62, 66, 69, 76], and six studies combined the individual level with organizational-level interventions (n = 6) [50, 51, 54, 63, 71, 72]. Only two studies can be described as systemic BCIs addressing the individual, interpersonal, and organizational levels (n = 2) [57, 79] (see Table 6).

Heterogeneity of modes of delivery

The modes of delivery of BCIs were often mixed. BCIs included face-to-face delivery in most cases (n = 24) with single individuals (n = 6) [57, 59, 64, 65, 68, 73] or with groups of people (n = 10) [18, 48, 51, 54, 56, 69–71, 74, 76] or a combination of both modes of delivery (n = 8) [52, 53, 55, 58, 62, 66, 67, 75]. The electronic mode of delivery was often employed (n = 15), including messaging (n = 3) [67, 68, 70], computer-based delivery (n = 6) [48, 61, 63, 72, 74, 77], and digital devices (wearable or mobile devices) (n = 13) [18, 48, 50, 53, 58, 59, 61, 63, 65–67, 71, 74]. The printing mode of delivery was also utilized less frequently (n = 10).

Reported outcomes

Twenty-five of the 29 interventions mentioned a decrease in PIA and SB, while four studies [18, 54, 65, 74] found no changes in SB or PIA. These four interventions specifically targeted preschool children, school-age students, and adults at risk of diabetes. Four studies reported mixed results and inconclusive evidence. One study showed a significant decline in SB without any change in the level of PA [72] (see Table 6).

Behavioral theories

Our scoping review showed that the authors of the included studies referred to 15 behavioral theories (n = 15) (see Table 7 and Supplementary file 5). Most of the included studies used at least one of the four following theories: SCT (n = 14), SDT (n = 6), the TTM (n = 6), the TPB (n = 6), the SEM (n = 5), and the HBM (n = 5). Most interventions used either a single theory (n = 13) or a combination of two BCTs (n = 12). Only two interventions did not explicitly define the theoretical constructs guiding the development of the BCIs.

Table 7.

Behavioral change theories and key constructs used in the design of BC interventions

| Targeted Behavior | Physical activity [68]; [67, 74, 75, 55, 70, 65, 56, 62, 69, 60, 53, 64, 73, 76] | PA & SB [54, 59, 71] | SB [48, 66, 18, 58, 77, 78, 57, 72, 51, 63, 52] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Key theoretical constructs | ||||

| Social Cognitive Theory | Self-efficacy | [68, 67, 65, 62, 69] | [71] | [48, 66, 18, 58, 77, 57] |

| Expectations | [65, 69] | |||

| Expectancies | [69] | [58, 57] | ||

| Self-regulation | [67, 69] | [66, 18, 58, 57] | ||

| Observational learning/Modeling | [67] | [71] | [48, 66, 51] | |

| Reinforcement rewards/punishments | [68] | [71] | [66, 51] | |

| Behavioral capability | [67] | [18] | ||

| Social Ecological Model | Intrapersonal level factors | [66, 58, 57, 72] | ||

| Interpersonal level factors | [54] | [66] | ||

| Institutional level factors | [54] | [66, 58, 57, 72] | ||

| Community level factors | [66, 58, 7, 72] | |||

| Societal level factors | [66, 72] | |||

| Health belief model | Perceived susceptibility | [71] | ||

| Perceived benefits | [71] | |||

| Perceived barriers | [71] | |||

| Perceived seriousness | ||||

| Modifying variable | ||||

| Cues to action | [71] | |||

| Self-efficacy | ||||

| Theory of Planned Behavior | Attitude | [68, 67, 65] | [71] | [78] |

| Subjective norms | [68, 67, 65] | [78] | ||

| Volitional control | [68, 75] | [78] | ||

| Behavioral control | [68, 67, 65] | [78] | ||

| Self Determination Theory | Motivation | [74, 75, 73] | NA | [78] |

| Cognitive evaluation theory | ||||

| Organismic integration theory | ||||

| Causality Orientation Theory | [74] | [78] | ||

| Basic psychological needs theory | [74, 75, 53, 73] | [78] | ||

| Goal contents theory | [53] | |||

| Self-Regulation Theory | Sources of Control | |||

| Automatic processing | ||||

| Controlled processing | [60] | |||

| Self-Regulation/ self-regulatory | [60] | |||

| Stage of self-regulatory processes | [75] | |||

| Attributional process | ||||

| Transtheoretical Model Stages of Change | Stage of change | [74, 70, 65, 73] | [52] | |

| Decisional balance | [74] | |||

| Process of change | [65] | |||

| Self-efficacy | [74, 70, 65, 73] | |||

| Self-efficacy Theory | Mastery experience | |||

| Vicarious experience | ||||

| Verbal persuasion | [72] | |||

| Somatic and emotional States | ||||

| Social influence strategies | Authority | [63] | ||

| Commitment | [63] | |||

| Consensus | [63] | |||

| Liking | ||||

| Reciprocity | ||||

| Scarcity | [63] | |||

| Health Action Process Approach | Risk perception | [55] | ||

| Outcome expectancies | [55] | |||

| Perceived self-efficacy | [55] | |||

| Intention | [55, 60] | |||

| Action control | [55, 60] | |||

| Protection Motivation Theory | Response efficacy | [65, 56] | ||

| Self-efficacy | ||||

| Perceived Severity | [65, 56] | |||

| Vulnerability | [65] | |||

| Response costs | ||||

| Implementation Intention model(volitional), | Intention elaboration | [56] | ||

| Intention viability | ||||

| Intention activation | [56] | |||

| Contextual threats | ||||

| Wellness Motivation Theory | Empowering education | [76] | ||

| Motivational support | [76] | |||

| Social support | [76] | |||

| Mobility training | [76] | |||

| MoVo process model | Goal intention | [75] | ||

| Self-efficacy | [75] | |||

| Self-concordance | [75] | |||

| Outcomes expectation | [75] | |||

| Action planning | (75 |

The SCT was the most commonly used theory. Five interventions used SCT as a single theory (n = 5) [48, 50, 51, 62, 69], whereas eight employed a combination of other behavioral theories: SDT [65], TPB [6, 68, 65], TTM [64, 65], HBM, SEM [57, 64–66, 79], behavioral choice theory [18], and protection motivation theory (PMT) [65]. Interventions rooted in SCT addressed specific psychological and social constructs ranging from one to four constructs per intervention. The most frequently used constructs were self-efficacy, self-regulation, observational learning, and positive reinforcement (see Table 5). SCT was used almost equally to reduce SB and PIA.

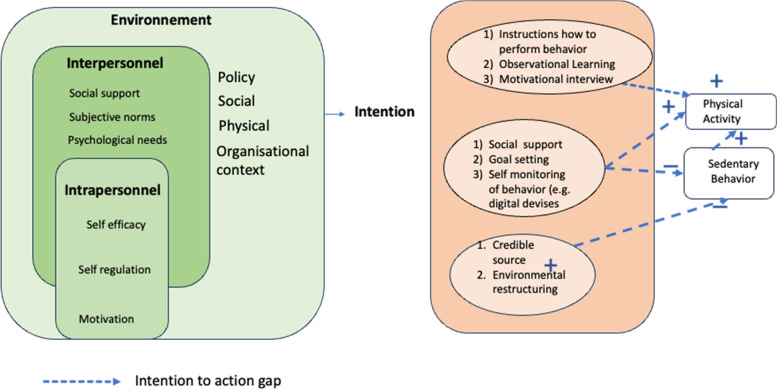

PA interventions mostly involved individual behavioral theories (SDT, SRT, TPB, TTM, HAPA), with a focus on reducing the intention-to-action gap. Conversely, the theories employed to reduce SB are primarily interpersonal (SCT, SET, SiS) and environmental (SEM). They seek to make behavior more socially acceptable, encouraging and influencing the behavior of others. Additionally, restructuring the environment is a central component of interventions aimed at reducing SB in the workplace.

Our scoping review showed that most interventions targetted the following individual-level constructs: self-efficacy (n = 16), motivation (n = 10), self-regulation [9], and the interpersonal level illustrated by using subjective norms (n = 5) and basic psychological needs (n = 4). Few studies have addressed environmental factors (e.g., institutional, community, society) (n = 7). The SB interventions used essentially socioecological constructs (n = 4) and enhanced self-efficacy (n = 6), self-regulation (n = 5), and modeling (n = 4). PIA BCI interventions were more centered on individual-level constructs such as motivation (n = 10), intention (n = 5), and controlled volition (n = 6) (see Table 8 and Supplementary file number 2).

Table 8.

Classification of included studies using the BCTs taxonomy

| Alsaleh 2016 [68] | Alsale 2023 [67] | Corella,2019 [74] | Krebs, 2020 [75] | Liu JYW, 2023 [55] | Mahmoudi,2020 [70] | Plotnikoff, RC,2013 [65] | Prestwich, A, 2012 [56] | Seghers et al,2014 [62] | Shamizadeh T, 2019 [69] | Van Dyck D, 2016 [60] | Van Hoye K,2018 [53] | Van Nimwegen, 2013 [64] | Vildeira Silva, 2021 [73] | Yeom, HA, 2014 76) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1 Goal setting | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 1.2 Problems solving and Barrier identification | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 1.4 Action planning and coping | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| 1.5 Review behavior goal | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| 1.8 behavioral contract | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| 2.2Feedback on behavior | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| 2.3 Self-monitoring of behavior | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| 2.4 Self-monitoring of outcome of behavior | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| 2.5 Monitoring behavior with other without feedback | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| 2.7 feedback on outcome of behavior | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| 3.1 Social support unspecified | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 4.1 instruction on how to perform the behavior | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| 5.1 Information about health consequences | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| 6.1 Demonstration of the behavior | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| 7.1 Prompt/cues | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| 7.2 Cue signalling rewards | |||||||||||||||

| 8.2 Behaviour substitution | |||||||||||||||

| 8.4 Habit reversal | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| 8.7 Graded task | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| 9.1 Credible source | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| 9.2 Pros and Cons | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| 10.2 Materiel reward | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| 10.4 Social reward | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| 12.1 restructuring the physical environment | ✓ |

| Balducci 2017 [71], | Lynch, 2019 59) | O’Dwyer,2013 54) | Adams, 2013 [48] | Ashe,2015 [66] | Biddle,2015 [18] | Brakenridge, 2016 [58] | Carr, 2013 [77] | Cocker, 2016 [78] | Hadgraft, 2017 [57] | Ismail, 2022 [72] | Mendoza 2016 [51] | Van Dantzig,2011 [63] | Yan, 2009 [52] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1 Goal setting | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| 1.2 Problems solving and Barrier identification | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| 1.4 Action planning and coping | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| 1.5 Review behavior goal | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| 1.8 behavioral contract | ||||||||||||||

| 2.2Feedback on behavior | ||||||||||||||

| 2.3 Self-monitoring of behavior | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| 2.4 Self-monitoring of outcome of behavior | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| 2.5 Monitoring behavior with other without feedback | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| 2.7 feedback on outcome of behavior | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| 3.1 Social support unspecified | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 4.1 instruction on how to perform the behavior | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| 5.1 Information about health consequences | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| 6.1 Demonstration of the behavior | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| 7.1 Prompt/cues | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| 7.2 Cue signalling rewards | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| 8.2 Behaviour substitution | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| 8.4 Habit reversal | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| 8.7 Graded task | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| 9.1 Credible source | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| 9.2 Pros and Cons | ||||||||||||||

| 10.2 Materiel reward | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| 10.4 Social reward | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| 12.1 restructuring the physical environment | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

Our scoping review revealed some discrepancies in the characteristics of PIA interventions compared with those of SB interventions. The latter were considered systemic interventions based on SCT and SEM. They combined multilayered actions at the macro-level (environmental restructuring), the meso-level (social and peer pressure) and the micro-level (by activating intrapersonal and interpersonal mechanisms of change). In contrast, BCI targeting PIA were mostly focused on the individual level of change by using individual intrapersonal theories (SDT, TTM, TPB, HAPA, and PMT).

Behavior change techniques

All interventions were designed as multicomponent interventions integrating various behavior change techniques (see Table 7).

Our scoping review revealed that the scholars of the included studies used a set of 25 BCTs. On average, six to nine BCTs were used in an intervention (a minimum of 5 and a maximum of 12).

Social support, which is unspecified, was the most commonly used type of BCTs and involved targeting the interpersonal level (social influence) (n = 28), followed by goal setting, targeting the individual level (goal and intention) (n = 24); solving problems and identifying barriers at the individual level (belief capability) (n = 18); instruction on how to perform behavior at the individual level; self-monitoring of behavior (n = 17); feedback on the outcome of behavior at the individual level (n = 14); information about health consequences at the individual level (n = 14); social rewards targeting the interpersonal level (reinforcement and social influence) (n = 9); restructuring the physical environment targeting the environmental level (n = 6); and materiel rewards, targeting the interpersonal level (reinforcement) (n = 4). In our scoping review, most BCTs targeted the interpersonal level and the individual level followed by the environmental level.

Common characteristics of BCI with no modifications to PIA or SB

These interventions were based on educational, self-monitoring and the use of a coaching strategy involving distinct connected devices that targeted adults at risk of metabolic diseases or diabetes type 2) [18, 65] or preschool children, students, and adults at risk of metabolic diseases [54, 74], or a single individual level of behavioral change. They used face-to-face training sessions. Key contextual conditions that prevent the effectiveness of theory-informed interventions include the absence of parental involvement in BCTs targeting children [54], a lack of peer support in interventions involving students [74], and the absence of illness in interventions targeting adults [18, 65].

Description of studies reporting positive changes in PIA and SB

The included studies, mostly carried out in the workplace (n = 9), used a combination of education, training, and communication strategies (motivational interviews or coaching), along with social support and environmental restructuring. The included studies emphasized the importance of systemic-level interventions combining actions at the individual (face-to-face and digital interventions using wearable devices, desktops, and apps) and interpersonal (social support and group interventions) levels with macro-level environmental restructuring. Environmental restructuring encompasses interventions such as installing pedals and workstations, sending email reminders, and even using digital health apps [50, 57, 58, 63, 72]; it also focuses on reinforcing the knowledge and skills of actors and providing social support through group interventions. In contrast, other studies reported that BCIs targeting individuals with chronic diseases (e.g., CVD [68], diabetes [65, 69, 71], Parkinson’s disease [64], obesity [48], and cancer survivors [59] are essentially individually focused and underwent substantive changes in PIA and SB. These studies suggest that patients with NCDs are more committed to education and that coaching interventions intrinsically motivate people to follow PA recommendations [59, 64, 68, 71].

Intensity of theory use

We found heterogeneous use of theory in the implemented interventions. Fifteen interventions involved an intensive degree of theory use (level 3). Eleven interventions entailed moderate levels of theory (Level 2), and three interventions utilized a low level of theory (Level 1) (see Table 9).

Table 9.

Intensity/degree of use theory in based theory-intervention

| Alsaleh 2016 [68] | Alsale 2023 [67] | Corella,2019 [74] | Krebs, 2020 [75] | Liu JYW, 2023 [55] | Mahmoudi,2020 [70] | Plotnikoff, RC,2013 [65] | Prestwich, A, 2012 [56] | Seghers et al,2014 [62] | Shamizadeh T, 2019 [69] | Van Dyck D, 2016 60) | Van Hoye K,2018 [53] | Van Nimwegen, 2013 [64] | Vildeira Silva, 2021 [73] | Yeom, HA, 2014 [76] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.theory mentioned | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 2. Relevant constructs targeted | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 3. change method lined to at least one construct | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 4. Participants selected based on a score of theory-related construct | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| 5. intervention tailored to different subgroup | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| 6. At least one construct or theory measured post-intervention | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 7. All theory measures presented some evidence of reliability | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 8. Results discussed in relation theory | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Score | 6/8 | 6/8 | 7/8 | 7/8 | 8/8 | 6/8 | 6/8 | 7/8 | 5/8 | 6/8 | 6/8 | 5/8 | 3/8 | 5/8 | 6/8 |

| Balducci 2017 71) | Lynch, 2019 [59] | O’Dwyer,2013 [54] | Adams, 2013 [48] | Ashe,2015 [66] | Biddle,2015 [18] | Brakenridge, 2016 [58] | Carr, 2013 [77] | Cocker, 2016 [78] | Hadgraft, 2017 [57] | Ismail, 2022 [72] | Mendoza 2016 [51] | Van Dantzig,2011 [63] | Yan, 2009 [52] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.theory mentioned | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 2. Relevant constructs targeted | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| 3. change method lined to at least one construct | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 4. Participants selected based on a score of theory-related construct | ||||||||||||||

| 5. intervention tailored to different subgroup | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| 6. At least one construct or theory measured post-intervention | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| 7. All theory measures presented some evidence of reliability | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| 8. Results discussed in relation theory | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Score | 5/8 | 2/8 | 3/8 | 4/8 | 6/8 | 6/8 | 5/8 | 5/8 | 6/8 | 6/8 | 4/8 | 4/8 | 4/8 | 5/8 |

Discussion

In sum, our scoping review showed that most interventions used a combination of similar modes of delivery, design, and components (education, training/coaching, regulation, and the use of connected devices), and BCIs were mostly individually focused and based, in most cases, on education and self-monitoring.

Most interventions were focused on individual levels of behavior changes and involved a multitude of intrapersonal behavioral theories and wearable devices for monitoring, using diverse BCTs with a focus on social support and goal setting. Only two studies can be considered systemic level theory informed BCIs addressing both individual intrapersonal drivers (e.g., motivation, attitude, perceived norms, self-efficacy, etc.) combined with interpersonal interventions (group and social support interventions) and macro-level interventions, such as environmental restructuring in the workplace.

Our scoping review indicated that single digital technology-based web apps informed by intrapersonal theories, such as the TPB, self-regulation, and SDT, had no significant effects. Hence, there is a need to combine intrapersonal theories with interpersonal and environmental interventions for better adherence to interventions and the adoption of a desired behavior [81, 82]. Indeed, interventions informed by the HBM, aimed at addressing an individual’s perceptions of PA and increasing one’s level of PA, have shown no significant effect [83].

The relevance of systemic theory informed BCIs stems from the complexity of causal processes underlying SB and PIA, which are considered a consequence of intricate interactions between intertwined levels of structure and agency [16, 18]. PIA and SB are influenced by individual, interpersonal, and organizational and broader contextual factors [84] (Heath et al., 2012). At the individual level, behavior is defined by people’s awareness, cognition, beliefs, and skills. At the interpersonal level, behavior is impacted by the extent to which social support is received from family and friends. At the organizational level, behaviors are constrained by cultural norms and practices in the workplace. At the broader level, behaviors are constrained by contextual factors at the national and global levels, such as legal frameworks, environmental restructuring, political and socioecological factors shaping individuals’ architecture of choice, and their day-to-day decision-making [16, 18].

This suggests the importance of considering the notion of “reciprocal determinism,” which refers to the dynamic interaction between personal social, and environment factors and behavior [24]. The environment plays a significant role in the acquisition of PA behaviors and, consequently, in behavioral change [85]; it can encompass the immediate environment around the individual (one’s parents, workplace, neighbors, and community) as well as the interpersonal environment of the community. As such, PA is conditioned by the individual’s motivation (which can be intrinsic or extrinsic) [86], physical ability, social support, the availability of wearable device pedometers or accelerometers [87] and the existence of an enabling living environment (sport fields, space, resources), and regulatory enabling policies (breaks/leave from work, health insurance) [16].

At the national and global levels, individual behaviors are often constrained or facilitated by national legal contexts and restructuring policies of the built environment, including public transit, green spaces, parks, and recreational facilities [88]. Thus, environmental restructuring can be a good example of the complementarity and synergies of interventions, as shown by Dugdill, who highlighted the relevance of macro-level interventions to alter the workplace, where people spend a great deal of time. Systemic interventions, in line with those used by [89, 90], that combine multiple levels of interventions (individual, interpersonal, and environmental) may have synergistic effects on behavioral changes compared with individually focused interventions (face-to-face and digital interventions).

Our review underscores the importance of environmental restructuring as a complementary intervention to individually focused BCIs. In the workplace, this can include promotion of managers’ leadership such that they serve as role models for employees, as suggested by [91–93]. As a consequence, employees may perceive strong social influence and peer pressure, which may increase their self-efficacy and self-regulated behaviors [94]. These interventions seem to foster social identification, social comparison, and socialization mechanisms by increasing individuals’ adherence to BCIs in the workplace [91–93].

In addition, at the organizational level, employees’ behaviors are often influenced by organizational policies promoting PA in the workplace [87]. Moreover, the broader context plays a role in shaping the individuals’ behaviors. For instance, Davis [21] reported that behavioral modeling is only effective if individuals see other active people in their social context. Other scholars have shown that a lack of perceived security (crimes, sexual harassment, incivility) may reduce people’s willingness to carry out outdoor PA [95].

Our scoping review indicates that in the context of school BCIs, in line with other findings [96, 97], children may also benefit from systemic interventions by reducing their screen time usage through school policies and receiving individual training sessions to enable them to reduce their SB while also engaging with their parents (interpersonal and social influence) through role modeling. However, more attention is needed to develop systemic BCIs based on multiple-level interventions, such as individual coaching, mentoring, interpersonal social support, and altering the physical and cultural environment [98].

Our scoping review, in line with [82, 94, 99] and [100], has shown the usefulness of SCT in explaining how the training and empowerment of individuals enhance their self-efficacy, self-regulation, their perceived benefits, and risk and control volition, which may prove appropriate in the context of PA and SB interventions.

Our scoping review demonstrated, in line with previous systematic reviews [101], that using a combination of multiple behavioral change techniques is associated with an increased overall effect of the intervention and the adoption of desired behavioral outcomes. Techniques include, for instance, social support, goal setting, and self-monitoring, in line with other studies [102, 103].

Figure 2 shows a tentative integrative framework that incorporates three levels of interventions (environmental, interpersonal, and intrapersonal) and may be useful for helping program designers to build theory informed BCIs on the basis of a multilayered theoretical model. For instance, at the intrapersonal level, one might use the HBM combined with the TTM and SDT. However, at the interpersonal level, program designers might use SCT and behavioral choice theory. At the environmental level, one can use environmental theories such as social influence strategies ( see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Integrative framework of theories and constructs for effective BCT interventions

These constructs serve as mechanisms of action at the individual and interpersonal levels. This finding aligns with the results regarding the contribution of SCT and its constructs in predicting and adopting active behavior.

Study limitations and research gaps

In our review, we identified a lack of comprehensive reporting by scholars of key theoretical constructs underlying the design of BCI. We may have missed other relevant literature, as we had to make some trade-offs between comprehensiveness, depth of analysis and feasibility (Arksey, 2005). However, we performed a systematic, comprehensive search of four databases, including Google Scholar, to identify contextually rich gray literature. In addition, two reviewers screened the titles and abstracts, and extracted the data. Our findings also suggest that many theory-informed interventions do not use theoretical constructs appropriately; however, a call for improving the reporting and quality of intervention fidelity is needed while promoting the use of standardized tools such as Michie’s taxonomy of BCIs [40] and BCTs [104].

Our scoping review included only experimental studies that lacked sufficient descriptions of the role of context in shaping the characteristics of interventions and their mechanisms of action. Thus, more attention should be paid to promoting evaluation using context-sensitive methods and approaching theory-based evaluation, realistic evaluation [105], qualitative comparative analysis [106], and contribution analysis [107]. Further research is needed to unpack the black box of behavioral theories -informed interventions by unraveling what works for whom and in what context.

Further studies are also needed to examine the role of individual and digital interventions, which we insufficiently explored in our review. More rigorous systematic and meta-analyses are needed to complement the results of this descriptive, explorative scoping review and to provide evidence of the effectiveness of Theory -informed BCI [85].

Conclusion

Our review offers an innovative approach to systematically categorize behavioral theories interventions using a set of appropriate behavioral theories taxonomies, tools, and techniques, and provides working examples of how these taxonomies can be applied to assess the theory use and the described characteristics of BCT theory-informed interventions. Our study suggests an integrative framework to help program designers develop interventions while implying that specific behavioral theories and BCTs can be used at every level of intervention (the individual, interpersonal and environmental, policy and global levels). In sum, the congruence between behavioral theories, the implementation settings, and the characteristics of the targeted subpopulations needs to be considered when designing behavioral theories interventions to reduce PIA and SB. One size does not fit all. We also recommend, in line with (Noar et al., 2008), that behavioral change practitioners select theories and techniques based on their congruence with participants’characteristics and the nature of the context.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Abbreviations

- BCI

Behavior Change theory based Intervention

- BCIO

Behavior Change Intervention Ontology

- BCTs

Behavior Change Techniques

- BeHEMoth

Health behavior, health context, exclusion, models and theories

- C Gr

Control group

- HAPA

Health Action Process Approach

- HBM

Health Belief Model

- IMB

Information Motivation Behavior

- Int Gr

Intervention Group

- JBI

Joanna Briggs Institute

- M-RCT

Multi-site Randomized Control Trial

- MoD

Mode of delivery

- NCDs

Non-Communicable Diseases

- PA

Physical Activity

- PIA

Physical Inactivity

- PMT

Protection Motivation Theory

- QES

Quasi-Experimental Study

- RCT

Randomized Control Trial

- SB

Sedentary behavior

- SCT

Social Cognitive Theory

- SDT

Self Determination Theory

- SEM

Social Ecological Model

- SET

Self-Efficacy Theory

- SiSt

Social influence Strategy

- TPB

Theory of Planned Behavior

- TTM

Transtheoretical Model of Change

- V1

First version

- WHO

World Health Organisation

- WoS

Web of Sciences

Authors’ contributions

H. E. K: PhD candidate, conceptualization, screening, data extraction, formal analysis, writing–original draft preparation, visualization. Z.B, ORCID: 0000–0002-0115-682X; PhD supervisor, contributed to the conceptualization, building of the search strategy, title and abstract screening, methodological support, revisions of different drafts and supervision. SV B, ORCID: 0000–0003-2074–0359 critically revised the final version of the manuscript. A K, PhD supervisor, critically revised the latest version of the manuscript.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.WHO. Global action plan on physical activity 2018–2030: more active people for a healthier world. 2019. Disponible sur: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789241514187. Cité 28 sept 2023

- 2.WHO guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour [Internet]. [cité 26 févr 2024]. Disponible sur: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789240015128

- 3.Wu J, Fu Y, Chen D, Zhang H, Xue E, Shao J, et al. Sedentary behavior patterns and the risk of non-communicable diseases and all-cause mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. Oct2023;146: 104563. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2023.104563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ricci NA, Cunha AIL. Physical Exercise for Frailty and Cardiovascular Diseases. In: Veronese N, éditeur. Frailty and Cardiovascular Diseases : Research into an Elderly Population [Internet]. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2020 [cité 29 sept 2023]. p. 115‑29. (Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology). Disponible sur: 10.1007/978-3-030-33330-0_12 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Danaei G, Ding EL, Mozaffarian D, Taylor B, Rehm J, Murray CJL, et al. The preventable causes of death in the United States: comparative risk assessment of dietary, lifestyle, and metabolic risk factors. PLoS Med. 2009;6(4):e1000058. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diaz KM, Shimbo D. Physical Activity and the Prevention of Hypertension. Curr Hypertens Rep déc. 2013;15(6):659–68. 10.1007/s11906-013-0386-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McTiernan A, Friedenreich CM, Katzmarzyk PT, Powell KE, Macko R, Buchner D, et al. Physical Activity in Cancer Prevention and Survival: A Systematic Review. Med Sci Sports Exerc juin. 2019;51(6):1252–61. 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.MichaelT Bardo, WilsonM Compton. Does physical activity protect against drug abuse vulnerability? Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2015;153:3–13. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.05.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]