Abstract

Objectives:

To descriptively assess cannabis perceptions and patterns of use among older adult cancer survivors in a state without a legal cannabis marketplace.

Methods:

This study used weighted prevalence estimates to cross-sectionally describe cannabis perceptions and patterns of use among older (65+) adults (N = 524) in a National Cancer Institute-designated center in a state without legal cannabis access.

Results:

Half (46%) had ever used cannabis (18% following diagnosis and 10% currently). Only 8% had discussed cannabis with their provider. For those using post-diagnosis, the most common reason was for pain (44%), followed by insomnia (43%), with smoking being the most common (40%) mode of use. Few (<3%) reported that cannabis had worsened any of their symptoms.

Discussion:

Even within a state without a legal cannabis marketplace, older cancer survivors might commonly use cannabis to alleviate health concerns but unlikely to discuss this with their providers.

Keywords: cannabis, oncology, older cancer survivors

Introduction

The prevalence of cannabis use in older age (65+ years) has increased dramatically (75% between 2015 and 2018), with 4.2% of U.S. older adults reporting past year use in 2018 (Han & Palamar, 2020). Older adults in the general population most frequently report health concerns (e.g., pain, insomnia), followed by anxiety and depression, as reasons for using cannabis (Kaufmann et al., 2022; Reynolds et al., 2018; Tumati et al., 2022; Yang et al., 2021). Rates and patterns of cannabis use can vary depending on numerous factors, including co-occurring medical diagnoses such as cancer (Arora et al., 2021; Choi et al., 2016; Han et al., 2017; Javanbakht et al., 2022; Kaskie et al., 2021; Maxwell et al., 2021; Subbaraman & Kerr, 2021).

The likelihood of a cancer diagnosis increases with advancing age (National Cancer Institute, 2021) and recent evidence suggests that older adult cancer survivors use cannabis at higher rates than older adults in the general population (Han & Palamar, 2020; Rajasekhara et al., 2022). In a study conducted within a state with a medical cannabis program (Rajasekhara et al., 2022), 8% of older cancer survivors completing routine urine drug testing tested positive for tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). This rate is twice as high as the 4.2% reported in the general population (Han & Palamar, 2020). Emerging research does indicate that medical cannabis use for adult oncology patients is safe (Aviram et al., 2020, 2022) and that patients perceive cannabis as beneficial for their symptom management (Pergam et al., 2017; Rosa et al., 2020; Vinette et al., 2022; Wegier et al., 2020). However, efficacy data on the medicinal use of cannabis is minimal, particularly among older adults (Minerbi, 2019). Older adulthood is a distinct developmental period, with increased risk of potential negative side effects from cannabis use (Choi et al., 2018; Cigolle et al., 2007; Han et al., 2023; Han et al., 2021; Hedrickson et al., 2020 Minerbi et al., 2019). For example, sedation and dizziness from cannabis can increase fall risk (Minerbi et al., 2019). In fact, there are increasing rates of cannabis-related emergency room visits among older adults (Han et al., 2023). Further, cardiac infarctions can be a side effect of cannabis use among those with unstable cardiac disease, a condition that is more prevalent in older adulthood (Minerbi et al., 2019). Therefore, a patient’s age is an important factor in evaluating the risks and benefits of cannabis use within the context of oncology care.

Despite unique aging-related considerations, there is limited research evaluating patterns of cannabis use among older adult cancer survivors. To our knowledge, no study has evaluated cannabis use patterns among older adult cancer survivors in a state without a legal cannabis marketplace. This information is relevant for oncology care, given that there remain 12 U.S. states with no medical or recreational cannabis programs (State Medical Cannabis Laws, 2022). Thus, this cross-sectional study used weighted prevalence estimates to describe cannabis perceptions and patterns of use, as well as rate of discussing cannabis with their provider, among older (65+) adults receiving care in a National Cancer Institute (NCI)-designated center in South Carolina. Cannabis is unregulated in South Carolina; however, low THC [the psychoactive cannabinoid in cannabis] and high CBD [cannabidiol, non-psychoactive cannabinoid], and CBD-only products are widely available. In addition, delta-8 THC (which functions similarly to delta-9 THC, the primary psychoactive cannabinoid in cannabis) is available over the counter in various forms (e.g., vapes, edibles) (Babalonis et al., 2021). As a secondary aim, we explored age-group differences within older age (65–74 vs. 75+ years) in relation to cannabis outcomes given a potential cohort effect and developmental distinction between these age groups (Lachman, 2001; Orimo et al., 2006). We hypothesized that prevalence among this sample would be lower than in oncology settings with medical cannabis programs (Rajasekhara et al., 2022) and discussions with providers would be uncommon (given no legal access to cannabis). We expected the most common reasons for using cannabis would be for pain and insomnia, patterns of use would be varied (e.g., modes of ingestion), and that this population would commonly perceive cannabis as beneficial for their symptoms.

Methods

Parent Study Setting and Sampling Methods

The NCI Cannabis Supplement was awarded to 12 NCI cancer centers across the US, including the Hollings Cancer Center (HCC) at the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) (National Cancer Institute, 2021) in South Carolina. Inclusion criteria to the parent study included being 18+ years of age, able to speak English, and having received a cancer diagnosis or treatment from January 2018 to December 2020 at HCC. Using probability sampling methods, the MUSC Biomedical Informatics Center randomly selected a total of 8000 patients from the HCC cancer registry diagnosed between January 2018 and December 2020. Of those eligible, there was a 13.4% survey response rate. Non-response analysis found differences by age category, sex, and race, based on electronic medical record (EMR) information. The parent study sample was weighted to HCC population totals by these demographic categories to account for potential non-response bias. Final HCC sample included 1036 survey completers. More detailed information about parent study procedures, weighing and primary outcomes from the entire sample can be found elsewhere (McClure et al., 2023).

Current Study Sample

This study is a subgroup analysis of older adults (65+ years) (N = 524; 51%) from the parent study (N = 1036) (McClure et al., 2023).

Procedures

After agreeing to participate in the survey (waiver of signed informed consent was approved for procedures) online or via phone, participants were directed to a one-time survey (10–30 minutes) and received a $20 Amazon gift code for completion. Cannabis was defined as: marijuana, cannabis concentrates, edibles, lotions, ointments, tinctures containing cannabis, CBD-only products, pharmaceutical or prescription cannabinoids (e.g., Dronabinol, Nabilone, Marion, Syndros, Cessamet), and other products made with cannabis. Given this inclusive definition of cannabis, this study was not able to differentiate outcomes among THC-dominant products compared to others (e.g., CBD-dominant, delta-8). All procedures were approved by MUSC Institutional Review Board.

Measures

The survey instrument was developed collaboratively between 12 NCI centers for potential harmonization of data across settings (National Cancer Institute, 2021).

Demographics and Cancer Type/Treatment.

Demographics (i.e., age, sex at birth, race, and ethnicity) were extracted from the MUSC EMR to inform non-responder analysis and to weight the sample. At baseline, participants also reported education, healthcare coverage, employment, marital status, primary cancer site, and cancer treatment status.

Cannabis Risks and Benefits.

All participants (regardless of cannabis use) selected (check all that apply) from a list of potential risks and benefits of cannabis use. The list included 15 benefits and 20 risks, with other as an option for both (see Tables and Figures for the full list of items for all measures).

Cannabis Education and Instructions.

All participants were asked if they had discussed using cannabis for their cancer symptoms with a healthcare provider (yes vs. no) and how comfortable they would feel talking with their provider about cannabis on a 4-point Likert scale (extremely comfortable to extremely uncomfortable). Those who endorsed cannabis use following diagnosis were asked, “Who is the main person that gives you instructions on how to use cannabis and how much to take?” (8 options including other and no one).

Patterns of Cannabis Use.

All were asked if they had ever used cannabis any time before their diagnosis (yes vs. no) and since diagnosis (yes vs. no). Those endorsing use since diagnosis reported if they had used during their cancer treatment (yes vs. no), and if they were currently using cannabis (yes vs. no). Those endorsing post-diagnosis use were asked their primary mode of using cannabis (8 options including other).

Reasons for Use.

Participants who used cannabis since diagnosis were asked to identify (check all that apply) 13 different reasons for their cannabis use.

Symptom Management.

Those endorsing cannabis use since diagnosis reported how cannabis improved or worsened 9 different symptoms using a 5-point Likert scale. Participants could also respond, “I do not have this symptom.”

Data Analysis

Weighting Procedures

Sample weights were based on selection probabilities, non-response adjustment (age, sex, and race), and post-stratification via raking to match the sample to known subgroup populations in the target population. Sample proportions are similar to population proportions, with the exception of the 75+ years age group, who were under sampled in comparison to the population. Weighted prevalence estimates in this study are therefore more representative of the older adult population (65+ years) receiving a diagnosis or cancer care at MUSC (2018–2020).

Descriptive Estimates

Unweighted (N’s) and weighted descriptive statistics were estimated for demographic characteristics, cancer type, and treatment status among the older adult (65+ years) sample, and specific to age groups (65–74 years, 75+ years). Weighted descriptive analyses were conducted using the svyset function in Stata 15.1 (StataCorp, 2017). This function specifies design characteristics using sampling units and weights. Because the sample was large relative to the population (i.e., >5%), the finite population correction was used to estimate standard errors. Weighted descriptives assessed perceptions of cannabis (risks and benefits), cannabis education/instruction (i.e., discussion with provider, comfort talking to provider, source of instructions), and rates of use (ever use, post-diagnosis use, current use) among the entire older adult sample. For those who reported cannabis use since diagnosis, weighted prevalence estimates were provided for primary mode of use, reasons for use, and self-reported impact of cannabis on symptoms.

Age-Group Comparisons

Weighted chi-square analyses examined age-group differences (65–74 years vs. 75+) in relation to belief in any cannabis benefits, any cannabis risks, cannabis education/instruction variables (discussion with a provider, comfort talking to provider, source of instructions) and patterns of use (ever use, post-diagnosis use, current use, primary mode of use). Significance was defined as p < .05.

Results

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

In this older adult population (N = 524), age ranged from 65 to 92 years (M = 72.3, SD = 5.3). Weighted estimate indicated 59.5% (95% CI: 58.4, 60.6) were between 65 and 74 years (N = 374) and 40.5% (95% CI: 39.4, 41.6) (N = 150) were 75+ years. The most common primary site for cancer was breast (20.0%; 95% CI: 19.2, 20.9), followed by melanoma and skin (10.8%; 95% CI: 10.2–11.5), head/neck (10.6%; 95% CI: 9.9 – 11.2), and prostate (10.6%; 95% CI: 9.9 – 11.4). The majority (73.4%; 95% CI: 72.4, 74.4) had completed cancer treatment at the time of this survey, 23.0% (95% CI: 22.1, 24.0) were in active treatment, and 3.6% (95% CI: 3.2, 4.0) had not yet begun treatment. Additional unweighted and weighted demographics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Unweighted and Weighted Demographic Characteristics of Older Adults.

| Older Adult Sample (N = 524) | 65–74 Years (N = 374) | 75+ Years (N = 150) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | N | Weighted % (95% CI) | Weighted % (95% CI) | Weighted % (95% CI) | |

| Sex at birthb | Female | 250 | 43.3 (42.3, 44.4) | 47.1 (45.9, 48.4) | 37.8 (35.9, 39.6) |

| Male | 266 | 55.5 (54.5, 56.6) | 51.0 (49.7, 52.2) | 62.3 (60.4, 64.1) | |

| Missing/unknown | 8 | 1.1 (1.0, 1.4) | 1.9 (1.6, 2.3) | - | |

| Raceb | White | 454 | 80.1 (79.0–81.0) | 74.1 (72.8, 75.3) | 88.9 (87.3, 90.3) |

| Black | 44 | 14.3 (13.4–15.2) | 19.0 (17.8, 20.2) | 7.3 (6.1, 8.8) | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 2 | .52 (.38–.72) | 0.9 (0.6, 1.2) | - | |

| American Indian | 1 | .22 (.14–.35) | 0.4 (0.2, 0.6) | - | |

| More than one race | 7 | 1.6 (1.37–1.95) | 1.4 (1.1, 1.8) | 1.9 (1.5, 2.5) | |

| Missing/unknown | 16 | 3.3 (2.9–3.8) | 4.3 (3.7, 4.9) | 1.9 (1.4, 2.7) | |

| Ethnicity | Hispanic | 6 | 1.4 (1.13–1.67) | 2.3 (1.9, 2.8) | 10.7 (9.5, 11.9) |

| Non-Hispanic/Unknown | 466 | 88.6 (87.9–89.3) | 88.1 (87.2, 88.9) | 89.3 (88.1, 90.5) | |

| Missing/unknown | 52 | 10.0 (9.4–10.7) | 9.6 (8.9, 10.4) | - | |

| Educationa | Less than 8 years | 1 | 0.2 (0.0–0.2) | 0.3 (0.2, 0.4) | - |

| Some high school | 10 | 3.6 (3.1–4.2) | 3.0 (2.5, 3.6) | 4.6 (3.7, 5.8) | |

| High school diploma | 52 | 10.9 (10.2–11.6) | 12.9 (12.0, 13.8) | 8.1 (7.0, 9.2) | |

| Vocational/technical | 27 | 5.3 (4.78–5.8) | 5.0 (4.5, 5.5) | 5.7 (4.8, 6.9) | |

| Some college | 116 | 21.3 (20.5–22.2) | 23.2 (22.1, 24.2) | 18.7 (17.2, 20.3) | |

| College degree | 149 | 27.8 (26.8–28.7) | 28.3 (27.2, 29.5) | 26.9 (25.2, 28.6) | |

| Postgraduate training | 158 | 29.2 (28.3–30.2) | 24.9 (23.9, 26.0) | 35.5 (33.7, 37.4) | |

| Missing/refused | 11 | 1.7 (1.5–2.0) | 2.5 (2.1, 2.9) | 0.6 (0.4, 0.9) | |

| Employmenta,b | Employed | 56 | 10.8 (10.2–11.5) | 13.8 (12.9, 14.7) | 6.4 (5.4, 7.6) |

| Retired | 426 | 80.8 (79.9–81.7) | 75.5 (74.4, 76.7) | 88.5 (87.0, 89.9) | |

| Unemployed | 10 | 2.58 (2.2–3.1) | 2.1 (1.8, 2.5) | 3.3 (2.5, 4.3) | |

| Disabled | 14 | 3.19 (2.8–3.6) | 5.0 (4.4, 5.7) | 0.6 (0.4, 0.9) | |

| Other | 4 | .68 (.53–.87) | 0.7 (0.5, 0.9) | 0.7 (0.4, 1.1) | |

| Homemaker | 2 | .25 (.18–.34) | 0.4 (0.3, 0.6) | - | |

| Marital statusa,b | Divorced | 60 | 11.1 (10.45–11.79) | 12.9 (12.1, 13.8) | 8.5 (7.4, 9.6) |

| Living as married | 6 | 1.0 (0.8–1.12) | 1.2 (1.0, 1.5) | 0.6 (0.4, 0.9) | |

| Married | 348 | 65.9 (64.9–66.9) | 63.0 (61.7, 64.2) | 70.2 (68.4, 72.0) | |

| Separated | 7 | 1.5 (1.3–1.8) | 1.1 (0.9, 1.5) | 2.1 (1.6, 2.7) | |

| Single, never married | 26 | 5.2 (4.8–5.8) | 8.8 (8.0, 9.6) | - | |

| Widowed | 68 | 14.1 (13.3–14.9) | 11.3 (10.5, 12.1) | 18.2 (16.7, 19.8) | |

| Missing/refused | 9 | 1.2 (1.0–1.4) | 1.7 (1.4, 2.0) | 0.6 (0.4, 0.9) | |

| Health insurancea | Covered | 511 | 97.5 (97.1, 97.9) | 97.0 (96.6, 97.5) | 98.2 (97.5, 98.8) |

| Not covered | 3 | 1.0 (0.7, 1.3) | 0.8 (0.6, 1.2) | 1.2 (0.8, 1.9) | |

| Missing/refused | 10 | 1.5 (1.3, 1.7) | 2.1 (1.8, 2.5) | 0.6 (0.4, 0.9) | |

Note. Demographics were patient-reported (optional) and obtained from electronic medical record (EMR). Sample weights were based on selection probabilities, non-response adjustment (age, sex, and race), and post-stratification via raking to match the sample to known subgroup populations in the target population.

Patient-reported demographics.

Significant age-group differences found by weighted chi-square analyses.

Age-Group Comparisons.

Age-group differences were found by sex at birth [χ2(2) = 9.5, p = .01], race [χ2(5) = 20.4, p < .001], employment status [χ2(6) = 21.0, p < .001], and marital status [χ2(6) = 28.8, p < .001] (Table 1). Compared to younger patients (65–74 years), the population of patients 75+ years were more likely to be male (62.3% vs. 51.0%), White (88.9% vs. 74.1%), retired (88.5% vs. 75.5%), and married (70.2% vs. 63.0%). Ethnicity, education, and health insurance status did not differ by age group (p’s > .05).

Cannabis Perceptions

Benefits.

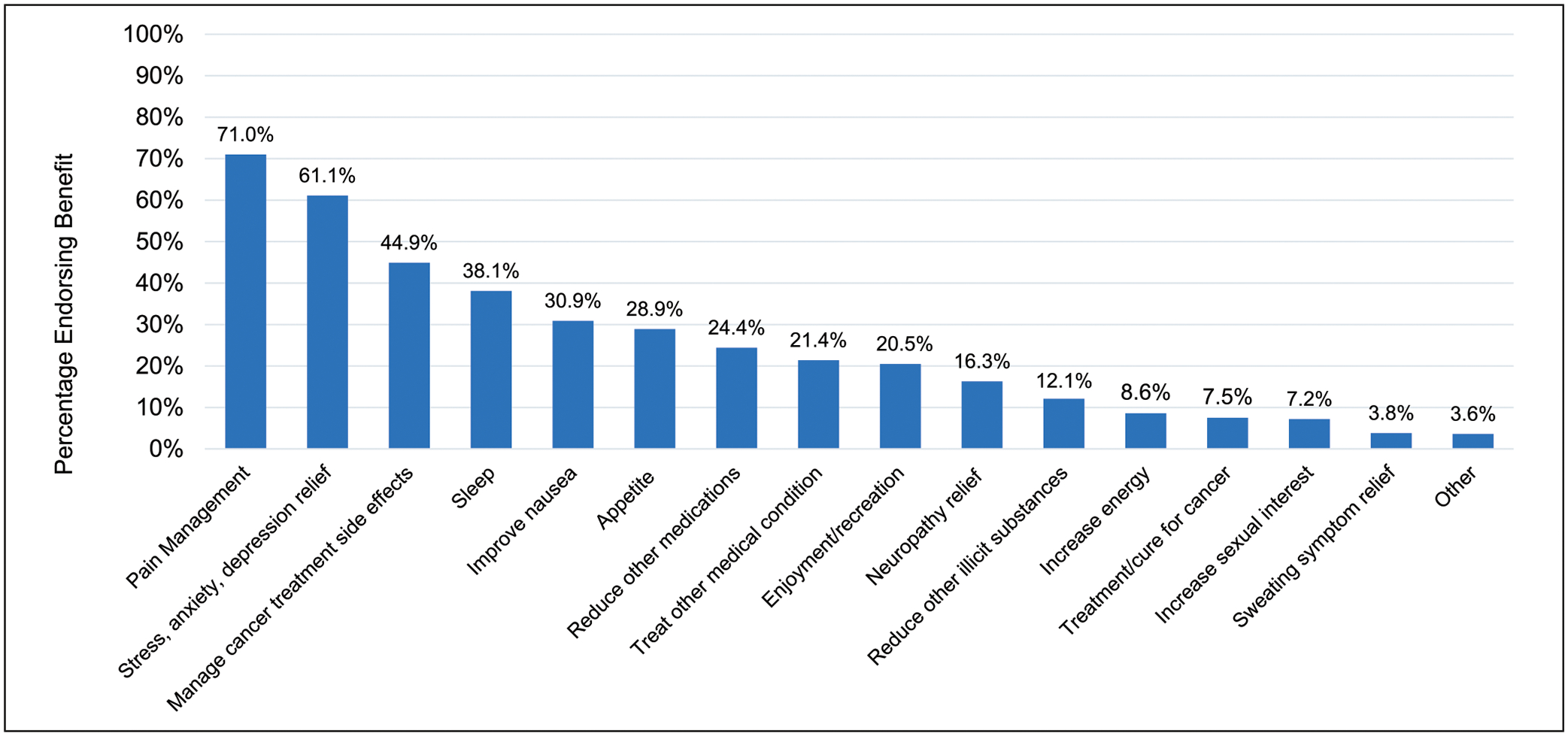

Among older adult cancer patients, 79.8% believed there were benefits to cannabis use (Table 2; Figure 1 for weighted estimates of all benefits). The most endorsed benefit was pain management (71.0%), followed by relief of stress, anxiety, or depression (61.1%), managing cancer treatment side effects (44.9%), and improving sleep (38.1%).

Table 2.

Cannabis Perceptions and Patterns of Use Overall and by Age Group.

| Full sample of older adults (N = 524) | 65–74 Years (N = 374) | 75+ years (N = 150) | p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Weighted % (95% CI) | N | Weighted % (95% CI) | N | Weighted % (95% CI) | P | |

| Belief in any benefit of cannabis (Yes) | 428 | 79.8 (78.8, 80.7) | 313 | 82.5 (81.4, 83.4) | 115 | 75.8 (74.0, 77.4) | .06 |

| Belief in any risk of cannabis (Yes) | 358 | 68.7 (67.7, 69.7) | 242 | 62.8 (61.5, 64.0) | 116 | 77.4 (75.7, 79.0) | <.001 |

| Discussed with healthcare provider (Yes) | 48 | 7.9 (7.4, 8.4) | 45 | 12.2 (11.4, 13.1) | 3 | 1.5 (1.1, 1.9) | <.001 |

| Comfort discussing use with provider | .46 | ||||||

| Extremely comfortable | 265 | 49.7 (48.6, 50.8) | 192 | 51.4 (50.2, 52.7) | 73 | 47.2 (45.2, 49.1) | |

| Somewhat comfortable | 141 | 26.7 (25.6, 27.7) | 104 | 27.0 (25.9, 28.1) | 37 | 26.3 (24.6, 28.1) | |

| Somewhat uncomfortable | 69 | 13.3 (12.6, 4.1) | 45 | 11.4 (10.7, 12.2) | 24 | 16.1 (14.7, 17.7) | |

| Extremely uncomfortable | 49 | 10.3 (9.6, 11.0) | 33 | 10.2 (9.4, 11.1) | 6 | 10.4 (9.3, 11.6) | |

| Cannabis ever use | 260 | 46.0 (45.0, 47.1) | 214 | 56.4 (55.1, 57.6) | 46 | 30.8 (29.1, 32.7) | <.001 |

| Cannabis current use | 60 | 9.8 (9.2, 10.4) | 57 | 15.3 (14.5, 16.3) | 3 | 1.6 (1.2, 2.1) | <.001 |

| Cannabis use following diagnosis | 107 | 18.2 (17.5, 19.1) | 94 | 25.3 (24.2, 26.4) | 13 | 7.9 (7.0, 8.9) | <.001 |

| Cannabis use during treatmenta | 50 | 50.1 (47.8, 52.5) | 45 | 53.5 (51.0, 56.0) | 5 | 34.3 (27.8, 41.5) | .05 |

| Primary mode of useb | .01 | ||||||

| Smoking (joint, bong, pipe, and blunt) | 38 | 40.4 (38.0, 42.8) | 37 | 47.2 (44.6, 49.9) | 1 | 22.5 (17.0, 29.2) | |

| Eating in food (brownies, cake) | 29 | 26.3 (24.2, 28.4) | 23 | 21.9 (20.0, 24.0) | 6 | 46.3 (39.0, 53.8) | |

| Take by mouth (lotion, cream) | 20 | 17.6 (16.0, 19.5) | 18 | 18.1 (16.3, 20.1) | 2 | 15.6 (10.9, 21.8) | |

| Topically (lotion, cream) | 13 | 11.2 (9.9, 12.8) | 10 | 8.8 (7.6, 10.1) | 3 | 22.5 (17.0, 29.2) | |

| Drinking in a liquid | 1 | 0.9 (0.5, 1.4) | 1 | 1.0 (0.7, 1.7) | - | - | |

| Vaporizing | 3 | 2.4 (1.8, 3.1) | 3 | 2.9 (2.2, 3.8) | - | - | |

| Other mode | 1 | 1.2 (0.8, 2.0) | - | - | 1 | 7.0 (4.1, 11.5) | |

| Source of cannabis instructions | .01 | ||||||

| Another cancer patient | 3 | 2.4 (1.8, 3.1) | 3 | 2.9 (2.2, 3.8) | - | - | |

| Cannabis store/dispensary worker | 14 | 11.3 (9.9, 12.7) | 13 | 11.8 (10.4, 13.4) | 2 | 8.6 (5.2, 1.4) | |

| Family or friend | 22 | 20.2 (18.4, 22.2) | 17 | 16.5 (14.8, 18.3) | 5 | 37.7 (30.8, 45.1) | |

| No one | 54 | 51.9 (49.5, 54.3) | 50 | 56.3 (53.8, 58.8) | 4 | 31.2 (24.7, 38.4) | |

| Nurse or physician’s assistant | 1 | 1.5 (1.0, 2.4) | - | - | 1 | 8.6 (5.2, 14.1) | |

| Oncologist involved with cancer care | 3 | 3.2 (2.4, 4.2) | 3 | 3.9 (2.9, 5.1) | - | - | |

| Pharmacist | 5 | 4.8 (3.9, 5.9) | 3 | 2.8 (2.2, 3.8) | 2 | 13.9 (9.9, 19.5) | |

| Other source | 4 | 4.1 (3.2, 5.2) | 4 | 4.9 (3.9, 6.3) | - | - | |

Note. p-values based on weighted chi-square analyses.

Assessed among individuals endorsing cannabis use since diagnosis, refused question n= 2.

Assessed among individuals endorsing cannabis use since diagnosis, refused question n= 1.

Figure 1.

Weighted Estimates of Perceived Benefits of Cannabis Among Older Adult Cancer Patients (N = 524). Note: Asked of all older adults, regardless of self-reported cannabis use. Survey item instructed “check all that apply.”

Risks.

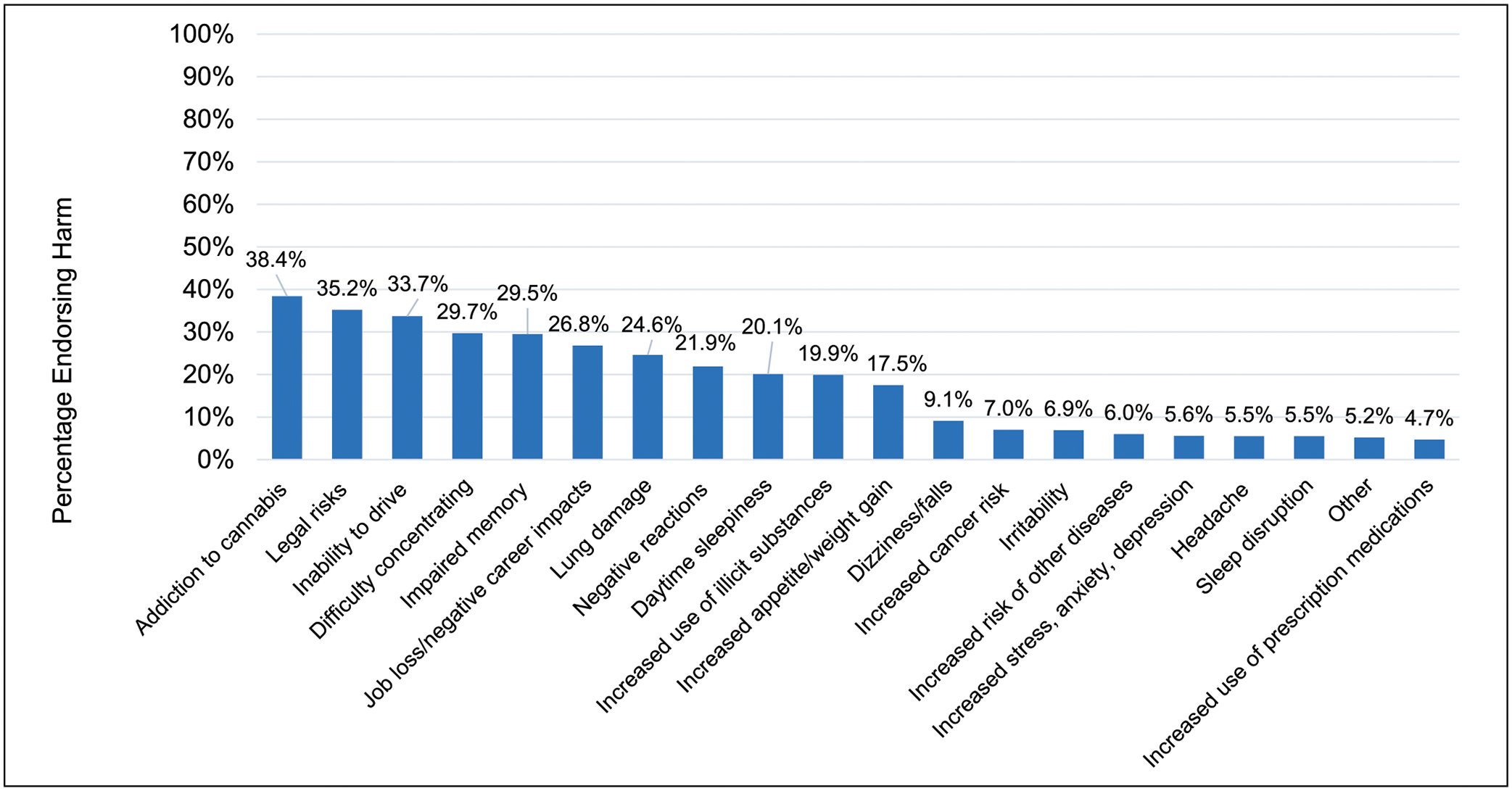

Among older adults, 68.7% believed there were risks related to cannabis use (Table 2; Figure 2). The most common perceived risk was addiction to cannabis (38.4%), followed by legal risks (35.2%), inability to drive (33.7%), and difficulty concentrating (29.7%).

Figure 2.

Weighted Estimates of Perceived Harms of Cannabis Among Older Adult Cancer Patients (N = 524). Note: Asked of all older adults, regardless of self-reported cannabis use. Survey item instructed “check all that apply.”

Age-Group Comparisons.

Older patients (75+ years) were more likely to believe there were risks to cannabis use compared to those younger (65–74 years) [χ2(1) = 12.49, p < .001] (Table 2). No difference was observed in the perception of benefits.

Cannabis Education/Instructions

An estimated 7.9% (95% CI: 7.4, 8.4) (N = 48) of the older population (N = 524) had discussed using cannabis with their provider. From response options extremely comfortable (1) to extremely uncomfortable (4), about half said they would feel extremely comfortable talking to their provider about cannabis, while about 10% endorsed feeling extremely uncomfortable. For those who used cannabis since diagnosis (N = 107), about half did not receive instructions about using cannabis from anyone, while about 20% received instructions from a friend or family member (Table 2).

Age-Group Comparisons.

Those 65–74 years were more likely to have discussed cannabis with a provider compared to those 75+ (12.2% vs. 1.5%) [χ2(1) = 20.1, p < .001] (Table 2). Of those endorsing use since diagnosis, source of cannabis instructions differed by age group [χ2(8) = 19.3, p = .01]. The most common source among those 75+ years was from a friend or family member, yet younger patients (65–74 years) were most likely to receive instructions from no one. Comfort in talking to a provider about cannabis did not differ by age (χ2(3) = 2.57, p = .46).

Patterns of Cannabis Use

Weighted prevalence estimates of lifetime cannabis use (46.0%), use since diagnosis (18.2%), and current use (9.8%) of the entire older adult population are presented in Table 2, as well as by age group. Among all who used cannabis since diagnosis (N = 107), approximately half used during their cancer treatment, and 7.0% had not yet started treatment. After diagnosis, weighted estimates indicated that the most common primary mode of use was smoking via a joint, bong, pipe, or blunt (40.4%), followed by eating cannabis in food (brownies, cakes, cookies, and candy) (26.3%).

Age-Group Comparisons.

Younger patients (65–74 years) were more likely to report ever use [χ2(1) = 33.3, p < .001], use since diagnosis [χ2(1) = 25.7, p < .001], and current use [χ2(1) = 27.0, p < .001] (Table 2). There were no age differences in cannabis use during treatment [χ2(1) = 3.69, p = .054]. Age-group differences were found by primary mode of use [χ2(6) = 18.5, p = .01]. Older patients (75+ years) had a lower prevalence of smoking compared to younger patients (22.5% vs. 47.2%, respectively), as well as a higher prevalence of consuming via food (46.3% vs. 21.9%, respectively).

Reasons for Cannabis Use

Of those using cannabis post-diagnosis (N = 107), the most common reason was for pain (estimated 44.3%; 95% CI: 41.9, 46.7) (n = 47). Others (in order of prevalence) were: 43.4% (95% CI: 41.1, 45.8) (n = 49) for help with sleeping, 38.1% (95% CI: 3.6, 4.0) (n = 39) recreationally/for enjoyment, 37.3% (95% CI: 35.0, 39.7) (n = 38) to manage stress, anxiety or depression, 20.5% (95% CI: 18.5, 22.7) (n = 18) to increase appetite, 15.0% (95% CI: 13.4, 16.8) (n = 16) for digestive problems, 10.7% (95% CI: 9.3, 12.4) (n = 11) for neuropathy relief, 8.7% (95% CI: 7.4, 10.2) (n = 9) for lack of energy/fatigue, 8.6% (95% CI: 7.3, 10.2) (n = 8) for other reason, 5.7% (95% CI: 4.6, 7.1) (n = 5) as treatment/cure for cancer, 5.4% (95% CI: 4.4, 6.5) (n = 6) for lack of sexual interest/activity, 4.8% (95% CI: 3.9, 5.9) (n = 5) for another cancer symptom or cancer treatment side effect not listed, 4.3% (95% CI: 3.5, 5.3) (n = 5) to help with concentration, 1.6% (95% CI: 1.1, 2.2) (n = 2) for skin problems, and 0.9% (95% CI: 0.5, 2.4) (n = 1) for sweating symptoms.

Symptom Management

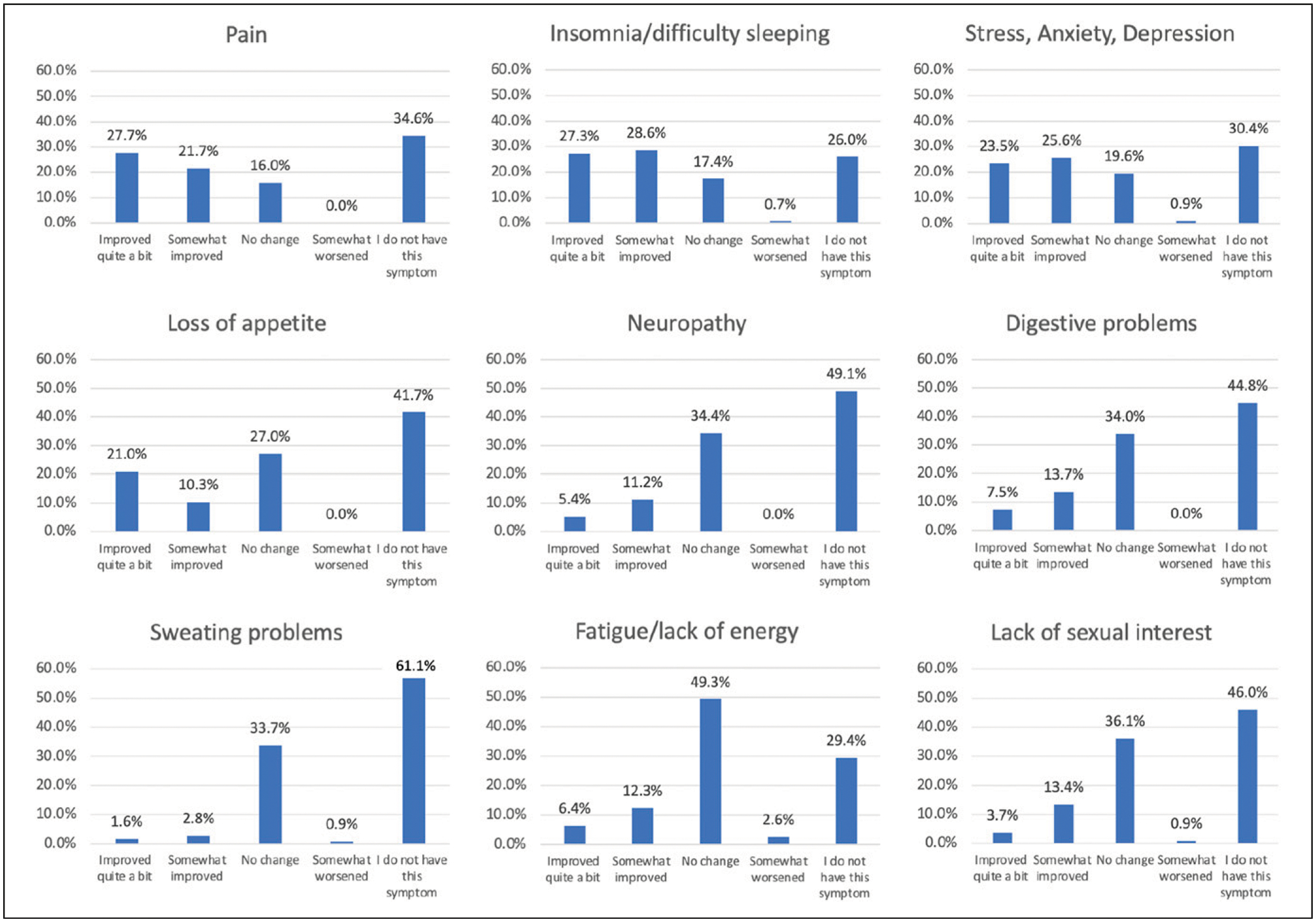

Symptom improvement (i.e., at least somewhat improved) was endorsed for pain (48%), stress, anxiety, depression (49%), insomnia (55%), and loss of appetite (31%; Figure 3). Most common symptoms that participants endorsed improved quite a bit, included pain (27.7%), followed by insomnia/difficulty sleeping (27.3%), and stress, anxiety, depression (23.5%).

Figure 3.

Symptom management following diagnosis among older patients endorsing cannabis use (N = 107).

Discussion

This study provides cross-sectional weighted estimates of cannabis perceptions and patterns of use among an older adult population (65+ years) diagnosed with cancer in an NCI-designated cancer center in a state without a legal cannabis marketplace. Most older adults (80%) believed there were benefits to using cannabis, with pain management, relief from stress, anxiety, or depression, and relief from cancer treatment side effects the most common possible benefits endorsed. Yet, over half of this population (69%) also believed there were risks, with addiction (to cannabis), legal concerns, and driving impairment among the most endorsed negative consequences. Overall, almost half (46%) had ever used cannabis, with 18% using after their diagnosis (i.e., within the past two years) and 10% currently using (i.e., within the past month). Among those using cannabis following their diagnosis, half used during treatment. These rates were largely driven by the age group 65–74 years, with patients 75+ years less likely to report lifetime, post-diagnosis, or current use of cannabis. Overall prevalence of current cannabis use was higher than national estimates of self-reported past year use in the general older adult population (4.2%), (Han & Palamar, 2020) and more consistent with a sample of older adults (8%) receiving oncology care within a state with a medical cannabis program (Rajasekhara et al., 2022). Our findings suggest it is not uncommon for older adult cancer survivors (particularly those 65–74 years) to use cannabis, even within a state without recreational or medical cannabis programs. This study underscores the importance of oncology providers assessing and discussing cannabis use with their older patients, regardless of the cannabis legalization status of their state.

Only 8% of this population had discussed the use of cannabis for cancer symptoms with their healthcare provider, although the vast majority (76%) said they would feel comfortable (or extremely comfortable) doing so. These conversations were mostly occurring among the 65–74-year age-group, with only 2% of patients 75+ years reporting provider discussions. Notably, over half (52%) who used cannabis since their diagnosis said they had not received instructions about how to use or how much to take. Given that 18% of this sample used cannabis following their cancer diagnosis, and that there are unique medical concerns when using cannabis in older age (e.g., sedation and dizziness),(Cigolle et al., 2007; Han et al., 2021; Le & Palamar, 2019; Minerbi et al., 2019) it is concerning that few received cannabis education or instructions. This evidence indicates these patients did not initiate conversations about cannabis or engage in conversations with providers and therefore could not be provided with information on possible risks, recommendations for use, and/or harm reduction strategies. For example, combustible cannabis use (e.g., joint, bong) rather than other ingestion sources (e.g., edibles) is associated with risk of negative pulmonary and respiratory outcomes (Ribeiro & Ind, 2016). There are also unique considerations when consuming edible cannabis in older age, such as changes in metabolism (Minerbi et al., 2019). Given lower national rates of cannabis use in older age compared to other age groups, providers might presume older adults are not using cannabis (Han & Palamar, 2020). However, results presented here suggest older adults are indeed using cannabis, and they are comfortable discussing this with their providers. The increasing prevalence rate of cannabis within older adults(Han & Palamar, 2020) further supports the assessment and discussion of cannabis among oncology patients across the lifespan.

Pain and sleeping difficulty were the most common reasons older adults used cannabis following their diagnosis. These reasons could be because pain and insomnia are common medical concerns among both older adults in the general population and cancer survivors of all ages (Cigolle et al., 2007; Slade et al., 2020). However, almost half (43%) of this population who endorsed cannabis use following diagnosis did not use cannabis during cancer treatment. Therefore, these symptoms might not be cancer treatment specific. It will also be important for oncology providers to consider that older patients may be managing pain and sleeping difficulty with cannabis, but not disclosing this information for a myriad of stigma or legality-related reasons.

Compared to the larger parent study (N = 1036; patients aged 18+) (McClure et al., 2023), post-diagnosis (18% vs. 26%, respectively), and current use, (10% vs. 15%) rates were somewhat lower within this older (65+) population. Most common reasons for using post-diagnosis (i.e., pain and sleep) were consistent with the larger sample. Comparisons with this larger sample indicate older cancer survivors use cannabis at comparative (yet lower) rates and for similar reasons as younger ages.

Most older adults believed that cannabis either improved or did not change their treatment symptoms. Very few (3% or less) indicated that cannabis had worsened any of their symptoms. In fact, about half believed that cannabis improved their pain, and more than half (56%) believed it improved their sleep. Yet, these self-reports are retrospective, and symptoms may not have been cancer treatment specific. It is also unknown if evidence-based treatment approaches for pain, difficulty sleeping, and other symptoms were attempted previously and were unsuccessful. Longitudinal evidence is needed to better understand how cannabis impacts pain and insomnia, as well as other relevant symptoms, in this population.

Older patients (75+ years) were more likely to believe there were risks to using cannabis, less likely to have used cannabis, and more likely to have ingested cannabis in food rather than via smoking. Findings highlight developmental differences in cannabis patterns of use even within older age. As legalization of cannabis continues to increase in the U.S.(Hartman, 2022), acceptability and prevalence of cannabis might also grow in this oldest age group. Those currently 75+ years of age might be more influenced by long-term stigma and concerns for using cannabis. It is also possible that once oncology patients reach 75 years, they believe the risks of cannabis outweigh the potential benefits of personal use. Regardless, it will be important for researchers and providers to consider differential patterns of cannabis use across these two distinct age groups.

Limitations of the current study include the cross-sectional design and reliance on retrospective self-report. Future studies would benefit from assessing cannabis use with objective measurements and biochemical verification, as well as clinical outcomes and other measures obtained through the medical record. Early survey invitations included reference to cannabis, which might have elicited greater response rates among those with more positive cannabis perceptions. After study start, invitations removed cannabis language and described the study as a survey about health behavior. Further, given the definition of cannabis, this study was not able to differentiate outcomes among THC versus CBD-dominant products. Although this study was a smaller, subgroup population of the larger parent study, this sample was weighted to account for selection probabilities, non-response adjustment, and to match the sample to the target population of older adults receiving a diagnosis or cancer care at this NCI-designated cancer center. Regardless, it will be important for future studies to examine larger, diverse samples of older adult cancer patients, particularly for those 75+ years.

Conclusions

Most older adults (65+ years) at an NCI-designated cancer center in a state without a legal cannabis marketplace believed there were benefits to cannabis use, with pain and managing mental health the most common. About 18% had used cannabis since their cancer diagnosis, with pain and insomnia the most common reasons for use, though were not necessarily symptoms attributed to cancer treatment. Prevalence rates were largely driven by older adults aged 65–74 years, with those 75+ less likely to have used cannabis during all time frames assessed. Overall, among those using cannabis since diagnosis, most indicated that cannabis either improved or had no effect on their symptoms. Findings indicate that older oncology patients might commonly use cannabis to alleviate or manage health symptoms but might not initiate conversations with providers. Healthcare systems and oncology care teams require evidence-based recommendations and guidance to inform shared decision-making about cannabis with their older patients and the unique concerns faced by older adults.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the administrative supplement to the Hollings Cancer Center at the Medical University of South Carolina (P30 CA138313, Dubois; Supplement PI, McClure) from the National Cancer Institute (NCI), NIH, DHHS and National Institute on Drug Abuse (T32A007288). We acknowledge ICF for providing technical support to the supplement grantees, including advising on sampling plans and computing survey weights, and in collaboration with NCI, developing a core set of survey questions. The contents of this manuscript are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NCI.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: R. L. T. conducted consultation work with the American Society of Addiction Medicine.

References

- Arora K, Qualls SH, Bobitt J, Milavetz G, & Kaskie B (2021). Older cannabis users are not all alike: Lifespan cannabis use patterns. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 40(1), 87–94. 10.1177/0733464819894922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aviram J, Lewitus GM, Vysotski Y, Amna MA, Ouryvaev A, Procaccia S, & Meiri D (2022). The effectiveness and safety of medical cannabis for treating cancer related symptoms in oncology patients. Front Pain Res (Lausanne), 3(1), 861037. 10.3389/fpain.2022.861037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aviram J, Lewitus GM, Vysotski Y, Uribayev A, Procaccia S, Cohen I, & Meiri D (2020). Short-term medical cannabis treatment regimens produced beneficial effects among palliative cancer patients. Pharmaceuticals, 13(12), 435. 10.3390/ph13120435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babalonis S, Raup-Konsavage WM, Akpunonu PD, Balla A, & Vrana KE (2021). Delta(8)-THC: Legal status, widespread availability, and safety concerns. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res, 6(5), 362–365. 10.1089/can.2021.0097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi NG, DiNitto DM, & Marti CN (2016). Older-adult marijuana users and ex-users: Comparisons of sociodemo-graphic characteristics and mental and substance use disorders. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 165(1), 94–102. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.05.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi NG, Marti CN, DiNitto DM, & Choi BY (2018). Older adults’ marijuana use, injuries, and emergency department visits. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 44(2), 215–223. 10.1080/00952990.2017.1318891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cigolle CT, Langa KM, Kabeto MU, Tian Z, & Blaum CS (2007). Geriatric conditions and disability: The health and retirement study. Annals of Internal Medicine, 147(3), 156–164. 10.7326/0003-4819-147-3-200708070-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han BH, Brennan JJ, Orozco MA, Moore AA, & Castillo EM (2023). Trends in emergency department visits associated with cannabis use among older adults in California, 2005–2019. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 71(4), 1267–1274. 10.1111/jgs.18180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han BH, Le A, Funk-White M, & Palamar JJ (2021). Cannabis and prescription drug use among older adults with functional impairment. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 61(2), 246–250. 10.1016/j.amepre.2021.01.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han BH, & Palamar JJ (2020). Trends in cannabis use among older adults in the United States, 2015–2018. JAMA Internal Medicine, 180(4), 609–611. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.7517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han BH, Sherman S, Mauro PM, Martins SS, Rotenberg J, & Palamar JJ (2017). Demographic trends among older cannabis users in the United States, 2006–13. Addiction, 112(3), 516–525. 10.1111/add.13670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartman M (2022). Cannabis overview. National Conference of State Legislatures Retrieved from: https://www.ncsl.org/research/civil-and-criminal-justice/marijuana-overview.aspx

- Hedrickson RG, McKeown NJ, Kusin SG, & Lopez AM (2020). Accute toxicity in older adults. Toxicology Communication, 4(1), 67–70. 10.1080/24734306.2020.1852821 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Javanbakht M, Takada S, Akabike W, Shoptaw S, & Gelberg L (2022). Cannabis use, comorbidities, and prescription medication use among older adults in a large healthcare system in Los Angeles, CA 2019–2020. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 70(6), 1673–1684. 10.1111/jgs.17719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaskie B, Kang H, Bhagianadh D, & Bobitt J (2021). Cannabis use among older persons with arthritis, cancer and multiple sclerosis: Are we comparing apples and oranges? Brain Sciences, 11(5), 532. 10.3390/brainsci11050532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann CN, Kim A, Miyoshi M, & Han BH (2022). Patterns of medical cannabis use among older adults from a cannabis dispensary in New York state. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res, 7(2), 224–230. 10.1089/can.2020.0064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachman ME (2001). Adult development, psychology of. In International encyclopedia of the social and behavioral sciences (pp. 135–139). [Google Scholar]

- Le A, & Palamar JJ (2019). Oral health implications of increased cannabis use among older adults: Another public health concern? Journal of Substance Use, 24(1), 61–65. 10.1080/14659891.2018.1508518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell CJ, Jesdale BM, & Lapane KL (2021). Recent trends in cannabis use in older Americans. Annals of Internal Medicine, 174(1), 133–135. 10.7326/M20-0863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClure EA, Walters KJ, Tomko RL, Dahne J, Hill EG, & McRae-Clark AL (2023). Cannabis use prevalence, patterns, and reasons for use among patients with cancer and survivors in a state without legal cannabis access. Supportive Care in Cancer, 31(7), 429. 10.1007/s00520-023-07881-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minerbi A, Hauser W, & Fitzcharles MA (2019). Medical cannabis for older patients. Drugs & Aging, 36(1), 39–51. 10.1007/s40266-018-0616-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute (2021). Age and cancer risk. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/age

- Orimo H (2006). Reviewing the definition of “elderly”. Geriatrics and Gerontology International, 43(1), 149–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pergam SA, Woodfield MC, Lee CM, Cheng GS, Baker KK, Marquis SR, & Fann JR (2017). Cannabis use among patients at a comprehensive cancer center in a state with legalized medicinal and recreational use. Cancer, 123(22), 4488–4497. 10.1002/cncr.30879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajasekhara S, Portman DG, Chang YD, Haas MF, Randich AL, Bromberg HS, & Donovan KA (2022). Rate of cannabis use in older adults with cancer. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care, 12(2), 178–181. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2020-002384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds IR, Fixen DR, Parnes BL, Lum HD, Shanbhag P, Church S, & Orosz G (2018). Characteristics and patterns of marijuana use in community-dwelling older adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 66(11), 2167–2171. 10.1111/jgs.15507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro LI, & Ind PW (2016). Effect of cannabis smoking on lung function and respiratory symptoms: A structured literature review. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med, 26(1), 16071. 10.1038/npjpcrm.2016.71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosa WE, Chittams J, Riegel B, Ulrich CM, & Meghani SH (2020). Patient trade-offs related to analgesic use for cancer pain: A MaxDiff analysis study. Pain Management Nursing, 21(3), 245–254. 10.1016/j.pmn.2019.07.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slade AN, Waters MR, & Serrano NA (2020). Long-term sleep disturbance and prescription sleep aid use among cancer survivors in the United States. Supportive Care in Cancer, 28(2), 551–560. 10.1007/s00520-019-04849-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. (2017). Stata Statistical Software: Release. College Station, TX: StataCorp. [Google Scholar]

- State Medical Cannabis Laws. (2022). National conference of state legislatures. NCSL. https://www.ncsl.org/health/state-medical-cannabis-laws [Google Scholar]

- Subbaraman MS, & Kerr WC (2021). Cannabis use frequency, route of administration, and co-use with alcohol among older adults in Washington state. J Cannabis Res, 3(1), 17. 10.1186/s42238-021-00071-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tumati S, Lanctot KL, Wang R, Li A, Davis A, & Herrmann N (2022). Medical cannabis use among older adults in Canada: Self-reported data on types and amount used, and perceived effects. Drugs & Aging, 39(2), 153–163. 10.1007/s40266-021-00913-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinette B, Cote J, El-Akhras A, Mrad H, Chicoine G, & Bilodeau K (2022). Routes of administration, reasons for use, and approved indications of medical cannabis in oncology: A scoping review. BMC Cancer, 22(1), 319. 10.1186/s12885-022-09378-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegier P, Varenbut J, Bernstein M, Lawlor PG, & Isenberg SR (2020). No thanks, I don’t want to see snakes again”: A qualitative study of pain management versus preservation of cognition in palliative care patients. BMC Palliative Care, 19(1), 182. 10.1186/s12904-020-00683-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang KH, Kaufmann CN, Nafsu R, Lifset ET, Nguyen K, Sexton M, & Moore AA (2021). Cannabis: An emerging treatment for common symptoms in older adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 69(1), 91–97. 10.1111/jgs.16833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]