Abstract

Hypovirus infection of the chestnut blight fungus Cryphonectria parasitica results in a spectrum of phenotypic changes that can include alterations in colony morphology and significant reductions in pigmentation, asexual sporulation, and virulence (hypovirulence). Deletion of 88% [Phe(25) to Pro(243)] of the virus-encoded papain-like protease, p29, in the context of an infectious cDNA clone of the prototypic hypovirus CHV1-EP713 (recombinant virus Δp29) partially relieved virus-mediated suppression of pigmentation and sporulation without altering the level of hypovirulence. We now report mapping of the p29 symptom determinant domain to a region extending from Phe(25) through Gln(73) by a gain-of-function analysis following progressive repair of the Δp29 deletion mutant. This domain was previously shown to share sequence similarity [including conserved cysteine residues Cys(38), Cys(48), Cys(70), and Cys(72)] with the N-terminal portion of the potyvirus-encoded helper component-proteinase (HC-Pro), a multifunctional protein implicated in aphid-mediated transmission, genome amplification, polyprotein processing, long-distance movement, and suppression of posttranscriptional silencing. Substitution of a glycine residue for either Cys(38) or Cys(48) resulted in no qualitative or quantitative changes in virus-mediated symptoms. Unexpectedly, mutation of Cys(70) resulted in a very severe phenotype that included significantly reduced mycelial growth and profoundly altered colony morphology. In contrast, substitution for Cys(72) resulted in a less severe symptom phenotype approaching that observed for Δp29. The finding that p29-mediated symptom expression is influenced by two cysteine residues that are conserved in the potyvirus-encoded HC-Pro raises the possibility that these related viral-papain-like proteases function in their respective fungal and plant hosts by impacting ancestrally related regulatory pathways.

The relationship between macroscopic symptom expression and virus-mediated alterations in cellular signal transduction processes is a topic of increasing interest in contemporary virology. However, elucidation of underlying mechanisms and the identification of viral proteins responsible for these alterations can be complicated by the acute nature of many viral infections, the intensity of host defense responses, and limitations in the range of genetic manipulations available for the host organism. In this regard, the hypovirus-Cryphonectria parasitica system provides certain advantages for such studies.

Infection of the chestnut blight fungus, C. parasitica, by the prototypic hypovirus CHV1-EP713 is persistent and noncytopathic, resulting in a very consistent set of phenotypic changes (1, 22, 24, 25). These include reduced orange pigmentation (a convenient laboratory marker), reduced asexual sporulation, female infertility, and reduced virulence (hypovirulence). Robust transformation protocols are available for C. parasitica (12), allowing either expression of heterologous genes (8) or targeted disruption of endogenous genes (15, 31) in this haploid organism. Full-length infectious cDNA clones have been constructed for two hypoviruses (7, 9), and infections can be initiated by either transformation (9) or transfection (6) protocols.

The combination of the C. parasitica transformation system and infectious hypovirus cDNA clones provides a unique system for identifying virus-encoded symptom determinants. Transformation of a virus-free C. parasitica strain with a cDNA copy of the CHV1-EP713 RNA 5′-proximal coding domain, designated open reading frame (ORF) A, resulted in a white phenotype (loss of orange pigmentation) and a significant reduction in asexual sporulation, but no reduction in fungal virulence (8). The activity responsible for these phenotypic changes was subsequently mapped to the papain-like protease p29 located within the N-terminal portion of the ORF A-encoded polyprotein p69 (13). By deleting p29 in the context of the CHV1-EP713 infectious cDNA clone (recombinant virus Δp29), Craven et al. (13) were able to show that p29 was dispensable for viral replication and to demonstrate a restoration of orange pigment production and a moderate increase in conidiation relative to the wild-type CHV1-EP713-infected fungal colonies. It was thus concluded that, while nonessential for viral RNA replication or hypovirulence, p29 does contribute to specific phenotypic changes observed in CHV1-EP713-infected fungal strains. We now report as an extension of these studies the mapping of a polypeptide domain required for p29-mediated symptom expression. Additionally, we were able to identify within this domain two critically important cysteine residues reported previously to be evolutionarily conserved in the potyvirus-encoded papain-like protease HC-Pro (20).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Systematic repair of p29 deletion mutant and amino acid substitutions in the context of the CHV1-EP713 infectious cDNA clone pLDST.

Craven et al. (13) took advantage of a pair of BamHI sites at nucleotide map positions 562 and 1219 to delete 88% of the p29 coding region in the context of the infectious CHV1-EP713 cDNA clone (referred to throughout as plasmid pLDST) to produce recombinant virus Δp29. Removal of this 657-bp BamHI fragment resulted in a 219-codon in-frame deletion that fused Pro(24) with Leu(244). For the current study, a series of seven variants of Δp29 were constructed to contain progressive extensions of the p29 coding region from Leu(244) toward the N terminus (Fig. 1). Fragments spanning bases 651 to 1402, 683 to 1402, 714 to 1402, 786 to 1402, 822 to 1402, and 912 to 1402 were amplified (28) by use of the thermostable Pfu DNA polymerase (Stratagene Cloning Systems, La Jolla, Calif.) in a DNA thermal cycler (Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) with the forward and reverse primers described in the legend to Fig. 1. The resulting amplified DNA fragments were cloned into pPCR-Script SK(+) (Stratagene), digested by BamHI, and then inserted into the BamHI site (map position 562) of Δp29. The integrity of the junctions of the mutated cDNAs was confirmed by sequencing.

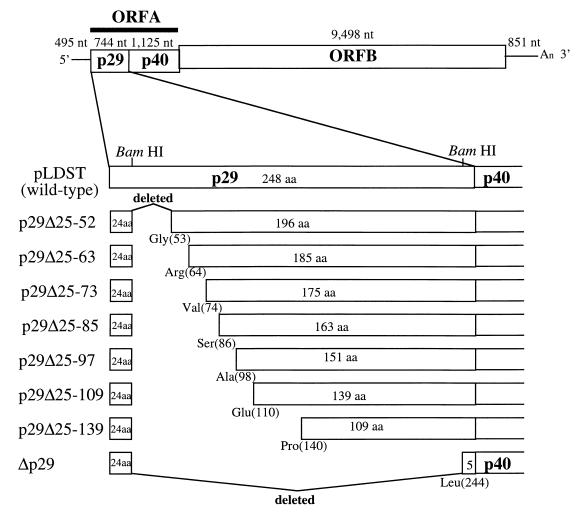

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of p29 deletion mutants used for the gain-of-function studies. The basic genome organization of CHV1-EP713 is presented at the top of the figure. ORF A encodes two polypeptides, p29 and p40, that are released from polyprotein p69 by an autocatalytic event mediated by p29. ORF B encodes a large polyprotein that contains an N-terminal papain-like protease, p48, and conserved polymerase and helicase motifs (24). A series of seven variants of Δp29 were constructed to contain progressive extensions of the p29 coding region from Leu(244) toward the N terminus. These mutants were designated p29Δ, followed by the residues that remain deleted. Thus, repair of the Δp29 mutant by extension from Leu(244) to Pro(140) gave mutant virus p29Δ25-139, i.e., which still lacked residues 25 through 139, while the most fully repaired Δp29 mutant, p29Δ25-52, still lacked amino acid residues 25 through 52. DNA fragments used in the construction of mutants were generated by PCR with the following forward primers: MGC107 (GGATCCTGGCCCGTTGTCGCATGGT, corresponding to bases 651 to 669) for p29Δ25-52, NS1 (GGATCCGCGCACCCCTGACGGGGTA, corresponding to bases 684 to 702) for p29Δ25-63, NS2 (GGATCCGGTCCACTTTGAGTTGCCG, corresponding to bases 714 to 732) for p29Δ25-73, NS3 (GGATCCTTCCACCGGAACGGTCCCG, corresponding to bases 750 to 768) for p29Δ25-85, NS4 (GGATCCGGCTGCCTTCATTGGCAGG, corresponding to bases 786 to 804) for p29Δ25-97, MGC109 (GGATCCGGAACAACGTACGAAGGAG, corresponding to bases 822 to 840) for p29Δ25-109, and MGC110 (GGATCCGCCCAGGCCAGTTCGAGGC, corresponding to bases 912 to 930) for p29Δ25-139. Each of the forward primers contains a BamHI recognition site (indicated in boldface) preceding the CHV1-713 nucleotide sequence. The common reverse primer BR54 (GGATGCTGGTGATGGCC, complementary to bases 1386 to 1402) was used in all PCRs. The resulting PCR-amplified fragments were digested with BamHI and then used to substitute for the BamHI fragment of pLDST (bases 562 to 1219). Partial diagrams of the full-length wild-type CHV1-EP713 cDNA clone (pLDST) and the Δp29 mutant are shown for points of reference.

Independent site-directed mutations (glycine substitutions) of p29 residues Cys(38), Cys(48), Cys(70), and Cys(72) were made by a PCR-based technique (26) with the mutagenic primers NSM1 (GGTGGTCCCTGCGGGTGGCATAACCCTATGGGAG; nucleotides [nt] 591 to 624) for Cys(38), NSM2 (GAGTACAGAGACTCAGGTGGCGACGTGCCTGGC; nt 622 to 654) for Cys(48), NSM3 (CCCCTGACGGGGTAGGTAAGTGCCAGGTCCAC; nt 689 to 720) for Cys(70), and NSM4 (GACGGGGTATGTAAGGGCCAGGTCCACTTT; nt 694 to 729) for Cys(72). The G residues in boldface indicate the introduced mutation. Oligonucleotides BR16 (nt 364 to 381) and NS8 (nt 1233 to 1250) were used with mutagenic primers as common terminal primers in each of the four PCRs. Amplified mutagenized fragments were cloned into pPCR-Script SK(+) and subsequently digested with BamHI. The liberated fragment was used to replace the corresponding BamHI fragment (nt 562 to 1218) in pLDST. Each mutation was confirmed by sequence analysis.

Transfection of C. parasitica spheroplasts with synthetic transcripts.

In vitro transcription was performed with Stratagene reagents according to the manufacturer’s instructions. SpeI-linearized wild-type and mutant pLDST-based plasmids were used as templates in cell-free transcription reactions (6). The resulting transcripts were extracted with phenol and precipitated with ethanol. Approximately 5 μg of synthetic RNA transcript was electroporated into 5 × 105 C. parasitica EP155 (ATCC 38755) spheroplasts prepared by the method of Churchill et al. (12). Electroporation was at 1.5 kV, 200 Ω, and 25 μF with constant time in a Gene Pulser II System electroporator (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.) (6). Electroporated spheroplasts were cultured in regeneration medium for 1 week at benchtop and then transferred onto potato dextrose agar (PDA) (Difco, Detroit, Mich.) plates.

Analysis of double-stranded RNA isolated from fungal transfectants.

Fungal strains were cultured in 20 ml of EP complete medium (27) for 5 days and then harvested by filtration through Miracloth filter cloth (Calbiochem, La Jolla, Calif.). Double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) was extracted by using the protocol of Hillman et al. (16) through the RQ1 DNase (Promega, Madison, Wis.) digestion step. This RNA fraction was further treated with 10 U of S1 nuclease (U.S. Biochemicals, Cleveland, Ohio) in 200 mM NaCl–50 mM sodium acetate (pH 4.5)–1 mM ZnSO4–0.5% glycerol, followed by phenol-chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation. The quantity and quality of dsRNA preparations were examined by electrophoresis through 1.2% NuSieve (FMC BioProducts, Rockland, Maine) agarose in 1× TBE (89 mM Tris, pH 8.3; 89 mM boric acid; 2.5 mM EDTA) at a constant voltage of 100 V for 1.5 h. ClampR, a single tube reverse transcription-PCR protocol, was performed on purified viral dsRNA templates as described by Kowalik et al. (21). The 25-μl reaction mixture contained 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 50 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, dsRNA (100 ng), primer set NS7 and NS8 (10 pmol of each; see legend to Fig. 2), 1 U of avian myeloblastosis virus reverse transcriptase (Gibco-BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.), and 1 U of AmpliTaq DNA polymerase (Perkin-Elmer, Branchburg, N.J.). The reaction mixtures were incubated at 42°C for 30 min, followed by 30 PCR cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 45°C for 1.5 min, and 72°C for 2 min.

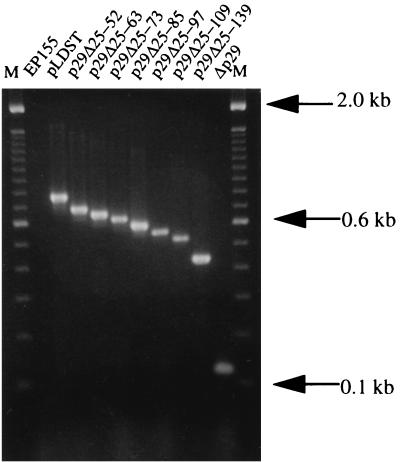

FIG. 2.

ClampR analysis of dsRNAs recovered from C. parasitica transfectants. The regions covering the deletion sites were amplified from genomic dsRNA by ClampR (21) by using the primer set NS7 (CCGAACGAGGTCCGAACA, corresponding to bases 476 to 493) and NS8 (TTCAATCGGCCGCCAATC, complementary to bases 1233 to 1250). The migration positions of DNA size marker bands (lanes marked M) are indicated at the right.

Conidiation measurements.

Asexual spores were quantified as described by Hillman et al. (16). Fungal transfectants were grown on PDA plates for 14 days at 24°C with a 16-h photoperiod at 3,300 lx in an environmentally controlled growth chamber (Percival Scientific, Inc., Boone, Iowa). Conidia were liberated with a glass rod in 15 ml of 0.15% Tween 80 and filtered through three layers of Miracloth to remove mycelial fragments. The number of spores in an appropriate dilution was quantified with the aid of a hemacytometer.

RESULTS

Viability of progressively repaired Δp29 recombinant viruses.

In an effort to map the determinants within p29 that contribute to CHV1-EP713-mediated suppression of fungal pigmentation and asexual sporulation, the Δp29 deletion mutant cDNA was systematically repaired by progressive extension of the p29 coding domain from Leu(244) toward the N terminus (Fig. 1). The resulting recombinant synthetic viral RNA transcripts were then tested for replication competence and effect on fungal phenotype. Agarose gel analysis revealed dsRNA of the expected size range in extracts from fungal colonies transfected with each of the modified mutant viral RNAs, confirming replication competence (data not shown). The integrity of the modified p29 coding region was subsequently determined for each transfectant dsRNA by ClampR analysis. With primers with the nucleotide map coordinates of 476 to 493 and 1233 to 1250, PCR-amplified fragments of 775, 688, 658, 628, 592, 556, 520, 430, and 118 bp were expected for the control transfectant infected with full-length pLDST-derived RNA transcripts and the mutant viral RNA transfectants p29Δ25-52, p29Δ25-63, p29Δ25-73, p29Δ25-85, p29Δ25-97, p29Δ25-109, p29Δ25-139, and Δp29, respectively. As indicated in Fig. 2, amplified fragments for all transfectants were of the predicted size, and no fragment was generated for the negative control (EP155). The combined results indicate that all modified p29 recombinant viral RNAs were replication competent and stably retained the appropriately altered p29 coding domain.

Effects of progressively repaired Δp29 recombinant viruses on fungal colony morphology and asexual sporulation.

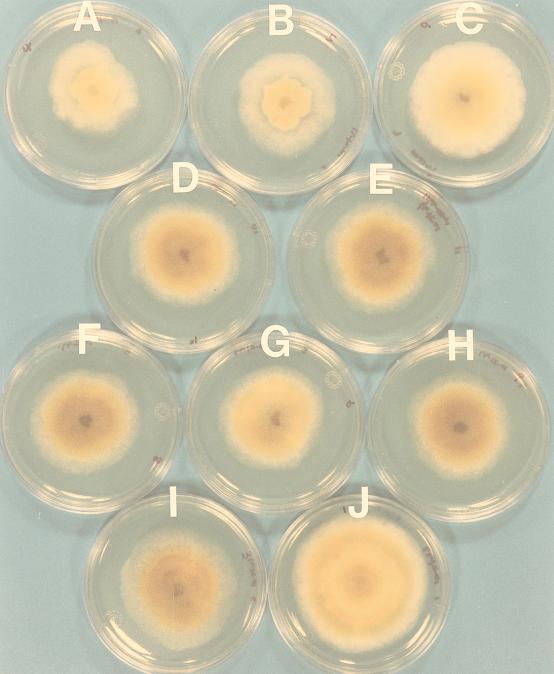

The contribution of p29 to virus-mediated alterations in colony morphology is readily observed in Fig. 3 by comparing the morphologies of colonies transfected with pLDST (colony A)- and Δp29 (colony I)-derived transcripts. Compared to virus-free strain EP155 (colony J), colonies transfected with pLDST transcripts (colony A) exhibited irregular margins, reduced growth rate, reduced aerial hyphae, and loss of orange pigmentation, as previously described for CHV1-EP713-infected strains (7). Deletion of p29 resulted in restoration of pigmentation, slightly increased growth rates, more uniform colony margins, and increased aerial hyphae (colony I). Recombinant viruses containing progressive extensions of the p29 coding domain from Leu(244) toward the N terminus to Pro(140), Glu(110), Ala(98), Ser(86), and Val(74) (colonies H, G, F, E, and D, respectively) caused symptoms indistinguishable from those induced by the Δp29 transcripts. However, a significant change in morphology was observed after extension to Arg(64) (colony C). Further extension of the p29 coding domain to Gly(53) resulted in a colony morphology (colony B) very similar to that of colonies transfected with pLDST transcripts, except that colony B contained a slight trace of orange pigmentation in the center. Thus, the domain responsible for the p29-mediated contribution to alterations in colony morphology can be defined within the N-terminal region bounded by Phe(25) and Gln(73).

FIG. 3.

Colony morphology of C. parasitica strains transfected with recombinant CHV1-EP713 p29 deletion mutants. Colonies A through I were transfected with RNA transcripts derived from CHV1-EP713 cDNA clone pLDST (A), p29Δ25-52 (B), p29Δ25-63 (C), p29Δ25-73 (D), p29Δ25-85 (E), p29Δ25-97 (F), p29Δ25-109 (G), p29Δ25-139 (H), or Δp29 (I). Colony J is uninfected strain EP155. All colonies were cultured on 10-cm PDA plates on the benchtop for 6 days at 22 to 24°C.

The effect of repaired Δp29 recombinant viruses on fungal asexual sporulation paralleled that observed for colony morphology (Table 1). Transfection with pLDST transcripts results in a significant reduction in asexual sporulation compared to the virus-free recipient strain EP155 (compare the values listed for EP155 [109 conidia/ml] with those listed for pLDST [104 conidia/ml] in Table 1). This fivefold-order-of-magnitude reduction contrasts with a 2 to 3 log reduction in sporulation observed for the Δp29 transcript. As was observed for colony morphology, no significant reduction in sporulation levels relative to the Δp29 induced levels was observed after extension of the p29 coding domain from Leu(244) to Val(74). However, a 10-fold reduction resulted after extension to Arg(64). Further extension to Gly(53) resulted in a further 10-fold reduction in sporulation, a level approaching that observed for colonies transfected with pLDST transcripts. Thus, the region identified as containing the determinant responsible for p29-mediated alteration of colony morphology also contains the determinant that contributes to the suppression of fungal asexual sporulation.

TABLE 1.

Conidiation by C. parasitica strains transfected with progressively repaired p29 deletion mutants

| Fungal strain or transfectant | Conidia/ml

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Expt 1 | Expt 2 | |

| pLDST | 3.0 × 104 | <1.0 × 104 |

| p29Δ25-52 | 5.3 × 105 | 3.0 × 104 |

| p29Δ25-63 | 1.2 × 106 | 1.8 × 105 |

| p29Δ25-73 | 1.9 × 107 | 4.0 × 106 |

| p29Δ25-85 | 1.5 × 107 | 4.3 × 106 |

| p29Δ25-97 | 2.9 × 107 | 2.4 × 106 |

| p29Δ25-109 | 2.7 × 107 | 3.7 × 106 |

| p29Δ25-139 | 2.6 × 107 | 3.1 × 106 |

| Δp29 | 1.3 × 107 | 4.2 × 106 |

| EP155 | 1.2 × 109 | 1.4 × 109 |

Role for evolutionarily conserved cysteine residues in p29-mediated symptom expression.

Choi et al. (10) previously noted similarities between p29 and the potyvirus-encoded papain-like protease HC-Pro. These similarities included conserved amino acid sequences around essential protease catalytic cysteine and histidine residues, the composition of the cleavage dipeptides, and the distances between the essential residues and the cleavage sites. Koonin et al. (20) subsequently reported a moderate level of sequence similarity for the N-terminal portions of the two proteins that was marked by conserved cysteine residues. Interestingly, these residues, Cys(38), Cys(48), Cys(70), and Cys(72), reside within the p29 symptom determinant domain identified above. The potential functional role for these conserved residues in p29-mediated symptom expression was investigated by independently substituting a glycine residue at each position within the context of the CHV1-EP713 infectious cDNA clone (plasmid pLDST). Mutation stability and dsRNA accumulation levels were verified for each mutant virus as described above (data not shown).

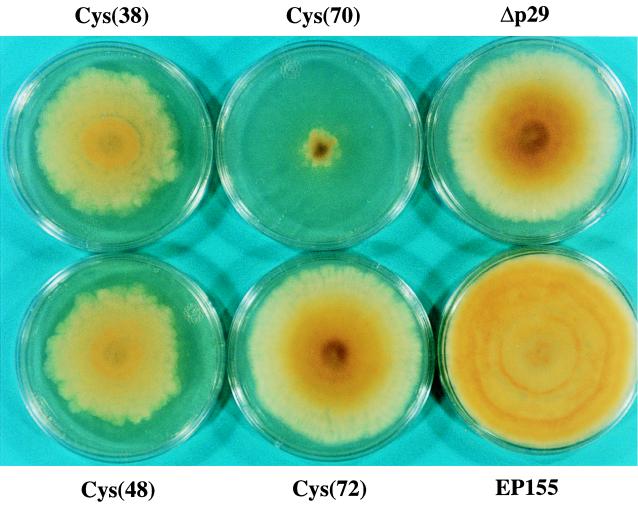

As shown in Fig. 4 and Table 2, viruses containing glycine substitutions for Cys(38) and Cys(48) caused a phenotype indistinguishable from that exhibited by parallel cultured colonies infected with pLDST transcripts. Unexpectedly, substitution of a glycine for Cys(70) resulted in a recombinant virus that significantly reduced the rate of mycelial growth and profoundly altered colony morphology, manifested primarily as the absence of aerial mycelia and reduced mycelial density. Despite the more severely reduced mycelial growth rate, colonies infected with the Cys(70) substitution mutant virus produced more than 10 times more conidia than pLDST-transfected colonies under standard experimental conditions (Table 2). However, conidium production was delayed relative to that exhibited by a wild-type virus-infected colony, with conidia first appearing within the center portion of the colony and then extending over the entire surface. Remarkably, under selected culture conditions, e.g., 25 days on the benchtop, the number of conidia produced by Cys(70) mutant transfected colonies exceeded that produced by mutant Δp29 and approached that exhibited by uninfected strain EP155 (data not shown). In contrast, substitution at Cys(72) resulted in a reduction in symptom expression resulting in a phenotype intermediate between that observed for recombinant virus p29Δ25-63 and mutant Δp29 (Fig. 4), i.e., it appeared to be more like p29Δ25-63 transfected colonies early in culturing and more like mutant Δp29 as the colony matured.

FIG. 4.

Colony morphology of C. parasitica strains transfected with p29 cysteine substitution mutant CHV1-EP713 RNAs. Colonies transfected with specific cysteine substitution mutant CHV1-EP713 RNAs are indicated by Cys(38), Cys(48), Cys(70), or Cys(72). Uninfected strain EP155 and transfectant Δp29 are included for reference. Colonies transfected with transcripts derived from CHV1-EP713 cDNA clone pLDST grown in parallel (not shown) were indistinguishable in morphology from colonies transfected with the Cys(38) and Cys(48) mutant transcripts.

TABLE 2.

Conidiation by C. parasitica strains transfected with the Cys-Gly mutants

| Fungal strain or transfectant | Conidia/ml

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Expt 1 | Expt 2 | |

| pLDST | 9.0 × 103 | 9.0 × 103 |

| Cys(38) | 2.0 × 103 | 7.0 × 103 |

| Cys(48) | 6.0 × 103 | 3.0 × 104 |

| Cys(70) | 1.0 × 105 | 5.0 × 105 |

| Cys(72) | 5.5 × 106 | 9.0 × 106 |

| Δp29 | 5.0 × 107 | 7.0 × 107 |

| EP155 | 2.0 × 109 | 3.5 × 109 |

DISCUSSION

The persistence and complexity of host phenotypic changes associated with hypovirus infection are both fundamentally intriguing and of practical significance. The pleiotropic nature of these changes suggests the possibility that hypovirus infection results in the perturbation of one or more key regulatory pathways. Efforts to test this possibility have revealed a crucial role for G-protein signal transduction in a wide range of vital physiological processes that are altered as a result of hypovirus infection, including fungal virulence (reviewed in reference 25). From an applied perspective, several hypovirulence-associated traits, e.g., reduced asexual sporulation or female infertility, negatively impact biological control efficacy by limiting hypovirus dissemination. A clear understanding of the molecular basis of hypovirus-mediated symptom expression will provide the means for further engineering hypoviruses so as to balance their effects on fungal virulence and ecological fitness, thereby affording more-effective biological control potential.

Studies identifying p29 as a hypovirus symptom determinant took advantage of both the C. parasitica transformation system and the CHV1-EP713 infectious cDNA clone pLDST (8, 13). We were able in this study to further exploit pLDST to map the p29 symptom determinant domain to a region within the N terminus extending from Phe(25) to Gln(73). The location of this domain well upstream of Cys(162) and His(215), residues required for autoproteolytic release of p29 from its polyprotein precursor at the Gly(248)-Gly(249) cleavage site (11), is consistent with the report by Craven et al. (13) that p29-mediated symptom expression is independent of intrinsic protease activity. In this regard, it is noteworthy that all of the deletions examined in this study were within the N-terminal portion of p29, extending from Met(1) to Tyr(134), that was previously shown to be dispensable for autoproteolysis (10).

Similarities between p29 and another multifunctional virus-encoded protein, the potyvirus HC-Pro protease, have been appreciated for several years (10, 20). In addition to the similarities of the C-terminal protease domains, the N-terminal domains of the two proteins contain four conserved cysteine residues that are generally considered to be an indicator of evolutionary relatedness. The fact that these conserved residues reside completely within the p29 symptom determinant domain made them attractive targets for further mutational analysis.

Previous substitution mutagenesis of the potyvirus HC-Pro domain (2) demonstrated that the cysteine residues equivalent to p29 Cys(38) and Cys(70) are essential for virus viability. Additionally, replacement of the HC-Pro counterpart of p29 Cys(48) with a serine residue resulted in symptom attenuation. In contrast, all four of the conserved hypovirus cysteine residues were dispensable for virus replication. Moreover, symptom modulation was observed for mutations of Cys(70) and Cys(72) but not for mutations of Cys(38) and Cys(48). It is intriguing that while these conserved cysteine residues retain functional significance, the phenotypic consequences associated with the mutation of the individual residues within the two viruses have become quite distinct.

The reduction in symptom expression associated with the substitution of a glycine residue for Cys(72) is consistent with a positive role for this conserved residue in p29-mediated symptom expression. Interpretation of the more severe phenotype observed for the Cys(70) substitution mutant is less straightforward. Several of the changes, such as decreased mycelial growth rate and decreased production of aerial hyphae, can be considered simply as more severe forms of the phenotypic changes caused by wild-type CHV1-EP713, i.e., pLDST transcripts. However, unlike colonies infected with CHV1-EP713, colonies infected with the Cys(70) substitution mutant did produce a considerable level of asexual spores after prolonged culturing. Thus, the phenotypic changes caused by the Cys(70) mutant differ both quantitatively and qualitatively from those caused by the wild-type virus.

There is a marked difference in the relative degree to which point mutations and systematic repair of the p29 coding domain modulate symptom expression. Gradual stepwise increases in the level of symptom expression are observed after extending the p29 coding domain from Val(74) to Arg(64) and subsequently to Gly(53) (Fig. 3 and Table 1). In contrast, mutation of Cys(72) within the context of the entire p29 coding region gives a phenotype similar to that of the p29Δ257-63 mutant, i.e., causes a greater change than deletion of residues 25 through 52. Even more surprising, site-directed mutation of Cys(70) causes symptom modulation to a greater extent than the deletion of all of p29. One interpretation of these results is that the functional integrity of the p29 symptom determinant domain, Phe(25)-Gln(73), is dependent on specific secondary or tertiary conformational constraints that are mediated by Cys(70) and Cys(72). Within this context, one could imagine that the very severe symptom modulation observed for the Cys(70) mutant is a consequence of the constitutive activation or deactivation of regulatory pathways, perhaps as a result of an altered physical interaction with a specific regulatory factor(s). Thus, this mutant may provide a particularly useful reagent in efforts to identify corresponding cellular targets of p29 action.

Similarities between HC-Pro and p29 also extend to their multifunctional nature (23). In addition to its role in facilitating aphid transmission (3, 30), HC-Pro has also been reported to catalyze polyprotein processing (4), promote potyvirus genome amplification (18, 19), stimulate vasculature-dependent long-distance movement (14), and support the transactivation of heterologous virus multiplication in mixed infections (29). Functions assigned to p29 include autoproteolysis and suppression of host processes such as laccase production, pigment production, and asexual sporulation (13). Under appropriate culture conditions, p29 also contributes to reduced mycelial growth rates and alterations in colony morphology. Moreover, p29 was found to have a differential impact on these different processes in different fungal hosts (5). It is unclear whether these multiple phenotypic effects are due to p29-mediated independent modulation of the different processes or to p29-associated perturbation of a regulatory pathway that is common to all processes. Recent studies suggest that many of the functions tentatively assigned to HC-Pro, e.g., genome activation, long-distance movement, and transactivation of heterologous virus replication, may be a manifestation of P1–HC-Pro-mediated suppression of posttranscriptional silencing by an unknown mechanism (17). Given the proposed evolutionary relationship between HC-Pro and p29, it is tempting to speculate that these two viral proteins may modulate cellular processes by interacting with ancestrally related regulatory pathways in their respective hosts. In this regard, the identification of a defined p29 symptom determinant domain and the availability of symptom-modulating site-specific p29 mutant alleles will significantly facilitate future studies on p29 mechanism of action.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

N.S. was a recipient of the research fellowship from the Uehara Memorial Foundation in 1997. This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grant GM55981 to D.L.N.

We thank Mark G. Craven for his participation in an initial step of this study and Shin Kasahara, Todd Parsley, Shaojian Gao, and Ping Wang for their helpful discussion.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anagnostakis S L. Biological control of chestnut blight. Science. 1982;215:466–471. doi: 10.1126/science.215.4532.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atreya C D, Atreya P L, Thornbury D W, Pirone T P. Site-directed mutations in the potyvirus HC-PRO gene affect helper component activity, virus accumulation, and symptom expression in infected tobacco plants. Virology. 1992;191:106–111. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90171-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atreya C D, Pirone T P. Mutational analysis of the helper component-proteinase gene of a potyvirus: effects of amino acid substitutions, deletions, and gene replacement on virulence and aphid transmissibility. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:11919–11923. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.24.11919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carrington J C, Cary S M, Parks T D, Dougherty W G. A second proteinase encoded by a plant potyvirus genome. EMBO J. 1989;8:365–370. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03386.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen B, Chen C-H, Bowman B H, Nuss D L. Phenotypic changes associated with wild-type and mutant hypovirus RNA transfection of plant pathogenic fungi phylogenetically related to Cryphonectria parasitica. Phytopathology. 1996;86:301–310. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen B, Choi G H, Nuss D L. Attenuation of fungal virulence by synthetic infectious hypovirus transcripts. Science. 1994;264:1762–1764. doi: 10.1126/science.8209256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen B, Nuss D L. Infectious cDNA clone of hypovirus CHV1-Euro7: a comparative virology approach to investigate virus-mediated hypovirulence of the chestnut blight fungus Cryphonectria parasitica. J Virol. 1999;73:985–992. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.2.985-992.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi G H, Nuss D L. A viral gene confers hypovirulence-associated traits to the chestnut blight fungus. EMBO J. 1992;11:473–477. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05077.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choi G H, Nuss D L. Hypovirulence of chestnut blight fungus conferred by an infectious viral cDNA. Science. 1992;257:800–803. doi: 10.1126/science.1496400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choi G H, Pawlyk D M, Nuss D L. The autocatalytic protease p29 encoded by a hypovirulence-associated virus of the chestnut blight fungus resembles the potyvirus-encoded protease HC-Pro. Virology. 1991;183:747–752. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)91004-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choi G H, Shapira R, Nuss D L. Co-translational autoproteolysis involved in gene expression from a double-stranded RNA genetic element associated with hypovirulence of the chestnut blight fungus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:1167–1171. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.4.1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Churchill A C L, Ciufetti L M, Hansen D R, Van Etten H D, Van Alfen N K. Transformation of the fungal pathogen Cryphonectria parasitica with a variety of heterologous plasmids. Curr Genet. 1990;17:25–31. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Craven M G, Pawlyk D M, Choi G H, Nuss D L. Papain-like protease p29 as a symptom determinant encoded by a hypovirulence-associated virus of the chestnut blight fungus. J Virol. 1993;67:6513–6521. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.11.6513-6521.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cronin S, Verchot J, Haldeman-Cahill R, Schaad M C, Carrington J C. Long-distance movement factor: a transport function of the potyvirus helper component proteinase. Plant Cell. 1995;7:549–559. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.5.549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gao S, Nuss D L. Distinct roles for two G protein α subunits in fungal virulence, morphology and reproduction revealed by targeted gene disruption. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:14122–14127. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.14122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hillman B I, Shapira R, Nuss D L. Hypovirulence-associated suppression of host functions in Cryphonectria parasitica can be partially relieved by high light intensity. Phytopathology. 1990;80:950–956. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kasschau K D, Carrington J C. A counter-defensive strategy of plant viruses: suppression of post-transcriptional gene silencing. Cell. 1998;95:461–470. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81614-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kasschau K D, Cronin S, Carrington J C. Genome amplification and long-distance movement functions associated with the central domain of tobacco etch potyvirus helper component-proteinase. Virology. 1997;228:251–262. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.8368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klein P G, Klein R R, Rodriguez-Cerezo E, Hunt A G, Shaw J G. Mutational analysis of tobacco vein mottling virus genome. Virology. 1994;204:759–769. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koonin E V, Choi G H, Nuss D L, Shapira R, Carrington J C. Evidence for common ancestry of a chestnut blight hypovirulence-associated double-stranded RNA and a group of positive-strand RNA plant viruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:10647–10651. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.23.10647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kowalik T F, Yang Y-Y, Li J K-K. Molecular cloning and comparative sequence analysis of bluetongue virus S1 segments by selective synthesis of specific full-length DNA copies of dsRNA gene. Virology. 1990;177:820–823. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90557-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.MacDonald W L, Fulbright D W. Biological control of chestnut blight: use and limitation of transmissible hypovirulence. Plant Dis. 1991;75:656–661. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maia I G, Haenni A-L, Bernardi F. Potyviral HC-Pro: a multifunctional protein. J Gen Virol. 1996;77:1335–1341. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-77-7-1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nuss D L. Biological control of chestnut blight: an example of virus- mediated attenuation of fungal pathogenesis. Microbiol Rev. 1992;56:561–576. doi: 10.1128/mr.56.4.561-576.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nuss D L. Using hypoviruses to probe and perturb signal transduction processes underlying fungal pathogenesis. Plant Cell. 1996;8:1845–1853. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.10.1845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Picard V, Ersdal-Badju E, Lu A, Bock S C. A rapid and efficient one-tube PCR-based mutagenesis technique using Pfu DNA polymerase. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:2587–2591. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.13.2587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Puhalla J E, Anagnostakis S L. Genetics and nutritional requirements of Endothia parasitica. Phytopathology. 1971;61:169–173. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saiki R K, Gelfand D H, Stoffe S, Sharf S J, Higuchi R, Horn G T, Mullis K B, Erlich H A. Primer-directed enzymatic amplification of DNA with a thermostable DNA polymerase. Science. 1988;239:487–491. doi: 10.1126/science.2448875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shi X M, Miller H, Verchot J, Carrington J C, Vance V B. Mutational analysis of the potyviral sequence that mediates potato virus X/potyviral synergistic disease. Virology. 1996;231:35–42. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thornbury D W, Hellmann G M, Rhoads R E, Pirone T P. Purification and characterization of potyvirus helper component. Virology. 1985;144:260–267. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(85)90322-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang L, Churchill A C L, Kazmierczak P, Kim D, Van Alfen N K. Hypovirulence-associated traits induced by a mycovirus of Cryphonectria parasitica are mimicked by targeted inactivation of a host gene. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:7782–7792. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.12.7782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]