Abstract

Purpose

The number of women in high-level leadership in academic medicine remains disproportionately low. Early career programs may help increase women’s representation in leadership. We evaluated the Early Career Women’s Leadership Program (ECWLP). We hypothesized that participants would rate themselves as having increased confidence in their leadership potential, improved leadership skills, and greater alignment between their goals for well-being and leading after the program. We also explored the participants’ aspirations and confidence around pursuing high-level leadership before and after the program.

Methods

We surveyed women physicians and scientists before and after they participated in the 2023 ECWLP, consisting of 11 seminars over six months. We analyzed pre- and post-program data using Wilcoxon signed-rank tests. We analyzed answers to open-ended questions with a content analysis approach.

Results

47/51 (92%) participants responded, and 74% answered pre- and post-program questionnaires. Several metrics increased after the program, including women’s confidence in their ability to lead (p<0.001), negotiate (p<0.001), articulate their career vision (p<0.001), reframe obstacles (p<0.001), challenge their assumptions (p<0.001), and align their personal and professional values (p=0.002). Perceptions of conflict between aspiring to lead and having family responsibilities (p=0.003) and achieving physical well-being (p=0.002) decreased. Perceived barriers to advancement included not being part of influential networks, a lack of transparency in leadership, and a competitive and individualistic culture. In the qualitative analysis, women described balancing internal factors such as self-doubt with external factors like competing professional demands when considering leadership. Many believed that becoming a leader would be detrimental to their well-being. Beneficial ECWLP components included support for self-reflection, tactical planning to pursue leadership, and creating a safe environment.

Conclusion

The ECWLP improved women’s confidence and strategic plans to pursue leadership in a way that supported their work-life integration. Early career leadership programs may encourage and prepare women for high-level leadership.

Keywords: faculty, gender, academic medicine, development, healthcare

Introduction

Women’s leadership programs often focus on faculty in mid- or senior career stages.1,2 Their goal is usually to support women’s career advancement and increase the number of women in “high-level” leadership positions, such as in the university dean’s or provost’s office, department directors, hospital executives, and C-suite positions. Women more often hold “low-level” leadership positions, such as education program or clinic directors, while men more often hold high-level positions.3–6 For early career women in low-level leadership positions, opportunities to advance their leadership skills are typically limited because formal leadership training is often delayed until later career stages. The rationale for delaying such training includes allowing early career faculty time to hone their clinical skills, attain grant funding, and learn how to balance multiple professional responsibilities.7,8 Many women also start families or have young children to raise soon after post-doctoral training.9 Expectations to fulfill family and professional duties and assumptions about what leadership entails may hamper women’s professional advancement and diminish some women’s enthusiasm to pursue high levels of leadership.10,11 As a result, many women’s first opportunities to explore whether they want to lead at a high level occur many years into their careers.

The benefits of having women in leadership are well established in business sectors, including greater innovation and insights into how to support the workforce.12 However, the overall impact of women as leaders in academic medicine remains understudied,13 perhaps due to the disproportionately low number of women in high-level leadership positions. Though 45% of full-time medical school faculty consist of women, only 24% of department directors and 27% of medical school deans were women in 2023. Only modest gains occurred between 2016 and 2023, with a 7% increase in women department directors and an 11% increase in women deans.4 As mentioned above, numerous factors dissuade women from seeking high-level leadership positions, including confidence level and family or home responsibilities.14–16

Introducing leadership development early in women’s careers may be one strategy to attract qualified and motivated women physicians and scientists into higher levels of leadership. Learning about leadership earlier may afford women time to gain confidence in their potential as future high-level leaders, strategically plan how to achieve their goals, and hone their skills in currently held low-level leadership roles. Early leadership development may also help retain faculty at risk of leaving academic medicine.17,18

The Early Career Women’s Leadership Program (ECWLP; formerly called the Emerging Women’s Leadership Program) was created by the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine (JHUSOM) Office of Faculty’s Women in Science and Medicine in 2012.1 Feedback from more than 250 alumnae informed the program’s development. Here, we evaluated the 2023 ECWLP. We hypothesized that participants would rate themselves as having increased confidence in their leadership potential, improved leadership skills, and greater alignment between their goals for well-being and leading upon completing the program. We also explored the participants’ aspirations and confidence around pursuing high-level leadership before and after the program.

Methods

Program Description, Setting, and Participants

We conducted a mixed methods study to evaluate the ECWLP. The JHUSOM is a large academic medical center with approximately 3200 full-time faculty, of whom 47% are women. The primary goal of the ECWLP is to support the leadership development of early career women faculty at JHUSOM. The core content is derived from leadership literature,2,11,19 focusing on challenges women often face in academic medicine14,15 (Table 1). The program included 11 two- to three-hour sessions. We included in-person and virtual sessions to enhance participation. All sessions were interactive, including breakout sessions with small groups for active learning, action planning, and networking. The facilitators were senior women and men in various leadership positions, and five of the program’s nine facilitators were certified leadership coaches. Because coaching principles are increasingly recognized as central to effective leadership,20 at least one facilitator with coaching certification attended each seminar to encourage participants to adopt a coaching growth mindset21 during discussions and small group exercises. None of the program’s sessions were recorded.

Table 1.

The Early Career Women’s Leadership Program

| Program goals | ||

| 1. Clarify personal missions for career advancement. 2. Equip women with skills for professional advancement. 3. Encourage women faculty to create and seek leadership opportunities. 4. Retain women faculty by building a supportive community of peers. 5. Promote and model diversity, equity, and inclusion. | ||

| Seminar title | Facilitator’s leadership position and rank | Venue |

| 1. Understanding Yourself and Others: the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator | Senior Associate Dean and professor | In-person |

| 2. Building Resilience for Successful Academic Careers | Senior Associate Dean and professor | Virtual |

| 3. Navigating the Currency: navigating institutional systems and building networks | Senior Associate Dean and professor | Virtual |

| 4. Dispelling Myths About Gender and Ethnic Differences in Communication | Senior Associate Dean and Associate Dean (both professors) Panel: one Senior Associate Dean and professor, one associate professor, two assistant professors |

In-person |

| 5. Negotiation | Academic Program Director and professor | Virtual |

| 6. Building Your Personal Work/ Life Mission and Saying No | Advisor to the Dean’s office and professor | Virtual |

| 7. Aligning Your Core Values with Leadership Identity and Purpose | Associate Dean and professor | Virtual |

| 8. Best Practices for Mentors and Mentees | Advisor to the Dean’s office and professor | Virtual |

| 9. Being a Well-Being Centered Leader: Why It Matters and How To Do It | Chief Wellness Officer and associate professor | Virtual |

| 10. Graceful Self-Promotion | Executive Director of Faculty Development/Academic Affairs and professor | Virtual |

| 11. Leadership Panel | Senior Associate Dean and professor Panel: One associate vice provost and professor; two endowed department directors (both professors); one endowed professor |

In-person |

Additionally, we invited program participants to participate in peer coaching during the hour before the main ECWLP seminars. We provided two consecutive five-week peer coaching sessions in the same virtual or in-person format as the main seminar. A facilitator who was also a certified coach provided a brief overview of a few basic coaching principles, including the “GOOD” model (Auerbach J. College of Executive Coaching, Personal communication, September 2021) of coaching (Goals, Options, Obstacles, and Do), and participants had the opportunity to practice these concepts in groups of two to four peers. Participants could discuss any goal, and they were encouraged to share progress on their action plans for accountability. ECWLP participants were asked to keep all discussions in the program and coaching sessions confidential to promote safety and sharing.

Recruitment

We emailed an invitation to apply to the ECWLP to all faculty members who self-identified as a woman and had been at the rank of assistant professor for less than five years. Faculty could self-nominate or be nominated by a department or other JHUSOM leader. We asked applicants to submit a curriculum vitae and answer three short questions about an example of work they were proud of, why they wanted to attend the ECWLP, and what they hoped to gain by participating in the program.

We initially planned the 2023 program to have 50 participants; we received 53 applications. All applicants were accepted. Two subsequently withdrew due to unexpected problems related to family care. Thus, 51 participants attended the ECWLP from January to June 2023. Of the 51 participants, fourteen signed up for peer coaching. Nine participants joined peer coaching for five weeks, and five participated for ten weeks. There was no cost to participate in the ECWLP, offered through the Office of Faculty in the JHUSOM’s Dean’s Office.

Program Evaluation

We developed pre- and post-program questionnaires based on the literature,15,22–24 prior program evaluations, and author experience.1,19,25,26 The pre-program questionnaire consisted of five categories of items with Likert-type response options, four questions with open-ended prompts, and questions about the participants’ career path and leadership experience (Appendix 1). The post-program questionnaire consisted of Likert-type items from four categories of the pre-questionnaire and seven open-ended questions. The five categories of Likert-type items were: (1) self-rated skills and confidence in leading; (2) confidence in applying basic leadership coaching principles; (3) conflict or alignment between pursuing leadership and potential competing factors; (4) barriers to career advancement; and (5) desired leadership positions. Questions in Categories 1–3 and 5 were asked before and after the program. Questions in Category 4 were asked only in the pre-program questionnaire.

Open-ended questions in the pre- and post-program questionnaires invited participants to comment on their goals for the program, leadership aspirations and identity, personal values, barriers to leadership, the program’s impact, and action plans moving forward.

We piloted the questionnaire twice among three individuals with high-level leadership positions in the JHUSOM and revised it for brevity. The pre-program questionnaire was emailed by Qualtrics (Seattle, WA) to the participants’ Email addresses three times during the month before the ECWLP, with one follow-up Email to non-responders. The post-program was emailed by Qualtrics on the ECWLP’s last day to all participants, with four follow-up emails over the following six weeks to non-responders. No compensation was offered for questionnaire completion.

We obtained ethnic and racial demographic data, information on doctoral degrees, and years at rank from the JHUSOM Office of Faculty Information. We defined racially or ethnically underrepresented groups in medicine as Black or African American; Hispanic, Latinx, or Spanish origin; American Indian or Alaska Native; or Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander.27 The JHUSOM Institutional Research Board approved this study (protocol IRB00340091), and consent to participate in the research was obtained as part of the questionnaire.

Data Analysis

Pre- and post-program data were compared for matched pre-post questionnaires by Wilcoxon signed-rank tests. We applied a Bonferroni correction to adjust for multiple comparisons within each questionnaire category. For example, for a category with 12 questions, an adjusted significance threshold of p<0.004 (0.05/12 comparisons) was considered statistically significant. Because all participants were exposed to leadership coaching content during the ECWLP, we analyzed data from participants who did or did not participate in peer coaching in the aggregate. Analyses were conducted using Stata version 13.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX), and graphs were made using GraphPad Prism 9.4.1 (Boston, MA).

Open-ended comments were deidentified and analyzed using a content analysis approach. Two authors (RBL and JKL) read through all comments to create provisional codes. Then, they validated the coding scheme and agreed on a final coding template that they reapplied to the comments. Codes were reviewed to identify patterns and relationships and to create thematic categories for presentation. RBL is a professor and general internist with qualitative research expertise related to women in academic medicine, sponsorship, imposter phenomenon, and leadership development. She designs and facilitates leadership development programs. JKL is a professor and anesthesiologist with research and programmatic experience in women’s leadership and professional development. She also facilitates and designs leadership and career development programs. RBL and JKL hold high-level leadership positions at their institution and are leadership coaches.

Results

Of the 51 participants, 47 (92%) agreed to join the research study and answered at least one questionnaire. Thirty-seven of the 47 (79%) answered the pre- and post-program questionnaires and were included in pre-post statistical comparisons. Respondents were predominantly clinician-scientists; 17% were from a racially or ethnically underrepresented group (Table 2). At JHUSOM, 10% of all full-time faculty are racially or ethnically underrepresented in medicine. Participants were from 17 departments within the JHUSOM, and most (58%) did not hold a recognized leadership role.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Faculty in the Early Career Women’s Leadership Program (ECWLP) Who Consented to the Research Study

| Characteristic | All Respondents (n=47) | Respondents who Answered Both Pre- and Post-Program Questionnaires (n=37) |

|---|---|---|

| Underrepresented in medicine by race or ethnicity (n [%]) | 8 (17) | 6 (16) |

| Race (n [%]) | ||

| White | 32 (68) | 25 (68) |

| Asian | 6 (13) | 6 (16) |

| Black or African American | 1 (2) | 4 (10) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 4 (9) | 1 (3) |

| Mixed | 2 (4) | 1 (3) |

| Prefer not to answer | 2 (4) | 0 (0) |

| Ethnicity (n [%]) | ||

| Not Hispanic | 43 (91) | 34 (92) |

| Hispanic | 4 (9) | 3 (8) |

| Years at rank (mean [SD]) | 1.6 (1.2) | 1.7 (1.2) |

| Doctoral degree (n) | ||

| MD or DO | 27 (58) | 19 (51) |

| PhD | 10 (21) | 10 (27) |

| MD, PhD | 9 (19) | 8 (22) |

| PhD, DVM | 1 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Career path (n [%])a | ||

| Clinician | 6 (13) | 3 (8) |

| Clinician-educator | 6 (13) | 4 (11) |

| Clinician-scientist | 24 (51) | 21 (57) |

| Scientist | 7 (15) | 7 (19) |

| Other | 2 (4) | 2 (5) |

| Held at least one recognized leadership position during the ECWLP (n [%]) | ||

| Yes | 19 (42)a, b | 14 (38)c |

| No | 26 (58) | 23 (62) |

Notes: aTwo respondents skipped this question. bSome participants held several leadership positions, including: director, co-director, or assistant director of a clinic or clinical program (11); director or co-director of a clinical rotation or course (5); leader of a research program or program within a research center (5); director or associate director of an educational program, such as a fellowship (3); director of a diversity program (1). cSome participants who answered the pre- and post-program questionnaires held several leadership positions, including: director, co-director, or assistant director of a clinic or clinical program (9); director or co-director of a clinical rotation (4); leader of a research program or program within a research center (3); associate director of an educational program, such as a fellowship (2); director of a diversity program (1).

Abbreviation: SD, Standard deviation.

Self-Rated Skills and Confidence in Leading

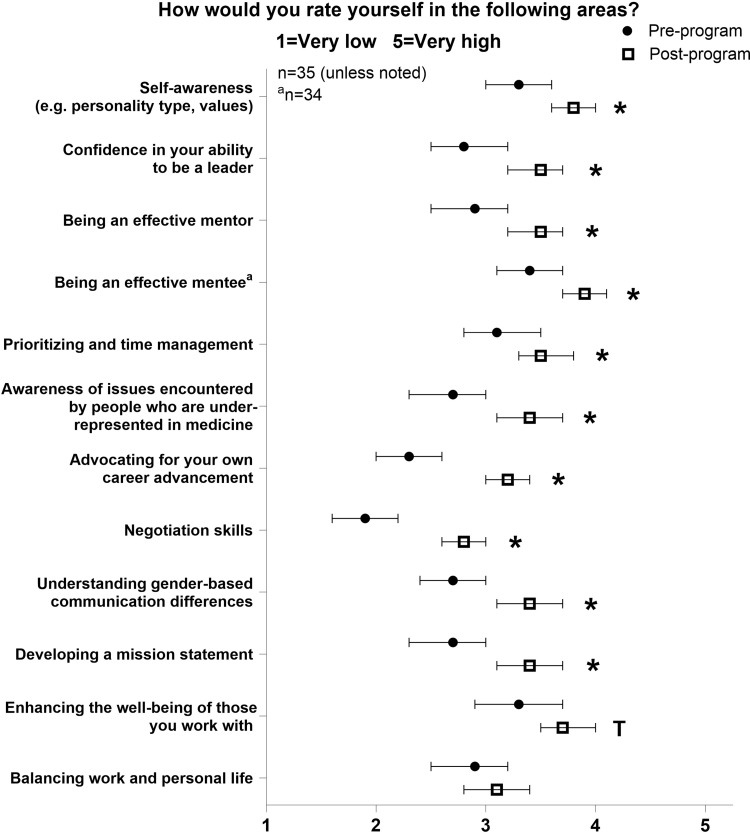

Before and after the ECWLP, participants reported significant improvements in ten of twelve self-rated skills and perceptions related to leadership (Figure 1). They reported an increase in self-awareness (p=0.001), including awareness of their personality type and personal values, and confidence in their ability to be a leader (p<0.001). Mentorship skills improved from the perspective of being a mentor (p=0.001) and a mentee (p=0.001). Respondents also noted improved prioritization and time management (p=0.004) skills, greater awareness of issues encountered by people who are underrepresented in medicine (p<0.001), and increased ability to advocate for their own career advancement (p<0.001). Negotiation skills (p<0.001), awareness of gender-based differences in communication (p<0.001), and the ability to develop a mission statement (p=0.001) improved. The ability to enhance the well-being of team members did not reach significance after Bonferroni correction (p=0.010).

Figure 1.

Leadership skills and confidence. Self-ratings in leadership skills and confidence in the ability to lead before and after the Early Career Women’s Leadership Program. *p<0.004 (0.05/12 comparisons). Tp=0.01. Data are shown as means with 95% confidence intervals.

Confidence in Applying Basic Leadership Coaching Principles

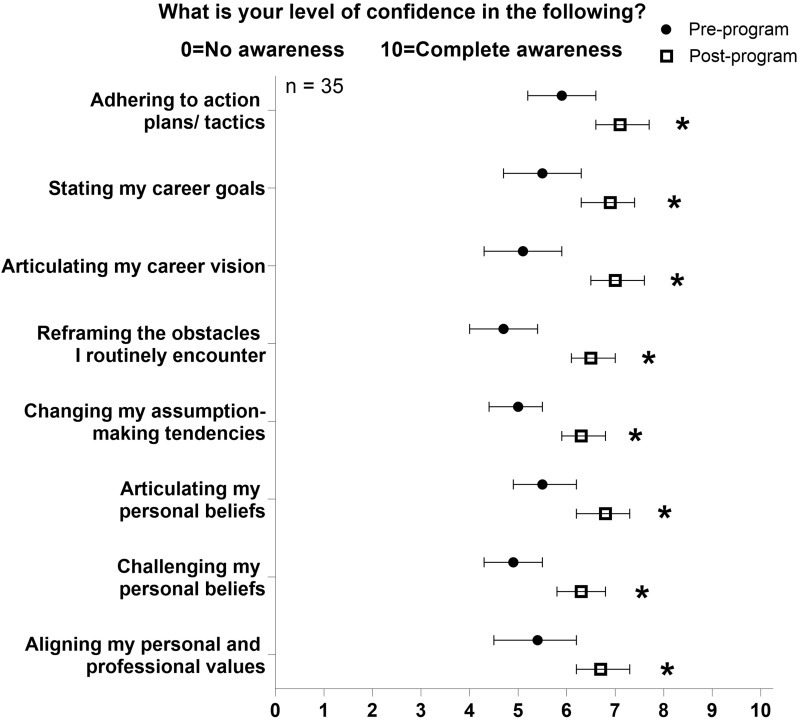

Confidence increased in all queried areas. More specifically, the participants became more confident in being able to adhere to their chosen action plans and tactics (p=0.001), state their career goals (p=0.001), and articulate their career visions (p<0.001) after completing the ECWLP (Figure 2). They felt more capable of reframing obstacles (p<0.001) and changing their tendency to make assumptions (p<0.001). They improved their abilities to articulate (p=0.001) and challenge (p<0.001) their personal beliefs. Participants also had increased confidence about aligning their personal and professional values (p=0.002).

Figure 2.

Basic leadership coaching principles. Confidence in applying basic leadership coaching principles before and after the Early Career Women’s Leadership Program. *p<0.006 (0.05/8 comparisons). Data are shown as means with 95% confidence intervals.

Conflict or Alignment Between Pursuing Higher Leadership Positions and Potential Competing Factors

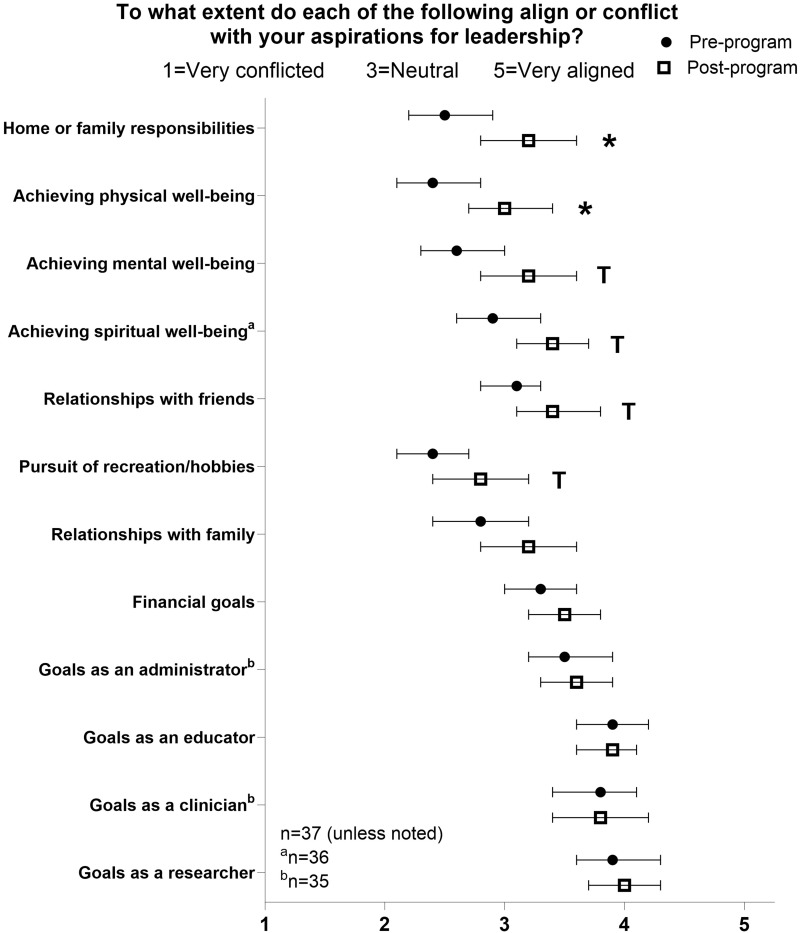

Two of the twelve factors that originally conflicted or aligned with the participants’ leadership goals changed after the program. The sense of conflict between aspiring to lead and home or family responsibilities (p=0.003) and physical well-being (p=0.002) significantly decreased after the ECWLP (Figure 3). The increase in alignment between pursuing leadership and mental (p=0.007) and spiritual (p=0.013) well-being, relationships with friends (p=0.027), and recreation or hobbies (p=0.044) did not reach statistical significance after Bonferroni correction.

Figure 3.

Alignment between leadership and other factors. Conflict or alignment between pursuing leadership and potential competing factors before and after the Early Career Women’s Leadership Program. *p<0.004 (0.05/12 comparisons). Tp<0.05. Data are shown as means with 95% confidence intervals.

Barriers to Career Advancement and Desired Leadership Positions

Participants identified several barriers to their career advancement before starting the ECWLP. The most commonly mentioned barriers were not being part of power networks that influence leadership opportunities, a lack of transparency surrounding leadership, and a work culture deemed too competitive or individualistic (n=44 participants who answered the pre-program questionnaire). Interest in different types of leadership positions did not change after the program (Supplemental Table).

Open-Ended Comments

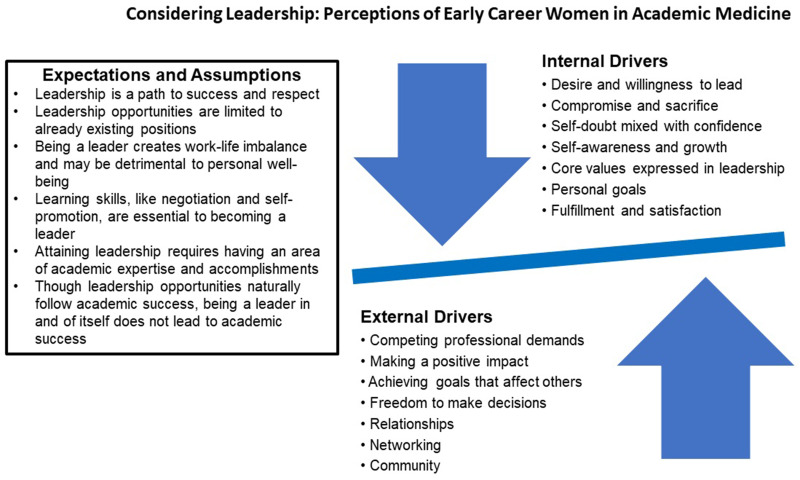

The content analysis identified several thematic categories. Internal drivers were characteristics that the participants identified in themselves. External drivers reflected the participants’ interactions with other people and situations in their environment. Before starting the program, the participants described balancing multiple factors when they considered pursuing leadership. Figure 4 shows participants’ common expectations and assumptions about leadership and the internal and external drivers they described. Table 3 provides representative quotes that show the interplay between expectations and assumptions as well as between internal and external drivers participants navigate when they consider leadership.

Figure 4.

Pre-program leadership perceptions. Views on leadership before participants took the Early Career Women’s Leadership Program. The arrows represent the balance between internal and external drivers.

Table 3.

Example Comments of How Participants Perceived Leadership Before the Early Career Women’s Leadership Program

| Attaining leadership requires having an area of academic expertise and accomplishments. Leadership is a path to success and respect. (Expectations and assumptions) Making a positive impact. Achieving goals that affect others. (External drivers) |

| “My ideal leadership position would be one in which I get to help younger people discover and pursue their goals, advocate for resources for my team, and celebrate the team’s successes – something like a division or department director. I suspect the keys to obtaining one of these positions is being academically successful, being a respected and well-known colleague, and having some prior smaller leadership roles where you can demonstrate the needed skills on a smaller scale”. |

| Self-doubt mixed with confidence. (Internal driver). |

| “After recently accepting a new role, I somewhat feel like a leader but at the same time still feel very junior in my role and I have to force myself to truly feel like a leader. I have an idea of where to begin but am not fully confident”. |

| Competing professional demands. (External driver) Compromise and sacrifice. (Internal driver) |

| “The goals of a scientist are directly at odds with (the) goals of leadership. Research takes time, attention, and mental energy. The more time you spend doing leadership activities … the less mental energy you have for moving the research forward”. |

| Though leadership opportunities naturally follow academic success, being a leader does not in and of itself lead to academic success. (Expectations and assumptions) |

| “I think I have a lot to offer, but I am finding it difficult to show those skills. The expectation seems to be that I would have skills (in) research, writing, and grantsmanship and that demonstrating these would earn me leadership opportunities. But the skills I would bring to leadership – sensitivity, compassion, creativity, transparency, (and) fairness – do not always translate into success in those other pre-requisite domains”. |

| Being a leader creates work-life imbalance and may be detrimental to personal well-being. (Expectations and assumptions) |

| “I do feel a conflict between taking on bigger responsibilities, more leadership roles, and protecting time for myself and my family outside of work. I think there is general institutional pressure to work more. … It is important to me to have a life that has some balance – rewarding work but also uninterrupted time for family, time for physical activity and sleep, etc. The leadership opportunities that have been offered to me have often felt like a threat to those things outside of work that I value so much”. |

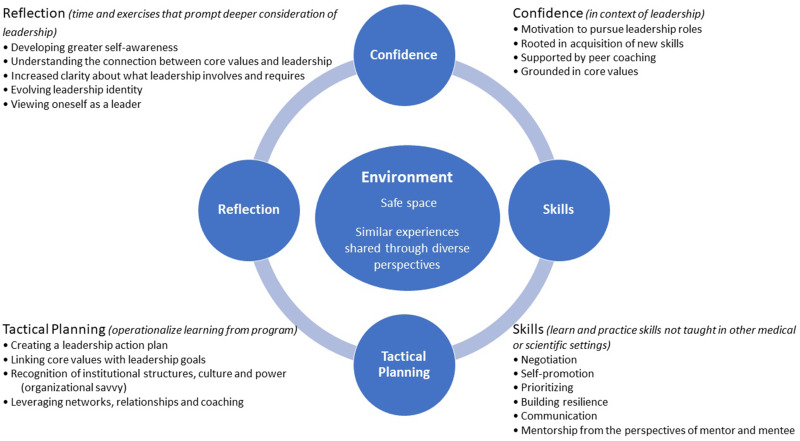

After the ECWLP, participants identified several programmatic outcomes that supported their professional growth, including reflection, confidence, skills, tactical planning, and having a safe and supportive environment to explore their leadership identities and practice skills (Figure 5). Table 4 lists quotes that illustrate these program outcomes. Table 5 summarizes common actions the participants planned for 1, 6, and 12 months after the ECWLP.

Figure 5.

Program outcomes. Key outcomes in the Early Career Women’s Leadership Program that participants deemed most beneficial.

Table 4.

Example Comments from Participants Who Completed the Early Career Women’s Leadership Program and Their Connections to Key Outcomes

| Safe space. (Environment) |

| “This environment was very supportive. I think it was great that it was comprised of early career women, so in small groups we were all in somewhat similar stages of our career and did not feel embarrassed sharing some of our concerns and reservations about our careers”. |

| Developing greater self-awareness. (Reflection) |

| “This program was great! First, it helped me find the words for how I was feeling about my career. By identifying my feelings and thoughts, I was able to be more receptive and apply lessons learned”. |

| Linking core values with leadership goals. Creating a leadership action plan. (Tactical planning) Building resilience. (Skills) |

| “The program was so timely. I had not realized how much I was struggling and how isolated I felt. The program really helped me find my love for what I do again by making me think about the things that I value and make a plan to align my vision with actions”. |

| Increased clarity about what leadership involves and requires. (Reflection) Similar experiences shared through diverse perspectives. (Environment) |

| “Hearing some of the presenters’ stories was inspirational. It was helpful for me to hear that these women (leaders) had similar obstacles that I am navigating now. Hearing the way they handled certain situations was helpful”. |

| Tactical planning. Mentorship from the perspective of mentee. Communication. Self-promotion. (Skills) |

| “This program made me more aware of how to navigate early career development and the promotions process. I am now more intentional in how I will spend the next several months to few years. I feel equipped with several strategies – having a broader pool of mentors, not being afraid to ask, not being shy to promote myself gracefully – to help do this”. |

| Evolving leadership identity. Viewing oneself as a leader. Developing greater self-awareness. (Reflection) Confidence. Prioritizing. (Skills) |

| “(After completing the program), I am a more open-minded, patient leader. I judge less harshly, am more open to different perspectives, and am better able to advocate for myself. I also more clearly recognize the value that I bring to the table and how I can maximize that by working smarter and managing my time”. |

| Understanding the connection between core values and leadership. Viewing oneself as a leader. Increased clarity about what leadership involves and requires. (Reflection) Confidence. Mentorship from the perspective of mentee. (Skills) |

| “This program helped me build confidence in who I am as a researcher, mentor, and leader in this moment, and (it) helped me identify my core values as well as skills that I need to improve on. I previously thought there were only naturally born leaders. However, I now understand that leadership is a skill that is learned over time, both from experience with excellent mentors as well as trial and error in my own leadership opportunities”. |

| Leveraging networks, relationships, and coaching. (Tactical planning). Peer coaching. (Confidence) |

| “The coaching was AMAZING and provided so much insight and accountability for me. Interacting with my peers was invaluable as it helped me realize how I was or was not getting what I deserved while expanding my network to find like-minded people that I would not have met otherwise”. |

Table 5.

Summary of the Faculty’s Common Action Plans and How These Plans Connected with the Early Career Women’s Leadership Program’s Key Outcomes (Confidence, Skills, Reflection, and Tactical Planning)

| After program completion | ||

| 1 month | 6 months | 12 months |

| Tactical planning. Communication. Recognition of institutional structure, culture, and power (organizational savvy). Linking core values with leadership goals. | ||

| •Follow-up on discussions about budget and other resources that impact programs and projects | •Articulate needs for career growth and request support | •Articulate personal values to clarify why projects are important when discussing goals and priorities with other people |

| •Prepare application for promotion | •Apply for promotion | |

| •Apply for a leadership position | ||

| Self-promotion. Motivation to pursue leadership roles. | ||

| •Seek recognition for accomplishments | •Apply for leadership opportunities in a professional society | •Seek opportunities to deliver invited lectures and disseminate work |

| •Advocate to grow and advance clinical and research programs | •Update curriculum vitae to highlight specific accomplishments and their impact | |

| •Draft own letter of recommendation | ||

| Negotiation. | ||

| •Negotiate for resources that advance clinical and research programs | •Negotiate for resources beyond salary, like more academic/non-clinical time | •Negotiate for funding |

| •Update compensation plan/contract | ||

| Mentorship from the perspectives of mentor and mentee. | ||

| •Be more direct and intentional when communicating with mentees | •Ask for mentorship from leaders internal and external to the institution | •Create a mentorship framework for the team using regular meetings and accountability |

| •Request feedback on how to improve as a mentor | •Organize a mentoring committee to advise on research progress | •Create mentorship plans for mentees |

| •Encourage others to become mentors | ||

| •As a mentee, take more ownership of tasks | ||

| Leveraging networks, relationships, and coaching. Peer coaching. | ||

| •Maintain contact with peer coaching group | •Take specific steps to regularly communicate with key people in network | •Form peer coaching groups with colleagues outside of the program |

| •Attend conferences with the goal of meeting specific people | ||

| Tactical planning. | ||

| •Be specific when clarifying and refining short- and long-term goals | •Draft a 5-year plan | •Apply for an independent grant (mentioned by select participants) |

| •Finish tasks that have been delayed | •Apply for a training grant | |

| Prioritizing. Developing greater self-awareness. | ||

| •Consider what to say “yes” or “no” to within the context of priorities | •Let go of responsibilities that do not align with career goals | • Commit to completing a project before agreeing to a new one |

| •Reduce the need to achieve perfection and submit manuscripts for peer review | •Concentrate work specifically on projects that align with career goals | |

Abbreviations: ECWLP, Early Career Women’s Leadership Program; GOOD, Goals, Options, Obstacles, Do; IRB, Institutional Review Board; JHUSOM, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine; SD, standard deviation.

Discussion

Our findings demonstrate that the ECWLP supported the leadership development of early career women physicians and scientists by building their confidence and visions of themselves as leaders. Before the ECWLP, participants shared barriers, assumptions, and expectations about leadership. These revealed some of the challenges and misconceptions women may face when deciding whether to pursue higher leadership levels. However, after completing the program, participants noted greater alignment between their leadership aspirations, home and family responsibilities, and physical well-being. Participants also reported significant improvements in key leadership skills, including self-awareness, negotiation, and the ability to advocate for their own career advancement. Confidence in applying basic leadership coaching principles, such as reframing obstacles and challenging personal assumptions, also significantly improved. Participants shared that a major benefit was the opportunity to reflect and think tactically about their path to leadership within the ECWLP’s safe and supportive environment. They finished the program with action items for 1, 6, and 12 months beyond completing the ECWLP.

Entire organizations benefit from leadership programs for women.13 Our study showed that women consider whether they are suited for leadership early in their careers. Many form uncritical opinions about what leadership entails and make choices that could impact their professional trajectory, including their ability to transition from low to high levels of leadership. Exposing women early to the scope of leadership coupled with learning tools to support the pursuit of leadership may help women identify a path forward at this critical career stage. Participants in the ECWLP expressed a clear desire and willingness to lead, and nearly half already held a low-level leadership position before beginning the program, most commonly as clinical program directors or co-directors. Skills acquired in the ECWLP may help these women succeed even more in their existing leadership roles. Such success could further build their confidence and help them advance to higher levels of leadership. Moreover, early career programs could help retain women on the path to leadership by helping them understand what to expect and build skills and networks that support ongoing achievement.

We believe that several programmatic aspects enhanced the participants’ abilities to gain new leadership skills and confidence. These included: 1. having high-level institutional leaders and certified leadership coaches as facilitators; 2. multiple opportunities in every seminar to practice new skills in small groups; 3. frequent group discussions about the discomfort, challenges, successes, and gaining confidence in applying the skills to real-life; 4. time to reflect on personal values and goals; and 5. peer coaching. Importantly, we established early expectations that faculty would actively participate in every seminar. Facilitators used open-ended questions to encourage curiosity, non-judgment, and respect for different perspectives. This encouraged participants to adopt a coaching growth mindset.21 Our efforts contributed to a psychologically safe environment28 where participants could explore new options, take risks, receive support, and feel a sense of belonging. Academic medical institutions that have or will start leadership programs can consider using these techniques to engage physicians and scientists.

The lack of women in high-level leadership positions as role models is a recognized barrier to pursuing leadership.14 To help address this problem, the ECWLP incorporated numerous opportunities for participants to meet and connect with leaders in the Dean’s office and C-suite, professors, and women with endowed chairs. We wanted the early career women to see themselves represented in spaces they had not previously considered. Exposure to candid role models may normalize the imposter phenomenon, a challenge that women physicians commonly experience29 and that hinders the professional advancement of women more than men.30 Women in the ECWLP reported benefit from hearing how high-level women leaders experienced, dealt with, and overcame career challenges. Social support is also essential to counter negative thought processes, a characteristic of the imposter phenomenon, that may be exacerbated by an individualistic and competitive culture rooted in gender stereotypes and common to academic medicine.31 Indeed, the ECWLP participants’ confidence in their ability to lead significantly grew.

Before completing the ECWLP, many participants believed leadership opportunities naturally follow academic success. However, most high-level women leaders achieve their roles through an intentional career strategy.15 The ECWLP seminars included learning and practicing skills to reduce work on projects that did not contribute to the participants’ goals. Participants also created action plans that included increasing communication with department leaders and applying for promotion or a leadership position. Conversations with department leaders about career goals and resource needs are particularly important as they may assist institutions in supporting their rising faculty.

We asked participants to consider how to collaborate with, lead, and report to people who have different values and personality types. Underrepresented women (including women of color27 and women with intersectional identities such as a different sexual orientation or disability) face especially high barriers to advancement.32 Seventeen percent of the ECWLP women were from ethnically or racially underrepresented groups in medicine.27 This exceeds the 10% of total full-time faculty who are ethnically or racially underrepresented at JHUSOM. Appreciating differences and empathy are core leadership competencies that enhance the experience of teams and organizations.33

Some aspects of well-being improved after the ECWLP. For example, graduates reported a significant decrease in the conflict between aspiring to lead vs managing home and family responsibilities and physical well-being. This change may be related to meeting role models and social support, a critical component of well-being,34 within the ECWLP. Honest discussions with cohort peers, facilitators, and the leadership panel enabled participants to recognize that they are not alone in experiencing work-life integration (WLI) challenges. Notably, the ECWLP women who already held low-level leadership positions could gain confidence in their abilities to lead and succeed at home, thereby building their confidence in pursuing higher levels of leadership in the future. By thinking about WLI early in their career, women can have realistic expectations, consider their options, and make informed choices.

However, several aspects of well-being and WLI did not significantly improve, such as the ability to balance work and personal life. This finding reflects the complexity of addressing WLI in academic medicine, and we did not expect participation in the ECWLP to address this fully. Resources for family and household duties, which often disproportionately fall on women,35–37 must be combined with systematic and cultural changes at work to improve WLI meaningfully. Leaders must support their faculty’s personal and professional choices and acknowledge the guilt experienced by many who balance family care with work.38 The ECWLP introduced techniques to support the well-being of colleagues through well-being-centered leadership because leaders should understand these principles.39 It is possible that discussions and skills about improving WLI need to be woven throughout a leadership program rather than focusing on this topic in only a few seminars. To test another technique to support well-being and WLI, we will introduce 6 months of group coaching about WLI into our Mid-Career Leadership Women’s Program using techniques that encourage self-reflection, vicarious learning, and support for meaningful change.40 We will report our results in the future.

Before the program, the participants noted several barriers to attaining leadership, including not being part of networks that influence leadership opportunities. This finding identifies an area where leaders can help improve gender equity in high-level leadership. Women should be included in social networking opportunities, including at traditionally masculine activities like sports events and other venues. Key conversations should be held at times when faculty with family responsibilities can join. Leaders must ensure that all attendees contribute their opinions at meetings. Institutional leaders can also invite younger faculty to attend important events and meetings to meet influential people, listen to discussions, and learn how high-level decisions are made.

Additional obstacles for women that have been noted in other studies include salary inequity, lack of diversity in leadership, stereotypes, gender bias and discrimination, home and family responsibilities, and lack of confidence.14,15,41,42 Leadership programs alone cannot overcome these barriers. Achieving gender equity in leadership will require dedicated effort by institutional leadership nationwide to meaningfully improve systems and culture at work.

The ECWLP participants’ interest levels in different types of leadership positions did not change after the program. Because women often underestimate their skills and qualifications,43 it is possible that the participants will need to apply their newly learned leadership skills and see success before considering high-level leadership positions. Thus, it is essential to continue leadership programs for women in their mid- and senior career stages1,2 as opportunities to pursue high-level leadership positions present. Data collection about the experiences of women faculty in our institution’s mid-career and executive leadership programs is ongoing. Additionally, we will evaluate participant experiences in an all-gender early career leadership program at our institution.

Closing the gender gap in high-level leadership will require ongoing effort and commitment by leaders at the institutional level, the continuation of women’s leadership programs, research, allyship and vigilance. It will take years for the potential benefits of programs like the ECWLP to manifest. The future of all-women leadership programs is unclear as academic medical institutions respond to concerns that single-gender programs may violate the United States Department of Education Title IX regulations, which prohibit the discrimination on the basis of sex in education programs.44 We will seek information about the status of the 2023 ECWLP graduates in a future study.

Our study had several limitations. First, the program was run at a single institution and may not be generalizable to women faculty at other institutions. Only faculty were eligible for the ECWLP and we did not have a control group. Secondly, we do not yet have long-term career outcomes from the 2023 or past programs, such as the number of women who applied for and attained high-level leadership positions. Nor do we have data on whether the participants adhered to their 1-, 6-, and 12-month action plans and plan results. Lastly, the questionnaire queried participants’ self-rated abilities and confidence rather than seeking external outcome indicators. Analyzing the performance of the ECWLP graduates by external evaluators was beyond the scope of our study.

Conclusion

The ECWLP supports the leadership development of women physicians and scientists at an early and critical stage in their careers. Participants reported significant improvements in their confidence as future leaders and in multiple skills. Key components of the ECWLP included providing a safe and supportive environment with women at similar career stages, protected time for self-reflection and learning, and tactical strategies to pursue leadership. Early leadership training may help women prepare for high-level leadership positions and is a crucial investment in academic medicine.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ann N. Conner, Senior Science Writer, from the Editorial Assistance Services Initiative at JHU for her editing assistance.

Funding Statement

There is no funding to report.

Data Sharing Statement

Data will be made available upon request by contacting the corresponding author at Jennifer.lee@jhmi.edu.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

This study was approved by the JHUSOM IRB and informed consent to participate in the research was obtained. This included consent to publish anonymized responses. (Protocol IRB00340091)

Disclosure

Dr. Lee has research funding from the National Institutes of Health, consults for the United States Food and Drug Administration and Erickson Coaching International, and owns Asclepius Coaching and Consulting, LLC. Dr. Oliva-Hemker has research funding from Takeda Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, and PredictImmune and consults for Takeda Pharmaceuticals and Janssen Research and Development. The other authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Levine RB, González-Fernández M, Bodurtha J, Skarupski KA, Fivush B. Implementation and evaluation of the Johns Hopkins university school of medicine leadership program for women faculty. J Women's Health. 2015;24(5):360–366. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2014.5092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jagsi R, Spector ND. Leading by design: lessons for the future from 25 years of the Executive Leadership in Academic Medicine (ELAM) program for women. Acad Med. 2020;95(10):1479–1482. doi: 10.1097/acm.0000000000003577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Monroe AK, Levine RB, Clark JM, Bickel J, MacDonald SM, Resar LM. Through a gender lens: a view of gender and leadership positions in a department of medicine. J Women's Health. 2015;24(10):837–842. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2014.5054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Colleges AAoM. Faculty roster: u.S. medical faculty. Available from: https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/faculty-institutions/report/faculty-roster-us-medical-school-faculty. Accessed February 7, 2024.

- 5.Chaudron LH, Harris TB, Chatterjee A, Lautenberger DM. Power reimagined: advancing women into emerging leadership positions. Acad Med. 2023;98(6):661–663. doi: 10.1097/acm.0000000000005129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gottlieb AS, Roy B, Herrin J, et al. Why are there so few women medical school deans? Debunking the myth that shorter tenures drive disparities. Acad Med. 2024;99(1):63–69. doi: 10.1097/acm.0000000000005315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee SG, Blood AJ, Kochar A. Negotiation for the early-career cardiologist. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;80(11):1110–1113. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2022.06.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lindman BR, Tong CW, Carlson DE, et al. National institutes of health career development awards for cardiovascular physician-scientists: recent trends and strategies for success. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66(16):1816–1827. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.08.858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bass RZ, Woodard SA, Colvin SD, Zarzour JG, Porter KK, Canon CL. Childbearing in radiology training and early career: challenges, opportunities, and finding the best time for you. Clin Imaging. 2022;86:67–70. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2022.03.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.James-McCarthy K, Brooks-McCarthy A, Walker DM. Stemming the ‘Leaky Pipeline’: an investigation of the relationship between work-family conflict and women’s career progression in academic medicine. BMJ Lead. 2022;6(2):110–117. doi: 10.1136/leader-2020-000436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carr PL, Helitzer D, Freund K, et al. A summary report from the research partnership on women in science careers. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(3):356–362. doi: 10.1007/s11606-018-4547-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amar S Why everyone wins with more women in leadership. Available from: https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbesbusinesscouncil/2023/02/07/why-everyone-wins-with-more-women-in-leadership/?sh=17791bcb3cdd. Accessed February 2, 2024.

- 13.Alwazzan L, Al-Angari SS. Women’s leadership in academic medicine: a systematic review of extent, condition and interventions. BMJ Open. 2020;10(1):e032232. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-032232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haines AC, McKeown E. Exploring perceived barriers for advancement to leadership positions in healthcare: a thematic synthesis of women’s experiences. J Health Organ Manag. 2023;37(3):360–378. doi: 10.1108/jhom-02-2022-0053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guptill M, Reibling ET, Clem K. Deciding to lead: a qualitative study of women leaders in emergency medicine. Int J Emerg Med. 2018;11(1):47. doi: 10.1186/s12245-018-0206-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Surawicz CM. Women in leadership: why so few and what to do about it. J Am Coll Radiol. 2016;13(12 Pt A):1433–1437. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2016.08.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Szczygiel LA, Jones RD, Drake AF, et al. Insights from an intervention to support early career faculty with extraprofessional caregiving responsibilities. Women's Health Rep. 2021;2(1):355–368. doi: 10.1089/whr.2021.0018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chang S, Morahan PS, Magrane D, et al. Retaining faculty in academic medicine: the impact of career development programs for women. J Women's Health. 2016;25(7):687–696. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2015.5608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schwartz JM, Markowitz SD, Yanofsky SD, et al. Empowering women as leaders in pediatric anesthesiology: methodology, lessons, and early outcomes of a national initiative. Anesth Analg. 2021;133(6):1497–1509. doi: 10.1213/ane.0000000000005740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Halliwell PR, Mitchell RJ, Boyle B. Leadership effectiveness through coaching: authentic and change-oriented leadership. PLoS One. 2023;18(12):e0294953. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0294953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lepre-Nolan M, Houde LD. Lessons from executive coaches: why you need one. Clin Sports Med. 2023;42(2):185–193. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2022.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Winkel AF, Telzak B, Shaw J, et al. The role of gender in careers in medicine: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative literature. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(8):2392–2399. doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-06836-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ford AY, Dannels S, Morahan P, Magrane D. Leadership programs for academic women: building self-efficacy and organizational leadership capacity. J Women's Health. 2021;30(5):672–680. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2020.8758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Edmunds LD, Ovseiko PV, Shepperd S, et al. Why do women choose or reject careers in academic medicine? A narrative review of empirical evidence. Lancet. 2016;388(10062):2948–2958. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(15)01091-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levine RB, Ayyala MS, Skarupski KA, et al. “It’s a Little Different for Men”-Sponsorship and gender in academic medicine: a qualitative study. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(1):1–8. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-05956-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Skarupski KA, Levine RB, Rand C, González-Fernández M, Clements JE, Fivush F. Impact of a leadership program for women faculty: a retrospective survey of eight years of cohort participants. J Facul Develop. 2019;33(1):7–14. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ogunyemi D, Okekpe CC, Barrientos DR, Bui T, Au MN, Lamba S. United States medical school academic faculty workforce diversity, institutional characteristics, and geographical distributions from 2014–2018. Cureus. 2022;14(2):e22292. doi: 10.7759/cureus.22292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robel S. Building leadership skills in research groups. Curr Protoc. 2022;2(6):e451. doi: 10.1002/cpz1.451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hagan AK, Pollet RM, Libertucci J. Suggestions for improving invited speaker diversity to reflect trainee diversity. J Microbiol Biol Educ. 2020;21(1). doi: 10.1128/jmbe.v21i1.2105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iwai Y, Ayl Y, Thomas SM, et al. Leadership and impostor syndrome in surgery. J Am Coll Surg. 2023;237(4):585–595. doi: 10.1097/xcs.0000000000000788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gottlieb M, Chung A, Battaglioli N, Sebok-Syer SS, Kalantari A. Impostor syndrome among physicians and physicians in training: a scoping review. Med Educ. 2020;54(2):116–124. doi: 10.1111/medu.13956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Verduzco-Gutierrez M, Wescott S, Amador J, Hayes AA, Owen M, Chatterjee A. Lasting Solutions for Advancement of Women of Color. Acad Med. 2022;97(11):1587–1591. doi: 10.1097/acm.0000000000004785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goleman D. What Makes a Leader? Harvard Business Review on Point: Boosting Your Team’s Emotional Intelligence – for Maximum Performance. Harvard Business School Publishing Corporation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shanafelt TD, Noseworthy JH. Executive leadership and physician well-being: nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(1):129–146. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Starmer AJ, Frintner MP, Matos K, Somberg C, Freed G, Byrne BJ. Gender discrepancies related to pediatrician work-life balance and household responsibilities. Pediatrics. 2019;144(4). doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-2926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Higgins MJ, Kale NN, Brown SM, Mulcahey MK. Taking family call: understanding how orthopaedic surgeons manage home, family, and life responsibilities. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2021;29(1):e31–e40. doi: 10.5435/jaaos-d-20-00182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Heo S, Chan AY, Diaz Peralta P, Jin L, Pereira Nunes CR, Bell ML. Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on scientists’ productivity in science, technology, engineering, mathematics (STEM), and medicine fields. Humanit Soc Sci Commun. 2022;9(1):434. doi: 10.1057/s41599-022-01466-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Greenbaum RL, Deng Y, Butts MM, Wang CS, Smith AN. Managing my shame: examining the effects of parental identity threat and emotional stability on work productivity and investment in parenting. J Appl Psychol. 2022;107(9):1479–1497. doi: 10.1037/apl0000597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shanafelt T, Trockel M, Rodriguez A, Logan D. Wellness-centered leadership: equipping health care leaders to cultivate physician well-being and professional fulfillment. Acad Med. 2021;96(5):641–651. doi: 10.1097/acm.0000000000003907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ostrowski E. Using group coaching to foster reflection and learning in an MBA classroom. Philos Coach. 2019;4(2):53–74. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cirincione-Ulezi N. Black women and barriers to leadership in ABA. Behav Anal Pract. 2020;13(4):719–724. doi: 10.1007/s40617-020-00444-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schizas D, Papapanou M, Routsi E, et al. Career barriers for women in surgery. Surgeon. 2022;20(5):275–283. doi: 10.1016/j.surge.2021.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hastie MJ, Lee A, Siddiqui S, Oakes D, Wong CA. Idées reçues concernant les femmes en position de leadership en médecine universitaire [Misconceptions about women in leadership in academic medicine]. Can J Anaesth. 2023;70(6):1019–1025. doi: 10.1007/s12630-023-02458-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.U.S. Department of Education releases final Title IX regulations, providing vital protections against sex discrimination. Available from: https://www.ed.gov/news/press-releases/us-department-education-releases-final-title-ix-regulations-providing-vital-protections-against-sex-discrimination. Accessed June 20, 2024.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon request by contacting the corresponding author at Jennifer.lee@jhmi.edu.