Abstract

[Purpose]

This study aimed to comprehensively explore and elucidate the intricate relationship between exercise and depression, and focused on the physiological mechanisms by which exercise influences the brain and body to alleviate depression symptoms. By accumulating the current research findings and neurobiological insights, this study aimed to provide a deeper understanding of the therapeutic potential of exercise in the management and treatment of depression.

[Methods]

We conducted a systematic review of the scientific literature by selecting relevant studies published up to October 2023. The search included randomized controlled trials, observational studies, and review articles. Keywords such as “exercise,” “depression,” “neurobiology,” “endocrinology,” and “physiological mechanisms” were used to identify pertinent sources.

[Results]

Inflammation has been linked to depression and exercise has been shown to modulate the immune system. Regular exercise can (1) reduce the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, potentially alleviating depressive symptoms associated with inflammation; (2) help in regulating circadian rhythms that are often disrupted in individuals with depression; and (3) improve sleep patterns, thus regulating mood and energy levels.

[Conclusion]

The mechanisms by which exercise reduces depression levels are multifaceted and include both physiological and psychological factors. Exercise can increase the production of endorphins, which are neurotransmitters associated with a positive mood and feelings of well-being. Exercise improves sleep, reduces stress and anxiety, and enhances self-esteem and social support. The implications of exercise as a treatment for depression are significant because depression is a common and debilitating mental health condition. Exercise is a low-cost, accessible, and effective treatment option that can be implemented in various settings such as primary care, mental health clinics, and community-based programs. Exercise can also be used as an adjunctive treatment along with medication and psychotherapy, which can enhance treatment outcomes.

Keywords: physiological effects, inflammation, depression, endorphins, social interaction, neurotransmitters

INTRODUCTION

Depression is a prevalent mental health disorder that affects millions of people worldwide. The World Health Organization identifies it as the primary cause of disability worldwide, affecting over 264 million individuals. This condition can lead to enduring feelings of sadness and diminished interest in activities, significantly influencing an individual’s daily life and overall well-being [1]. Modern treatment approaches for depression often involve psychotherapy, antidepressant medications, or a combination of these methods. Psychotherapies, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), target the modification of negative thought patterns and behaviors that play a role in depression. Antidepressant drugs, including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), work by adjusting the brain chemicals that influence mood and emotions. However, these methods have limitations. Psychotherapy can be time-consuming and expensive, and not all individuals have access to qualified therapists. The term ‘qualified therapist’ typically refers to a professional with specific credentials and training in psychotherapy. These qualifications often include advanced degrees in psychology, counseling, social work, or a related field, along with licensure or certification from relevant professional boards or organizations. Additionally, ongoing professional development and adherence to ethical guidelines are essential for maintaining one’s status as a qualified therapist. Antidepressant medications may have side effects, take several weeks to show effect, and may not be effective for everyone. Moreover, the high cost of medication and the risk of addiction and dependency are concerns associated with antidepressant medication [2]. Millions of individuals worldwide suffer from depression, a common mental health condition that makes them feel low and uninterested in their activities. Current forms of treatment for depression such as psychotherapy and antidepressant drugs have drawbacks in terms of cost, accessibility, side effects, and different levels of efficacy. Therefore, investigating alternative methods for managing depression is required. Exercise is one such strategy that has shown promise in reducing depression symptoms. Numerous pathways, including neurobiological modifications, psychological advantages, behavioral activation, and sleep regulation, play a role in the effect of exercise on depression. Healthcare providers should develop focused exercise treatments to improve treatment results and general mental health by studying the effects of exercise on depression.

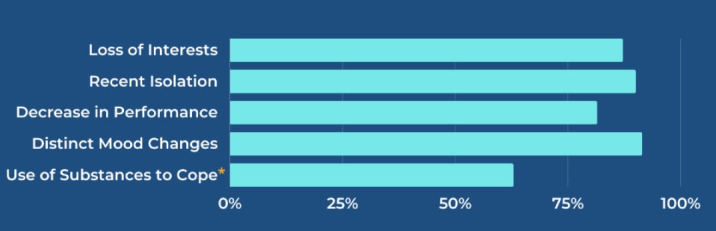

Figure 1.

Self-reported mental health signs in young adults.

As per the ‘SANDSTONE CARE Mental Health Statistics 2023’, 50% of young adults, the highest among all age groups surveyed, reported the highest severity level (5) for mental illness risk, as indicated by self-reports and assessments by loved ones. Notably, 88.57% of the young adults surpassed the treatment threshold, exhibiting three or more of the five signs of mental distress. Furthermore, studies have highlighted that young adults engage in the highest level of substance abuse as a coping mechanism, a trend consistent with addiction risk factors. An exclusive survey on substance abuse aligned with this finding, revealing that young adults self-reported the highest substance use issues (4.94 out of 6). Parents and loved ones, more than any other group, observed mood-altering substance use, underscoring the critical link between substance abuse and mental health.

POSITIVE IMPACT OF EXERCISE ON DEPRESSION

Exercise is an appealing supplementary therapy for patients with depression. Several studies have demonstrated that habitual exercise can positively affect depressive symptoms, resulting in enhanced mental health and quality of life. Physical activity alters the neurochemistry of the brain and improves neurotransmitter levels and neural function. Higher levels of neurotransmitters may assist in easing depressive symptoms such as sorrow, exhaustion, and lack of desire. In addition, exercise stimulates neuroplasticity and enhances the capacity of the brain for self-adaptation and rebuilding [3]. This promotes the development of new neurons and improves neural network connections. These neurobiological alterations may help people improve their thinking, regulate their emotions, and handle stress, all of which are essential for managing depression [4,5]. Regular exercise is implicated in several psychological aspects of depression. For example, exercise (1) promotes a shift in attention and lessens the severity of depression by diverting pessimistic thoughts to rumination; (2) provides a sense of achievement, self-efficacy, and mastery, which can raise self-esteem and self-worth, and combat depressive symptoms such as hopelessness and worthlessness; (3) reduces the physiological and psychological reactions to stress and acts as a stress buffer; and (4) reduces the damaging effects of chronic stress on mental health by lowering cortisol levels and increases calmness. Additionally, engaging in physical activities frequently entails social support and connection, which promotes a sense of belonging and decreases the feelings of isolation prevalent in depression. Declines in activity levels and interest in enjoyable activities are frequent symptoms of depression. Exercise breaks the cycle of inactivity and withdrawal, which feeds depressive symptoms by acting as a type of behavioral activation. Individuals with depression may reclaim a sense of purpose, routine, and satisfaction with their lives by setting objectives, creating habits, and reaping the benefits of exercise. Sleep issues are usually accompanied by depression and may worsen symptoms. Exercise enhances sleep hygiene by regulating sleep pattern and quality. Exercise can reduce weariness, cognitive decline, and mood disorders linked to sleep abnormalities in depression by encouraging deeper and more restorative sleep. Numerous neurological, psychological, behavioral, and sleep-related pathways are responsible for the beneficial effects of exercise on depression [6]. Healthcare providers may better customize exercise-based therapies for people with depression by studying how exercise affects depression, thereby maximizing treatment results and enhancing their overall mental health. Exercise can improve current therapeutic modalities and provide people with a proactive approach to control and avoid depressive symptoms in complete treatment regimens for depression.

RECENT STUDIES

The COVID-19 pandemic, triggered by SARS-CoV-2, has led to a sedentary lifestyle contributing to various health concerns due to decreased energy expenditure. Physical exercise, a non-pharmacological approach, significantly aids in alleviating these repercussions. SARS-CoV-2 enters cells through ACE2 receptors, resulting in inflammation and neuronal harm, which can contribute to mood disorders. Conversely, exercise enhances ACE2 expression and activates anti-inflammatory pathways. It positively influences mental health through IGF-1, BDNF, and PGC-1α/FNDC5/Irisin, counteracting the detrimental effects of SARS-CoV-2. While infection elevates ACE2 levels through pathology, exercise promotes physiological ACE2 responses and improves cardiovascular and mental well-being during a pandemic [7]. Physical exercise has been shown to have beneficial effects on the brain, particularly in older adults. Yet, there is still uncertainty regarding the precise mechanisms that differ depending on age and health conditions. This review investigates three levels of examination—molecular/cellular processes, brain structure and function, and mental states/behaviors—identifying areas of agreement, disagreement, and research gaps in the current literature. Two frameworks for inferring causality, experimental manipulation, and statistical mediation, are discussed. Recognizing the likelihood of diverse mechanisms and their dependency on age and population, this review emphasizes the need for broader consideration in future studies and models, moving beyond specific age ranges and populations to understand the multifaceted impact of exercise on the brain [8]. Regular physical activity (PA) improves cognitive function across all ages by enhancing attention, memory, and executive functions. Although the exact mechanisms remain unclear, studies have demonstrated increased neurotransmitter expression and structural changes in the brain. Functional MRI revealed altered brain networks after the exercise. PA reduces inflammation, boosts neurotrophic factor levels and improves cognitive function and connectivity. Tailoring exercise types for specific conditions has been suggested, but conclusive evidence is lacking owing to study heterogeneity. Future research should design targeted PA interventions based on age and health conditions to achieve optimal cognitive outcomes. Overall, promoting consistent PA is crucial for holistic well-being, especially in educational settings, and disease prevention in aging individuals [9]. Research and evaluation are crucial for effective clinical interventions, particularly exercise-based approaches for mental health. Tailoring methods to aims and resources, practitioners must prioritize ethical considerations, choose appropriate methodologies, justify outcome measures, and select control groups. Adequate research justifies funding, improves service delivery, and improves quality. This chapter guides exercise practitioners in mental health by emphasizing the purpose, ethics, methodology, outcome measures, and group selection, thus facilitating research and evaluation in this critical field [10].

ROLE OF INFLAMMATION ON DEPRESSION

Inflammation is a multifaceted biological reaction that occurs within the body as a defensive response to various detrimental agents such as pathogens, injured cells, or irritants. Its fundamental objectives include eliminating the source of cellular damage, clearing necrotic cells and impaired tissues resulting from the initial injury, and triggering tissue repair. While acute inflammation is a crucial part of the body’s defense system, chronic inflammation can have detrimental effects on various physiological processes, including those in the brain. Recent studies explored the relationship between inflammation and depression. While the conventional perspective on depression has centered on neurotransmitters, such as serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine, new findings indicate that inflammation significantly influences the onset and duration of depressive symptoms. Chronic inflammation can affect the brain through several pathways. One key mechanism involves the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, which are signaling molecules that mediate and regulate immune responses. In cases of chronic inflammation, like those seen in autoimmune diseases or long-lasting infections, certain cytokines can penetrate the blood-brain barrier and reach the central nervous system. Within the brain, these cytokines have the potential to induce neuroinflammation, a form of localized inflammation that occurs within the brain tissue [11]. Neuroinflammation involves the activation of microglia and other immune cells in the central nervous system. This activation prompts the release of pro-inflammatory molecules by microglia, initiating a series of inflammatory reactions. These inflammatory signals can disrupt the delicate balance between the neurotransmitters and neural circuits involved in mood regulation, leading to the development or exacerbation of depressive symptoms. Inflammation can affect the availability and function of neurotransmitters. Chronic inflammation can affect the production and release of serotonin, a neurotransmitter that regulates mood [12]. The bi-directional relationship between inflammation and depression is complex. Inflammation contributes to the onset and progression of depression; however, depressive symptoms may promote inflammation. Behavioral factors associated with depression, such as poor diet, sedentary lifestyle, and sleep disturbances, can contribute to a pro-inflammatory state in the body. Identifying the role of inflammation in depression is critical for developing novel treatment methods. Additionally, lifestyle interventions targeting inflammation, such as regular exercise and a healthy diet rich in anti-inflammatory foods, may complement traditional treatments for depression. Inflammation is a multifaceted biological response that influences various physiological processes in the body including those of the brain. The relationship between inflammation and depression involves complex interactions among immune responses, neurotransmitter systems, and neural circuits. Although further research is required to fully elucidate the mechanisms underlying this connection, a growing body of evidence highlights the importance of considering inflammation as a potential target for the prevention and treatment of depression.

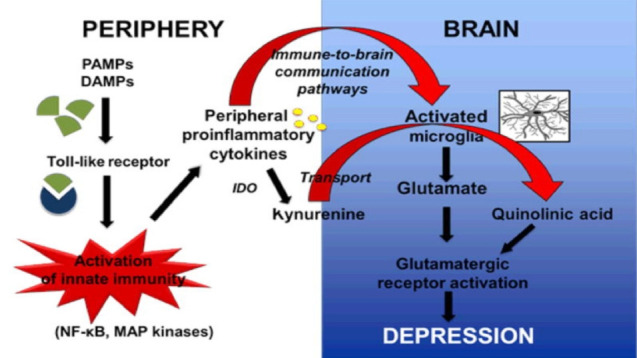

Figure 2 shows that chemicals from pathogens (PAMPs) and damaged cells (DAMPs) activate pattern recognition receptors, such as toll-like receptors, which are present on the membranes of innate immune cells [13].

Figure 2.

The pathophysiology of inflammation-induced depression.

TYPES OF EXERCISE & NEUROLOGICAL BENEFITS

Research has consistently shown that exercise is an effective treatment for depression. Different types of exercises have been studied and some examples are effective. Aerobic exercise: Aerobic exercise is any form of activity that increases the heart rate and breathing, such as yoga, swimming, or cycling. Recent studies have found that aerobic exercise is consistently effective in reducing symptoms of depression, with the greatest effect observed in individuals with mild-to-moderate depression.

The procedure is controlled by numerous interrelated brain areas, including the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) and hippocampus (HP) [1,2]. During the early stages of memory processing, the hippocampus is involved in information storage and retrieval, whereas the mPFC, which includes the anterior cingulate, prelimbic cortex, and infralimbic cortex, is involved in long-term memory consolidation and recall [3,4]. Immediate-early gene mapping and whole-brain area inhibition studies have highlighted the critical function of the mPFC in memory consolidation [5–8].

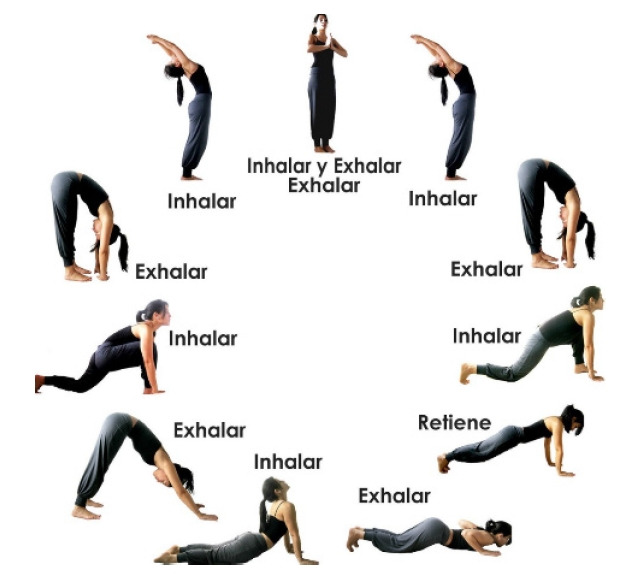

Figure 3.

Type of exercise.

• Aerobic exercise has also been shown to have positive effects on brain function, including the release of endorphins and the growth of new brain cells in areas associated with mood regulation.

• Resistance training, often known as strength training, uses weights or resistance bands to encourage muscle development. One meta-analysis found that resistance training was associated with a significant decrease in depressive symptoms. This type of exercise may be particularly beneficial for individuals who prefer low-impact activities or those with physical limitations that make aerobic exercise difficult.

• Yoga: Yoga is a mind-body practice that combines physical posture, breathing exercises, and meditation. A meta-analysis of 23 studies found that yoga was effective in reducing the symptoms of depression, with particularly strong effects observed in individuals with clinical depression. Yoga may be particularly beneficial for individuals who prefer low-impact mindfulness-based exercises.

• Mindfulness-based exercises such as tai chi or qigong involve slow, deliberate movements and focus on breathing and body awareness. A systematic review of ten studies found that mindfulness-based exercises were effective in reducing symptoms of depression, with particularly strong effects observed in older adults. These types of exercises may be particularly beneficial for individuals who prefer slower-paced, low-impact activity [14,15].

Exercise has numerous benefits for overall health, including neurological benefits. Regular exercise improves cognitive function, brain structure, and mental health. These benefits are due to various physiological changes that occur in the brain in response to exercise, including increased blood flow, BDNF production, and endorphin release. Incorporating regular exercise into a routine can contribute to overall brain health and protect against neurological disorders. One way that Exercise benefits the brain by increasing blood flow and oxygen delivery. Exercise stimulates the growth of new blood vessels in the brain, which can improve blood flow and oxygenation in brain regions involved in cognitive function [16]. Although research on the peripheral effects of exercise on the brain is extensive, its direct impact on cerebral blood vessels remains less explored. Exercise likely influences cerebral blood flow through various mechanisms, including changes in blood pressure, vascular function, and neurovascular coupling. However, the specific pathways and their implications warrant further investigation. A comprehensive understanding of the direct effects of exercise on cerebral blood vessels could help elucidate the role of exercise in neuroprotection and cognitive function [17]. This increased blood flow can also help remove waste products from the brain such as beta-amyloid, a protein associated with Alzheimer’s [18]. Physical activity also increases the synthesis of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which is an important component of neuroplasticity, or the brain’s ability to adapt to new experiences. BDNF promotes neuronal development, survival, and the formation of new synapses, possibly improving cognitive performance and providing neuroprotection from diseases. Aside from structural advantages, exercise has been demonstrated to boost cognitive function in both healthy people and those with neurological problems. For example, studies involving healthy individuals show that frequent physical exercise is associated with better performance on cognitive tests evaluating attention, memory, and executive function [19]. Exercise has been shown to improve cognitive performance in persons with neurological diseases such as Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, and stroke. It also improves mental health by reducing anxiety and depression symptoms. Physical activity increases the creation of endorphins, which are natural mood enhancers that reduce tension and anxiety. Furthermore, exercise boosts self-esteem, social involvement, and general quality of life, which improves mental health. These findings highlight the importance of exercise in boosting both cognitive performance and emotional wellness in those with neurological diseases [20].

The varied impacts of different types of exercise on depression can be attributed to psychological and social factors. The positive effect of aerobic exercise on mood and depressive symptoms is multifaceted, involving the release of endorphins, increased serotonin production, BDNF release, cortisol regulation, improved sleep, and the positive effects of distraction and social interactions. Regular participation in aerobic activities is recommended as part of a holistic approach to promote mental health and well-being. Additionally, these activities may enhance cardiovascular health and lead to better overall well-being. Strength training, on the other hand, not only promotes physical strength but also fosters a sense of accomplishment and self-esteem. Mind-body exercises, such as yoga and tai chi, focus on the integration of movement and mindfulness, offering relaxation and stress reduction benefits that can alleviate depressive symptoms. Social aspects such as group activities or team sports may provide a supportive community, combating feelings of isolation. Ultimately, the effectiveness of exercise in alleviating depression is multifaceted and is influenced by the type of activity and the individual’s preferences, needs, and overall health.

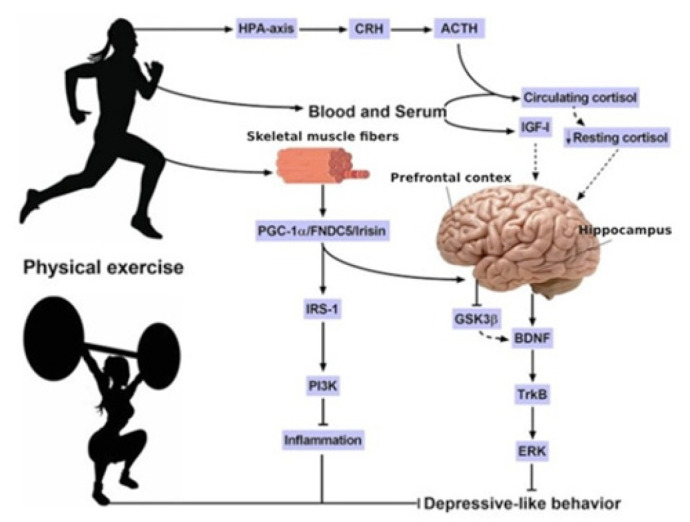

Figure 4 shows the molecular pathways involved by which physical activity helps elderly people with depression. Exercise stimulates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, which regulates the levels of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), and cortisol, resulting in lower resting cortisol levels. Aerobic and resistance exercise boosts IGF-I levels and activates the PGC-1α/FNDC5/Irisin pathway. This activation increases IRS-1 and PI3K expression and reduces inflammation, regardless of sex. The PGC-1α/FNDC5/Irisin pathway suppresses GSK3β. Furthermore, it increases BDNF and TrkB levels in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex through IGF-I, activating ERK, and ultimately alleviating depression-like symptoms [21].

Figure 4.

Benefits of exercise on the brain of elderly.

EXERCISE’S LONG-TERM MOOD EFFECTS

The long-term effects of exercise on mood are well-documented, with numerous studies showing that regular exercise can reduce depressive symptoms and improve overall well-being. A meta-analysis of 49 studies found that exercise had a moderate to substantial effect on reducing the symptoms of depression [22]. Regular exercise has been shown to have several positive effects on mood. One of the main ways that exercise can improve mood is by increasing the levels of neurotransmitters such as serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine [23]. Exercise affects the neurotransmitters that regulate mood, resulting in increased enjoyment, pleasure, and overall well-being. In addition to its effects on neurotransmitters, regular physical exercise contributes greatly to better physical health. It reduces the risk of chronic illnesses, such as diabetes and heart disease, which are known to be detrimental to mental health. Exercise also improves sleep quality, which is important for mood regulation and the relief of depressive symptoms. Research has shown that exercise has long-term effects on mood. For example, one study found that those who exercised regularly for six months had much fewer depressive symptoms than those who did not. Another trial found that exercise, like medicine, was effective in lowering depressive symptoms over 16 weeks [24]. Regular exercise can also improve the overall well-being and quality of life. In addition to reducing depressive symptoms, exercise can also increase self-esteem, improve cognitive function, and provide a sense of accomplishment and mastery. These positive effects can lead to an overall improvement in the quality of life and a reduction in stress and anxiety. Regular exercise has long-term positive effects on mood, including a reduction in depressive symptoms and improvement in overall well-being and quality of life. These effects are likely due to an increase in neurotransmitter levels, improvements in physical health, and other positive psychological benefits of exercise. Exercise should be considered a key component in the treatment of depression and the promotion of overall mental and physical health. There are several mechanisms through which exercise can reduce depression levels, including physiological, psychological, and social factors. Here are some of the mechanisms that have been proposed: Endorphin release: Exercise has been shown to stimulate the release of endorphins, which are natural mood-enhancing chemicals that can reduce feelings of pain and promote feelings of well-being [25]. These endorphins can help reduce symptoms of depression, such as sadness and fatigue. Neuroplasticity: Exercise has been shown to promote the growth of new brain cells, particularly in the hippocampus, which is a region of the brain that is involved in mood regulation and memory.

Regular exercise is widely recognized as a valuable strategy for reducing depression and improving mental well-being. Engaging in various types of exercise, including aerobics, strength training, and flexibility exercises, can positively impact mood and alleviate symptoms of depression. Aerobic exercises, such as walking, running, or cycling, stimulate the release of endorphins, which are known as “feel-good” hormones that can enhance mood. Strength training exercises involving resistance training or weight-lifting contribute to increased levels of neurotransmitters, such as serotonin, which play a crucial role in regulating mood. Additionally, flexibility exercises, such as yoga or stretching, can promote relaxation and reduce stress, further benefiting mental health. Duration and frequency of exercise play crucial roles. According to the American College of Sports Medicine, adults should aim for at least 150 min of moderate-intensity exercise per week or 75 min of vigorous-intensity exercise. Breaking this down into manageable sessions, such as 30 min a day on most days, can yield significant mental health benefits. Consistency is key because the positive effects of exercise on mood tend to accumulate over time. Incorporating a variety of exercises into routine and enjoyable activities can enhance adherence, making it more likely for individuals to sustain regular exercise habits and experience mental health benefits associated with it [26]. Social support is a key factor in reducing depression levels, and exercise can provide a social environment in which individuals can connect with others.

DEPRESSION TREATMENT WITH EXERCISE AND MEDICATION

A large body of evidence supports the use of exercise as a therapeutic intervention for depression. Numerous studies have proven its usefulness in treating depressive symptoms, and a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials published in JAMA Psychiatry in 2016 confirmed that exercise significantly reduces depression levels [27]. The study included 33 RCTs with a total of 1,877 participants and found that exercise was as effective as other treatments, such as cognitive behavioral therapy and antidepressant medications. A randomized controlled trial published in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine in 2018 found that a 12-week exercise program was effective in reducing symptoms of depression in older adults with mild-to-moderate depression. The study included 113 participants and found that the exercise program resulted in a significant reduction in depressive symptoms compared with the health education program.

A longitudinal study published in the Journal of Psychiatric Research in 2018 found that engaging in regular physical activity was associated with a lower risk of depression over time [28]. This study followed over 33,000 adults for up to 11 years and found that those who reported higher levels of mechanisms for endorphins during physical activity were less likely to develop depression.

A meta-analysis of 25 RCTs published in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews in 2013 found that exercise was effective in reducing the symptoms of depression in adults with major depressive disorder. The study included over 1,100 participants and found that exercise had a significant effect on reducing depressive symptoms compared with the no-treatment or control groups. A randomized controlled trial published in the British Journal of Sports Medicine in 2012 found that a 10-week exercise program was effective in reducing the symptoms of depression in individuals with clinical depression [29]. The study included 30 participants and found that the exercise program resulted in a significant reduction in depressive symptoms compared to the waitlist control group. Exercise can be used in conjunction with other treatments for depression such as medication and therapy. Studies have shown that exercise can enhance the effectiveness of antidepressant medication and improve the symptoms of depression in individuals receiving therapy [30,31]. Moreover, exercise provides a non-pharmacological option for individuals who choose not to depend on medication or for those who do not respond well to pharmaceutical treatments. Additionally, exercise can serve as a valuable complement to therapy, enabling individuals to actively oversee their symptoms outside of therapy sessions. While exercise is advantageous as a supplementary treatment, it should not be seen as a substitute for medication or therapy. Seeking guidance from a healthcare professional before starting an exercise regimen ensures a personalized and thorough treatment strategy that incorporates the beneficial impacts of physical activity [32]. Combining exercise with other treatments for depression can provide a comprehensive approach to manage symptoms and improve overall mental health. The amount of exercise required to reduce the symptoms of depression may vary depending on factors such as age, overall health, fitness level, and severity of depression. However, research suggests that engaging in regular PA, even at low-to-moderate levels, can have a positive impact on mental health and reduce symptoms of depression. According to the American Heart Association, adults should aim for at least 150 min of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise or 75 min of vigorous-intensity aerobic exercise per week [33]. Indeed, any amount of physical activity can improve mental health. Even modest exercise sessions, such as a 10-minute stroll, may improve mood and reduce depressive symptoms. Furthermore, the exact type of workout should be considered. According to previous research, aerobic sports, such as running, cycling, and swimming, may be particularly effective in reducing depressive symptoms. However, different types of exercises, such as strength training and yoga, have shown potential mental health advantages. Finally, the best exercise plan for treating depression may vary depending on the individual’s taste and needs [34,35]. Furthermore, individuals must discover an exercise regimen that they find enjoyable and that can be maintained over time. Collaboration with healthcare professionals is essential for developing safe and personalized exercise plans tailored to individual needs. Regular physical activity profoundly affects brain health primarily through changes in energy metabolism. Physical activity increases cerebral blood flow and oxygen levels, facilitates nutrient delivery, and eliminates metabolic byproducts. It also triggers the release of BDNF, a vital protein that supports brain plasticity and cognitive function. Moreover, aerobic exercise promotes the formation of new mitochondria and enhances glucose metabolism in the brain, thereby enhancing energy production and neuronal resilience. These metabolic adaptations significantly contribute to improved cognitive function, mood regulation, and protection against age-related cognitive decline and neurodegenerative disorders. Ultimately, exercise-induced modifications of energy metabolism play a crucial role in optimizing brain health and functionality [36,37].

DISCUSSION

Exercise has been demonstrated to have beneficial effects on mental health, particularly in the management of depression. It has been proven effective in treating depression across different groups, including clinical and non-clinical populations. This discussion examines the physiological impacts of exercise on the brain and body that contribute to the alleviation of depressive symptoms. Exercise influences the brain by triggering the release of neurotransmitters such as endorphins, serotonin, and dopamine. These neurotransmitters play crucial roles in regulating mood and emotions. Endorphins, known for producing the sensation of a “runner’s high,” are released during exercise. Serotonin, a neurotransmitter targeted by antidepressants, is also boosted by exercise, contributing to improved mood. Additionally, exercise increases dopamine levels in the brain, enhancing the brain’s reward system and fostering positive emotions, thereby aiding in the reduction of depression symptoms. Exercise not only releases neurotransmitters but also boosts levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factors (BDNF). BDNF is crucial for the growth and maintenance of brain cells and is often depleted in individuals with depression. By increasing BDNF levels, exercise enhances brain function and alleviates depressive symptoms. Additionally, exercise exerts physiological effects that mitigate depression. For instance, it reduces inflammation, a factor implicated in various mental health conditions including depression. By lowering inflammation, exercise helps to ameliorate symptoms. Furthermore, exercise improves sleep quality, which is particularly beneficial for individuals with depression who frequently experience sleep disturbances. Lastly, exercise enhances self-esteem and fosters social support, both of which play significant roles in depression treatment. Exercise can help individuals feel better about themselves and improve confidence, which can positively affect their mental health. Exercise can also provide opportunities for social interaction, which can help reduce feelings of isolation and improve social support. These effects include the release of neurotransmitters, increased BDNF levels, reduced inflammation, improved sleep quality, and improvements in self-esteem and social support. These findings highlight the importance of exercise as a treatment option for individuals with depression and suggest that exercise can be an effective complement to traditional therapies, such as medication and psychotherapy.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea Grant funded by the Korean Government (NRF-2017S1A6A3A01079869).

REFERENCES

- 1.Xie Y, Wu Z, Sun L, Zhou L, Wang G, Xiao L, Wang H. The effects and mechanisms of exercise on the treatment of depression. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:705559. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.705559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schuch FB, Vancampfort D, Richards J, Rosenbaum S, Ward PB, Stubbs B. Physical activity and incident depression: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175:631–48. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.17111194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith PJ, Merwin RM. The role of exercise in management of mental health disorders: an integrative review. Annu Rev Med. 2021;72:45–62. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-060619-022943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sadri I, Nikookheslat SD, Karimi P, Khani M, Nadimi S. Aerobic exercise training improves memory function through modulation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor and synaptic proteins in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex of type 2 diabetic rats. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2023;23:849–58. doi: 10.1007/s40200-023-01360-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Phillips C, Baktir MA, Srivatsan M, Salehi A. Neuroprotective effects of physical activity on the brain: a closer look at trophic factor signaling. Front Cell Neurosci. 2014;8:170. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2014.00170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pinar C, Yau SY, Sharp Z, Shamei A, Fontaine CJ, Meconi AL, Lottenberg CP, Christie BR. Effects of voluntary exercise on cell proliferation and neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus of adult FMR1 knockout mice. Brain Plast. 2018;4:185–95. doi: 10.3233/BPL-170052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Sousa RAL, Improta-Caria AC, Aras-Júnior R, De Oliveira EM, Soci RPR, Cassilhas RC. Physical exercise effects on the brain during COVID-19 pandemic: links between mental and cardiovascular health. Neurol Sci. 2021;42:1325–34. doi: 10.1007/s10072-021-05082-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stillman CM, Esteban-Cornejo I, Brown B, Bender CM, Erickson KI. Effects of exercise on brain and cognition across age groups and health states. Trends Neurosci. 2020;43:533–43. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2020.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Festa F, Medori S, Macrì M. Move your body, boost your brain: the positive impact of physical activity on cognition across all age groups. Biomedicines. 2023;11:1765. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines11061765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stubbs B, Rosenbaum S. Exercise based interventions for mental illness. London, United Kingdom, Academic Press; 2018. p.301-17. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller AH, Raison CL. The role of inflammation in depression: from evolutionary imperative to modern treatment target. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016;16:22–34. doi: 10.1038/nri.2015.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang Y, Yang Y, Li H, Feng Q, Ge W, Xu X. Investigating the potential mechanisms and therapeutic targets of inflammatory cytokines in post-stroke depression. Mol Neurobiol. 2024;61:132–47. doi: 10.1007/s12035-023-03563-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Serafini G, Amore M, Rihmer Z. The role of glutamate excitotoxicity and neuroinflammation in depression and suicidal behavior: focus on microglia cells. Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2015;2:127. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Starling S. Obesity affects skeletal muscle ketone oxidation. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2020;16:299. doi: 10.1038/s41574-020-0362-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eltokhi A, Sommer IE. A reciprocal link between gut microbiota, inflammation and depression: a place for probiotics? Front Neurosci. 2022;16:852506. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2022.852506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schuch FB, Vancampfort D, Richards J, Rosenbaum S, Ward PB, Stubbs B. Exercise as a treatment for depression: a meta-analysis adjusting for publication bias. J Psychiatr Res. 2016;77:42–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raichlen DA, Alexander GE. Adaptive capacity: an evolutionary neuroscience model linking exercise, cognition, and brain health. Trends Neurosci. 2017;40:408–21. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2017.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gordon BR, McDowell CP, Hallgren M, Meyer JD, Lyons M, Herring MP. Association of efficacy of resistance exercise training with depressive symptoms. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75:566–76. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.0572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cramer H, Lauche R, Anheyer D, Pilkington K, de Manincor M, Dobos G, Ward L. Yoga for anxiety: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Depress Anxiety. 2018;35:830–43. doi: 10.1002/da.22762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li SYH, Bressington D. The effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on depression, anxiety, and stress in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2019;28:635–56. doi: 10.1111/inm.12568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.De Sousa RA, Rocha-Dias I, De Oliveira LRS, Improta-Caria AC, Monteiro-Júnior RS, Cassilhas RC. Molecular mechanisms of physical exercise on depression in the elderly: a systematic review. Mol Biol Rep. 2021;48:3853–62. doi: 10.1007/s11033-021-06330-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.La Rocque CL, Mazurka R, Stuckless TJR, Pyke K, Harkness KL. Randomized controlled trial of Bikram yoga and aerobic exercise for depression in women: efficacy and stress-based mechanisms. J Affect Disord. 2021;280:457–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.10.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mandolesi L, Polverino A, Foti F, Ferraioli G, Sorrentino P, Sorrentino G. Effects of physical exercise on cognitive functioning and well-being: biological and psychological benefits. Front Psychol. 2018;9:509. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hiura LC, Donaldson ZR. Prairie vole pair bonding and plasticity of the social brain. Trends Neurosci. 2023;46:260–2. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2022.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Torelly GA, Bristot G, Schuch FB, Pio de Almeida Fleck M. Acute effects of mind-body practices and exercise in depressed inpatients: a randomized clinical trial. Ment Health Phys Act. 2022;23:100479. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stamatis A, Morgan GB, Boolani A, Papadakis Z. The positive association between grit and mental toughness, enhanced by a minimum of 75 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity, among US students. Psych. 2024;6:221–35. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schuch FB, Vancampfort D, Richards J, Rosenbaum S, Ward PB, Stubbs B. Exercise as a treatment for depression: a meta-analysis adjusting for publication bias. J Psychiatr Res. 2016;77:42–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Singh B, Olds T, Curtis R, Dumuid D, Virgara R, Watson A, Szeto K, O’Connor E, Ferguson T, Eglitis E, Miatke A, Simpson C E, Maher C. Effectiveness of physical activity interventions for improving depression, anxiety and distress: an overview of systematic reviews. Br J Sports Med. 2023;57:1203–9. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2022-106195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Muniandy ND, Kasim NAM, Abd Aziz LH. Association between physical activity level with depression, anxiety, and stress in dyslipidemia patients. Malays J Nurs. 2023;15:21–31. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cooney GM, Dwan K, Greig CA, Lawlor DA, Rimer J, Waugh FR, McMurdo M, Mead GE. Exercise for depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2013:CD004366. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004366.pub6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hejazi K, Wong A. Effects of exercise training on inflammatory and cardiometabolic health markers in overweight and obese adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2023;63:345–59. doi: 10.23736/S0022-4707.22.14103-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sharman MS, Chodick G, Gelerstein S, Barit Ben DN, Shalev V, Stein-Reisner O. Epidemiology of treatment resistant depression among major depressive disorder patients in Israel. BMC Psychiatry. 2022;22:541. doi: 10.1186/s12888-022-04184-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Silva LAD, Menguer LDS, Doyenart R, Boeira D, Milhomens YP, Dieke B, Volpato AM, Silveira PC. Effect of aquatic exercise on mental health, functional autonomy, and oxidative damages in diabetes elderly individuals. Int J Environ Health Res. 2022;32:2098–111. doi: 10.1080/09603123.2021.1943324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carek PJ, Laibstain SE, Carek SM. Exercise for the treatment of depression and anxiety. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2011;41:15–28. doi: 10.2190/PM.41.1.c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seshadri A, Wermers ML, Habermann TJ, Singh B. Long-term efficacy and tolerability of adjunctive aripiprazole for major depressive disorder: systematic review and meta-analysis. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2021;23:34898. doi: 10.4088/PCC.20r02799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vermote M, Deliens T, Deforche B, D’Hondt E. Determinants of caregiving grandparents’ physical activity and sedentary behavior: a qualitative study using focus group discussions. Eur Rev Aging Phys Act. 2023;20:20. doi: 10.1186/s11556-023-00330-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Praag H, Fleshner M, Schwartz MW, Mattson MP. Exercise, energy intake, glucose homeostasis, and the brain. J Neurosci. 2014;34:15139–49. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2814-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]