Abstract

Branching is a key structural parameter of polymers, which can have profound impacts on physicochemical properties. It has been demonstrated that branching is a modulating factor for mRNA delivery and transfection using delivery vehicles built from cationic polymers, but the influence of polymer branching on mRNA delivery remains relatively underexplored compared to other polymer features such as monomer composition, hydrophobicity, pKa, or the type of terminal group. In this study, we examined the impact of branching on the physicochemical properties of poly(amine-co-esters) (PACE) and their efficiency in mRNA transfection in vivo and in vitro under various conditions. PACE polymers were synthesized with various degrees of branching ranging from 0 to 0.66, and their transfection efficiency was systemically evaluated. We observed that branching improves the stability of polyplexes but reduces the pH buffering capacity. Therefore, the degree of branching (DB) must be optimized in a delivery route specific manner due to differences in challenges faced by polyplexes in different physiological compartments. Through a systematic analysis of physicochemical properties and mRNA transfection in vivo and in vitro, this study highlights the influence of polymer branching on nucleic acid delivery.

Keywords: Branched polymer, polyplex, poly(amino-co-ester), mRNA delivery, non-viral platform

1. Introduction

The development of non-viral RNA delivery platforms has gained significant attention, especially with the success of COVID-19 mRNA vaccines and clinical trials involving siRNA treatment.[1–3] Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) were used in two US FDA approved COVID vaccines,[4,5] and have become a standard method for mRNA delivery in pre-clinical research. On the other hand, polymer polyplexes, which are formed by electrostatic condensation between nucleic acids and cationic polymers, have emerged as alternate, potent non-viral transfection vectors. Polymer nanoparticles offer several advantages over lipid LNPs.[6,7] The chemical versatility of polymer synthesis allows for the optimization of polymer structure to enhance transfection efficiency, nanoparticle stability, biocompatibility, and even enables the incorporation of functional groups for advanced applications such as targeting and imaging.[8,9] Moreover, polymeric platforms can be mass-produced and formulated in a flexible manner.[10–13]

A variety of amine-containing cationic polymers, including derivatives of polyethyleneimine (PEI), poly(beta amino ester) (PBAE), and polyaspartamides have been developed for nucleic acid delivery. These polymers have been synthesized with various monomers and under conditions to control the composition, hydrophobicity, polymer length, biodegradability, and end-group chemistry.[14–17] The optimization of these factors through vehicle screening experiments has significantly improved the transfection efficiency of polymeric vehicles. These experiments have led to a better understanding of the effect of charge balances, nucleic acid binding affinity, pKa, and factors influencing endosomal escape.[18–20] We have focused on the development of a biodegradable non-viral polymeric platform, poly(amino-co-ester) (PACE).[21] Using enzymatic co-polymerization, we have been able to tune the hydrophobicity and biodegradability of PACE. Furthermore, the efficiency of mRNA transfection has been enhanced by incorporating end-group modifications,[18] co-polymerization of PACE with PEG, and controlled assembly of PEGylated polyplexes have improved in vivo transfection,[22] providing adaptability for various administration routes, including intravenous and intratracheal delivery.[18,23]

The branched structure has been shown to influence nucleic acid delivery in other polymer systems. Branched polymers possess a three-dimensional structure that can allow them to interact with nucleic acids and form stable polyplexes. For example, it has been observed that branched PEI improves the stability of polyplexes encapsulating DNA compared to linear PEI.[24,25] Similarly, branched PBAE has enabled higher protein expression after nebulized delivery of circular DNA and mRNA to the lungs, presumably due to improved NP stability.[26,27] Despite extensive research on the impact of polymer structure on nucleic acid delivery, the influence of branching specifically on mRNA delivery remains poorly understood.[28]

In particular, the delivery of mRNA to specific organs is done primarily based on the understanding and control of the physicochemical properties of delivery vectors.[28,29] For lung-specific delivery, local administration methods, such as inhalation and intrathecal administration, have garnered significant attention. These methods facilitate direct interactions of delivery vectors with lung epithelial cells and immune cells, while dramatically minimizing off-target effects compared to systemic administration. [23,30–32] To effectively deliver nucleic acids to the lung, which is rich in various lipids, surfactants, and proteins, along with polysaccharides that protect the mucous membrane, a delivery system capable of navigating these complex biological barriers is required.[33–35] Cationic polymer vectors are particularly promising due to their potential to maintain stable nanoparticles that withstand physical and chemical perturbations from nebulization energy and exposure to various lung surfactants. [22,23] Furthermore, the degree of polymer branching, as suggested in previous reports, may be a key factor in improving targeted mRNA delivery to the lung.[26]

In the lieu of the providing insight on the nucleic acid carrier development, in this article, we systematically studied the role of branching of PACE and their impacts on mRNA transfection under various physiological condition in vitro and in vivo. With a series of branched PACE (bPACE) having various degree of branching (DB), the intrinsic properties of branched PACE, including pKa, buffering capacity, and mRNA binding affinity, to polyplex stability, in vitro transfection, and in vivo transfection efficiency has been investigated, expecting to find a critical insight of the optimal branching in in nucleic acid delivery.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials and reagents

15-pentadecanolide (PDL), N-methyl diethanolamine (MDEA), sebacic acid (SA), diphenyl ether, Novozym 435 catalyst (Lipase acrylic resin, expressed in Aspergillus niger), bovine serum albumin (BSA), triethanolamine (TEOA), carbonyldiimidazole, and 1,3-diamino-2-propanol (DAP) were purchased from from MilliporeSigma (Saint Louis, MO, USA). CleanCap EGFP mRNA and CleanCap FLuc mRNA (5moU) were purchased from TriLink Biotechnologies (San Diego, CA, USA). For cell culture, A549 was purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA), DME/F-12 (1:1) media was purchased from GE Healthcare Life Science (Logan, UT, USA), fetal bovine serum (FBS) was purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA) and gentamicin was purchased from Gibco (Waltham, MA, USA). Pierce BCA Protein Assay were obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). Glo Lysis Buffer, and the Bright-Glo Luciferase Assay System were purchased from Promega (Madison, WI, USA). Precellys hard tissue lysing tubes were obtained from Bertin Instruments (Montigny-le-Bretonneux, France). Heparin, sodium salt (MilliporeSigma).

2.2. Synthesis of branched PACE (bPACE)

Branched PACE was synthesized by modifying the previously-reported PACE synthesis method.[18,21,23] The monomers (MDEA, SA, PDL, and TEA) and Novozym 435, an enzymatic catalyst, were transferred to a round-bottom flask and dissolved in diphenyl ether. The amount of precursors was determined as listed in Table S1, based on the targeted degree of branching. Prior to the reaction, the reactants were dissolved at 60 °C and degassed for 10 min. The monomers were oligomerized for 24 h at 90 °C under 1 atm argon, followed by subsequent condensation polymerization for 48 h at 90 °C under vacuum (1 mmHg). The purification of the synthesized polymers were carried out by precipitation with n-hexane, dissolution with dichloromethane and tetrahydrofuran, followed by the removal of residual solvents under vacuum. The polymers were characterized by 1H-NMR spectroscopy (Agilent, DD2 400 MHz) and gel permeation chromatography (Ultimate 3000 UHPLC system, Thermo Fisher Scientific).

2.3. End-group modification of bPACE

The terminal groups of bPACE were activated with carbonyldiimidazole (CDI) for end-group modifications with amine-containing functional groups. Fully dried bPACE was first dissolved in anhydrous DCM/THF (1:1 v/v, 67 mg/ml), to which 6-fold molar excess of CDI (relative to the terminal groups) was added as DCM-solubilized form (72 mg/ml). The reaction proceeded under argon with stirring over 24 hours. The residual CDI and side-products were removed and the activated polymers (bPACE-CDI) were collected by extraction using water and DCM. After removing water in organic layer with magnesium sulfate, bPACE-CDI was dried under vacuum overnight, and characterized with 1H-NMR and GPC. The amount of activated terminal groups was calculated based on the relative integration ratio of imidazole using 1H-NMR spectroscopy. Next, 8-fold excess amount of 1,3-diamino-2-propanol was dissolved in anhydrous DMSO and added to a pot of bPACE-CDI dissolved in anhydrous THF. The mixture was then vigorously stirred under argon. After 72 hours of reaction, the polymers were obtained by precipitation in water and dried overnight. The resulting polymers were dissolved in DMSO (100 mg/mL) for overnight at 37 °C in an orbital shaker.

2.4. Preparation and characterization of polyplex using PACE

mRNA was diluted with sodium acetate buffer (25 mM, pH 5.2) to a final concentration of 40 μg/mL, and polymers were also separately diluted with sodium acetate buffer aiming the target nucleic/polymer ratio at a final concentration of 1 (for 1:25) or 1.6 (for 1:40 w/w) mg/ml and vortexed for 10 s. The diluted polymer solution was transferred to the diluted nucleic acid solution, mixed with 30 s of vortex. The final concentration of mRNA in formulated polyplexes was 20 μg/ml. The polyplexes were incubated at room temperature for 10 min before use. Hydrodynamic Size and ζ-potential of the polyplexes were measured by dynamic light scattering (DLS, Zetasizer Pro, Malvern).

2.5. mRNA binding analysis

Binding of mRNA to polymer were analyzed with Quant-it™ RiboGreen RNA assay based on the manufacturer’s protocol. First, 30 μl of diluted mRNA (10 μg/ml) in sodium acetate buffer (25 mM, pH 5.2) and 30 μl of diluted polymer with various concentrations (1000, 500, 250, 125, 62.5, 31.3, 15.6, 7.81, 3.91, 1.95, 0.98, 0.49, and 0.24 μg/ml) were mixed and shaken in an orbital shaker at 900 rpm for 1 min, and incubated at room temperature for 10 min. Next, 10 μl of each formulated polyplexes was mixed with 190 μl of test solution (380-fold diluted RiboGreen® RNA reagent diluted in 200 mM Tris-HCl, 20 mM EDTA, pH 7.5). After 2 min, the fluorescence intensity (Ex/Em = 485/530) was measured using a plate reader. The amounts of mRNA bound to the polymers were calculated based on the relative fluorescence intensity emitted by the mRNA control.

2.6. pKa and buffer capacity measurement

To obtain titration curves, EasyPlus Titrator Easy pH (Mettler Toledo) was used. In a polypropylene beaker, 20 ml of sodium chloride (100 mM) and stirring bar were added. 1 mg of bPACE dissolved in DMSO (100 mg/ml) was then diluted with sodium chloride solution while stirring vigorously. For pH measurements, 5–6 μl of hydrochloric acid solution (1N) was added to the analyte to tune the pH to be between 3.7–4.0. The feed ratio of sodium hydroxide solution was set between 30–0.15 μl/min.

2.7. pKa measurement of polyplexes using TNS assay

Buffer solutions with varying pH values (4.0 to 10.0 at 0.5 increments) were prepared by adding hydrochloric acid solution (1N) or sodium hydroxide (1N) to the buffers containing sodium citrate (10 mM), sodium phosphate (10 mM), sodium borate (10 mM), or sodium chloride (150 mM). 2 mg/ml of TNS(2-(p-toluidino) naphthalene-6-sulfonic acid) stock solution dissolved in DMSO was prepared and diluted with each pH buffer solution by 100-fold. Next, 10 μl of the prepared polyplexes (0.5 mg/ml of polymer) and 100 μl of TNS analysis solution were added. After 5 min of incubation, fluorescent intensities were measured using a plate reader (SpectraMax, Ex/Em = 325/435 nm).

2.8. Heparin displacement assay

The prepared polyplexes were challenged with heparin to study their mRNA-complexation efficiency. The mRNA contents of the test groups were again analyzed using Quant-it™ RiboGreen RNA assay. First, 10 μl of polyplex formulated at 25:1 (polymer:mRNA; w/w) ratio was mixed with 100 μl of test solution (200-fold diluted RiboGreen® RNA reagent diluted in 200 mM Tris-HCl, 20 mM EDTA, pH 7.5 TE buffer), followed by addition of 40 μl TE buffer. Heparin solution was serially-diluted with TE buffer to yield mixtures with varying heparin-to-mRNA ratios between 0.2–200.0 (w/w). 50 μl heparin solution was added to each well right before fluorescence measurements (SpectraMax, Ex/Em = 325/435 nm). The fluorescence signals were measured every 30 s for 10 min.

2.9. In vitro expression and cytotoxicity

A549 cells were grown with DME/F12(1:1) media supplemented with 10% FBS, 50 μg/mL gentamicin at 37 ◦C, under 5% CO2. Prior to in vitro transfection experiments, A549 cells were plated in 24-well tissue culture plates at 50,000 cells per well or 96-well tissue culture plates at 12,500 cells per well and incubated for 24 h. The polyplexes dispersed in sodium acetate buffer were diluted in complete culture medium right before the treatment, to yield a final concentration of 1 μg/ml of EGFP mRNA. Either 500 μl (24-well plate) or 125 μl (96-well plate) of the respective polyplex formulations were treated to the cells. After 24 h of incubation, cells were washed once with PBS, dissociated with TrypLE, stained with LIVE/DEAD™ Fixable Near-IR or Zombie UV™ Fixable Viability Kit, resuspended in FACS buffer (2% BSA in PBS), and analyzed with flow cytometer (CytoFlex) for EGFP transfection efficiency. T

2.10. The cellular internalization and endosomal escape of bPACE polyplexes

The fluorescent polyplexes were prepared using the same method with Cy5-tagged EGFP mRNA at a 25:1 (w/w) polymer:mRNA ratio. To visualize the endosomal escape of mRNA delivered using PACE, we adapted a previously reported method [36]. A549 cells cultured on cover-slip bottomed dish were treated with polyplexes co-encapsulating Cy5-tagged EGFP mRNA and FITC-conjugated oligonucleotide. After 2 to 6 hours of incubation, the cells were washed multiple times and the nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342. Confocal microscopy was conducted using Zeiss LSM 880 (Carl Zeiss AG, Oberkochen, Baden-Württemberg, Germany).

2.11. In vivo expression

All animal procedures were performed in accordance with the guidelines and policies of the Yale Animal Resource Center (YARC) and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Yale University. Male BALB/c mice, 7–12 weeks of age, were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). The bPACE polyplexes were delivered either by intratracheal instillation (IT) or retro-orbital injection (IV). Polyplexes were prepared in sodium acetate buffer (25 mM, pH 5.2) to a final concentration of 2.5 mg/ml polymer and 0.1 mg/ml FLuc mRNA (IT delivery) or 1.25 mg/ml polymer and 0.05 mg/ml FLuc mRNA (IV delivery). For IT delivery, mice were anesthetized under 3% isoflurane and suspended by the incisors. 50 μL of each polyplex formulation was administered to the back of the mouth while the tongue was retracted with tweezers. The tongue was held in the retracted position for the duration of 10 breaths while polyplexes were inhaled. After 24 hour, RediJect D-Luciferin substrate (30 mg/ml in PBS) were administered to mice intraperitoneally at a dose of 150 mg/kg. IVIS luminescence imaging was carried out 15 minutes after luciferin administration. Mice were then euthanized, perfused with 20 mL heparin containing PBS (10 U/ml). Heart, lungs, spleen, liver, and kidneys were collected within 30 min after luciferin administration and imaged with IVIS. Lungs were collected from IT-delivered mice, transferred to 2-ml tissue homogenizing tubes (Precellys hard tissue lysing tubes) and mixed with 1 mL Glo Lysis Buffer. From IV-delivered mice, lungs, liver, spleen, and kidneys were collected. Organs were homogenized at 6500 rpm for 30 s twice, and subsequently centrifuged at 21,000 g for 10 min. 20 μl of the supernatant of the tissue lysate was mixed with 100 μl Bright-Glo luciferase substrate and luminescence was measured at an integration time of 10 s (Promega GloMax 20/20). The total protein concentration in the tissue lysates was measured by Pierce BCA protein assay, following the manufacturer’s protocol.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Synthesis of Branched PACE and mRNA polyplexes

Branched PACE was synthesized by enzymatic co-polymerization followed by end-group modifications based on a modified literature protocol (Fig. 1A).[18,21] [23] To understand the impact of branching, we synthesized linear PACE and five bPACEs with varying degrees of branching (DB). TEOA was added to the initial polymerization reaction to achieve a branched structure. TEOA is structurally similar to MDEA, the monomer used in linear PACE, in terms of the monomer aliphatic chain length and terminal alcohol groups, but TEOA is dendritic, containing three terminal hydroxyl groups capable of incorporating a branched backbone component to the polymer chain. The DB was controlled by modifying the feed ratio of TEOA to MDEA during polymer synthesis. The hydroxyl group to carboxylate ratio was maintained at 21:20 to minimize the risk of cyclization and gelation during the condensation reaction (Table S1 and S2). bPACEs were characterized with proton nuclear magnetic resonance (1H-NMR, Figs. S1 and S2) and gel permeation chromatography (GPC, Fig. S3). The final monomer ratios incorporated into bPACE and PACE corresponded well to the feed ratios and expected DB (Table S3).

Fig. 1.

Branched PACE and polyplexes. (A) Schematic illustration of PACE and branched PACE (bPACE), the consisting monomers, and formation of mRNA/bPACE polyplexes. (B) Degree of branching (DB) of bPACEs. (C) Monomer contents of bPACEs and PACEs. (D) Hydrodynamic size (z-average) and polydispersity index (PDI) E) Zeta-potential of polyplexes formulated with bPACE.

It is well known that the end-group chemistry of cationic polymers influences mRNA loading, cellular uptake, and endosomal escape, with terminal amine groups often added to enhance transfection efficiency.[18] We added 1,3-diamino-2-propanol (DAP), an end-group that has previously been studied for optimizing PACE polyplexes for inhalational delivery to the lungs,[23] to the carboxyl-terminal groups of bPACE using carbonyldiimidazole (CDI). Both imidazole and DAP modification were verified with 1H-NMR (Figs. S4, S5, and S6). These modifications did not affect the polymer DB. The DAP end-group content varied predictably based on the DB (Figs. 1B, C, and Table S4).

Since bPACEs with higher DB have more terminal groups, the impact of branched structures could be confounded by the higher terminal amine content of the end-group modified polymers. Therefore, we prepared an additional control group, short linear PACE (PACE-s) with lower molecular weight and therefore comparable ratios of terminal amine groups at a given concentration. PACE-s enabled the evaluation of the impact of branching on mRNA delivery to be deconvoluted from the effects of terminal amine content and length/molecular weight of the PACE. GPC traces confirmed that bPACEs were successfully synthesized to have molecular weights between PACE and PACE-s without evidence of gelation. We observed that the molar ratio of DAP in PACE-s was two-fold larger than PACE, and the DAP content of all bPACEs were between that of PACE and PACE-s. Finally, the ratio of tertiary amine groups decreased as DB increased, as expected (Table S5).

The binding of mRNA to bPACE was evaluated using a Ribogreen assay (Fig. S7). More than 90% of mRNA was encapsulated in bPACEs and PACE-s polyplexes at a 25:1 polymer to mRNA weight ratio; linear PACE exhibited lower mRNA binding at the same weight ratio (Fig. S7A). For weight ratios less than 25:1, the average binding efficiencies decreased for all groups. However, the binding curves of the mRNA loading based on the polymer to mRNA weight ratio overlapped, with no notable differences among groups (Fig. S7B and S8). bPACE polyplexes and PACE polyplexes formulated with a 25:1 polymer to mRNA weight ratio exhibited average hydrodynamic sizes less than 110 nm (Fig. 1D). The surface potentials of polyplexes were all positive (Fig. 1E). We observed that the zeta-potentials of PACE polyplexes decreased progressively with increasing branching degree. Notably, the most highly branched PACE (bPACE-5) exhibited the lowest zeta-potential, approximately 13 mV, among the tested polyplexes.

3.2. pKa evaluation of bPACE and polyplexes

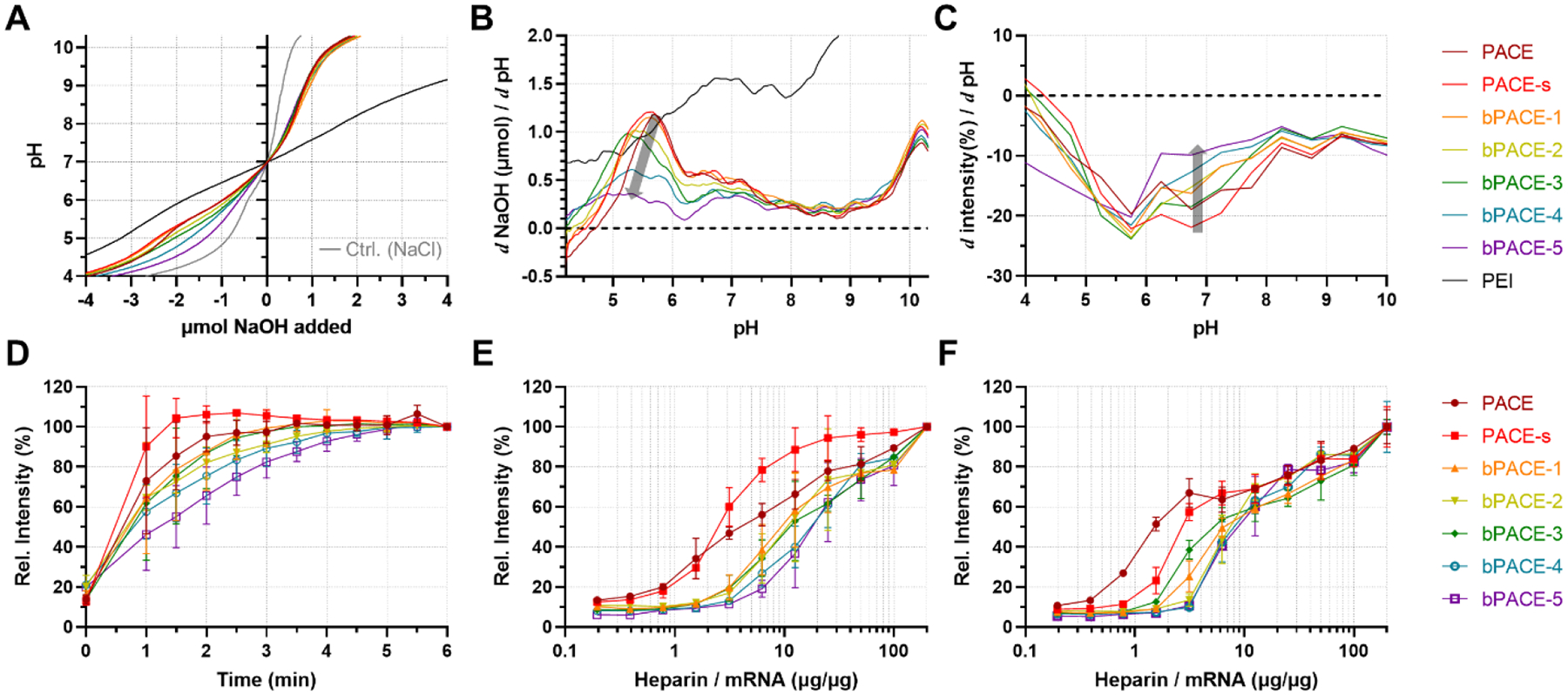

We analyzed the pH sensitivity, pKa of bPACE, and the release of mRNA from polyplexes to further investigate the physicochemical properties of bPACE (Fig. 2). pKa and buffering capacity in the range of slightly acidic to neutral pH are known to be key components for the protein sponge effect and endosomal escape of mRNA.[19,37,38] The acid-base titration curves of PACE polymers reveal that PACE exhibits a smaller buffering effect compared to the same of amount of bPEI, as expected based on the comparatively fewer amine groups in PACE by unit mass (Fig. 2A). However, significant differences in the buffering effects of bPACE were observed in the acidic pH range (pH < 7). bPACE with higher DB were closer to the NaCl control curves, which suggests that branching lowers the buffering capacity. The pKa of polymers is affected by the structures of amine groups and the adjacent protonated monomers, so we obtained the buffering capacity curve, which enabled detailed characterization of the buffering range of these cationic polymers. We calculated the buffering capacity based on the pH in solution by calculating the inverse slope of the titration curve or the inverse of the first derivative of the titration curve (dOH/dpH) (Fig. 2B).[19] All PACE polymers exhibited a bimodal distribution of buffering ranges (pH 5 to 6 and pH >10) and a clear trend was observed from the peak, which occurred between pH 5 to 6. The peaks demonstrate that the buffering capacity of PACE was reduced, and the effective pKa became slightly more acidic with increased DB. This reduction of buffering capacity was also observed from pH 6 to 7. The differences in buffering capacities can be attributed to the branched structure, resulting from the varied ratio of TEOA to MDEA. Differences in the titration curves of two linear PACEs (PACE and PACE-s) were insignificant, highlighting the importance of the effect of branching on polymer buffering capacity.

Fig. 2.

Physicochemical property of bPACE compared with PACE. (A) Acid-based titration curves of PACE, PACE-s, bPACE with various degrees of branching (bPACE-1,2,3,4,5), PEI and NaCl control (light gray). (B) Buffering curves calculated from the first derivative of acid-base titration curve. (C) Buffering curves calculated from buffering from TNS assay. (D) mRNA release quantified with Ribogreen assay after treating mRNA-bPACE polyplexes with heparin at 20:1 heparin to mRNA ratio (w/w), (E) Relative amount of released mRNA from polyplexes after 1 minute of various amounts of heparin added. (F) Relative amount of released mRNA from polyplexes after 10 minutes of various amounts of heparin added.

We also analyzed the pKa of polyplexes using the TNS (6-(p-Toluidino)-2-naphthalenesulfonyl chloride) assay, which has been used for measuring the pKa value for lipid NPs (Fig. S9). (ref) In contrast to acid-base titration of the lipid or polymer to determine pKa, the TNS assay allows us to evaluate the pKa of the formulated NPs. bPACE polyplexes formulated with 25:1 polymer to mRNA ratio were suspended in various pH buffers with TNS, and the fluorescent intensities were measured. A gradual reduction of fluorescent intensity was observed by increasing pH for bPACE polyplexes. This finding contrasts with the abrupt changes in fluorescent intensities observed with LNP formulations.[38] The calculated pKa of polyplexes from the TNS assay shows that the higher DB causes the pKa of polyplexes to decrease from 6.8 to 5.9. The slopes of the intensity change depending on pH (Δintensity/ΔpH, ΔpH = 1) were obtained to visualize the change in fluorescent intensities, similar to the buffering capacity curve in Fig. 2B, demonstrating that the buffering capacity near neutral pH (pH = 7) decreased as the DB increased (Fig. 2C).

3.3. Binding stability and release kinetics

To investigate the influence of branched structures on the binding stability of mRNA within polyplexes, we assessed mRNA release from polyplexes as a function of heparin sulfate concentration and incubation time (Fig. S10). Premature release of nucleic acid from polyplexes is one of the key challenges for in vivo transfection, and such release occurs via their molecular exchanges with various biomolecules, such as proteins, lipids, and polysaccharides. Heparin is a negatively charged polysaccharide that facilitates the dissociation of nucleic acid homogenously. Therefore, the heparin-induced release of mRNA can indirectly reflect the stability of polyplexes.

As depicted in Fig. 2D, our quantification of free mRNA increased with addition of heparin but plateaued within 5 minutes. The release profile indicates that mRNA is released more slowly from polyplexes formed with bPACE with a higher DB. Both linear PACEs (PACE and PACE-s) exhibited rapid release compared to bPACE, with PACE-s exhibiting the fastest release rate. This suggests that higher DB and larger molecule weight slows the dissociation between mRNA and PACE.

An increased ratio of heparin to mRNA leads to more total mRNA release for all polyplexes, confirming that the release of mRNA upon heparin addition is due to displacement and competitive binding (Figs. 2E and 2F). Both release profiles depending on the heparin/mRNA ratio showed that more heparin and more time is required to dissociate polyplexes formed with highly branched polymer. Although PACE-s has a similar concentration of terminal primary amine groups as highly branched PACE (bPACE-5), dissociation of mRNA from polyplexes requires less heparin. These observations are consistent with previous comparisons of linear PEI and branched PEI,[24] suggesting that the branched structure strengthens and stabilizes the complexation of nucleic acids and cationic polymer.

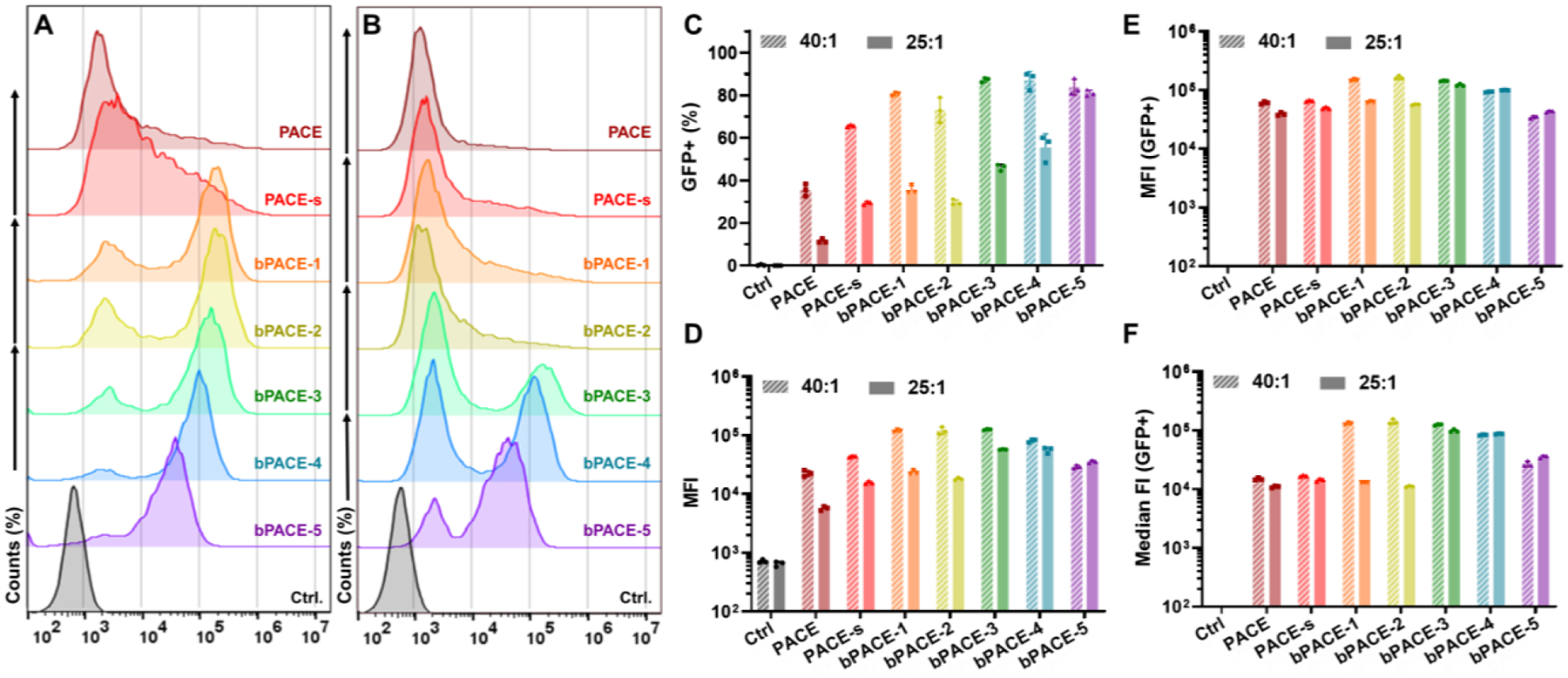

3.4. In vitro mRNA transfection, uptake, and cytotoxicity

To assess how DB affects bPACE polyplex transfection efficiency, we treated A549 cells with bPACE or linear PACE polyplexes loaded with EGFP mRNA at a 40:1 or 25:1 polymer to mRNA ratio (w/w) and analyzed cells by flow cytometry (Fig. 3 and Fig. S11). At a 40:1 ratio (polymer:mRNA), there were significant increases in mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) and percent of GFP positive cells for all bPACE polyplexes. PACE-s showed slightly higher transfection efficiency compared to linear PACE. For bPACE, polymers with higher DB (bPACE-3, 4, and 5) had improved transfection efficiency at the lower polymer:mRNA ratio of 25:1. Notably, while bPACE-5, which has the highest DB, did not induce the highest mean EGFP fluorescence intensity, as shown (Fig. 3A, B and D), it did transfect the highest percent of cells (Fig. 3A, B and C). This suggests that there is an optimal DB and charge balance for delivery of mRNA into the cytosol and their expression.

Fig. 3.

EGFP expression of A549 cells treated with EGFP-mRNA/bPACE polyplexes formulated with 40:1 and 25:1 of polymer:mRNA ratio, using flow cytometry. (A) Histogram of fluorescence intensity (EGFP) of A549 cells treated with 40:1 polymer/mRNA ratio. (B) Histogram of fluorescence intensity (EGFP) of A549 cells treated with 25:1 ratio. (C) Percentage of EGFP-expressing cells. (D) Mean fluorescence intensities (MFI) of EGFP from the total live cells. (E) MFI and (F) median fluorescence intensity of EFGP obtained from GFP-positive populations. (n=3, mean ± S.D.)

We also investigated whether the branched structure of the polymer affects cellular mRNA uptake by delivering Cy5-tagged mRNA (Fig. S12). Most cells took up a significant amount of Cy5-tagged mRNA. Although there were slight differences in the fluorescence intensity of the Cy5 signals, it is difficult to establish a correlation between the fluorescence of Cy5 and mRNA transfection (Fig. S12C–D). While previous reports suggest that cellular internalization is a key parameter for mRNA transfection [18], no such observation was made for bPACE.

To study the differences in endosomal escape between linear PACE and branched PACE, we prepared PACE and bPACE-1 polyplexes co-encapsulating FITC-tagged oligonucleotide and Cy5-tagged mRNA. These polyplexes were treated to A549 cells and imaged using confocal microscopy, adapted a previously reported method for assessing the endosomal escape mechanisms of nucleic acids. [36]

As shown in Fig. S13B, when genetic cargoes were delivered by themselves, only a few bright dot-shaped oligonucleotide signals were observed, indicating their poor internalization and that most nucleotides taken up remained in the endosomes. In contrast, both polyplexes significantly improved the cellular internalization of the cargoes. After 2 hours of incubation, the nucleotide and mRNA signals were mostly colocalized, suggesting they were in the form of nanoparticles and entrapped in the endosomes. Notably, some cells exhibited green fluorescence signals of oligonucleotides distributed in the cytosol for both linear and branched PACE groups after only 2 hours of incubation (Fig. S13B). After 6 hours of incubation, green signals in the cytosol and nuclei were evident, showing dramatically improved distribution compared to the control group. However, it was difficult to observe mRNA distribution in the cytosol compared to oligonucleotides, suggesting that the shorter oligonucleotides were more easily released from the polyplexes than the longer mRNA. This finding is consistent with previous reports using plasmid DNA. [36] No significant difference was observed between linear and branched PACEs at either timepoints.

The tolerability of PACE and bPACE polyplexes was assessed in vitro over a range of mRNA concentrations and compared to the commercially available Lipofectamine. The highest cell viability was observed with linear PACE, followed by PACE-s. Among all PACE polyplexes, the highly branched PACE (bPACE-5) exhibited the largest reduction in cellular viability, but all polyplexes induced less cellular toxicity than the Lipofectamine control (Fig. S14).

3.5. Polyplex colloidal and transfection stability

One of the challenges for translating mRNA therapeutics is their instability and short shelf life. mRNA is highly susceptible to degradation by ubiquitous RNase enzymes. Polyplexes, formed mainly with Coulombic interactions, often lose their colloidal stability and transfection efficiency when stored at higher temperatures or for longer times.[22,39] Because our measurements of polymer DB revealed a demonstrated effect on mRNA affinity and polyplex stability, we next assessed the colloidal stability and transfection efficiency after storage to evaluate the impact of polymer branching on stability.

First, we measured the hydrodynamic size, polydispersity index, and zeta potentials of bPACE and PACE polyplexes incubated at room temperature. Both linear PACEs (PACE and PACE-s) lost colloidal stability after 7 days, whereas highly branched PACE (bPACE-4 and −5) maintained their small size, PDI, and positive zeta potentials (Fig. S15).

Transfection efficiency after storage under various conditions was assessed with EGFP mRNA polyplexes. Polyplexes and Lipofectamine control (LipoMM) were incubated at 4 °C, 22 °C, or 37 °C for 0, 1, 2, 4, 7, and 14 days (Figs. 4A, 4B, and S13). A549 cells were treated with polyplexes after storage and cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. The transfection efficiency of all polyplexes was retained after storage at 4 °C for two weeks, with no change in percent EGFP-positive cells or mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) compared to pre-incubated polyplexes at day 0 (Fig. S16). However, lipofectamine lost all activity at day 7. When incubated at room temperature (22 °C), a decrease in the transfection efficiency of linear PACE polyplexes was observed (Fig. S16). The percent of EGFP-positive cells and MFI were affected after 3 days of storage and activity was lost by day 7 of storage. However, highly branched bPACE polyplexes maintained high transfection efficiency even at day 14. DB also had a clear stabilizing effect on polyplexes stored at 37 °C (Figs. 4A, B). Linear PACE, which has the lowest terminal amine content, had the most rapid decline in transfection efficiency over time, followed by PACE-s. Higher DB bPACE polyplexes consistently improved transfection efficiency with the best performance achieved using bPACE-4 and 5. At both warm temper atures (22 °C and 37 °C), the LipoMM group failed to transfect.

Fig. 4.

Stability of bPACE-polyplexes transfection activity. (A-B) Differential EGFP expressions in A549 cells treated with EGFP/polyplexes stored at 37 °C for different time-points. (A) Percentages of EGFP expressed A549 cells transfected with polyplexes or lipofectamine MessengerMax (LipoMM) and (B) mean fluorescence intensities. (C-D) Stability of EGFP/bPACE polyplexes in serum-containing media. (C) Mean fluorescence intensity of EGFP signals from EGFP/polyplex-treated A549 cells depending on the incubation time in serum-containing media. (D) Percentage of EGFP-positive A549 cells treated with EGFP polyplexes, which was incubated in serum-containing media. (Polyplexes were formulated with 1:25 mRNA to polymer ratio (w/w), n=3, mean ± S.D.)

We also evaluated the effect of branching on the polyplex stability in the presence of serum proteins. For most administration routes, nanomaterials are exposed to serum proteins and other physiologic barriers prior to reaching the target cells. For polyplexes, this exposure can lead to interactions with various biomolecules, which in turn may alter the transfection efficiency. Thus, we pre-incubated polyplexes in cellular medium containing fetal bovine serum and then treated A549 cells to determine whether biomolecules in medium would interfere with transfection efficiency (Figs. 4C and 4D). Pre-incubation of polyplex formed with linear PACE in medium led to a rapid drop in transfection efficiency over the first 4 hours. However, PACE-s and bPACEs exhibited slower drop in transfection efficiency until 4 hours of pre-incubation in media, which can be visualized in Fig. 4D. Highly branched bPACE (bPACE-4 and −5) maintained the transfection activity longer, showing significant expression even after 8 hours of pre-incubation in serum containing media.

3.6. In vivo transfection

Transfection efficiency was assessed in vivo through the delivery of polyplexes formulated with Fluc-mRNA and various PACEs. Polyplexes were administered to the lungs via intratracheal instillation (IT), a clinically relevant route for delivery of mRNA vaccines against respiratory pathogens and gene therapies for lung genetic disorders.[23,26,40,41] Additionally, we administered polyplexes systemically via intravenous injection (IV).

All mice treated IT with Fluc-mRNA polyplexes exhibited luminescent signal solely in the lungs (Figs. 5A, 5B and S17). Ex vivo luminescence imaging of organs confirmed that there was no luciferase expression outside the lungs, demonstrating that IT delivery achieves lung targeted mRNA transfection. The expression of luciferase was quantified and compared using tissue lysates from homogenized lungs after treatment. For linear PACEs, PACE-s, which contains a higher quantity of terminal groups, had superior luciferase expression compared to PACE. Significant increases (p < 0.05*) in luciferase expression were found after treatment with bPACE polyplexes. Among all the bPACE polymers, bPACE-1 and bPACE-3 exhibited equivalently high expression, as confirmed by in vivo imaging, ex vivo imaging, and tissue lysate luciferase analysis. In comparison to previous work with PACE polymers, which used a polymer to mRNA ratio of 100:1 (w/w),[22] [23] it was striking that the branched PACE significantly improved luciferase expression at lower polymer doses (25:1, w/w). However, transfection efficiency declined with DB of bPACE exceeding 0.5, implying that the DB must be optimized for maximum transfection activity.

Fig. 5.

FLuc mRNA was delivered using bPACE polyplexes by IT or IV administration, and Summarized effects of PACE branching. Representative IVIS images of luminescence in organs after (A) IT and (B) IV delivery. Luciferase expression in tissue quantified by luminescence assay for (C) IT delivery (lungs) and (D) IV delivery (lung, spleen, liver, kidney). (Polyplexes were formulated at the ratio of 1:25 (mRNA:polymer; w/w), n = 4, mean ± S.D., Statistical significance was accessed with One-Way ANOVA test, *p < 0.05, **p<0.01). (E) Heat map and diagram visualizing the effects of degree of branching. (aTitration: calculated buffer capacity obtained from acid-base titration (Fig. 2B, pH 5 to pH 6); bTNS assay: buffer capacity calculated from TNS assay intensity change (Fig. 2C, pH 6.5 to pH 7.5) cAssociation: mRNA-bPACE association strength evaluated from the dissociation half-life obtained from fig. 2D; dShelf-life: the day with 0% GFP+ in the extrapolated plot from Fig. 4B; e in vitro mRNA transfection from Fig.3D; fin vivo mRNA transfection from Fig. 5C. (The data in heat map were normalized to show clear trends, detail information on data collection and values were listed on Table S6–8.)

The branched structure of PACE also enhanced in vivo transfection when delivered IV (Figs. 5C, 5D and S18). Luminescent signal was primarily observed in the lungs, with some expression in the spleen. Luminescence was highest after delivery of bPACE-1 (DB = 0.1), surpassing both linear PACEs.

We further evaluated the in vivo tolerability of bPACE-polyplexes following IT administration. Seven days post-instillation, no noticeable inflammation was detected, and the structure of large airway and alveoli remained intact (Figs. S19 and S20). Complete blood count analysis revealed no systemic toxicities associated with a 25:1 polymer to mRNA ratio (w/w) for all PACE and bPACE polyplexes (Fig. S21). We monitored body weight changes in mice post-IT instillation of bPACE (Fig. S22). Despite a modest initial weight reduction, all groups recovered their original body weight within a week.

3.7. Discussion on the role of branching

Understanding the impact of cationic polymer structure on nucleic acid encapsulation and delivery is essential for the design of effective nucleic acid delivery platforms. In particular, structural changes that alter the biodistribution and in vivo expression of nucleic acids after systemic administration are not yet fully understood and controlling these aspects remains a significant challenge.

The complexation stability of polymers with mRNA is a critical factor influencing the in vivo delivery of nucleic acids.[39,42] Upon administration, polyplexes interact with numerous biomolecules present in physiological environment, which can disentangle and degrade the nucleic acid cargos before they are endocytosed by the target cells. Since mRNA need to be released intracellularly to achieve protein expression, an overly strong association of mRNA within the polyplexes can hinder the release of mRNA in cytosol. Therefore, a balance must be struck, whereby complexation is strong enough to protect extracellular polyplexes but cellular internalization and changes within the endosomal environment can decomplex and release mRNA into the cytosol.

Tuning the degree of polymer branching is promising strategy to improve nucleic acid delivery.[43] However, the role of branching structures on mRNA delivery has been challenging to elucidate because DB alters many physical and chemical parameters. In this work, we compared various branched PACE structures with differing degrees of branching. We systematically studied multiple aspects, such as the polymer’s physicochemical properties, the mRNA polyplex’s stability, in vitro transfection efficiency, and in vivo transfection efficiency.

Branching of cationic polymers provides multiple terminal sites on a single polymer. The terminal groups of bPACE were modified to contain primary amine and hydroxyl groups that can form hydrogen bonds with mRNA. This end-group modification provided stronger complexation between mRNA and branched polymers. The enhanced stability and delayed release of mRNA observed with branched polymers is attributable to the three-dimensional structure of branched polymers and the formation of multiple cross-linked hydrogen bonds between the polymer and nucleic acid chains.

The terminal group content can also be influenced by the molecular weight of the polymer. This effect was observed in a comparison between two linear derivatives, PACE and PACE-s, which differed in molecular weight by a factor of two. This difference primarily led to variations in the proportion of terminal groups (Fig. 1C), potentially increasing the polymer’s hydrophobicity.

We observed decreased stability in longer polyplexes with decreased proportion of terminal groups, which was similar to the trend seen with decreasing degree of branching (DB) (Fig. 4). This was most evident in the serum (Fig. 4D). However, longer PACEs showed relatively slower mRNA release rates compared to PACE-s (Fig. 2D), even with similar buffering capacities and ranges (Fig. 2A–C). It is hypothesized that the higher molecular weight contributes to lower diffusion and release rates through molecular exchanges. However, polymers with lower-than-threshold molecular weights are known to have low transfection efficiencies. However, previous studies using end-group-modified PBAE have shown that the optimal size of PBAE can be varied depending on the end-groups, in which the effect of molecular weight was not as significant. [17]

The comparison between PACE and bPACE-3, with relatively large molecular weights, showed that the transfection efficacy, polyplex stability, and in vivo transfection efficiency can be improved with branching. The comparison among PACE-s, bPACE-1, and bPACE-4 with relatively similar molecular weights shows similar effect of DB as well. Although we could not directly assess the impact of molecular weight within the same degree of branching in this study, comparing the bPACEs with two linear PACE polymers with different molecular weights and terminal amine contents clearly demonstrated the distinct impact of molecular weight. In addition, the role of branching were also able to be deconvoluted from the contents of terminal group and molecular weight by comparing with two linear counterpart. The improved stability of polyplexes derived from branched polymers was demonstrated in both storage and serum exposure experiments.

The highly branched structures were found to have notable limitations, including reduced pH buffering capacities and increased cytotoxicity. In this study, we controlled DB based on the feed ratio of tertiary amines. The reduced ratio of tertiary amine groups in highly branched PACEs (Table S5) may explain the observed phenomena regarding pH buffering and zeta-potentials. First of all, the lower ratio of tertiary amines in highly branched PACEs diminished their buffering capacity. In addition, the branching monomer, TEOA, with three alcohols on adjacent beta carbons, makes the tertiary amines less basic compared to MDEA, resulting in lower pKa values [44]. The relationship between DB and pH buffering ranges was able to observed from titration experiments (Figure 2A). The corresponding gradual reduction in surface zeta-potentials was also observed, which was attributed to fewer positively charged amines present around pH 5.2 due to the lower number of tertiary amines and more acidic pKa values. Collectively, polyplexes with highly branched PACE exhibited lower zeta-potential values.

The range of pKa and pH responsiveness between physiological and endosomal pH (between 5 to 8) are important for both lipid-based and polymeric gene vectors. Accordingly, poor pH buffer capacities of highly branched PACE contributed to their poor transfection efficiency. The intricate branched structure possibly interfere the cooperative behavior in pH responsiveness typically observed in linear polymeric nanoplatform, causing the lower transfection capability. [45]

Surface potential also plays a critical role in nucleic acid vectors. For instance, according to our previous report on optimizing PACE terminal functional groups, polyplexes exhibiting high mRNA expression were predominantly positively charged. [18,46] Conversely, negatively charged polyplexes showed poor mRNA expression efficiency. It is well established that positively charged nanoparticles more readily associate with cells, facilitating cellular internalization.[18] However, the expression level and zeta-potential values do not consistently correlate, as evidenced by previous studies on PBAE. [17,46] The low surface potential of bPACE-5 may have contributed to its reduced transfection efficiency. Nevertheless, considering the differences in mRNA expression levels of PACE and PACE-s, whose zeta-potential values were both significantly higher than the other derivatives, it is rationally hypothesized that other factors like terminal groups and degree of branching were more critical than the surface potential alone. Importantly, there was a correlation between zeta-potential and cellular internalization, indicating that higher positive charge tends to lead to higher cellular internalization (Fig. S23).

In addition to the end-group contents and type or ratio of tertiary amines, there are other physicochemical properties of bPACE that influence its mRNA transfection ability. The hydrophobicity is an important factor to consider, particularly because the lipid bilayer perturbation on a cell surface or endosome is critical for endosomal escape and cytosolic delivery of nucleic acids. In this study, the backbone structures of bPACE derivatives were composed of the same monomers, allowing their hydrophobicity and hydrophilicity to be mainly determined by the terminal groups. Furthermore, the primary amine and hydroxyl groups were located at the terminal groups of the polymers. Thus, we reasoned that a larger molecular weight with less branching would yield a more hydrophobic bPACE. It is well known that the optimization of terminal groups of a gene carrier improves its mRNA transfection efficacy both in vitro and in vivo. One strategy for controlling polyplex stability is optimizing the hydrophobicity of cationic polymers.[39] One proven method for modulating polymer hydrophobicity has been to graft repeating alkyl moieties onto cationic polymers.[47] It is possible that the differences in hydrophobicity between the derivatives of bPACE could influence their mRNA transfection efficacies. However, the terminal groups of bPACE have been shown to have a dominant effect on the transfection over hydrophobicity/hydrophilicity. [17,46] Previous studies on the linear form of PACE modified with various terminal groups showed that similar polarity between the end-groups did not lead to similar levels of transfection efficiency even with the identical backbone structure.[18] In addition, hydrophobic terminal groups showed relatively poor transfection efficiency compared to hydrophilic terminal groups.[48]

Our in vivo study focused on evaluating bPACE derivatives’ ability to delivery mRNA to the lung. For lung delivery, where inhalation is possible, the stability of polyplex is particularly important. The inhaled nanoparticles must overcome the strong shear stress of nebulization, maintain stability, and avoid aggregation. It has been reported that polymer-based nanocarriers are better than lipid-based carriers in maintaining their colloidal stability and transfection performance after nebulization.[35] Additionally, it has been reported that branching provides improved stability to the polyplexes. [26]

For lung- and bronchus-targeted delivery of mRNA, it is important to deliver the cargo to the epithelium without being entrapped in the mucosal layer. In this respect, colloidal stability is crucial for preventing the aggregation of nanocarriers – PEGylation has been employed to enhance the mucosal penetration and transfection efficiency of nanocarriers.[22,23] However, as excessive PEGylation can also interfere with the transfection process, and the PEGylation ratio needs to be optimized.[33] To ensure the mRNA cargo survives in the complex in vivo environment and harsh nebulizing conditions, it is necessary to understand and control the weak interactions in nanocarriers.[40] Branching has shown promise in regulating these interactions.

For application as an inhalation-based vaccine, it is necessary to secure adaptive immunity with minimal inflammatory responses.[32] Coatings that increase delivery efficiency to the target cells may be needed depending on the disease models.[49] A highly effective carrier with low toxicity is also essential. Further research on toxicity control and cell-selective mRNA delivery is warranted, with a particular focus on investigating additional factors that influence branching.

The observations suggest that the mechanism of release of nucleic acids through temporary binding between the carrier and substrate plays an important role in the efficiency of nucleic acid delivery. In particular, it has been shown that if the carrier provides too strong an interaction, it can disrupt the structural stability of cell membranes and intracellular membranes and cause conformational changes in proteins, leading to cytotoxicity. Therefore, as we have observed with this series of branched PACEs, it is important to ensure that the balance between protection and binding is not disrupted, thus optimizing the delivery capabilities of the system without causing cytotoxicity. We found that branching acts as another regulatory factor to modulate the physicochemical properties of the polymer, allowing us to maximize delivery efficiency through optimal delivery effects that cannot be achieved through molecular weight control of linear polymers (Fig. 5E, Table S6–S8). The physiological barriers and biochemical challenges that hinder successful mRNA delivery by nanoparticles are diverse, and our results also follows to show the optimal DB varies between in vitro and in vivo experiments. This suggests that the optimum DB should be carefully tailored to the administration route and the specific physiological environments encountered.

4. Conclusion

With the successful implementation of mRNA therapeutics in clinical medicine, nucleic acid therapeutics are gaining more attention. It’s becoming increasingly important to develop effective delivery platforms. To address the current challenges such as low bioavailability and the inefficient delivery of nucleic acid therapeutics, polymeric delivery vehicles may exploit modulation of polymer branching to improve performance. In particular, based on the understanding of the effect of the degree of branching, the optimal solution can be achieved by considering how to balance the binding of the carrier and nucleic acid. The great attention in branched structure were found not only in polymeric vehicle but also in lipid based platform as well.[50,51]

Polymer branching is a multifaceted factor that not only influences various properties of the polymer but also significantly impacts the physicochemical parameters of the polymer-formulated nanocarriers. In this work, we studied the impact of polymer branching in terms of the ratio of amine species and the number of terminal groups, with a primary focus on mRNA release and stability. The role of branching can vary depending on the polymer and its functional groups. Nonetheless, our study provides a comprehensive analysis on the branching-dependent physicochemical properties of polymer-formulated nanocarriers and their impact on mRNA transfection. The understanding of nucleic acid delivery platforms based on structural design and molecular tuning of delivery will provide insights for the polymeric and lipid-based nanoparticle systems, as well as macro-scale biologics delivery systems.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (U01 AI145965 and UG3 HL147352). We thank Yale Flow Cytometry for their assistance with FACS. The Core is supported in part by an NCI Cancer Center Support Grant # NIH P30 CA016359. This work was supported by INHA UNIVERSITY Research Grant. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Declaration of interests

W. Mark Saltzman reports financial support was provided by National Institutes of Health. W. Mark Saltzman reports a relationship with Biomaterials that includes: board membership. W. Mark Saltzman reports a relationship with Xanadu Bio that includes: board membership, consulting or advisory, and funding grants. W. Mark Saltzman reports a relationship with Stradefy Biosciences that includes: consulting or advisory and funding grants. W. Mark Saltzman reports a relationship with Johnson & Johnson that includes: consulting or advisory and funding grants. W. Mark Saltzman reports a relationship with Celanese Corporation that includes: consulting or advisory. W. Mark Saltzman reports a relationship with Cranius that includes: consulting or advisory. W. Mark Saltzman has patent pending to Yale University. Molly Grun has patent pending to Yale University. Kwangsoo Shin has patent pending to Yale University. Hee Won Sub has patent pending to Yale University. Alexandra Suberi has patent pending to Yale University. W. Mark Saltzman is on the Editorial Board of Biomaterials. If there are other authors, they declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of competing interest

K.S., H.W.S., A.S., M.G., and W.M.S. are inventors on patent applications describing the use of PACE polymers for mRNA delivery. W.M.S. is a co-founder of B3 Therapeutics and Xanadu Bio, and. W.M.S. is a consultant to Xanadu Bio, Stradefy Biosciences, Johnson & Johnson, Celanese, Cranius, and CMC Pharma. The other authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Data availability

The raw/processed data required to reproduce these findings cannot be shared at this time as the data also forms part of an ongoing study.

References

- [1].Kaczmarek JC, Kowalski PS, Anderson DG. Advances in the delivery of RNA therapeutics: from concept to clinical reality. Genome medicine 9 (2017) 1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Herrera VL, Colby AH, Ruiz-Opazo N, Coleman DG, Grinstaff MW. Nucleic acid nanomedicines in Phase II/III clinical trials: translation of nucleic acid therapies for reprogramming cells. Nanomedicine 13 (2018) 2083–2098. 10.2217/nnm-2018-0122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Paunovska K, Loughrey D, Dahlman JE. Drug delivery systems for RNA therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Genet 23 (2022) 265–280. 10.1038/s41576-021-00439-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Dagan N, Barda N, Kepten E, Miron O, Perchik S, Katz MA, Hernan MA, Lipsitch M, Reis B, Balicer RD. BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine in a Nationwide Mass Vaccination Setting. N. Engl. J. Med 384 (2021) 1412–1423. 10.1056/NEJMoa2101765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Baden LR, El Sahly HM, Essink B, Kotloff K, Frey S, Novak R, Diemert D, Spector SA, Rouphael N, Creech CB, McGettigan J, Khetan S, Segall N, Solis J, Brosz A, Fierro C, Schwartz H, Neuzil K, Corey L, Gilbert P, Janes H, Follmann D, Marovich M, Mascola J, Polakowski L, Ledgerwood J, Graham BS, Bennett H, Pajon R, Knightly C, Leav B, Deng W, Zhou H, Han S, Ivarsson M, Miller J, Zaks T, Group CS. Efficacy and Safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med 384 (2021) 403–416. 10.1056/NEJMoa2035389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Golan-Paz S, Frizzell H, Woodrow KA. Cross-Platform Comparison of Therapeutic Delivery from Multilamellar Lipid-Coated Polymer Nanoparticles. Macromol. Biosci 19 (2019) e1800362. 10.1002/mabi.201800362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Lachelt U, Wagner E. Nucleic Acid Therapeutics Using Polyplexes: A Journey of 50 Years (and Beyond). Chem. Rev 115 (2015) 11043–11078. 10.1021/cr5006793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Putnam D. Polymers for gene delivery across length scales. Nat. Mater 5 (2006) 439–451. 10.1038/nmat1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Zhou C, Reesink HL, Putnam DA. Selective and Tunable Galectin Binding of Glycopolymers Synthesized by a Generalizable Conjugation Method. Biomacromolecules 20 (2019) 3704–3712. 10.1021/acs.biomac.9b00759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Ekladious I, Colson YL, Grinstaff MW. Polymer-drug conjugate therapeutics: advances, insights and prospects. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 18 (2019) 273–294. 10.1038/s41573-018-0005-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Neshat SY, Chan CHR, Harris J, Zmily OM, Est-Witte S, Karlsson J, Shannon SR, Jain M, Doloff JC, Green JJ, Tzeng SY. Polymeric nanoparticle gel for intracellular mRNA delivery and immunological reprogramming of tumors. Biomaterials 300 (2023) 122185. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2023.122185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Woodrow KA, Cu Y, Booth CJ, Saucier-Sawyer JK, Wood MJ, Saltzman WM. Intravaginal gene silencing using biodegradable polymer nanoparticles densely loaded with small-interfering RNA. Nat. Mater 8 (2009) 526–533. 10.1038/nmat2444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Frizzell H, Woodrow KA. Biomaterial Approaches for Understanding and Overcoming Immunological Barriers to Effective Oral Vaccinations. Adv. Funct. Mater 30 (2020) 1907170. 10.1002/adfm.201907170. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Bishop CJ, Kozielski KL, Green JJ. Exploring the role of polymer structure on intracellular nucleic acid delivery via polymeric nanoparticles. J. Control. Release 219 (2015) 488–499. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.09.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Miyata K, Nishiyama N, Kataoka K. Rational design of smart supramolecular assemblies for gene delivery: chemical challenges in the creation of artificial viruses. Chem. Soc. Rev 41 (2012) 2562–2574. 10.1039/c1cs15258k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Putnam D. Design and development of effective siRNA delivery vehicles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 111 (2014) 3903–3904. 10.1073/pnas.1401746111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Eltoukhy AA, Siegwart DJ, Alabi CA, Rajan JS, Langer R, Anderson DG. Effect of molecular weight of amine end-modified poly(beta-amino ester)s on gene delivery efficiency and toxicity. Biomaterials 33 (2012) 3594–3603. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.01.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Jiang Y, Lu Q, Wang Y, Xu E, Ho A, Singh P, Wang Y, Jiang Z, Yang F, Tietjen GT, Cresswell P, Saltzman WM. Quantitating Endosomal Escape of a Library of Polymers for mRNA Delivery. Nano Lett. 20 (2020) 1117–1123. 10.1021/acs.nanolett.9b04426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Routkevitch D, Sudhakar D, Conge M, Varanasi M, Tzeng SY, Wilson DR, Green JJ. Efficiency of Cytosolic Delivery with Poly(beta-amino ester) Nanoparticles is Dependent on the Effective pK(a) of the Polymer. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng 6 (2020) 3411–3421. 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.0c00271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Uchida H, Itaka K, Nomoto T, Ishii T, Suma T, Ikegami M, Miyata K, Oba M, Nishiyama N, Kataoka K. Modulated protonation of side chain aminoethylene repeats in N-substituted polyaspartamides promotes mRNA transfection. J. Am. Chem. Soc 136 (2014) 12396–12405. 10.1021/ja506194z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Kauffman AC, Piotrowski-Daspit AS, Nakazawa KH, Jiang Y, Datye A, Saltzman WM. Tunability of Biodegradable Poly(amine-co-ester) Polymers for Customized Nucleic Acid Delivery and Other Biomedical Applications. Biomacromolecules 19 (2018) 3861–3873. 10.1016/0006-291x(91)90890-j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Grun MK, Suberi A, Shin K, Lee T, Gomerdinger V, Moscato ZM, Piotrowski-Daspit AS, Saltzman WM. PEGylation of poly(amine-co-ester) polyplexes for tunable gene delivery. Biomaterials 272 (2021) 120780. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2021.120780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Suberi A, Grun MK, Mao T, Israelow B, Reschke M, Grundler J, Akhtar L, Lee T, Shin K, Piotrowski-Daspit AS, Homer RJ, Iwasaki A, Suh H-W, Saltzman WM. Polymer nanoparticles deliver mRNA to the lung for mucosal vaccination. Sci. Transl. Med 15 (2023) eabq0603.https://doi.org/doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abq0603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Kwok A, Hart SL. Comparative structural and functional studies of nanoparticle formulations for DNA and siRNA delivery. Nanomedicine 7 (2011) 210–219. 10.1016/j.nano.2010.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Wightman L, Kircheis R, Rossler V, Carotta S, Ruzicka R, Kursa M, Wagner E. Different behavior of branched and linear polyethylenimine for gene delivery in vitro and in vivo. J. Gene Med 3 (2001) 362–372. 10.1002/jgm.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Patel AK, Kaczmarek JC, Bose S, Kauffman KJ, Mir F, Heartlein MW, DeRosa F, Langer R, Anderson DG. Inhaled Nanoformulated mRNA Polyplexes for Protein Production in Lung Epithelium. Adv. Mater 31 (2019) e1805116. 10.1002/adma.201805116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Liu S, Gao Y, Zhou D, Zeng M, Alshehri F, Newland B, Lyu J, O’Keeffe-Ahern J, Greiser U, Guo T, Zhang F, Wang W. Highly branched poly(beta-amino ester) delivery of minicircle DNA for transfection of neurodegenerative disease related cells. Nat. Commun 10 (2019) 3307. 10.1038/s41467-019-11190-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Huang P, Deng H, Zhou Y, Chen X. The roles of polymers in mRNA delivery. Matter 5 (2022) 1670–1699. 10.1016/j.matt.2022.03.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Loughrey D, Dahlman JE. Non-liver mRNA Delivery. Accounts of Chemical Research 55 (2022) 13–23. 10.1021/acs.accounts.1c00601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Qin M, Du G, Sun X. Recent Advances in the Noninvasive Delivery of mRNA. Accounts of Chemical Research 54 (2021) 4262–4271. 10.1021/acs.accounts.1c00493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Roh EH, Fromen CA, Sullivan MO. Inhalable mRNA vaccines for respiratory diseases: a roadmap. Curr Opin Biotechnol 74 (2022) 104–109. 10.1016/j.copbio.2021.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Abdellatif AAH, Tawfeek HM, Abdelfattah A, El-Saber Batiha G, Hetta HF. Recent updates in COVID-19 with emphasis on inhalation therapeutics: Nanostructured and targeting systems. Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology 63 (2021) 102435.https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jddst.2021.102435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Ongun M, Lokras AG, Baghel S, Shi Z, Schmidt ST, Franzyk H, Rades T, Sebastiani F, Thakur A, Foged C. Lipid nanoparticles for local delivery of mRNA to the respiratory tract: Effect of PEG-lipid content and administration route. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics 198 (2024) 114266.https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ejpb.2024.114266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Raesch SS, Tenzer S, Storck W, Rurainski A, Selzer D, Ruge CA, Perez-Gil J, Schaefer UF, Lehr C-M. Proteomic and Lipidomic Analysis of Nanoparticle Corona upon Contact with Lung Surfactant Reveals Differences in Protein, but Not Lipid Composition. ACS Nano 9 (2015) 11872–11885. 10.1021/acsnano.5b04215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Jiang AY, Witten J, Raji IO, Eweje F, MacIsaac C, Meng S, Oladimeji FA, Hu Y, Manan RS, Langer R, Anderson DG. Combinatorial development of nebulized mRNA delivery formulations for the lungs. Nature Nanotechnology 19 (2024) 364–375. 10.1038/s41565-023-01548-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Rehman Z.u., Hoekstra D, Zuhorn IS. Mechanism of Polyplex- and Lipoplex-Mediated Delivery of Nucleic Acids: Real-Time Visualization of Transient Membrane Destabilization without Endosomal Lysis. ACS Nano 7 (2013) 3767–3777. 10.1021/nn3049494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Du L, Wang C, Meng L, Cheng Q, Zhou J, Wang X, Zhao D, Zhang J, Deng L, Liang Z, Dong A, Cao H. The study of relationships between pKa value and siRNA delivery efficiency based on tri-block copolymers. Biomaterials 176 (2018) 84–93. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.05.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Patel P, Ibrahim NM, Cheng K. The Importance of Apparent pKa in the Development of Nanoparticles Encapsulating siRNA and mRNA. Trends Pharmacol. Sci 42 (2021) 448460. 10.1016/j.tips.2021.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Wang Y, Ye M, Xie R, Gong S. Enhancing the In Vitro and In Vivo Stabilities of Polymeric Nucleic Acid Delivery Nanosystems. Bioconjug. Chem 30 (2019) 325–337. 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.8b00749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Lokugamage MP, Vanover D, Beyersdorf J, Hatit MZC, Rotolo L, Echeverri ES, Peck HE, Ni H, Yoon JK, Kim Y, Santangelo PJ, Dahlman JE. Optimization of lipid nanoparticles for the delivery of nebulized therapeutic mRNA to the lungs. Nat. Biomed. Eng 5 (2021) 1059–1068. 10.1038/s41551-021-00786-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Kim J, Jozic A, Lin Y, Eygeris Y, Bloom E, Tan X, Acosta C, MacDonald KD, Welsher KD, Sahay G. Engineering Lipid Nanoparticles for Enhanced Intracellular Delivery of mRNA through Inhalation. ACS Nano 16 (2022) 14792–14806. 10.1021/acsnano.2c05647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Grigsby CL, Leong KW. Balancing protection and release of DNA: tools to address a bottleneck of non-viral gene delivery. J. R. Soc. Interface 7 (2010) S67–82. 10.1098/rsif.2009.0260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Zhou D, Cutlar L, Gao Y, Wang W, O’Keeffe-Ahern J, McMahon S, Duarte B, Larcher F, Rodriguez BJ, Greiser U, Wang W. The transition from linear to highly branched poly(beta-amino ester)s: Branching matters for gene delivery. Sci. Adv 2 (2016) e1600102. 10.1126/sciadv.1600102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Perinu C, Bernhardsen IM, Svendsen HF, Jens K-J. CO2 Capture by Aqueous 3-(Methylamino)propylamine in Blend with Tertiary Amines: An NMR Analysis. Energy Procedia 114 (2017) 1949–1955.https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.egypro.2017.03.1326. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Li Y, Wang Y, Huang G, Gao J. Cooperativity Principles in Self-Assembled Nanomedicine. Chem. Rev 118 (2018) 5359–5391. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Sunshine J, Green JJ, Mahon KP, Yang F, Eltoukhy AA, Nguyen DN, Langer R, Anderson DG. Small-Molecule End-Groups of Linear Polymer Determine Cell-type Gene-Delivery Efficacy. Advanced Materials 21 (2009) 4947–4951. 10.1002/adma.200901718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Kim HJ, Ogura S, Otabe T, Kamegawa R, Sato M, Kataoka K, Miyata K. Fine-Tuning of Hydrophobicity in Amphiphilic Polyaspartamide Derivatives for Rapid and Transient Expression of Messenger RNA Directed Toward Genome Engineering in Brain. ACS Cent. Sci 5 (2019) 1866–1875. 10.1021/acscentsci.9b00843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Jiang Y, Gaudin A, Zhang J, Agarwal T, Song E, Kauffman AC, Tietjen GT, Wang Y, Jiang Z, Cheng CJ, Saltzman WM. A “top-down” approach to actuate poly(amine-co-ester) terpolymers for potent and safe mRNA delivery. Biomaterials (2018). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.05.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Tang Z, You X, Xiao Y, Chen W, Li Y, Huang X, Liu H, Xiao F, Liu C, Koo S, Kong N, Tao W. Inhaled mRNA nanoparticles dual-targeting cancer cells and macrophages in the lung for effective transfection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 120 (2023) e2304966120. 10.1073/pnas.2304966120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Hashiba K, Sato Y, Taguchi M, Sakamoto S, Otsu A, Maeda Y, Shishido T, Murakawa M, Okazaki A, Harashima H. Branching Ionizable Lipids Can Enhance the Stability, Fusogenicity, and Functional Delivery of mRNA. Small Science 3 (2023) 2200071.https://doi.org/ 10.1002/smsc.202200071. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Hajj KA, Ball RL, Deluty SB, Singh SR, Strelkova D, Knapp CM, Whitehead KA. Branched-Tail Lipid Nanoparticles Potently Deliver mRNA In Vivo due to Enhanced Ionization at Endosomal pH. Small 15 (2019) 1805097.https://doi.org/ 10.1002/smll.201805097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The raw/processed data required to reproduce these findings cannot be shared at this time as the data also forms part of an ongoing study.