Abstract

Introduction

Gout is one of the most common forms of arthritis worldwide. Gout is particularly prevalent in Aotearoa/New Zealand and is estimated to affect 13.1% of Māori men, 22.9% of Pacific men and 7.4% of New Zealand European men. Effective long-term treatment requires lowering serum urate to <0.36 mmol/L. Allopurinol is the most commonly used urate-lowering medication worldwide. Despite its efficacy and safety, the allopurinol dose escalation treat-to-target serum urate strategy is difficult to implement and there are important inequities in allopurinol prescribing in Aotearoa. The escalation strategy is labour intensive, time consuming and costly for people with gout and the healthcare system. An easy and effective way to dose-escalate allopurinol is required, especially as gout disproportionately affects working-age Māori men and Pacific men, who frequently do not receive optimal care.

Methods and analysis

: A 12-month non-inferiority randomised controlled trial in people with gout who have a serum urate ≥ 0.36 mmol/l will be undertaken. 380 participants recruited from primary and secondary care will be randomised to one of the two allopurinol dosing strategies: intensive nurse-led treat-to-target serum urate dosing (intensive treat-to-target) or protocol-driven dose escalation based on dose predicted by an allopurinol dosing model (Easy-Allo). The primary endpoint will be the proportion of participants who achieve target serum urate (<0.36 mmol/L) at 12 months.

Ethics and dissemination

The New Zealand Northern B Health and Disability Ethics Committee approved the study (2022 FULL 13478). Results will be disseminated in peer-reviewed journals and to participants.

Trial registration number

ACTRN12622001279718p.

Keywords: Clinical Trial, RHEUMATOLOGY, Clinical trials

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

This study uses the most commonly used urate-lowering therapy worldwide, namely, allopurinol.

This study has been designed to examine which strategy is most effective for Māori and Pasific participants.

The study is not blinded but the primary endpoint is serum urate which is not subject to bias.

Introduction

Background and rationale

Gout is the most common form of inflammatory arthritis worldwide, and its incidence appears to be increasing. Gout is particularly prevalent in Aotearoa/New Zealand. In 2019, 13.1% of Māori men, 22.9% of Pacific men and 7.4% of New Zealand European men and 4.3% of Māori women, 7.0% of Pacific women and 2.1% of New Zealand European women were estimated to be affected by gout.1 The primary biochemical abnormality in gout is an elevation in serum urate (hyperuricaemia). When supersaturation is reached, monosodium urate (MSU) crystals are formed and can deposit in joints and surrounding tissues. These MSU crystals trigger painful attacks of inflammatory arthritis within joints (gout flares). Inadequately treated gout leads to recurrent flares, formation of tophi (accumulation of MSU crystals in joints and soft tissues) and joint damage. Significant time off work, poor health-related quality of life and disability are common, also impacting families and friends.

Long-term urate-lowering therapy is key to the successful management of gout. Current international guidelines recommend the reduction of serum urate to <0.36 mmol/L for all people with gout.2 3 The basis for this recommendation is evidence that sustained reductions in urate below this target will lead to cessation of gout flares, regression of tophi and prevention of joint damage.

Allopurinol is the first-line urate-lowering therapy recommended by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR)3 and the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR).2 It is inexpensive (<5 NZ cents/day for 300 mg tablets) and typically taken once daily. Both nationally and internationally, allopurinol accounts for more than 90% of all urate-lowering therapy.4 Allopurinol has a key role in gout management in Aotearoa/New Zealand where funding for newer, more expensive therapies is not currently available or is restricted to those experiencing allopurinol failure. However, there are important inequities in allopurinol use, with non-Māori, and non-Pacific peoples more likely to receive regular allopurinol prescriptions than Māori or Pacific peoples.1

Recent data from a community-based randomised controlled trial (RCT) in the UK comparing general practitioner care and intensive nurse-led care showed that nurse-led care resulted in significantly greater long-term adherence to allopurinol. Furthermore, more people achieved target serum urate (30% vs 95%, respectively) and had fewer gout flares (mean (SD) flares 0.94 (2.03) vs 0.33 (0.93)) at 2 years in the intensive nurse-led arm.5 On the basis of this, intensive nurse-led care is currently considered best practice. However, while such community-based interventions have reported improvements in the clinical trial setting, real-life clinical studies in primary healthcare settings have not been as successful. For example, a study examining the effects of a gout package of care delivered in a rural Aotearoa/New Zealand general practice showed significantly more serum urate testing, but allopurinol dose escalation failed to occur for many despite being above target urate.6 Thus, more effective and easier ways to optimise the use of allopurinol are required.

Current recommendations advocate for gradual dose escalation of allopurinol to achieve target urate to minimise the risk of the rare but potentially life-threatening allopurinol hypersensitivity syndrome (AHS).3 7 This dose escalation treat-to-target serum urate strategy with allopurinol has been criticised as difficult to implement8 9 for several reasons. First, there is a wide dose range for allopurinol (50–900 mg daily) with no one fixed dose, allowing target urate to be achieved in the majority. This was highlighted in our recent allopurinol dose escalation study, in which the mean (range) allopurinol dose in those who achieved target urate was 400 (100–900) mg/day.10 11 Second, the allopurinol dose escalation strategy is labour intensive, costly and time consuming for health providers and those with gout. It requires monthly blood tests for serum urate with any dose changes based on the result. This requires the person with gout to attend for the blood tests, the result to be reviewed and the appropriate allopurinol dose communicated back to the patient. Achieving target urate can take months of intensive medical input and time for the patient. Finally, the majority of gout is managed in primary care where such intensive intervention is challenging, resulting in many people not receiving optimal care.

Individualised allopurinol dosing models that accurately predict allopurinol dose could result in a more streamlined and cost-effective dose escalation strategy without the requirement for monthly blood tests. This is particularly relevant for Aotearoa/New Zealand, where barriers within the healthcare system (including inconvenience, cost of treatment, time off work) disproportionately affect working-age Māori men and Pacific men with gout, which contribute to inequitable outcomes.12 This clinical trial tests an easier patient-led strategy for introducing allopurinol, which primarily aims to reduce the burden of healthcare visits for patients and, by default, benefits the health system.

A number of variables that influence the dose of allopurinol required to achieve target urate have been identified. We have developed an allopurinol dosing model in the Aotearoa/New Zealand gout population13 14 and further refined this model to predict the dose of allopurinol required to reach target urate using the following readily available clinical variables: weight, baseline urate, renal function and ethnicity. This model has been developed to accurately predict the allopurinol dose required to achieve serum urate target (<0.36 mmol/L) in >80% of people with estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR)>30 mL/min/1.73 m2.15 Of note, in our previous allopurinol clinical trial, which employed the intensive treat-to-target approach, 80% achieved target urate.11 The doses predicted by the dosing model range from 200 to 700 mg daily.

Hypothesis

We hypothesise that a protocol-driven dose escalation strategy based on a predicted dose from the allopurinol dosing model (Easy-Allo) is non-inferior to the current best practice nurse-led intensive treat-to-target strategy in people with gout for achieving target urate. In addition, we hypothesise that the Easy-Allo strategy is more cost-effective and acceptable to people with gout.

Aims

The aim of the RCT is to determine whether a protocol-driven dose escalation strategy based on a predicted dose from the allopurinol dosing model (Easy-Allo strategy) is non-inferior to the current best practice nurse-led intensive treat-to-target strategy in people with gout. A preplanned 2-year extension study will determine the long-term effects of each intervention strategy on persistence with allopurinol therapy and gout flare rates. Additional key secondary outcome studies and substudies include analysis of equity, cost-effectiveness and health psychology approaches to predict medication adherence, patient experience, gout remission and gout inflammatory biomarkers.

Methods and analysis

Trial design and overview

A 12-month open-label non-inferiority RCT of people with gout will be undertaken with a 2-year extension phase. The trial will recruit 380 people with gout and serum urate≥0.36 mmol/L (6 mg/dL) already receiving allopurinol at a dose below that predicted to achieve target serum urate, not taking allopurinol regularly or needing to commence allopurinol. Participants will be randomised to one of the two allopurinol dosing strategies: nurse-led intensive treat-to-target serum urate dosing (intensive treat-to-target) or protocol-driven dose escalation based on a predicted dose (Easy-Allo). For those in the Easy-Allo arm, the dose predicted to achieve target serum urate will be determined from the allopurinol dosing model. Recruitment commenced on 1 February 2023 and is anticipated to be completed by 31 January 2027.

Participant selection and recruitment

Participants will be recruited from primary and secondary care in Auckland and Christchurch, Aotearoa/New Zealand. Potential participants will be identified from rheumatology clinics and inpatient databases, through searches of general practice databases and public advertising. Recruitment will be purposeful to focus on those who receive less continuous allopurinol in Aotearoa/New Zealand, that is, younger participants, Māori participants, Pacific participants and men. We aim to recruit 1/3 Māori, 1/3 Pacific and 1/3 non-Māori/non-Pacific peoples.

Inclusion criteria

Participants must be ≥18 years of age, fulfil the ACR/EULAR 2015 Gout Classification criteria,16 have serum urate≥0.36 mmol/L (6 mg/dL) at screening and either (1) not already taking allopurinol, but starting urate-lowering therapy strongly recommended in the 2020 ACR gout management guidelines (ie, any of the following: ≥2 gout flares/year, ≥1 subcutaneous tophi, radiographic damage due to gout) or (2) already taking allopurinol for gout at lower than predicted dose or (3) already taking allopurinol but not regularly. In addition, participants must be agreeable to starting or continuing allopurinol, giving informed consent and communicating via telephone.

Exclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria include the following: severe kidney disease with eGFR<30 mL/min/1.73 m2, contraindication or previous intolerance to allopurinol, concomitant azathioprine, due to interactions with allopurinol, HLA-B*5801 positive, due to high risk of AHS, and unstable comorbid health conditions (eg, NYHA stage 4 heart failure, recent (within 6 months) myocardial infarction, advanced cancer, dementia, females of childbearing age not on contraception and the concurrent use of febuxostat and allopurinol at the time of screening).

Intervention

Potential participants will attend a screening visit in person or by phone, where informed consent will be obtained by the study nurses (see online supplemental material for informed consent documents). Allopurinol drug information will be provided as part of the consent process. They will be seen by a study doctor at this screening visit (if not already seen) and eligibility will be determined. The baseline study visit will occur within 4 weeks of the screening visit. For individuals at high risk of allopurinol hypersensitivity (those of Asian or African descent), an HLA-B*5801 test will be requested at screening.

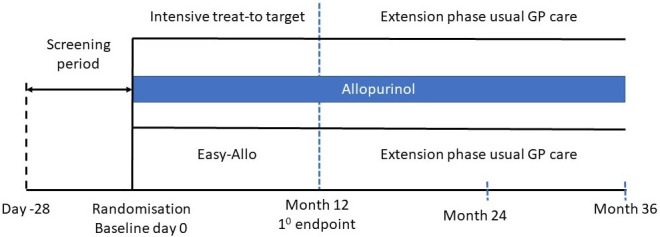

At the baseline visit, participants will be randomised on a 1:1 ratio to the intensive nurse-led treat-to-target strategy or the Easy-Allo strategy (figure 1). The randomisation list will be generated by the independent study statistician using a computer-generated list. Randomisation will be stratified according to ethnicity (Māori, Pacific peoples, non-Māori/non-Pacific peoples) and by those starting or continuing allopurinol and will be arranged in permuted blocks. Randomisation will occur at the baseline visit.

Figure 1. Study design.

Allocation will be concealed in an opaque sealed envelope which will only be opened once the participant has consented.

All participants will receive a standardised gout information package at the baseline visit based on patient-focused resources developed in Aotearoa/New Zealand for New Zealanders (available in Te Reo Māori, Sāmoan, Tongan, Niuean, Cook Island Māori and English). These resources were developed incorporating four principles identified by Sir Masson Durie that underlie learning at the interface of indigenous knowledge and science: (1) mutual respect, (2) shared benefits, (3) human dignity and (4) discovery (Durie M Ngā Tini Whetū: Navigating Māori Futures Wellington: Huia; 2011).

This information package covers the causes of gout, the role of urate and genes, dietary issues as well as standard approaches to lowering urate and treating gout flares. The package uses the patient-centred adult learning process developed in Aotearoa/New Zealand known as the ABC model: (1) Ask about what participants know about gout and its management and their beliefs about the disease, (2) Build on their knowledge and understanding and (3) Check you have been clear. This process will be further used if required at subsequent study visits to enhance participant knowledge of gout.

For those participants not already receiving allopurinol, it will be commenced at the baseline visit. Starting dose will be 50 mg daily in those with eGFR<60 mL/min/1.73 m2 and 100 mg daily in those with eGFR≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2. For all participants, the allopurinol dose will be increased monthly by 50 or 100 mg per day as determined by eGFR to a maximum of 900 mg daily in the nurse-led arm or to the predicted dose in the Easy-Allo arm. Allopurinol will be continued indefinitely unless adverse effects such as rash, AHS or other adverse effects the participant cannot tolerate require its discontinuation. All medication doses and assessment notes will be sent to the participant’s general practitioner at the end of each study visit to ensure full communication between healthcare providers.

In addition to the medical review at the screening visit, all participants will be seen by a study doctor during the study on an as required basis. Participants will be reviewed at the final study visit at month 12 by the study doctor to ensure appropriate handover of care to the general practitioner.

All participants will be offered anti-inflammatory prophylaxis throughout the first 3–6 months of the study period with either low dose colchicine, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) or prednisone consistent with current management guidelines.2 17 While the participant and investigator will agree on the medication and dose at the screening visit, our rank order will be colchicine>NSAID>prednisone. In addition, all participants will be provided with a ‘rescue’ gout flare plan to commence appropriate treatment with either colchicine, NSAID or prednisone should they develop a gout flare. Again, the participant and investigator will agree on the exact medication and dose at screening.

Intensive treat-to-target arm

Allopurinol dose escalation will be based on the monthly serum urate level and phone contact with the study co-ordinator. The dose will be increased until serum urate has been <0.36 mmol/L for three consecutive visits. Prescriptions will be provided as required during the 12-month study period. All participants will be seen by the study co-ordinator at months 3, 6, 9 and 12 and will have three monthly safety blood tests, including full blood count, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and creatinine.

Easy-Allo arm

For participants in the Easy-Allo arm, the predicted dose of allopurinol will be based on the model-derived dosing guideline. Following the standardised gout education package, the participants will receive a written plan and allopurinol prescriptions at baseline and every 3 months. The participants will be instructed to increase the allopurinol monthly until the predicted dose has been reached. The participants will be given the contact details of the study co-ordinator in case they have questions or problems they wish to discuss and will be seen in person on an as-required basis. Thus, the dose escalation is largely self-driven by the participants in this arm. All participants will be seen by the study co-ordinator at months 3, 6, 9 and 12 and will have three monthly safety blood tests, that is, full blood count, ALT and creatinine, consistent with what is recommended for patients starting allopurinol in primary care. They will have a serum urate measurement at months 3, 6, 9 and 12 but will not have changes in allopurinol dose after they have reached the predicted dose.

Extension study

A preplanned 2-year extension study will determine the long-term effects of each intervention strategy on allopurinol persistence and gout flare rates. At month 12, participants will be discharged to their general practitioner for ongoing gout management. A handover letter will be sent to the general practitioner and study participant, providing recommendations for the individual participant’s long-term gout management. Participants will be contacted by phone at months 24 and 36 by the study co-ordinators. Data regarding gout flare frequency, persistence of allopurinol and serum urate will be obtained.

Outcomes

The primary efficacy outcome of the RCT will be the proportion of participants achieving target urate (<0.36 mmol/L) at month 12. Key secondary outcomes include the number of gout flares over the study period, allopurinol-related treatment emergent adverse events over the period of study treatment and the difference in the number of interactions and the average time taken for each interaction with the health professionals between randomised groups. Box 1 summarises all the study outcomes.

Box 1. Study endpoints.

Primary outcome

The proportion of participants achieving target urate (<0.36 mmol/L) at month 12.

Key secondary outcomes

Number of gout flares over the study period.*

Allopurinol-related treatment emergent adverse events over the period of study.

Difference in the number of interactions and average time taken for each interaction with the health professionals between randomised groups.

Additional secondary outcomes (measured at 6 and 12 months unless otherwise stated)

Change in serum urate from baseline.*

Change from baseline in subcutaneous tophus count.*

Change from baseline in pain visual analogue score.*

Change from baseline in patient global assessment score.*

Change from baseline in health-related quality of life using the EQ-5D-5L.*

Change from baseline in activity limitation as measured by the Health Assessment Questionnaire-II.*

Proportion of participants who have at least one flare.*

Proportion of participants achieving target urate (<0.36 mmol/L) at month 6.

Proportion of participants taking any allopurinol.

Proportion of participants taking the prescribed allopurinol dose.

Adherence to allopurinol.

For those taking allopurinol, the mean allopurinol dose.

Proportion of people fulfilling the gout remission criteria.26

*This endpoint is one of the Outcomes in Rheumatology Clinical Trials (OMERACT) endorsed core domains for studies of chronic gout.27

Data collection

The following data will be collected at baseline and every 3 months for the first 12 months of the study using questionnaires: self-reported gout flares requiring treatment in the last 3 months as has been used in other studies of gout treatment,18 19 requirement for rescue therapy for gout flare in the last 3 months, work disability assessment (work status, days off work due to gout), Valuation of Lost Productivity Questionnaire, activity limitation assessment using the Health Assessment Questionnaire-II, pain using a 100 mm Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), tophus count, patient global assessment using a 100 mm VAS, health-related quality of life using the EQ-5D-5L and health costs using the OCC-Q.

Assessment and management of side effects

All medications included in this study are approved and funded for gout management in Aotearoa/New Zealand. Enquiry will be made regarding adverse events at each study visit using the side effect attribution scale. In the event of possible adverse events due to allopurinol, the principal investigator, subinvestigator (a medically qualified clinical research fellow) or the study nurse will assess the participant and arrange appropriate clinical management. Abnormal blood results will be classified and reported as clinically or not clinically significant. Adverse and serious adverse events will be recorded and reported according to the CTCAE V5 classification.

Data management

Deidentified data will be housed in REDCAP on a secure University of Otago server. Data will be recorded onto a paper case record form and then entered in a timely fashion by study nurses using a unique study identification number for each participant. Data checking will be undertaken prior to each data safety monitoring committee meeting during the study and prior to database lock at the end of the study. Checking will include range checks for data values.

Data safety monitoring committee

Safety in the study will be reviewed by an independent data safety monitoring committee comprising the study statistician, a clinical pharmacologist with clinical trial experience and an independent rheumatology expert. The data safety committee will review data every 6 months.

Statistical considerations

Power

Based on our previous data, ~80% of participants achieved target serum urate<0.36 mmol/L.11 A sample size of 190 per group is required to detect 15% non-inferiority (<65% achieve target urate), if the true serum urate target rates are the same in both groups, with 90% power. The 15% non-inferiority margin is well accepted in rheumatology RCTs, for example.20,22 The primary analysis of non-inferiority will be conducted using the per protocol sample of randomised participants, that is, excluding those participants with major protocol violations. We have sufficient statistical power such that if we had a 25% dropout, we still have >80% power. A sensitivity analysis will be undertaken using the intention-to-treat sample.

This is an open-labelled study of different allopurinol dosing strategies. While this carries a risk of bias, it is not feasible to undertake a blinded study. The primary endpoint is serum urate which is an objective laboratory measure.

Statistical methods

No interim efficacy or safety analyses are intended. All baseline demographic and clinical features will be summarised by randomised groups using means, medians, SD ranges and frequencies and percentages as appropriate. No formal hypothesis testing will be undertaken on the baseline measurements.

The analysis of the primary outcome will be undertaken using the Mantel-Haenszel χ2 test with stratification based on the randomised strata. The treatment effect will be summarised as the OR with 95% CI from this analysis. For those participants who withdraw or are lost to follow-up before 12 months, it will be assumed that the primary outcome (serum urate<0.36 mmol/L) has not been met. Non-inferiority will be shown if the upper two-sided 95% CI for the difference in percentages achieving target serum urate between arms (intensive treat-to-target—Easy-Allo) is less than 15%.

Secondary endpoints will be compared between randomised groups using logistic regression and general linear models dependent on the form of the outcome variable. These models may include the baseline levels of the dependent variables and stratum as covariates as appropriate. ORs, number needed treat, number needed to harm and mean differences with 95% CIs will be used to summarise the comparative efficacy of the randomised treatments. The analyses of the secondary endpoints will be tested as superiority comparisons, as we assume that these may favour the Easy-Allo arm. Sensitivity analyses for the secondary outcomes will be undertaken using the per protocol population. These analyses will be undertaken using SPSS. All tests will be two-tailed and a 5% significance level will be maintained. The analysis of the secondary endpoints will be based on the full analysis set as an intention-to-treat analysis.

All adverse and serious adverse events will be tabulated by system/organ class, severity and relatedness by randomised group as both frequency of event and percentage of participants experiencing the event. Key adverse events potentially related to allopurinol treatment, for example, rash, may be compared between randomised groups using χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests, as appropriate. A full statistical analysis plan will be developed.

We recognise the imperative to ensure that this research does not worsen existing health inequities.12 23 In Aotearoa/New Zealand, allopurinol is more likely to be dispensed regularly to non-Māori/non-Pacific peoples than Māori and Pacific peoples.24 In addition, NSAIDs, which can contribute to kidney disease and cardiovascular disease, are less frequently dispensed to non-Māori/non-Pacific peoples compared with Māori and Pacific peoples with gout.24 Our protocol and analysis plan has been developed with the Consolidated criteria for strengthening reporting of health research involving indigenous peoples (CONSIDER) statement in mind. We will use ethnicity reporting protocols as recommended by the New Zealand Ministry of Health and the CONSIDER statement.25 We will independently analyse the primary non-inferiority outcome and percentage achieving target urate within each of the three ethnicity groups. While these analyses have reduced statistical power, a non-inferiority margin of~25% will be detected as statistically significant with 80% power. In addition, key secondary outcome measures, including HR-QOL, flares and adherence with allopurinol, will also be analysed independently within the ethnicity strata.

Patient and public involvement

Two patient research partners have been involved in the development of this trial and are on the trial steering committee.

Ethics and dissemination

The New Zealand Northern B Health and Disability Ethics Committee approved the study (2022 FULL 13478). Participants will give informed consent to participate in the study before taking part. The study is sponsored by the University of Otago. Any protocol amendments will be notified to the ethics committee and Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry. Results will be disseminated in peer-reviewed journal and at national and international conferences. Local treatment guidelines will also be updated to reflect the findings.

Data sharing

Data will not be deposited in an external registry or shared for IPD analysis. Analysed data may be made available upon reasonable request following review by the trial steering committee with appropriate acknowledgements.

supplementary material

Footnotes

Funding: This work was supported by a Health Research Council of New Zealand programme under grant number [22/574].

Prepublication history and additional supplemental material for this paper are available online. To view these files, please visit the journal online (https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2024-084665).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not applicable.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods and analysis section for further details.

Contributor Information

Lisa Stamp, Email: Lisa.Stamp@cdhb.health.nz.

Leanne Te Karu, Email: ltekaru@xtra.co.nz.

Susan Reid, Email: sreid@healthliteracy.co.nz.

Daniel F B Wright, Email: dan.wright@sydney.edu.au.

Chris Frampton, Email: Chris.frampton@otago.ac.nz.

Vui Suli Tuitaupe, Email: suls@xtra.co.nz.

Nicola Dalbeth, Email: n.dalbeth@auckland.ac.nz.

References

- 1.Atlas of Healthcare Variation Health qaulity and safety commission of new zealand; gout domain 2021. www.hqsc.govt.nz/atlas n.d. Available.

- 2.Richette P, Doherty M, Pascual E, et al. 2016 updated EULAR evidence-based recommendations for the management of gout. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:29–42. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.FitzGerald JD, Dalbeth N, Mikuls T, et al. 2020 American college of rheumatology guideline for the management of gout. Arthritis Care & Research. 2020;72:744–60. doi: 10.1002/acr.24180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Son C-N, Stewart S, Su I, et al. Global patterns of treat-to-serum urate target care for gout: systematic review and meta-analysis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2021;51:677–84. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2021.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doherty M, Jenkins W, Richardson H, et al. Efficacy and cost-effectiveness of nurse-led care involving education and engagement of patients and a treat-to-target urate-lowering strategy versus usual care for gout: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;392:1403–12. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32158-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stamp LK, Chapman P, Hudson B, et al. The challenges of managing gout in primary care: results of a best-practice audit. Aust J Gen Pract . 2019;48:631–7. doi: 10.31128/AJGP-04-19-4909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stamp LK, Taylor WJ, Jones PB, et al. Starting dose is a risk factor for allopurinol hypersensitivity syndrome: a proposed safe starting dose of allopurinol. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:2529–36. doi: 10.1002/art.34488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Becker MA, Fitz-Patrick D, Choi HK, et al. An open-label, 6-month study of allopurinol safety in gout: The LASSO study. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2015;45:174–83. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2015.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bardin T, Keenan RT, Khanna PP, et al. Lesinurad in combination with allopurinol: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study in patients with gout with inadequate response to standard of care (the multinational CLEAR 2 study) Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:811–20. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stamp LK, Chapman PT, Barclay ML, et al. A randomised controlled trial of the efficacy and safety of allopurinol dose escalation to achieve target serum urate in people with gout. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:1522–8. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stamp LK, Chapman PT, Barclay M, et al. Allopurinol dose escalation to achieve serum urate below 6 mg/dL: an open-label extension study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:2065–70. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-211873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Te Karu L, Arroll B, Bryant L, et al. The inequity of access to health: A case study of patients with gout in one general practice. NZ Med J. 2021 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wright DFB, Dalbeth N, Phipps‐Green AJ, et al. The impact of diuretic use andABCG2genotype on the predictive performance of a published allopurinol dosing tool. Brit J Clinical Pharma. 2018;84:937–43. doi: 10.1111/bcp.13516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wright DFB, Duffull SB, Merriman TR, et al. Predicting allopurinol response in patients with gout. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;81:277–89. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wright DFB, Hishe HZ, Stocker SL, et al. The development and evaluation of dose‐prediction tools for allopurinol therapy (Easy‐Allo tools) Brit J Clinical Pharma . 2024;90:1268–79. doi: 10.1111/bcp.16005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neogi T, Jansen TLTA, Dalbeth N, et al. 2015 Gout classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:1789–98. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-208237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khanna D, Khanna PP, Fitzgerald JD, et al. 2012 American College of Rheumatology guidelines for management of gout. Part 2: therapy and antiinflammatory prophylaxis of acute gouty arthritis. Arthritis Care & Research. 2012;64:1447–61. doi: 10.1002/acr.21773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schumacher HR, Becker MA, Wortmann RL, et al. Effects of febuxostat versus allopurinol and placebo in reducing serum urate in subjects with hyperuricemia and gout: a 28‐week, phase III, randomized, double‐blind, parallel‐group trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:1540–8. doi: 10.1002/art.24209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sundy JS, Baraf HSB, Yood RA, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of pegloticase for the treatment of chronic gout in patients refractory to conventional treatment: two randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2011;306:711–20. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hetland ML, Haavardsholm EA, Rudin A, et al. Active conventional treatment and three different biological treatments in early rheumatoid arthritis: phase IV investigator initiated, randomised, observer blinded clinical trial. BMJ. 2020;371:m4328. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m4328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jørgensen KK, Olsen IC, Goll GL, et al. Switching from originator infliximab to biosimilar CT-P13 compared with maintained treatment with originator infliximab (NOR-SWITCH): a 52-week, randomised, double-blind, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2017;389:2304–16. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30068-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Austevoll IM, Hermansen E, Fagerland MW, et al. Decompression with or without fusion in degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:526–38. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2100990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Te Karu L, Dalbeth N, Stamp LK. Inequities in people with gout: a focus on Māori (Indigenous People) of aotearoa New Zealand. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2021;13:1759720X211028007. doi: 10.1177/1759720X211028007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dalbeth N, Dowell T, Gerard C, et al. Gout in aotearoa New Zealand: the equity crisis continues in plain sight. N Z Med J. 2018;131:8–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huria T, Palmer SC, Pitama S, et al. Consolidated criteria for strengthening reporting of health research involving indigenous peoples: the consider statement. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2019;19:173. doi: 10.1186/s12874-019-0815-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Lautour H, Taylor WJ, Adebajo A, et al. Development of preliminary remission criteria for gout using delphi and 1000minds consensus exercises. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2016;68:667–72. doi: 10.1002/acr.22741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schumacher HR, Taylor W, Edwards L, et al. Outcome domains for studies of acute and chronic gout. J Rheumatol. 2009;36:2342–5. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.090370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]