Abstract

Abstract

Introduction

The Westmead Centre for Adolescent and Young Adult Health is a purpose-built facility supporting integrated care for young patients with a variety of long-term health conditions transitioning from paediatric services at the Children’s Hospital at Westmead to adult services at Westmead Hospital, Australia.

Methods and analysis

This protocol outlines a prospective, within-subjects, repeated-measures longitudinal cohort study to measure self-reported experiences and outcomes of patients (12–25 years) and carers accessing transition care at the Centre for Adolescent and Young Adult Health. Longitudinal self-report data will be collected using Research Electronic Data Capture surveys at the date of service entry (recruitment baseline), with follow-ups occurring at 6 months, 12 months, 18 months and after transfer to adult services. Surveys include validated demographic, general health and psychosocial questionnaires. Participant survey responses will be linked to routinely recorded data from hospital medical records. Hospital medical records data will be extracted for the 12 months prior to service entry up to 18 months post service entry. All young people accessing services at the Centre for Adolescent and Young Adult Health that meet inclusion criteria will be invited to join the study with research processes to be embedded into routine practices at the site. We expect a sample of approximately 225 patients with a minimum sample of 65 paired responses required to examine pre–post changes in patient distress. Data analysis will include standard descriptive statistics and paired-sample tests. Regression models and Kaplan-Meier method for time-to-event outcomes will be used to analyse data once sample size and test requirements are satisfied.

Ethics and dissemination

The study has ethics approval through the Sydney Children’s Hospitals Network Human Research Ethics Committee (2021/ETH11125) and site-specific approvals from the Western Sydney Local Health District (2021/STE03184) and the Sydney Children’s Hospitals Network (2039/STE00977)2023/STE00977. Patients under the age of 18 will require parental/carer consent to participate in the study. Patients over 18 years can provide informed consent for their participation in the research. Dissemination of research will occur through publication of peer-reviewed journal reports and conference presentations using aggregated data that precludes the identification of individuals. Through this work, we hope to develop a digital common that can be shared with other researchers and clinicians wanting to develop a standardised and shared approach to the measurement of patient outcomes and experiences in transition care.

Keywords: Patients, Adolescent, Quality in health care

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

This research evaluates a novel service design for transition care in Australia.

This project features a comprehensive battery of experience and outcome measures to longitudinally assess the physical and emotional health of young patients in transition care.

Our battery of experience and outcome measures has been designed to be shared among Australian transition care services via Research Electronic Data Capture to assist the development of large-scale and national studies.

Poor participant retention and loss to follow-up are study risks and will require monitoring.

The future inclusion of comparator groups would strengthen our research approach.

Introduction

The period of adolescence and young adulthood provides a crucial juncture to intervene and improve long-term health trajectories for those living with complex and long-term health conditions.1,4 The 2021 Australian Census indicates that 15.2% of Australians aged 10–24 are living with at least one long-term health condition and this increases to 23.9% when considering mental health conditions.5 Most adolescents and young adults (AYAs) receiving paediatric care for long-term health conditions will require ongoing adult care while also navigating physical, mental and social developmental changes.4

Transition care assists young people to make a purposeful and planned move from child-centred to adult-centred healthcare.1 2 Successful transition supports the physical, mental and social well-being of young people allowing them to manage their condition and progress independently to adopt adult roles.1,4 Poor transition has detrimental impacts including non-adherence to treatment, missed appointments, poor clinical outcomes, reduced quality of life, increased emergency department (ED) presentations and greater costs to health systems.36,8

Best practice guidelines from the New South Wales Agency for Clinical Innovation1 recommend transition to be supported through dedicated transition support services, formal planning, early preparation, support from a transition coordinator/facilitator, strong communication (between health professionals, young people and family members), the development of an individual transition plan, a focus on empowering young people to self-manage their condition, and follow-up and evaluation of transition outcomes. While this serves as a comprehensive framework for effective transition care, in practice the unique and complex needs and service requirements of patients requiring transition care are often still unmet.8 9

Historical approaches to transition care have been criticised for providing fragmented, inflexible, episodic and non-integrated care that features limited planning or coordination of the transition process and minimal post-transition oversight or engagement.10,14 Differing guidelines and support across conditions11 and differing models of care between paediatric and adult services have been suggested to lead to inconsistencies in the provision of care.10 Furthermore, clinical services assisting young people with transition have been criticised for limited or difficult-to-access wrap-around services (eg, allied health and transition support).13 14 Modifications to these historically based models of care can help ensure responsiveness to the evolving demands of patients and modern health systems15 but require thoughtful development and implementation.

There are several challenges to the development, implementation and sustainability of effective transition care services. One challenge is the diversity and complexity of presenting issues for many young people transitioning to adult care. There are numerous conditions requiring transition care5 and young people in transition may present with comorbid physical, mental and psychosocial concerns that require access to a variety of treatment services (eg, physiotherapists, dieticians, nurse educators, pharmacists, psychologists, psychiatrists and social workers).4 14

A related challenge is the disjointed nature of the paediatric and adult health systems in Australia11 and worldwide.16 For example, the adult services that a young person transitions to are typically (a) in different geographical locations, (b) may not be well supported by nursing and allied health services and other multidisciplinary supports and (c) will usually involve different electronic medical records (EMRs) and billing systems. This potential for fragmented service delivery is likely to have negative impacts on service access, care coordination, quality and efficiency.11 14 Insufficient resourcing, experience and/or training of health professionals within these receiving adult services may further exacerbate these systems issues.17

Between 2016 and 2019, the Westmead Hospital (WH) and the Sydney Children’s Hospital at Westmead (CHW) engaged in a process of consultation and codesign with stakeholders from both hospital services to develop a new shared approach to adolescent medicine and transition care to combat the above-mentioned challenges. This engagement process led to the proposal, development, planning and establishment of the Westmead Centre for Adolescent and Young Adult Health (CAYAH).

The Westmead Centre for Adolescent and Young Adult Health

The CAYAH is a new purpose-built and co-located facility designed to support the integrated delivery of services for AYAs with complex chronic conditions and/or disabilities by specialty teams at the Sydney CHW and WH, Australia. CHW is the largest children hospital in New South Wales.18 It has a remit of care for over 5 million children and AYAs and sits adjacent to WH, similarly one of the largest adult hospitals in NSW.19 The CAYAH is situated in the footprint of the adult hospital (WH) and features a consultant-to-consultant, patient-centred, model of transition care for young people living with long-term health conditions. Transition teams from both paediatric and adult settings are co-located, with the integration of medical (paediatric and adult), allied health and mental health professionals to address medical and non-medical issues in a holistic patient-centred approach. A focus on research and evidence-based practice is a central tenet of the CAYAH model. A challenge for evaluating the effectiveness of the CAYAH model relates to difficulties with the measurement and evaluation of the effectiveness of dedicated transition programmes. To date, there have been few established criteria to define what constitutes a successful transition9 and this lack of a common language makes it difficult to compare the effectiveness of different transition care services or interventions. There have been calls for standarised measures in transition care.10

The purpose of this paper is to provide a brief overview of the CAYAH model of care and outline a research protocol and monitoring framework designed to examine outcomes and experiences for CAYAH patients and their carers over time that can be shared and utilised by other transition services.

Aim and research questions

We aim to monitor outcomes and experiences for patients and carers accessing the CAYAH. The key research questions are as follows:

Does the CAYAH model of care support positive mental health outcomes and quality of life outcomes for young people and their carers over time?

Does the CAYAH model of care support adherence to care plans, confidence to manage healthcare and transition readiness for young people and their carers over time?

Does the CAYAH model of care deliver a positive experience of service for young people and their carers in terms of providing information and support, valuing individuality, supporting active participation, showing respect, and ensuring safety and fairness?

Do mental health outcomes and quality of life outcomes differ between CAYAH clinical cohorts over time?

Do adherence to care plans, confidence to manage healthcare and transition readiness differ between CAYAH clinical cohorts over time?

Does the experience of service (providing information and support, valuing individuality, supporting active participation, showing respect, and ensuring safety and fairness) differ between CAYAH clinical cohorts over time?

We hypothesise that the CAYAH model of care will lead to within-subject improvements in psychosocial and clinical outcomes and that patients and carers will report positive experiences of care. No directional hypotheses are made for differences between CAYAH clinical cohorts.

Methods and analysis

The CAYAH service model

The CAYAH service is a co-located facility that can be physically accessed from both the WH and the CHW. The goal of the CAYAH service is to provide continuous, coordinated, developmentally appropriate and psychologically supported AYA healthcare. While most published models to support healthcare transition for adolescents have been disease-specific (ie, focusing on a single condition),9 13 20 21 the CAYAH service embeds a transdiagnostic approach to transition with a focus on person-centred, integrated care.

Establishing a new service model necessitates the development of skills, systems, processes and resources.15 The CAYAH service model outlines the core elements and principles for transition care and provides a structure for implementation and monitoring efforts. In brief, the CAYAH service features a purpose-built and co-located facility that features a reception area, consult, interview and treatment rooms, a clinical support zone for resuscitation and advanced life support, a large multipurpose meeting space with audio visual capabilities, a staff work room with printers and computers, breakout spaces for both staff and patients, multiple bathrooms, facilities to support both face-to-face and telehealth appointments and facilities to support teaching and research (eg, computers, software and equipment).

The CAYAH has an overarching governance committee with representatives from CHW and WH and features shared care guidelines and joint decision-making processes for service developments with representatives from both hospitals. The CAYAH includes specialist clinics including single specialty and joint clinics with staff from both hospitals, multidisciplinary subspecialty teams including medical, nursing and allied health from both hospitals, generalist services AYA services from both hospitals including both physical and mental health, transition support services (Trapeze and Agency for Clinical Innovation) and receives administrative support (ie, receptionists) from both hospitals.

The CAYAH model aspires to provide shared and simultaneous access to Information Technology (IT) and paediatric (CHW) and adult (WH) EMR systems (CHW CERNA and WH IPM) for staff employed at both hospitals. Initially, the document of truth is the CHW EMR. This changes to the WH EMR when the primary clinician changes from paediatric (CHW) to adults (WH). Billing follows the consultant and is triggered through the shared booking systems (CHW CERNA and WH IPM). There are no costs for consultation to the patient which is covered by Australia’s universal health insurance scheme (Medicare).

The CAYAH service model and space have been designed to be developmentally appropriate for young people with principles of AYA care22 and the Agency for Clinical Innovation best practice guidelines for youth transition1 embedded into routine practice, including developmental and psychosocial assessments to inform care decisions. The service model is person-centred emphasising the importance of assisting patients to be active in their own care, supporting development of skills of independence and provision of patient self-management resources. Generalist AYA services (both physical and mental health) are embedded into specialist clinics, with wrap-around services available to promote cohesive team-based and person-centred care. Case conferences occur in collaboration with patients and family members/carers.

Coordinated care is enabled through co-location, an overarching governance committee, centralised facilitated site onboarding for staff employed at both hospitals, shared access to IT systems, shared streamlined booking systems, shared service developments which feature representatives from both adolescent and children’s services (WH and CHW), and integration of medical (paediatric and adult), allied health and mental health professionals to address medical and non-medical issues. The workforce and transition processes are organised so that the transition to adult care is an ongoing progression rather than a discrete event, ensuring continuity of care. The idea of cohorting clinics attended by both paediatric (CHW) and adult (WH) hospital staff is that this permits a patient-centred approach in decision-making about transition. When a young person is ready, the primary clinician changes from paediatric (CHW) to adults (WH). However, treating paediatric clinicians (CHW) are still available and involved as needed by the patient.

The objectives of the CAYAH service are as follows:

To provide a variety of treatment services to meet the full scope of needs of AYAs, families and clinicians.

To support the implementation of personal transition plans for all young people receiving transition care at the CAYAH.

To function as an easily accessible, supportive and safe, youth-friendly care environment for all AYA patients who receive ambulatory care from Westmead Hospital and The Sydney CHW.

To provide a relevant and welcoming space for AYAs via collaborative planning with young people through the Westmead Youth Council and Sydney Children’s Hospitals Network (SCHN) Youth Advisory Council providing peer support and creative activities.

To link healthcare providers from paediatric and adult settings through access to consulting spaces with visibility of medical information across all treatment settings and access to clinical investigation and treatment resources to meet their specialist needs.

To provide a venue with physical space and connectivity to facilitate collaborative education training and research.

To collect data guided by principles of implementation science to evaluate transition outcomes and experiences.

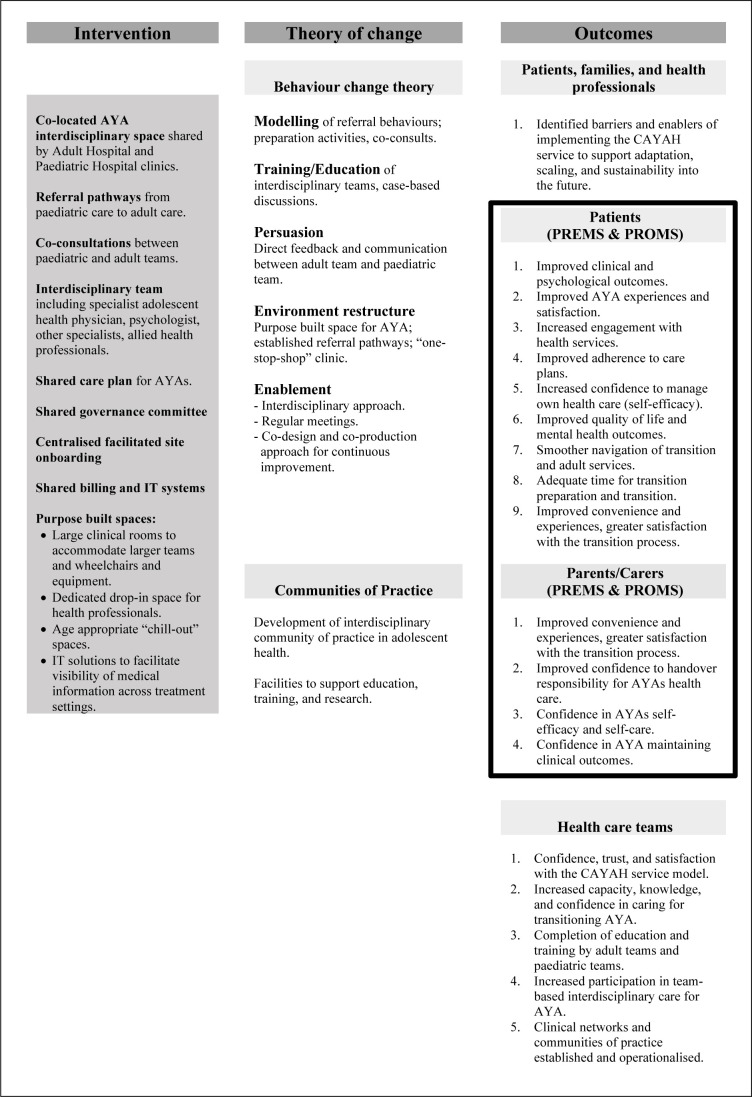

The key aspects of the CAYAH service model have been incorporated into programme logic model (figure 1) that outlines the key inputs of the service model and the expected outcomes for young people, families and healthcare professional teams. The programme logic model allows for the development of research evaluation frameworks to monitor and assess intervention and implementation success. This paper presents a research protocol to determine outcomes and experiences for patients and carers accessing the CAYAH. Therefore, this research protocol focuses on patient and carer PREMS and PROMS only.

Figure 1. Programme logic model. AYA, adolescents and young adult; CAYAH, Centre for Adolescent and Young Adult Health; PREMS, patient and carer-reported experience measures, PROMS, patient and carer-reported outcomes measures.

Study design

This research uses a prospective, within-subjects and between-subjects (mixed) repeated-measures longitudinal cohort study design. Data will be collected using patient and carer-reported outcomes measures, patient and carer-reported experience measures and data linkage to the hospital EMRs from the Westmead Hospital and the SCHN. No control groups will be used for the current study.

Participants

AYA patients accessing services through the CAYAH and their parents/carers who fit the below study criteria will be invited to participate in the research project. AYAs with intellectual disabilities will be invited to participate using easy-read participant information statements and consent forms with assistance able to be provided as needed by carers or staff to complete surveys.

Inclusion criteria

CAYAH patients (12–17 years) who assent to participation with parent/carer consent.

CAYAH patients (18–25 years) who consent to participation.

Carers of CAYAH patients who consent to participation.

CAYAH patients and carers able to speak and read English.

Exclusion criteria

Patients who do not give consent for data collection.

Patients or carers who do not speak or read English.

Measures

The CAYAH programme logic outcomes (figure 1) guided development of the measurement framework (table 1). Table 1 outlines the demographic, general health and psychosocial information measures used for AYAs and carers involved in the study. These have been chosen for their focus on the AYA group, psychometric properties, comparability with existing literature and minimisation of reporter burden.23,33 Online supplemental file 1 expands on this table to indicate the number of items per measure and the occasions on which data will be collected. Staggered presentation of survey measures across time points allows the research team to capture longitudinal data while limiting the number of items per presentation. We estimate the longest time commitment across any one survey will be at baseline (max 20 min). Each of the patient and carer measures is outlined below.

Table 1. CAYAH measurement framework*.

| Input/outcome | Measure | |

| EMR | Unplanned ED presentations and hospitalisations | Electronic medical records (EMRs) |

| Engagement with CAYAH service | EMRs | |

| Clinical outcomes | EMRs | |

| AYA patient self-report | Demographics | Demographics questionnaire |

| Mental health outcomes | Kessler Psychological Distress Scales23 24 | |

| Adherence to care plans | Simplified Medication Adherence Questionnaire25 | |

| Medical Outcomes Study–General Adherence items26 | ||

| Confidence to manage healthcare | The On Your Own Feet Self Efficacy Scale (OYOF)27 28 | |

| Quality of life | PROMIS Scale Global Health (PROMIS-10)29 | |

| Navigation of transition and adult services | OYOF-Transfer Experiences Scale (OYOF-TES): Subscale A28 30 | |

| Time for transition preparation and transition | OYOF-TES: Subscale B28 30 | |

| Convenience and service experience | Your Experience of Service (YES) Scale31 | |

| Parent/carer self-report | Demographics | Demographics questionnaire |

| Confidence to handover responsibility for AYAs healthcare | Readiness to Transition Questionnaire (Parent report)32 | |

| Confidence in AYAs self-efficacy and self-care | On Your Own Feet Self Efficacy Scale–Parent report27 28 | |

| Confidence in AYA maintaining clinical outcomes | Single item Health Confidence measure33 | |

| Convenience and service experience | Modified YES Scale31 |

Note: Measurement presentation staggered over time- points to reduce participant load.

AYAsadolescents and young adultsCAYAHCentre for Adolescent and Young Adult HealthPROMISPatient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System

Electronic medical records

Routine EMR data will be extracted from the Western Sydney Local Health District (WSLHD) IPM Patient Administration System and the SCHN Cerner Electronic Health Record System using a unique study ID assigned to each consenting participant as a linkage key. EMR data will be used to examine the following outcomes:

Unplanned ED presentations and hospitalisations data will be extracted from EMRs for each participant. We will extract retrospective data from 12 months prior to the patient’s first CAYAH appointment and will iteratively extract prospective data throughout the duration of the CAYAH study.

Patient engagement with the CAYAH service will be measured through routine EMR data on attendance/absence at CAYAH appointments and retention/drop-out from CAYAH services.

Clinical outcomes will be measured using routine measures of illness-specific clinical outcomes. Disease/self-management biomarkers and outcomes (eg, haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) for type I diabetes) will be used where appropriate if sample sizes are appropriate for subgroup analyses of patient groups.

Patient self-report measures

The Demographics Questionnaire for young people will ask basic demographic information including date of birth, gender and gender identity, ethnicity, country of birth, education history, living arrangements and financial information relevant to the young person and their carer.

The Kessler Psychological Distress Scale23 24 is a self-report measure composed of six items intended as a global measure of distress based on questions about anxiety and depressive symptoms that a person has experienced in the most recent 4-week period. It is a well-validated clinical measure of psychological symptoms noted for its accessibility, high predictability and ease of use.

The Simplified Medication Adherence Questionnaire25 is a valid and reliable six-item measure of medication adherence that asks general questions about medication adherence that can be applied in most clinical settings.

The Medical Outcomes Study General Adherence Items26 is a five-item self-report scale that measures general adherence to medical advice over the past 4 weeks. The scale demonstrates good internal consistency (alpha=0.81) and has been used previously with patients with chronic disease.26

The On Your Own Feet Self Efficacy Scale (OYOF-SES)27 28 measures disease-related self-efficacy. It was developed for use with adolescents transitioning from paediatric to adult health services. The 17-item version shows good validity and internal consistency of subscales.

The PROMIS Scale Global Health29 is a 10-item self-report measure of health-related quality of life. The measure allows for the calculation of two 4-item summary scores for global physical health and global mental health. It can also be used in cost–utility analyses to support economic evaluations of interventions.

The OYOF-TES28 30 is an 18-item self-report scale developed specifically for measuring satisfaction and experiences of adolescents transitioning from paediatric to adult health services. The scale shows good internal consistency, reliability and validity.

The Your Experience of Service (YES) Scale31 was developed through an Australian government-funded project to develop a survey for use in public mental health services. The YES survey features 28 service items designed to gather information from consumers about their experiences of care.31 The YES scale has been validated and is designed for use across general Australian health services. It features six subfactors: Making a difference, providing information and support, valuing individuality, supporting active participation, showing respect, and ensuring safety and fairness.

Carer self-report measures

The Demographics Questionnaire for parents/carers will ask for basic demographic information including date of birth, gender and gender identity, ethnicity, country of birth, education history, living arrangements and financial information relevant to the young person and their carer.

The Readiness to Transition Questionnaire–Parent (RTQ)32 assesses parental/carer perceptions of an adolescent’s overall transition readiness and responsibility for healthcare behaviours measured on 4-point Likert scale. Research indicates that the RTQ demonstrates good internal consistency, inter-rater reliability, construct validity and criterion-related validity.32

The OYOF-SES–Parent27 28 measures parental/carer perceptions of an adolescent’s disease-related self-efficacy relating to knowledge, skills for consultations and coping ability. It is a self-report measure for parents and carers of adolescents transitioning from paediatric to adult health services. The 17-item version of this measure uses the same items at the OYOF-SES 1727 28 with appropriate wording changes to make it suitable for parents or carers.

The YES Scale–Parent31 will use amended language to make the YES Scale suitable for parents or carers. Analyses of the internal reliability and criterion-related validity of the amended scale will be conducted as part of the research study.

The Single-Item Health Confidence Measure33 is a single-item visual analogue measure developed by Dartmouth College that examines how well an individual believes they can control and manage health problems. The measure has been shown to have criterion-related validity in prior studies.33

Study procedures will be embedded into routine workflows. Recruitment, consent and data collection will be led by the Academic Department of Adolescent Medicine (The Children’s Hospital at Westmead) and supported by CAYAH administrative officers and research students with appropriate ethics and governance clearance.

Recruitment, consent and baseline data collection will occur either in-person at the CAYAH or online with follow-up data collection completed using online surveys. Follow-up will occur at 6, 12 and 18 months intervals for young people, and 6 and 12 months intervals for carers. A questionnaire will also be provided when the patient transfers to adult services. Survey responses will be linked to EMRs data from Westmead Hospital and the Sydney CHW to examine relationships between survey responses, engagement with CAYAH (attendance rates and drop-outs) and unplanned emergency presentations and hospitalisations.

Recruitment and consent

Participants will be identified and recruited consecutively through upcoming CAYAH appointment records. If attending on-site, the young person and their parent/carer (if present) will be informed of the study by administrative staff. Interested parties will be approached by a research team member to obtain informed consent. Patients receiving virtual care will be emailed the participant information statements. The email will contain a link to a Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCAP) form held in the NSW Health Office of Medical Research REDCap34—a secure, online platform built for the management of research data. The initial REDCap form will be used to obtain informed consent. Consent for continued contact will be sought. Young people under the age of 18 will require parental/carer consent to participate. Our recruitment system features an approach to the young person first. If the young person does not wish to participate or does not wish their carer to participate, we will not recruit them into the study.

Baseline data collection

Baseline data collection will be achieved through access to a REDCap survey. If required, on-site participants will be supplied with a CAYAH-owned iPad for the purpose of data entry. When the survey is commenced, an introductory video will open within REDCap. This video will outline the study’s purpose and reinforce survey instructions. Survey entry will require a unique study ID (provided on the instruction sheet for participation). This ID code will be used as a linkage key to link patient EMRs data to survey data. Patients receiving virtual care will be emailed a hyperlink to the baseline REDCap survey and their unique study ID number. Completion of the consent form will trigger a separate REDCAP survey to collect study data while maintaining deidentified responses.

Follow-up data collection

Follow-up surveys will be emailed to participants at 6, 12 and 18 months follow-up periods and when the participant transfers to adult care. Prior to email surveys being sent, a research team member will call participants to remind them of the study purpose and answer questions. Phone calls will be limited to one contact per survey round. Reminder emails will be automated through REDCap and limited to one reminder per survey round.

Participants completing surveys will be entered into a draw for gift card prizes as compensation for their time. A total of three draws will occur at 12, 24 and 30 months post study initiation. Gift cards will be to the value of $A250 and will not be able to be used for the purchase of alcohol, gambling services or cigarettes.

Sample size and power calculations

Based on the presentation data for relevant services based at CHW and WH, we have calculated the expected number of young people attending the CAYAH service within the first 12 months to be 900. Assuming we recruit 50% of young people attending the service in the first 12 months and retain 50% of those recruited (ie, completing all surveys). This would provide us with a complete data set for a sample of 225 young people for the study. Nevertheless, we have used a conservative approach to power the study to ensure the ability to conduct statistical analyses in case of any unexpected issues with recruitment or retention. The Kessler 6 measure was used as the key outcome for powering the study because it has the most published data that can be used to conduct power calculations. Prior research indicates 5 scoring strata within the scoring distribution of the Kessler 6 measure that show significantly different rates of mental health diagnoses.15 A 2017 analysis of 25 767 responses from the individuals living in the USA indicates a mean score of 2.8 with an SD of 4.0.35 Using a 2-point change in score as reflective of clinically meaningful change and an SD of 4, we calculate the study will require a sample size of 34–65 paired responses to achieve a power of 80% and a level of significance of 5% (two sided), to detect a difference of 2, assuming moderate to low correlation between the pretreatment and post-treatment responses in the same participant. This conservative approach indicates the minimum number of paired responses needed to identify a statistically significant change even if there is lower reliability of the Kessler 6 measure over time.

Data analysis

Demographic and clinical characteristics of participants and survey responses will be analysed with standard descriptive statistics; means and SD or median and IQRs for continuous variables, frequencies, and proportions for categorical variables. Paired-sample tests will be used to examine within-participant changes in outcomes over time. These will be primarily focused on changes in the total cohort, however, if there are sufficient data from participants in the individual disease conditions, these will be explored separately and compared between groups. Further statistical approaches will be used as appropriate and if sample size requirements and underlying test assumptions are met. For example, clinical groups and other predictors of outcomes will be explored using appropriate regression models (including linear, logistic and proportional hazards models) and will account for the potential correlation between repeated outcomes in the same participant where applicable. The Kaplan-Meier method will be used for time-to-event outcomes as appropriate.

Patient and public involvement

The development of the research protocol included some patient and public involvement. The aim of the patient and public involvement was to determine the potential burden and acceptability of the research processes for study participants (ie, survey completion times and survey load). To achieve this, the survey was pilot tested with youth being treated with chronic conditions at the SCHN. Feedback on a presentation of the research design and processes was also sought from a youth advisory group with lived experience of engagement with the Australian health system. Feedback from these groups informed decisions on the number and timing of survey measures, approaches to recruitment and consent, and methods for recognising and compensating study participants for their time.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics statement

This study has been approved by the SCHN HREC (2021/ETH11125) with site-specific approvals from the WSLHD (2021/STE03184) and the SCHN (2023/STE00977). AYAs under the age of 18 will require parental/carer consent to participate in the study. AYAs over 18 years can provide informed consent for their participation in the research.

Dissemination

Dissemination of research findings will occur through publication in peer-reviewed journal articles, academic conference presentations and internal presentations to health services at CHW and WH. All dissemination of research will use aggregated data that precludes identification of individuals. All electronic study data will be saved in a firewall-protected folder on the internal drives of the Sydney CHW. Access to this folder will be restricted to the study team. Standard hospital protocols for internal data linkage and sharing deidentified data securely are in place. Hard copy information (eg, participant consent forms) will be stored in a locked cabinet at the CAYAH.

Timetable

The CAYAH opened in July 2023 with clinics from both hospitals progressively coming into the space. Participant recruitment for the research study started at this time also. We anticipate the first wave of recruitment to conclude within 12 months of study initiation. Planned ethics amendments will be submitted as the study evolves and the CAYAH service model is adjusted where clinically necessary. Partnerships with Western Sydney University and the University of Sydney have been established to support research activities and the engagement of research students. The research team is engaged in discussions with other health providers to develop a research collaborative and plan to use the REDCap surveys established for this project as a shared asset (digital common) available to other teams working in the field of AYA transition care. Further work is planned to examine implementation of the CAYAH model and outcomes for health professionals as outlined in the CAYAH programme logic.

Discussion

This research protocol presents a longitudinal approach towards the measurement of transition outcomes for patients and carers accessing a new service model of transition care that focuses on coordination of care throughout the transfer from paediatric to adult hospital services. This project features a comprehensive battery of experience and outcome measures to longitudinally assess the physical and emotional health of young patients in transition care. Our battery of experience and outcome measures has been designed to be shared among Australian transition care services via REDCap to assist the development of large-scale national studies and the development of comparator groups.

A generic model of patient-centred consumer-informed care where releasing and receiving healthcare teams work together and are supported by relevant data collection will fill a major knowledge gap in the transition literature. The establishment of a digital common will help researchers to develop a shared language for transition care research and will allow for the inclusion of control groups in future studies, as well as the potential to expand this data set and system of data collection to other transition services in Australia and internationally. It is anticipated that rigorous evaluation including much needed quantitative data and all stakeholders’ input will create better experiences and outcomes through integrated health services and care continuity for AYAs with complex and long-term conditions.

A key limitation of the current research design is the lack of a comparator group to evaluate contrasting outcomes achieved through different service models. However, the continuing nature of CAYAH service model development poses difficulties when employing conventional evaluation approaches such as randomised controlled trials that feature a comparator group. Pre–post test and case study designs are thus well suited for measuring outcomes and monitoring the effectiveness of evolving care models such as those employed at the CAYAH.15 Importantly, this design entails that poor participant retention and loss to follow-up are study risks that will require monitoring throughout the conduct of the research project.

Through our work (and publishing this protocol), we plan to develop a digital common (ie, a databank available to researchers working in transition care). It is our hope to establish a shared approach to the measurement of transition outcomes across services in Australia that allows for the comparison of service approaches and the development of control/comparator groups for research. We anticipate that this generic approach can then be supplemented by condition or environment-specific measures to further improve evaluation fidelity. Progress is underway with other transition services to move towards this coordinated and replicable approach to the evaluation of transition care.

supplementary material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Maddison Marsh, Jolene Haines and Cassandra Kwok for assistance with project management and data collection. We also thank our research participants and the young people who assisted with pilot testing of research design and surveys for their generous contributions. Additionally, we thank the staff of the Academic Department of Adolescent Medicine at the Children’s Hospital at Westmead and the staff working at the Centre for Adolescent and Young Adult Health for their support. We acknowledge the funding support of the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) and the contributions of our research partners in universities across Australia. This research was conducted at Westmead on the traditional lands of the Dharug people.

Footnotes

Funding: DW, KS and SM are researchers in the Wellbeing Health & Youth (WH&Y) Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Centre of Research Excellence in Adolescent Health (APP 1134984).

Prepublication history and additional supplemental material for this paper are available online. To view these files, please visit the journal online (https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2023-080149).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not applicable.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Contributor Information

Daniel Waller, Email: drdanwaller@gmail.com.

Katharine Steinbeck, Email: kate.steinbeck@health.nsw.gov.au.

Yvonne Zurynski, Email: yvonne.zurynski@mq.edu.au.

Jane Ho, Email: jane.ho@health.nsw.gov.au.

Susan Towns, Email: susan.towns@health.nsw.gov.au.

Jasmine Milojevic, Email: Jasmine.Milojevic@health.nsw.gov.au.

Bronwyn Milne, Email: bronwyn.milne@health.nsw.gov.au.

Sharon Medlow, Email: sharon.medlow@sydney.edu.au.

Ediane De Queiroz Andrade, Email: Ediane.DeQueirozAndrade@health.nsw.gov.au.

Frances L Doyle, Email: F.Doyle@westernsydney.edu.au.

Michael Kohn, Email: michael.kohn@health.nsw.gov.au.

References

- 1.Agency for Clinical Innovation Key principles for transition care. 2022. https://aci.health.nsw.gov.au/networks/transition-care/resources/key-principles Available.

- 2.Blum RW, Hirsch D, Quint RD, et al. A consensus statement on health care transitions for young adults with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 2002;110:1304–6. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.S3.1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ravens E, Becker J, Pape L, et al. Psychosocial benefit and adherence of adolescents with chronic diseases participating in transition programs: a systematic review. J Trans Med. 2020;2 doi: 10.1515/jtm-2020-0009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sawyer SM, Drew S, Yeo MS, et al. Adolescents with a chronic condition: challenges living, challenges treating. Lancet. 2007;369:1481–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60370-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Australian Bureau of Statistics . Census of Population and Housing Health Data Summary: Information on Long-Term Health Conditions. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bloom SR, Kuhlthau K, Van Cleave J, et al. Health care transition for youth with special health care needs. J Adolesc Health. 2012;51:213–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jarvis SW, Roberts D, Flemming K, et al. Transition of children with life-limiting conditions to adult care and healthcare use: a systematic review. Pediatr Res. 2021;90:1120–31. doi: 10.1038/s41390-021-01396-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vaks Y, Bensen R, Steidtmann D, et al. Better health, less spending: redesigning the transition from pediatric to adult healthcare for youth with chronic illness. Healthc (Amst) 2016;4:57–68. doi: 10.1016/j.hjdsi.2015.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agency for Clinical Innovation . Transition Models of Care: Evidence Check. Agency for Clinical Innovation; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou H, Roberts P, Dhaliwal S, et al. Transitioning adolescent and young adults with chronic disease and/or disabilities from paediatric to adult care services - an integrative review. J Clin Nurs. 2016;25:3113–30. doi: 10.1111/jocn.13326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Samarasinghe SC, Medlow S, Ho J, et al. Chronic illness and transition from paediatric to adult care: a systematic review of illness specific clinical guidelines for transition in chronic illnesses that require specialist to specialist transfer. J Trans Med. 2020;2 doi: 10.1515/jtm-2020-0001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Soanes C, Timmons S. Improving transition: a qualitative study examining the attitudes of young people with chronic illness transferring to adult care. J Child Health Care. 2004;8:102–12. doi: 10.1177/1367493504041868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marani H, Fujioka J, Tabatabavakili S, et al. Systematic narrative review of pediatric-to-adult care transition models for youth with pediatric-onset chronic conditions. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2020;118:105415. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105415. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fazel M, Townsend A, Stewart H, et al. Integrated care to address child and adolescent health in the 21st century: a clinical review. JCPP Adv. 2021;1:e12045. doi: 10.1002/jcv2.12045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davidson P, Halcomb E, Hickman L, et al. Beyond the rhetoric: what do we mean by a “model of care”? Aust J Adv Nurs. 2006;23:47–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ehrich J, Namazova-Baranova L, Pettoello-Mantovani M. Introduction to “diversity of child health care in europe: a study of the european paediatric association/union of national european paediatric societies and associations.”. J Pediatr. 2016;177S:S1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steinbeck K, Towns S, Bennett D. Adolescent and young adult medicine is a special and specific area of medical practice. J Paediatr Child Health. 2014;50:427–31. doi: 10.1111/jpc.12491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sydney Children’s Hospitals Network About the children’s hospital at westmead. https://www.schn.health.nsw.gov.au/about/our-network/childrens-hospital-westmead n.d. Available.

- 19.About westmead hospital: NSW health. https://www.wslhd.health.nsw.gov.au/Westmead-Hospital/Westmead-Hospital n.d. Available.

- 20.Betz CL, O’Kane LS, Nehring WM, et al. Systematic review: health care transition practice servicemodels. Nurs Outlook. 2016;64:229–43. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2015.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crowley R, Wolfe I, Lock K, et al. Improving the transition between paediatric and adult healthcare: a systematic review. Arch Dis Child. 2011;96:548–53. doi: 10.1136/adc.2010.202473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.NSW Health . NSW Youth Health Framework 2017-24. North Sydney: NSW Ministry of Health; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ, et al. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol Med. 2002;32:959–76. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702006074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kessler RC, Green JG, Gruber MJ, et al. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population with the K6 screening scale: results from the WHO world mental health (WMH) survey initiative. Int J Methods Psych Res. 2010;19:4–22. doi: 10.1002/mpr.310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Knobel H, Alonso J, Casado JL, et al. Validation of a simplified medication adherence questionnaire in a large cohort of HIV-infected patients: the GEEMA study. AIDS. 2002;16:605–13. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200203080-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hays RD, Kravitz RL, Mazel RM, et al. The impact of patient adherence on health outcomes for patients with chronic disease in the medical outcomes study. J Behav Med . 1994;17:347–60. doi: 10.1007/BF01858007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Staa A, van der Stege HA, Jedeloo S, et al. Readiness to transfer to adult care of adolescents with chronic conditions: exploration of associated factors. J Adolesc Health. 2011;48:295–302. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Staa A. On your own feet: adolescents with chronic conditions and their preferences and competencies for care. TIJDSCHR KINDERGENEESK. 2012;80:151–2. doi: 10.1007/s12456-012-0043-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hays RD, Bjorner JB, Revicki DA, et al. Development of physical and mental health summary scores from the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) global items. Qual Life Res. 2009;18:873–80. doi: 10.1007/s11136-009-9496-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Staa A, Sattoe JNT. Young adults’ experiences and satisfaction with the transfer of care. J Adolesc Health. 2014;55:796–803. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Australian Government Department of Health Your experience of service Australia’s national mental health consumer experience of care survey: guide for licensed organisations and organisations seeking a licence to use the instrument. Nat Ment Health Info Strat Stand Comm. 2017

- 32.Gilleland J, Amaral S, Mee L, et al. Getting ready to leave: transition readiness in adolescent kidney transplant recipients. J Pediatr Psychol. 2012;37:85–96. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsr049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wasson J, Coleman EA. Health confidence: an essential measure for patient engagement and better practice. Fam Pract Manag. 2014;21:8–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (redcap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tomitaka S, Kawasaki Y, Ide K, et al. Distribution of psychological distress is stable in recent decades and follows an exponential pattern in the US population. Sci Rep. 2019;9:11982. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-47322-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]