Abstract

Background

Percent slowing of decline is frequently used as a metric of outcome in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) clinical trials, but it may be misleading. Our objective was to determine whether percent slowing of decline or Cohen’s d is the more valid and informative measure of efficacy.

Methods

Outcome measures of interest were percent slowing of decline; Cohen’s d effect size, and number-needed-to-treat (NNT). Data from a graphic were used to model the inter-relationships among Cohen’s d, placebo decline in raw score units, and percent slowing of decline with active treatment. NNTs were computed based on different magnitudes of d. Last, we tabulated recent AD anti-amyloid clinical trials that reported percent slowing and for which we computed their respective d’s and NNTs.

Results

We demonstrated that d and percent slowing were independent. While percent slowing of decline was dependent on placebo decline and did not include variance in its computation, d was dependent on both group mean difference and pooled standard deviation. We next showed that d was a critical determinant of NNT, such that NNT was uniformly smaller when d was larger. In recent AD associated trials including those focused on anti-amyloid biologics, d’s were below 0.23 and thus considered small, while percent slowing was in the 22%-29% range and NNTs ranged from 14-18.

Conclusions

Standardized effect size is a more meaningful outcome than percent slowing of decline because it determines group overlap, which can directly influence NNT computations, and yield information on the likelihood of minimum clinically important differences. In AD, greater use of effect sizes, NNTs, rather than relative percent slowing, will improve the ability to interpret clinical trial results and evaluate the clinical meaningfulness of statistically significant results.

INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer clinical trial outcomes may be presented as a percentage slowing of decline, e.g., the drug slowed decline by x% at the 18-month endpoint compared to placebo. This type of relative measure is often reported as a primary outcome in abstracts, scientific lectures, and public presentations. Such a comparison may be attractive to clinicians and investors because it implies a slower disease progression rate for the active treatment compared to placebo.

However, relative change can be misleading, and cannot be used alone for assessing outcomes and effectiveness. Here we also consider standard statistical metrics: (1) The mean difference between treatments, (2) The standardized effect size (ES), relative outcomes, and their relationships to number needed to treat (NNT) and area under the receiver operator characteristics curve (AUC), a measure of group separation. We also discuss the need to express outcomes as standardized effects, as well as consider the minimum clinically important difference (MCID) between treatment and control in order to make inferences about effectiveness.

A key reason that percent difference is not informative is that it is a relative measure from which a magnitude of effect cannot be determined. For example, a 20% less decline at the endpoint could mean scores of 40 versus 50 for placebo with an absolute difference of 10; or mean scores of 8 vs. 10, with a difference of 2. Relative change cannot take into account the magnitude or variance of the outcome measures as would a widely established statistic (e.g., t-test, F test, beta coefficient) or a standardized effect size. Standardized effect sizes express an effect such as a mean difference in terms of its variance. Examples include Cohen’s d, Hedges’ g, and z scores, all of which take variance into account. Using percent difference as a clinical outcome does not contribute to clinical meaningfulness because for a given percent difference the magnitude of the difference could range from very small or very large.

We examine the implications of this failure by using a comparative graphic for clarification. We go on to demonstrate that effect size is an important determinant of NNT, a key clinical metric for understanding treatment effects, because of its association with group overlap. Last, we compile and table results from three recent anti-amyloid antibody trials in prodromal AD, showing percent slowing of decline, mean differences, and the unreported ESs and NNTs from these trials.

METHODS

The percent slowing of decline at endpoint is defined as 100*(1-(Average Decline in Treatment Group)/ (Average Decline in Placebo)) The formula describes a unitless relationship of the difference between groups standardized against the pooled SD using the formula: Cohen's , where M=mean and sd =standard deviation of the groups. Cohen’s d assumes a normal distribution and equal variances in the groups [1].

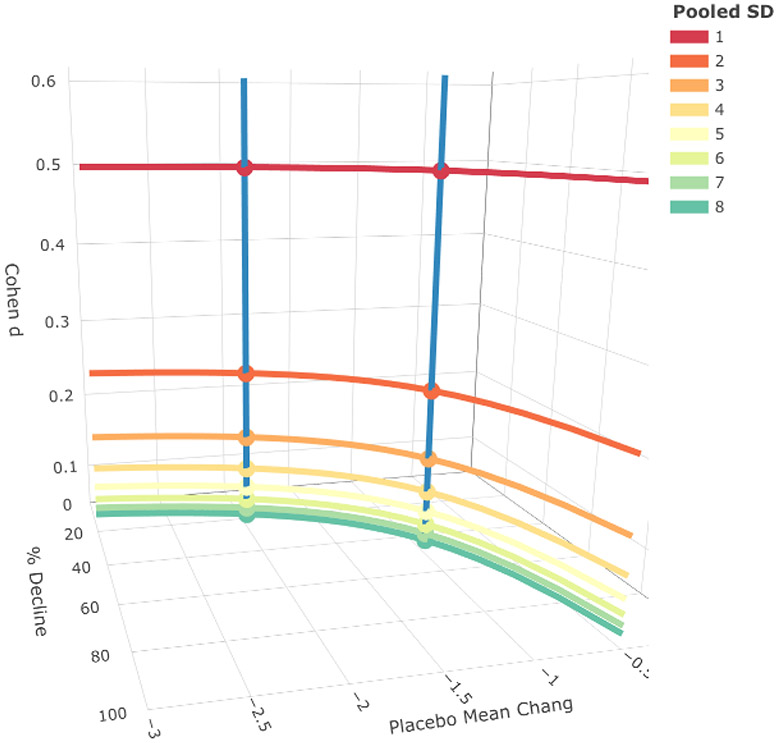

We generated a graphic to illustrate the inter-relationships among percent slowing of decline, Cohen’s d, placebo decline in raw score units, and pooled standard deviation. The difference between the treatment and placebo groups was fixed at 0.5. We computed the percent slowing of decline and Cohen’s d given placebo decline in raw score units, ranging from −0.5 to −2.0, and pooled standard deviation ranging from 1 to 8.

Number Needed to Treat (NNT) is the number of individuals that require active treatment to have one more successful outcome or to prevent one more adverse outcome compared to the control condition. In the context of current clinical trials in dementia an advantageous outcome is lack of decline. We calculated NNT with an established approach developed by Furukawa and that takes both Cohen’s d and an estimated event rate for an advantageous outcome in the placebo group into account, using the formula provided in [2,3] : , where , , and .

We estimated NNT using a placebo event rate of 0.20, 0.35 (frequently viewed as the frequency of placebo response rate in a wide variety of psychiatric and neurologic conditions), and 0.68 in the placebo group across a wide range of d’s. The latter value was based on the Kaplan-Meier curve presented for the CLARITY-AD trial for lecanemab that showed that approximately 68% of patients in the placebo group did not decline by 0.5 or more points on the CDR over the 18-month trial (i.e., had an advantageous outcome [4] We determined NNT using a web-based application [5].

We also determined the NNT developed for continuous data: NNT=1/2AUC-1 [6]. This formula is dependent on AUC, a measure of group separation derived from the receiver operating characteristic curve, and not on response rate. AUC represents the probability that an individual selected at random in the active treatment group has a better score (i.e., less decline) than an individual selected at random from the control group. It can be derived from d using the following formula: where d is Cohen’s d statistic and .

Comparisons of Percent Slowing, d, and NNT in Four Recent Clinical Trials

We computed respective ESs and NNTs from three recent amyloid anti-body secondary prevention trials: The aducanamab and lecanemab trials that resulted in accelerated FDA approvals for these biologics, and a phase 3 trial of donanemab [4,7,8] will likely receive FDA approval.

These latter three studies reported estimates of the regression models without relevant statistics (e.g., t-statistics or F-statistics with a degree of freedom) and standardized effect sizes such as Cohen's d, partial eta-squared, and/or Cohen's f2. Thus, based on the reported information and the statistical analysis models, we estimated the range of the degrees of freedom using the Kenward-Roger approximation and Satterthwaite's method. Since the variance of the follow-ups was not reported, we simulated datasets using the reported model estimates for the parameters (i.e., changes in the placebo group and changes in the treatment group, standard deviation at baseline); the residuals' standard deviation at the follow-up varied from 0.25 to 1. To be conservative, we only simulated the dataset including baseline and final time points, while the reported analyses included all intermediate time points, which would increase the degree of freedom, resulting in smaller effect sizes. Thus, we emphasize that the estimated range of Cohen's d we derived is possibly larger than the direct estimates of the model and hence is liberal. Given the t-statistics we estimated, we converted these to Cohen's d using the following conversion formula: Cohen's d=2t/sqrt(df). We then derived the mean of the range of Cohen’s d’s.

To provide context, we also included a large recent multimodal lifestyle intervention trial, FINGER, that reported percent slowing of decline [9]. The FINGER trial reported d using a modified ITT analyses with df specified. Our method yielded near identical results to that in the publication.

For NNTs we used the d for each trial and assumed a response rate of .68 or .66 in the placebo group for the three anti-amyloid trials (see above) as their AD samples, which included MCI with positive biomarkers for AD or mild AD, were similar at baseline.

The study conforms to SQUIRE guidelines [10].

RESULTS

Percent Slowing of Decline

Figure 1 shows the mean difference between treatment and placebo groups fixed at −0.5 in keeping with observed CDR-SB differences. Placebo decline varied from −0.5 to −3 points, and pooled SD from 1 to 8 in whole numbers. These SDs generate a wide range of Cohen’s d’s from 0.5 to 0.06. We graphically display along three dimensions the results for d (dependent on pooled SD), percent slowing of decline (based on the formula in the Methods), and placebo mean change from baseline. For any given d, percent slowing of decline can vary widely based on the magnitude of placebo decline, and the two measures are largely independent of each other.

Figure 1.

The figure has 3 axes: Cohen’s d, percent slowing of decline, and placebo change in raw scores. For any given d (curved lines) holding the difference between groups constant and varying the pooled SDs, yielded a wide range of percent slowing values. Two examples make this clear. For 25 percent slowing of decline (and a placebo change of 2 units) multiple Cohens d exist as shown in the blue vertical line. See also the second blue line representing a 50 percent slowing of decline. Conversely, for a given Cohen’s d=.25, percent slowing of decline can range from 0 to near 100 percent, as based on placebo change in raw scores.

Number Needed to Treat (NNT)

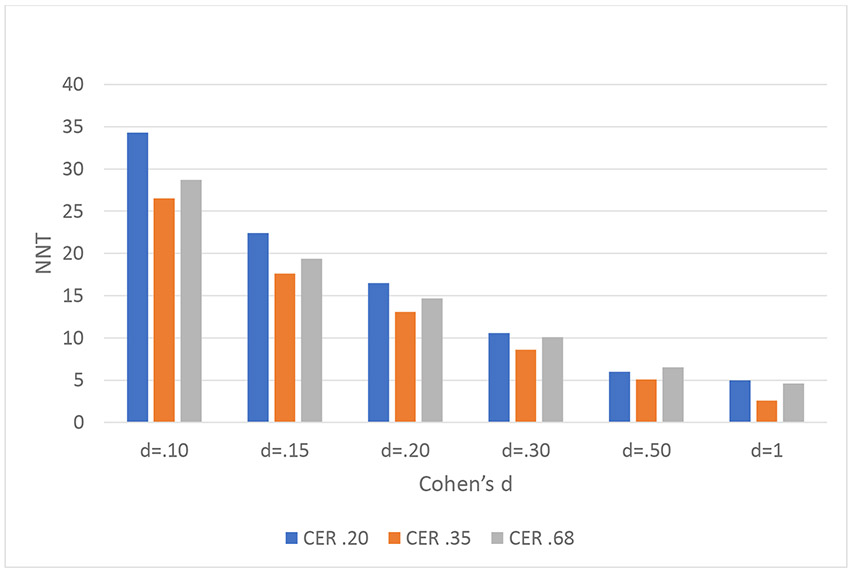

We show NNT across a range of Cohen’s d’s from 0.10 to 1.0 and three placebo response rates (.20, .35, .68) in Figure 2. It can be observed that the smaller the d, the larger the NNT for any given placebo response rate.

Figure 2.

NNTs examined as a function of Cohen’s d and event rate in the placebo group. Here we examined NNT at multiple d’s and event rates. CER (control event rate, i.e., response rate in the placebo group) represents the proportion of advantageous outcomes in the placebo group. For any given CER, the larger the d, the smaller the NNT.

Results for an AUC-dependent formula demonstrate the same trend in Supplementary Figure 1. Larger d’s were associated with smaller NNTs. AUC is dependent on d because the latter has the property of identifying degree of group separation: larger d’s are uniformly associated with greater group separation as can be seen in Supplementary Figure 2.

Comparison of Results from Major Anti-amyloid Secondary Prevention Trials in MCI and AD

As shown in Table 1, the significance levels vary markedly among the FINGER trial and amyloid antibody trials with aducanumab (EMERGE), donanemab (TRAILBLAZER ALZ2) and lecanemab (CLARITY). As expected, increased sample size was associated with greater significance. The Cohen’s d’s for CDR-SB, however, ranged from 0.16 to 0.23, all in the small to small medium ES range. The range of d, df’s, and t’s for these studies are in Supplementary Table 1. The NNTs ranged from 14 to 18 across these three studies. The FINGER trial was also associated with a small effect size (d=.13), but with a comparatively large percent slowing of decline.

Table 1.

Population Characteristics, Trial Methods, and Outcomes of Selected Recent AD Primary and Secondary Prevention Clinical Trials with Positive Results

| Study | Population | N treatment/ N control |

Duration (mo) |

Outcome | Difference vs control |

p | % Slowing | d | NNT3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FINGER | Cognitively unimpaired | 554/ 565 | 24 | NTB1 | 0.04 | .03 | 25 | 0.13 | # |

| Aducanumab EMERGE high dose | Early AD2 | 547/ 548 | 18 | CDR-SB | −0.39 | .01 | 22 | 0.16 | 18 |

| Donanemab TRAILBLAZER-ALZ 2 combined group | Early AD2 | 794/838 | 18 | CDR-SB | −0.70 | >..001 | 29 | 0.23 | 14 |

| Lecanemab CLARITY | Early AD2 | 898/ 897 | 18 | CDR-SB | −0.45 | .0005 | 27 | 0.21 | 15 |

Neuropsychological Test Battery reported in z score units

Early AD = prodromal AD and mild AD dementia

Number-needed-to-treat

unknown response rate

DISCUSSION

We have shown that percent difference in decline and ES can be independent using graphic derivations. Indeed, d and percent slowing of decline values were uncorrelated in the four trials that we examined in Table 1. Thus, the same percent difference in decline value may be associated with a wide range of ESs and conversely, the same ES can be associated with a wide range of percent slowing of decline. This is because percent slowing does not take into account the variances of the treatment and control groups nor their pooled SD. Indeed, the magnitude of placebo decline can be a critical determinant of the difference in percent slowing of decline. We go on to show that a standardized ES is more meaningful clinically because it directly influences NNT computations along with response rates. NNT cannot be derived from percent slowing of decline. Larger d’s were associated uniformly with smaller NNTs, as depicted in Figure 2.. Supplementary Figure 2 using an AUC-based formula demonstrated the same trend. Irrespective of whether formulae for deriving NNT are from continuous variables that include (or do not include) response rates, the basic trend is clear: the larger the d, the less group overlap and larger the AUC, the smaller the NNT. NNT is a clinically important measure and the figure and table show that effect size is key for determining NNT.

With respect to real-world clinical trial examples, the small ESs and large NNTs in three completed anti-amyloid secondary prevention trials considered to be “positive” for drug versus placebo raise questions about the clinical meaningfulness of these treatments for older adults with MCI or AD. In these trials, all d’s were below .24 and NNTs 14 or above, despite seemingly encouraging slowing of decline greater than 22% compared to placebo. These results, as well as multiple earlier negative anti-amyloid trials, have led some investigators to question amyloid as a target or single target [11].

We emphasized that ES is more informative than percent difference in decline as a metric. Another metric that we did not discuss is also relevant, namely minimum clinically important difference (MCID) in which : the magnitude of changes in cognition and function are meaningful, relevant, and observable to clinicians, patients, and/or caregivers. While it is often reported in the health science literature that d’s between .35 and .50 will be associated with clinically relevant change [12,13], there is a lack of consensus in the field on what constitutes an MCID for various measures of cognition when treated as a change in raw values for cognition and function and how it should be applied (e.g., at the group level and/or individual level where the proportions of advantageous MCID case outcomes could be contrasted between the active and placebo groups). Liu et al [14] showed that recent findings in clinical trials, including use of anti-amyloid antibodies, that demonstrated significant group differences did not approach the threshold necessary for potentially clinically relevant difference. For example for CDR-SBs, the MCID was found to be .98 for prodromal AD and thus current effects in anti-amyloid trials would not be “difference makers” to patients or caregivers [14,15]. Nevertheless, it should be acknowledged that there are no consensus metrics for an acceptable MCID for commonly used measures in AD trials despite suggestions from several groups [15-18]. This is why we propose ES and NNT as essential and MCID, if established, as added validation of a therapeutic effect.

Further consideration of NNTs in the anti-amyloid trials is also warranted. An NNT of 14 as found in the donanemab trial indicates that in a hypothetical population of 1000 treated individuals, 71 will have more favorable outcomes than those in a placebo group of 1000. Thus, 929 individuals will have had exposure to the drug with benefits no greater than that observed in the placebo group’s individuals. They would also be subject to any adverse events associated with the drug (e.g., ARIA) and the potential financial duress imposed by treatment costs.

There have also been proposals to use other relative metrics, including percent slowing based on individual cases or a metric involving delay in progression in units of time (“time saved from decline”). However, these suffer from the same problem as percent slowing in that they do not account for variance.

Another implication of our work is that trials for early AD are planned to detect small ESs differences between treatment and control, and this contributes to the frequency of uncertain outcomes and apparent “trends” in outcomes. These can result in failures to replicate, as with the phase 3 aducanumab, solanezumab, and gantenerumab trials, with outcomes less than the lower limits of clinician or observer resolution. Moreover, as they are planned (powered) for small effect sizes they also require large sample sizes, and allow for few dropouts and implicitly recognize that only a small minority of participants will likely benefit.

Statistical significance alone is insufficient to indicate that an intervention makes a clinically meaningful difference as the p-value is largely a function of sample size and reflects only the likelihood that the distributions of the outcomes is not attributable to random chance, i.e., a p-value is not a measure of ES. For instance, the lecanemab CLARITY trial had very small p-values, generated by a large N (approximately 900 each in the treatment and placebo group), as its Cohen’s d was similar to the other trials. Indeed, any effect larger than null (i.e., zero) effect can be demonstrated to be statistically significant with a large enough sample size. One potential “medico-sociologic” criticism of our study is the concern that patients “need something” and the pharmaceutical industry needs incentives to continue work in this disease. We take issue with this position because of the aforementioned small treatment effect sizes, unknown long term outcomes, and serious adverse event rates, though we appreciate that there is merit in this view as some individuals may experience large positive outcomes [18].

Investigators may also say that the study met its specified endpoint at p<.05 without consideration of effect size and NNT, which are clinically meaningful metrics. But if use of relative statistics (i.e., differences in percent decline between groups) masks an otherwise trivial effect size, does not lead to clinically meaningful functional gains, exposes people to unfavorable side effects, and at the societal level has large economic costs, the results can be misleading to patients and clinicians and lead to general frustration with implementation of new treatments approved by regulatory authorities [20, 21]. We have focused on efficacy only but recognize that the risk of adverse effects such as amyloid-related imaging abnormalities and cerebral volumetric changes may further lower the benefit to risk ratio for new treatments.

Summary and Recommendations for Quality Improvement.

Parametric statistics are conducted on mean differences, accounting for variance. Statistical power analyses take into account both mean differences and variance using ES. These traditional, well-established statistical measures are not conducted on percent slowing of decline. In this paper we demonstrated through derivations, real world examples, and thought experiments that the use of percent difference in decline can be largely unrelated to effect size. ES directly influences NNT and is therefore a more informative metric with respect to clinical meaningfulness. We propose that greater use of standardized ESs, less or no use of percent differences in decline, and use of NNTs, as well as determining consensus MCIDs when they become well-defined, will improve the field’s interpretation of clinical trial results and clinical meaningfulness for patients who are affected by these disabling cognitive disorders.

Supplementary Material

KEY MESSAGE.

What is already known on this topic:

Percent slowing of decline has become a widely used metric in describing the results of Alzheimer’s disease clinical trials, including those related to anti-amyloid immunotherapies.

What this study adds:

However, percent slowing can be largely independent of a standardized effect size, such as Cohen’s d. Recent trials have claimed seemingly impressive percent slowings in the range of 22 to 29%, but d’s have been small and under .24 and numbers-needed-to treat (NNT) have ranged from 14 to 18. D is the more informative metric because it directly indicates group separation, number-need-to-treat, and clinically important differences.

How this study might affect research, practice, or policy:

We propose that greater use of standardized effect sizes, less or no use of percent differences in decline, and use of NNTs, as well as determining consensus minimum clinically important differences when they become well-defined, will improve the field’s interpretation of clinical trial results and clinical meaningfulness for patients who are affected by these disabling cognitive disorders.

Funding

This work was funded by the following National Institute on Aging grants: P30AG066530, R01AG051346, R01AG052440, R01AG055422, R01AG062578, and R01AG062687

Footnotes

Competing Interests Disclosure

Dr. Lon S. Schneider reports personal fees from AC Immune, Alpha-cognition, Athira, Corium, Cortexyme, BioVie, Eli Lilly, GW Research, Lundbeck, Merck, Neurim, Ltd, Novo-Nordisk, Otsuka, Roche/Genentech. Cognition Therapeutics, Takeda; grants from Biohaven, Biogen, Eisai, Eli Lilly, Novartis. Dr. Devanand reports research support from the National Institute on Aging, Alzheimer’s Association, is a scientific adviser to Acadia, TauRx, Corium, Genentech, and is a member of the Data and Safety Monitoring Board of BioXcel. Dr. Goldberg and Dr. Lee have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Furukawa TA. From effect size into number needed to treat. Lancet. 1999;353(9165):1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Furukawa TA, Leucht S. How to obtain NNT from Cohen's d: comparison of two methods. PLoS One. 2011;6(4):e19070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Dyck CH, Swanson CJ, Aisen P, Bateman RJ, Chen C, Gee M, et al. Lecanemab in Early Alzheimer's Disease. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(1):9–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Magnusson K. Interpreting Cohen’s d Effect Size: An interactive visualization R Psychologist 2022. [updated September 19, 2022. Available from: https://rpsychologist.com/cohend/. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kraemer HC, Kupfer DJ. Size of treatment effects and their importance to clinical research and practice. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59(11):990–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Budd Haeberlein S, Aisen PS, Barkhof F, Chalkias S, Chen T, Cohen S, et al. Two Randomized Phase 3 Studies of Aducanumab in Early Alzheimer's Disease. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2022;9(2):197–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mintun MA, Wessels AM, Sims JR. Donanemab in Early Alzheimer's Disease. Reply. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(7):667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ngandu T, Lehtisalo J, Solomon A, Levalahti E, Ahtiluoto S, Antikainen R, et al. A 2 year multidomain intervention of diet, exercise, cognitive training, and vascular risk monitoring versus control to prevent cognitive decline in at-risk elderly people (FINGER): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;385(9984):2255–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ogrinc G, Davies L, Goodman D, Batalden P, Davidoff F, Stevens D. SQUIRE 2.0 (Standards for QUality Improvement Reporting Excellence): revised publication guidelines from a detailed consensus process. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25(12):986–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kumar A, Nemeroff CB, Cooper JJ, Widge A, Rodriguez C, Carpenter L, et al. Amyloid and Tau in Alzheimer's Disease: Biomarkers or Molecular Targets for Therapy? Are We Shooting the Messenger? Am J Psychiatry. 2021;178(11):1014–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farivar SS, Liu H, Hays RD. Half standard deviation estimate of the minimally important difference in HRQOL scores? Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2004;4(5):515–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Norman GR, Sloan JA, Wyrwich KW. The truly remarkable universality of half a standard deviation: confirmation through another look. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2004;4(5):581–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu KY, Schneider LS, Howard R. The need to show minimum clinically important differences in Alzheimer's disease trials. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8(11):1013–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andrews JS, Desai U, Kirson NY, Zichlin ML, Ball DE, Matthews BR. Disease severity and minimal clinically important differences in clinical outcome assessments for Alzheimer's disease clinical trials. Alzheimers Dement (N Y). 2019;5:354–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lansdall CJ, McDougall F, Butler LM, Delmar P, Pross N, Qin S, et al. Establishing Clinically Meaningful Change on Outcome Assessments Frequently Used in Trials of Mild Cognitive Impairment Due to Alzheimer's Disease. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2023;10(1):9–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schrag A, Schott JM, Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging I. What is the clinically relevant change on the ADAS-Cog? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2012;83(2):171–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Petersen RC, Aisen PS, Andrews JS, Atri A, Matthews BR, Rentz DM, et al. Expectations and clinical meaningfulness of randomized controlled trials. Alzheimers Dement. 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matthay EC, et al. , Powering population health research: Considerations for plausible and actionable effect sizes. SSM - Population Health, 2021. 14: p. 100789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knopman DS, Jones DT, Greicius MD. Failure to demonstrate efficacy of aducanumab: An analysis of the EMERGE and ENGAGE trials as reported by Biogen, December 2019. Alzheimers Dement. 2021;17(4):696–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schneider LS. Editorial: Aducanumab Trials EMERGE But Don't ENGAGE. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2022;9(2):193–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.