Abstract

Background

Amitriptyline is a tricyclic antidepressant that was synthesised in 1960 and introduced as early as 1961 in the USA, but is still regularly used. It has also been frequently used as an active comparator in trials on newer antidepressants and can therefore be called a 'benchmark' antidepressant. However, its efficacy and safety compared to placebo in the treatment of major depression has not been assessed in a systematic review and meta‐analysis.

Objectives

To assess the effects of amitriptyline compared to placebo or no treatment for major depressive disorder in adults.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis Group's Specialised Register (CCDANCTR‐Studies and CCDANCTR‐References) to August 2012. This register contains relevant randomised controlled trials from: The Cochrane Library (all years), EMBASE (1974 to date), MEDLINE (1950 to date) and PsycINFO (1967 to date). The reference lists of reports of all included studies were screened and manufacturers of amitriptyline contacted for details of additional studies.

Selection criteria

All randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing amitriptyline with placebo or no treatment in patients with major depressive disorder as diagnosed by operationalised criteria.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently extracted data. For dichotomous data, we calculated the odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). We analysed continuous data using standardised mean differences (with 95% CI). We used a random‐effects model throughout.

Main results

The review includes 39 trials with a total of 3509 participants. Study duration ranged between three and 12 weeks. Amitriptyline was significantly more effective than placebo in achieving acute response (18 RCTs, n = 1987, OR 2.67, 95% CI 2.21 to 3.23). Significantly fewer participants allocated to amitriptyline than to placebo withdrew from trials due to inefficacy of treatment (19 RCTs, n = 2017, OR 0.20, 95% CI 0.14 to 0.28), but more amitriptyline‐treated participants withdrew due to side effects (19 RCTs, n = 2174, OR 4.15, 95% CI 2.71 to 6.35). Amitriptyline also caused more anticholinergic side effects, tachycardia, dizziness, nervousness, sedation, tremor, dyspepsia, sedation, sexual dysfunction and weight gain. In subgroup and meta‐regression analyses the results of the primary outcome were robust towards publication year (1971 to 1997), mean participant age at baseline, mean amitriptyline dose, study duration in weeks, pharmaceutical sponsor, inpatient versus outpatient setting and two‐arm versus three‐arm design. However, higher severity at baseline was associated with higher superiority of amitriptyline (P = 0.02), while higher responder rates in the placebo groups were associated with lower superiority of amitriptyline (P = 0.05). The results of the primary outcome were rather homogeneous, reflecting comparability of the trials. However, methods of randomisation, allocation concealment and blinding were usually poorly reported. Not all studies used intention‐to‐treat analyses and in many of them standard deviations were not reported and often had to be imputed. Funnel plots suggested a possible publication bias, but the trim and fill method did not change the overall effect size much (seven adjusted studies, OR 2.64, 95% CI 2.24 to 3.10).

Authors' conclusions

Amitriptyline is an efficacious antidepressant drug. It is, however, also associated with a number of side effects. Degree of placebo response and severity of depression at baseline may moderate drug‐placebo efficacy differences.

Keywords: Adult; Humans; Amitriptyline; Amitriptyline/therapeutic use; Antidepressive Agents, Tricyclic; Antidepressive Agents, Tricyclic/therapeutic use; Depressive Disorder, Major; Depressive Disorder, Major/drug therapy; Placebo Effect; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

Amitriptyline for the treatment of depression

Amitriptyline is a tricyclic antidepressant drug that has been used for decades in the treatment of depression. The current review includes 39 trials with a total of 3509 participants and confirms its efficacy compared to placebo or no treatment. This finding is important, because the efficacy of antidepressants has recently been questioned. However, the review also demonstrated that amitriptyline produces a number of side effects such as vision problems, constipation and sedation. It is a limitation of this review that many studies have been poorly reported, which might have led to bias.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Amitriptyline versus placebo for major depressive disorder.

| Amitriptyline versus placebo for major depressive disorder | ||||||

| Patient or population: adults with major depressive disorder Settings: inpatients and outpatients Intervention: amitriptyline | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Amitriptyline | |||||

| Response to treatment At least 50% reduction of a depression scale (mainly Hamilton Depression Rating Scale) Follow‐up: 3 to 12 weeks | 313 per 1000 | 546 per 1000 (509 to 582) | OR 2.64 (2.28 to 3.06) | 3228 (31 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1,2 | |

| Death due to suicide | See comment | See comment | Not estimable3 | ‐ | See comment | No study reported on this outcome |

| Quality of life | See comment | See comment | Not estimable3 | ‐ | See comment | No study reported on this outcome |

| Acceptability of treatment Drop‐out for any reason Follow‐up: 3 to 12 weeks | 403 per 1000 | 324 per 1000 (271 to 386) | OR 0.71 (0.55 to 0.93) | 2400 (24 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,4,5 | |

| Overall tolerability Drop‐out due to adverse events Follow‐up: 3 to 12 weeks | 45 per 1000 | 165 per 1000 (114 to 232) | OR 4.15 (2.71 to 6.35) | 2174 (19 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 The randomisation and allocation methods were usually unclear. Drop‐outs were often not clearly described. 2 There was a possibility of publication bias, but according to the trim and fill method the suspected missing studies would not have changed the overall effect size much. 3 Not a single study reported on this outcome. 4 There was moderate heterogeneity (I² = 48%). Some studies showed superiority of amitriptyline and others of placebo. 5 Acceptability of treatment was measured indirectly by the number of participants leaving the studies prematurely.

Background

Description of the condition

Major depressive disorder is a common condition with a lifetime prevalence of 15% to 18% (Berger 2004). Its main symptoms are a depressed mood and lack of interest or pleasure in activities. These are often accompanied by a range of other problems including fatigue, loss of appetite and weight, poor concentration, decreased libido, sleep problems, inappropriate guilt feelings and suicidal ideation. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that depression affects about 121 million people in the world (WHO 2005). Some authors describe a lower prevalence of major depression, according to the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders by the American Psychiatric Association (DSM‐IV), in Japan (lifetime prevalence 3% to 7%) compared to Western countries, suggesting that the prevalence of major depression might be lower in Asian countries (Kawakami 2007), but this is controversial. However, by the year 2020 depression could become the most common disease after cardiovascular diseases worldwide (Gayetot 2007). The degree of disability and suffering of those with depression can be dramatic. For example, in the year 2005, people with unipolar depressive disorders were placed second in terms of disability adjusted life years (DALY) in Germany (WHO 2005). Suicide rates are clearly higher in those with major depression than in the general population (Berger 2004).

Description of the intervention

Various psychotherapeutic and psychopharmacological interventions are available for the treatment of major depressive disorder. Among the psychological therapies, the efficacy of cognitive behavioural interventions is probably the best examined (Cuijpers 2010; Gloaguen 1998). The mainstay of pharmacological treatment are the various classes of antidepressants.

The first tricyclic antidepressant (TCA) was imipramine, introduced in 1955. Various other TCAs and monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) followed soon after. Amitriptyline, the antidepressant examined in this review, is a TCA that was already in use in 1961 and is still frequently used nowadays. As an example, with 94 million defined daily doses (DDD) it was still the third most frequently prescribed antidepressant in Germany after citalopram (209 DDD) and mirtazapine (107 DDD) in 2008 (Lohse 2009). Amitriptyline also offers a large variability in dosing, often ranging between 25 mg and 150 mg, but sometimes even less or more. A typical adult dose for inpatients is 150 mg daily. The drug is associated with a number of side effects such as blurred vision, constipation, urination problems, dry mouth, delirium, vertigo and sedation. Overdoses can be life‐threatening due to cardiac arrhythmias and other factors. Indeed, fatal toxicities have been shown to be more frequent under tricyclic antidepressants than under newer antidepressants such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) (Henry 1995). Apart from the treatment of major depressive disorder, amitriptyline is also used in the treatment of other forms of depression, chronic pain, migraine and anxiety disorders, although for many of the latter it does not have an official indication.

In the last three decades the TCAs have been partly replaced by newer agents, especially selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) but also selective noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors or selective serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors. The main advantage of the SSRIs is their better overall tolerability compared to TCAs (Barbui 2000). However, there is debate as to whether TCAs such as amitriptyline may be more efficacious than SSRIs, in particular in more severely ill inpatients (Guaiana 2007).

How the intervention might work

One of the hypotheses for the aetiology of depression is dysfunction of the monoamine system, including the neurotransmitters serotonin and norepinephrine. Amitriptyline increases the concentrations of these neurotransmitters in the synaptic cleft by inhibiting their reuptake into the presynaptic neuron. The reuptake inhibition is achieved by blocking the noradrenaline and serotonin transporters. Amitriptyline has a relatively similar affinity for these two receptors whereas clomipramine, for example, has a far greater affinity for the serotonin relative to the noradrenaline transporter or desipramine and nortriptyline for which the reverse applies.

Amitriptyline, however, also functions as an antagonist at various other neuroreceptors such as histamine H1 receptors, muscarinic cholinoreceptors, alpha 1 adrenoreceptors and 5‐HT2a receptors, which may serve as links to its putative side effects.

Why it is important to do this review

In many countries amitriptyline is still a frequently used antidepressant. For example, in 2008 it was the third most frequently prescribed antidepressant in Germany (94 million DDDs) (Lohse 2009). In the UK, approximately 13 people per 1000 were prescribed amitriptyline for depression in 2010 according to a large primary care‐based prescription database (GPRD 2011) ) (please note this is based on an estimate only as the GPRD does not record the indication for which the drug was prescribed). Therefore it is important to define its efficacy and safety compared to placebo. Furthermore, recent reviews have found only small differences between new antidepressants and placebo, putting into question the efficacy of antidepressants in general. For example, Barbui 2008 compared the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor paroxetine with placebo and the absolute difference in responder rates was only 10% (53% responded to drug versus 42% to placebo, N = 22 trials, n = 5222 participants; risk difference 10%, 95% confidence interval (CI) 7% to 13%; response ratio 1.2, 95% CI 1.2 to 1.3) and the effect size was only 0.31 (95% CI 0.22 to 0.40). Turner 2008 showed that the effect sizes of new antidepressants are smaller if unpublished trials are included. Kirsch 2008 concluded from their systematic review that new antidepressants should only be used in the most severely ill patients and not in mild forms of depression for which they are frequently prescribed, although the methodology of the review has been criticised by other researchers (McAllister‐Williams 2008). However, all these analyses were derived from studies on newer antidepressants. To the best of our knowledge a methodologically sound systematic review comparing the effects of the classical antidepressant amitriptyline with placebo is not available. The results of this review can be an important contribution to the present polarised debate. This review also adds to the portfolio of Cochrane reviews on antidepressants for depression. In particular, it augments the information available on amitriptyline, for which a systematic review comparing it with other antidepressants is already available (Guaiana 2007). The results will also be used in a network meta‐analysis on antidepressants currently being conducted by members of the Cochrane Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis Group.

Objectives

To assess the effects of amitriptyline compared to placebo or no treatment for major depressive disorder in adults.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials. We only included studies with adequate randomisation (for example computer‐generated randomisation lists) and allocation (for example allocation by an independent person in the hospital pharmacy) procedures, or if the details of randomisation and allocation were unclear, as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2008). We excluded quasi‐randomised studies such as those using allocation by day of the week, date of birth or alternate allocation due to the evidence of a strong relationship between allocation concealment and direction of effect (Schulz 1995).

There was no minimum duration of the included studies, and there was no upper limit of the duration as long as the participants were initially acutely ill.

There was no language restriction, in order to avoid the problem of ‘language bias’ (Egger 1997).

Only the first phases of cross‐over studies were used, to avoid carry‐over effects.

Types of participants

Adults aged 18 years or older with acute unipolar major depressive disorder according to any standardised diagnostic criteria such as the DSM‐IV, DSM‐III‐R, DSM‐III diagnostic codes 296.2 or 296.3 (APA 1980; APA 1987; APA 1994), WHO International Classification of Diseases (ICD) ICD‐10 (F32 or F33) (WHO 1992), ICD‐9 (WHO 1978), Research Diagnostic Criteria (Spitzer 1978) or Feighner criteria (Feighner 1972) were included.

There were no limits in terms of setting, gender or ethnicity and there was no upper age limit.

We included studies in which less than 20% of the participants were suffering from bipolar depression, dysthymia or neurotic depression. We also included participants with a concurrent secondary diagnosis of another psychiatric disorder. We included participants treated in primary care and specialty behavioural health or psychiatry as well as participants treated in inpatient and outpatient settings. We excluded studies in participants with no or only subclinical symptoms at baseline, which are usually conducted to address the relapse preventing effects of antidepressants. We excluded participants with a concurrent primary diagnosis of Axis I or II disorders and participants with a serious concomitant medical illness.

Types of interventions

The experimental treatment was amitriptyline: any dose, any oral mode of administration (tablets, capsules or liquid form).

The comparator substance was placebo, either active (an inert substance that mimics the side effects of amitriptyline) or inactive.

Treatment must have been given as monotherapy.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

The primary outcome was the number of patients who responded to treatment, defined as a reduction of at least 50% on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM‐D) (Hamilton 1960), the Montgomery‐Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) (Montgomery 1979) or any other depression scale, or 'much or very much improved' (score 1 or 2) on the Clinical Global Impression (CGI) Improvement Scale (Guy 1976). All response rates were calculated from the total number of randomised patients. Where more than one criterion was provided, we used the HAM‐D for judging the response and then followed the sequence described above. Despite the problems surrounding scale‐derived response cutoffs (Leucht 2007), dichotomous outcomes can be understood more intuitively by clinicians than the mean values of rating scales and are therefore preferred.

When studies reported response rates at various time points of the trial, we had decided a priori to subdivide the treatment indices as follows.

Early response, between one and five weeks; the time point closest to two weeks was given preference.

Acute phase treatment response, between six and 12 weeks; the time point given in the original study as the study endpoint was given preference.

Follow‐up response, between four and six months; the time point closest to 24 weeks was given preference.

The acute phase treatment response, that is between six and 12 weeks, was our primary outcome of interest.

Secondary outcomes

The number of participants in remission, as defined by either: (a) a score of 7 or less on the 17‐item HAM‐D and 8 or less for all the other longer versions of HAM‐D; (b) a score of 10 or less on the MADRS (Zimmerman 2004); (c) 'not ill or borderline mentally ill' (score 1 or 2) on the CGI‐Severity (Guy 1976); or (d) other criteria as defined by the trial authors. All remission rates were calculated out of the total number of randomised patients. Where two or more scales are provided, we preferred the first criteria for judging remission. ‘Remission’ is a state of relative absence of symptoms. This outcome added to the primary outcome ‘response’ to treatment. The disadvantage of 'remission' is that its frequency depends on the initial severity of the participants. If they were only relatively mildly ill, many will be classified as in remission while only few will be in the case of high average severity at baseline. Therefore, studies and meta‐analyses usually apply response and not remission as the primary outcome.

Change scores from baseline or endpoint score at the time point in question (early response, acute phase response or follow‐up response as defined above) on the HAM‐D or MADRS, or any other validated depression scale. The results of mean values of depression rating scales can be more sensitive than dichotomous response data. Therefore, they should also be presented even though their interpretation is less intuitive than with dichotomous response data. Change data were preferred to endpoint data but both had to be presented separately because we used the standardised mean difference as an effect size measure for which pooling of endpoint and change data is not appropriate (Higgins 2008, page 269). We preferred change scores to endpoint scores because they, to a certain extent, take into account small baseline imbalances.

Social adjustment, social functioning including the Global Assessment of Function scores (Luborsky 1962).

Health‐related quality of life as measured by validated disease‐specific and generic scales such as the Short Form (SF)‐36 (Ware 1993) or the Health of the Nation Outcome Scales (HoNOS) (Wing 1994).

-

Various reasons for dropping out of the studies:

due to any reason, as a measure of the overall acceptability of treatment

due to inefficacy of treatment, as a global efficacy measure

due to adverse events, as a global measure of tolerability

-

Death:

natural causes

suicide

suicide attempts

-

Side effects:

number of participants experiencing at least one side effect

agitation or anxiety

blurred vision

constipation

urination problems

delirium

diarrhoea

dry mouth

fits

insomnia

hypotension

nausea

sedation or somnolence

vomiting

vertigo

We anticipated including the following main outcomes in a 'Summary of findings' table using GRADEpro (Brozek 2008): response to treatment, acceptability of treatment (drop‐out due to any reason), quality of life, death due to suicide and overall tolerability (drop‐out due to adverse events).

Search methods for identification of studies

CCDAN's Specialised Register (CCDANCTR)

The Cochrane Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis Group (CCDAN) maintain two clinical trials registers at their editorial base in Bristol, UK, a references register and a studies‐based register. The CCDANCTR‐References Register contains over 30,000 reports of randomised controlled trials in depression, anxiety and neurosis. Approximately 65% of these references have been tagged to individual, coded trials. The coded trials are held in the CCDANCTR‐Studies Register and records are linked between the two registers through the use of unique Study ID tags. Coding of trials is based on the EU‐Psi coding manual. Please contact the CCDAN Trials Search Co‐ordinator for further details. Reports of trials for inclusion in the Group's registers are collated from routine (weekly), generic searches of MEDLINE (1950 ‐), EMBASE (1974 ‐) and PsycINFO (1967 ‐); quarterly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) and review‐specific searches of additional databases. Reports of trials are also sourced from international trials registers c/o the World Health Organization’s trials portal (ICTRP), drug companies, the handsearching of key journals, conference proceedings and other (non‐Cochrane) systematic reviews and meta‐analyses. Details of CCDAN's generic search strategies can be found on the Group‘s website.

Electronic searches

With the assistance of the Cochrane Collaboration Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis Group (CCDAN) Trials Search Co‐ordinator (TSC), we searched the Group's controlled trials registers (CCDANCTR‐References and CCDANCTR‐Studies) up to 30 August 2012 using the following terms:

((Depress* or Dysthymi* or "Adjustment Disorder*" or "Mood Disorder*" or "Affective Disorder*" or "Affective Symptoms") and amitriptylin* and placebo*)

We also searched the clinical trial databases ClinicalTrials.gov, the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number Register (ISRCTN) and the WHO Trials portal (ICTRP) with the term amitriptylin* (to 30 August 2012).

Searching other resources

Reference searching

We inspected the references of all identified studies for more trials.

Personal contact

We contacted the first author of each included study for any missing information on the included studies.

Drug companies

We contacted the major manufacturer of amitriptyline to ask about further relevant studies and for missing information on identified studies.

Handsearching

Appropriate journals and conference proceedings relating to amitriptyline treatment for depression have been handsearched and incorporated into the CCDAN databases.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently inspected all titles and abstracts identified by the searches. Disagreement was resolved by discussion and if necessary a third review author was involved. Where doubt still remained, we acquired the full article for further inspection. Once the full articles were obtained, at least two review authors independently decided whether the studies met the review criteria. If disagreement could not be resolved by discussion, and a third review author, we sought further information from the study authors.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors independently extracted data from all selected trials. When there was disagreement it was resolved by discussion with a third review author. When possible, we contacted the study authors to resolve any dilemma. We extracted data on standard, simple forms that were piloted using a random sample of 10 studies.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two authors independently assessed risk of bias using the tool described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2008). This tool encourages consideration of how the sequence was generated, how allocation was concealed, the integrity of blinding at outcome assessment, the completeness of outcome data, selective reporting and other biases. If the raters disagreed the final rating was made by consensus and with the involvement (if necessary) of a third member of the review group. We categorised each domain as high risk of bias, low risk of bias or unclear risk of bias.

Measures of treatment effect

1. Continuous data

As we expected that the studies would frequently use different scales to measure the same concept (for example either the HAM‐D or the MADRS to evaluate the overall degree of depression) the standardised mean difference (SMD) was the effect measure for continuous outcomes.

2.1 Change versus endpoint data

We used endpoint data only when change data were not available.

2.2 Skewed data

Continuous data on clinical and social outcomes are often not normally distributed. To avoid the pitfall of applying parametric tests to non‐parametric data, we applied the following standards to all data before inclusion.

(a) We entered data from studies of, for example, at least 200 participants in the analysis irrespective of the following rules, because skewed data pose less of a problem in large studies.

(b) Endpoint data: when a scale starts from the finite number zero, we subtracted the lowest possible value from the mean and divide this by the standard deviation. If this value is lower than one, it strongly suggests a skew and the study was excluded. If this ratio is higher than one but below two, there is suggestion of a skew. We entered the study and tested whether its inclusion or exclusion substantially changed the results. If the ratio was larger than two the study was included because skew is less likely (Altman 1996; Higgins 2008).

(c) When continuous data are presented on a scale which includes the possibility of negative values (such as change data), it is difficult to tell whether data are skewed or not. We planned to enter such studies because change data tend to be less skewed and because excluding studies would also lead to bias, because not all the available information would be used.

3. Binary data

We calculated the odds ratio (OR) and its 95% confidence interval (CI).

Unit of analysis issues

Cross‐over trials

For trials which had a cross‐over design we only considered results from the first randomisation period to avoid carry‐over effects (Elbourne 2002).

Cluster‐randomised trials

If we encountered cluster‐randomised trials we included them following the rules presented in the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins 2008).

Trials with multiple dose groups

Some studies might address the effects of different doses of amitriptyline compared to placebo. In the case of dichotomous outcomes we summed the sample sizes and the number of people with events across both groups. For continuous outcomes we combined means and standard deviations using the methods described in chapter 7 (section 7.7.3.8) of the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins 2008).

Dealing with missing data

1. Missing participants

Dichotomous data

We analysed all data on the basis of the intention‐to‐treat (ITT) principle: drop‐outs were always included in this analysis. Where participants were withdrawn from the trial before the endpoint, it was assumed that their condition remained unchanged if they had stayed in the trial. This is conservative for outcomes related to response to treatment (because these participants will be considered to have not responded to treatment). It is not conservative for adverse events but we think that for the adverse events of interest in our review (see outcomes) a worst‐case scenario is clinically unlikely. When there were missing data and the method of 'last observation carried forward' (LOCF) had been used to do an ITT analysis, then we used the LOCF data with due consideration of the potential bias and uncertainty introduced.

Continuous data

The Cochrane Handbook recommends avoiding imputations of continuous data and suggests rather that the data must be used in the form presented by the original authors. Whenever ITT data were presented by the authors they were preferred to ‘per protocol or completer’ data sets.

2. Missing data

We contacted the original study authors for missing data.

3. Missing statistics

When only the standard error (SE) or P values were reported, we calculated standard deviations (SDs) according to Altman (Altman 1996). In the absence of supplemental data after requests to the authors, we estimated the SDs from CI, t values or P values as described in Section 7.7.3 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2008); or imputed them according to a validated method (Furukawa 2006). We examined the validity of these imputations in a sensitivity analysis.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We started to assess heterogeneity by visual inspection of the forest plots. We also calculated I2 statistics and analysed them on the basis of the Cochrane Handbook recommendations (I2 values of 0% to 40%: might not be important; 30% to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity; 50% to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity; 75% to 100%: considerable heterogeneity). In addition to the I 2 statistic (Higgins 2003) we presented the Chi2 and its P value and considered the direction and magnitude of the treatment effects. As the Chi2 test is underpowered to detect heterogeneity in meta‐analyses with few studies, should it exist, we used a P value of 0.10 as a threshold of statistical significance.

Assessment of reporting biases

Reporting biases arise when the dissemination of research findings is influenced by the nature and direction of results. These biases are described in section 10.1 of the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins 2008). We investigated reporting bias by constructing funnel plots. We are aware that funnel plots may be useful in investigating reporting biases but are of limited power to detect small‐study effects. We did not use funnel plots for outcomes where there were 10 or fewer studies, or where all studies were of similar size.

Data synthesis

We employed the random‐effects model for all analyses (Der‐Simonian 1986). We understand that there is no closed argument for preference of either the fixed‐effect or random‐effects model. The random‐effects method incorporates an assumption that the different studies are estimating different yet related intervention effects. This does seem true for us as we a priori expected some clinical heterogeneity between the patients in the different trials. We examined, however, whether use of a fixed‐effect model led to a substantial difference in the primary outcome.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We explored potential causes of heterogeneity by performing subgroup analysis and random‐effects restricted maximum‐likelihood meta‐regression. We are aware that subgroup analyses are observational by nature and therefore considered the results to be exploratory and not explanatory. Nevertheless, we addressed the following a priori defined potential effect modifiers of the primary outcome.

Depression severity at baseline using the mean HAM‐D score at baseline as a moderator in a meta‐regression: because it is known that antidepressants are more efficacious in more severely ill patients (Kirsch 2008).

Mean age at baseline: the rationale was that drug pharmacokinetics and metabolism change with age.

Mean amitriptyline dose: in a secondary analysis of their work, Furukawa 2003 found that higher doses of tricyclic antidepressants might be somewhat more efficacious than lower doses.

Study duration, in weeks: to find out whether longer duration studies showed greater drug to placebo differences than shorter trials.

Percentage number of participants who responded to placebo: studies on selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors have shown that the degree of placebo response has increased in recent years and that this can limit drug to placebo differences (Walsh 2002). We explored whether this is also the case in the amitriptyline studies.

Publication year: old meta‐analyses (e.g. Davis 1993) found much bigger differences between antidepressants and placebo than recent systematic reviews (e.g. Barbui 2008). We explored whether this impression can be confirmed by statistical analysis.

Diagnostic system (subgroup analysis): we compared studies that used operationalised diagnostic criteria (DSM‐IV, DSM‐III‐R, DSM‐III, ICD‐10, Research Diagnostic Criteria, Feighner criteria) with studies using the non‐operationalised criteria ICD‐9. As participants diagnosed by the latter criteria might be quite different from those applying operationalised criteria, we planned to investigate this in a subgroup analysis.

Pharmaceutical sponsor (yes or no): pharmaceutical companies have an inevitable conflict of interest. Therefore, we compared the results of industry sponsored and non‐industry sponsored trials. As long as only medication was provided by a pharmaceutical company, such studies were not classified as primarily industry sponsored.

Two‐arm versus three‐arm studies (e.g. amitriptyline versus SSRI versus placebo): we carried out this subgroup analysis because early work suggested that the antidepressant‐placebo difference is smaller in three‐arm than in two‐arm studies (Greenberg 1992).

Inpatient versus outpatient studies: Barbui 2004 found that amitriptyline might be more efficacious than SSRIs in inpatients, while there was no difference in outpatients. This subgroup analysis therefore explored whether this was also the case when amitriptyline was compared with placebo.

Sensitivity analysis

The following sensitivity analyses of the primary outcome were planned.

Exclusion of non‐double‐blind studies.

Fixed‐effect instead of random‐effects model.

Exclusion of studies using imputed statistics.

Exclusion of cluster‐randomised trials.

Exclusion of cross‐over trials.

Exclusion of studies that used ICD‐9 for the diagnostic criteria.

Results

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies.

Results of the search

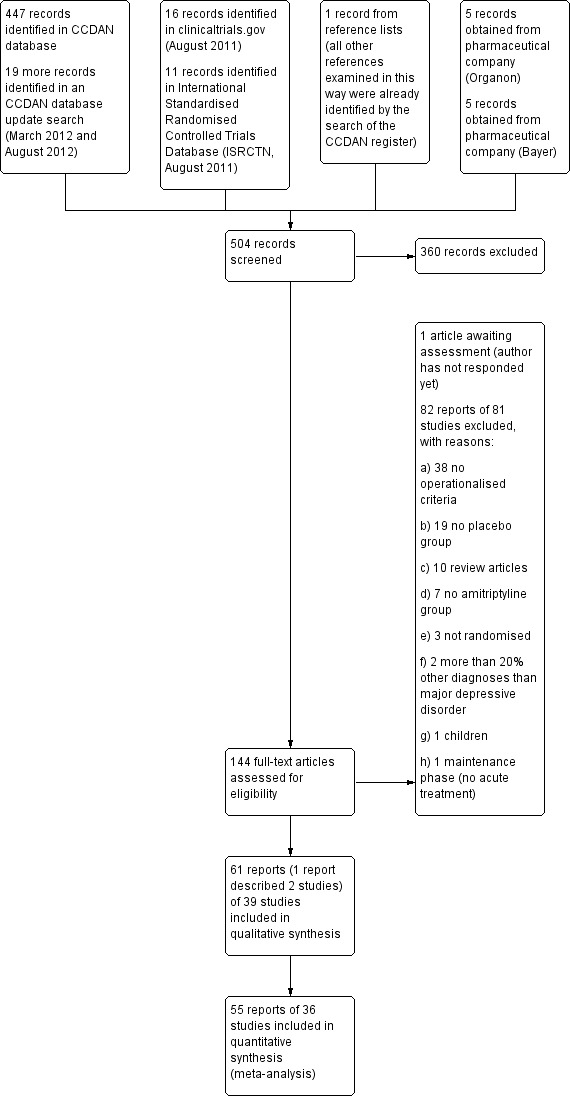

A PRISMA diagram is presented in Figure 1. The electronic search in September 2010 and the update search in August 2012 yielded 466 potentially relevant references; 27 were identified in clinicaltrials.gov or ISRCTN, one by cross‐referencing and 10 records were sent by two pharmaceutical companies (five by each company). In total we screened 504 reports; we excluded 360 reports on the basis of the abstract. We inspected in detail but finally excluded 82 full reports on 81 studies (for reasons see below). Sixty reports on 39 RCTs with a total of 3509 participants met the inclusion criteria and 36 RCTs provided data for at least one outcome. One study is awaiting assessment.

1.

Study flow diagram.

We contacted all first authors and seven authors replied; two of them provided us with additional information. We also contacted pharmaceutical companies manufacturing amitriptyline: two companies replied, one company (Organon) provided us with additional information of already published studies as well as data from two unpublished trials.

Included studies

Design

Length of treatment

In 17 studies the randomised phase was six weeks (Bhatia 1991; Bremner 1995; Carman 1991; Gelenberg 1990; Hicks 1988; Jacobson 1990; Kusalic 1993; Organon 3‐020 unpublished; Organon 84062 unpublished; Paykel 1988a; Preskorn 1983; Rickels 1982; Rickels 1985; Rowan 1980; Smith 1990; Stratas 1984; Wilcox 1994) and in 13 studies the randomised phase lasted four weeks (Amsterdam 1986; Blashki 1971; Claghorn 1983; Feighner 1979; Georgotas 1982; Hormazabal 1985; Katz 1993; Katz 1993a; Kupfer 1979; Langlois 1985; Shipley 1981; Roffman 1982; van de Merwe 1984a). There were respectively two studies with a duration of three weeks (Klieser 1988; McNair 1984a), five weeks (Hoschl 1989; Raft 1981), eight weeks (Lydiard 1997; Reimherr 1990) and 12 weeks (Mynors‐Wallis 1995; Thomson 1982). One study lasted seven weeks (Bakish 1992).

Sample size

The mean number of participants per study was 92.2 (SD 76.5), with a minimum sample size of 12 (van de Merwe 1984a) and a maximum of 299 (Reimherr 1990). In one study the number of participants was not reported (Preskorn 1983).

Cluster/cross‐over design

There was only one study with a cross‐over design (McNair 1984a), but the description of the first treatment phase did not provide any usable data. There was no cluster‐randomised trial.

Participants

Age

Overall the mean age was 40.06 years (SD 2.96); the mean age was provided in 27 studies. Of these 27 trials, six trials provided information only for the mean age of all arms. Regarding the other 12 trials, two provided only the age range which was 17 to 73 and 21 to 65, respectively, and 10 trials did not provide any relevant information. In six studies patients over 65 years could have been included (Amsterdam 1986; Blashki 1971; Bremner 1995; Katz 1993a; Preskorn 1983; Roffman 1982).

Diagnosis

All studies enrolled patients suffering from major depression, 20 according to DSM‐III criteria (Bhatia 1991; Bremner 1995; Carman 1991; Gelenberg 1990; Hicks 1988; Hoschl 1989; Jacobson 1990; Katz 1993; Klieser 1988; Langlois 1985; Organon 3‐020 unpublished; Organon 84062 unpublished; Preskorn 1983; Reimherr 1990; Rickels 1982; Rickels 1985; Smith 1990; Roffman 1982; Wilcox 1994), 12 according to RDC (Amsterdam 1986;Claghorn 1983; Georgotas 1982; Kupfer 1979; McNair 1984a; Mynors‐Wallis 1995; Paykel 1988a; Rowan 1980; Shipley 1981; Stratas 1984; Thomson 1982; van de Merwe 1984a), four according to DSM‐III‐R criteria (Bakish 1992; Katz 1993a; Kusalic 1993; Lydiard 1997), one according to its own operationalised criteria (Blashki 1971) and two according to Feighner criteria (Feighner 1979; Raft 1981).

Intervention

All studies compared amitriptyline with placebo, three of them only in a two‐arm comparison (Kupfer 1979; Paykel 1988a; Shipley 1981), whereas 36 used a three or more arms design. All studies had a placebo arm; there was no trial with 'no treatment' in the comparator group.

Setting

In 25 studies the participants were outpatients (Amsterdam 1986; Bakish 1992; Blashki 1971; Bremner 1995; Carman 1991; Claghorn 1983; Feighner 1979; Gelenberg 1990; Jacobson 1990; Kusalic 1993; Langlois 1985; Lydiard 1997; McNair 1984a; Mynors‐Wallis 1995; Organon 3‐020 unpublished; Organon 84062 unpublished; Paykel 1988a; Reimherr 1990; Rickels 1982; Rickels 1985; Rowan 1980; Smith 1990; Stratas 1984; Thomson 1982; Wilcox 1994). In eight studies the participants were inpatients (Bhatia 1991; Hicks 1988; Hoschl 1989; Klieser 1988; Kupfer 1979; Preskorn 1983; Raft 1981; Shipley 1981), whereas in two studies outpatients and inpatients were included (Hormazabal 1985; van de Merwe 1984a). In four studies the setting remained unclear (Georgotas 1982; Katz 1993; Katz 1993a; Roffman 1982).

Dosage of study drug

The mean dosage of amitriptyline was 139.6 mg/day (SD 40.4); nine trials did not specify the mean dosage (Carman 1991; Georgotas 1982; Katz 1993; Katz 1993a; Organon 84062 unpublished; Preskorn 1983; Rowan 1980; Roffman 1982; Shipley 1981). In 30 studies the dosage of amitriptyline was within the therapeutic dosage range (25 to 300 mg/day, 25 mg was only a starting dose in some studies which could be increased); in two studies only the maximum dosage was reported (Amsterdam 1986; Mynors‐Wallis 1995). Only one study did not provide any information about the mean dose or the dosage range (Preskorn 1983).

Twenty‐nine trials used a flexible and eight trials a fixed‐dosage regimen (Blashki 1971; Klieser 1988; Kupfer 1979; Langlois 1985; Mynors‐Wallis 1995; Shipley 1981; Roffman 1982; Thomson 1982). The dosage regimen remained unclear in two studies (Kusalic 1993; Preskorn 1983).

Primary outcome

The primary outcome used in the great majority of studies was change from baseline on the HAM‐D. Specifically, 24 studies used the scale HAM‐D‐17 and in one study the HAM‐D‐17 was only used as threshold for inclusion, but there were no response and remission data anyway (van de Merwe 1984a). In nine studies the HAM‐D‐21 was used (Amsterdam 1986; Claghorn 1983; Gelenberg 1990; Georgotas 1982; Hormazabal 1985; Rickels 1982; Rickels 1985; Roffman 1982; Stratas 1984) and in one study the HAM‐D‐24 (Feighner 1979). One study used the first 18 items of the 21‐item HAM‐D (Thomson 1982) and one study the first 16 items (Hoschl 1989). Two studies did not provide any information (Klieser 1988; Preskorn 1983).

Response definitions

In 13 studies response was defined as showing at least a 50% reduction in the HAM‐D (Amsterdam 1986; Bakish 1992; Bremner 1995; Claghorn 1983; Feighner 1979; Gelenberg 1990; Jacobson 1990; Kusalic 1993; Organon 3‐020 unpublished; Organon 84062 unpublished; Rickels 1985; Smith 1990; Wilcox 1994), whereas there was no definition of response in 15 studies (Carman 1991; Georgotas 1982; Hormazabal 1985; Katz 1993;Katz 1993a; Klieser 1988; Langlois 1985; McNair 1984a; Mynors‐Wallis 1995; Preskorn 1983; Raft 1981; Rowan 1980; Shipley 1981; Stratas 1984; van de Merwe 1984a). In one study response was defined as a 50% reduction in HAM‐D‐17 baseline score without subsequent deterioration beyond 20% of achieved HAM‐D score (Roffman 1982) and in one study as an improvement with HAM‐D < 10 (Hoschl 1989). In one study a HAM‐D score of 12 was used as the cutoff score for responders (Kupfer 1979), in one study response was defined as a CGI ≤ 2 (Lydiard 1997) and in one study response was defined as a moderate or marked global improvement (Rickels 1982).

Remission definitions

In one study remission was defined as recovery (the criteria were a HAM‐D score ≤ 7 and Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) ≤ 8 (Mynors‐Wallis 1995)) and in one study remission was defined as a fall to 4 points or less on the total HAM‐D score (Thomson 1982), whereas all other studies did not provide a definition of remission.

Sponsorship

Twenty‐six studies were sponsored by a drug company (Amsterdam 1986; Bakish 1992; Bhatia 1991; Bremner 1995; Carman 1991; Claghorn 1983; Gelenberg 1990; Georgotas 1982; Hicks 1988; Hormazabal 1985; Jacobson 1990; Katz 1993; Katz 1993a; Langlois 1985; Lydiard 1997; McNair 1984a; Organon 3‐020 unpublished; Organon 84062 unpublished; Rickels 1982; Rickels 1985; Rowan 1980; Smith 1990; Roffman 1982; Thomson 1982; van de Merwe 1984a; Wilcox 1994). In two studies the sponsorship was unclear (Klieser 1988; Reimherr 1990) whereas 11 studies were not sponsored (Blashki 1971; Feighner 1979; Hoschl 1989; Kupfer 1979; Kusalic 1993; Mynors‐Wallis 1995; Paykel 1988a; Preskorn 1983; Raft 1981; Shipley 1981; Stratas 1984). It should be noted that we did not classify a study as industry‐sponsored when only the medication was provided. Moreover, in none of the industry‐sponsored studies was the focus on amitriptyline. Either the sponsor was the manufacturer of another antidepressant or the sponsor produced both amitriptyline and another, newer antidepressant, but the focus was on the new antidepressant. Amitriptyline was rather an active comparator in addition to placebo versus the new antidepressant in these trials.

Excluded studies

Eighty‐two abstracts on 81 studies for which we assessed the full publications were excluded because they did not use operationalised criteria (N = 38), did not have a placebo group (N = 19) or amitriptyline group (N = 7), were review articles (N=10), were not randomised (N = 3), had included more than 20% of participants with other diagnoses than major depressive disorder (N = 2), studied children (N = 1) or were conducted in stable participants (N = 1).

Studies awaiting classification

One study is currently awaiting assessment (Kahn 2008). The available report is just a follow‐up of a potentially eligible trial. Too little information on the relevant original study could be obtained from the authors, so we decided to classify this study as awaiting assessment.

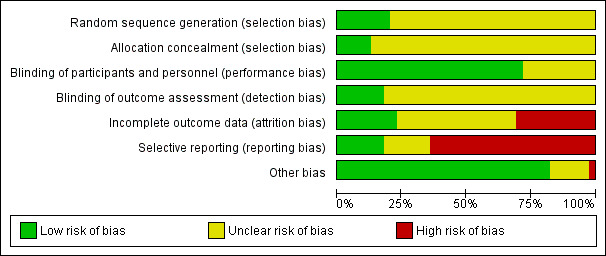

Risk of bias in included studies

A summary of the 'Risk of bias' assessment is provided in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

2.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

The vast majority of the studies were just stated to be randomised without indicating details of how the sequence was generated. The same held true for allocation concealment. Thus, it is unclear whether participants were adequately randomised and allocated.

Blinding

All studies were described as double‐blind, although not all RCTs provided at least a few details (e.g. statements such as "identical capsules") as to how blinding was assured. Very few studies made a statement about the blinding of assessor (detection bias).

Incomplete outcome data

In approximately 30% of the studies we felt that there was a high risk of bias due to incomplete outcome data. The main reasons for this were that the study authors either did not report reasons for drop‐out clearly enough or presented only completer analyses. Moreover, frequently more participants in the placebo group clearly dropped out due to inefficacy of treatment and more participants in the drug group dropped out due to adverse events.

Selective reporting

A general problem was that standard deviations were often not reported so that in the vast majority of the trials we had to apply the mean SDs from the "meta‐analysis of new generation antidepressants" (MANGA) project (Cipriani 2009).

Other potential sources of bias

Klieser 1988 reported only interim results. It is unclear whether the study has been completed. There were no other clear sources of bias.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Amitriptyline versus placebo

1. Primary outcome ‐ response to treatment

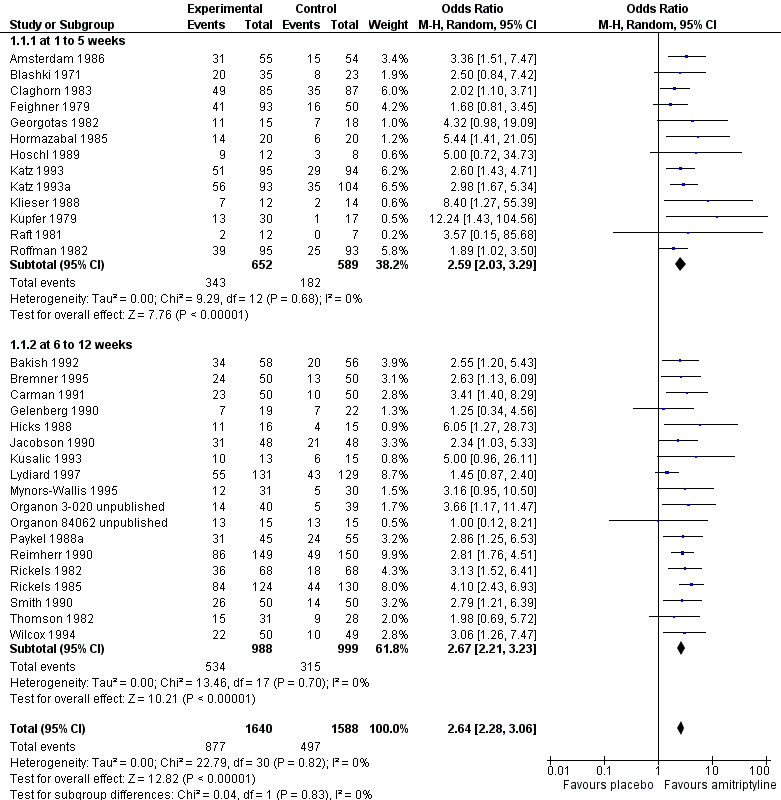

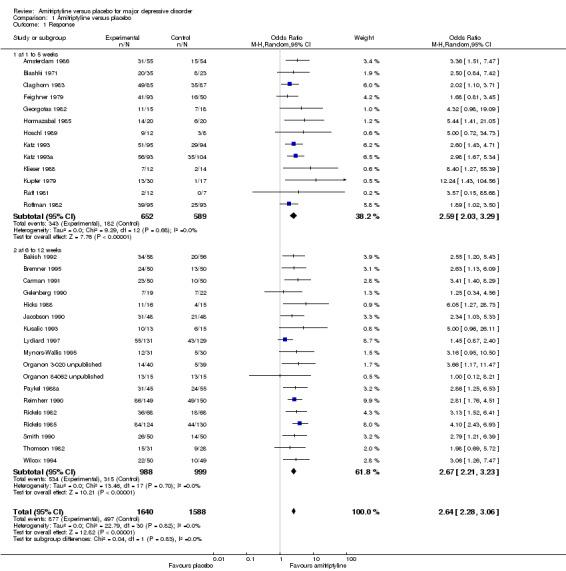

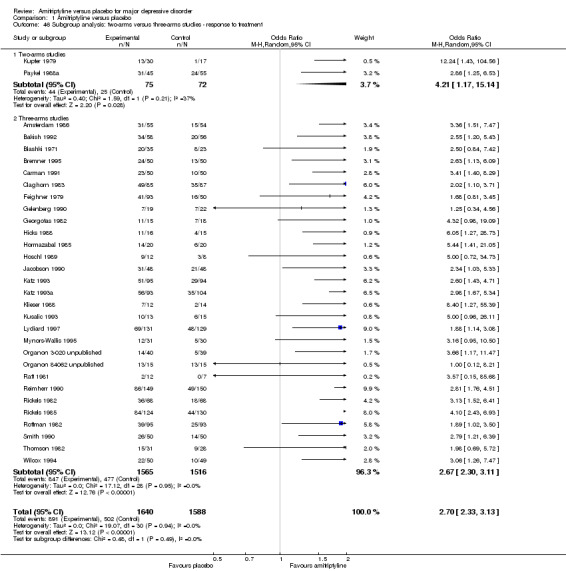

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Amitriptyline versus placebo, outcome: 1.1 Response.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Amitriptyline versus placebo, Outcome 1 Response.

a) Early response (one to five weeks)

Significantly more participants in the amitriptyline group than in the placebo group responded to treatment (odds ratio (OR) 2.59, 95% confidence interval (CI) 2.03 to 3.29, P < 0.00001, I² = 0%, 13 randomised controlled trials (RCTs), 1241 participants).

b) Acute‐phase response (6 to 12 weeks)

Significantly more participants in the amitriptyline group than in the placebo group responded to treatment (OR 2.67, 95% CI 2.21 to 3.23, P < 0.00001, I² = 0%, 18 RCTs, 1987 participants).

c) Overall results (1 to 12 weeks, i.e. combining early response and acute‐phase response)

Significantly more participants in the amitriptyline group than in the placebo group responded to treatment (OR 2.64, 95% CI 2.28 to 3.06, P < 0.00001, I² = 0%, 31 RCTs, 3228 participants).

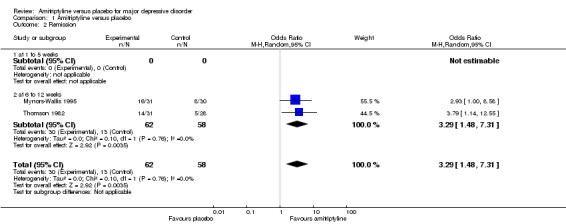

2. Remission

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Amitriptyline versus placebo, Outcome 2 Remission.

a) Early phase (one to five weeks)

No data available.

b) Acute phase (6 to 12 weeks)

Significantly more participants in the amitriptyline group than in the placebo group remitted (OR 3.29, 95% CI 1.48 to 7.31, P = 0.004, I² = 0%, two RCTs, 120 participants).

c) Overall results (1 to 12 weeks)

As there were only data for the acute phase (6 to 12 weeks), the overall results correspond to 2b).

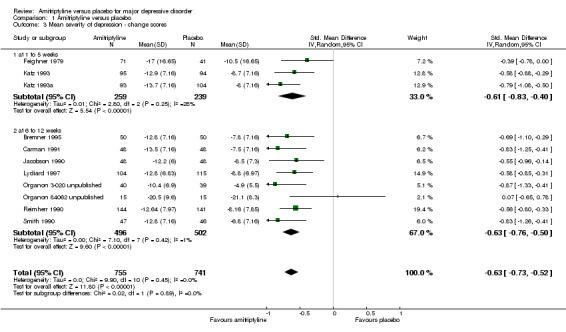

3. Mean severity of depression reduction from baseline to endpoint

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Amitriptyline versus placebo, Outcome 3 Mean severity of depression ‐ change scores.

a) Early phase (one to five weeks)

The data suggest that amitriptyline was superior to placebo (standardised mean difference (SMD) ‐0.61, 95% CI ‐0.83 to ‐0.40, P < 0.00001, I² = 28%, three RCTs, 498 participants).

b) Acute phase (6 to 12 weeks)

The data suggest that amitriptyline was superior to placebo (SMD ‐0.63, 95% CI ‐0.76 to ‐0.50, P < 0.00001, I² = 1%, eight RCTs, 998 participants).

c) Overall results (1 to 12 weeks)

The data suggest that amitriptyline was superior to placebo (SMD ‐0.63, 95% CI ‐0.73 to ‐0.52, P < 0.00001, I² = 0%, 11 RCTs, 1496 participants).

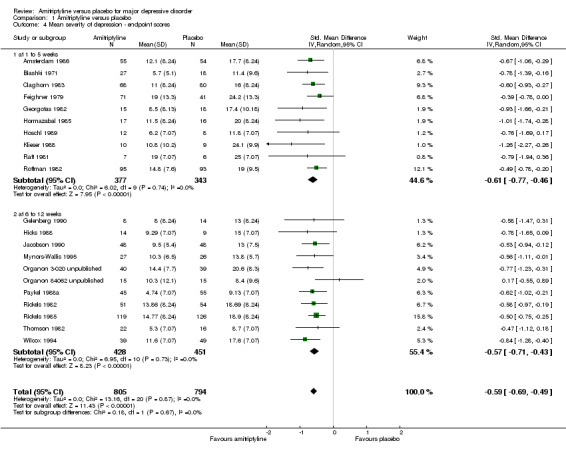

4. Mean severity of depression at endpoint

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Amitriptyline versus placebo, Outcome 4 Mean severity of depression ‐ endpoint scores.

a) Early phase (one to five weeks)

The data suggest that amitriptyline was superior to placebo (SMD ‐0.61, 95% CI ‐0.77 to ‐0.46, P < 0.00001, I² = 0%, 10 RCTs, 720 participants).

b) Acute phase (6 to 12 weeks)

The data suggest that amitriptyline was superior to placebo (SMD ‐0.57, 95% CI ‐0.71 to ‐0.43, P < 0.00001, I² = 0%, 11 RCTs, 879 participants).

c) Overall results (1 to 12 weeks)

The data suggest that amitriptyline was superior to placebo (SMD ‐0.59, 95% CI ‐0.69 to ‐0.49, P < 0.00001, I² = 0%, 21 RCTs, 1599 participants).

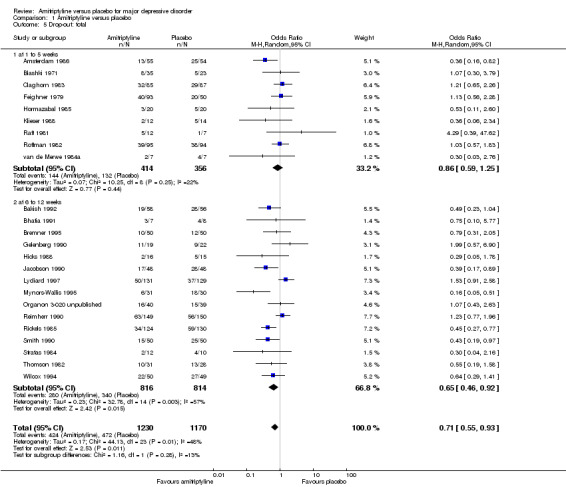

5. Drop‐out due to any reason

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Amitriptyline versus placebo, Outcome 5 Drop‐out: total.

a) Early phase (one to five weeks)

The drop‐out rates due to any reason showed no statistically significant superiority of amitriptyline compared to placebo (OR 0.86, 95% CI 0.59 to 1.25, P = 0.44, nine RCTs, 770 participants).

b) Acute phase (6 to 12 weeks)

The drop‐out rates due to any reason in the acute phase revealed a non‐significant trend in favour of amitriptyline (OR 0.65, 95% CI 0.46 to 0.92, P = 0.02, 15 RCTs, 1630 participants). There was moderate heterogeneity (Tau² = 0.23; Chi² = 32.78, df = 14 (P = 0.003); I² = 57%).

c) Overall results (1 to 12 weeks)

The overall drop‐out rates revealed a significant superiority of amitriptyline (OR 0.71, 95% CI 0.55 to 0.93, P = 0.01, 24 RCTs, 2400 participants). The results were moderately heterogeneous (Tau² = 0.17; Chi² = 44.13, df = 23 (P = 0.005); I² = 48%) with some studies favouring amitriptyline and others placebo. Drop‐out due to any reason is not an operationalised outcome which may explain some of the heterogeneity.

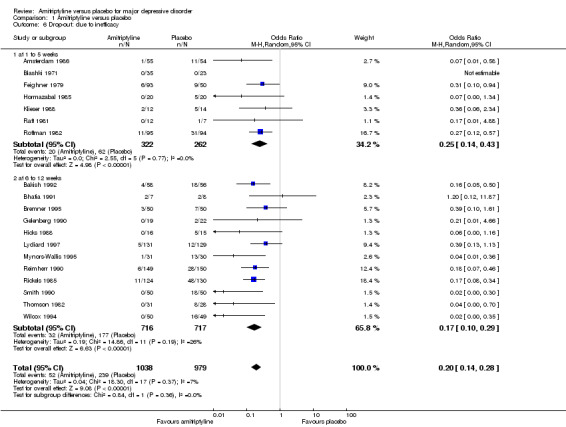

6. Drop‐out due to inefficacy

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Amitriptyline versus placebo, Outcome 6 Drop‐out: due to inefficacy.

a) Early phase (one to five weeks)

The drop‐out rates due to inefficacy suggest that amitriptyline is superior to placebo (OR 0.25, 95% CI 0.14 to 0.43, P < 0.00001, seven RCTs, 584 participants).

b) Acute phase (6 to 12 weeks)

The drop‐out rates due to inefficacy suggest that amitriptyline is superior to placebo (OR 0.17, 95% CI 0.10 to 0.29, P < 0.00001, 12 RCTs, 1433 participants).

c) Overall results (1 to 12 weeks)

The drop‐out rates due to inefficacy suggest that amitriptyline is superior to placebo (OR 0.20, 95% CI 0.14 to 0.28, P < 0.00001, 19 RCTs, 2017 participants).

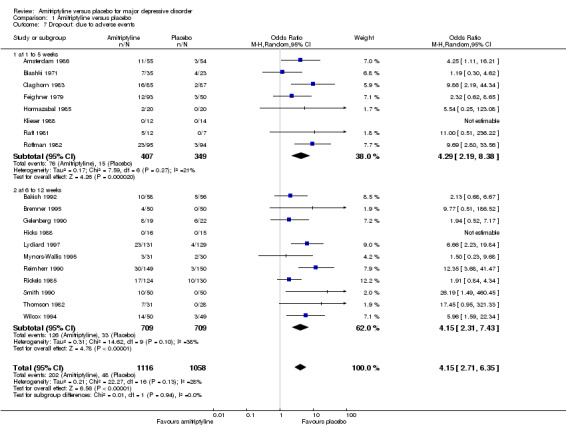

7. Drop‐out due to adverse events

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Amitriptyline versus placebo, Outcome 7 Drop‐out: due to adverse events.

a) Early phase (one to five weeks)

The drop‐out rates due to adverse events suggest that amitriptyline is inferior to placebo (OR 4.29, 95% CI 2.19 to 8.38, P < 0.0001, eight RCTs, 756 participants).

b) Acute phase (6 to 12 weeks)

The drop‐out rates due to adverse events suggest that amitriptyline is inferior to placebo (OR 4.15, 95% CI 2.31 to 7.43, P < 0.00001, 11 RCTs, 1418 participants).

c) Overall results (1 to 12 weeks)

The drop‐out rates due to adverse events suggest that amitriptyline is inferior to placebo (OR 4.15, 95% CI 2.71 to 6.35, P < 0.00001, 19 RCTs, 2174 participants).

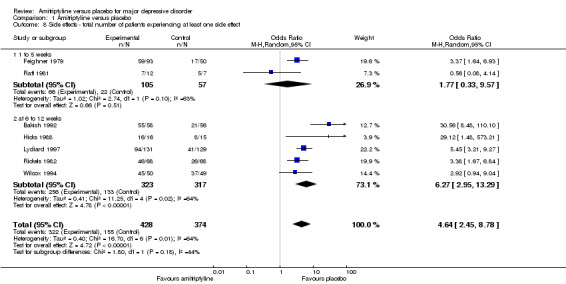

Side effects

8. Total number of participants experiencing at least one side effect

Overall significantly more participants in the amitriptyline group experienced at least one side effect (OR 4.64, 95% CI 2.45 to 8.78, P < 0.00001, seven RCTs, 802 participants). There was substantial heterogeneity (Tau² = 0.40; Chi² = 16.70, df = 6 (P = 0.01); I² = 64%), but with one exception (Raft 1981) all studies at least tended to favour placebo. Inspection of Raft 1981 revealed no obvious reason for the heterogeneity (Analysis 1.8).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Amitriptyline versus placebo, Outcome 8 Side effects ‐ total number of patients experiencing at least one side effect.

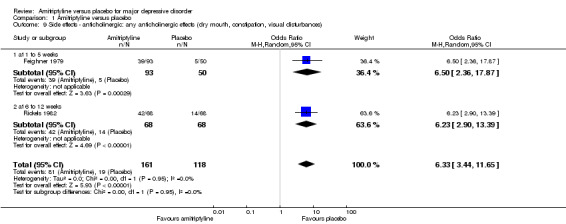

9. Anticholinergic: any anticholinergic effects (dry mouth, constipation, visual disturbances)

Overall significantly more participants in the amitriptyline group experienced any anticholinergic adverse effects (OR 6.33, 95% CI 3.44 to 11.65, P < 0.00001, two RCTs, 279 participants) (Analysis 1.9).

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Amitriptyline versus placebo, Outcome 9 Side effects ‐ anticholinergic: any anticholinergic effects (dry mouth, constipation, visual disturbances).

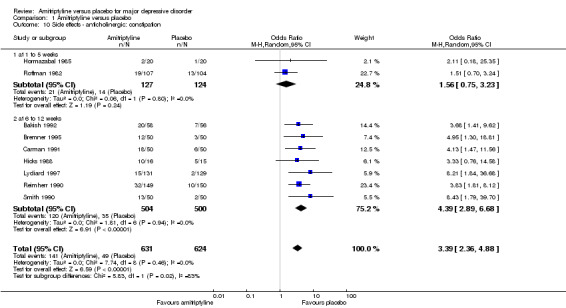

10. Anticholinergic: constipation

Overall significantly more participants in the amitriptyline group suffered from constipation (OR 3.39, 95% CI 2.36 to 4.88, P < 0.00001, nine RCTs, 1255 participants) (Analysis 1.10).

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Amitriptyline versus placebo, Outcome 10 Side effects ‐ anticholinergic: constipation.

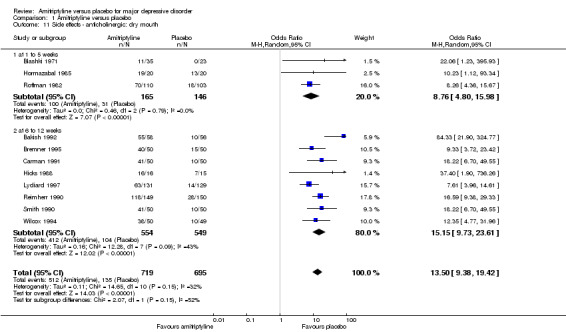

11. Anticholinergic: dry mouth

Overall significantly more participants in the amitriptyline group suffered from dry mouth (OR 13.50, 95% CI 9.38 to 19.42, P < 0.00001, 11 RCTs, 1414 participants). There was moderate heterogeneity (Tau² = 0.16; Chi² = 12.28, df = 7 (P = 0.09); I² = 43%), but the effects of all studies were in favour of placebo (Analysis 1.11).

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Amitriptyline versus placebo, Outcome 11 Side effects ‐ anticholinergic: dry mouth.

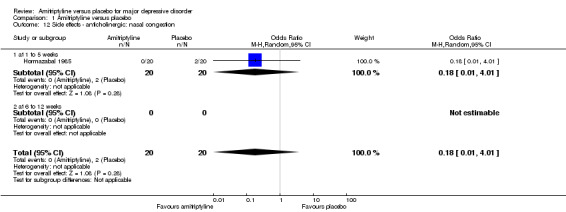

12. Anticholinergic: nasal congestion

The adverse event nasal congestion was only recorded by Hormazabal 1985. There was no statistically significant difference between the amitriptyline and placebo group (OR 0.18, 95% CI 0.01 to 4.01, P = 0.28, one RCT, 40 participants) (Analysis 1.12).

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Amitriptyline versus placebo, Outcome 12 Side effects ‐ anticholinergic: nasal congestion.

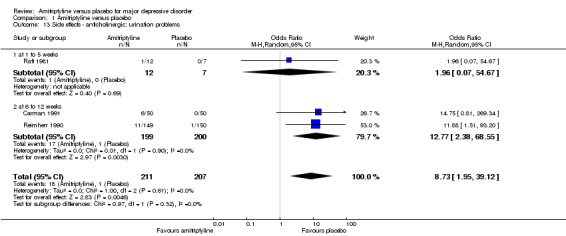

13. Anticholinergic: urination problems

Overall significantly more participants in the amitriptyline group experienced urination problems (OR 8.73, 95% CI 1.95 to 39.12, P = 0.005, three RCTs, 418 participants) (Analysis 1.13).

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Amitriptyline versus placebo, Outcome 13 Side effects ‐ anticholinergic: urination problems.

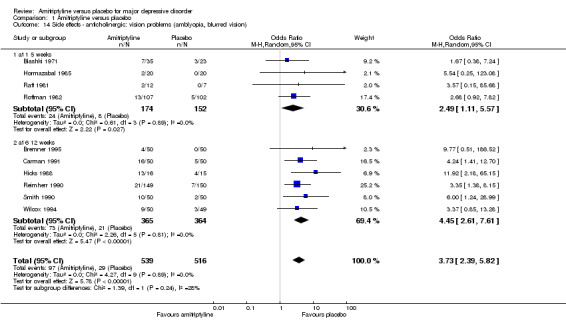

14. Anticholinergic: vision problems (amblyopia, blurred vision)

Overall significantly more participants in the amitriptyline group experienced vision problems (OR 3.73, 95% CI 2.39 to 5.82, P < 0.00001, 10 RCTs, 1055 participants) (Analysis 1.14).

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Amitriptyline versus placebo, Outcome 14 Side effects ‐ anticholinergic: vision problems (amblyopia, blurred vision).

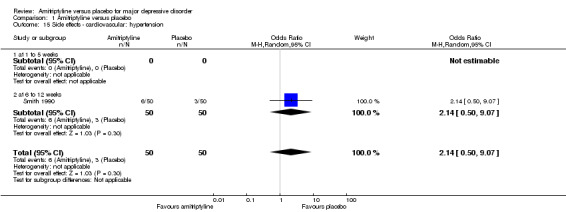

15. Cardiovascular: hypertension

The adverse event hypertension was only recorded by Smith 1990. There was no statistically significant difference between the amitriptyline and placebo group (OR 2.14, 95% CI 0.50 to 9.07, P = 0.30, one RCT, 100 participants) (Analysis 1.15).

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Amitriptyline versus placebo, Outcome 15 Side effects ‐ cardiovascular: hypertension.

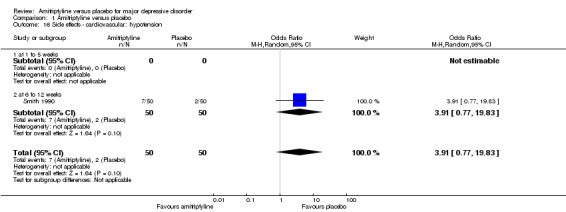

16. Cardiovascular: hypotension

The adverse event hypotension was only recorded by Smith 1990. There was no statistically significant difference between the amitriptyline and placebo group (OR 3.91, 95% CI 0.77 to 19.83, P = 0.10, one RCT, 100 participants) (Analysis 1.16).

1.16. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Amitriptyline versus placebo, Outcome 16 Side effects ‐ cardiovascular: hypotension.

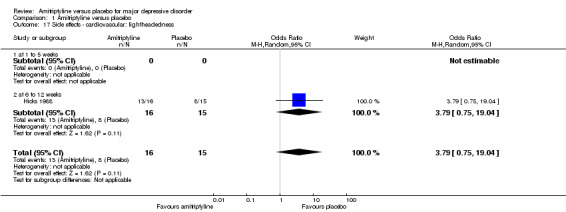

17. Cardiovascular: lightheadedness

The adverse event lightheadedness was only recorded by Hicks 1988. There was no statistically significant difference between the amitriptyline and placebo group (OR 3.79, 95% CI 0.75 to 19.04, P = 0.11, one RCT, 31 participants) (Analysis 1.17).

1.17. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Amitriptyline versus placebo, Outcome 17 Side effects ‐ cardiovascular: lightheadedness.

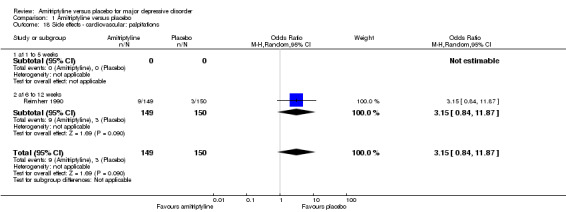

18. Cardiovascular: palpitations

The adverse event palpitations was only recorded by Reimherr 1990. There was no statistically significant difference between the amitriptyline and placebo group (OR 3.15, 95% CI 0.84 to 11.87, P = 0.09, one RCT, 299 participants) (Analysis 1.18).

1.18. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Amitriptyline versus placebo, Outcome 18 Side effects ‐ cardiovascular: palpitations.

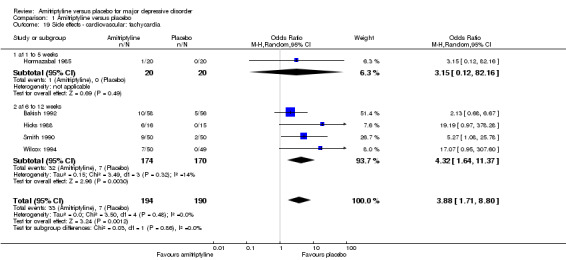

19. Cardiovascular: tachycardia

Overall significantly more participants in the amitriptyline group suffered from tachycardia (OR 3.88, 95% CI 1.71 to 8.80, P = 0.001, five RCTs, 384 participants) (Analysis 1.19).

1.19. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Amitriptyline versus placebo, Outcome 19 Side effects ‐ cardiovascular: tachycardia.

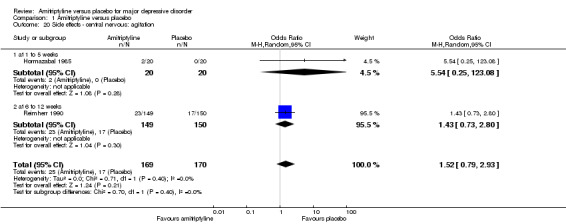

20. Central nervous: agitation

There was no statistically significant difference between the amitriptyline and placebo group (OR 1.52, 95% CI 0.79 to 2.93, P = 0.21, two RCTs, 339 participants) (Analysis 1.20).

1.20. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Amitriptyline versus placebo, Outcome 20 Side effects ‐ central nervous: agitation.

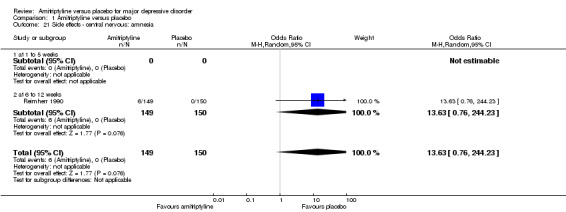

21. Central nervous: amnesia

The adverse event amnesia was only recorded by Reimherr 1990. There was no statistically significant difference between the amitriptyline and placebo group (OR 13.63, 95% CI 0.76 to 244.23, P = 0.08, one RCT, 299 participants) (Analysis 1.21).

1.21. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Amitriptyline versus placebo, Outcome 21 Side effects ‐ central nervous: amnesia.

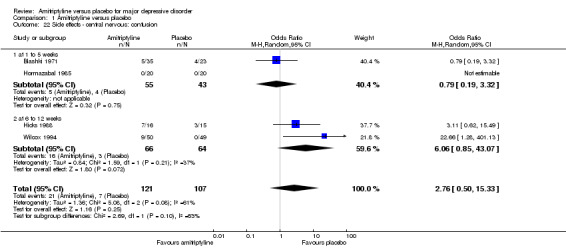

22. Central nervous: confusion

There was no statistically significant difference between the amitriptyline and placebo group (OR 2.76, 95% CI 0.50 to 15.33, P = 0.25, four RCTs, 228 participants). There was substantial heterogeneity (Tau² = 1.36; Chi² = 5.08, df = 2 (P = 0.08); I² = 61%) but as only three studies reported this outcome, two of which favoured placebo and one amitriptyline, this result is not robust in any case (Analysis 1.22).

1.22. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Amitriptyline versus placebo, Outcome 22 Side effects ‐ central nervous: confusion.

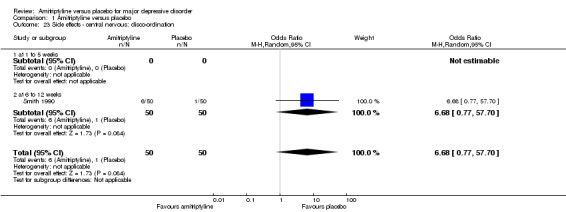

23. Central nervous: disco‐ordination

The adverse event disco‐ordination was only recorded by Smith 1990. There was no statistically significant difference between the amitriptyline and placebo‐treated group (OR 6.68, 95% CI 0.77 to 57.70, P = 0.08, one RCT, 100 participants) (Analysis 1.23).

1.23. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Amitriptyline versus placebo, Outcome 23 Side effects ‐ central nervous: disco‐ordination.

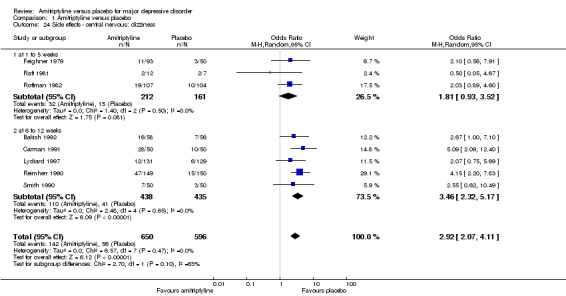

24. Central nervous: dizziness

Overall significantly more participants in the amitriptyline group suffered from dizziness (OR 2.92, 95% CI 2.07 to 4.11, P < 0.00001, eight RCTs, 1246 participants) (Analysis 1.24).

1.24. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Amitriptyline versus placebo, Outcome 24 Side effects ‐ central nervous: dizziness.

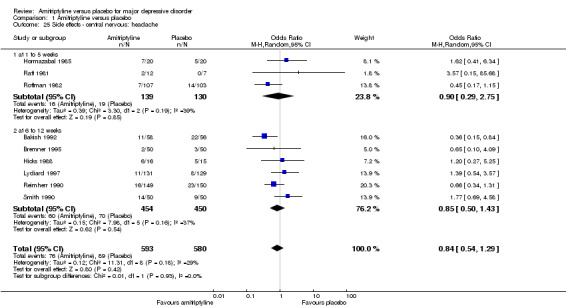

25. Central nervous: headache

There was no statistically significant difference between the amitriptyline and placebo group (OR 0.84, 95% CI 0.54 to 1.29, P = 0.42, nine RCTs, 1173 participants) (Analysis 1.25).

1.25. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Amitriptyline versus placebo, Outcome 25 Side effects ‐ central nervous: headache.

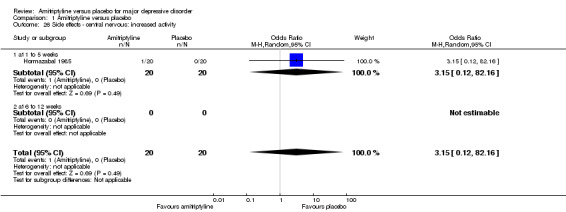

26. Central nervous: increased activity

The adverse event increased activity was only recorded by Hormazabal 1985. There was no statistically significant difference between the amitriptyline and placebo group (OR 3.15, 95% CI 0.12 to 82.16, P = 0.49, one RCT, 40 participants) (Analysis 1.26).

1.26. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Amitriptyline versus placebo, Outcome 26 Side effects ‐ central nervous: increased activity.

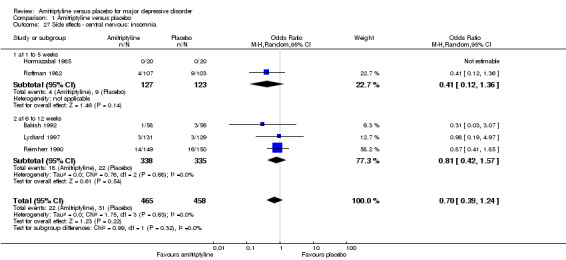

27. Central nervous: insomnia

There was no statistically significant difference between the amitriptyline and placebo group (OR 0.70, 95% CI 0.39 to 1.24, P = 0.22, five RCTs, 923 participants) (Analysis 1.27).

1.27. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Amitriptyline versus placebo, Outcome 27 Side effects ‐ central nervous: insomnia.

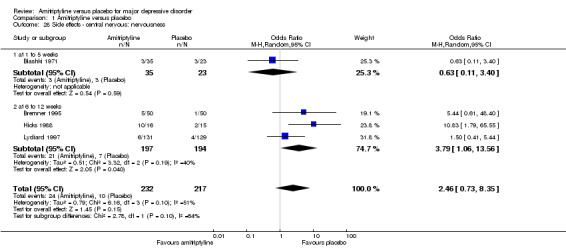

28. Central nervous: nervousness

There was no statistically significant difference between the amitriptyline and placebo group (OR 2.46, 95% CI 0.73 to 8.35, P = 0.001, four RCTs, 449 participants). There was moderate heterogeneity (Tau² = 0.79; Chi² = 6.16, df = 3 (P = 0.10); I² = 51%) among the three available studies. Obvious reasons explaining the heterogeneity could not be identified (Analysis 1.28).

1.28. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Amitriptyline versus placebo, Outcome 28 Side effects ‐ central nervous: nervousness.

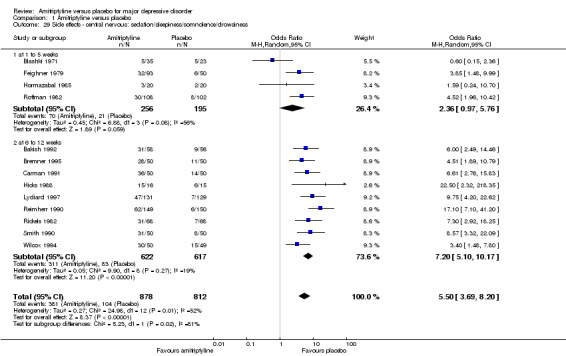

29. Central nervous: sedation/sleepiness/somnolence/drowsiness

Overall significantly more participants in the amitriptyline group suffered from sedation/sleepiness/somnolence/drowsiness (OR 5.50, 95% CI 3.69 to 8.20, P < 0.00001, 13 RCTs, 1690 participants). There was moderate heterogeneity (Tau² = 0.27; Chi² = 24.98, df = 12 (P = 0.01); I² = 52%), because a single outlier study showed an advantage of amitriptyline (Blashki 1971). Excluding this study reduced heterogeneity to an I2 value of 22% (Analysis 1.29).

1.29. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Amitriptyline versus placebo, Outcome 29 Side effects ‐ central nervous: sedation/sleepiness/somnolence/drowsiness.

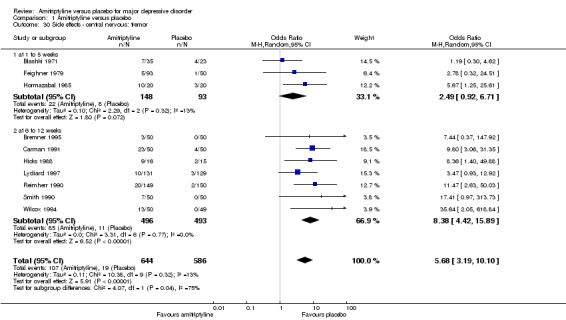

30. Central nervous: tremor

Overall significantly more participants in the amitriptyline group suffered from tremor (OR 5.68, 95% CI 3.19 to 10.10, P < 0.00001, 10 RCTs, 1230 participants) (Analysis 1.30).

1.30. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Amitriptyline versus placebo, Outcome 30 Side effects ‐ central nervous: tremor.

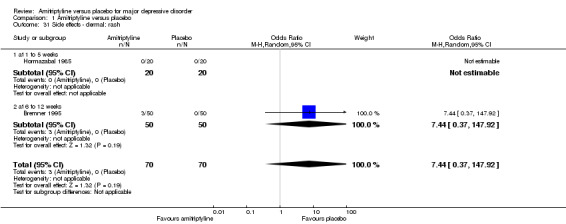

31. Dermal: rash

There was no statistically significant difference between the amitriptyline and placebo group (OR 7.44, 95% CI 0.37 to 147.92, P = 0.19, two RCTs, 140 participants) (Analysis 1.31).

1.31. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Amitriptyline versus placebo, Outcome 31 Side effects ‐ dermal: rash.

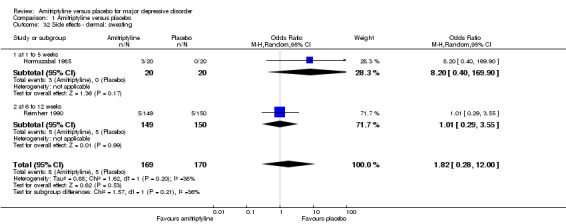

32. Dermal: sweating

There was no statistically significant difference between the amitriptyline and placebo group (OR 1.82, 95% CI 0.28 to 12.00, P = 0.53, two RCTs, 339 participants) (Analysis 1.32).

1.32. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Amitriptyline versus placebo, Outcome 32 Side effects ‐ dermal: sweating.

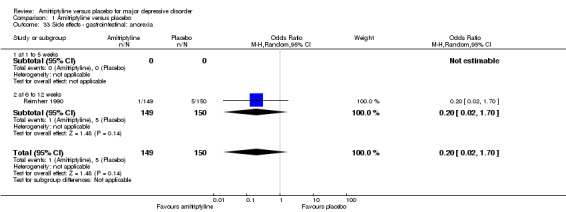

33. Gastrointestinal: anorexia

The adverse event anorexia was only recorded by Reimherr 1990. There was no statistically significant difference between the amitriptyline and placebo group (OR 0.20, 95% CI 0.02 to 1.70, P = 0.14, one RCT, 299 participants) (Analysis 1.33).

1.33. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Amitriptyline versus placebo, Outcome 33 Side effects ‐ gastrointestinal: anorexia.

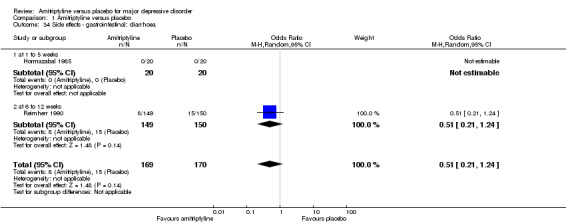

34. Gastrointestinal: diarrhoea

There was no statistically significant difference between the amitriptyline and placebo group (OR 0.51, 95% CI 0.21 to 1.24, P = 0.14, two RCTs, 339 participants) (Analysis 1.34).

1.34. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Amitriptyline versus placebo, Outcome 34 Side effects ‐ gastrointestinal: diarrhoea.

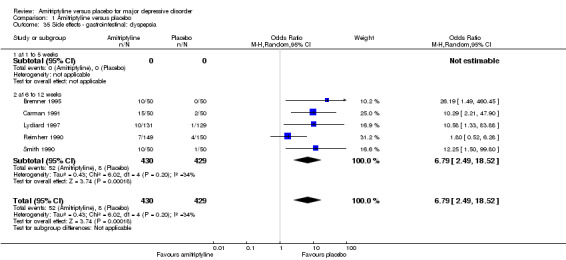

35. Gastrointestinal: dyspepsia

Overall significantly more participants in the amitriptyline group suffered from gastralgia (OR 6.79, 95% CI 2.49 to 18.52, P = 0.0002, five RCTs, 859 participants) (Analysis 1.35).

1.35. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Amitriptyline versus placebo, Outcome 35 Side effects ‐ gastrointestinal: dyspepsia.

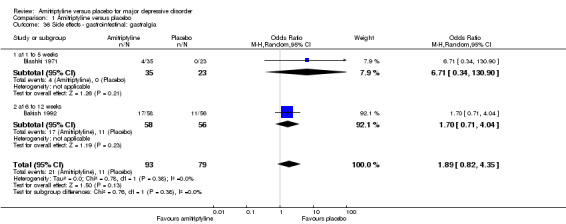

36. Gastrointestinal: gastralgia

There was no statistically significant difference between the amitriptyline and placebo group (OR 1.89, 95% CI 0.82 to 4.35, P = 0.38, two RCTs, 172 participants) (Analysis 1.36).

1.36. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Amitriptyline versus placebo, Outcome 36 Side effects ‐ gastrointestinal: gastralgia.

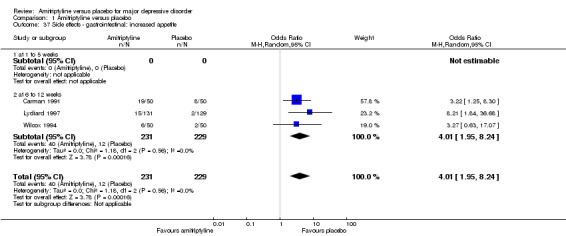

37. Gastrointestinal: increased appetite

Overall significantly more participants in the amitriptyline group suffered from increased appetite (OR 4.01, 95% CI 1.95 to 8.24, P = 0.0002, three RCTs, 460 participants) (Analysis 1.37).

1.37. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Amitriptyline versus placebo, Outcome 37 Side effects ‐ gastrointestinal: increased appetite.

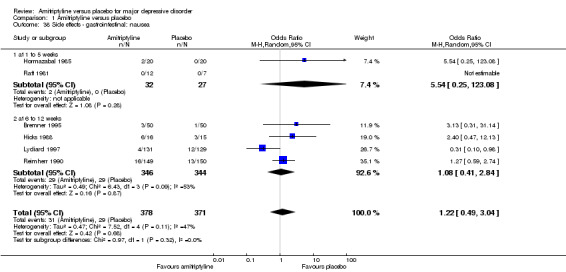

38. Gastrointestinal: nausea

There was no statistically significant difference between the amitriptyline and placebo group (OR 1.22, 95% CI 0.49 to 3.04, P = 0.68, six RCTs, 749 participants). There was moderate heterogeneity (Tau² = 0.47; Chi² = 7.52, df = 4 (P = 0.11); I² = 47%). Excluding the single outlier study (Lydiard 1997) that showed an advantage of amitriptyline reduced the I² value to 0%, but there was still no significant difference between groups (Analysis 1.38).

1.38. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Amitriptyline versus placebo, Outcome 38 Side effects ‐ gastrointestinal: nausea.

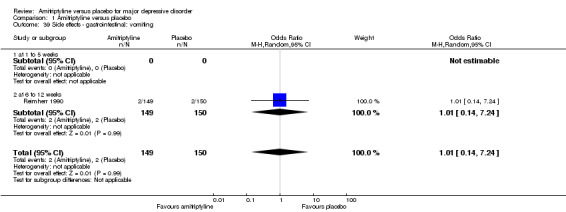

39. Gastrointestinal: vomiting

The adverse event vomiting was only recorded by Reimherr 1990. There was no statistically significant difference between the amitriptyline and placebo group (OR 1.01, 95% CI 0.14 to 7.24, P = 0.99, one RCTs, 299 participants) (Analysis 1.39).

1.39. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Amitriptyline versus placebo, Outcome 39 Side effects ‐ gastrointestinal: vomiting.

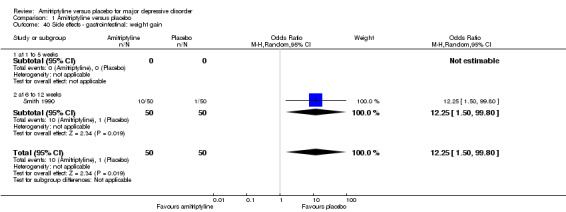

40. Gastrointestinal: weight gain

The adverse event weight gain was only recorded by Smith 1990. Significantly more participants in the amitriptyline group gained weight (OR 12.25, 95% CI 1.50 to 99.80, P = 0.002, one RCT, 100 participants) (Analysis 1.40).

1.40. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Amitriptyline versus placebo, Outcome 40 Side effects ‐ gastrointestinal: weight gain.

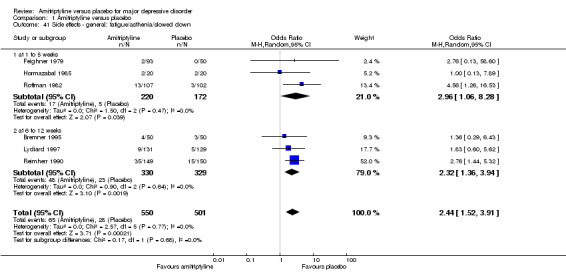

41. General: fatigue/asthenia/slowed down

Overall significantly more participants in the amitriptyline group suffered from this adverse event (OR 2.44, 95% CI 1.52 to 3.91, P = 0.0002, six RCTs, 1051 participants) (Analysis 1.41).

1.41. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Amitriptyline versus placebo, Outcome 41 Side effects ‐ general: fatigue/asthenia/slowed down.

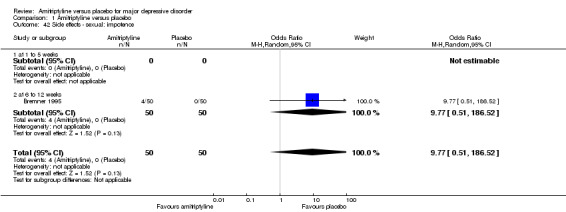

42. Sexual: impotence

The adverse event impotence was only recorded by Bremner 1995. There was no statistically significant difference between the amitriptyline and placebo group (OR 9.77, 95% CI 0.51 to 186.52, P = 0.13, one RCT, 100 participants) (Analysis 1.42).

1.42. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Amitriptyline versus placebo, Outcome 42 Side effects ‐ sexual: impotence.

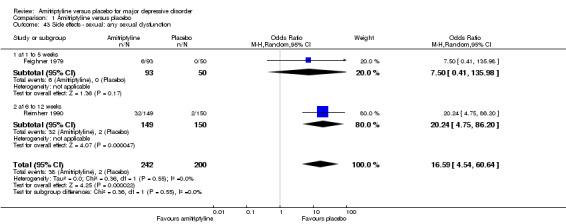

43. Sexual: any sexual dysfunction

Overall significantly more participants in the amitriptyline group suffered from sexual dysfunction (OR 16.59, 95% CI 4.54 to 60.64, P < 0.0001, two RCTs, 442 participants) (Analysis 1.43).

1.43. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Amitriptyline versus placebo, Outcome 43 Side effects ‐ sexual: any sexual dysfunction.

44. Missing outcomes

No data were available for the outcomes 'social adjustment', 'quality of life' and 'death'.

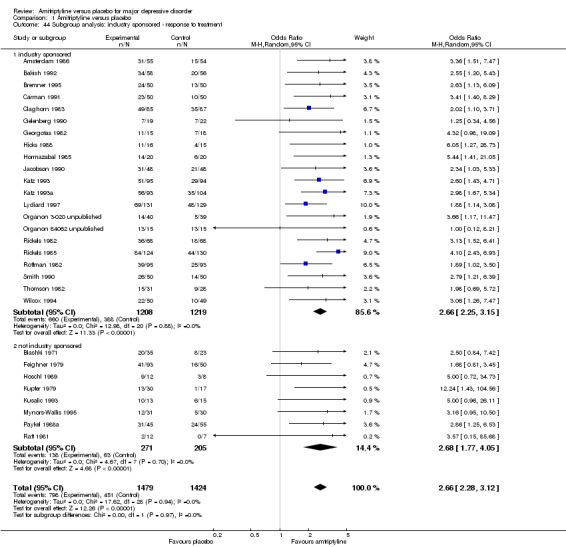

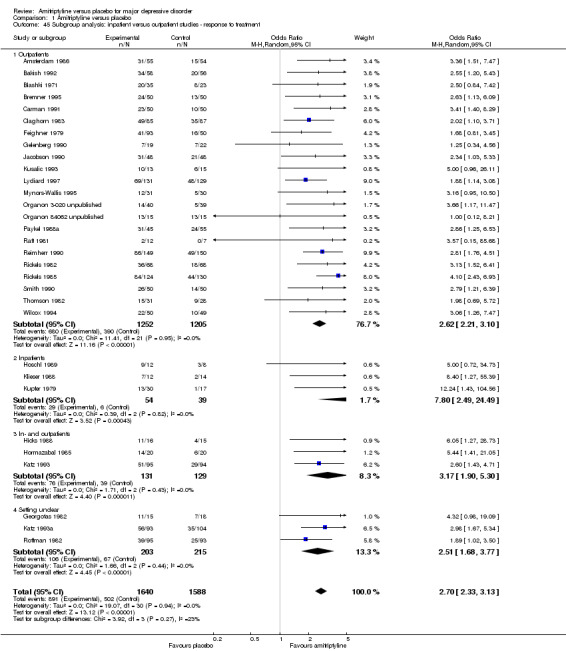

45. Subgroup analyses

There was no difference between industry‐sponsored and non‐industry‐sponsored trials (test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 0.00, df = 1 (P = 0.97), I² = 0%), inpatient versus outpatient studies (test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 3.92, df = 3 (P = 0.27), I² = 23.4), two‐arm versus three‐arm trials (test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 0.48, df = 1 (P = 0.49), I² = 0%). There were no data for the subgroup analysis comparing studies using operationalised criteria versus studies using ICD‐9 (Analysis 1.44; Analysis 1.45; Analysis 1.46).

1.44. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Amitriptyline versus placebo, Outcome 44 Subgroup analysis: industry sponsored ‐ response to treatment.

1.45. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Amitriptyline versus placebo, Outcome 45 Subgroup analysis: inpatient versus outpatient studies ‐ response to treatment.

1.46. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Amitriptyline versus placebo, Outcome 46 Subgroup analysis: two‐arms versus three‐arms studies ‐ response to treatment.

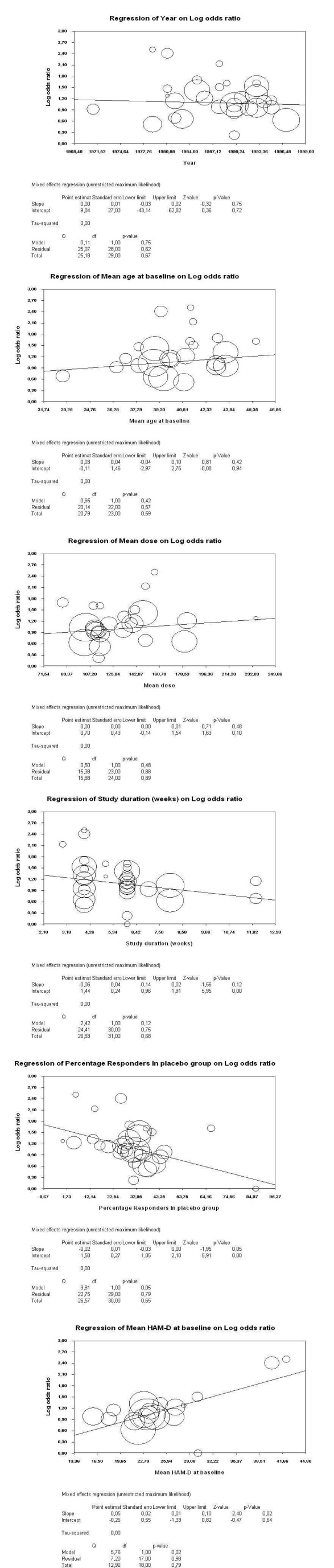

46. Meta‐regressions

The following potential effect moderators had no statistically significant effects on the primary outcome (for details see Figure 5): publication year (slope 0.00, 95% CI ‐0.03 to 0.02, P = 0.75), mean age at baseline (slope 0.03, 95% CI ‐0.04 to 0.10, P = 0.42), mean amitriptyline dose (slope 0.00, 95% CI 0.00 to 0.01, P = 0.48), study duration (slope ‐0.06, 95% CI ‐0.14 to 0.02, P = 0.12). Only higher depression severity at baseline as measured by the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM‐D) was associated with significantly higher drug efficacy (slope 0.05, 95% CI 0.01 to 0.10, P = 0.02). Higher percentage responder rates in the placebo groups were associated with almost statistically significant lower drug‐placebo differences (slope ‐0.02, 95% CI 0.01 to ‐0.03, P = 0.05).

5.

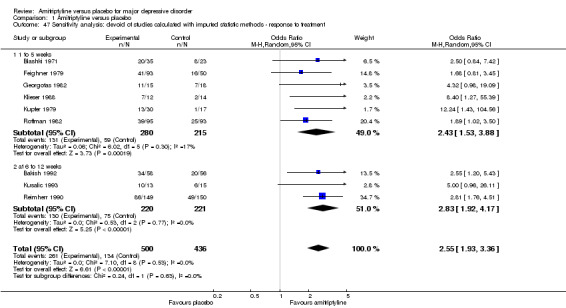

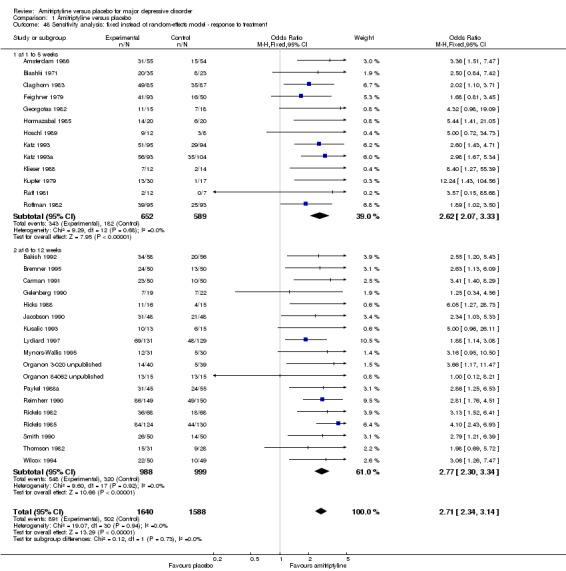

47. Sensitivity analyses

Excluding studies for which standard deviations had to be imputed (all studies pooled: OR 2.55, 95% CI 1.93 to 3.36, P < 0.00001, nine RCTs, 936 participants) and applying a fixed‐effect model rather than a random‐effects model (OR 2.71, 95% CI 2.34 to 3.14, P < 0.00001, 31 RCTs, 3228 participants) did not lead to any important changes in the primary outcome. The other preplanned sensitivity analyses did not apply (Analysis 1.47; Analysis 1.48).

1.47. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Amitriptyline versus placebo, Outcome 47 Sensitivity analysis: devoid of studies calculated with imputed statistic methods ‐ response to treatment.

1.48. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Amitriptyline versus placebo, Outcome 48 Sensitivity analysis: fixed instead of random‐effects model ‐ response to treatment.

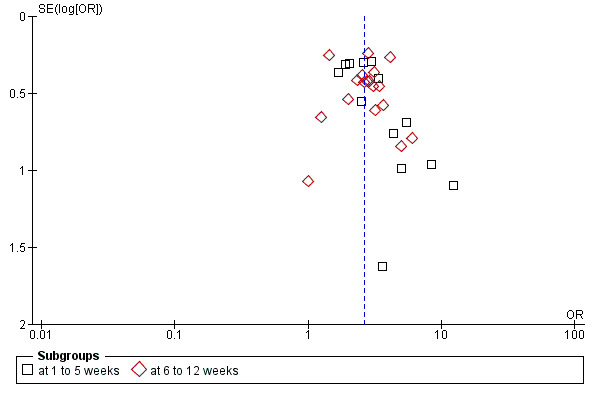

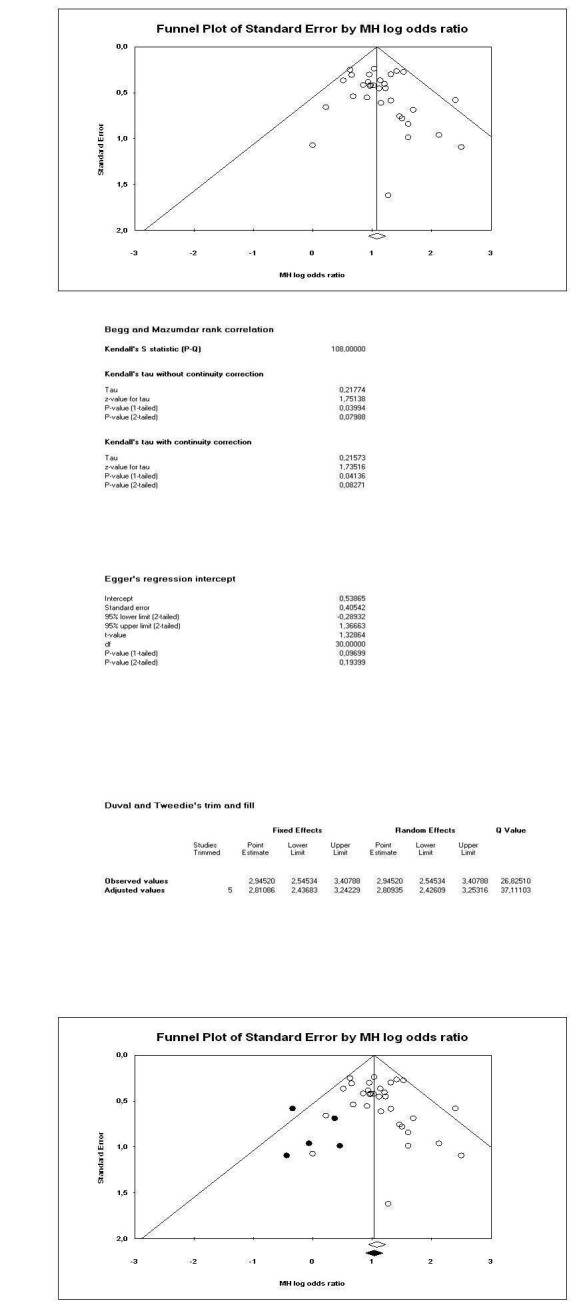

Publication bias

A funnel plot of the primary outcome (response to treatment) was asymmetrical (Egger's test was not significant, P = 0.19, but the trim and fill method (Duval 2000) suggested missing trials) suggesting that small studies may not have been published, especially in the one to five weeks category (Figure 6). When a trim and fill method was applied the adjusted relative risk (RR) did not, however, change much (RR 2.81, 95% CI 2.4 to 3.3; Figure 7).

6.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Amitriptyline versus placebo, outcome: 1.1 Response.

7.

Summary of findings

We judged the quality of the outcomes 'response to treatment' and 'overall tolerability' to be moderate, and that of 'acceptability of treatment' to be very low. No data on the other two a priori defined outcomes for the 'Summary of findings' table, 'death due to suicide' and 'quality of life', were available. Therefore, the quality of any recommendations for these outcomes also has to be rated as very low. We implemented these judgements in our interpretation of the findings (see below).

Discussion

Summary of main results

Amitriptyline is a classical tricyclic antidepressant, but its effects compared to placebo had to our knowledge not been assessed by a systematic review. This report, based on 39 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and 3509 participants, clearly demonstrated its efficacy for the acute treatment of major depressive disorder. The difference compared to placebo was considerable in the primary outcome, response to treatment (odds ratio (OR) 2.59 (95% confidence interval (CI) 2.03 to 3.29, I²= 0%) for early response, OR 2.67 (95% CI 2.21 to 3.23, I²= 0%) for acute‐phase response and OR 2.64 (95% CI 2.28 to 3.06, I²= 0%) when all studies were pooled). This means that 546 (95% CI 509 to 582) per 1000 amitriptyline‐treated participants would respond compared to 313 per 1000 placebo‐treated participants. This was corroborated by secondary outcomes such as number of participants in remission (OR 3.29, 95% CI 1.48 to 7.31, I²= 0%), mean reduction of depressive symptoms (standardised mean difference (SMD) ‐0.63, 95% CI ‐0.73 to ‐0.52, I²= 0%) or drop‐out due to inefficacy of treatment (OR 0.20, 95% CI 0.14 to 0.28, I²= 0%).

These results were robust to a number of effect moderators such as publication year (range 1971 to 1997), mean participant age at baseline, mean amitriptyline dose, study duration in weeks, pharmaceutical sponsor, inpatient versus outpatient setting and two‐arm versus three‐arm design. Concerning pharmaceutical sponsor it should be noted that in all studies the sponsor was either not the manufacturer of amitriptyline or if it was a third, newer antidepressant was the one of interest. In these cases amitriptyline was rather used as an active control in studies comparing a new compound with placebo. We nevertheless undertook this analysis, because even though the focus was the other antidepressant, the sponsors may have been biased to find superior outcomes for drugs compared to placebo. However, higher severity at baseline was associated with higher superiority of amitriptyline (P = 0.02), while higher responder rates in the placebo groups were associated with lower superiority of amitriptyline (just not meeting the conventional threshold of statistical significance, P = 0.05). As such our results confirm previous findings that antidepressants are more effective in more severely ill patients (e.g. Kirsch 2008). The result for placebo response is important because increasing placebo response has been identified as a major problem in recent antidepressant drugs trials (Walsh 2002). However, we highlight that meta‐regression is an observational (non‐randomised) method and that we undertook many meta‐regressions, raising the problem of multiple testing.

Results for acceptability of treatment as measured by dropping out of the studies for any reason suggested a superiority of amitriptyline (324 (95% CI 271 to 386) out of 1000 amitriptyline‐treated participants compared to 403 out of 1000 placebo‐treated participants would drop out), although there was heterogeneity and drop‐out due to any reason is also a very indirect measure of acceptability. Here, a superiority of amitriptyline in drop‐outs due to inefficacy appeared to have outweighed its inferiority in drop‐outs due to side effects.

The review also documented amitriptyline's well‐known side effects such as the various anticholinergic effects (constipation, dry mouth, nasal congestion, urination problems, vision problems), dizziness, sedation, tachycardia, sexual dysfunction and weight gain. The overall tolerability of amitriptyline was lower than that of placebo. According to the 'Summary of findings' table 165 out of 1000 amitriptyline‐treated participants compared to 45 out of 1000 placebo‐treated patients discontinued the studies due to adverse events.

As data on death were too rarely reported, this review could not clarify whether amitriptyline is associated with increased mortality due to side effects or whether it reduces mortality by preventing suicides. Moreover, there were virtually no data on outcomes that may be particularly important for patients such as quality of life and social functioning.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The available studies have been published in a variety of settings such as in hospitals and in outpatient clinics or in primary and specialised care making the results generalisable. Moreover, the primary outcome was not changed by various potential effect modifiers. The number of included studies (39) and participants (3509) should make the results rather robust, at least concerning the primary outcome. Trikalinos 2004 have shown that as a rule of thumb once 1000 participants have been included in a meta‐analysis, further trials are unlikely to change the effect size much. As a limitation, the two longest studies (Mynors‐Wallis 1995; Thomson 1982) lasted 12 weeks. Thus data for the predefined category 'follow‐up response' were not available. Moreover, we emphasise that much less information is available for secondary efficacy (e.g. remission) and tolerability outcomes. Without having original protocols available it is impossible to tell whether these outcomes were not measured or simply not recorded.

A funnel plot suggested a potential for publication bias although we undertook a thorough search to retrieve all relevant RCTs. This is not surprising because amitriptyline is a very old compound and serious attempts to limit publication bias have only been made in the last two decades. Indeed, some data on three unpublished trials were provided by a pharmaceutical company (Organon, manufacturer of mirtazapine), but manufacturers of amitriptyline either did not respond or did let us know that data on amitriptyline are no longer available. It is unlikely that only three studies have not been published in the last 50 years. Nevertheless, when the relative risk of the primary outcome was adjusted by the trim and fill method (Duval 2000) it did not change to a considerable degree.

Quality of the evidence