Abstract

The self-healing bioconcrete, or bioconcrete as concrete containing microorganisms with self-healing capacities, presents a transformative strategy to extend the service life of concrete structures. This technology harnesses the biological capabilities of specific microorganisms, such as bacteria and fungi, which are integral to the material's capacity to autonomously mend cracks, thereby maintaining structural integrity. This review highlights the complex biochemical pathways these organisms utilize to produce healing compounds like calcium carbonate, and how environmental parameters, such as pH, temperature, oxygen, and moisture critically affect the repair efficacy. A comprehensive analysis of recently published peer-reviewed literature, and contemporary experimental research forms the backbone of this review with a focus on microbiological aspects of the self-healing process. The review assesses the challenges facing self-healing bioconcrete, including the longevity of microbial spores and the cost implications for large-scale implementation. Further, attention is given to potential research directions, such as investigating alternative biological agents and optimizing the concrete environment to support microbial activity. The culmination of this investigation is a call to action for integrating self-healing bioconcrete in construction on a broader scale, thereby realizing its potential to fortify infrastructure resilience and sustainability.

Keywords: Self-healing bioconcrete, Microbial-induced calcite precipitation (MICCP), Biomineralization, Sustainable building materials, Fungal applications in concrete, Microbial spore encapsulation

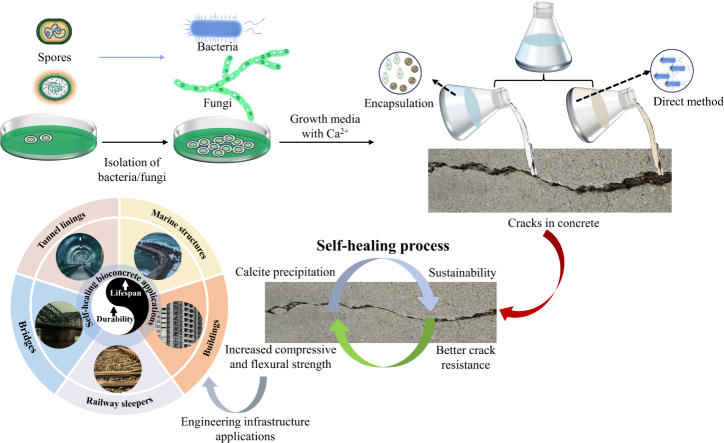

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Explored how microbes aided mineral-based self-healing in concrete.

-

•

Environmental factors critical to microbial concrete repair are detailed.

-

•

Integration of fungi and bacteria could offer a robust self-healing concrete strategy.

-

•

Cost and viability challenges of bioconcrete are assessed.

-

•

Insights on real-world application of bioconcrete are explored for future work.

1. Introduction

Concrete, recognized as a highly efficient and widely utilized construction material on a global scale, exhibits remarkable strength and cost-effectiveness in comparison to alternative building materials, thus facilitating its broad range of applications and meeting the increased demand driven by urbanization (Qureshi and Al-Tabbaa, 2020). Annually, over 4 billion tonnes of cement are produced, resulting in a per capita utilization of 560 kg (Shanks et al., 2019; Soysal et al., 2020). The focus on sustainability is critical since CO2 emissions are a major contributor to climate change and the current production of concrete is responsible for 8 % of global CO2 emissions and will need to be lowered by at least 16 % by 2030 to align with the Paris Agreement (Lehne and Preston, 2018; Sandak, 2023). The construction industry is, thus, seeking environmentally friendly solutions for concrete to reduce CO2 emissions and balance environmental responsibility with infrastructure reliability. Recently, research by Golewski and team have explored the use of mineral admixtures like fly ash (FA), silica fume (SF), and nanosilica (NS) to reduce reliance on traditional cement. These admixtures have been shown to affect crack development and, when combined, improve concrete's microstructure and strength (Golewski, 2024a, Golewski, 2024b). Furthermore, replacing some Portland cement with coal fly ash (CFA) has enhanced water resistance and durability, especially in submerged structures (Golewski, 2023a, Golewski, 2023b, Golewski, 2023d). Similarly, seawater-mixed pozzolanic-lime mortar (SMPLM) is another innovative material, using waste materials and seawater, that reduces CO2 emissions and is ideal for coastal construction due to its strength, durability, and self-healing properties (Yu and Zhang, 2023b). However, the complete replacement of cement or achieving complete sustainability in the cement industry is still far away.

Modern concrete infrastructure, such as dams, roadways, bridges, tunnels, and buildings, also require constant maintenance due to the generation of fractures caused by concrete deterioration. Cracks are common in concrete and masonry structures due to factors like tension, shrinkage, fatigue loading, seismic activity, and critical environmental factors including humidity, temperature changes, chemical exposure, wind velocity and biological growths (Golewski, 2023c; Qureshi and Al-Tabbaa, 2020). The limited tensile strength and vulnerability of concrete to microcracks compromise its structural integrity, durability, and design lifespan, which necessitates a sustainable solution (Golewski, 2023c).

Autogenic self-healing is one method for addressing these limitations and it is also known as intrinsic self-healing, occurs through the hydration of unhydrated cement within the concrete matrix (Qureshi and Al-Tabbaa, 2020; Rajczakowska et al., 2023). When cracks form in the concrete, water enters and triggers a chemical reaction that produces calcium carbonate (CaCO3). This CaCO3 effectively fills the microcracks in the concrete, typically ranging from 0.1 mm to 0.3 mm in size (Wiktor and Jonkers, 2011). Another method is autonomic self-healing, which involves incorporating unconventional materials and techniques into the concrete matrix (Fang et al., 2023). This approach can be achieved through encapsulation or the use of a continuous vascular system. Encapsulation methods involve creating a protective shell, usually made of glass or polymers, to house healing agents. These healing agents can be released when cracks occur, allowing the fluid-carrying compounds to diffuse and facilitate self-regeneration within the concrete. Vascularized systems, on the other hand, rely on a network of channels or tubes to distribute healing agents or activate microorganisms for repair purposes (Reeksting et al., 2019; Yu and Zhang, 2023b). Upon contact with water and nutrients, the dormant and encapsulated microorganisms get activated to begin microbially-induced mineralization (MIM) that produces CaCO3, promoting the self-healing of concrete fractures (Algaifi et al., 2021; Yu and Pan, 2023; Yu et al., 2023b; Zheng and Qian, 2020).

Thus, one of the promising techniques for developing self-healing bioconcrete involves using microorganisms as active repair agents. Researchers are continually investigating a range of techniques that rely on different metabolic processes exhibited by bacteria, such as polymorphic iron‑aluminum-silicate precipitation by Leuconostoc mesenteroides (Jonkers et al., 2010), biomineralization with microbially induced calcium carbonate precipitation (MICCP) (Algaifi et al., 2021), and bioencapsulation (Farmani et al., 2022) to achieve sustainable autogenous self-healing in concrete. Furthermore, fungi have also emerged as a potential alternative for self-healing bioconcrete applications (Van Wylick et al., 2021). Compared to bacteria, fungi demonstrate greater resilience in extreme environments and have simpler nutritional requirements to carry out mineral precipitation through both biomineralization and organomineralization processes. However, practical implementation challenges remain, such as improving the delivery and survival of microbial agents within concrete (Yu et al., 2023b).

Self-healing bioconcrete, particularly using bacteria that produce CaCO3 to fill cracks, is an emerging field aimed at extending concrete lifespan and reducing repair needs. Reviews by Aytekin et al. (2023), Bagga et al. (2022), Nodehi et al. (2022) and others have highlighted this area, noting the challenges in maintaining bacterial viability within concrete's harsh environment. Thus, this review paper focuses on the role of microorganisms in self-healing bioconcrete, examining the mechanism, benefits, and challenges of the self-healing approach. While most research has concentrated on bacteria, this paper also emphasizes the potential of fungi in self-healing concrete. It discusses various methods to protect and enhance the viability of microorganisms, like encapsulation and the use of spore-forming strains. The review also considers the application of advanced computational tools, such as artificial neural networks (ANN) and machine learning (ML), in optimizing the performance of microorganisms as self-healing agents, as underscored by Bagga et al. (2022).

2. Mechanism of self-healing bioconcrete by bacteria

Biomineralization and bioencapsulation encompass a variety of techniques that utilize biological processes for the self-healing and reinforcement of construction materials, leveraging the precipitation of minerals by microorganisms are discussed in subsequent sections. MICCP, a form of MIM, uses microorganisms to synthesize CaCO3, with its efficiency dependent on the temperature and pH changes, which influence microbial growth and enzyme (e.g., urease) activity (Yi et al., 2021). The resulting biogenic minerals effectively repair cracks, offering a self-healing solution for hard-to-reach structures like underground facilities and dams, where traditional repair methods are impractical (Yu et al., 2023b). Ongoing research aims to decode the intricate microbial influences on mineralization, broadening civil engineering possibilities. Notably, the application of soybean urease facilitates sandy soil stabilization through a marine-based MICCP, enhancing soil strength more efficiently than traditional methods by inducing CaCO3 and calcite magnesium precipitation (Yu and Pan, 2023). The efficacy of MICCP in seawater showcases its potential for remote marine infrastructure projects, with Sporosarcina pasteurii, adapted to seawater and ureolytic activity, being ideal for such applications (Yu and Rong, 2022). Research indicates its success in binding sand particles, serving as a biogenic reinforcement, and offering a sustainable, economical method for solidifying sandy foundations and creating materials for island and reef construction (Yu and Rong, 2022).

MICCP extends beyond concrete repair to environmental and soil stabilization, significantly reducing erosion on sandy slopes and enhancing soil geotechnical properties cost-effectively (Mujah et al., 2017; Xiao et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2024). While reviews on soil stabilization via MICCP are emerging (Ezzat, 2023; Prajapati et al., 2023; Tang et al., 2020), the microbiological details in self-healing bioconcrete remain scattered. Further expanding MICCP's potential, carbon-capturing bacteria like Paenibacillus mucilaginosus offer a low-carbon concrete alternative, promising for sustainable construction and climate mitigation (Yu and Zhang, 2023a). Moreover, sustainable practices include using steel slag waste to produce calcium acetate for MICCP, enhancing self-healing bioconcrete while avoiding chlorides, beneficial for reinforced concrete structures (Yu et al., 2023a). These innovations not only recycle industrial waste but also match or surpass traditional methods in performance.

2.1. Biomineralization

The precipitation of CaCO3 through MICCP is widely studied and considered an efficient method for mending concrete surface fractures and enhancing endurance (Fig. 1). MICCP is a biological process involving microbial activity and chemical reactions, which leads to the precipitation of CaCO3 through the interaction between microbial metabolic products (e.g., CO32−) and Ca2+ ions in the environment (Khushnood et al., 2020; Wiktor and Jonkers, 2011). In bacterial concrete precipitation, calcite and vaterite are the primary types of CaCO3 present. Research conducted by Algaifi et al. (2021) showed the complete healing of a 0.4 mm crack through the microbiological precipitation of calcite and vaterite. Calcite, in particular, offers attractive healing outcomes as it occupies less space in the bacterial cementitious material compared to vaterite, thanks to its higher density (Seifan et al., 2016a). Furthermore, the CaCO3 crystallization process for concrete healing involves anhydrous crystalline and hydrated crystalline polymorphs. The hydrated crystal polymorphs include calcium carbonate monohydrate (CaCO3·H2O) and calcium carbonate hexahydrate (CaCO3·6H2O) (Meldrum, 2013). Various common MICCP methods are employed, such as the use of bacterial urea amidohydrolase as a catalyst for urea hydrolysis, calcium salt-based MICCP, biological nitrate reduction, and photosynthesis.

Fig. 1.

Overview of the self-healing mechanism in concrete facilitated by microbial activity (Jin et al., 2018; Keren-Paz et al., 2022; Menon et al., 2019), accompanied by a range of biological self-healing methods (Chetty et al., 2023; Ersan et al., 2018; Seifan et al., 2016a, Seifan et al., 2016b) and approaches Endospore forming bacteria (Hungria et al., 2023; Mondal and Ghosh, 2021) applicable to different concrete structures.

2.1.1. Urea-based MICCP

The process of MICCP has been extensively studied in the context of bacteria-mediated urea (CO(NH2)2) hydrolysis (Dick et al., 2006; Naveed et al., 2020; Van Tittelboom et al., 2010). This approach is known for its high rate of CaCO3 precipitation and a significant increase in pH, which are key characteristics of urea-based MICCP (Erşan et al., 2016). The ability of bacteria to create an alkaline environment is considered their primary function in this process.

In the urea-based MICCP approach, urease (urea amidohydrolase) plays a crucial role in hydrolysing urea and producing ammonia (NH3) and CO32−, leading to an elevated pH within the ureolytic bacteria cell. Specifically, ureolytic bacteria present inside microcracks in the concrete accelerate the MICCP process by breaking down urea (i.e., CO(NH2)2 + H2O → NH2COOH + NH3) using urease to generate NH3 and carbamic acid (NH2COOH). The carbamic acid then spontaneously decomposes by carbonic anhydrase into NH3 (i.e., NH2COOH + H2O → NH3 + H2CO3) and carbonic acid (H2CO3), which further hydrolyses to form ammonium (NH4+) and hydroxyl ions (OH−) (i.e., 2NH3 + 2 H2O → 2NH4+ + 2OH−) (Castro-Alonso et al., 2019). The synergistic role of urease and carbonic anhydrase and its importance in urea hydrolysis and calcite formation has been highlighted by Dhami et al. (2014). The concentration of OH− inside the microcrack increases, resulting in an alkaline pH within the medium. This alkaline environment promotes the formation of CO32− (i.e., HCO3− + H+ + 2 OH− → CO32− + 2H2O) and bicarbonate ions (HCO3−) (i.e., H2CO3 → HCO3− + H+). Additionally, due to the negatively charged surfaces of the bacterial cell and the increased concentration of CO32− within the crack, the bacterial cell serves as a nucleation site for the heterogeneous precipitation of CaCO3 crystals (i.e., Ca2+ + CO32− → CaCO3). This facilitates the attraction of positively charged Ca2+ from calcium chloride (CaCl2) at a neutral pH to react with CO32−, inducing the precipitation of CaCO3 around the bacterial cell. Thus, in a saturated solution of dissolved Ca2+ and CO32−, CaCO3 precipitation occurs within the internal concrete environment, leading to the healing of the concrete crack. The importance of urease and carbonic anhydrase along with other factors including pH, calcium ions concentration, and availability of nucleation sites for rea-based MICCP have also been confirmed by Achal et al. (2011).

While this urea-based MICCP approach is considered highly effective among other mechanisms, it is important to note that it results in the continuous production of ammonium hydroxide (NH4OH). The high concentration of ammonium ions within the concrete environment can have detrimental effects on concrete, as it contributes to the leaching of calcium hydroxide, resembling an acid attack that reduces the durability and strength of the concrete (Soysal et al., 2020). Concrete samples with higher concentrations of NH4OH exhibit lower compressive strength, particularly in younger concrete, compared to standard concrete samples (Fawzi and Kareem, 2016).

2.1.2. Calcium salt-based MICCP

Certain aerobic bacteria oxidize organic calcium salts to produce energy and CaCO3, using oxygen as the final electron acceptor. The necessary calcium ions for MICCP are sourced from organic calcium minerals, such as calcium acetate (Ca(C2H3O2)2) (i.e., Ca(C2H3O2)2 + 4O2 → CaCO3 + 3CO2 + 3H2O) and calcium lactate (Ca(C3H5O3)2) (i.e., Ca(C3H5O3)2 + 6O2 → CaCO3 + 5CO2 + 5H2O). The microbial cells actively control the biomineralization process of CaCO3 (Keren-Paz et al., 2022). Wiktor and Jonkers (2011) found that a two-component self-healing agent, consisting of bacterial spores (e.g., Bacillus alkalinitrilicus) and calcium lactate, significantly increased CaCO3 precipitation on crack surfaces. This approach serves as a replacement for urea‑calcium chloride as a substrate for bacterial metabolism in concrete, avoiding the production of NH3 during hydrolysis.

Additionally, indirect CaCO3 precipitation from calcium lactate can occur through carbonation. When metabolically generated CO2 molecules combine with slaked lime (Ca(OH)2) (i.e., Ca(OH)2 + CO2 → CaCO3 + H2O) within the concrete matrix, it increases the amount of CaCO3 in the concrete cracks. This indirect generation of CaCO3 enhances the crack-healing ability of the concrete. The process also releases water, which promotes bacterial activity and cement hydration. This approach is considered a suitable alternative to urea-based MICCP as it does not produce harmful by-products like NH3. Moreover, it has the potential to utilize organic waste from industrial applications or fermentation processes (Xu et al., 2015).

2.1.3. MICCP through biological nitrate reduction

In contrast to urea hydrolysis and calcium organic salt oxidation, nitrate (NO3−) reduction occurs when bacteria use nitrate as the ultimate electron acceptor under anoxic conditions (Kamp et al., 2015). This process allows bacterial activity in environments lacking oxygen and leads to the deposition of CaCO3 in alkaline environments where calcium ions are present. Denitrifying bacteria like Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Diaphorobacter nitroreducens are capable of utilizing NO3− in oxygen-limited environments and thus have been studied due to their resistance to dehydration, nutrition starvation, and survival under alkaline conditions (Erşan et al., 2015). This process allows for continuous bacterial development without being hampered by limited oxygen availability, ensuring an effective and constant rate of CaCO3 precipitation.

Further, denitrifying bacteria derive their nutrition from calcium nitrate (Ca(NO3)2), which combines with calcium formate (Ca(HCOO)2) (i.e., 5Ca(HCOO)2 + 2Ca(NO3)2 → 7CaCO3 + 2 N2 + 3CO2 + 5H2O) present in the concrete, resulting in the formation of CaCO3, N2, CO2, and H2O (i.e., 2HCOO− + 2NO3− + 2H+ → 2CO2 + 2H2O + 2NO2) (Erşan et al., 2015, Erşan et al., 2016; Soysal et al., 2020). This mechanism leads to CaCO3 precipitation in the presence of Ca2+, regardless of the availability of OH−, by generating a significant amount of alkalinity (Erşan et al., 2016). Although the NO3− reduction pathway increases CaCO3, it can also produce NO2−, which functions as a corrosion inhibitor. However, it has been observed that high levels of CaCO3 precipitation can still be achieved using only Ca(HCOO)2 and Ca(NO3)2, making the process practical for self-healing bioconcrete. Recently, Ersan et al. (2018) reported 70 % healing of cracks larger than 400 μm by using special granules called “activated compact denitrifying core”. However, it is reported that ureolysis have more efficiency of CaCO3 precipitation (<0.5 mm) than denitrification (Castro-Alonso et al., 2019).

2.1.4. MICCP through photosynthesis

Bacteria employ both autotrophic and heterotrophic CO2 absorption routes to facilitate MICCP (Castro-Alonso et al., 2019). Cyanobacteria play a crucial role in CO2 precipitation through the extracellular media generated during photosynthesis. During photosynthesis, cyanobacteria utilize a biochemical CO2-sequestering mechanism to concentrate CO2 intracellularly, leading to the creation of an alkaline environment (i.e., CO2 + H2O → H2CO3) surrounding the bacterial cell. This alkaline environment, in turn, induces oversaturation in the thin aqueous layer surrounding the bacteria, providing carbonate nucleation sites within the bacterial envelope. As a result, CaCO3 precipitation is initiated when Ca2+ is present (i.e., Ca2+ + 2H2CO3 ⇆ CaCO3 + CO2 + H2O), occurring outside the bacterial cell. In heterotrophic cyanobacteria, the carbonic anhydrase enzyme plays a vital role in facilitating the hydration of CO2, effectively reducing ambient CO2 levels. Through these reactions, cyanobacteria efficiently capture and utilize CO2, facilitating the formation of CaCO3 and contributing to carbon sequestration and storage (Kaur et al., 2016; Zhu et al., 2015). However, the MICCP through photosynthesis can only be achieved when the structures/cracks are exposed to sunlight and CO2, as part of basic requirement for the photosynthesis process which limits its application (Seifan et al., 2016a, Seifan et al., 2016b).

2.1.5. MICCP through dissimilatory sulfate reduction

Sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB) under anaerobic conditions can also indirectly form CaCO3 minerals in the presence of calcium and organic matter via dissimilatory sulfate reduction pathway. Perito and Mastromei (2011) successfully demonstrated the precipitation of CaCO3 from gypsum (CaSO4·H2O) via sulfate reduction by using Desulfovibrio sp. Few studies have shown that significant increase in compressive and flexural strength and decrease in water permeability of the concrete after the inclusion of SRB into the matrix of concrete (Alshalif et al., 2016; Tambunan et al., 2019). However, H2S produced during the process can also lead to the corrosion of the concrete structure and needs further studies on it (O'connell et al., 2010). Co-culture of SRB with cyanobacteria have also improved the CaCO3 precipitation significantly and can be a promising candidate in the bioconcrete industry. Similarly, Chetty et al. (2023) recently successfully demonstrated the application of integrating granules of SRB with nitrate reducing bacteria for self-healing bioconcrete technology in long-term. However, co-culturing methods necessitates further research on the synergistic and antagonistic impact of two different cultures before its large-scale application.

2.1.6. Emerging MICCP approaches

Innovative techniques like carbonic anhydrase-producing bacteria (CAB) for CO2 sequestration in building materials and Streptomyces-induced calcite precipitation (SICP) for soil stabilization, are at the forefront of eco-friendly technology advancements. CAB facilitates the conversion of CO2 into sustainable building materials through MICCP, producing carbonic anhydrase (CA) which catalyzes the formation of bicarbonate ions. These ions combine with calcium and magnesium to form CaCO3, a vital concrete component, thus aiding in CO2 hydration and sequestration (Qian et al., 2022; Yu and Xu, 2023; Zheng and Qian, 2020). Bacillus mucilaginosus was found to be an ideal candidate for this process, converting CO2 into carbonates, reducing greenhouse gases, and enhancing concrete durability (Qian et al., 2022). This biological approach offers an eco-friendlier alternative to conventional CO2 capture methods like urea hydrolysis, which yields toxic byproducts (Yu and Xu, 2023). CAB technology also promotes the reuse of materials such as steel slag and crushed concrete, contributing to the circular economy in construction. Steel slag reacts with CO2 to form carbonates, and recycled concrete aggregates benefit from enhanced properties due to CAB action, leading to stronger and more durable concrete structures (Qian et al., 2022).

Additionally, SICP represents an eco-friendly method for soil stabilization, reducing ammonia emissions compared to traditional MICCP. SICP involves introducing Streptomyces bacteria to soil, promoting in-situ calcite synthesis which enhances soil strength while maintaining water permeability, offering a sustainable solution for soil reinforcement in construction (Xu et al., 2021).

2.2. Bioencapsulation

During the concrete curing, as the cement hydration takes place, the viability and metabolisms of microorganisms in the concrete could be drastically reduced due to exposure to extreme environmental factors such as pressure, temperature, oxygen availability, salinity, and pH (Ivaškė et al., 2023). The optimal temperature and pH levels are crucial for bacterial viability and growth; most bacteria will fail to thrive or perish outside these ranges, with the notable exception of spore-forming bacteria, which can withstand more extreme conditions (Kim et al., 2021). The availability of oxygen, vital for bacterial viability, also varies within the concrete structures depending on their geographical location.

For example, ureolytic bacteria can't be used as a self-healing microorganism in an underwater concrete structure due to oxygen limitation, but anaerobic bacteria like denitrifying bacteria could be used in underwater or marine concrete structures (Zhang et al., 2017a). Zhang et al. (2016) employed a mixer of oxygen-releasing tablet and calcium peroxide (CaO2) to ensure oxygen availability for maintaining bacterial viability and metabolisms inside the concrete structure which successfully maintained the required oxygen level and viability of bacteria and enhanced MICCP in the concrete for 35 days. The selection of suitable bacteria is essential for effective self-healing in concrete, taking into account environmental factors that affect bacterial survival and metabolism. Researchers are exploring various strategies such as employing endospore-forming bacteria and techniques like encapsulation and immobilization to enhance the durability of microorganisms in harsh conditions for better self-healing bioconcrete.

2.2.1. Endospore-forming bacteria

Bacteria have the ability to transition from an active state to a dormant state by forming spores in response to adverse environmental conditions such as lack of nutrients, unfavorable pH, or temperature (Farmani et al., 2022). When the interior environment of concrete becomes suitable for bacterial growth and survival, these spores revert back to the active vegetative stage. This reactivation allows the bacteria to carry out their crucial role in precipitating CaCO3, which aids in the healing of concrete cracks (Fig. 1). The presence of bacterial spores is vital for the self-healing of cementitious materials, as it enables them to withstand challenging environmental conditions, mechanical stress, and chemical exposure during concrete production and restoration (Wang et al., 2014b). Several studies have successfully explored various spore-forming Bacillus strains, such as B. subtilis, B. sphaericus, B. cereus B. megaterium, etc., calcite precipitation and self-healing of concrete (Andalib et al., 2016; Maheswaran et al., 2014; Mondal and Ghosh, 2021). Recently, Shaheen et al. (2023) compared the spore and non-spore forming bacteria for self-healing bioconcrete technology. Although, the non-spore forming bacteria (e.g., Arthrobacter luteolus, Chryseomicrobium imtechense and Arthrobacter luteolus, Chryseomicrobium imtechense and Corynebacterium efficiens) shows great potential for healing the concrete, spore-forming Bacillus strains exhibit higher compressive and tensile strength compared to the non-spore forming bacteria because of their spore-forming capability. In contrast, non-spore-forming Deinococcus radiodurans was compared with spore-forming B. subtilis for the for self-healing of concrete technology by Mondal and Ghosh (2021) and results shows that biomineralization and the mechanical properties of MICCP of D. radiodurans was at par with spore-forming bacteria in a favorable as well in unfavorable environment.

However, addition of bacteria directly into the concrete can drastically reduce the metabolic activities of the microorganisms (Farmani et al., 2022). To enhance the survival rate of bacterial spores in the extreme environmental condition for longer duration, they can be encapsulated along with organic minerals within porous expanded clay particles prior to incorporation into the concrete matrix (Farmani et al., 2022). During the preparation of the concrete, the bacterial spores are encapsulated inside a protective carrier, such as microcapsule, polymer etc. which can protect the spores from the high pH and other environmental limitations inside the concrete. But importantly, the carriers should easily burst out and release the spores to be metabolically active and precipitate CaCO3 as soon as the cracks appear for self-healing of the cracks in the concrete. However, this approach is limited by the internal environment of the concrete, as bacteria are sensitive to their surroundings and require favorable conditions to adapt.

The encapsulating capsules possess a flexible nature in wet or humid environments but become brittle when exposed to dry conditions (Algaifi et al., 2021; Wiktor and Jonkers, 2011). For instance, Jonkers et al. (2010) developed a two-part self-healing system comprising bacterial spores and organic components. The spore germination triggers the conversion of organic molecules, resulting in the production of CaCO3. Bacterial spores and organic molecules were incorporated into fresh concrete, becoming a permanent constituent. The study also demonstrated that the presence of bacteria and specific organic calcium salts, such as calcium lactate, did not adversely affect the compressive strength of the concrete. Hydrogel, a polymer-based material, has also been used extensively for encapsulation of bacteria in self-healing bioconcrete process (Hungria et al., 2023). However, being soft in nature, hydrogel poses lesser strength than concrete and poor volume stability leading to reduction in the size of the capsule and compromising the strength of the matrix. In addition, alkaline components also get absorbed into the hydrogel capsule from the cement matrix which can seriously impact the viability of bacterial spores suggesting that hydrogel only impart partial protection to the bacterial spores inside the capsule (Xiao et al., 2023).

Recently, Xiao et al. (2023) applied MgO-SiO2 based encapsulation methods of bacterial spores for self-healing bioconcrete with an 85–97 % healing of large cracks ranging between 250 and 600 μm and shown better results than hydrogel encapsulation. The capsule shows long-term stability of the viable bacterial spores within the capsule but needs further research on the compatibility and efficiency of the capsules in other cementitious matrix (e.g., geopolymer). Similarly, Pungrasmi et al. (2019) successfully demonstrated the microencapsulation of Bacillus sphaericus LMG 22257 with sodium alginate and its application in self-healing bioconcrete technology. Study also reveals that among the three methods including spray drying, extrusion, and freeze drying for encapsulation of the bacterial spores, freeze-drying shown the most promising results as it was more readily broken when the cracks appear in the concrete. In opposite, the encapsulated spores weren't release due to the rigidity of the capsules formed via spray drying or extrusion techniques which clearly suggests that a proper encapsulation method is equally important for this technology to protect the bacterial spores and release the spores when required.

2.2.2. Bacterial immobilization

The mechanism of bioencapsulation involves immobilizing bacterial cells in carriers such as silica gel, polyurethane, hydrogel, and microcapsules (Wang et al., 2014a). This approach differs from bioencapsulation using bacterial spores, as it involves immobilizing the bacterial cells instead of releasing them into the concrete crack. The goal of both techniques is to minimize the inhibitory effects of concrete on bacterial growth, although their methods differ. For example, polyurethane-encapsulated bacterial cells are well-protected in the harsh internal concrete environment, exhibiting a 30 % breakdown of urea after 72 h. On the other hand, scoria aggregates, as bacterial carriers, interact better with concrete and promote greater CaCO3 precipitation due to significantly higher bacterial growth. The immobilized bacterial cells in scoria aggregates show increased urease activity, breaking down over 50 % of urea within the same time frame (Farmani et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2014a). The application of porous protection carriers like expanded clay particles, granular activated carbon, or zeolite, in combination with bacteria and nutrients, does not affect the physical qualities of concrete. Moreover, these protection carriers are suitable for preserving bacteria even at pH 13 (Erşan et al., 2016).

Further, the research conducted by Kawaai et al. (2022) focused on crack and patch repair in concrete using Bacillus subtilis. They developed alginate-based self-healing materials that improve crack tightness and reduce water absorption. Calcite precipitation within gel films demonstrated the material's effectiveness in sealing cracks. Similarly, Xu et al. (2018b) reported a significant increase in compressive strength in self-healing bioconcrete structure after 28 days when B. subtilis was immobilized in sodium alginate capsules. Pungrasmi et al. (2019) observed a similar enrichment in the viability of B. sphaericus LMG 22257 when encapsulated in sodium alginate, which in turn augmented the self-healing efficiency of concrete. Microencapsulation of B. pseudofirmus and B. halodurans spores in calcium alginate also showed improved viability into the cement mortar during 56 days of cement hydration period (Ivaškė et al., 2023). In contrast, Jakubovskis et al. (2022) reported that bacterial viability decreased drastically (>10-fold) in concrete structure during curing at 80 °C when expanded clay was used as a carrier material for microorganism. But, recently, the application of commercial air-entraining admixtures has been successfully demonstrated by Justo-Reinoso et al. (2022) for encapsulation of B. cohnii endospores and the viability of the self-healing microorganisms was maintained for over nine months in self-healing cementitious composites.

3. Mechanism of self-healing bioconcrete by fungi

3.1. Biomineralization by fungi

The ability of fungi to survive, reproduce, and thrive in harsh environments makes them promising candidates for the development of self-healing bioconcrete than bacteria (Jin et al., 2018; Menon et al., 2019). Fungi demonstrate remarkable tolerance to a range of extreme conditions, including low humidity, variations in temperature, UV radiation, nutrient scarcity, and high alkalinity, with pH levels exceeding 10 (Magan, 2007). They are equipped with an osmotic barrier that enables them to maintain an internal cellular pH close to neutral despite being in highly alkaline external environments. Fungi, particularly filamentous types, have been observed to facilitate CaCO3 precipitation more rapidly than bacteria, as reported by Jin et al. (2018). This is partly due to their superior cell wall-binding capacity and remarkable metal-uptake capability, enhancing their effectiveness in biomineralization-based technologies. The abundance of nucleation sites, such as cell walls, is a critical factor influencing the quantity of precipitated minerals.

Fungi (e.g., Aspergillus) metabolize organic substrates and produce organic acids, such as oxalic, citric, gluconic, and lactic acids as by-products (Liaud et al., 2014). These organic acids can lower the local pH around the fungal hyphae, creating an acidic microenvironment. The produced acids react with Ca2+ ions in the concrete or from added calcium sources (e.g., calcium lactate, calcium chloride). Other acids can promote the precipitation of CaCO3 by providing a local source of CO32− ions through subsequent metabolic reactions. Some fungi (e.g., Mucor or Rhizopus) produce carbonic anhydrase, an enzyme that catalyzes the hydration of CO2 to H2CO3, which subsequently dissociates into HCO3− and CO32− ions. CO32− ions then react with Ca2+ ions to precipitate CaCO3 (Occhipinti and Boron, 2019). This occurs particularly in alkaline conditions, such as those found in concrete. Other fungi such as Aspergillus or Penicillium produce urease, which hydrolyzes urea into NH3 and CO2. The increase in pH due to ammonia formation promotes carbonate precipitation. CO2 reacts with water to form H2CO3, which dissociates into HCO3− and CO32− ions. These ions then precipitate with Ca2+ to form CaCO3 (Bindschedler et al., 2016).

The unique growth patterns, structural architecture, and development of an extensive branching network by filamentous fungi provide numerous nucleation sites, thereby supporting more efficient CaCO3 precipitation (Luo et al., 2018). The rate of precipitation is influenced by the concentrations of Ca2+ ions and carbonate alkalinity (Van Wylick et al., 2021). Fungal metabolisms have the capacity to affect both of these factors. They modulate water consumption, organic acid oxidation, nitrate assimilation, urea degradation, and the physicochemical release of CO2 through respiration that increase alkalinity. Additionally, fungi can alter Ca2+ ion concentrations by actively transporting them out of the cell or by binding them to cytoplasmic proteins, as detailed by Bindschedler et al. (2016). These mechanisms enable fungi to precipitate larger quantities of CaCO3 more quickly than bacteria.

3.2. Organomineralization by fungi

Fungi can induce the precipitation of CaCO3 through organomineralization, a process that relies on an organic substrate to initiate or enhance crystal nucleation and growth (Jin et al., 2018). In this scenario, living organisms are not necessary; rather, the organic fraction serves as a template for nucleation. The chitin present in fungal cell walls lowers the activation energy required for nucleus formation (Jin et al., 2018; Roncero, 2002), resulting in significantly reduced interfacial energy between the fungi and the mineral crystal compared to that between the mineral crystal and the surrounding solution. In this context, cations can bind passively to the cell walls in a metabolism-independent manner (Ehrlich, 2010). This implies that the process can remain effective even when the biomass is deceased, offering a significant advantage for sustained concrete restoration.

Fungal cell walls, along with extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) produced by fungi, can adsorb Ca2+ in high concentrations. This adsorption is a critical first step for the nucleation of CaCO3 crystals, leading to organomineralization (Bindschedler et al., 2016). EPS, including proteins, polysaccharides, and lipids, create a matrix that facilitates mineral deposition and acts as a scaffold for the nucleation of mineral particles. Fungal hyphae and EPS provide nucleation sites where mineral ions can accumulate and initiate crystallization. Once nucleation occurs, minerals such as CaCO3 or calcium oxalate grow within the organic matrix, effectively filling and sealing cracks in the concrete. Numerous studies have confirmed the potential of fungi for use in self-healing bioconcrete technologies through both biomineralization and organomineralization with live or dead biomass (Bindschedler et al., 2016; Burford et al., 2006; Sanyal et al., 2005).

Rhizopus can produce EPS that facilitates the nucleation and growth of calcium-based minerals, contributing to the organomineralization process and enhancing the self-healing capability of concrete (Khushnood et al., 2022). It was demonstrated that Rhizopus oryzae healed the maximum crack width of 0.6 mm, which increased to 1.3 mm on immobilization through calcium alginate beads. Besides wild-type fungal strains, genetically engineered fungi with high pH regulatory capabilities are also important candidates for self-healing bioconcrete. In this case, the mutation in the pacC regulatory gene is desired since it bypasses the need for the extracellular pH signal which results in the permanent activation of alkaline genes (Penalva et al., 2008). The overview of fungi identified as promising candidates for self-healing bioconcrete is presented in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Representative images of fungal cultures with biomineralization or organomineralization capacity: a petri dish showing growth patterns (inner circle) and a corresponding microscopic image of the culture (outer circle).

(Photo credit: Prof. Polona Zalar, strains sourced from the Microbial Culture Collection Ex.)

4. Factors affecting the effectiveness of self-healing bioconcrete

Several microorganisms have been studied for their ability to heal concrete cracks through various mechanisms under different environmental conditions, such as pH, temperature, oxygen availability, moisture content, microbial load, the kinetics of CaCO3 deposition, and the dimensions of cracks (Fig. 3). Among the mechanisms, the urea-based MICCP strategy using ureolytic bacteria has gained popularity (Table 1). However, the efficacy of this method may not be consistently high. When bacteria are encased within a spore or a carrier, they typically show a more robust crack-healing performance than those that are not encapsulated. For instance, Bacillus cohnii, protected by a bacterial carrier, can repair a concrete crack with a width of 0.79 mm, highlighting the enhanced healing ability of well-protected bacteria (Han et al., 2022). Bacterial protection is crucial to significantly enhance the effectiveness of self-healing bioconcrete technology (Soysal et al., 2020). The best healing outcome is achieved by B. sphaericus LMG 22557 bacteria, which underwent urea-based MICCP while protected by a bacterial spore. These bacteria can close a 0.97 mm concrete fracture after 8 weeks of submersion (Amran et al., 2022). Additionally, encapsulating Bacillus subtilis with carriers significantly increases healing efficacy compared to direct injection into the crack, with healing of 0.81 or 0.60 mm of the crack observed. This demonstrates that autogenous MICCP pathways have limitations, as the maximum fracture width treatable through autogenous healing approaches ranges between 0.1 and 0.3 mm, depending on environmental conditions (Wiktor and Jonkers, 2011).

Fig. 3.

Influence of crack dimensions (Muhammad et al., 2016), pH (Algaifi et al., 2021), temperature (Okwadha and Li, 2010), oxygen, moisture (Tan et al., 2023), and calcite deposition rates (Mondal and Ghosh, 2018) on microorganism-mediated self-healing in concrete.

Table 1.

Overview of microorganisms, healing mechanisms, and bioconcrete restoration results.

| Microorganisms | Mechanisms | Outcomes | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacillus sphaericus | Bioencapsulation | Mended cracks and fissures, ranging from 0.15 to 0.17 mm and 0.5 mm in width, respectively, with the latter filled after 7 days. | (Wang et al., 2012) |

| Bacillus cohnii | Bioencapsulation | Repaired the concrete crack with a width of 0.79 mm. | (Zhang et al., 2017b) |

| Sporosarcina pasteurii ATCC11859 | Urea-based MICCP with bioencapsulation | Filled a 0.86 mm crack in 28 days. | (Xu and Wang, 2018) |

| Bacillus cereus | Urea-based MICCP with bioencapsulation | Able to seal concrete cracks with widths between 0.162 mm and 0.670 mm effectively. | (Sohail et al., 2022) |

| Bacillus megaterium | Urea-based MICCP with bioencapsulation | Plugged a crack with a width of 0.3 mm after 91 days. | (Kawaai et al., 2022) |

| Bacillus pseudomycoides strain HASS3 | Urea-based MICCP | Repaired a crack with a width of 0.4 mm after 68 days. | (Algaifi et al., 2021) |

| Bacillus sphaericus LMG 22557 | Urea-based MICCP with bacterial spore-based bioencapsulation | Cracks of 0.97 mm wide were repaired in eight weeks; 48 %–80 % of surfaces healed with nutrients and 3 %–5 % with encapsulated bacterial spores. | (Wang et al., 2014a, Wang et al., 2014b) |

| Bacillus subtilis | Bioencapsulation by bacteria carrier ad organic salt oxidation | Bacteria carrier graphite nanoplatelets heal fractures up to 0.81 mm, while lightweight aggregates heal up to 0.60 mm. | (Khaliq and Ehsan, 2016) |

| Bacillus subtilis PTCC 1254 | Organic salt oxidation | Efficiently sealed fractures with a maximum width of 0.2 mm. | (Kalhori and Bagherpour, 2017) |

| Bacillus alkalinitrilicus | Organic salt oxidation and bioencapsulation by bacteria spore | Sealed concrete cracks up to 0.46 mm after 100 days, more than doubling the control's healing width of 0.18 mm. | (Wiktor and Jonkers, 2011) |

| Diaphorobacter nitroreducens | Nitrate (NO3−) reduction | Achieved over 90 % sealing of cracks up to 0.35 mm within 14 days, and post 14 days, secured 100 % closure for cracks under 0.35 mm and over 90 % for those between 0.35 mm and 0.40 mm. | (Erşan et al., 2016) |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | NO3− reduction | Outperformed abiotic control in healing cracks over 0.30 mm, effective in 0.35 to 0.40 mm crack widths. | (Erşan et al., 2016) |

| Synechococcus PCC8806 | Photosynthesis | Bacterial concrete exhibited a 0.200–0.270 mm precipitated layer, surpassing the abiotic control's 0.115 mm maximum by 38 % in calcium precipitation. | (Zhu et al., 2015) |

| Aspergillus nidulans (MAD1445), Fusarium oxysporum, Trichoderma reesei | Biomineralization | Grew on concrete plates and promoted CaCO3 precipitation. | (Luo et al., 2018) |

| Neurospora crassa, Penicillium chrysogenum CS1 | Urea-based MICCP | Produced biosandstone in 14 days through CaCO3 precipitation with urea. | (Martuscelli et al., 2020) |

| Rhizopus oryzae | Biomineralization | Repaired a 0.6 mm crack, expanding to 1.3 mm upon immobilization with calcium alginate beads. | (Khushnood et al., 2022) |

| Fusarium cerealis, Phoma herbarum, Mucor hiemalis | Urea-based MICCP | Fungi's ability to generate carbonate concrete coatings and immobilize toxic strontium. | (Zhao et al., 2022a) |

| Neurospora crassa | Urea-based MICCP | Fungi biomineralization observed following a 12-day incubation at 25 °C in a medium containing urea and calcium. | (Li et al., 2014) |

4.1. pH and temperature

The healing performance is affected by pH levels as extreme pH impedes bacterial survival, enzymatic activity, and metabolic healing functions. For instance, the pH level within concrete is pivotal for the urea-based MICCP process, affecting urease enzyme function, CaCO3 precipitation by ureolytic bacteria, and the bacteria's movement, adhesion, and even distribution of CaCO3 precipitates, with fracture healing efficiency depending on the availability of OH− ions (Erşan et al., 2016). Ureolytic bacteria pivotal to the MICCP process are typically heterotrophic facultatives that thrive under alkaline conditions where their metabolic functions increase pH, aiding in the precipitation of CaCO3 and also ureolytic bacteria, including halophiles and alkaliphiles can produce bioconcrete at pH levels ranging from 8.5 to 11 (Soysal et al., 2020; Stabnikov et al., 2013).

For instance, Sporosarcina pasteurii, an ureolytic bacteria, hydrolyzes urea best at pH 9.25 and cease to grow beyond pH 10 (Okwadha and Li, 2010). Another study by Wu et al. (2019) showed that growth and biomineralization ability of Bacillus cereus at pH 7 to 12 and found its effectiveness declines at pH levels above 10. Algaifi et al. (2021) state that a pH below 12 in the crack zone favors spore germination, bacterial growth, and carbonate ion production, thus accelerating CaCO3 precipitation. Conversely, Wang et al. (2014b) found that at pH levels above 12, bacterial transition from spores to active cells ceases, reducing bacterial healing activity, despite spores remaining dormant and protected. Further, Higgins and Dworkin (2012) suggest that the bacterial spores can revert to active vegetative cells when conditions improve, highlighting that while ureolytic bacteria function well in moderately high pH, extreme pH levels are detrimental. Thus, Javeed et al. (2024) and Su et al. (2021) indicate that reducing the lag phase of bacteria in highly alkaline conditions is crucial, suggesting pH optimization or isolating alkaline-tolerant bacteria is key for self-healing bioconcrete technology.

Similar to bacteria, several fungal species can thrive in alkaline conditions, where pH values often hover around 10. The biomineralization process, mediated by MICCP is influenced by the extracellular calcium concentration and the alkaline pH, which also affects the availability of dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) and carbonate ions (Dhami et al., 2013). It has been shown that bacteria play a crucial role in creating an alkaline environment conducive to CaCO3 biomineralization (Dhami et al., 2014), a similar mechanism was also observed in the fungus Colletotrichum acutatum (Li et al., 2018). Effective biomineralization among fungal species has occurred at pH levels as low as 8. For example, fungi such as Paecillomyces lilacinus and certain Chrysosporium spp. can flourish in pH ranges from 7.5 to 11.0 without inhibition (Magan, 2007). Additionally, fungi can maintain near-neutral internal cellular pH despite external alkaline conditions due to an osmotic barrier, allowing them to inhabit extremely alkaline environments such as soda lakes and springs. These environments are prime candidates for sourcing fungi for self-healing bioconcrete technology applications (Jin et al., 2018).

Temperature is another critical factor that affects the healing efficacy of bacteria in concrete. It influences bacterial growth, enzymatic activity, and precipitation rates, with higher temperatures promoting faster CaCO3 precipitation due to increased molecular interactions and enzymatic reactions (Okwadha and Li, 2010). Conversely, low temperatures can prolong the lag phase of bacterial growth and slow down ureolytic activity, as evidenced by the extended lag period for Bacillus cereus CS1 at 10 °C compared to higher temperatures (Wu et al., 2019). While extreme heat can denature bacterial enzymes and reduce activity, some Bacillus species (e.g., B. subtilis, B. cereus, B. licheniformis, and B. halodurans), notably B. cereus exhibits robust growth even at 60 °C while B. subtilis showed an optimal growth range between 30 °C and 37 °C (Durga et al., 2021). For calcite precipitation and self-healing efficacy, 40 °C has been identified as the optimum temperature for B. thuringiensis ATCC 33679 (Njau et al., 2022).

On the other hand, fungi display remarkable adaptability to extreme environmental conditions, including sporulation in response to temperature fluctuations, pH levels, and nutrient scarcity. While predominantly mesophilic, fungi can also grow in sub-zero conditions, as seen in Antarctica, or in temperatures exceeding 40 °C (Magan, 2007; Robinson, 2001). This resilience suggests that further exploration of extremophilic fungi could greatly enhance the long-term self-healing capabilities of concrete, an area currently underexplored.

4.2. Oxygen and moisture content

Oxygen is essential for aerobic bacteria in concrete, as they use it to oxidize organic salts and produce CaCO3, crucial for repairing cracks in self-healing bioconcrete. The presence of oxygen and water is not always guaranteed following a crack, but they are vital for bacterial spore germination and proliferation, leading to CaCO3 deposition (Soysal et al., 2020; Tan et al., 2023). Bioconcrete benefits from wet-dry cycles; oxygen levels during dry cycles enhance bacterial activity and CaCO3 formation (Tziviloglou et al., 2016). Oxygen consumption in bioconcrete indicates active bacteria, with higher concentrations leading to more effective crack repair due to increased aerobic metabolism and CaCO3 accumulation (Wiktor and Jonkers, 2011). Oxygen levels within bioconcrete affect the activity of bacteria in cracks, leading to more CaCO3 production and better crack repair.

Water is equally crucial, necessary for biochemical reactions in MICCP processes, and for bacterial spores to germinate and fill cracks (Shanks et al., 2019; Soysal et al., 2020). Without water, bacterial healing is limited, as observed by Wang et al. (2014b), who found that concrete without water showed no healing, whereas samples with water did. Similarly, Tan et al. (2023) confirmed that B. cohnii DSM 6307 requires both oxygen and wet conditions for effective crack healing. On the other hand, fungi typically found in aerobic environments, can also survive extreme conditions by forming spores, suggesting potential for their use in industrial self-healing bioconcrete applications (Gadd, 2021). Thus, oxygen limitation and moisture deficit can be overcome by the production of spores, that allow them to survive in this dormant state for long periods, waiting for more favorable conditions which necessitate probing deeper into the prospect of screening fungi from the extreme environment to boost the industrial application of self-healing cracks in the concrete.

4.3. Cell concentration

The healing performance of bioconcrete improves with higher bacteria concentrations. According to Mondal and Ghosh (2018), a bacteria concentration of 107 cells/mL of B. subtilis was found to be the ideal concentration for healing concrete cracks. After 3 days of incubation, this concentration almost completely repaired the fracture breadth, while at 105 cells/mL and 103 cells/mL, it was only 70 % and 30 % repaired, respectively. After 7 days, the cracks were repaired by 85 % and 50 % at 105 cells/mL and 103 cells/mL, and by 90 % and 60 %, respectively, after 28 days. Furthermore, Ansari and Joshi (2019) reported that as the concentration of E. coli increased, the concrete strength improved by 2 % to 5 %. This indicates that a higher bacterial concentration leads to increased CaCO3 precipitation, enhancing the efficiency of concrete healing. Regarding fungi, the optimal cell concentration is about 5 × 106 cells/mm3 to improve mortar compressive strength (Seifan et al., 2016a, Seifan et al., 2016b). Additionally, the amount, size, shape, and distribution of healing agent-containing capsules or porous carriers should be optimized to achieve effective self-healing without compromising compressive strength (Jin et al., 2018). Potentially, the numerical simulation might be implemented to model the optimal ratio, reduce the number of laboratory trials, decrease material use, and reduce time.

4.4. Calcium carbonate precipitation rate and crack width

Use of bacterial cells as a healing agent encounter challenges in maintaining a continuous and constant rate of CaCO3 precipitation due to rapid precipitation rates near the cellular membrane, as described by Wang et al. (2014b). This swift precipitation at the initial stages can limit space within concrete cracks, thereby delaying the formation of CaCO3 crystals, a phenomenon also noted by Mondal and Ghosh (2018). Further, a high rate of CaCO3 precipitation within the crack can inhibit bacterial activity by restricting their growth and survival space. This accumulation may also create a diffusion barrier around the bacteria, hindering their access to substrates necessary for CaCO3 precipitation and impeding the removal of by-products. A study by Whiffin et al. (2007) observed that the ureolytic bacteria's ability to decompose urea was gradually reduced due to the rapid formation of a CaCO3 barrier. Thus, continuous CaCO3 precipitation along with ongoing cement hydration can also restrict water flow and oxygen availability, which are essential for ureolytic activity. Additionally, the source and initial concentration of Ca2+ ions are critical in the precipitation of CaCO3, with most ureolytic bacteria utilizing Ca2+ ions from their environment to form CaCO3 in the self-healing of cracks, as indicated by Javeed et al. (2024).

Additionally, the presence of chloride ions in the medium can impact the durability of structures negatively (De Muynck et al., 2010). Therefore, various calcium salts such as calcium acetate, calcium nitrate, and calcium lactate are commonly used as calcium sources (Javeed et al., 2024). For instance, Zheng et al. (2021) reported that concrete's compressive strength during early curing stages was higher with calcium nitrate than with calcium lactate. Conversely, bacterial spores were found to produce more white precipitation at the crack mouth with calcium lactate than with nitrate, which is supported by findings of increased calcite precipitation or enhanced flexural or compressive strength with calcium lactate (Chaerun et al., 2020; Vijay and Murmu, 2019). Furthermore, the width and age of cracks in concrete significantly influence the efficacy of microorganisms in the self-healing process (Javeed et al., 2024). Larger crack widths can diminish healing performance due to the inadequate filling of the larger volume, and the risk of bacterial healing agents, nutrients, or CaCO3 deposits being washed out increases with the crack size. Wang et al. (2014b) observed that cracks wider than 0.5 mm exhibited significant CaCO3 precipitation and deposition outside the crack, which could lead to reduced sealing efficiency or extended restoration time. Thus, larger cracks present greater challenges for concrete restoration through bioconcrete self-healing technologies.

Although bacteria have been reported to heal cracks up to 0.97 mm (Muhammad et al., 2016), fungi such as Trichothecium sp. and Fusarium oxysporum can produce a substantial amount of CaCO3 precipitates within short periods, with immature calcite crystals observed after just 12 h at 27 °C and smooth surfaces after three days (Ahmad et al., 2004). Jin et al. (2018) highlighted that fungal-mediated self-healing properties can sustain long-term self-healing capabilities, potentially healing wider cracks more rapidly than bacterial agents, which are generally limited to healing cracks <1 mm in width. Filamentous fungi, with their ability to form a three-dimensional mycelium network and their exceptional cell wall-binding and metal-uptake capabilities, offer distinct advantages for various applications in biomineralization-based technologies (Jin et al., 2018).

5. Opportunities and challenges of self-healing bioconcrete technology

5.1. Opportunities for self-healing bioconcrete technologies

Compared to traditional concrete, self-healing bioconcrete utilizing microorganisms offers several potential benefits. One significant advantage is the in-situ formation of CaCO3 by the bacteria and fungi, leading to increased durability and structural strength. The MICCP process stabilizes the CaCO3 formation rapidly using solubilized substrates like urea and CaCl2, effectively repairing the concrete (Algaifi et al., 2021; Naveed et al., 2020). Bioconcrete demonstrates enhanced resistance to corrosion and environmental changes by sealing concrete pores and cracks with CaCO3 crystals, reducing permeability and chemically-induced degradation (Farmani et al., 2022). For example, the presence of bacteria in bioconcrete can also prevent structure deterioration by removing oxygen from the concrete mixture, acting as an oxygen diffusion barrier (Wiktor and Jonkers, 2011). Moreover, bioconcrete with bacteria in a moist environment increases resistance to chloride ion intrusion, thanks to the enhanced electric resistivity provided by the MICCP process (Kawaai et al., 2022).

Experimental results indicate the superior strength of bioconcrete compared to traditional concrete, with bacterial concrete samples exhibiting slightly higher strength (Wiktor and Jonkers, 2011). Studies have shown that the addition of biological healing agents increases the flexural and compressive strengths of mortar samples, with improvements ranging from 10 % to 13 % (Joshi et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2018a). Furthermore, Zhao et al., 2022a, Zhao et al., 2022b proposed biomineralization-based fungal coating for porous mineral-based building materials, which enhances water resistance by 17 % and blocks water infiltration. MICCP technology is not only more durable but also more sustainable than traditional concrete repairs. For instance, employing cyanobacteria as a self-healing agent enables the capture of atmospheric CO2 to form CaCO3 (Ansari and Joshi, 2019), while incorporating biochar derived from organic waste into cementitious materials enhances sustainability and promotes carbon sequestration (Gupta et al., 2018). Moreover, MICCP methods and bioencapsulation yield environmentally friendly by-products such as water, and microbe-assisted concrete restoration is less energy and material-intensive than producing new concrete, thereby cutting carbon emissions and resource use.

In the last decade, bioconcrete technologies have been explored successfully in various structure including water channels, foundations, tunnels etc. in different countries, such as Belgium, China, Ecuador, Netherlands, and the United Kingdom (Davies et al., 2018; Qian et al., 2021; Van Mullem et al., 2020). Qian et al. (2021) demonstrated large scale production and utilization of spore powder in engineering buildings by novel spray drying technology which reduces the construction time significantly. Similarly, Sierra-Beltran et al. (2015) employed Bacillus spores and natural fibers successfully in an irrigation canal at Andean highlands in Ecuador and observed no visible surface crack even after 1 year of implication. In another study, bacterial spore was used in powder form for its application in ship lock engineering and Zhang and Qian (2022) reported a complete self-healing of the crack without any leakage after 60 days in the ship lock further suggesting that microbial self-healing bioconcrete technology has the potential for wider used in self-healing of concrete crack even in the hydraulic environment. All the current trends advocate for the industrialization of self-healing bioconcrete technology but require further advanced research and widespread adoption of bioconcrete for its future large-scale implication. Overall, self-healing bioconcrete offers a viable solution for sustainable concrete development, minimizing environmental burdens and promoting carbon emission reduction, energy efficiency, and resource conservation.

5.2. Challenges faced by self-healing bioconcrete technologies

5.2.1. Low microbial viability and space limitations

The effectiveness of microbial healing of fractured bioconcrete diminishes over time depending on the kinetics of CaCO3 deposition (Algaifi et al., 2021; Mondal and Ghosh, 2018). A study by Ansari and Joshi (2019) using E. coli as the healing agent revealed that bioconcrete's compressive strength decreased by up to 11.5 % after 90 days, suggesting a time-related decline in the material's integrity. Another study by Jonkers et al. (2010) showed that the viability of spore forming bacteria like B. cohnii decrease as concrete ages, impacting the self-healing process. This decline may be due to the harsh conditions within the concrete and limited access to essential nutrients required by the microorganisms (Fig. 4). Most bacteria directly mixed with concrete do not survive beyond 4 months, indicating the need for periodic replenishment of the bacterial population (Chen et al., 2019; Jonkers et al., 2010).

Fig. 4.

Challenges (Andrade et al., 2022; Chen et al., 2019; Erşan et al., 2016; Jin et al., 2018; Silva et al., 2015) and future prospects (Ansari and Joshi, 2019; Khushnood et al., 2022; Qian et al., 2022; Song et al., 2023) in the development of self-healing bioconcrete technologies.

The self-healing efficacy of bacteria is even more constrained in deeper concrete layers with only a 14 % repair rate reported for internal cracks compared to surface ones (Algaifi et al., 2021). Material transport challenges within the dense concrete matrix, reduced pore space, and limited oxygen and substrate availability impede bacterial healing actions and CaCO3 deposition in deep cracks (Erşan et al., 2016). Furthermore, bacteria are susceptible to the high pressures encountered during concrete production, which can compromise their survival and the healing process (Algaifi et al., 2021; Jonkers et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2016). In contrast, fungi show promise as an alternative healing agent due to their resilience under extreme conditions (e.g., low humidity, high alkalinity, varied temperatures, ultraviolet light exposure, and severe nutrient limitation) and their ability to produce durable spores (Jin et al., 2018; Menon et al., 2019). Encapsulation techniques, such as those using freeze-dried spores, could potentially enhance the longevity and effectiveness of both bacterial and fungal applications in concrete repair (Jin et al., 2018; Menon et al., 2019).

5.2.2. High alkalinity and vulnerability without protection

The release of ammonia in the urea-based MICCP process can pose environmental problems and impact concrete quality due to its status as an environmental contaminant (Erşan et al., 2016). Furthermore, the simultaneous production of two ammonium ions for every carbonate ion in urea-based MICCP can lead to excessive nitrogen burden and increased alkalinity within the concrete, affecting bacterial survivability and the potential for CaCO3 production in older concrete (Jonkers et al., 2010). The hydrolysis of urea generates NH4+ ions, which can convert to NH3 under alkaline conditions, posing a threat to the concrete structure and potentially causing deterioration (Fig. 4) (Erşan et al., 2016). Additionally, the high alkalinity environment can hinder bacterial growth and spore development, reducing the healing efficiency of the bacteria (Erşan et al., 2016).

Despite their enhanced tolerance, bacterial spores have limited survivability without protection (Farmani et al., 2022). Research has shown that bacteria survive better when protected by a coated expanded clay carrier compared to direct insertion into concrete fissures (Han et al., 2020). The protective shield, such as the carrier material, immobilizes bacteria and shields them from abiotic stress in the concrete environment. Without protection, bacteria are vulnerable to environmental changes, leading to reduced growth and survival rates. Destruction of the protective shield during concrete formation and restoration further compromises bacterial survival (Han et al., 2020). Therefore, the presence of a protective shield is crucial for the survival and effectiveness of bacteria in concrete restoration. On the other hand, fungi can grow and proliferate at a pH above 10. An example might be alkaliphilic fungi - Paecillomyces lilacimus and Chrysosporium spp. growing at pH values of 7.5–11.0. The ability to withstand extreme pH values lies in the possession of an osmotic barrier to the external environment helping to maintain their internal cellular pH at close to neutrality for efficient cellular functioning (Jin et al., 2018). Nevertheless, while some species may exhibit potential for reproduction in harsh conditions, it is imperative to prioritize the evaluation of human health safety concerns associated with their use in the development of self-healing bioconcrete. For example, the use of high concentrations of Purpureocillium lilacinum spores for biocontrol might pose a health risk in immunocompromised humans (Luangsa-ard et al., 2011). Therefore, more research is needed to determine the pathogenicity factors of fungi before their application as a self-healing agent.

5.2.3. Cost effectiveness

Self-healing bioconcrete shows promising results in terms of healing performance, durability, and eco-friendliness compared to traditional concrete. However, this technology comes with high operation and research expenses. The MICCP mechanism used in bioconcrete is costly due to the production expenses involved in culturing the microbes responsible for self-healing. The cost of microencapsulated bacteria and nutrients can be significant, with estimates of US$ 1500/kg for bacteria and US$ 250/kg for nutrients (De Muynck et al., 2008). Silva et al. (2015) reported the bacteria-based self-healing bioconcrete with encapsulated or immobilized spores currently results in prices of about US$ 6876/m3, making this self-healing technique unlikely to be used in practical applications.

More recent estimations of the cost design of bacteria-based self-healing bioconcrete were provided by Andrade et al. (2022). The calculation considered bacteria Sporosarcina pasteurii and concluded that the cost of production of 1 kg of concrete with bacteria is estimated at US$ 0.29, while without at US$ 0.16/kg of concrete produced. The estimation of concrete with fungi is even more challenging, as the technology is less mature compared to bacteria. However, fungi are easier to obtain, handle, and culture in large quantities, which potentially may reduce the costs of self-healing bioconcrete (Buckley, 2008; Soccol et al., 2017). Additionally, fungi have simpler nutritional requirements. Many fungal species are oligotrophic, meaning they can survive by scavenging small amounts of volatile organic compounds from the atmosphere, which reduces the burden on nutrient supply and potentially extends the operational service life of structures with self-healing concrete containing fungi.

The MICCP process on concrete surfaces typically ranges from US$ 7 to 15/m2. Additionally, the use of bacteria carrier encapsulation, although offering better healing performance, significantly increases the overall treatment cost due to the expenses associated with acquiring bacteria, nutrients, and carrier materials. The utilization of microcapsule technology is both costly and time-consuming (Wang et al., 2014b). Consequently, the development and commercialization of self-healing bioconcrete technology face challenges due to the high production and research costs, unless cost-effective alternatives for bacteria and nutrients are discovered. Nevertheless, considering the current self-healing bioconcrete market valued at around US$ 56 billion dollars and anticipated growth at 31.5 % compound annual growth rate (CAGR) from 2023 to 2032 the technology has the potential to expand in the near future (Report-GMI7497, 2023).

5.2.4. Potential health impact of microbial self-healing

Microbial self-healing in concrete involves the use of microorganisms, such as bacteria or fungi, to repair cracks and improve the durability of the material. While this technology holds promise for extending the lifespan of concrete structures and reducing maintenance costs, there are potential health impacts and uncertainties associated with using fungi in this application. Some fungi can produce allergens that may cause allergic reactions in sensitive individuals. Exposure to fungal spores, even in small amounts, can trigger symptoms such as asthma, rhinitis, and skin irritation (Fig. 4). Certain fungi can produce mycotoxins, which are toxic compounds that can pose serious health risks if inhaled or ingested (Zukiewicz-Sobczak, 2013). The presence of mycotoxins in the environment can lead to respiratory issues, immune suppression, and other health problems. Opportunistic pathogenic fungi, although rare in self-healing bioconcrete applications, could potentially cause infections, especially in immunocompromised individuals.

For example, species like Aspergillus can cause aspergillosis, a serious lung infection (Zukiewicz-Sobczak, 2013). If the fungi used in concrete were to be released into the environment, there could be unintended ecological impacts. This includes the potential for the fungi to colonize other substrates and impact local ecosystems. The use of fungi in construction materials is relatively new, and regulatory frameworks may not be fully developed yet (Onyelowe et al., 2024). Therefore, ensuring that the fungi used are safe and that there are standards for monitoring and managing any health risks is essential. Only non-pathogenic and well-characterized fungal strains that do not produce harmful mycotoxins or allergens should be used (Van Wylick et al., 2021), For example, T. reesei, A. nidulans, and F. oxysporum are Biosafety Level 1 (BSL 1) fungi, which means they are well-characterized, not known to cause disease in healthy humans and are of minimal potential hazard to laboratory personnel and the environment (ATCC: The Global Bioresource Center). Monitoring systems to detect any potential health risks or environmental impacts associated with the use of fungi in concrete should be implemented. Moreover, research should focus on adhering to existing safety and regulatory guidelines and work towards developing new standards specifically for microbial self-healing applications. Thus, while microbial self-healing using fungi in concrete has the potential to offer significant benefits, it is essential to carefully consider and address potential health impacts and uncertainties. This involves rigorous scientific research, adherence to safety standards, and the development of effective containment and monitoring strategies.

6. Future prospects of self-healing bioconcrete technologies

6.1. Self-healing of concrete through diverse microorganisms

Bacteria are commonly used in self-healing bioconcrete, but other microorganisms like fungi and algae show promise as well (Gadd, 2021; Jin et al., 2018). Recent studies have highlighted the healing performance of fungi, with species like Rhizopus oryzae and Trichoderma longibrachiatum showing efficiency in healing concrete fractures when enclosed in calcium alginate beads (Khushnood et al., 2022). Further research on fungi for self-healing bioconcrete is recommended. Additionally, exploring the use of algae, such as diatoms, in concrete crack healing is a feasible and promising direction. Algae, with their carbon absorption capabilities, offer a more environmentally responsible choice for biologically healing concrete. Introducing algae species into concrete fractures could be a future study to assess their feasibility in crack healing and contribute to more sustainable concrete solutions.

Apart from exploring novel microorganisms for bioconcrete application, it is also important to have in-depth knowledge of the viability and metabolisms of microorganisms under various environmental conditions for enhanced self-healing performance of the microorganisms as extreme environmental factors can have a serious detrimental impact on the long-term self-healing efficiency (Kim et al., 2021). Future research is required to identify the best possible carriers which can help in increasing the life span and the metabolic activity of the microorganism inside the extreme environment of the concrete structure. Similarly, exploring better implementation methods like the spray method instead of direct or encapsulation method is necessary to protect the microorganisms from the extreme condition and enhancing the efficiency and effectiveness of the self-healing technologies.

6.2. Nutrient availability and mixed microbial cultures

New strategies can be developed to address nutrient limitations in concrete environments to create a diverse microbiological ecosystem. Thus, introducing different types of microorganisms into concrete cracks and establishing mutualistic and syntrophic relationships to mimic natural ecosystems, promoting the growth of self-healing microbes without long-term environmental impacts. Combining multiple types of bacteria in biofilm structures has shown cost-saving benefits and enhanced healing performance. For example, combining ureolytic and non-ureolytic bacteria in mixed cultures has proven effective (Doctolero et al., 2020; Son et al., 2018). Further research can explore the impact of combined calcium sources on mixed bacterial or microbial species, investigating the utility and outcomes of the MICCP mechanism (Zhang et al., 2017b).

Further, studying the ecological relationships between different microorganisms in mixed microbial cultures is a potential area of research in the concrete environment. Evaluating symbiotic or competitive behaviors among bacteria, fungi, and algae under various conditions is crucial for assessing the potential of biological self-healing mechanisms in concrete. Future studies can focus on the effects of different environments, optimal microbial populations, interaction degrees between species, and bioencapsulation technologies suitable for mixed-culture applications in self-healing bioconcrete. Quality control techniques for mixed cultures and factors influencing their healing capabilities, such as oxygen availability and temperature, can also be explored. Investigating these aspects will contribute to a better understanding of the efficacy and limitations of diverse self-healing processes when microbial species co-exist in mixed-culture environments.

6.3. Long-term effect of the self-healing bioconcrete

Although numerous studies have measured the increased self-healing potential of bacteria-based concrete, there are two important aspects that need to be addressed before practical use can be considered: long-term endurance and cost-effectiveness (Wiktor and Jonkers, 2011). Since the long-term efficacy of concrete self-healing biotechnology remains unknown, it could be a potential future direction for scientists and researchers to continuously explore and improve the optimal self-healing bioconcrete technology (Meraz et al., 2023). For example, in the future, there could be large-scale and ongoing monitoring and research into the self-healing bioconcrete technology, examining its performance after years of exposure to the environment. Additionally, because current experiments may not focus on or cover this area, researchers can develop non-destructive evaluations and assessments to monitor and evaluate the long-term effects of self-healing bioconcrete in real-world applications. Investigating and discovering the long-term effects can help resolve unresolved issues regarding the long-term impact of microbes on concrete structures and the performance of biological self-healing mechanisms. However, recent successful application of microbial self-healing bioconcrete in large-scale projects like irrigation channels, tunnels, ship lock, etc., could definitely promote the widespread acceptance and reliability for increased commercialization.

6.4. Advancing self-healing bioconcrete with computational integration