Abstract

Porcine enteric calicivirus (PEC) is associated with diarrhea in pigs, and to date it is the only cultivable enteric calicivirus (tissue culture-adapted [TC] PEC/Cowden). Based on sequence analysis of cDNA clones and reverse transcription-PCR products, TC PEC/Cowden has an RNA genome of 7,320 bp, excluding its 3′ poly(A)+ tail. The genome is organized in two open reading frames (ORFs), similar to the organizations of the human Sapporo-like viruses (SLVs) and the lagoviruses. ORF1 encodes the polyprotein that is fused to and contiguous with the capsid protein. ORF2 at the 3′ end encodes a small basic protein of 164 amino acids. Among caliciviruses, PEC has the highest amino acid sequence identities in the putative RNA polymerase (66%), 2C helicase (49.6%), 3C-like protease (43.7%), and capsid (39%) regions with the SLVs, indicating that PEC is genetically most closely related to the SLVs. The complete RNA genome of wild-type (WT) PEC/Cowden was also sequenced. Sequence comparisons revealed that the WT and TC PEC/Cowden have 100% nucleotide sequence identities in the 5′ terminus, 2C helicase, ORF2, and the 3′ nontranslated region. TC PEC/Cowden has one silent mutation in its protease, two amino acid changes and a silent mutation in its RNA polymerase, and five nucleotide substitutions in its capsid that result in one distant and three clustered amino acid changes and a silent mutation. These substitutions may be associated with adaptation of TC PEC/Cowden to cell culture. The cultivable PEC should be a useful model for studies of the pathogenesis, replication, and possible rescue of uncultivable human enteric caliciviruses.

Caliciviruses (family Caliciviridae) are small, nonenveloped viruses that are 27 to 35 nm in diameter (6, 12, 18). They possess a single-stranded, plus-sense genomic RNA that is 7 to 8 kb in length and that encodes a single structural protein of 58 to 80 kDa and a polyprotein that contains motifs indicative of a putative 2C helicase, 3C-like protease, and RNA-dependent RNA polymerase 3D (4, 6, 18). Animal caliciviruses are suspected or confirmed causes of a wide spectrum of diseases, including gastroenteritis (pigs, calves, cats, dogs, and chickens), vesicular lesions and reproductive failure (pigs and sea lions), respiratory infections (cats and cattle), a fatal hemorrhagic disease (rabbits), and infectious stunting syndrome (chickens) (2, 3, 26, 35, 37). Human caliciviruses (HuCV) are the leading cause of epidemic, nonbacterial gastroenteritis in humans of all ages (6, 7, 11, 18).

Caliciviruses are divided into four groups in the family Caliciviridae: (i) the genus Vesivirus, (ii) the genus Lagovirus, (iii) Norwalk-like viruses (NLVs), and (iv) Sapporo-like viruses (SLVs) (12). The vesiviruses and NLVs have three separate open reading frames (ORFs) in their genomes, whereas the lagoviruses and SLVs have similar genomic organizations composed of two ORFs. Viruses within a genus are phylogenetically related and have common features in genomic organization and high degrees of sequence similarities in the RNA polymerase and capsid regions. The NLVs are further subdivided into two genogroups represented by the prototype Norwalk virus (NV; genogroup I) and the Snow Mountain agent (SMA; genogroup II) (6, 12, 18). The SLVs include the HuCV with classical calicivirus morphology such as the Sapporo virus (SV), Manchester virus (MV), and Parkville virus, which are associated mainly with acute gastroenteritis in infants and young children (6, 12, 18, 28). To date, the complete genomes of several caliciviruses, including members from all genera, have been sequenced. These include the NLVs NV (17), Southampton virus (SHV) (20), Lordsdale virus (LV) (5), and most recently the bovine enteric calicivirus (BEC), Jena strain (24), the SLV MV (22, 23); the lagovirus rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus (RHDV) (26); and the vesiviruses feline calicivirus (FCV) (3) and primate calicivirus (PCV) (32). However, the genetic relationships of most animal enteric caliciviruses to HuCV remain undefined.

A porcine enteric calicivirus (PEC) was first reported in the United States (33) and in the United Kingdom (2). The PEC Cowden strain resembles classical caliciviruses in morphology, virion size, RNA genome, and possession of a single capsid protein of 58 kDa (31) but is not antigenically related to vesiviruses, including vesicular exanthema of swine virus (VESV), San Miguel sea lion virus (SMSV), and FCV (33). Experimental infection of pigs with wild-type (WT) PEC/Cowden results in profuse diarrhea, anorexia, and intestinal lesions (10). The tissue culture-adapted (TC) PEC/Cowden strain is the only enteric calicivirus that has been successfully adapted to primary porcine kidney cells (9) and continuous pig kidney cell lines (30) by incorporating intestinal contents (IC) of uninfected gnotobiotic pigs into the cell culture medium. Recently PECs were detected by immune electron microscopy from 35% of weaned diarrheic pigs (37). To date, no PEC genome has been completely cloned or sequenced, so the genetic relationship of most PEC strains to HuCV and animal caliciviruses is undefined. However, NLV genes were recently detected in the cecal contents of normal slaughtered pigs (36), raising public health concerns about potential cross-species transmission and a possible swine reservoir for enteric caliciviruses related to HuCV (6, 11). In this report, we describe the cloning and sequencing of the complete RNA genome of the TC PEC/Cowden strain and its genetic relatedness to HuCV and animal caliciviruses. In addition, the complete genome of WT PEC/Cowden was sequenced and compared with the TC PEC/Cowden genome to reveal genetic differences potentially related to cell culture adaptation of TC PEC/Cowden.

Cloning and sequencing of the PEC RNA genome.

The Cowden strain of PEC was originally detected in feces of a 27-day-old diarrheic nursing pig (33). The virulence of this WT PEC was maintained by serial passage of intestinal contents containing PEC in orally inoculated gnotobiotic pigs (10). Infected intestinal contents were collected from the fifth passage of WT PEC/Cowden in gnotobiotic pigs and used for virus purification and RNA extraction as described below. The TC PEC/Cowden strain used in this study had been previously passaged 19 times in primary porcine kidney cells (9) prior to adaptation to a porcine kidney cell line (LLC-PK2) (30). TC PEC/Cowden was further propagated by 15 to 20 passages in the LLC-PK cells by inclusion of a 5.0% uninfected gnotobiotic pig intestinal content filtrate (0.45-μm-pore-size filter) in the culture medium as described previously (30). The virus particles were purified from PEC-infected cell lysates and from intestinal contents of PEC-infected gnotobiotic pigs by differential centrifugation and centrifugation through a 40% sucrose cushion, respectively (31). The PEC genomic RNA was purified by guanidinium thiocyanate denaturation, phenol-chloroform extraction, and isopropanol precipitation (1). The viral RNA was further purified through an oligo(dT)-cellulose column (mRNA Separator Kit; Clontech, Palo Alto, Calif.), and the eluate was stored at −70°C. First-strand cDNA was synthesized from purified viral RNA with RNase H− Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (SuperScript II; Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.) with a 3′-terminally degenerate oligo(dT) primer, primer VN (Table 1) (1). The RNA-DNA hybrids were treated with Escherichia coli RNase H for 20 min at 37°C. This cDNA was used as a template for amplification of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase region by PCR with a random primer (N9) and a degenerate primer (PEC-10) (Table 1) based on the conserved sequences of the GLPSG motif in the RNA polymerase regions of all caliciviruses. Amplification was performed by using the Expand Long Template PCR System, which includes Taq and Pwo DNA polymerases (Boehringer Mannheim Corp., Indianapolis, Ind.) with a Perkin-Elmer Cetus model 4800 thermal cycler for 35 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, annealing at 45°C for 1 min, and extension at 72°C for 1 min, followed by a final extension at 72°C for 10 min (1). The initial 660-bp cDNA product was cloned into the TA cloning vector pCR2.1 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.), and the nucleotide sequence was determined with a model ABI 377 automated DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems). New specific primers based on the known sequences and degenerate primers based on sequences of the 3C protease and 2C helicase motifs of the MV were used to target the corresponding regions of PEC genomic RNA in a reverse transcription (RT)-PCR (Table 1). The products were either sequenced directly or cloned into the vector pCR2.1 and sequenced. Primers based on sequences of cDNA clones were used to amplify and sequence the corresponding cDNA products. Both strands of cDNA amplicons were sequenced to ensure the accuracy of the sequence data. Primers PEC7 and VN (Table 1) were used in RT-PCR to amplify a 2.2-kb amplicon covering the region from the 3′ terminus of the RNA polymerase to the 3′ terminus of the RNA genome. Sequences of the regions upstream of the RNA polymerase were determined by sequencing the RT-PCR products, which had been amplified with downstream specific primers (PEC8 and PEC28) (Table 1) and upstream degenerate primers (PEC22 and PEC23) (Table 1) based on the sequences of the highly conserved 3C protease motif (GDCG) and 2C helicase motif (GXXGIGKT) of the MV, respectively.

TABLE 1.

Sequences of primers used for RT-PCR

| Primer name | 5′ position or sequence | Polarity | Primer sequence, 5′ to 3′ |

|---|---|---|---|

| VN | − | GCT GGA GTC TAG A(T)25 (A/G/C) (A/T/G/C) | |

| PEC7 | 5112 | + | TGA AGA TGA AGA GCC AGA |

| PEC8 | 4643 | − | TCC CCG TAG GTG TAA ATA GTC |

| PEC10 | GLPSG | + | GGT GGY CTV CCW TCT GG |

| PEC22 | GXPGIGKT | + | GCA CCT GGC ATH GGN AAR AC |

| PEC23 | GDCG | + | AAG AAA GGK GAY TGY GG |

| PEC28 | 3611 | − | GCT TTT GCG GTC TTC TTG GTT |

| GSP1 | 1531 | − | ACT CGT CCC AAA TTG CTA CTG TGT |

| GSP2 | 1507 | − | TGC CTG TGT ACG TGT CAT AGT |

| GSP4 | 624 | − | AGT GGT GTC AAT GTG TGG CA |

| GSP5 | 606 | − | CAT TTT GCG CTT CAC GTC CT |

To determine the genomic 5′-terminal sequence, the specific primer GSP1 (Table 1) was used to prime first-strand cDNA synthesis. The homopolymeric dC tail was added to the 3′ end of the first-strand cDNA with the 5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends system (Gibco BRL). By using the primers GSP1 and GSP2 (Table 1) in combination with the 5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends abridged anchor primer and abridged universal primer, a 1.5-kb amplicon was amplified by RT-PCR with Taq and Pwo DNA polymerases. The product was cloned into the vector pCR2.1 and sequenced. The genomic 5′-terminal sequence was further confirmed by using homopolymeric (dA or dC) tailing and PCR with the primers GSP4 and GSP5 (Table 1) in combination with the abridged anchor primer, the abridged universal primer, or VN. The products were sequenced directly to determine the 5′-terminal sequence.

Sequence analyses were performed by using Lasergene software (DNASTAR Inc., Madison, Wis.). Multiple alignments of nucleotide and predicted amino acid sequences were performed by using the University of Wisconsin Genetics Computer Group software package. The PEC genomic sequence was compared with those of the SLVs, NLVs (genogroups 1 and 2), vesivirus (FCV and SMSV), and lagovirus (RHDV). To further define the genetic relationship between PEC and caliciviruses representative of different genera, phylogenetic trees were generated for sequences in the RNA polymerase region and the capsid region. Sequences in either region were aligned with CLUSTAL W (38), and trees were generated with the PHYLIP package (8).

Sequence analyses of the PEC genome.

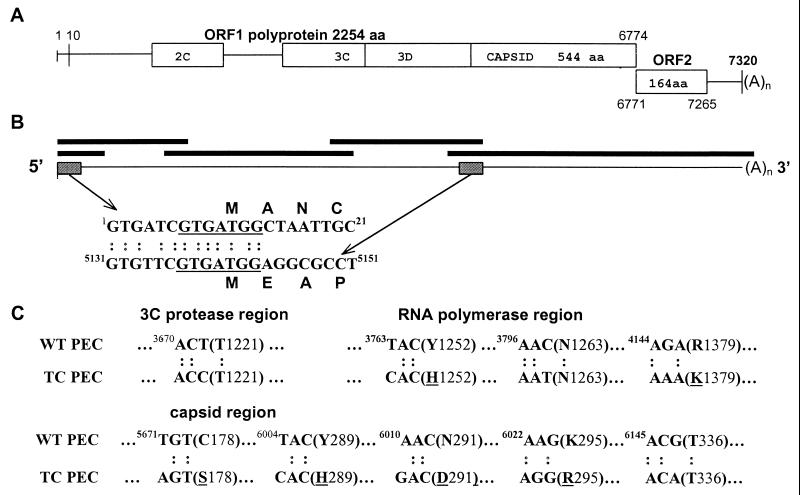

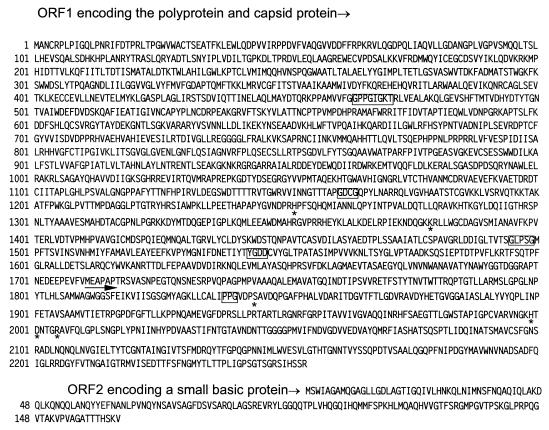

The PEC/Cowden RNA genome consists of 7,320 nucleotides, excluding the 3′ polyadenylated tail, and has a nucleotide composition of 24.89% A, 26.22% G, 21.79% T, and 27.10% C and an overall G+C content of 53.32%. Sequence analysis revealed that PEC has a genomic organization composed of two predicted ORFs (Fig. 1A), similar to those of lagoviruses (RHDV and European brown hare syndrome virus [EBHSV]) and the SLVs (12, 22, 26). ORF1 encodes the polyprotein that is fused to and contiguous with the capsid protein in the same reading frame. The large ORF1 polyprotein of 2,254 amino acids (aa) is predicted to be co- or posttranslationally cleaved into the 2C helicase, 3C-like protease, 3D RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, and a structural protein of 544 aa (Fig. 1 and 2). The predicted polyprotein contains the characteristic 2C helicase (GPPGIGKT), 3C protease (GDCG), and RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (GLPSG and YGDD) motifs that are highly conserved in all caliciviruses (Fig. 2). (4, 6, 18). The N-terminal region of the ORF1 polyprotein is highly divergent among caliciviruses. The N terminus of 200 aa of the PEC polyprotein has only 15% amino acid sequence identity with that of the SLV MV. There are, however, higher amino acid sequence identities between PEC and MV in the putative 2C helicase region (aa 366 to 615 for PEC; 49.6%) and the 3C-like protease region (aa 1063 to 1181 for PEC; 43.7%) (data not shown). PEC has low amino acid sequence identities in the 2C helicase and 3C-like protease regions with vesiviruses (PCV, 38.3 and 20.5%; FCV, 37.5 and 17.9% for the 2C helicase and 3C-like protease, respectively), lagoviruses (RHDV, 30.8 and 18.9%; EBHSV, 33.3 and 20.7%), and NLVs (NV, 25.8 and 16.0%; the Jena strain of BEC, 25.8 and 16.8%; SHV, 25.8 and 15.1%; LV, 15.1 and 23.3%). In the RNA polymerase region, PEC has the highest amino acid sequence identity (62.1 to 66%) with SLVs, including MV, SV, Parkville virus, and other SLVs (partial data shown in Table 2). PEC has higher amino acid sequence identity in this region with the cultivable vesiviruses (FCV and SMSV, 45.1 to 46%) and noncultivable lagoviruses (RHDV, 37.3%) than with the NLVs (23.4 to 30.5%), including members of genogroups 1 and 2, the Jena strain of BEC, and the swine caliciviruses detected in Japan (Sw43-97-J, Sw48-97-J, Sw584-97-J, and Sw918-97-J [36]) (partial data shown in Table 2).

FIG. 1.

Genomic organization of the PEC. (A) Schematic of the genomic organization of PEC/Cowden. Two predicted ORFs include ORF1, a polyprotein fused to and contiguous with the capsid protein, forming a large polyprotein, and ORF2, a small basic protein of unknown function. The nucleotide coordinates of the predicted proteins are numbered above or below the open boxes. (B) Schematic of the conserved nucleotide sequence motifs at the 5′ termini of the genomic and predicted subgenomic RNAs. Their nucleotide sequences are aligned beneath the genomic map. Shaded boxes indicate the genomic locations of the conserved motifs in the polyprotein. The Kozak context favorable for translation initiation is underlined. The thick lines represent those overlapping clones used for assembling a full-length genome. (C) Schematic of the nucleotide and amino acid sequence differences in the predicted 3C-like proteases, RNA polymerases, and capsid proteins between TC PEC/Cowden and WT PEC/Cowden. The partial sequences are aligned, the nucleotide coordinates are indicated for each codon, and the amino acid coordinates are indicated after each amino acid.

FIG. 2.

The predicted amino acid sequences of proteins encoded by the two ORFs of the PEC RNA genome. The conserved motifs including the putative 2C helicase (GPPGIGKT), 3C-like protease (GDCG), and 3D RNA polymerase (GLPSG and YGDD) in the polyprotein, as well as the first PPG motif in the predicted capsid protein, are boxed. The amino acid sequence coordinates for each of the two ORFs are on the left. The amino acids with substitutions in the RNA polymerase and capsid regions of TC PEC/Cowden are indicated by asterisks below each residue. The predicted start site (aa 1711; MEAPAP) of the capsid protein is underlined with an arrow. The three discrete regions in the predicted capsid protein are as follows: conserved region 1, aa 1711 to 1984; hypervariable region 2, aa 1985 to 2132; and region 3, aa 2133 to 2254.

TABLE 2.

Percentages of amino acid sequence identity in the RNA polymerase region and N-terminal conserved region 1 of the capsid proteins of PEC, SLVs, NLVs, and animal calicivirusesa

| Virus | % Amino acid identity with:

|

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MV | SV | Hu90 | Ln92 | PEC | FCV | SMSV | RHDV | NV | DSV | SHV | JV | SMA | HV | TV | BV | |

| SLVs | ||||||||||||||||

| MV | 99.3 | 81.7 | 75.8 | 66.0 | 45.8 | 45.8 | 32.0 | 29.1 | 29.1 | 28.5 | 29.1 | 27.4 | 27.5 | 30.5 | 30.5 | |

| SV | 100 | 82.4 | 75.8 | 65.4 | 49.0 | 45.8 | 32.0 | 29.1 | 29.1 | 28.5 | 29.1 | 27.4 | 57.7 | 30.5 | 30.5 | |

| Hu90 | 87.0 | 87.0 | 75.8 | 66.0 | 45.8 | 46.4 | 32.7 | 27.8 | 25.8 | 27.2 | 27.2 | 25.8 | 26.1 | 30.5 | 30.5 | |

| Ln92 | 54.4 | 54.4 | 51.0 | 62.1 | 47.1 | 43.8 | 34.6 | 26.5 | 27.2 | 25.0 | 27.2 | 25.0 | 25.5 | 27.2 | 27.2 | |

| PEC | 50.0 | 50.0 | 49.2 | 43.7 | 46.4 | 45.1 | 37.3 | 27.8 | 27.2 | 26.5 | 28.5 | 23.4 | 29.7 | 29.1 | 30.5 | |

| Vesiviruses | ||||||||||||||||

| FCV | 28.8 | 29.8 | 27.9 | 22.8 | 30.7 | 60.3 | 37.2 | 25.8 | 27.2 | 26.5 | 28.5 | 23.4 | 29.7 | 29.1 | 30.5 | |

| SMSV | 27.3 | 27.3 | 26.9 | 24.7 | 24.4 | 47.3 | 35.0 | 28.5 | 27.8 | 21.0 | 28.5 | 27.2 | 27.1 | 27.2 | 28.5 | |

| Lagovirus RHDV | 26.3 | 26.3 | 24.0 | 24.7 | 26.0 | 24.6 | 23.1 | 23.2 | 23.5 | 24.5 | 25.8 | 25.0 | 27.1 | 25.8 | 26.5 | |

| NLVs | ||||||||||||||||

| NV | 24.0 | 24.0 | 23.3 | 23.2 | 24.0 | 22.0 | 20.4 | 19.9 | 83.4 | 91.4 | 76.8 | 55.6 | 60.3 | 64.1 | 62.9 | |

| DSV | 23.3 | 23.3 | 21.8 | 20.8 | 22.8 | 20.8 | 21.5 | 20.6 | 73.6 | 84.1 | 78.1 | 56.5 | 62.1 | 63.5 | 64.9 | |

| SHV | 24.0 | 24.0 | 22.5 | 20.5 | 22.8 | 22.7 | 21.9 | 21.0 | 78.6 | 76.9 | 74.8 | 58.1 | 61.6 | 64.9 | 64.2 | |

| JV | 20.6 | 20.6 | 17.9 | 20.5 | 24.4 | 19.7 | 18.8 | 19.5 | 57.1 | 57.9 | 55.4 | 64.5 | 64.9 | 68.2 | 68.9 | |

| SMA | 22.1 | 22.1 | 21.0 | 23.6 | 22.8 | 20.1 | 19.6 | 21.7 | 51.8 | 50.0 | 47.5 | 47.1 | 80.6 | 85.4 | 90.7 | |

| HV | 21.8 | 21.8 | 20.6 | 21.2 | 22.4 | 20.1 | 17.3 | 22.8 | 51.8 | 50.4 | 47.8 | 48.2 | 88.0 | 85.4 | 90.7 | |

| TV | 24.4 | 24.4 | 22.1 | 22.0 | 23.2 | 20.5 | 20.8 | 19.9 | 57.2 | 56.2 | 50.7 | 54.7 | 73.9 | 75.0 | 91.4 | |

| BV | 23.3 | 23.3 | 22.5 | 22.0 | 23.6 | 20.1 | 17.3 | 20.6 | 46.7 | 45.7 | 45.3 | 47.1 | 75.4 | 75.7 | 69.6 | |

Abbreviations for virus strains are as folows: Hu90, Houston/90/United States; Ln92, London/92/United Kingdom; JV, BEC Jena strain; and TV, Toronto virus. Sequences from an aa 1473 to 1572 of ORF1 (NV numbering) (RNA polymerase) were aligned with similar sequences of indicated caliciviruses. Sequences for alignment of capsid region 1 were from NV, aa 1 to 280; SHV and DSV, aa 1 to 281; JV, aa 1 to 279; TV, HV, and BV, aa 1 to 276; MV and SV, aa 21 to 282; Hu90, aa 21 to 279; Ln92, aa 23 to 284; PEC, aa 21 to 276; SMSV4, aa 149 to 415; FCV, aa 121 to 384; and RHDV, aa 22 to 288. Numbers in the upper right triangle are percentages of amino acid identity in the RNA polymerase regions, and numbers in the lower left triangle are percentages of amino acid identity in the conserved N termini of the capsid proteins.

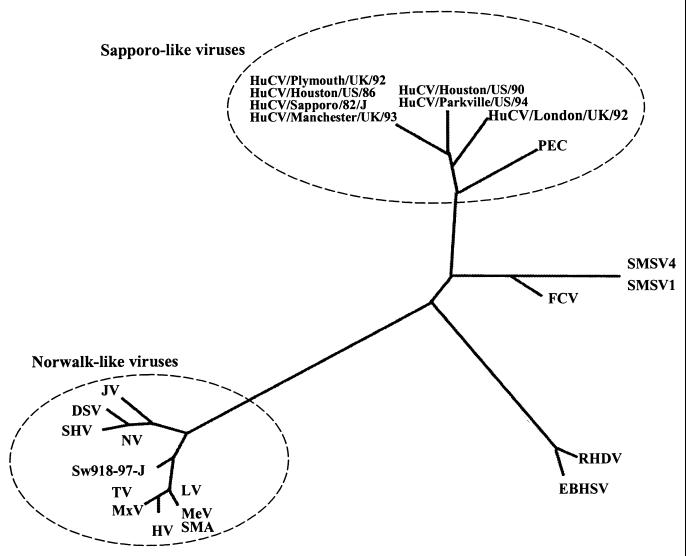

The SLVs possess typical calicivirus surface morphology distinct from that of NLVs (16, 22, 28, 29), and they are associated mainly with acute gastroenteritis in infants and young children or the elderly. SLVs were previously reported to be more closely related to the vesiviruses (FCV and VESV or SMSV) and lagoviruses (16, 22, 25, 29) than to NLVs. In our experiments, PEC/Cowden was more closely related genetically to SLVs than to vesiviruses, lagoviruses, or NLVs. Interestingly, PEC was genetically distant from both the caliciviruses described for pigs in Japan (36) and the Jena strain, a BEC (24).

The 5′ terminus of the genomic RNA begins with the characteristic trinucleotide GTG and has the same conserved nucleotide sequence motif in the 5′ terminus of the putative subgenomic RNA, which is characteristic of other human and animal caliciviruses (Fig. 1B). However, the lengths and sequences of the motifs vary for the different caliciviruses (3, 4, 13, 23, 24, 26). This 5′-terminal sequence motif of PEC has high nucleotide sequence identity with that of the SLV MV (80%) and the lagovirus RHDV (73%), both of which have genomic organizations similar to that of PEC. The sequence motifs of both the genomic and putative subgenomic RNAs of PEC have a Kozak structure (underlined) (GTG A/TTC GTGATGGC/AT/G) that is favorable for translation initiation of eukaryotic mRNA (19). In caliciviruses, the genomic 5′ nontranslated region (NTR) is usually the sequence motif itself and the capsid protein can be translated from both the genomic RNA and the subgenomic RNA in the lagovirus RHDV (26, 34). Thus, this leader sequence in the genomic and subgenomic RNAs may play an important role in the replication and the coupled transcription and translation of the genomic and subgenomic RNAs. Unlike picornaviruses, caliciviruses may not use an internal ribosomal entry site for translation of the polyprotein (6, 13).

The PEC capsid protein of 544 aa is slightly smaller than those of SLVs (557 to 571 aa). Sequence alignments indicate that there are two significant deletions in the N-terminal region and the hypervariable region of the TC PEC capsid (data not shown). PEC has higher overall amino acid sequence identity (39%) in the predicted capsid protein with SLVs than with vesiviruses (SMSV, FCV, and PCV) (17.1 to 21.7%), lagoviruses (RHDV; 18.9%), and NLVs (15 to 17.1%), including NV, SHV, SMA, LV, Hawaii virus (HV), and Bristol virus (BV) (data not shown). Like the SLVs, PEC capsid may be divided into three discrete regions. N-terminal region 1 (aa 1 to 280 for NV) is highly conserved and has higher amino acid sequence identity with those of SLVs (43.7 to 50%) than with those of vesiviruses (24.4 to 30.7%), lagovirus (26%), or NLVs (22.8 to 24.4%). Region 2 (aa 281 to 404 for NV) is hypervariable and corresponds to regions C to E in FCV and to SMSV1 and SMSV4 (22, 27). C-terminal region 3 is conserved but is less conserved than region 1. The capsid diversity among caliciviruses of the same genogroup or genus is determined mainly by the variability within region 2. This region contains multiple antigenic determinants recognized by monoclonal antibodies (14). Region 3 has conserved amino acid residues and a few antigenic epitopes but shows some variability, compared to region 1 (14).

The second ORF at the 3′ end of the genome consists of 495 nucleotides and codes for a small basic protein of 164 aa with a calculated isoelectric point of 10.3 (Fig. 2). ORF2 overlaps the 3′ end of ORF1 by four nucleotides (Fig. 1), which is common in SLVs, FCV, PCV, RHDV, and NLVs, and in this context, ATGA (the coexistence of the start codon [underlined] and the stop codon [italic]) may be a common feature for selective transcription and translation of the small basic protein in caliciviruses (3, 5, 16, 17, 20, 22, 24, 26, 28, 32). The putative basic protein of PEC is similar in size to those of SLVs (165 aa) and shows 33% amino acid identity with the SLVs MV and SV but only limited amino acid identity with vesiviruses, lagoviruses, and NLVs (11 to 20%). This small basic protein is highly divergent in sequence and differs in size in caliciviruses. However, this protein is rich in basic amino acids and extremely hydrophilic (6). It is likely functionally conserved and may be involved in protein-protein interactions or protein-nucleic acid interactions during viral replication based on its strong positive charge. Expression experiments with FCV-infected cells suggested that the ORF3 protein may function in viral growth (15). The 3′-terminal ORF protein of RHDV recently has been defined as a minor structural protein (40) and may ultimately be identified as such in other caliciviruses as well.

Phylogenetic relationship of PEC to human caliciviruses.

Phylogenetic trees generated for the RNA polymerase (Fig. 3) and the capsid protein (which is similar to RNA polymerase [data not shown]) show that PEC is more closely related genetically to the SLVs than to other human and animal caliciviruses. Also of interest is that PEC is clearly distinct from the swine caliciviruses recently detected in Japan (36). Like the SLVs London/92/United Kingdom Parkville virus, and Houston/90/United States, PEC falls out of the SV-MV group and forms a separate cluster in the group of SLVs. Thus, PEC may be placed in the SLV genus as an individual genogroup or clade different from those of the SV-MV, Parkville virus-Houston/90/United States, and London/92/United Kingdom groups.

FIG. 3.

Phylogenetic tree generated for the sequences in the RNA polymerase region. Alignments were generated from the conserved KDEL sequence to the end of the RNA polymerase or the start of the capsid protein. Calicivirus sequences used in the alignment were retrieved from GenBank. Strain names and abbreviations (GenBank accession numbers) are as follows: for SLVs, SV (S77903), MV (X86559), Parkville virus (U73124), HuCV Houston/86 (U95643), Houston/90 (U95644), London/92 (U67857), and PEC/Cowden (AF182760); for vesiviruses, FCV (M86379), SMSV1 (U15301), and SMSV4 (U15302); for lagoviruses, RHDV (M67473) and EBHSV (Z69620); for NLVs, NV (87661), Desert Shield virus (DSV) (U04469), SHV (L07418), BEC Jena strain (JV) (AJ011099), SMA (L23831), Melksham virus (MeV) (X81879), Toronto virus (TV) (U02030), Mexico virus (MxV) (U22498), HV (U07611), LV (86557), and the Sw918-97-J swine calicivirus (AB009415) detected in Japan.

Sequence comparisons between TC PEC/Cowden and WT PEC/Cowden.

Based on the known genomic sequence of TC PEC/Cowden, multiple specific primers were designed and used to amplify the corresponding regions of the WT PEC/Cowden RNA genome by RT-PCR. The PCR products were sequenced directly by using an automated DNA sequencer, and their sequences were aligned to generate the full-length RNA genome. Sequence alignments indicated that WT PEC/Cowden had 100% nucleotide sequence identity in the genomic 5′-terminal region, the 2C helicase, the entire ORF2, and the 3′ NTR with TC PEC/Cowden (data not shown). However, TC PEC/Cowden had one nucleotide substitution in the 3C-like protease region, resulting in a silent mutation (T1221) (Fig. 1C). TC PEC/Cowden also had three nucleotide substitutions in the RNA polymerase region, resulting in two amino acid changes (Y1252 to H and R1379 to K) and a silent mutation (N1263) (Fig. 1C). In the capsid, TC PEC/Cowden had five nucleotide substitutions that resulted in four amino acid changes (C178 to S, Y289 to H, N291 to D, and K295 to R and a silent mutation (T336) (Fig. 1C). These three amino acid substitutions occurred in a short region of 7 aa (aa 289 to 295 for PEC) in the hypervariable region and led to a localized higher hydrophilicity. Interestingly, this short region with amino acid changes corresponds to the region of the NV capsid responsible for the binding of viruslike particles to human and animal cells in vitro (39). For some viruses, a few amino acid changes at critical positions of the attachment protein(s) can dramatically alter viral tissue tropisms. With infectious bursal disease virus, a birnavirus, the uncultivable, highly virulent strains can be adapted to cell culture following two amino acid substitutions in the variable domain of a major structural protein, VP2 (21, 41). Thus, these substitutions in the TC PEC capsid may be associated with the adaptation of PEC to cell culture. The other two amino acid substitutions are located in the more variable N terminus of the RNA polymerase adjacent to the C-terminal 3C-like protease region. They may not be related to protease cleavage sites based on their positions in the sequence contest (Fig. 2). The significance of these two amino acid changes remains undefined. The highly divergent N terminus of the polyprotein and the divergent 3′ NTR may not be associated with the cell culture adaptation of PEC/Cowden. Future studies will be directed toward determining the significance of the above-described amino acid changes for cell culture adaptation of PEC/Cowden by reverse genetics. TC PEC/Cowden may also prove useful in attempts to rescue the uncultivable HuCV in cell culture.

The identification of two enteric caliciviruses in swine, the Cowden PEC most closely related to SLVs and the Japanese strains related to NLVs (36), raises public health concerns that swine may be reservoirs for enteric caliciviruses genetically related to HuCV. Whether such PEC are potentially transmissible to humans requires further analyses, including an assessment of the antigenic relationships between PEC and HuCV, and antibody prevalence studies to determine if humans have antibodies to PEC. Thus, it is important to develop serologic and genomic diagnostic assays to survey U.S. swine for the prevalence of PEC related to SLVs and NLVs. Furthermore, additional PEC isolates should be sequenced to determine their relationships to known HuCV. Because there is no animal model for HuCV infections, inoculation of swine with PEC strains related to HuCV such as WT PEC/Cowden may be a useful clinical model for studying the pathogenesis of enteric caliciviruses.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequence of the TC PEC/Cowden genome has been deposited in the GenBank database as accession no. AF182760.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kathy Gadfield, Peggy Lewis, and Paul Nielsen for technical assistance. We are grateful to Tamie Ando and Baoming Jiang (CDC, Atlanta, Ga.) and to David Matson and Xi Jiang (Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, Va.) for advice on protocols and primer sequences. We are grateful to Mary Estes (Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Tex.) for providing NV RNA as a PCR-positive control for the NV primers.

Salaries and partial research support were provided by state and federal funds appropriated to the Ohio Agricultural Research and Development Center, The Ohio State University. This work was supported in part by USDA NRICGP competitive grant 99-35204-7900.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ando T, Monroe S S, Noel J S, Glass R I. A one-tube method of reverse transcription-PCR to efficiently amplify a 3-kilobase region from the RNA polymerase gene to the poly(A) tail of small round-structured viruses (Norwalk-like viruses) J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:570–577. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.3.570-577.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bridger J C. Small viruses associated with gastroenteritis in animals. In: Saif L J, Theil K W, editors. Viral diarrheas of man and animals. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press; 1990. pp. 161–182. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carter M J, Milton I D, Meanger J, Bennett M, Gaskell R M, Turner P C. The complete nucleotide sequence of a feline calicivirus. Virology. 1992;190:443–448. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)91231-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clarke I N, Lambden P R. The molecular biology of caliciviruses. J Gen Virol. 1997;78:291–301. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-2-291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dingle K E, Lambden P R, Caul E Q, Clarke I N. Human enteric Caliciviridae: the complete genome sequence and expression of virus-like particles from a genetic group II small round-structured virus. J Gen Virol. 1995;76:2349–2355. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-76-9-2349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Estes M K, Atmar R L, Hardy M E. Norwalk and related diarrhea viruses. In: Richman D D, Whitley R J, Hayden F G, editors. Clinical virology. New York, N.Y: Churchill Livingstone; 1997. pp. 1073–1095. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fankhauser R L, Noel J S, Monroe A T, Glass R I. Molecular epidemiology of “Norwalk-like viruses” in outbreaks of gastroenteritis in the United States. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:1571–1578. doi: 10.1086/314525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Felsenstein J. PHYLIP (Phylogeny Inference Package) version 3.5c. Seattle: Department of Genetics, University of Washington; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flynn W T, Saif L J. Serial propagation of porcine enteric calicivirus-like virus in porcine kidney cells. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26:206–212. doi: 10.1128/jcm.26.2.206-212.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flynn W T, Saif L J, Moorhead P G. Pathogenesis of porcine enteric calicivirus in four-day-old gnotobiotic piglets. Am J Vet Res. 1988;49:819–825. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Green K Y. The role of human caliciviruses in epidemic gastroenteritis. Arch Virol Suppl. 1997;13:153–165. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6534-8_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Green, K. Y., T. Ando, M. S. Balayan, I. Clarke, M. K. Estes, D. O. Matson, S. Nakata, J. D. Neill, M. J. Studdert, and H.-J. Thiel. Family Caliciviridae. Seventh report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses, in press.

- 13.Hardy M E, Estes M K. Completion of the Norwalk virus genome sequence. Virus Genes. 1996;12:287–290. doi: 10.1007/BF00284649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hardy M E, Tanaka T N, Kitamoto N, White L J, Ball J M, Jiang X, Estes M K. Antigenic mapping of the recombinant Norwalk virus capsid protein using monoclonal antibodies. Virology. 1996;217:252–261. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herbert T P, Brierly I, Brown T D K. Detection of the ORF3 polypeptide of feline calicivirus in infected cells and evidence for its expression from a single, functionally bicistronic, subgenomic mRNA. J Gen Virol. 1996;77:123–127. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-77-1-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiang X, Cubitt W D, Berke T, Zhong W, Dai X, Nakata S, Pickering L K, Matson D O. Sapporo-like human caliciviruses are genetically and antigenically diverse. Arch Virol. 1997;142:1813–1827. doi: 10.1007/s007050050199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiang X, Graham D O, Wang K, Estes M K. Norwalk virus genome cloning and characterization. Science. 1990;250:1580–1583. doi: 10.1126/science.2177224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kapikian A Z, Estes M K, Chanock R M. Norwalk group of viruses. In: Fields B N, et al., editors. Fields virology. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven; 1996. pp. 783–810. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kozak M. Structural features in eukaryotic mRNAs that modulate the initiation of translation. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:19867–19870. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lambden P R, Caul E O, Ashley C R, Clarke I N. Sequence and genome organization of a human small round-structured (Norwalk-like) virus. Science. 1993;259:516–519. doi: 10.1126/science.8380940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lim B L, Cao Y, Yu T, Mo C W. Adaptation of very virulent infectious bursal disease virus to chicken embryonic fibroblasts by site-directed mutagenesis of residue 279 and 284 of viral coat protein VP2. J Virol. 1999;73:2854–2862. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.4.2854-2862.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu B L, Clarke I N, Caul E O, Lambden P R. Human enteric caliciviruses have a unique genome structure and are distinct from the Norwalk-like viruses. Arch Virol. 1995;140:1345–1356. doi: 10.1007/BF01322662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu B L, Clarke I N, Caul E Q, Lambden P R. The genomic 5′ terminus of Manchester calicivirus. Virus Genes. 1997;15:25–28. doi: 10.1023/a:1007946628253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu B L, Lambden P R, Günther H, Otto P, Elschner M, Clarke I N. Molecular characterization of a bovine enteric calicivirus: relationship to the Norwalk-like viruses. J Virol. 1999;73:819–825. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.1.819-825.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matson D O, Zhong W M, Nakata S, Numata K, Jiang X, Pickering L K, Chiba S, Estes M K. Molecular characterization of a human calicivirus with sequence relationships closer to animal caliciviruses than other known human caliciviruses. J Med Virol. 1995;45:215–222. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890450218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meyers G, Wirblich C, Thiel H J. Rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus-molecular cloning and nucleotide sequencing of a calicivirus genome. Virology. 1991;184:664–676. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90436-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neil J D. Nucleotide sequence of the capsid protein gene of two serotypes of San Miguel sea lion virus: identification of conserved and nonconserved amino acid sequences among calicivirus capsid protein. Virus Res. 1992;24:211–222. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(92)90008-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Noel J S, Liu B L, Humphrey C D, Rodriguez E M, Lambden P R, Larke I N, Dwyer D M, Ando T, Glass R I, Monroe S S. Parkville virus: a novel genetic variant of human calicivirus in the Sapporo virus clade, associated with an outbreak of gastroenteritis in adults. J Med Virol. 1997;52:173–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Numata K, Hardy M E, Nakata S, Chiba S, Estes M K. Molecular characterization of morphologically typical human calicivirus Sapporo. Arch Virol. 1997;142:1537–1552. doi: 10.1007/s007050050178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parwani A V, Flynn W T, Gadfield K L, Saif L J. Serial propagation of porcine enteric calicivirus: effects of medium supplementation with intestinal contents or enzymes. Arch Virol. 1991;120:115–122. doi: 10.1007/BF01310954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parwani A V, Saif L J, Kang S Y. Biochemical characterization of porcine enteric calicivirus: analysis of structural and nonstructural proteins. Arch Virol. 1990;112:41–43. doi: 10.1007/BF01348984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rinehart-Kim J E, Zhang W M, Jiang X, Smith A W, Matson D O. Complete nucleotide sequence and genomic organization of a primate calicivirus, Pan-1. Arch Virol. 1999;144:199–208. doi: 10.1007/s007050050497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saif L J, Bohl E H, Theil K W, Cross R F, House J A. Rotavirus-like, calicivirus-like, and 23-nm virus-like particles associated with diarrhea in young pigs. J Clin Microbiol. 1980;12:105–111. doi: 10.1128/jcm.12.1.105-111.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sibilia M, Boniotti M B, Angoscini P, Capucci L, Rossi C. Two independent pathways of expression lead to self-assembly of the rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus capsid protein. J Virol. 1995;69:5812–5815. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.9.5812-5815.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smith A W, Boyt P M. Caliciviruses of ocean origin: a review. J Zoo Wildl Med. 1990;21:3–23. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sugieda M, Nagaoka H, Kakishima Y, Ohshita T, Nakamura S, Nakajima S. Detection of Norwalk-like virus genes in the caecum contents of pigs. Arch Virol. 1998;143:1215–1221. doi: 10.1007/s007050050369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Theil K W, McCloskey C M. Abstracts of the Conference of Research Workers in Animal Diseases. 1995. 1995. Detection of SRSV in fecal specimens from recently weaned pigs by IEM using pooled weaned pig serum, abstr. 110. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thompson J D, Higgins D G, Gibson T J. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, positions-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.White L J, Ball J M, Hardy M E, Tanaka T N, Kitamoto N, Estes M K. Attachment and entry of recombinant Norwalk virus capsids to cultured human and animal cell lines. J Virol. 1996;70:6589–6597. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.10.6589-6597.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wirblich C, Thiel H J, Meyer G. Genetic map of the calicivirus rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus as deduced from in vitro translation studies. J Virol. 1996;70:7974–7983. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.11.7974-7983.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yamaguchi T, Ogawa M, Inoshima Y, Miyoshi M, Fukushi H, Hirai K. Identification of sequence changes responsible for the attenuation of highly virulent infectious bursal disease virus. Virology. 1996;223:219–223. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]