Abstract

Although the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program has maintained high standards of quality and completeness, the traditional data captured through population-based cancer surveillance are no longer sufficient to understand the impact of cancer and its outcomes. Therefore, in recent years, the SEER Program has expanded the population it covers and enhanced the types of data that are being collected. Traditionally, surveillance systems collected data characterizing the patient and their cancer at the time of diagnosis, as well as limited information on the initial course of therapy. SEER performs active follow-up on cancer patients from diagnosis until death, ascertaining critical information on mortality and survival over time. With the growth of precision oncology and rapid development and dissemination of new diagnostics and treatments, the limited data that registries have traditionally captured around the time of diagnosis—although useful for characterizing the cancer—are insufficient for understanding why similar patients may have different outcomes. The molecular composition of the tumor and genetic factors such as BRCA status affect the patient’s treatment response and outcomes. Capturing and stratifying by these critical risk factors are essential if we are to understand differences in outcomes among patients who may be demographically similar, have the same cancer, be diagnosed at the same stage, and receive the same treatment. In addition to the tumor characteristics, it is essential to understand all the therapies that a patient receives over time, not only for the initial treatment period but also if the cancer recurs or progresses. Capturing this subsequent therapy is critical not only for research but also to help patients understand their risk at the time of therapeutic decision making. This article serves as an introduction and foundation for a JNCI Monograph with specific articles focusing on innovative new methods and processes implemented or under development for the SEER Program. The following sections describe the need to evaluate the SEER Program and provide a summary or introduction of those key enhancements that have been or are in the process of being implemented for SEER.

A changing cancer surveillance landscape

To meet the evolving needs for cancer surveillance in the 21st century, the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program is addressing some of the challenges and barriers that limit the utility of registry data for supporting research and understanding the impact of new treatments across the broader population. These challenges include the rapid pace of change in cancer care, the chaotic health-care system in which cancer patients receive their care, and the lack of population-level measures of guideline compliance for monitoring care quality across all population subgroups.

To address these challenges and be more clinically relevant, the SEER Program must adopt a more agile process. SEER is working toward providing population-level data to

complement clinical trials and understand the effectiveness of cancer care for the 90%-95% of patients treated outside the clinical trial setting;

support assessment of the quality of cancer care across the health-care continuum, beyond the 250 000 patients diagnosed or treated at National Cancer Institute (NCI)–designated cancer centers (https://www.cancer.gov/research/infrastructure/cancer-centers); and

represent the data in more clinically meaningful categories (eg, instead of breast cancer incidence overall, delineate incidence and survival by the more relevant molecular subtypes).

Additionally, SEER is developing methods to provide cancer reporting in near real time through linkages and use of natural language processing tools that will enable more rapid evaluation of trends over time. Additional details on the methods to support this near real-time reporting are provided in the manuscript by Chen et al. (1) in this monograph.

To address these challenges, SEER is actively engaged in a number of areas that are described further in this monograph. With these enhancements, the population-based surveillance system can increasingly provide more clinically relevant information across the entire spectrum of cancer care. Comprehensive information at the population level will enable greater understanding of the use and effectiveness of new treatments in patients outside of clinical trials, in the real-world setting.

An example of the potential value of population-based capture of data relates to treatment guidelines that are based on results from patients in clinical treatment trials. The data represent 7% of the cancer population (2), and patients in trials are not representative of the general cancer population; they are largely White, younger, and have few or no comorbidities (3-5). Understanding guideline adherence in the real world outside academic centers as well as evaluating outcomes for approved treatments are key objectives for the SEER Program—as approximately 65%-70% of patients reported to SEER are from nonacademic facilities. These population-level data support the evaluation of

how newly approved guideline-directed biomarkers and treatment are being disseminated and

how these impact outcomes in the general cancer population.

The limited data types and detail traditionally captured and maintained in cancer registries represent another barrier to meeting contemporary research needs. SEER has traditionally collected a broad set of demographic and clinical variables, including race and ethnicity; geography; tumor characterization; generic information on initial treatment, including the initial course of chemotherapy (yes or no) and radiation therapy (modality); surgery (only the most comprehensive surgical procedure); and survival. Most of these data elements have been gathered through manual abstraction. However, with the rapidly changing cancer treatment landscape and the complexity and fragmentation throughout the US health-care system, manual data extraction is no longer feasible for achieving comprehensive data collection. Thus, SEER has initiated 2 key sets of processes, automation and linkages, to enhance the timeliness and comprehensiveness of data collection.

Because of the diverse locations and specialists from which cancer patients receive their care, key data for cancer surveillance may not be available in a hospital electronic medical record. Although some health-care systems such as health maintenance organizations or large NCI-designated cancer centers may include a more comprehensive medical record for the cancer patient, only approximately one-quarter of the more than 850 0000 cancer cases reported to SEER annually receive their care at NCI centers (https://www.cancer.gov/research/infrastructure/cancer-centers). Thus, the majority of cancer patients receive their care from heterogeneous and disconnected medical record systems.

To address these data collection challenges and ensure timely and comprehensive data capture, new methodologies including real-time linkages and automation are needed. Timely and comprehensive data capture will, in turn, enable investigation of the broad array of clinically important research questions necessary to meet leading-edge scientific needs. In addition to the cost and human resources burden associated with traditional data collection, the necessary clinical detailed data are often inaccessible to cancer registrars because key data may be held in health records to which they do not have access. An example is the OncotypeDx 21-gene assay. Manual capture of this data item represented only 43% of the actual tests performed, as identified through a direct linkage with Genomic Health Incorporated. Therefore, wherever feasible, the SEER Program supports direct linkages with the relevant data source to ensure greater accuracy, completeness, and timeliness—whether that source is a pathology laboratory, specialized genomic laboratory, or pharmacy. Detailed descriptions of these genomic and pharmacy linkages and their utility for SEER are provided in the monograph articles by Petkov and Howlader (6).

Evolution of the SEER Program: specific enhancements

The SEER Program has spearheaded several initiatives to help close gaps in the clinically relevant areas outlined previously, and these are described in more detail in the following sections.

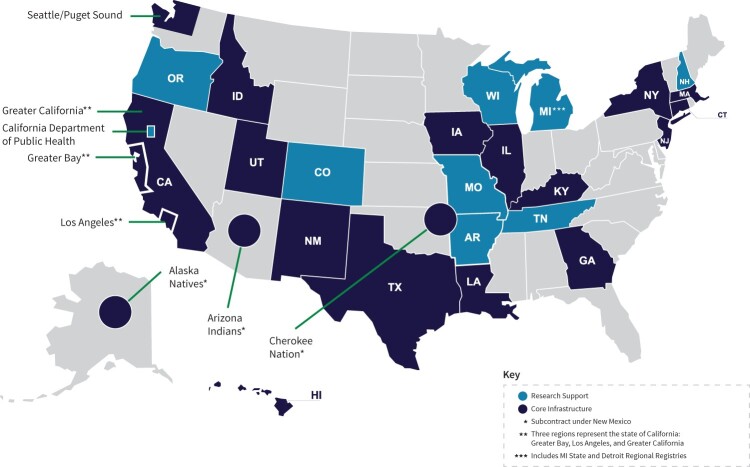

Expanding population coverage in SEER

The first major initiative for enhancing SEER has been to expand the population covered in the SEER Program. As of May 2020, the core SEER Program covers 48% of the US population, increasing the coverage from 36% in 2018. Prior to 2018, SEER represented only 28% of the US population. With this expansion, the Program receives information on more than 850 000 incident cancer cases annually (Figure 1). This expansion supports research on population subsets and on rare cancers for which sample size was previously insufficient. The data on these patients are now available to researchers who successfully apply for access through the robust authentication and authorization process, which was developed to enable access to the SEER data products using a tiered approach that provides the minimal relevant data investigators need to address their research questions (https://seer.cancer.gov/data/access.html).

Figure 1.

Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results program core infrastructure and research support registries. AR = Arkansas; CA = California; CO = Colorado; CT = Connecticut; GA = Georgia; HI = Hawaii; IA = Iowa; ID = Idaho; IL = Illinois; KY = Kentucky; LA = Louisiana; MA = Massachusetts; MI = Michigan; MO = Missouri; NH = New Hampshire; NJ = New Jersey; NM = New Mexico; NY = New York; OR = Oregon; TN = Tennessee; TX = Texas; UT = Utah; WI = Wisconsin.

All core registries are required to participate in linkages and other important work such as the National Childhood Cancer Registry (https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/research-emphasis/supplement/childhood-cancer-registry) and the Virtual Pooled Registry (VPR). The VPR is a critical program supporting linkages with cohorts, clinical trials, and other studies. It is described in detail in the manuscript by Deapen et al. (7) in this monograph. The SEER Program also includes 10 research support registries, which represent an additional 13% of the population and are eligible to participate in these special activities. Currently, 4 of 9 are under contract for these task orders (National Childhood Cancer Registry and VPR).

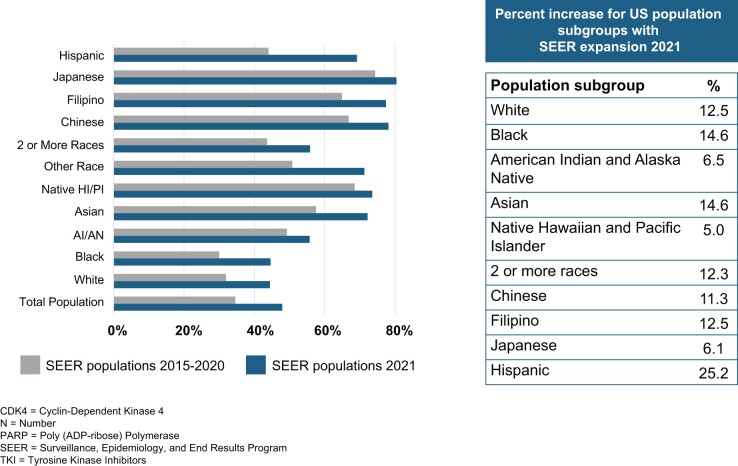

The expansion of the SEER Program core and research support registries, with the concomitant increase in number of cases, not only enables more robust representation of various population subgroups (Figure 2) but also represents an increase in the sample size for rare tumors and outcomes—permitting stratified analysis among these population subgroups that was not previously possible. As illustrated in Figure 2, the percent of each population subgroup has increased substantially, ranging from a 5% increase in Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders to a more than 25% increase in Hispanic persons.

Figure 2.

Increase in representation of population subgroups under 2020 SEER expansion. AI = American Indian; AN = Alaska Native; HI = Hawaiian; PI = Pacific Islander; SEER = Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program.

Expanding data elements in SEER

Beyond more extensively representing population subgroups, the expansion assures sufficient sample sizes to report cancer trends according to more clinically relevant categories (eg, histologic subgroups, key biomarker status, and other relevant factors) that may result in differential outcomes (8). This increase in sample size is essential as the SEER Program is continuously increasing the information categories it collects as well as the subtypes and volume of data within each of the following data categories. For example, since 2021, the SEER Program now requires collection of 4 additional guideline-directed biomarkers (anaplastic lymphoma kinase negative, estimated glomerular filtration rate, BRAF, and NRAS) in addition to the estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, HER2, KRAS, and MSI. These guideline-directed markers were selected to enable analysis of outcomes in the context of clinical information for directing therapy. Other biomarkers and genomic tests are captured via linkages directly to the laboratory performing the test. The latter are described in more detail in the manuscript by Petkov et al. (9) in this monograph.

Detailed treatment

Central cancer registries currently collect only the first course of planned treatment as a required data element, produced in a binary format (Y/N). Potential differences between planned and administered initial therapy, combined with the lack of details regarding the specific agents and combinations, make these data inadequate to understand differences in outcomes among patients with similar tumor characteristics. In addition, there is no reported information on secondary or tertiary treatments. These subsequent treatments are becoming increasingly relevant for developing a more complete understanding of cancer patients’ treatment trajectories. They are also increasingly relevant for detecting cancer recurrence and the outcomes of those recurrences by predictive models, as patients are increasingly surviving multiple recurrences. Tracking and modeling for detailed longitudinal cancer treatments and recurrence are high-need, high-impact areas within cancer surveillance. Detailed treatment data are essential for conducting cancer epidemiology research on the uptake, utilization, adverse drug events, and survival associated with more detailed treatment information.

Although the SEER Program’s coverage of detailed treatment reporting is not yet sufficient for comprehensive population-based reporting, the Program is incrementally building capacity to provide these data, largely through linkages. These treatment linkages focus on 2 areas: medical claims and pharmaceutical claims. Medical claims typically represent infusion-based chemotherapy and other systemic therapy provided by the oncologist or within the hospital setting. An example of one claims-based source for SEER is the capture of community oncology practice data from a large claims processor that has served medical practices since 2013. These data capture detailed treatment regardless of insurer but comprehensively within the participating practices. Currently, the data have been collected since 2013, represent 20 practices in 5 states, and, during a 6-month period from October 2022 to March 2023, included 4.6 million claims on approximately 600 000 cancer patients. This represents at least 1 claim on 12%-23% of cancer cases in the 5 registries. The data are being incorporated into SEER in several ways: 1) by providing detailed treatment information for first and subsequent course of chemotherapy and 2) by leveraging the longitudinal data to identify patients with a metastatic recurrence. These data are being incorporated into a special dataset in combination with other claims data (such as United Health Care [UHC], described below) and will be accessible through appropriate request and review.

In addition to oncology practice claims, the SEER Program currently links with claims from UHC, the largest commercial insurer in the United States. The data represent 12%-50% of patients across the SEER registries and include data back to 2000. Again, these data are being incorporated into the SEER data for release through a specialized process. In addition to longitudinal treatment, the claims data offer an opportunity to capture information on comorbid conditions, which may play a role in therapeutic decision making and are a critical covariate in any model predicting therapy receipt and outcomes.

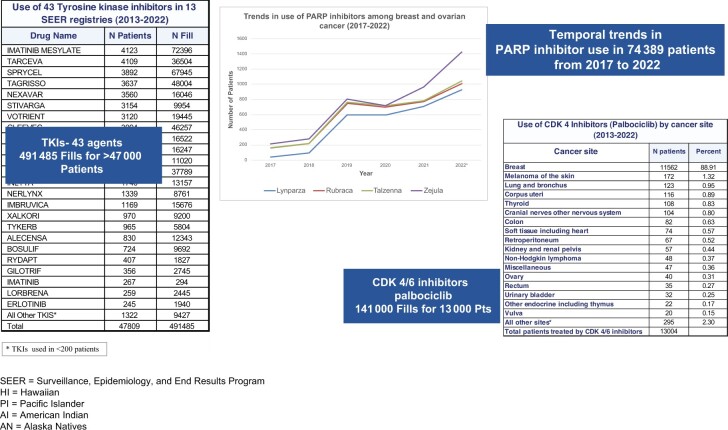

SEER has been performing a unique linkage with large commercial pharmacies, including CVS, Walgreens, and RiteAid, to capture data back to 2013. The data captured include receipt of oral antineoplastics from commercial, mail order, and for some drugs, specialty providers. Similarly, the UHC pharmacy benefit management system data are also submitted to the registries as part of the claims submission and linked for those patients insured under UHC. Although not population based (described in the manuscript by Howlader et al. (6) in this monograph), the pharmacy data alone represent a large set of information on oral antineoplastic therapy linked to clinical information regarding patient, tumor characteristics, and outcomes. These data (as shown in Figure 3) represent use cases with a number of cancers and treatments useful for monitoring outcomes in treated patients by cancer site and stage and for monitoring trends in the dissemination of treatments in use overall and by population subgroups. Further, the claims sources for medical and pharmacy claims represent an opportunity to identify not only detailed initial therapy but also treatment of progression or recurrence.

Figure 3.

SEER-linked pharmacy data (2013-2022). CDK4 = cyclin-dependent kinase 4; PARP = poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase; pts = patients; SEER = Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program; TKI = tyrosine kinase inhibitors.

Genomic and genetic factors

Understanding the interplay between genomics and specific therapies targeted to a cancer or mutation is critical for understanding variation in outcomes and for understanding differential response to many targeted therapies. Genetic mutations may also play a critical role in understanding a person’s risk of cancer, and they may influence a person’s prognosis and response to therapies. The latter may be critical as a component of therapeutic decision making. Currently, guidelines exist for many actionable tumor mutations as well as for germline mutation testing. Capturing these data at the population level offers an opportunity to monitor and benchmark the quality of cancer care in accordance with guidelines. Using California and Georgia SEER data linked to the 4 largest genetic testing companies, Kurian et al. (10,11) demonstrated that only 39% of women with ovarian cancer underwent BRCA testing, with substantial variation by race and ethnicity. Unfortunately, this was seen for other guideline-directed genetic testing across all cancers studied.

Other examples of population-level genomic testing’s utility include assessing the benefit of clinical trial results and understanding use of relevant tests in the real world outside the highly selected population subgroup in which trials are conducted, such as the verification of the Oncotype 21-gene multigene panel (12-15).

Outcomes beyond survival: distant and regional recurrence

Recurrence is an increasingly important component of monitoring the trajectory of each cancer patient’s journey, as many patients survive 1 or more recurrences. Therefore, identifying and tracking recurrence outcomes should be a key element of surveillance. More than 5% of the US population is living with a cancer diagnosis, and the lack of population-level data reflecting recurrence risk at the time of diagnosis is a substantial gap that needs to be addressed for patients, providers, and researchers. In addition to understanding and providing data on risk of recurrence, it is essential to monitor recurrence treatment outcomes. The comprehensive capture of recurrence information is challenging because of the heterogeneity by which a diagnosis is made as well as the practitioners making that diagnosis. Thus, a broad set of data sources capturing key clinical information longitudinally is essential.

Currently, registries capture recurrence in only a limited manner, via hospital-based reporting of first metastatic recurrence. Because patients may be diagnosed across multiple outpatient systems, only patients who have their metastatic recurrence diagnosed within a health-care system supporting a hospital registry are likely to be reported. Thus, the sensitivity of recurrence as currently captured is low. SEER is approaching this challenge by consolidating information from a variety of sources, none of which can comprehensively capture patients’ recurrence by itself. These sources include the hospital-based information and leveraging information from claims (using codes such as secondary malignancies and developing algorithms to capture recurrence based on timing of treatment) as well as from pathology reports and radiology reports. The latter are key, and deep-learning technology is being used to model recurrence from pathology reports to enable identification of patients diagnosed via pathologic exam, which is currently feasible in near real time. An algorithm is being developed by Oak Ridge National Laboratory under the Department of Energy–NCI partnership (described in more detail by Hsu et al. (16) in this monograph). The algorithm was trained based on 55 000 manually annotated gold standard pathology reports selected to increase the probability of capturing recurrence. In that sample, approximately 23% indicate 1 or more distant metastatic lesions. Once established, transfer learning as applied to radiology reports for this algorithm will be tested and refined, enabling capture of recurrence across a broad set of cancers and population subgroups within SEER. The SEER Program is currently developing a specialized dataset that will include a nonpopulation-based sample of patients with recurrence. It will incorporate information from the pathology report application programming interface (API) and the Commission on Cancer recurrence variable, and it will leverage claims data diagnosis codes for secondary malignancy. Over time, the goal will be to capture metastatic recurrence more comprehensively for the entire population.

Challenges to population-based data capture

Capturing the complex data representing detailed longitudinal treatment, genomic characterization of the tumor, and recurrence at the population level cannot be accomplished simply or quickly. The complexity of the US health-care system, and in particular oncology services, presents a substantial barrier to assuring that the data are available for all patients longitudinally. Capturing comprehensive and detailed longitudinal treatment or outcome data must include data from hospitals, community oncology clinics, and radiation therapy centers, among other providers. With the increasing use of oral antineoplastics, collecting data from pharmacies in particular is critical for understanding the treatments administered to patients with recurrent metastatic disease. Achieving population-level coverage for data such as oral antineoplastics or recurrence requires an incremental approach over time, leveraging multiple data sources, and collaboration with external partners such as large pharmacy chains and large insurers. The associated challenge in the meantime is that we do not know the treatment status of every patient, only those for whom we have data. Therefore, the SEER Program is developing opportunities for researchers to use nonpopulation-based information, such as the pharmacy-linked data shown in Figure 3, to answer targeted questions regarding the use and outcomes of these treatments.

Capturing data to support novel research opportunities

The SEER Program has also been exploring opportunities to leverage novel data linkages that could broaden the types of research supported by the SEER data. The first example of this type of linkage is residential history. Registries traditionally capture a person’s address at the time of cancer diagnosis but infrequently update addresses as patients move over time. Given the mobility of the US population—approximately 7%-8% of individuals move annually (17)—and the longitudinal nature of cancer and its treatment, having prospective residential history to enable and validate matches for patients after the initial treatment period is essential. Many of the data sources (eg, pharmacy, claims) may not have comprehensive personally identifiable information, specifically Social Security numbers. Without this key identifier, matches rely on other match criteria such as name, date of birth, and address to assure a valid match. Therefore, the SEER Program has captured prospective and retrospective residential history via a linkage with LexisNexis to support the need for longitudinal data capture. In addition to assuring high-quality longitudinal matching of patients, residential history captures retrospective and historical addresses accurately back to the mid-1990s. The retrospective residential history enables linkages with environmental exposure databases prior to diagnosis but at a time when initiation of the cancer likely occurred. SEER is developing a demonstration project that leverages the residential history and links to a set of environmental exposure databases, including Daily Fine Particulate Matter (PM2.5) Concentrations for the Contiguous US 1-km Grids from 2000 to 2016, and 2 databases provided by the US Environmental Protection Agency: Risk-Screening Environmental Indicators model and the Radon Zone database (18-21). These linked data will be available through a specialized research request process that includes institutional review board review and approval, as the data include geocoded address information for patients. The first phase in leveraging the residential history data in terms of relevant environmental data sources is described more fully in the article by Tatalovich et al. (22) in this monograph.

Enhancing the timeliness of SEER registry data

Another barrier to maximizing the utility of cancer registry data is the timing of surveillance data reporting, which traditionally has been delayed by up to 2 years because, historically, cancer reports (abstracts) have been submitted on completion of the initial therapeutic course. This lag limits the ability to rapidly monitor trends reflecting changes in cancer care and limits the ability to leverage these data for important activities such as eligibility assessment in clinical trials or other research studies. As a result, the SEER Program is working to accomplish 2 goals. The first is to generate statistics on incident cases in near real time. This process, described in detail in the manuscript by Chen et al. (1) in this monograph, leverages new tools for automated data extraction from source documents (23-27) as well as builds on statistical methods that adjust for the reporting delay (28-30). In addition to developing methods for close-to-real-time incidence reporting, SEER is developing methods to rapidly generate key cancer characteristics based on real-time pathology reporting, using a deep learning–based natural language processing API; the API extracts site, histology, behavior, and laterality in real time from electronic pathology reports. These data are increasingly leveraged to quickly identify patients who may be eligible for prospective research studies. Details on this process are provided in the manuscript by Hsu et al. in this monograph.

To increase the relevance and utility of the SEER data, the Program has established a strategic framework to evaluate the emergence of new clinical data sources and form pivotal data collaborations. These partnerships 1) enhance longitudinal understanding of the patient trajectory and 2) are building a clinically relevant, collaborative data resource by combining various types of health-care data (claims, pharmacy, genomic, genetic, radiology, radiation oncology, and demographic). This framework was developed by assessing current gaps and targeting data with high clinical relevance related to practice guidelines. Working collaboratively with a myriad of national data partners and developing novel methods for automating the surveillance process, the SEER Program will continue to grow as an infrastructure that provides information to support researchers, patients, and providers.

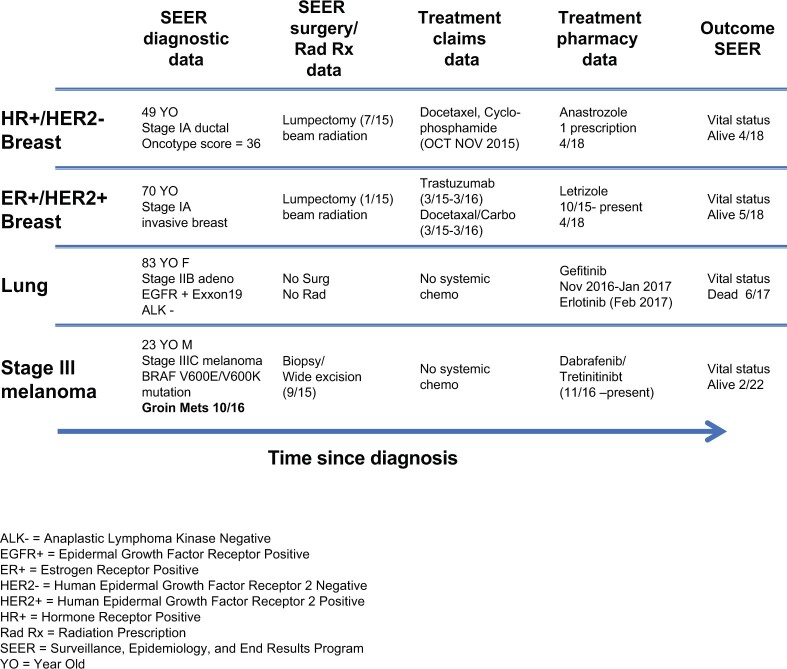

The new goals of cancer surveillance remain essentially the same as traditional surveillance, that is, capturing data that enable trends to be monitored in more clinically relevant categories and enriching the set of research questions that can be supported through SEER. These goals will be met by continuing to enhance the representativeness, type, complexity, range, quantity, timeliness, and connectivity of data used in surveillance. With advancing precision medicine efforts, genomic data—germline susceptibility and tumor genomes—will be increasingly critical and collected on individual patients. Genomic data will be combined with other complex biomarkers (omics) to define cancers based on molecular characteristics rather than anatomic site and stage, gauge possible responsiveness to therapeutic interventions (eg, in persons with HER2-positive breast cancer), and delineate possible subsets associated with different etiologic factors and environmental exposures (eg, leveraging residential history to link cancer patients with longitudinal environmental exposures). The new methods, processes, and tools described in this monograph represent unique opportunities to capture relevant information often at the population level. Cancer surveillance will need to ensure that such complex information is highly accurate, timely, and complete to provide comprehensive longitudinal data on each patient with cancer, as illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Examples of SEER representing each patient’s trajectory over the disease course. ALK- = anaplastic lymphoma kinase negative; EGFR+ = epidermal growth factor receptor positive; ER+ = estrogen receptor positive; HR+ = hormone receptor positive; Rad Rx = radiation prescription; SEER = Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program; YO = year old.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Contributor Information

Lynne Penberthy, Surveillance Research Program, Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Steven Friedman, Surveillance Research Program, Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Data availability

No new data were generated or analyzed for this commentary.

Author contributions

Steve Friedman, MHA (Project administration; Writing—review & editing) and Lynne Penberthy, MD, MPH (Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Writing—original draft; Writing—review & editing).

Funding

Funding provided by the National Cancer Institute.

Monograph sponsorship

This article appears as part of the monograph “50th Anniversary Issue of the National Cancer Institute’s SEER Program: A Half-Century of Turning Cancer Data into Discovery,” sponsored by the National Cancer Institute.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Chen H-S, , NegoitaS, , SchwartzS, et al. Toward real-time reporting of cancer incidence: methodology, pilot study, and SEER Program implementation. JNCI Monograph. 2024;2024(65):123-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Unger JM, Fleury M. Nationally representative estimates of the participation of cancer patients in clinical research studies according to the commission on cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(suppl 28):74. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Murthy VH, Krumholz HM, Gross CP. Participation in cancer clinical trials: race-, sex-, and age-based disparities. JAMA. 2004;291(22):2720-2726. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.22.2720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cottin V, Arpin D, Lasset C, et al. Small-cell lung cancer: Patients included in clinical trials are not representative of the patient population as a whole. Ann Oncol. 1999;10(7):809-815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Johnson-Mann CN, Cupka JS, Ro A, et al. A systematic review on participant diversity in clinical trials—have we made progress for the management of obesity and its metabolic sequelae in diet, drug, and surgical trials. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2023;10(6):3140-3149. doi: 10.1007/s40615-022-01487-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Howlader N, , LundJL, , EnewoldL, et al. Real-world lessons: combining cancer registry and retail pharmacy data for oral cancer drugs. JNCI Monographs. 2024;2024(65):162-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Deapen D, , ClerkinC, , HoweW, et al. Virtual Pooled Registry-Cancer Linkage System: an improved method for ascertaining cancer diagnoses. JNCI Monographs. 2024;2024(65):191-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Noone AM, Cronin KA, Altekruse SF, et al. Cancer incidence and survival trends by subtype using data from the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results Program, 1992-2013. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2017;26(4):632-641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Petkov VI, , ByunJS, , WardKC, et al. Reporting tumor genomic test results to SEER registries via linkages. JNCI Monographs. 2024;2024(65):168-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kurian AW, Abrahamse P, Furgal A, et al. Germline genetic testing after cancer diagnosis. JAMA. 2023;330(1):43-51. doi: 10.1001/jama.2023.9526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kurian AW, Ward KC, Abrahamse P, et al. Time trends in receipt of germline genetic testing and results for women diagnosed with breast cancer or ovarian cancer, 2012-2019. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(15):1631-1640. doi: 10.1200/JClinOncol.20.02785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zhang L, Hsieh MC, Petkov V, Yu Q, Chiu YW, Wu XC. Trend and survival benefit of Oncotype DX use among female hormone receptor-positive breast cancer patients in 17 SEER registries, 2004-2015. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2020;180(2):491-501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Petkov VI, Miller DP, Howlader N, et al. Erratum: Author Correction: Breast-cancer-specific mortality in patients treated based on the 21-gene assay: a SEER population-based study. NPJ Breast Cancer. 2018;4:17. Erratum for: NPJ Breast Cancer. 2016;2: 16017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Petkov VI, Miller DP, Howlader N, et al. Breast-cancer-specific mortality in patients treated based on the 21-gene assay: a SEER population-based study. NPJ Breast Cancer. 2016;2:16017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Roberts MC, Kurian AW, Petkov VI. Uptake of the 21-gene assay among women with node-positive, hormone receptor-positive breast cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2019;17(6):662-668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hsu E, , HansonH, , CoyleL, et al. Machine learning and deep learning tools for the automated capture of cancer surveillance data. JNCI Monographs. 2024;2024(65):145-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Census Bureau Releases 2021 CPS ASEC Geographic Mobility Data. U.S. Census Bureau. November 17, 2021. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2021/cps-asec-geographic-mobility.html. Accessed February 8, 2023.

- 18. Amini H, Danesh-Yazdi M, Di Q, et al. Annual Mean PM2.5 Components (EC, NH4, NO3, OC, SO4) 50m Urban and 1km Non-Urban Area Grids for Contiguous U.S., 2000–2019 v1. Palisades, NY: NASA Socioeconomic Data and Applications Center (SEDAC; ); 2023. 10.7927/7wj3-en73. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Documentation for RSEI Geographic Microdata (RSEI-GM). 2022. https://www.epa.gov/system/files/documents/2022-07/rsei-documentation-geographic-microdata-july-2022.pdf. Accessed February 8, 2023.

- 20. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. EPA’s Risk-Screening Environmental Indicators (RSEI) Methodology: RSEI. Version 2.3.10. 2022. https://www.epa.gov/system/files/documents/2022-06/RSEI%20Methodology%20V2.3.10.pdf. Accessed February 8, 2023.

- 21. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. EPA’s Map of Radon Zones National Summary. 1993. https://nepis.epa.gov/Exe/ZyPDF.cgi/0000098R.PDF?Dockey=0000098R.PDF. Accessed February 8, 2023. Interactive EPA radon map available at https://gispub.epa.gov/radon/.

- 22. Tatalovich Z, , ChtourouA, , ZhuL, et al. Landscape analysis of environmental data sources for linkage with SEER cancer patients database. JNCI Monographs. 2024;2024(65):132-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. De Angeli K, Gao S, Blanchard A, et al. Using ensembles and distillation to optimize the deployment of deep learning models for the classification of electronic cancer pathology reports. JAMIA Open. 2022;5(3):ooac075. doi: 10.1093/jamiaopen/ooac075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yoon HJ, Peluso A, Durbin EB, et al. Automatic information extraction from childhood cancer pathology reports. JAMIA Open. 2022;5(2):ooac049. doi: 10.1093/jamiaopen/ooac049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Blanchard AE, Gao S, Yoon HJ, et al. A keyword-enhanced approach to handle class imbalance in clinical text classification. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform. 2022;26(6):2796-2803. doi: 10.1109/JBHI.2022.3141976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. De Angeli K, Gao S, Danciu I, et al. Class imbalance in out-of-distribution datasets: Improving the robustness of the TextCNN for the classification of rare cancer types. J Biomed Inform. 2022;125:103957. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2021.103957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. De Angeli K, Gao S, Alawad M, et al. Deep active learning for classifying cancer pathology reports. BMC Bioinformatics. 2021;22(1):113. doi: 10.1186/s12859-021-04047-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Clegg LX, Feuer EJ, Midthune DN, Fay MP, Hankey BF. Impact of reporting delay and reporting error on cancer incidence rates and trends. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94(20):1537-1545. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.20.1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lewis DR, Chen HS, Cockburn MG, et al. Early estimates of SEER cancer incidence, 2014. Cancer. 2017;123(13):2524-2534. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lewis DR, Chen HS, Cockburn M, et al. Preliminary estimates of SEER cancer incidence for 2013. Cancer. 2016;122(10):1579-1587. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were generated or analyzed for this commentary.