ABSTRACT

Objectives.

To evaluate the presence and sensitivity to antimicrobials of Escherichia coli strains isolated from 24 irrigation water samples from the Rimac river of East Lima, Peru.

Materials and methods.

The E. coli strains were identified by PCR. Antibiotic susceptibility was processed by the disk diffusion method. Genes involved in extended spectrum beta-lactamases (BLEE), quinolones and virulence were determined by PCR.

Results.

All samples exceeded the acceptable limits established in the Environmental Quality Standards for vegetable irrigation. Of the 94 isolates, 72.3% showed resistance to at least one antibiotic, 24.5% were multidrug resistant (MDR) and 2.1% were extremely resistant. The highest percentages of resistance were observed for ampicillin-sulbactam (57.1%), nalidixic acid (50%), trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (35.5%) and ciprofloxacin (20.4%). Among the isolates, 3.2% had a BLEE phenotype related to the bla CTX-M-15 gene. qnrB (20.4%) was the most frequent transferable mechanism of resistance to quinolones, and 2.04% had qnrS. It was estimated that 5.3% were diarrheagenic E. coli and of these, 60% were enterotoxigenic E. coli, 20% were enteropathogenic E. coli and 20% were enteroaggregative E. coli.

Conclusions.

The results show the existence of diarrheogenic pathotypes in the water used for irrigation of fresh produce and highlight the presence of BLEE- and MDR-producing E. coli, demonstrating the role played by irrigation water in the dissemination of resistance genes in Peru.

Keywords: Escherichia coli, antibiotic resistance, irrigation water, ESBL-producers, diarrhoeagenic E. coli.

INTRODUCTION

The emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria is a threat to global public health, which needs a multidisciplinary approach to integrate knowledge about “One Health”, including the environment, humans, and animals 1. Aquatic systems have been identified as important reservoirs of resistance 2,3, providing dissemination and transmission routes for antimicrobial-resistant bacteria to transfer to humans and animals 4.

The spread of antibiotic resistance in aquatic systems deserves special attention considering that water use can facilitate the transmission of bacteria to humans (e.g., in oral use, irrigation, recreation, and/or fishing) 5-7. Likewise, the presence of other compounds in these environments, such as metals and/or disinfectants, has been related to the co-selection or selection of resistance, which accumulates in contaminated aquatic systems 8,9. In addition, the origin of some of the most widespread antibiotic resistance genes associated with human infections (e.g., bla CTX -M) has been identified in aquatic environmental bacteria 10.

The Rimac River is the most important river basin in Peru. It is estimated that 15% of its water resources are used in agriculture, being the main source of water for agriculture in eastern Lima 11. The indicators of fecal contamination in this river exceed the category limits for vegetable irrigation (1000 most probable number [MPN]/100 ml) established by the Water Quality Standards of the Peruvian Ministry of the Environment 11.

It should be noted that not only pathogenic microorganisms are relevant for the mobilization of resistance mechanisms, but also commensal bacteria such as Escherichia coli, which is considered one of the most representative species of the gut microbiota in both humans and animals 12. The presence of E. coli is used as an indicator of water and food quality and some pathotypes are virulence factors associated with diarrhea (diarrheogenic E. coli).

The cephalosporins and quinolones are among the most widely used antimicrobials in humans and production animals. The extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBL) are one of the most important resistance mechanisms in health and are widely distributed in the community; they confer resistance to beta-lactam antibiotics, as well as the mechanisms associated with resistance to aminoglycosides and quinolones, mainly due to chromosomal mutations, in addition to transferable mechanisms 13,14.

A better understanding of antibiotic resistance in specific irrigation systems is essential to create mitigation strategies in agriculture. In Peru, information on resistance levels in bacteria isolated from water bodies is limited, particularly regarding irrigation water 12. Therefore, this study aims to determine the levels of antibiotic resistance and to carry out the molecular characterization of ESBL and transferable mechanisms of quinolone resistance in E. coli isolated from irrigation water in eastern Lima, Peru.

KEY MESSAGES

Motivation for the study. Aquatic systems, including irrigation water, have been identified as reservoirs of antimicrobial resistance, with few studies in Peru on the presence of Escherichia coli and their levels of virulence and antimicrobial resistance.

Main findings. Our results show the presence of E. coli above the established standard for vegetable irrigation water, some with very high levels of antimicrobial resistance.

Implications. The presence of ESBL-producing strains of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases and multidrug-resistant E. coli in irrigation water could contribute to the dissemination of resistance genes in Peru, posing a significant threat to public health.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study area

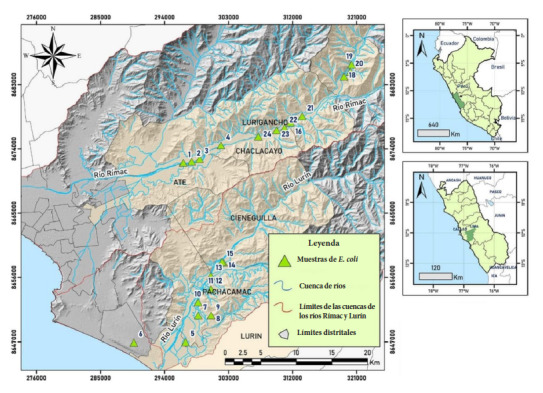

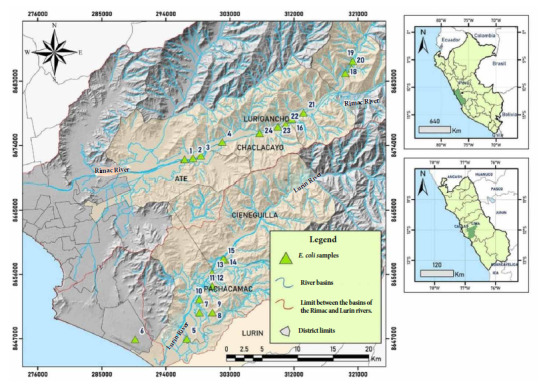

We conducted a cross-sectional observational study. Water samples were collected from 24 irrigation water sampling points in 5 vegetable-growing areas from the districts of Lurigancho, Chaclacayo, Pachacamac, La Molina and Lurin, located on the eastern bank of the Rimac River in eastern Lima Peru, between October 2019 and February 2020 (Figure 1). The samples were obtained from the largest agricultural fields, particularly from irrigation canals entering these large parcels mainly with produce and short-stemmed vegetables. We should mention that no drinking water sources were found nearby nor was there any indication of the presence of sheep, cattle or other livestock.

Figure 1. Map with irrigation water sampling points in the east of Lima, Peru.

This study was approved by the Vice-rector for Research and Postgraduate Studies of the Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos under code B19101681.

Isolation and identification of Escherichia coli

Samples were collected following protocol RD160-2015-DIGESA and transported to the Microbial Ecology laboratory of the Faculty of Biological Sciences of the Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos 15. Samples were processed using the Colilert-18/Quanti-Tray method to analyze total coliforms and E. coli in all types of water (ISO 9308-2:2012). Strains phenotypically suspected to be E. coli were selected and stored on trypticase soy agar (TSA) at 8 °C for antibiotic susceptibility testing and at -80 °C in skim milk for molecular testing performed at the Molecular Genetics Laboratory of the Universidad Científica del Sur.

E. coli was molecularly identified by amplification of the uidA gene. DNA extraction was performed by heat shock for 5 min at 100°C, followed by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 5 min. The extracted DNA was stored at -20 °C until use. We used the 652-bp uidA-R primers CCA TCA GCA CGT TAT CGA ATC CTT 61 82.6µM uidA-F from a 652-bp amplicon to amplify the uidA gene, which encodes the 3-glucuronidase enzyme as a target for E. coli detection 16.

Antimicrobial susceptibility

Confirmed E. coli strains were reactivated on TSA agar and antibiogram was performed with the Kirby Bauer disk diffusion method against 17 antibiotics: nalidixic acid (30 µg), trimethoprim sulfamethoxazole (1. 25/75 µg), ciprofloxacin (5 µg), ampicillin-sulbactam (10/10 µg), cefepime (30 µg), amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (20/10 µg), levofloxacin (5 µg), gentamicin (10 µg), fosfomycin (200 µg), aztreonam (30 µg), cefotaxime (30 µg), cefazolin (30 µg), cefoxitin (30 µg), ceftazidime (30 µg), imipenem (10 µg), meropenem (10 µg) and amikacin (30 µg). Inhibition halos were interpreted following the CLSI 2019 guideline 38. The Jarlier method was used for phenotypic detection of ESBL. The double-disk synergy method was used for AmpC-type beta-lactamases, and carbapenemase screening was considered with imipenem and meropenem inhibition halos < 22 mm. The control strains were E. coli ATCC 25922 and ATCC 35218. To obtain an overview, strains with intermediate and resistant inhibition halos were included in the resistant category. Multidrug resistance (MDR) was defined as the absence of acquired sensitivity to at least one agent in three or more antimicrobial categories, extreme resistance (XDR) was defined as resistance to three or more antimicrobial families, including carbapenemics 1,17,18.

Diarrheogenic pathotype of Escherichia coli

Eight virulence genes associated with diarrheogenic E. coli (DEC) genes were detected by multiplex PCR: enterotoxigenic (lt, st), enteropathogenic (eaeA), Shiga toxin-producing (stx1, stx2), enteroinvasive (ipaH), enteroaggregative (aggR) and diffusely adherent (daaD) E. coli19.

ESBL and transferable quinolone resistance mechanisms

Molecular characterization of E. coli ESBL genes was carried out in strains presenting the ESBL phenotype. Amplification was performed by PCR for bla CTX -M, bla TEM and bla SHV20. The presence of qnrA, qnrB, qnrC, qnrD, qnrVC, qnrS, qepA, and oqxAB genes was determined by PCR in strains with decreased susceptibility (resistance or intermediate) to nalidixic acid 14.

RESULTS

Isolation and identification of Escherichia coli

Total fecal coliform and E. coli counts exceeded 2400 NMP/100 ml in the 24 processed water samples. We isolated 118 suspected E. coli colonies from among the Colilert-positive samples; of these, 95 (79.2%) were confirmed by molecular identification of the uidA gene.

Antimicrobial Susceptibility

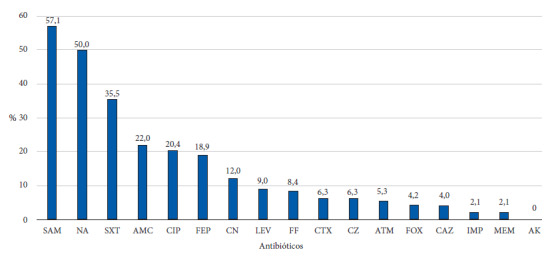

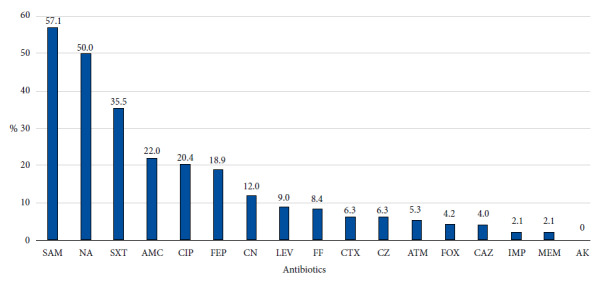

Significant levels of resistance to ampicillin sulbactam (57.1%), nalidixic acid (50.0%), trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (35.5%), amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (22.0%) and ciprofloxacin (20.4%) were found. With regard to beta-lactams, we found that resistance to cefepime was 18.9%, followed by cefazolin and cefotaxime with 6.3% resistance. The only antibiotic with no resistance was amikacin (0%) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Levels of resistance to antibiotics in Escherichia coli isolated from irrigation water in Eastern Lima 2019-2020.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing found that 68 (72.3%) strains were resistant to at least one antibiotic. Notably, 23 (24.5%) strains were MDR and 2 (2.1%) were XDR. Finally, 26 (27.6%) strains were sensitive to all antibiotics. (Supplementary material).

Determination of the diarrheogenic pathotype in Escherichia coli

Of the 94 E. coli isolates, 5 (5.3%) had at least one diarrheogenic virulence gene, and of these, 3 (60%) had the enterotoxigenic virulence gene (lt, st) being ETEC, 1 (20.0%) enteropathogenic (eaeA) EPEC and 1 (20.0%) enteroaggregative (aggR) EAEC.

Detection of ESBL and AmpC

Regarding beta-lactam resistance mechanisms, AmpC-type beta-lactamases were detected phenotypically in 5 (5.3%) strains and the ESBL phenotype in 3 (3.2%) strains. In addition, all ESBL -producing strains had the bla CTX-M-15 gene.

Transferable mechanisms of quinolone resistance (TMQR)

Of the 49 strains with decreased sensitivity to quinolones, 10 strains had the qnrB gene (20.4%), being the most frequent, and only one strain (2.0%) had the qnrS gene.

DISCUSSION

The presence of E. coli in aquatic environments has been related to the discharge of wastewater, whether from domestic or industrial use, releasing antibiotic-resistant bacteria into the environment 21. It should be noted that samples were obtained from agricultural waters that were directly exposed to the environment, so the contamination could have had different origins, such as the introduction of sewage, domestic discharges, and household and/or wild animal excrement 21,22.

The number of total coliforms and E. coli in the 24 irrigation water sampling points exceeded the permissible limit established by national regulations (DS N°004-2017-MINAM for vegetable irrigation) 23, in agreement with previous reports from national agencies 24. The poor quality of water used for irrigation is one of the reasons for the presence of pathogens in short-stemmed vegetables, which can be contaminated at any stage of the food chain, from planting to the consumer 25. In addition, contamination of irrigation water and the prevalence of E. coli in vegetables affects human health 26.

In addition, diarrheogenic E. coli strains were detected (5.3%). These strains are characterized by their capacity to cause pathologies in animals and humans through the transmission of foodborne diseases, thus compromising the use of water for vegetable irrigation. This percentage is lower in comparison with other countries in the region, such as Chile, which reported 10% of diarrheogenic E. coli strains in surface water used for vegetable irrigation using a tangential filtration method, 27) which tends to concentrate the bacterial load, and 14% found in irrigation water in Sinaloa, Mexico. Our findings show that ETEC was the most frequently isolated pathotype, although EPEC and EAEC have also been reported. Previous studies of diarrheogenic E. coli in a cohort of children in Lima have described these pathotypes, with ETEC being more frequent in children 2 to 12 months of age with diarrhea 28. High levels of resistance to sulfonamides were found in these strains, and also to quinolones which are not commonly used in this age group 28.

The presence of antibiotic resistance and the respective genes involved is generally linked to anthropogenic effect, such as human feces and sewage 21 and is also related to a high load of contaminants (heavy metals, antibiotics and pesticides) in waters, mainly due to industry activities (mining), population growth and agricultural activities 29. It is important to note that, in our study, the sampled area had no hospital or industrial waste channels 29.

In recent years, increased levels of antimicrobial resistance in irrigation water have been reported in Texas 30 and also in the Latin American region 31. Thus, in the present study, 72.3% of E. coli strains were resistant to at least one antibiotic, 24.5% were MDR, and 2.1% were XDR. In fact, resistance levels are extremely high in most river systems (up to 98% of the total bacteria detected), followed by lakes, with lower values reported in ponds and springs (<1%) 32.

The most frequent resistance phenotypes in this study were related to quinolones and sulfonamides. The presence of genes related to sulfonamide resistance has been associated with wastewater effluents (neither chlorinated nor dechlorinated) 33. On the other hand, resistance to quinolones has increased in relation to the therapeutic use and growth promoters, which has been increasing worldwide 34. High levels of quinolone resistance have been reported in microorganisms isolated from both diarrheic and healthy children 35-36 in Peru, as in other areas of the region, indicating the high pressure of this antibiotic in the population.

Aquatic environments have been considered important reservoirs regarding the transferable mechanisms involved in quinolone resistance 37. Water genetic studies have reported the presence of the qepA and aac (6')-Ib-cr genes, encoding fluoroquinolone resistance, in a high percentage of sewage and sludge samples 38. Our results show that the qnrB gene (20.4%) was the most frequent transferable mechanism of quinolone resistance (TMQR), and only one isolate had the qnrS gene. A correlation was previously established between the presence of a TMQR, such as qepA and qnrS, and the amount of Cu and Zn in vegetative soils with long-term manure application, correlating heavy metals with the persistence of antibiotic resistance genes 39.

Our findings of ESBL strains (3.2%) were lower compared with the reports by Palacios (16.1%) in water from the Piura River, Peru 34, and the 29% ESBL found in E. coli from irrigation water from Ecuador 40. However, these results are not comparable because, in these studies, they were selected with media containing antibiotics of the cephalosporin family. Likewise, the bla CTX-M-15 gene was detected, which together with the bla CTX-M-55, bla CTX-M-65 genes were the genes most frequently found in association with the ESBL phenotype, and were also the most frequent alleles associated with human infections 3,14,41.

The study presents some limitations related to the size of the samples, considering the large extension of the area. In addition, screening culture media were not used for the detection of ESBL strains, which would have helped to isolate a greater number of E. coli resistant to this group of antimicrobials. Nonetheless, the importance of this study lies in the contribution of our findings to the scarce existing information on E. coli in irrigation waters with resistance to different families of antibiotics (quinolones, aminoglycosides, beta-lactams, monobactams, sulfonamides). Likewise, the finding of E. coli pathotypes highlights the need to improve irrigation water policies and control in the different agricultural areas of Lima. This is particularly important in Peru, which has a low frequency of wastewater treatment.

In conclusion, this study showed the presence of fecal coliforms above the permissible limit established by the national standard. In addition, it demonstrates the existence of diarrheagenic E. coli and high levels of resistance to quinolones and sulfonamides, with special concern to ESBL-producing E. coli, in irrigation water from the periphery of Lima, representing a potential danger to animal and human health.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by the Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos “Proyecto de Investigación para Grupos 2019” (Project number B19101681)

Funding.: This study was supported by the Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos “Proyecto de Investigación para Grupos 2019” (Project number B19101681).

Huaman M, Salvador G, Morales L, Alba-Luna J, Velásquez L, Pacheco D, et al. Resistance to cephalosporins and quinolones in Escherichia coli isolated from irrigation water from the Rímac river in east Lima, Peru. Rev Peru Med Exp Salud Publica. 2024;41(2):114-20. doi: 10.17843/rpmesp.2024.412.13246.

References

- 1.Pons MJ, de Toro M, Medina S, Sáenz Y, Ruiz-Blázquez J. Antimicrobials, antibacterial resistance and sustainable health. South Sustainability. 2020;1(1):e001. doi: 10.21142/SS-0101-2020-001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marti E, Variatza E, Balcazar JL. The role of aquatic ecosystems as reservoirs of antibiotic resistance. Trends Microbiol. 2014;22(1):36–41. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2013.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Freitas DY, Araújo S, Folador ARC, Ramos RTJ, Azevedo JSN, Tacão M, et al. Extended Spectrum Beta-Lactamase-Producing Gram-Negative Bacteria Recovered From an Amazonian Lake Near the City of Belém, Brazil. Front Microbiol. 2019;28(10):364–364. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Larsson DGJ, Flach CF. Antibiotic resistance in the environment. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2022;20(5):257–269. doi: 10.1038/s41579-021-00649-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duarte AC, Rodrigues S, Afonso A, Nogueira A, Coutinho P. Antibiotic Resistance in the Drinking Water: Old and New Strategies to Remove Antibiotics, Resistant Bacteria, and Resistance Genes. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2022;15(4):393–393. doi: 10.3390/ph15040393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blaustein RA, Shelton DR, Van Kessel JA, Karns JS, Stocker MD, Pachepsky YA. Irrigation waters and pipe-based biofilms as sources for antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Environ Monit Assess. 2016;188(1):56–56. doi: 10.1007/s10661-015-5067-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li Y, Zhang C, Mou X, Zhang P, Liang J, Wang Z. Distribution characteristics of antibiotic resistance bacteria and related genes in urban recreational lakes replenished by different supplementary water source. Water Sci Technol. 2022;85(4):1176–1190. doi: 10.2166/wst.2022.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jiao YN, Chen H, Gao RX, Zhu YG, Rensing C. Organic compounds stimulate horizontal transfer of antibiotic resistance genes in mixed wastewater treatment systems. Chemosphere. 2017;184:53–61. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.05.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gupta S, Graham DW, Sreekrishnan TR, Ahammad SZ. Effects of heavy metals pollution on the co-selection of metal and antibiotic resistance in urban rivers in UK and India. Environ Pollut. 2022;28:119326–119326. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2022.119326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Poirel L, Kämpfer P, Nordmann P. Chromosome-encoded Ambler class A beta-lactamase of Kluyvera georgiana, a probable progenitor of a subgroup of CTX-M extended-spectrum beta-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46(12):4038–4040. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.12.4038-4040.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.MdDAy Riego. Resultado del monitoreo de la calidad del agua en la cuenca del río Rímac: Informe Técnico. Lima: Autoridad Nacional del Agua, Dirección de Gestión de Calidad de los Recursos Hídricos; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Castillo AK, Espinoza K, Chaves AF, Guibert F, Ruiz J, Pons MJ. Antibiotic susceptibility among non-clinical Escherichia coli as a marker of antibiotic pressure in Peru (2009-2019): one health approach. Heliyon. 2022;8(9):e10573. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e10573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Foudraine DE, Strepis N, Stingl C, Ten Kate MT, Verbon A, Klaassen CHW, et al. Exploring antimicrobial resistance to beta-lactams, aminoglycosides and fluoroquinolones in E. coli and K. pneumoniae using proteogenomics. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):12472–12472. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-91905-w. 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Palma N, Pons MJ, Gomes C, Mateu J, Riveros M, García W. Resistance to quinolones, cephalosporins and macrolides in Escherichia coli causing bacteraemia in Peruvian children. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2017;11:28–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2017.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DIGESA . Protocolo para la toma de muestra. Resolución Directoral. Lima: Ministerio de Salud; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bej AK, DiCesare JL, Haff L, Atlas RM. Detection of Escherichia coli and Shigella spp in water by using the polymerase chain reaction and gene probes for uid. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57(4):1013–1017. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.4.1013-1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing . CLSI supplement M100 (ISBN 978-1-68440-105-5. 31. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: USA; 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Magiorakos AP, Srinivasan A, Carey RB, Carmeli Y, Falagas ME, Giske CG. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:268–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guion CE, Ochoa TJ, Walker CM, Barletta F, Cleary TG. Detection of diarrheagenic Escherichia coli by use of melting-curve analysis and real-time multiplex PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46(5):1752–1757. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02341-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pons MJ, Vubil D. Guiral E et al Characterisation of extended-spectrum ß-lactamases among Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates causing bacteraemia and urinary tract infection in Mozambique. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2015;3(1):19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2015.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karkman A, Pärnänen K, Larsson DGJ. Fecal pollution can explain antibiotic resistance gene abundances in anthropogenically impacted environment. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):80–80. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07992-3. 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vega-Sánchez V, Talavera-Rojas M, Barba-León J, Zepeda-Velázquez AP, Reyes-Rodríguez NE. La resistencia antimicrobiana en Escherichia coli aislada de canales y heces bovinas de rastros en el centro de México. Rev Mex Cienc Pecu. 2020;11(4):991–1003. doi: 10.22319/rmcp.v11i4.5073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Md Ambiente. Aprueban Estándares de Calidad Ambiental (ECA) para Agua y Establecen Disposiciones Complementarias. DS N° 004-2017-MINAM. Lima: MINAM; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 24.MdDAy Riego. Resultado del monitoreo de la calidad del agua en la cuenca del río Rímac: Informe técnico. Informe Técnico. Lima: Autoridad Nacional del Agua, Dirección de Gestión de Calidad de los Recursos Hídricos; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Graczyk Z, Graczyk TK, Naprawska A. A role of some food arthropods as vectors of human enteric infections. Cent Eur J Biol. 2011;6:145–149. doi: 10.2478/s11535-010-0117-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Escobedo C, Ariza E. Nivel de contaminación fecal en hortalizas expedidas en mercados de Huanuco y su relación en el riego con aguas residuales no tratadas. Investigación Valdizana. 2014;8(2) [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rojas-Aedo J, Morales O, Jara M, Morales O, Martínez MC. Detección de Salmonella spp. y E. coli diarreogénico en cursos de aguas superficiales de la Región Metropolitana por Ultrafiltración Tangencial. Conference: Sociedad de Microbiología de Chile. 2013;1 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ochoa TJ, Ecker L, Barletta F, Mispireta ML, Gil AI, Contreras C. Age-related susceptibility to infection with diarrheagenic Escherichia coli among infants from Periurban areas in Lima, Peru. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49(11):1694–1702. doi: 10.1086/648069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deblonde T, Cossu-Leguille C, Hartemann P. Emerging pollutants in wastewater a review of the literature. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2011;214(6):442–448. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2011.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Duffy EA, Lucia LM, Kells JM, Castillo A, Pillai SD, Acuff GR. Concentrations of Escherichia coli and genetic diversity and antibiotic resistance profiling of Salmonella isolated from irrigation water, packing shed equipment, and fresh produce in Texas. J Food Prot. 2005;68(1):70–79. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-68.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Díaz-Gavidia C, Barría C, Weller DL, Salgado-Caxito M, Estrada EM, Araya A. Humans and Hoofed Livestock Are the Main Sources of Fecal Contamination of Rivers Used for Crop Irrigation: A Microbial Source Tracking Approach. Front Microbiol. 2022;30(13):768527–768527. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.768527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nnadozie CF, Odume ON. Freshwater environments as reservoirs of antibiotic resistant bacteria and their role in the dissemination of antibiotic resistance genes. Environ Pollut. 2019;254(B):113067–113067. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.11306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fahrenfeld N, Ma Y, O'Brien M, Pruden A. Reclaimed water as a reservoir of antibiotic resistance genes: distribution system and irrigation implications. Front Microbiol. 2013;28(4):130–130. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Riaz L, Mahmood T, Khalid A, Rashid A, Ahmed-Siddique MB, Kamal A. Fluoroquinolones in the environment A review on their abundance, sorption and toxicity in soil. Chemosphere. 2018;191:704–720. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.10.09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pons M, Mosquito S, Gomes C, Del Valle LJ, Ochoa TJ, Ruiz J. Analysis of quinolone-resistance in commensal and diarrheagenic Escherichia coli isolates from infants in Lima, Peru. Trana R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2014;108(1):22–28. doi: 10.1093/trstmh/trt106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pons M, Mosquito S, Ochoa T. Niveles de Resistencia a antimicrobianos, en especial a quinolonas, en cepas de Escherichia coli comensales en niños de la zona periurbana de Lima, Perú. Rev Peru Med Exp Salud Pública. 2012;29(1):82–86. doi: 10.1590/s1726-46342012000100012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miranda CD, Concha C, Godoy FA, Lee MR. Aquatic Environments as Hotspots of Transferable Low-Level Quinolone Resistance and Their Potential Contribution to High-Level Quinolone Resistance. Antibiotics. 2022;11(11):1487–1487. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics11111487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kraupner N, Ebmeyer S, Bengtsson-Palme J, Fick J, Kristiansson E, Flach CF. Selective concentration for ciprofloxacin resistance in Escherichia coli grown in complex aquatic bacterial biofilms. Environ Int. 2018;116:255–268. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2018.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dong Z, Wang J, Wang L, Zhu L, Wang J, Zhao X. Distribution of quinolone and macrolide resistance genes and their co-occurrence with heavy metal resistance genes in vegetable soils with long-term application of manure. Environ Geochem Health. 2021:24–24. doi: 10.1007/s10653-021-01102-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Palacios Farias SE. "Frecuencia de Escherichia coli resistente a antibióticos aisladas del agua del río Piura, Perú en un tramo de la ciudad". Universidad Nacional de Piura; 2019. http://repositorio.unp.edu.pe/handle/UNP/1957 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Montero L, Irazabal J, Cardenas P, Graham JP, Trueba G. Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamase Producing-Escherichia coli Isolated From Irrigation Waters and Produce in Ecuador. Front Microbiol. 2021;4(12):709418–709418. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.709418. Erratum in: Front Microbiol. 2022 Jun 14;13:926514. PMID: 34671324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]