SUMMARY

From triage to ED disposition, best practices in end-of-life and palliative care for seriously ill patients have existed. However, some areas require more exploration and study. The continuous and sustainable enhancement of care for seriously ill patients has impacted the entire patient care process within the ED.

Keywords: Palliative care, Emergency medicine, End-of-life care, Emergency department

INTRODUCTION

Three-quarters of patients over the age of 65 visit the ED in the last six months of life.1,2 Approximately 20% of hospice residents have emergency department (ED) visits.3 These patients must decide whether to receive emergency care that prioritizes life support, which may not achieve their desired outcomes and might even be futile.1 The patients in these end-of-life stages could benefit from early palliative care or hospice consultation before they present to the ED. Early integration of palliative care at the time of ED visits is important in determining the goals of treatment.4–6 In this article, we summarize the current evidence and knowledge about palliative care that is useful in actual clinical practice in the ED, including assessing of palliative care needs in the ED, communicating difficult news, suffering in the last days of life, palliating pain and dyspnea management, caring for hospice patients, and quality metrics for palliative care in the ED.

Palliative care is an interdisciplinary approach encompassing physical, emotional, spiritual, and socioeconomic aspects focused on minimizing suffering for those with serious illness and their loved ones, while simultaneously promoting the best possible quality of life.7 Two forms of palliative care delivery are commonly recognized: primary palliative care and specialty palliative care.8 Primary palliative care is the term for the basic palliative care skills that can be provided in any setting of care, including emergency care, thereby improving the quality of care for overall patients. Primary palliative care, which addresses suffering or distress as well as providing support and shared medical decision-making, helps patients establish their goals and values for treatment and outcomes. 8–12

ASSESSING OF PALLIATIVE CARE NEEDS IN THE EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT

In the ED, assessing for unmet palliative care needs and addressing those needs with either primary palliative care interventions or referral to specialty palliative care can positively impact the lives of patients with serious illness.13–18 In terms of screening for palliative care needs, 3 ED palliative care screening tools have undergone more rigorous study and focused on identifying ED patients at high risk of poor outcomes: The “Surprise Question,” “The Palliative Care and Rapid Emergency Screening (P-CaRES) Tool,” and “The Screening for Palliative Needs in the Emergency Department (SPEED) Instrument.”14,19–21 The latter 2 also assess for unaddressed palliative symptoms, such as spiritual distress.19–21 Most ED-palliative care screening tools are modestly good at predicting mortality, a proxy outcome for unmet palliative care needs,14 and improve accurate and prompt referral to palliative care consultation.22–24 Ultimately, the ideal screening tool for palliative care needs will require additional investigation and may depend on hospital-specific factors, such as the patient mix and availability of palliative care consultation. In-depth palliative symptom assessment is less specifically developed or tested in the ED.21 Comprehensive palliative symptom assessments require time and are not well suited to ED practice.25 Even though patients with serious illnesses are often dealing with more than one burdensome symptom, using some sort of symptom assessment tool is preferable.26 One reasonable strategy for symptom assessment is to include questions about each symptom’s dimensions (eg, timing, triggers, severity) as well as their meaning (eg, “how does this symptom affect your life?”). Developing an assessment strategy that incorporates psychosocial, spiritual/existential, and caregiver symptom questions is also critical.27

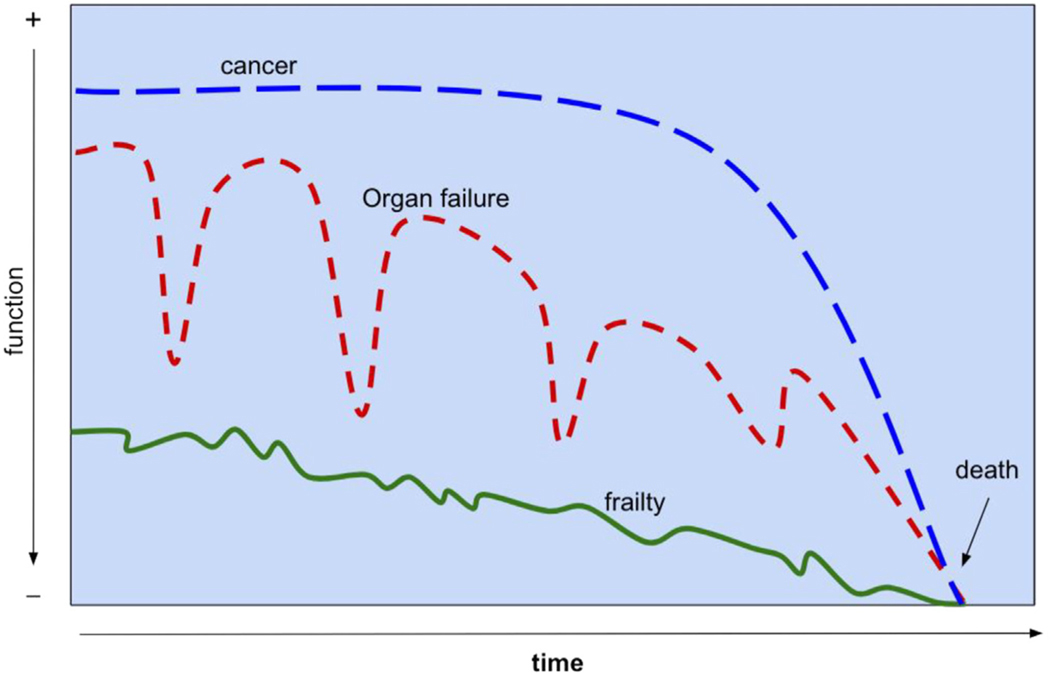

Finally, the prognosis for serious illness varies by disease and person, yet the dominant patterns of trajectories have been recognized (Fig. 1). Commonly used palliative care assessments focus on “performance status” and can be a helpful tool in developing a global sense of prognosis and trajectory in a patient with terminal disease.28 In the ED, prognostication is useful to estimate life expectancy, anticipate health deterioration, and prepare for anticipatory symptoms. The prognostication is also helpful in navigating treatment decisions by weighing the risks and benefits.29 Sharing prognostic information hastily and then shared decision-making requires key steps in high-quality communication.30,31

Fig. 1.

Common trajectories in serious illness. (Adapted from Lunney JR, Lynn J, Foley DJ, Lipson S, Guralnik JM. Patterns of Functional Decline at the End of Life. JAMA.2003;289(18):2387–2392. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.289.18.2387.)

COMMUNICATING DIFFICULT NEWS

The patient-centered communication skills to foster mutual understanding between seriously ill patients and their clinicians are known as “serious illness communication skills.” Thoughtful incorporation of serious illness communication skills will allow emergency clinicians to provide acute care most consistent with patients’ values and preferences.

Breaking Bad News

As in Box 1, an example of a case highlights the importance of serious illness communication skills. These disclosures of unanticipated, bad news are difficult for seriously ill patients and emergency clinicians for the following reasons.6

Box 1. An example of a case that highlights the importance of serious illness communication skills.

Mr. B is a 65 year old man with stage 3 non-small cell lung cancer, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) on home O2, and recently hospitalized/discharged home for COPD exacerbation.

He presents to the emergency department (ED) with a new chest and abdominal pain for the last 3 days after being discharged from the hospital. The patient describes the insidious onset of sharp pain that’s worse with breathing, associated with a mild cough and worsening dyspnea on exertion, with radiation pain down to his epigastric area.

Oncology history: Per the most recent oncology team note, the patient is on a clinical trial for immunomodulator therapy and is doing well so far for the last 8 months. The oncologist is planning on the third-line treatment if he ever fails the current treatment as the patient’s functional status has been quite good despite his age and comorbid conditions.

In the ED, patient’s vitals were stable with unremarkable examination other than mild end-expiratory wheezes, which seemed to be at his baseline. The ED work-up revealed segmental pulmonary embolisms and new hepatic mass likely metastatic indicating progression of his cancer.

Data from [Kei Ouchi, MD] [Prachanukool T, Aaronson EL, Lakin JR, et al. Communication Training and Code Status Conversation Patterns Reported by Emergency Clinicians. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2023;65(1):58–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2022.10.006].

Patients are not expecting to hear bad news

No existing long-term relationships exist between the patient and emergency clinicians

Prognostic uncertainty exists in the new diagnosis or new changes in illness trajectories presenting in the ED (eg, patients may require additional tests).

To overcome these barriers, best practices exist to deliver this bad news.31,32 The essential elements of delivering bad news for emergency clinicians and why they are essential are shown in Table 1. These steps would allow emergency clinicians to deliver the bad news in a patient-centered approach to facilitate patients’ understanding of the situation. More importantly, these steps allow emergency clinicians to build a therapeutic alliance with the patients (eg, explicitly let patients know that emergency clinicians are committed to delivering the best care possible along with the patients).

Table 1.

The essential elements of delivering bad news for emergency physicians

| Steps | Examples | Why Important? |

|---|---|---|

| Set up | Sit down, private settings, avoid interruptions, involve loved ones | Small steps can maximize the delivery of the bad news in the most patient-centered approach. |

| Perception | Ask what they heard already: “What have you heard about todays’ test?” | Understanding patient’s perceptions and expectations can allow emergency physicians to anticipate the prognostic awareness. |

| Invitation | Obtain permission to talk about the news: “Would it be ok if I share bad news?” |

When patients are asked for permission, they perceive a sense of control in uncontrollable situations in the ED. |

| Knowledge | Disclose the news clearly: “The CT scan showed blood clots and a new cancer in the liver – I am worried that the cancer is getting worse.” |

Avoid jargon like pulmonary embolism, metastatic disease, etc. Clear headlines: short messages and their overall implications for the patient |

| Emotion | Respond to patient’s emotional response: “This is disappointing and overwhelming.” |

Without acknowledging and empathizing with patients’ emotions, patients cannot process the information being communicated. |

| Summary | Summarize and discuss next steps: “The key things that I want you to know are” |

Next steps after |

Data from Kei Ouchi, MD.

Discussing Treatment Goals Based on the Patient’s Values and Preferences

As in Box 2, an example of a case continues. Emergency clinicians inherently understand the importance of exploring patients’ values and preferences for end-of-life care. The key time window to ask about these values and preferences is while patients are relatively clinically stable.33 However, when the patients are critically ill, it is often difficult to take the time to explore patients’ values and preferences due to a lack of time.34 Therefore, we have explained exactly how to do this in clinically unstable patients.35 The highlight of how to ask about patients’ values and preferences and how these values and preferences should be applied to our clinical recommendations for care, as shown in Table 2. Experts in palliative care recommend asking patients with serious illnesses about their baseline function and their values/preferences for end-of-life care. Many of these questions have been tested rigorously in patients and validation during clinical trials.

Box 2. An example of a continuing case that highlights the discussing treatment goals based on patient’s value and preferences for emergency clinicians.

Case continue

After delivering the bad news, the emergency physician placed the inpatient bed request. When handing off the patient care to the inpatient team, the inpatient clinician asked, “What the goals of care for this patient?” Knowing that no emergent decisions are necessary for this patient, the emergency physician decided to start exploring this patient’s goals of care while he is clinically stable.

Data from Kei Ouchi, MD.

Table 2.

The clinical recommendations on applied approaches to asking patients’ values and preferences for emergency clinicians

| Step | How to Ask |

|---|---|

| Baseline function | To decide which treatments might help [his] the most, I need to know more about [his]: What type of activities was [he] doing day to day before this illness? |

| Values Use question(s) as appropriate |

• Has [he] expressed wishes about the type of medical care [he] would or wouldn’t want? • How might [he] feel if treatments today led to: Inability to return to [his] favorite activities? Inability to care for [himself] as much as [he] does? • What abilities are so crucial that [he] wouldn’t consider life worth living if [he] lost them? • How much would [he] be willing to go through for the possibility of more time? • Are there states [he] would consider worse than dying? |

Data from Kei Ouchi, MD.

Applying Patients’ Stated Values/Preferences for End-of-Life Care to Make Clinical Recommendations

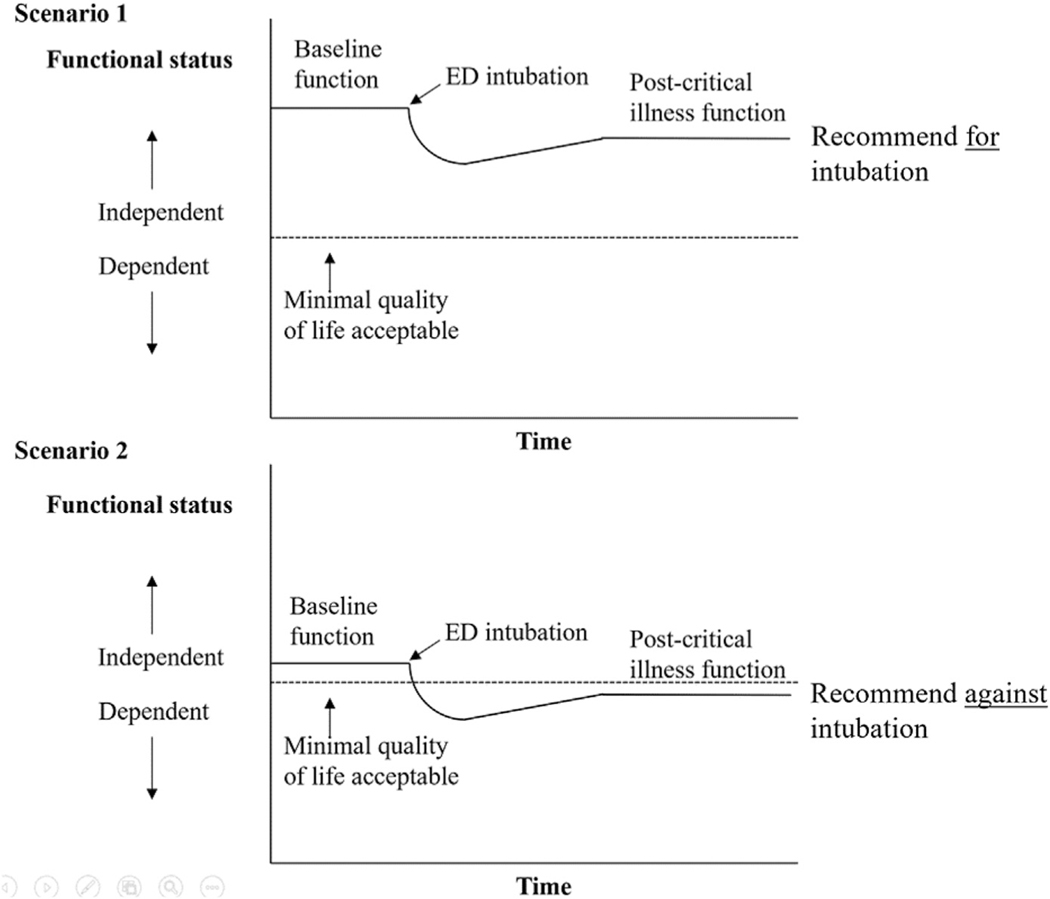

To make an empathic and goal-concordant recommendation for end-of-life care, it is critically important to integrate patients’ values and preferences, clinical information, and baseline physical function. Ask yourself, “In the best-case scenario, would this patient be able to achieve the minimal quality of life worth living for [him] after intubation/ICU stay?” If this answer is a clear “no” or likely outcome would be considered “worse than death” for the patient, emergency clinicians can confidently make a recommendation to focus the treatment on the patient’s comfort. If the answer is unclear (eg, the surrogate may not know the minimal quality of life that the patient would consider acceptable to live) or likely outcome would be an acceptable quality of life worth living for, emergency clinicians can make a recommendation to focus the treatment on recovering from the illness (Fig. 2). Emphasize what you will do (eg, focus on ensuring the patient’s comfort). Consider explaining why you would not recommend certain therapies in the context of the baseline function and values. The introduction of a time-limited trial may also be helpful.36,37

Fig. 2.

Recommendation based on quality of life acceptable to patients. (Adapted from Ouchi K, Lawton AJ, Bowman J, Bernacki R, George N. Managing Code Status Conversations for Seriously Ill Older Adults in Respiratory Failure. Ann Emerg Med. 2020 12; 76(6):751–756. PMID: 32747084; PMCID: PMC8219473.)

SUFFERING IN THE LAST DAYS OF LIFE

Patients at the end of life often experience new or worsen physical and/or psychosocial suffering that may result in their presenting to the ED. The emergency clinicians are able to rapidly assess for suffering, simultaneously work up potential reversible etiologies, initiate evidence-based treatment, and, when indicated, seek expert support from subspecialty teams like palliative care. The 2 most common symptoms are pain and dyspnea, which have more detailed guidance in the subsequent sections. The additional symptoms that frequently cause suffering at the end of life (nausea/vomiting, constipation, depression, anxiety, and delirium) are included in Table 3 for brief guidance on assessment and management.

Table 3.

Initial pharmacologic management for symptoms in end-of-life emergency department patients

| Medication | Detail |

|---|---|

| Nausea and vomiting | |

| Ondansetron (serotonin-receptor antagonist) | 4–8 mg PO/IV every 8 h. Common “first-line” antiemetic that is generally well tolerated. Also preferred in patients with Parkinson’s, Lewy body dementia, or restless leg syndrome as it does not affect dopamine. Constipation is a common side effect. |

| Metoclopramide and prochlorperazine (dopamine-2-receptor antagonists) | 5–10 mg PO/IV every 8 h. Older antiemetics that are still often used for nausea as well as headache. Metoclopramide has a promotility component, so it can be helpful in gastric emptying disorders or constipation, but should be avoided in bowel obstructions. Avoid in patients with Parkinson’s, Lewy body dementia, or restless leg syndrome. Acute motor symptoms like dystonic reactions are possible. |

| Olanzapine (dopamine-2-receptor antagonist) | 2.5–5 mg PO/IV every 6–8 h. A newer dopamine antagonist. Generally, well tolerated. Also useful in treating delirium, anxiety, insomnia, and cachexia. |

| Steroids, anti-histamines, antihistamines and anticholinergics, cannabinoids, etc. | Generally, avoid in the ED unless recommended by a specialist. |

| Nonpharmacologic | Ginger and mint products can be helpful, as can sniffing isopropyl alcohol swabs. |

| Constipation | |

| Sennosides | 1–2 tabs (8.6–17.2 mg) once or twice daily. Intestinal stimulant. |

| Polyethylene glycol | 1–2 tablespoons (17–34 g) once or twice daily. Intestinal stimulant. |

| Docusate | Generally, not helpful as monotherapy. Stool softener. Sometimes used in conjunction with a promotility agent like sennosides. |

| Bisacodyl enema | Generally dosed once daily. Intestinal stimulant. |

| Warm tap water and milk of molasses enemas | Can be given up to every 2 h. Work by causing rectal distention and reflex defecation. |

| Depression and anxiety | |

| SSRIs, SNRIs, TCAs | Traditional mainstay of depression pharmacotherapy. Generally peak effect takes weeks. Not typically started in the ED. However, may be recommended by palliative and/or psychiatry specialists who see your patients. |

| Mirtazapine | Sometimes used for depression, and also can be helpful for insomnia, nausea, or anorexia. Peak effect shorter than SSRIs, SNRIs, and TCAs, but still not typically started in ED. |

| Methylphenidate or dextroamphetamine | Stimulants are used to treat depression in patients at the end of life with short (<4 wk) prognosis. Rapid onset. Talk to your palliative and/or psychiatry specialists for guidance. |

| Olanzapine (dopamine-2-receptor antagonist) | 2.5–5 mg PO/IV every 6–8 h. Newer dopamine antagonist. Generally, well tolerated. Also useful in treating delirium, nausea/vomiting, insomnia, and cachexia. |

| Lorazepam (GABA receptor antagonist) | 0.5–1 mg PO/IV every 6–8 h. Rapid onset for relief of anxiety in the ED, but can be deliriogenic. Would generally not prescribe for use at home unless recommended by a palliative care or psychiatry specialist. Higher doses are often needed at end of life. |

|

Delirium Remember that the first step in treating delirium should be identifying and treating reversible causes. The following are medications that can help improve patients’ symptoms and safety. | |

| Haloperidol | 0.5–1 mg PO/IV/IM, titrating by 2–5 mg every 1 h until effective dose is found. Recommended daily max 100 mg. |

| Olanzapine | 2.5–5 mg PO/IV every 6–8 h. A newer dopamine antagonist. Generally, well tolerated. Also useful in treating, nausea/vomiting, anxiety, insomnia, and cachexia. |

| Quetiapine | 25–50 mg PO once or twice daily. Agent of choice in delirious patients with Parkinson’s disease or Lewy body dementia who can take PO. |

| Thorazine | 25–50 mg PO/IV, titration by 25–50 mg every 1 h until effective dose is found. Recommended daily max 2000 mg. |

| Lorazepam | Generally avoided as they can worsen delirium, though in delirious patients with Parkinson’s disease or Lewy body dementia who can’t take PO they’re sometimes used. Patients with “terminal delirium” can consider combining them with another medication like haloperidol. In this case, start with 0.5–1 mg IV/IM, titrating by 1–2 mg every 1 h until effective dose is found. |

Abbreviations: ED, emergency department; IV, intravenous; IM, intramuscular; PO, per oral; SNRIs, serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors; SQ, subcutaneous; SSRIs, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors; TCAs, tricyclic antidepressants.

Data from Jason Bowman, MD.

Nausea and/or vomiting occur in many patients nearing or at the end of life, with reported prevalence ranging from 16% to 68% depending on disease process.38 Some common reasons for nausea and vomiting include advanced disease, medication effect, infection, bowel obstruction, constipation, intracranial processes, metabolic derangements, or psychosocial distress.39 In addition to the direct suffering, unmitigated nausea/vomiting can also impact patients’ ability to take other oral medications and intake for hydration, sustenance, or pleasure.

Constipation is reported by up to 90% of seriously ill patients and can significantly impact their quality of life.40 The cause is often multifactorial. When assessing constipation, it is important to inquire about patients’ baseline bowel function. Although textbooks suggest a “normal” bowel movement every 1 to 2 days, the reality is that many patients have their own comfortable baseline prior to or earlier in their serious illness. The patients produce stool even if they have little or no oral intake, as an estimated 50% of stool is made up of bowel shedding and other body waste.

Seriously ill patients frequently report depression and/or anxiety as they near the end of life, with published rates for each around 25% to 50%.41 Although emergency clinicians likely are not initiating or adjusting long-acting medications for these symptoms or providing nonpharmacologic treatment, they can still be the first to explore what the patients are actually experiencing as well as the potential exacerbating triggers (eg, unmitigated physical symptoms, caregivers/social/spiritual distress).

Emergency clinicians frequently encounter patients with delirium, but rates of both hyper- and hypoactive delirium are up to 88% in patients nearing the end of life.42 Screening can be done using a standardized tool such as the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM). As in all cases of delirium, emergency clinicians should first attempt to identify reversible causes such as pain or other unmitigated symptoms, sleep–wake disruption, and infection.

PALLIATING PAIN MANAGEMENT

Pain is the most common reason for adult patients to present to an ED and is particularly common in patients presenting near or at the end of life. Pain is a complex phenomenon, experienced differently by each patient, and made up of physical, psychological, social, and spiritual components. Commonly used classifications of mechanical/physical pain are (1) nociceptive (such as pressure from a growing tumor), inflammatory (such as from a burn or other traumatic injury), (3) neuropathic (such as in diabetic neuropathy or nerve impingement from tumor or trauma), (4) visceral (such as in Gastrointestinal malignancies, infectious colitis). Psychological, social, and/or spiritual suffering can exacerbate physical pain, or directly cause the perception of pain themselves.43

Emergency clinicians can begin a focused assessment of pain in the ED using a tool like OPQRST (Table 4) and also ask patients exactly how they have been taking those medications and what effects or adverse effects they have noticed.44 The emergency clinician should rapidly conduct any indicated work-up for the pain while simultaneously initiating multimodal treatment. Some common options for ED management of pain are described in Table 5.45,46 In addition to traditional options such as oral, topical, intravenous, intramuscular medications, local injections, and nerve blocks are now increasingly performed in the ED. Emergency clinicians can also find support in managing challenging pain from a variety of subspecialty colleagues, including palliative care, acute or chronic pain teams, physical therapy, psychiatry/social work, and even potential surgical options to improve comfort and quality of life, if they are within the patient’s goals of care.46

Table 4.

The focused emergency department assessment of pain can begin using a tool like OPQRST

| OPQRST Tool | Detail |

|---|---|

| 1. Onset | What were they doing when it started and how did it start |

| 2. Provocation/palliation | What makes it better or worse |

| 3. Quality | How would they describe (eg, cramping, stabbing, burning, electric shock, pressure) |

| 4. Region/radiation | Where do they feel it and does it move elsewhere |

| 5. Severity | On a scale of 1–10, or mild/moderate/severe |

| 6. Time | When did the pain start and is it constant or intermittent. If the patient has chronic pain, it is also important to assess if their current pain is similar or different to their chronic pain and, if the latter then how it is different. |

Data from [Friese G. How to use OPQRST as an effective patient assessment tool. EMS1 Online. 2020. Available at: https://www.ems1.com/ems-products/education/articles/how-to-use-opqrst-as-an-effective-patient-assessment-tool-yd2KWgJIBdtd7D5T/. Accessed Jan 2023.]

Table 5.

Initial pharmacologic management of pain in seriously ill or end-of-life emergency department patients

| Medication | Details |

|---|---|

| First-line agents to consider | |

| Acetaminophen/Tylenol | Excellent, often underutilized and underdosed agent, especially in combination with an NSAID. Consider 650–975 mg PO or IV every 6–8 h. Daily max ranges from 4 g (young and healthy) to 2 g (elderly with underlying liver disease). |

| Motrin/Advin/ibuprofen, Aleeve/naproxen, Toradol/ketorolac, etc. | Particularly helpful for inflammatory pain. Available in IV/IM/PO forms. Generally, well tolerated at evidence-based doses (example of Ibuprofen 400–600 mg every 6 h, rather than 800 mg as it is not any more effective but has more side effects). Must weigh risk/benefit in each patient (advanced age, systemic anticoagulation, renal disease, etc.), though one-time dosing in ED is generally lower risk than chronic use. |

| Topical Voltaren/diclofenac (NSAID) gel, lidocaine patches/cream, and other topical agents | Generally, well tolerated and easy to use. Topical NSAID gel can be very helpful for inflammatory pain (musculoskeletal, superficial tumor like posterior spinal metastases, etc.) and systemic absorption is minimal. |

| Local injections and nerve blocks | Increasingly used in ED patients for a variety of indications with great effect. When done properly, generally very safe and well tolerated. Some examples include trigger point injections for muscle spasm, local injection for dental pain, fascia iliaca blocks for hip fracture, intercostal nerve blocks for rib fracture, etc. |

| Opioids | |

| Short-acting | Numerous PO/IV/SQ agents including morphine, hydromorphone, oxycodone, hydrocodone, oxycodone, fentanyl, etc. Can convert between them using an opiate equianalgesic dosing chart or calculator. Typically start with the patient’s home dose (or equivalent), or in opioid naive patients a dose based on their age/weight/hepato-renal function. Oral medications’ peak effect is ~ 45 min, IV morphine and hydromorphone have peaks ~ 20 min, and IV fentanyl is ~ 2 min. If effective relief of pain can continue current dose every 2–3 h, adjust as needed. If partial response, repeat initial dose. If no response to initial dose, increase by 50%–100% and give immediately (eg, morphine 4 mg IV → 6 or 8 mg). |

| Long-acting | Numerous PO and SQ options including long-acting morphine, hydromorphone, oxycodone, fentanyl, methadone, suboxone, etc. An IV opioid infusion (“drip”) is another form of “long-acting” or “basal” analgesia. ED clinicians should not start these agents without guidance from a subspecialist (palliative care, etc.) but for patients already on one of them it is important to continue basal opioid analgesia while they are in the ED (either their home agent and dose or something equivalent) in addition to using short-acting medications. Of note, it can be helpful to think of opioid-dependent patients like patients who are insulin-dependent. In both cases, the long-acting agent (opioid or insulin) can be reduced if indicated (hypoglycemia or delirium respectively, for example) but generally should NOT be stopped entirely. Involve subspecialty consultants early-on in both cases if concerned. |

| Opioid infusions (“drips”) | Historically usually initiated in the ED for patients at the end of life. However, in many cases an opioid infusion is not necessary and intermittent boluses of short-acting opioids can adequately manage the patient’s symptoms. In patients no longer able to take their PO long-acting opioids, an equivalently dosed opioid infusion can be started in their place. For patients nearing or at the end of life who require frequent boluses of short-acting opioids over a span of several hours, adding on an opioid infusion can be helpful. Atypical starting dose would be the total bolus/PRN needs, divided by the number of hours gone by, multiplied by ½ (eg, if morphine 16 mg IV (4 mg x 4) was needed in PRNs over 4 h, start the infusion at 16 mg/4 h x ½ = 2 mg/h). Worsening pain should be treated with boluses of short-acting opioids (not reflexively increasing the infusion), and the infusion rate adjusted every few hours based on the patient’s needs. (Any changes to the infusion rate require several half-lives to take effect.) |

| Other adjuvants | |

| Ketamine | Typical ED starting dose for pain is 0.1–0.3 mg/kg IV. Infusing over 10–15 min instead of rapid push can reduce side effects. Continuous infusions of 0.15–0.2 mg/kg/h can also be used for analgesia, though this is less common in the ED. Ketamine be used independently or as an opioid adjuvant. |

| Other neuropathic agents | Gabapentin, pregabalin, SSRIs, SNRIs, etc. Not started in the ED but, if able, important to continue in patients already on them. |

| Medications to avoid | |

| Codeine and Tramadol | Older opioids, previously marketed as “gentle opioids” or [falsely] as “opioid alternatives”. They both have variable and unpredictable metabolism as well as high risk of side effects and potentially life-threatening complications. Tramadol in particular has been linked to increased risk of delirium, seizures, refractory hypoglycemia, and death. |

| Combination drugs (such as Percocet or Vicodin) | Typically, an opioid combined with low (below recommended) dose acetaminophen. However, patients can combine this with OTC acetaminophen and inadvertently overdose. Better to prescribe optimally dose acetaminophen and (if needed) also an opioid. |

Abbreviations: ED, emergency department; IM, intramuscular; IV, intravenous; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; PO, per oral; PRN, pro re nata; SNRIs, serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors; SQ, subcutaneous; SSRIs, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.

Data from Jason Bowman, MD.

PALLIATING DYSPNEA MANAGEMENT

Dyspnea is defined as a subjective sensation of an inability to breathe comfortably, which becomes more prevalent and intense in the last weeks of the patient’s life.47–49 Dyspnea crises can occur and require visits to the ED when acute worsening of dyspnea is experienced with heightened psychosocial-spiritual needs and unprepared caregivers who are overwhelmed to respond.50 Dyspnea response requires comprehensive, patient-centered assessment and treatment involving coordinating interdisciplinary care teams.50,51 The step-by-step list describes how emergency clinicians are able to provide quality palliative care for seriously ill patient with dyspnea in the ED (Table 6).47–52 A recommended stepwise approach to dyspnea begins with determining potentially reversible causes, followed by using nonpharmacologic (Table 7), and then pharmacologic interventions (Table 8) to palliate the suffering of dyspnea. The key to care coordination is communication skills in anticipatory planning, not only with the family regarding goals, concerns, and expected outcomes but also with the health care team. Additionally, a checklist and important step approaches for care could be helpful for ED providers. However, dyspnea can be successfully treated by incorporating an interdisciplinary, multimodal plan, including preparation to anticipate dyspnea before its onset, which can assist in early management and avoid a crisis event.

Table 6.

The step-by-step list describes how emergency clinicians are able to provide quality care for palliative dyspnea management

| Detail | |

|---|---|

| 1. The systematic screening can | Facilitated early detection and timely intervention. |

| 2. The measurement for patients’ distress and discomfort related to dyspnea | • The 0–10 numeric rating scale to the intensity of dyspnea is the most valid, reliable, and widely used measurement for patients’ subjective distress and discomfort. • The behavioral approach observed for respiratory distress signs is an option for such a crisis, terminal dyspnea, or patients unable to communicate. The Respiratory Distress Observation Scale (RDOS) consists of 8 variables that are possible to use in the ED but require more studies. • Whenever possible, a comprehensive assessment should be done to determine the severity of dyspnea, potential causes, concomitant symptoms, functional and emotional impacts. • An assessment of family caregiver coping, needs, care participation, and home resources will support and incorporate them into the health care team. Psychoeducational interventions should be provided to caregivers. |

| 3. The treatment for reversible causes and disease-modifying treatments (eg, diuretics, corticosteroids) | Optimized and aligned with patient preferences, goals of care, prognosis, and overall health status. The time-limited trial interventions might be particularly helpful for patients who have uncertain goals of care prior to intubation. |

| 4. A recommended stepwise approach to palliate the suffering of dyspnea | 1. Begins with determining potentially reversible causes 2. Using nonpharmacologic (see Table 7) 3. Pharmacologic interventions (see Table 8) |

| 5. The referral of patients with refractory dyspnea, despite receiving appropriate treatments, to a palliative care specialist | Along with treating the patient’s suffering, the goals of care discussion can be facilitated to the patient and their families. |

| 6. Reassessment and adjustment of interventions | Used the same assessment tool for adjustment of dyspnea palliation until the patient’s suffering from dyspnea was relieved. |

Data from [Weissman DE. Dyspnea at End-of-Life. Palliative Care Network of Wisconsin. 2015. Available at: www.mypcnow.org/fast-fact/dyspnea-at-end-of-life/. Accessed March 2023.] [Ahmed A, Graber MA. Approach to the adult with dyspnea in the emergency department. UpToDate 2022. Available at: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/approach-to-the-adult-with-dyspnea-in-the-emergency-department. Accessed March 2023.] [Hui D, Bohlke K, Bao T, et al. Management of Dyspnea in Advanced Cancer: ASCO Guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(12):1389–1411. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.20.03465] [Mularski RA, Reinke LF, Carrieri-Kohlman V, et al. An official American Thoracic Society workshop report: assessment and palliative management of dyspnea crisis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2013;10(5):S98-S106. https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201306-169ST] [Quest TE, Lamba S. Palliative for adults in the ED: Concepts, presenting complaints, and symptom management. UpToDate 2022. Available at: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/palliative-care-for-adults-in-the-ed-concepts-presenting-complaints-and-symptom-management. Accessed March 2023.]

Table 7.

Nonpharmacologic intervention for palliative dyspnea management in the emergency department

| Nonpharmacologic Intervention | Detail |

|---|---|

| Airflow interventions | A fan blowing air toward the patient’s face (trigeminal nerve distribution). |

| Supplemental oxygen | Standard therapy for patients with symptomatic acute hypoxemia on room air (SpO2 ≤ 90%). In other scenarios, a therapeutic trial may be based on symptom relief, which could be helpful in terms of airflow. |

| Nasal cannula | Patients generally prefer nasal cannula administration to a mask, as is commonly seen in the agitation of imminently dying patients due to the mask. Standard supplemental oxygen is typically delivered through a nasal cannula at 2–6 LPM. |

| High-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) | • Alleviating dyspnea by increasing oxygenation, improving ventilation with nasopharyngeal washout, stimulation of the trigeminal nerves, augmentation of positive airway pressure, reduction of work of breathing, and heating and humidifying of the inhaled gas • Offered when the patient has severe hypoxemia and the goal is concordant. HFNC could also be used as a time-limited therapeutic trial intervention. • Set the temperature 34°C to 37°C. The flow rate usually starts at 45–50 LPM but may decrease to 20 LPM or increase gradually up to 80 LPM of heated and humidified oxygen, depending on the patient’s comfort. |

| Noninvasive ventilation (NIV) | • Alleviating dyspnea by increased oxygenation, improved ventilation by providing positive end-expiratory pressure, and augmenting respiratory muscles. • More likely to be beneficial for patients with hypercapnic respiratory failure and concordant goals. NIV could also be used as a time-limited therapeutic trial intervention. • The contraindications include facial trauma, a reduced level of consciousness, severe vomiting, the inability to clear secretions, and severe claustrophobia. • The potential adverse events include skin breakdown, muffled communication, claustrophobia, and the inability to eat. Approximately 7% of patients have discontinued due to intolerance. |

| Positioning | • The head and chest are elevated while in the sitting position, possibly with arms elevated on pillows or a bedside table. • A side-lying position with the “good” lung up or down is helpful for increasing perfusion and/or ventilation. |

| Bedside breathing exercises | • Abdominal breathing: when inhaling, focus on filling the lungs completely and feel the stomach move outward away. While exhaling, feel the stomach fall slowly and the lungs empty. • Pursed-lip breathing: exhale from the mouth as twice long as inhale. Breathe in through the nose (eg, count 1–2). Pucker the lips and breathe out slowly through the mouth (eg, count 1–2-3–4). |

| Bedside relaxation techniques | Mindfulness, meditation, guided imagery, and distraction strategies (eg, music, pictures, reading by oneself or a caregiver) |

| Discontinuing parenteral fluids | In the imminently dying patients |

Abbreviations: ED, emergency department; LPM, liter per minutes; SpO2, peripheral capillary oxygen saturation.

Data from [Weissman DE. Dyspnea at End-of-Life. Palliative Care Network of Wisconsin. 2015. Available at: www.mypcnow.org/fast-fact/dyspnea-at-end-of-life/. Accessed March 2023.] [Ahmed A, Graber MA. Approach to the adult with dyspnea in the emergency department. UpToDate 2022. Available at: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/approach-to-the-adult-with-dyspnea-in-the-emergency-department. Accessed March 2023.] [Hui D, Bohlke K, Bao T, et al. Management of Dyspnea in Advanced Cancer: ASCO Guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(12):1389–1411. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.20.03465] [Mularski RA, Reinke LF, Carrieri-Kohlman V, et al. An official American Thoracic Society workshop report: assessment and palliative management of dyspnea crisis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2013;10(5):S98-S106. https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201306-169ST] [Quest TE, Lamba S. Palliative for adults in the ED: Concepts, presenting complaints, and symptom management. UpToDate 2022. Available at: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/palliative-care-for-adults-in-the-ed-concepts-presenting-complaints-and-symptom-management. Accessed March 2023.]

Table 8.

Pharmacologic intervention for palliative dyspnea management in the emergency department

| Medication | Detail |

| The recommended medication for dyspnea palliation | |

| Systemic opioid | • The primary medication for palliating refractory dyspnea and dyspnea at the end of life, offered when nonpharmacologic interventions are insufficient to relieve the dyspnea • Administered orally, intravenously (IV), subcutaneously, transmurally, and rectally • Monitoring for sedation and confusion. • The doses for acute dyspnea exacerbations are 50% lower than those treating acute pain. • The opioid titration protocol is “low and slow” IV titration of an immediate-release opioid, until the patient reports or displays relief. • The widely studies and recommendations demonstrate significant reductions in dyspnea with the opioid titration protocol administration without evidence of decreased oxygen saturation or respiratory depression. |

| Opioid for naive patient | Initial parenteral morphine is 2–5 mg or equivalent, 15–30 min for redosing intervals. Initial oral morphine is 5–15 mg and 60 min for redosing intervals. |

| Opioid for opioid tolerant patient | A breakthrough dose equivalent to 10%–20% of the previous 24-h opioid dose use (morphine equivalent daily dose: MEDD). |

| Hydromorphone | Initial IV/subcutaneous dose of 0.2 mg every 5–10 min |

| Oxycodone | Initial 5 mg orally every 1 h |

| Benzodiazepine | • The adjunctive addition to the opioid regimen, offered to the patients with anxiety or distress related to dyspnea despite intervention trials • Short-acting benzodiazepines such as midazolam, 2–5 mg every 4 h, may be helpful. In other scenarios, the risk of respiratory depression may further increase due to the benzodiazepines’ adverse effects. |

| Anticholinergic therapy to dry the death rattle (secretions at the end of life) | |

| Glycopyrrolate | Initial 0.2 mg intravenous bolus every 4–6 h or continuous intravenous/subcutaneous 0.6–1.2 mg/d |

| Hyoscine BUTYLbromide | Initial 20 mg intravenous bolus every 4–6 h or continuous intravenous/subcutaneous 20–60 mg/d |

| Hyoscine HYDRObromide | Initial 0.4 mg IV bolus every 4–8 h or continuous intravenous/subcutaneous 1.2–1.6 mg/d. Risk for delirium and agitation |

Abbreviations: ED, emergency department; MEDD, morphine equivalent daily dose.

Data from [Weissman DE. Dyspnea at End-of-Life. Palliative Care Network of Wisconsin. 2015. Available at: www.mypcnow.org/fast-fact/dyspnea-at-end-of-life/. Accessed March 2023.] [Ahmed A, Graber MA. Approach to the adult with dyspnea in the emergency department. UpToDate 2022. Available at: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/approach-to-the-adult-with-dyspnea-in-the-emergency-department. Accessed March 2023.] [Hui D, Bohlke K, Bao T, et al. Management of Dyspnea in Advanced Cancer: ASCO Guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(12):1389–1411. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.20.03465] [Mularski RA, Reinke LF, Carrieri-Kohlman V, et al. An official American Thoracic Society workshop report: assessment and palliative management of dyspnea crisis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2013;10(5):S98-S106. https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201306-169ST] [Quest TE, Lamba S. Palliative for adults in the ED: Concepts, presenting complaints, and symptom management. UpToDate 2022. Available at: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/palliative-care-for-adults-in-the-ed-concepts-presenting-complaints-and-symptom-management. Accessed March 2023.]

CARING FOR HOSPICE PATIENTS

Hospice provides palliative care to patients at the end of life with an estimated life expectancy of 6 months or less.53 When a patient presents with worsening symptoms in the ED, emergency clinicians can prognosticate their life expectancy and offer hospice care suggestions to these patients and their caregivers. On the other hand, the patients receiving hospice care were also reported to have visited the ED. The reasons are primarily related to patient or caregiver factors or hospice care service factors, including inadequate symptom relief,4,54,55 malfunctioning medical equipment, stress, fear, and difficulty coping with a dying loved one, conflicts regarding the continuation and termination of life-sustaining treatment, conflicts of wills and ideas between the caregiver and patient, caregiver fatigue, and past painful experiences.56 The important concerns to be addressed in the ED visits are described in Box 3.

Box 3. The important information to be addressed in emergency department visits of the patients from the hospice care.

The information to be addressed in ED visits of the patients from the hospice care

Identify hospice care staff.

Identify the trigger for the ED visit.

Relieve symptoms of distress.

- When a medical condition is critical, quick decisions need to be made while providing life-sustaining treatment.

- Identify the legal decision-maker and confirm the contents of the advance directive.

- Discuss goals of a care promptly.

- Provide recommendations.

- If the patient is already dying, consider cultural/spiritual requests.

- Diagnostic testing

- Should be somewhat limited and withheld until discussed with hospice care personnel.

- Testing should be based on goals of care tailored to the patient’s situation.

- Generally, the first step is to perform a less painful and less invasive procedure for the purpose of clarifying a reversible condition or prognosis.

- Treatment

- Engage in treatment based on goals of care tailored to the patient’s situation.

- Determine the disposition.

- Discuss with hospice care services personnel to develop a plan that meets the patient’s goals of care.

- It may be better to return them home or admit them to an inpatient hospice facility rather than admit them to a hospital.

- If the patient wants to stay home and is having difficulty relieving symptoms, assistance from 24 hour hospice care services may be coordinated.

- If hospitalization is required, referral for inpatient hospice care services.

Data from [DeSandra PL, Quest, TE. Palliative Aspects of Emergency Care, First Edition. Oxford University Press; 2013.]

QUALITY METRICS FOR PALLIATIVE CARE IN THE EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines quality palliative care as quality-of-life care, that is effective, safe, person-centered, timely, equitable, integrated, and efficient.57 The WHO action keys at the point-of-care level, including the ED, are (1) maintaining and improving the quality of palliative care, (2) collecting and using data to drive improvement efforts, and (3) integrating quality improvement methods into usual practice in the ED.

In 2017, the Palliative Medicine Section of the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) developed a committee to establish consensus on the best practices for providing palliative care in the ED, including metrics and quality measurement in 3 main domains (Table 9).58

Table 9.

The quality metrics that can be widely applied at the emergency department

| Patient Identification and Assessment for Palliative Care Needs | Management of Palliative Care in ED | Transitions of Care |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical outcomes | ||

| • Percentage of ED patients screened positive for palliative care eligibility (total and by using each screening tool) 1. Surprise question: not surprised if the patient died during this admission 2. Clinical indicators for example, frequent admission with the same problem 3. Specific disease indicators • Percentage of patients with X diagnosis who were screened positive for palliative care eligibility • Percentage of documented screening for palliative care eligibility in the target population (eg, X diagnosis, transfer from the long-term care facility) • Percentage of patients measured for psychospiritual social needs • Percentage of family members screened for caregiver strain |

• Percentage of patients with overall/each distressing symptom assessment documented • Time from symptom assessment to delivery of medication for symptom relief • Percentage of patients prescribed distressing symptom control medications in ED • Percentage of documented health proxy or decision maker in medical records in target population • Percentage of patients with do not attempt resuscitation status in target population • Percentage with documentation of advance directives/POLST/MOLST in target population • Percentage of patients who died within 24/48/72 h of ED admission with documented health proxy or decision maker in medical record |

• Percentage of X intervention after ED palliative care consultation • Percentage of deaths in the ICU and/or ED after ED palliative care consultation • Percentage of repeat ED visits (and/or readmission to the hospital) within 30 d • Percentage discharged to home after ED palliative care consultation • Percentage discharged to hospice care after ED palliative care consultation |

| Operational process | ||

| • Time from ED arrival to completion of palliative care screening • Percentage of personnel who completing the screening tool • Percentage of patients transfer from the long-term care facility • Percentage of patients who screened positive for palliative care eligibility and multiple ED visits (or hospitalizations) in X time |

• Percentage of X order sets placed by an ED clinician in target population • Percentage of palliative care order sets used in target population • Percentage of order sets used in ED patients with X condition • Percentage of intensive care in ED (and/or in this admission) in target population (eg, ventilator use, pressor support) |

• Percentage of ED referrals for palliative care consultation/hospice care • Percentage of patients admitted (total, ICU, non-ICU, palliative care unit) after palliative care consultation • Time from consult to response by palliative care team or hospice staff • ED length of stay for patients with palliative care consult (and/or in target population) vs ED length of stay for all patients, all discharged patients, all admitted patients • Hospital length of stay for patients with ED palliative care consultations (and/or in target population) • Percentage of canceled palliative care consultations by admitting clinician • Time from ED request for palliative care/hospice consultation to final disposition |

| Patient and/or family member satisfaction | ||

| • Satisfaction scores on patients who screened positive for palliative care eligibility | • Percentage of patients and/or family members reporting a high level of shared decision making with ED clinicians (eg, ED clinicians listen carefully, explain things in a way that was easy to understand) • Percentage of patients and/or family members reporting high level of satisfaction in end-of-life care for an ED patient death • Percentage of patients and/or family members highly satisfied with pain or symptom management in the ED |

• Percentage of patients and/or family members reporting high level of satisfaction with health care team communication • Percentage of patients and/or family members reporting high level of satisfaction in end-of-life care after palliative care consultation in the ED and a patient’s hospital death • Percentage of patients and/or family members reporting excellent coordination of care to the next health care setting from the ED |

Abbreviations: ED, emergency department; ICU, intensive care unit; MOLST/POLST, medical/physician’s/practitioner’s orders for life-sustaining treatment.

Data from [Goett R, Isaacs ED, Chan GK, et al. Quality measures for palliative care in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2022;10.1111/acem.14592. https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.14592] [George N, Phillips E, Zaurova M, Song C, Lamba S, Grudzen C. Palliative Care Screening and Assessment in the Emergency Department: A Systematic Review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;51(1):108–19.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.07.017].

Clinical outcome measures focus on assessing the quality of clinical care services provided in the ED for patients with palliative care needs

Operational sustainability measures focus on processes, including patient flow, consultation, disposition, readmissions, and resource utilization

Patient satisfaction measures assess the patients, family members, and caregivers’ perceptions of the quality of care provided in the ED.

A combination of process indicators and outcome indicators is frequently used to measure the quality of palliative care.57 One successful strategy for measures in the ED is to make them actionable, easy to collect, and compatible with existing ED processes and staff roles.58,59 Therefore, Table 9 is a brief list of widely applied and time-based categories that were ranged along the continuum of the patient’s flow in the ED, extending to 72 hours after admission.16,58 The specific patient measurements specified as a target population in Table 9 are valuable to the ED for identifying the population of interest, allocating appropriate institutional resources (eg, the number of palliative care consultations or hospice referrals from the ED), and also providing insightful feedback for an organization’s strategic investment, including financial impact and outcomes (eg, the elderly patients in the ED transferring from long-term care facilities, the number of ventilators used after the palliative care consultation in the ED).58 Moreover, the palliative care educational initiatives for ED providers (eg, the providers’ attitudes or practices after the trainings) are beneficial in improving the quality of ED palliative care.58 Entirely, the metrics should be adjustable for each ED setting depending on local capacity, resources, experience, and the availability of relevant tools.57

KEY POINTS.

Early integration of palliative care at the time of emergency department (ED) visits is important in establishing the comprehensive goals of the entire treatment.

Primary palliative care is the term for the basic palliative care skills that can be provided in any setting of care, including emergency care, thereby improving the quality of care for overall patients.

“Serious illness communication skills” are patient-centered communication skills that foster mutual understanding between seriously ill patients and their clinicians.

CLINICS CARE POINTS.

The ED is crucial for identifying unmet palliative care needs and timely providing palliative care for seriously ill patients who are rapidly declining. Emergency clinicians should not interpret that seriously ill patients, even those in hospice care, visit the ED requesting aggressive life-prolonging treatment.

Although clinicians attempt a frank appraisal of the prognosis, special consideration must be given to how and when this information is communicated to patients.

The patient-centered communication skills that foster mutual understanding between seriously ill patients and their clinicians are known as “serious illness communication skills,” which include “best practices to deliver bad news” and “discussing treatment goals based on the patient’s values and preferences.”

We provided the brief existing guidance on the assessment and management of several suffering symptoms at the end of life that frequently present in the ED.

Moving palliative care screening “upstream” to the ED rather than after hospital admission would reduce medical utilization and cost.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE

Dr Kei Ouchi receives consulting fees from Jolly Good, Inc. (a virtual reality company), which has no relation to this manuscript. Other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.George N, Bowman J, Aaronson E, et al. Past, present, and future of palliative care in emergency medicine in the USA. Acute Med Surg 2020;7(1):e497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith AK, McCarthy E, Weber E, et al. Half of older Americans seen in emergency department in last month of life; most admitted to hospital, and many die there. Health Aff 2012;31(6):1277–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aldridge MD, Epstein AJ, Brody AA, et al. The impact of reported hospice preferred practices on hospital utilization at the end of life. Med Care 2016; 54(7):657–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grudzen CR, Richardson LD, Morrison M, et al. Palliative care needs of seriously ill, older adults presenting to the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med 2010; 17(11):1253–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Samaras N, Chevalley T, Samaras D, et al. Older patients in the emergency department: a review. Ann Emerg Med 2010;56(3):261–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith AK, Fisher J, Schonberg MA, et al. Am I doing the right thing? Provider perspectives on improving palliative care in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med 2009;54(1):86–93, 93 e81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sepulveda C, Marlin A, Yoshida T, et al. Palliative care: the World health organization’s global perspective. J Pain Symptom Manage 2002;24(2):91–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quill TE, Abernethy AP. Generalist plus specialist palliative care–creating a more sustainable model. N Engl J Med 2013;368(13):1173–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cherny NI, Fallon MT, Kaasa S, et al. , editors. Oxford textbook of palliative medicine. 6th edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2021. 10.1093/med/9780198821328.001.0001. Accessed January 12, 2023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weissman DE, Meier DE. Identifying patients in need of a palliative care assessment in the hospital setting: a consensus report from the Center to Advance Palliative Care. J Palliat Med 2011;14(1):17–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carson SS, Cox CE, Wallenstein S, et al. Effect of palliative care-led meetings for families of patients with chronic critical illness: a Randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2016;316(1):51–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schenker Y, Arnold R. The Next Era of palliative care. JAMA 2015;314(15):1565–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glajchen M, Lawson R, Homel P, et al. A rapid two-stage screening protocol for palliative care in the emergency department: a quality improvement initiative. J Pain Symptom Manage 2011;42(5):657–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kirkland SW, Yang EH, Garrido Clua M, et al. Screening tools to identify patients with unmet palliative care needs in the emergency department: a systematic review. Acad Emerg Med 2022;29(10):1229–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.George N, Phillips E, Zaurova M, et al. Palliative care screening and assessment in the emergency department: a systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage 2016;51(1):108–119 e102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang DH, Heidt R. Emergency department admission triggers for palliative consultation may Decrease length of stay and costs. J Palliat Med 2021;24(4):554–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.da Silva Soares D, Nunes CM, Gomes B. Effectiveness of emergency department based palliative care for adults with advanced disease: a systematic review. J Palliat Med 2016;19(6):601–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang DH, Heidt R. Emergency department Embedded palliative care service creates value for health systems. J Palliat Med 2023;26(5):646–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ouchi K, Jambaulikar G, George NR, et al. The “surprise question” asked of emergency physicians may predict 12-month mortality among older emergency department patients. J Palliat Med 2018;21(2):236–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.George N, Barrett N, McPeake L, et al. Content validation of a Novel screening tool to identify emergency department patients with significant palliative care needs. Acad Emerg Med 2015;22(7):823–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Richards CT, Gisondi MA, Chang CH, et al. Palliative care symptom assessment for patients with cancer in the emergency department: validation of the Screen for Palliative and End-of-life care needs in the Emergency Department instrument. J Palliat Med 2011;14(6):757–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tripp D, Janis J, Jarrett B, et al. How well does the surprise question predict 1-year mortality for patients admitted with COPD? J Gen Intern Med 2021;36(9): 2656–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Glick J, Gallo MB, Chelluri J, et al. Utility of the “surprise question” in critically ill emergency department patients. Ann Emerg Med 2018;72:S68. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marshall A, Reuter Q, Powell ES, et al. Emergency department-based palliative interventions. Ann Emerg Med 2017;70:S113–4. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Richardson A, Medina J, Brown V, et al. Patients’ needs assessment in cancer care: a review of assessment tools. Support Care Cancer 2007;15(10):1125–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Homsi J, Walsh D, Rivera N, et al. Symptom evaluation in palliative medicine: patient report vs systematic assessment. Support Care Cancer 2006;14(5):444–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Coalition for Hospice and Palliative Care. Clinical practice guidelines for quality palliative care. 2018. Available at: https://www.nationalcoalitionhpc.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/NCHPC-NCPGuidelines_4thED_web_FINAL.pdf. Accessed November 01, 2019.

- 28.Ma C, Bandukwala S, Burman D, et al. Interconversion of three measures of performance status: an empirical analysis. Eur J Cancer 2010;46(18):3175–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yourman LC, Lee SJ, Schonberg MA, Widera EW, Smith AK. Prognostic indices for older adults: a systematic review. JAMA 2012;307(2):182–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mirza RD, Ren M, Agarwal A, et al. Assessing patient perspectives on receiving bad news: a survey of 1337 patients with life-changing Diagnoses. AJOB Empir Bioeth 2019;10(1):36–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ptacek JT, Eberhardt TL. Breaking bad news. A review of the literature. JAMA 1996;276(6):496–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Back A, Arnold RM, Tulsky JA. Mastering communication with seriously ill patients : balancing honesty with empathy and hope. Cambridge England New York: Cambridge University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ouchi K, George N, Schuur JD, et al. Goals-of-Care Conversations for older adults with serious illness in the emergency department: challenges and opportunities. Ann Emerg Med 2019;74(2):276–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prachanukool T, Aaronson EL, Lakin JR, et al. Communication training and Code status conversation patterns reported by emergency clinicians. J Pain Symptom Manage 2023;65(1):58–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ouchi K, Lawton AJ, Bowman J, et al. Managing Code status Conversations for seriously ill older adults in Respiratory failure. Ann Emerg Med 2020;76(6):751–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Quill TE, Holloway R. Time-limited trials near the end of life. JAMA 2011;306(13):1483–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scherer JS, Holley JL. The role of time-limited trials in Dialysis decision making in critically ill patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2016;11(2):344–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Glare P, Miller J, Nikolova T, et al. Treating nausea and vomiting in palliative care: a review. Clin Interv Aging 2011;6:243–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kamell A, Marks S, Hallenbeck J. Nausea and Vomiting: Common Etiologies and Management. Fast Facts - Palliative Care Network of Wisconsin Sept 2021. Accessed Jan 2023.

- 40.Dzierzanowski T, Larkin P. Proposed criteria for constipation in palliative care patients. A multicenter cohort study. J Clin Med 2020;10(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mossman B, Perry LM, Walsh LE, et al. Anxiety, depression, and end-of-life care utilization in adults with metastatic cancer. Psycho Oncol 2021;30(11):1876–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Watt CL, Momoli F, Ansari MT, et al. The incidence and prevalence of delirium across palliative care settings: a systematic review. Palliat Med 2019;33(8):865–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Prabhakar A, Smith TJ. Total Pain. Palliative Care Network of Wisconsin. Mar 2021. Available at: https://www.mypcnow.org/fast-fact/total-pain/. Accessed Jan 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Friese G. How to use OPQRST as an effective patient assessment tool. EMS1 Online; 2020. Available at: https://www.ems1.com/ems-products/education/articles/how-to-use-opqrst-as-an-effective-patient-assessment-tool-yd2KWgJIBdtd7D5T/. Accessed January 2023.

- 45.Kematick B, Suliman I, Hood A, et al. The BWH/DFCI pain management tables and guidelines 2020. Available at: https://pinkbook.dfci.org/assets/docs/pinkBook.pdf. Accessed March 2023.

- 46.Ellison HB, Lau LA, Cook AC, et al. Surgical palliative care: considerations for career development in surgery and hospice and palliative medicine. American College of Surgeons; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weissman DE. Dyspnea at End-of-Life. Palliative Care Network of Wisconsin. 2015. Available at: www.mypcnow.org/fast-fact/dyspnea-at-end-of-life/. Accessed March 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ahmed A, Graber MA. Approach to the adult with dyspnea in the emergency department. UpToDate 2022. Available at: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/approach-to-the-adult-with-dyspnea-in-the-emergency-department. Accessed March 2023.

- 49.Hui D, Bohlke K, Bao T, et al. Management of dyspnea in advanced cancer: ASCO guideline. J Clin Oncol 2021;39(12):1389–411. 10.1200/JCO.20.03465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mularski RA, Reinke LF, Carrieri-Kohlman V, et al. An official American Thoracic Society workshop report: assessment and palliative management of dyspnea crisis. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2013;10(5):S98–106. 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201306-169ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Quest TE, Lamba S. Palliative for adults in the ED: Concepts, presenting complaints, and symptom management. UpToDate; 2022. Available at: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/palliative-care-for-adults-in-the-ed-concepts-presenting-complaints-and-symptom-management. Accessed March 2023.

- 52.Prachanukool T, Kanjana K, Lee RS, et al. Acceptability of the palliative dyspnoea protocol by emergency clinicians [published online ahead of print, 2022 Sep 16]. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2022. 10.1136/spcare-2022-003959. spcare-2022–003959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lamba S, Quest TE. Hospice care and the emergency department: rules, regulations, and referrals. Ann Emerg Med 2011;57(3):282–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Desandre PL, Quest TE. Management of cancer-related pain. Emerg Med Clin North Am 2009;27(2):179–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Barbera L, Taylor C, Dudgeon D. Why do patients with cancer visit the emergency department hunear the end of life? CMAJ (Can Med Assoc J) 2010;182(6):563–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bailey CJ, Murphy R, Porock D. Dying cases in emergency places: caring for the dying in emergency departments. Soc Sci Med 2011;73(9):1371–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.World Health Organization. Quality health services and palliative care: practical approaches and resources to support policy, strategy and practice. 2021. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240035164. Accessed March 2023.

- 58.Goett R, Isaacs ED, Chan GK, et al. Quality measures for palliative care in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med 2023;30(1):53–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.De Roo ML, Leemans K, Claessen SJ, et al. Quality indicators for palliative care: update of a systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage 2013;46(4):556–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]