Abstract

This article presents the diagnostic and therapeutic journey of a 14-year-old male patient diagnosed with Primary Amebic Meningoencephalitis (PAM), incorporates a review of pertinent literature and a discussion on recent advancements in the study of this condition. The patient presented with symptoms of fever and headache for three days, accompanied by seizures and a half-day episode of altered consciousness. Upon admission, clinical findings included a mild coma, respiratory distress, rigidity of limbs, and negative pathological reflexes. The patient's history showed in a local outdoor pond swimming in July and August of the same year. Metagenomic Next-Generation Sequencing (mNGS) of the cerebrospinal fluid identified the presence of Naegleria fowleri. Cranial CT and MRI scans indicated signs of brain edema and meningitis. The patient was confirmed with pediatric primary amebic meningoencephalitis. A 45-day comprehensive treatment regimen was administered, encompassing anti-amebic medications, anticonvulsant therapy, management of brain edema, and intracranial pressure reduction. This case represents the longest survival period recorded for such pediatric cases in China. The purpose of this report is to heighten clinical awareness of PAM, share diagnostic and therapeutic insights, expand upon existing treatment approaches, and ultimately contribute to improving the survival rates of PAM patients.

Keywords: Intracranial infection, Pediatric meningoencephalitis, Naegleria fowleri

Highlights

-

•

PAM is a severe CNS infection in children. mNGS aids in early pathogen detection.

-

•

This case report found motile amoebae in CSF. Using artemisinin may inhibit amoeba reproduction and improve symptoms.

-

•

This case achieved the longest recorded survival, offering insights to improve therapeutic efficacy for amebic encephalitis.

Introduction

Primary amebic meningoencephalitis (PAM) is a rare infectious disease of the central nervous system caused by the Naegleria fowleri amoeba, also known as the "brain-eating amoeba." Naegleria fowleri is a thermophilic flagellated protozoan that exists in three forms: trophozoites, flagellates, and cysts, and is widespread in natural environments like air, soil, and water sources [1]. It can also parasitize within a host. Children and adolescents are susceptible to PAM. Its natural habitats include hot springs, ponds, rivers, and freshwater lakes. However, it has also been detected in untreated swimming pools, fountains, untreated drinking water, and water parks [2]. Contact with contaminated water sources through the sinuses is the most common route of infection, leading to purulent hemorrhagic inflammation and necrotic changes in the olfactory bulb and extensive brain tissue, causing damage to central nervous system tissues [3]. After the onset of PAM, the condition deteriorates explosively, which lead to an extremely low survival rate and more than a 95 % mortality rate since there are no effective medications available. In China, there has been only one reported case of an adult survivor, and did not report survival cases in children [4]. Most unconfirmed patients die rapidly within 3–7 days after onset [5], and confirmed cases usually die within two weeks [1]. Here, we report the clinical characteristics, diagnosis, and treatment of a 14-year-old male child with PAM admitted to our pediatric intensive care unit, combined with a literature analysis.

Patient data

A 14-year-old male patient became symptomatic on September 1st and was hospitalized on September 4th, 2023, presenting with fever, headache, seizures, and altered consciousness. He initially experienced unprovoked fever three days prior to hospitalization, peaking at 39.6 ℃, and was accompanied by dizziness and headache. Since his condition worsened, manifesting in coma and seizures, necessitating transfer to the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU) in Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University. His medical history was unremarkable, including routine immunizations, with no history of febrile seizures, head trauma, or familial genetic disorders. Epidemiological inquiry revealed that in July and August of the same year, the patient had swum on three occasions in a natural lake at a local ecological tourism park with peers; he developed fever on September 1, while his companions remained asymptomatic. An informed consent was obtained for this report.

Clinical Examination Upon Admission: The patient's temperature was 39.8 °C, respiratory rate 50 breaths per minute, heart rate 96 beats per minute, and blood pressure 93/61 mmHg. He was in a shallow coma, unresponsive to verbal stimuli, with a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 5, characterized by no verbal response, no eye-opening to stimulation, and flexor response to pain, indicative of decorticate posturing. The patient exhibited mottled skin without rash, cool extremities, and generalized rigidity. Pupillary examination showed bilateral, equal, and round pupils, approximately 4 mm in diameter, with brisk photic responses. Neck stiffness was noted, and superficial lymph nodes were not palpably enlarged. He presented with cyanosis of the lips and respiratory distress, evidenced by an inspiratory retraction. Cardiac examination revealed strong, regular heart sounds without murmurs. The abdomen was soft and flat, without hepatosplenomegaly, and bowel sounds were normal. The limbs showed increased muscle strength and tone. Pathological reflexes, including the signs of Kernig, Brudzinski, Babinski and Gordon were all negative.

Diagnosis and treatment

The patient began exhibiting symptoms on September 1, including seizures and a disturbed consciousness, which rapidly evolved into respiratory and circulatory failure. After transferred to our PICU, immediate endotracheal intubation and invasive mechanical ventilation were initiated. This was followed by comprehensive diagnostics including complete blood count, biochemical, immunological, and pathogen screening tests. When the patient's vital signs were temporarily stabilized, an urgent brain MRI was performed, indicating signs of meningitis without evidence of brain herniation (Fig. 1a, b). Lumbar puncture revealed increased intracranial pressure. Further evaluations including cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) routine analysis, 5 mL CSF for biochemical tests, and 3 ml for metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) were conducted. CSF analysis revealed an elevated level of total nucleated cell count (187 cells/uL), with 53 % mononuclear and 47 % multinuclear cells. CSF biochemistry showed increased level of protein (3.24 g/L), lactate dehydrogenase (298 U/L), and lactate (10.61 mmol/L), along with decreased level of glucose (0.32 mmol/L) and chloride (115.9 mmol/L). CSF adenosine deaminase was 7 U/L. The CSF characteristics suggested bacterial meningitis. However, the observed elevation in the total count of nucleated cells was inconsistent with the typical CSF profile associated with bacterial meningitis.

Fig. 1.

Brain MRI images. a, b are brain MRI images from day 1 showing slightly high T2 FLAIR signal in the right parietal lobe sulci, No indications of brain herniation were detected. c, d are brain MRI images from day 7 showing shallower cerebral sulci, increased T2 FLAIR signal, and the formation of cerebellar tonsillar herniation.

On the first day post-admission, the patient's seizures abated, deep reflexes returned, and there was a transient regaining of consciousness. By the second day, he progressed from a shallow to a deep coma, autonomous breathing ceased, and circulatory instability emerged. Pupil examination showed asymmetry, with the right pupil at 6 mm and the left at 5 mm, absent light reflex, and no response to stimuli. Neither pathological signs nor tendon reflexes were elicitable. Concurrently, CSF mNGS identified a high count of Naegleria genus amoeba sequences (52,237, relative abundance 93.08 %) in 12 h after samples collection, including Naegleria fowleri (35,598 sequences, relative abundance 63.43 %). Active protozoa were visualized in the CSF, leading to a confirmed diagnosis of Primary Amebic Meningoencephalitis (Supplementary Fig. 1).

In the absence of standardized international treatment protocols for PAM, a regimen based on literature recommendations was employed. Considering that the child weighed about 60 kg, we referred to the adult dose for treatment, including Amphotericin B (10 mg/dose, intravenously once daily), Rifampin (0.3 g/dose, orally twice daily), Sulfamethoxazole(400 mg)-Trimethoprim(80 mg)/tablet (3 tablets per dose, orally four times daily), and Fluconazole (0.4 g/dose, intravenously once daily) for anti-amebic therapy [6]. Literature review highlighted the efficacy of Artemisinin, a natural compound derived from the traditional Chinese herb Artemisia, against various protozoa. Its derivative, Artesunate, demonstrated notable effectiveness in treating protozoan-induced central nervous system diseases [7]. With family’s consent, Artesunate-Pyronaridine (80 mg/dose, orally twice daily) was added, along with intrathecal Amphotericin B (0.1 mg) and Dexamethasone (5 mg) once per week. The patient showed gradual improvement, with reduced cerebral edema, stabilized circulation, resumption of autonomous breathing, equal and round pupils approximately 5 mm in diameter, restored light reflex, occasional involuntary movement in the right upper limb, flexor response upon right upper limb stimulation, and recovery of cremasteric, abdominal, and cough reflexes.

On day seven, the patient's condition deteriorated, evidenced by central hyperthermia and a continuous decline in blood pressure. He lapsed into a deeper coma, autonomous breathing ceased again, and pupils were about 5 mm on the right and 6 mm on the left, without light reflex. Involuntary limb movements were decreased compared to before. A repeated cranial MRI indicated aggravated encephalitis and the formation of cerebellar tonsil herniation (Fig. 1c, d). The ongoing anti-amebic and comprehensive treatments were maintained. The patient occasionally demonstrated autonomous breathing and stable blood pressure. Continuous monitoring showed increasing levels of transaminases, urea, and creatinine, which improved upon cessation of hepatorenal toxic medications.

Approximately three weeks after initiating invasive respiratory support, a bedside tracheostomy was performed, transitioning to ventilator support via the tracheostomy. The patient's condition continued to deteriorate slowly, with persistent worsening of cerebral edema. By day 34, ocular protrusion was noted, pupils were enlarged to about 7 mm, equally sized, with no significant light reflex. On day 40, bleeding was observed from the oral and nasal cavities, as well as the ears, and the conjunctiva showed patchy hemorrhages, accompanied by facial edema and tongue protrusion. Subsequent brain CTs indicated progressively increasing cerebral edema and continuous presence of cerebellar tonsil herniation. Continuous video EEG monitoring failed to detect brain waves. On day 45, the patient's family opted to discontinue treatment.

Laboratory investigations

Upon admission, the patient underwent a series of comprehensive laboratory investigations, including complete blood count, biochemical assays, immunological profiles, and pathogen screening. Notably, all pathogen tests, except those conducted on CSF, yielded no positive findings for bacterial presence. Autoimmune encephalitis panel comprising six markers and the complete immunoglobulin profile were within normal limits. Basic blood biochemical parameters were also found to be normal. CSF samples underwent bacterial India ink, acid-fast, and Gram staining, which ruled out the presence of cryptococcus, acid-fast bacilli, and other bacterial pathogens.

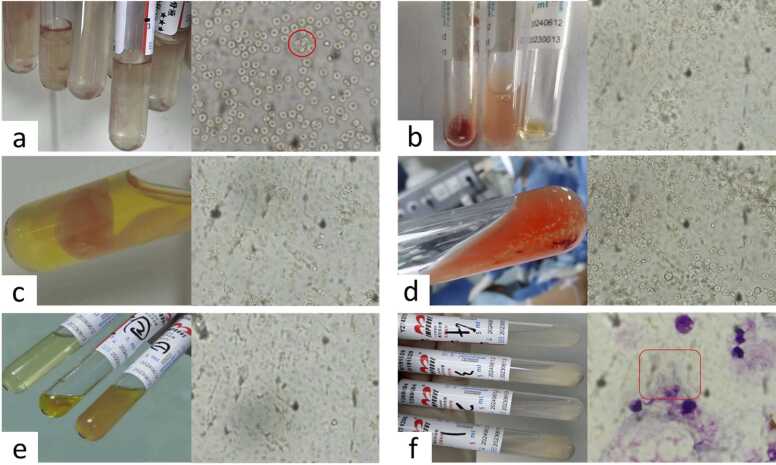

The patient underwent dynamic monitoring, involving regular assessment of blood parameters, lymphocyte subgroups (Supplementary Fig. 2), cytokine levels (Supplementary Fig. 3), CSF appearance and microscopic examination (Fig. 2), along with routine CSF analysis and biochemical testing. The initial lumbar puncture yielded an 8 ml CSF sample, which was submitted to Yaji Technology Testing Company, located in Nanshan District, Shenzhen Bay Eco-Technology Park, Shenzhen, China, for comprehensive DNA + RNA microbial metagenomic sequencing. The sequencing results were significant for the presence of Naegleria species, with a particular emphasis on Naegleria fowleri. The sequence count for Naegleria spp. was 52,237, accounting for a relative abundance of 93.08 %, and for Naegleria fowleri, the sequence count was 35,598, with a relative abundance of 63.43 %. The assay did not detect any other pathogenic entities, including bacteria, mycobacteria, mycoplasma, chlamydia, rickettsia, fungi, DNA viruses, RNA viruses, suspected human commensal microbes, or resistance genes.

Fig. 2.

Appearances of cerebrospinal fluid and microscopic observations. a–f are the appearances of cerebrospinal fluid and microscopic observations on admitted days 1, 7, 9, 11, 16, and 28. On the first day, active trophozoites are visible, while on the other days, no active amoebae were observed, but on the 28th day, the trophozoites could be seen under staining.

Diagnosis and differential considerations

The constellation of the patient’s clinical presentation, including symptoms, physical findings, supportive diagnostic tests, epidemiological history, and pathogen identification, culminated in a definitive diagnosis of PAM in a pediatric patient. The case necessitated differential diagnosis from viral or bacterial encephalitis, particularly given the initial CSF findings of elevated cell count and decreased glucose levels, which could be misleadingly indicative of purulent meningitis. However, the critical detection of Naegleria fowleri amoeba through CSF metagenomic next-generation sequencing and the visualization of amebic protozoa under microscopy were decisive in establishing the diagnosis of PAM.

Discussion

Primary amebic meningoencephalitis is a rare central nervous system infection. Since the initial reporting of a PAM case in 1965, instances have been documented in various countries including China, the United States, Japan, Australia, India, Thailand, and New Zealand. A retrospective analysis conducted on PAM cases globally from 1962 to 2018 identified 182 diagnosed cases, with 6 survivors [6]. Between 2018 and 2022, an additional 16 cases of PAM were reported worldwide, out of which 2 patients survived [8]. By the end of 2021, 11 cases of PAM had been reported in China [9], with 5 new cases emerging. A search from 2021 to present revealed one adult male case reported in Wuhan in July 2022 [10]. To date, China has reported a total of 12 cases, including a 38-year-old male from Hong Kong who survived [4]. Globally, there have been approximately 204 confirmed cases of Naegleria fowleri meningoencephalitis, with 9 survivors, resulting in a mortality rate exceeding 95 %.

This case, involving a 14-year-old boy who was suspected to contract Naegleria fowleri from “contaminated” water, exemplifies the typical infection pathway of PAM. Differentiating PAM from other encephalitis types was initially challenging, but rapid diagnosis was achieved within 24 h through CSF mNGS, complemented by epidemiological history and disease progression. CT and MRI imaging confirmed cerebral edema and encephalitis, characteristic of PAM.

The explosive exacerbation of PAM post-onset, the lack of specific effective medications, and the poor efficacy of conventional drugs highlight the challenges in treatment and management. Currently, there are no child survivors in China. The rarity and high mortality rate of PAM present substantial challenges. In treatment, amphotericin B is one of the most recognized drugs, utilized in all reported survivor cases. In vitro studies suggest amphotericin B kills amoebas by disrupting the cytoplasm, a key mechanism in inhibiting amebic proliferation [11]. However, there is no consensus on the effective inhibitory concentration of amphotericin B against amoebas. Fluconazole, an antifungal, synergizes with amphotericin B to enhance CNS penetration and neutrophil recruitment to clear Naegleria fowleri [12], and has demonstrated additional benefits in combination therapy for PAM [13]. Among PAM survivors, 2 received miltefosine treatment, which acts primarily by inhibiting protein kinase B and has shown efficacy against Naegleria fowleri [14], with high stability and low interaction risk when used in combination therapy [15]. The American Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has approved miltefosine for clinical use when necessary.[16] Azithromycin, a macrolide antibiotic, has auxiliary efficacy in treating PAM [17]. Amphotericin B, fluconazole, miltefosine, and azithromycin are currently regarded as effective in treating PAM. Rifampin, although used in almost all survivor cases, is prone to interactions in combination therapy, affecting efficacy [18]. Artemisinin, extracted from the traditional Chinese herb Artemisia, has significant efficacy in treating central nervous system infections caused by non-malarial protozoa [7].

During the initial phase of the disease, a marked decrease in CD4 + T lymphocytes is observed among lymphocyte subpopulations. The underlying mechanisms by which Naegleria fowleri infection affects the immune system remain largely unclear. Initially, the immune system may mount a robust response to control the swiftly advancing infection and counter the invasive amoeba. Studies suggest that Naegleria fowleri exerts direct cytotoxic effects on T cells, potentially leading to a decrease in CD4 + T cells [19]. Additionally, the intense immune reaction triggers a cytokine storm and severe inflammatory responses, inflicting damage on body tissues, including immune cells themselves, which could contribute to the reduction in CD4 + T lymphocytes [20]. An increase in the count of CD4 + T cells was noted in the later stages. Early in the infection, CD4 + T cells migrate from the bloodstream to the site of infection (e.g., the brain), resulting in a transient decrease in CD4 + T cells in the circulation. The subsequent rise in CD4 + T cell production in the later stages may be attributed to immune regulation, but this requires further investigation. Early in the infection, we observed elevated levels of interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), which declined as the disease progressed, whereas interleukin-6 (IL-6) levels increased. This variation may correlate with the differing effects of the amoeba at various stages of infection. Throughout the immune response, IFN-γ and IL-6 play a pivotal role in maintaining the Th1/Th2 balance through mutual regulation. IFN-γ is a key cytokine in the Th1 immune response, crucial for Th1-type reactions [21]. Th1 responses, involving macrophages and natural killer (NK) cells, are primarily responsible for direct pathogen attack. High levels of IFN-γ in the early stages of infection activate macrophages, enhancing their pathogen phagocytosis and elimination efficacy. As the infection progresses, the immune response shifts from a Th1 to a Th2 type, moving the focus from macrophage-mediated immunity to humoral immunity, predominantly involving B cells and antibody production, as part of a long-term defense strategy against pathogens. IL-6 facilitates Th2 differentiation and inhibits Th1 polarization [22]. An increase in IL-6 levels, concurrent with a decrease in IFN-γ production, is indicative of a dominant Th2 response [23]. This shift represents the immune system's natural adaptation to prolonged infection, driven by: 1. A shift to Th2 response as a protective mechanism against continuous Th1-induced inflammation and tissue damage. 2. Recognition by the immune system of the need for sustained humoral immunity to control or eradicate the pathogen over time. 3. Possible manipulation of the host immune response by Naegleria fowleri, transitioning from Th1 to Th2, thereby diminishing IFN-γ production and attenuating phagocytosis and anti-amebic activities, thus reducing the risk of the amoeba being targeted.

Upon reviewing the diagnostic and therapeutic journey of this case, it's evident that PAM presents with non-specific early symptoms and routine test results, posing a challenge for rapid diagnosis. In this instance, the pediatric patient was diagnosed via CSF mNGS within 24 h of hospital admission. The treatment regimen included a combination therapy involving amphotericin B, fluconazole, rifampin, and artemisinin. Notably, early administration of intrathecal amphotericin B and corticosteroids, coupled with the innovative use of Artemisinin formulations, led to the disease's controlled progression and temporary clinical improvement. Remarkably, the child's survival duration was threefold longer than the global average for PAM, establishing this as the longest recorded survival case among pediatric PAM patients in China.

In light of the current diagnostic and therapeutic landscape, the rapid progression and high mortality rate of PAM necessitate heightened vigilance among physicians, particularly when dealing with vulnerable groups such as children. Prompt CSF mNGS testing can significantly enhance diagnostic accuracy in these cases.

Consent

Consent to publish this information was obtained from study his parents. Written informed consent was obtained from the patients and guarantees for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor of this journal.

Funding

No fund.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical approval

Ethics approval and consent to participate.This study was approved by the Medical Ethical Committee of Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University, clinical ethical approval number 2023241.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Binbin SONG: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Resources, Data curation. Junwen Zheng: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Formal analysis. Dongchi Zhao: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Formal analysis.

Declaration of Competing Interest

We declare that we have no financial and personal relationships with other people or organizations that can inappropriately influence our work, there is no professional or other personal interest of any nature or kind in any product, service and/or company that could be construed as influencing the position presented in, or the review of, the manuscript entitled.

Acknowledgments

None.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no conflict interests.

Author Contributions

Drs. Binbin Song conducted the data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, writing, and made the figures, and Drs. Junwen Zheng and Dongchi Zhao made the study design, data analysis, data interpretation and writing. All authors read and approved the final report and have no conflicting issues with the contributions listed herein.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.idcr.2024.e02028.

Contributor Information

Binbin Song, Email: 649944075@qq.com.

Junwen Zheng, Email: zhengjunwen@whu.edu.cn.

Dongchi Zhao, Email: zhao_wh2004@hotmail.com.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary material

Supplementary material

Supplementary material

Supplementary material

References

- 1.Güémez A., García E. Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis by Naegleria fowleri: pathogenesis and treatments. Biomolecules. 2021;11(9):1320. doi: 10.3390/biom11091320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jahangeer M., Mahmood Z., Munir N., et al. Naegleria fowleri: sources of infection, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management; a review. Clin Exp Pharm Physiol. 2020;47(2):199–212. doi: 10.1111/1440-1681.13192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grace E., Asbill S., Virga K. Naegleria fowleri: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment options. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59(11):6677–6681. doi: 10.1128/aac.01293-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang A., Kay R., Poon W.S., et al. Successful treatment of amoebic meningoencephalitis in a Chinese living in Hong Kong. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 1993;95(3):249–252. doi: 10.1016/0303-8467(93)90132-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rojo J.U., Rajendran R., Salazar J.H. Laboratory diagnosis of primary amoebic meningoencephalitis. Lab Med. 2023;54(5):e124–e132. doi: 10.1093/labmed/lmac158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gharpure R., Bliton J., Goodman A., et al. Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of primary amebic meningoencephalitis caused by naegleria fowleri: a global review. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73(1):e19–e27. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Loo C.S., Lam N.S., Yu D., et al. Artemisinin and its derivatives in treating protozoan infections beyond malaria. Pharm Res. 2017;117:192–217. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2016.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahmad Zamzuri M.'i., Abd Majid F.N., Mihat M., et al. Systematic review of brain-eating amoeba: a decade update. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(4) doi: 10.3390/ijerph20043021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen X.T., Zhang Q., Wen S.Y., et al. Pathogenic free-living amoebic encephalitis from 48 cases in China: a systematic review. Front Neurol. 2023;14 doi: 10.3389/fneur.2023.1100785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhu Canmin, Wang Dili, Peng Weijian, et al. A case of acute primary amoebic meningoencephalitis. Front Neurol. 2023;41(04):524–526. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2023.1100785. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cárdenas-Zúñiga R., Silva-Olivares A., Villalba-Magdaleno J.A., et al. Amphotericin B induces apoptosis-like programmed cell death in Naegleria fowleri and Naegleria gruberi. Microbiology. 2017;163(7):940–949. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.000500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacobs S., Price Evans D.A., Tariq M., et al. Fluconazole improves survival in septic shock: a randomized double-blind prospective study. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(7):1938–1946. doi: 10.1097/01.Ccm.0000074724.71242.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee K.K., Karr S.L., Jr., Wong M.M., et al. In vitro susceptibilities of Naegleria fowleri strain HB-1 to selected antimicrobial agents, singly and in combination. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1979;16(2):217–220. doi: 10.1128/aac.16.2.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schuster F.L., Guglielmo B.J., Visvesvara G.S. In-vitro activity of miltefosine and voriconazole on clinical isolates of free-living amebas: Balamuthia mandrillaris, Acanthamoeba spp., and Naegleria fowleri. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 2006;53(2):121–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.2005.00082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sindermann H., Engel J. Development of miltefosine as an oral treatment for leishmaniasis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2006;100 Suppl. 1:S17–S20. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2006.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Investigational drug available directly from CDC for the treatment of infections with free-living amebae. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62(33):666. [PMC4604798] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goswick S.M., Brenner G.M. Activities of azithromycin and amphotericin B against Naegleria fowleri in vitro and in a mouse model of primary amebic meningoencephalitis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47(2):524–528. doi: 10.1128/aac.47.2.524-528.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nicolau D.P., Crowe H.M., Nightingale C.H., et al. Rifampin-fluconazole interaction in critically ill patients. Ann Pharmacother. 1995;29(10):994–996. doi: 10.1177/106002809502901007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee Y.A., Kim K.A., Shin M.H. Naegleria fowleri Induces Jurkat T Cell Death via O-deGlcNAcylation. Korean J Parasitol. 2021;59(5):501–505. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2021.59.5.501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen C.W., Moseman E.A. Pro-inflammatory cytokine responses to Naegleria fowleri infection. Front Trop Dis. 2022;3 doi: 10.3389/fitd.2022.1082334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bradley L.M., Dalton D.K., Croft M. A direct role for IFN-gamma in regulation of Th1 cell development. J Immunol. 1996;157(4):1350–1358. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.157.4.1350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Diehl S., Rincón M. The two faces of IL-6 on Th1/Th2 differentiation. Mol Immunol. 2002;39(9):531–536. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(02)00210-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sasai M., Yamamoto M. Innate, adaptive, and cell-autonomous immunity against Toxoplasma gondii infection. Exp Mol Med. 2019;51(12):1–10. doi: 10.1038/s12276-019-0353-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material

Supplementary material

Supplementary material

Supplementary material