Abstract

Introduction

Primary Sjögren's syndrome (PSS) is a systemic autoimmune disease that mainly affects exocrine glands. Little is known about PSS associated cervical and intracranial cerebral large-vessel vasculitis outside of individual case reports.

Methods

We present 5 cases of ischemic stroke or transient ischemic stroke (TIA) caused by PSS associated cervical and intracranial large-vessel vasculitis. Literature review was performed to summarize and identify the demographic, clinical features, treatment, and prognosis of this condition.

Results

The review resulted in 8 included articles with 8 patients, plus our 5 new patients, leading to a total of 13 subjects included in the analysis. The median age was 43 (range, 17–69) years old, among which 69.2 % (9/13) were female, and 92.3 % (12/13) came from Asia. Among them, 84.6 % (11/13) presented with cerebral infarction and 70.0 % (7/10) with watershed infarction. Middle cerebral artery (MCA) (6/13, 46.2 %) and internal carotid artery (ICA) (6/13, 46.2 %) were the most frequently involved arteries. Remarkable vessel wall concentric thickening and enhancement was observed in 57.1 % (4/7) patients and intravascular thrombi was identified in 28.6 % (2/7) patients. Glucocorticoid combined with non-glucocorticoid immunosuppressants (8/12, 66.7 %) were the most often chosen medication therapy and 4 patients received surgical intervention.

Conclusion

Asian females are the most vulnerable population to ischemic stroke or TIA due to PSS associated cervical and intracranial large-vessel vasculitis. Cerebral infarctions were characterized by recurrence and watershed pattern. Magnetic resonance vessel wall imaging (MR-VWI) helps to identify the inflammatory pathology of large vessel lesion in PSS.

Keywords: Primary Sjögren's syndrome, Large vessel vasculitis, Ischemic stroke, Magnetic resonance vessel wall imaging, Case report

1. Introduction

Primary Sjögren's syndrome (PSS) is a systemic progressive autoimmune disease characterized by diminished lacrimal and salivary gland function. Lymphocytic infiltration of lachrymal and salivary glands is the hallmark of the disease. While the typical symptoms of PSS include xerophthalmia, xerostomia, arthralgia, myalgia and severe fatigue, other major organ involvement is also often seen including pneumonitis, renal tubular acidosis, pancreatitis, myositis [44]. Neurological involvement is also a common extra-glandular manifestation of PSS affecting the peripheral nervous system (PNS) and central nervous system (CNS). According to different cohorts, neurological manifestations can occur in 4–20 % of PSS patients with PNS being more frequently involved than CNS [7,11,14,15]. The CNS manifestations of PSS include diffuse abnormalities (psychiatric changes, encephalopathy, aseptic meningitis, and cognitive difficulties/dementia) and focal encephalic involvement presenting as neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders (NMOSD), multiple sclerosis-like syndromes, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-like syndromes, and stroke-like syndromes [5,28]. The prevalence of CNS involvement in PSS is approximately 1–5% [30], while PSS related cerebral vasculitis was reported to be 1.3 % [11]. Small-vessel vasculitis has been considered as a pathogenic mechanism of the CNS manifestations of PSS [1,4]. Generally speaking, PSS rarely involves cerebral large-vessel arteries [[19], [20], [21], [22],26,31,32,38,41,45,46], leading to ischemic stroke.

We describe 5 new cases of ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack due to cervical and intracranial large-vessel vasculitis secondary to PSS, and review the previously published reports of the entity.

2. Methods

A literature search of published cases of ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack due to cervical and intracranial large-vessel vasculitis secondary to PSS was performed on Oct 8, 2022, by searching PubMed and Google Scholar with the terms: “Primary Sjögren's syndrome,” “vasculitis,” “stroke,” “cerebral artery occlusion/stenosis.” The inclusion criteria were: (1) Ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA); (2) Primary Sjögren's syndrome; (3) Other causes of ischemic stroke or TIA rather than PSS were excluded; (4) Cerebral vascular imaging confirmed large artery occlusion or stenosis (common carotid artery, internal carotid artery, middle cerebral artery stem or M1 segment, vertebral artery, basilar artery, subclavian artery, posterior cerebral artery stem or P1 segment).

3. Results

3.1. Case 1

A 66-year-old woman with a history of well controlled hypertension was admitted to an outside hospital for sudden onset of right limb weakness. She had no other vascular risk factors such as diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, atrial fibrillation, history of smoking or drinking. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed acute infarction of left frontoparietal lobe. Dual antiplatelets and statin were prescribed. The complete blood counting (CBC) was normal. ESR was 57 mm/h (0–20mm/h). The antinuclear antibody profile revealed anti-nuclear antibody was 1:320 positive, anti- Sjögren's syndrome-related antigen A (SSA/Ro) was strong positive, while SSB was negative. Ultrasonography indicated diffuse glandular hyperecho of bilateral parotid gland and submandibular gland. Labial gland biopsy revealed focal lymphocytic sialadenitis with lymphocytes infiltration more than 10 foci/4 mm2. Thus, the diagnosis of PSS was established and she was further prescribed with prednisone and hydroxychloroquine. She presented with recurrent episodes of right limbs weakness within the following 3 months. Further digital subtraction angiography revealed severe stenosis of the ophthalmic segment of the left internal carotid artery (ICA) (Fig. 1A). MR vessel wall imaging (MR-VWI) of ICA revealed smooth concentric wall thickening with homogenous enhancement involving the petrous segment of left ICA, suggestive of vasculitis (Fig. 1B). Therefore, large-vessel vasculitis secondary to PSS was diagnosed. The patient was treated with intravenous methylprednisolone followed by oral prednisone, along with cyclophosphamide 0.8g per month and hydroxychloroquine. In the following 4 months, recurrent episodes of right limb weakness occurred 3 times and brain MRI revealed recent infarction of the left frontal lobe (Fig. 1C). CT angiography (CTA) revealed occlusion of the origin of ICA, suggesting the progression of vasculitis of ICA (Fig. 1D). MR-VWI imaging of MCA revealed occlusion of left ICA with intravascular thrombi (Fig. 1E). The antithrombotic strategy was adjusted to rivaroxaban 20mg per day. After the dosage of cyclophosphamide (CTX) accumulated to 10g, stroke recurrence was well controlled and oral mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) was prescribed as an alternative of intravenous CTX. The MR-VWI 22 months post the index stroke revealed severe stenosis of the left ICA and partially recanalization of ICA after treatment of anticoagulation and immunosuppressants (Fig. 1F).

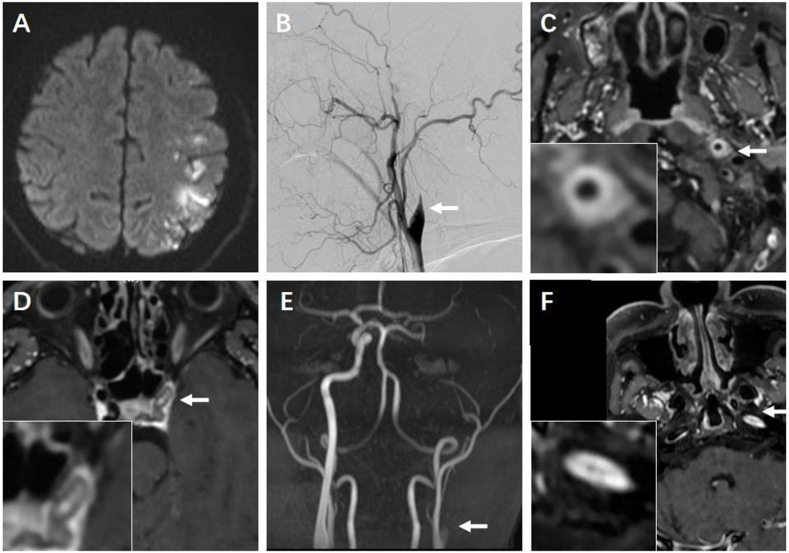

Fig. 1.

Brain and vascular images of Case 1. A) Digital subtraction angiography 3 months after the index stroke revealed severe stenosis (arrow) of the ophthalmic segment of left intracranial carotid artery (ICA). B) MR vessel wall imaging (MR-VWI) of ICA revealed smooth homogenous concentric wall thickening with enhancement involving the petrous segment of left ICA (arrow). C) During follow-up brain MRI revealed recent infarction of the left frontal lobe. D) CT angiography suggested CT angiography (CTA) revealed occlusion of the origin of ICA 8 months after the index stroke. E) MR-VWI of left ICA revealed thrombi within left ICA. F) MR-VWI revealed severe stenosis of left ICA and intravascular thrombi was alleviated 22 months after index stroke.

3.2. Case 2

A 41-year-old man without any past medical history presented with weakness and hemihypoesthesia of right limbs. Brain MRI revealed acute infarction in the left frontoparietal lobe and the insula (Fig. 2A). CT angiography demonstrated occlusion of the left ICA. He was treated with dual antiplatelets and statin. Due to a high-tier (1:1000) of antinuclear antibody (ANA) and positivity of SSA, ischemic stroke associated with an autoimmune disease was suspected at the outside hospital and he was transferred to our hospital. Digital subtraction angiography (DSA) confirmed occlusion of the C1 segment of left ICA (Fig. 2B). Further evaluation of the affected vessel wall using MR-VWI revealed concentric wall thickening with homogenous enhancement of left ICA (Fig. 2C) and intravascular thrombi was observed (Fig. 2D). Labial gland biopsy revealed 2 foci of lymphocytic sialadenitis with plasma cell infiltrating more than 50/foci. Considering of large vessel vasculitis associated with PSS, he was treated with intravenous methylprednisolone followed by oral prednisone, along with CTX 0.8g per month and hydroxychloroquine. Although magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) 8 months later still revealed occlusion of C1 segment of ICA (Fig. 2E) and vessel wall thickening and enhancement was also observable in MR-VWI of left ICA (Fig. 2F), this patient was uneventful during a total follow-up of 13 months.

Fig. 2.

Brain and vascular images of Case 2. A) Brain MRI revealed acute infarction in the left frontoparietal lobe and insula. B) DSA revealed occlusion of the C1 segment of left ICA (arrow). C) MR-VWI revealed wall thickening with enhancement involving the cavernous segment of left ICA (arrow). D) Intravascular thrombi (arrow) in left ICA. E) MRA 8 months post index stroke still revealed occlusion of C1 segment of ICA. F) MR-VWI with intravascular thrombi.

3.3. Case 3

A 32-year-old male without any previous medical history presented with sudden onset of slurred speech and weakness of left limbs. Brain MRI demonstrated acute infarction in right paraventricular area. CTA showed occlusion of right MCA. Due to the positivity of SSA/Ro 52 and Ro 60, comorbidity of autoimmune disease was suspected. He was treated with dual antiplatelets and hydroxychloroquine. Four months later, he was transferred to our hospital seeking further intervention of the occluded MCA. DSA revealed severe stenosis of the M1 segment of right MCA. Serological tests of rheumatoid connective tissues showed: ANA 1:1000, SSA (+), Ro52 (+), SSB (−). The patient reported symptoms of dry eyes for 2 years. Ophthalmology evaluation revealed evidence of severe xerostomia with reduction of tear film break up time to less than 2 seconds (1.3 seconds) in the left eye. He refused labial gland biopsy. As his symptoms continuously alleviated, the above treatment was maintained. And there was no stroke recurrence during a follow-up of 5 months.

3.4. Case 4

A 36-year-old women without any previous medical history was admitted for weakness and numbness of the left limbs. Brain MRI revealed infarction of the right pons and cerebellum. DSA suggested basilar artery (BA) was uneven in thickness and severe stenosis was observed in the distal BA. The antinuclear antibody profile revealed positivity for SSA/Ro, SSB negative, and ANA 1:1000 positive. The tear film rupture test was positive. She was treated with aspirin 100mg/day, clopidogrel 75mg/day, and atorvastatin 20mg/day. Hydroxychloroquine 200mg/day was prescribed as treatment of PSS. Her neurological deficits were relived after medication and there was no stroke recurrence during a follow-up of 12 months.

3.5. Case 5

A 43-year-old women without any previous medical history presented with dry mouth, fever, and multiple lymph node enlargement and tenderness under the jaw, armpit and groin 2 years ago. After treatment with methylprednisolone, hydroxychloroquine, and CTX, these symptoms were alleviated and medication was discontinued 1 year ago. She complained cervical lymph node enlargement with local tenderness again 5 months ago, which was improved after 3 weeks of prednisolone and CTX. One month ago, she presented sudden onset of right facial drooping and right limb weakness and numbness. The antinuclear antibody profile revealed SSA positive, ANA 1:320. Schimer's test: left 8mm, right 6 mm. Labial gland biopsy revealed focal lymphocytic infiltration with lymphocytes more than 100 cells per foci. Brain MRI indicated infarction in the left parietooccipital lobe and basal ganglia. MR angiography indicated stenosis of M1 segment of left MCA. MR-VWI revealed thickening of the vessel wall of occluded MCA. Ischemic stroke caused by MCA vasculitis was considered relevant to PSS. Prednisone and CTX was used to treat PSS, and aspirin and statin for secondary prevention of ischemic stroke. She recovered from right limb weakness and was followed up for 2 years without recurrence.

3.6. Literature review

Our research initially yielded 11 articles, of which 3 were excluded (1 for language in Japanese [32], 1 for Sjögren's syndrome secondary to lupus erythematosus [26], and 1 for large-vessel disease combining with neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder [21]). Therefore, 8 patients from 8 articles were included [19,20,22,31,38,41,45,46] in addition to our 5 patients. A supplementary table was used to collect data including patient demographics, comorbidities, presentation, diagnostic testing, treatment, and prognosis (Table S1).

3.7. Demographics

Characteristics of the 13 patients are demonstrated in Table 1. The median age was 43 (17–69) years old. Nine patients (69.2 %, 9/13) were female (female: male, 2.25:1). Twelve out of 13 patients came from Asia (92.3 %) and 1 from Europe (7.7 %). More specifically, 7 was from China (53.8 %), 3 from Japan (23.1 %), 2 from India (15.4 %), and 1 from Turkey (7.7 %).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics and diagnosis.

| Characteristic | Categories | Number (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs) (N = 13) | Median (range) | 43 (17–69) |

| Gender (N = 13) | Male | 4 (30.8 %) |

| Female | 9 (69.2 %) | |

| Country (N = 13) | China | 7 (53.8 %) |

| Japan | 3 (23.1 %) | |

| India | 2 (15.4 %) | |

| Turkey | 1 (7.7 %) | |

| Location of ischemia (N = 13) | Anterior circulation | 10 (76.9 %) |

| Posterior circulation | 2 (15.4 %) | |

| Anterior and posterior circulation | 1 (7.7%s) | |

| Involved cervical and intracranial large vessels (N = 13) | ICA | 6 (46.2 %) |

| MCA | 6 (46.2 %) | |

| CCA | 1 (7.7 %) | |

| PCA | 1 (7.7 %) | |

| SubA | 1 (7.7 %) | |

| BA | 1 (7.7 %) | |

| Presenting symptoms (N = 13) | Cerebral infarction | 11 (84.6 %) |

| TIA | 2 (15.4 %) | |

| Infarction type (N = 10) | Watershed infarction | 7 (70.0 %) |

| Perforating branch | 3 (30.0 %) | |

| Duration of PSS symptoms | Duration before stroke, N = 4, yrs (Median (range)) | 2.0 (0.5–10.0) |

| Diagnose after stroke (N) | 9 (69.2 %) | |

| Risk factors of vascular diseases (N = 13) | HTN | 3 (23.1 %) |

| CHD | 2 (15.4 %) | |

| Smoking | 2 (15.4 %) | |

| DM | 1 (7.7 %) | |

| Drinking | 1 (7.7 %) | |

| Hyperlipidemia | 0 (0 %) | |

| AF | 0 (0 %) | |

| Comorbidities of other disease (N = 13) | APS | 1 (7.7 %) |

| SLE | 0 (0 %) | |

| TKA | 0 (0 %) | |

| GCA | 0 (0 %) | |

| Serum profile | SSA positive (N = 12) | 12 (100.0 %) |

| SSB positive (N = 9) | 5 (55.6 %) | |

| ANA≥1:320 (N = 4) | 3 (75.0 %) | |

| CSR (N = 6, Median (range), mm/h) | 20.0 (2.0–84.0) | |

| CRP (N = 6, Median (range), mg/L) | 3.61 (0.70–12.57) | |

| LDL-C (N = 6, Median (range), mmol/L) | 1.64 (0.67–2.84) | |

| HbA1c (N = 5, Median (range), %) | 5.6 (5.0–6.4) | |

| Labial gland biopsy confirmed lymphocyte foci | N = 13 | 10 (76.9 %) |

| Holter (N = 6) | Normal | 6 (100 %) |

| Cardiac ultrasound (N = 6) | Normal | 6 (100 %) |

| MR-VWI (N = 7) | Vessel wall thickening and enhancement | 5 (71.4 %) |

| Intravascular thrombi | 2 (28.6 %) |

CCA: common carotid artery, ICA: intracranial carotid artery, MCA: middle cerebral artery, PCA: posterior cerebral artery, BA: basilar artery, SubA: subclavian artery, HTN: hypertension, DM: diabetes mellitus, CHD: chronic heart disease, AF: atrial fibrillation, SLE: systemic lupus erythematosus, APS: antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, TKA: Takayasu arteritis, GCA: giant cell arteritis, ANA: antinuclear antibody, SSA: Sjögren's-syndrome-related antigen A, SSB: Sjögren's-syndrome-related antigen B, CSR: erythrocyte sedimentation rate, CRP: C-reactive protein, LDL-C: low density lipoprotein cholesterol, MR-VWI: MR vessel wall imaging.

3.8. Vascular evaluation

The ischemia was in anterior circulation in 10 patients (10/13, 76.9 %), in posterior circulation in 2 patients (2/13, 15.4 %) and in both anterior and posterior circulation in 1 patient (1/13, 7.7 %). ICA and MCA stenosis/occlusion each occurred in 46.2 % (6/13) of the 13 patients. Involvement in common carotid artery (CCA) (7.7 %, 1/13), posterior cerebral artery (PCA) (7.7 %, 1/13), subclavian artery (SubA) (7.7 %, 1/13) or basilar artery (BA) (7.7 %, 1/13) was less frequent.

High resolution MR was applied for vessel wall imaging in 7 patients. Markers of inflammatory vascular pathology such as marked vessel wall concentric thickening and enhancement indicated were observed in 5 patients (71.4 %, 5/7) (Case 1, Case2, Case 5 and in 2 previous cases [41,45]). Besides, in 28.6 % patients (2/7) (case 1 and 2), intravascular thrombi were observed.

3.9. Symptom and imaging

Majority of the reported ischemic cerebrovascular events was cerebral infarction (11/13, 84.6 %). The other 2 cases presented with recurrent TIA (15.4 %, 2/13). Among the 11 cases of cerebral infarction, MR imaging was presented in 10 cases and 70.0 % (7/10) was characterized as watershed infarction.

3.10. Comorbidities

The occurrence of index stroke or TIA preceded the diagnosis of PSS in 9 out of 13 patients (69.2 %). The other 4 patients had previous history of PSS for 2.0 (0.5–10.0) years. The proportions of vascular risk factors were as follows: hypertension (HTN) (3/13,23.1 %), smoking (2/13, 15.4 %), chronic heart disease (CHD) (2/13, 15.4 %), diabetes mellitus (DM) (1/13, 7.7 %), drinking (1/13, 7.7 %), and antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) (1/13, 7.7 %).

3.11. Serum profile

The median level of LDL-C was 1.64 (0.67–2.84) mmol/L, and HbA1c was 5.6 (5.0–6.4) %. Seventy-five percent (3/4) of patients presented ANA ≥1:320. SSA was positive in all patients (13/13, 100 %), and SSB was positive in 55.6 % (5/9). And the median erythrocyte sedimentation rate (CSR) was 20.0 (2.0–84.0) mm/h, C-reactive protein (CRP) was 3.61 (0.70–12.57) mg/L. In 10 out of 13 patients, the diagnosis of PSS was confirmed by labial gland biopsy.

3.12. Treatment

As illustrated in Table 2, among the 12 patients with therapy presented, 66.7 % of patients (8/12) were treated with glucocorticoids in combination with nonglucocorticoid immunosuppressants, and 33.3 % of patients (4/12) were treated with glucocorticoid alone. The frequency of nonglucocorticoid immunosuppressants used was as follows: 66.7 % hydroxychloroquine (8/12), 33.3 % CTX (4/12), 16.7 % azathioprine (2/12), 8.3 % MMF (1/12) and 8.3 % methotrexate (1/12). Antiplatelets alone were given in 41.7 % (5/12) patients, anticoagulation alone in 25.0 % patients (3/12), antiplatelets in combination with anticoagulation in 8.3 % patient (1/12). The remaining 3 patients were not treated with any antithrombotic medication (3/12). Four patients underwent surgery intervention, including 3 cases of extracranial-intracranial (EC-IC) bypass and 1 case of stenting.

Table 2.

Treatment and prognosis of the patients.

| Characteristic | Categories | Number (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Medication of PSS (N = 12) | Glucocorticoid alone | 0 (0 %) |

| Non-glucocorticoid immunosuppressants alone | 4 (33.3 %) | |

| Glucocorticoid + Non-glucocorticoid immunosuppressants | 8 (66.7 %) | |

| hydroxychloroquine | 8 (66.7 %) | |

| CTX | 4 (33.3 %) | |

| AZA | 2 (16.7 %) | |

| MMF | 1 (8.3 %) | |

| methotrexate | 1 (8.3 %) | |

| Medication of stroke (N = 12) | Antiplatelet alone | 5 (41.7 %) |

| Anticoagulation alone | 3 (25.0 %) | |

| Antiplatelet + anticoagulation | 1 (8.3 %) | |

| statin | 6 (41.2 %) | |

| Surgery | EC-IC bypass | 3 (23.1 %) |

| Stenting | 1 (7.7 %) | |

| Length of follow-up (month, N = 9) | Median (range) | 5.0 (1.0–24.0) |

| Initial functional outcome: stroke recurrence (N = 13) | after medication alone (N = 9) | 3 (33.3 %) |

| after surgery (N = 1) | 0 (0 %) | |

| after medication plus surgery (N = 3) | 0 (0 %) | |

| Final functional outcome: improved or uneventful (N = 11) | after medication alone | 7 (63.6 %) |

| after surgery alone | 1 (9.1 %) | |

| after medication plus surgery | 3 (27.3 %) | |

| Vascular Outcome (N = 3) | Aggravation of vascular stenosis | 2 (66.7 %) |

| Alleviation of vessel wall enhancement | 1 (33.3 %) |

PSS: primary Sjögren's-syndrome, CTX: cyclophosphamide, AZA: azathioprine, MMF: mycophenolate mofetil.

3.13. Prognosis

The prognosis of patients during a follow-up of 5 (1–24) months was illustrated in Fig. S1. Fifty percent (6/12) of patients was uneventful or got functional improvement after initial medication. Four out of 12 patients (33.3 %) experienced recurrent stroke or TIA after medication. Among them, 3 patients underwent extracranial-intracranial bypass and 1 patient had no further stroke when the dosage of CTX was accumulated to 10g. For 3 patients treated with medication in combination with surgery, two was uneventful during the follow-up. The other one experienced recurrent stroke 1 year after surgery and a second bypass was operated. For the final functional outcome, among the 11 patients with prognosis mentioned, 63.6 % (7/11) got function improved or uneventful after medication alone, 9.1 % (1/11) after surgery alone, and 27.3 % (3/11) after medication in combination with surgery.

Among the 3 patients with vascular outcome reported, 1 case reported disappearance of vessel wall enhancement after intensive immunosuppressive therapy. But in 2 cases, the occlusion of MCA was progressed to ICA although intensive immunosuppressive therapy was applied.

4. Discussion

PSS is the second most common chronic autoimmune disorder in Western countries characterizing by lymphocytic infiltration of exocrine glands [16]. In a 2015 meta-analysis of population-based studies, the overall incidence of PSS was 6.92 per 100,000 person-year [36], with that in Europe and Asia much higher than other populations (0.043 % vs. 0.01–0.05 %) [18,23,36]. In an analysis of 8310 subjects with PSS in an international, multicenter registry, the ratio of women to men was highest in Asian (27:1) and lowest in Black or African American (7:1) patients [9]. In our case series and literature review, the demographic features of cerebral large vessel vasculitis secondary to PSS are like those of PSS, with females and Asian populations being susceptible.

Classification of vasculitis is primarily based upon the predominant size of the vessels involved. Large-vessel vasculitis mainly include Takayasu arteritis and giant cell arteritis [35]. Both conditions involve the aorta and its major branches, and the giant cell arteritis primarily involves external carotid artery branches [29]. There are other forms of large vessel vasculitis that either have a specific name, such as idiopathic isolated aortitis, or are part of another form of vasculitis or systemic inflammatory condition, such as Cogan syndrome or relapsing polychondritis. The large-vessel vasculitis associated with Cogan syndrome resembles Takayasu arteritis, causing an occlusion of the aortic arch vessels with resultant upper and/or lower limb claudication or renal artery stenosis [12]. For relapsing polychondritis, vasculitis may be an integral part of the primary disease and vasculitis might involve large vessels (including the aorta and its branches to the head, neck, and extremities), medium-sized vessels, and small vessels [27]. On perspective of PSS, vasculitis is one of the most common extra-glandular manifestations. But the most frequent presentations are cutaneous vasculitis and skin rash. Rarely, patients of PSS might develop a necrotizing vasculitis of medium-sized arteritis resembling polyarteritis nodosa [40]. In our study, we reported that intracranial carotid artery and middle cerebral artery were the most frequently involved vessels for large-vessel vasculitis due to PSS, which is distinguished from the vascular involvement of other large-vessel vasculitis and the common presentation of PSS related vasculitis. However, there are some limitations of our study that the number of cases was small, the regions of patients were limited, and the involvement of large vessels outside the head and neck were not focused on. And it should be noted that as biopsy of large vessels were not practical, the diagnosis of large vessel vasculitis in the current study was clinically based and not pathologically grounded.

The prevalence of neurological involvement in Sjögren's syndrome vary due to disparate diagnostic criteria, referral bias, and whether these manifestations are symptomatic or not. The Assessment of Systemic Signs and Evolution in Sjögren's syndrome (ASSESS) cohort from France of 393 PSS patients suggested that neurological manifestations were present in 18.9 % (peripheral in 16 % and central in 3.6 %). The prevalence of cerebral vasculitis was 1.3 % [11]. A Chinese cohort study of 205 patients of PSS reported similar findings: 19.15 % PSS patients exhibited neurological abnormalities, including 13.17 % PNS manifestations and 9.76 % CNS manifestations [15]. The interaction between the innate and adaptive systems and immune-mediated mechanisms related to the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases play an important role in vascular damage. Proinflammatory cytokines and adhesion molecules released by systemic and local inflammation lead to endothelial damage and thrombosis [8]. Recently, a 20-year follow-up study which included 102 PSS patients, suggested that extraglandular involvement was associated with a higher prevalence of coronary disease. And anti-Ro/SSA and anti-La/SSB seropositivity was associated with higher prevalence of cardiac conductive abnormalities, arterial and venous thrombosis and stroke [39]. Increased platelet aggregation is important in thrombosis. Enhanced platelet activity in patients with PSS was reported in previous observational studies [33,34]. In other autoimmune disorder such as antiphospholipid syndrome (APS), thrombo-inflammation and atherosclerosis are emerging pathogenic mechanisms of cardiovascular disease in APS, involving platelet cell activation and aggregation and subsequent thrombin generation [43]. The relationship between autoimmune disorder and thrombosis or platelet aggregation might be one of the mechanisms for PSS related stroke.

Immune mediated vasculopathy is one of the assumed pathological mechanisms of CNS manifestations due to the involvement of autoimmune antibodies [25]. Among patients with PSS, anti-Ro (SSA) antibodies have been linked to the occurrence of systemic and peripheral vasculitis [3,10]. Delalende et al. identified that in 82 patients with PSS, anti-SSA was more evident in those presented with CNS symptoms [13]. Alexander et al. also suggested that the presence of anti-SSA/Ro antibodies was associated with more severe and more extensive CNS manifestations [4]. Biopsy proved spinal arteritis in PSS patients with CNS complications also supported the vasculitis theory. A 37-year-old woman with PSS developed systemic vasculitis and died of spontaneous subarachnoid hemorrhage. Postmortem examination suggested necrotizing arteritis with fibrinoid changes and infiltration of small- and medium-sized vessel wall with chronic, and in some areas acute, inflammatory cells was diffuse and involved the anterior spinal artery of the lower thoracic cord [2].

In our 5 cases, the age of onset (medium (range), 40 (30–67) yrs), lack of risk factors of cardiovascular disease and the existence of large vessel occlusion or stenosis without typical eccentric plaque in MR-VWI, lead to a low possibility of atherosclerosis as the pathologic process of ischemic stroke. Meanwhile, structural, or rhythmic cardiac abnormalities suggesting cardiogenic embolism were not found. Vessel wall thickening or concentric wall enhancement on MR-VRI lead to the consideration of large vessel vasculitis. Vasculitis is defined by the presence of inflammatory leukocytes in vessel walls with reactive damage to mural structures. As mentioned above, large-vessel vasculitis that impairs the CNS mainly include Takayasu arteritis and giant cell arteritis [35]. Takayasu arteritis usually occurs before the age of 30 years [37]. And GCA usually occurs in patients older than 50, with markedly increased incidence in the eighth and ninth decades of life [27]. The age at disease onset, the absence of narrowing of aorta and/or its primary branches in DSA, and the absence of claudication of extremities suggested that Takayasu arteritis is less likely according to the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) classification criteria [6]. In addition, patients of our 5 cases, did not present headaches, scalp tenderness, vison loss or jaw claudication. DSA did not show extracranial large vessel involvement, and its corresponding absent pulses or limb claudication was not observed. Therefore, the possibility of GCA is excluded. There were chances that the chronic inflammatory responses due to PSS impaired the cerebral large vessel walls. Up to now, large vessel involvement in PSS is limited to case reports [17,[19], [20], [21], [22],26,31,32,38,41,45,46]. Our study added to the previous evidence that large-vessel vasculitis secondary to PSS might cause ischemic stroke.

Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance vessel wall imaging (MR-VWI) has become recognized as a potential noninvasive vascular imaging modality to differentiate between intracranial atherosclerotic plaque, vasculitis, reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome, arterial dissection, and other causes of intracranial arterial narrowing [24]. MR-VWI often demonstrate smooth, homogeneous, concentric arterial wall thickening and enhancement in patients with CNS vasculitis, in comparison with the typical nonconcentric (and often heterogenous) wall abnormality of atherosclerotic plaque [42]. MR-VWI has been used to demonstrate the presence of an inflammatory etiology of the large vessel vasculitis secondary to PSS [41,45]. Coincident with these 2 reports, our cases (case1, 2, 5) also revealed smooth homogeneous concentric vessel wall thickening with enhancement in MR-VWI. It is a useful technique for detecting the response to immunosuppressants treatment. Disappearance of the affected vessel wall enhancement in MR-VWI is suggestive of efficacy of immunosuppressants of the presumed vascular inflammatory pathologies [41]. In one of our cases, 22 months after the first onset, the occluded ICA was partially recanalized after the treatment of anti-coagulation, prednisone and CTX. Based on previous literature [21] and our limited data, MR-VWI provided supplementary information to inflammation etiology of vascular occlusion, and had a diagnostic value to show the immunosuppressive treatment response.

The approach to extraglandular manifestations of PSS, such as vasculitis, generally includes use of glucocorticoids, animalarials (hydroxychloroquine), conventional nonbiologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs such as methotrexate, azathioprine, and other potent agents, including cyclophosphamide, and the anti-CD20 antibody rituximab [25]. The optimal management of large-vessel vasculitis induced by PSS has not yet been established due to the rarity of this condition. Coincident with previous reports [19,22,41], our 5 cases of patients were treated with nonglucocorticoid immunosuppressants alone or in combination with glucocorticoids. All five patients were received antiplatelets or anticoagulation as secondary prevention of ischemic stroke. Majority of the patients (our new cases and previous published cases) got improved or uneventful post initial medication. For the remaining, stroke recurrence ceased after surgery was combined with medication. This suggested that revascularization surgery is a reasonable option for those patients with recurrent stroke or TIA after initial medication.

5. Conclusion

The presenting cases added more evidence that ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack due to cervical and intracranial large-vessel vasculitis could be recognized as a rare CNS manifestation of PSS. Our review and analysis of 13 cases support that Asian women are the most vulnerable population to this condition. Recurrent watershed infarction in anterior circulation is often observed. MR-VWI helps to identify the inflammatory pathology of large vessel lesion in PSS.

Funding

This study was financially supported by Health Youth Backbone Project of Suzhou City (Qngg2021003), the National Science Foundation of China (82171282), the Scientific Program of Jiangsu Provincial Health Commission (M2020064), Suzhou Science and Technology Program (SYS2020101) to Juehua Zhu and Shanghai Municipal Health Commission (20204Y0425) to Shilin Yang.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethics approval

Ethical approval was waived by the local Ethics Committee of Huashan Hospital Fudan University and all the procedures being performed were part of the routine care.

Consent to participate

Patients signed informed consent regarding publishing their data and photographs.

Consent for publication

Informed consent was obtained from the patient for the and publication of personal data.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Juehua Zhu: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation. Qiang Dong: Supervision, Conceptualization. Zhipeng Cao: Methodology, Data curation. Yi Xu: Validation, Methodology, Formal analysis. Shufan Zhang: Validation, Resources. Qi Fang: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Conceptualization. Xiuying Cai: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Conceptualization. Xiang Han: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Conceptualization. Shilin Yang: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Formal analysis, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: Juehua Zhu reports financial support was provided by National Natural Science Foundation of China. If there are other authors, they declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

No.

Abbreviations

- PSS

primary Sjögren's-syndrome

- CCA

common carotid artery

- ICA

intracranial carotid artery

- MCA

middle cerebral artery

- PCA

posterior cerebral artery

- BA

basilar artery

- SubA

subclavian artery

- HTN

hypertension

- DM

diabetes mellitus

- CHD

chronic heart disease

- AF

atrial fibrillation

- SLE

systemic lupus erythematosus

- APS

antiphospholipid syndrome

- TKA

Takayasu arteritis

- GCA

giant cell arteritis

- ANA

antinuclear antibody

- SSA

Sjögren's-syndrome-related antigen A

- SSB

Sjögren's-syndrome-related antigen B

- CSR

erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- LDL-C

low density lipoprotein cholesterol

- EC-IC bypass

extracranial-intracranial bypass

- CNS

central nervous system

- PNS

peripheral nervous system

- NMO-SD

neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- MRA

magnetic resonance angiography

- CTA

computerized tomography angiography

- DSA

digital subtraction angiography

- MR-VWI

MR vessel wall imaging

- CTX

cyclophosphamide

- MMF

mycophenolate mofetil

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e34225.

Contributor Information

Xiang Han, Email: hansletter@fudan.edu.cn.

Shilin Yang, Email: yangshilin@gmail.com.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

figs1.

References

- 1.Alexander E.L. Neurologic disease in Sjogren's syndrome: mononuclear inflammatory vasculopathy affecting central/peripheral nervous system and muscle. A clinical review and update of immunopathogenesis. Rheum. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 1993;19:869–908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alexander E.L., Craft C., Dorsch C., Moser R.L., Provost T.T., Alexander G.E. Necrotizing arteritis and spinal subarachnoid hemorrhage in Sjogren syndrome. Ann. Neurol. 1982;11:632–635. doi: 10.1002/ana.410110614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alexander E.L., Hirsch T.J., Arnett F.C., Provost T.T., Stevens M.B. Ro(SSA) and La(SSB) antibodies in the clinical spectrum of Sjogren's syndrome. J. Rheumatol. 1982;9:239–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alexander E.L., Ranzenbach M.R., Kumar A.J., Kozachuk W.E., Rosenbaum A.E., Patronas N., Harley J.B., Reichlin M. Anti-Ro(SS-A) autoantibodies in central nervous system disease associated with Sjogren's syndrome (CNS-SS): clinical, neuroimaging, and angiographic correlates. Neurology. 1994;44:899–908. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.5.899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alunno A., Carubbi F., Bartoloni E., Cipriani P., Giacomelli R., Gerli R. The kaleidoscope of neurological manifestations in primary Sjogren's syndrome. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2019;37(Suppl 118):192–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arend W.P., Michel B.A., Bloch D.A., Hunder G.G., Calabrese L.H., Edworthy S.M., Fauci A.S., Leavitt R.Y., Lie J.T., Lightfoot R.W., Jr., et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of Takayasu arteritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33:1129–1134. doi: 10.1002/art.1780330811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baldini C., Pepe P., Quartuccio L., Priori R., Bartoloni E., Alunno A., Gattamelata A., Maset M., Modesti M., Tavoni A., De Vita S., Gerli R., Valesini G., Bombardieri S. Primary Sjogren's syndrome as a multi-organ disease: impact of the serological profile on the clinical presentation of the disease in a large cohort of Italian patients. Rheumatology. 2014;53:839–844. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ket427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bartoloni E., Shoenfeld Y., Gerli R. Inflammatory and autoimmune mechanisms in the induction of atherosclerotic damage in systemic rheumatic diseases: two faces of the same coin. Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63:178–183. doi: 10.1002/acr.20322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brito-Zeron P., Acar-Denizli N., Zeher M., Rasmussen A., Seror R., Theander E., Li X., Baldini C., Gottenberg J.E., Danda D., Quartuccio L., Priori R., Hernandez-Molina G., Kruize A.A., Valim V., Kvarnstrom M., Sene D., Gerli R., Praprotnik S., Isenberg D., Solans R., Rischmueller M., Kwok S.K., Nordmark G., Suzuki Y., Giacomelli R., Devauchelle-Pensec V., Bombardieri M., Hofauer B., Bootsma H., Brun J.G., Fraile G., Carsons S.E., Gheita T.A., Morel J., Vollenveider C., Atzeni F., Retamozo S., Horvath I.F., Sivils K., Mandl T., Sandhya P., De Vita S., Sanchez-Guerrero J., van der Heijden E., Trevisani V.F.M., Wahren-Herlenius M., Mariette X., Ramos-Casals M., Consortium E-STFBD Influence of geolocation and ethnicity on the phenotypic expression of primary Sjogren's syndrome at diagnosis in 8310 patients: a cross-sectional study from the Big Data Sjogren Project Consortium. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2017;76:1042–1050. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brito-Zeron P., Baldini C., Bootsma H., Bowman S.J., Jonsson R., Mariette X., Sivils K., Theander E., Tzioufas A., Ramos-Casals M. Sjogren syndrome. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2016;2 doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2016.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carvajal Alegria G., Guellec D., Mariette X., Gottenberg J.E., Dernis E., Dubost J.J., Trouvin A.P., Hachulla E., Larroche C., Le Guern V., Cornec D., Devauchelle-Pensec V., Saraux A. Epidemiology of neurological manifestations in Sjogren's syndrome: data from the French ASSESS Cohort. RMD Open. 2016;2 doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2015-000179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cochrane A.D., Tatoulis J. Cogan's syndrome with aortitis, aortic regurgitation, and aortic arch vessel stenoses. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 1991;52:1166–1167. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(91)91304-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Delalande S., de Seze J., Fauchais A.L., Hachulla E., Stojkovic T., Ferriby D., Dubucquoi S., Pruvo J.P., Vermersch P., Hatron P.Y. Neurologic manifestations in primary Sjogren syndrome: a study of 82 patients. Medicine (Baltim.) 2004;83:280–291. doi: 10.1097/01.md.0000141099.53742.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Delalande S., De Seze J., Ferriby D., Vermersch P. [Neurological manifestations in Sjogren syndrome] Rev. Med. Interne. 2010;31(Suppl 1):S8–S15. doi: 10.1016/j.revmed.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fan G., Dai F., Chen S., Sun Y., Qian H., Yang G., Liu Y., Shi G. Neurological involvement in patients with primary sjogren's syndrome. J. Clin. Rheumatol. 2021;27:50–55. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0000000000001128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fox R.I. Sjogren's syndrome. Lancet. 2005;366:321–331. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66990-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giordano M.J., Commins D., Silbergeld D.L. Sjogren's cerebritis complicated by subarachnoid hemorrhage and bilateral superior cerebellar artery occlusion: case report. Surg. Neurol. 1995;43:48–51. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(95)80037-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goransson L.G., Haldorsen K., Brun J.G., Harboe E., Jonsson M.V., Skarstein K., Time K., Omdal R. The point prevalence of clinically relevant primary Sjogren's syndrome in two Norwegian counties. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 2011;40:221–224. doi: 10.3109/03009742.2010.536164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hao L.J., Zhang J., Naveed M., Chen K.Y., Xiao P.X. Subclavian steal syndrome associated with Sjogren's syndrome: a case report. World journal of clinical cases. 2021;9:8171–8176. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i27.8171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hasiloglu Z.I., Albayram S., Tasmali K., Erer B., Selcuk H., Islak C. A case of primary Sjogren's syndrome presenting primarily with central nervous system vasculitic involvement. Rheumatol. Int. 2012;32:805–807. doi: 10.1007/s00296-011-1824-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ii Y., Shindo A., Sasaki R., Naito Y., Tanaka K., Kuzuhara S. Reversible stenosis of large cerebral arteries in a patient with combined Sjogren's syndrome and neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder. Rheumatol. Int. 2008;28:1277–1280. doi: 10.1007/s00296-008-0611-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kesav P., Hussain S.I., Devnani P., Namas R., Al-Sharif K., Thomas M., Altrabulsi B., John S. Primary sjogren's syndrome presenting as recurrent ischemic strokes. Neurohospitalist. 2022;12:341–345. doi: 10.1177/19418744211048593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maldini C., Seror R., Fain O., Dhote R., Amoura Z., De Bandt M., Delassus J.L., Falgarone G., Guillevin L., Le Guern V., Lhote F., Meyer O., Ramanoelina J., Sacre K., Uzunhan Y., Leroux J.L., Mariette X., Mahr A. Epidemiology of primary Sjogren's syndrome in a French multiracial/multiethnic area. Arthritis Care Res. 2014;66:454–463. doi: 10.1002/acr.22115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mandell DM, Mossa-Basha M, Qiao Y, Hess CP, Hui F, Matouk C, Johnson MH, Daemen MJ, Vossough A, Edjlali M, Saloner D, Ansari SA, Wasserman BA, Mikulis DJ, Vessel wall imaging study group of the American society of N (2017) intracranial vessel wall MRI: principles and expert consensus recommendations of the American society of neuroradiology. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 38:218-229. doi:10.3174/ajnr.A4893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Margaretten M. Neurologic manifestations of primary sjogren syndrome. Rheum. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2017;43:519–529. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2017.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matsuki Y., Kawakami M., Ishizuka T., Kawaguchi Y., Hidaka T., Suzuki K., Nakamura H. SLE and Sjogren's syndrome associated with unilateral moyamoya vessels in cerebral arteries. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 1997;26:392–394. doi: 10.3109/03009749709065707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maz M., Chung S.A., Abril A., Langford C.A., Gorelik M., Guyatt G., Archer A.M., Conn D.L., Full K.A., Grayson P.C., Ibarra M.F., Imundo L.F., Kim S., Merkel P.A., Rhee R.L., Seo P., Stone J.H., Sule S., Sundel R.P., Vitobaldi O.I., Warner A., Byram K., Dua A.B., Husainat N., James K.E., Kalot M.A., Lin Y.C., Springer J.M., Turgunbaev M., Villa-Forte A., Turner A.S., Mustafa R.A. 2021 American College of rheumatology/vasculitis foundation guideline for the management of giant cell arteritis and Takayasu arteritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021;73:1349–1365. doi: 10.1002/art.41774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCoy S.S., Baer A.N. Neurological complications of sjogren's syndrome: diagnosis and management. Curr Treatm Opt Rheumatol. 2017;3:275–288. doi: 10.1007/s40674-017-0076-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Michel B.A., Arend W.P., Hunder G.G. Clinical differentiation between giant cell (temporal) arteritis and Takayasu's arteritis. J. Rheumatol. 1996;23:106–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morreale M., Marchione P., Giacomini P., Pontecorvo S., Marianetti M., Vento C., Tinelli E., Francia A. Neurological involvement in primary Sjogren syndrome: a focus on central nervous system. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nagahiro S., Mantani A., Yamada K., Ushio Y. Multiple cerebral arterial occlusions in a young patient with Sjogren's syndrome: case report. Neurosurgery. 1996;38:592–595. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199603000-00037. ; discussion 595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nagata T., Hosoyama S., Shida N., Ohori N. [A case of sjogren's syndrome with multiple stenoses of the cerebral arteries and transient neurological symptoms and Signs] Brain Nerve. 2018;70:1389–1396. doi: 10.11477/mf.1416201198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oxholm P., Winther K., Manthorpe R. Platelet function in patients with primary Sjogren's syndrome. Acta Med. Scand. 1986;219:85–90. doi: 10.1111/j.0954-6820.1986.tb03280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oxholm P., Winther K., Manthorpe R. Platelets in blood and salivary glands of patients with primary Sjogren's syndrome. Scand. J. Rheumatol. Suppl. 1986;61:170–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pugh D., Karabayas M., Basu N., Cid M.C., Goel R., Goodyear C.S., Grayson P.C., McAdoo S.P., Mason J.C., Owen C., Weyand C.M., Youngstein T., Dhaun N. Large-vessel vasculitis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2022;7:93. doi: 10.1038/s41572-021-00327-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Qin B., Wang J., Yang Z., Yang M., Ma N., Huang F., Zhong R. Epidemiology of primary Sjogren's syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2015;74:1983–1989. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saadoun D., Vautier M., Cacoub P. Medium- and large-vessel vasculitis. Circulation. 2021;143:267–282. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.046657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sakata H., Fujimura M., Sato K., Shimizu H., Tominaga T. Efficacy of extracranial-intracranial bypass for progressive middle cerebral artery occlusion associated with active Sjogren's syndrome: case report. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. : the official journal of National Stroke Association. 2014;23:e399–e402. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2014.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Santos C.S., Salgueiro R.R., Morales C.M., Castro C.A., Alvarez E.D. Risk factors for cardiovascular disease in primary Sjogren's syndrome (pSS): a 20-year follow-up study. Clin. Rheumatol. 2023;42:3021–3031. doi: 10.1007/s10067-023-06686-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Scofield R.H. Vasculitis in sjogren's syndrome. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 2011;13:482–488. doi: 10.1007/s11926-011-0207-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shindo T., Ito M., Sugiyama T., Okuyama T., Kono M., Atsumi T., Fujimura M. Diagnostic value of vessel wall imaging to determine the timing of extracranial-intracranial bypass for moyamoya syndrome associated with active sjogren's syndrome: a case report. J. Neurol. Surg. Cent. Eur. Neurosurg. 2022 doi: 10.1055/a-1832-3269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Swartz R.H., Bhuta S.S., Farb R.I., Agid R., Willinsky R.A., Terbrugge K.G., Butany J., Wasserman B.A., Johnstone D.M., Silver F.L., Mikulis D.J. Intracranial arterial wall imaging using high-resolution 3-tesla contrast-enhanced MRI. Neurology. 2009;72:627–634. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000342470.69739.b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tektonidou M.G. Cardiovascular disease risk in antiphospholipid syndrome: thrombo-inflammation and atherothrombosis. J. Autoimmun. 2022;128 doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2022.102813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tincani A., Andreoli L., Cavazzana I., Doria A., Favero M., Fenini M.G., Franceschini F., Lojacono A., Nascimbeni G., Santoro A., Semeraro F., Toniati P., Shoenfeld Y. Novel aspects of Sjogren's syndrome in 2012. BMC Med. 2013;11:93. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Unnikrishnan G., Hiremath N., Chandrasekharan K., Sreedharan S.E., Sylaja P.N. Cerebral large-vessel vasculitis in sjogren's syndrome: utility of high-resolution magnetic resonance vessel wall imaging. J. Clin. Neurol. 2018;14:588–590. doi: 10.3988/jcn.2018.14.4.588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wan Y., Chen H.C., Lee C.Y., Lin H.Y., Nien C.W. Acute visual loss as the first ocular symptom in a Sjogren's syndrome patient with bilateral common carotid artery occlusion: a case report. BMC Ophthalmol. 2021;21:409. doi: 10.1186/s12886-021-02177-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.