Abstract

Sclerosing stromal tumors are a rare type of ovarian tumor in the category of sex cord stromal tumors, which arise from the ovarian connective tissue. This report concerns a case of a sclerosing stromal tumor in a 19-year-old nulliparous woman who presented with the chief complaints of menstrual irregularities and dyspareunia. Preoperative imaging revealed a complex right adnexal mass with blood flow and without associated ascites. Tumor markers were all normal except lactate dehydrogenase, which was elevated. The elevated lactate dehydrogenase, in combination with patient age and menstrual irregularities, initially misdirected the clinicians toward suspicion for dysgerminoma or other malignant germ cell tumor of the ovary. Clinicians should beware of excluding the diagnosis of sex cord stromal tumor on the differential in a young person with an adnexal mass and elevated lactate dehydrogenase.

Keywords: Sclerosing stromal tumor, Adnexal mass, Lactate dehydrogenase, Tumor marker, Case report

Highlights

-

•

Sex cord stromal tumors usually present in the second or third decade.

-

•

Symptoms may include pelvic pain and menstrual irregularities.

-

•

An elevated level of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) does not exclude the diagnosis of sclerosing stromal tumor.

-

•

Rare tumor types can be easily neglected in the differential.

1. Introduction

Sclerosing stromal tumors (SST) of the ovary, first described in 1973, [1] are a rare ovarian tumor accounting for <5% of sex cord stromal tumors, [2] which themselves account for only 7% of ovarian tumors. [3] Sclerosing stromal tumors usually present in the second or third decade, [1,4] with 80% presenting at <30 years of age. [5] The most common presentation of sclerosing stromal tumors are menstrual irregularities and pelvic pain. [1] The tumors are mostly unilateral, hormonally inactive, and present in the absence of ascites. [1,2] Surgery is considered the definitive treatment and is usually curative. [1] This is a report of a case of sclerosing stromal tumor remarkable for elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH). To the authors' knowledge, elevated LDH levels have not been reported in sclerosing stromal tumors. [1,2,4], [[6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13]] The combination of patient age, irregular vaginal bleeding and elevated LDH misdirected the clinicians toward suspicion for malignant ovarian germ cell tumor, which commonly has this cluster of findings, including elevated serum LDH. [14]

2. Case Presentation

A 19-year-old nulligravida woman initially presented to her primary care physician due to 3 months of daily vaginal bleeding and dyspareunia. The patient had no history of surgeries. Menarche was at 12 years old and she had been taking combined oral contraceptive pills until two months prior to symptom onset. Family history was negative for ovarian or other gynecological cancer. Transvaginal ultrasound revealed a 5.8 × 5.6 × 4.3 cm hypoechoic right adnexal mass with blood flow to the mass concerning for malignancy (Fig. 1A). The endometrium measured 5.7 mm (within normal limits). The left ovary appeared normal. Blood work revealed a markedly elevated serum LDH at 403 U/L. HCG, CA 125, and remaining tumor markers were within normal limits (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

(A) Right adnexa on transvaginal ultrasound showing large hypoechoic solid mass. (B) Coronal CT image of right adnexal mass showing heterogenous, lobular, solid mass. (C) Axial CT image of right adnexal mass.

Table 1.

Tumor markers prior to surgery and after surgery.

| Lab Value | Pre-operative | Post-operative |

|---|---|---|

| LDH | 403 U/L | 158 U/L |

| AFP | < 2.0 ng/mL | |

| CA 19.9 | 17 U/mL | |

| CEA | 0.9 ng/mL | |

| CA-125 | 15.5 U/mL | |

| Inhibin B | 77 pg/mL | |

| HCG | < 1 IU/L |

The patient was referred to gynecologic oncology. An office endometrial biopsy demonstrated proliferative endometrium with extensive tubal metaplasia as well as glandular and stromal breakdown. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) re-demonstrated a 5.5 × 4.8 × 5.6 cm heterogenous, lobular, solid mass within the right pelvis (Fig. 1B and C) with no normal adjacent right ovary visualized. There was a small amount of fluid around the mass but no free fluid within the pelvis. No significant lymphadenopathy was visualized. There was no evidence of metastatic disease within the chest, abdomen, or pelvis. Differential diagnosis included benign or malignant germ cell, sex cord stromal or epithelial ovarian tumors, with malignant germ cell tumor, specifically dysgerminoma, highest on the differential given the patient age, irregular vaginal bleeding, unilateral lesion, fairly rapid onset of symptoms, and elevated LDH. Surgical excision of the right adnexal mass was recommended for definitive diagnosis and treatment.

Pelvic examination under anesthesia revealed a mobile, smooth, solid mass palpable in the posterior cul-de-sac. Diagnostic laparoscopy demonstrated an enlarged right ovary with an associated solid mass. The bilateral fallopian tubes, uterus, and left ovary were normal in appearance. The bilateral hemidiaphragms were free of implants. Pelvic washings were collected and sent for cytologic examination. Right salpingo-oophorectomy was performed via vertical midline laparotomy and the right ovary with associated mass and fallopian tube were sent for frozen section. While awaiting frozen section results, pelvic and para-aortic lymph nodes were palpated as were the liver and diaphragm with no lymphadenopathy or metastatic disease identified.

Gross examination of the mass (Fig. 2) revealed a 100 g, 7.5 × 6.5 × 5.6 cm, tan-pink, smooth, and glistening solid ovary. Serial sectioning revealed a variegated golden yellow to tan, solid cut surface with a firm to focally rubbery consistency. Frozen section suggested a benign spindle-cell lesion, favoring fibroma or fibrothecoma. Thus, no further excisional procedure was indicated, and the abdomen was closed. The patient was observed overnight and discharged home the following day without complication.

Fig. 2.

Gross pathology specimen of right tubo-ovarian complex.

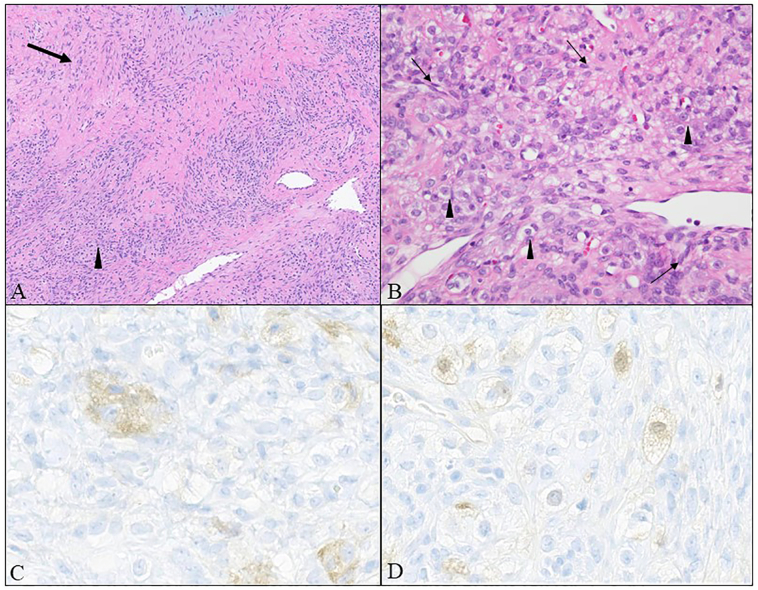

The final diagnosis was a sclerosing stromal cell tumor. Sections showed hypercellular spindled cells in a pseudo-lobular architecture alternating with hypocellular areas, vessels in a staghorn pattern, and interspersed luteinized (Fig. 3). Luteinized cells were faintly reactive with inhibin and calretinin while negative for epithelial and germ cell antigen markers. Cytology from pelvic washings was negative for malignant cells.

Fig. 3.

(A) Sclerosing stromal tumor with admixed hypercellular (arrowhead) and hypocellular (arrow) areas as well as “staghorn-like” vessels (hematoxylin and eosin, 100×). (B) Hypercellular areas with fibromatous spindle cells (arrow) interspersed with lutein cells (arrowhead) distinguished by clear cytoplasm and prominent nucleoli (hematoxylin and eosin, 400×). (C) Lutein cells show reactivity for inhibin. (D) Lutein cells show reactivity for calretinin (400×).

At the patient's two-week postoperative visit, her LDH had returned to normal, her wound was healing well, and she had no complaints. She was instructed to resume her regular gynecologic care with no further oncology follow-up indicated.

3. Discussion

Sclerosing stromal tumors of the ovary were originally described by Chalvardjian and Scully in 1973 [1] and belong to the family of ovarian sex cord stromal tumors (SCSTs), which arise from the supporting and connective tissue of the ovary. [1] Additional tumors in this category include but are not limited to fibromas, thecomas, fibrothecomas, Leydig cell and other steroid cell tumors, granola cell tumors (adult and juvenile), Sertoli and Sertoli-Leydig cell tumors, and gynandroblastoma. While SCSTs overall can present at any age range, the average age of presentation for SSTs is 27, and they most commonly present in the second and third decade of life. [1,4]

Clinical presentation of SCST is variable. The most common presenting symptoms of SSTs include menstrual irregularities [1,2,6,10,12,13] and pelvic pain. [8,10] SSTs typically present in the absence of ascites, although there have been cases associated with Meigs syndrome. [1,2,8,10,11] SSTs are generally hormonally inactive, unlike fibromas and thecomas. There has been as least one study in which a SST presented with elevated estradiol levels. [6] Several studies have reported an association with elevated CA-125, but in many cases CA-125 is normal. [2], [[9], [10], [11]] One other case in the literature describes a sclerosing stromal tumor with associated elevated serum LDH that normalized after surgical excision. [15] In the case described here, the menstrual irregularities, patient age, and elevated LDH were a red herring for dysgerminoma or other malignant germ cell tumor which often arise in adolescents and young adult women. Dysgerminomas contain syncytiotrophoblastic giant cells that produce placental alkaline phosphatase and LDH. Additionally, LDH is a laboratory marker of hemolysis or tissue destruction. High serum LDH is associated with poor prognosis and negative therapeutic outcome in many cancer types. [16]

On imaging, SST can appear as an adnexal mass with multilocular cystic components and thickened septa. [8] SSTs are usually unilateral. [1,9] The gross appearance of SSTs is not particularly distinct. They range from 1 cm to 31 cm, with a mean diameter of 8 cm. Tumors are usually well-circumscribed [8] and solid but can have both solid and cystic components; [7] cysts may be single or multiple and contain mucoid or serous fluid. [1] Calcifications may be present focally. [1,9]

Microscopically, SSTs are well demarcated and surrounded by fibrous tissue. [7] The tumors are characterized by cellular areas arranged in pseudolobules that are separated by hypocellular, edematous, or collagenous areas and thin-walled blood vessels that resemble those seen in hemangiopericytomas (“hemangiopericytoma-like vasculature”). [7,8] The cellular areas are composed of two populations of cells: luteinized theca-like cells with vacuolated cytoplasm and round nuclei; and fibroblast-like spindle cells with elongated nuclei. The cellular areas have a propensity for sclerosis. On high magnification, nuclei can be round or spindle-shaped, sometimes vesicular with prominent nucleoli, dark and shrunken, or binucleate. [1] Mitoses are rare. [1,7] Signet ring-like cells are occasionally present. [1,7,9] In one example of a virilizing case, steroidogenic cells were observed. [17]

Morphologic and clinical features of SST usually are sufficiently distinct to make the diagnosis; however, immunostains may be helpful. Vimentin is diffusely positive. The fibroblast-like spindle cells stain with strong intensity for smooth muscle actin and desmin. The vacuolated theca-like cells stain positively for inhibin-alpha and calretinin, show variable staining for CD99, and are negative for smooth muscle actin and desmin. Sclerosing stromal tumor can show positivity for WT1 and can be weakly positive for C-kit and melan-A. [18], [19] Sclerosing stromal tumor stains negatively for cytokeratins and EMA. [19].

The differential diagnosis on pathologic examination includes other sex cord stromal tumors such as fibromas, thecomas, and juvenile granulosa cell tumors as well as Krukenberg tumors and dysgerminoma (especially those with distinct fibrosis). The distinction between these can generally be made based on morphology and with the aid of immunohistochemical stains.

Sclerosing stromal tumors almost always behave in a benign fashion. [1] The standard treatment is surgical resection with curative intent. No recurrences after unilateral oophorectomy have been published to date. [8] Although SSTs are usually hormonally inactive, several cases have noted that active tumors produce estrogenic and androgenic hormones which are responsible for irregular menses, precocious puberty, virilization, amenorrhea, and infertility. Surgical resection of the tumor usually results in normalization of elevated hormone levels and resumption of physiologic menstrual/reproductive function. [8]

4. Conclusion

In conclusion, this patient's age at presentation, tumor unilaterality, absence of ascites, irregular bleeding and normal CA-125 were all characteristic of sclerosing stromal tumor; however, her elevated serum LDH led the care team to suspect a dysgerminoma or other germ cell tumor. Clinical presentation, imaging findings and tumor markers all contribute to including SST in the differential diagnosis, but surgical resection with pathologic evaluation is the only way to achieve definitive diagnosis. The significance of LDH in the setting of SST is unclear and warrants further investigation.

Acknowledgments

Contributors

Kelly Devlin contributed to patient care, acquiring and interpreting data, undertaking the literature review, and drafting the manuscript.

Alexander Gross contributed to analysis and interpretation of pathology, assisting with the literature review and drafting the manuscript sections related to pathology, and revising the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Melina Flanagan contributed to analysis and interpretation of pathology, conception of the case report, and revising the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Krista Pfaendler contributed to patient care, conception of the case report, acquiring and interpreting data, and revising the manuscript for important intellectual content.

All authors approved the final submitted manuscript.

Funding

This work did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Patient consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and the accompanying images.

Provenance and peer review

This article was not commissioned and was peer reviewed.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the patient, who agreed to allow us to publish the clinical data. The authors would also like to thank Ariel Cohen, MD, for assistance formatting references for the publication.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this case report.

Contributor Information

Kelly Devlin, Email: kdevlin1@hsc.wvu.edu.

Alexander Gross, Email: alexander.gross@vumc.org.

Melina Flanagan, Email: mflanagan@hsc.wvu.edu.

Krista Pfaendler, Email: krista.pfaendler@hsc.wvu.edu.

References

- 1.Chalvardjian A., Scully R.E. Sclerosing stromal tumors of the ovary, (in eng) Cancer. Mar 1973;31(3):664–670. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197303)31:3<664::aid-cncr2820310327>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khanna M., Khanna A., Manjari M. Sclerosing stromal tumor of ovary: a case report, (in eng) Case Rep. Pathol. 2012;2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/592836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Horta M., Cunha T.M. Sex cord-stromal tumors of the ovary: a comprehensive review and update for radiologists, (in eng) Diagn. Interv. Radiol. 2015;21(4):277–286. doi: 10.5152/dir.2015.34414. Jul-Aug 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Young R.H. Ovarian sex cord-stromal tumours and their mimics, (in eng) Pathology. Jan 2018;50(1):5–15. doi: 10.1016/j.pathol.2017.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ismail S.M., Walker S.M. Bilateral virilizing sclerosing stromal tumours of the ovary in a pregnant woman with Gorlin’s syndrome: implications for pathogenesis of ovarian stromal neoplasms, (in eng) Histopathology. Aug 1990;17(2):159–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1990.tb00688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao Z., Yan L., Lv H., Liu H., Rong F. Sclerosing stromal tumor of the ovary in a postmenopausal woman with estrogen excess: a case report, (in eng) Medicine (Baltimore) Nov 2019;98(47) doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000018171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zekioglu O., Ozdemir N., Terek C., Ozsaran A., Dikmen Y. Clinicopathological and immunohistochemical analysis of sclerosing stromal tumours of the ovary, (in eng) Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. Dec 2010;282(6):671–676. doi: 10.1007/s00404-010-1373-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ozdemir O., Sarı M.E., Sen E., Kurt A., Ileri A.B., Atalay C.R. Sclerosing stromal tumour of the ovary: a case report and the review of literature, (in eng) Niger. Med. J. Sep 2014;55(5):432–437. doi: 10.4103/0300-1652.140391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marelli G., Carinelli S., Mariani A., Frigerio L., Ferrari A. Sclerosing stromal tumor of the ovary. Report of eight cases and review of the literature, (in eng) Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. Jan 1998;76(1):85–89. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(97)00151-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khan S., Singh V., Khan I.D., Panda S. Sclerosing stromal cell tumor of ovary, (in eng) Med. J. Armed Forces India. Oct 2018;74(4):386–389. doi: 10.1016/j.mjafi.2017.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jung N.H., Kim T., Kim H.J., Lee K.W., Lee N.W., Lee E.S. Ovarian sclerosing stromal tumor presenting as Meigs’ syndrome with elevated CA-125, (in eng) J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. Dec 2006;32(6):619–622. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2006.00466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Damajanov I., Drobnjak P., Grizelj V., Longhino N. “Sclerosing stromal tumor of the ovary: a hormonal and ultrastructural analysis,” (in eng) Obstet. Gynecol. Jun 1975;45(6):675–679. doi: 10.1097/00006250-197506000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Atram M., Anshu S. Sharma, Gangane N. Sclerosing stromal tumor of the ovary, (in eng) Obstet. Gynecol. Sci. Sep 2014;57(5):405–408. doi: 10.5468/ogs.2014.57.5.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.PS P., et al. Serum lactate dehydrogenase levels in malignant germ cell tumors of ovary. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer. 1996;6:328–332. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Belgaumi S.M., Turk K.K., Arshad S., Khan M.A.M. Ovarian sclerosing stromal tumor uncommonly presenting in an infant. J Pediatr Surg Case Rep. 2022;84 doi: 10.1016/j.epsc.2022.102347. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jurisic V., Radenkovic S., Konjevic G. The actual role of LDH as tumor marker, biochemical and clinical aspects, (in eng) Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2015;867:115–124. doi: 10.1007/978-94-017-7215-0_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boussaïd K., et al. Virilizing sclerosing-stromal tumor of the ovary in a young woman with McCune Albright syndrome: clinical, pathological, and immunohistochemical studies, (in eng) J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. Feb 2013;98(2):E314–E320. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-3551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vander Heiden M.G., Cantley L.C., Thompson C.B. Understanding the Warburg effect: the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation, (in eng) Science. May 2009;324(5930):1029–1033. doi: 10.1126/science.1160809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaygusuz E.I., Cesur S., Cetiner H., Yavuz H., Koc N. Sclerosing stromal tumour in young women: clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical spectrum, (in eng) J. Clin. Diagn. Res. Sep 2013;7(9):1932–1935. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2013/6031.3373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]