Abstract

BaqA is a raw starch degrading α-amylase produced by the marine bacterium Bacillus aquimaris MKSC 6.2, associated with soft corals. This α-amylase belongs to a new subfamily Glycoside Hydrolases (GH) 13_45 which has several unique characteristics, namely, a pair of tryptophan residues Trp201 and Trp202, a distinct LPDIx signature in the Conserved Sequence Region-V (CSR-V), and an elongated C-terminus containing five aromatic residues. The research aims to investigate physicochemical, kinetics, and biochemical properties of BaqA. In this study, the full-length enzyme (BaqA) and a truncated form of BaqA (designated as BaqAΔC), lacking the C-terminal 34 amino acids were constructed and expressed in Escherichia coli ArcticExpress (DE3). BaqA formed inclusion bodies, while BaqAΔC was produced as a soluble protein. Purified and refolded BaqA exhibited a catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km) of 53.1 ± 6.3 mL mg−1 s−1 at 40 °C and pH 7.5, whereas the purified BaqAΔC displayed kcat/Km of 11.4 ± 1.3 mL mg−1 s−1 under the optimum condition of 50 °C and pH 6.5. Moreover, BaqAΔC showed a slight reduction in the binding affinity towards sago granules. Interestingly, BaqAΔC displayed robust stability and halotolerant properties compared to BaqA. BaqAΔC maintained 50 % amylolytic activity for up to 6 h, whereas BaqA lost over 50 % of its activity within 90 min. Furthermore, BaqAΔC showed a remarkable increase in amylolytic activity upon the addition of NaCl, with an optimum concentration of 0.5 M. Even at a high salt concentration (1.5 M NaCl), BaqAΔC retained over 50 % of its residual activity. Taken together, its solubility, amylolytic activity, stability, ability to degrade raw starch, and moderate halotolerance make BaqAΔC a promising candidate for various starch processing industries.

Keywords: α-Amylase, BaqA, BaqΔC, C-terminal region, Moderately halotolerant, Raw starch

Highlights

-

•

Full-length BaqA requires refolding to become active, while BaqA∆C is expressed as a soluble protein.

-

•

BaqA∆C has lower catalytic efficiency toward soluble starch and reduced binding affinity to starch granules compared to BaqA.

-

•

BaqA∆C demonstrates higher stability and halotolerance than BaqA.

1. Introduction

Modification of starch using starch hydrolyzing enzymes increases its economic value. The current modified starch market is estimated to be valued at USD 11.1 billion and this value is projected to reach an amount of USD 17.1 billion in 2030 [1]. Modified starch is widely used by industries for the manufacture of various products, such as food and beverages, textiles, paper, pharmaceuticals, and bioethanol. α-Amylase (1,4-α-D-glucan-glucanohydrolase; EC 3.2.1.1) is one of the starch hydrolyzing enzymes that catalyzes the cleavage of the internal α-1,4-glycosidic bond of starch and related α-glucans – i.e. as an endohydrolase – producing various maltooligosaccharides including dextrin, but in some case also maltose and even glucose [2,3].

Starch processing industries require robust α-amylases such as those that have halophilic or halotolerant properties. Halophilic α-amylases are produced from microorganisms found in hypersaline environments with NaCl or KCl concentrations more than 2.5 M, while halotolerant α-amylases are generally produced by microorganism living in lower salt concentration environments [4,5]. Compared to halophilic enzymes, halotolerant α-amylases are more preferable since they do not require high concentration of salt and hence their use will lead to a lower modified starch production cost. Until now, there is rather only a handful of reports on halotolerant α-amylases, focused just on their biochemical properties [[6], [7], [8]] or in some cases delivering also their amino acid sequence [[9], [10], [11]].

In the sequence-based classification of glycoside hydrolases (GHs) in the Carbohydrate-Active enZymes database (CAZy) [12,13], most typical α-amylases belong to the family GH13 representing the largest α-amylase family [3]; three more families GH57, GH119 and GH126 being known as additional and smaller α-amylase CAZy families [14]. The fundamental characteristics of the family GH13 are as follows: (i) the (β/α)8-barrel fold (the so-called Triose Posphate Isomerase-barrel, TIM-barrel); (ii) the triad of catalytic residues – aspartic acid (catalytic nucleophile), glutamic acid (proton donor) and aspartic acid (transition-state stabilizer) located at the TIM-barrel strands β4, β5 and β7, respectively; (iii) the retaining reaction mechanism; and (iv) the presence of 4 up to 7 conserved regions (CSRs) [3,[15], [16], [17], [18]]. Currently, according to the CAZy update of May 12, 2024, the family GH13 counts more than 182 thousand members [13,14]. In 2006, the family has been officially divided by CAZy curators into 35 GH13 subfamilies [19]; until now, the last subfamily GH13_46 being created around the cyclomaltodextrinase from Flavobacterium sp. No. 192 [20]. With regard to the above-mentioned halotolerant and halophilic α-amylases, the subfamily GH13_43 established for the α-amylases from haloarcheaons [21] should be of interest. On the other hand, the individual halotolerant/halophilic bacterial α-amylases are rather scattered in different GH subfamilies, for example, in GH13_5 – E. coli JM109 [22] and Halothermothrix orenii AmyB [23], GH13_27 – Alteromonas macleodii [10], GH13_28 – Bacillus sp. FP-133 [11], GH13_32 – Halomonas meridiana [9], Marinobacter algicola [5] and Kocuria varians [24], and GH13_36 – H. orenii AmyA [25].

This paper is subjected to fully investigate properties of the α-amylase BaqA that was originally isolated from a soft coral-associated marine bacterium B. aquimaris MKSC 6.2 [26]. Its amino acid sequence indicated a new feature suitable for creating a novel GH13 subfamily [27]. The subsequent detailed in silico study identified, indeed, several characteristics of the emerging group, namely a pair of tryptophan residues Trp201 and Trp202 (BaqA numbering) in the helix α3 of the catalytic TIM-barrel, the LPDlx signature in the CSR-V and a conserved aromatic motif at the C-terminus of the protein [28]. All these unique features were convincingly found also in several α-amylases from strains of Anoxybacillus sp. – ASKA and ADTA [29] and Geobacillus thermoleovorans – Pizzo [30], GTA [31], and Gt-amyII [32]. Remarkably, the same characteristics were later identified in an amylolytic enzyme BmaN1 from Bacillus megaterium NL3 that, in addition, possesses an aberrant catalytic machinery [33]. Based on the accumulated evidences [26,28,33], the entire novel group, represented by the α-amylase BaqA from B. aquimaris MKSC 6.2, has recently been assigned its own GH13 subfamily number GH13_45 [13]. The present study thus delivers physicochemical properties, salt tolerance and stability, kinetic parameter towards soluble starch, and raw starch adsorptivity of full length BaqA and truncated BaqAΔC without the C-terminal 34 amino acid residues. This study sheds light on the potential of BaqAΔC as a moderately salt tolerant enzyme in starch processing industry.

2. Methods

2.1. Strains, plasmids and chemicals

The recombinant plasmid pET30-baqA was obtained from the plasmid collection at Biochemistry and Biomolecular Engineering Research Division, Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences, Institut Teknologi Bandung. E. coli TOP10F’ (Thermo Scientific, USA) and E. coli ArcticExpress (DE3) (Stratagene, USA) were used for plasmid propagation and gene expression, respectively. PfuTurbo polymerase and Dpn I (Thermo Scientific, USA) were used for routine PCR and molecular cloning experiments. Presto™ Mini Plasmid Kit (Geneaid, Taiwan) was used for plasmid isolation. A 1 kb DNA ladder and protein marker (PM1500) were obtained from SMOBIO Technology, Taiwan. Nickel-NTA agarose resin (Qiagen, Netherlands) was used for BaqAΔC purification. Solution kits for determining protein concentration and performing protein gel electrophoresis were obtained from HIMEDIA, India. Soluble starches for activity assay were obtained from Merck, USA.

2.2. C-terminal deletion of BaqA

The truncated baqA gene without the C-terminal 34 amino acid residues (baqAΔC), was constructed through site-directed mutagenesis. Recombinant plasmid pET30-baqA [27] was used as a DNA template and baqA-F (5′-CTGCTTAAAGCCAAAAGTTAACTGAACATCCCATATTTATCAGC-3′) and baqA-R (5′-GCTGATAAATATGGGATGTTCAGTTAACTTTTGGCTTTAAGCAG-3′) were used as the primers. Forward and reverse primers carried EcoRI and EcoRV restriction sites respectively. To remove the DNA template, a solution containing PCR-amplified target DNA was digested using Dpn I at 37 °C for 2 h. The plasmid was then used to transform the E. coli TOP10F' competent cells. Following this, the recombinant plasmid was isolated and analyzed by sequencing employing the dideoxy Sanger method (Macrogen, Singapore).

2.3. Expression and purification BaqA and BaqAΔC

The E. coli ArcticExpress (DE3) was transformed using the recombinant plasmid pET30-baqA and pET30-baqAΔC via the heat shock method. The transformants were grown in Luria Bertani (LB) medium (0.5 % yeast extract, 1 % tripton, and 1 % NaCl) supplemented with 50 μg/mL kanamycin and incubated in an incubator shaker at 37 °C with an aeration rate of 150 rpm for 12−16 h. The culture (1.5 % v/v) was transferred into 100 mL of fresh LB medium containing kanamycin (50 g/mL) as a selection marker. The culture was then incubated until the cell density at 600 nm reached 0.6−0.8. Protein production was then induced by the addition of 0.5 and 0.25 mM isopropyl-β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) for BaqA and BaqAΔC, respectively. Both culture were incubated for 24 h at 10 °C with an aeration rate of 150 rpm. Following this, the cells were harvested by centrifugation at 6,000 rpm for 15 min and 4 °C. The cells were washed with 5 mL of ddH2O and then centrifuged for 10 min and 4 °C at 6,000 rpm.

E. coli ArcticExpress (DE3)/BaqA cells were resuspended in lysis buffer (20 mM tris-Cl pH 7, 150 mM NaCl and 20 mM imidazole) and E. coli ArcticExpress (DE3)/BaqAΔC cells were resuspended in lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES pH 8, 500 mM NaCl, and 10 mM imidazole). All of lysis buffers contained protease inhibitors cocktail in a ratio of 1:4 (w/v) and cells were disrupted by sonication at 4 °C with a vibration frequency of 50 kHz for 15.5 min with operating conditions of 30 s “on” and 30 s “off”. The cell debris was precipitated by centrifugation at 12,000×g for 15 min and 4 °C. The protein profile was then analyzed using SDS-PAGE, and the protein concentration was determined using the Bradford method.

The protein purification was performed using one-step purification column affinity chromatography. BaqA was purified under denaturing condition. The insoluble BaqA was subsequently refolded in buffer A (20 mM tris-Cl, pH 8, 500 mM NaCl) with a urea gradient concentration of 6, 4, 2, and 1 M at room temperature. Following this, the refolded BaqA was washed in buffer A containing imidazole 50 mM and 100 mM, sequentially, at 4 °C. The bound BaqA was then eluted from Ni-NTA agarose using buffer A containing 250 mM imidazole. The eluate was dialyzed against buffer A. BaqA was subsequently analyzed using SDS-PAGE, and the protein concentration was determined using the Bradford assay (Bio-Rad, USA). The purified BaqA was used for biochemical characterizations.

BaqAΔC was purified under native condition. The BaqAΔC protein extract was mixed with the resin slurry and mixed gently at 4 °C using a rotator for 3 h. Unbound materials are collected as a flow-through fraction. The resin was then washed with 15 CVs of wash buffer 1 (50 mM HEPES pH 8, 500 mM NaCl, and 25 mM imidazole) and five CVs of wash buffer 2 (50 mM HEPES pH 8, 500 mM NaCl, and 50 mM imidazole). The bound BaqAΔC was eluted from Ni-NTA resin using two CVs of elution buffer 1 (50 mM HEPES pH 8, 500 mM NaCl, and 75 mM imidazole) and two CVs of elution buffer 2 (50 mM HEPES pH 8, 500 mM NaCl, and 100 mM imidazole). The purified protein was concentrated using Vivaspin® Turbo 4 Ultrafiltration with 10 kDa molecular weight cut-off and buffer exchange to 50 mM HEPES pH 8 and 500 mM NaCl was performed to remove imidazole from the final protein preparation. The purified BaqAΔC was subjected to biochemical characterizations.

2.4. α-Amylase activity assay

The starch-hydrolyzing activity of BaqA and BaqAΔC was determined using the 3,5-dinitrosalicylic acid (DNS) method [34]. A mixture of 25 μL of the enzyme with 25 μL of 2 % (w/v) soluble starch in a universal buffer (25 mM MES pH 6.5, 50 mM malate and 50 mM tris) were incubated for 15 min at 50 °C. The reaction was then stopped by adding 50 μL of DNS solution (1 % (w/v), 20 % (v/v) 2 M NaOH, 30 % (w/v) KNa-tartaric). The homogeneous mixture was then heated for 10 min in a boiling water bath and diluted with ddH2O to a final volume of 1 mL. The absorbance of the reaction mixture was measured at a wavelength of 500 nm. The amount of reducing sugar produced was calculated based on a glucose standard curve. All reaction was measured in triplicates. One unit of enzyme activity was defined as the amount of enzyme required to release 1 μmol of glucose per minute under the assay condition.

2.5. Effect of pH, temperature, and salt concentration on the activity of BaqA and BaqAΔC

The effect of pH in the hydrolysis of soluble starch was determined using 2 % (w/v) soluble starch in universal buffers at various pH starting from pH 4 to 8.5. The assay mixtures for BaqA were incubated at 40 °C for 15 min and BaqAΔC were incubated at 50 °C for 15 min. The effect of temperature was measured by ranging the temperature of incubation starting from 25 °C to 80 °C. The salt effect was studied by varying the concentration of NaCl from 75 mM to 1,500 mM in a reaction mixture. Enzyme stability was determined by pre-incubating the enzyme at 50 °C for 30, 60, 90, 120, 240, and 360 min. The amount of reducing sugar was determined by the DNS method.

2.6. Determination of kinetic parameters of BaqA and BaqAΔC

Kinetic parameters of BaqA and BaqAΔC were determined at the optimum conditions by ranging the concentration of soluble starch from 7.5 to 45 mg mL−1 in 50 mM universal buffer pH 6.5. Reducing sugar formed during the assay was measured following the DNS method described above. The kinetic parameter values (Vmax, kcat, Km, and kcat/Km) were obtained by fitting the initial reaction rate to the Michaelis-Menten equation. Fittings and calculations were performed using the GraphPad Prism 9.0 [35].

2.7. Raw starch adsorptivity of BaqA and BaqAΔC

Raw starch adsorptivity was determined by preincubated 6 various concentration (10−60 mg mL−1) of sago starch with BaqA or BaqAΔC to a final volume of 50 μL. The mixture was incubated with continues shaking at 150 rpm under 4 °C for 30 min. The enzyme bound in the supernatant was assessed after being centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C. The resulting values were plotted against the concentrations, and the data were analyzed with a one-site binding model using GraphPad Prism 9.0 [35]. The dissociation constant (Kd) was determined by applying the Langmuir adsorption isotherm to the fraction of bound enzyme, (Equation (1)), where B represents the fraction of bound enzyme, [S] is the starch granule concentration, and Bmax is the maximum binding capacity [36].

| (1) |

2.8. Bioinformatics analysis and model structure

The Alphafold2 and function prediction server [37] were used to generate three-dimensional structures of BaqA and BaqAΔC. All 3D structures were then visualized by Pymol [38]. The amino acid composition was carried out by Expasy ProtParam [39], while the solubility prediction for BaqA and BaqAΔC was performed using ccSOL [40].

3. Results

3.1. Construction and expression of BaqA and BaqAΔC

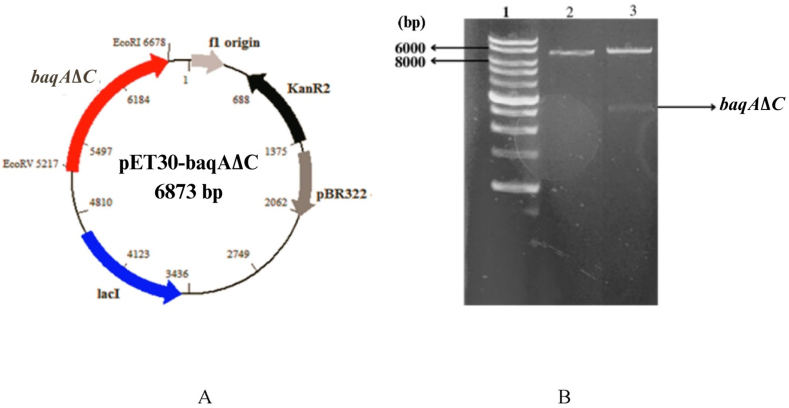

The multiple sequence alignment of amino acid residues of BaqA and several α-amylases (GTA, ADKA, and ASKA) revealed a segment of 34 hydrophobic residues at the C-terminus [31]. To delete this C-terminal region from BaqA during protein synthesis, Site-Directed Mutagenesis (SDM) was employed, where a stop codon was introduced to replace the codon for Glycine 479 in the pET30-baqA vector containing mature sequence of the full-length baqA open reading frame [26]. The resulting pET30-baqAΔC was verified through restriction analysis at the EcoRI and EcoRV sites, yielding DNA fragments of sizes 1461 bp and 5413 bp, corresponding to the baqAΔC gene fragment and the plasmid backbone, respectively (Fig. 1A and B). Nucleotide sequencing of baqAΔC confirmed the presence of the stop codon in the mutant gene.

Fig. 1.

The plasmid map of pET30-baqAΔC (A). The agarose electropherogram of pET30-baqAΔC (B). Lane 1: DNA Marker (bp); Lane 2: pET30-baqAΔC/EcoRI; Lane 3: pET30-baqAΔC/EcoRI/EcoRV.

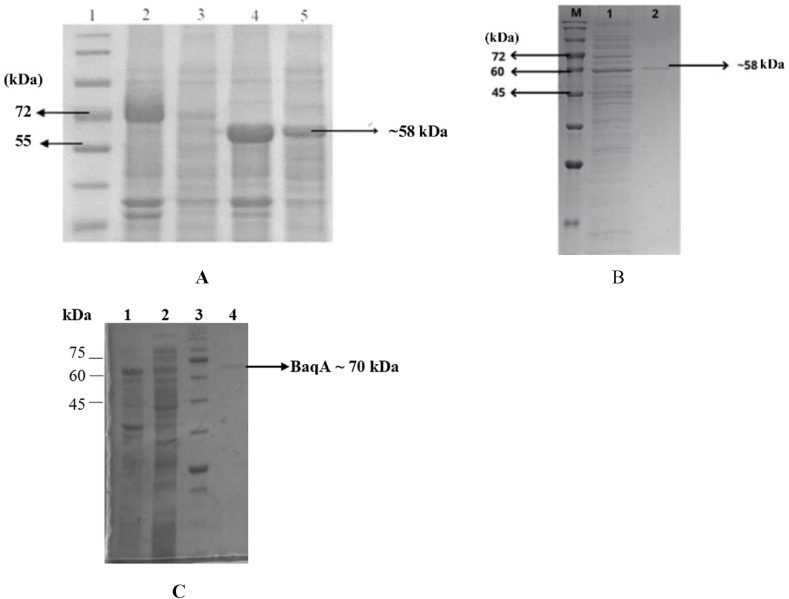

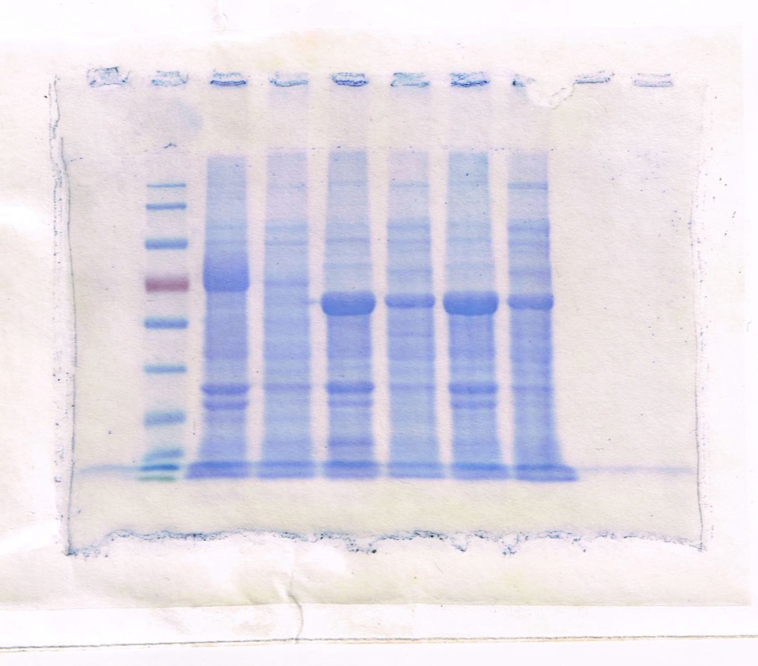

The recombinant plasmids pET30-baqA and pET30-baqAΔC were introduced into E. coli ArcticExpress (DE3). SDS-PAGE analysis showed that the full-length of BaqA (534 amino acids) was expressed as inclusion bodies, appearing at molecular weight of approximately 70 kDa (Fig. 2A, lane 2). However, BaqAΔC (500 amino acids) was found both as insoluble and soluble fractions, appearing around ∼58 kDa (Fig. 2A, lanes 4 and 5). These findings suggest that the removal of 34 residues in the C-terminal region of BaqA enhanced its solubility.

Fig. 2.

An SDS PAGE analysis of crude BaqA and BaqAΔC. (A), pure BaqAΔC (B) and pure BaqA (C)

(A) Lane 1: Protein Marker (kDa); Lane 2: debris of E. coli ArcticExpress (DE3)/pET30-baqA; Lane 3: crude of E. coli ArcticExpress (DE3)/pET30-baqA; Lane 4: debris of E. coli ArcticExpress (DE3)/pET30-baqAΔC; Lane 5: crude of E. coli ArcticExpress (DE3)/pET30-baqAΔC. (B) Lane M: protein marker (kDa); Lane 1: cellular protein from the crude extract of BaqAΔC; Lane 2: purified BaqAΔC. (C) Lane 1: inclusion body of BaqA; Lane 2: cellular protein from the crude extract of BaqA; Lane 3: protein molecular weight marker (kDa); Lane 4: purified of BaqA.

3.2. Purification and biochemical characterization of BaqA and BaqAΔC

The insoluble BaqA was purified under denaturing condition, while the soluble fraction of BaqAΔC was purified under native condition using Ni-NTA affinity column chromatography. Both enzymes were successfully purified, resulting in a single band as confirmed by SDS-PAGE analysis (Fig. 2B and C).

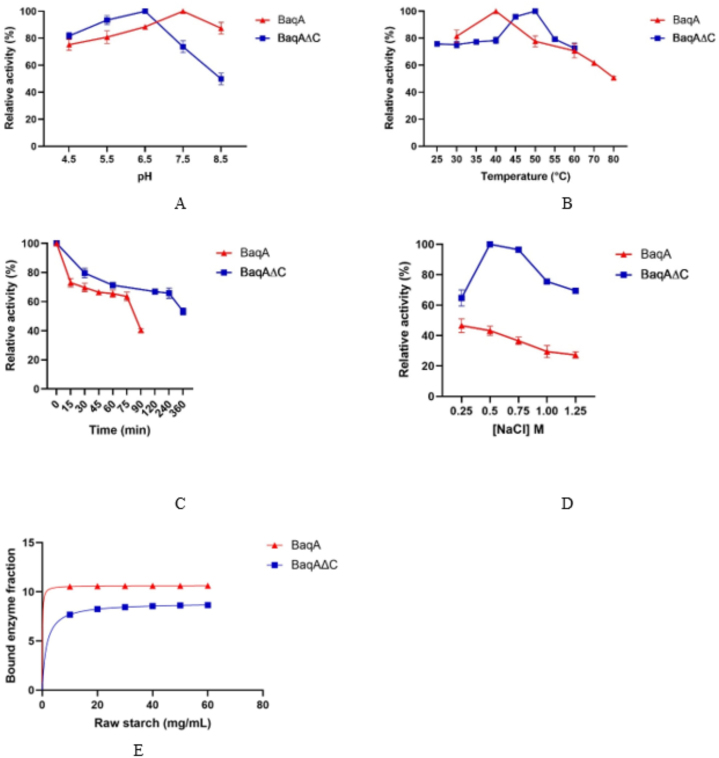

The effect of pH on the activity of both BaqA and BaqAΔC towards soluble starch was explored by varying the pH of the assay mixture from 4.5 to 8.5 (Fig. 3A). BaqA demonstrated its optimum activity at a pH of 7.5, whereas BaqAΔC exhibited optimal activity at a slight acidic pH of 6.5. The effect of temperature on the amylolytic activity of both BaqA and BaqAΔC was examined by conducting assays across temperatures ranging from 30 to 60 °C, with of 5 °C increments (Fig. 3B). BaqA showed an optimum activity at 40 °C, while BaqAΔC exhibited a higher optimal activity at 50 °C. Interestingly, both enzymes retained substantial activity around 75 %, across a moderate temperature range (Fig. 3B). The higher optimum temperature noted for BaqAΔC could be linked to its potentially enhanced structural stability when compared to BaqA. The stability assay revealed that after 6 h of incubation at 50 °C, BaqAΔC retains 50 % of its amylolytic activity, whereas BaqA exhibits a 60 % reduction in amylolytic activity after just 2 h of incubation at 40 °C (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

A profile of hydrolytic activity of BaqA and BaqAΔC towards soluble starch in different pH (A), temperature (B), enzyme stability over time (C), amylotic affinity in a various NaCl concentrations (D), and binding activity of BaqA and BaqAΔC to sago starch granules (E).

As BaqA originates from a marine bacterium, B. aquimaris MKSC 6.2, we investigated its salt tolerance in relation to enzyme activity. Our findings demonstrated that BaqAΔC has greater salt tolerance than BaqA. In the presence of 0.25 M NaCl, BaqAΔC exhibited a specific activity of 1.51 U/mg, which notably increased at a NaCl concentration of 0.5 M. Even at a moderate salt concentration of 1.5 M, BaqAΔC retained 50 % of its amylolytic activity. In contrast, the activity of BaqA decreased by up to 20 % at 0.25 M NaCl and continued to decrease to about 20 % at a NaCl concentration of 1.25 M (Fig. 3D). These results underscore the moderate halotolerant properties of BaqAΔC.

The kinetic parameters for BaqA and BaqAΔC were determined using soluble starch as a substrate under optimal pH and temperature conditions. The results indicated that both enzymes followed the Michaelis-Menten kinetic profile. The kinetic parameters for both enzymes are presented in Table 1. Refolded and purified BaqA exhibited a catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km) of 53.1 ± 6.3 mL mg−1 s−1 at 40 °C and pH 7.5, while purified BaqAΔC has a kcat/Km of 11.4 ± 1.3 mL mg−1 s−1 under the optimum condition of 50 °C and pH 6.5.

Table 1.

Kinetic parameters of BaqA and BaqAΔC towards soluble starch.

| BaqA | BaqAΔC | |

|---|---|---|

| Km (mg mL−1) | 9.46 ± 1.6 | 36.24 ± 8.0 |

| Vmax (μg min−1) | 498.6 ± 23.3 | 103.5 ± 5.3 |

| kcat (s−1) | 495.2 ± 23.2 | 412 ± 8.2 |

| kcat/Km (mL mg−1 s−1) | 53.1 ± 6.3 | 11.4 ± 1.3 |

3.3. Raw starch adsorptivity activity of BaqA and BaqAΔC

The adsorptivity of BaqA and BaqAΔC was measured using sago granule as a substrate, with Kd representing the dissociation constant between protein and substrates. Lower observed Kd values indicate a higher affinity of raw starch to the protein. BaqA was found to bind raw starch more strongly, indicated by its lower Kd value of 0.91 mg mL−1, compared to BaqAΔC, which has Kd of 1.51 mg mL−1. Moreover, BaqAΔC has lower starch saturation binding (Bmax = 8.89) than BaqA (Bmax = 10.63) (Fig. 3E). This difference might be due to the deletion of the C-terminal region of BaqA.

4. Discussion

BaqA along with α-amylases, ASKA and ADTA from Anoxybacillus strains SK3-4 and DT3-1, respectively, GTA from G. thermoleovorans CCB_US3_UF5, and Gt-amyII from G. thermoleovorans, belong to a newly identified subfamily GH13_45. This subfamily is characterized by a sequence of stretch of hydrophobic amino acids at their C-terminus [13,28]. The baqA gene without putative signal peptides had been expressed as an inclusion body and can be refolded to yield an active α-amylase [27]. In this study, a soluble truncated BaqA has been generated. Similarly, the other amylases were engineered as C-terminally truncated versions to facilitate detailed analyses. GTA without the C-terminal region was produced as a soluble protein and the crystal structure of this truncated GTA shows a compact amylase fold [31]. ASKA and ADTA were expressed as extracellular proteins using a pelB signal sequence in E. coli BL21(DE3) [29]. However, comparisons involving Gt-amyII are challenging since the truncated version (Gt-amyII-T) shows a significant reduction in molecular weight by 42 kDa after removing 113 amino acids from the C-terminus [32].

In this study, the BaqA and BaqAΔC were co-expressed with two chaperonins (Cpn10 and Cpn60) in E. coli ArcticExpress (DE3). BaqA could not fold properly despite the presence of two chaperonins, while the BaqAΔC was produced as a soluble protein. The solubility prediction performed by ccSOL showed that BaqAΔC had higher solubility (53 %) compared to that of BaqA with a solubility percentage of 46 % [40]. The increase in solubility of BaqAΔC could be caused by the deletion of 34 transmembrane amino acid residues (GLNIPYLSALAAVYVLFLLFIYLVWKRGRKNRKS) at the C-terminal region, which was predicted using Phobius transmembrane topology and signal peptide predictor [41]. These predictions are also supported by crystal structures of GTA and ASKA, which do not have 23 and 27 transmembrane amino acids, respectively, at their C-terminal region (Fig. 4A). Further analysis based on the structural model (Fig. 4B) showed that both structures of BaqA and BaqAΔC are highly similar. The deletion of 34 residues at the C-terminal region did not alter the overall structure and hence maintained the enzyme activity. The extended helix structures at the C-terminal of BaqA might be a major factor contributing to the insolubility of BaqA.

Fig. 4.

(A) Superimpose structures of α-amylases from GTA (blue with a PDB code of 4E2O), ASKA (yellow; 5A2A) and a generated structure of BaqAΔC (red). All of protein structures are aligned well with RMSDs of 0,79 Å for GTA-BaqAΔC and 0.59 Å for ASKA-BaqAΔC. (B) Superimpose structures of BaqA (light blue) and BaqAΔC (red). Structures of BaqA and BaqAΔC were generated using the Alphafold2 server. (https://colab.research.google.com/github/sokrypton/ColabFold/blob/main/AlphaFold2.ipynb). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

Both BaqA and BaqAΔC were active in a wide range of pH (4.5–8.5) with more than 70 % and 50 % amylolytic activity for BaqA and BaqAΔC, respectively at pH 8.5. A broad pH interval for starch hydrolysis was also found in BmaN2 spanning from a pH of 5–9 with an optimum pH of 6.0 [42]. However, the relative activity of BmaN2 was only about 60 % at pH 5 and 8 [42]. Similarly, ASKA and ADTA exhibited amylolytic activity higher than 60 % in the pH range of 5–10 [29] whereas AmyII from Haloarchaea maintained its activity only up to 30 % at pH 5.0 and 9.0 [43]. These results showed that BaqA and BaqAΔC were robust enzymes with respect to pH compared to other amylases from the same subfamily of GH13_45. It is also noteworthy that two of them exhibited 85 % starch hydrolyzing activity at a pH of 4.5, which is close to the pH of starch slurry, rendering this enzyme a suitable choice for starch processing.

BaqA has a lower optimum temperature compared to BaqAΔC, GTA and Gt-amyII [31,32]. Other amylases from the same GH13_45 subfamily, which are ASKA and ADTA, have an optimum temperature of 60 °C and they both have 80 % activity at 50 °C [29]. Compared to AmyI and AmyII which has only 23 % of its amylolytic activity at 60 °C [44], BaqAΔC retained higher activity at corresponding temperature. Furthermore, BaqAΔC demonstrates higher stability compared to BaqA (Fig. 3C). BaqAΔC is capable of maintaining its activity at over 50 % even after being incubated for 6 h at 50 °C. Therefore, truncation of the C-terminus not only enhances the solubility of the protein but also improves the stability of BaqAΔC.

Regarding to the halotolerant properties, BaqAΔC demonstrate halotolerant characteristic, while BaqA does not. In general, the halotolerant α-amylases have a high ratio of negatively charged amino acids (glutamic and aspartic acids), resulting in a negative charge surface environment and consequently maintaining its amylolytic activity in a broad range of salt concentrations [7,11,45]. Surface electrostatic potential analysis of BaqAΔC revealed the presence of a large number of negatively charged amino acids on the surface of the protein with a percentage of 31.5 % or a ratio of 76 Asp/Glu per 241 total surface amino acid residues. These negatively charged amino acids would allow the formation of a hydrated salt ion network resulting in better enzyme stabilization [46]. Furthermore, salt could also create a shielding effect against the repulsion of similarly charged amino acid residues on the protein's surface [7].

Deletion of the C-terminal affects the catalytic parameters of BaqA. BaqAΔC has higher Km value compared to BaqA. It was possible that the high Km of BaqAΔC was due to the deletion of the 34 amino acid residues at the C terminus. A similar high Km value has been observed in α-amylase from Geobacillus sp. IIPTN with Km value of 36 mg mL−1 for cassava starch [47]. However, GTA from G. thermoleovorans CCB US3 UF5, AmyF from Nesterenkonia sp. Strain F, BmaN2 from B. megaterium NL3, and AT23 from Anoxybacillus gonesis AT23 have relatively low Km values towards soluble starch with the value of 6.1, 5.8, 5.1, and 1.7 mg mL−1, respectively [31,42,48,49]. The kcat values of BaqA and BaqAΔC (Table 1) were quite similar to that of B. amyloliquefaciens, which is 450 s−1 [50]. The catalytic efficiency of BaqA (52.53 mL mg−1 s−1) was higher compared to that of BaqAΔC (11.4 mL mg−1 s−1) and AmyA from psychrophilic Pseudoalteromonas haloplanktis [7].

BaqA belongs to the group of raw starch degrading enzyme without starch binding domain [27]. In this study, we analyzed the ability of BaqA and BaqAΔC to adsorb to the raw starch by using sago starch as a model. The deletion of 34 amino acid residues from the C-terminus had a noticeable impact on the ability to adsorb raw sago starch. BaqAΔC showed a 1.7-fold decrease in binding affinity compared to the full-length BaqA (Fig. 3E). This indicates that the C-terminal region of BaqA likely plays a crucial role in its ability to bind to raw starch.

5. Conclusion

This research provides significant insights into the influence of structural modifications on enzyme function and stability of BaqA, a raw starch-degrading α-amylase from B. aquimaris MKSC 6.2. The removal of the C-terminal 34 amino acids to produce BaqAΔC leads to increased solubility and stability, particularly under saline conditions, although at the cost of reduced substrate binding and catalytic efficiency toward soluble starch compared to the full-length enzyme. The remarkable halotolerance and the ability of BaqAΔC to retain significant amylolytic activity under high salt concentrations highlight its potential application in starch-processing industries where extreme conditions are common.

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Funding

This research was funded by the World Class Research grant from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Research, and Technology of Indonesia to Institute for Research and Community Service, Institut Teknologi Bandung (007/E5/PG.02.00.PT/2022).

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Ayra Ulpiyana: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Fina Khaerunnisa Frima: Investigation. Diandra Sekar Annisa: Investigation. Josephine Claudia Tan: Investigation. Fernita Puspasari: Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis. Reza Aditama: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision. Ihsanawati: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Supervision, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Supervision, Conceptualization. Dessy Natalia: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

We express our gratitude to Christian Heryakusuma for his invaluable assistance in English proofreading.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e33667.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

figs1.

figs2.

figs3.

figs4.

References

- 1.Modified Starch Market Anticipated to Generate $17,141.70, ` (n.d.). https://www.globenewswire.com/en/news-release/2022/10/11/2531966/0/en/Modified-Starch-Market-Anticipated-to-Generate-17-141-70-Million-and-Grow-at-4-90-CAGR-in-the-2021-2030-Forecast-Period-225-Pages-Says-Research-Dive.html (accessed November 17, 2023).

- 2.MacGregor E.A. α-Amylase structure and activity. J. Protein Chem. 1988;7 doi: 10.1007/BF01024888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Janeček Š., Svensson B., MacGregor E.A. α-Amylase: an enzyme specificity found in various families of glycoside hydrolases. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2014;71 doi: 10.1007/s00018-013-1388-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moreno M. de L., Pérez D., García M.T., Mellado E. Halophilic bacteria as a source of novel hydrolytic enzymes. Life. 2013;3 doi: 10.3390/life3010038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kumar S., Khan R.H., Khare S.K. Structural elucidation and molecular characterization of Marinobacter sp. α-amylase. Prep. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2016;46 doi: 10.1080/10826068.2015.1015564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coronado M.J., Vargas C., Hofemeister J., Ventosa A., Nieto J.J. Production and biochemical characterization of an α-amylase from the moderate halophile Halomonas meridiana. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2000;183 doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(99)00628-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Srimathi S., Jayaraman G., Feller G., Danielsson B., Narayanan P.R. Intrinsic halotolerance of the psychrophilic α-amylase from Pseudoalteromonas haloplanktis. Extremophiles. 2007;11 doi: 10.1007/s00792-007-0062-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kalpana B.J., Pandian S.K. Halotolerant, acid-alkali stable, chelator resistant and raw starch digesting α-amylase from a marine bacterium Bacillus subtilis S8-18. J. Basic Microbiol. 2014;54 doi: 10.1002/jobm.201200732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coronado M.J., Vargas C., Mellado E., Tegos G., Drainas C., Nieto J.J., Ventosa A. The α-amylase gene amyH of the moderate halophile Halomonas meridiana: cloning and molecular characterization. Microbiology (N. Y.) 2000;146 doi: 10.1099/00221287-146-4-861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Han X., Lin B., Ru G., Zhang Z., Liu Y., Hu Z. Gene cloning and characterization of an α-amylase from Alteromonas macleodii B7 for enteromorpha polysaccharide degradation. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014;24 doi: 10.4014/jmb.1304.04036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takenaka S., Miyatake A., Tanaka K., Kuntiya A., Techapun C., Leksawasdi N., Seesuriyachan P., Chaiyaso T., Watanabe M., Yoshida K.I. Characterization of the native form and the carboxy-terminally truncated halotolerant form of α-amylases from Bacillus subtilis strain FP-133. J. Basic Microbiol. 2015;55 doi: 10.1002/jobm.201400813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.CAZy - GH, (n.d.). http://www.cazy.org/Glycoside-Hydrolases.html (accessed November 17, 2023).

- 13.Drula E., Garron M.L., Dogan S., Lombard V., Henrissat B., Terrapon N. The carbohydrate-active enzyme database: functions and literature. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022;50 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Janeček Š., Svensson B. How many α-amylase GH families are there in the CAZy database? Amylase. 2022;6 doi: 10.1515/amylase-2022-0001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsuura Y., Kusunoki M., Harada W., Kakudo M. Structure and possible catalytic residues of Taka-amylase A. J. Biochem. 1984;95 doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a134659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takata H., Kuriki T., Okada S., Takesada Y., Iizuka M., Minamiura N., Imanaka T. Action of neopullulanase. Neopullulanase catalyzes both hydrolysis and transglycosylation at α-(1→4)- and α-(1→6)-glucosidic linkages. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267 doi: 10.1016/s0021-9258(19)36983-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Svensson B. Protein engineering in the α-amylase family: catalytic mechanism, substrate specificity, and stability. Plant Mol. Biol. 1994;25 doi: 10.1007/BF00023233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Uitdehaag J.C.M., Mosi R., Kalk K.H., Van der Veen B.A., Dijkhuizen L., Withers S.G., Dijkstra B.W. X-ray structures along the reaction pathway of cyclodextrin glycosyltransferase elucidate catalysis in the α-amylase family. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1999;6 doi: 10.1038/8235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stam M.R., Danchin E.G.J., Rancurel C., Coutinho P.M., Henrissat B. Dividing the large glycoside hydrolase family 13 into subfamilies: towards improved functional annotations of α-amylase-related proteins. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 2006;19 doi: 10.1093/protein/gzl044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mareček F., Janeček Š. A novel subfamily GH13_46 of the α-amylase family GH13 represented by the cyclomaltodextrinase from Flavobacterium sp. No. 92. Molecules. 2022;27 doi: 10.3390/molecules27248735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Janeček Š., Zámocká B. A new GH13 subfamily represented by the α-amylase from the halophilic archaeon Haloarcula hispanica. Extremophiles. 2020;24:207–217. doi: 10.1007/s00792-019-01147-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wei Y., Wang X., Liang J., Li X., Du L., Huang R. Identification of a halophilic α-amylase gene from Escherichia coli JM109 and characterization of the recombinant enzyme. Biotechnol. Lett. 2013;35 doi: 10.1007/s10529-013-1175-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tan T.C., Mijts B.N., Swaminathan K., Patel B.K.C., Divne C. Crystal structure of the polyextremophilic α-amylase AmyB from Halothermothrix orenii: details of a productive enzyme-substrate complex and an N domain with a role in binding raw starch. J. Mol. Biol. 2008;378 doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yamaguchi R., Tokunaga H., Ishibashi M., Arakawa T., Tokunaga M. Salt-dependent thermo-reversible α-amylase: cloning and characterization of halophilic α-amylase from moderately halophilic bacterium. Kocuria varians, Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2011;89 doi: 10.1007/s00253-010-2882-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mijts B.N., Patel B.K.C. Cloning, sequencing and expression of an α-amylase gene, amyA, from the thermophilic halophile Halothermothrix orenii and purification and biochemical characterization of the recombinant enzyme. Microbiology (N. Y.) 2002;148 doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-8-2343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Puspasari F., Nurachman Z., Noer A.S., Radjasa O.K., Van Der Maarel M.J.E.C., Natalia D. Characteristics of raw starch degrading α -amylase from Bacillus aquimaris MKSC 6.2 associated with soft coral Sinularia sp. Starch/Staerke. 2011;63 doi: 10.1002/star.201000127. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Puspasari F., Radjasa O.K., Noer A.S., Nurachman Z., Syah Y.M., van der Maarel M., Dijkhuizen L., Janeček S., Natalia D. Raw starch-degrading α-amylase from Bacillus aquimaris MKSC 6.2: isolation and expression of the gene, bioinformatics and biochemical characterization of the recombinant enzyme. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2013;114 doi: 10.1111/jam.12025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Janeček Š., Kuchtová A., Petrovičová S. A novel GH13 subfamily of α-amylases with a pair of tryptophans in the helix α3 of the catalytic TIM-barrel, the LPDlx signature in the conserved sequence region v and a conserved aromatic motif at the C-terminus. Biologia (Poland) 2015;70 doi: 10.1515/biolog-2015-0165. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chai Y.Y., Rahman R.N.Z.R.A., Illias R.M., Goh K.M. Cloning and characterization of two new thermostable and alkalitolerant α-amylases from the Anoxybacillus species that produce high levels of maltose. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012;39 doi: 10.1007/s10295-011-1074-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Finore I., Kasavi C., Poli A., Romano I., Oner E.T., Kirdar B., Dipasquale L., Nicolaus B., Lama L. Purification, biochemical characterization and gene sequencing of a thermostable raw starch digesting α-amylase from Geobacillus thermoleovorans subsp. stromboliensis subsp. nov. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011;27 doi: 10.1007/s11274-011-0715-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mok S.C., Teh A.H., Saito J.A., Najimudin N., Alam M. Crystal structure of a compact α-amylase from Geobacillus thermoleovorans. Enzyme Microb Technol. 2013;53 doi: 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2013.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mehta D., Satyanarayana T. Domain C of thermostable α-amylase of Geobacillus thermoleovorans mediates raw starch adsorption. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014;98 doi: 10.1007/s00253-013-5459-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sarian F.D., Janeček Š., PijningIhsanawati T., Nurachman Z., Radjasa O.K., Dijkhuizen L., Natalia D., Van Der Maarel M.J.E.C. A new group of glycoside hydrolase family 13 α-amylases with an aberrant catalytic triad. Sci. Rep. 2017;7 doi: 10.1038/srep44230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miller G.L. Use of dinitrosalicylic acid reagent for determination of reducing sugar. Anal. Chem. 1959;31 doi: 10.1021/ac60147a030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.H. Motulsky, A. Christopoulos, Fitting Models to Biological Data using Linear and Nonlinear Regression A practical guide to curve fitting Contents at a Glance, (n.d.). www.graphpad.com. (accessed May 16, 2024).

- 36.Božić N., Rozeboom H.J., Lončar N., Slavić M.Š., Janssen D.B., Vujčić Z. Characterization of the starch surface binding site on Bacillus paralicheniformis α-amylase. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020;165:1529–1539. doi: 10.1016/J.IJBIOMAC.2020.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jumper J., Evans R., Pritzel A., Green T., Figurnov M., Ronneberger O., Tunyasuvunakool K., Bates R., Žídek A., Potapenko A., Bridgland A., Meyer C., Kohl S.A.A., Ballard A.J., Cowie A., Romera-Paredes B., Nikolov S., Jain R., Adler J., Back T., Petersen S., Reiman D., Clancy E., Zielinski M., Steinegger M., Pacholska M., Berghammer T., Bodenstein S., Silver D., Vinyals O., Senior A.W., Kavukcuoglu K., Kohli P., Hassabis D. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature. 2021;596(7873 596):583–589. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03819-2. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schrödinger L., DeLano W. PyMOL | pymol.org. 2020. https://pymol.org/2/

- 39.Gasteiger E., Hoogland C., Gattiker A., Duvaud S., Wilkins M.R., Appel R.D., Bairoch A. The Proteomics Protocols Handbook. Humana Press; Totowa, NJ: 2005. Protein identification and analysis tools on the ExPASy server; pp. 571–607. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Agostini F., Cirillo D., aria Livi C.M., Delli Ponti R., aetano Tartaglia G.G. ccSOL omics: a webserver for solubility prediction of endogenous and heterologous expression in Escherichia coli. Bioinformatics. 2014;30 doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Käll L., Krogh A., Sonnhammer E.L.L. Advantages of combined transmembrane topology and signal peptide prediction-the Phobius web server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shofiyah S.S., Yuliani D., Widya N., Sarian F.D., Puspasari F., RadjasaIhsanawati O.K., Natalia D. Isolation, expression, and characterization of raw starch degrading α-amylase from a marine lake Bacillus megaterium NL3. Heliyon. 2020;6 doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e05796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Verma D.K., Vasudeva G., Sidhu C., Pinnaka A.K., Prasad S.E., Thakur K.G. Biochemical and taxonomic characterization of novel Haloarchaeal strains and purification of the recombinant halotolerant α-amylase discovered in the isolate. Front. Microbiol. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.02082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Abd-Elaziz A.M., Karam E.A., Ghanem M.M., Moharam M.E., Kansoh A.L. Production of a novel α-amylase by Bacillus atrophaeus NRC1 isolated from honey: purification and characterization. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020;148 doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.01.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mou H., Secundo F., Hu X., Zhu B. Editorial: marine microorganisms and their enzymes with biotechnological application. Front. Microbiol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.901161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fukuchi S., Yoshimune K., Wakayama M., Moriguchi M., Nishikawa K. Unique amino acid composition of proteins in halophilic bacteria. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;327 doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(03)00150-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dheeran P., Kumar S., Jaiswal Y.K., Adhikari D.K. Characterization of hyperthermostable α-amylase from Geobacillus sp. IIPTN, Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2010;86 doi: 10.1007/s00253-009-2430-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shafiei M., Ziaee A.A., Amoozegar M.A. Purification and characterization of an organic-solvent-tolerant halophilic α-amylase from the moderately halophilic Nesterenkonia sp. strain F. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011;38 doi: 10.1007/s10295-010-0770-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Afrisham S., Badoei Delfard A., Namaki Shoshtari A., Karami Z. Production and characterization of a thermophilic and extremely halotolerant alpha-amylase isolated from Anoxybacillus gonensis AT23. Journal of Microbial World. 2017;10:176–191. https://jmw.jahrom.iau.ir/article_654048.html [Google Scholar]

- 50.Khajeh K., Naderi-Manesh H., Ranjbar B., akbar Moosavi-Movahedi A., Nemat-Gorgani M. Chemical modification of lysine residues in Bacillus α-amylases: effect on activity and stability. Enzyme Microb Technol. 2001;28 doi: 10.1016/S0141-0229(01)00296-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.