Abstract

Background

Vaccines against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) are crucial for ending the pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Currently, the cumulative effect of booster shots of mRNA vaccines on adverse events is not sufficiently characterized.

Methods

A survey-based study on vaccine adverse events was conducted in a Japanese medical institute after the third dose of Pfizer BNT162b2. Adverse events were grouped using network analysis, and a heteroscedastic probit model was built to analyse adverse events.

Results

There were two main clusters of adverse events, systemic and local injection site-associated events. Subject background and the experience of previous vaccine-related adverse events were variably associated with the occurrence and intensity of adverse events following the third dose. Among adverse events, only lymphadenopathy increased prominently following the third dose, while the largest increase in other systemic adverse events occurred generally following the second dose.

Conclusions

The effect of repeated booster vaccines on the frequency and intensity of adverse events differs depending on the kind of adverse event.

Keywords: Vaccine, Adverse reaction, Network analysis, Lymphadenopathy, COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, mRNA vaccine and booster vaccination

1. Introduction

Vaccines against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) are crucial for ending the pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), but there is still lingering apprehension over adverse events. Previous reports noted an increase in adverse events following booster shots of these vaccines, and this raises the risk of avoidance of boosters in the population. Understanding the characteristics of adverse events following vaccination allows public health authorities and clinicians to explain possible adverse events to populations or patients confidently based on real data, which may mitigate the sense of uncertainty and abject fear. The accumulation of scientific data is also a means to fight against the disinformation that is so prevalent regarding COVID-19 and its vaccines. However, few studies in Japan have investigated adverse events following the third dose of the COVID-19 vaccine and how their frequency or intensity changes from previous doses [1]. There is a concern that reactogenicity to mRNA vaccines might differ between different parts of the world due to various factors, including the difference in the frequency of human leukocyte antigen types [2]. Thus, it is necessary to collect data on adverse events among Japanese.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study design

To investigate the adverse events following three doses of the BNT162b2 vaccine, we conducted a survey using Google Forms for faculty members of Nihon University School of Medicine, employees of the Nihon University Itabashi Hospital, medical students of the Nihon University School of Medicine, and nursing students of Nihon University Nursing School from December 27, 2021, to March 5, 2022. The online survey questionnaires included the characteristics of the participants, such as age, sex, occupation, medical histories, ABO blood type, smoking, and antipyretics use. Regarding adverse reactions to the COVID-19 vaccine, participants were asked about the following symptoms, pain, and swelling at the inoculation site, fever, fatigue or malaise, headache, being uncomfortable and/or vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, arthralgia, rash, sore throat, and anaphylactic reaction. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Nihon University School of Medicine (approval number: P21-06-1). All procedures were performed under the guidelines of our institutional ethics committee and adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2. Statistical analyses

2.2.1. Network analysis

Networks were used to visualize the connections of adverse events. Networks were built with the IsingFit method in the IsingFit package, igraph and qgraph of R (ver. 4.1.3) [3,4] to assess the connection of adverse events. The model employed in the IsingFit package is a binary equivalent of Gaussian approximation methods, which is applicable only to two-state data; interactions are considered pairwise, and the data need to be cross-sectional. This package builds a figure of a network. In this figure, each symptom is represented with a circle or node, and a pair of nodes are connected with a line (edge). A green edge between two nodes represents a positive connection between two symptoms, and a red edge shows a negative connection. The thickness of the edge indicates the strength of the connection between two symptoms [5,6]. Clusters of nodes, or communities, were identified with the walktrap algorithm [7].

2.2.2. Heteroscedastic probit model

After delineation of the structures of communities in networks, some adverse events that consistently formed communities in all three networks were grouped together and were used for further analysis. The homogeneity of error variance over a range of observations, or homoscedasticity, was checked with the Breusch‒Pagan (BP) test with Koenker's correction [8,9]. For the analysis of the adverse events following the second and third booster shots, the heteroscedastic probit model (HPM) [10] was created to assess the effect of various responder factors on a given adverse event group. Adverse events following the second dose were classified as follows: no report as 0 and reported as 1. Adverse events following the third dose were classified into three ordered factorial values: no report of adverse event as 0; worst adverse event ever (worser adverse events following the third dose compared to both the first and the second doses, or the first experience of the event following the third dose) as 2; and non-worst event (having experience of the event following the third dose but no report of worse reactions compared to the first and second doses and unable to be classified as 2) as 1. Unlike ordered probit and ordered logit models that assume homoscedasticity, the HPM is less prone to produce biased parameter estimates and misspecification of errors in predicting a latent variable with heteroscedastic latent variables [10,11]. While the magnitude of a regression coefficient of a homoscedastic model often lacks relevance to the actual value of a latent variable, a heteroscedastic model is useful in predicting the real value of the latent variable. In a heteroscedastic model, this is accomplished with the use of marginal effects. A marginal effect shows the influence of the change in an explanatory variable from a particular value to another particular value on the probability of a specific value of the latent variable. The HPM estimates threshold values for a latent variable, at which value the marginal effect of an explanatory variable differs. The goodness of fit for the HPMs was evaluated with McFadden's test. We also built an additional model to analyse lymphadenopathy following the third dose. These models were built and analysed with R, and the lmtest and oglmx packages were used for the BP test and HPM, respectively [12,13]. The correlation of variables was checked visually and then with variance inflation factors or the chi-squared test. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic characteristics of the study population

After the exclusion of people who did not consent or had inconsistent vaccination status reports, we obtained 793 responses. A total of 99.2 % of subjects completed the third dose of the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. A total of 0.6 % of subjects did not receive the booster after the second dose of the vaccine, and 0.1 % had never been vaccinated (Table 1). Only thirteen participants had a history of COVID-19. Other characteristics are also summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of responders in this study (N = 793). Values within parentheses represent percentages.

| Vaccination status | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Completed third dose | 787 (99.2) | ||

| Up to the second dose | 5 (0.6) | ||

| Never vaccinated | 1 (0.1) | ||

| Age | Age group | median age (lower quartile, upper quartile) in years | |

| (Total) | 34 (18, 49) | ||

| <25 years | 21 (20, 23) | 235 (29.6) | |

| 25–40 years | 29 (26, 39) | 290 (36.6) | |

| ≥40 years | 58 (45, 75) | 262 (33.0) | |

| Sex | Female | 415 (52.3) | |

| Male | 376 (47.4) | ||

| Occupation | Medical doctors | 165 (20.8) | |

| Nurses | 49 (6.2) | ||

| Other licenced medical professionals | 46 (5.8) | ||

| Medical students | 238 (30.0) | ||

| Nursing students | 72 (9.1) | ||

| Others | 221 (27.9) | ||

| Medical histories |

Allergic reaction to vaccines in the past | 24 (3.0) | |

| Food or medication allergy | 151 (19.0) | ||

| Fat or glucose metabolism disorders | 34 (4.3) | ||

| Malignancy | 5 (0.6) | ||

| Obstetrical or gynaecological conditions other than malignancies | 9 (1.1) | ||

| Asthma | 14 (1.8) | ||

| Hypertension |

31 (3.9) |

||

| Current use of medication |

188 (23.7) |

||

| ABO blood type | A | 273 (34.4) | |

| AB | 82 (10.3) | ||

| B | 192 (24.2) | ||

| O | 225 (28.4) | ||

| Smoking | Naive | 663 (83.6) | |

| Past smokers | 107 (13.5) | ||

| Current smokers | 61 (7.7) | ||

| Antipyretics use | Prior to vaccination | ||

| First dose | 123 (15.5) | ||

| Second dose | 181 (22.8) | ||

| Third dose | 176 (22.2) | ||

| After vaccination with BNT162b2 but without/before the onset of any event | First dose | 163 (20.6) | |

| Second dose | 224 (28.2) | ||

| Third dose | 545 (68.7) | ||

| After the onset of any event | First dose | 122 (15.4) | |

| Second dose | 263 (33.2) | ||

| Third dose | 342 (43.1) | ||

3.2. Reactogenicity of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine

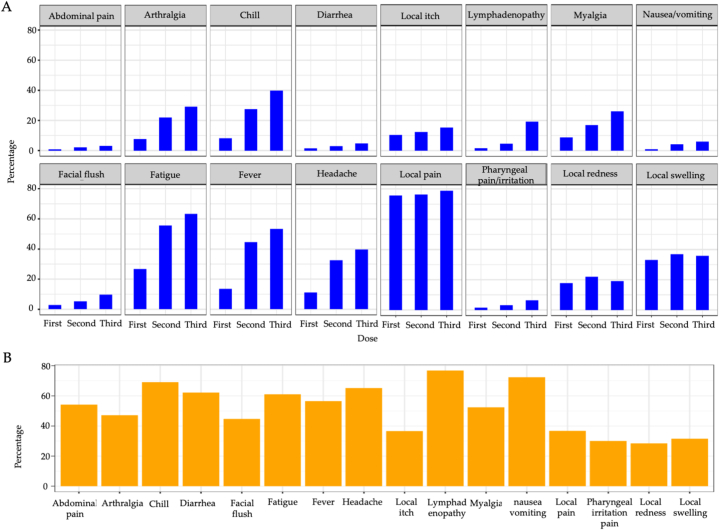

Fig. 1 (and Table S1) summarizes the distribution of self-reported adverse events. Anaphylactic reactions were reported in 0.4 %, 0.4 %, and 0.5 % of the subjects following the first, second, and third doses, respectively. Neither myocarditis nor pericarditis was reported. Most adverse events gradually increased from the first dose to the third dose or prominently increased following the second dose. Notably, only lymphadenopathy increased prominently following the third dose (Fig. 1A). The percentage of those who experienced the worst ever symptoms following the third dose for each of the main adverse events is shown in Fig. 1B. Systemic adverse events tended to be more intense than previous doses, but local adverse events were less likely to worsen.

Fig. 1.

Reported adverse events following each dose of BNT162b2. (A) Most adverse events increased sequentially following booster doses. Lymphadenopathy increased prominently only after the third dose. (B) The percentage of those who experienced the worst ever symptoms for each of the main adverse events among those with adverse events following the third dose. Systemic adverse events following the third dose tended to be more intense than those following the third dose compared to the second dose, but local adverse events were less likely to worsen.

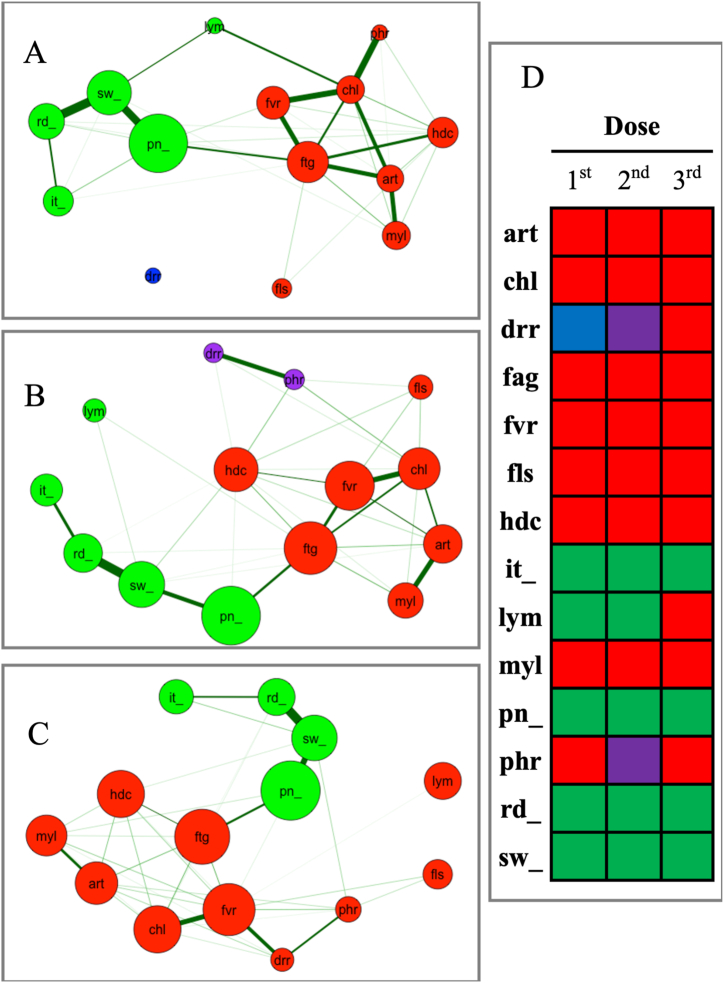

3.3. Network analyses

A network was built for each vaccine dose (Fig. 2A–B and C for the first, second and third, respectively). Four adverse events, pain, swelling, itching and redness of the local injection site, were clustered in the same group in all 3 networks and formed a ‘local event group’. The other 7 adverse events, arthralgia, chill, facial flush, fatigue, fever, headache, and myalgia were consistently clustered in the same group in all networks and formed a ‘systemic event group (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

Networks following the first (A), second (B) and third (C) doses of the BNT162b2 vaccine. Four injection-associated local events (i.e., pain, swelling, redness and itching) were consistently clustered together. Seven systemic adverse events (i.e., arthralgia, chills, facial flush, fatigue, fever, headache and myalgia) formed another cluster in all three networks. The colour of each node represents which cluster a given node belongs to in a network, and clusters seen across all three networks are represented with the same node colours (D). Abbreviations [art; arthralgia, chl; chills, drr; diarrhea, fag; fa-tigue, fvr; fever, fls; facial flush, hdc; headache, it; itching at the local injection site, lym; lymphadenopathy, myl; myalgia, pn; pain at the local injection site, phr; pharyn-geal irritation/pain, rd; redness at the local injection site, sw; swelling of the local injection site].

3.4. Heteroscedastic probit model

Based on the results of network analyses, we defined the following two groups: the ‘local event group’, which consisted of itching, pain, redness and swelling of the injection site, and the ‘systemic event group’, which consisted of arthralgia, chills, facial flush, fatigue, fever, headache, and myalgia.

BP tests for all four formulas modelling the systemic/local adverse events following the second/third doses rejected the null hypothesis of homoscedasticity. The main results of the analysis are shown in Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5, Table 6.

Table 2.

Heteroscedastic probit model for the grouped systemic adverse events following the second dose of BNT162b2.a

| Mean estimate | ||||||||||

| Parameter estimate | SE | 95 % CI | t value | p value | ||||||

| Sex (comparison to female) rowhead | ||||||||||

| Male | −0.11 | 0.06 | −0.22 | – | −0.54 | −1.82 | 0.0689 | |||

| Age (comparison tob <25 years) rowhead | ||||||||||

| 25–40 years | 0.00 | 0.02 | −0.04 | – | −0.07 | 0.22 | 0.8256 | |||

| ≥40 years | −0.10 | 0.05 | −0.20 | – | −0.49 | −1.74 | 0.0820 | |||

| Blood type (comparison to type A) rowhead | ||||||||||

| AB | 0.19 | 0.37 | −0.53 | – | −0.85 | 0.52 | 0.6004 | |||

| B | −0.16 | 0.08 | −0.33 | – | −0.80 | −1.96 | 0.0499 | * | ||

| O | −0.08 | 0.05 | −0.19 | – | −0.45 | −1.55 | 0.1211 | |||

| Medical history rowhead | ||||||||||

| Asthma | −0.10 | 0.06 | −0.21 | – | −0.52 | −1.56 | 0.1188 | |||

| Metabolism disorders | −0.01 | 0.06 | −0.12 | – | −0.24 | −0.11 | 0.9104 | |||

| Allergic reaction to vaccine | 0.10 | 0.11 | −0.12 | – | −0.13 | 0.91 | 0.3648 | |||

| Smoking (comparison to naive) rowhead | ||||||||||

| Past | 0.06 | 0.07 | −0.08 | – | −0.10 | 0.81 | 0.4198 | |||

| Current | −0.07 | 0.05 | −0.16 | – | −0.38 | −1.34 | 0.1814 | |||

| Adverse events following the first dose of BNT162b2 rowhead | ||||||||||

| Systemic events | 0.06 | 0.05 | −0.04 | – | −0.02 | 1.17 | 0.2423 | |||

| Local events | 0.15 | 0.09 | −0.03 | – | 0.10 | 1.68 | 0.0928 | |||

| Use of antipyretics (comparison to those who did not take any)c rowhead | ||||||||||

| Timing 1 | −0.05 | 0.04 | −0.13 | – | −0.29 | −1.10 | 0.2731 | |||

| Timing 2 | −0.07 | 0.04 | −0.16 | – | −0.37 | −1.49 | 0.1354 | |||

| Timing 3 | −0.07 | 0.05 | −0.16 | – | −0.38 | −1.39 | 0.1633 | |||

| Marginal effects on the occurrence of adverse events | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marginal effect | SE | 95 % CI | t value | p value | ||||

| Sex (comparison to female) | ||||||||

| Male | −0.04 | 0.03 | −0.09 | – | 0.01 | −1.43 | 0.1527 | |

| Age (comparison to <25 years) | ||||||||

| 25–40 years | −0.05 | 0.02 | −0.10 | – | 0.00 | −1.94 | 0.0530 | |

| ≥40 years | −0.13 | 0.03 | −0.18 | – | −0.08 | −4.99 | 6.10 × 10−7 | *** |

| Blood type (comparison to type A) | ||||||||

| AB | −0.02 | 0.05 | −0.12 | – | 0.08 | −0.43 | 0.6663 | |

| B | −0.10 | 0.05 | −0.19 | – | −0.01 | −2.25 | 0.0248 | * |

| O | −0.05 | 0.04 | −0.13 | – | 0.03 | −1.29 | 0.1979 | |

| Medical history | ||||||||

| Asthma | −0.06 | 0.06 | −0.18 | – | 0.05 | −1.08 | 0.2792 | |

| Metabolism disorders | −0.01 | 0.05 | −0.11 | – | 0.09 | −0.23 | 0.8220 | |

| Allergic reaction to vaccine | 0.03 | 0.07 | −0.11 | – | 0.17 | 0.44 | 0.6604 | |

| Smoking (comparison to naive) | ||||||||

| Past | 0.06 | 0.03 | −0.01 | – | 0.12 | 1.63 | 0.1041 | |

| Current | −0.05 | 0.04 | −0.13 | – | 0.02 | −1.37 | 0.1717 | |

| Adverse events following the first dose of BNT162b2 | ||||||||

| Systemic events | 0.23 | 0.03 | 0.17 | – | 0.30 | 7.08 | 1.46 × 10−12 | *** |

| Local events | 0.18 | 0.04 | 0.09 | – | 0.26 | 4.07 | 0.0001 | *** |

| Use of antipyretics (comparison to those who did not take any)c | ||||||||

| Timing 1 | 0.00 | 0.04 | −0.07 | – | 0.07 | 0.12 | 0.9032 | |

| Timing 2 | 0.02 | 0.03 | −0.05 | – | 0.09 | 0.60 | 0.5480 | |

| Timing 3 | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.08 | – | 0.06 | −0.33 | 0.7424 | |

SE, standard error.

General properties of the model, Breusch‒Pagan test, Chi-square 73.38, p = 2.53 × 10−9,McFadden's pseudo R-square test 0.20, Log-likelihood −384.84.

Statistical significance. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Timing 1, After the onset of adverse events following the first dose of BNT162b2, Timing 2, Prior to the second dose of BNT162b2, Timing 3, After the second dose of BNT162b2 but without or before the onset of adverse events.

Table 3.

Heteroscedastic probit model for the grouped local adverse events following the second dose of BNT162b2.a

| Mean estimate | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter estimate | SE | 95 % CI | t value | p value | ||||

| Sex (comparison to female) | ||||||||

| Male | −0.10 | 0.18 | −0.45 | – | −0.97 | −0.54 | 0.5912 | |

| Age (comparison to <25 years) | ||||||||

| 25–40 years | 0.03 | 0.07 | −0.10 | – | −0.16 | 0.46 | 0.6476 | |

| ≥40 years | 0.02 | 0.05 | −0.08 | – | −0.13 | 0.42 | 0.6726 | |

| Blood type (comparison to type A) | ||||||||

| AB | 0.00 | 0.02 | −0.04 | – | −0.07 | 0.15 | 0.8779 | |

| B | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.02 | – | −0.05 | 0.20 | 0.8440 | |

| O | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.02 | – | −0.04 | 0.07 | 0.9420 | |

| Medical history | ||||||||

| Asthma | 0.00 | 195.49 | −383 | – | −751 | 0.00 | 1.0000 | |

| Metabolism disorders | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.08 | – | −0.16 | −0.40 | 0.6865 | |

| Allergic reaction to vaccine | 0.02 | 0.05 | −0.08 | – | −0.13 | 0.35 | 0.7260 | |

| Smoking (comparison to naive) | ||||||||

| Past | −0.03 | 0.08 | −0.19 | – | −0.41 | −0.39 | 0.6995 | |

| Current | −0.04 | 0.09 | −0.22 | – | −0.46 | −0.39 | 0.6976 | |

| Adverse events following the first dose of BNT162b2 | ||||||||

| Systemic events | 0.04 | 0.11 | −0.18 | – | −0.31 | 0.38 | 0.7040 | |

| Local events | 0.33 | 0.26 | −0.18 | – | −0.03 | 1.26 | 0.2060 | |

| Use of antipyretics (comparison to those who did not take any)b | ||||||||

| Timing 1 | −0.02 | 0.06 | −0.15 | – | −0.31 | −0.38 | 0.7008 | |

| Timing 2 | 0.00 | 0.02 | −0.03 | – | −0.06 | 0.15 | 0.8812 | |

| Timing 3 | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.04 | – | −0.08 | −0.31 | 0.7603 | |

| Marginal effects on the occurrence of local adverse events (outcome 1) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marginal effect | SE | 95 % CI | t value | p value | ||||

| Sex (comparison to female) | ||||||||

| Male | −0.34 | 63.05 | −124 | – | 123 | −0.01 | 0.9957 | |

| Age (comparison to <25 years) | ||||||||

| 25–40 years | 0.04 | 11.16 | −21.8 | – | 21.9 | 0.00 | 0.9972 | |

| ≥40 years | 0.03 | 8.02 | −15.7 | – | 15.8 | 0.00 | 0.9968 | |

| Blood type (comparison to type A) | ||||||||

| AB | −0.01 | 2.62 | −5.13 | – | 5.12 | 0.00 | 0.9974 | |

| B | 0.05 | 8.05 | −15.7 | – | 15.8 | 0.01 | 0.9953 | |

| O | 0.03 | 4.53 | −8.85 | – | 8.90 | 0.01 | 0.9956 | |

| Medical history | ||||||||

| Asthma | 0.37 | 0.50 | −0.61 | – | 1.35 | 0.74 | 0.4605 | |

| Metabolism disorders | −0.05 | 8.66 | −17.0 | – | 16.9 | −0.01 | 0.9954 | |

| Allergic reaction to vaccine | 0.06 | 9.54 | −18.6 | – | 18.8 | 0.01 | 0.9948 | |

| Smoking (comparison to naive) | ||||||||

| Past | −0.11 | 25.00 | −49.1 | – | 48.9 | 0.00 | 0.9966 | |

| Current | −0.15 | 27.66 | −54.4 | – | 54.1 | −0.01 | 0.9956 | |

| Adverse events following the first dose of BNT162b2 | ||||||||

| Systemic events | 0.12 | 20.06 | −39.2 | – | 39.4 | 0.01 | 0.9954 | |

| Local events | 0.63 | 42.63 | −82.9 | – | 84.2 | 0.01 | 0.9882 | |

| Use of antipyretics (comparison to those who did not take any)b | ||||||||

| Timing 1 | −0.09 | 16.77 | −33.0 | – | 32.8 | −0.01 | 0.9955 | |

| Timing 2 | 0.04 | 7.51 | −14.7 | – | 14.8 | 0.01 | 0.9953 | |

| Timing 3 | 0.01 | 4.74 | −9.28 | – | 9.31 | 0.00 | 0.9976 | |

SE, standard error.

General properties of the model, Breusch‒Pagan test, Chi-square 71.33, p = 5.83 × 10−9,McFadden's pseudo R-square test 0.45, Log-likelihood −220.44.

Timing 1, After the onset of adverse events following the first dose of BNT162b2, Timing 2, Prior to the second dose of BNT162b2, Timing 3, After the second dose of BNT162b2 but without or before the onset of adverse events.

Table 4.

Heteroscedastic probit model of systemic adverse events following the third dose of BNT162b2.a

| Mean estimate | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter estimateb | SE | 95 % CI | t value | p value | ||||

| Sex (comparison to female) | ||||||||

| Male | 0.02 | 0.02 | −0.01 | – | 0.06 | 1.34 | 0.1797 | |

| Age (comparison to <25 years) | ||||||||

| 25–40 years | 0.02 | 0.02 | −0.02 | – | 0.06 | 0.97 | 0.3315 | |

| ≥40 years | 0.03 | 0.02 | −0.02 | – | 0.07 | 1.10 | 0.2711 | |

| Blood type (comparison to type A) | ||||||||

| AB | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.06 | – | 0.04 | −0.30 | 0.7641 | |

| B | 0.00 | 0.02 | −0.05 | – | 0.04 | −0.08 | 0.9388 | |

| O | 0.01 | 0.02 | −0.03 | – | 0.06 | 0.61 | 0.5444 | |

| Medical history | ||||||||

| Asthma | 0.11 | 0.09 | −0.08 | – | 0.29 | 1.16 | 0.2471 | |

| Metabolism disorders | 0.01 | 0.04 | −0.08 | – | 0.10 | 0.24 | 0.8069 | |

| Allergic reaction to vaccine | −0.07 | 0.03 | −0.12 | – | −0.02 | −2.56 | 0.0105 | ** |

| Smoking (comparison to naive) | ||||||||

| Past | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.06 | – | 0.03 | −0.53 | 0.5975 | |

| Current | 0.00 | 0.03 | −0.07 | – | 0.06 | −0.06 | 0.9520 | |

| Systemic event | ||||||||

| First dose of BNT162b2 | −0.03 | 0.02 | −0.07 | – | 0.00 | −1.74 | 0.0814 | |

| Second dose of BNT162b2 | −0.32 | 0.05 | −0.42 | – | −0.22 | −6.32 | 2.58 × 10−10 | *** |

| Local event | ||||||||

| First dose of BNT162b2 | 0.01 | 0.03 | −0.05 | – | 0.07 | 0.23 | 0.8157 | |

| Second dose of BNT162b2 | −0.14 | 0.06 | −0.26 | – | −0.02 | −2.33 | 0.0197 | ** |

| Use of antipyretics (comparison to those who did not take any)c | ||||||||

| Timing 1 | 0.02 | 0.02 | −0.02 | – | 0.05 | 0.78 | 0.4376 | |

| Timing 2 | −0.11 | 0.03 | −0.18 | – | 0.05 | −3.42 | 0.0006 | *** |

| Timing 3 | 0.00 | 0.02 | −0.03 | – | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.9403 | |

| Marginal effects on the absence of systemic events (outcome 0) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marginal effects | SE | 95 % CI | t value | p value | ||||

| Sex (comparison to female) | ||||||||

| Male | 0.04 | 0.03 | −0.02 | – | 0.09 | 1.33 | 0.1847 | |

| Age (comparison to <25 years) | ||||||||

| 25–40 years | 0.03 | 0.03 | −0.03 | – | 0.09 | 0.96 | 0.3391 | |

| ≥40 years | 0.04 | 0.04 | −0.03 | – | 0.11 | 1.09 | 0.2748 | |

| Blood type (comparison to type A) | ||||||||

| AB | −0.01 | 0.05 | −0.10 | – | 0.08 | −0.28 | 0.7822 | |

| B | 0.00 | 0.04 | −0.07 | – | 0.07 | −0.06 | 0.9552 | |

| O | 0.02 | 0.03 | −0.05 | – | 0.09 | 0.63 | 0.5286 | |

| Medical history | ||||||||

| Asthma | 0.11 | 0.08 | −0.06 | – | 0.28 | 1.27 | 0.2027 | |

| Metabolism disorders | 0.02 | 0.06 | −0.11 | – | 0.14 | 0.27 | 0.7899 | |

| Allergic reaction to vaccine | −0.15 | 0.09 | −0.32 | – | 0.03 | −1.67 | 0.0945 | |

| Smoking (comparison to naive) | ||||||||

| Past | −0.02 | 0.04 | −0.09 | – | 0.06 | −0.48 | 0.6279 | |

| Current | −0.01 | 0.06 | −0.12 | – | 0.11 | −0.09 | 0.9306 | |

| Systemic event | ||||||||

| First dose of BNT162b2 | −0.06 | 0.03 | −0.12 | – | 0.00 | −1.94 | 0.0520 | |

| Second dose of BNT162b2 | −0.35 | 0.05 | −0.44 | – | −0.25 | −7.28 | 3.25 × 10−13 | *** |

| Local event | ||||||||

| First dose of BNT162b2 | 0.01 | 0.05 | −0.09 | – | 0.12 | 0.23 | 0.8164 | |

| second dose of BNT162b2 | −0.17 | 0.06 | −0.29 | – | −0.05 | −2.87 | 0.0041 | *** |

| Use of antipyretics (comparison to those who did not take any)c | ||||||||

| Timing 1 | 0.02 | 0.03 | −0.04 | – | 0.08 | 0.73 | 0.4629 | |

| Timing 2 | −0.15 | 0.04 | −0.22 | – | −0.08 | −4.29 | 1.81 × 10−5 | *** |

| Timing 3 | 0.04 | 0.03 | −0.01 | – | 0.10 | 1.58 | 0.1151 | |

| Marginal effects on the non-worst systemic events (outcome 1) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marginal effects | SE | 95 % CI | t value | p value | ||||

| Sex (comparison to female) | ||||||||

| Male | 0.04 | 0.03 | −0.01 | – | 0.10 | 1.54 | 0.1239 | |

| Age (comparison to <25 years) | ||||||||

| 25–40 years | 0.03 | 0.04 | −0.04 | – | 0.11 | 0.91 | 0.3649 | |

| ≥40 years | 0.06 | 0.04 | −0.03 | – | 0.14 | 1.27 | 0.2052 | |

| Blood type (comparison to type A) | ||||||||

| AB | −0.02 | 0.04 | −0.09 | – | 0.05 | −0.54 | 0.5926 | |

| B | −0.02 | 0.03 | −0.09 | – | 0.04 | −0.61 | 0.5388 | |

| O | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.07 | – | 0.05 | −0.24 | 0.8091 | |

| Medical history | ||||||||

| Asthma | −0.14 | 0.07 | −0.28 | – | −0.01 | −2.10 | 0.0359 | ** |

| Metabolism disorders | −0.04 | 0.05 | −0.15 | – | 0.06 | −0.83 | 0.4078 | |

| Allergic reaction to vaccine | −0.07 | 0.05 | −0.17 | – | 0.03 | −1.42 | 0.1564 | |

| Smoking (comparison to naive) | ||||||||

| Past | −0.06 | 0.03 | −0.13 | – | 0.00 | −1.89 | 0.0585 | |

| Current | 0.03 | 0.05 | −0.07 | – | 0.13 | 0.57 | 0.5656 | |

| Systemic event | ||||||||

| First dose of BNT162b2 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.00 | – | 0.12 | 2.10 | 0.0359 | ** |

| Second dose of BNT162b2 | 0.16 | 0.04 | 0.09 | – | 0.23 | 4.32 | 2.0 × 10−5 | *** |

| Local event | ||||||||

| First dose of BNT162b2 | 0.00 | 0.04 | −0.08 | – | 0.07 | −0.12 | 0.9044 | |

| Second dose of BNT162b2 | −0.02 | 0.05 | −0.11 | – | 0.08 | −0.34 | 0.7307 | |

| Use of antipyretics (comparison to those who did not take any)c | ||||||||

| Timing 1 | 0.04 | 0.03 | −0.03 | – | 0.10 | 1.06 | 0.2900 | |

| Timing 2 | −0.11 | 0.04 | −0.19 | – | −0.04 | −2.94 | 0.0033 | *** |

| Timing 3 | 0.05 | 0.04 | −0.02 | – | 0.13 | 1.32 | 0.1853 | |

| Marginal effects on the worst systemic event (outcome 2) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marginal effects | SE | 95 % CI | t value | p value | ||||

| Sex (comparison to female) | ||||||||

| Male | −0.06 | 0.03 | −0.13 | – | 0.00 | −2.01 | 0.0445 | * |

| Age (comparison to <25 years) | ||||||||

| 25–40 years | −0.05 | 0.04 | −0.14 | – | 0.03 | −1.21 | 0.2267 | |

| ≥40 years | −0.08 | 0.05 | −0.18 | – | 0.02 | −1.59 | 0.1113 | |

| Blood type (comparison to type A) | ||||||||

| AB | 0.03 | 0.05 | −0.06 | – | 0.12 | 0.60 | 0.5477 | |

| B | 0.02 | 0.04 | −0.06 | – | 0.10 | 0.54 | 0.5873 | |

| O | −0.01 | 0.04 | −0.08 | – | 0.07 | −0.15 | 0.8821 | |

| Blood type (comparison to type A) | ||||||||

| AB | 0.03 | 0.05 | −0.06 | – | 0.12 | 0.60 | 0.5477 | |

| B | 0.02 | 0.04 | −0.06 | – | 0.10 | 0.54 | 0.5873 | |

| O | −0.01 | 0.04 | −0.08 | – | 0.07 | −0.15 | 0.8821 | |

| Medical history | ||||||||

| Asthma | 0.03 | 0.10 | −0.17 | – | 0.24 | 0.33 | 0.7418 | |

| Metabolism disorders | 0.03 | 0.07 | −0.11 | – | 0.18 | 0.46 | 0.6473 | |

| Allergic reaction to vaccine | 0.14 | 0.06 | 0.02 | – | 0.26 | 2.20 | 0.0280 | ** |

| Smoking (comparison to naive) | ||||||||

| Past | 0.07 | 0.04 | −0.01 | – | 0.15 | 1.79 | 0.0736 | |

| Current | −0.03 | 0.06 | −0.15 | – | 0.10 | −0.43 | 0.6641 | |

| Systemic event | ||||||||

| First dose of BNT162b2 | −0.03 | 0.04 | −0.10 | – | 0.04 | −0.78 | 0.4345 | |

| Second dose of BNT162b2 | 0.16 | 0.05 | 0.07 | – | 0.26 | 3.43 | 0.0006 | *** |

| Local event | ||||||||

| First dose of BNT162b2 | 0.00 | 0.06 | −0.11 | – | 0.11 | −0.04 | 0.9663 | |

| Second dose of BNT162b2 | 0.16 | 0.06 | 0.04 | – | 0.28 | 2.67 | 0.0077 | *** |

| Use of antipyretics (comparison to those who did not take any)c | ||||||||

| Timing 1 | −0.05 | 0.04 | −0.13 | – | 0.03 | −1.26 | 0.2082 | |

| Timing 2 | 0.23 | 0.05 | 0.13 | – | 0.32 | 4.83 | 1.37 × 10−6 | *** |

| Timing 3 | −0.05 | 0.04 | −0.12 | – | 0.02 | −1.39 | 0.1633 | |

SE, standard error.

General properties of the model, Breusch‒Pagan test, Chi-square 85.30, p = 9.96 × 10−11,McFadden's pseudo R-square test 0.17, Log-likelihood −613.1.

Statistical significance. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Timing 1, After the onset of adverse events following the first dose of BNT162b2, Timing 2, Prior to the second dose of BNT162b2, Timing 3, After the second dose of BNT162b2 but without or before the onset of adverse events.

Table 5.

Heteroscedastic probit model for local adverse events following the third dose of BNT162b2.a

| Mean estimate | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter estimateb | SE | 95 % CI | t value | p value | ||||

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.01 | – | 0.00 | −0.98 | 0.3282 | |

| Age (comparison to <25 years) | ||||||||

| 25–40 years | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.02 | – | 0.00 | −1.75 | 0.0798 | |

| ≥40 years | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.03 | – | 0.00 | −1.93 | 0.0536 | |

| Blood type (comparison to type A) | ||||||||

| AB | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.02 | – | 0.01 | −1.08 | 0.2821 | |

| B | −0.01 | 0.00 | −0.02 | – | 0.00 | −1.41 | 0.1579 | |

| O | −0.01 | 0.00 | −0.02 | – | 0.00 | −1.55 | 0.1218 | |

| Medical history | ||||||||

| Asthma | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 | – | 0.02 | 1.05 | 0.2953 | |

| Metabolism disorders | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.01 | – | 0.01 | 0.62 | 0.5336 | |

| Allergic reaction to vaccine | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.03 | – | 0.01 | −1.00 | 0.3160 | |

| Smoking (comparison to naive) | ||||||||

| Past | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | – | 0.02 | 1.23 | 0.2195 | |

| Current | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 | – | 0.02 | 0.92 | 0.3587 | |

| Systemic event | ||||||||

| First dose of BNT162b2 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.01 | – | 0.00 | −0.57 | 0.5716 | |

| Second dose of BNT162b2 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.01 | – | 0.01 | 0.27 | 0.7847 | |

| Local event | ||||||||

| First dose of BNT162b2 | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.01 | – | 0.02 | 0.53 | 0.5954 | |

| Second dose of BNT162b2 | 0.23 | 0.08 | 0.07 | – | 0.38 | 2.90 | 0.0038 | *** |

| Use of antipyretics (comparison to those who did not take any)c | ||||||||

| Timing 1 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.01 | – | 0.01 | −0.41 | 0.6795 | |

| Timing 2 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | – | 0.02 | 1.78 | 0.0754 | |

| Timing 3 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.01 | – | 0.01 | −0.19 | 0.8512 | |

| Marginal effects on the absence of local events (outcome 0) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marginal effects | SE | 95 % CI | t value | p value | ||||

| Sex (comparison to female) | ||||||||

| Male | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.03 | – | 0.00 | −1.64 | 0.1001 | |

| Age (comparison to <25 years) | ||||||||

| 25–40 years | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.01 | – | 0.02 | 0.43 | 0.6667 | |

| ≥40 years | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.00 | – | 0.06 | 2.12 | 0.0344 | * |

| Blood type (comparison to type A) | ||||||||

| AB | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.02 | – | 0.01 | −0.05 | 0.9591 | |

| B | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.02 | – | 0.01 | −0.16 | 0.8734 | |

| O | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.02 | – | 0.02 | 0.19 | 0.8529 | |

| Medical history | ||||||||

| Asthma | 0.00 | 0.02 | −0.05 | – | 0.05 | −0.03 | 0.9800 | |

| Metabolism disorders | 0.02 | 0.02 | −0.02 | – | 0.07 | 1.10 | 0.2713 | |

| Allergic reaction to vaccine | 0.00 | 0.02 | −0.03 | – | 0.04 | 0.17 | 0.8613 | |

| Smoking (comparison to naive) | ||||||||

| Past | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.02 | – | 0.00 | −2.70 | 0.0068 | *** |

| Current | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.03 | – | 0.02 | −0.20 | 0.8441 | |

| Systemic event | ||||||||

| First dose of BNT162b2 | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.01 | – | 0.02 | 0.58 | 0.5630 | |

| Second dose of BNT162b2 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.04 | – | 0.01 | −1.07 | 0.2824 | |

| Local event | ||||||||

| First dose of BNT162b2 | −0.05 | 0.03 | −0.11 | – | 0.01 | −1.55 | 0.1211 | |

| Second dose of BNT162b2 | −0.64 | 0.05 | −0.73 | – | −0.55 | −13.85 | <2.20 × 10−16 | *** |

| Use of antipyretics (comparison to those who did not take any)c | ||||||||

| Timing 1 | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.02 | – | 0.01 | −0.31 | 0.7594 | |

| Timing 2 | −0.02 | 0.01 | −0.04 | – | 0.00 | −1.64 | 0.1020 | |

| Timing 3 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.00 | – | 0.04 | 1.97 | 0.0485 | * |

| Marginal effects on the non-worst local events (outcome 1) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marginal effects | SE | 95 % CI | t value | p value | ||||

| Sex (comparison to female) | ||||||||

| Male | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.04 | – | 0.16 | 3.49 | 0.0005 | *** |

| Age (comparison to <25 years) | ||||||||

| 25–40 years | 0.13 | 0.04 | 0.06 | – | 0.20 | 3.68 | 0.0002 | *** |

| ≥40 years | 0.07 | 0.04 | −0.01 | – | 0.15 | 1.62 | 0.1044 | |

| Blood type (comparison to type A) | ||||||||

| AB | 0.18 | 0.04 | 0.10 | – | 0.26 | 4.22 | 2.0 × 10−5 | *** |

| B | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.03 | – | 0.18 | 2.84 | 0.0045 | *** |

| O | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.04 | – | 0.17 | 2.99 | 0.0028 | *** |

| Medical history | ||||||||

| Asthma | 0.00 | 0.10 | −0.18 | – | 0.19 | 0.05 | 0.9605 | |

| Metabolism disorders | 0.10 | 0.09 | −0.07 | – | 0.27 | 1.12 | 0.2638 | |

| Allergic reaction to vaccine | 0.13 | 0.07 | −0.01 | – | 0.26 | 1.81 | 0.0702 | |

| Smoking (comparison to naive) | ||||||||

| Past | −0.02 | 0.05 | −0.12 | – | 0.07 | −0.44 | 0.6625 | |

| Current | −0.07 | 0.06 | −0.18 | – | 0.05 | −1.11 | 0.2663 | |

| Systemic event | ||||||||

| First dose of BNT162b2 | 0.01 | 0.03 | −0.05 | – | 0.07 | 0.21 | 0.8322 | |

| Second dose of BNT162b2 | 0.03 | 0.04 | −0.04 | – | 0.10 | 0.89 | 0.3720 | |

| Local event | ||||||||

| First dose of BNT162b2 | 0.08 | 0.05 | −0.03 | – | 0.19 | 1.47 | 0.1428 | |

| Second dose of BNT162b2 | 0.54 | 0.03 | 0.47 | – | 0.60 | 16.63 | <2.20 × 10−16 | * |

| Use of antipyretics (comparison to those who did not take any)c | ||||||||

| Timing 1 | 0.03 | 0.03 | −0.04 | – | 0.10 | 0.86 | 0.3922 | |

| Timing 2 | −0.07 | 0.03 | −0.13 | – | 0.00 | −1.95 | 0.0512 | |

| Timing 3 | −0.06 | 0.03 | −0.13 | – | 0.00 | −1.87 | 0.0610 | |

| Marginal effects on the worst local event (outcome 2) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marginal effects | SE | 95 % CI | t value | p value | ||||

| Sex (comparison to female) | ||||||||

| Male | −0.09 | 0.03 | −0.15 | – | −0.03 | −2.96 | 0.0031 | *** |

| Age (comparison to <25 years) | ||||||||

| 25–40 years | −0.14 | 0.04 | −0.21 | – | −0.06 | −3.68 | 0.0002 | *** |

| ≥40 years | −0.10 | 0.04 | −0.18 | – | −0.02 | −2.36 | 0.0184 | ** |

| Blood type (comparison to type A) | ||||||||

| AB | −0.18 | 0.05 | −0.27 | – | −0.09 | −3.90 | 0.0001 | *** |

| B | −0.10 | 0.04 | −0.18 | – | −0.03 | −2.74 | 0.0061 | *** |

| O | −0.10 | 0.03 | −0.17 | – | −0.04 | −2.96 | 0.0031 | *** |

| Medical history | ||||||||

| Asthma | 0.00 | 0.10 | −0.21 | – | 0.20 | −0.04 | 0.9681 | |

| Metabolism disorders | −0.12 | 0.08 | −0.28 | – | 0.03 | −1.53 | 0.1260 | |

| Allergic reaction to vaccine | −0.13 | 0.07 | −0.27 | – | 0.01 | −1.88 | 0.0607 | |

| Smoking (comparison to naive) | ||||||||

| Past | 0.04 | 0.05 | −0.06 | – | 0.13 | 0.70 | 0.4846 | |

| Current | 0.07 | 0.06 | −0.05 | – | 0.19 | 1.11 | 0.2683 | |

| Systemic event | ||||||||

| First dose of BNT162b2 | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.07 | – | 0.05 | −0.36 | 0.7177 | |

| Second dose of BNT162b2 | −0.02 | 0.04 | −0.09 | – | 0.05 | −0.52 | 0.6051 | |

| Local event | ||||||||

| First dose of BNT162b2 | −0.03 | 0.06 | −0.15 | – | 0.09 | −0.49 | 0.6256 | |

| Second dose of BNT162b2 | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.02 | – | 0.19 | 2.40 | 0.0163 | ** |

| Use of antipyretics (comparison to those who did not take any)c | ||||||||

| Timing 1 | −0.03 | 0.04 | −0.10 | – | 0.04 | −0.78 | 0.4371 | |

| Timing 2 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.02 | – | 0.15 | 2.52 | 0.0117 | ** |

| Timing 3 | 0.04 | 0.03 | −0.02 | – | 0.10 | 1.26 | 0.2062 | |

SE, standard error.

General properties of the model, Breusch‒Pagan test, Chi-square 114.23, p = 5.10 × 10−16,McFadden's pseudo R-square test 0.30, Log-likelihood −539.40.

Statistical significance. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Timing 1, Prior to the third dose of BNT162b2, Timing 2, After the third dose of BNT162b2 but without or before the onset of adverse events, Timing 3, After the onset of adverse events following the second dose of BNT162b2.

Table 6.

Heteroscedastic model of lymphadenopathy following the third dose of BNT162b2.a

| Mean estimate | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter estimateb | SE | 95 % CI | t value | p value | ||||

| Sex (comparison to female) | ||||||||

| Male | 0.07 | 0.05 | −0.03 | – | 0.18 | 1.39 | 0.1651 | |

| Age (comparison to <25 years) | ||||||||

| 25–40 years | 0.05 | 0.06 | −0.06 | – | 0.16 | 0.85 | 0.3968 | |

| ≥40 years | 0.07 | 0.05 | −0.03 | – | 0.18 | 1.39 | 0.1651 | |

| Blood type (comparison to type A) | ||||||||

| AB | −0.06 | 0.10 | −0.25 | – | 0.13 | −0.60 | 0.5501 | |

| B | 0.12 | 0.09 | −0.06 | – | 0.30 | 1.34 | 0.1810 | |

| O | 0.04 | 0.06 | −0.08 | – | 0.17 | 0.67 | 0.5010 | |

| Medical history | ||||||||

| Asthma | −0.51 | 2.51 | −5.42 | – | 4.41 | −0.20 | 0.8397 | |

| Metabolism disorders | −93.24 | 426.97 | −930 | – | 744 | −0.22 | 0.8271 | |

| Allergic reaction to vaccine | −0.23 | 1.49 | −3.14 | – | 2.69 | −0.15 | 0.8776 | |

| Smoking (comparison to naive) | ||||||||

| Past | 0.08 | 0.09 | −0.10 | – | 0.27 | 0.88 | 0.3769 | |

| Current | 0.81 | 0.54 | −0.25 | – | 1.87 | 1.50 | 0.1333 | |

| Systemic event | ||||||||

| First dose of BNT162b2 | 0.07 | 0.06 | −0.04 | – | 0.18 | 1.21 | 0.2282 | |

| Second dose of BNT162b2 | −0.27 | 0.13 | −0.53 | – | −0.02 | −2.11 | 0.0347 | * |

| Local event | ||||||||

| First dose of BNT162b2 | −0.17 | 0.11 | −0.38 | – | 0.05 | −1.53 | 0.1259 | |

| Second dose of BNT162b2 | 0.07 | 0.09 | −0.12 | – | 0.25 | 0.72 | 0.4705 | |

| Use of antipyretics (comparison to those who did not take any)c | ||||||||

| Timing 1 | 0.04 | 0.08 | −0.13 | – | 0.20 | 0.46 | 0.6477 | |

| Timing 2 | 0.08 | 0.08 | −0.08 | – | 0.23 | 0.95 | 0.3436 | |

| Timing 3 | −0.05 | 0.07 | −0.18 | – | 0.08 | −0.71 | 0.4775 | |

| Lymphadenopathy | ||||||||

| First dose of BNT162b2 | 0.03 | 0.06 | −0.08 | – | 0.15 | 0.55 | 0.5814 | |

| Second dose of BNT162b2 | 1.75 | 0.43 | 0.92 | – | 2.59 | 4.11 | 4.0 × 10−5 | *** |

| Marginal effects on the absence of lymphadenopathy (outcome 0) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marginal effects | SE | 95 % CI | t value | p value | ||||

| Sex (comparison to female) | ||||||||

| Male | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.02 | – | 0.12 | 2.74 | 0.0061 | *** |

| Age (comparison to <25 years) | ||||||||

| 25–40 years | 0.02 | 0.03 | −0.03 | – | 0.08 | 0.85 | 0.3943 | |

| ≥40 years | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.00 | – | 0.12 | 2.10 | 0.0358 | ** |

| Blood type (comparison to type A) | ||||||||

| AB | −0.02 | 0.04 | −0.11 | – | 0.06 | −0.55 | 0.5833 | |

| B | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.07 | – | 0.05 | −0.39 | 0.6990 | |

| O | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.06 | – | 0.05 | −0.22 | 0.8270 | |

| Medical history | ||||||||

| Asthma | 0.06 | 0.08 | −0.10 | – | 0.21 | 0.74 | 0.4602 | |

| Metabolism disorders | 0.03 | 0.06 | −0.08 | – | 0.15 | 0.59 | 0.5562 | |

| Allergic reaction to vaccine | 0.08 | 0.15 | −0.22 | – | 0.38 | 0.52 | 0.6061 | |

| Smoking (comparison to naive) | ||||||||

| Past | −0.03 | 0.03 | −0.10 | – | 0.04 | −0.89 | 0.3720 | |

| Current | −0.05 | 0.05 | −0.14 | – | 0.05 | −1.01 | 0.3120 | |

| Systemic event | ||||||||

| First dose of BNT162b2 | 0.02 | 0.03 | −0.03 | – | 0.07 | 0.83 | 0.4080 | |

| Second dose of BNT162b2 | 0.00 | 0.03 | −0.06 | – | 0.06 | −0.07 | 0.9420 | |

| Local event | ||||||||

| First dose of BNT162b2 | −0.10 | 0.03 | −0.17 | – | −0.04 | −3.17 | 0.0015 | *** |

| Second dose of BNT162b2 | 0.02 | 0.04 | −0.06 | – | 0.10 | 0.44 | 0.6583 | |

| Use of antipyretics (comparison to those who did not take any)c | ||||||||

| Timing 1 | −0.04 | 0.04 | −0.11 | – | 0.03 | −1.06 | 0.2894 | |

| Timing 2 | −0.09 | 0.03 | −0.14 | – | −0.03 | −3.20 | 0.0014 | *** |

| Timing 3 | −0.02 | 0.03 | −0.08 | – | 0.04 | −0.76 | 0.4502 | |

| Lymphadenopathy | ||||||||

| First dose of BNT162b2 | 0.14 | 0.02 | 0.11 | – | 0.17 | 8.84 | <2.20 × 10−16 | *** |

| Second dose of BNT162b2 | −0.58 | 0.09 | −0.76 | – | −0.41 | −6.58 | 4.80 × 10−11 | * |

| Marginal effects on non-worst lymphadenopathy (outcome 1) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marginal effects | SE | 95 % CI | t value | p value | ||||

| Sex (comparison to female) | ||||||||

| Male | −0.01 | 0.00 | −0.01 | – | 0.00 | −3.29 | 0.0010 | *** |

| Age (comparison to <25 years) | ||||||||

| 25–40 years | −0.01 | 0.00 | −0.01 | – | 0.00 | −4.29 | 2.0 × 10−5 | *** |

| ≥40 years | −0.01 | 0.00 | −0.02 | – | 0.00 | −3.46 | 0.0006 | *** |

| Blood type (comparison to type A) | ||||||||

| AB | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.01 | – | 0.00 | −1.65 | 0.0991 | |

| B | −0.01 | 0.00 | −0.02 | – | 0.00 | −3.17 | 0.0015 | *** |

| O | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.01 | – | 0.00 | −1.33 | 0.1850 | |

| Medical history | ||||||||

| Asthma | −0.03 | 0.02 | −0.08 | – | 0.02 | −1.33 | 0.1846 | |

| Metabolism disorders | −0.05 | 0.01 | −0.06 | – | −0.03 | −7.62 | 2.63 × 10−14 | *** |

| Allergic reaction to vaccine | −0.02 | 0.11 | −0.24 | – | 0.20 | −0.20 | 0.8415 | |

| Smoking (comparison to naive) | ||||||||

| Past | −0.01 | 0.00 | −0.01 | – | 0.00 | −2.90 | 0.0038 | *** |

| Current | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.05 | – | 0.04 | −0.34 | 0.7334 | |

| Systemic event | ||||||||

| First dose of BNT162b2 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | – | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.9876 | |

| Second dose of BNT162b2 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.01 | – | 0.03 | 3.84 | 0.0001 | *** |

| Local event | ||||||||

| First dose of BNT162b2 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | – | 0.03 | 4.36 | 1.0 × 10−5 | *** |

| Second dose of BNT162b2 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | – | 0.01 | 2.72 | 0.0066 | *** |

| Use of antipyretics (comparison to those who did not take any)c | ||||||||

| Timing 1 | −0.01 | 0.00 | −0.01 | – | 0.00 | −4.65 | 3.39 × 10−6 | *** |

| Timing 2 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.01 | – | 0.01 | 0.54 | 0.5885 | |

| Timing 3 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | – | 0.00 | −1.03 | 0.3007 | |

| Lymphadenopathy | ||||||||

| First dose of BNT162b2 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.03 | – | 0.01 | −0.76 | 0.4487 | |

| Second dose of BNT162b2 | 0.23 | 0.07 | 0.10 | – | 0.36 | 3.46 | 0.0005 | *** |

| Marginal effects on the worst lymphadenopathy (outcome 2) |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marginal effects | SE | 95 % CI | t value | p value | |||||||

| Sex (comparison to female) rowhead | |||||||||||

| Male | −0.06 | 0.03 | −0.11 | – | −0.01 | −2.46 | 0.0140 | ** | |||

| Age (comparison to <25 years) rowhead | |||||||||||

| 25–40 years | −0.02 | 0.03 | −0.08 | – | 0.04 | −0.64 | 0.5244 | ||||

| ≥40 years | −0.05 | 0.03 | −0.11 | – | 0.00 | −1.80 | 0.0723 | ||||

| Blood type (comparison to type A) rowhead | |||||||||||

| AB | 0.03 | 0.05 | −0.06 | – | 0.12 | 0.60 | 0.5510 | ||||

| B | 0.02 | 0.03 | −0.04 | – | 0.08 | 0.74 | 0.4595 | ||||

| O | 0.01 | 0.03 | −0.05 | – | 0.07 | 0.29 | 0.7700 | ||||

| Medical history rowhead | |||||||||||

| Asthma | −0.03 | 0.08 | −0.18 | – | 0.13 | −0.32 | 0.7462 | ||||

| Metabolism disorders | 0.01 | 0.06 | −0.10 | – | 0.12 | 0.22 | 0.8234 | ||||

| Allergic reaction to vaccine | −0.06 | 0.07 | −0.19 | – | 0.08 | −0.83 | 0.4055 | ||||

| Smoking (comparison to naive) rowhead | |||||||||||

| Past | 0.04 | 0.03 | −0.03 | – | 0.11 | 1.15 | 0.2506 | ||||

| Current | 0.06 | 0.06 | −0.05 | – | 0.17 | 1.00 | 0.3185 | ||||

| Systemic event rowhead | |||||||||||

| First dose of BNT162b2 | −0.02 | 0.03 | −0.07 | – | 0.03 | −0.83 | 0.4068 | ||||

| Second dose of BNT162b2 | −0.02 | 0.03 | −0.07 | – | 0.04 | −0.54 | 0.5868 | ||||

| Local event rowhead | |||||||||||

| First dose of BNT162b2 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.02 | – | 0.14 | 2.66 | 0.0078 | *** | |||

| Second dose of BNT162b2 | −0.02 | 0.04 | −0.10 | – | 0.06 | −0.53 | 0.5940 | ||||

| Use of antipyretics (comparison to those who did not take any)c rowhead | |||||||||||

| Timing 1 | 0.04 | 0.04 | −0.03 | – | 0.11 | 1.22 | 0.22167 | ||||

| Timing 2 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.03 | – | 0.14 | 3.27 | 0.0011 | *** | |||

| Timing 3 | 0.02 | 0.03 | −0.04 | – | 0.08 | 0.78 | 0.4332 | ||||

| Lymphadenopathy rowhead | |||||||||||

| First dose of BNT162b2 | −0.13 | 0.01 | −0.16 | – | −0.11 | −10.39 | <2.20 × 10−16 | *** | |||

| Second dose of BNT162b2 | 0.35 | 0.07 | 0.21 | – | 0.49 | 5.02 | 5.19 × 10−7 | *** | |||

General properties of the model, Breusch‒Pagan test, R-square 51.86, p = 0.00012, McFadden's pseudo R-square test 0.22, Log-likelihood −346.57.

Statistical significance. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Timing 1, Prior to the third dose of BNT162b2, Timing 2, After the third dose of BNT162b2 but without or before the onset of adverse events, Timing 3, After the onset of adverse events following the second dose of BNT162b2.

3.4.1. The effect of age on adverse events

Those aged 25–40 years were associated with a reduced incidence of systemic events following the second dose, but the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.0530). Following the third dose, those aged 25–40 years experienced more non-worst local events (p = 0.0002) but were less likely to experience the worst local events (p = 0.0002) than those aged <25 years. Those aged 25–40 years also had less non-worst lymphadenopathy following the third dose (p = 2.00 × 10−5). Age ≥40 years was associated with a reduced likelihood of systemic events following the second dose (p = 6.10 × 10−7), was likely to result in fewer local events following the third dose and was less likely to result in the worst local events compared to age <25 years (p = 0.0344 and p = 0.018, respectively). Lymphadenopathy tended to be absent (p = 0.0358) and less likely to be the non-worst event (p = 0.0006) in this older age group. Although age ≥40 years was associated with reduced worst lymphadenopathy, this was not statistically significant (p = 0.0723).

3.4.2. The effect of sex on adverse events

Males were associated with a reduced risk of the worst systemic events following the third dose compared to females (p = 0.0445). Although the mean estimate showed that men were less likely to have systemic events following the second dose than females, this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.15267). Although male sex was associated with an increased likelihood of non-worst local events following the third dose compared with female sex (p = 0.0005), males were less likely to have the worst local event following the third dose (p = 0.0031). Following the third dose, male sex was also associated with the absence of lymphadenopathy (p = 0.0061) and a reduced likelihood of non-worst and worst lymphadenopathy (p = 0.0010 and 0.0140, respectively) compared with female sex.

3.4.3. The effect of history of allergic reaction to previous vaccines on adverse events

A history of allergic reactions to other vaccines was negatively associated with the absence of systemic events and positively associated with the worst systemic event following the third dose (p = 0.0015 and 0.0280, respectively).

3.4.4. The effect of blood type on adverse events

Compared to blood type A, blood type B was associated with a reduced risk of systemic events following the second dose in the mean estimate and was associated with their absence (p = 0.0499 and 0.0248, respectively). Blood types AB, B and O were associated with an increased likelihood of a non-worst local event (p = 2.00 × 10−5, 0.0045 and p = 0.0028, respectively) and a reduced likelihood of the worst local event (p = 0.0001, 0.0061, and 0.0031, respectively). Blood type B was also associated with a reduced likelihood of non-worst lymphadenopathy following the third dose (p = 0.0015).

3.4.5. The effect of asthma on adverse events

Asthma was negatively associated with a non-worst third systemic event (p = 0.0359). The presence of conditions related to fat or glucose metabolism, including type 1 and 2 diabetes mellitus, dyslipidaemia and metabolic syndrome, was not associated with any adverse events.

3.4.6. The effect of smoking on adverse events

Past smokers were associated with a reduced likelihood of local event absence and a reduced likelihood of non-worst lymphadenopathy following the third dose (p = 0.0068 and 0.0038, respectively).

3.4.7. The effect of systemic events following previous doses on adverse events following later doses

The experience of the systemic event group following the first dose was associated with an increased likelihood of systemic events following the second dose (p = 1.46 × 10−12) and the non-worst systemic event following the third dose (p = 0.0359).

Those who experienced the second systemic event were less likely to be free of the third systemic event (p = 2.58 × 10−10) and more likely to have non-worst and worst systemic events and non-worst lymphadenopathy following the third dose (p = 2.00 × 10−5, 0.0006, and 0.0001, respectively).

3.4.8. The effect of local events following previous doses on adverse events following later doses

The experience of the local event group following the first shot was associated with an increased risk of systemic events following the second dose (p = 5.00 × 10−5). Following the third dose, the experience of the local event group was associated with less absence and an increased likelihood of both non-worst and worst lymphadenopathy (p = 0.0015, 1.00 × 10−5, and 0.0078, respectively).

Those who experienced the second local event were less likely to be free of the third systemic event (p = 0.0197) and more likely to have the worst systemic event (p = 0.0077). They were less likely to be local event free (p < 2.20 × 10−16), more likely to have non-worst and worst local events (p < 2.00 × 10−16 and 0.0163, respectively) and tended to have non-worst lymphadenopathy (p = 0.0066).

3.4.9. The effect of antipyretics on adverse events

The use of antipyretics prior to the third dose was associated with a reduced likelihood of non-worst lymphadenopathy (p = 3.39 × 10−6). The use of antipyretics following the third dose of BNT162b2 but without any event or before the onset of an event was positively associated with the systemic event group following the third shot (p = 0.0486), with a reduction in absence and an increase in the non-worst and worst systemic event group following the third dose (p = 0.0006, 0.0033, and 1.37 × 10−6, respectively). The use of antipyretics was also associated with an increase in local events following the third dose (p = 0.0117), a reduced likelihood of the absence of lymphadenopathy and increased worst lymphadenopathy (p = 0.0014 and 0.0011, respectively).

Those who had experienced lymphadenopathy following the first dose tended to lack lymphadenopathy and were less likely to experience the worst lymphadenopathy (p values were <2.00 × 10−16 for both). Those who experienced lymphadenopathy following the second dose were less likely to lack lymphadenopathy (p = 4.80 × 10−11) and more likely to experience non-worst and worst lymphadenopathy (p = 0.0005 and 5.19 × 10−7, respectively).

4. Discussion

Our previous survey-based study on adverse events following the second dose of BNT162b2 showed that systemic adverse events were associated with young age and female sex [14]. This study showed that some adverse events associated with BNT162b2 formed two distinct groups, and subject background (e.g., age, sex, blood type), experiences of adverse events following previous vaccination and some other factors variably affected the adverse events following the third dose of BNT162b2.

The immune response to the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine is age-related [[15], [16], [17]]. In this study, people aged ≥40 years experienced fewer systemic and local events following the second dose than those aged <25 years, which is consistent with another study that reported that systemic reactions such as fatigue, headache, and fever were less likely to occur in an age-dependent manner after the third dose in Japan [1]. This study also showed that those aged ≥25 years were less likely to experience worsening of injection site-related local adverse events and lymphadenopathy following the third booster shots compared to the second dose, but this was not true for other systemic adverse events.

Sex affected adverse events following the third dose; females experienced local and systemic adverse reactions more often than males [1]. We found that females tended to experience intensification of systemic adverse events compared to the second dose. Therefore, it is reasonable to explain to a female vaccine recipient a possible intense reaction following later doses of the vaccine. Sex also affected lymphadenopathy, which showed a similar trend to other systemic adverse events, and females were more likely to experience intensification of lymphadenopathy following the third booster shot compared to the second booster than males.

We found that a history of allergic reaction to other vaccines was positively associated with the worst systemic event and negatively associated with the absence of a systemic event after the third dose. Hence, it is reasonable to provide complete information about possible adverse events to a vaccine recipient with a previous vaccine-related allergic reaction.

In the present study, current smoking did not reduce the risk of adverse events, and only past smoking habits were associated with non-worst lymphadenopathy following the third dose. Other studies showed that current smokers had substantially lower antibody titres than past smokers among SARS-CoV-2-vaccinated people [18,19]. As higher IgG levels are associated with a greater risk of adverse events, current smokers were expected to experience fewer adverse events. These discrepancies warrant further study on the effect of smoking on immune responses.

The effect of blood type on reactogenicity to COVID-19 vaccines is a controversial issue [20,21]. Our results showed that blood type B was associated with a reduced risk of systemic events following the second dose compared with blood type A. We also found that blood types AB, B and O were associated with the non-worst local events but were negatively associated with the worst local event. Blood type B was also associated with a reduced risk of non-worst lymphadenopathy after the third dose. To address this inconsistency, future large-scale studies are needed.

In the present study, the use of antipyretics was associated with systemic and local events, especially in male lymphadenopathy. One explanation is that people who had experienced adverse events were more likely to use antipyretics. However, in the present study, experiences of systemic/local events after the first or second dose were associated with the experiences of adverse reactions after the third dose (especially in lymphadenopathy). Therefore, if the effect of antipyretics is not sufficient, the use of antipyretics can be a confounding factor of adverse events.

Our previous report showed that those who experienced systemic and local adverse events following the first dose were more likely to develop similar adverse events following the second dose [1]. In this study, we found that those who experienced systemic adverse events following the second dose experienced not only more frequent but also worse symptoms than with previous doses. Injection site-related local adverse events have a similar tendency to become more intense but to a lesser extent than systemic adverse events, and it may be appropriate to tell a person with a previous local event that these reactions do not necessarily intensify with successive boosters.

We also found that lymphadenopathy following the first dose was unlikely to occur again following the third dose, while experience of lymphadenopathy following the second dose was associated with the experience of lymphadenopathy after the third dose. Interestingly, only the occurrence rate of lymphadenopathy increases prominently following the third dose. Compared to other adverse events queried in this study, lymphadenopathy could be more objective and may represent the true extent of the immune response, less affected by psychological state, to the vaccine. However, it is also possible that delayed B- and T-cell memory responses cause a particular immune response in lymph nodes. Those with prominent lymph node enlargement following the first dose may have a large number of memory B cells or plasma cells whose IgG can reduce the non-neutralized naked antigen following boosters and therefore result in less naive lymphocyte activation and less lymphadenopathy following boosters. However, the exact mechanism of how the vaccine may cause lymphadenopathy is still not clear [22]. Given the dramatic intensification of lymphadenopathy following the third dose, those who receive three or more doses of boosters should be informed of this reaction before receiving the vaccine even when they have not developed lymphadenopathy following previous doses, especially those who are young or female.

Our study has some limitations. A previous study showed a positive association between immunoglobulin G (IgG) levels and adverse events [23]. Therefore, investigation of the relationship among age, IgG level, and adverse events is important. However, in the present study, IgG titres were not evaluated. During the study period, only thirteen participants reported having had a previous diagnosis of COVID-19, which made us unable to analyse the COVID-19 history as a factor influencing adverse events. Additionally, adverse events were queried based on the internet study form, and there was no way to know what adverse events occurred in those who did not answer, which may have biased this study.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to clarify the association among different adverse events using networks following the first, second, and third doses of BNT162b2. Some adverse events following BNT162b2 formed two main groups: systemic and injection site-related local event groups. While previous experiences of systemic and local events were associated with worse adverse events following the third dose, local adverse events following the third dose were often not worse than those previously experienced. Unlike other adverse events, lymphadenopathy increased sharply following the third booster. It may be appropriate to tell a vaccine candidate who is going to receive three or more boosters that lymphadenopathy may occur even without previous lymphadenopathy following the earlier doses, but local events do not necessarily intensify.

Funding

This study was supported by a Nihon University Research Grant for 2022 (to S.H).

Institutional review board statement

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Nihon University School of Medicine (approval number: P21-06-1). All procedures were performed under the guidelines of our institutional ethics committee and adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed consent statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data availability statement

Data are contained within the article or supplementary material.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Takahiro Namiki: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Kazuhide Takada: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. Satoshi Hayakawa: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition. Shihoko Komine-Aizawa: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. Gotoda T. (Ex-dean of Nihon University School of Medicine), Prof. Ishihara H. (School Principal of Nihon University Nursing School), Prof. Kaneita Y., Prof. Gon Y., Prof. Kawana K., Prof. Nakayama T., Prof. Hao H., Prof. Takayama T., Prof. Takahashi S. (Nihon University School of Medicine), Prof. Toriyama M. (Dean of School of Pharmacy, Nihon University) and Prof. Hayashi H. (School of Pharmacy, Nihon University) for their support during this study. We also thank American Journal Experts for their editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e34347.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Naito T., Tsuchida N., Kusunoki S., Kaneko Y., Tobita M., Hori S., Ito S. Expert review of vaccines; 2022. Reactogenicity and Immunogenicity of BNT162b2 or mRNA-1273 COVID-19 Booster Vaccinations after Two Doses of BNT162b2 Among Healthcare Workers in Japan: a Prospective Observational Study. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mentzer A.J., O'Connor D., Bibi S., Chelysheva I., Clutterbuck E.A., Demissie T., Dinesh T., Edwards N.J., Felle S., Feng S., Flaxman A.L., Karp-Tatham E., Li G., Liu X., Marchevsky N., Godfrey L., Makinson R., Bull M.B., Fowler J., Alamad B., Malinauskas T., Chong A.Y., Sanders K., Shaw R.H., Voysey M., Cavey A., Minassian A., Stuart A., Khozoee B., Hanumunthadu B., Angus B., Smith C.C., Turnbull I., Kwok J., Emary K.R.W., Cifuentes L., Ramasamy M.N., Cicconi P., Finn A., McGregor A.C., Collins A.M., Smith A., Goodman A.L., Green C.A., Duncan C.J.A., Williams C.J.A., Ferreira D.M., Turner D.P.J., Thomson E.C., Hill H., Pollock K., Toshner M., Lillie P.J., Heath P., Lazarus R., Sutherland R.K., Payne R.O., Faust S.N., Darton T., Libri V., Anslow R., Provtsgaard-Morys S., Hart T., Beveridge A., Adlou S., Snape M.D., Pollard A.J., Lambe T., Knight J.C., Oxford C.G. Human leukocyte antigen alleles associate with COVID-19 vaccine immunogenicity and risk of breakthrough infection. Nat. Med. 2022 doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-02078-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Csárdi G., Nepusz T. The igraph software package for complex network research. Computer Science. 2006:1695. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Epskamp S., Cramer A.O.J., Waldorp L.J., Schmittmann V.D., Borsboom D. Qgraph: network visualizations of relationships in psychometric data. J. Stat. Software. 2012;48:1–18. doi: 10.18637/jss.v048.i04. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Borkulo C.D., Borsboom D., Epskamp S., Blanken T.F., Boschloo L., Schoevers R.A., Waldorp L.J. A new method for constructing networks from binary data. Sci. Rep. 2014;4:5918. doi: 10.1038/srep05918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dalege J., Borsboom D., van Harreveld F., van der Maas H.L.J. Network analysis on attitudes: a brief tutorial. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2017;8:528–537. doi: 10.1177/1948550617709827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pons P., Latapy M. Springer; Berlin, Heidelberg: 2005. Computing Communities in Large Networks Using Random Walks. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Breusch T., Pagan A. A simple test for heteroscedasticity and random coefficient variation. Econometrica. 1979;47:1287–1294. doi: 10.2307/1911963. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koenker R. A note on studentizing a test for heteroscedasticity. J. Econom. 1981;17:107–112. doi: 10.1016/0304-4076(81)90062-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alvarez R.M., Brehm J. American ambivalence towards abortion policy: development of a heteroskedastic probit model of competing values. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 1995;39:1055–1082. doi: 10.2307/2111669. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yatchew A., Griliches Z. Specification error in probit models. Rev. Econ. Stat. 1985;67:134–139. doi: 10.2307/1928444. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carroll N. CRAN; 2018. Oglmx: Estimation of Ordered Generalized Linear Models. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zeileis A., Hothorn T. vol. 2. 2002. pp. 7–10. (Diagnostic Checking in Regression Relationships). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Namiki T., Komine-Aizawa S., Takada K., Takano C., Trinh Q.D., Hayakawa S. Adverse events after BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccination in health care workers and medical students in Japan. J. Infect. Chemother. : official journal of the Japan Society of Chemotherapy. 2022;28:1220–1224. doi: 10.1016/j.jiac.2022.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Collier D.A., Ferreira I., Kotagiri P., Datir R.P., Lim E.Y., Touizer E., Meng B., Abdullahi A., Elmer A., Kingston N., Graves B., Le Gresley E., Caputo D., Bergamaschi L., Smith K.G.C., Bradley J.R., Ceron-Gutierrez L., Cortes-Acevedo P., Barcenas-Morales G., Linterman M.A., McCoy L.E., Davis C., Thomson E., Lyons P.A., McKinney E., Doffinger R., Wills M., Gupta R.K. Age-related immune response heterogeneity to SARS-CoV-2 vaccine BNT162b2. Nature. 2021;596:417–422. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03739-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walsh E.E., Frenck R.W., Jr., Falsey A.R., Kitchin N., Absalon J., Gurtman A., Lockhart S., Neuzil K., Mulligan M.J., Bailey R., Swanson K.A., Li P., Koury K., Kalina W., Cooper D., Fontes-Garfias C., Shi P.Y., Türeci Ö., Tompkins K.R., Lyke K.E., Raabe V., Dormitzer P.R., Jansen K.U., Şahin U., Gruber W.C. Safety and immunogenicity of two RNA-based covid-19 vaccine candidates. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;383:2439–2450. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2027906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pérez-Alós L., Armenteros J.J.A., Madsen J.R., Hansen C.B., Jarlhelt I., Hamm S.R., Heftdal L.D., Pries-Heje M.M., Møller D.L., Fogh K., Hasselbalch R.B., Rosbjerg A., Brunak S., Sørensen E., Larsen M.A.H., Ostrowski S.R., Frikke-Schmidt R., Bayarri-Olmos R., Hilsted L.M., Iversen K.K., Bundgaard H., Nielsen S.D., Garred P. Modeling of waning immunity after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination and influencing factors. Nat. Commun. 2022;13:1614. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-29225-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Michos A., Tatsi E.B., Filippatos F., Dellis C., Koukou D., Efthymiou V., Kastrinelli E., Mantzou A., Syriopoulou V. Association of total and neutralizing SARS-CoV-2 spike -receptor binding domain antibodies with epidemiological and clinical characteristics after immunization with the 1(st) and 2(nd) doses of the BNT162b2 vaccine. Vaccine. 2021;39:5963–5967. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.07.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nomura Y., Sawahata M., Nakamura Y., Kurihara M., Koike R., Katsube O., Hagiwara K., Niho S., Masuda N., Tanaka T., Sugiyama K. Age and smoking predict antibody titres at 3 Months after the second dose of the BNT162b2 COVID-19 vaccine. Vaccines. 2021;9 doi: 10.3390/vaccines9091042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Allan J.D., McMillan D., Levi M.L. COVID-19 mRNA vaccination, ABO blood type and the severity of self-reported reactogenicity in a large healthcare system: a brief report of a cross-sectional study. Cureus. 2021;13 doi: 10.7759/cureus.20810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alessa M.Y., Aledili F.J., Alnasser A.A., Aldharman S.S., Al Dehailan A.M., Abuseer H.O., Almohammed Saleh A.A., Alsalem H.A., Alsadiq H.M., Alsultan A.S. The side effects of COVID-19 vaccines and its association with ABO blood type among the general surgeons in Saudi arabia. Cureus. 2022;14 doi: 10.7759/cureus.23628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bshesh K., Khan W., Vattoth A.L., Janjua E., Nauman A., Almasri M., Mohamed Ali A., Ramadorai V., Mushannen B., AlSubaie M., Mohammed I., Hammoud M., Paul P., Alkaabi H., Haji A., Laws S., Zakaria D. Lymphadenopathy post-COVID-19 vaccination with increased FDG uptake may be falsely attributed to oncological disorders: a systematic review. J. Med. Virol. 2022;94:1833–1845. doi: 10.1002/jmv.27599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Otani J., Ohta R., Sano C. Association between immunoglobulin G levels and adverse effects following vaccination with the BNT162b2 vaccine among Japanese healthcare workers. Vaccines. 2021;9 doi: 10.3390/vaccines9101149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article or supplementary material.