Highlights

-

•

Perspective on developing and implementing knowledge-informed data-driven models.

-

•

Knowledge-informed data-driven approach balances model complexity with data size.

-

•

Proposed a framework for knowledge integration based on a priori knowledge status.

-

•

Integrating unstructured knowledge into data-driven models is a challenging task.

Keywords: Modelling, Data-driven, Machine learning, Hybrid model, Urban water systems

Abstract

Mathematical modeling plays a crucial role in understanding and managing urban water systems (UWS), with mechanistic models often serving as the foundation for their design and operations. Despite the wide adoptions, mechanistic models are challenged by the complexity of dynamic processes and high computational demands. Data-driven models bring opportunities to capture system complexities and reduce computational cost, by leveraging the abundant data made available by recent advance in sensor technologies. However, the interpretability and data availability hinder their wider adoption. This paper advocates for a paradigm shift in the application of data-driven models within the context of UWS. Integrating existing mechanistic knowledge into data-driven modeling offers a unique solution that reduces data requirements and enhances model interpretability. The knowledge-informed approach balances model complexity with dataset size, enabling more efficient and interpretable modeling in UWS. Furthermore, the integration of mechanistic and data-driven models offers a more accurate representation of UWS dynamics, addressing lingering uncertainties and advancing modelling capabilities. This paper presents perspectives and conceptual framework on developing and implementing knowledge-informed data-driven modeling, highlighting their potential to improve UWS management in the digital era.

1. Mechanistic and data-driven modelling in urban water systems

Mathematical modelling is an important tool for the design and operation of urban water systems (UWS). Mechanistic models developed from physical, chemical, and biological principles, are often used to describe, and predict the water/wastewater flows and characteristics. The applications of mechanistic models have fruitfully improved the management of UWS. As an excellent example, the activated sludge models (ASMs) have been widely accepted and applied by the water industry to understand, design and optimize biological wastewater treatment processes (Gernaey et al., 2004; Henze et al., 2000). Similarly, Computational Fluid Dynamic (CFD) models have been intensively applied in the hydraulic analysis and design of water and wastewater infrastructures (Samstag et al., 2016). Powerful as they are, mechanistic models are not always available due to inadequate mechanistic knowledge. They could also be overly complex incurring unacceptable computational costs particularly for real-time applications. Further, the modelled physical, chemical and biological processes could be time varying caused by e.g. an evolution of highly complex microbial communities. In these cases, both the model parameters and model structures need to be adapted over time.

Data-driven models are complementary to mechanistic models and have also been widely used for UWS modelling (Fu et al., 2022; Newhart et al., 2019). For example, artificial neural networks have been used for predictive process control in wastewater treatment (Belanche et al., 1999; Hamed et al., 2004; Holubar et al., 2002; Mjalli et al., 2007). Multivariate statistical models, such as principal component analysis (PCA) have been applied in monitoring and fault detection in wastewater treatment (Baggiani and Marsili-Libelli, 2009; Kazor et al., 2016; Rosen and Lennox, 2001). Data-driven models are developed exclusively from data, without requiring mechanistic knowledge. Machine learning enables self-adaptive models, allowing the model to adapt to the evolving changes in environmental and/or operational conditions. In addition, data-driven models can be computationally less demanding than complicated mechanistic models. However, data-driven models are known to be data hungry, requiring comprehensive data for their training. The difficulties in acquiring comprehensive, high-quality datasets from UWS have been a main hurdle for a wider application of data-driven modelling to UWS. In addition, data-driven models are difficult to interpret, hindering their adoption for UWS design and operation.

2. Knowledge-informed data-driven modelling for urban water systems

Recent developments in sensor technologies have enhanced our capability to monitor UWS, and thus more data are being collected. At the same time, pure data-driven models such as large language models have revolutionized many modelling tasks. However, the application of data-driven models to UWS should take a different approach. The physical, chemical, and biological processes in UWS have been extensively studied to date, with a considerable amount of mechanic knowledge generated. While such mechanistic knowledge may not be adequate for the development of full mechanistic models in many cases, it can inform the data-driven modelling. Indeed, data-driven modelling should not be expected to reinvent but incorporate the well-established knowledge. Through integrating knowledge into data-driven modelling, the amount of data required for model training can be substantially reduced, and the resulting model will be simpler and more interpretable. Considering a model with N parameters, the training data space complexity is O(N). By reducing the number of parameters to be learned to a fraction of N (cN, where 0 < c < 1), we effectively reduce the data space complexity to O(Nc). This strategic reduction in parameters, guided by existing scientific knowledge, paves the way for more efficient, interpretable, and effective data-driven modelling in UWS.

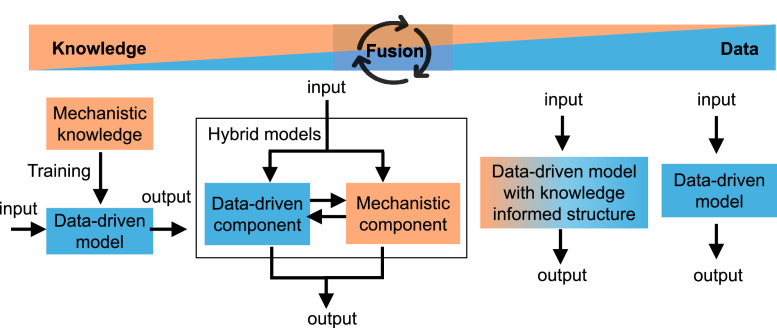

Some pioneering but scattered studies have already demonstrated the strength of integrating a priori knowledge in data-driven modelling. In this work, we propose a conceptual framework for knowledge and data fusion, as illustrated in Fig. 1. Based on the status of the existing knowledge, different levels of knowledge integration can be carried out via different approaches. In cases where comprehensive knowledge is available, data-driven models can be trained to learn from given laws described by well-established mathematical equations, which may be a more efficient surrogate for the full mechanistic models. Less complete knowledge may be captured in mechanistic model components and integrated with data-driven model components to form powerful hybrid models. A priori knowledge that is not wholistically described by mathematical equations may be used to inform data-driven model structure to significantly reduce the number of parameters to be trained and to improve the model performance.

Fig. 1.

A framework of knowledge-informed data-driven modelling for urban water systems.

3. Data-driven modelling of well-understood complex processes

Many physical, chemical and/or biological laws have been embedded in mechanistic models for urban water systems. However, in many cases, the computational requirements of the mechanistic models are too high to be feasibly applied to, e.g. on-line optimization and real-time control. In this case, a data-driven model that is less computationally demanding can be a suitable surrogate, by learning from the underlying mechanistic laws. The a priori knowledge can inform the regularization of the data-driven model as well as to generate data to train the models in lieu of real-life data, which are difficult to collect.

One example is the CFD modelling of water and wastewater systems. The use of CFD by the water industry is constrained by its high demand for computational power and specialized expertise (Samstag et al., 2016). Data-driven models can be trained to learn from given laws described by mathematical equations to solve supervised learning tasks. The so-called Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINN) incorporate the physics embedded in the ordinary or partial differential equations (PDE) into its architecture by appropriately penalizing the loss function (Ji et al., 2021; Raissi et al., 2019). As illustrated in Fig. 2A, the PINN model is essentially a Neural Network (NN) whose training process is guided by physical laws. In the training process, automatic differentiation is firstly employed to compute the derivatives of the NN output with respect to the inputs. The computed derivatives are then aligned with the governing physical equations (PDE or ODE) to calculate the physical loss. The NN is subsequently trained by minimizing not only the physical loss but also the boundary condition (BC) and initial condition (IC) losses. The PINN approach has been successfully applied to solving the Navier–Stokes Equations (PDEs), which accelerated hydrodynamic computations (Eivazi et al., 2022; Raissi et al., 2019; Vinuesa and Brunton, 2022), with superior computational efficiency (milliseconds) and robust predictive capability (Li and Shatarah, 2024).

Fig. 2.

A) A schematic illustration of the Physics Informed Neural Network (PINN). The governing equations guide the training process by determining the residual values of the derivatives in PDEs (or ODEs). The boundary condition (BC) and initial condition (IC) losses are also calculated with actual values. The total loss is then used to train the hyperparameters of NN. B) A schematic illustration of two typical hybrid modelling structures, serial and parallel. C) A simple data-driven methane production model with a knowledge informed model structure. θ is the water surface angle; Q, D, and S are the wastewater flow, the pipe diameter, and the pipe slope, respectively; n is the Manning's roughness coefficient;is the methane production rate at ; are parameters to be learnt. D) A knowledge-informed structure of a data-driven model predicting soil temperature influenced by heat transfer from a buried sewer pipe.

A similar approach has also been applied to wastewater treatment processes (Li et al., 2024; Zou et al., 2023). A recent study showed that a PINN model trained using ODEs from an uncalibrated Activated Sludge Model No.1 achieved significantly better performance than the NN models without physics (Li et al., 2024). In addition to neural networks, the knowledge-informed principal can also be applied to other data-driven approaches. For example, Li et al. (2022a) developed swift data-driven hydraulic models using data generated by the Saint-Venant Equations (SVE). The swift models reproduced the SVE predictions with high fidelities, with a fraction of the computational time.

4. Hybrid modeling of less-understood processes

For some systems in the UWS, the physical, chemical and/or biological mechanisms are well understood for some processes but not for all. Such system can be modelled using a hybrid modelling approach that effectively integrates mechanistic and data-driven modelling. With the data-driven models revealing the intricacies of these yet-to-be-fully-understood processes, the strategic integration of data-driven models with mechanistic counterparts offers a more accurate representation of the complex UWS system (Abba et al., 2020; Kazemi et al., 2021; Li et al., 2022b; Quaghebeur et al., 2022; Schneider et al., 2022). For example, Li et al. (2022b) developed a serial hybrid model to predict the generation of nitrous oxide (N2O) in a biological wastewater treatment plant. In this model, the well-established ASM1 was used to predict concentrations of nitrite, ammonium, and oxygen, among other variables, which provided input for a deep-learning model to predict the N2O production, the mechanism of which is not fully understood at present. The model outperformed a mechanistic model with assumed mechanisms and a purely data-driven deep learning model. Equally importantly, the hybrid model required less data for training than the purely data-driven model.

The hybrid model can have various integration structures, offering flexibility to tailor the model according to specific objectives and existing mechanistic models. Among these structures, two common ones are serial and parallel configurations, as illustrated in Fig. 2B. The serial structure is particularly useful for modelling systems with ambiguous processes that lack model descriptions. Within serial hybrid models, there is a clear separation of known and unknown processes. The sequence of mechanistic and data-driven components can be adjusted interchangeably based on the modeling context. Conversely, parallel hybrid models find applicability in scenarios where a mechanistic model is available but exhibits unsatisfactory predictive performance (Sansana et al., 2021). In the parallel structure, the data-driven component learns discrepancies between the mechanistic model and observations, thereby capturing unmodeled effects. While a parallel structure can well accommodate mismatches, a serial structure is generally preferred when the existing mechanistic model is sufficiently accurate (von Stosch et al., 2014). It is worth noting that integration can take on various forms beyond just serial or parallel configurations.

5. Incorporating incomplete, unstructured knowledge in data-driven modelling

In many cases, the a priori knowledge is incomplete, scattered, not wholistically described by mathematical equations, and in some cases appears to be qualitative. The integration of such unstructured knowledge is challenging, requiring creative thinking. Several examples are available that are inspiring for the development of full methodologies for the integration of unstructured knowledge into data-driven modelling.

A simple example: The quantification of the emission of methane (CH4), a potent greenhouse gas, from sewer networks is a challenging task, as sewer networks are distributed systems spreading across a city with methane emitted wherever an air/water interface is present. Consequently, quantification through monitoring is unrealistic. Instead, modelling becomes a more feasible solution. It is well-established that CH4 is primarily produced by sewer biofilms, which is determined by the water surface angle within the sewers (Fig. 2C). Therefore, the mathematical knowledge of sewer pipe geometry informed the structure of a CH4 production model (Fig. 2C, Willis (2017)), which considers key influencing factors such as the wastewater flow rate (Q), the sewer pipe diameter (D) and slope (S). Willis (2017) estimated all four parameters involved in the structure using data generated with a fully calibrated mechanistic sewer model, yielding a simple reliable knowledge-informed data-driven model for estimating CH4 emissions from sewer networks.

A more involved example: Li et al. (2023) developed an empirical model to predict the soil temperature impacted by heat transfer from a buried sewer pipe. The proposed model structure comprised two multiplied terms (Fig. 2D). The first term is the known analytic solution of the 1D heat transfer equation for a sinusoidal heat source (with a frequency of ) at a flat plate surface. This would be the full solution if the pipe radius R were infinitely large. Recognising that R is always limited, the second term was included to model the impact of the curvature on the heat transfer solution (Fig. 2D), which was to be learnt from data. This formed a hybrid model structure. For the second term, Li et al. (2023) adopted a knowledge-informed structure, rather than a general neural network structure. Inspired by the pipe geometry, a new variable δ/(δ+R) was created and incorporated in the model as a key variable (Fig. 2D). This resulted in a data-driven model component that adequately captures the impact of curvature by training just two parameters. Employing a NN-based model would have involved far more parameters and demanded a much larger dataset for training.

6. Challenges and opportunities

In this perspective, we acknowledge that both mechanistic models and data-driven models possess distinct strengths and limitations (Table S1). We believe that the integration of these approaches, i.e. knowledge-informed data-driven modelling, represents a promising tool to effectively address emerging challenges in urban water systems. However, the development and implementation of knowledge-informed data-driven modelling has its own challenges (Table S1). There is a pressing need for a comprehensive framework and effective tool to enable the systematic fusion of knowledge and data. It is particularly challenging to incorporate incomplete, unstructured knowledge into data-driven modelling. In both examples outlined in Section 5, human experts contributed knowledge, while machines played limited roles in (1) determining parameter values for the knowledge-informed model structures, and (2) executing mechanistic models to generate data for training data-driven models. The heavy reliance on human experts renders the model development tedious, labour intensive and task specific. A crucial aspect for a more universally applicable approach lies in empowering machines to autonomously acquire domain knowledge—a task made increasingly feasible by the emergence and rapid advancement of large language models. Additionally, developing a more universally applicable approach requires effective integration of specific domain knowledge and data. In the examples provided, a particular model structure was proposed based on domain knowledge, with parameters determined through a training process. However, such an approach may only be applicable to limited application scenarios. In most cases, model structures may not readily emerge from fragmented knowledge. It remains an open question how such knowledge can be systematically fused into the data-driven modelling processes.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Haoran Duan: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Conceptualization. Jiuling Li: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Conceptualization. Zhiguo Yuan: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

Haoran Duan is a recipient of the Australian Research Council (ARC) Early Career Industry Fellowship IE230100422. Jiuling Li acknowledges the Sewer Monitoring and Management in the Digital Era project LP210300584 and Reducing Sewer Corrosion through Model-supported Ventilation Control Project LP190101262, funded by the ARC, and the UQ Digital Water Initiative funded by The University of Queensland. Zhiguo Yuan is a Global STEM Professor jointly funded by the Innovation, Technology and Industry Bureau (“ITIB”) and Education Bureau (“EDB”) of the Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China and acknowledges financial support from the Hong Kong Jockey Club for the JC STEM Lab of Sustainable Urban Water Management.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.wroa.2024.100234.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

Data availability

No data was used for the research described in the article.

References

- Abba S.I., Pham Q.B., Saini G., Linh N.T.T., Ahmed A.N., Mohajane M., Khaledian M., Abdulkadir R.A., Bach Q.-V. Implementation of data intelligence models coupled with ensemble machine learning for prediction of water quality index. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020;27(33):41524–41539. doi: 10.1007/s11356-020-09689-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baggiani F., Marsili-Libelli S. Real-time fault detection and isolation in biological wastewater treatment plants. Water Sci. Technol. 2009;60(11):2949–2961. doi: 10.2166/wst.2009.723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belanche L.s.A., Valdés J.J., Comas J., Roda I.R., Poch M. Towards a model of input–output behaviour of wastewater treatment plants using soft computing techniques. Environ. Modell. Softw. 1999;14(5):409–419. [Google Scholar]

- Eivazi H., Tahani M., Schlatter P., Vinuesa R. Physics-informed neural networks for solving Reynolds-averaged Navier–Stokes equations. Physics of Fluids. 2022;34(7) [Google Scholar]

- Fu G., Jin Y., Sun S., Yuan Z., Butler D. The role of deep learning in urban water management: a critical review. Water Res. 2022;223 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2022.118973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gernaey K.V., van Loosdrecht M.C., Henze M., Lind M., Jørgensen S.B. Activated sludge wastewater treatment plant modelling and simulation: state of the art. Environ. Modell. Softw. 2004;19(9):763–783. [Google Scholar]

- Hamed M.M., Khalafallah M.G., Hassanien E.A. Prediction of wastewater treatment plant performance using artificial neural networks. Environ. Modell. Softw. 2004;19(10):919–928. [Google Scholar]

- Henze M., Gujer W., Mino T., Van Loosdrecht M. IWA publishing; 2000. Activated Sludge Models ASM1, ASM2, ASM2d and ASM3. [Google Scholar]

- Holubar P., Zani L., Hager M., Fröschl W., Radak Z., Braun R. Advanced controlling of anaerobic digestion by means of hierarchical neural networks. Water Res. 2002;36(10):2582–2588. doi: 10.1016/s0043-1354(01)00487-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji W., Qiu W., Shi Z., Pan S., Deng S. Stiff-PINN: physics-informed neural network for stiff chemical kinetics. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2021;125(36):8098–8106. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpca.1c05102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazemi P., Bengoa C., Steyer J.-P., Giralt J. Data-driven techniques for fault detection in anaerobic digestion process. Process Safety Environ. Protecti. 2021;146:905–915. [Google Scholar]

- Kazor K., Holloway R.W., Cath T.Y., Hering A.S. Comparison of linear and nonlinear dimension reduction techniques for automated process monitoring of a decentralized wastewater treatment facility. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2016;30(5):1527–1544. [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Shatarah M. Operator learning for urban water clarification hydrodynamics and particulate matter transport with physics-informed neural networks. Water Res. 2024;251 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2024.121123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Spelman D., Sansalone J. Unit Operation and Process Modeling with Physics-Informed Machine Learning. J. Environ. Eng. 2024;150(4) [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Mohamad N.N.N., Sharma K., Yuan Z. Establishing boundary conditions in sewer pipe/soil heat transfer modelling using physics-informed learning. Water Res. 2023;244 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2023.120441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Sharma K., Li W., Yuan Z. Swift hydraulic models for real-time control applications in sewer networks. Water Res. 2022;213 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2022.118141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li K., Duan H., Liu L., Qiu R., van den Akker B., Ni B.-J., Chen T., Yin H., Yuan Z., Ye L. An Integrated First Principal and Deep Learning Approach for Modeling Nitrous Oxide Emissions from Wastewater Treatment Plants. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022;56(4):2816–2826. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.1c05020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mjalli F.S., Al-Asheh S., Alfadala H.E. Use of artificial neural network black-box modeling for the prediction of wastewater treatment plants performance. J. Environ. Manage. 2007;83(3):329–338. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newhart K.B., Holloway R.W., Hering A.S., Cath T.Y. Data-driven performance analyses of wastewater treatment plants: a review. Water Res. 2019;157:498–513. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2019.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quaghebeur W., Torfs E., De Baets B., Nopens I. Hybrid differential equations: integrating mechanistic and data-driven techniques for modelling of water systems. Water Res. 2022;213 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2022.118166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raissi M., Perdikaris P., Karniadakis G.E. Physics-informed neural networks: a deep learning framework for solving forward and inverse problems involving nonlinear partial differential equations. J Comput Phys. 2019;378:686–707. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen C., Lennox J.A. Multivariate and multiscale monitoring of wastewater treatment operation. Water Res. 2001;35(14):3402–3410. doi: 10.1016/s0043-1354(01)00069-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samstag R.W., Ducoste J.J., Griborio A., Nopens I., Batstone D.J., Wicks J.D., Saunders S., Wicklein E.A., Kenny G., Laurent J. CFD for wastewater treatment: an overview. Water Science and Technology. 2016;74(3):549–563. doi: 10.2166/wst.2016.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sansana J., Joswiak M.N., Castillo I., Wang Z., Rendall R., Chiang L.H., Reis M.S. Recent trends on hybrid modeling for Industry 4.0. Comput Chem Eng. 2021;151 [Google Scholar]

- Schneider M.Y., Quaghebeur W., Borzooei S., Froemelt A., Li F., Saagi R., Wade M.J., Zhu J.-J., Torfs E. Hybrid modelling of water resource recovery facilities: status and opportunities. Water Sci. Technol. 2022;85(9):2503–2524. doi: 10.2166/wst.2022.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinuesa R., Brunton S.L. Enhancing computational fluid dynamics with machine learning. Nat. Comput. Sci. 2022;2(6):358–366. doi: 10.1038/s43588-022-00264-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Stosch M., Oliveira R., Peres J., Feyo de Azevedo S. Hybrid semi-parametric modeling in process systems engineering: past, present and future. Comput Chem Eng. 2014;60:86–101. [Google Scholar]

- Willis, J. 2017. GHG Methodologies for Sewer CH4, Methanol-Use CO2, and Biogas-Combustion CH4 and their Significance for Centralized Wastewater Treatment.

- Zou X., Guo H., Jiang C., Nguyen D.V., Chen G.-H., Wu D. Physics-informed neural network-based serial hybrid model capturing the hidden kinetics for sulfur-driven autotrophic denitrification process. Water Res. 2023;243 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2023.120331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No data was used for the research described in the article.