Abstract

Background:

The Vitamin A Laboratory-External Quality Assessment (VITAL-EQA) program operated by the CDC provides analytical performance assessment to low-resource laboratories conducting serum vitamins A (VIA), D (VID), B-12 (B12), and folate (FOL), as well as ferritin (FER) and CRP measurements for public health studies.

Objectives:

We aimed to describe the long-term performance of VITAL-EQA participants from 2008 to 2017.

Methods:

Participating laboratories received 3 blinded serum samples biannually for duplicate analysis over 3 d. We assessed results (n = 6) for relative difference (%) from the CDC target value and imprecision (% CV) and conducted descriptive statistics on the aggregate 10-year and round-by-round data. Performance criteria were based on biologic variation and deemed acceptable (optimal, desirable, or minimal performance) or unacceptable (less than minimal performance).

Results:

Thirty-five countries reported VIA, VID, B12, FOL, FER, and CRP results from 2008–2017. The proportion of laboratories with acceptable performance ranged widely by round: VIA 48%–79% (for difference) and 65%–93% (for imprecision), VID 19%–63% and 33%–100%, B12 0%–92% and 73%–100%, FOL 33%–89% and 78%–100%, FER 69%–100% and 73%–100%, and CRP 57%–92% and 87%–100%. On aggregate, ≥60% of laboratories achieved acceptable differences for VIA, B12, FOL, FER, and CRP (only 44% for VID), and over 75% of laboratories achieved acceptable imprecision for all 6 analytes. Laboratories participating continuously in 4 rounds (2016–2017) showed generally similar performance compared to laboratories participating occasionally.

Conclusions:

Although we observed little change in laboratory performance over time, on aggregate, >50% of the participating laboratories achieved acceptable performance, with acceptable imprecision being achieved more often than acceptable difference. The VITAL-EQA program is a valuable tool for low-resource laboratories to observe the state of the field and track their own performance over time. However, the small number of samples per round and the constant changes in laboratory participants make it difficult to identify long-term improvements.

Keywords: folate, inflammation marker, iron status indicator, low-resource laboratory, quality assessment, vitamin A, vitamin B12, vitamin D

Introduction

Micronutrient deficiencies, especially those due to dietary deficiencies of vitamins and minerals are common, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Pregnant women and young children are among the most vulnerable groups as these deficiencies affect fetal and child growth, cognitive development, and resistance to infection [1]. The Vitamin A Laboratory-External Quality Assessment (VITAL-EQA) program, an external quality assessment program for laboratory performance operated by the CDC, was launched in 2003 to fill a basic need for the international laboratory community conducting serum vitamin A (VIA) analyses for public health studies. Laboratories in LMICs or those providing laboratory measurement services for LMICs did not have access to practical and affordable EQA programs prior to that point, nor was their performance documented in the scientific literature. In 2006, the CDC expanded the program to offer assessments for additional serum micronutrients, including folate (FOL), vitamin B-12 (B12), vitamin D (VID), ferritin (FER), soluble transferrin receptor (TFR), and CRP.

The VITAL-EQA program provides method performance assessments to gauge analytical imprecision and magnitude of difference from CDC target values. The methods used to assign the target values are the same methods utilized to measure nutritional biomarkers in the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). Three levels of serum quality control materials prepared by the CDC are sent to laboratories biannually to monitor their long-term performance and to help improve assay performance. Since 2008, the evaluation criteria for acceptable imprecision and difference were based on analyte-specific biologic variation derived from multiple measurements in the same individual (CVi, used to assess method imprecision) as well as in different individuals (CVg, used in addition to CVi to assess method difference). Acceptable performance was reached when the laboratory met optimal, desirable, or minimum performance criteria, whereas meeting less than minimum performance criteria was deemed unacceptable.

In a previous report we presented VITAL-EQA findings for laboratories measuring VIA from 2003–2006 (rounds 1–6) [2]. In this report we summarize VITAL-EQA data for the 10-year period from 2008–2017 (rounds 10–29) when multiple micronutrient biomarkers were featured in the program and performance assessments were based on biologic variation. The report documents the laboratory performance for selected water-soluble vitamins (FOL and B12), fat-soluble vitamins (VIA and VID), and iron status (FER) and inflammation (CRP) markers and highlights the challenges with operating such an international program. It also features limited information for TFR due to the small number of participating laboratories and known issues with large assay differences [3].

Methods

Participating laboratories

Eligibility to participate in the program was based on the laboratory’s public health related work, including governmental and nongovernmental entities (e.g., academic or nonprofit entities) from LMICs or those providing laboratory measurement services for LMICs. Many participants were enrolled through their contacts with the CDC International Micronutrient Malnutrition Prevention and Control program, which facilitated laboratory preparedness for national population health and nutrition surveys.

Specimens

We used serum specimens from various US-based blood banks, such as Solomon Park Research Laboratories, Tennessee Blood Services, and BioIVT. All donor serum units were screened for micronutrient concentrations and 2–4 unmodified serum units were pooled to create blended pools at different concentrations. The pools were divided into aliquots in prelabeled vials with 7-digit coded, random number IDs.

Specimen shipment

Two rounds were executed every year: one spring round in April (data due in June) and one fall round in October (data due in December). Specimens were packed on dry ice or ice packs for shipment to participating laboratories in different countries. To accommodate them as much as possible, shipments were either conducted in April to contain both the spring and fall rounds together, or separately in April and October. Each round consisted of 3 pools (3 vials per pool, 1 mL serum per vial).

Participant sample analysis

Each pool was analyzed in duplicate over 3 d for a total of 6 results. For each pool, the 3 vials were identified as “Day 1,” “Day 2,” and “Day 3.” Each day’s vials were packed randomly such that the 3 pools would not be in the same order across the 3 analysis days. The 7-digit number on each vial allowed vials to remain blinded, thereby preventing the participating laboratory from anticipating the expected value of any vial by appearance.

CDC evaluation of participant results for round-specific performance report

For each pool, the mean of all 6 results was compared to the CDC target value to obtain the relative difference calculated as [(Participant Mean Concentration – CDC Target Concentration) / CDC Target Concentration] × 100. The SD of all 6 results was used to obtain imprecision (% CV) calculated as (Participant SD / Participant Mean Concentration) × 100. For each pool, the difference and the imprecision were scored as Optimal, Desirable, Minimal, or Unacceptable based on the calculated biologic variation acceptance criteria (Table 1) [4]. Using VIA as an example, the acceptable imprecision for optimal, desirable, and minimal CV is <2.4% (calculated as 0.25 × 9.5), <4.8% (calculated as 0.5 × 9.5), and <7.1% (calculated as 0.75 × 9.5), respectively, whereas an unacceptable CV is ≥7.1%. CDC compiled a report with this performance information and returned it to the participating laboratories at the end of each round. Individual laboratory data were shared only with personnel designated in the registration form to receive the reports or with additional stakeholders after consulting with and obtaining approval from the participating laboratory.

Table 1.

Acceptance criteria based on biologic variation applied to each VITAL-EQA round1

| Analyte | Rounds | Biologic Variation2 CV (%)(Reference) | Allowable Difference to Target3 (%) | Allowable Imprecision4 (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Within-Individual | Between-Individual | Optimal | Desirable | Minimum | Optimal | Desirable | Minimum | ||

| VIA | 10–29 | 9.5 (5) | 30.7 (5) | <±4.0 | <±8.0 | <±12.1 | <2.4 | <4.8 | <7.1 |

| VID | 10–11 | 7.25 | 40.16 | <±5.1 | <±10.2 | <±15.3 | <1.8 | <3.6 | <5.4 |

| 12–29 | 11.3 (5) | 37.9 (5) | <±4.9 | <±9.9 | <±14.8 | <2.8 | <5.7 | <8.5 | |

| FOL | 10–29 | 22.6 (5) | 64.3 (5) | <±8.5 | <±17.0 | <±25.6 | <5.7 | <11.3 | <17.0 |

| B12 | 10–29 | 13.4 (5) | 41.6 (5) | <±5.5 | <±10.9 | <±16.4 | <3.4 | <6.7 | <10.1 |

| FER | 10–29 | 14.9 (6) | 100.9 (6) | <±12.7 | <±25.5 | <±38.2 | <3.7 | <7.5 | <11.2 |

| TFR | 10–29 | 11.3 (7) | 42.2 (8) | <±5.5 | <±10.9 | <±16.4 | <2.8 | <5.7 | <8.5 |

| CRP | 10–29 | 49.2 (6) | 77.9 (6) | <±11.5 | <±23.0 | <±34.6 | <12.3 | <24.6 | <36.9 |

B12, serum vitamin B12; CRP, serum C-reactive protein; FER, serum ferritin; FOL, serum folate; VIA, serum vitamin A; VID, serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D; VITAL-EQA, Vitamin A Laboratory-External Quality Assessment.

Analyte variation expressed as CV (%) within individuals (CVi) and between individuals (CVg).

Laboratory performance criteria for difference to CDC target were calculated using a formula that includes CVi and CVg: [Performance factor × ]; performance factors for acceptable difference: 0.125 (optimal performance), 0.25 (desirable performance), and 0.375 (minimum performance); results exceeding the minimum acceptable performance were unacceptable.

Laboratory performance criteria for imprecision were calculated using only CVi: [Performance factor × CVi]; performance factors for acceptable imprecision: 0.25 (optimal performance), 0.50 (desirable performance), and 0.75 (minimum performance); results exceeding the minimum acceptable performance were unacceptable.

Personal communication between Lars Ovesen, Danish Institute for Food and Veterinary Research, and Rosemary Schleicher, CDC, December 19, 2007.

CDC in-house data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2000–2006.

We mostly used the same analyte-specific biologic variation values (CVi and CVg) during the 2008–2017 study period [5-8]. In each round, data were evaluated as reported without applying outlier testing. Data points were removed from consideration only if the laboratory specified a data point was in error or if the reported data were nonnumerical (values reported as “<” or “>”) and could not be assessed. Because TFR assays are not standardized due to the lack of accepted international reference materials, participating laboratories were scored only for imprecision and not for difference from the CDC target values. However, they received information on the CDC target values in early rounds and on their difference from the target values in rounds 25–29 for informational purposes.

CDC target values

We established pool target values for VIA using HPLC-UV [9], for VID using HPLC-MS/MS [10], for FOL using microbiologic assay [11], and for B12, FER, TFR, and CRP using commercial Roche kits on Roche clinical analyzers [12-15). Each target value assignment had a minimum of 6 characterization runs, using a fresh vial each day for duplicate analysis (n ≥ 12). Periodic target value reassignments were conducted if analytical changes were implemented. All VITAL-EQA specimens were stored frozen at the CDC at approximately −70°C. Target values assigned to each pool used in each round are shown in Supplementary Table 1.

The CDC methods were regularly evaluated against metrologically traceable reference materials from agencies such as the National Institute of Standards and Technology and the National Institute for Biological Standards and Control (Table 2). When CDC transitioned to a new method, a cross-over comparison was conducted to assess method differences.

Table 2.

Performance of CDC methods with international reference materials during the 2008–2017 study period1

| Analyte (Unit) | CDC Method | Reference Material | Target Value | Mean ± SD Difference to Target (%), [n] | Performance Score2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VIA μg/dL) | HPLC-UV | NIST SRM 968c Level 1 | 84.1 | 2.4 ± 6.3, [45] | Optimal |

| NIST SRM 968c Level 2 | 48.4 | 2.1 ± 4.4, [44] | Optimal | ||

| NIST SRM 968e Level 1 | 34.1 | 0.6 ± 7.0, [198] | Optimal | ||

| NIST SRM 968e Level 2 | 48.2 | 1.3 ± 6.4, [199] | Optimal | ||

| NIST SRM 968e Level 3 | 64.7 | −1.5 ± 6.4, [198] | Optimal | ||

| VID (nmol/L) | HPLC-MS/MS3 | NIST SRM 972 Level 1 | 61.1 | 0.9 ± 7.1, [158] | Optimal |

| NIST SRM 972 Level 2 | 34.9 | 0.5 ± 7.3, [156] | Optimal | ||

| NIST SRM 972 Level 3 | 110 | 0.9 ± 5.5, [155] | Optimal | ||

| NIST SRM 972 Level 4 | 88.1 | −1.6 ± 5.6, [150] | Optimal | ||

| NIST SRM 972a Level 1 | 73.1 | 0.7 ± 5.6, [303] | Optimal | ||

| NIST SRM 972a Level 2 | 47.1 | 0.4 ± 5.7, [307] | Optimal | ||

| NIST SRM 972a Level 3 | 81.8 | 1.6 ± 6.2, [313] | Optimal | ||

| NIST SRM 972a Level 4 | 74.7 | −1.8 ± 5.7, [325] | Optimal | ||

| FOL (nmol/L) | MBA4 | NIST SRM 1955 Level 1 | 4.7 | 6.6 ± 11.6, [96] | Optimal |

| NIST SRM 1955 Level 2 | 10.7 | 4.7 ± 10.1, [98] | Optimal | ||

| NIST SRM 1955 Level 3 | 37.4 | 3.1 ± 8.9, [96] | Optimal | ||

| NIBSC 03/178 | 10.5 | 6.1 ± 10.9, [95] | Optimal | ||

| B12 (pg/mL) | Roche immunoassay5 | NIBSC 03/178 | 480 | 7.2 ± 4.8, [35] | Desirable |

| FER (ng/mL) | Roche immunoassay6 | NIBSC 94/572 1:10 | 630 | 3.6 ± 5.5, [39] | Optimum |

| NIBSC 94/572 1:20 | 315 | 1.6 ± 4.3, [29] | Optimum | ||

| NIBSC 94/572 1:40 | 157.5 | −0.8 ± 4.3, [29] | Optimum | ||

| NIBSC 94/572 1:100 | 63 | −0.7 ± 9.4, [36] | Optimum | ||

| CRP (mg/L) | Roche immunoassay7 | ERM-DA470 | 39.2 | −14 ± 0.1, [5] | Desirable |

| ERM-DA472 | 41.8 | −13 ± 0.0, [14] | Desirable | ||

| ERM-DA-474 | 41.2 | −10 ± 0.0, [8] | Optimum | ||

| NIBSC 85/506 | 100 | −7.2 ± 0.0, [6] | Optimum | ||

| TFR (mg/L) | Roche immunoassay8 | NIBSC 07/202 neat | 60.59 | 1.7 ± 5.2, [22] | n/a |

| NIBSC 07/202 1:2 | 30.3 | 0.84 ± 4.7, [22] | n/a | ||

| NIBSC 07/202 1:4 | 15.1 | 7.2 ± 6.1, [22] | n/a | ||

| NIBSC 07/202 1:8 | 7.56 | 9.2 ± 8.0, [22] | n/a | ||

| NIBSC 07/202 1:16 | 3.78 | 6.5 ± 9.6, [22] | n/a |

B12, serum vitamin B12; CRP, serum C-reactive protein; ERM, European Reference Materials; FER, serum ferritin; FOL, serum folate; MBA, microbiologic assay; NIBSC, National Institute for Biological Standards and Control; VIA, serum vitamin A; VID, serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D.

CDC mean difference is scored based on biologic variation criteria presented in Table 1.

CDC HPLC-MS/MS total VID was the sum of 25-hydroxyvitamin D2 and 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 from 2010 to 2017 (method separates 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 from epimer of 25-hydroxyvitamin D3). NIST target values shown do not include epimer of 25-hydroxyvitamin D3.

Target values shown are NIST values for total folate minus the amount of MeFox, an oxidation product of 5-methyltetrahydrofolate to which the MBA does not respond.

Roche Elecsys Vitamin B12 electrochemiluminescence immunoassay “ECLIA” was performed on E-170 platform from July 2009 to June 2016 and on e601 platform from July 2016 to the end of 2017.

Roche Tina-quant Ferritin immunoturbidimetric assay performed on Hitachi 912 platform from 2008 to mid-2009; Roche Elecsys Ferritin electrochemiluminescence immunoassay performed on E-170 platform from mid-2009 to mid-2016 and on e601 platform from mid-2016 to end-2017.

Roche Tina-quant CRPLX immunoturbidimetric assay performed on Hitachi 912 platform during 2008 to mid-2009; Roche Tina-quant CRPL3 immunoturbidimetric assay performed on Mod P platform from mid-2009 to mid-2016 and on c501 platform from mid-2016 to end-2017.

Roche Tina-quant Soluble Transferrin Receptor immunoturbidimetric assay performed on Hitachi 912 platform during 2008, on Mod P platform from mid-2009 to mid-2016, and on c501 platform from mid-2016 to end-2017.

WHO assigned a value of 21.74 mg/L to the Reference Reagent based on a theoretical extinction coefficient and the molecular weight (3); CDC characterized the Reference Reagent during 2008 over multiple days and dilutions and obtained a mean ± SD value of 60.5 ± 0.5 mg/L using the Roche Hitachi 912 clinical analyzer; this value has been used to monitor for potential shifts in the TFR assay over time.

Statistical analysis

To maintain the confidentiality of participating laboratories, performance data were not analyzed or presented for individual laboratories. Furthermore, the extent of participation varied for each laboratory (≥1 round during the period covered), and therefore, shifts over time in overall performance could reflect a changing laboratory composition. Using data collected from rounds 10–29, we evaluated laboratory performances as an aggregate over the 10-y period and separately by round. We considered results categorized as optimal, desirable, and minimal as acceptable performance for both difference and imprecision. The number of acceptable results from all laboratories compared to the total number of results was used to obtain the acceptable performance rate (or proportion of laboratories with acceptable performance) for both difference and imprecision by round and as an aggregate over the 10-y period. To avoid the influence of excessive data points with artificially large relative differences due to a low CRP target value, we also limited our analysis to pools with CRP target values ≥0.9 mg/L, which was the limit of quantitation (3 × limit of detection) during most of the pool characterizations (88% of pools) and represented the limit of quantitation for the CDC assay for most of the 10-year period (16 of 20 rounds). Using the aggregate 10-y data, we estimated descriptive statistics for the difference from CDC target and imprecision with all data points and with far outliers removed (data points >3.0 × IQR). We removed the following proportion of far outliers for difference and imprecision: VIA, 3.32% and 5.32%; VID, 4.35% and 3.47%; B12, 5.67% and 4.31%; FOL, 2.88% and 4.23%; FER, 1.19% and 5.03%; and CRP, 8.32% and 5.54%.

Given that only a small number of laboratories (between 2 and 7) participated with different TFR assays during rounds 10–24, we limited our aggregate statistical difference and imprecision analysis for TFR to the more recent rounds 25–29, where between 9 and 13 laboratories participated per round. Furthermore, considering the well-known and large systematic differences across nonstandardized TFR assays, presenting the mean difference is not meaningful. We therefore stratified our TFR analysis by assay platform and only considered laboratories that specified the platform. We included data for ≥2 laboratories per platform if they participated in ≥2 of 5 rounds. This left us with 3 laboratories using a Roche platform and 4 laboratories using a Siemens BN II platform; we did not include data from 1 laboratory using the Quansys multiplex ELISA and 1 laboratory using a manual sandwich-ELISA.

We conducted a few sensitivity analyses to assess additional questions. First, to investigate whether participating laboratory assay results were concentration-dependent, we limited our analysis to rounds that contained low and/or high pool concentrations. Second, we evaluated differences by broad assay types designating different measurement technologies, such as HPLC, immunoassay/protein binding (IA/PB), or microbiologic assay (MBA). Incomplete and often unavailable information on assay subtypes (i.e., IA/PB platform used by participating laboratories) in combination with a limited amount of data did not allow further categorization. Third, to investigate whether continuous participation compared to sporadic participation had an effect on assay performance, we summarized the results of laboratories with uninterrupted participation during 4 recent rounds (rounds 26–29) compared to all other laboratories participating in those rounds.

Results

Performance of CDC methods with international reference materials

The accuracy of the CDC methods (mean difference to reference material target) over the featured 10-y period was for all analytes within the VITAL-EQA’s optimum acceptable criteria for difference based on biologic variation, with the exception of a small number of materials for VID, B12, and CRP, where a combination of optimum and desirable criteria were met (Table 2). The negative bias of −10% to −14% for CRP was due to material commutability issues and does not apply to patient samples according to the manufacturer (personal communication between Guenther Trefz, Roche Diagnostics, and Christine Pfeiffer, CDC, June 8, 2016). The yearly accuracy performance of the CDC methods demonstrated mostly stable performance over time (VIA, Supplementary Figure 1; VID, Supplementary Figure 2; FOL, Supplementary Figure 3; B12, Supplementary Figure 4; FER, Supplementary Figure 5; and CRP, Supplementary Figure 6). For TFR, we also obtained good stability of the assay over time with a mean difference from the CDC assigned target value of 1.7%–9.2%, depending on the reference material dilution (Table 2). Given that the Roche TFR assay has not been standardized to this reference material and measures nearly 3 times higher than the WHO assigned value of 21.74 mg/L [3], the difference to the original reference material target value cannot be scored using the acceptability criteria based on biologic variation.

Participation

The number of participating laboratories generally showed an upward trend during the 10-y period, with the lowest participation for all analytes in rounds 10 and 11 and the highest in round 28 for most analytes (Figure 1). Thirty-five countries reported results from 2008 to 2017, with typically approximately 20 countries participating with VIA testing per round and ≤pproximately 10 countries each participating with VID, FOL, B12, FER, TFR, and CRP testing per round (Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 1.

VITAL-EQA round-by-round acceptable performance rate for difference and imprecision for vitamin A (VIA, A), vitamin D (VID, B), folate (FOL, C), vitamin B12 (B12, D), ferritin (FER, E), and C-reactive protein (CRP, F) for R10 (2008) to R29 (2017). X-axis annotations on specific rounds indicate the following: 1Round contained data from laboratories reporting results from multiple methods (A–F); 2VID panel: no difference evaluation in R10 and R11, as no reference material available; 3CRP panel: only pools with concentrations ≥0.9 mg/L were included; this was the limit of quantitation for the CDC CRP assay for a majority of rounds (16 out of 20 rounds, including 88% of pools used).

Few laboratories maintained an uninterrupted participation in the program, often cycling in and out to obtain evaluations for an upcoming national health survey or study. Additionally, participants were able to submit biomarker data from multiple assays per round to obtain performance information on the different assays.

Laboratory assays

During rounds 10–29, some participants had changed their analytical instrumentation or the analytical method over time. The VITAL-EQA program captured the assay type for most participants, but details regarding instrument platform or kit manufacturer remained sparsely reported (Supplementary Table 2). The majority of participants used HPLC to measure VIA (88%) and only 4 participants sporadically used HPLC-MS/MS and 1 participant used an IA/PB assay type, specifically to measure retinol binding protein. The most frequently used technique to measure VID was IA/PB (53%), followed by HPLC (25% or 4 participants) and HPLC-MS/MS (20% or 9 participants). The predominant techniques to measure FOL were IA/PB (66%) and MBA (28% or 7 participants). For B12, IA/PB were the primary assays (88%), with a small proportion of results from MBA (8% or 4 participants). Nearly all data for FER and CRP were reported using IA/PB (98% for both analytes), with 2% of participants not reporting any assay information. All participants used an immunoassay to conduct TFR analysis.

Aggregate performance over the 10-year study period

Of the laboratories measuring VIA, 61% met the acceptable difference and 78% met the acceptable imprecision performance criteria. For the other analytes, the aggregate performance rates for acceptable difference and imprecision were: VID 44% and 76%; FOL 60% and 91%; B12 69% and 85%, FER 87% and 88%; CRP (all pools) 68% and 97%; and CRP (pools ≥0.9 mg/L) 69% and 97%. We observed general patterns in difference compared with imprecision with the aggregate 10-year data (Figure 2). A large proportion of data points resided within the minimum acceptable criteria for both difference and imprecision. VIA, VID, FOL, and FER had a notable proportion of unacceptable data points below the minimum criteria for difference (negative bias), whereas CRP had a notable proportion of unacceptable data points above the maximum criteria for difference (positive bias). For all analytes, the majority of impression values were within acceptable limits, with VIA having a notable proportion of data points outside the acceptable imprecision limits.

Figure 2.

VITAL-EQA aggregate performance on imprecision relative to difference for vitamin A (VIA, A), vitamin D (VID, B), folate (FOL, C), vitamin B12 (B12, D), ferritin (FER, E), and C-reactive protein (CRP, F) for R10 (2008) to R29 (2017). Plots show all points reported with no outliers removed (VIA 1113, VID 490, FOL 520, B12 441, FER 756, and CRP 556 (not limited to CRP pools ≥ 0.9 mg/L). Horizontal black line is the minimum acceptable imprecision based on biological variation: VIA 7.1%, VID 8.5%, FOL 17.0%, B12 10.1%, FER 11.2%, and CRP 36.9%. Vertical black lines are the minimum acceptable difference range from CDC target values based on biological variation: VIA ±12.1%, VIT ±14.8%, FOL ±25.6%, B12 ±16.4%, FER ±38.2%, and CRP ±34.6%.

The number of points (rate) within acceptable limits for both imprecision and difference are: VIA 595 (53.5%), VID 174 (35.6%), FOL 303 (58.3%), B12 269 (61.0%), FER 594 (78.6%), and CRP 365 (65.7%). VITAL-EQA, Vitamin A Laboratory-External Quality Assessment.

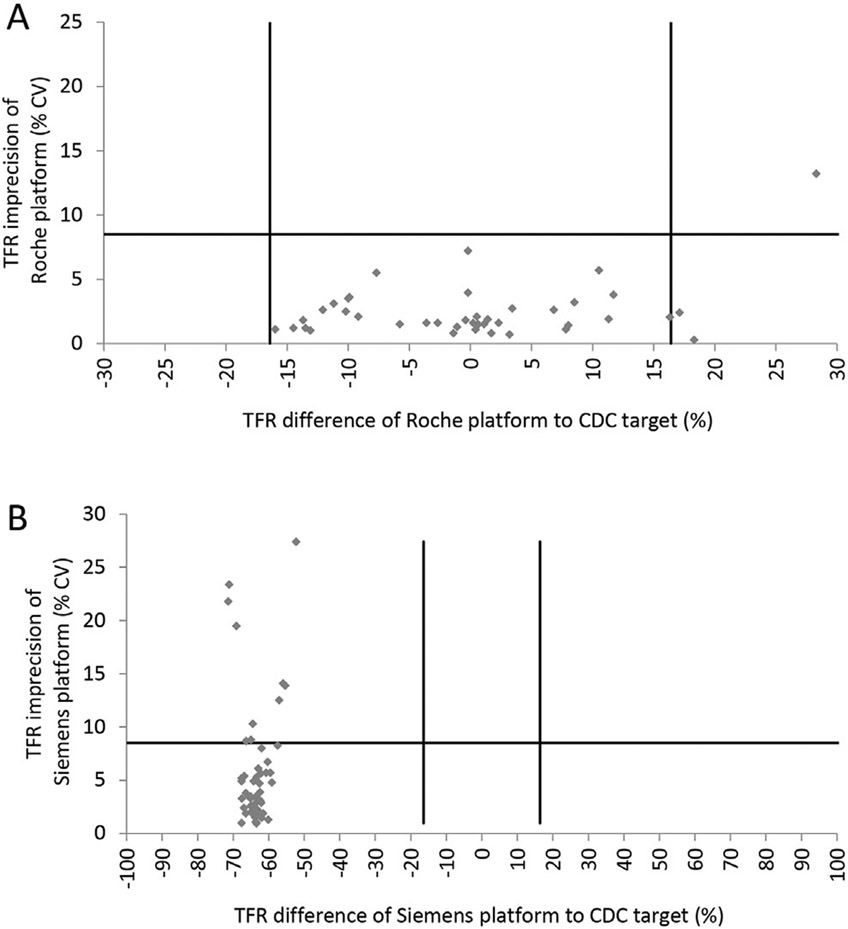

For TFR, the aggregate performance rates for the 2.5-year period (rounds 25–29) for acceptable difference and imprecision were: Roche (93% and 98%) and Siemens BN II (0% and 81%). We observed a broad distribution of data points for the Roche platform (both negative and positive bias, mean bias of 0.1%) compared to a tight distribution of data points for the Siemens BN II platform, indicating a mean negative bias of −63.5% (Figure 3). All but 1 imprecision values were within acceptable limits for the Roche platform (mean imprecision of 2.5%), whereas the Siemens platform had a notable proportion of data points outside the acceptable imprecision limits (mean imprecision of 5.8%).

Figure 3.

VITAL-EQA aggregate performance on imprecision relative to difference for soluble transferrin receptor (TFR) as measured by the Roche (A) or Siemens (B) platform for R25 (2016) to R29 (2017). Plots show all points reported with no outliers removed. Horizontal black line is the minimum acceptable imprecision based on biological variation: TFR 8.5%. Vertical black lines are the minimum acceptable difference range from CDC target values based on biological variation: TFR ±7.7%. VITAL-EQA, Vitamin A Laboratory-External Quality Assessment.

The descriptive statistics for the aggregate 10-year data showed no significant mean percentage difference (95% CI) from CDC target values for VIA [−1.02 (−2.56, 0.51)], FOL [−2.10 (−6.47, 2.26)], and B12 [1.90 (−1.03, 4.84)], whereas VID [10.2 (4.78, 15.6)] and CRP [38.1 (25.7, 50.5)] showed a positive difference and FER [−10.5 (−13.1, −7.85)] a negative difference (Table 3). Removing far outliers had no notable effect on B12 [0.67 (−1.47, 2.80)] and FER [−11.8 (−13.3, −10.4)], whereas the positive difference was reduced for VID [4.80 (1.68, 7.92)] and CRP [11.5 (7.48, 15.5)], and a small negative difference emerged for VIA [−2.62 (−3.58, −1.65)] and FOL [−6.92 (−10.2, −3.65)]. For imprecision, the aggregate 10-year data showed mean CVs ranging from 5.6% (VIA) to 8.9% (FOL). The imprecision decreased by 1–2 percentage points after removing far outliers.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics for aggregate difference from CDC target and imprecision for VITAL-EQA rounds 10–291

| Analyte | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VIA | VID | FOL | B12 | FER | CRP2 | |

| Difference (%) | ||||||

| Minimal acceptable criteria | <±12.1 | <±14.8 | <±25.6 | <±16.4 | <±38.2 | <±34.6 |

| All points included | ||||||

| n | 1113 | 483 | 520 | 441 | 756 | 505 |

| Mean | −1.02 | 10.2 | −2.10 | 1.90 | −10.5 | 38.1 |

| Median | −2.20 | 3.27 | −6.85 | −1.90 | −9.45 | 6.90 |

| Q1 | −10.7 | −15.0 | −26.8 | −11.1 | −22.2 | −6.20 |

| Q3 | 6.3 | 21.2 | 8.90 | 10.9 | −0.28 | 33.5 |

| IQR | 17.0 | 36.2 | 35.7 | 22.0 | 21.9 | 39.7 |

| 5th | −30.6 | −50.4 | −58.2 | −36.5 | −49.9 | −42.7 |

| 95th | 26.2 | 78.8 | 81.8 | 42.8 | 19.2 | 199.9 |

| Lower 95% CI | −2.56 | 4.78 | −6.47 | −1.03 | −13.1 | 25.7 |

| Upper 95% CI | 0.51 | 15.6 | 2.26 | 4.84 | −7.85 | 50.5 |

| Far outliers removed | ||||||

| n | 1076 | 462 | 505 | 416 | 747 | 463 |

| Mean | −2.62 | 4.80 | −6.92 | 0.67 | −11.8 | 11.5 |

| Median | −2.30 | 3.07 | −7.60 | −2.00 | −9.40 | 4.90 |

| Q1 | −10.6 | −14.4 | −26.9 | −10.9 | −21.8 | −7.56 |

| Q3 | 5.60 | 19.2 | 8.20 | 9.38 | −0.4 | 24.8 |

| IQR | 16.2 | 33.6 | 35.1 | 20.3 | 21.4 | 32.3 |

| 5th | −28.4 | −45.4 | −58.0 | −25.0 | −48.8 | −42.3 |

| 95th | 22.5 | 57.2 | 44.9 | 34.7 | 15.7 | 85.9 |

| Lower 95% CI | −3.58 | 1.68 | −10.2 | −1.47 | −13.3 | 7.48 |

| Upper 95% CI | −1.65 | 7.92 | −3.65 | 2.80 | −10.4 | 15.5 |

| Imprecision (%CV) | ||||||

| Minimal acceptable criteria | <7.1 | <8.5 | <17.0 | <10.1 | <11.2 | <36.9 |

| All points included | ||||||

| n | 1110 | 490 | 520 | 441 | 756 | 505 |

| Mean | 5.60 | 8.20 | 8.98 | 6.66 | 6.50 | 8.17 |

| Median | 3.25 | 4.95 | 5.45 | 4.30 | 4.00 | 4.50 |

| Q1 | 1.90 | 2.90 | 3.50 | 2.20 | 2.30 | 2.40 |

| Q3 | 6.20 | 8.28 | 9.13 | 7.20 | 7.00 | 8.70 |

| IQR | 4.30 | 5.38 | 5.63 | 5.00 | 4.70 | 6.30 |

| 5th | 0.90 | 1.30 | 1.30 | 0.70 | 0.90 | 0.71 |

| 95th | 19.3 | 26.7 | 25.1 | 25.3 | 19.1 | 24.6 |

| Lower 95% CI | 5.18 | 7.17 | 7.51 | 5.90 | 5.80 | 7.08 |

| Upper 95% CI | 6.01 | 9.22 | 10.4 | 12.6 | 7.20 | 9.27 |

| Far outliers removed | ||||||

| n | 1051 | 473 | 498 | 422 | 718 | 477 |

| Mean | 4.40 | 7.19 | 6.88 | 5.49 | 4.94 | 5.72 |

| Median | 3.10 | 4.80 | 5.25 | 4.05 | 3.90 | 4.20 |

| Q1 | 1.80 | 2.90 | 3.33 | 2.20 | 2.20 | 2.25 |

| Q3 | 5.60 | 7.90 | 8.40 | 6.48 | 6.30 | 7.70 |

| IQR | 3.80 | 5.00 | 5.08 | 4.28 | 4.10 | 5.45 |

| 5th | 0.90 | 1.27 | 1.30 | 0.70 | 0.90 | 0.58 |

| 95th | 12.3 | 20.7 | 16.8 | 14.5 | 13.4 | 15.6 |

| Lower 95% CI | 4.16 | 6.31 | 6.37 | 4.95 | 4.64 | 5.28 |

| Upper 95% CI | 4.65 | 8.07 | 7.38 | 10.2 | 5.24 | 6.16 |

B12, serum vitamin B12; CRP, serum C-reactive protein; FER, serum ferritin; FOL, serum folate; VIA, serum vitamin A; VID, serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D; VITAL-EQA, Vitamin A Laboratory-External Quality Assessment.

CRP pools featured are those with concentrations ≥0.9 mg/L (limit of quantitation) as measured by the CDC assays; this CRP limit of quantitation (3 × limit of detection) was used for the majority of rounds (16 out of 20 rounds, 88% of the pools); CRP limit of quantitation was 9 mg/L for round 10, 1.3 mg/L for rounds 11–13, and 0.9 mg/L for rounds 14–29.

The quartile range Q1–Q3 represents half the participating laboratories and when compared to the acceptable limits for difference and imprecision indicates how the majority of laboratories are performing (Table 3). Overall, ≥50% of the laboratories achieved acceptable difference and imprecision for VIA (<±12.1% and <7.1%), B12 (<±16.4% and <10.1%), FER (<±38.2% and <11.2%), and CRP (<±34.6% and <36.9%). Furthermore, ≥50% of the laboratories achieved acceptable imprecision for VID (<8.5%) and FOL (<17.0%), whereas <50% achieved acceptable difference for VID (<±14.8%) and FOL (<±25.6%).

Round-by-round performance

Plotting the round-by-round acceptable performance rates for difference and imprecision provides a visual impression of the overall laboratory performance over time (Figure 1). The proportion of laboratories having acceptable difference showed considerable round-by-round variation: VIA from 48% to 79%, VID from 19% to 63%, FOL from 33% to 89%, B12 from 0% to 92%, FER from 69% to 100%, and CRP from 56% to 90% for all pools and from 57% to 92% for pools ≥0.9 mg/L. The proportion of laboratories having acceptable imprecision showed generally less round-by-round variation: VIA from 65% to 93%, VID from 33% to 100%, FOL from 78% to 100%, B12 from 73% to 100%, FER from 73% to 100%, and CRP from 86% to 100% for all pools and from 87% to 92% for pools ≥0.9 mg/L.

We also noticed stark differences across the analytes when we plotted the round-by-round performance rates for difference and imprecision by the 4 categories, optimum, desirable, minimum, and unacceptable. The range of optimum performance rate for difference across the rounds was highest for FER (25%–75%) and lowest for VID (4%–26%) (Figure 4). The range of optimum performance rate for imprecision across the rounds was highest for CRP (72%–100%) and lowest for VID (0%–61%) (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

VITAL-EQA round-by-round performance rate for difference by performance category for vitamin A (VIA, A), vitamin D (VID, B), folate (FOL, C), vitamin B12 (B12, D), ferritin (FER, E), and C-reactive protein (CRP, F) for R10 (2008) to R29 (2017). For VID, no performance is shown for rounds 10–11 due to lack of available standard reference materials. For CRP, data are only shown for pools with target values ≥0.9 mg/L. VITAL-EQA, Vitamin A Laboratory-External Quality Assessment.

Figure 5.

VITAL-EQA round-by-round performance rate for imprecision by performance category for vitamin A (VIA, A), vitamin D (VID, B), folate (FOL, C), vitamin B12 (B12, D), ferritin (FER, E), and C-reactive protein (CRP, F) for R10 (2008) to R29 (2017). For CRP, data are only shown for pools with target values ≥0.9 mg/L. VITAL-EQA, Vitamin A Laboratory-External Quality Assessment.

Box-and-whisker plots (far outliers removed) for round-by-round performance of difference to the CDC target provide information on the distribution of the differences. We noted a similar picture as observed with the aggregate data: VIA, B12, FER, and CRP had quartile 1 to quartile 3 ranges (box) within the acceptable limits, whereas VID and FOL performed slightly worse (Supplementary Figure 7). The box-and-whisker plots for imprecision showed mostly acceptable performance across rounds, but we also noted for all analytes except VID an increase of the quartile 1 to quartile 3 range in more recent rounds when participation increased (Supplementary Figure 8).

Performance by pool concentration

Native serum pools purchased from US blood banks had limited concentration ranges (Supplementary Table 1), so individual rounds had relatively few low and/or high concentration pools. Thus, the concentration-related performance evaluation was only conducted for rounds that contained the lowest and highest pool concentrations, which was typically 5 rounds or less, with the exception of CRP where >10 rounds of data were available (Supplementary Table 3). For VIA, FER, and CRP, we observed similar performance for acceptable difference at low and high concentrations. For VID and B12, the performance appeared to be better at high concentrations, whereas for FOL, the performance appeared to be worse at high concentrations.

Performance by assay type

There were only 1 (VIA, B12, FER, CRP) or 2 (VID, FOL) predominant assay types for each analyte, making up close to 90% of data points generated by the participating laboratories (Supplementary Table 2). For VID, the rate of acceptable difference and imprecision was better for IA/PB assays (most used) compared with HPLC (second most used). In contrast, for FOL, the rate of acceptable difference and imprecision was better for MBA (second most used) compared with IA/PB assays (most used).

Performance of continuously participating laboratories

The ratio of continuously compared with sporadically participating laboratories in rounds 26–29 was different for each analyte and round but was approximately 3:1 for VIA; 2:1 for VID, FOL, FER, and CRP; and 1:1 for B12. The laboratories participating continuously in 4 rounds from 2016 to 2017 showed generally similar performance compared to laboratories participating occasionally (Table 4). For a detailed description of results by analyte, see Supplementary Results.

Table 4.

Comparison of method performance for laboratories with continuous participation vs. laboratories with occasional participation in 4 consecutive VITAL-EQA rounds (rounds 26–29)1

| Continuous vs. occasional participation | Round | Analyte | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VIA | VID | FOL | B12 | FER | CRP2 | ||

| Acceptable performance for difference (%) | 26 | 63 vs. 0 | 32 vs. 27 | 67 vs. 61 | 87 vs. 80 | 96 vs. 100 | 71 vs. 100 |

| 27 | 63 vs. 17 | 42 vs. 53 | 50 vs. 44 | 80 vs. 100 | 89 vs. 83 | 63 vs. 90 | |

| 28 | 56 vs. 48 | 38 vs. 55 | 46 vs. 13 | 73 vs. 53 | 100 vs. 100 | 54 vs. 63 | |

| 29 | 50 vs. 67 | 38 vs. 67 | 50 vs. 27 | 53 vs. 67 | 93 vs. 72 | 65 vs. 53 | |

| Acceptable performance for imprecision (%) | 26 | 72 vs. 17 | 82 vs. 100 | 79 vs. 100 | 60 vs. 87 | 81 vs. 100 | 100 vs. 100 |

| 27 | 69 vs. 50 | 79 vs. 53 | 96 vs. 94 | 80 vs. 87 | 81 vs. 67 | 100 vs. 100 | |

| 28 | 81 vs. 85 | 71 vs. 58 | 88 vs. 67 | 80 vs. 69 | 89 vs. 73 | 100 vs. 100 | |

| 29 | 69 vs. 67 | 71 vs. 90 | 88 vs. 73 | 67 vs. 79 | 81 vs. 72 | 100 vs. 100 | |

| Laboratories (n) | 26 | 16 vs. 2 | 8 vs. 5 | 8 vs. 6 | 5 vs. 5 | 9 vs. 4 | 9 vs. 3 |

| 27 | 16 vs. 4 | 8 vs. 5 | 8 vs. 7 | 5 vs. 5 | 9 vs. 6 | 9 vs. 5 | |

| 28 | 16 vs. 9 | 8 vs. 11 | 8 vs. 5 | 5 vs. 12 | 9 vs. 11 | 9 vs. 9 | |

| 29 | 16 vs. 6 | 8 vs. 7 | 8 vs. 5 | 5 vs. 8 | 9 vs. 6 | 9 vs. 5 | |

| Methods (n) | |||||||

| HPLC | 26 | 15 vs. 2 | 3 vs. 0 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 27 | 15 vs. 3 | 3 vs. 0 | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| 28 | 15 vs. 7 | 3 vs. 0 | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| 29 | 15 vs. 5 | 3 vs. 0 | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| IA/PB | 26 | 1 vs. 0 | 4 vs. 5 | 5 vs. 3 | 5 vs. 4 | 9 vs. 4 | 9 vs. 3 |

| 27 | 1 vs. 0 | 4 vs. 4 | 5 vs. 4 | 5 vs. 4 | 9 vs. 6 | 9 vs. 5 | |

| 28 | 1 vs. 0 | 4 vs. 5 | 5 vs. 4 | 5 vs. 9 | 9 vs. 10 | 9 vs. 9 | |

| 29 | 1 vs. 0 | 4 vs. 5 | 5 vs. 4 | 5 vs. 7 | 9 vs. 5 | 9 vs. 5 | |

| HPLC-MS/MS | 26 | NA | 1 vs. 0 | 1 vs. 0 | NA | NA | NA |

| 27 | 0 vs. 1 | 1 vs. 1 | 1 vs. 0 | NA | NA | NA | |

| 28 | 0 vs. 2 | 1 vs. 6 | 1 vs. 0 | NA | NA | NA | |

| 29 | 0 vs. 1 | 1 vs. 2 | 1 vs. 0 | NA | NA | NA | |

| MBA | 26 | NA | NA | 2 vs. 3 | 0 vs. 1 | NA | NA |

| 27 | NA | NA | 2 vs. 3 | 0 vs. 1 | NA | NA | |

| 28 | NA | NA | 2 vs. 1 | 0 vs. 2 | NA | NA | |

| 29 | NA | NA | 2 vs. 1 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Unknown (not reported) | 26 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 27 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| 28 | NA | NA | NA | 0 vs. 1 | 0 vs. 1 | NA | |

| 29 | NA | NA | NA | 0 vs. 1 | vs. 1 | NA | |

B12, serum vitamin B12; CRP, serum C-reactive protein; FER, serum ferritin; FOL, serum folate; IA/PB, immunoassay/protein binding assay; MBA, microbiologic assay; VIA, serum vitamin A; VID, serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D; VITAL-EQA, Vitamin A Laboratory-External Quality Assessment.

CRP pools featured are those with concentrations ≥0.9 mg/L, the CDC assay limit of quantitation for these rounds.

Discussion

This report describes the performance of VITAL-EQA participating laboratories over a 10-year period from 2008 to 2017 for selected water-soluble vitamins (FOL and B12), fat-soluble vitamins (VIA and VID), and iron status (FER and TFR) and inflammation (CRP) markers. Although acceptable imprecision was achieved by more laboratories than acceptable difference to the CDC target, the rate of acceptable performance for imprecision and difference ranged widely across rounds and laboratories, and we observed little change in overall performance over time. On aggregate, ≥60% of laboratories achieved acceptable difference for VIA, B12, FOL, FER, and CRP (only 44% for VID); and over 75% of laboratories achieved acceptable imprecision for all 6 analytes.

The long-term continuity of the program has proven valuable in highlighting the overall state of laboratory performance in low-resource countries. The 10-year aggregate data showed reasonably low mean CVs ranging from 5.6% (VIA) to 8.9% (FOL), as well as no (VIA, FOL, B12) or reasonably low (VID: 10.2%, FER: −10.5%) significant mean differences from CDC target values. Although the mean difference was fairly high for CRP (38.1%), it was considerably reduced to 11.5% after we removed far outliers. Not surprisingly, we found a wide range of round-by-round and individual laboratory performances, with some extreme CVs and differences reaching as high as 245% and 1712%, respectively. We were surprised, though, that the performance of continuously participating laboratories in rounds 26–29 (50%–75% of all participants in those rounds), did not appear to be better than the performance of laboratories participating occasionally. One reason for this could be that most participants use commercial kit assays that cannot be optimized by the user, and thus, the performance is not expected to change over time unless the manufacturer reformulates the assay. Based on the limited information available for TFR, we observed ~70% lower results for the Siemens platform compared with CDC target values (Roche platform). This difference was consistent over time and across laboratories, bringing a future standardization closer into reach, assuming that commutability can be demonstrated for the WHO reference material with various assays.

To ensure that the VITAL-EQA program continued to provide valuable and actionable information to individual participants, we started featuring in 2015 analyte-specific trend plots in the reports. These plots show the participants’ history on difference to the target by pool level for the last 3 y or longer to help visualize long-term performance and observe method shifts. In 2017, the program initiated the reuse of pools used in previous rounds, which provided information on measurement consistency over time.

The VITAL-EQA program was designed to be a free-of-charge laboratory assessment program to help participants monitor and potentially improve their assays by assessing measurement imprecision and comparing their results to CDC assigned target values. However, due to the lack of data on laboratory performance in low-resource countries, the program was often (mis) used to assess laboratory preparedness for upcoming national health and nutrition surveys. This proved to be an almost impossible task due to the low number of samples analyzed in each round. The latter is coincidentally also the reason why the VITAL-EQA program does not offer a performance certificate. To address this need, the CDC began in 2019 to provide additional, more comprehensive, fee-based method performance verification (MPV) program for the nutritional biomarkers covered in this report, as well as α-1-acid glycoprotein, an inflammation marker that remains elevated longer than CRP. The MPV program uses 40 instead of 6 specimens annually, spans a wide concentration range with unaltered native serum materials, and provides a performance certificate. It also allows for the generation of a prediction equation assuming the method has a correctable, systematic bias. This enables the laboratory to adjust their data to CDC methods that are often used for large-scale national surveys, such as the NHANES.

The VITAL-EQA and MPV programs are performance assessment and not standardization programs. They make it possible to identify performance issues, but they do not provide the tools for a root cause analysis or for fixing the problems. Standardization programs go beyond assessing method performance and often work directly with the assay manufacturer; they engage the participant to improve method accuracy and precision by utilizing commutable single-donor biological materials that have been characterized with reference measurement procedures compliant with international standards and by occasionally providing calibration materials. The biological materials used in the VITAL-EQA and MPV programs are mostly pooled materials to achieve sufficient specimen volumes. They have been characterized with routine measurement procedures that are of lower order in the traceability hierarchy and have wider uncertainty limits. Nonetheless, over the featured 10-y period, the accuracy of the CDC methods relative to international reference material target values was within the optimum acceptable criteria for VIA, FOL, and FER, and within the optimum and/or desirable criteria for VID, B12, and CRP.

The VITAL-EQA program uses CDC target values with acceptability limits based on biologic variation. The use of biologic variation accounts for multiple factors, such as age, disease state, cohort size, and sampling location, allows the scoring criteria to be used ubiquitously, and is suggested by European professional consensus [16]. It is preferable to using a fixed criterion, such as consensus mean ± 2SD, which can be largely influenced by changes in methods used by the participating laboratory community. Furthermore, EQA programs that use method-specific or instrument platform-specific target values do not contribute to the harmonization of results across methods; when each platform is scored against itself, it is bound to perform well. The minimal acceptable imprecision (<0.75 × CVi) and minimal acceptable difference [0.375 × ] criteria used by the VITAL-EQA program are the lowest acceptable standard. Our goal is to move the bar over time from minimal to desirable performance. However, that means 67% tighter imprecision and difference criteria, which would result in higher rates of unacceptable performance. Using biologic variation-based acceptability criteria also has a disadvantage in that some analytes have wide acceptable limits (difference: CRP <±34.6%, FER <±38.2%; imprecision: CRP <36.9%). Hence, participants obtaining an acceptable performance score for such analytes may not achieve performance levels required to identify small changes in population concentrations over time.

The VITAL-EQA program has limitations. Using native serum helps to reduce the potential for commutability problems and provides readily interpretable information on how well assays perform with unmodified specimens. However, it also limits the available analyte concentration range. We obtained serum from US blood banks where samples suggesting nutritional deficiencies and inflammation are less prevalent compared to what is encountered in low-resource countries. For example, an accuracy assessment of VIA measurements at the WHO subclinical (20 μg/dL) and severe (10 μg/dL) deficiency levels was not possible, and <20% of the blood bank serum had CRP concentrations ≥5 mg/L [17]. Shipping issues also presented major challenges for the VITAL-EQA program because serum specimens require frozen shipments, and customs regulations in many countries prevent shipping on dry ice. Due to long transit times and customs clearance delays, some packages were reported being received at room temperature. In those cases, it was difficult to assess the impact of shipping conditions on the resulting data. Using shipper feedback information and package temperature tracking data from rounds 26–29, we observed the most problematic regions for shipments being delivered warm or failing to reach the laboratory were in Asia (India, Indonesia, Philippines, Oman, Thailand, and Vietnam) and Africa (South Africa and Zambia). During the 2016 rounds, of 39 shippers, 23% were reported arriving cold, 21% arriving warm or not arriving at all, and no temperature information was reported for 56% of shippers. This greatly improved during the 2017 rounds, where of 43 shippers, 81% were reported arriving cold, 12% arriving warm, and no data were reported for only 7% of shippers. Based on temperature stability studies conducted by our group, the analytes featured in the VITAL-EQA program should not be negatively affected after being exposed to refrigerated temperature (~10°C) for <1 wk [18,19].

In conclusion, the VITAL-EQA program is accessible to low-resource public health laboratories at virtually no cost, laboratories can track their performance over time and see how their method fares compared to other methods, and they can test multiple methods per analyte. By obtaining external feedback on method performance, the laboratory can gauge whether any improvement, troubleshooting, analyst training or further validation of laboratory-developed assays needs to be performed. The major advantage of the program is that it provides unique information on the overall state of method performance for nutritional biomarkers in low-resource laboratories which otherwise is not available. The major limitation of the program continues to be the small number of samples per challenge, which provides insufficient information to make definitive conclusions regarding laboratory performance and readiness for public health investigations. The more recently developed MPV program can better serve those needs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows – CMP: designed the research; MC-W coordinated the VITAL-EQA program; MZ and MC-W: analyzed the data; MC-W: wrote the paper; CMP: had primary responsibility for content; and all authors: read and approved the final manuscript. We acknowledge financial support for the VITAL-EQA program from the International Micronutrient Malnutrition Prevention and Control Program at the National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC. We would also like to thank Dr. Rosemary Schleicher, CDC, for her leadership and direction of the VITAL-EQA program during its first decade.

Funding

This work was performed under employment of the US Federal government and the authors did not receive any outside funding.

Abbreviations used:

- B12

serum vitamin B-12

- ERM

European Reference Materials

- FER

serum ferritin

- FOL

serum folate

- IA/PB

immunoassay/protein binding

- LMIC

low- and middle-income country

- MBA

microbiologic assays

- MPV

method performance verification

- VIA

serum vitamin A

- VITAL-EQA

Vitamin A Laboratory-External Quality Assessment

- VID

serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tjnut.2022.11.001.

Disclosure

All other authors report no conflicts of interest. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Use of trade names and commercial sources is for identification only and does not constitute endorsement by the US Department of Health and Human Services or the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Data availability

The data underlying this article can be made available upon request.

References

- [1].World Health Organization, in: Allen L, de Benoist B, Dary O, Hurrell R (Eds.), Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Guidelines on food fortification with micronutrients, WHO Press, Geneva, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Haynes BMH, Schleicher RL, Jain RB, Pfeiffer CM, The CDC VITAL-EQA program, external quality assurance for serum retinol, 2003–2006, Clin Chim Acta 390 (1–2) (2008) 90–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Thorpe SJ, Heath A, Sharp G, Cook J, Ellis R, Worwood M, A WHO reference reagent for the serum transferrin receptor (sTfR): international collaborative study to evaluate a recombinant soluble transferrin receptor preparation, Clin Chem Lab Med 48 (6) (2010) 815–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Fraser CG, Hyltoft Petersen PP, Libeer JC, Ricos C, Proposals for setting generally applicable quality goals solely based on biology, Ann Clin Biochem 34 (1) (1997) 8–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Lacher DA, Hughes JP, Carroll MD, Biological variation of laboratory analytes based on the 1999–2002 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. National health statistics reports, no 21, National Center for Health Statistics, Hyattsville, MD, 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Ricos C, Alvarez V, Cava F, Garcia-Lario JV, Hernandez A, Jimenez CV, et al. , Desirable specifications for total error, imprecision, and bias, derived from intra- and inter-individual biologic variation [Internet], 2014. Available from: www.westgard.com/guest17.htm. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Cooper MJ, Zlotkin SH, Day-to-day variation of transferrin receptor and ferritin in healthy men and women, Am J Clin Nutr 64 (5) (1996) 738–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Raya G, Henny J, Steinmetz J, Herbeth B, Siest G, Soluble transferrin receptor (sTfR): biological variations and reference limits, Clin Chem Lab Med 39 (11) (2001) 1162–1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Chaudhary-Webb M, Schleicher RL, Erhardt JG, Pendergrast EC, Pfeiffer CM, An HPLC ultraviolet method using low sample volume and protein precipitation for the measurement of retinol in human serum suitable for laboratories in low- and middle-income countries, J Appl Lab Med 4 (1) (2019) 101–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Schleicher RL, Encisco SE, Chaudhary-Webb M, Paliakov E, McCoy LF, Pfeiffer CM, Isotope dilution ultra performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry method for simultaneous measurement of 25-hydroxyvitamin D2, 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 and 3-epi-25-hydroxyvitamin D3 in human serum, Clin Chim Acta 412 (17–18) (2011) 1594–1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Pfeiffer CM, Zhang M, Lacher DA, Molloy AM, Tamura T, Yetley EA, et al. , Comparison of serum and red blood cell folate microbiologic assays for national population surveys, J Nutr 141 (7) (2011) 1402–1409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Cobas® Vitamin B12 [package insert], Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, 2012-January. V2. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Cobas® Ferritin [package insert], Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, 2009-January. V8. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Cobas® Tina-quant Soluble transferrin receptor (TfR) [package insert], Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, 2010-June. V8. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Cobas® Tina-quant C-reactive protein Gen.3 [package insert], Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, 2009-May. V2. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Fraser CG, General strategies to set quality specifications for reliability performance characteristics, Scand J Clin Lab Investig 59 (7) (1999) 487–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].WHO, Serum retinol concentrations for determining the prevalence of vitamin A deficiency in populations [Internet], 2011. [cited March 18, 2022]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-NMH-NHD-MNM-11.3. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Drammeh BS, Schleicher RL, Pfeiffer CM, Jain RB, Zhang M, Nguyen PH, Effects of delayed sample processing and freezing on serum concentrations of selected nutritional indicators, Clin Chem. 54 (11) (2008) 1883–1891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Chen H, Sternberg MR, Schleicher RL, Pfeiffer CM, Long-term stability of 18 nutritional biomarkers stored at −20°C and 5°C for up to 12 months, J Appl Lab Med 3 (1) (2018) 100–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article can be made available upon request.