Abstract

Nucleic acid-based therapies have become the third major drug class after small molecules and antibodies. The role of nucleic acid-based therapies has been strengthened by recent regulatory approvals and tremendous clinical success. In this review, we look at the major obstacles that have hindered the field, the historical milestones that have been achieved, and what is yet to be resolved and anticipated soon. This review provides a view of the key innovations that are expanding nucleic acid capabilities, setting the stage for the future of nucleic acid therapeutics.

Keywords: clinical trials, delivery, therapeutics

Introduction

It has been almost 25 years since the first nucleic acid-based therapeutic—fomivirsen—was approved in 1998 [1]. Nucleic acid therapeutics (NATs) are drugs with nucleic acids as their therapeutically active component, such as DNA or RNA of all forms [2]. Since 1998, this new ground-breaking class of drugs has expanded to more than 20 approved products, with hundreds of ongoing clinical trials worldwide [3–6]. The NAT modalities approved and under investigation harness different mechanisms of action with an ever-expanding chemistry, conjugation, and delivery platforms. In this perspective, we provide a short overview of (a) the challenges NATs must overcome, (b) the progress of NATs to date, and (c) highlight new therapeutics that may enter the clinic, hit clinical milestones, or achieve regulatory approval in 2024 and beyond. Thanks to the significant innovation opening new organs and diseases for NAT applications, we discuss the potential of NATs as a new drug class, offering a future for patients with uncurable diseases.

NAT Challenges, Chemical Modifications, and Delivery

NATs, including antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs), aptamers, small interfering RNA (siRNA), and Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR)-Cas entities have become a powerful class of medicines for a wide range of diseases (Fig. 1). With the proven clinical productivity and strong development pipeline, it is worth reevaluating the past failures, lessons learned, and successes that led to the rapid expansion of these therapies. Through this, we hope to understand what innovations are needed to reshape the future landscape of nucleic acid-based therapeutics.

FIG. 1.

Mechanisms of currently approved nucleic acid therapeutic modalities. Color images are available online.

First, NATs must be delivered into biological systems (administration and absorption) without being degraded by nucleases (stability). Second, they have to avoid off-target organ clearance and kidney excretion (elimination), distribute to the organs of interest (biodistribution), followed by being internalized into proper cellular compartments and released into the cytoplasm (uptake and endosomal escape). More importantly, they must maintain the ability to interact with relevant intracellular machinery [eg, RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) and RNase-H] to perform the intended functions [4,7].

These challenges require substantial scientific innovations to achieve final clinical success.

Due to their natural RNA and DNA components, oligonucleotides are susceptible to nucleases for biodegradation when introduced to a biological system [8]. Advances in nucleotide chemistry have largely addressed this issue, mainly through chemical modifications to the oligonucleotides, which support prolonged stability and enhanced activity. The most used chemical modifications found in approved and under-investigation NATs are summarized in Fig. 2. In short, these include backbone modifications, primarily phosphorothioate (PS), and sugar modifications at the 2′ position most commonly, -O-methyl, -O-methoxyethyl, and -fluoro (2′OMe, 2′MOE, and 2′F, respectively) [9]. Beyond the common modifications, there are hundreds of backbone, sugar, and nucleotide variants, each providing unique biochemical properties [4]. The detailed structure and biological functionality have been reviewed previously [4].

FIG. 2.

Common and clinically approved backbone, sugar, and base modifications found in nucleic acid therapeutics. Color images are available online.

For productive biodistribution, oligonucleotides must circulate efficiently to distribute to the organ of interest while avoiding excretion by clearance organs. There are various delivery strategies to manipulate the biodistribution of NATs to the liver, such as using lipid nanoparticle (LNP) formulations and targeting ligand conjugation [10–12].

The most impactful ligand conjugate to date is N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc), a ligand for the asialoglycoprotein receptor (ASGPR) [13]. ASGPR is exclusively and highly expressed on hepatocytes, allowing for liver-specific delivery of NATs [13,14]. The field is interested in expanding the utility of NATs to extrahepatic organs due to unmet clinical needs [15–18]. To address extrahepatic delivery and distribution, many other strategies are currently under exploration [19]. Additional strategies under investigation but not yet approved include oligonucleotides conjugated to antibodies (eg, transferrin receptor antibody conjugation for enhanced muscle delivery [16]) and lipids (eg, C16 conjugation for enhanced central nervous system [CNS] distribution [15]). The conjugates and delivery approaches used to manipulate biodistribution are summarized and visualized in Fig. 3.

FIG. 3.

Lipid- antibody-, sugar-based delivery approaches for nucleic acid therapeutics that are either approved or under clinical investigation. Color images are available online.

While many barriers exist before the full potential of NATs is reached, there are over 20 approved NATs. The clinically available NATs feature varying degrees of nucleic acid modifications (including RNA, DNA, PS, -OMe, -O-MOE, and -F) with or without lipid formulation or GalNAc-conjugation and have brought cures or treatments to dozens of diseases. Although imperfect, the NATs approved by regulatory bodies [Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and/or European Medicines Agency (EMA)] have been foundational for the field and laid the groundwork for future advances.

Progress to Date: Approved NATs 1998–2023

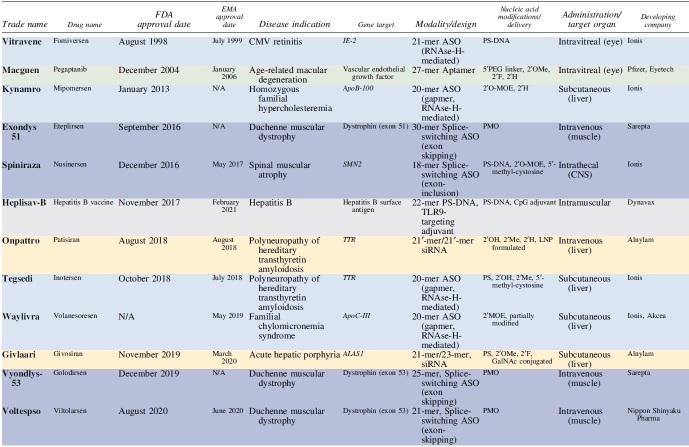

Since 1998, there have been 22 FDA- and/or EMA-approved NATs, including 6 RNAse-H-activating ASOs, 5 splice-switching ASOs (SSOs), 1 LNP-formulated siRNA, 5 GalNAc-conjugated fully modified siRNA, 2 aptamers, and 1 CRISPR-based therapeutic (Table 1). While the first generation of therapeutics approved showed some efficacy, their low durability and potency resulted in limited clinical impact and usage. With years advancing, the field enjoyed a profound acceleration in the number of drugs approved and improved efficacy, potency, and durability.

Table 1.

Approved Nucleic Acid-Based Therapeutics as of Late 2023

|

Antisense Oligonucleotides

ASOs are one of the earliest-studied classes of NAT and the first to gain approval. They are 18–30mer single-stranded oligonucleotides capable of exhibiting effects in two different mechanisms: lower protein production through RNase-H-mediated degradation of complementary mRNA or modulate mRNA splicing to produce differently spliced mRNA isoform variants [20].

RNase-H-mediated ASO activity

When ASOs bind to their complementary sequence on the target mRNA, it forms a DNA-RNA hybrid that is a substrate of the nuclease RNase-H, which degrades the RNA pair [2,4]. RNase-H-activating ASOs can be made in full from DNA nucleotides (eg, Vitravene, 1998 [21]) or have the improved “GapmeR” design (eg, Kynamro [22], 2013; Tegsedi [23,24], 2018; Tofersen, 2023). GapmeRs are primarily made in a 5-10-5 nucleotide fashion, where the flanking 5′ and 3′ regions are RNA-like nucleotides for improved target binding, and the middle 10 nucleotides “gap” is DNA-like that is optimal for RNase-H activity [2,4]. The size of the DNA-like gap can be reduced to increase specificity, and the flanks can be shorter when higher affinity modifications are used. GapmeRs have held their durability and popularity in the field, with the most recently approved NAT drug being a 20-mer GapmeR ASO for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) (Tofersen) in 2023 [25–27]. In addition to approved drugs, many failed to demonstrate robust clinical efficacy or induce drug-specific toxicity [28,29].

Currently, approved ASOs are pan-silencing, meaning they lack allele specificity. Ongoing research develops ASOs to be selective to the disease allele based on single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) while preserving the essential wild-type allele function [30].

SSOs are single-stranded ASOs that bind to pre-mRNA at specific sites to physically modulate interactions with spliceosome machinery [20]. As a result, exons can be selectively included or excluded from the final mature mRNA transcript to restore functional target protein expression. As the most common FDA-approved drug class to date, SSOs have shown robust therapeutic benefits in the clinic for spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) [10,11]. Nusinersen, the SSO for SMA, has dramatically impacted SMA disease progression, leading to increased event-free survival and improved patient motor outcomes [31]. Nusinersen uses intrathecal delivery and promotes exon-inclusion [31]. Beyond nusinersen, the approved SSOs each feature a modified backbone chemistry to improve exon-skipping capabilities [2,4]. This class of ASOs appears to have a broader therapeutic index, at least in the cerebrospinalfluid (CSF), but individual compound toxicity has been reported [32,33]. A feature of nusinersen is that it is approved for three types of SMA.

This broad application, unfortunately, does not apply to Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), where SSO therapies are mutation-specific. For example, Exondys 51, Vyondys-53, Viltepso, and Amondys 45 are each SSOs targeting dystrophin mRNA to skip exon 51, 53, 53, or 45, respectively [34–42]. Each of these SSOs has an identical chemical modification pattern [phosphorodiamidate morpholino (PMO)] and design but targets a different exon to be skipped depending on the patient's disease-causing mutations. It is important to note that while PMOs are commonly grouped with NATs, PMO modifications are not nucleic acid-like in their chemical structure, instead they more appropriately fall under oligomers rather than oligonucleotides due to having a different sugar and phosphorus backbone compared with nucleotides. Unlike the robust therapeutic benefits seen with nusinersen in SMA, the currently available SSOs for DMD clinically appear to slow the progression of the disease at best [43].

One key SSO of note is Milasen, the first n-of-1 SSO designed for Mila, a patient with a specific mutation causing her Batten disease (more about NATs for rare diseases later) [44]. Milasen highlights the near-endless potential of SSOs to manipulate pathologic variants from common to ultrarare. Genetic testing is required to determine if a patient is amendable to one of the currently available SSOs.

CpG Oligodeoxynucleotides

Short single-stranded oligonucleotides can also infer a therapeutic effect in an immunostimulatory mechanism using cytosine–phosphodiester–guanine-rich sequences [45]. These are known to stimulate dendritic cells and B cells through interaction with Toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9), leading to a proinflammatory cascade [46]; thus, CpG oligodeoxynucleotides (ODNs) can be used for treating diseases that require amplification of these immune responses. In 2017, the FDA approved the first single-stranded nucleic acid-based vaccine for hepatitis B (HEPLISAV-B) [47]. Heplisav-B contains the hepatitis B surface antigen that is adjuvanted with a PS-DNA 22-mer CpG ODN that amplifies the immune reaction and thus offers the intended immunization [47]. In 2023, the FDA approved another CpG-adjuvanted vaccine, CYFENDUS, as a postexposure prophylaxis following Bacillus anthracis (anthrax) exposure. The recent 2023 approval demonstrates the utility of CpG-adjuvants in the field and their continued success [48].

Aptamers

The primary mechanism of action for most NATs is through a sequence complementary to their target. In addition, single-stranded nucleic acids, such as aptamers, can structurally act as drugs themselves. Aptamers are structured single-stranded DNA or RNA selected from a large pool to bind, sequester, or inactivate their specific target (small molecules or proteins) [49]. Aptamers are similar to antibodies in that they bind to their target with high affinity; however, they offer a handful of advantages compared with their protein counterpart. This includes ease of manufacturing through chemical synthesis, binding a wide range of targets (proteins, small molecules, bacteria, viruses, cells), smaller size and increased permeability, and high stability [4,49–51]. Aptamers also carry a unique biodistribution and pharmacokinetic profile compared with small molecules [49,50]. An example of aptamers as therapeutics is pegaptanib (approved in 2004)—designed to bind and inhibit vascular endothelial growth factor for treating age-related macular degeneration (AMD) [52,53].

Early-designed aptamers were not fully modified, resulting in low stability and limiting clinical utility; pegaptanib was discontinued in 2011. The second aptamer, IZERVAY, just received FDA's approval in 2023, almost two decades after this modality's first approval [54,55]. IZERVAY is a complement C5 inhibitor for geographic atrophy of AMD [54,55]. The promise of aptamers persists, with active aptamer research expanding to applications in infection, hematology, oncology, and more [50].

Recent advances in chemistry, including the inclusion of hydrophobically modified base analogs, have significantly enhanced the diversity of the structural chemical space. This innovation has generated high-affinity aptamer compounds from much shorter randomized pools [51,56]. This type of aptamers, called somamers, are currently widely used in diagnostics, and their therapeutic potential remains high. Current technological advances allow for the selection of highly modified aptamers [51], representing a significant therapeutic potential of this class of modalities.

Small Interfering RNA

Another major class of NATs is the siRNAs. siRNAs are double-stranded oligonucleotides consisting of guide (antisense) and passenger (sense) strands. siRNAs recognize their complementary target mRNA transcripts and degrade them to halt subsequent protein production [57]. Their mechanism of action differs from that of ASOs, as they utilize RISC to trigger mRNA cleavage instead of relying on RNase-H-based mRNA degradation. Upon entering cells, siRNA is loaded into the argonaute 2 (Ago2), which recruits other proteins to form an active RISC [58]. The passenger strand is then released, and the guide strand-loaded Ago2 identifies and degrades the target mRNA in a catalytic manner [59]. siRNAs have revolutionized the therapeutic paradigm of treating several hepatic diseases, supporting multi-month (up to 6–9 months) durability upon a single administration in patients [60].

The first approved (in 2018) siRNA drug is ONPATTRO for the treatment of polyneuropathy of hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis that used an LNP formulation [61,62]. Since then, five additional siRNA drugs have been approved for liver targets (GIVLAARI, OXLUMO, LEQVIO, AMVUTTRA, RIVFLOZA) [63–74].

After ONPATTRO, the other liver-targeting siRNA featured the GalNAc conjugate for unprecedented and specific localization to the liver [14]. The chemical composition, sequence, and clinical indications of these siRNA drugs have recently been reviewed by Egli and Manoharan [4]. Liver targets silenced with GalNAc-conjugated siRNA have also been used for diseases outside the liver, including RIVFLOZA for primary hyperoxaluria (Dicerna/Novo Nordisk) [75]. With a GalNAc-siRNA against the liver enzyme lactate dehydrogenase in the liver, kidney stone formation can be reduced (Dicerna/Novo Nordisk) [76].

CRISPR-Cas-Based Therapies

Finally, one area using oligonucleotide–protein hybrids is the CRISPR-Cas-based gene-editing system [77]. The 2020 Nobel Prize in chemistry was awarded to Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier for their contributions to discovering the mechanism of the CRISPR-Cas system. This technology has enormous potential in various therapeutic applications for treating genetic diseases by correcting the root causes. In general, CRISPR-Cas systems can delete, insert, or modify DNA (eg, with Cas9) or RNA (eg, with Cas13) sequences with single nucleotide precision using a short guiding oligonucleotide (sgRNA). This genetic manipulation alters protein expression at the genetic level [78–83], enabling the prevention of specific protein production and restoring the function of terminated miscoded proteins or even inserting whole genes to be expressed [84]. From a therapeutics delivery standpoint, the protein component of Cas is typically delivered as an mRNA for endogenous translation [85].

Most recently, Vertex Pharmaceuticals and CRISPR Therapeutics have received the approval of the first CRISPR-Cas therapy, exagamglogene autotemcel, in the United Kingdom and United States in November and December, respectively, of 2023 for the treatment of sickle cell disease [86,87]. CRISPR-Cas-based therapeutics are currently being evaluated in clinics in the United States/European Union (US/EU) but have not yet received approval from the FDA/EMA. Furthermore, companies such as Prime Medicine and Intellia Therapeutics are working on developing new generations of Cas proteins that can induce edits in DNA or RNA with single nucleotide precision in vivo [78–80,83]. There are multiple and evergrowing ways to use CRISPR-Cas-based technologies, which have been extensively reviewed elsewhere, and there is no doubt this technology is set to have more breakthroughs soon [88].

Transfer RNAs

One last class of NATs to highlight is transfer RNA (tRNA)-based therapeutics. The tRNAs are the most abundant cytoplasmic RNA in the eukaryotic cell and play a crucial role in transferring the mRNA code into a functional protein that then carries function in the cell [89]. Many genetic diseases are based on premature termination of protein synthesis due to a nonsense mutation in the mRNA. The tRNA-based therapies aim to engineer tRNAs that can read through these mutations and carry on protein synthesis to completion [89]. While this technology is still in its early stages, interest in tRNA-based therapeutics is increasing, and biotechnology companies such as Alltrna are paving the way [89,90]. The tRNA therapies have been reviewed elsewhere [89,90].

Progress Summary

The past few decades have witnessed various NATs being conceptually conceived and successfully developed, advancing toward regulatory approvals. It took a long path of innovation for the first therapies to hit the market (eg, 20 years for ASOs, 20 years for siRNAs), followed by the rapid advancement of additional candidates in each class, with more than 13 therapies being approved in the past 5 years alone. We can expect more clinical milestones and approvals soon based on the exponential creation, validation, and approval of NATs in recent years. The NATs coming down the pipeline feature existing and new chemical approaches to overcome known barriers and unlock previously inaccessible targets and organs.

Looking Ahead: Innovation Coming Down the Pipeline in 2024 and Beyond

In the coming years and decades, we look forward to continued validation of new and existing technologies that may unlock organs previously inaccessible to NATs. Our goal in the following sections is to highlight the NATs and modalities that may be approved or advanced in clinical trials throughout 2024 and beyond. Overall, at least 80 clinical trials are currently investigating NATs broken down into at least 20 for liver targets, 10 for CNS targets, 10 for oncological targets, and dozens more for targets in the muscle, skin, lung, eye, or placenta. These numbers are ever-changing due to the dynamic nature of NATs in the clinical setting. A representative but nonexhaustive list of NATs in clinical trials as of late 2023 is summarized in Table 2. Below, we highlight some upcoming NATs grouped by the organs they target (Fig. 4).

Table 2.

Nucleic Acid-Based Therapeutics Under Clinical Investigation

| Target organ | Drug name | Disease indication | Gene target | Modality | Novel chemical features | Route of administration | Phase (as of late 2023) | Company |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liver | ||||||||

| NTLA-2002 | Hereditary angioedema | KLKB1 | CRISPR-Cas9, LNP | CRISPR-Cas9 (LNP packaged mRNA) | Intravenous | Phase 2 | Intellia Therapeutics | |

| NTLA-2001 | Hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis with polyneuropathy | TTR | CRISPR-Cas9, LNP | CRISPR-Cas9 (LNP packaged mRNA) | Intravenous | Phase 2 | Intellia Therapeutics | |

| Pelacarsen | Cardiovascular disease | Lipoprotein a | ASO | GalNAc-ASO (ligand-conjugated ASO, LICA) | Subcutaneous | Phase 3 | Ionis/Novartis | |

| Olezarsen | Familial chylomicronemia/severe hypertriglyceridemia | ApoC-III | ASO | GalNAc-ASO (ligand-conjugated ASO, LICA) | Subcutaneous | Phase 3 (familial chylomicronemia); Phase 2 (hypertriglyceridemia) | Ionis | |

| ALN-HSD | NASH | HSD17B13 | GalNAc-siRNA | Subcutaneous | Phase 1/2 | Alnylam/Regeneron | ||

| ALN-PNP | NASH | Patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing protein 3 | GalNAc-siRNA | Subcutaneous | Phase 1/2 | Alnylam | ||

| ALN-KNK | Type 2 diabetes | Ketohexakinase | GalNAc-siRNA | Subcutaneous | Phase 1/2 | Alnylam | ||

| Zilebesiran | Cardiovascular disease | Angiotensinogen | GalNAc-siRNA | Subcutaneous | Phase 2 | Alnylam | ||

| Fesomersen | Thrombosis | Factor XI | ASO | GalNAc-ASO (ligand-conjugated ASO, LICA) | Subcutaneous | Phase 2 | Ionis | |

| IONIS-AGT-LRx | Treatment-resistant hypertension, chronic heart failure with reduced ejection fraction | Angiotensinogen | ASO | GalNAc-ASO (ligand-conjugated ASO, LICA) | Subcutaneous | Phase 2 (hypertension) Phase 2 (HFrEF) |

Ionis | |

| ION904 | Treatment-resistant hypertension | Angiotensinogen | ASO | GalNAc-ASO (ligand-conjugated ASO, LICA) | Subcutaneous | Phase 2 | Ionis | |

| Donidalorsen | Hereditary angioedema | Prekallikrein | ASO | GalNAc-ASO (ligand-conjugated ASO, LICA) | Subcutaneous | Phase 3 | Ionis | |

| Sapablursen | Polycythemia vera | Transmembrane serine protease 6 | ASO | GalNAc-ASO (ligand-conjugated ASO, LICA) | Subcutaneous | Phase 2 | Ionis | |

| Fitusiran | Hemophilia A or B | Antithrombin | GalNAc-siRNA | Subcutaneous | Phase 3 | Alnylam | ||

| Belcesiran | Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency-associated liver disease | Alpha-1 antitrypsin | GalNAc-siRNA | Subcutaneous | Phase 2 | Dicerna | ||

| Zerlaziran | Cardiovascular disease | Lipoprotein a | siRNA | Subcutaneous | Phase 2 | Silence Therapeutics | ||

| DCR-AUD | Alcohol use disorder | ALDH2 | GalNAc-siRNA | Subcutaneous | Phase 1 | Dicerna | ||

| Cemdisiran (ALN-CC5) | Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria | Complement C5 | siRNA | GalNAc-siRNA | Subcutaneous | Phase 2 | Alnylam | |

| Cemdisiran (ALN-CC5) | IgA nephropathy | Complement C5 | siRNA | GalNAc-siRNA | Subcutaneous | Phase 1/2 | Alnylam | |

| Fazirsiran (ARO-AAT) | Alpha-1 antitrypsin decency-associated liver disease | Serpin 1 | siRNA | GalNAc-derivative | Subcutaneous | Phase 3 | Arrowhead/Takeda | |

| Plozasiran | Hypertriglyceridemia | ApoC-III | siRNA | GalNAc-derivative | Subcutaneous | Phase 2 | Arrowhead | |

| GSK4532990 | NASH | HSD17B13 | siRNA | GalNAc-derivative | Subcutaneous | Phase 2 | Arrowhead/GSK |

| CNS | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

Tominersen |

Huntington's disease |

Huntingtin |

Gapmer ASO (2′MOE) |

|

Intrathecal |

Phase 2 |

Ionis/Roche |

| |

Ulefnersen |

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis |

Fused-in sarcoma |

Gapmer ASO (2′MOE) |

|

Intrathecal |

Phase 3 |

Ionis |

| |

ALN-APP |

Early-onset Alzheimer's disease |

Amyloid beta precursor |

siRNA |

2-O-Hexadecyl (C16) conjugate |

Intrathecal |

Phase 1 |

Alnylam |

| |

Zilganersen |

Alexander disease |

Glial fibrillary acidic protein |

ASO |

|

Intrathecal bolus |

Phase 2/3 |

Ionis |

| |

Ionis-MAPT (BIIB080) |

Alzheimer's disease |

Microtubule-associated protein tau |

ASO |

|

Intrathecal |

Phase 1/2 |

Ionis/Biogen |

| |

ION859 |

Parkinson's disease |

Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 |

ASO |

|

Intrathecal |

Phase 2 |

Ionis/Biogen |

| |

ION464 |

Multiple system atrophy and Parkinson's disease |

SNCA

|

ASO |

|

Intrathecal |

Phase 2 |

Ionis/Biogen |

| |

ION582 |

Angelman syndrome |

UBE3A-AT2

|

ASO |

|

Intrathecal |

Phase 2 |

Ionis/Biogen |

| |

ION260 |

Spinocerebellar ataxia |

ATXN3

|

ASO |

|

Intrathecal |

Phase 1 |

Ionis/Biogen |

| ION306 | Spinal muscular atrophy | SMN2 | ASO | Intrathecal | Phase 1 | Ionis/Biogen |

| Heart | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AZD8601 | Myocardial ischemia | Vascular endothelial growth factor-A | mRNA | Intramyocardial injection | Phase 2 | Moderna/AstraZeneca |

| Placenta | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBP-4888 | Preeclampsia | Soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 | siRNA | Lipid-conjugation | Subcutaneous | Phase 1 | Comanche Biopharma |

| Eye | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

Lufepirsen |

Persistent corneal epithelial defect from chemical or thermal injury |

Connexin-43 |

30-mer ASO |

Unmodified |

Topical ophthalmic gel |

Phase 2 |

Ionis |

| Tivanisiran | Dry eye in setting of Sjogren's syndrome | Transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 | 19-mer siRNA | Blunt siRNA design | Ophthalmic solution | Phase 3 | Sylentis |

| Blood/lymph | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

CTX001 (Casgevy) |

Sickle cell anemia |

BCL11A

|

CRISPR-Cas9 |

|

Ex vivo electroporation |

Phase 2/3 |

CRISPR Therapeutics/Vertex |

| |

CTX001 (Casgevy) |

Beta-cell thalassemia |

BCL11A

|

CRISPR-Cas9 |

|

Ex vivo electroporation |

Phase 2/3 |

CRISPR Therapeutics/Vertex |

| |

CpG-STAT3 siRNA CAS3/SS3 |

Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma |

STAT3

|

siRNA |

CpG (TLR9 agonist)-conjugated siRNA |

Intratumorally |

Phase 1 |

City of Hope Medical Center |

| |

BNT116 |

Non-small cell lung cancer |

Immunogenic stimulator |

mRNA |

uRNA |

Intravenous |

Phase 1/2 |

BioNTech |

| |

BNT152 |

Solid tumors |

IL7 stimulator |

mRNA |

Liposomal RNA |

Intravenous+C64 |

Phase 1 |

BioNTech |

| |

BNT111 |

Melanoma |

Tumor associated antigens: NY-ESO-1, tyrosinase, melanoma-associated-antigen-3, transmembrane phosphatase with tensin homology |

mRNA |

uRNA |

Intravenous |

Phase 1 |

BioNTech |

| |

BNT112 |

Prostate cancer |

Prostate cancer-associated antigens |

mRNA |

uRNA |

Intravenous |

Phase 1 |

BioNTech |

| BNT113 | Metastatic HPV+ head and neck cancer | E6 and E7 HPV proteins | mRNA | uRNA | Intravenous | Phase 2 | BioNTech |

| Muscle | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

AOC 1001 |

Myotonic dystrophy type 1 |

DMPK

|

siRNA |

Conjugation of monoclonal antibody binding to transferrin-receptor |

Intravenous |

Phase 1/2 |

Avidity Biosciences |

| |

AOC 1044 |

Duchenne muscular dystrophy |

Dystrophin gene, exon 44 |

siRNA |

Conjugation of monoclonal antibody binding to transferrin-receptor |

Intravenous |

Phase 1/2 |

Avidity Biosciences |

| |

AOC 1020 |

Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy |

DUX4

|

siRNA |

Conjugation of monoclonal antibody binding to transferrin-receptor |

Intravenous |

Phase 1/2 |

Avidity Biosciences |

| |

ENTR-601-44 |

Duchenne muscular dystrophy |

Dystrophin gene, exon 44 |

PMO |

Endosomal escape vehicle-conjugated PMO |

Intravenous |

Phase 1 |

Entrada |

| |

DYNE-101 |

Myotonic dystrophy |

DMPK

|

ASO |

Fab targeting transferrin receptor |

Intravenous |

Phase 1/2 |

Dyne Therapeutics |

| |

DYNE-251 |

Duchenne muscular dystrophy |

Dystrophin gene, exon 51 |

ASO |

Fab targeting transferrin receptor |

Intravenous |

Phase 1/2 |

Dyne Therapeutics |

| |

Vesleteplirsen (SRP-5051) |

Duchenne muscular dystrophy |

Dystrophin gene, exon 51 |

PMO |

Next-gen peptide-conjugated PMO |

Intravenous |

Phase 2 |

Sarepta |

| |

PGN-EDODM1 |

Myotonic dystrophy |

DMPK

|

PMO |

Enhanced delivery oligonucleotide peptide-conjugated PMO |

Intravenous |

Phase 1 |

PepGen |

| PGN-EDO51 | Duchenne muscular dystrophy | Dystrophin gene, exon 51 | PMO | Enhanced delivery oligonucleotide peptide-conjugated PMO | Intravenous | Phase 2 | PepGen |

| Skin | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

OX101 |

Wound healing |

Connective tissue growth factor |

siRNA |

Polypeptide nanoparticle-mediated delivery |

Intradermal |

Phase 2 |

OliX Pharmaceuticals |

| |

STP707 |

Solid tumors |

TGF-beta/COX-2 |

siRNA |

Polypeptide nanoparticle-mediated delivery |

Intravenous |

Phase 1 |

Sirnaomics |

| |

STP705 |

Basal cell carcinoma |

TGF-beta/COX-2 |

siRNA |

Polypeptide nanoparticle-mediated delivery |

Intralesion |

Phase 2 |

Sirnaomics |

| |

STP705 |

In situ squamous cell carcinoma |

TGF-beta/COX-2 |

siRNA |

Polypeptide nanoparticle-mediated delivery |

Intralesion |

Phase 2 |

Sirnaomics |

| STP705 | Fat-remodeling | TGF-beta/COX-2 | siRNA | Polypeptide nanoparticle-mediated delivery | Subcutaneous | Phase 1 | Sirnaomics |

| Lung | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

VX-522 |

Cystic fibrosis |

CFTR

|

mRNA |

|

Oral inhalation |

Phase 1 |

Moderna/Vertex |

| |

ARO-RAGE |

Inflammatory lung disease (asthma, cystic fibrosis) |

Receptor for advanced glycation end products |

siRNA |

Ligand conjugated (targeted RNAi molecule, TRiM) |

Nebulizer |

Phase 1/2 |

Arrowhead |

| ARO-MMP | Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis | Matrix metalloproteinase (MMP7) | siRNA | Ligand conjugated (targeted RNAi molecule, TRiM) | Inhaled solution | Phase 1/2 | Arrowhead |

| Infectious diseases | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

mRNA-1975/mRNA-1982 |

Lyme disease |

Seven-valent approach to Borrelia burgdorferi |

mRNA |

|

Intramuscular |

Phase 1 |

Moderna |

| |

mRNA-1647 |

CMV |

Glycoprotein B, five subunits of CMV pentamer complex |

mRNA |

|

Intramuscular |

Phase 3 |

Moderna |

| |

mRNA-1893 |

Zika |

Premembrane and envelope of 2007 Zika virus |

mRNA, LNP |

|

Intramuscular |

Phase 2 |

Moderna |

| |

mRNA-1345 |

RSV |

Prefusion F glycoprotein |

mRNA |

|

Parenteral and intramuscular |

Phase 3 |

Moderna |

| RG6346 | Chronic hepatitis B | Hepatitis B virus surface antigen | GalNAc-siRNA | Subcutaneous | Phase 1 | Dicerna |

ALDH2, aldehyde dehydrogenase 2; ATXN3, ataxin-3; CFTR, cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator; COX-2, cyclooxygenase-2; DMPK, myotonic dystrophy protein kinase; DUX4, double homeobox 4; Fab, antigen-binding fragment; HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; HPV, human papillomavirus; HSD17B13, 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 13; IgA, immunoglobulin A; IL7, interleukin 7; KLKB1, kallikrein B1; NASH, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis; NY-ESO-1, New York esophageal squamous cell carcinoma-1; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus; SNCA, synuclein alpha; STAT3, signal transducer and activator of transcription 3; TGF-beta, transforming growth factor beta; UBE3A-AT2, ubiquitin protein ligase E3A antisense transcript; uRNA, uridine RNA.

FIG. 4.

New and existing technologies for nucleic acid therapeutics likely entering clinical trials during 2024. Color images are available online.

Liver

We anticipate substantial growth of liver-targeting NATs in the clinic given the robust productivity of hepatic-delivering entities that are currently available. In addition to GalNAc-conjugated siRNAs (Alnylam, Dicerna, Arrowhead), we may also see GalNAc-conjugated ASOs achieving additional clinical milestones (Ionis) [91,92]. Ionis is leading multiple programs using GalNAc-conjugated ASOs against new and validated targets, including Lipoprotein a, angiotensinogen, prekallikrein, and transthyretin to highlight a few [91,92]. Many studies investigating GalNAc-conjugated ASOs are in mid- to late-stage clinical trials [91,93]. The first GalNAc-conjugated ASO (WAINUA/epolontersen) (Ionis/AztraZeneca) targeting transthyretin for polyneuropathy of transthyretin-mediated amyloidosis was approved by the FDA in late 2023 [91]. One new modality that we can follow is the use of CRISPR-Cas9 for the treatment of hereditary angioedema and transthyretin amyloidosis by Intellia Therapeutics [94,95]. This therapy is currently in phase 2 trial using LNP formulation for liver delivery.

With the promising data being shown in patient trials, we might see regulatory approvals over the next several years, which would provide more therapeutic options for patients facing life-threatening diseases.

Central Nervous System

The most common modality under clinical investigation in the CNS is GapmeR ASOs, an approach that uses local delivery directly into the cerebrospinal fluid [96–98]. While ASOs and siRNA do not cross the blood–brain barrier, nusinersen demonstrated for the field that intrathecal delivery does distribute across the CNS, allowing for infrequent dosing with low drug amounts [99]. Through this success, nusinersen paved the way for developing even more CNS NATs. Using this clinically validated approach, Ionis is now expanding its work using ASOs now designed for new CNS targets, including alpha-synuclein, fused-in sarcoma, tau, and huntingtin, for Parkinson's disease, ALS, Alzheimer's disease, and Huntington's disease, respectively [97,100–104]. However, trials in this space are not always straightforward, as some of these trials have faced clinical hold due to toxicity at higher doses [29] or difficulties to predict when benefits will appear posttreatment [27]. For example, tominersen (Roche/Ionis) for Huntington's disease (HD) suffered from toxicity (measured by increased CSF neurofilament light chain levels) at high doses [29].

Furthermore, early tofersen (Biogen/Ionis) trials for ALS initially failed to meet clinical endpoints until the study was extended and it became clear that earlier treatment benefited patients [27].

A new technology accelerating the accessibility of CNS targets for nucleic acids is the novel lipophilic C16 conjugation developed by Alnylam [15,105]. In this approach, siRNA is linked to a lipophilic 2′-O-hexadecyl conjugate. C16-conjugation of siRNA is currently under phase 1 investigation for silencing amyloid precursor protein in early-onset Alzheimer's (NCT05231785). Another company looking to advance NATs for the CNS is Atalanta Therapeutics. Atalanta is developing the conjugate-free divalent siRNAs to enhance potency and durability in the CNS for various neurological indications [106].

While intrathecal injection of NATs has proven to be effective in the CNS, one goal within NATs is the application of a ligand or conjugate that can cross the blood–brain barrier to therapeutically allow systemic delivery of CNS-targeting NATs, which may be more clinically practical and less of a burden on patients [107]. Antibody conjugation is under active investigation for neurological targets, and early findings have shown exciting results. Intriguing preclinical results come from Denali Therapeutics, which develops and validates a modified transferrin–receptor antibody conjugation approach to deliver siRNA across the blood–brain barrier following a systemic administration (preprint: [108]).

Even with current modalities, one challenge in CNS delivery is the limited biodistribution to deep brain regions, including the caudate, putamen, and thalamus [99]. These regions are critical targets for Huntington's disease. The limited CSF perfusion or NAT accumulation in this region is usually a cause for the limited distribution and activity [109]. Approaches that utilize active uptake versus passive exposure from CSF perfusion and reduce rates of CSF clearance may improve NAT delivery to these critical brain regions.

With significant efforts in the preclinical and early clinical space for expanded options for CNS delivery, it will be a field to watch closely throughout the next few years.

Cardiovascular System

The current primary strategy of NATs for heart and vascular disease is to target the multitudes of liver-produced proteins that affect cardiovascular health. These include silencing liver targets that promote atherosclerosis, high blood pressure, or hyper/hypocoagulability [110–115]. This approach is used by Ionis, Alnylam, Arrowhead, and more in their Lipoprotein a, ApoE-IIII, Angiotensinogen, Antithrombin, and Factor XI programs [112,116–121]. These ASO- and siRNA-based trials are mostly in early clinical phases. Similarly, the proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9)-lowering approach through CRISPR-Cas9 [122] is in a phase 1 trial run by Verve Therapeutics. Preliminary results demonstrated profound cholesterol-lowering efficacy, including >80% PCSK9 lowering and >50% low-density lipoprotein in one patient [123]. Adverse effects were reported, demonstrating that while promising, more work needs to be done [123].

In an entirely different vascular disease, the siRNA therapy company Comanche Biopharma focuses on treating preeclampsia, a severe vascular disease during pregnancy that currently lacks effective treatments [124,125]. Comanche is utilizing a hydrophobic conjugate appended on siRNAs to target Soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 in the placenta to treat preeclampsia following a systemic administration. Currently, in first-in-human trials, using NATs to target vascular disease of the placenta presents a significant step forward for the field. The work done by Comanche also highlights that diversifying NAT conjugates may be needed to increase the cardiovascular system's access to NATs. With many ongoing therapeutic approaches in the clinic, we expect to see informative clinical results from these trials in the following years.

Eye

The eye is an organ of interest, since the first approved NATs were for cytomegalovirus (CMV)-induced retinitis [1,52,53]. As eyes are accessible, they were the focus of investigation for the first clinical trials with siRNAs. Early on, the nonmodified or marginally modified compounds were advanced into clinical trials, but the lack of stability, efficient delivery, and nonspecific activity limited clinical utility. While direct intravitreal injection of NATs for the eye is an option, it is invasive. For example, exon-skipping ASOs have been intravitreally injected into the eye with impressive on-target skipping efficacy [126]. With direct injection established, a new effort for eye-targeting NATs is improving delivery and formulation. There are ongoing clinical trials with topical gels and siRNA solution formulations for ischemic and corneal injury-related eye conditions (Ionis, Sylentis) [127–130]. Gel and liquid formulations offer a less-invasive option for patients than intravitreal injections and are very attractive [128]. As nonmodified siRNAs are used in these advanced programs, further investigations are necessary to explore the extent of clinical potential [129].

The next generation of compounds, including tetravalent- [131] and C16–modified siRNA [15], showed multimonth efficacy in different animal models. Next-generation chemistry offers the potential for highly durable treatments (every 6 to 12 months), where the invasiveness of the intraocular injection might be less of a factor. The potential for this area is enormous, and the comparatively low number of preclinical programs is likely due to the high level of negative predisposition toward NAT drugs in the field of ophthalmology due to the many failures of the early programs with nonmodified compounds. For example, in a Leber Hereditary Optic Neuropathy trial using an adeno-associated virus-based gene therapy, the therapy failed to meet clinical endpoints, but select patients are still being dosed to positive impacts (NCT02161380) [132]. Lastly, the most recent aptamer approved (2023) is for the eye [54,55]. The approval of IVERZAY highlights that though the eye was the first organ approved for NATs, there is more work to do, and the innovation in this space is prolific.

Cancers and Blood Disorders

In the cancer setting, oligonucleotides such as adjuvants (Moderna) and TLR9 agonists [131–135] are investigated as immune response stimulants. Similarly, within the field of oncology alone, there are over 50 clinical trials (primarily phase 1 and phase 2) investigating oligonucleotides for cancer therapeutics. These trials include systemic and intratumoral injection of ASOs, siRNA, and aptamers to modulate oncogene expression [133,134]. Some of the programs progress toward late phase 2, including STP705 for basal cell carcinoma and in situ squamous cell carcinoma (Sirnaomics) [135,136]. STP705 uses a polypeptide nanoparticle formulation of siRNA to enhance desired organ and tissue uptake [137,138]. STP705 is a combination of siRNA targeting transforming growth factor-beta and cyclooxygenase-2 individually using intralesional injections (NCT04669808, NCT04669808). In a phase 2 trial, following 6 weeks of treatment, >75% of patients with squamous cell lesions had a reduction in lesions with >80% lesion clearance in the highest-dosed group (NCT04669808) with good safety profile [135].

Follow-up on the more significant number of patients with biochemical quantitative readouts would be necessary to judge the long-term potential of this approach.

Furthermore, now in the clinic are CRISPR-based therapeutics for red blood cell diseases, including beta-cell thalassemia and sickle cell anemia called CASGEVY (Vertex and CRISPR Therapeutics) [86,87]. The CASGEVY therapeutic is introduced to stem cells ex vivo to decrease the expression of a known repressor of fetal hemoglobin, BCL11A, to increase fetal hemoglobin's expression and improve hemoglobin function [139]. With CASGEVY approved already in the United Kingdom for sickle cell and in the United States and United Kingdom for beta-cell thalassemia, the world will keep close tabs on the safety and efficacy of these therapeutics. Additional US/EU approvals might be coming soon.

Ex vivo, CRISPR-Cas9 has revolutionized chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T-cell therapy [140] preclinically for blood cancer, including leukemia and lymphoma [140,141]. Currently, six CAR-T cell therapies are approved by the FDA [142]. There is now a significant effort run by CRISPR Therapeutics to improve the gene therapy step of CAR-T cell development using CRISPR [143,144]. In clinical trials for applications in multiple blood cancer types, CRISPR-Cas9-mediated CAR-T cell therapies are underway and showing promising results [143,145]. While still under early investigation, we can hope for clinical advances and successes of NATs for oncological applications in the near future.

Although technically challenging, systemic delivery to tumors is a holy grail for the NATs. The ability of NATs to selectively and combatively regulate targets relying on highly similar pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics (PK/PD) profiles of individual compounds is precious for developing cancer therapeutics. The outstanding issue is delivery. Current approaches (antibody, peptide, and lipophilic conjugates) show limited tumor-specific uptake, with a single-digit percentage of drug tumor accumulation observed at best [146]. Advances in AI-based conjugate design, engineered antibodies, and peptides in the next generation would be necessary to tackle this issue.

Muscle

Antibody conjugation of siRNA is currently in clinical trials to improve muscle delivery [16,147]. The benefit of this approach is that it improves delivery to all body muscles through a systemic injection rather than many local muscle injections. Avidity, Denali, and Dyne Therapeutics are developing technologies to conjugate transferrin-binding antibodies to siRNA and/or ASOs [16,108]. Transferrin receptors are highly expressed in muscle, which leads to significant delivery of these conjugates to muscles throughout the body. Avidity is a leading work on coupled oligonucleotides to a monoclonal antibody (mAb) against the Transferrin-receptor1 (Tfr1) to induce endocytosis of NAT cargo [16]. Currently, preclinical validation of the Tfr1-mAb has been done in skeletal and cardiac muscles [16].

Dyne is using an antigen-binding fragment antibody for the transferrin receptor to deliver SSOs for DMD and myotonic dystrophy 1 (DM1) to muscle [148]. With Avidity's and Dyne's Transferrin receptor antibody-based platforms, both in phase 1/2 trials, we may not see Tfr1-based antibody technology gain approval soon. Still, it is one to closely watch in the clinic, given its exciting early success [16,108].

Antigen binding is also used by Aro Therapeutics for muscle disease. Aro's approach uses an engineered version of extracellular matrix protein tenascin C, named Centryin, to deliver NAT payload to select tissues [149]. Aro has developed a centyrin-siRNA program for Pompe disease, targeting Gys1, now in phase 1 trial.

Cationic peptide conjugation of PMO ASOs is another active area of preclinical and clinical effect to improve on-target splicing in diseases, including DMD and DM1 (Serepta, PepGen, Entrada) [150,151]. Cationic peptides have been associated with hypomagnesemia in patients in current trials [152]. With strong efficacy preclinically, a wide variety of peptide combinations are under clinical investigation and have been summarized elsewhere [150,151]. Overall, the muscle may soon be an area with dramatic NAT movement and is certainly one to watch.

Kidney

Targeting the kidney has been a long-time goal for the field. As an organ that facilitates the clearance of nucleic acids for excretion, kidneys are often an organ to avoid. However, getting into the kidney parenchyma is interesting as it can mitigate many diseases, such as high blood pressure, parenchymal kidney disease, and glomerulonephritis. A reasonable fraction of nonconjugated stabilized siRNAs and shorter (nonserum binding) ASOs accumulate in kidney proximal tubule epithelia, the strategy early on explored by Ionis for kidney delivery [153]. One of the additional challenges with this approach is nonproductive entrapment, where the PK/PD ratio of oligonucleotide is significantly higher than in other tissues, indicating nonproductive entrapment [17].

Currently, no approach for direct kidney-targeting NATs is approved or in clinical trials, but many technologies are under investigation preclinically [154,155]. There are, however, programs to improve kidney health by targeting the expression of genes in other tissues (RIVFLOZA, described in the siRNA section above). This indirect approach for targeting the kidney can be applied to other diseases and provide insight into how best to use the kidney's physiology to our advantage.

Skin

Skin diseases are among the most common of all human health afflictions and affect almost 900 million people in the world at any time [156,157]. Many therapeutic applications for NATs can be applied to the skin to treat multiple conditions with infectious, oncological, autoimmune, or trauma-based etiologies. Some work has been established in this space, including siRNAs under investigation to promote wound healing [158,159]. OliX Pharmaceuticals is using intradermal delivery of hydrophobic, modified siRNA (OLX101) targeting connective tissue growth factor directly into hypertrophic and keloid scar lesions (NCT04877756). The clinical data would be necessary to evaluate the potential of this approach for scar reduction and improved wound healing [160]. A new company, Aldena, focuses entirely on NATs for skin diseases, hoping to utilize the unique siRNA pharmacokinetic profile. Local administration supports sustained local efficacy with limited systemic exposure, thus enhancing novel drugs' therapeutic index and safety while targeting clinically validated pathways.

Aldena uses unique conjugates to enhance local uptake across skin layers to silence targets responsible for skin diseases without systemic exposure, which drives most safety limitations. Their strategy relies on intradermal injections or star-shaped microneedles that induce temporary local perforations in the skin that allow for biomolecule uptake, including NATs [161–163]. With a substantial unmet clinical need for autoimmune and cancerous dermatologic conditions, we will hopefully see significant clinical progress of NATs for the skin in upcoming years.

Lung

Preclinically, lung delivery and activity of ASOs and siRNA have been validated [15,164,165]. This work took advantage of intratracheal administration and multivalent structures that improve the retention of NATs in the lung. Clinically, the most advanced program to date is the siRNA-targeting receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) administered by bronchiolar alveolar lavage from Arrowhead Pharmaceuticals. ARO-RAGE is currently under investigation for inflammatory pulmonary diseases (asthma, inflammatory pulmonary, and much-obstructive disorders) [166,167]. The ARO-RAGE program likely uses a lipophilic ligand conjugate but no disclosure has been made. Recent data from the phase 1/2 trials reported >90% target knockdown in the highest dose at one month postinhaled delivery [168]. The lung can also be indirectly targeted by silencing related genes/proteins in the liver, such as genes associated with the fibrosing lung disease alpha-1 antitrypsin (AAT) disorder. Fazisiren, a Serpin1 targeting GalNAc-conjugated siRNA, is under clinical investigation by Arrowhead and Takeda Pharmaceutical Company for AAT [169,170].

Nucleic Acids for Rare Diseases

Finally, the near future of nucleic acid therapies hopefully includes new drugs for conditions ranging from common to ultrarare [171]. Over the following years, we can expect advancement, particularly in rare diseases, through efforts of patient advocacy groups, safety validation of existing platforms, and increased open access to data across the NAT community [172,173]. While NATs for common disorders can silence genes that are aberrantly expressed in hereditary conditions or commonly expressed by contributing to pathology, NATs for rare and ultrarare diseases often require SNP-specific therapeutics and patients must navigate complex regulatory hurdles [174] with recent progress in genomics of ultrarare disease and undiagnosed disease consortium [175], the disease-causing genes have been defined to ∼4,000 out of 6,000 disease. The potential for the applications of oligonucleotide therapeutics is significant, even if only a fraction of the diseases are mechanistically targetable.

One crucial example is Milasen (mentioned previously), the SSO designed based on a mutation in the patient, Mila, which led to her Batten disease [44]. Milasen became the first n-of-1 ASO FDA-approved in 2018 [44]. Beyond approval, Milasen clinically showed some benefit by reducing the number of Mila's daily seizures [44]. The approval and clinical efficacy of Milasen thrust the field of n-of-1 and rare disease NATs into the main stage. They paved the way for thousands of future therapies for children and families with rare diseases. A majority of ultrarare diseases are in the area of pediatric neurodegeneration, where NAT applications are technically and clinically proven.

The challenge with rare diseases is that each unique sequence of common ASO or siRNA modalities is currently considered a unique drug that requires its own safety and efficacy validation, regardless of whether the rest of the drug is similar to preapproved drugs [176]. This requirement is partially justified by profoundly different safety profiles observed for different sequences of identical chemical configurations, specifically for single-stranded NATs.

Groups such as the N = 1 Collaborative and n-Lorem are public–private–academic–industry collaborations to create a rare disease NAT development platform that can scale up rare disease NATs [177–178]. The primary approach at this time is splice-switching SNPs, where ASOs with the same chemistry can have established safety profiles. The goal is to shorten the time to get to the patients, allowing them to get immediate access to life-saving or lifespan-increasing therapies. With an improved process, the field could eliminate the years-long timeline of safety validation. It can apply an already-approved modality with an established safety profile to a new condition in a “plug-and-play” throughput system [177]. This work requires diseases with SNPs or pathogenic variants that are genetically amenable to ASO-based therapy and extensive preclinical validation using in vitro models [176]. Once ASOs are screened and a potent sequence is identified, the ASO can move toward preclinical development.

Currently, nucleic acids for rare diseases use this small but mighty approach to scale up NAT for rare and ultrarare conditions. With the foundation of interdisciplinary collaboration and scientific vigor established by early rare disease NAT pioneers, we can hope that a wide variety of rare conditions can gain timely access to practical NATs.

Conclusions

Taken together, now is an exciting time for NATs. We hope to see more instances of NATs being used as long-term therapies for the prevention of common diseases such as hypertension and hyperlipidemia (leading factors toward heart disease risk), health issues with significant disease burdens such as red blood cell thalassemia and sickle cell, as well as for ultrarare metabolic, neurological, or connective tissue diseases. With chemical and biochemical innovation as the backbone (literally) and the collaboration between science and medicine as the fuel, we are excited to see the coming years bring NATs to reach new heights, with the understanding that clinical progression may bring a lot of surprises.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Annemieke Aartsma-Rus and Qi Tang for edits and feedback on the document. The authors acknowledge BioRender for support in creating Fig. 3.

Author Disclosure Statement

J.B. and H.H.F. are trainee representatives for the Oligonucleotide Therapeutics Society Board of Directors. A.K. is a cofounder of Atalanta and Comanche, where she has a financial stake. A.K. serves on the scientific advisory board of Atalanta, Prime Medicine, EVOX Therapeutics, Alltrna, Aldena, and Comanche Pharmaceuticals.

Funding Information

J.B. is supported by NINDS F31 NS132424-01. H.H.F. is supported by the Hereditary Disease Foundation Postdoctoral Fellowship program. A.K. is supported by NIH R01 NS104022.

References

- 1. Roehr B. (1998). Fomivirsen approved for CMV retinitis. J Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care 4:14–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hofman CR and Corey DR. (2023). Targeting RNA with synthetic oligonucleotides: clinical success invites new challenges. Cell Chem Biol (Epub ahead of print). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kulkarni JA, Witzigmann D, Thomson SB, Chen S, Leavitt BR, Cullis PR and van der Meel R. (2021). The current landscape of nucleic acid therapeutics. Nat Nanotechnol 16:630–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Egli M and Manoharan M. (2023). Chemistry, structure and function of approved oligonucleotide therapeutics. Nucleic Acids Res 51:2529–2573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Corydon IJ, Fabian-Jessing BK, Jakobsen TS, Jørgensen AC, Jensen EG, Askou AL, Aagaard L and Corydon TJ. (2023). 25 Years of maturation: a systematic review of RNAi in the clinic. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 33:469–482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yamada Y. (2021). Nucleic acid drugs: current status, issues, and expectations for exosomes. Cancers (Basel) 13:5002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Deleavey GF and Damha MJ. (2012). Designing chemically modified oligonucleotides for targeted gene silencing. Chem Biol 19:937–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chi X, Gatti P and Papoian T. (2017). Safety of antisense oligonucleotide and siRNA-based therapeutics. Drug Discov Today 22:823–833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Khvorova A and Watts JK. (2017). The chemical evolution of oligonucleotide therapies of clinical utility. Nat Biotechnol 35:238–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wan C, Allen TM and Cullis PR. (2014). Lipid nanoparticle delivery systems for siRNA-based therapeutics. Drug Deliv Transl Res 4:74–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kulkarni JA, Witzigmann D, Chen S, Cullis PR and van der Meel R. (2019). Lipid nanoparticle technology for clinical translation of siRNA therapeutics. Acc Chem Res 52:2435–2444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cui H, Zhu X, Li S, Wang P and Fang J. (2021). Liver-targeted delivery of oligonucleotides with N-acetylgalactosamine conjugation. ACS Omega 6:16259–16265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Morell AG, Gregoriadis G, Scheinberg IH, Hickman J and Ashwell G. (1971). The role of sialic acid in determining the survival of glycoproteins in the circulation. J Biol Chem 246:1461–1467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nair JK, Willoughby JL, Chan A, Charisse K, Alam MR, Wang Q, Hoekstra M, Kandasamy P, Kel'in AV, et al. (2014). Multivalent N-acetylgalactosamine-conjugated siRNA localizes in hepatocytes and elicits robust RNAi-mediated gene silencing. J Am Chem Soc 136:16958–16961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Brown KM, Nair JK, Janas MM, Anglero-Rodriguez YI, Dang LTH, Peng H, Theile CS, Castellanos-Rizaldos E, Brown C, et al. (2022). Expanding RNAi therapeutics to extrahepatic tissues with lipophilic conjugates. Nat Biotechnol 40:1500–1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Malecova B, Burke RS, Cochran M, Hood MD, Johns R, Kovach PR, Doppalapudi VR, Erdogan G, Arias JD, et al. (2023). Targeted tissue delivery of RNA therapeutics using antibody–oligonucleotide conjugates (AOCs). Nucleic Acids Res 51:5901–5910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Biscans A, Coles A, Haraszti R, Echeverria D, Hassler M, Osborn M and Khvorova A. (2019). Diverse lipid conjugates for functional extra-hepatic siRNA delivery in vivo. Nucleic Acids Res 47:1082–1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Seth PP, Tanowitz M and Bennett CF. (2019). Selective tissue targeting of synthetic nucleic acid drugs. J Clin Invest 129:915–925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Winkler J. (2013). Oligonucleotide conjugates for therapeutic applications. Ther Deliv 4:791–809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Crooke ST. (2017). Molecular mechanisms of antisense oligonucleotides. Nucleic Acid Ther 27:70–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Geary RS, Henry SP and Grillone LR. (2002). Fomivirsen: clinical pharmacology and potential drug interactions. Clin Pharmacokinet 41:255–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chambergo-Michilot D, Alur A, Kulkarni S and Agarwala A. (2022). Mipomersen in familial hypercholesterolemia: an update on health-related quality of life and patient-reported outcomes. Vasc Health Risk Manag 18:73–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Benson MD, Waddington-Cruz M, Berk JL, Polydefkis M, Dyck PJ, Wang AK, Planté-Bordeneuve V, Barroso FA, Merlini G, et al. (2018). Inotersen treatment for patients with hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis. N Engl J Med 379:22–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gales L. (2019). Tegsedi (inotersen): an antisense oligonucleotide approved for the treatment of adult patients with hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 12:78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Miller T, Cudkowicz M, Shaw PJ, Andersen PM, Atassi N, Bucelli RC, Genge A, Glass J, Ladha S, et al. (2020). Phase 1–2 trial of antisense oligonucleotide tofersen for SOD1 ALS. N Engl J Med 383:109–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Miller TM, Cudkowicz ME, Genge A, Shaw PJ, Sobue G, Bucelli RC, Chiò A, Van Damme P, Ludolph AC, et al. (2022). Trial of antisense oligonucleotide tofersen for SOD1 ALS. N Engl J Med 387:1099–1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. van Roon-Mom W, Ferguson C and Aartsma-Rus A. (2023). From failure to meet the clinical endpoint to U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval: 15th antisense oligonucleotide therapy approved qalsody (tofersen) for treatment of SOD1 mutated amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nucleic Acid Ther 33:234–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hagedorn PH, Brown JM, Easton A, Pierdomenico M, Jones K, Olson RE, Mercer SE, Li D, Loy J, et al. (2022). Acute neurotoxicity of antisense oligonucleotides after intracerebroventricular injection into mouse brain can be predicted from sequence features. Nucleic Acid Ther 32:151–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tabrizi SJ, Estevez-Fraga C, van Roon-Mom WMC, Flower MD, Scahill RI, Wild EJ, Muñoz-Sanjuan I, Sampaio C, Rosser AE and Leavitt BR. (2022). Potential disease-modifying therapies for Huntington's disease: lessons learned and future opportunities. Lancet Neurol 21:645–658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Helm J, Schöls L and Hauser. S (2022). Towards personalized allele-specific antisense oligonucleotide therapies for toxic gain-of-function neurodegenerative diseases. Pharmaceutics 14:1708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Finkel RS, Mercuri E, Darras BT, Connolly AM, Kuntz NL, Kirschner J, Chiriboga CA, Saito K, Servais L, et al. (2017). Nusinersen versus sham control in infantile-onset spinal muscular atrophy. N Engl J Med 377:1723–1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Disterer P, Kryczka A, Liu Y, Badi YE, Wong JJ, Owen JS and Khoo B. (2014). Development of therapeutic splice-switching oligonucleotides. Hum Gene Ther 25:587–598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Godfrey C, Desviat LR, Smedsrød B, Piétri-Rouxel F, Denti MA, Disterer P, Lorain S, Nogales-Gadea G, Sardone V, et al. (2017). Delivery is key: lessons learnt from developing splice-switching antisense therapies. EMBO Mol Med 9:545–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Clemens PR, Rao VK, Connolly AM, Harper AD, Mah JK, McDonald CM, Smith EC, Zaidman CM, Nakagawa T and Hoffman EP. (2022). Long-term functional efficacy and safety of viltolarsen in patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Neuromuscul Dis 9:493–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Clemens PR, Rao VK, Connolly AM, Harper AD, Mah JK, Smith EC, McDonald CM, Zaidman CM, Morgenroth LP, et al. (2020). Safety, tolerability, and efficacy of viltolarsen in boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy amenable to exon 53 skipping: a phase 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol 77:982–991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lim KR, Maruyama R and Yokota T. (2017). Eteplirsen in the treatment of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Drug Des Devel Ther 11:533–545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Roshmi RR and Yokota T. (2019). Viltolarsen for the treatment of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Drugs Today (Barc) 55:627–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Scaglioni D, Catapano F, Ellis M, Torelli S, Chambers D, Feng L, Beck M, Sewry C, Monforte M, et al. (2021). The administration of antisense oligonucleotide golodirsen reduces pathological regeneration in patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Acta Neuropathol Commun 9:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Servais L, Mercuri E, Straub V, Guglieri M, Seferian AM, Scoto M, Leone D, Koenig E, Khan N, et al. (2022). Long-term safety and efficacy data of golodirsen in ambulatory patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy amenable to exon 53 skipping: a first-in-human, multicenter, two-part, open-label, phase 1/2 trial. Nucleic Acid Ther 32:29–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Shirley M. (2021). Casimersen: first approval. Drugs 81:875–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wagner KR, Kuntz NL, Koenig E, East L, Upadhyay S, Han B and Shieh PB. (2021). Safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of casimersen in patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy amenable to exon 45 skipping: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-titration trial. Muscle Nerve 64:285–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zakeri SE, Pradeep SP, Kasina V, Laddha AP, Manautou JE and Bahal R. (2022). Casimersen for the treatment of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Trends Pharmacol Sci 43:607–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Aartsma-Rus A. (2023). The future of exon skipping for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Hum Gene Ther 34:372–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kim J, Hu C, Moufawad El Achkar C, Black LE, Douville J, Larson A, Pendergast MK, Goldkind SF, Lee EA, et al. (2019). Patient-customized oligonucleotide therapy for a rare genetic disease. N Engl J Med 381:1644–1652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bode C, Zhao G, Steinhagen F, Kinjo T and Klinman DM. (2011). CpG DNA as a vaccine adjuvant. Expert Rev Vaccines 10:499–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Qiao D, Li L, Liu L and Chen Y. (2022). Universal and translational nanoparticulate CpG adjuvant. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 14:50592–50600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lee G-H and Lim S-G. (2021). CpG-adjuvanted hepatitis B vaccine (HEPLISAV-B®) update. Expert Rev Vaccines 20:487–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Shearer JD, Henning L, Sanford DC, Li N, Skiadopoulos MH, Reece JJ, Ionin B and Savransky V. (2021). Efficacy of the AV7909 anthrax vaccine candidate in guinea pigs and nonhuman primates following two immunizations two weeks apart. Vaccine 39:1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Adachi T and Nakamura. Y (2019). Aptamers: a review of their chemical properties and modifications for therapeutic application. Molecules 24:4229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Keefe AD, Pai S and Ellington A. (2010). Aptamers as therapeutics. Nat Rev Drug Discov 9:537–550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Odeh F, Nsairat H, Alshaer W, Ismail MA, Esawi E, Qaqish B, Bawab AA and Ismail. SI (2019). Aptamers chemistry: chemical modifications and conjugation strategies. Molecules 25:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Fraunfelder FW. (2005). Pegaptanib for wet macular degeneration. Drugs Today (Barc) 41:703–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Vinores SA. (2006). Pegaptanib in the treatment of wet, age-related macular degeneration. Int J Nanomedicine 1:263–268. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Jaffe GJ, Westby K, Csaky KG, Monés J, Pearlman JA, Patel SS, Joondeph BC, Randolph J, Masonson H and Rezaei KA. (2021). C5 inhibitor avacincaptad pegol for geographic atrophy due to age-related macular degeneration: a randomized pivotal phase 2/3 trial. Ophthalmology 128:576–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Patel SS, Lally DR, Hsu J, Wykoff CC, Eichenbaum D, Heier JS, Jaffe GJ, Westby K, Desai D, et al. (2023). Avacincaptad pegol for geographic atrophy secondary to age-related macular degeneration: 18-month findings from the GATHER1 trial. Eye (Lond) 37:3551–3557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kraemer S, Vaught JD, Bock C, Gold L, Katilius E, Keeney TR, Kim N, Saccomano NA, Wilcox SK, et al. (2011). From SOMAmer-based biomarker discovery to diagnostic and clinical applications: a SOMAmer-based, streamlined multiplex proteomic assay. PLoS One 6:e26332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Becker WR, Ober-Reynolds B, Jouravleva K, Jolly SM, Zamore PD and Greenleaf. WJ (2019). High-throughput analysis reveals rules for target RNA binding and cleavage by AGO2. Mol Cell 75:741–755.e711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Agrawal N, Dasaradhi PVN, Mohmmed A, Malhotra P, Bhatnagar Raj K and Mukherjee Sunil K. (2003). RNA interference: biology, mechanism, and applications. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 67:657–685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Matranga C, Tomari Y, Shin C, Bartel DP and Zamore PD. (2005). Passenger-strand cleavage facilitates assembly of siRNA into Ago2-containing RNAi enzyme complexes. Cell 123:607–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Ahn I, Kang CS and Han J. (2023). Where should siRNAs go: applicable organs for siRNA drugs. Exp Mol Med 55:1283–1292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Urits I, Swanson D, Swett MC, Patel A, Berardino K, Amgalan A, Berger AA, Kassem H, Kaye AD and Viswanath O. (2020). A review of patisiran (ONPATTRO®) for the treatment of polyneuropathy in people with hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis. Neurol Ther 9:301–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Zhang X, Goel V, Attarwala H, Sweetser MT, Clausen VA and Robbie GJ. (2020). Patisiran pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and exposure-response analyses in the phase 3 APOLLO trial in patients with hereditary transthyretin-mediated (hATTR) amyloidosis. J Clin Pharmacol 60:37–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Adams D, Polydefkis M, González-Duarte A, Wixner J, Kristen AV, Schmidt HH, Berk JL, Losada López IA, Dispenzieri A, et al. (2021). Long-term safety and efficacy of patisiran for hereditary transthyretin-mediated amyloidosis with polyneuropathy: 12-month results of an open-label extension study. Lancet Neurol 20:49–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Adams D, Tournev IL, Taylor MS, Coelho T, Planté-Bordeneuve V, Berk JL, González-Duarte A, Gillmore JD, Low SC, et al. (2023). Efficacy and safety of vutrisiran for patients with hereditary transthyretin-mediated amyloidosis with polyneuropathy: a randomized clinical trial. Amyloid 30:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Garrelfs SF, Frishberg Y, Hulton SA, Koren MJ, O'Riordan WD, Cochat P, Deschênes G, Shasha-Lavsky H, Saland JM, et al. (2021). Lumasiran, an RNAi therapeutic for primary hyperoxaluria type 1. N Engl J Med 384:1216–1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Goldfarb DS, Lieske JC, Groothoff J, Schalk G, Russell K, Yu S and Vrhnjak. B (2023). Nedosiran in primary hyperoxaluria subtype 3: results from a phase I, single-dose study (PHYOX4). Urolithiasis 51:80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Hayes W, Sas DJ, Magen D, Shasha-Lavsky H, Michael M, Sellier-Leclerc AL, Hogan J, Ngo T, Sweetser MT, et al. (2023). Efficacy and safety of lumasiran for infants and young children with primary hyperoxaluria type 1: 12-month analysis of the phase 3 ILLUMINATE-B trial. Pediatr Nephrol 38:1075–1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Hulton SA, Groothoff JW, Frishberg Y, Koren MJ, Overcash JS, Sellier-Leclerc AL, Shasha-Lavsky H, Saland JM, Hayes W, et al. (2022). Randomized clinical trial on the long-term efficacy and safety of lumasiran in patients with primary hyperoxaluria type 1. Kidney Int Rep 7:494–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Koenig W, Ray KK, Landmesser U, Leiter LA, Schwartz GG, Wright RS, Conde LG, Han J and Raal. FJ (2023). Efficacy and safety of inclisiran in patients with cerebrovascular disease: ORION-9, ORION-10, and ORION-11. Am J Prev Cardiol 14:100503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Li J, Lei X, Li Z and Yang. X (2023). Effectiveness and safety of inclisiran in hyperlipidemia treatment: an overview of systematic reviews. Medicine (Baltimore) 102:e32728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Liu A, Zhao J, Shah M, Migliorati JM, Tawfik SM, Bahal R, Rasmussen TP, Manautou JE and Zhong X-b. (2022). Nedosiran, a candidate siRNA drug for the treatment of primary hyperoxaluria: design, development, and clinical studies. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci 5:1007–1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Ray KK, Troquay RPT, Visseren FLJ, Leiter LA, Scott Wright R, Vikarunnessa S, Talloczy Z, Zang X, Maheux P, et al. (2023). Long-term efficacy and safety of inclisiran in patients with high cardiovascular risk and elevated LDL cholesterol (ORION-3): results from the 4-year open-label extension of the ORION-1 trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 11:109–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Ray KK, Wright RS, Kallend D, Koenig W, Leiter LA, Raal FJ, Bisch JA, Richardson T, Jaros M, et al. (2020). Two phase 3 trials of inclisiran in patients with elevated LDL cholesterol. N Engl J Med 382:1507–1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Ventura P, Bonkovsky HL, Gouya L, Aguilera-Peiró P, Montgomery Bissell D, Stein PE, Balwani M, Anderson DKE, Parker C, et al. (2022). Efficacy and safety of givosiran for acute hepatic porphyria: 24-month interim analysis of the randomized phase 3 ENVISION study. Liver Int 42:161–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Baum MA, Langman C, Cochat P, Lieske JC, Moochhala SH, Hamamoto S, Satoh H, Mourani C, Ariceta G, et al. (2023). PHYOX2: a pivotal randomized study of nedosiran in primary hyperoxaluria type 1 or 2. Kidney Int 103:207–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Lai C, Pursell N, Gierut J, Saxena U, Zhou W, Dills M, Diwanji R, Dutta C, Koser M, et al. (2018). Specific inhibition of hepatic lactate dehydrogenase reduces oxalate production in mouse models of primary hyperoxaluria. Mol Ther 26:1983–1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Jinek M, Chylinski K, Fonfara I, Hauer M, Doudna JA and Charpentier E. (2012). A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science 337:816–821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Komor AC, Kim YB, Packer MS, Zuris JA and Liu DR. (2016). Programmable editing of a target base in genomic DNA without double-stranded DNA cleavage. Nature 533:420–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Gaudelli NM, Komor AC, Rees HA, Packer MS, Badran AH, Bryson DI and Liu DR. (2017). Programmable base editing of A•T to G•C in genomic DNA without DNA cleavage. Nature 551:464–471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Anzalone AV, Randolph PB, Davis JR, Sousa AA, Koblan LW, Levy JM, Chen PJ, Wilson C, Newby GA, et al. (2019). Search-and-replace genome editing without double-strand breaks or donor DNA. Nature 576:149–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Pattanayak V, Lin S, Guilinger JP, Ma E, Doudna JA and Liu DR. (2013). High-throughput profiling of off-target DNA cleavage reveals RNA-programmed Cas9 nuclease specificity. Nat Biotechnol 31:839–843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Zuris JA, Thompson DB, Shu Y, Guilinger JP, Bessen JL, Hu JH, Maeder ML, Joung JK, Chen Z-Y and Liu DR. (2015). Cationic lipid-mediated delivery of proteins enables efficient protein-based genome editing in vitro and in vivo. Nat Biotechnol 33:73–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Anzalone AV, Koblan LW and Liu DR. (2020). Genome editing with CRISPR–Cas nucleases, base editors, transposases and prime editors. Nat Biotechnol 38:824–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Asmamaw M and Zawdie B. (2021). Mechanism and applications of CRISPR/Cas-9-mediated genome editing. Biologics 15:353–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Yip BH. (2020). Recent advances in CRISPR/Cas9 delivery strategies. Biomolecules 10:839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Esrick EB, Lehmann LE, Biffi A, Achebe M, Brendel C, Ciuculescu MF, Daley H, MacKinnon B, Morris E, et al. (2020). Post-transcriptional genetic silencing of BCL11A to treat sickle cell disease. N Engl J Med 384:205–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Frangoul H, Altshuler D, Cappellini MD, Chen Y-S, Domm J, Eustace BK, Foell J, de la Fuente J, Grupp S, et al. (2020). CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing for sickle cell disease and β-thalassemia. N Engl J Med 384:252–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Li T, Yang Y, Qi H, Cui W, Zhang L, Fu X, He X, Liu M, P-f Li and Yu. T (2023). CRISPR/Cas9 therapeutics: progress and prospects. Signal Transduct Targeted Ther 8:36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Coller J and Ignatova. Z (2023). tRNA therapeutics for genetic diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov (online ahead of print). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Anastassiadis T and Köhrer C. (2023). Ushering in the era of tRNA medicines. J Biol Chem 299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]