Abstract

Background

Genital pain treatment regimens range from local or systemic pharmacological to non-pharmacological, manual and psychosexual therapies with poor to moderate evidence for their efficiency. The aim of this study was to evaluate the subjective therapeutic response (genital pain relief) of different treatment modalities for vulvodynia and the most prevalent other vulvar pathologies, chronic vulvar eczema and lichen sclerosus by means of a cross-sectional survey.

Material and Methods

A questionnaire-based cohort study that included 128 vulvodynia, 116 eczema and 79 lichen sclerosus patients was used. All patients attended the vulvar clinic at the University Hospital of Zurich. The patients who had been treated were surveyed from January to October 2022, using a customized online questionnaire consisting of 37 questions on symptoms and treatment outcomes for guideline-recommended treatment modalities. The study was approved by the Cantonal Ethics Review Board of Zurich.

Results

Altogether, 41 patients with vulvodynia, 37 with vulvar eczema and 23 with lichen sclerosus returned the questionnaire. The three groups were similar regarding pain characteristics and comorbidities. All three patient groups reported having benefited from non-pharmacological treatment (improvement rate vulvodynia 54%; eczema 51%; lichen sclerosus 58%), from topical (55%; 55%; 75%) and from locally invasive (46%; 66%; 50%) treatments. Overall, there was no significant difference in subjective treatment outcome between non-pharmacological, locally invasive, and topical treatments for vulvodynia, eczema, and lichen sclerosus. However, the use of oral medication was reported to be significantly less effective (p-value 0.050).

Conclusion

In conclusion, we found that in the patients’ perception, topical, invasive and non-pharmacological treatments, but not oral medications, are helpful for genital pain relief in women with vulvodynia, vulvar eczema, and lichen sclerosus. Therefore, we recommend an escalating therapy approach with first-line non-pharmacological treatments together with topical therapies.

Keywords: genital pain, vestibulodynia, therapy, patient reported treatment outcome, survey

Introduction

The 2015 Classification of Chronic Vulvar Pain proposes two main categories: vulvar pain related to a specific disorder (eg inflammatory, neoplastic, traumatic, infection related, neurological) and vulvodynia, defined as idiopathic vulvar pain of at least three months’ duration.1 Vulvodynia affects approximately 8–16% of premenopausal women.2,3 Although a clear cause has not yet been identified, several theories have emerged regarding the etiology of vulvodynia.4 Similar to chronic pelvic pain, central sensitization seems to play an important role in the genesis of vulvar pain.5,6 Heightened pelvic floor muscle tone and psychosexual disturbances have been identified as trigger factors for vulvodynia.7–9 Vulvodynia, however, is widely considered to be the result of a multifactorial process.1 Genital pain is a common symptom that is also seen in other vulvar diseases, eg in the most prevalent ones, chronic genital eczema and lichen sclerosus. In genital eczema or lichen sclerosus, pain and itch may be locally mediated through chronically inflammatory T-cell infiltrates releasing interleukins in the skin and mucosa.10,11 Lichen sclerosus is also hypothesized to originate from an autoimmune etiology or impaired wound healing processes.12 Chronic vulvar eczema can also arise due to a number of causes, eg atopic, irritant, allergic or seborrheic.13 Thus, for the two genital pain syndromes genital eczema and lichen sclerosus, the etiology is still unknown and triggering factors, eg mechanical irritation, favor their development. Chronic genital eczema and lichen sclerosus also affect sexual life due to fear of pain or lack of elasticity in the skin surrounding the introitus and occur more frequently in younger-aged women along with a burning pain.14,15

According to international guidelines, there is no “gold standard” therapy for patients with vulvodynia and vulvar eczema at this juncture; instead, a multimodal management is proposed.13,16 The treatment of lichen sclerosus is evidence-based, consisting of topical steroids, although recently, laser therapies have also started emerging.17,18 For benign vulvar conditions, different approaches exist ranging from non-pharmacological to pharmacological or surgical treatments.13,19 For vulvodynia, pharmacological therapies include topical pain modifiers, such as lidocaine or amitriptyline cream, botulinum neurotoxin injections and oral pain modifiers like tricyclic antidepressants or antiepileptics. There is low to moderate evidence of any treatment benefit.20–25 Physical therapy modalities are effective in decreasing pain.26,27 There is, however, clear evidence linking vulvodynia to pelvic floor muscle dysfunction.28 Further, there seems to be strong evidence for psychological treatments reducing vulvar pain.29,30 Among surgical treatment approaches, vulvar vestibulectomy has been studied and proposed in the context of localized vulvodynia; it is, however, contraindicated for generalized pain disorders.31,32 The evidence for particular vulvar eczema treatments is also sparse; avoidance of irritants and topical steroids are the two most commonly used.16 Present treatment recommendations are mostly based on clinical experience only, and are favored depending on the treating physician.33,34 It is equally important to consider the patient’s personal preferences, as this leads to a higher therapeutic alliance between the patient and the health provider, which has been shown to increase patient satisfaction and improve adherence to treatment, ultimately improving clinical outcomes.35,36

For all the reasons reported above, much is still unknown about the exact origin of genital pain and the therapeutic benefits of individual therapies. As a first step towards closing this gap, we therefore conducted a qualitative survey to investigate the subjectively-experienced success of various therapeutic approaches, as well as the pain characteristics and comorbidities among three highly prevalent chronic vulvar pain diseases. Our aim in this was to explore subjective therapeutic success regarding pain relief. Patients’ experiences represent a valuable resource in improving pre-therapeutic counseling on the different treatment approaches.

Materials and Methods

Study Collective and Study Design

Patients attended the interdisciplinary vulva clinic, a tertiary referral center of the Department of Gynecology at the University Hospital Zurich, Switzerland, from January 2014 to December 2020, which means that study participants had received between 2 and 8 years of treatment according to the patient’s chart. All patients provided written informed consent to participate. This study was conducted in compliance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was approved by the local institutional review board (Cantonal Ethics Review Board of Zurich; approval number 2019–00976) on the 30th of September 2019.

This monocentric cohort study was conducted with an inclusion total of 128 patients with vulvodynia, 116 patients with genital eczema and 79 patients with lichen sclerosus. From January 2014 to December 2020, a total of 128 patients with vulvodynia attended the above-mentioned consultation. Patients with chronic genital eczema and lichen sclerosus were selected to match the age of the vulvodynia collective; this therefore resulted in a reduction in sample size for both aforementioned groups. The inclusion criteria for a patient in the study were as follows: female aged >18 years fulfilling criteria for diagnosis of vulvodynia, chronic genital eczema or lichen sclerosus; after undergoing standard diagnosis in the vulva clinic, received one or several treatments for vulvar disease; has a reasonable command of the German language. Patients visited the interdisciplinary vulvar clinic upon referral. The treatment plans in the vulvar consultations adhere to European guidelines and are started after shared decision-making with the patients including treatment choices, benefits and risks and assumed long-term effects. After a successful treatment plan is implemented, patients are informed they should revisit the clinic if symptoms persist; in cases of symptom relief, they are discharged to their referral doctors. Follow-up visits are scheduled upon request and medical need (number (n) of visits for study patients according to clinic data: n1 65%, n2–4 29%, n≥5 6%).

The typical treatment plan at the vulvar clinic of the University Hospital of Zurich follows a non-validated algorithmic approach, starting with non-pharmacological and topical applications, progressing to minimally-invasive and oral medical treatments and, in cases of repeated failure, to surgical interventions. The sequence of treatments varies and starts with the most promising therapy, ie topical therapies in the eczema and lichen sclerosus group and topical combined with non-pharmacological treatments in the vulvodynia group. Especially in the vulvodynia group, a phenotype-based approach is considered, such as central or peripheral pain-modulating, psychosexual or muscle relaxant therapy dependent on the most prevalent symptom. Non-pharmacological therapies involve changing behavior, complementary medicine, physiotherapy, and psychosexual therapy. Medical therapies comprise topical applications like local lidocaine, local amitriptyline, steroid creams, local estrogen, or topical lubricating cream. Oral medical therapies are antidepressants and neuroleptics and are used in a later escalating step. All medical applications are prescribed according to manufacturers’ instructions with evaluation after six weeks of administration. Minimally invasive treatments included injections with botulinum toxin or steroids, CO2 laser or surgery. In cases of lack of treatment response within three months or non-adherence due to side effects, the therapy was changed according to the above described semi-algorithmic approach.14,37

Online Survey on Baseline Data and Treatment Outcomes

The survey was carried out upon individual discharge from the vulvar clinic between January and October 2022, using a customized online questionnaire covering 37 questions on symptoms and treatment outcomes (Appendix 1). All patients from the three subgroups (vulvodynia, chronic genital eczema, lichen sclerosus) received the same questionnaire focused on the symptom pain. When developing our survey, we followed the recommendations of Pukall et al for establishing outcome measures for self-reporting outcomes in vulvodynia trials.38 It is suggested that studies assess the full nature and impact of chronic vulvar pain.39 Thorough history taking (eg past surgeries, mental health, sexual history) should accompany pain assessment (eg location, quality, frequency). In the questionnaire, the common triggering and associated factors (chronic pain disorder, use of hormonal treatment, recurring vaginal infections or cystitis, pelvic floor tensions) as described in the introduction, were evaluated along with questions about patient demographics and general medical history (parity, mental illness, physical or sexual injury, allergies). Additionally, the following information regarding genital pain was collected: site and duration of pain, time of onset, triggering factors, quality, frequency and presence of vaginismus. The treatment outcome was measured by rating therapeutic success on a five-step ordinal scale (distinctly improved, slightly improved, unchanged, slightly worsened, distinctly worsened).

The survey allowed multiple choice answers for therapeutic success, as many patients underwent multiple therapies in series. To minimize the recall bias regarding the sequences of drug or treatment administration, the sequence of interventions of the different treatments was not the subject of the qualitative survey. An online REDCap® project design was chosen for obtaining the patients’ informed consent and conducting the survey.40,41 Data was then extracted from the online REDCap® database and transferred to Excel for further analysis. The data from the survey is based on the experience of the patients and the extracted answers were not double-checked with the internal database.

Statistics

The online survey was conducted by using the REDCap® survey tool. The invitations for the survey were sent by e-mail and followed up by a reminder after six weeks. All data was evaluated after encoding. Patient demographic variables were described as frequencies and percentages for categorical variables, and as means and standard deviations for continuous variables. Inferential statistics for intergroup comparisons were analyzed with the Kruskal Wallis test for categorical variables and ANOVA test for continuous variables. In order to analyze the relative impact of various therapies on therapeutic success (five-step ordinal scale) an ordinal regression was performed. A total of 14 therapies were categorized into 4 groups to reduce the complexity of the model (locally-invasive, topical, non-pharmacological and oral treatments). A cumulative link mixed model was chosen to account for the ordinal nature of the dependent variable and the possibility of multiple observations per patient (random effect). Therapy was included as a fixed effect. No additional covariates were included. The “clmm” function of the R package “ordinal” was used to perform the regression. P-values smaller than 0.05 were defined as statistically significant. All analyses were carried out using the statistical software R version ≥ 3.5.0 (R-Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

In total, 41 patients with vulvodynia, 37 with eczema and 23 with lichen sclerosus responded to the online survey. The average response rate was 30%. The groups were generally comparable regarding age at onset of pain (mean age 28±14.23 years), pain characteristics and comorbidities. As shown in Table 1, there were no statistically significant differences in the vulvodynia, eczema, and lichen groups regarding pain localization, onset of pain and parity. Concerning questions about provocation of pain and vaginismus, a significant difference could be observed in the distribution, which showed a tendency toward increased provoked pain (p = 0.009) and vaginismus (p = 0.042) in the vulvodynia collective.

Table 1.

Pain Characteristics and Comorbidities for Vulvodynia, Eczema and Lichen Sclerosus

| Variables | Vulvodynia | Eczema | Lichen Sclerosus | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 41 | 37 | 23 | |

| Age at onset of pain, mean (±SD) | 24.94 (12.99) | 25.87 (11.41) | 34.64 (17.96) | 0.091 |

| Pain localization, n (%) | 0.870 | |||

| Diffuse | 3 (8.3) | 3 (9.4) | 2 (9.1) | |

| Local | 23 (63.9) | 19 (59.4) | 16 (72.7) | |

| Mixed | 10 (27.8) | 10 (31.2) | 4 (18.2) | |

| Provoked pain, n (%) | 0.009 | |||

| Both | 14 (38.9) | 19 (59.4) | 10 (45.5) | |

| Triggerable | 21 (58.3) | 10 (31.2) | 6 (27.3) | |

| Spontaneous | 1 (2.8) | 3 (9.4) | 6 (27.3) | |

| Secondary onset of pain, n (%) | 18 (51.4) | 21 (67.7) | 15 (75.0) | 0.171 |

| Constant pain, n (%) | 18 (50.0) | 12 (37.5) | 5 (22.7) | 0.116 |

| Vaginismus, n (%) | 0.042 | |||

| Always | 16 (44.4) | 5 (16.1) | 5 (25.0) | |

| Never | 13 (36.1) | 13 (41.9) | 5 (25.0) | |

| Sometimes | 7 (19.4) | 13 (41.9) | 10 (50.0) | |

| Spontaneous birth before, n (%) | 7 (20.0) | 6 (20.0) | 8 (40.0) | 0.193 |

| Symptoms significantly worsened after birth, n (%) | 2 (50.0) | 2 (40.0) | 3 (60.0) | |

| Chronic pain symptoms, n (%) | 9 (25.0) | 9 (28.1) | 9 (40.9) | 0.421 |

| Oral estrogen use, n (%) | 15 (41.7) | 22 (71.0) | 13 (59.1) | 0.052 |

| Fungal infections (>4x/year), n (%) | 6 (16.7) | 11 (34.4) | 7 (31.8) | 0.211 |

| Antifungal therapy (>4x/year), n (%) | 7 (20.6) | 17 (53.1) | 8 (38.1) | 0.023 |

| Cystitis (>3x/year), n (%) | 7 (19.4) | 9 (28.1) | 4 (18.2) | 0.602 |

| Antibiotic use (>2x/year), n (%) | 5 (14.3) | 7 (21.9) | 3 (15.0) | 0.682 |

| Pelvic floor tension, n (%) | 16 (44.4) | 7 (22.6) | 2 (10.5) | 0.019 |

| Insomnia, n (%) | 4 (11.8) | 6 (18.8) | 4 (18.2) | 0.700 |

| Depression/Anxiety disorder, n (%) | 10 (30.3) | 12 (37.5) | 6 (27.3) | 0.701 |

| Physical injury, before onset of pain, n (%) | 2 (5.7) | 5 (15.6) | 2 (9.1) | 0.399 |

| Sexual injury, before onset of pain, n (%) | 8 (22.2) | 10 (31.2) | 4 (18.2) | 0.505 |

| Allergies, n (%) | 18 (50.0) | 20 (62.5) | 6 (27.3) | 0.039 |

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

For pain comorbidities, significant differences regarding pelvic floor tension (p = 0.019) and allergies (p = 0.039) were identified, with a substantially higher frequency of pelvic floor tension reported by vulvodynia patients and higher frequency of allergic conditions in women with vulvodynia and eczema.

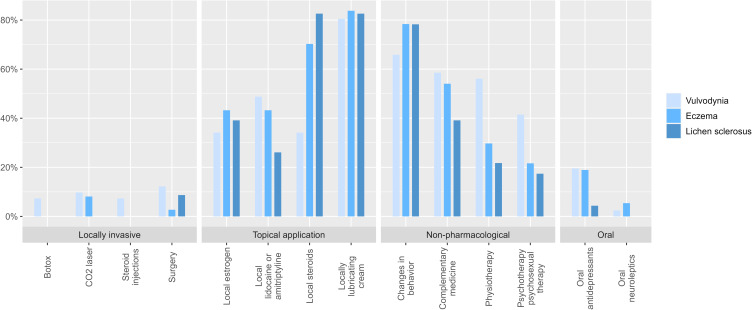

The various treatments are presented groupwise (locally invasive, topical application, non-pharmacological and oral) and revealed a wide range of therapeutic modalities that had been applied in the three vulvar conditions (Figure 1). Topical application and non-pharmacological treatment were most commonly used for all three diagnoses. Of all the topical medications, lubricating cream was most frequently used for vulvodynia patients (41%).

Figure 1.

Distribution of overall therapy modalities with respect to the 2021 European Guidelines assessed groupwise (locally invasive, topical application, non-pharmacological, oral) for Vulvodynia, Eczema and Lichen sclerosus.

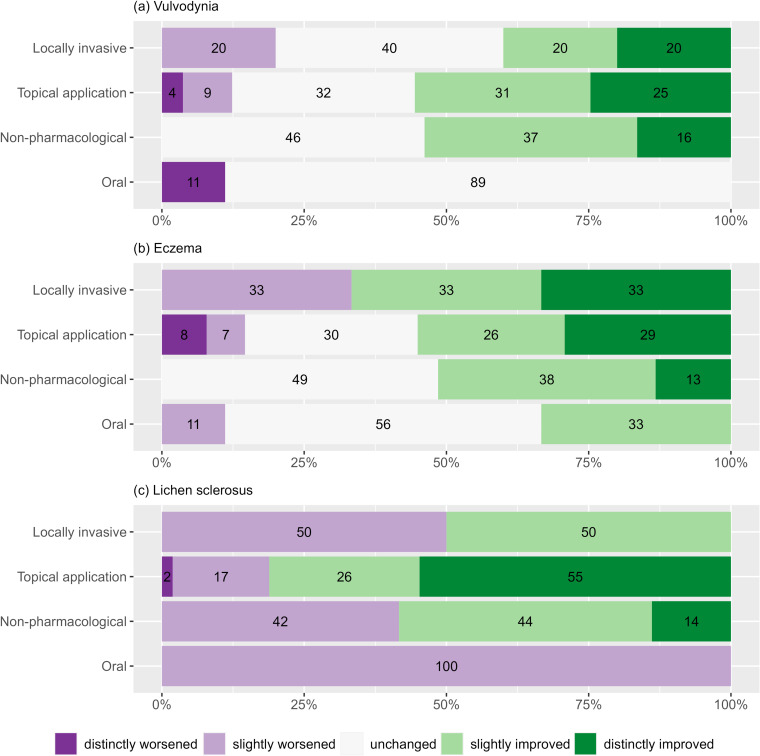

Vulvodynia patients reported similar improvements in symptoms after receiving a non-pharmacological, topical therapy or locally invasive therapy (Figure 2a). No vulvodynia patient reported a worsening under non-pharmacological treatment. After using oral medication, no patient with vulvodynia reported an improvement. Comparable results were observed for patients with eczema (Figure 2b) and lichen sclerosus (Figure 2c). All three patient groups benefited from non-pharmacological treatment (improvement rate vulvodynia 54%; eczema 51%; lichen sclerosus 58%), from topical (55%; 55%; 75%) and from locally invasive (46%; 66%; 50%) treatments.

Figure 2.

Overview of therapeutic success in a five-step ordinal order for Vulvodynia (a), Eczema (b) and Lichen sclerosus (c).

Notes: Numbers in bars are percentages. The percentage total is not always 100 due to rounding.

In the ordinal regression analysis (Table 2), non-pharmacological treatment was defined as the comparison variable. For vulvodynia treatments, no significant difference could be found between the subgroups locally invasive and topical application when compared with non-pharmacological. Oral therapies resulted in a significantly worse outcome for vulvodynia patients (p-value 0.021), but not for genital eczema and lichen sclerosus patients. Topical therapies appear to be helpful in comparison with non-pharmacological therapies (OR vulvodynia 1.04, eczema 1.19), but not significantly, except for cases with lichen sclerosus (OR 7.01). For invasive treatments (Botulinum toxin injections, CO2 laser, steroid injections, surgery) the results varied (OR vulvodynia 0.72, eczema 1.47, lichen sclerosus 1.00).

Table 2.

Ordinal Regression Analysis on Relative Therapeutic Success Using the Cumulative Link Mixed Model; Baseline Value: Non-Pharmacological Therapy; Overall: Pooling All Data from Vulvodynia, Eczema and Lichen Sclerosus

| Variable | OR | Estimate | SE | Z-valuea | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vulvodynia | |||||

| Locally invasive | 0.72 | −0.32 | 0.61 | −0.53 | 0.598 |

| Topical application | 1.04 | 0.04 | 0.30 | 0.14 | 0.891 |

| Oral | 0.19 | −1.65 | 0.72 | −2.30 | 0.021 |

| Eczema | |||||

| Locally invasive | 1.47 | −0.38 | 1.23 | −0.31 | 0.756 |

| Topical application | 1.19 | −0.21 | 1.23 | −0.17 | 0.867 |

| Oral | 0.63 | −0.84 | 1.36 | −0.62 | 0.535 |

| Lichen sclerosus | |||||

| Locally invasive | 1.00 | 0.00 | 1.46 | 0.00 | 1.000 |

| Topical application | 7.01 | 1.95 | 0.50 | 3.93 | 0.001 |

| Oral | 0.08 | −2.51 | 2.46 | −1.02 | 0.308 |

| Overall | |||||

| Locally invasive | 0.89 | −0.11 | 0.50 | −0.22 | 0.823 |

| Topical application | 0.81 | −0.21 | 1.23 | −0.17 | 0.867 |

| Oral | 0.40 | −0.91 | 0.48 | −1.89 | 0.050 |

Note: aWald test.

Abbreviations: OR, Odds ratio; SE, standard error.

While there is overall (for vulvodynia, eczema and lichen sclerosus) no significant difference in the treatment outcome for non-pharmacological compared to locally invasive (p-value 0.82) and topical application treatments (p-value 0.87), the use of oral medication was found to be significantly worse (OR overall 0.40, p-value 0.05).

Discussion

This qualitative study analyzed patients’ subjective evaluations of the treatment success they had experienced with oral, topical, non-pharmacological and/or locally invasive treatments for one of three different vulvar afflictions. Women with vulvodynia reported a significant therapeutic response from non-pharmacological, topical and locally invasive treatment. In contrast, the effect of oral therapies was not positively perceived. Surprisingly, very similar therapeutic experiences were found for patients with chronic eczema and lichen sclerosus. According to the current guidelines, the latter two inflammatory skin diseases should primarily be treated with local steroids and behavioral modifications.13 However, many patients with chronic genital eczema and lichen sclerosus received physiotherapy and some women even psychotherapy, which was also experienced as helpful. A known reciprocal relationship between systemic dermatosis and psychosexual distress may explain why psychotherapy, mindfulness practices, hypnosis and biofeedback can have a beneficial effect on eczema and lichen with its related psychological burden, which ultimately results in improved quality of life.42–44 As genital pain is often caused by multifactorial etiologies, a holistic treatment approach including manual and psychological therapeutic options seems to meet patients’ needs. Multimodal therapeutic approaches are well-established options for patients with provoked vulvodynia.45 As patient satisfaction with these therapeutic options is high and side effects are minimal, our findings support offering non-pharmacological treatments together with topical therapies among first-line therapies for vulvodynia, eczema and lichen sclerosus patients. Indeed, a combination of psychosexual interventions, physiotherapy and pain management is in line with treatment concepts for other chronic pain conditions.46,47

In vulvodynia patients, heightened occurrences of provoked pain, vaginismus, and pelvic floor tension were significantly prevalent compared to patients diagnosed with lichen sclerosus and genital eczema. It is worth noting that the involvement of pelvic floor musculature is well known in the pathophysiological framework of provoked vulvodynia.7 The efficiency of the manual therapeutic approaches strongly depends on the correct indication; vulvodynia in particular requires that patients are carefully questioned about their pain characteristics and comorbidities. In vulvodynia, which is most often associated with muscle tension, physical therapy for muscle relaxation and trigger point resolution is the treatment of choice; for example, a multimodal physiotherapeutic intervention resulted in better treatment outcomes than lidocaine treatment.27

However, well-designed randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are needed to assess how patient experiences translate into objective measures of therapeutic success.19,33 Until now, neither long-term studies nor controlled trials to identify the most successful therapeutic approach have been published.48 According to a review by Bohm-Starke et al, many studies evaluating effects of frequently used treatment options for vulvodynia do not reveal distinct benefits.45 Available RCTs focus on provoked vulvodynia only and do not include other vulvodynia subgroups. The state of evidence for vulvodynia therapy thus remains unclear. According to our data, topical applications and locally invasive therapies also seem to lead to satisfactory amelioration, at least for some women, while oral drug use was reported to show no improvement in any of the investigated vulvar diseases. These results reflect the recommendations of the 2021 European Guidelines, which do not indicate proven benefit for the use of oral medication in vulvodynia.13 In other neuropathic pain conditions the efficacy of oral therapy has been reported; however, with rather moderate efficacy and some placebo response.49 Regarding neuropathic conditions, it must be emphasized that both heterogeneous diagnostic criteria and poor phenotypic profiling are used, which hampers the comparability of treatment and most probably study outcomes. The situation in vulvar disease is somewhat similar.

In our study, no significant differences in pain characteristics were found among the three groups. That result contrasts with our clinical experience, which reveals patients with vulvodynia suffering from pain more often than women with other vulvar diseases. These findings support the common observation that patients’ experiences are not always in line with physicians’ perceptions, even when physicians are highly experienced, so that it is mandatory to carefully evaluate subjective patient experience to identify the most effective therapeutic approaches.

In vulvodynia, lack of a visible skin alteration may hamper evaluation of treatment success, whereas women with eczema and lichen can control treatment response by visually self-checking vulvar lesions in addition to subjectively experienced symptoms. Such differences likely make monitoring of therapeutic success more challenging. Again, a careful investigation of the pain intensity, location and trigger situation, which is re-evaluated at defined time-points following initiation of treatment will help to design treatment decisions. As currently no patient-reported outcome measures for genital pain or pelvic floor disorders are available, vulvar clinics need to develop their own standardized pain-specific instruments for evaluation.50 A few tools to investigate women’s genital pain do exist, such as the Vulvar Pain Assessment Questionnaire and the Vulvar Quality of Life Index, but they do not directly assess patients’ comorbidities and patients’ reported outcomes.39,51

The widespread use of various treatment approaches (Figure 2) among patients with genital pain disorders might be the consequence of uncertainty in distinguishing the diseases from each other, of limited effect from the initially chosen therapy, of insufficient treatment success from a single treatment approach, of shortcomings in patient adherence, or of a combination of these and further factors. In our experience, many patients with genital pain are immediately diagnosed with vulvodynia without an initial detailed examination or histologic workup. Raising awareness in this field is crucial to not missing underlying diseases that may have more effective treatments.

As in other survey-based studies, several weaknesses need to be acknowledged. As data collection was carried out from the patient’s perspective, the therapy received was not objectively recorded and no conclusions on the sequence of therapies could be drawn. A memory bias is also possible, as the experiences reported were more remote for some patients than for others. Moreover, the study cohort was rather small and the response rate (30%) was low. It was difficult to find a higher number of age-matched patients with lichen sclerosus, because this disease tends to be diagnosed later in life than vulvodynia.

Furthermore, as the patients often received multiple therapy modalities in combination, an approach that is recommended by guidelines, our data does not allow us to make an absolute statement about the success of a single therapy. Simultaneous therapies such as topical therapy or oral therapy with physiotherapy might yield an improvement in vulvar condition, though this makes it impossible to distinguish between single therapy effects. To ensure the success of single therapies, further prospective randomized studies are needed. The design of our study represents a real-life setting with an overlap of different treatments. Regarding therapy failure, we have no data on why patients did not regard a treatment as helpful, whether due to lack of response, side effects or motivational problems as in psycho- or physiotherapy. So far, there are unfortunately no standardized patient-reported outcome measures for genital pain or pelvic floor disorders, that are a suitable instrument for investigating treatment outcome.50

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to compare the subjectively experienced treatment success of the current spectrum of guideline-recommended and other therapies in women with vulvodynia and other genital pain conditions. A further strength of our study is that it covers most of the guideline-recommended therapies for vulvodynia. We therefore consider our findings to be clinically relevant and helpful in improving strategies for the care of women with chronic and highly distressing vulvar diseases.

The treatment of genital pain remains challenging, however, due to its multifactorial etiologies. There is a clear need for more research in this field, particularly for research evaluating multimodal treatment approaches.

Conclusion

In the patients’ perception, topical, invasive and non-pharmacological treatments, but not oral medication, help to relieve genital pain in vulvodynia, vulvar eczema, and lichen sclerosus. In persistent pain conditions, the escalating therapy approach remains contested and new options are highly sought after. Since non-pharmacological therapies were experienced as beneficial therapeutic options, they should be considered as part of a holistic treatment concept and be more systematically investigated to further clarify their potential for symptom alleviation in vulvar diseases.

Finally, the identification and classification of patients’ reported outcomes would assist future core outcome consensus studies and therefore should be included in patient counselling.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support and statistical revision of the data by Susanne Forst. For English language editing, we are grateful to Dr Heather Murray.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Bornstein J, Goldstein AT, Stockdale CK, et al. 2015 ISSVD, ISSWSH and IPPS consensus terminology and classification of persistent vulvar pain and vulvodynia. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(4):745–751. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pukall CF, Goldstein AT, Bergeron S, et al. Vulvodynia: definition, prevalence, impact, and pathophysiological factors. J Sex Med. 2016;13(3):291–304. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2015.12.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reed BD, Harlow SD, Sen A, et al. Prevalence and demographic characteristics of vulvodynia in a population-based sample. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(2):170. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.08.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bergeron S, Reed BD, Wesselmann U, Bohm-Starke N. Vulvodynia. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020;6(1):36. doi: 10.1038/s41572-020-0164-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoffman D. Understanding multisymptom presentations in chronic pelvic pain: the inter-relationships between the viscera and myofascial pelvic floor dysfunction. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2011;15(5):343–346. doi: 10.1007/s11916-011-0215-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoffman D. Central and peripheral pain generators in women with chronic pelvic pain: patient centered assessment and treatment. Curr Rheumatol Rev. 2015;11(2):146–166. doi: 10.2174/1573397111666150619094524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morin M, Bergeron S, Khalife S, Mayrand M-H, Binik YM. Morphometry of the pelvic floor muscles in women with and without provoked vestibulodynia using 4D ultrasound. J Sexual Med. 2014;11(3):776–785. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morin M, Binik YM, Bourbonnais D, Khalifé S, Ouellet S, Bergeron S. Heightened pelvic floor muscle tone and altered contractility in women with provoked vestibulodynia. J Sex Med. 2017;14(4):592–600. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2017.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bergeron S, Likes WM, Steben M. Psychosexual aspects of vulvovaginal pain. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2014;28(7):991–999. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2014.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baldo M, Bailey A, Bhogal B, Groves RW, Ogg G, Wojnarowska F. T cells reactive with the NC16A domain of BP180 are present in vulval lichen sclerosus and lichen planus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24(2):186–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03375.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tominaga M, Takamori K. Peripheral itch sensitization in atopic dermatitis. Allergol Int. 2022;71(3):265–277. doi: 10.1016/j.alit.2022.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee A, Fischer G. Diagnosis and Treatment of Vulvar Lichen Sclerosus: an update for dermatologists. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19(5):695–706. doi: 10.1007/s40257-018-0364-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van der Meijden WI, Boffa MJ, Ter Harmsel B, et al. 2021 European guideline for the management of vulval conditions. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36(7):952–972. doi: 10.1111/jdv.18102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haefner HK, Aldrich NZ, Dalton VK, et al. The impact of vulvar lichen sclerosus on sexual dysfunction. J Womens Health. 2014;23(9):765–770. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2014.4805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sampogna F, Abeni D, Gieler U, et al. Impairment of sexual life in 3485 dermatological outpatients from a multicentre study in 13 European countries. Acta Derm Venereol. 2017;97(4):478–482. doi: 10.2340/00015555-2561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sampogna F, Abeni D, Gieler U, et al. Diagnosis and management of vulvar skin disorders: ACOG practice bulletin, number 224. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;136:1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kirtschig G, Becker K, Günthert A, et al. Evidence-based (S3) Guideline on (anogenital) Lichen sclerosus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29(10):43. doi: 10.1111/jdv.13136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pagano T, Conforti A, Buonfantino C, et al. Effect of rescue fractional microablative CO2 laser on symptoms and sexual dysfunction in women affected by vulvar lichen sclerosus resistant to long-term use of topic corticosteroid: a prospective longitudinal study. Menopause. 2020;27(4):418–422. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000001482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosen NO, Dawson SJ, Brooks M, Kellogg-Spadt S. Treatment of vulvodynia: pharmacological and non-pharmacological approaches. Drugs. 2019;79(5):483–493. doi: 10.1007/s40265-019-01085-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Foster DC, Kotok MB, Huang LS, et al. Oral desipramine and topical lidocaine for vulvodynia: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(3):583–593. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181e9e0ab [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haraldson P, Mühlrad H, Heddini U, Nilsson K, Bohm-Starke N. Botulinum toxin A as a treatment for provoked vestibulodynia: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;136(3):524–532. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pagano R, Wong S. Use of amitriptyline cream in the management of entry dyspareunia due to provoked vestibulodynia. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2012;16(4):394–397. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0b013e3182449bd6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Diomande I, Gabriel N, Kashiwagi M, et al. Subcutaneous botulinum toxin type A injections for provoked vestibulodynia: a randomized placebo-controlled trial and exploratory subanalysis. Arch Gynecol Obstetrics. 2019;299(4):993–1000. doi: 10.1007/s00404-019-05043-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bachmann GA, Brown CS, Phillips NA, et al. Effect of gabapentin on sexual function in vulvodynia: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220(1):89. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.10.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Friedman M, Ben-David B, Siegler E. Amitriptyline versus placebo for treatment of vulvodynia: a prospective study. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 1999;3(1):36. doi: 10.1097/00128360-199901000-00013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morin M, Carroll MS, Bergeron S. Systematic Review of the Effectiveness of Physical Therapy Modalities in Women With Provoked Vestibulodynia. Sex Med Rev. 2017;5(3):295–322. doi: 10.1016/j.sxmr.2017.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morin M, Dumoulin C, Bergeron S, et al. Multimodal physical therapy versus topical lidocaine for provoked vestibulodynia: a multicenter, randomized trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;224(2):189. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.08.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reissing ED, Brown C, Lord MJ, Binik YM, Khalifé S. Pelvic floor muscle functioning in women with vulvar vestibulitis syndrome. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2005;26(2):107–113. doi: 10.1080/01443610400023106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bergeron S, Khalifé S, Glazer HI, Binik YM. Surgical and behavioral treatments for vestibulodynia: two-and-one-half year follow-up and predictors of outcome. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(1):159–166. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000295864.76032.a7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Masheb RM, Kerns RD, Lozano C, Minkin MJ, Richman S. A randomized clinical trial for women with vulvodynia: cognitive-behavioral therapy vs. supportive psychotherapy. Pain. 2009;141(1):31–40. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.09.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.King M, Mitchell L, Belkin Z, Goldstein A. 036 vulvar vestibulectomy for neuroproliferative associated vestibulodynia: a retrospective case-control study. J Sexual Med. 2017;14(Supplement_5):363. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2017.04.040 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tommola P, Unkila-Kallio L, Paavonen J. Surgical treatment of vulvar vestibulitis: a review. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2010;89(11):1385–1395. doi: 10.3109/00016349.2010.512071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sorensen J, Bautista KE, Lamvu G, Feranec J. Evaluation and treatment of female sexual pain: a clinical review. Cureus. 2018;10:2379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stenson AL. Vulvodynia: diagnosis and management. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2017;44(3):493–508. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2017.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bailo L, Guiddi P, Vergani L, Marton G, Pravettoni G. The patient perspective: investigating patient empowerment enablers and barriers within the oncological care process. Ecancermedicalscience. 2019;13:912. doi: 10.3332/ecancer.2019.912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Náfrádi L, Nakamoto K, Schulz PJ, Asnani MR. Is patient empowerment the key to promote adherence? A systematic review of the relationship between self-efficacy, health locus of control and medication adherence. PLoS One. 2017;12(10):186. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0186458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goldstein AT, Pukall CF, Brown C, Bergeron S, Stein A, Kellogg-Spadt S. Vulvodynia: assessment and Treatment. J Sex Med. 2016;13(4):572–590. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.01.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pukall CF, Bergeron S, Brown C, Bachmann G, Wesselmann U, Group VCR. Recommendations for Self-Report Outcome Measures in Vulvodynia Clinical Trials. Clin J Pain. 2017;33(8):756–765. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dargie E, Holden RR, Pukall CF. The Vulvar Pain Assessment Questionnaire inventory. Pain. 2016;157(12):2672–2686. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95:103. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wollenberg A, Barbarot S, Bieber T, et al. Consensus-based European guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children: part II. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32(6):850–878. doi: 10.1111/jdv.14888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oska C, Nakamura M. Alternative Psychotherapeutic Approaches to the Treatment of Eczema. Clin Cosmet Invest Dermatol. 2022;15:2721–2735. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S393290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shenefelt PD. Mindfulness-based cognitive hypnotherapy and skin disorders. Am J Clin Hypn. 2018;61(1):34–44. doi: 10.1080/00029157.2017.1419457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bohm-Starke N, Ramsay KW, Lytsy P, et al. Treatment of provoked vulvodynia: a systematic review. J Sex Med. 2022;19(5):789–808. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2022.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guzmán J, Esmail R, Karjalainen K, Malmivaara A, Irvin E, Bombardier C. Multidisciplinary rehabilitation for chronic low back pain: systematic review. BMJ. 2001;322(7301):1511–1516. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7301.1511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Skelly AC, Chou R, Dettori JR, et al. AHRQ comparative effectiveness reviews. In: Noninvasive Nonpharmacological Treatment for Chronic Pain: A Systematic Review Update. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Guidozzi F, Guidozzi D. Vulvodynia - an evolving disease. Climacteric. 2022;25(2):141–146. doi: 10.1080/13697137.2021.1956454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Finnerup NB, Attal N, Haroutounian S, et al. Pharmacotherapy for neuropathic pain in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14(2):162–173. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70251-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ralphsmith M, Ahern S, Dean J, Ruseckaite R. Patient-reported outcome measures for pain in women with pelvic floor disorders: a systematic review. Int Urogynecol J. 2022;33(9):2325–2334. doi: 10.1007/s00192-022-05126-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Saunderson RB, Harris V, Yeh R, Mallitt KA, Fischer G. Vulvar quality of life index (VQLI) - A simple tool to measure quality of life in patients with vulvar disease. Australas J Dermatol. 2020;61(2):152–157. doi: 10.1111/ajd.13235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]