Abstract

Introduction.

Men with advanced prostate cancer (APC) undergoing androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) often experience distressing sexual side effects. Sexual bother is an important component of adjustment. Factors associated with increased bother are not well understood.

Aims.

This study sought to describe sexual dysfunction and bother in APC patients undergoing ADT, identify socio-demographic and health/disease-related characteristics related to sexual bother, and evaluate associations between sexual bother and psychosocial well-being and quality of life (QOL).

Methods.

Baseline data of a larger psychosocial intervention study was used. Pearson’s correlation and independent samples t-test tested bivariate relations. Multivariate regression analysis evaluated relations between sexual bother and psychosocial and QOL outcomes.

Main Outcome Measures.

The Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite sexual function and bother subscales, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy—General, and Dyadic Adjustment Scale were the main outcome measures.

Results.

Participants (N = 80) were 70 years old (standard deviation [SD] = 9.6) and reported 18.7 months (SD = 17.3) of ADT. Sexual dysfunction (mean = 10.1; SD = 18.0) was highly prevalent. Greater sexual bother (lower scores) was related to younger age (β = 0.25, P = 0.03) and fewer months of ADT (β = 0.22, P = 0.05). Controlling for age, months of ADT, current and precancer sexual function, sexual bother correlated with more depressive symptoms (β = −0.24, P = 0.06) and lower QOL (β = 0.25, P = 0.05). Contrary to hypotheses, greater sexual bother was related to greater dyadic satisfaction (β = −0.35, P = 0.03) and cohesion (β = −0.42, P = 0.01).

Conclusions.

The majority of APC patients undergoing ADT will experience sexual dysfunction, but there is variability in their degree of sexual bother. Psychosocial aspects of sexual functioning should be considered when evaluating men’s adjustment to ADT effects. Assessment of sexual bother may help identify men at risk for more general distress and lowered QOL. Psychosocial interventions targeting sexual bother may complement medical treatments for sexual dysfunction and be clinically relevant, particularly for younger men and those first starting ADT.

Keywords: Prostate Cancer, Androgen Deprivation, Androgen Ablation, Hormone Therapy, Sexual Function, Sexual Dysfunction, Sexual Bother, Erectile Dysfunction, Depressive Symptoms, Relationship Functioning, Quality of Life

Introduction

The use of androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) is an established standard of care for prostate cancer and is increasingly used to treat nonmetastatic and recurrent disease (biochemical relapse), and in a multimodal treatment approach [1–4]. Men diagnosed with advanced prostate cancer (APC) typically receive ADT as a first line of treatment [5,6]. In this context, ADT is administered to delay disease progression with extended survival time and quality of life (QOL) considerations as primary end points [2]. Although effective for delaying disease progression, ADT often causes significant side effects that can negatively impact QOL [7,8]. Sexual side effects have been shown to be particularly distressing and may further impact psychosocial well-being and QOL, above and beyond other disease- and treatment-related effects [6,7].

The importance of sexual functioning is often not fully appreciated within the context of advanced cancer, and the psychosexual needs of patients may be overlooked, particularly among older adults [9–11]. Interest and desire to engage in sexual activity do not necessarily lessen with age or declining physical health [12], even in the face of medical illness and disability [13]. Although men with APC undergoing ADT may face a number of challenges (e.g., role changes, uncertainty/fear of disease progression), sexuality is an important aspect of health and well-being for men and their partners [14–16].

Despite literature highlighting the importance of sexuality in older adults, it is unclear whether men with APC are bothered by sexual side effects. ADT-related sexual changes may include erectile dysfunction, loss of libido, altered orgasm experience, genital atrophy/shrinkage, and bodily feminization [17–19]. For men who experienced impairments from primary treatment (radical prostatectomy or radiation therapy), ADT typically worsens symptoms and exacerbates sexual difficulties [20]. Despite these significant physiologic changes, there may be variability in the degree to which men are bothered by ADT sexual side effects [21]. Although most research has been in localized prostate cancer, findings suggest sexual bother may be largely independent of sexual function and uniquely related to QOL outcomes [21–24]. Changes in sexual function occur within the context of other psychosocial and situational factors related to sexuality (e.g., expectations for sexual performance, perceptions of diminished masculinity, having an available partner, and partners’ sexual function and interest [18,25,26]). As such, men with the same level of impairment may be more or less bothered or distressed. Given that assessment of sexual function will likely lead to floor effects in this patient population, sexual bother may be a more meaningful and robust indicator of how sexual side effects affect well-being.

For men who are significantly bothered by sexual changes as a result of treatment, distress may generalize to other domains of psychosocial function and QOL. Among APC patients undergoing ADT, lowered sexual function (e.g., erectile dysfunction, loss of libido) has been related to increased distress, worse QOL, and disruption to couples’ relationship functioning [6,20]. We sought to describe sexual dysfunction (i.e., symptom severity) and sexual bother (i.e., distress related to symptoms), identify socio-demographic and health/disease-related characteristics related to sexual bother, and evaluate whether greater sexual bother is independently related to greater depressive symptoms, lowered QOL, and worse relationship functioning.

Methods

Participants were part of a larger National Cancer Institute-funded randomized controlled trial of a 10-week, group-based psychosocial intervention for APC patients designed to improve coping and QOL [27]. Recruitment was done through referrals from urology clinics, community presentations, and through the Florida Cancer Data System. Eligibility criteria included stage III or IV APC diagnosis and ADT side effects experienced in the past 12 months. All participants were on luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone agonists and men were eligible to participate if they were on intermittent or continuous ADT; if they were receiving concomitant external beam radiation therapy (EBRT); and if they had new advanced disease or a recurrence with advanced disease. Men were also required to be age 50 years or older, fluent in English, have at least a ninth grade-level education, and with no history of severe psychiatric pathology in the past 3 months or prior cancer history other than prostate cancer. A score of at least 26 on the Mini Mental State Examination was used to rule out cognitive impairment and ensure understanding of study materials [28]. The Structured Clinical Diagnostic Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition was used to exclude individuals with a history of or current psychosis, current substance use/dependence disorders, organic mental disorder, and active suicidal ideation or panic disorder [29]. Participants signed an informed consent and completed a battery of measures to assess factors related to psychosocial well-being and physical health. Financial compensation ($50) was given to participants for their time and effort. All study materials and procedures were approved by the University of Miami Institutional Review Board. This study utilized data collected at the baseline visit, prior to the introduction of the psychosocial intervention.

Main Outcome Measures

Standard questionnaires and the Charlson Comorbidity Index [30] were used to collect socio-demographic and health/disease-related information (age, ethnicity, education, marital/partner status [yes/no], medical comorbidities, months since diagnosis, and months of ADT).

Sexual Side Effects

The Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite (EPIC) assessed sexual function (symptom severity; nine items) and sexual bother (the degree to which symptoms were problematic; four items) in the past month [31]. Sexual function subscales (current and before cancer) include items that refer to desire (libido), orgasm, erectile function (quality and frequency), and frequency of sexual intercourse and activity. The sexual function scale items were adapted to assess retrospective report of baseline sexual functioning before cancer diagnosis (nine items). Response options vary across items but are all answered on a four-point Likert scale. Sexual bother items ask participants to rate the degree to which they consider sexual side effects to be a problem. These items also have a four-point response scale ranging from “No problem” to “Big problem.” Higher scores indicate better outcomes (better functioning; less bother). All subscales demonstrated good internal reliability in the current study (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.93–0.94).

Psychological Well-Being

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; 20 items) measured depressive symptoms as a marker of psychological well-being [32]. Items refer to how respondents have felt in the past week and responses are on a four-point Likert scale (“Rarely or none of the time” to “Most or all of the time”). Higher scores indicate more depressive symptoms. Internal reliability was adequate in the current study (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.67).

Relationship Well-Being

The Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS; 32 items) assessed relationship well-being in the subset of participants who were married or partnered (n = 54) [33]. The DAS is made up of four subscales including dyadic consensus (13 items; degree to which a couple agrees on matters of importance to the relationship), dyadic satisfaction (10 items; degree of satisfaction with the relationship), dyadic cohesion (5 items; degree of closeness and shared activities experienced by the couple), and affectional expression (4 items; degree of demonstrations of affection within the couple). Items refer to general perceptions of relationship functioning and are not limited to a specific timeframe. Higher scores indicate better relationship functioning. Internal reliability was established for the dyadic consensus, satisfaction, and cohesion subscales (Cronbach’s alphas = 0.77–0.86); the affectional expression subscale demonstrated inadequate reliability and was excluded (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.34).

QOL

General QOL was measured using the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy—General Module (FACT-G; 27 items assessing multiple domains) [34]. Items refer to the past week and are answered on a five-point Likert scale (“Not at all” to “Very much”). Higher scores indicate better QOL. A single item of current sexual satisfaction was removed when assessing relations between sexual bother and QOL to avoid multi-collinearity; the total score included the remaining 26 items (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.61).

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics were evaluated for all study variables. Unadjusted associations between sexual bother and all other variables were tested using Pearson’s correlation and independent samples t-test. Multivariate regression models were specified to test relations between sexual bother and depressive symptoms and QOL, controlling for age, months of ADT, precancer sexual function, and current sexual function (chosen a priori). Because of the smaller sample size of married/partnered participants who completed the DAS measure, the relationship function models only included months of ADT, current sexual function, and sexual bother as independent variables. Those were chosen as the most relevant variables to include based on the literature and conceptual relations among study variables as well as our interest in evaluating the importance of sexual bother in the context of ADT-related effects on sexual function [21,24,35]. To test whether sexual bother explained a significant amount of unique variance in each outcome, covariates and sexual function were included in step 1 and sexual bother was included in step 2. Residual scatter plots were used to confirm that assumptions of normality, linearity, and homoscedasticity within regression analyses were met for each model that was tested. Models were evaluated for statistical significance at P < 0.05. Post hoc analyses were conducted to characterize men who reported “higher” vs. “lower” degrees of sexual bother based on a median split, and independent samples t-tests were used to evaluate group differences.

Results

Descriptive data are presented in Table 1. Participants (N = 80) were an average of 70 years old (standard deviation [SD] = 9.6), well-educated, most were married/partnered (68%; n = 54), and the sample was ethnically diverse (non-Hispanic White, 65%; Hispanic, 13%; Black, 21%; other, 1%). Men were approximately 3 years post-diagnosis of prostate cancer (SD = 2.7) and had undergone 1.6 (SD = 1.4) years of ADT at the time of assessment.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the total sample and bivariate relations with sexual bother

| Variable | Total sample (N = 80) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | Range | Bivariate relation with sexual bother† Pearson’s r | |

|

| |||

| Age (years) | 69.7 (9.6) | 49–92 | 0.25 * |

| Education (years) | 15.3 (3.0) | 9–20 | 0.12 |

| Medical comorbidities (#) | 2.3 (2.7) | 0–12 | −0.20 ± |

| Time since diagnosis (months) | 37.6 (34.3) | 1–164 | 0.21 ± |

| Months of ADT | 18.7 (17.3) | 0–85 | 0.22 * |

| Sexual function—before cancer | 66.6 (25.7) | 0–100 | −0.19 |

| Sexual function (past month) | 10.1 (18.0) | 0–72 | 0.13 |

| Sexual bother (past month) | 44.5 (40.2) | 0–100 | — |

| Depressive symptoms | 9.3 (9.5) | 0–47 | −0.30 ** |

| Relationship well-being§ | |||

| Dyadic consensus | 50.7 (7.5) | 33–63 | −0.11 |

| Dyadic satisfaction | 39.9 (6.2) | 21–49 | −0.38 * |

| Dyadic cohesion | 16.5 (4.1) | 6–24 | −0.35 * |

| General QOL | 82.7 (14.4) | 46–107 | 0.29 ** |

|

| |||

| % | Sexual bother M (SD) | Independent samples t-test, P value | |

|

| |||

| Ethnicity | 0.09 | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | 65 | 50.2 (39.3) | |

| Minority‡ | 35 | 33.7 (40.9) | |

| Relationship status§ | 0.62 | ||

| Married/partnered | 68 | 70.6 (21.9) | |

| Single | 32 | 57.6 (31.2) | |

P < 0.10

P < 0.05

P < 0.01

Bivariate correlations and independent samples t-tests of the EPIC sexual bother subscale with continuous and categorical variables, respectively. Greater sexual bother is indicated by lower scores on the EPIC sexual bother subscale. Relations significant at the trend level (P < 0.10) are bold to aid interpretation

Minority includes black/African American (18%), Hispanic (12%), Caribbean Islander (2%), and Asian (1%); groups were combined because of small sample sizes

Analyses limited to married/partnered men (n = 54)

ADT = androgen deprivation therapy; EPIC = Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite; M = mean; QOL = quality of life; SD = standard deviation

Participants reported greater sexual dysfunction (mean [M] = 10.1, SD = 18.0) and greater sexual bother (M = 44.5, SD = 40.2) than reported by age-matched controls [36]. As expected, men reported deteriorating levels of sexual function compared with their retrospective reports of functioning prior to cancer (EPIC sexual function—before cancer and current sexual function subscales, mean difference = 5.6). Only 22% of participants reported any sexual activity in the past 4 weeks, although 87% were sexually active before cancer (58% indicated they were sexually active once to several times per week; EPIC items). The sexual function subscales included an assessment of sexual desire in which 67% of participants rated their current level of sexual desire as poor or very poor to none, compared with only 9% who rated their precancer level of desire in the same way.

Bivariate analysis (Table 1) indicated that greater sexual bother (lower scores) was associated with younger age (r = 0.25, P = 0.03) and fewer months of ADT (r = 0.22, P = 0.05). Greater sexual bother also was associated with more medical comorbidities (r = −0.20, P = 0.09), shorter time since diagnosis (r = 0.21, P = 0.07), higher levels of precancer sexual function (r = −0.19, P = 0.09), and ethnic minority status (non-Hispanic White, M = 50.2, SD = 39.3; minority, M = 33.7, SD = 40.9; t[77] = 1.74, P = 0.09), although these associations did not reach statistical significance. Sexual bother was not related to current sexual function (r = 0.13, P = 0.25), including libido (single item on the EPIC sexual function subscale; r = 0.05, P = 0.69).

Multivariate regression models were specified to evaluate whether sexual bother was related to psychosocial and QOL outcomes, controlling for a priori determined covariates. Four regression models were run with depressive symptoms, general QOL, and dyadic cohesion and satisfaction as dependent variables (Table 2). Dyadic consensus was not related to sexual bother in bivariate analysis, so further analyses were not done. In the depressive symptoms model, greater sexual bother was related to greater depressive symptoms at the trend level (β = −0.24, P = 0.06) and explained 5% of unique variance in depressive symptoms, above and beyond covariates (F[5,69] = 2.65, P = 0.03; R2 = 0.17). In the general QOL model, greater sexual bother was related to lower QOL (β = 0.25, P = 0.05), explaining 5% of the variance (F[5,70] = 2.57, P = 0.03; R2 = 0.16). Finally, in separate models, greater sexual bother was related to higher levels of dyadic cohesion (β = −0.42, P = 0.01; F[3,36] = 3.10, P = 0.04; R2 = 0.21) and higher levels of dyadic satisfaction (β = −0.35, P = 0.03; F[3,36] = 03.17, P = 0.04; R2 = 0.21). Sexual bother explained 16% and 12% of the variance in dyadic cohesion and satisfaction, respectively. None of the other covariates were independently associated with depressive symptoms, QOL, or dyadic cohesion or satisfaction.

Table 2.

Hierarchical regression models evaluating relations between sexual bother and depressive symptoms, general QOL, and relationship function†

| SteFpactor | R 2 | R2Δ | β | t | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Depressive symptoms (CES-D) | |||||

| 1 Age | 0.12 | — | −0.18 | −1.36 | 0.18 |

| Months of ADT | −0.07 | −0.58 | 0.57 | ||

| Sexual function—before cancer | −0.17 | −1.37 | 0.18 | ||

| Sexual function (past month) | −0.19 | −1.46 | 0.15 | ||

| 2 Sexual bother (past month) | 0.17 | 0.05 | −0.25 | −1.93 | 0.06 |

| Quality of life (FACT-G) | |||||

| 1 Age | 0.11 | — | 0.12 | 0.96 | 0.34 |

| Months of ADT | 0.11 | 0.90 | 0.37 | ||

| Sexual function—before cancer | 0.19 | 1.54 | 0.13 | ||

| Sexual function (past month) | 0.13 | 0.98 | 0.33 | ||

| 2 Sexual bother (past month) | 0.16 | 0.05 | 0.25 | 1.99 | 0.05 |

| Dyadic cohesion (DAS subscale)‡ | |||||

| 1 Months of ADT | 0.04 | — | 0.28 | 1.82 | 0.08 |

| Sexual function (past month) | −0.06 | −0.37 | 0.71 | ||

| 2 Sexual bother (past month) | 0.21 | 0.16 | −0.42 | −2.70 | 0.01 |

| Dyadic satisfaction (DAS subscale)‡ | |||||

| 1 Months of ADT | 0.09 | — | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.97 |

| Sexual function (past month) | −0.26 | −1.73 | 0.09 | ||

| 2 Sexual bother (past month) | 0.21 | 0.12 | −0.35 | −2.29 | 0.03 |

Sexual bother was measured using the EPIC sexual bother subscale; lower scores indicate greater sexual bother

Relationship function models were limited to participants who reported to be married or in an equivalent relationship (n = 54). Because of the smaller subgroup sample size, covariates were limited to months of ADT and current sexual function, which were chosen based on conceptual relations with other variables in the model and to answer research questions

ADT = androgen deprivation therapy; CES-D = Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; DAS = Dyadic Adjustment Scale; EPIC = Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite; FACT-G = Assessment of Cancer Therapy—General Module; QOL = quality of life

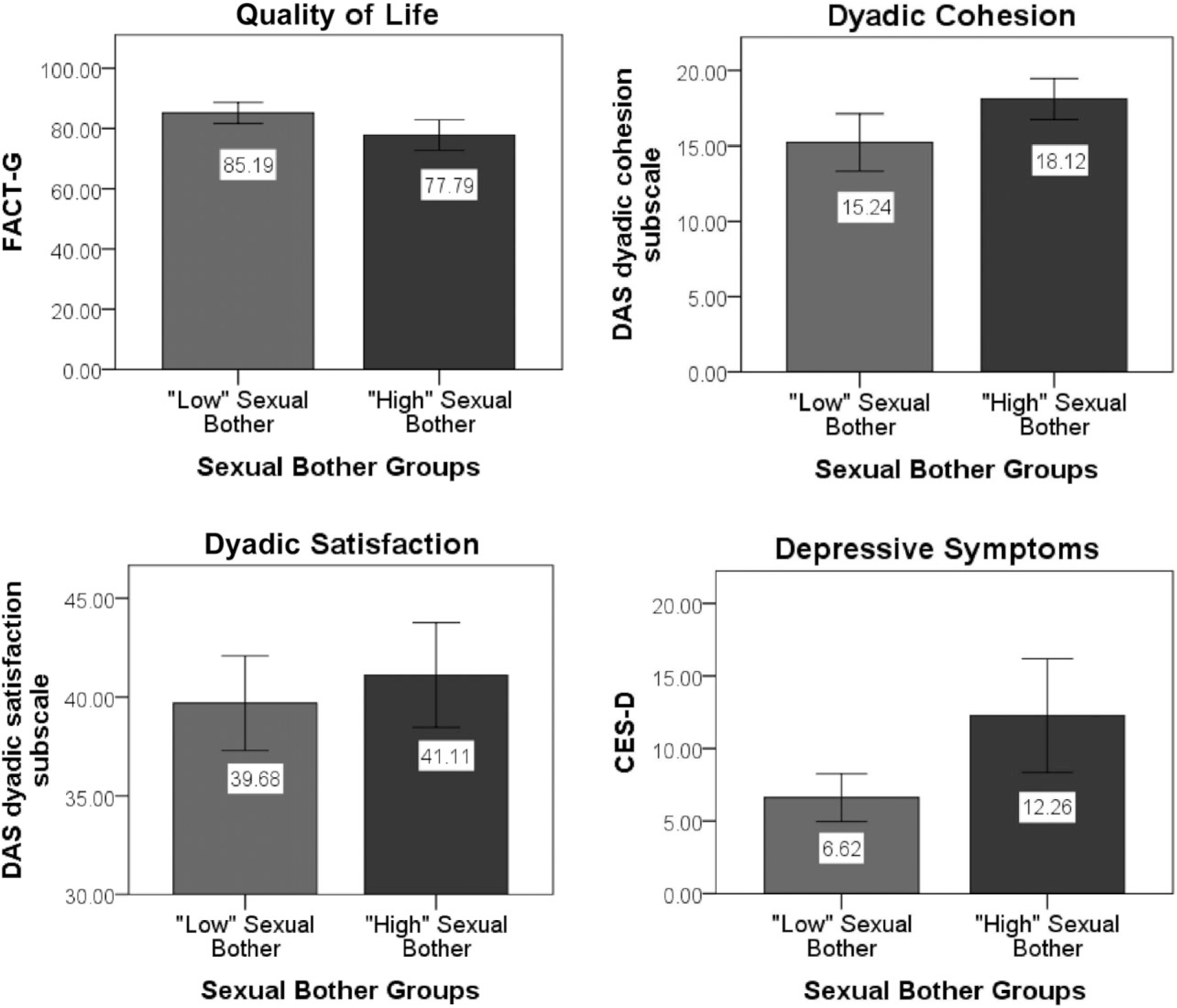

For clinical relevance, post hoc analyses were conducted to characterize men who reported “higher” vs. “lower” degrees of sexual bother (Figure 1). The high sexual bother group reported levels of depressive symptoms (M = 12.26, SD = 11.92) that were above reported general population samples, whereas the low sexual bother group (M = 6.62, SD = 5.07) reported levels below general population means [32,37]. Overall, 18% of participants reported levels of depressive symptoms that were equal to or above the CES-D clinical cutoff score of 16, which is indicative of “significant” or “mild” depressive symptomatology [38]. Men who reported CES-D scores ≥16 reported significantly higher levels of sexual bother than men whose scores were below the cutoff (t[75] = 3.04, P = 0.003) and were more likely to be classified into the high sexual bother group (χ2 = 9.05, P = 0.003). Levels of general QOL between men classified into the two subgroups also suggested a clinically meaningful difference (FACT-G score differences >5 points) [39]. Consistent with prior results, compared with men classified into the “lower” sexual bother group, men classified into the “higher” sexual bother group reported significantly greater depressive symptoms and lower levels of QOL as well as better relationship functioning with respect to dyadic satisfaction and cohesion (Ps < 0.05).

Figure 1.

Independent-samples t-tests of group differences between men classified into “low” vs. “high” sexual bother groups.

Men classified into the “higher” sexual bother group reported significantly greater depressive symptoms and lower levels of quality of life as well as better dyadic satisfaction and cohesion compared with men classified into the “lower” sexual bother group (all Ps < 0.05). Sexual bother groups were defined based on a median split of the EPIC sexual bother subscale. Quality of life was measured using the Functional Assessment of Cancer—General (FACT-G); depressive symptoms were measured using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D); and relationship functioning was measured using the Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS) dyadic satisfaction and cohesion subscales.

Discussion

In the current study, 66% of men on ADT indicated greater sexual bother than that reported for age-matched controls [36]. Fifty-three percent described their erectile function specifically as a moderate or big problem and 40% described libido problems in the same way. Moreover, sexual bother was not related to the degree of perceived sexual dysfunction. These findings support prior suggestions that the practice of equating sexual health and satisfaction with erectile function may be overly simplistic [19]. Clinical assessments should include both function and bother in order to adequately capture how men adjust to treatment-related sexual changes.

Sexual bother was worse among younger men and those with better sexual function prior to cancer. Sexual bother was also worse among those in the first year and a half of initiating ADT. With time, some men may adjust or resign themselves to sexual changes. Navon and Morag [40] identified specific cognitive strategies men used to cope with impotence and loss of libido, including efforts to reconstruct their identity as asexual, relegate sex to a former stage of life, and normalize their experience as common among older men. ADT-related risks of other health problems, fatigue, and changes in mood may also start to take precedence over distress related to sexual changes [7,19,41]. Future research should prospectively examine how patient characteristics and coping strategies affect sexual adjustment in order to identify subgroups of men who are at risk for poor sexual adjustment in the long term.

Men with greater sexual bother reported worse general QOL and were more likely to report clinically significant levels of depressive symptoms. Although ADT may directly lead to mood changes [42], these findings suggest sexual bother may also play a contributing role. Sexual bother may lead to decrements in global well-being through changes in self-concept and esteem, particularly if sexual ability is central to one’s definition of masculine identity [40]. Given that the majority of men on ADT will never fully recover erectile function even with the use of assistive aids and/or medical intervention [43,44], targeting sexual bother may buffer the negative psychosocial consequences associated with ADT sexual side effects. In this context, addressing sexual difficulties and helping men maintain satisfying sexual relationships might positively affect psychological well-being and general QOL.

In prior work, researchers have recommended that medical interventions for sexual dysfunction be paired with psychosexual counseling and patient education in order to address patient expectations [19]. The majority of men on ADT who use erectile aids discontinue using them within a year, which may reflect disappointment that aids do not restore normative sexual function [19,20]. Counseling and education may be well suited to address modifiable influences on sexual bother and poor adherence to treatment, such as unrealistic expectations regarding sexual recovery, anxiety related to performance, perceived pressure to satisfy one’s partner, rigid adherence to sexual activities based on penetrative intercourse, or perceived loss of manhood and changes in self-esteem and identity [45,46].

Contrary to expectations, greater sexual bother was related to better relationship cohesion and satisfaction. It is generally believed that relationships are negatively affected by cancer-related sexual changes, although there is limited research among couples coping with advanced stage disease. Men who exhibit greater distress related to sexual changes may elicit more support from their partners in this context. Although couples’ communication around sexual dysfunction is often limited [45–48], men with higher levels of distress may be more motivated to overcome communication barriers and problem-solve alternative, non-penetrative sexual activities, thereby maintaining intimacy and relationship closeness [47,49]. Likewise, men may appreciate their partner’s support more than men with less distress. Because the men had agreed to participate in a psychosocial intervention, it is possible that they were more likely to proactively cope with sexual bother, leading to greater appreciation of partner support and relationship closeness.

Sexual bother exists within the dynamics of couples’ interactions and ways of coping with sexual changes in their relationship. In a study of prostate cancer couples, Beck, Robinson, and Carlson [49] found that sexual adjustment was more likely among those who were motivated by relationship intimacy (vs. physical pleasure) and who endorsed attributes of acceptance, flexibility, and persistence. In studies of APC, men and their partners were able to accept or cope with ADT-related sexual changes via strategies such as focusing on the survival benefit of treatment, leaving role responsibilities and division of labor unchanged, modifying sexual relationships, and finding alternative ways of being intimate [17,50,51]. We did not assess couples’ attempts to explore non-penetrative options to maintain sexual intimacy and affection or other mechanisms by which greater sexual bother may be related to better relationship function. Further work is needed to identify factors that contributed to men’s positive feelings about their relationship despite continued sexual bother.

Only a minority of men reported that “not showing love” and “demonstrations of affection” caused disagreements or problems in their relationship (16% and 17%, respectively; DAS items). It is also possible that the DAS, a measure of general relationship function, did not detect associations of sexual bother with problem-specific aspects of relationship distress. In prior work, partners’ negative reactions to ADT side effects (e.g., revulsion toward body changes) have been linked with more adjustment difficulties [40]. We recommend that future studies evaluate patients’ and partners’ perspectives on ways in which sexual bother impacts relationship function and quality over time.

Study limitations include the current cross-sectional design, which precludes directional inferences. Because of lack of access to medical record data and limited patient self-report data for this community-based sample, we were not able to reliably report intermittent vs. continuous treatment or concomitant EBRT. Recent trials have shown potential relative benefits of intermittent ADT on sexual function during off-treatment intervals [4]. Future work should explore sexual bother within this context. As these were secondary analyses, we also did not have access to key variables (e.g., use of erectile aids or medical interventions to promote sexual function) that may have explained or modified observed relationships. The small sample size limited subgroup analyses, particularly among married/partnered participants and across ethnic groups. The extended time since diagnosis likely reduced accurate recall of baseline sexual functioning, and our reliance on retrospective report limited our ability to adjust for baseline sexual functioning in our analyses. We included this scale in order to approximate baseline functioning, given the potential importance of this factor, the limited amount of published information in this area, and the lack of baseline QOL data [52]. It is also unknown whether low reliability of the DAS affectional expression subscale was because of the lack of sensitivity of this subscale in measuring the effects of sexual bother on this aspect of relationship functioning or because of the small sample size of married/partnered participants. Finally, the study sample was composed of men who agreed to participate in a psychosocial intervention study designed to mitigate the effects of cancer diagnosis and treatment on QOL. Thus, the sample may overrepresent men who were experiencing cancer-related distress or dysfunction or who were more likely to proactively seek support resources.

Conclusions

This study adds to a small body of literature highlighting the relevance of sexual bother to psychosocial and QOL outcomes among men with APC undergoing ADT. These preliminary findings suggest that younger men and those in the first year and a half of ADT may be at increased risk for sexual bother, which may relate to psychological morbidity and worse QOL. The psychosocial aspects of sexual functioning should be considered in determining whether men are able to adjust to ADT effects. Psychosocial interventions have been shown to improve sexual function outcomes among men with prostate cancer, although analysis of sexual bother specifically is limited [53]. Future work should identify whether individual vs. targeted treatment approaches reduce sexual bother [54–57] and whether partner and relationship-focused components compliment other intervention strategies [18,58]. It is possible that by targeting modifiable aspects of sexuality (e.g., maladaptive cognitions) and promoting greater knowledge and acceptance of erectogenic treatments, psychosocial interventions might help to reduce sexual bother [19,53], with positive downstream effects on sexual satisfaction, distress, and general QOL. Partners should be included in the sexual recovery process to facilitate open and constructive communication and joint coping efforts [47,49].

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Gomella LG. Contemporary use of hormonal therapy in prostate cancer: Managing complications and addressing quality-of-life issues. BJU Int 2007;99(suppl 1):25–9, discussion 30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roach M Current trends for the use of androgen deprivation therapy in conjunction with radiotherapy for patients with unfavorable intermediate-risk, high-risk, localized, and locally advanced prostate cancer. Cancer 2014;120:1620–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bastian PJ, Boorjian SA, Bossi A, Briganti A, Heidenreich A, Freedland SJ, Montorsi F, Roach Iii M, Schröder F, van Poppel H, Stief CG, Stephenson AJ, Zelefsky MJ. High-risk prostate cancer: From definition to contemporary management. Eur Urol 2012;61:1096–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Botrel TE, Clark O, dos Reis RB, Pompeo AC, Ferreira U, Sadi MV. Bretas, FF. Intermittent versus continuous androgen deprivation for locally advanced, recurrent or metastatic prostate cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Urol 2014;14:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Cancer Society. Hormone (androgen deprivation) therapy for prostate cancer. American Cancer Society. 2013. Available at: http://www.cancer.org/cancer/prostatecancer/detailedguide/prostate-cancer-treating-hormone-therapy (accessed October 22, 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sharifi N, Gulley JL, Dahut WL. Androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. JAMA 2005;294:238–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Casey RG, Corcoran NM, Goldenberg SL. Quality of life issues in men undergoing androgen deprivation therapy: A review. Asian J Androl 2012;14:226–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Corona G, Gacci M, Baldi E, Mancina R, Forti G, Maggi M. Androgen deprivation therapy in prostate cancer: Focusing on sexual side effects. J Sex Med 2012;9:887–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O’Brien R, Rose P, Campbell C, Weller D, Neal RD, Wilkinson C, McIntosh H, Watson E. “I wish I’d told them”: A qualitative study examining the unmet psychosexual needs of prostate cancer patients during follow-up after treatment. Patient Educ Couns 2011;84:200–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katz A The sounds of silence: Sexuality information for cancer patients. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:238–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fode M, Sønksen J. Sexual function in elderly men receiving androgen deprivation therapy (ADT). Sex Med Rev 2014;2:36–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laumann EO, Waite LJ. Sexual dysfunction among older adults: Prevalence and risk factors from a nationally representative U.S. probability sample of men and women 57–85 years of age. J Sex Med 2008;5:2300–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bauer M, McAuliffe L, Nay R. Sexuality, health care and the older person: An overview of the literature. Int J Older People Nurs 2007;2:63–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brody S The relative health benefits of different sexual activities. J Sex Med 2010;7:1336–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eton DT, Lepore SJ. Prostate cancer and health-related quality of life: A review of the literature. Psychooncology 2002;11:307–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Faye BJ, Wilson KG, Chater S, Viola RA, Hall P. Stress and coping with advanced cancer. Palliat Support Care 2006;4:239–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walker LM, Robinson JW. Sexual adjustment to androgen deprivation therapy: Struggles and strategies. Qual Health Res 2012;22:452–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sanchez Varela V, Zhou ES, Bober SL. Management of sexual problems in cancer patients and survivors. Curr Probl Cancer 2013;37:319–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elliott S, Latini DM, Walker LM, Wassersug R, Robinson JW. Androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer: Recommendations to improve patient and partner quality of life. J Sex Med 2010;7:2996–3010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higano CS. Sexuality and intimacy after definitive treatment and subsequent androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:3720–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cooperberg MR, Koppie TM, Lubeck DP, Ye J, Grossfeld GD, Mehta SS, Carroll PR. How potent is potent? Evaluation of sexual function and bother in men who report potency after treatment for prostate cancer: Data from CaPSURE. Urology 2003;61:190–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reeve BB, Potosky AL, Willis GB. Should function and bother be measured and reported separately for prostate cancer quality-of-life domains? Urology 2006;68:599–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Le JD, Cooperberg MR, Sadetsky N, Hittelman AB, Meng MV, Cowan JE, Latini DM, Carroll PR. Changes in specific domains of sexual function and sexual bother after radical prostatectomy. BJU Int 2010;106:1022–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gacci M, Simonato A, Masieri L, Gore JL, Lanciotti M, Mantella A, Rossetti MA, Serni S, Varca V, Romagnoli A, Ambruosi C, Venzano F, Esposito M, Montanaro T, Carmignani G, Carini M. Urinary and sexual outcomes in long-term (5+ years) prostate cancer disease free survivors after radical prostatectomy. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2009;7:94. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-7-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sato Y, Tanda H, Nakajima H, Nitta T, Akagashi K, Hanzawa T, Tobe M, Haga K, Uchida K, Honma I. Dissociation between patients and their partners in expectations for sexual life after radical prostatectomy. Int J Urol 2013;20:322–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zaider T, Manne S, Nelson C, Mulhall J, Kissane D. Loss of masculine identity, marital affection, and sexual bother in men with localized prostate cancer. J Sex Med 2012;9:2724–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Penedo FJ, Benedict C, Zhou ES, Rasheed M, Traeger L, Kava BR, Soloway M, Czaja S, Antoni MH. Association of stress management skills and perceived stress with physical and emotional well-being among advanced prostrate cancer survivors following androgen deprivation treatment. J Clin Psychol Med Settings 2013;20:25–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975;12:189–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV-TR axis I disorders, research version, non-patient edition (SCID-I/NP). New York: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Charlson M, Szatrowski TP, Peterson J, Gold J. Validation of a combined comorbidity index. J Clin Epidemiol 1994;47:1245–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wei JT, Dunn RL, Litwin MS, Sandler HM, Sanda MG. Development and validation of the expanded prostate cancer index composite (EPIC) for comprehensive assessment of health-related quality of life in men with prostate cancer. Urology 2000;56:899–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spanier GB. Measuring dyadic adjustment: New scales for assessing the quality of marriage and similar dyads. J Marriage Fam 1976;38:15–28. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, Sarafian B, Linn E, Bonomi A, Silberman M, Yellen SB, Winicour P, Brannon J, Eckberg K, Lloyd S, Purl S, Blendowski C, Goodman M, Barnicle M, Stewart I, McHale M, Bonomi P, Kaplan E, Taylor S IV, Thomas CR Jr, Harris J. The functional assessment of cancer therapy scale: Development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol 1993;11:570–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schover LR, Fouladi RT, Warneke CL, Neese L, Klein EA, Zippe C, Kupelian PA. Defining sexual outcomes after treatment for localized prostate carcinoma. Cancer 2002;95:1773–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hollenbeck BK, Dunn RL, Wei JT, McLaughlin PW, Han M, Sanda MG. Neoadjuvant hormonal therapy and older age are associated with adverse sexual health-related quality-of-life outcome after prostate brachytherapy. Urology 2002;59:480–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hann D, Winter K, Jacobsen P. Measurement of depressive symptoms in cancer patients: Evaluation of the center for epidemiological studies depression scale (CES-D). J Psychosom Res 1999;46:437–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR, Roberts RE, Allen NB. Center for epidemiologic studies depression scale (CES-D) as a screening instrument for depression among community-residing older adults. Psychol Aging 1997;12:277–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brucker PS, Yost K, Cashy J, Webster K, Cella D. General population and cancer patient norms for the functional assessment of cancer therapy-general (FACT-G). Eval Health Prof 2005;28:192–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Navon L, Morag A. Advanced prostate cancer patients’ ways of coping with the hormonal therapy’s effect on body, sexuality, and spousal ties. Qual Health Res 2003;13:1378–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saylor PJ, Smith MR. Adverse effects of androgen deprivation therapy: Defining the problem and promoting health among men with prostate cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2010;8:211–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cherrier MM, Aubin S, Higano CS. Cognitive and mood changes in men undergoing intermittent combined androgen blockade for non-metastatic prostate cancer. Psychooncology 2009;18:237–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fialka-Moser V, Crevenna R, Korpan M, Quittan M. Cancer rehabilitation. J Rehabil Med 2003;35:153–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Harper JM, Schaalje BG, Sandberg JG. Daily hassles, intimacy, and marital quality in later life marriages. Am J Fam Ther 2000;28:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wittmann D, Northouse L, Foley S, Gilbert S, Wood DP Jr, Balon R, Montie JE. The psychosocial aspects of sexual recovery after prostate cancer treatment. Int J Impot Res 2009;21:99–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wittmann D, Carolan M, Given B, Skolarus TA, An L, Palapattu G, Montie JE. Exploring the role of the partner in couples’ sexual recovery after surgery for prostate cancer. Support Care Cancer 2014. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Badr H, Taylor CL. Sexual dysfunction and spousal communication in couples coping with prostate cancer. Psychooncology 2009;18:735–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Boehmer U, Clark JA. Communication about prostate cancer between men and their wives. J Fam Pract 2001;50:226–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Beck AM, Robinson JW, Carlson LE. Sexual values as the key to maintaining satisfying sex after prostate cancer treatment: The physical pleasure-relational intimacy model of sexual motivation. Arch Sex Behav 2013;42:1637–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Walker LM, Robinson JW. The unique needs of couples experiencing androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. J Sex Marital Ther 2010;36:154–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Walker LM, Robinson JW. A description of heterosexual couples’ sexual adjustment to androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. Psychooncology 2011;20:880–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Reeve BB, Stover AM, Jensen RE, Chen RC, Taylor KL, Clauser SB, Collins SP, Potosky AL. Impact of diagnosis and treatment of clinically localized prostate cancer on health-related quality of life for older Americans: A population-based study. Cancer 2012;118:5679–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chisholm KE, McCabe MP, Wootten AC, Abbott JA. Review: Psychosocial interventions addressing sexual or relationship functioning in men with prostate cancer. J Sex Med 2012;9:1246–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Campbell LC, Keefe FJ, Scipio C, McKee DC, Edwards CL, Herman SH, Johnson LE, Colvin OM, McBride CM, Donatucci C. Facilitating research participation and improving quality of life for African American prostate cancer survivors and their intimate partners. A pilot study of telephone-based coping skills training. Cancer 2007;109:414–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Giesler RB, Given B, Given CW, Rawl S, Monahan P, Burns D, Azzouz F, Reuille KM, Weinrich S, Koch M, Champion V. Improving the quality of life of patients with prostate carcinoma: A randomized trial testing the efficacy of a nurse-driven intervention. Cancer 2005;104:752–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lepore SJ, Helgeson VS, Eton DT, Schulz R. Improving quality of life in men with prostate cancer: A randomized controlled trial of group education interventions. Health Psychol 2003;22:443–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Weber BA, Roberts BL, Resnick M, Deimling G, Zauszniewski JA, Musil C, Yarandi HN. The effect of dyadic intervention on self-efficacy, social support, and depression for men with prostate cancer. Psychooncology 2004;13:47–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Soloway CT, Soloway MS, Kim SS, Kava BR. Sexual, psychological and dyadic qualities of the prostate cancer “couple”. BJU Int 2005;95:780–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]