Abstract

Phage WΦ is a member of the nonlambdoid P2 family of temperate phages. The DNA sequence of the whole early-control region and the int and attP region of phage WΦ has been determined. The phage integration site was located at 88.6 min of the Escherichia coli K-12 map, where a 47-nucleotide sequence was found to be identical in the host and phage genomes. The WΦ Int protein belongs to the Int family of site-specific recombinases, and it seems to have the same arm binding recognition sequence as P2 Int, but the core sequence differs. The transcriptional switch contains two face-to-face promoters, Pe and Pc, and two repressors, C and Cox, controlling Pe and Pc, respectively. The early Pe promoter was found to be much stronger than the Pc promoter. Furthermore, the Pe transcript was shown to interfere with Pc transcription. By site-directed mutagenesis, the binding site of the immunity repressor was located to two direct repeats spanning the Pe promoter. A point mutation in one or the other repeat does not affect repression by C, but when it is included in both, C has no effect on the Pe promoter. The Cox repressor efficiently blocks expression from the Pc promoter, but its DNA recognition sequence was not evident. Most members of the P2 family of phages are able to function as helpers for satellite phage P4, which lacks genes encoding structural proteins and packaging and lysis functions. In this work it is shown that P4 E, known to function as an antirepressor by binding to P2 C, also turns the transcriptional switch of WΦ from the lysogenic to the lytic mode. However, in contrast to P2 Cox, WΦ Cox is unable to activate the P4 Pll promoter.

Temperate phage WΦ was originally isolated from Escherichia coli W, where, in the prophage form, it restricted the growth of phage λ (29). WΦ is serologically unrelated to phage λ, but it is closely related to P2, which it resembles under the electron microscope (29, 40). In spite of its close antigenic relationship to P2, they are not coimmune, since WΦ grows on a P2 lysogen and vice versa (29). A WΦ lysogen restricts not only phage λ but also phages T2 and T4, which indicates that it contains genes equivalent to P2 old and tin (26, 36, 37). Like most other members of the P2 family, WΦ is not inducible by UV light, and it functions as a helper for satellite phage P4 (6).

Satellite phage P4 is a defective phage that lacks genes encoding structural proteins and lysis functions; therefore it requires P2 or a P2-related phage as helper to grow lytically (31). P2 and P4 are unrelated; their sequence homology is less than 1% and is limited primarily to the phage end regions required for DNA maturation and packaging. In the absence of a helper, P4 has the capacity to integrate into the host chromosome and to become a repressed prophage (10, 47) or to establish itself as a multicopy plasmid (15, 24). P4 has the capacity to utilize the P2 helper in a coinfection, after infection of a P2 lysogenic strain, or after P2 infection of a strain containing P4 as a prophage or a plasmid. P4 can gain access to the late genes of a repressed P2 helper in two ways, i.e., transactivation and derepression. Transactivation is mediated by the P4 δ protein, which has the capacity to directly activate the P2 late promoters, bypassing the need for P2 DNA replication, and the P2 Ogr protein, which activates the late promoters during lytic P2 growth (27). Derepression of prophage P2 is mediated by the P4 E protein (23), and recently E has been shown to act as an antirepressor by forming a complex with the P2 immunity repressor C, thereby blocking its capacity to bind to the operator (33). Derepression is mutual; i.e., infection of a P4 lysogenic strain by P2 induces the P4 lytic cycle. The derepression of prophage P4 is mediated by the P2 Cox protein, which acts as a transcriptional activator on the P4 Pll promoter (41, 48). Since P4 is able to derepress P2 as well as WΦ even though they have different immunities, we have determined the DNA sequence of the transcriptional switch of WΦ, determined the location of the promoters and operators, compared the sensitivities of the immunity repressor of the respective phage to the P4 E protein in vivo, and compared the capacity of P2 and WΦ to derepress prophage P4.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals and enzymes.

All enzymes were purchased from Pharmacia, except Vent DNA polymerase, which was obtained from New England Biolabs. [γ-32P]ATP and [14C]chloramphenicol were obtained from Amersham.

The synthetic oligonucleotides used for cloning and sequencing were obtained from DNA Technology (Aarhus, Denmark). They are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Synthetic oligonucleotides used in this study

| Oligonucleotide | Locationa | Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| WΦ-C1his | 1757 | TGC AGA CAT TCG AAA AAC TG |

| WΦ-C2 | 1399 | GAC GCT GTA TTC ACC ATC TTG G |

| WΦ-8R | 1722 | GCT TTC CTA ATC GCT TTC AG |

| WΦ-11R | 1914 | GAA GTC AAT GAC TAT GTG AT |

| WΦ-9L | 1942 | GGG TAC TGA ATC ACA TAG TC |

| Pe-10-R | 1765 | CCT ATT GGT GAC TTA GCT TCC CGT CAA AAG G |

| Pe-10-L | 1802 | CCT TTT GAC GGG AAG CTA AGT CAC CAA TAG G |

| WΦ-O1-R | 1763 | CAG TAA CCT ATT GTG GAC TTA TAT TCC CG |

| WΦ-O1-L | 1790 | CGG GAA TAT AAG TCA CAA ATA GGT TAC TG |

| WΦ-O2-R | 1797 | GGT TGT GTA TTT GTG ACC TTT TGA G |

| WΦ-O2-L | 1822 | CTC AAA AGG TCA CAA ATA CAC AAC C |

| 79.0L | 26362 | GGG TGA TGG TGA AGT CAA TC |

| PSP3-1 | 24045 | TGC CAA AAC GCT GCA CAT GCT CG |

| pKK232-240L | CCT TAG CTC CTG AAA ATC TCG | |

| pACYC177-rev | CGC CCC GAA GAA CGT TTT CC | |

| T7-forward | TAA TAC GAC TCA CTA TAG GG | |

| φ7-for | CCA CAA CGG TTT CCC TCT AG | |

| Universal translational terminator | GCT TAA TTA ATT AAG C |

The location is the position of 5′ base relative to the left end of the P2 genome (79.0L and PSP3-1) or the WΦ sequence shown in Fig. 1.

Media.

Luria-Bertani (LB) broth or LB agar plates were routinely used for growth of bacteria, as described previously (2). When needed, antibiotics were added to the following final concentrations: ampicillin, 50 to 100 μg/ml; kanamycin, 50 to 100 μg/ml; chloramphenicol, 10 to 50 μg/ml.

Bacteria and bacteriophages.

The bacterial strains and bacteriophages used in this study are listed in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

E. coli strains, bacteriophages, and plasmids used in this study

| Strain, phage, or plasmid | Pertinent features | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | ||

| C-1a | F− prototrophic E. coli C strain | 45 |

| C-117 | C-1a lysogenized with P2 | 5 |

| C-6005 | C-1a lysogenized with P2 cox3 | 43 |

| C-1757 | Auxotrophic, supD str | 51 |

| C-1920 | C-1a lysogenized with WΦ | 29 |

| Bacteriophages | ||

| P2 lg | Used as wild type | 4 |

| WΦ | Wild type | 29 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pET-8c | pBR322 derivative containing the T7 promoter | 49 |

| pET16-b | pET vector for His-tagging proteins | 50 |

| pGP1-2 | pBR322 derivative containing the T7 polymerase gene under the control of the inducible λ PL promoter | 52 |

| pKK232-8 | Ampicillin-resistant pBR322 derivative containing a promoterless cat gene | 9 |

| pACYC177 | p15 derivative | 12 |

| pEE719 | pACYC177 derivative with a universal translational terminator inserted into the HincII site | This work |

| pEE720 | pET-8c derivative with the P2 cox gene under control of the T7 promoter | 18a |

| pEE804 | pACYC177 derivative with the P4 ɛ and its upstream region under control of the T7 promoter | 32 |

| pEE900 | pET-16b derivative with the WΦ C gene fused to the 9-histidine tag at the N-terminal end and under control of the T7 promoter | This work |

| pEE901 | pET-8c derivative with the WΦ cox gene under control of the T7 promoter | This work |

| pEE902 | pEE712 derivative containing WΦ C gene under control of the β-lactamase promoter | This work |

| pEE903 | pEE712 derivative containing WΦ cox gene under control of the β-lactamase promoter | This work |

| pEE904 | pKK232-8 derivative with WΦ Pe-Pc region inserted into SmaI site; Pc directs the cat gene | This work |

| pEE905 | pKK232-8 derivative with WΦ Pe-Pc region inserted into SmaI site; Pe directs the cat gene | This work |

| pEE906 | pKK232-8 derivative with WΦ C-Pe-Pc region inserted into SmaI site; Pe directs the cat gene | This work |

| pEE907 | pEE904 derivative with −10 region of Pe promoter changed from TATATT to TAGCTT | This work |

| pEE908 | pEE905 derivative with −10 region of Pe promoter changed from TATATT to TAGCTT | This work |

| pEE909 | pEE905 derivative with site O1 mutated from TATTGGTGAC to TATTTGTGAC | This work |

| pEE910 | pEE905 derivative with site O2 mutated from TATTGGTGAC to TATTTGTGAC | This work |

| pEE911 | pEE905 derivative with both O1 and O2 mutated from TATTGGTGAC to TATTTGTGAC | This work |

| pSS27-4 | A pACYC177 derivative containing the P2 cox gene which is transcribed both from P2 Pe and the β-lactamase promoter | 42 |

| pSS32-1 | pKK232-8 derivative with the cat gene under control of the P2 Pe promoter | 43 |

| pSS39-6 | pKK232-8 derivative with the cat gene under control of the P2 Pc promoter | 41 |

| pSS61-4 | pKK232-8 derivative with the cat gene under control of the P4vir1 promoter Pll; note that in the original publication, the Pll promoter was believed to be wild type | 41 |

Plasmid constructions.

Plasmids were constructed by standard techniques (44). E. coli C-1a was used as the recipient unless otherwise stated. All constructs were verified by automatic DNA sequencing with a Thermo Sequenase fluorescently labelled primer cycle-sequencing kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden).

(i) pEE900.

The WΦ C gene was cloned into the expression vector pET16b under the control of the T7 φ10 promoter. The C gene was amplified from phage WΦ DNA by PCR with primers wφ-C1his and wφ-C2, and the generated PCR fragment was inserted into the filled-in NdeI site of pET-16b. In this way, a histidine tag was added to the N-terminal end of the C polypeptide.

(ii) pEE901.

The WΦ cox gene was cloned into the expression vector pET8c under the control of the T7 φ10 promoter. The cox gene was amplified from phage WΦ DNA by PCR with primers wφ-11R and 79.0L, and the generated PCR fragment was inserted into the filled-in NcoI site of pET-8c.

(iii) pEE902 and pEE903.

pEE902 and pEE903 are derivatives of pACYC177 expressing WΦ C and WΦ Cox, respectively, from the bla promoter of the vector. To avoid interference from translation of the bla gene, a universal translational terminator was inserted into the HincII site of pACYC177, creating plasmid pEE719. The region containing the ribosomal binding site of T7 φ10 and the WΦ C gene was amplified by PCR from plasmid pEE900 with primers φ7-for and wφ-C2. The PCR fragment was inserted into the ScaI site of pEE719 generating pEE902. pEE903 was constructed like pEE902, but the DNA fragment was amplified from pEE901 with primers φ7-for and 79.0L.

(iv) pEE904 and pEE905.

pEE904 and pEE905 are derivatives of the promoter assay plasmid pKK232-8. The WΦ Pe and Pc promoter region was amplified by PCR from phage WΦ DNA with primers wφ-8R and wφ-9L. The generated fragment was inserted in both orientations into the SmaI site of pKK232-8, which contains a promoterless cat gene. In plasmid pEE904, the cat gene is under the control of the Pc promoter, and in plasmid pEE905, it is under the control of the Pe promoter.

(v) pEE906.

pEE906 is the derepression assay plasmid. The WΦ C-Pe-Pc region was amplified from phage WΦ DNA by PCR with primers wφ-C2 and wφ-9L, and the generated fragment was inserted into the SmaI site of pKK232-8. One clone was selected where Pe directs cat gene expression, and the cat gene is repressed due to expression of C from the Pc promoter. Thus, derepression will lead to expression of the cat gene.

(vi) pEE907 and pEE908.

pEE907 and pEE908 are derivatives of pEE904 and pEE905, respectively, where the −10 sequence of Pe promoter was changed from TATATT to TAGCTT by recombinant PCR (28). The Pc promoter directs cat gene expression in pEE907, whereas the Pe promoter controls the cat gene in pEE908.

(vii) pEE909, pEE910, and pEE911.

pEE909, pEE910, and pEE911 are derivatives of pEE905 where the directly repeated sequence TATTGGTGAC, proposed to be the repressor binding site O1 and O2, respectively, was changed to TATTTGTGAC by recombinant PCR (28). The generated plasmid pEE909 contains the mutated base in site O1, pEE910 has site O2 mutated, and pEE911 has both sites mutated.

DNA sequence determination.

To sequence the transcriptional switch region, we amplified the pertinent region from WΦ phage DNA with two P2 primers, PSP3-1 and 79.0L, which are located within the P2 ogr gene and orf78 respectively, using the Advantage Tth polymerase mix kit (Clontech, Palo Alto, Calif.). The PCR product was cloned into the SmaI site of pUC18. Two independent clones were selected for sequencing first with primers on the vector and then extended by primer walking in both directions.

Primer extension assay.

RNA was prepared and concentrated from 50-ml cultures of C-1a carrying plasmid pEE904, pEE905, pEE906, or pEE907, using the QiaGen RNeasy kit. Primers wφ-8R and wφ-9L were 5′-end labelled with [γ-32P]ATP by using T4 polynucleotide kinase. Primer extension assays were carried out with primer extension system VAM reverse transcriptase, as specified by the manufacturer (Promega, Madison, Wis.). Extended cDNAs were separated on 5% polyacrylamide–7 M urea denaturing gel in 1× TBE (50 mM Tris, 100 mM boric acid, 5 mM EDTA). The gel was vacuum dried prior to autoradiography. Sequencing reactions with the same primers as in the extension were performed, and the products were used as markers.

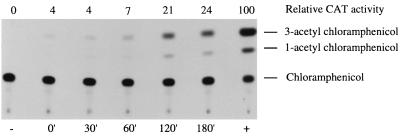

CAT assay.

Chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) assays were performed as described previously (25). Protein concentrations were determined by the method of Bradford (8). CAT activities were quantified with a PhosphorImager and calculated as the ratio of acetylated chloramphenicol to total chloramphenicol.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence data reported in this paper appear in the EMBL/GenBank/DDBJ Nucleotide Sequence Database under accession no. AJ245959.

RESULTS

DNA sequence of the transcriptional switch of phage WΦ.

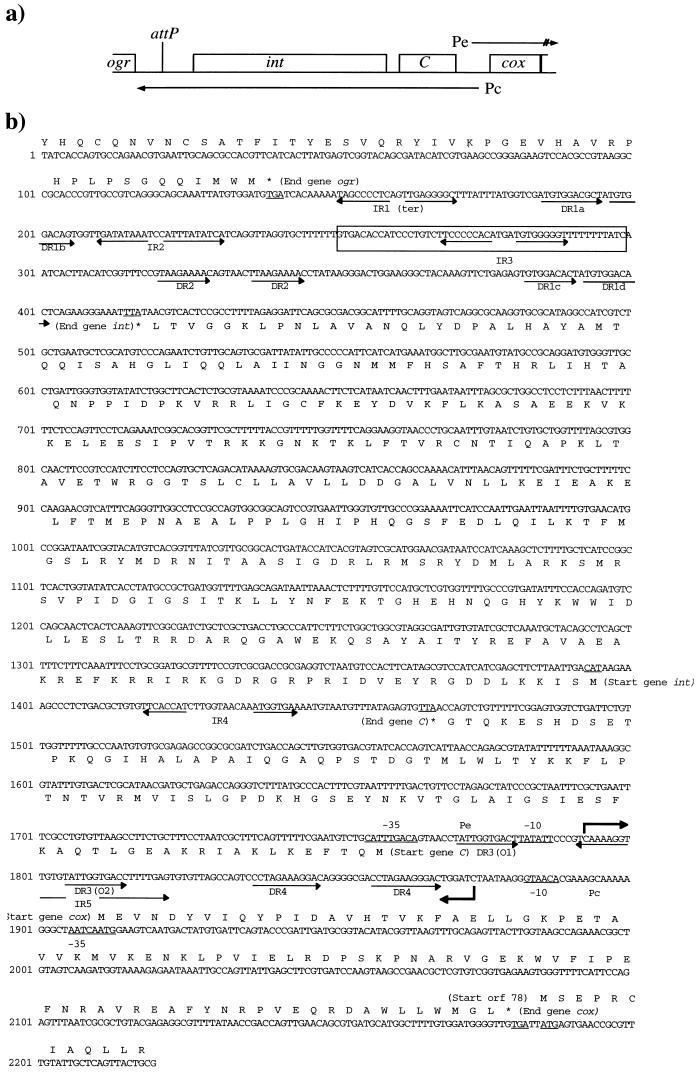

To sequence the transcriptional switch of phage WΦ, attempts were made to amplify the pertinent region by PCR with a P2 primer from a region presumed to be conserved in the P2 family, i.e., ogr, encoding the transcriptional activator of the late genes that is located to the left of the attP site (13), and various primers on the right side of attP. We found that WΦ had sequences analogous to the P2 ogr gene and P2 orf78, located downstream of cox. The amplified fragment was cloned, and its DNA sequence was determined. The DNA sequence and the inferred amino acid sequence of the encoded proteins are shown in Fig. 1b. The transcriptional region seems to have a similar arrangement to other members of the P2 family, i.e., it has two face-to-face promoters, Pe controlling the early genes and Pc controlling the genes believed to be involved in lysogeny (Fig. 1a). Based on the location of the open reading frames, we have adopted the nomenclature of phage P2, calling the first gene of the Pe transcript cox and the two open reading frames of the Pc transcript C and int respectively.

FIG. 1.

(a) Schematic drawing of the transcriptional switch region of WΦ phage. The rightward transcript Pe is indicated on the top, and the leftward transcript Pc is shown on the bottom. attP is indicated, and the open reading frames named int, C, and cox are boxed. The coding region for ogr is represented by an open box. (b) Nucleotide sequence of the 2,220-bp region from phage WΦ DNA together with the deduced amino acid sequences of the open reading frames. ogr and orf78 are partly represented. Inverted repeats (IR) and direct repeats (DR) are indicated by back-to-back and rightward arrows, respectively. The core sequence of attP is indicated by a box. The predicated −10 and −35 sequences of the respective Pe and Pc promoter are underlined. The transcriptional start sites of Pe and Pc are indicated by bent arrows. The translational start and stop codens are also underlined.

The WΦ integrase belongs to the Int family of site-specific recombinases.

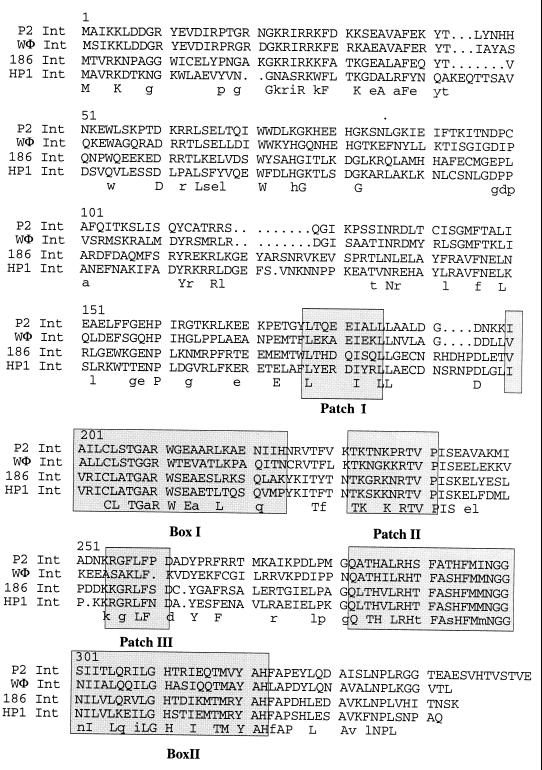

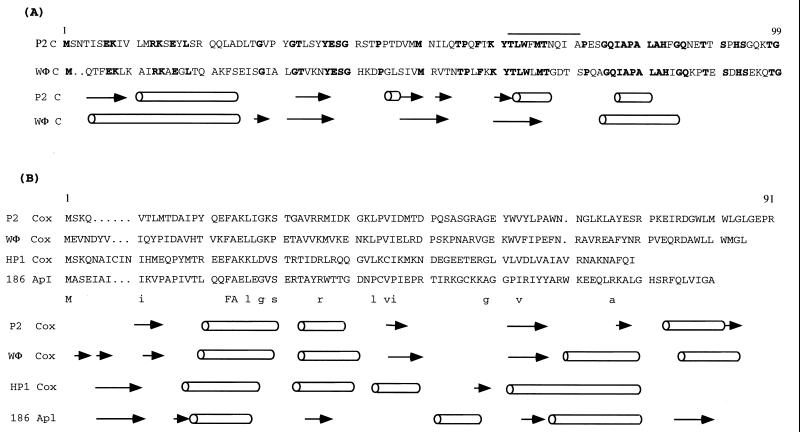

An alignment of 105 site-specific recombinases of the Int family has demonstrated two conserved boxes and three conserved patches of charged amino acids (39). Box I contains the invariant Arg residue, and box II contains the His-X-X-Arg motif and the active site Tyr. As can be seen in Fig. 2, WΦ contains the conserved residues of box I and box II. Patch I contains a group of acidic amino acid separated by hydrophobic residues and has the consensus sequence LT-EEV--LL. Patch II contains a well-conserved Lys flanked by Ser or Thr in one subgroup and by Gly or Met in another. Minor variations of this motif are also found. Patch III is rich in Phe and is preceded by acidic residues and often followed by polar residues. The consensus sequence is [D/E]-[F/Y/W/L/I/A]3-6[S/T]. The WΦ Int protein conforms to the general themes of the Int family of recombinases (Fig. 2), but it differs quite extensively at the N-terminal part from the integrases of the P2-related phages 186 and HP1. It should also be noted that the WΦ int gene has two possible start codons, but since only the second Met codon is preceded by a ribosome binding site, it most probably constitutes the initiation codon. An evolutionary analysis has indicated that the HP1 and 186 integrases are more closely related to each other (55% identity) than to P2 Int (35 and 37% identity, respectively) (20), and we found in turn that WΦ is more closely related to P2 (56% identity) than to HP1 and 186 (35 and 39%, respectively).

FIG. 2.

Alignment of the Int amino acid sequences of four P2-related phages. Boxes I and II and patches I, II, and III are shaded. The identical residues are summarized in capital letters under the alignment, and those identical in three sequences are shown in lowercase letters.

Localization of the WΦ attP and attB sites.

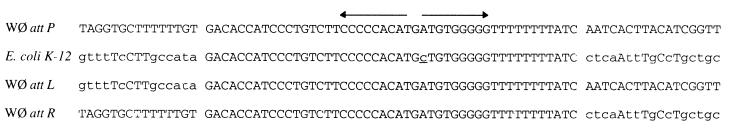

The site of integration of phage WΦ upon lysogenization has previously not been determined, but the sequence between ogr and int lacks the 27-nucleotide (nt) core sequence of P2; thus, it most probably integrates at a different chromosomal location. Since the DNA sequence between ogr and int is expected to contain the attachment site, a BLASTN search was performed against the E. coli K-12 genome. A 47-nt region with only one mismatch was found, located between cpxR and pfkA at 88.6 min on the E. coli K-12 map (Fig. 3). To confirm the location of the integration site, the phage host junction fragments were amplified from a WΦ lysogen with primers located on either side of the hypothesized integration site of the E. coli genome in combination with primers from the phage int and ogr genes. A nonlysogenic strain gave the expected PCR fragment when the E. coli primers were used, but no fragment was obtained from the WΦ lysogen. Instead, the lysogen gave PCR fragments when the E. coli primers were combined with the pertinent WΦ primers. The generated fragments were sequenced, confirming the integration of WΦ at this location (Fig. 3). The mismatched C residue, located in the center of the dyad symmetry of the identity region, was not present in the WΦ lysogen, which was an E. coli strain C derivative; thus, this might constitute a strain variation.

FIG. 3.

Alignment of the core sequence and its flanking nucleotides of phage WΦ and its host E. coli K-12 together with the attL and attR sequence of WΦ prophage. The inverted repeat is indicated by back-to-back arrows. The mismatched nucleotide located in E. coli K-12 is underlined. Identical nucleotides are capitalized.

The members of the Int family of site-specific integrases have two DNA binding motifs recognizing different DNA sequences, the core sequence and the arm sequences. The core sequence normally has an inverted repeat (11), which also can be found in the identity region of WΦ and the E. coli genome (Fig. 1b). The arm sequence, i.e., the DNA sequences flanking the core sequence, was analyzed for the presence of inverted or direct repeats. As can be seen in Fig. 1b, besides the inverted repeat in the core, the region contains two additional inverted repeats, IR1 and IR2. IR1 most probably acts as a terminator for both the ogr and the int transcripts, since both transcripts will have a poly(U) tail following the stem-loop structure. If so, the int transcript will continue into the host chromosome in the prophage state. The region also contains several direct repeats. Interestingly, four of them have a common consensus sequence, aTGTGGACact, which is identical to the consensus sequence of the arm binding sites of P2 integrase (55). Thus, they most probably constitute the arm binding site of WΦ integrase as well.

No sequence corresponding to the P2 Cox binding site could be detected between the core sequence and the presumed arm binding sites of the attP region of WΦ, which implies that WΦ Cox has a different recognition sequence from that of P2 Cox.

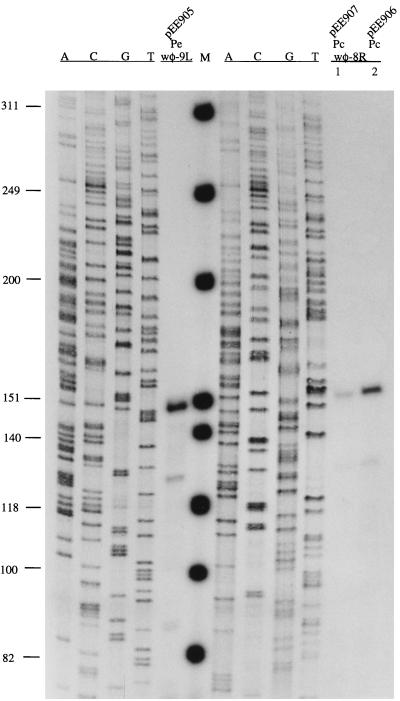

Localization of the Pe and Pc promoters.

The DNA sequence between the C and cox genes, which are transcribed in opposite orientations, is expected to contain the transcriptional control region. The region contains a potential rightward promoter (Pe) just upstream of the initiation codon of gene C, with good −10 and −35 regions spaced by 17 nt and a potential leftward promoter (Pc) just upstream of the initiation codon of gene cox, which conforms less well with the canonical E. coli promoter (Fig. 1b). The location of these promoters was confirmed by a primer extension analysis. The Pe-Pc promoter region (nt 1722 to 1942 in Fig. 1b) was cloned into the reporter plasmid, in both orientations, in front of the cat reporter gene. In plasmid pEE904 the cat gene is controlled by the Pc promoter, and in pEE905 it is controlled by the Pe promoter. Total RNA was extracted, and primers wφ-8R and wφ-9L, each located about 150 nt downstream of the proposed promoter Pc and Pe transcriptional start site, respectively, were used for the primer extension. RNA extracted from cells containing plasmid pEE905 generated a fragment of the expected size, i.e. 150 nt (Fig. 4, promoter Pe). The Pe transcriptional start site was further located to position 1793, residue C in Fig. 1b, by running a sequencing reaction beside the primer extension. RNA extracted from cells containing plasmid pEE904 generated no labelled fragment in the primer extension analysis, most probably due to interference by transcription from the stronger Pe promoter. To block transcription from Pe, the −10 region of the Pe promoter in plasmid pEE904 was changed from TATATT to TAGCTT, generating plasmid pEE907. By using RNA extracts from cells containing plasmid pEE907, a weak band of the expected size was obtained in the primer extension analysis (Fig. 4, promoter Pc, lane 1). The exact start site was located to position 1875, residue G in Fig. 1b, by running a sequencing reaction beside the fragment generated by primer extension.

FIG. 4.

Autoradiograph of the primer extension products. Labelled primers wφ-9L and wφ-8R were annealed to RNA extracted from cells containing plasmid pEE905 (Pe) and pEE907 (Pc, lane 1) or pEE906 (Pc, lane 2). The corresponding sequence markers indicated as A, C, G, and T are positioned on the left side of the respective cDNA. Molecular markers (M) (in base pairs) are from end-labelled φX174 HinfI restriction fragments.

An alternative approach to blocking the Pe promoter would be to turn it off by using the immunity repressor. Thus, plasmid pEE906, containing the C-Pe-Pc region where the Pe transcript is turned off by the C repressor, was used. RNA extracted from the cells containing pEE906 gave the same Pc transcript as plasmid pEE907 in the primer extension analysis, but the intensity of the generated fragment was higher (Fig. 4, promoter Pc, lane 2). These results indicate that transcription from Pe inhibits transcriptional initiation from Pc.

Promoter Pe is much stronger than promoter Pc, and it is controlled by the C repressor.

To quantitate the strength and regulation of the face-to-face-located Pe and Pc promoters further, the level of cat expression in strain C-1a containing plasmid pEE904 (cat under the control of Pc) and pEE905 (cat under the control of Pe) was determined. First, the capacity of cells harboring the respective plasmid to grow on LB agar plates supplemented with 50 μg/ml chloramphenicol was analyzed. Cells containing plasmid pEE905 grow well, whereas cells carrying pEE904 do not grow at all. Instead, they grow on plates containing 10 μg of chloramphenicol per ml, which implies that promoter Pe is stronger than promoter Pc, in agreement with the results of the primer extension experiment described above. The strength of the respective promoter was then quantified by determining the level of CAT expression. As can be seen in Table 3, experiment 1, the level of CAT expression in cells with the cat gene under control of the Pc promoter (pEE904) was hardly detectable and the activity was at least 100-fold lower compared to that obtained with the Pe promoter (pEE905). This situation seems very similar to what has been observed with phage P2, where transcription from the Pe early promoter interferes with initiation from the Pc promoter. To analyze the possible interference of transcription initiated from the strong WΦ Pe promoter on Pc, as described above, the two conserved bases in the −10 region of the Pe promoter were changed (from TATATT to TAGCTT) by site-directed mutagenesis. As can be seen in Table 3, experiment 1, the level of CAT expression from the mutated Pe promoter (pEE908) was reduced 33-fold compared to that from the wild-type Pe promoter (pEE905), as expected. At the same time, the level of expression from the Pc promoter in the presence of the mutated Pe promoter (pEE907) increased fivefold, supporting the hypothesis that the strong transcriptional initiation from Pe interferes with the activity of Pc.

TABLE 3.

Assays of promoter strength in presence or absence of repressors in a cat reporter system

| Plasmid containeda | WΦ-Pec | WΦ-Pcc | WΦ-Cc | Operon | Relative CAT activityb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expt 1 | |||||

| pEE905 | + | + | − | Pe-cat | 100 |

| pEE904 | + | + | − | Pc-cat | 0.6 |

| pEE907 | Pe− | + | − | Pc-cat | 4 |

| pEE908 | Pe− | + | − | Pe−-cat | 3 |

| Expt 2 | |||||

| pSS32-1 | P2-Pe | P2-Pc | − | P2/Pe-cat | 100 |

| pSS32-1 | P2-Pe | P2-Pc | P2-C | P2/Pe-cat | 8 |

| pSS32-1 | P2-Pe | P2-Pc | + | P2/Pe-cat | 100 |

| pEE905 | + | + | − | WΦ/Pe-cat | 100 |

| pEE905 | + | + | P2-C | WΦ/Pe-cat | 100 |

| pEE905 | + | + | + | WΦ/Pe-cat | 3 |

| Expt 3 | |||||

| pEE905 | + | + | − | Pe-cat | 100 |

| pEE905 | + | + | + | Pe-cat | 6 |

| pEE909 | O1 | + | − | Pe-cat | 196 |

| pEE909 | O1 | + | + | Pe-cat | 10 |

| pEE910 | O2 | + | − | Pe-cat | 184 |

| pEE910 | O2 | + | + | Pe-cat | 4 |

| pEE911 | O1O2 | + | − | Pe-cat | 196 |

| pEE911 | O1O2 | + | + | Pe-cat | 198 |

Experiment 1 involves comparison of the strength of WΦ promoters Pe and Pc. The specific activity of CAT was normalized to that of the Pe promoter, which was set at 100. Experiment 2 assesses the effect of the WΦ and P2 C repressors on the homologous and heterologous Pe promoters. WΦ C was supplied from the WΦ lysogenic host cell C-1920, while P2 C was supplied from the P2 lysogenic host cell C-117. The activity of CAT was normalized to that of the P2 Pe promoter in the absence of C, which was set at 100. Experiment 3 assesses the effect of mutations in the proposed O1 and O2 operator sites on the binding of WΦ C repressor to the Pe promoter. The CAT activity was normalized to that of the WΦ Pe promoter in the absence of the C repressor, which was set at 100. Repressor C was supplied in trans from the WΦ lysogenic host cell, C-1920.

The CAT assay was performed essentially as described previously (43). Each assay mixture contains 0.01 to 0.05 μg of protein extract.

The presence or absence of the promoter/repressor noted above the column is indicated by a plus or a minus sign, respectively. If another promoter/repressor is present, it is indicated.

The WΦ immunity repressor C is expected to control transcription from the early Pe promoter, and by analogy to other temperate phages, it might control its own expression by regulating Pc. Therefore, plasmids pEE904 and pEE905 were transformed into the WΦ lysogenic strain C-1920 and the capacity of the respective plasmid to express CAT was measured as growth on LB agar plates supplemented with 50 μg of chloramphenicol per ml. Strain C-1920, as opposed to the nonlysogenic strain C-1a, carrying pEE905 did not grow on chloramphenicol plates, whereas plasmid pEE904 seemed unaffected by the C repressor, since the level of CAT expression allowed limited growth in either host on the plates with a low concentration of chloramphenicol (data not shown). This confirms that the C repressor inhibits expression from the Pe promoter (pEE905) whereas the Pc promoter (pEE904) seems unaffected under the conditions used.

The WΦ immunity repressor is unable to repress phage P2 early promoter but is sensitive to P4 E.

P2 and WΦ are not coimmune, as previously shown (29). However, as can be seen in Fig. 5A, the C proteins of P2 and WΦ are related (43 of 97 amino acids are identical). The identities are more prominent in the C-terminal half of the proteins, but the predicted secondary structures are also similar in the N-terminal part of the proteins. The active form of P2 C protein is believed to be a dimer, and the dimerization domain has been located to the C-terminal part of the protein (33, 34). To analyze the interaction of the immunity repressor proteins of P2 and WΦ on the homologous or heterologous early promoters, we have used reporter plasmids that contain the respective Pe-Pc region in front of a promoterless cat gene so that the cat gene is under the control of the Pe promoter. The expression of the cat gene was then analyzed in the presence of the respective C protein provided in trans from lysogenic host cells. As can be seen in Table 3 experiment 2, each promoter is repressed by its homologous repressor but not by the heterologous repressor.

FIG. 5.

Amino acid sequence alignments and predicted secondary structures based on the conservation number from the Jpred program (14). Cylinders indicate helices, and arrows indicate β-sheets. (A) Repressor C of phage P2 and WΦ. The identical residues are shown in bold type. The proposed E binding site is indicated by a line above the P2 C sequence. (B) Cox/Apl proteins of phage P2, WΦ, HP1, and 186. The identical residues are summarized in capital letters under the alignment, and those identical in three sequences are shown in lowercase letters. The residue numbers above the sequence refer to P2 Cox.

P2 C has been shown by footprint analysis to bind to a region containing a direct repeat of the GTTAGAT sequence, which flanks the −10 region of the early promoter (43). WΦ also contains a direct repeat flanking the −10 region, with the sequence TATTGGTGAC, which thus might constitute the operator (Fig. 1b). To test this possibility, the respective direct repeat in the reporter plasmid was changed to TATTTGTGAC and the capacity of the WΦ C protein supplied in trans from the WΦ-lysogenized host cell to repress cat expression was analyzed. As can be seen in Table 3, experiment 3, the mutation in either site O1 (pEE909) or site O2 (pEE910) did not affect the capacity of repressor C to block the early promoter, since the CAT activity was reduced by C to the same level as that obtained with the wild-type Pe promoter, although the mutation in site O1 made the promoter slightly more sensitive to repression by C compared to the results obtained with the mutation in site O2. Mutations in both sites (pEE911), however, rendered the early promoter insensitive to the C protein, which indicates that this direct repeat contains the recognition sequence of the C protein and that both sites are required for the C repressor to bind and block the activity of the Pe promoter. It should also be noted that in the absence of the C repressor, the mutation on either or both operator sites increased the activity of Pe twofold (Table 3, experiment 3). This implies that the changes made in the DNA sequence affect the binding of RNA polymerase to the promoter region.

P4 has the capacity to form plaques on a WΦ lysogen with about the same plating efficiency as on a P2 lysogen (data not shown). Thus, P4 has the capacity to activate the late genes of prophage WΦ. Whether the activation occurs by a direct transactivation of the late promoters by the P4 δ protein or by derepression mediated by the P4 antirepressor E or both is not known. To analyze if P4 E acts as an antirepressor on the C repressor of WΦ, the whole C-Pe-Pc region was cloned into a reporter plasmid in such a way that the cat gene was under the control of the Pe promoter, which in turn was repressed by the C protein (pEE906). This plasmid thus mimics the lysogenic condition. The addition of P4 E in trans from a compatible plasmid (pEE804) leads to expression of the cat reporter gene (Fig. 6), which implies that E derepresses the WΦ Pe promoter by interacting with the immunity repressor C, as in phage P2.

FIG. 6.

Autoradiograph of CAT assay results from derepression of prophage WΦ by P4 E protein in the two-plasmid assay. The cells were prepared essentially as described previously (32). Samples were taken at different time points before and after isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) induction of P4 E, as indicated at the bottom. Cell extracts contain 0.1 μg of protein in each assay mixture. −, control sample containing pKK232-8; +, control sample containing pSS32-1, which is the fully expressed P2 Pe promoter. CAT activity is normalized to that of P2 Pe promoter, which is set at 100.

WΦ Cox protein is a negative regulator of its own Pc promoter, but it cannot functionally replace P2 Cox during excision of prophage P2 or derepress the P4 Pll promoter.

The Cox protein of phage P2 is a multifunctional protein. It is a negative repressor of the P2 Pc promoter (42), an activator of the Pll promoter of the unrelated satellite phage P4 (41), and an architectural protein required for excision of P2 prophage (55). A comparison of the Cox proteins of WΦ to other members of the P2 family, i.e., P2, 186, and HP1, reveals very few sequence identities (Fig. 5B). However, as with the C protein, P2 and WΦ Cox are more closely related to each other than to HP1 Cox and 186 Apl, and the predicated secondary structures indicate similarities only at the N terminal, believed to contain the α-turn–α-helix mediating DNA binding.

P2 cox mutants are able to form lysogens, but the lysogens are unable to release phage spontaneously during growth. To analyze if WΦ Cox is able to functionally replace P2 Cox, a P2 cox-defective lysogen (C-6005) carrying plasmid pGP1-2, which contains a temperature-inducible T7 polymerase, was transformed with the Cox-expressing plasmid (pEE901) and the capacity of the lysogen to produce P2 was determined after growth at 30°C overnight since the overexpression of Cox at 42°C is lethal. As can be seen in Table 4, the cox defective lysogen was unable to produce P2 spontaneously but the P2 cox-containing plasmid (pEE720) readily complemented the cox-defective prophage at 30°C to a level comparable to a wild-type P2 lysogen (C-117) transformed with the same plasmid. However, when the lysogen was transformed with a plasmid containing the WΦ cox gene (pEE901), no complementation was observed. Thus, the WΦ Cox protein cannot replace P2 Cox and promote spontaneous phage production during growth of a cox defective P2 lysogenic strain.

TABLE 4.

Effects of WΦ Cox or P2 Cox on spontaneous phage production in a P2 cox defective lysogen

| Strain and plasmida | Phage titer (PFU/ml) | Bacterial titer (CFU/ml) | phage/bacterium ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| C-117 | |||

| — | 1.4 × 106 | 5.7 × 108 | 2.5 × 10−3 |

| pEE720 | 1.6 × 105 | 7.2 × 105 | 2.8 × 10−1 |

| pEE901 | 4.7 × 105 | 4.5 × 108 | 1.0 × 10−3 |

| C-6005 | |||

| — | 7.0 × 102 | 4.7 × 108 | 1.5 × 10−6 |

| pEE720 | 9.0 × 105 | 1.3 × 106 | 6.9 × 10−1 |

| pEE901 | 7.0 × 102 | 3.5 × 107 | 2.0 × 10−5 |

The cells containing the plasmids indicated in the table were grown without aeration at 30°C overnight in LB medium supplemented with KP buffer to avoid readsorption of released phage (3), and the titers of free phage and bacteria were determined. The bacterial strains carry plasmid pGP1-2, which contains the T7 polymerase gene under λ PL control.

To quantitate the activity of the WΦ Cox protein on the homologous Pc promoter and the heterologous Pc promoter of P2, we used the reporter constructs described above, where the cat gene is under the control of WΦ Pc (pEE907) or P2 Pc (pSS39-6) and Cox was supplied in trans from the compatible plasmid pEE903. As described above, the WΦ Pc promoter was very weak compared to the Pe promoter, and this phenomenon is due in part to the interference of the strong Pe promoter. Even though the activity of the Pc promoter was increased when the −10 region of Pe promoter was mutated, we still found that it was too weak for analysis of the effects of Cox by using CAT expression in the reporter system. However, since bacteria containing pEE907 were able to grow on plates supplemented with 10 μg of chloramphenicol per ml, the effects of Cox on Pc could be analyzed on plates. As shown in Table 5, in the absence of either WΦ Cox or P2 Cox, the host cells expressing CAT under the control of WΦ phage Pc promoter (pEE907) can grow well on plates containing 10 μg of chloramphenicol per ml but not on plates containing 25 μg/ml and they do not grow at all in the presence of WΦ phage Cox (pEE903), whereas the heterologous P2 Cox (pSS27-4) does not inhibit the growth of the cells. Conversely, the cells harboring pSS39-6, in which the P2 Pc promoter directs CAT expression, grew poorly in the presence of P2 Cox but they grew well when the heterologous WΦ phage Cox was supplied in trans. This indicates that the WΦ phage Cox acts as a repressor to control the expression of its own Pc promoter and that the respective Cox protein is unable to act on the heterologous Pc promoter, in support of our previous results indicating that the Cox proteins have different DNA binding sites.

TABLE 5.

Effect of P2 and WΦ Cox proteins on the homologous and heterologous Pc promotera

| Reporter plasmid | Growth with or without cox-expressing plasmid on chloramphenicol atb:

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 μg/ml

|

25 μg/ml

|

|||||||

| pEE903 (WΦ Cox)

|

pSS27-4 (P2 Cox)

|

pEE903 (WΦ Cox)

|

pSS27-4 (P2 Cox)

|

|||||

| Absent | Present | Absent | Present | Absent | Present | Absent | Present | |

| pEE904 (WΦ Pc-cat) | + | − | + | NT | − | − | − | NT |

| pEE907 (WΦ Pc-cat) | ++ | − | ++ | ++ | + | − | + | + |

| pSS36-9 (P2 Pc-cat) | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | − |

The Pc promoter in the reporter plasmids controls the expression of the cat gene, and the capacity of cells transformed with the reporter plasmid with or without the cox-expressing plasmids to grow on chloramphenicol plates was determined.

++, cells grow very well; +, cells grow but poorly; −, no cell growth; NT, not tested.

Finally, the capacity of WΦ Cox to activate the P4 Pll promoter was analyzed. Cells carrying reporter plasmids containing either the wild-type or the vir1-mutated (pSS61-4) P4 Pll promoter controlling the expression of cat gene were transformed with a compatible plasmid expressing the cox gene. As shown in Table 6, with the P4 vir1 Pll promoter, the activity of CAT was increased 16-fold in the presence of P2 Cox. In contrast, the WΦ Cox did not seem to have any effect on the activity of the Pll promoter. Similar results were obtained with the wild-type promoter, but the enzyme levels were reduced. These data are in agreement with the finding that WΦ infecting a P4 lysogen does not lead to any significant P4 production (48a).

TABLE 6.

Effect of WΦ and P2 Cox proteins on the P4 Pll promoter

| Plasmid(s) contained | P4 vir1 Pll-cat present | Cox present | Relative CAT activitya |

|---|---|---|---|

| pSS61-4 | + | − | 1 |

| pSS61-4, pSS27-4 | + | P2-Cox | 16 |

| pSS61-4, pEE903 | + | WΦ-Cox | 1.5 |

The CAT activity was normalized to that of the Pll promoter in the absence of Cox, which was set at 1.

DISCUSSION

The P2 family of bacteriophages were originally placed in a common group of temperate phages on the basis of host range, noninducibility by UV light (with the exception of phage 186), serologic unrelatedness to phage λ, and capacity to act as helpers for the unrelated satellite phage P4 (7). The members of the family have similar morphology, i.e., an icosahedral head, a base plate, and a contractible tail with tail fibers, which classifies them as belonging to the Myoviridiae family of phages. By DNA sequence homology, phages with different host ranges have been found to belong to the P2 family, i.e., Haemophilus influenzae phage HP1 (19) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa phage ΦCTX (38). In this work we have analyzed the lysogenic-lytic control region of phage WΦ and compared it to that of P2 and 186, which are the two best-characterized members of this family.

Prophage location and the site-specific recombination system.

The integration site was located to 88.6 min on the E. coli K-12 map, and it differs from any known integration sites of phage P2 (1) and 186 (53). The site of integration is in the 1,880-nt spacer between cpxR and pfkA. The spacer region contains a 504-nt open reading frame of unknown function, but since the 47-nt sequence common to E. coli and WΦ is located outside this open reading frame, integration does not seem to interrupt any coding part of the host genome. An alignment of the amino acid sequence of the WΦ integrase clearly showed that it belongs to the Int family of recombinases, since it contains all the conserved motifs including the catalytic site in the C-terminal end (39). Interestingly, a repeated sequence identical to the P2 Int arm binding sites was found on either side of the 47-nt core sequence. This indicates that even though the core binding domains of WΦ and P2 Int differ, they have identical arm binding domains. In fact, the arm binding domain of P2 Int has been suggested to be located at the N-terminal end, where 18 of the first 20 nt are identical in the two proteins (54). The arrangements of the presumed Int binding sites in WΦ are very similar to those in P2; i.e., the core sequence contains an inverted repeat while the arm binding sites contain direct repeats.

The P2 Cox protein binds between the core and the P′ arm binding sites of Int, in a region containing six copies of the Cox recognition sequence with the consensus sequence TTAAA(G/C)NC(A/C) (55). This sequence is not found in the WΦ attP region, and since WΦ is unable to complement a cox defective P2 lysogen to allow spontaneous phage production, we believe that WΦ Cox and P2 Cox do not recognize the same DNA sequence. However, it cannot be excluded that WΦ has another gene encoding a specific excisionase.

Structure of the transcriptional switch and specificity of the repressors for their target sites.

Sequence analysis of the transcriptional switch region shows that phage WΦ has a similar gene organization to other phages of the P2 family; i.e., it contains two face-to-face promoters (Pe and Pc) that control phage development, and the first gene of each transcript is a repressor of the other transcript (C and Cox) (Fig. 1) (17, 22, 43). In this way, the promoters are mutually exclusive, and if Pe takes command after infection, Cox represses Pc and lytic growth is ensured. If, on the other hand, Pc takes command, C represses Pe and the phage enters the lysogenic cycle.

The transcriptional initiation sites were determined by primer extension experiments, and the strength and control of the promoters were analyzed in vivo by using a plasmid reporter system where the respective promoter controlled the expression of the cat gene and the repressors were supplied in trans from compatible plasmids or from a lysogenic cell. The results show that the early WΦ promoter Pe is much stronger than the Pc promoter and that transcription initiated at Pe inhibits Pc. Similar findings have been reported for P2 and 186 (17, 42, 43).

The WΦ immunity repressor C efficiently blocks the early Pe promoter, and the proposed operator sequence was identified by site-directed mutagenesis as directly repeated 10-nt sequences on either site of the −10 region of Pe spaced by 24 nt; thus, the two operators do not seem to be in phase with each other. A point mutation in one or the other operator has no effect on the capacity of C to repress Pe, but when contained in both operators, the Pe promoter becomes insensitive to the C repressor. The P2 operator region also contains a directly repeated sequence, but it is slightly shorter, 8 nt, and the sequence differs from WΦ, as expected since the two phages are heteroimmune (35). In both phages the operators are located on either side of the −10 region of Pe, but the P2 operators are separated by 22 nt only (43). The C proteins of P2 and WΦ are of about the same size, 99 and 97 amino acids, respectively, and they have 42% identity and very similar predicted secondary structures, indicating that they are functionally similar (Fig. 5A). The P2 C protein has a strong dimerization domain, which is believed to be located at the C-terminal end (33), but since neither P2 nor WΦ C has an α-turn–α-helix structure typical of prokaryotic repressors, the DNA-interacting epitope remains unknown. The immunity repressors of phage 186 and HP1 are larger (188 amino acids) and have no homology to WΦ or P2; their operators seem to contain inverted repeats (16, 19, 22, 30).

The Cox/Apl proteins of phages P2, HP1, and 186 are small (79 to 91 amino acids) and have dual functions; i.e., they act both as transcriptional repressors and mediators of excisive recombination (18, 21, 22, 30, 42, 55). In this work, we showed that WΦ Cox acts as a repressor of the Pc promoter and that it has no activity on the P2 Pc promoter, in agreement with the finding that they do not seem to have a common DNA recognition sequence. Since the involvement of WΦ Cox in excision has not yet been demonstrated, it is not clear whether WΦ Cox also has dual functions.

Interaction with satellite phage P4.

The defective phage P4 needs a helper to grow lytically, since it lacks genes encoding structural proteins and DNA-packaging and lysis functions (31). P4 has the capacity to derepress a P2 prophage to gain access to the P2 late genes, but it is unable to derepress a 186 prophage (46, 48). Derepression of prophage P2 is mediated by P4 E, which acts as an antirepressor by binding to the P2 C protein (23, 33). The antirepressor function of P4 E seems to occur by formation of multimeric complexes of E and P2 C that prevent the binding of C to its operator. In this work, we have shown that P4 E efficiently also turns the WΦ transcriptional switch from the lysogenic to the lytic state. The region of P2 C that is believed to interact with E has been located to amino acids 62 to 72 (33). As can be seen in Fig. 5A, this region is well conserved between the two phages, which might explain why E can bind to both of them.

The derepression capacity of P2 and P4 is mutual; i.e., P2 has the capacity to derepress prophage P4. The P2 derepression of prophage P4 is mediated by the Cox protein, which functions as a transcriptional activator of the Pll promoter of P4 (41, 48). However, in this work we have found no evidence for an interaction between WΦ Cox and the P4 Pll promoter, in accordance with the finding that WΦ infection of a P4 lysogen will not lead to any significant P4 phage production (48a). Thus, the interactions of P4 with its helpers differ. For P2, the derepression capacity is mutual; i.e., P4 will derepress a P2 prophage and vice versa. With WΦ, it works only one way; i.e., P4 is able to derepress prophage WΦ but not the other way around. Finally, phage 186 can function as a P4 helper only in a coinfection. The P2-related phage HP1, which has a different host range from P2 and 186, is not expected to function as a P4 helper since its cohesive ends differ substantially (19).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grant 72 from the Swedish Medical Research Council. T. Liu was supported by the Sven and Lilly Lawski Foundation.

We thank J. M. Eriksson for plasmid pEE720 and Erich Six for unpublished observations and helpful discussions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barreiro V, Haggård-Ljungquist E. Attachment sites for bacteriophage P2 on the Escherichia coli chromosome: DNA sequences, localization on the physical map, and detection of a P2-like remnant in E. coli K-12 derivatives. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:4086–4093. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.12.4086-4093.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bertani G. Studies on lysogenesis. I. The mode of phage liberation by lysogenic Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1951;62:293–300. doi: 10.1128/jb.62.3.293-300.1951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bertani G, Chattoraj D K. Tandem pentuplication of a DNA segment in a derivative of bacteriophage P2: its use in the study of the mechanism of DNA annealing. Nucleic Acids Res. 1980;8:1339–1356. doi: 10.1093/nar/8.6.1339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bertani G, Ljungquist E, Jagusztyn-Krynicka K, Jupp S. Defective particle assembly in wild type P2 bacteriophage and its correction by the lg mutation. J Gen Virol. 1978;38:251–261. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-38-2-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bertani L E. Abortive induction of bacteriophage P2. Virology. 1968;36:87–103. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(68)90119-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bertani L E, Bertani G. Genetics of P2 and related phages. Adv Genet. 1971;16:199–237. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2660(08)60359-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bertani L E, Six E W. The P2-like phages and their parasite, P4. In: Calendar R, editor. The bacteriophages. Vol. 2. New York, N.Y: Plenum Publishing Corp.; 1988. pp. 73–143. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bradford M M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brosius J. Plasmid vectors for the selection of promoters. Gene. 1984;27:151–160. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(84)90136-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Calendar R, Ljungquist E, Deho G, Usher D C, Goldstein R, Youderian P, Sironi G, Six E W. Lysogenization by satellite phage P4. Virology. 1981;113:20–38. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(81)90133-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campbell A M. Chromosomal insertion sites for phages and plasmids. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:7495–7499. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.23.7495-7499.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang A C, Cohen S N. Construction and characterization of amplifiable multicopy DNA cloning vehicles derived from the p15A cryptic miniplasmid. J Bacteriol. 1978;134:1141–1156. doi: 10.1128/jb.134.3.1141-1156.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Christie G E, Haggård-Ljungquist E, Feiwell R, Calendar R. Regulation of bacteriophage P2 late-gene expression: the ogr gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:3238–3242. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.10.3238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cuff J A, Barton G J. Evaluation and improvement of multiple sequence methods for protein secondary structure predication. Proteins. 1999;34:508–519. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0134(19990301)34:4<508::aid-prot10>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deho G, Ghisotti D, Alano P, Zangrossi S, Borrello M G, Sironi G. Plasmid mode of propagation of the genetic element P4. J Mol Biol. 1984;178:191–207. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(84)90139-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dodd I B, Egan J B. DNA binding by the coliphage 186 repressor protein CI. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:11532–11540. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.19.11532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dodd I B, Kalionis B, Egan J B. Control of gene expression in the temperate coliphage 186 VIII. Control of lysis and lysogeny by a transcriptional switch involving face-to-face promoters. J Mol Biol. 1990;214:27–37. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(90)90144-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dodd I B, Reed M, Egan J B. The Cro-like ApI repressor of coliphage 186 is required for prophage excision and binds near the phage attachment site. Mol Microbiol. 1993;10:1139–1150. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb00983.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18a.Eriksson, J. M. Unpublished data.

- 19.Esposito D, Fitzmaurice W P, Benjamin R C, Goodman S D, Waldman A S, Scocca J J. The complete nucleotide sequence of bacteriophage HP1 DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:2360–2368. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.12.2360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Esposito D, Scocca J J. The integrase family of tyrosine recombinases: evolution of a conserved active site domain. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3605–3614. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.18.3605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Esposito D, Scocca J J. Purification and characterization of HP1 Cox and definition of its role in controlling the direction of site-specific recombination. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:8660–8670. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.13.8660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Esposito D, Wilson J C, Scocca J J. Reciprocal regulation of the early promoter region of bacteriophage HP1 by the Cox and CI proteins. Virology. 1997;234:267–276. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Geisselsoder J, Youderian P, Dehó G, Chidambaram M, Goldstein R, Ljungquist E. Mutants of satellite virus P4 that cannot derepress their bacteriophage P2 helper. J Mol Biol. 1981;148:1–19. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(81)90232-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goldstein R, Sedivy J, Ljungquist E. Propagation of satellite phage P4 as a plasmid. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79:515–519. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.2.515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gorman C M, Moffat L F, Howard B H. Recombinant genomes which express chloramphenicol acetyltransferase in mammalian cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1982;2:1044–1051. doi: 10.1128/mcb.2.9.1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haggård-Ljungquist E, Barreiro V, Calendar R, Kurnit D M, Cheng H. The P2 phage old gene: sequence, transcription and translational control. Gene. 1989;85:25–33. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90460-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Halling C, Calendar R, Christie G E, Dale E C, Deho G, Finkel S, Flensburg J, Ghisotti D, Kahn M L, Lane K B, Lin C S, Lindqvist B H, Pierson L S I, Six E W, Sunshine M G, Ziermann R. DNA sequence of satellite bacteriophage P4. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:1649. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.6.1649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Innis M A, Gelfand D H, Sninsky J J, White T J, editors. PCR protocols: a guide to methods and applications. London, United Kingdom: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kerszman G, Glover S W, Aronovitch J. The restriction of bacteriophage lambda in Escherichia coli strain W. J Gen Virol. 1967;1:333–347. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-1-3-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lamont I, Richardson H, Carter D, Egan J B. Genes for the establishment and maintenance of lysogeny by the temperate coliphage 186. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:5286–5288. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.16.5286-5288.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lindqvist B H, Dehó G, Calendar R. Mechanisms of genome propagation and helper exploitation by satellite phage P4. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:683–702. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.3.683-702.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu T, Renberg S K, Haggård-Ljungquist E. Derepression of prophage P2 by satellite phage P4: cloning of the P4 ɛ gene and identification of its product. J Virol. 1997;71:4502–4508. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.6.4502-4508.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu T, Renberg S K, Haggård-Ljungquist E. The E protein of satellite phage P4 acts as an anti-repressor by binding to the C protein of helper phage P2. Mol Microbiol. 1998;30:1041–1050. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ljungquist E, Kockum K, Bertani L E. DNA sequences of the repressor gene and operator region of bacteriophage P2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:3988–3992. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.13.3988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lundqvist B, Bertani G. Immunity repressor of bacteriophage P2. Identification and DNA-binding activity. J Mol Biol. 1984;178:629–651. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(84)90242-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mosig G, Yu S, Myung H, Haggård-Ljungquist E, Davenport L, Carlson K, Calendar R. A novel mechanism of virus-virus interactions: bacteriophage P2 Tin protein inhibits phage T4 DNA synthesis by poisoning the T4 single-stranded DNA binding protein, gp32. Virology. 1997;230:72–81. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Myung H, Calendar R. The old exonuclease of bacteriophage P2. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:497–501. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.3.497-501.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nakayama K, Kanaya S, Ohnishi M, Terawaki Y, Hayashi T. The complete nucleotide sequence of phi CTX, a cytotoxin-converting phage of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: implications for phage evolution and horizontal gene transfer via bacteriophages. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:399–419. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nunes-Duby S E, Kwon H J, Tirumalai R S, Ellenberger T, Landy A. Similarities and differences among 105 members of the Int family of site-specific recombinases. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:391–406. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.2.391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pizer L I, Smith H S, Miovic M, Pylkas L. Effect of prophage W on the propagation of bacteriophages T2 and T4. J Virol. 1968;2:1339–1345. doi: 10.1128/jvi.2.11.1339-1345.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saha S, Haggård-Ljungquist E, Nordström K. Activation of prophage P4 by the P2 Cox protein and the sites of action of the Cox protein on the two phage genomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:3973–3977. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.11.3973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saha S, Haggård-Ljungquist E, Nordström K. The Cox protein of bacteriophage P2 inhibits the formation of the repressor protein and autoregulates the early operon. EMBO J. 1987;6:3191–3199. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02631.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saha S, Lundqvist B, Haggård-Ljungquist E. Autoregulation of bacteriophage P2 repressor. EMBO J. 1987;6:809–814. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb04823.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sasaki I, Bertani G. Growth abnormalities in Hfr derivatives of Escherichia coli strain C. J Gen Virol. 1965;40:365–376. doi: 10.1099/00221287-40-3-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sauer B, Calendar R, Ljungquist E, Six E, Sunshine M G. Interaction of satellite phage P4 with phage 186 helper. Virology. 1982;116:523–534. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(82)90145-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Six E W, Klug C A. Bacteriophage P4: a satellite virus depending on a helper such as prophage P2. Virology. 1973;51:327–344. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(73)90432-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Six E W, Lindqvist B H. Mutual derepression in the P2-P4 bacteriophage system. Virology. 1978;87:217–230. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(78)90127-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48a.Six, E. W. Personal communication.

- 49.Studier F W, Moffat B A. Use of bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase to direct selective high-level expression of cloned genes. J Mol Biol. 1986;189:113–130. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90385-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Studier F W, Rosenberg A H, Dunn J J, Dubendorff J W. Use of T7 RNA polymerase to direct expression of cloned genes. Methods Enzymol. 1990;185:60–89. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)85008-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sunshine M G, Kelly B. Extent of host deletions associated with bacteriophage P2-mediated eduction. J Bacteriol. 1971;108:695–704. doi: 10.1128/jb.108.2.695-704.1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tabor S, Richardson C C. A bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase/promoter system for controlled exclusive expression of specific genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:1074–1078. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.4.1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Woods W H, Egan J B. Integration site of noninducible coliphage 186. J Bacteriol. 1972;111:303–307. doi: 10.1128/jb.111.2.303-307.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yu A, Haggård-Ljungquist E. Characterization of the binding sites of two proteins involved in the bacteriophage P2 site-specific recombination system. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:1239–1249. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.5.1239-1249.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yu A, Haggård-Ljungquist E. The Cox protein is a modulator of directionality in bacteriophage P2 site-specific recombination. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:7848–7855. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.24.7848-7855.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]