Abstract

Purine nucleotide adenosine triphosphate (ATP) is a source of intracellular energy maintained by mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation. However, when released from ischemic cells into the extracellular space, they act as death-signaling molecules (eATP). Despite there being potential benefit in using pyruvate to enhance mitochondria by inducing a highly oxidative metabolic state, its association with eATP levels is still poorly understood. Therefore, while we hypothesized that pyruvate could beneficially increase intracellular ATP with the enhancement of mitochondrial function after cardiac arrest (CA), our main focus was whether a proportion of the raised intracellular ATP would detrimentally leak out into the extracellular space. As indicated by the increased levels in systemic oxygen consumption, intravenous administrations of bolus (500 mg/kg) and continuous infusion (1000 mg/kg/h) of pyruvate successfully increased oxygen metabolism in post 10-min CA rats. Plasma ATP levels increased significantly from 67 ± 11 nM before CA to 227 ± 103 nM 2 h after the resuscitation; however, pyruvate administration did not affect post-CA ATP levels. Notably, pyruvate improved post-CA cardiac contraction and acidemia (low pH). We also found that pyruvate increased systemic CO2 production post-CA. These data support that pyruvate has therapeutic potential for improving CA outcomes by enhancing oxygen and energy metabolism in the brain and heart and attenuating intracellular hydrogen ion disorders, but does not exacerbate the death-signaling of eATP in the blood.

Keywords: Adenosine triphosphate, Mitochondria, Energy metabolism, Oxygen consumption, Gas exchange, Pyruvate

Introduction

In the USA, sudden cardiac arrest (CA) is a major cardiovascular health issue that affects approximately 600,000 patients annually [1–3]. Sustained circulatory collapse deprives the brain of oxygen and nutrition, causing hypoxic brain injury. The associated mortality rate is high (~ 90%) even upon successful return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) [1, 4]. This is attributed to a clinical state called post-cardiac arrest syndrome (PCAS): systemic ischemia–reperfusion injury resulting in a hyperinflammatory status, mitochondrial dysfunction, progressive cellular injuries, and multiple organ dysfunction, of which the most important is persistent neurocognitive dysfunction [5, 6]. Therefore, there is an urgent need for new ways to improve outcomes post-CA [1, 4].

Purine nucleotide adenosine triphosphate (ATP) is a universal currency of intracellular energy transfer. However, when purines are released from ischemic cells into the extracellular space, they act as signaling molecules for inflammatory responses in ischemia–reperfusion injury [7, 8]. Purinergic signaling is a new field of study in resuscitation science [9]. Under physiological conditions, extracellular ATP (eATP) concentration ranges from 10 to 100 nM but rapidly increases to 1–50 μM in response to hypoxia and tissue injury, inducing cell-surface enzymes, ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase 1 (CD39) and ecto-5′-nucleotidase (CD73), that sequentially convert eATP to immune-modulative adenosines [8, 10]. Mammalian cells contain high concentrations of intracellular ATP (5–8 mM), which are maintained by mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation; however, pathological conditions release intracellular ATP into the extracellular space. Therefore, it is critical to question whether an enhancement in intracellular ATP levels by adding mitochondrial substrates, such as pyruvate, is truly beneficial or if it may further increase eATP levels during and after ischemia–reperfusion injury, yielding detrimental death-signaling. The success of an animal experimental model for enhancing mitochondrial ATP production in tissues by intravenously injecting pyruvate has been reported [11–13]. However, little is known about a link between enhanced mitochondrial ATP production and eATP levels in PCAS.

A therapeutic potential of intravenous pyruvate infusion has been discussed for the past 20 years [11, 14]. Neonatal CA models in newborn lambs revealed enhanced brain ATP production by an intravenous infusion of sodium pyruvate post-CA [13]. Sharma et al. [15, 16] used a mongrel dog CA model and became the first to report the benefit of intravenous administration of sodium pyruvate during cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) in preventing neurological deficit in PCAS. Although this area is well studied, no previous study has investigated the association between a pyruvate-induced increase in energy metabolism and an increase in extracellular ATP levels with potentially harmful consequences due to an exaggerated “danger response.”

Blood sampling is a minimally invasive procedure that is applicable to most clinical settings, and it is capable of providing important aspects of extracellular purinergic signaling. Blood ATP levels can parallel extracellular ATP concentrations and average the information from the multiple organs. Since ATP is a vital signaling molecule in the circulating blood, blood ATP levels have been studied extensively in the field of purinergic signaling [17]. Therefore, in this study, we investigated the effect of intravenous use of sodium pyruvate on a systemic change in plasma ATP levels post-CA.

Materials and methods

The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees (IACUC) of the Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research approved the study protocol. All experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations, and this study is reported in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines. The method of euthanasia is consistent with the AVMA Guidelines for the Euthanasia of Animals. The data supporting this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. One investigator performed all surgical procedures; therefore, we did not apply blinding procedures in this study.

Animal preparation

We added some modifications to the procedures that we previously described [18, 19]. Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (400–500 g, Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA, USA) underwent general anesthesia with 4% isoflurane (Isosthesia, Butler-Schein AHS, Dublin, OH, USA) and were intubated by a 14-gauge plastic catheter (Surflo, Terumo Medical Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Rats underwent volume control mechanical ventilation (Ventilator Model 683, Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA, USA). We fixed the minute ventilation volume (MVV) at 180 mL/min and set the respiratory rate at 45 breaths per minute. We did not change MVV or respiratory rate during the experiments. Positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) was set at 2 cm. Carbon dioxide (CO2) was continuously measured inline in the exhalation branch of the ventilator circuit by using a CO2 gas monitor (OLG-2800, Nihon Kohden Corp., Tokyo, Japan) with a CO2 sensor (TG-970P, Nihon Kohden Corp., Tokyo, Japan) and an airway adapter (YG-211T, Nihon Kohden Corp., Tokyo, Japan). The CO2 sensor was a main-stream capnometer, which did not require any sampling volume of the gas. The fraction of expired CO2 (FECO2) was monitored in real-time. The core temperature (T-type thermocouple probes, ADInstruments, Colorado Springs, CO, USA) was monitored in the esophagus and maintained at 36.5 ± 1.0 °C. We placed a sterile polyethylene-50 catheter in the left femoral artery (FA) for continuous arterial pressure monitoring (MLT844, ADInstruments; Bridge Amplifier ML221, ADInstruments, Colorado Springs, CO, USA) and another catheter cannulated in the left femoral vein, which was advanced to the inferior vena cava for intravenous drug administration.

Cardiac arrest, resuscitation, and drug administration

After instrumentation, neuromuscular blockade was achieved by slow intravenous administration of 2 mg/kg of vecuronium bromide (Hospira, Lake Forest, IL, USA), and asphyxia was induced by turning off mechanical ventilation. The depth of anesthesia was verified by confirming the absence of toe-pinch reactions before administering vecuronium. CA normally occurred 2 to 4 min after asphyxia started, and our pilot study validated the adequacy of anesthesia during the time needed to induce CA. The CA group received chest compression CPR after an untreated 10 min of asphyxia. After the 10-min asphyxia, mechanical ventilation was restarted at a fraction of inspired oxygen (FIO2) of 1.0, and manual chest compression CPR was delivered simultaneously. Chest compressions were performed with 2 fingers over the sternum at a rate of 260 to 300 per minute. At 30 s after beginning of CPR, a 20 μg/kg bolus of epinephrine was given to rats through the venous catheter. Following return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC), defined as mean arterial pressure > 60 mmHg, CPR was discontinued. If ROSC did not occur by 5 min of CPR, resuscitation was terminated. FIO2 was switched back to 0.3 at 10 min after the initiation of CPR. Transthoracic echocardiography was non-invasively performed by using 12-4 MHz probe (S12-4 sector array transducer, Philips, Amsterdam, Netherlands) to evaluate the contraction of the heart at baseline and 30 min after CPR. All echocardiography measurements were averaged over three cardiac cycles.

Experimental groups

This study included the following experimental groups to validate the effects of interventions and to test our hypothesis. The groups were divided into two groups: with or without CA and CPR. Rats in the sham group (control) did not receive either asphyxia or CPR; however, the same surgical procedures were performed in this group. In this study, we collected samples from naïve rats at the same time when the test animals were euthanized. This is to validate and obtain the reference of our biological assays. The non-CA groups are the following: 1a, naïve group with anesthesia only to harvest the tissue samples; 1b, sham-surgery group with an injection of vehicle solution and this group includes surgical procedures such as anesthesia, mechanical ventilation, and cannulations, to obtain time-control samples; 1c, sham-surgery group with an injection of test drugs such as rotenone or pyruvate, and this group includes the aforementioned surgical procedures. The CA groups are the following: 2a, rats with a continuous infusion of vehicle solution that received the aforementioned CA/CPR procedures; 2b, rats with a continuous infusion of pyruvate.

In this study, we administered a mitochondrial specific substrate, pyruvate, and a mitochondrial complex I-specific inhibitor, rotenone, to the animals [20]. In the sham-surgery group, sodium pyruvate (P2256, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was intravenously administered at a bolus dose of 600 mg/kg, and rotenone (R8875, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was given continuously at 0.5 mg/kg/h. The vehicle of sodium pyruvate and rotenone was normal saline and 10% ethanol, respectively. In the CA group, sodium pyruvate was given at a bolus dose of 500 mg/kg immediately after ROSC, and the bolus injection was followed by a continuous infusion at 1000 mg/kg/h. The continuous infusion was discontinued at 30 min after ROSC, and therefore, a total of sodium pyruvate administered to a CA rat was 1000 mg/kg within the first 30 min of resuscitation.

Indirect calorimetry

Volumetric oxygen consumption (VO2) and carbon dioxide generation (VCO2) measurements attached to the mechanical ventilation circuit were performed as described previously [21]. We used a photoluminescence-quenching sensor (FOXY AL300 Oxygen Sensor Probe, Ocean Optics, Dunedin, FL, USA) and a fluorometer (NEOFOX-GT, Ocean Optics, Dunedin, FL, USA) to measure the concentration of oxygen gas and performed 2-point calibration for the O2 sensor by medical air (20.9% O2 balanced with Nitrogen) and medical O2 (100% O2, General Welding Supply Corp., Westbury, NY, USA) before each experiment. The CO2 sensor was calibrated with medical air (0% CO2) and industrial CO2 (10.4% CO2 balanced with Nitrogen, General Welding Supply Corp., Westbury, NY, USA). We measured gas humidity inline with a hygrometer (TFH 620, Ebro, Ingolstadt, Germany). Both calibrations occurred at 0% humidity. A temperature probe (T-type thermocouple probes, ADInstruments Inc., CO, USA) and a pressure probe (MLT844, ADInstruments; Bridge Amplifier ML221, ADInstruments, Colorado Springs, CO, USA) were placed inline. In addition, we monitored the ambient temperature and the pressure to check the condition around the ventilator system (Traceable Workstation Digital Barometer, Fisher Scientific, NH, USA).

We have developed a method for measuring the molecular ratio of inhalation to exhalation [21]. This is the key to calculating VO2. The molecular ratio named R is generally derived from a transformation of the Haldane equation with the assumption that nitrogen is neither produced nor retained by the body, and that no gases are present other than O2, CO2, and nitrogen [22]. Because the denominator includes FIO2 and it goes to zero as FIO2 increases to 1.0, the Haldane equation includes a significant limitation. Therefore, we directly sought R by using our technique [21]. In our previous study, R was not 1.0, and so a minute ventilation volume of inhalation (VI) was not equal to that of exhalation (VE). R was 1.0081 +/− 0.0017 at an FIO2 of 0.3 and 1.0092 +/− 0.0029 at an FIO2 of 1.0. In this current work, we used 1.0081 as R as we applied only FIO2 0.3 to all animals.

Seahorse analysis

Oxygen consumption rate (OCR) in isolated mitochondria from the brain and heart was measured by the Seahorse Bioscience XFp Analyzer (Seahorse Bioscience, Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Instruments and procedures for mitochondria isolation were followed by the manufacturer’s instruction manual. In brief, fresh tissues were rinsed in ice-cold Chappel-Perry Buffer I (CPI) that contained 100 mM KCl, 50 mM MOPS, 1 mM EDTA, and 5 mM MgSO4. Tissue homogenates were gently made by the Potter-Elvehjem homogenizer within the CPI and CPII (1:1) buffers. The CPII Buffer contained an additional 0.5% BSA. Homogenates were centrifuged at 600 g for 10 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant, which contains most of the mitochondria, was then centrifuged at 10,000 g for 10 min at 4 °C to obtain a mitochondria pellet. The mitochondria pellet was resuspended and centrifuged twice more at 10,000 g for 10 min in the CPII and CPI buffers, sequentially. In this process, we included 12.5% Percoll in the CPII buffer for brain-isolated mitochondria to increase the purity of the mitochondrial pellet. The purified mitochondria pellet was finally resuspended in MAS Buffer that contained 70 mM sucrose, 220 mM D-mannitol, 5 mM KH2PO4, 5 mM MgCl2, 2mM HEPES, and 1 mM EGTA. The pH was adjusted to 7.3 for all buffers, and the procedures were completed throughout on ice. The XFp sensor cartridge was hydrated with 200 μL/well and 400 μ L/trough of XF Calibrant buffer and placed overnight in a 37 °C incubator without CO2 prior to the date for mitochondria isolation. The cartridge was prepared just before the assay with MAS plus 0.2% BSA supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamic acid, 2.5 mM L-(-)-malic acid, and 5 mM sodium pyruvate at pH 7.3 and 37 °C. Mitochondria (2-5 μg) were then added and reacted with ADP (5 mM) to measure OCR, oligomycin (3 μM) to inhibit ATP synthesis, FCCP (5 μM) to uncouple oxygen phosphorylation, and rotenone/antimycin A (25 μM) to block electron transport sequentially at various times. OCRs were normalized to the mitochondrial amount as determined by the protein concentration obtained by the bicinchoninic acid assay (Pierce BCA protein assay kit, Thermo Fischer Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

ATP analysis

Heart and brain tissues were extracted from the animals into ice-cold PBS. Samples of tissues were placed into ice-cold 2 N perchloric acid, minced, and then homogenized by using a sonicator (Q55, Qsonica, Newton, CT, USA). The homogenates were incubated for 30 min and then centrifuged at 13,000 g for 2 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant was aliquoted and snap frozen. The samples were later neutralized with 2 N KOH for a final pH of 6.5–8.0 at 4 °C. After the neutralization, precipitates were removed by centrifugation at 13,000 g for 15 min at 4 °C, and an aliquot of the extract was diluted with DI water and assayed for ATP by luciferase luminescence assay (ATPlite, PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA). Blood samples were collected from the animals and centrifuged at 1000 g for 5 min to obtain the plasma. Plasma samples were stored at −80 °C, and an aliquot of the plasma was diluted with DI water and assayed by the luciferase luminescence assay.

Real-time PCR

Heart and brain tissues were collected for mRNA (messenger ribonucleic acid) extraction, followed by cDNA (complementary DNA) synthesis and real-time PCR. Additionally, tissues of control (naive) rats were collected for references of mRNA gene expression. RNA isolation, reverse transcription, and real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, total RNAs were extracted and reverse transcribed using TRIzol Reagent® (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and SuperScript™ IV VILO™ Master Mix with ezDNase™ Enzyme (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), respectively. Real-time PCR was performed using TaqMan™ Fast Advanced Master Mix (Applied Biosystems™, Waltham, MA, USA) on the LightCycler 480 system (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). All primers were purchased from Thermofisher: glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Gapdh, TaqMan Assay ID: Rn01775763_g1) as the control gene for normalization, and interleukin-1 beta (Il1b, Rn00580432_m1), CD39 (Cd39, Rn00574887_m1), and CD73 (Cd73, Rn00665212_m1).

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as means and SD (standard deviation). Differences within groups over the course of the experiment were determined by analysis of variance with repeated measures over time. Within-group testing was accompanied by Dunnett’s post hoc test to compare the values with those at baseline. Unpaired Student’s t test analyzed data for two-group comparisons. Statistical analyses were performed using Prism 9.1.0 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA). We consideredP-value less than 0.05 as statistically significant.

Results

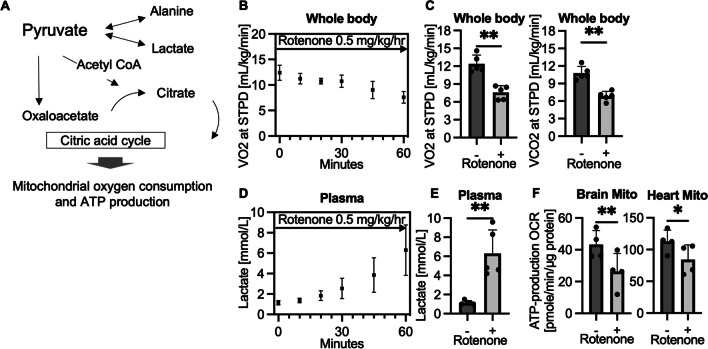

Intravenous administration of mitochondrial specific inhibitor suppresses oxygen and energy metabolism in rats

Figure 1A shows the schema of pyruvate metabolism. Pyruvate can be converted to lactate by LDH (lactate dehydrogenase) and alanine by ALT (alanine aminotransferase) in the cytoplasm and can be also metabolized by citric acid cycle via acetyl-CoA or oxaloacetate path within the mitochondrial matrix. An intravenous infusion of mitochondrial complex I inhibitor, rotenone, decreased VO2 and VCO2 (Fig. 1B and C) and increased lactate formation (Fig. 1D and E) by diverting glycolytically generated pyruvate from mitochondrial oxidation to cytosolic reduction. By subtracting OCR with ATP synthesis inhibitor (oligomycin) from that with ADP, ATP production OCR of mitochondria was calculated. As seen in Fig. 1F, brain and heart mitochondria collected 1 h after the continuous infusion of rotenone had significantly decreased ATP production. The data demonstrates a capability of our system to reproduce mitochondrial specific metabolism in our rat model.

Fig. 1.

Intravenous administration of mitochondrial specific inhibitor (rotenone) suppresses oxygen and energy metabolism in rats. A Schema of pyruvate metabolism (adenosine triphosphate, ATP). B Time course data of volumetric oxygen consumption (VO2) during a continuous infusion of rotenone at 0.5 mg/kg/h (sham-surgery group, n = 5 per group). C VO2 and VCO2, 60 min after a continuous infusion of rotenone as compared to base line values (average 55–60 min; sham-surgery group, n = 5 per group; **P < 0.01). D Time course data of lactate blood levels (sham-surgery group, n = 5 per group). E Blood lactate levels, 60 min after a rotenone infusion compared to base line (average 55–60 min; sham-surgery group, n = 5 per group; **P < 0.01). F ATP production in isolated mitochondria calculated from oxygen consumption rate (OCR) by Seahorse. Mitochondria were isolated from brain and heart tissues 60 min after starting the infusion of rotenone. (sham-surgery group, n = 4 per group; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01). Values are expressed as mean +/− SD

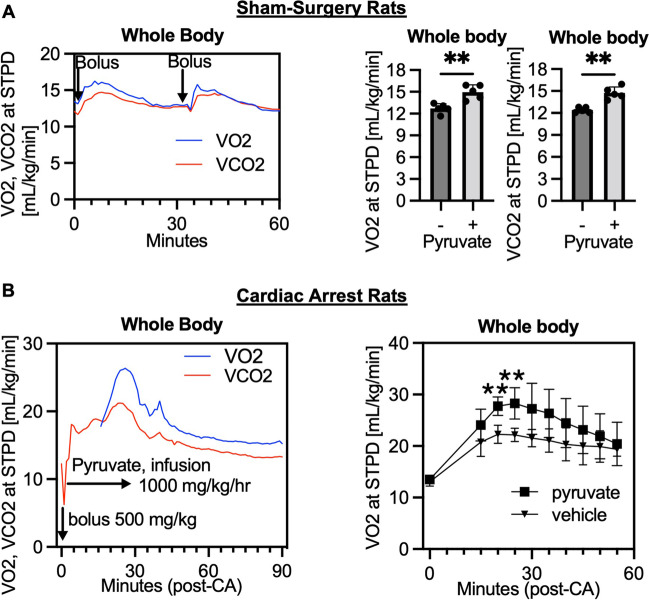

Intravenous administration of pyruvate increases oxygen metabolism in rats after cardiac arrest

An intravenous injection of mitochondrial substrate, pyruvate, increased both VO2 and VCO2 in rats with sham-surgery (Fig. 2A). Peak VO2 and VCO2 were observed between 5 and 10 min after injection. Therefore, tissues were collected at 10 min after the injection for the further biological analysis. We next intravenously administered sodium pyruvate to post-CA rats. A continuous infusion of sodium pyruvate started right after resuscitation increased VO2 and VCO2 that peaked at 20–30 min after resuscitation (Fig. 2B). These results support that intravenous use of sodium pyruvate can enhance mitochondrial oxygen metabolism in both post-CA and non-injured animals.

Fig. 2.

Intravenous administration of mitochondrial substrate (pyruvate) increases oxygen metabolism in rats after cardiac arrest. A Representative time course data of volumetric measurements of oxygen consumption (VO2) and carbon dioxide generation (VCO2) after a bolus injections of sodium pyruvate (n = 1; STPD, standard temperature and pressure, dry). VO2 and VCO2 at 10 min after a bolus injection of pyruvate (600 mg/kg) as compared to baseline values (averaged in 5–10 min; sham-surgery group, n = 5 per group; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01). B Post-cardiac arrest (CA) rats received a bolus injection of pyruvate (500 mg/kg) followed by a continuous infusion (1000 mg/kg/h) for 30 min. Data at time 0 was baseline before CA. Representative time course data of VO2 and VCO2 after CA (n = 1) and VO2 levels compared between the pyruvate and vehicle groups (n = 4 per group; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01). Values are expressed as mean +/− SD

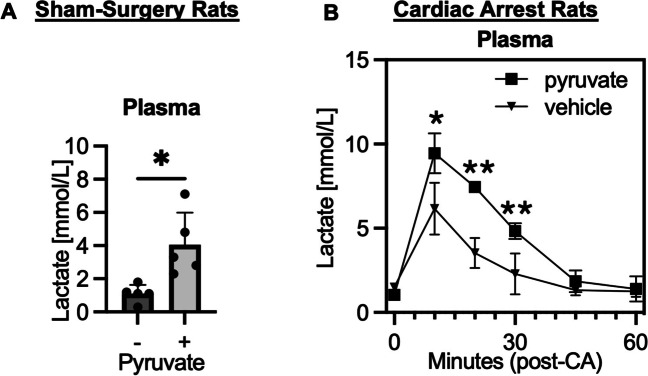

Intravenous administration of pyruvate increases blood lactate levels in rats after cardiac arrest

An intravenous injection of pyruvate increased blood lactate levels in sham-surgery rats (Fig. 3A). Lactate blood levels peaked at 10 min after resuscitation because of a systemic ischemia–reperfusion. We also found that blood lactate levels were increased in the post-CA pyruvate infusion group throughout 30 min after resuscitation, but it was more remarkable at 10 min after resuscitation (Fig. 3B). This indicates an enhanced lactate level owing to a combination of systemic ischemia–reperfusion and pyruvate injection.

Fig. 3.

Intravenous administration of pyruvate increases blood lactate levels in rats after cardiac arrest. A Plasma lactate levels 10 min after a bolus injection of pyruvate (600 mg/kg) as compared to baseline values (sham-surgery group, n = 5 per group; *P < 0.05). B Post-CA rats received a bolus injection of pyruvate (500 mg/kg) followed by a continuous infusion (1000 mg/kg/h) for 30 min. Data at time 0 was baseline before CA. Plasma lactate levels compared between the pyruvate and vehicle groups (n = 4 per group; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01). Values are expressed as mean +/− SD

Cardiac arrest increases blood ATP levels over time, but intravenous administration of pyruvate does not increase plasma ATP levels

Figure 4 demonstrates the dynamic change of eATP and purinergic signaling post-CA. CA was induced by 10 min of asphyxia, and it was followed by chest compression CPR and resuscitation. Plasma ATP levels increased over time and became more remarkable at 60 min after resuscitation (Fig. 4A). The plasma ATP levels before CA were 67 ± 11 nM, and those at 2 h after resuscitation were 227 ± 103 nM. We next tested the effect of intravenous administration of pyruvate on blood ATP levels in the sham-surgery and post-CA rats. Based on the timing of peak VO2, blood samples were collected 10 min and 30 min after injection, respectively (Fig. 4B). We compared the effects of pyruvate between the groups and no changes in blood ATP levels were identified regardless of a CA status. The effects of pyruvate on tissue ATP levels were also evaluated at the same timing after injection. Tissue ATP levels were significantly enhanced in the brain without post-CA injury, but we could not identify a change in heart ATP levels in the sham-surgery or the post-CA group (Fig. 4C and D).

Fig. 4.

Cardiac arrest increases blood ATP levels over time but intravenous administration of pyruvate does not increase plasma ATP levels. A Time course data of plasma ATP levels after CA (Luciferase assay, n = 8 per group; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01). B ATP levels in plasma after pyruvate or vehicle injection compared between the non-injured (sham-surgery) and injured (post-CA) rats. (n = 6–7 per group; **P < 0.01). C ATP levels in brain and heart tissues sampled 10 min after a pyruvate (600 mg/kg) injection as compared to those in naïve rats (n = 4 per group; *P < 0.05). D ATP levels in tissues after CA collected at 30 min after a pyruvate infusion. Post-CA rats received either pyruvate or vehicle injection (n = 4 per group). Values are expressed as mean +/− SD

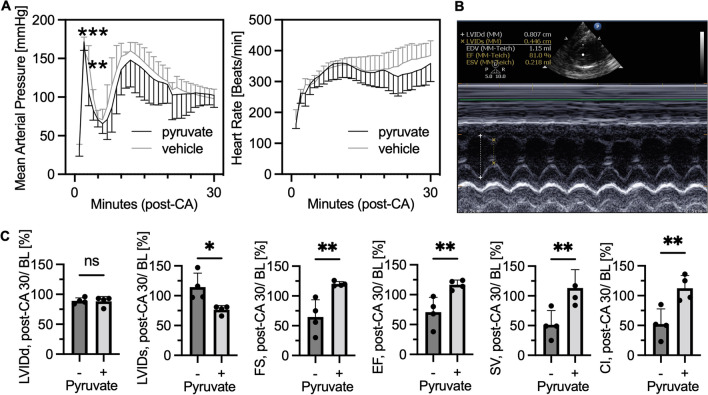

Intravenous infusion of pyruvate after cardiac arrest improves cardiac contractility

Pyruvate’s inotropic (contractility) and lusitropic (relaxation) properties have been demonstrated in the heart ex vivo models [11]. However, few studies have focused on the effect of pyruvate on cardiac contractility after CA. We measured cardiac function using non-invasive echocardiography. Figure 5A shows the time-course hemodynamic data of our post-CA rats. The intravenous administration of sodium pyruvate decreased mean arterial pressure after its bolus injection. However, there were no significant differences in either arterial pressure or heart rates throughout 30 min after resuscitation (Fig. 5B). Figure 5C shows the results of the echocardiogram measured at 30 min after resuscitation standardized by baseline values measured at baseline (pre-CA). This data demonstrates that the pyruvate injection decreased end-systolic left ventricular internal diameter (LVID) but did not change diastolic LVID, resulting in increased fractional shortening (FS), ejection fraction, stroke volume, and cardiac index 30 min after resuscitation. FS was significantly decreased 30 min after CA as compared to the baseline values (65 ± 29%) and significantly improved by pyruvate (120 ± 4%, P < 0.01).

Fig. 5.

Intravenous administration of pyruvate after cardiac arrest improves cardiac contractility. Post-cardiac arrest (CA) rats received a bolus injection of pyruvate followed by a continuous infusion for 30 min. Echocardiogram was performed before CA as baseline (BL) and at 30 min after resuscitation. A Mean arterial pressure and heart rate compared between the groups (n = 8 per group; **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). B Representative snapshot picture of echocardiogram in our rat model. C Results of echocardiogram. LVIDd indicates diastolic left ventricular internal diameter; LVIDs, end-systolic LVID; FS, fractional shortening; EF, ejection fraction; SV, stroke volume; and CI, cardiac index. All data are calculated as percentage of values at post-CA 30 min divided by those at BL. (n = 4 per group; * P < 0.05, **P < 0.01). Values are expressed as mean +/− SD

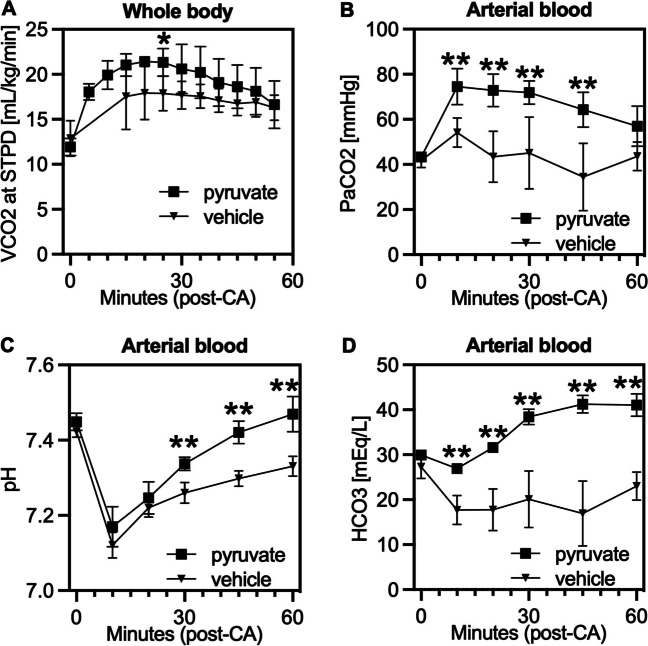

Pyruvate intravenous infusion normalizes blood pH after cardiac arrest

Sodium pyruvate is considered a metabolic basis buffer for acidosis. Therefore, we tested the effect of pyruvate intravenous infusion as a therapeutic metabolic buffer for post-CA acidosis. We measured both VCO2 and blood PaCO2 in post-CA rats and compared those between the pyruvate and vehicle groups (Fig. 6A and B). There were significant increases in VCO2, PaCO2, and HCO3 due to the continuous infusion of sodium pyruvate after resuscitation. As a result, blood pH was normalized earlier in the pyruvate injection group as compared to the vehicle group (Fig. 6C). Effects were seen as early as 10 min after starting the infusion in the form of increases in blood PaCO2 and HCO3 (Fig. 6B and D). These results may indicate that the effect of sodium pyruvate as a metabolic buffer is associated with an increase in oxygen metabolism and CO2 production within the citric acid cycle of mitochondria.

Fig. 6.

Intravenous administration of sodium pyruvate induces carbon dioxide generation and attenuates acidosis after cardiac arrest. Post-CA rats received a bolus injection of pyruvate (500 mg/kg) at resuscitation followed by a continuous infusion. A VCO2, B, C, D, blood gas analysis of PaCO2, pH, and HCO3, respectively. Time 0 was at baseline before CA, and bloods were otherwise collected after resuscitation, and the values were compared between the pyruvate and vehicle injection groups (n = 4 per group; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01). Values are expressed as mean +/− SD

Cardiac arrest induces purinergic signaling in tissues

Responding to the systemic ischemia–reperfusion injury and elevated blood ATP levels, Cd39 and Cd73 gene expressions were increased in the brain 2 h after resuscitation (Fig. 7A). The gene expression of inflammatory marker Il1b was also elevated. We also measured Cd39 and Cd73 gene expressions at a different timing and in other tissues, e.g., the heart. Although all tissue samples showed high mRNA expression following resuscitation, the brain showed a significant increase at 2 h but not at 72 h. In contrast, the heart showed significant increases in expression at 72 h but not at 2 h (Fig. 7B). These data suggest that CA increases ATP levels in the blood and induces Cd39/Cd73 gene expression in the brain and heart but not simultaneously.

Fig. 7.

Cardiac arrest induces purinergic signaling in the brain. A PCR assays for RNA expression of ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase 1 (Cd39), ecto-5′-nucleotidase (Cd73), and IL-1β (Il1b). Brain tissues were collected from rats at 2 h after CA and resuscitation and those from naïve rats. B Cd39/Cd73 expression in the heart at 72 h after CA. (n = 8–10 per group; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01). Values are expressed as mean +/− SD

Discussion

The therapeutic potential of pyruvate in PCAS has been discussed extensively [13, 15, 16]; however, its association with systemic eATP levels has remained poorly understood. As blood ATP is a clinically relevant indicator of in vivo eATP, we were able to investigate the effect of intravenous infusion of sodium pyruvate on eATP levels post-CA. The primary findings in the present study are that the intravenous infusion of sodium pyruvate enhanced post-CA systemic oxygen metabolism and tissue energetic status, as indicated by increases in VO2, but did not affect plasma ATP levels after CA.

Indirect calorimetry enables a real-time and non-invasive measurement of oxygen and energy metabolism, e.g., VO2, by measuring gas concentrations in inhalation and exhalation. We developed a new method for measuring the molecular ratio of inhalation to exhalation that is critical when seeking accurate VO2 [21]. There is an underlying basic question: is the molecular ratio 1.0 and is VI equal to VE? The answer is likely “no,” and VE seems smaller than VI. The adequacy of the Haldane transformation has been discussed over several decades [22, 23]. The Haldane transformation is derived from the assumption that the volume of N2 inspired is equal to that expired, and the following calculation is made:

| 1 |

which is transformed to:

| 2 |

where FEN2 is fraction of expired N2; FIN2, fraction of inspired N2; FEO2, fraction of expired O2; and FECO2, fraction of expired CO2. Failure to account for the respiratory exchange ratio and assuming that VI is equal to VE has been cautioned [24]. The exchange ratio of O2 (FIO2 minus FEO2) is generally 0.050, while FECO2 is lower, and it is normally 0.040 to 0.045. At room air (FIO2 0.209), therefore, VI/VE is expected to be 1.006 to 1.013 when the Haldane transformation is applied. Notably, we measured R (VI/VE), which ranged within the numbers calculated by the Haldane transformation at room air [21]. If R is assumed to be 1.000, VO2 can be erroneously reported with lower numbers and yield an error greater than 5%. Even though the conservation of N2 has been questioned [22, 23], the adequacy of the Haldane transformation has been validated, and it supports the validity of R 1.008 that we used in the present study.

Karlsson et al. [25] showed changes in oxygen metabolism as indicated by a decrease in VO2 by intravenous infusion of mitochondrial complex I inhibitor, rotenone, in their swine model. They used a commercial model of indirect calorimetry and demonstrated that a continuous infusion of rotenone (0.25–0.50 mg/kg/h) decreased VO2 and increased blood lactate levels. Our rodent model revealed the same phenotypic patterns, and additionally, we demonstrated a suppression of mitochondrial energy metabolism indicated by a decrease in ATP production OCR in isolated mitochondria from the brain and heart. The data, in conjunction with those obtained from our highly fidelity, indirect calorimetry method for the rodent model, showcase a success in measuring systemic changes of oxygen metabolism that is directly linked with the mitochondrial energy status in tissues.

Our rodent VO2 data indicated that the enhanced oxygen metabolism by an intravenous injection of sodium pyruvate can be seen approximately 10 min after injection. Sodium pyruvate is a cell-membrane permeable mitochondrial substrate, and it can enhance mitochondrial ATP production [20]. Pyruvate-induced enhancement in oxygen and energy metabolism in animal models has been reported for the last 50 years. Bertram et al. [12] showed those effects in early days with their dog model. Sodium pyruvate injection (600 mg/kg) increased both VO2 and VCO2. The blood concentration of pyruvate peaked (~ 10 mM) within a few minutes, and VO2 peaked within 20 min after injection. Our results in rats were well inline with those previous findings.

In an effort to obtain therapeutic effects with pyruvate in various diseases [11, 13, 14, 16, 26], a continuous infusion model has been developed. Mongan et al. [14] infused sodium pyruvate at a rate of 500 mg/kg/h to attain arterial pyruvate levels of 5 mM and showed improved cerebral metabolism in the swine hemorrhagic shock model. Sharma et al. [15, 16] were the pioneer group tested for the effect of a continuous infusion of sodium pyruvate on neurological recovery in the dog post-CA model. They infused sodium pyruvate at a rate of 825 mg/kg/h with a goal to achieve stable arterial concentrations of ~3.5 mM for the first hour of resuscitation. The latest post-CA study by Kumar et al. [13] used a loading dose of pyruvate at 100 mg/kg at resuscitation followed by a continuous infusion at 600 mg/kg/h for the first 1.5 h of resuscitation. In the present study, we used a loading dose of 500 mg/kg at resuscitation followed by 1000 mg/kg/h for the first 0.5 h to maximize the effect of enhanced oxygen and energy metabolism in post-CA rats. With our rodent model, as similar to the Kumar report, we identified an increase in energy metabolism indicated by elevated ATP levels in the brain but not in the heart. The negative finding is inferred that it may be due to a technical difficulty of measuring ATP molecules during the assay process, but it can be also interpreted as a change in free energy from ATP hydrolysis products such as ADP and orthophosphate. Because intracellular ADP concentration is far below that of ATP, a small change in ADP concentration impacts the free energy that may alter an organ function. This may be even more remarkable in highly metabolic conditions because it may increase both ATP production and consumption. This can include highly metabolic organs such as the heart and statuses such as post-CA injury. Indeed, our echocardiogram data showed that the cardiac contractility increased after pyruvate infusion, and post-CA injury alone increased VO2 as compared to the baseline, which should support increases in the intracellular energy status. Therefore, the lack of information on ATP hydrolysis products is one of the major limitations of our study that must be further addressed in the next step.

Mammalian cells contain high concentrations of intracellular ATP (5–8 mM), which are maintained by mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation. Several mechanisms of eATP release from the intracellular space have been identified, including pannexin-hemichannel-dependent ATP release, during cell stress such as ischemia [7]. Under physiological conditions, eATP concentration is 10–100 nM but rapidly increases to 1–50 μM in response to hypoxia and tissue injury, which induces CD39/CD73 expression via P2 receptors [8, 10]. Conversely, eATP hydrolysis by CD39/CD73 generates adenosine [7, 8], which attenuates ischemic injury and inflammation by binding to P1 receptors such as A2a receptors [8, 27]. However, the underlying post-CA pathophysiology and eATP and/or adenosine correlation have not yet been elucidated. Since blood ATP can parallel tissue eATP, its measurement is crucial to understand purinergic signaling. Therefore, we measured both plasma ATP levels and tissue CD39/CD73 expressions in our rat model. Our data supports an expression of in vivo purinergic signaling induced by post-CA injury as there was an increase in tissue Cd39/Cd73 gene expression associated with elevated plasma ATP levels. However, Cd39/Cd73 expression patterns differ between the brain and heart, suggesting that local ectonucleotidase expression patterns do not necessarily correlate with the plasma ATP levels that average the information from these organs.

A plasma ATP assay with the luciferin-luciferase reaction was well established [17]. In a dog model, Gorman and his group [28] reported that plasma ATP concentrations were 25–50 nM. Gorman et al. [17] also found that human plasma ATP levels were reportedly ~2000 nM with the luciferase assay but a careful sample handling to eliminate red blood cell hemolysis and an EDTA-based stabilizing buffer could attenuate the numbers to 40–70 nM (without correction by hemolysis levels). In the present study, we used the luciferin-luciferase assay, and the ATP level of baseline samples (before CA) was 67 ± 11 nM, increasing significantly to 227 ± 103 nM 2 h after resuscitation. Our data indicates that CA and resuscitation, a systemic ischemia–reperfusion injury, elevate eATP levels over time in vivo. Sumi et al. [29] measured plasma ATP levels from patients after CA and showed those were approximately 200 nM and significantly higher than healthy volunteers (< 50 nM). They also suggested that a higher plasma ATP level was associated with the poor patient’s outcome. However, our work firstly demonstrates the time course of the uptrend in eATP levels in post-CA rats. Collectively, these data imply that plasma ATP levels may be linked to the important pathology of post-CA injury.

Purinergic signaling is a new field of study in ischemia–reperfusion injury [9], and understanding this novel pathway is of paramount importance to improve survival from CA. Purine nucleotide, ATP, is a universal currency for intracellular energy transfer. However, when purines are released from ischemic cells into the extracellular space, they act as death-signaling molecules. Extracellular ATP can activate purinergic (P2X and P2Y) receptors, causing cell injury and hyperinflammation, which leads to cell death and organ dysfunction [7, 8]. However, eATP can also be sequentially converted to adenosine by the cell-surface enzymes such as CD39 and CD73. CD39 and CD73 convert eATP into a diphosphate or monophosphate and subsequently to adenosine. When adenosine binds to purinergic (P1: A1, A2A, A2B, and A3) receptors, adenosine exerts cytoprotective and anti-inflammatory effects [7, 8]. In fact, Cd39 or Cd73 gene deletion leads to elevated eATP levels and lower adenosine levels, increasing susceptibility to pathologic inflammation and cell death [7]. Collectively, CD39/CD73 might play an important role in reperfusion–purinergic pathways during CA and resuscitation.

The RNA expressions of Cd39 and Cd73 in our rat CA model were highly expressed in the brain and heart after CA. The present study is highlighted by the clear evidence of expressed purinergic signaling (eATP, CD39, and CD73) in PCAS. Ryzhov et al. measured CD39/CD73 expression in leukocytes from patients after CA [30] and found that CD39 expression was high and peaked at 6 and 12 h after resuscitation. However, a mechanistic conclusion cannot be drawn owing to several limitations, such as small sample numbers (n = 19 survivors, n = 29 non-survivors), missing values (up to 48%), and mixed characteristics of patients with or without therapeutic temperature management. Our data supports the pathological importance of CD39 and CD73 in crucial organs such as the brain and heart.

Although a therapeutic effect of pyruvate in PCAS has been investigated [13, 15, 16], there has been some debate on whether a potential increase in death-signaling eATP can paradoxically deteriorate the cell-death cascades in PCAS. We monitored VO2 and collected plasma samples at the time of peak energy status, but a systemic administration of pyruvate did not change plasma ATP levels in either sham-surgery or post-CA rats. Thus, it can be inferred that the intravenous administration of pyruvate enhances the intracellular mitochondrial ATP production in tissues but does not contribute to releasing intracellular ATP to the extracellular space. This suggests that the exogenous pyruvate only affects viable cells in which ATP cell-membrane transporters are still functional rather than apoptotic or dead cells that uncontrollably release intracellular ATP.

Sodium pyruvate, when used in vivo, works as a metabolic base buffer that can correct an intracellular acidosis [26]. Our data showed that pyruvate contributed to earlier correction of blood pH after CA in conjunction with elevated lactate, HCO3, PaCO2, and VCO2. Pyruvate, when metabolized to lactate by lactate dehydrogenase, consumes one proton from the cytosolic hydrogen pool. Moreover, when pyruvate is metabolized by the TCA cycle in mitochondria, it consumes one proton while producing CO2 and ATP. The data in our rat model is strongly supported by the current understanding of the physiology and biochemistry of pyruvate metabolism. In addition, the mechanism by which pyruvate crosses the cellular membrane, gradient-coupled cotransport with a hydrogen ion mediated by monocarboxylate transporters [31], may contribute to a reduction of hydrogen ions from the extracellular space and improve post-CA acidemia. Therefore, we confidently support the therapeutic effect of pyruvate for correcting acidosis in PCAS.

In conclusion, our findings reveal a method of increasing intracellular ATP production by using an exogenous mitochondrial substrate, pyruvate, to improve oxygen metabolism indicated by elevated VO2 in post-CA rats. Additionally, pyruvate corrects intracellular acidosis in PCAS by consuming intracellular protons, which are indicated by elevated VCO2 and plasma lactate levels. In the present study, PCAS is characterized by increased purinergic signaling that can be non-invasively monitored by plasma ATP levels, and pyruvate can be potentially therapeutic without exacerbating eATP death-signaling. However, this study does not establish the role of CD39 and/or CD73 in PCAS or demonstrate whether they protect the cells from the eATP death-signaling after CA. Future studies targeted at defining the role of CD39/CD73 and concomitant eATP-P2 receptor activation on post-CA cell death mechanisms will aid in the translation of our findings into improved survival from CA and bolster the potential of pyruvate as a metabolic drug for PCAS.

Koichiro Shinozaki

received his PhD from the Chiba University Graduate School of Medicine, Japan. He is an emergency and critical care physician, who has the experience working in both Japan and USA. He worked at the Department of Emergency Medicine at the Zucker School of Medicine and the Institute of Molecular Medicine at the Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research, Northwell, in New York, USA. He moved back to Japan in 2023 and currently serves as the Professor and Chair of the Department of Emergency Medicine, Kindai University Faculty of Medicine, Osaka, Japan. He extended his research interests from mitochondrial physiology to purinergic signaling in the field of resuscitation science.

Author contribution

K. Shinozaki has full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. K. Shinozaki and V. Wong contributed equally to this work. K. Shinozaki, S.C. Robson, B. Diamond, H. Nandurkar, and L.B. Becker contributed to the design and conception; K. Shinozaki, V. Wong, T. Aoki, and Y. Endo performed acquisition of data; K. Shinozaki and V. Wong analyzed data; all authors made interpretations of data. All authors added intellectual content of revisions to the paper and gave full approval of the version to be published.

Funding

Institutional internal funding from the Feinstein Institutes.

Data availability

The data supporting this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Compliance with ethical standards

Ethical approval

The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees (IACUC) of the Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research approved the study protocol. All experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations and this study is reported in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines. The method of euthanasia is consistent with the AVMA Guidelines for the Euthanasia of Animals.

Conflicts of interest

Shinozaki and Becker own intellectual property of metabolic measurement in critically ill patients. Shinozaki has grant/research supported by Nihon Kohden Corp. Becker has grant/research supported by Philips Healthcare, the National Institutes of Health, Nihon Kohden Corp., BeneChill Inc., Zoll Medical Corp, Medtronic Foundation, and patents in the areas of hypothermia induction and perfusion therapies. The other authors have no disclosures.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Koichiro Shinozaki and Vanessa Wong These authors contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Becker LB, Aufderheide TP, Graham R (2015) Strategies to improve survival from cardiac arrest: a report from the institute of medicine. JAMA 314:223–224 10.1001/jama.2015.8454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Merchant RM, Yang L, Becker LB, Berg RA, Nadkarni V, Nichol G, Carr BG, Mitra N, Bradley SM, Abella BS, Groeneveld PW (2011) Incidence of treated cardiac arrest in hospitalized patients in the United States. Crit Care Med 39:2401–2406 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182257459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, Adams RJ, Berry JD, Brown TM, Carnethon MR, Dai S, de Simone G, Ford ES, Fox CS, Fullerton HJ, Gillespie C, Greenlund KJ, Hailpern SM, Heit JA, Ho PM, Howard VJ, Kissela BM et al (2011) Heart disease and stroke statistics--2011 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 123:e18–e209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neumar RW, Eigel B, Callaway CW, Estes NA 3rd, Jollis JG, Kleinman ME, Morrison L, Peberdy MA, Rabinstein A, Rea TD, Sendelbach S (2015) The American Heart Association response to the 2015 Institute of Medicine Report on strategies to improve cardiac arrest survival. Circulation 132:1049–1070 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nolan JP, Neumar RW, Adrie C, Aibiki M, Berg RA, Bottiger BW, Callaway C, Clark RS, Geocadin RG, Jauch EC, Kern KB, Laurent I, Longstreth WT, Merchant RM, Morley P, Morrison LJ, Nadkarni V, Peberdy MA, Rivers EP et al (2008) Post-cardiac arrest syndrome: epidemiology, pathophysiology, treatment, and prognostication: a scientific statement from the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation; the American Heart Association Emergency Cardiovascular Care Committee; the Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; the Council on Cardiopulmonary, Perioperative, and Critical Care; the Council on Clinical Cardiology; the Council on Stroke. Resuscitation 79:350–379 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2008.09.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Callaway CW, Donnino MW, Fink EL, Geocadin RG, Golan E, Kern KB, Leary M, Meurer WJ, Peberdy MA, Thompson TM, Zimmerman JL (2015) Part 8: Post-Cardiac Arrest Care: 2015 American Heart Association guidelines update for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation 132:S465–S482 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eltzschig HK, Sitkovsky MV, Robson SC (2012) Purinergic signaling during inflammation. N Engl J Med 367:2322–2333 10.1056/NEJMra1205750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Allard B, Longhi MS, Robson SC, Stagg J (2017) The ectonucleotidases CD39 and CD73: novel checkpoint inhibitor targets. Immunol Rev 276:121–144 10.1111/imr.12528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eltzschig HK, Eckle T (2011) Ischemia and reperfusion--from mechanism to translation. Nat Med. 17:1391–1401 10.1038/nm.2507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moesta AK, Li XY, Smyth MJ (2020) Targeting CD39 in cancer. Nat Rev Immunol 20:739–755 10.1038/s41577-020-0376-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mallet RT, Olivencia-Yurvati AH, Bünger R (2018) Pyruvate enhancement of cardiac performance: cellular mechanisms and clinical application. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 243:198–210 10.1177/1535370217743919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bertram FW, Wasserman K, Van Kessel AL (1967) Gas exchange following lactate and pyruvate injections. J Appl Physiol 23:190–194 10.1152/jappl.1967.23.2.190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumar VHS, Gugino S, Nielsen L, Chandrasekharan P, Koenigsknecht C, Helman J, Lakshminrusimha S (2020) Protection from systemic pyruvate at resuscitation in newborn lambs with asphyxial cardiac arrest. Physiol Rep 8:e14472 10.14814/phy2.14472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mongan PD, Capacchione J, Fontana JL, West S, Bünger R (2001) Pyruvate improves cerebral metabolism during hemorrhagic shock. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 281:H854–H864 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.281.2.H854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sharma AB, Knott EM, Bi J, Martinez RR, Sun J, Mallet RT (2005) Pyruvate improves cardiac electromechanical and metabolic recovery from cardiopulmonary arrest and resuscitation. Resuscitation 66:71–81 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2004.12.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharma AB, Barlow MA, Yang SH, Simpkins JW, Mallet RT (2008) Pyruvate enhances neurological recovery following cardiopulmonary arrest and resuscitation. Resuscitation 76:108–119 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2007.04.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gorman MW, Feigl EO, Buffington CW (2007) Human plasma ATP concentration. Clin Chem 53:318–325 10.1373/clinchem.2006.076364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shinozaki K, Becker LB, Saeki K, Kim J, Yin T, Da T, Lampe JW (2018) Dissociated oxygen consumption and carbon dioxide production in the post-cardiac arrest rat: a novel metabolic phenotype. J Am Heart Assoc 7:e007721 10.1161/JAHA.117.007721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aoki T, Wong V, Endo Y, Hayashida K, Takegawa R, Okuma Y, Shoaib M, Miyara SJ, Yin T, Becker LB, Shinozaki K (2023) Bio-physiological susceptibility of the brain, heart, and lungs to systemic ischemia reperfusion and hyperoxia-induced injury in post-cardiac arrest rats. Sci Rep 13:3419 10.1038/s41598-023-30120-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang J, Nuebel E, Wisidagama DR, Setoguchi K, Hong JS, Van Horn CM, Imam SS, Vergnes L, Malone CS, Koehler CM, Teitell MA (2012) Measuring energy metabolism in cultured cells, including human pluripotent stem cells and differentiated cells. Nat Protoc 7:1068–1085 10.1038/nprot.2012.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shinozaki K, Okuma Y, Saeki K, Miyara SJ, Aoki T, Molmenti EP, Yin T, Kim J, Lampe JW, Becker LB (2021) A method for measuring the molecular ratio of inhalation to exhalation and effect of inspired oxygen levels on oxygen consumption. Sci Rep 11:12815 10.1038/s41598-021-91246-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilmore JH, Costill DL (1973) Adequacy of the Haldane transformation in the computation of exercise VO2 in man. J Appl Physiol 35:85–89 10.1152/jappl.1973.35.1.85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Herron JM, Saltzman HA, Hills BA, Kylstra JA (1973) Differences between inspired and expired minute volumes of nitrogen in man. J Appl Physiol 35:546–551 10.1152/jappl.1973.35.4.546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Branson RD, Johannigman JA (2004) The measurement of energy expenditure. Nutr Clin Pract 19:622–636 10.1177/0115426504019006622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karlsson M, Ehinger JK, Piel S, Sjovall F, Henriksnas J, Hoglund U, Hansson MJ, Elmer E (2016) Changes in energy metabolism due to acute rotenone-induced mitochondrial complex I dysfunction - an in vivo large animal model. Mitochondrion 31:56–62 10.1016/j.mito.2016.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou FQ (2005) Pyruvate in the correction of intracellular acidosis: a metabolic basis as a novel superior buffer. Am J Nephrol 25:55–63 10.1159/000084141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Müller CE, Jacobson KA (2011) Recent developments in adenosine receptor ligands and their potential as novel drugs. Biochim Biophys Acta 1808:1290–1308 10.1016/j.bbamem.2010.12.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Farias M 3rd, Gorman MW, Savage MV, Feigl EO (2005) Plasma ATP during exercise: possible role in regulation of coronary blood flow. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 288:H1586–H1590 10.1152/ajpheart.00983.2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sumi Y, Ledderose C, Li L, Inoue Y, Okamoto K, Kondo Y, Sueyoshi K, Junger WG, Tanaka H (2019) Plasma adenylate levels are elevated in cardiopulmonary arrest patients and may predict mortality. Shock 51:698–705 10.1097/SHK.0000000000001227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ryzhov S, May T, Dziodzio J, Emery IF, Lucas FL, Leclerc A, McCrum B, Lord C, Eldridge A, Robich MP, Ichinose F, Sawyer DB, Riker R, Seder DB (2019) Number of circulating CD 73-expressing lymphocytes correlates with survival after cardiac arrest. J Am Heart Assoc 8:e010874 10.1161/JAHA.118.010874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pellerin L, Bergersen LH, Halestrap AP, Pierre K (2005) Cellular and subcellular distribution of monocarboxylate transporters in cultured brain cells and in the adult brain. J Neurosci Res 79:55–64 10.1002/jnr.20307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.