Abstract

The understanding of how central metabolism and fermentation pathways regulate antimicrobial susceptibility in the anaerobic pathogen Bacteroides fragilis is still incomplete. Our study reveals that B. fragilis encodes two iron‐dependent, redox‐sensitive regulatory pirin protein genes, pir1 and pir2. The mRNA expression of these genes increases when exposed to oxygen and during growth in iron‐limiting conditions. These proteins, Pir1 and Pir2, influence the production of short‐chain fatty acids and modify the susceptibility to metronidazole and amixicile, a new inhibitor of pyruvate: ferredoxin oxidoreductase in anaerobes. We have demonstrated that Pir1 and Pir2 interact directly with this oxidoreductase, as confirmed by two‐hybrid system assays. Furthermore, structural analysis using AlphaFold2 predicts that Pir1 and Pir2 interact stably with several central metabolism enzymes, including the 2‐ketoglutarate:ferredoxin oxidoreductases Kor1AB and Kor2CDAEBG. We used a series of metabolic mutants and electron transport chain inhibitors to demonstrate the extensive impact of bacterial metabolism on metronidazole and amixicile susceptibility. We also show that amixicile is an effective antimicrobial against B. fragilis in an experimental model of intra‐abdominal infection. Our investigation led to the discovery that the kor2AEBG genes are essential for growth and have dual functions, including the formation of 2‐ketoglutarate via the reverse TCA cycle. However, the metabolic activity that bypasses the function of Kor2AEBG following the addition of phospholipids or fatty acids remains undefined. Overall, our study provides new insights into the central metabolism of B. fragilis and its regulation by pirin proteins, which could be exploited for the development of new narrow‐spectrum antimicrobials in the future.

Keywords: amixicile, anaerobic bacteria, antimicrobial, B. fragilis, metronidazole, pirin‐protein interactions

This study reveals that several enzymes involved in the central metabolism of Bacteroides fragilis are regulated by protein‐protein interactions with pirin proteins. We observed changes in susceptibility to the antimicrobials metronidazole and amixicile in various metabolic mutants. Amixicile, a novel inhibitor that binds to thiamine−diphosphate dependent enzymes, has proven effective in eliminating B. fragilis in a model of intra‐abdominal infection. Furthermore, we identified a 2‐ketoacid: ferredoxin oxidoreductase as essential for growth and proposed its multifunctional roles.

1. INTRODUCTION

Among the anaerobic pathogenic bacteria causing human infections, Bacteroides fragilis is the most frequent isolate, and multi‐drug‐resistant strains are on the rise accounting for most treatment failures (Byun et al., 2019; Hartmeyer et al., 2012; Jasemi et al., 2021; Nagy et al., 2011; Schuetz, 2014; Snydman et al., 2017). Metronidazole (MTZ) remains the antibiotic of choice for the management of infections caused by anaerobes and resistance to MTZ is generally still low, however, resistant strains have been reported in regional survey studies (Alauzet et al., 2019; Hartmeyer et al., 2012; Jasemi et al., 2021; Nagy et al., 2011; Shafquat et al., 2019; Shilnikova & Dmitrieva, 2015). MTZ is a derivative of the 5‐nitroimidazole class of prodrugs requiring [(2 pairs of 2e−) or 4e‐] reductions of the nitro group for activation to produce a reactive radical species accountable for its lethal DNA mutagenic and strand fragmentation activity (Alauzet et al., 2019; Dingsdag & Hunter, 2018; Ghotaslou et al., 2018; Sisson et al., 2000). Therefore, given the continuous increase in B. fragilis multi‐drug resistance (MDR) traits and the steady decrease in the number of new alternative antibiotics, there is a need to find alternative anaerobic therapeutics. In this regard, recent studies have reported on a novel antimicrobial, amixicile (AMIX), that exhibits excellent in vitro and in vivo activity against oral anaerobic bacterial pathogens grown on biofilm or internalized by host cells (Gui et al., 2019; Gui et al., 2020; Gui et al., 2021; Hutcherson et al., 2017; Reed et al., 2018).

Amixicile, a novel second generation of nitazoxanide with improved bioavailability and selectivity (Hoffman, 2020), inhibits the action of thiamine‐diphosphate (ThPP) cofactor in pyruvate: ferredoxin oxidoreductase (PFOR) and related members of the 2‐ketoacid ferredoxin oxidoreductase (KFOR) superfamily found in obligate anaerobic bacteria, anaerobic human intestinal parasites, and in members of the epsilon proteobacteria such as Campylobacter and Helicobacter (Hoffman et al., 2014; Hoffman, 2020; Kennedy et al., 2016; Warren et al., 2012). Unlike MTZ, AMIX and NTZ do not undergo redox electron transfer, they are not mutagenic (Ballard et al., 2011; Hoffman et al., 2007; Warren et al., 2012), and do not exhibit cross‐resistance with MTZ in tested organisms (Hoffman et al., 2007). Also important, AMIX targets are not found in humans, mitochondria or in aerobic and facultative anaerobes which utilize pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) in the catabolism of pyruvate (Hoffman, 2020). Preclinical studies show that AMIX is effective in treating Clostridioides difficile colitis, Helicobacter pylori gastritis and periodontitis in animal models (Gui et al., 2021; Hoffman et al., 2014; Warren et al., 2012). More specifically, AMIX inhibits the growth of the “Red complex” of oral anaerobic pathogens (Gui et al., 2019; Gui et al., 2020; Gui et al., 2021; Hutcherson et al., 2017; Reed et al., 2018) and the anaerobic protozoan Trichomonas vaginalis (Jain et al., 2022). Pharmacokinetic studies indicate that AMIX is efficiently absorbed (bioavailability), does not concentrate in or alter the intestinal microbiota of healthy mice and is eliminated via the renal system (Hoffman et al., 2014). However, very little is known about AMIX activity against B. fragilis.

PFOR is a major metabolic enzyme in the oxidative decarboxylation of the pyruvate pathway in anaerobes and the best‐studied member of the KFOR superfamily (Gibson et al., 2016; Ragsdale, 2003). However, PFOR is not essential for B. fragilis growth in vitro, and though PFOR is a major player in MTZ activation and a target for AMIX activity, the lack of PFOR adds a modest increase in resistance to MTZ (Diniz et al., 2004) and does not abolish susceptibility to AMIX (this study). This indicates that other metabolic pathways containing ThPP‐binding enzymes that catalyze the cleavage or formation of carbon‐carbon bonds of 2‐ketoacids or 2‐hydroxyketones (Gibson et al., 2016; Prajapati et al., 2022) may play important roles in MTZ and AMIX susceptibility. Nearly all ThPP‐dependent enzymes can perform one‐electron redox reaction steps that occur in the 2‐electron process in oxidoreductases, and the low potential (~ −500mV) electrons generated can reductively activate pro‐drugs such as MTZ (Chen et al., 2019; Gibson et al., 2016; Reed et al., 2012).

In addition to PFOR, B. fragilis encodes three other ThPP‐binding KFOR members: two 2‐ketoglutarate:ferredoxin oxidoreductases (KGOR); the kor1AB (BF638R_4321‐4322) and the kor2ABG genes encompassed in the kor2CDABEG putative operon (BF638R_1660‐1655), and the indolepyruvate ferredoxin oxidoreductase, iorAB (BF638R_1606‐1605). B. fragilis Kor1AB and Kor2ABG subunits are orthologs to Magnetococcus marinus MmOGOR, KorAB (Chen et al., 2019), Hydrogenobacter thermophilus HtOGORs, KorAB, and ForDABGE (Yamamoto et al., 2006; Yamamoto et al., 2010; Yun et al., 2001; Yun et al., 2002), KGOR of Thermococcus litoralis α‐ and β‐subunits (Mai and Adams, 1996), and KGOR of Tharnea aromatica KorAB (Dörner & Boll, 2002) which catalyze the reductive carboxylation of succinyl‐CoA to form 2‐ketoglutarate (2‐KG) in the reverse (reductive) TCA cycle. However, there is a paucity of information regarding the contribution of Kor1AB and Kor2CDAEBG in B. fragilis reverse reductive TCA cycle mode.

Interestingly, several studies have demonstrated that B. fragilis has a bifurcated TCA cycle containing the heme‐dependent reductive branch oxaloacetate to succinate pathway, and the heme‐independent citrate/isocitrate to 2‐KG oxidative pathway branch but lacking reductive synthesis of 2‐KG via succinate (Baughn & Malamy, 2002; Baughn & Malamy, 2003; Chen & Wolin, 1981; Harris & Reddy, 1977; Macy et al., 1975; Macy et al., 1978). However, there is strong evidence that B. fragilis and other anaerobic bacteria synthesize 2‐KG from succinate via reductive carboxylation of succinyl‐CoA. Using [1,4‐14C]‐succinate, or D‐[U‐14C]‐glucose it was demonstrated that radiolabeled carbon was incorporated into glutamate via succinate, but not via the citrate/isocitrate pathway (Allison & Robinson, 1970; Allison et al., 1979). In the closely related organism Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron, metabolomic studies monitoring carbon flux with radiolabeled [U‐13C]‐glucose also showed that glutamate and its precursor 2‐KG are synthesized via succinate but not via citrate (Schofield et al., 2018). Assimilation of [U‐13C]‐acetate in B. thetaiotaomicron results in the propagation of labeled citrate, but not to glutamate indicating that 2‐KG is not formed by the oxidative branch (Schofield et al., 2018), though it is assumed to occur in B. fragilis under heme‐limiting conditions (Baughn & Malamy, 2002). Nonetheless, no genetic evidence nor enzymatic activity responsible for the reductive formation of 2‐KG in B. fragilis has been described. In this regard, we have initiated studies to understand the regulation and metabolic role of Kor1AB and Kor2CDAEBG in B. fragilis central metabolism.

Pirins are highly conserved redox‐sensitive, iron‐binding proteins belonging to the functionally diverse cupin protein superfamily. Pirins contribute to the control and modulation of a diverse range of regulatory and metabolic activities in archaea, prokaryotes and eukaryotes. (Agarwal et al., 2009; An et al., 2004; Dunwell, et al., 2000; Dunwell et al., 2001; Dunwell, et al., 2004; Hihara et al., 2004; Lapik & Kaufman, 2003; Orzaez et al., 2001; Pang et al., 2004; Yoshikawa et al., 2004; Wendler et al., 1997). In the bacterium Serratia marcescens, pirin interacts with the pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) E1 subunit and modulates the PDH activity determining the direction of the pyruvate metabolism toward the TCA cycle or the fermentation pathway (Soo et al., 2007). The involvement of pirin in modulating the central metabolism of prokaryotes was also demonstrated in Streptomyces ambofaciens (Talà et al., 2018) and Aliivibrio salmonicida (Hansen et al., 2012). In Acinetobacter baumanii, pirin regulates the expression of adaptative efflux‐mediated antibiotic resistance (Young et al., 2023). In Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron, recombinant pirin exerts immunomodulating actions preventing the induction of pro‐inflammatory interleukins in animal models of Crohn's disease (Delday et al., 2019).

In this study, we show that B. fragili's central metabolism activities are controlled, at least partially, by pirin proteins. Using a series of metabolic mutant strains and electron transport inhibitors, we show that resistance to MTZ involves a complex accumulation of mutations affecting metabolic pathways and electron transfer in energy conservation mechanisms. In addition, we carry out experiments to understand the metabolic role of Kor1AB and Kor2CDAEBG in B. fragilis central metabolism and show evidence that kor2AEBG genes are essential for growth and may play a role in the formation of 2‐KG. Lastly, we demonstrate the novel ThPP‐dependent enzyme cofactor inhibitor AMIX has antimicrobial activity against B. fragilis in an experimental model of intra‐abdominal infection.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Strains and growth conditions

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Bacteroides species Strains were routinely grown on BHIS (brain heart infusion) supplemented with l‐cysteine (1 g/L), hemin (5 mg/L), and NaHCO3 (20 mL of a 10% solution per litre). A chemically defined medium was formulated as follows: KH2PO4 (1.15 g/L); (NH4)2SO4 (0.4 g/L); NaCl (0.9 g/L); l‐methionine (75 mg/L); MgCl2.6H2O (20 mg/L); CaCl2.2H2O (6.6 mg/L); MnCl2.4H2O (1 mg/L); CoCl2.6H2O (1 mg/L); resazurin (1 mg/L); l‐cysteine (1 g/L); hemin (5 mg/L); and d‐glucose (5 g/L) or otherwise stated in the text. The final pH was 6.9. Rifampin (20 μg/mL), gentamicin (100 μg/mL), erythromycin (10 μg/mL), tetracycline (5 μg/mL), cefoxitin (25 μg/ml), 5‐fluor‐2'‐deoxyuridine, FUdR, (200 μg/mL), or anhydrotetracycline, aTC (100 ng/mL) were added to the media when required. E. coli strains were routinely grown on lysogeny broth media with appropriate antibiotics.

Table 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study.

| Strains | Genotype | References |

|---|---|---|

| B. fragilis 638R | clinical isolate, Rifr | Privitera et al. (1979) |

| BER‐2 | 638R ΔfurA::cfxA, Rifr Cfxr | Robertson et al. (2006) |

| BER‐63 | 638R ΔftnA::tetQ, Rifr Tetr | Gauss et al. (2012) |

| BER‐74 | 638R Δbfr::cfxA, Rifr Cfxr | Gauss et al. (2012) |

| BER‐75 | 638R ΔftnA::tetQ Δbfr::cfxA, Rifr Tetr Cfxr | Gauss et al. (2012) |

| BER‐150 | 638R ΔfnrA::tetQ, Rifr Tetr | This study |

| BER‐156 | 638R ΔnrfA::tetQ, Rifr Tetr | Lab strain |

| BER‐164 | 638R Δpir1::tetQ, Rifr Tetr | This study |

| BER‐165 | 638R Δpir2::cfxA, Rifr Cfxr | This study |

| BER‐166 | 638R Δpir1::tetQ Δpir2::cfxA Rifr Tetr Cfxr | This study |

| BER‐173 | BER‐164 carrying pER‐287, pir1 + , Rifr Tetr Ermr | This study |

| BER‐174 | BER‐165 carrying pER‐288, pir2 + , Rifr Cfxr Ermr | This study |

| BER‐175 | BER‐166 carrying pER‐287, pir1 + , Rifr Tetr Cfxr Ermr | This study |

| BER‐176 | BER‐166 carrying pER‐288, pir2 + , Rifr Tetr Cfxr Ermr | This study |

| BER‐183 | 638R Δtdk, Rifr FUdRr | Parker et al. (2022) |

| BER‐231 | 638R ΔPFOR::tetQ, Rifr Tetr | This study |

| BER‐282 | 638R pyc::pFD516, Rifr Ermr | This study |

| BER‐285 | 638R made metronidazole resistant at 2 μg/ml | This study |

| BER‐286 | 638R made metronidazole resistant at 4 μg/ml | This study |

| BER‐287 | 638R made metronidazole resistant at 8 μg/ml | This study |

| BER‐289 | 638R made metronidazole resistant at 16 μg/ml | This study |

| BER‐293 | 638R made metronidazole resistant at 32 μg/ml | This study |

| BER‐294 | 638R Δkor1AB, Rifr | This study |

| BER‐295 | 638R Δkor2AEBG, Rifr | This study |

| BER‐296 | 638R ΔPFOR::tetQ Δkor1AB, Rifr | This study |

| BER‐298 | 638R ΔpoxB, Rifr | This study |

| BER‐299 | 638R ΔPFOR::tetQ ΔpoxB, Rifr | This study |

| BER‐300 | 638R Δkor1AB ΔpoxB, Rifr | This study |

| BER‐301 | 638R ΔPFOR::tetQ Δkor1AB ΔpoxB, Rifr | This study |

| BER‐302 | 638R ΔPFOR::tetQ Δkor2AEBG, Rifr | This study |

| BER‐303 | 638R ΔPFOR::tetQ Δkor1AB Δkor2AEBG, Rifr | This study |

| BER‐308 | 638R ΔcitS Δicd ΔacnA, Rifr | This study |

| BER‐309 | 638R Δkor2AEBG ΔcitS Δicd ΔacnA, Rifr | This study |

| BER‐310 | 638R ΔPFOR::tetQ Δkor2AEBG ΔcitS Δicd ΔacnA, Rifr | This study |

| BER‐311 | 638R ΔPFOR::tetQ Δkor1AB Δkor2AEBG ΔcitS Δicd ΔacnA, Rifr | This study |

| BER‐323 | BER‐183 ΔfnrC Δtdk, Rifr FUdRr | This study |

| IB260 | 638R ΔkatB::tetQ, Rifr Tetr | Rocha et al. (1996) |

| IB263 | 638R hydrogen peroxide resistant, hpr, Rifr | Rocha & Smith (1998) |

| IB274 | 638R ahpCF::pFD516, Rifr Ermr | Rocha & Smith (1999) |

| IB276 | 638R ahpF::pFD516, Rifr Ermr | Rocha & Smith (1999) |

| IB336 | 638R Δdps::tetQ, Rifr Tetr | Rocha & Smith (2004) |

| IB370 | 638R ΔtrxB::cfxA, Rifr Cfxr | Rocha et al. (2007) |

| IB430 | 638R ΔahpC::tetQ, Rifr Tetr | Lab strain |

| IB483 | ADB77 reverted to thyA +, ΔtrxC ΔtrxD::cfxA ΔtrxE ΔtrxF ΔtrxG Rifr Cfxr | Reott et al. (2009) |

| IB500 | IB483 ΔoxyR::tetQ Rifr Cfxr Tetr | Reott et al. (2009) |

| IB542 | IB336 Δbfr::cfxA, Rifr Tetr Cfxr | Betteken et al. (2015) |

| IB567 | IB542 pFD288::bfr + , Rifr Tetr Cfxr Ermr bfr + | Betteken et al. (2015) |

| IB573 | IB542 pFD288::dps + , Rifr Tetr Cfxr Ermr | Betteken et al. (2015) |

| ADB77 | 638R isogenic ΔthyA Rifr Tpr | Baughn & Malamy (2002) |

| ADB247 | ADB77 ΔfrdC247 reverted to thyA +, Rifr | Baughn & Malamy (2002) |

| ADB260 | ADB77 ΔfrdB260 ΔthyA Rifr Tpr | Baughn & Malamy (2002) |

| BER‐274 | ADB77 ΔrelA ΔspoT reverted to thyA +, Rifr | Lab strain |

| BER‐278 | ADB247 carrying pER‐364, frdC + , Rifr Ermr | This study |

| BER‐283 | ADB260 carrying pER‐365, frdB + , ΔthyA Rifr Tpr Ermr | This study |

| B. fragilis BF8 | chromosomal nimB Nir | Haggoud et al. (1994) |

| C. difficile | ATCC 43255 | ATCC |

| P. gingivalis | ATCC 33277 | ATCC |

| Pr. melaninogenica | ATCC 25845 | ATCC |

| E. coli | ||

| DH10B | cloning host strain | Invitrogen |

| HB101::RK231 | HB101 containing RK231, (Kmr) (Tetr) (Strr) | Guiney et al. (1984) |

| S17‐1 λpir | Strain with the RK2 tra genes for conjugative transfer integrated in the chromosome (RP4‐2‐Tc::Mu‐Km::Tn7, pro, res − mod + , Tpr Smr) λpir lysogen. | Simon et al. (1983) |

| XL1‐Blue MRF' | Δ(mcrA)183 Δ(mcrCB‐hsdSMR‐mrr)173 endA1 supE44 thi‐1 recA1 gyrA96 relA1 lac [F' proAB lacI q ZΔM15 Tn5 (Kanr )]. | Stratagene |

|

BacterioMatch II Reporter stain |

Δ(mcrA)183 Δ(mcrCB‐hsdSMR‐mrr)173 endA1 hisB | Stratagene |

| supE44 thi‐1 recA1 gyrA96 relA1 lac [F' lacI q His3 aadA Kan r ] | ||

| Plasmids | ||

| pTRG | BacterioMatch II two‐hybrid system target plasmid, | Stratagene |

| pBT | BacterioMatch II two‐hybrid system bait plasmid, | Stratagene |

| pNBU2‐bla‐ermGb | NBU2 integrase (intN2) based genomic insertion vector derived from pKNOCK‐bla‐ermGb inserts into NBU2 att1 or att2 sites of tRNAser. (Ampr) Ermr | Koropatkin et al. (2008) |

| pNBU2‐bla‐tetQb | NBU2 integrase (intN2) based genomic insertion vector derived from pKNOCK‐bla‐tetQb inserts into NBU2 att1 or att2 sites of tRNAser. (Ampr) Tetr | Martens et al. (2008) |

| pExchange‐tdk | Derivative of pKNOCK‐bla‐ermGb carrying cloned tdk gene for counter‐selection. (Ampr) Ermr | Koropatkin et al. (2008) |

| pFD288 | Bacteroides‐E. coli shuttle vector, oriT, pUC19::pBI143 chimera, (Spr) Ermr | Smith et al. (1995) |

| pFD340 | Bacteroides‐E. coli expression shuttle vector. (Ampr) Ermr | Smith et al. (1992) |

| pFD516 | suicide vector, derived from deletion of pBI143 in | Smith et al. (1995) |

| pLGB36 | Suicide vector for allelic replacement in Bacteroides species including B. fragilis strain 638R, Ermr selection and aTC‐inducible ss‐Bfe3 counterselection. | Ito et al. (2020) |

| pER‐63 | A 2.1 kb BamHI/EcoRI DNA fragment containing cfxA cassette gene was cloned into the BamHI/EcoRI sites of pFD516. (Spr), Ermr. | This study |

| pER‐65 | A 2.4 kb BamHI/SacI DNA fragment containing tetQ gene cassette was cloned into the BamHI/SacI sites of pFD516. (Spr), Tetr. | This study |

| pER‐283 | A 1.9 bp N‐terminal BglII/BamHI and a 1.935 bp SstI C‐terminal DNA fragments flanking BF638R_3039 gene was cloned, respectively, into BamHI and SacI sites of the suicide‐vector pER‐65 to construct Δpir1::tetQ deletion mutant. (Spr). | This study |

| pER‐284 | A 1.240 bp N‐terminal BglII/BamHI and a 1.830 bp EcoRI C‐terminal DNA fragments flanking BF638R_1469 gene was cloned, respectively, into the BamHI and EcoRI sites of the suicide‐vector pER‐63 to construct Δpir2::cfxA deletion mutant (Spr) | This study |

| pER‐287 | An 0.808 kb DNA fragment containing promoterless pir1 gene was cloned into the BamHI/SacI sites of the expression vector pFD340. (Ampr) Ermr | This study |

| pER‐288 | A 0.746 kb kb DNA fragment containing promoterless pir2 gene was cloned into the BamHI/SacI sites of the expression vector pFD340. (Ampr) Ermr | This study |

| pER‐364 | A 0.96 kb DNA fragment containing promoterless frdC gene was cloned into the BamHI/KpnI sites of the expression vector pFD340. (Ampr) Ermr | This study |

| pER‐365 | A 1.040 kb DNA fragment containing promoterless frdB gene was cloned into the BamHI/SacI sites of the expression vector pFD340. (Ampr) Ermr | This study |

| pER‐372 | A 2,461 DNA fragment containing 2,435 bp in‐frame null deletion of kor1AB genes (BF638R_4321‐4322) was cloned into the BamHI/SalI sites of pLGB36 vector. (Ampr) Ermr | This study |

| pER‐373 | A 2,040 DNA fragment containing 2,354 bp in‐frame null deletion of kor2ABG genes (BF638R_1655‐1658) was cloned into the BamHI/XmaI sites of pLGB36 vector. (Ampr) Ermr | This study |

| pER‐375 | A 3,723 DNA fragment containing 1,350 bp in‐frame null deletion of poxB gene (BF638R_3245) was cloned into the BamHI/SalI sites of pLGB36 vector. (Ampr) Ermr | This study |

| pFD1198 | A 1 kb DNA fragment upstream and 1 kb DNA fragment downstream of fnrA gene (BF638R_0432) were clone into the BamHI/SacI and SacI/EcoRI sites of pFD516. A 2.3 TetQ cassette was cloned into the SacI site to replace an internal 700 bp deleted DNA fragment (Spr) Ermr. | This study |

| pFD1245 | An 802 bp insertional inactivation fragment of the pyc gene (BFR638R_1927) cloned into the BamHI/EcoRI sites of pFD516. (Spr) Ermr | This study |

| pFD1277 | A 2,243 bp DNA fragment containing 566 bp in‐frame null deletion of fnrC gene (BF638R_1017) was cloned into the PstI/XbaI sites of pExchange‐tdk vector. (Ampr) Ermr | This study |

| pFD1278 | A 2.002 kb N‐terminal SphI/BamHI and a 1.819 SacI flanking BF638R_3194 gene was cloned, DNA fragments into the SphI/BamHI and SacI sites of the suicide‐vector pER‐65 to construct ΔPFOR::tetQ deletion mutant. (Spr). | This study |

Note: Parenthesis indicates antibiotic resistance expression in E. coli.

Abbreviations: Ampr, ampicillin resistance; ATCC, American type culture collection; Cfxr, cefoxitin resistance; Ermr, erythromycin resistance; FUdRr, 5‐fluor‐2′‐deoxyuridine resistance; Kanr, kanamycin resistance; Nir, 5‐nitroimidazole resistance; Rifr, rifampicin resistance; Spr, spectinomycin resistance; Strr, streptomycin resistance; Tetr, tetracycline resistance; Tpr, trimethoprim resistance

2.1.1. Bacterial two‐hybrid system assay

Screening partial chromosomal library for protein‐protein interactions with Pir1 or Pir2

The chromosomal DNA from B. fragilis 638 R was partially restricted with Sau3AI to obtain fragments with average size within the range of 0.5–5 kb as previously described (Rocha & Smith, 1995). A genomic library was constructed by ligating the partial Sau3AI fragments into the unique BamHI site downstream of the RNAP α‐subunit in the bacterial two‐hybrid system (THS) target plasmid pTRG (BacterioMatch II; Stratagene) and amplified in E. coli XL1‐Blue MRF' strain (Stratagene). The pirin 1, Pir1, (GenBank locus‐tag BF638R_3039) or pirin 2, Pir2, (BF638R_1469) ORFs were amplified with primers described in Table S1 and cloned in‐frame with the Lambda repressor gene (λcl) under the control of the lac‐UV5 promoter in the bait plasmid pBT according to manufacturer's instructions. The new constructs, pBT/Pir1 or pBT/Pir2 were cotransformed with the pTRG/genomic library into the E. coli THS reporter strain and plated on a selective screening medium containing 5 mM 3‐amino‐1,3,4‐triazole (3‐AT). The isolated two‐hybrid system positive transformants were plated on a dual‐selective medium containing 5 mM 3‐AT and 12.5 μg/ml streptomycin for validation as recommended by the manufacturer. The nucleotide sequence of the DNA fragment inserted into the TRG plasmid from each of the selected THS transformants was obtained using the pTRG forward primer and the deduced amino acid sequences were obtained.

Protein‐protein interaction of Pir1 or Pir2 with PFOR and Zn‐ADH

The entire ORF of PFOR and Zn‐ADH were amplified by PCR and cloned in‐frame with the RNA α‐subunit of pTRG plasmid to construct pTRG/PFOR and pTRG/ADH, respectively. The pTRG/PFOR and pBT/Pir1, the pTRG/PFOR and pBT/Pir2, the pTRG/ADH and pBT/Pir1, or the pTRG/ADH and pBT/Pir2 plasmids were cotransformed into the E. coli THS reporter strain, respectively, and selected on nonselective medium, selective medium, and dual‐selective medium exactly as previously described (Robertson et al., 2006).

Prediction of protein‐protein interactions using computational modeling

Structure‐based computational modeling of protein‐protein interactions was used to assess the potential contributions of side‐chain atoms in the interactions of Pir1 and Pir2 with PFOR, Zn‐ADH, and with 140 enzyme subunits of the central metabolism and energy conservation of the TCA cycle, pyruvate metabolism, branched‐chain amino acid aminotransferase (BCAAT), ThPP‐binding enzymes, carboxylases/decarboxylases, oxidoreductases and dehydrogenases. The 3‐dimensional structure of heteromeric protein‐protein interactions was predicted using Alphafold2‐Multimer https://colab.research.google.com/github/sokrypton/ColabFold/blob/main/AlphaFold2.ipynb (Evans et al., 2021; Jumper et al., 2021; Mirdita et al., 2022). Amino acid sequences of Pir1 and Pir2 along with other target enzymes were used as primary inputs for Alphafold2‐Multimer. For models involving the interaction of Pir1 and Pir2 with PFOR, final models were also subjected to 2000 steps of energy minimization using an AMBER force field and in these specific cases, the final energy relaxed models were used for interface analysis. Resulting models were analyzed using the Protein Interaction Z‐Score Assessment (PIZSA) webserver http://cospi.iiserpune.ac.in/pizsa (Roy et al., 2019) using a distance threshold default 4 Å to define interface residues contacts for the potential contributions of side chain atoms in the protein‐protein interactions. A Z‐score threshold ≥1.500 defines a stable association. The interface area (Å2) and the buried surface area (Å2) of the interacting residues were calculated using the Proteins, Interfaces, Structures and Assemblies (PDBePISA) webserver https://www.ebi.ac.uk/msd-srv/prot_int/pistart.html (Krissinel & Henrick, 2007).

HPLC analysis of short‐chain fatty acids

Bacteria were grown to mid‐logarithmic phase (OD550nm to 0.3–0.4) or for 24 h anaerobically in peptone yeast extract basal medium containing 0.5% d‐glucose (PYG) prepared as described previously (Holdeman et al., 1977). Anaerobic mid‐log cultures were split, and one half were exposed to atmospheric air for 1 h or 24 h in an aerobic shaker incubator at 37℃. For iron restriction, 2,2'‐dipyridyl (50 μM) was added to the medium. After pelleting cultures, the clear supernatants were passed through 0.22 μm filters. Samples were analyzed for SCFAs using a Bio‐Rad HPLC organic acid system with AMINEX 87H, 300 × 7 mm column with 5 mM sulfuric acid eluant at 0.6 mL/min, 65℃, with refractive index detector. Uninoculated media were used as blank and the media background was subtracted except for glucose peak. The HPLC analysis was performed at the USDA Agricultural Research Service.

RNA extraction and RT‐PCR analysis

Bacteria were grown in a chemically defined medium supplemented with 100 μM ferrous sulfate or 50 μM 2,2'‐dipyridyl to mid‐logarithmic phase anaerobically and exposed to atmospheric air for 1 h. Total RNA was extracted from bacterial pellet using the hot‐phenol method as described previously (Rocha & Smith, 1997), and cleaned using RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen) according to manufacturer instructions. RNA was DNAse treated using the Ambion DNA‐free protocol (Ambion, Inc.). First‐strand cDNA synthesis was carried out from 1 μL total RNA at 1 μg/μL with random hexamer primers and Superscript III RT kit (Invitrogen Inc.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Real‐time PCR quantification of each pirin mRNA was performed with 1 μL cDNA sample diluted 1:10 and forward and reverse primers described in Table S1. Real‐time PCR efficiencies were performed for each primer set. The 16S rRNA was used as a reference to normalize gene expression to a housekeeping gene. Relative expression values were calculated using the Pfaffl method (Pfaffl, 2001). Fold induction relative to the wild type in anaerobic conditions was determined for each gene using 16S RNA as the reference gene and all results were the average of at least two independent experiments with freshly isolated RNA.

2.2. Antibiotic susceptibility assays

The agar dilution method for minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) determination and the disc inhibition assays were performed with BHI agar (20 mL/plate) containing heme (5 μg/mL). Overnight bacterial cultures in BHIS were diluted in PBS to a density of approximately 0.5 MacFarland scale. Five μL of suspension was applied on plates containing different concentrations of MTZ or AMIX. Disc inhibition was performed by spreading bacterial suspension with a swab. Five μL of 1 mg/mL MTZ solution or 10 μl of 1 mg/mL sterile AMIX in aqueous solution was applied on top of a sterile 6 mm disc paper. Plates were inoculated in duplicate. One set was incubated for 48 h anaerobically at 37℃, and the other set was incubated aerobically at 37℃ for 24 h before anaerobic incubation for 48 h. Thymine (50 μg/mL) and sodium succinate (20 mM) were added to the media when required for growth of the frdB and frdC mutants and their parent strain ADB77, a BF638R ΔthyA isogenic strain (Table 1). The zone of inhibition around the disc was measured in mm. Electron transport system inhibitors (ETS) or redox cycling agents were added to the medium when required. The ETS inhibitors were added to BHI plates at concentrations 2 to 4‐fold lower than the amount needed to cause growth inhibition of B. fragilis 638 R as indicated in the text. The growth inhibition concentrations of ETS are as follows: Closantel, 12.5 μM; acriflavine, 100 μM; 2‐heptyl‐hydroxyquinoline‐N‐oxide (HQNO), 120 μM; antimycin A, >200 μM; rotenone, >200 μM; and 2‐mercaptopyridine‐N‐oxide (2‐MPNO), 50 μM.

2.2.1. Construction of mutant strains

Deletion mutants with an antibiotic cassette replacing the gene internal DNA deleted fragment were constructed using pFD516 as a suicide vector to mobilize mutated DNA fragments from E. coli DH10B into B. fragilis 638 R for recombinant genetic exchange as described previously (Robertson et al., 2006; Rocha & Smith, 2004; Rocha et al., 2007). The forward and reverse primers used to PCR amplify DNA fragments to construct a deleted DNA fragment are shown in Table S1. The construction of null deletion mutants in B. fragilis 638 R was carried out using a pLGB36 suicide vector for allelic replacement as described previously (Ito et al., 2020). Briefly, the pLGB36 constructs in E. coli S17‐1 λpir strain were mobilized to B. fragilis 638R by biparental mating and transconjugants were selected on BHIS plates containing rifampicin (20 μg/ml), gentamycin (100 μg/mL) and erythromycin (10 μg/mL). A colony of erythromycin‐resistant first crossed‐over recombinant strain was grown on 5 mL BHIS containing rifampicin (20 μg/mL), gentamycin (100 μg/mL), and without erythromycin, until OD550 nm of 0.3–0.4. Then, 100 ng/mL aTC was added and the culture was incubated for approximately 2–3 h to induce the ss‐Bfe3 killer protein for counterselection. Ten μL aliquots were removed and spread on four plates of BHIS containing rifampicin (20 μg/mL), gentamycin (100 μg/mL), and aTC (100 ng/mL). After incubation for 3–4 days, colony PCR was performed using forward and reverse primer sets described in Table S1 to identify transconjugants with chromosomal deletion fragments compared to the parent strain. Erythromycin susceptibility was performed to confirm the loss of the suicide vector.

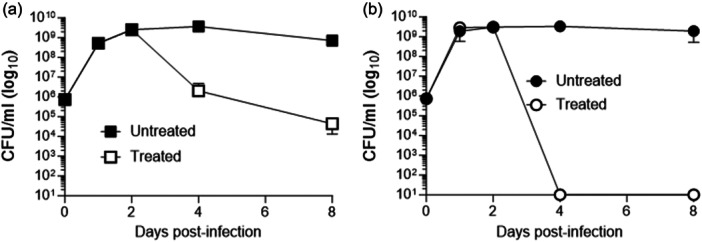

2.2.2. Intra‐abdominal infection

All procedures involving animals followed the guidelines given by the National Research Council's Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Research Council, 2011) and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of East Carolina University. The rat tissue cage model of intra‐peritoneal infection was performed exactly as described previously (Lobo et al., 2013) to test the in vivo efficacy of AMIX against the B. fragilis 638 R strain. Four groups of three Sprague‐Dawley rats were infected with 4 ml of approximately 1 × 105 CFU suspension in PBS into the tissue cage. One group was administered AMIX 20 mg/kg once daily intraperitoneally (IP) from Day 1 through Day 7 postinfection. The second group received AMIX 0.5 mg injected intra‐cage to obtain approximately 20 μg/ml final concentration. This expected intra‐cage concentration corresponds to the AMIX concentration reached in rat serum receiving AMIX 20 mg/kg/day via oral (Hoffman et al., 2014). Intra‐cage injection of AMIX was administered once daily at Day 1 through Day 7 postinfection. The other two groups received saline administered IP or intra‐cage as control. Intra‐cage tissue fluid was aspirated on Day 1, Day 2, Day 4, and Day 8 postinfection, serially diluted, and plated on BHIS. After 3 to 4 days of incubation in an anaerobic chamber at 37℃, colonies were counted and normalized to CFU/mL of tissue cage fluid. The limit of detection was 1 × 101 CFU/mL.

2.3. Statistical analysis

Built‐in statistical analysis in the GraphPad Prism software version 10.2.3 was performed for disc inhibition data using one‐way ANOVA followed by Dunnett and Bonferroni tests for multiple comparisons of the means of each column with the mean of a control column. Only P values with significance in both tests were considered statistically significant. GraphPad Prism reports the summary of p value as follows: p ≥ 0.05, not significant (ns); p = 0.01–0.05, significant (*); p = 0.001–0.01, very significant (**); p = 0.0001–0.01 (***) and p < 0.0001 (****) as extremely significant.

3. RESULTS

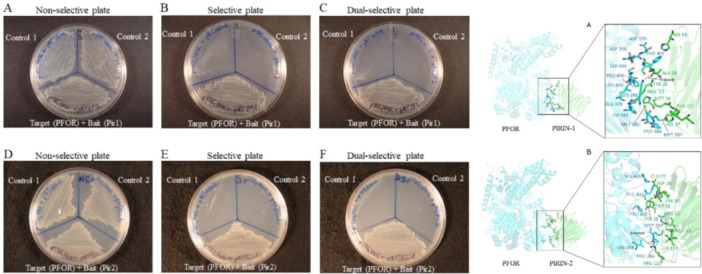

3.1. The expression of pir1 and pir2 genes in response to oxygen and iron limitation

B. fragilis 638R contains two pirin‐like proteins, Pir1 (BF638R_3039) and Pir2 (BF638R_1469). A genome transcription microarray of iron and heme‐regulated genes showed that both pir1 and pir 2 genes are upregulated by iron limitation (NCBI GEO DataSets GSE241210 and GSE241676, unpublished) and following oxygen exposure (Sund et al., 2008). Real‐time RT‐PCR using total RNA confirmed that pir1 and pir2 mRNAs were induced over sixfold and 15‐fold in the presence of oxygen, respectively (Figure 1a), and over fivefold and eightfold under limiting iron conditions compared to the parent strain, respectively (Figure 1b). Furthermore, deletion of the ferric uptake regulator, ΔfurA, did not significantly alter the pir1 or pir2 iron‐regulated expression under high‐iron conditions compared to the parent strain. This indicates that the iron regulation of both pir1 and pir2 mRNA expression is FurA‐independent.

Figure 1.

Fold‐induction of pir1 and pir2 mRNA following (a) oxygen exposure or (b) growth in iron‐limiting conditions. In panel a, the BF638R parent strain was grown to the mid‐logarithmic phase in BHIS and exposed to atmospheric air for 1 h. In panel b, the BF638R parent strain and its isogenic ΔfurA strain were grown to mid‐logarithmic phase in defined medium with protoporphyrin IX supplemented with 100 μM FeSO4 (High Fe) or with 50 μM 2,2’‐dipyridyl (Low Fe). For each condition, RNA was isolated and real‐time RT‐PCR was performed in triplicate. The 16S rRNA gene was used as an internal standard, and the results are expressed as fold induction relative to levels in the control condition. The values are means of fold induction compared to control from two independent experiments. The error bars indicate standard deviations.

A phylogenetic unrooted tree constructed from multiple amino acid alignments showed that the Bacteroides species Pir1 and Pir2 orthologs are grouped into two distinct clusters in a branch divergent from other members of the Bacteroidetes phylum (Supplemental File S1). The multiple amino acid sequence alignment revealed that the N‐terminal domain residues His56, His58, His101, and Glu103 ligands of the iron center of human pirin (Liu et al., 2013; Pang et al., 2004) are conserved in both Pir1 and Pir2 His58, His60, His102, and Glu104, respectively (Supplemental File S2).

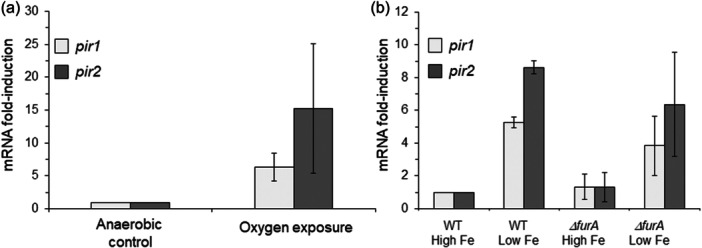

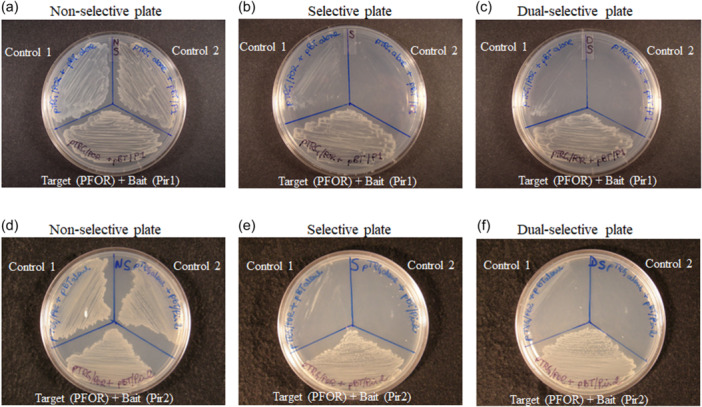

3.2. The two‐hybrid system identifies Pir1 and Pir2 protein‐protein interactions with PFOR and a Zn‐ADH

An E. coli THS assay (BacterioMatch II; Stratagene) was used to screen a B. fragilis 638R partial Sau3AI genomic library cloned in the target plasmid (pTRG) for expression of peptides forming protein‐protein interactions with either Pir1 or Pir2 protein in the bait plasmid (pBT). Over 50,000 co‐transformed colonies were plated on selective THS media, and 12 colonies carrying pTRG/cloned insert interacting with pBT/Pir1 and 11 colonies carrying pTRG/insert interacting with pBT/Pir2 grew on selective media and confirmed by growth on dual‐selective media. This indicated that peptides expressed from the pTRG/insert were positively interacting with Pir1 or Pir2. The deduced amino acid sequence in‐frame with the C‐terminal region of the RNAP α‐subunit of each pTRG/insert interacting with pBT/Pir1 or pBT/Pir2 is shown in Supplemental File S3. Three deduced peptide sequences showed homology to PFOR (BF638R_3194) interacting with Pir1, and six clones showed homology to zinc‐binding alcohol dehydrogenase, Zn‐ADH (BF638R_1292), one interacting with Pir1 and the other five with Pir2. To confirm these findings, the entire PFOR ORF (BF638R_3194) or Zn‐ADH ORF was cloned in‐frame with the RNA‐α subunit into the pTRG vector. The new constructs, pTRG/PFOR and pTRG/ADH were co‐transformed with the pBT/Pir1 or pBT/Pir2 into the two‐hybrid system reporter strain as described above. The THS assays showing protein‐protein interaction of PFOR with Pir1 are shown in Figure 2b,c, and Zn‐ADH with Pir1 or Pir2 is shown in Supplemental File S4. Non‐negligible/slight growth of control 1 was observed in Figure 2b,c.

Figure 2.

Bacterial two‐hybrid system (THS) assay showing protein‐protein interaction of PFOR with Pir1 (panels a, b, and c) and PFOR with Pir2 (panels d, e, and f). E. coli THS reporter strain cotransformed with pBT/Pir1 (bait) and pTRG/PFOR (prey) constructs are shown in panels a, b and c. E. coli THS reporter strain cotransformed with pBT/Pir2 (bait) and pTRG/PFOR (prey) constructs are shown in panels d, e and f. Bacteria were grown on a control nonselective plate (a and d), selective plate (b and e), and dual selective plate (c and f). Self‐activation controls are E. coli THS reporter strain carrying the following constructs: Control 1, empty “bait” (pBT alone) cotransformed with loaded “prey” (pTRG/PFOR) in panels a–f; Control 2, loaded “bait” (pBT/Pir1) cotransformed with empty “prey” (pTRG alone) in panels a, b, and c, or loaded “bait” (pBT/Pir2) cotransformed with empty “prey” (pTRG alone) in panels d, e, and f. In panels 2e and 2f, 7 mM 3‐amino‐1,3,4‐triazole (3‐AT) was used instead of 5 mM 3‐AT used in panels 2b and 2c. See Materials and Methods for details on the bacterial two‐hybrid system assay.

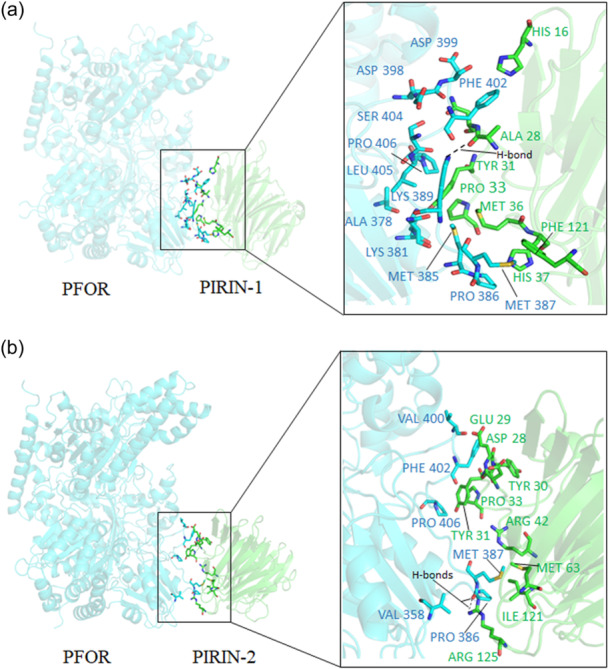

3.3. AlphaFold2‐multimer‐based modeling of protein‐protein interactions between Pir1 or Pir2 with metabolic enzymes

To model protein‐protein interactions of Pir 1 and Pir2 with PFOR, we used AlphaFold2‐Multimer to predict 3D structures of Pir1:PFOR and Pir2:PFOR complexes. In agreement with the THS assay, the final relaxed AlphaFold2 models showed stable interactions of PFOR with Pir1 as judged by PISZA analysis (Z‐score of 1.710 [stable association >1.5]; Figure 3a, Supplemental File S5A). Although we did not obtain any genomic library clone indicating interactions of PFOR with Pir2, AlphaFold2 also predicted stable interactions of PFOR with Pir2 with a Z‐score of 1.949 (stable association >1.5; Figure 3b, Supplemental File S5A). To test this prediction, a THS assay was carried out using pTRG/PFOR and pBT/Pir2 constructs to co‐transform the E. coli THS reporter strain. Indeed, this experiment strongly supports that a direct interaction is formed between Pir2 and PFOR (Figure 2e,f) though a negligible/slight growth of control 1 was observed in both Figure 2e,f.

Figure 3.

Ribbon cartoon diagram of AlphaFold2 Multimer 3D‐structure modeling of the (a) Pirin1:PFOR and (b) Pirin2:PFOR complexes. Pirin proteins are shown in green and PFOR in cyan. Residue interaction pairs are drawn with stick models (Inset). Amino acids making contact in the protein‐protein interface are depicted with font color corresponding to each chain. A list of the amino acid interaction pairs and their relative buried surface area is shown in Supplemental file S5A. See Material and Methods section for additional details on the computational modeling methodology. Images were generated using PyMol molecular graphics system version 2.5.8 (Schrödinger, LLC).

These findings prompted us to perform additional 3D‐structural modeling using Pir1 or Pir2 to understand if stable association with other metabolic enzymes of the central metabolism and energy conservation processes are also predicted. For this purpose, AlphaFold2‐Multimer predictions using unrelaxed mode were used to broadly screen putative protein‐protein interactions of Pir1 and Pir2 with enzymes involved in the biochemical pathways depicted in Supplemental File S5, including Zn‐ADH. The resulting 3D structural models were then used to calculate the PISZA‐interface Z‐score and the buried surface area of the interacting amino acids with Pir1 or Pir2 (Supplemental File S5). In agreement with the THS screen (Supplemental File S4), stable interactions of Zn‐ADH with Pir1 or Pir2 were predicted using this approach (Supplemental File S5A). Interestingly, 15 of the additional 140 tested enzymes were predicted to form stable protein‐protein interactions with Pir1, 17 with Pir2, and 17 with both Pir1 and Pir2 (Supplemental File S5A), while 91 of the enzymes screened did not form stable protein‐protein interactions with neither Pir1 nor Pir2 (Supplemental File S5B). Of the 49 proteins interacting with Pir1, Pir2 or Pir1 and Pir2, 32 enzymes belong to the oxidoreductase functional class, 9 are transferases, 2 are lyases, 2 are ligases, 2 proteins contain tetratricopeptide repeat (pfam13424 and pfam00515), 1 isomerase, and 1 conserved hypothetical protein. Among the oxidoreductases, in addition to PFOR, several subunits of the KFORs, Kor1AB and Kor2CDAEBG, were found to form stable protein‐protein interactions with Pir1 and/or Pir2 (Supplemental File S5A). Interestingly, the amino acid residues of Pir1 and Pir2 that are predicted to coordinate stable interactions in 50% of the stable complexes are shared, (i.e., Ala28, Asn29, Tyr31, Pro59 of Pir1 and Asp28, Glu29, Tyr31 of Pir2, Supplemental File S2), indicating that a common binding site may be used.

3.4. pir1 and pir2 deletion mutants alter the production of some SCFAs

To investigate whether pir1 and pir2 gene deletions could affect cellular metabolic activities, fermentation of SCFA products was determined (Supplemental File S6). The results reported are the mean and the data point range from two independent biological replicates determination. Although there were wide‐range variations in the production of some SCFAs by the same strain under the same growth conditions in two independent experiments, we describe here the SCFAs whose amount produced by the pir1 or pir2 mutants were clearly altered compared to the parent strain. For example, no lactate or propionate was detected in anaerobic mid‐log phase growth cultures of the parent strain. However, they were produced by the Δpir1, Δpir2, and Δpir1 Δpir2 double mutant strains (Supplemental File S6). The lactate produced by the ΔΔpir1 Δpir2 double mutant strain was approximately fivefold and twofold higher than the amount produced by the Δpir1 and Δpir2 mutants, respectively. This suggests that both Pir1 and Pir2 might contribute to the suppression of lactate production in the parent strain during mid‐log phase growth. The amount of propionate produced by the Δpir1 strain in mid‐log phase growth was reduced approximately threefold in the Δpir2 and Δpir1 Δpir2 double mutant strains. In contrast, the amount of isovalerate and phenylacetate produced by the parent strain in mid‐log phase growth was abolished or nearly abolished in the mutant strains. The amount of butyrate produced by the parent strain did not significantly change in the Δpir1 strain but was reduced approximately fivefold in the Δpir2 strain and increased approximately threefold in the Δpir1 Δpir2 double mutant strain compared to the parent strain. The amount of acetate produced in the parent strain was reduced by approximately 50% in both the Δpir1 and Δpir1 Δpir2 double mutant while the Δpir2 deletion did not significantly affect acetate production compared to the parent strain. This suggests that Pir1, but not Pir2, may have a modest effect on acetate production in mid‐log phase growth compared to the parent strain.

In mid‐log phase cultures under low‐iron conditions, the amount of propionate and isovalerate produced by the parent strain were greatly reduced or nearly abolished in all three mutant strains suggesting that Pir1 or Pir2 play a role in the production of propionate and isovalerate. In contrast, the amount of isobutyrate produced by the Δpir1 strain decreased approximately 15‐fold compared to the Δpir2 and Δpir1 Δpir2 double mutant strains while no isobutyrate was observed in the parent strain. This suggests that Pir2 has a stronger effect in the modulatory suppression of isobutyrate production than Pir1 in iron‐limiting conditions. In addition, butyrate was only produced in the Δpir1 Δpir2 double mutant strain in mid‐log phase growth in iron‐limiting conditions suggesting that Pir1 or Pir2 can repress butyrate as butyrate was only detected in the absence of both pir1 and pir2 genes.

Mid‐log phase cultures exposed to oxygen for 1 h did not seem to significantly affect changes in SCFA production by the pir mutants except that propionate was not detected in the Δpir1 strain and a twofold increase was observed in the Δpir1 Δpir2 double mutant compared to the amount of propionate produced by the parent strain.

There were no distinct changes in SCFAs produced in anaerobic stationary phase cultures after 24 h incubation except that the Δpir1 Δpir2 double mutant strain produced a minor amount of butyrate compared to its absence in the parent strain and single mutants.

In mid‐log phase cultures exposed to oxygen for 24 h, butyrate was produced in the Δpir1 and Δpir1 Δpir2 double mutant strains but not in the Δpir2 mutant or the parent strain cultures. This indicates that Pir1, but not Pir2, modulates the repression of butyrate production in B. fragilis in cultures exposed to oxygen for 24 h. Isovalerate was only detected in the Δpir2 mutant in cultures exposed to oxygen for 24 h but was undetectable in the Δpir1, Δpir1 Δpir2 double mutant and parent strains. Phenylacetate production increased approximately threefold in the Δpir1, Δpir2, and Δpir1 Δpir2 double mutant strains compared to the parent strain after oxygen exposure for 24 h.

In cultures exposed to oxygen under low‐iron conditions for 24 h, there was an increase of approximately eightfold and threefold in the production of isobutyrate by the Δpir2 and Δpir1 Δpir2 double mutant strains compared to the Δpir1 and parent strains, respectively. In addition, the amount of butyrate produced by the Δpir1 or Δpir2 strains increased approximately two to threefold in the Δpir1 Δpir2 double mutant strain compared to its undetectable presence in the parent strain. There was a very modest production of formate in iron‐limiting cultures exposed to oxygen for 24 h which was not detected in any of the mutant strains.

In anaerobic stationary phase growth cultures for 48 h, the amount of butyrate produced by the Δpir2 strain increased approximately fourfold in the Δpir1 Δpir2 double mutant strain compared to its absence in the parent and Δpir1 strains. In contrast, the amount of isovalerate produced by the parent and Δpir1 strains was reduced approximately twofold in the Δpir2 and Δpir1 Δpir2 double mutant strains while the amount of phenylacetate produced by the parent and Δpir1 strains was reduced approximately fourfold in the Δpir2 and Δpir1 Δpir2 double mutant strains.

Taken together, these findings indicate that Pir1 and Pir2 affect the upregulation or repression of different metabolic pathways involved mostly in the production of minor SCFA products dependent upon the culture growth conditions. However, the mechanisms that control B. fragilis fermentation pathways were not further pursued in this study and remain to be defined.

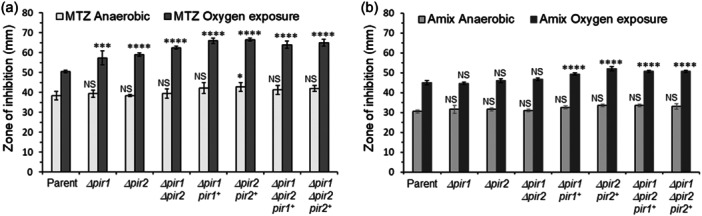

3.5. The effect of Δpir1 and Δpir2 mutations and constitutive expression of pir1 and pir2 genes in susceptibility to MTZ and AMIX

The results above indicate that Pir1 and Pir2 interactions with key enzymes of central metabolism alter metabolic pathways. To investigate this further, we focused our investigation on the effects of pir1 and pir2 gene deletions on antimicrobial susceptibility to MTZ and AMIX. In B. fragilis, MTZ sensitivity is linked to redox cycling processes that occur during carbon redox steps that flow through its different fermentation pathways, and it is also altered by heme availability (Paunkov et al., 2022a; Paunkov et al., 2022b; Paunkov et al., 2023). To examine if the effect of Pir1 and Pir2 on cellular metabolism described above could alter susceptibility to MTZ and AMIX, MIC determination and disc inhibition assays were performed (Table 2 and Figure 4). The sensitivity and resistance terms used in this study refer to the antimicrobial concentration required to inhibit growth of the parent strain, BF638R, and not to the antimicrobial breakpoint concentration guideline recommended for its clinical use. Disc diffusion assay showed that Δpir1, Δpir2 were statistically more sensitive to MTZ following oxygen exposure compared to the parent strain. The Δpir1 Δpir2 double‐mutant was more sensitive to MTZ than the Δpir1 and Δpir2 single mutant strains (Figure 4a). However, the genetically complemented strains enhanced sensitivity to MTZ compared to mutant strains following oxygen exposure, respectively. There were no significant changes in MTZ susceptibility in anaerobic cultures compared to the parent strain, except for a modest increase in MTZ sensitivity in the Δpir2 pir2 + strain (Figure 4a). The lack of pir genes did not significantly affect sensitivity to AMIX in anaerobic conditions or in cultures exposed to oxygen while the genetically complemented strains were statistically more sensitive to AMIX in oxygen exposed cultures (Figure 4b). It is unclear why genetically complemented strains Δpir1 pir1 + , Δpir2 pir2 + , Δpir1 Δpir2 pir1 + and Δpir1 Δpir2 pir2 + enhanced sensitivity to MTZ and AMIX instead of restoring sensitivity to parent strain level following oxygen exposure as determined by disc inhibition assays. Because genetic complementation with regulators or modulators may cause unexpected global phenotype effects, we assume that constitutive expression of pirins may have altered control of unidentified mechanisms that led to enhancement in sensitivity to these antimicrobials.

Table 2.

Agar dilution determination of minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC μg/mL) of metronidazole (MTZ) and amixicile (AMIX) for Bacteroides species and B. fragilis 638R mutant strains.

| Strains | MTZ anaerobic | MTZ O2 exposure | AMIX anaerobic | AMIX O2 exposure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BF638R | 0.5 | 0.5 | 2 | 1 |

| BF638R isolated at 2 μg/mL MTZ | 4 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| BF638R isolated at 4 μg/mL MTZ | 8 | 8 | 4 | 4 |

| BF638R isolated at 8 μg/mL MTZ | 16 | 16 | 4 | 4 |

| BF638R isolated at 16 μg/mL MTZ | 32 | 32 | 4 | 4 |

| B. fragilis ADB77 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 2 | 1 |

| B. fragilis BF8 | 16 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| B. fragilis ATCC 25285 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 |

| B. thetaiotaomicron VPI 5482 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| B. vulgatus ATCC 8482 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.0625 |

| B. fragilis 638R mutant strains | ||||

| Δpir1::tetQ | 0.5 | 0.5 | 2 | 1 |

| Δpir2::cfxA | 0.5 | 0.5 | 2 | 1 |

| Δpir1::tetQ Δpir2::cfxA | 0.5 | 0.5 | 2 | 1 |

| Δpir1::tetQ/pir1 + | 0.25 | 0.125 | 2 | 0.5 |

| Δpir2::cfxA/pir2 + | 0.25 | 0.125 | 2 | 0.5 |

| Δpir1::tetQ Δpir2::cfxA/pir1 + | 0.25 | 0.125 | 2 | 0.5 |

| Δpir1::tetQ Δpir2::cfxA/pir2 + | 0.25 | 0.125 | 2 | 0.5 |

| BF638R pir1 + | 0.5 | 0.0625 | 2 | 1 |

| BF638R pir2 + | 0.5 | 0.0625 | 2 | 1 |

| ΔPFOR::tetQ | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Δkor1AB | 0.5 | 0.5 | 2 | 1 |

| Δkor2AEBG | 1 | 1 | 4 | 2 |

| ΔPFOR::tetQ Δkor1AB | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| ΔpoxB | 1 | 0.5 | 4 | 1 |

| ΔPFOR::tetQ ΔpoxB | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 |

| Δkor1AB ΔpoxB | 1 | 0.5 | 2 | 1 |

| ΔPFOR::tetQ Δkor1AB ΔpoxB | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| ΔPFOR::tetQ Δkor2AEBG | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| ΔPFOR::tetQ Δkor1AB Δkor2AEBG | 1 | 1 | 4 | 2 |

| pyc::pFD516 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 |

| ΔfrdC247 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 1 | 0.5 |

| ΔfrdB260 | 0.25 | 0.0625 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| ΔfrdC/frdC + | 0.5 | 0.25 | 2 | 1 |

| ΔfrdB260/frdB + | 0.5 | 0.25 | 1 | 1 |

| ΔcitS Δicd ΔacnA | 1 | 1 | 4 | 2 |

| Δkor2AEBG ΔcitS Δicd ΔacnA | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| ΔPFOR::tetQ Δkor2AEBG ΔcitS Δicd ΔacnA | 4 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| ΔPFOR::tetQ Δkor1AB Δkor2AEBG ΔcitS Δicd ΔacnA | 4 | 2 | 4 | 2 |

| Hydrogen peroxide resistant strain, hpr | 0.5 | 0.25 | 2 | 1 |

| ΔkatB::tetQ | 0.5 | 0.25 | 2 | 1 |

| ahpCF:pFD516 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 2 | 1 |

| ahpF::pFD516 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 2 | 1 |

| ΔahpC::tetQ | 0.5 | 0.25 | 2 | 1 |

| ΔftnA:tetQ | 0.5 | 0.25 | 2 | 1 |

| Δbfr::cfxA | 0.5 | 0.25 | 2 | 1 |

| Δdps::tetQ | 0.5 | 0.25 | 2 | 1 |

| Δbfr::cfxA ΔftnA::tetQ | 0.5 | 0.25 | 2 | 1 |

| Δbfr Ddps | 0.25 | 0.25 | 2 | 0.5 |

| Δbfr::cfxA Δdps::tetQ/bfr + | 0.25 | 0.25 | 1 | 0.5 |

| Δbfr::cfxA Δdps::tetQ/dps + | 0.25 | 0.125 | 1 | 0.5 |

| ΔfnrA::tetQ | 0.5 | 0.5 | 2 | 1 |

| ΔnrfA::tetQ | 0.5 | 0.5 | 2 | 1 |

| ΔfnrC | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 |

| ΔrelA ΔspoT | 0.5 | 0.5 | 2 | 1 |

| ΔtrxB::cfxA | 0.25 | 0.25 | 1 | 0.5 |

| ΔtrxC ΔτrxD::cfxA ΔtrxE ΔtrxF ΔtrxG | 0.5 | 0.5 | 2 | 2 |

| ΔtrxC ΔtrxD::cfxA ΔτrxE ΔtrxF ΔtrxG ΔoxyR::tetQ | 0.5 | 0.25 | 2 | 0.5 |

Note: Anaerobic: Inoculated plates were immediately incubated anaerobically. O2 exposure: Duplicate plates were incubated for 16–20 h in an aerobic incubator at 37℃ before anaerobic incubation at 37℃.

Figure 4.

Disc diffusion assay sensitivity for (a) metronidazole (MTZ) and (b) Amixicile (AMIX). B. fragilis strains are depicted in each panel. Each bar represents the average zone of inhibition (mm) of at least three independent biological replicates. Vertical error bars denote standard deviation of the means from two independent experiments in triplicate. The significance of the p value was calculated by one‐way ANOVA followed by multiple comparisons using Dunnett and Bonferroni tests. Only groups with statistical significance in both tests are reported. p < 0.05 (*), p < 0.01 (**), p < 0.001 (***), and p < 0.0001 (****). NS, not significant.

In contrast, the MICs for MTZ and AMIX in the Δpir1, Δpir2, and Δpir1 Δpir2 double mutant strains were not altered in cultures exposed to oxygen compared to the parent strain as determined by the agar dilution assay (Table 2). However, the complemented pir1 and pir2 mutant strains were twofold more sensitive to MTZ (MIC 0.25 μg/mL) in anaerobic cultures, and fourfold more sensitive to MTZ (MIC 0.125 μg/mL) in cultures exposed to oxygen compared to the parent strain in agar dilution method, respectively (Table 2). The MTZ MIC of the parent strain overexpressing pir1 or pir2 genes remained unaltered in anaerobic conditions (MIC 0.5 μg/mL) but when these strains were exposed to oxygen, they showed an eightfold increase in MTZ sensitivity (MIC 0.0625 μg/mL) compared to the parent strain (Table 2). In addition, the genetically complemented strains expressing pir1 or pir2 genes did not affect AMIX MIC anaerobically, but it caused a twofold increase in AMIX sensitivity (0.5 μg/ml) in oxygen‐exposed cultures compared to the parent strain. The parent strain overexpressing pir1 or pir2 genes showed no changes in amixicile MIC anaerobically or following oxygen exposure (Table 2).

Altogether, these findings support the roles of Pir1 and Pir2 in altering susceptibility to MTZ or AMIX though there are some inconsistencies between disc inhibition and agar dilution assays. Because pirin proteins may modulate the derepression or suppression of different metabolic pathways, it is a challenge to point out which metabolic activities could contribute to changes in susceptibility to MTZ or AMIX. Therefore, mutants defective in a variety of cellular metabolic functions were used to examine their antimicrobial susceptibility.

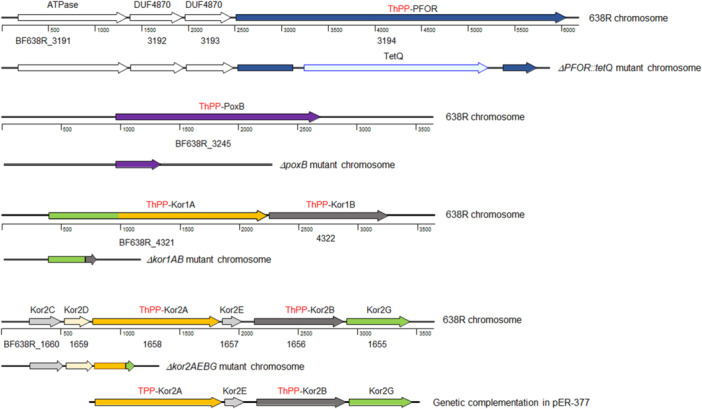

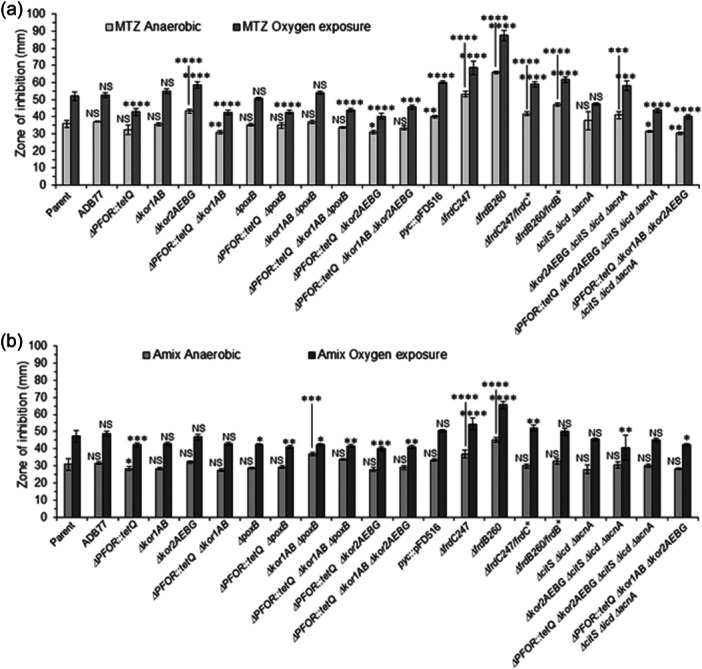

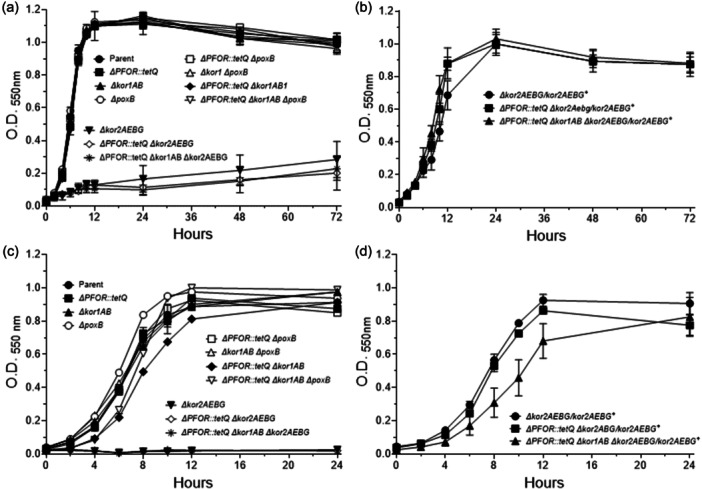

3.6. Different functional metabolic mutants were tested for susceptibility to MTZ and AMIX

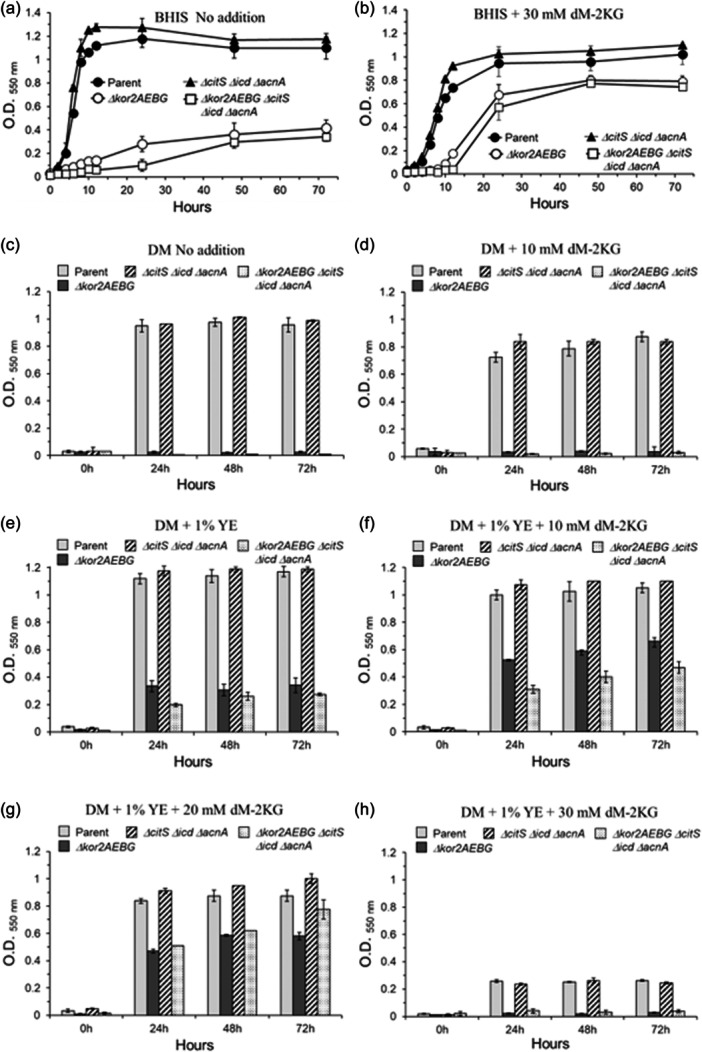

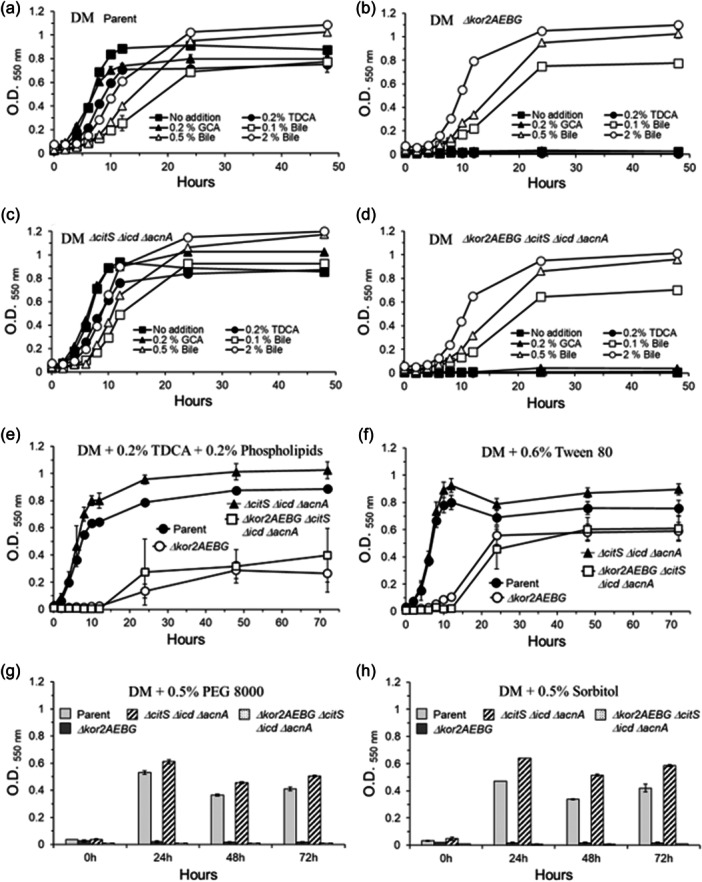

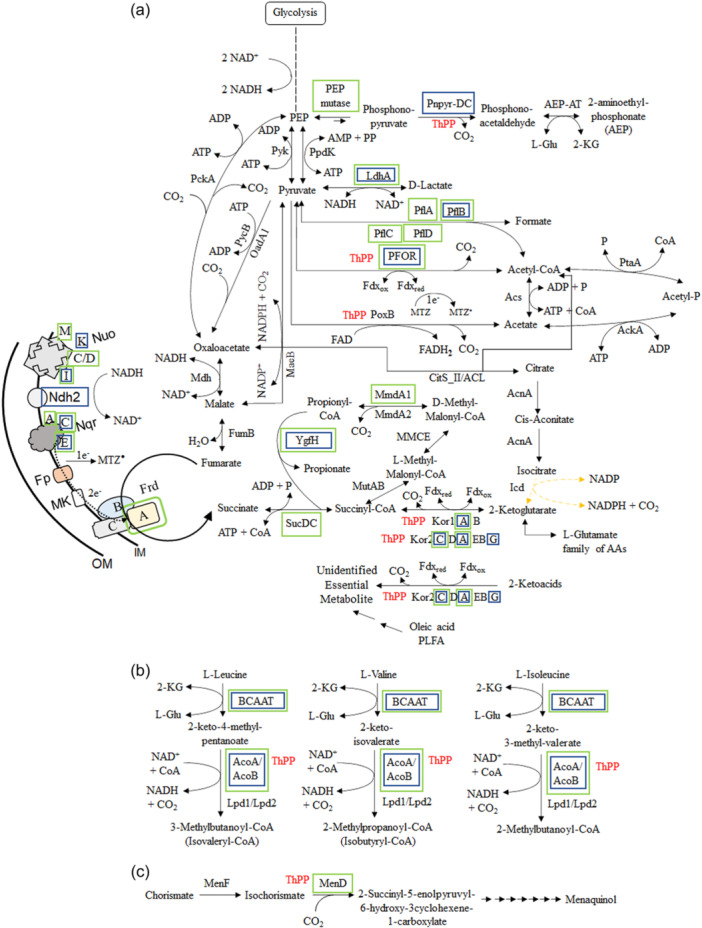

A series of mutant strains available in our laboratory collection encompassing different metabolic and physiological functions such as: ThPP‐binding 2‐ketoacid oxidoreductases, carboxylases, TCA cycle enzymes, oxidative and redox stress responses, stringent response, nitrate reductase ortholog, anaerobic Fnr‐like regulators, and iron‐storage proteins listed in Table 1 were tested for MTZ and AMIX susceptibility. The genomic organizations and the deletion construct diagrams of four members of the ThPP‐dependent 2‐ketoacid oxidoreductases: the PFOR, kor1AB, and kor2CDAEBG which use ferredoxin as electron acceptor, and the putative inner membrane enzyme that catalyzes the oxidative decarboxylation of pyruvate, poxB, used in this study are shown in Figure 5. The results are presented in Table 2, Figure 6, and Supplemental File S7. Of particular interest, the Δkor2AEBG, ΔpoxB and ΔPFOR::tetQ single mutant strains, the ΔPFOR::tetQ Δkor2AEBG double mutant, the ΔPFOR::tetQ Δkor1AB ΔpoxB triple‐mutant, and the ΔPFOR::tetQ Δkor1AB Δkor2AEBG triple mutant strains showed twofold increase in MTZ resistance (MIC 1 μg/ml) compared to the parent strain (MIC 0.5 μg/ml). No significant changes occurred in the Δkor1AB and pyc single mutant strains as determined by agar dilution assay (Table 2). In contrast, the Δkor2AEBG mutant was statistically more sensitive to MTZ in anaerobic cultures and cultures exposed to oxygen compared to the parent strain as determined by disc inhibition assay (Figure 6). The Δkor2AEBG ΔcitS Δicd ΔacnA quadruple mutant sensitivity to MTZ was not statistically significantly different from Δkor2AEBG single mutant as determined by disc inhibition assays or agar dilution method (Table 2, Figure 6). Interestingly, the ΔPFOR::tetQ Δkor2ABG ΔcitS Δicd ΔacnA quintuple mutant had an eightfold increase in MTZ resistance (MIC 4 μg/mL) anaerobically and fourfold increase (MIC 2 μg/mL) following exposure to oxygen compared to the parent strain (Table 2). The ΔcitS Δicd ΔacnA triple mutant was twofold more resistant to MTZ (MIC 1 μg/mL) and to AMIX (4 μg/mL, 2 μg/mL) in anaerobic cultures and cultures exposed to oxygen compared to the parent strain, respectively (Table 2). In contrast, the ΔcitS Δicd ΔacnA triple mutant susceptibility to MTZ or AMIX was not significantly altered as determined by disc inhibition assay (Figure 6). Insertional mutation of the pyruvate carboxylase biotin‐containing subunit gene, pyc, also increased susceptibility to MTZ anaerobically or in cultures exposed to oxygen as determined by disc inhibition assay but not in agar dilution assay. It is unclear why some strains showed conflicting susceptibility between disc inhibition and agar dilution methods determination.

Figure 5.

Schematic representation of B. fragilis 638R chromosomal regions for PFOR, PoxB, Kor1AB, and Kor2AEBG as shown in the panels. Each locus tag is depicted below the respective deduced ORF symbolized by an arrow. The designation of the predicted peptide product is depicted above each open arrow gene region respectively. The Arrow direction depicts the transcription orientation. Arrows filled with color represent the functional annotation group assigned to PFOR (dark blue), PoxB (purple), KorA (orang), KorB (dark gray), KorG (light green), KorD (gold) or, KorC (light gray) orthologs, respectively. The deletion construct representation of each chromosomal region mutant is shown below the native chromosome region, respectively. The DNA fragment containing the promoterless kor2AEBG genes cloned into the expression vector pFD340 (pER‐377) was used for genetic complementation studies. ATPase, predicted ATPase AAA+ superfamily; DUF4870, putative membrane protein of unknown function; Kor1A, 2‐ketoglutarate ferredoxin oxidoreductase subunit α (CBW24739); Kor1B, 2‐ketoglutarate ferredoxin oxidoreductase subunit β (CBW24740); Kor2A, 2‐ketoglutarate ferredoxin oxidoreductase subunit α (CBW22186); Kor2B, 2‐ketoglutarate ferredoxin oxidoreductase subunit β (CBW22184); Kor2C, conserved hypothetical protein containing tetratricopeptide repeat (CBW22188); Kor2D, ferredoxin, 2‐ketoglutarate‐acceptor oxidoreductase subunit δ (CBW22187); Kor2E, hypothetical protein (CBW22185); Kor2G, 2‐ketoglutarate ferredoxin oxidoreductase subunit γ (CBW22183); PFOR, pyruvate:ferredoxin oxidoreductase (GenBank accession number CBW23670); PoxB, putative pyruvate dehydrogenase (CBW23720); ThPP, thiamine diphosphate cofactor.

Figure 6.

Disc diffusion assay sensitivity for (a) metronidazole (MTZ) and (b) amixicile (AMIX). B. fragilis strains are depicted in each panel. Each bar represents the average zone inhibition (mm) of at least three independent biological replicates. Vertical error bars denote the standard deviation of the means from two independent experiments in triplicate. The significance of the p value was calculated by one‐way ANOVA followed by multiple comparisons using Dunnett and Bonferroni tests. Only groups with statistical significance in both tests are reported. p < 0.05 (*), p < 0.01 (**), p < 0.001 (***), and p < 0.0001 (****). NS, not significant.

The ΔPFOR::tetQ mutant was statistically more resistant to AMIX in anaerobic cultures and cultures exposed to oxygen compared to the parent strain as determined by disc inhibition assays (Figure 6b) but changes in AMIX susceptibility were not observed in agar dilution assay (Table 2). Interestingly, the Δkor1AB ΔpoxB was statistically more sensitive to AMIX anaerobically but more resistant to AMIX in cultures exposed to oxygen as determined by disc inhibition assays (Figure 6b) whereas no significant changes in susceptibility were seen in MIC values (Table 2). The ΔpoxB, ΔPFOR:tetQ ΔpoxB, ΔPFOR:tetQ Δkor1AB ΔpoxB, ΔPFOR::tetQ Δkor2AEBG, ΔPFOR::tetQ Δkor1AB Δkor2AEBG, Δkor2AEBG ΔcitS Δicd ΔacnA, and ΔPFOR::tetQ Δkor1AB Δkor2AEBG ΔcitS Δicd ΔacnA mutants were statistically more resistant to AMIX only in cultures exposed to oxygen, but no significant changes in susceptibility occurred in anaerobic cultures compared to the parent strain as determined by disc inhibition assays (Figure 6b). However, the ΔpoxB, ΔPFOR:tetQ ΔpoxB, ΔPFOR::tetQ Δkor1AB Δkor2AEBG, and ΔPFOR::tetQ Δkor1AB Δkor2AEBG ΔcitS Δicd ΔacnA were twofold more resistant to AMIX in anaerobic conditions as determined by agar dilution assays (Table 2).

Among the mutants involved in the TCA cycle shown in Figure 6, it was the deficiency in the fumarate reductase subunits, frdB and frdC that caused the highest increase in MTZ and AMIX sensitivity. The ΔfrdB mutant had a twofold increase in MTZ susceptibility (MIC 0.25 μg/mL) compared to the parent strain. Remarkably, following oxygen exposure, the ΔfrdB mutant had an eightfold increase in MTZ susceptibility (MIC 0.0625 μg/mL) (Table 2). The lack of the frdB or the frdC subunits in increasing MTZ and AMIX susceptibility is also clearly noticeable in the disc inhibition assays (Figure 6). However, the genetically complemented strains, ΔfrdB260/frdB + and ΔfrdC/frdC + brought MTZ susceptibility close, but not identical, to the parent strain levels as determined by MIC and disc inhibition assays (Table 2 and Figure 6). It is unclear why there was a significant difference in MTZ and AMIX susceptibility between the two fumarate reductase deficient strains, ΔfrdB260 and ΔfrdC247 though ΔfrdC247 is reverted to thyA + . It is unlikely that this was due to the addition of succinate and thymine supplements to the media since the susceptibility of their parent strain ADB77 (638R ΔthyA isogenic) used as a control was not altered compared to the 638R strain. Perhaps, unidentified intrinsic factors may exist though there are no significant differences in molar growth yield or generation time between ΔfrdB and ΔfrdC strains (Baughn & Malamy, 2003).

Overall, these findings appear to associate deficiencies in the oxidative TCA cycle branch such as lack of PFOR with significantly more resistance to MTZ while deficiencies in the reductive TCA branch genes such as frdB, and frdC with significantly more sensitivity to MTZ. These alterations in the oxidative or reductive balance of the central metabolism could ultimately lead to dysregulation of the NADH/NAD+ redox processes and cellular bioenergetics. To test this assumption, inhibitors of B. fragilis NADH:electron acceptor transport coupling system (ETS) for fumarate reductase reduction of fumarate to succinate as described previously (Harris & Reddy, 1977) were used as mentioned below.

The nitrite reductase deficient strain, ΔnirfA::tetQ, was significantly more sensitive to MTZ anaerobically but not in cultures exposed to oxygen (Supplemental File S7A) while it did not alter sensitivity to AMIX compared to the parent strain (Supplemental File S7C). Strains deficient in thiol/disulfide redox homeostasis such as ΔtrxB::tetQ, and ΔtrxC ΔtrxD::cfxA ΔtrxE ΔtrxF ΔtrxG ΔoxyR::tetQ sextuple mutants were significantly more sensitive to MTZ anaerobically but not in oxygen exposed cultures. The ahpCF::pFD516 and ahpF::pFd516 insertional mutants were significantly more sensitive to MTZ in both anaerobic cultures and cultures exposed to oxygen compared to the parent strain. The sensitivity of the ΔahpC::tetQ single mutant was not altered compared to the parent strain as determined by disc inhibition assays (Supplemental File S7A). This suggests that the AhpF subunit of the alkyl hydroperoxide reductase may contribute to the resistance to MTZ in the parent strain. The ΔtrxB::tetQ strain was significantly more sensitive to AMIX in both anaerobic growth and cultures exposed to oxygen while the ΔtrxC ΔtrxD::cfxA ΔtrxE ΔtrxF ΔtrxG ΔoxyR::tetQ sextuple mutants were more resistant to AMIX in anaerobic cultures (Supplemental File S7C). The MICs for MTZ and AMIX determined for the strains mentioned in Supplemental File S7 are shown in Table 2.

Moreover, this study shows that members of the ferritin superfamily, FtnA Dps and Dps‐like protein, Bfr play a significant role in increasing sensitivity to MTZ and AMIX (Supplemental File S7B,D). The Δdps::tetQ Δbfr::cfxA double mutant was significantly more susceptible to MTZ and AMIX in anaerobic cultures and upon oxygen exposure compared to the ΔftnA, Δdps and Δbfr single mutant strains as determined by disc inhibition assays (Supplemental File S7B,D). This indicates that there might be a synergistic effect of Dps and Bfr contributing to MTZ and AMIX antibiotic resistance. Deletion of the ftnA gene had a modest increase in AMIX sensitivity in oxygen‐exposed cultures. However, it was the genetic complementation of the Δdps::tetQ Δbfr::cfxA double mutant strain with bfr + or dps + genes in the strains Δdps::tetQ Δbfr::cfxA bfr + and Δdps::tetQ Δbfr::cfxA dps + that caused a significant increase in susceptibility to MTZ and AMIX in anaerobic cultures and cultures exposed to oxygen compared to the single mutants and the parent strain, respectively. It is unclear why the constitutive expression of dps or bfr genes enhanced the sensitivity of the Δdps::tetQ Δbfr::cfxA double mutant strain to MTZ and AMIX instead of bringing the mutant sensitivity closer to the parent strain levels. It is unlikely that this is simply due to lowering intracellular free ferrous iron content by increasing iron‐stored levels. This contradicts a previous study showing that deficiency in the ferrous uptake system FeoAB increases MTZ resistance (Veeranagouda et al., 2014). However, the possibility that changes in iron homeostasis caused alterations in metabolic pathways activities that affect MTZ susceptibility cannot be disregarded.

Because several metabolic pathways, that can with different intensities alter B. fragilis 638R susceptibility to MTZ and AMIX, have reduction/oxidation functions, we cannot rule out that they are linked to dysregulation of ETS and redox balance as a common determining factor in MTZ and AMIX susceptibility. Therefore, we investigated whether ETS inhibitors and redox cycling agents could play a role in MTZ and AMIX susceptibility.

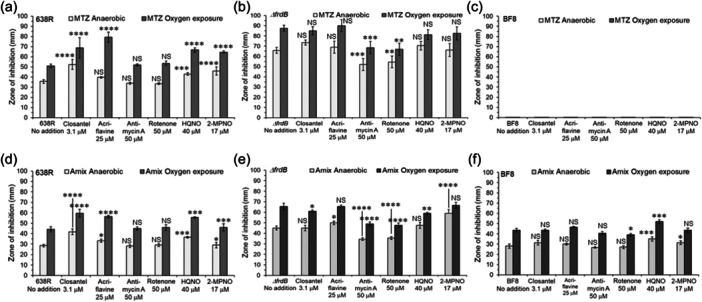

3.7. The effect of ETS inhibitors on MTZ and AMIX susceptibility

The non‐inhibitory concentrations of the ETS inhibitors: acriflavine, rotenone, 2‐heptyl‐hydroxyquinoline‐N‐oxide (HQNO), and antimycin A used in the disc inhibition assays are mentioned in the text and Materials and Methods section. Closantel, a halogenated salicylanilide antimicrobial whose mechanism of action is not completely understood but decouples oxidative phosphorylation and leads to inhibition of ATP synthesis (Rajamuthiah et al., 2014; Tran et al., 2016; Van Den Bossche et al., 1979; Williamson & Metcalf, 1967), and 2‐Mercaptopyridine‐N‐oxide (2‐MPNO), an NADH:fumarate reductase inhibitor (Turrens et al., 1999) were also included in this study. The BF638R strain was statistically more sensitive to both MTZ and AMIX in the presence of closantel, acriflavine, HQNO, and 2‐MPNO under both anaerobic and oxygen‐exposed conditions except that acriflavine did not change susceptibility to MTZ anaerobically (Figure 7a,d). Antimycin A and rotenone did not cause statistically significant changes in either MTZ or AMIX susceptibility compared to no addition control as determined by disc inhibition assays.

Figure 7.

Disc diffusion assay sensitivity of B. fragilis strains to metronidazole (MTZ), panels A,B,C or for Amixicile (AMIX), panels D,E,F. A and D: Parent (B. fragilis 638R). B and E: ΔfrdB (derived from ADB77, isogenic BF638R thy ‐ strain). C and F: B. fragilis BF8 strain (nimB + ). Strain designations are depicted in each panel. For these experiments, 20 mM succinate and 50 μg/ml thymine were added to the BHIS media. Each bar represents the average zone of inhibition (mm) of at least three independent biological replicates. Vertical error bars denote the standard deviation of the means from two independent experiments in triplicate. The significance of the P value was calculated by one‐way ANOVA followed by multiple comparisons using Dunnett and Bonferroni tests. Only groups with statistical significance in both tests are reported. p < 0.05 (*), p < 0.01 (**), p < 0.001 (***), and p < 0.0001 (****). NS, not significant.

The ΔfrdB mutant strain, which is significantly more sensitive to MTZ and AMIX than to the parent strain (Figure 6), did not show significant susceptibility changes to MTZ in the presence of closantel, acriflavine, HQNO, or 2‐MPNO compared to no addition control (Figure 7b). However, in the presence antimycin A and rotenone, the ΔfrdB mutant was more resistant to MTZ and AMIX compared to no addition control (Figure 7b,e). In the presence of closantel or HQNO, the ΔfrdB mutant was more resistant to AMIX in cultures exposed to oxygen but not in anaerobic cultures. However, in the presence of acriflavine or 2‐MPNO, it was more sensitive to AMIX in anaerobic cultures but did not significantly change susceptibility in cultures exposed to oxygen compared to no addition control (Figure 7e). To determine if ETS could affect MTZ resistance in a strain carrying an MTZ resistance nim gene ortholog, the BF8 strain carrying nimB was tested. The presence of ETS did not affect the BF8 resistance to MTZ either (Figure 7c). The BF8 sensitivity to AMIX did not significantly change in the presence of closantel, acriflavine, or antimycin A compared to control (Figure 7f). The BF8 strain was significant more sensitive to AMIX in the presence of HQNO in anaerobic cultures and cultures exposed to oxygen. There was a modest increase in AMIX sensitivity in the presence of 2‐MPNO in anaerobic culture but not in culture exposed to oxygen, and a modest increase in resistance to AMIX in the presence of rotenone in oxygen‐exposed cultures (Figure 7f).

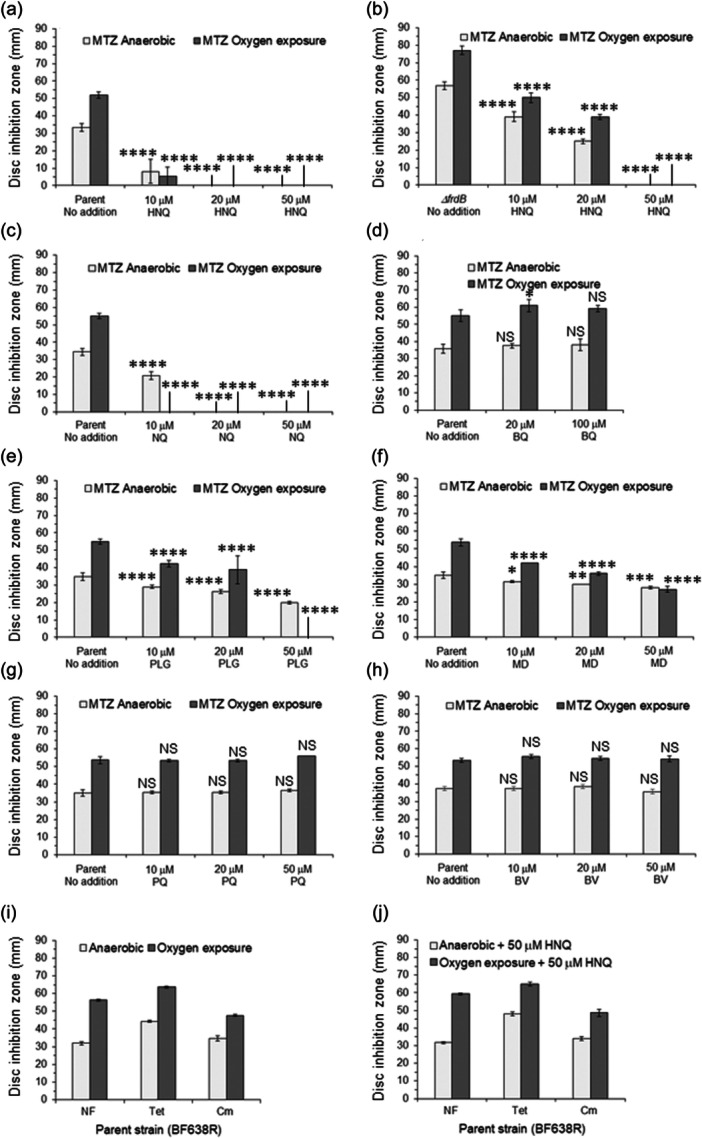

3.8. The effect of redox cycling agents on MTZ susceptibility

In contrast to the effects of ETS, when the redox cycling agents 1,4‐naphthoquinone (NQ) and 2‐hydroxy‐1,4‐naphthoquinone (HNQ), which are analogs to menadione (2‐methyl‐1,4‐naphthoquinone) were added to the culture media at 10 to 20 μM, they abolished B. fragilis 638 R sensitivity to MTZ as determined by agar dilution and disc inhibition assays (Figure 8a,c and Table 3). Plumbagin (5‐hydroxy‐2‐methyl‐1,4‐naphthoquinone) and menadione caused lesser effect (Figure 8e,f) while there were no significant effects observed with 1,4‐benzoquinone, paraquat (methyl viologen), or benzyl viologen compared to no addition control as determined by disc inhibition assays (Figure 8d,g,h). The effect of 10 μM and 20 μM of HNQ on the ΔfrdB mutant resistance to MTZ was significantly less than the parent strain (Figure 8a,b). Moreover, the addition of HNQ did not alter the parent strain B. fragilis 638R susceptibility to other antimicrobials such as nitrofurantoin, tetracycline, or chloramphenicol compared to no addition control, respectively (Figure 8i,j). The effect of redox cycling agents on MTZ susceptibility was not due to bacterial growth inhibition because they did not significantly affect the CFU counts in anaerobic conditions or cultures exposed to oxygen at concentrations equal to or above the ones used in this study (Supplemental File S8).

Figure 8.

Disc diffusion assays. Susceptibility of B. fragilis 638R strain (Parent) and its isogenic ΔfrdB deletion mutant to metronidazole (MTZ). Panels (a) and (b): in the presence of 2‐hydroxy‐1,4‐napththoquinone (HNQ). Panel (c): in the presence of 1,‐4‐naphthoquinone (NQ). Panel (d): in the presence of 1,4‐benzoquinone (BQ). Panel (e): in the presence of plumbagin (PLG). Panel (f): in the presence of menadione (MD). Panel (g): in the presence of paraquat (PQ). Panel (h): in the presence of benzyl‐viologen (BV). Panels i and j: Susceptibility of B. fragilis 638 R strain to nitrofurantoin (NT), tetracycline (Tet), or chloramphenicol (Cm) exposed to oxygen with no addition (i) or addition of 50 μM HNQ (j). Each bar represents the average zone inhibition (mm) of at least three independent biological replicates. Vertical error bars denote the standard deviation of the means from two independent experiments in triplicate. Panels a–h: The significance of the p value was calculated by one‐way ANOVA followed by multiple comparisons using Dunnett and Bonferroni tests. Only groups with statistical significance in both tests are reported. p < 0.05 (*), p < 0.01 (**), p < 0.001 (***), and p < 0.0001 (****). NS, not significant. For panels i and j, no statistical analyzes were performed.

Table 3.

Metronidazole minimal Inhibitory concentration (MIC μg/mL) for B. fragilis 638R in BHI media containing 5 μg/mL hemin (l‐cysteine was omitted) supplemented with 2‐hydroxy‐1,4‐naphthoquinone, or 1,4‐naphthoquinone.

| Media supplement/MTZ MIC μg/mL | Anaerobic | O2 exposure |

|---|---|---|

| Control (No addition) | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| 2‐hydroxy‐1,4‐Naphthoquinone 10 μM | 8 | 4 |

| 2‐hydroxy‐1,4‐Naphthoquinone 50 μM | 16 | 8 |

| 2‐hydroxy‐1,4‐Naphthoquinone 100 μM | 32 | 32 |

| 1,4‐Naphthoquinone 10 μM | 2 | 2 |

| 1,4‐Naphthoquinone 50 μM | 16 | 16 |

| 1,4‐Naphthoquinone 100 μM | 32 | 32 |

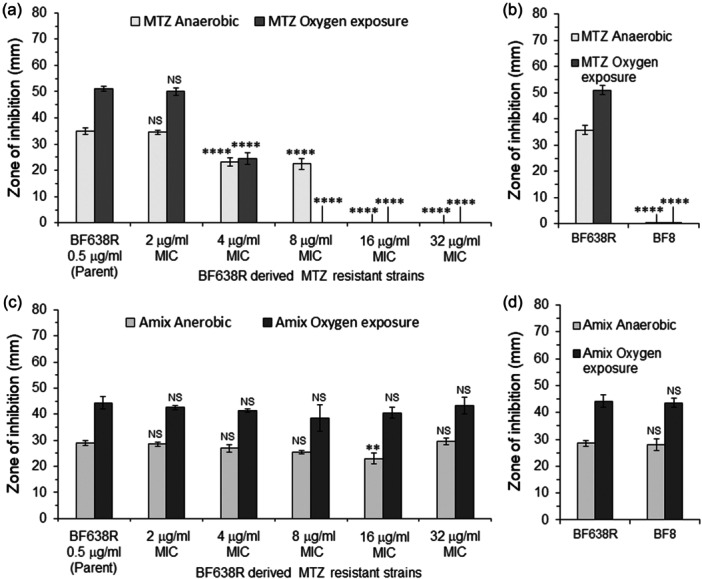

3.9. No crossed MTZ resistance and AMIX susceptibility

There is no report of AMIX‐resistant mutant strains and this led us to test whether resistance to MTZ could alter susceptibility to AMIX. MTZ resistant strains were obtained by isolating random strains grown in increasing MTZ concentrations at 2, 4, 8, and 16 μg/mL. The findings showed that BF638R(2 μg/mL) (MIC 4 μg/mL) showed no increase in AMIX resistance compared to the parent strain (Table 2). The BF638R(4 μg/mL) (MIC 8 μg/mL), BF638R(8 μg/mL), (MIC 16 μg/mL), and BF638R(16 μg/mL) (MIC 32 μg/mL) strains only showed a twofold increase in AMIX MIC (4 μg/mL) (Table 2). In Figure 9a,b, a comparison is shown for the random MTZ‐induced resistant strains and the BF8 MTZ resistant strain using disc inhibition assays, respectively. In addition, the evaluation of the susceptibility to AMIX in the random MTZ‐induced resistant strains and the BF8 strain is shown in Figure 9c,d. The findings show MTZ resistance mechanism did not have any significative effect on AMIX susceptibility in anaerobic cultures or cultures exposed to oxygen, except for a modest increase in AMIX resistance in the BF638R resistant to MTZ at 16 μg/ml in anaerobic cultures but not in cultures exposed to oxygen as determined by disc inhibition assays (Figure 9c). There were no statistically significant differences in AMIX susceptibility between the BF638R and BF8 strains as determined by disc inhibition assays and agar dilution method (Figure 9d, Table 2).

Figure 9.

Disc diffusion assay sensitivity for (a‐b) metronidazole (MTZ) and (c‐d) Amixicile (AMIX). B. fragilis strains are depicted in each panel. Each bar represents the average zone inhibition (mm) of at least three independent biological replicates. Vertical error bars denote the standard deviation of the means from two independent experiments in triplicate. In panels a and c, the significance of the p value was calculated by one‐way ANOVA followed by multiple comparisons using Dunnett and Bonferroni tests. Only groups with statistical significance in both tests are reported. p < 0.05 (*), p < 0.01 (**), p < 0.001 (***), and p < 0.0001 (****). NS: Not significant. In Panels B and D, the significance of the p value was calculated using an unpaired t‐test (parametric and two‐tailed) to compare the means of the two groups.

3.10. AMIX has antimicrobial activity against B. fragilis 638R in an in vivo intra‐abdominal infection model