Abstract

Background

Person-centred care is becoming increasingly recognised as an important element of palliative care. The current review syntheses evidence in relation to transitions in advanced cancer patients with palliative care needs. The review focuses on specific elements which will inform the Pal-Cycles programme, for patients with advanced cancer transitioning from hospital care to community care. Elements of transitional models for cancer patients may include, identification of palliative care needs, compassionate communication with the patient and family members, collaborative effort to establish a multi-dimensional treatment plan, review and evaluation of the treatment plan and identification of the end of life phase.

Methods

A scoping review of four databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, PsycINFO) was conducted to identify peer-reviewed studies published from January 2013 to October, 2022. A further hand-search of references to locate additional relevant studies was also undertaken. Inclusion criteria involved cancer patients transitions of care with a minimum of two of components from those listed above. Studies were excluded if they were literature reviews, if transition of care was related to cancer survivors, involved non-cancer patients, had paediatric population, if the transition implied a change of therapy and or a lack of physical transit to a non-hospital place of care. This review was guided by Arksey and O’Malley’s framework and narrative synthesis was used.

Results

Out of 5695 records found, 14 records were selected. Transition models identified: increases in palliative care consultations, hospice referrals, reduction in readmission rates and the ability to provide end of life care at home. Transition models highlight emotional and spiritual support for patients and families. No uniform model of transition was apparent, this depends on the healthcare system where it is implemented.

Conclusions

The findings highlight the importance of collaboration, coordination and communication as central mechanisms for transitional model for patients with advanced cancer. This may require careful planning and will need to be tailored to the contexts of each healthcare system.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12904-024-01510-7.

Keywords: Delivery of health care, Transitions, Collaboration, Communication, Integrated, Palliative care, Review, Oncology, Chronic disease, Cancer

Introduction

Palliative care has been defined as “approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families who are facing problems associated with life-threatening illness. It prevents and relieves suffering through the early identification, correct assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, whether physical, psychosocial or spiritual.” [1]. Within the context of palliative care, the concept of person-centred care has emerged as a pivotal paradigm shift which emphasises the individual’s preferences, needs, values, and goals in the delivery of care [2]. A person-centred approach in palliative care demands a comprehensive understanding of patients’ physical, emotional, psychological, and spiritual needs [3]. In this context, person-centred care serves as a guiding concept that respects patients’ autonomy, dignity, and agency even in the face of challenging health circumstances. By incorporating patients’ voices into the decision-making process, health professionals create an environment where patients are active partners in shaping their care [4].

Numerous studies and frameworks underline the significance of person-centred care within palliative contexts. McCormack and McCance [5] highlight the fundamental role of relationships and communication in fostering person-centred care, stressing the importance of building rapport and trust between patients, families, and healthcare providers. The World Health Organization (WHO) recognizes the importance of prioritizing patients’ values and preferences in its guidelines for palliative care, underscoring the need to engage patients in shared decision-making and ensuring their emotional well-being throughout the process [1]. The Picker Principles [6] of person-centred care include fast access to reliable advice, effective treatment, clear information, communication and support, involvement in decisions and respect for preferences, involvement and support for family and carers, emotional support, empathy and respect, and attention to physical and environmental needs. One final and possibly overarching principle that facilitates optimal person-centred care is continuity of care and transitions to and between settings. Patients are most likely to receive continuity of care through a small number of available health care professionals who provide multidisciplinary care and regularly share information to all other health care professionals involved [7].

Transition models can involve multiple referral pathways and are designed to facilitate the seamless movement of patients across care settings or stages of illness [8]. For example, when a patient moves into the end of life period, which may be defined as “the time preceding an their natural death from a process that is unlikely to be arrested by medical care” [9] maintaining the focus on individual preferences and needs. These models not only enhance communication, coordination and collaboration between healthcare providers but also empower patients and their families to actively engage in care planning and decision-making. The need and importance of transition pathways is embedded within many of the revised European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC) Norms and Standards for palliative care across Europe, and enabling people to be cared for and die in their preferred place is an important indicator of good practice [3].

One recent example of a transition model is called ‘Pal-Cycles’, which is a palliative care programme for patients with advanced cancer transitioning from hospital care to community care and is adaptable to local cultures and healthcare systems. Through previous research, a framework was derived consisting of working elements of integrated palliative and supportive care [10]. The Pal-Cycles programme builds on this with a focus on the transition from hospital to homecare. Pal-Cycles has five components to improve transitions in care for those with palliative care needs through better communication with patients and families, and better alignment between hospital (oncology) and community palliative care:

Identification at discharge of a cancer patient with palliative and supportive care needs in collaboration with the oncologist and the hospital palliative care team.

Compassionate communication towards the patient and their family. Depending on taboos, social and cultural factors, this component needs to be adapted to the local situation and calls for careful and compassionate communication strategies to be trained in this project.

Collaborative effort to establish a multidimensional treatment plan and follow-up. Here, somatic, psychological, social, and spiritual/pastoral care professionals are collaborating in order to provide a holistic assessment and joint hospital-home treatment plan for the patient, including possible care scenarios, symptom management, advance care planning, and resources needed at home (or homelike environment).

The treatment plan will be discussed with the patient and the family in an interactive and reciprocal way. Periodic evaluations will guide the follow-up of this treatment plan, being led by the GP, oncologist or palliative care team, depending on patient place of stay, care needs, and local possibilities. Here, we will make use of e-health and teleconsultation possibilities to provide multidisciplinary team meetings.

Based on the above-mentioned periodic evaluation, the terminal phase can be indicated with intensification of treatment and end-of-life talks. This will also include consultation with patient and families about ethically and legally sensitive issues like withdrawal of treatment, preferred place of death, rituals at the end of life, depending on local possibilities and religious habits.

An overarching ambition of the Pal-Cycles programme is to develop a comprehensive model for transitions that is suitable to be implemented in European countries. Transitions in care can be described in relation to transitions in settings of care, for example from hospital to home or nursing home, transitions in goals of care, and transitions in care management, between different medical teams or settings [11].

Aim

To conduct a scoping review of studies to evidence the five components of the Pal-Cycles programme, related to transitions in care for advanced cancer patients with palliative care needs, evidence their interconnectedness, and make recommendations on how to better implement the transitional model to the local situation for patients with advanced cancer.

Objectives

To evidence the interconnectedness of the five components.

To make recommendations on how to better implement a transitional model for patients with advanced cancer.

Methods

Methodology

Scoping reviews provide a broad overview of a topic looking at emerging evidence and are often the first step in research development [12]. The scoping review method is suitable for reviews that seek to systematically map available literature on a topic and identify gaps in the literature and evidence base [13]. Arksey and O’Malley published the first framework detailing the purpose of the scoping review method which included detailed steps to guide researchers [12]. Arksey and O’Malley’s framework guided the current review, including the following steps [14]:

Identifying the research question(s).

Identifying the relevant studies.

Study selection.

Charting the data.

Collating, summarizing, and reporting the data.

A previous systematic review, which was conducted to identify empirically-evaluated models of palliative care in cancer and chronic disease in Europe [10], was used as the basis for the current review, as it used similar search terms and was evaluating models of palliative care intervention which shared the same components. This review found models with these five components showed improved symptom control, less caregiver burden, improvement in continuity and coordination of care, fewer admissions, cost effectiveness and patients dying in their preferred place. The current paper uses the following definition of a model: “standardised designs that provide frameworks for the organization of care for people with a progressive life-threatening illness and/or for their (in)formal caregivers” [10].

Search strategy

A literature search was conducted in MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, PsycINFO to identify peer-reviewed studies published from January 2013 (following the previous systematic review [10]) to October, 2022. The search strategy was built and adapted for each database with an experienced information specialist. See appendix 1 for search strategy. A hand-search of references of included papers to locate additional relevant studies was also undertaken. The reporting for this scoping review was guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) Checklist [15].

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Studies with a qualitative or quantitative design (either experimental or quasi-experimental), that assessed cancer patients’ transitions of care including at least two of the five cornerstone components of the Pal-Cycles project were included. Studies were excluded if the transition of care was related to cancer survivors, involved non-cancer patients, had a paediatric population, or if the transition of care implied a change of therapy and lack a physical transit to a non-hospital place of care. All types of literature reviews, posters, editorial letters, case reports and non-English language papers were also excluded.

Study selection

The search results were deduplicated with Endnote and uploaded to Rayyan for title and abstract screening. Two reviewers (JM and DB) undertook a pilot title and abstract screening of 10% of the retrieved articles to ensure agreement in standard eligibility criteria. After a brief debriefing session that focused on what was learnt from this first exercise involving all of the authors, four authors independently (AH, JM, RL, and DB) each screened approximately 25% of the remaining articles. Two other authors (NP and SP) screened articles where there was uncertainty and settled disagreements about eligibility. The selected studies were reviewed for inclusion independently, using their full text by two authors and later audited by a third author. Conflicts of opinion were resolved through discussion until a consensus was reached.

Data extraction

Reviewers extracted data onto a framework of the five Pal-Cycles components independently, which was further checked by the other reviewers.

Quality appraisal and analysis

The Hawker et al. [16] quality appraisal tool was used by one reviewer to assess the completeness and quality of the information; this was checked by a second reviewer. This approach describes the studies’ content without excluding papers on a given rating. A narrative synthesis was performed using the Guidance on the Conduct of Narrative Synthesis in Systematic Reviews [17].

Results

Search results

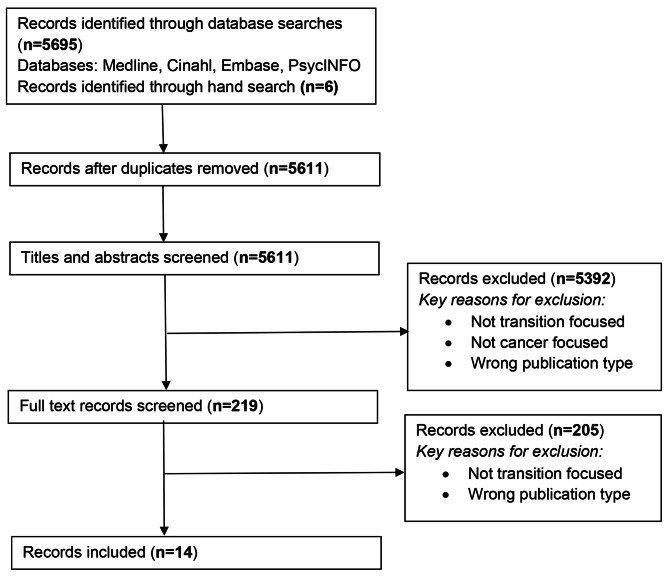

A total of N = 5695 records were identified from the four databases and N = 6 identified through further hand-searches, N = 90 records were excluded as duplicates, and a further N = 5392 records were excluded during title and abstract screening. Following full text review, a further 205 records were excluded, leaving 14 included in the review. See Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow chart for identified records

Characteristics of included studies

The 14 included studies were published between 2014 and 2022. The majority of studies took place in Europe (Italy, Sweden, Norway, Belgium, Netherlands, Spain, United Kingdom (UK), Denmark and Hungary). Four took place in the United States of America (USA), and one in each of Japan and Singapore. Each record included information in relation to a minimum of two of the components previously described. See Table 1.

Table 1.

Included records relative to components described

| Studies | Components | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author/ Date/ Country | Design | Sample | Key findings | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Blackhall et al. 2016 [18] USA | Quantitative pre-post intervention prospective cohort measuring timing of referral to outpatient palliative care and impact on end-of-life care | 207 patients with advanced cancer | Patients involved in the intervention had fewer hospitalisations at the end of life. | X | X | |||

|

Calton et al. 2017 [19] USA |

Longitudinal prospective cohort (6-month community bridge pilot gave patients access to home-based palliative care) | 17 patients with cancer and complex care needs | Home-based palliative care filled an unmet need for patients with advanced, metastatic cancer who desired ongoing cancer treatment, but were also in need of intensive end-of-life home services. Community bridge providers acted as crisis managers and reporters for oncologists. | X | X | X | X | X |

|

Casotto et al. 2017 [20] Italy |

Retrospective cohort | 17,604 decedent cancer patients | A well-integrated palliative care approach can be effective in further reducing the percentage of patients who spent many days in hospital and/or undergo frequent and inopportune changes of their care setting during their last month of life. | X | X | X | ||

|

Duffy et al. 2018 [21] USA |

Single-centre, prospective, pilot initiative | 27 cancer patients | The initiative used a hospice discharge checklist, pharmacist-led discharge medication reconciliation in consultation with the primary team responsible for inpatient care, review of discharge prescriptions, and facilitation of bedside delivery of discharge medications. There was significant (P = .035) improvement in hospice organizations’ perceptions of discharge readiness. | X | X | |||

|

Malmstrom et al. 2013 [22] Sweden |

Semi-structured focus-group interviews and conventional qualitative content analysis | 17 (patients who had undergone oesophageal cancer surgery) | Patients need a plan for the future, help in navigating the healthcare system and the provision of clear, honest information and a system that overarches the gap between in and out-patient care. Patients need support that starts at the hospital and continues to out-patient care. Support should focus on: developing a plan for the future, providing patients with information that will enable them to understand their new life situation. | X | X | X | X | |

|

Johansen and Ervik 2022 [23] Norway |

Qualitative focus group and interview study + thematic analysis (realist paradigm) | 52 (15 district nurses, 15 oncology nurses, 17 GPs, 5 physiotherapists / occupational therapists) | “Talking together” was perceived as the optimal form of collaboration. Nurses and GPs had similar perceptions of their worst-case scenario in primary palliative care: the sudden arrival after working hours of a sick patient lacking information. Lack of communication, both locally and between specialist and primary care, was a key factor in the worst-case patient scenarios for GPs and nurses working in primary palliative care. | X | X | X | X | |

|

Ko et al. 2014 [24] Belgium, Netherlands, Italy and Spain |

Mortality follow-back weekly questionnaires + statistical analysis of cross-country variations | 2037 (patients with advanced cancer in the last three months of life) | Over half of patients had at least one transition in care setting within the last three months of life. One third of patients in 3 of the countries had a last week hospital admission and died there. This symptom burden in the last week of life indicates the need for further integration of palliative care into oncology. | X | X | X | ||

|

Murakami et al. 2022 [25] Japan |

Quantitative - questionnaire post intervention | 151 (84 staff, 67 bereaved families) | Using an information sharing tool for GPs, patients, families and a specialist palliative care outreach team, led to an increase in home deaths. For the survey involving the medical staff, factors, such as “improved awareness of an multidisciplinary team,” were identified. For the survey involving the bereaved families, factors, such as “improvement of communications between patients and healthcare professionals,” were identified. | X | X | X | X | |

|

Noble, B. et al. 2015 [26] UK |

Mixed methods - retrospective analysis of secondary-care use in the last year of life; financial evaluation; qualitative interviews; a postal survey of General Practices; and a postal survey of bereaved caregivers. To evaluate The Midhurst Macmillan Specialist Palliative Care Service (MMSPCS) - a UK, medical consultant-led, multidisciplinary team aiming to provide round-the-clock advice and care, including specialist interventions, in the home, community hospitals and care homes. |

232 GP practices 102 bereaved carers |

Midhurst service patients spent less time in hospital and had fewer hospital attendances. Outpatient attendances were higher for the Midhurst group. Bereaved carers rated home services good or excellent (83%). 58% died at home, 85% felt their relative died in the right place. 90% found bereavement care helpful. Qualitative themes included importance of working collaboratively with external services and to establish relationships; staff taking into account family and social context; and a non-hierarchical dynamic across professional staff, volunteers and family members and a willingness to learn. | X | X | X | X | |

|

Nordly et al. 2019 [27] Denmark |

Patients were randomised to either a systematic fast-track transition from oncological treatment to home-based specialised palliative care reinforced with a dyadic psychological intervention plus standard cancer care or standard cancer care plus on-demand specialized palliative care | 340 patients | Findings indicated that the intervention had no effect on time spent at home or place of death. However, the intervention resulted in some improvement in quality of life, social functioning and emotional functioning after 6 months. | X | X | |||

|

Tan, Woan Shin et al. 2016 [28] Singapore |

Retrospective study of two cohorts - intervention group and historical comparison group | 321 patients | Hospital deaths were significantly lower for programme participants. The intervention group had significantly lower emergency department visits at 30 days, 60 days and 90 days prior to death. Similar results were found for the number of hospitalisations at 30 days, 60 days and 90 days prior to death, demonstrating that integrating services between acute care and home hospice care could reduce acute care service usage. | X | X | X | X | |

|

von Heymann-Horan et al. 2018 [29] Denmark |

Randomised control trial of home-based specialist palliative care, known as the Domus model - reporting on feasibility and acceptability | 441 (251 patients, 190 caregivers) | Integration of psychological support sought to facilitate patients chances of receiving care and dying at home, by alleviating distress in patients and caregivers. Enrolment in the trial and uptake of the intervention indicated it was acceptable to patients and caregivers. The intervention focussed on dyads, psychological distress, and existential concerns, multidisciplinary collaboration and psychological interventions offered according to need. | X | X | X | X | |

|

Zemplenyi et al. 2020 [30] Hungary |

Documentary and qualitative interviews with stakeholders - to understand how stakeholders think about key features using content analysis | 17 (4 managers, 3 physicians, 4 HCP, 4 informal, 2 patients) | Integrated, multidisciplinary and patient-centred care approach was well-received, with an increasing number of requests for consultations. From the patient pathway management across providers (e.g. from inpatient care to homecare) a higher level of coordination could be achieved in continuity of care for seriously-ill patients. However, the regulatory framework to integrate this has only partially been established. | X | X | X | ||

|

Kerin Adelson et al. 2017 [31] USA |

Prospective cohort study with an advanced solid tumour, prior hospitalization within 30-day, hospitalisation of 7 or more days, or active symptoms. Patients who met the criteria received automatic palliative care consultation. |

Preintervention (48 patients) Intervention (65 patients) |

Intervention group had increased palliative care consultations and hospice referrals, with declines in 30-day readmission rates and receipt of chemotherapy after discharge. Overall increase in support measures following discharge. Length of stay was unaffected. | X | X | X | X | X |

Key

Component 1: Identification of palliative care needs

Component 2: Compassionate communication with the patient and family members

Component 3: Collaborative effort to establish a multi-dimensional treatment plan

Component 4: Review and evaluation of the treatment plan

Component 5: Identification of the end of life phase

Evidence for individual components

Component 1: identification of palliative care needs

One study [30] identified reasons for requesting a palliative care consultation including: discharging patients to home, hospice-palliative care, transferring patients to an inpatient hospice institution or providing palliative care at the ward (pain relief, management of other symptoms or providing psychosocial support). This highlights the most common points of identification during the patient’s journey, which could be used when implementing transition models. This care service [30] focused on a person-centred approach to palliative care. Therefore, when done appropriately, identification of palliative care needs involves reporting on the disease state, physical and mental condition of the patient, pain and other symptoms, and should also include social, spiritual and cultural aspects. Another model screened patients during their oncological treatment, looking at early identification of patients with incurable cancer and limited or no cancer treatment options [29]. Using standardised criteria as triggers for a palliative care consultation was found to decrease re-admission rates and increase hospice referrals, and support following discharge for patients with an advanced solid tumor [31].

Component 2: compassionate communication with the patient and family members

Some of the studies which relate to compassionate communication, often include those which detail collaborations with the patient and their family. For example, when physicians are assessing the patient’s symptoms, they will discuss the expectations of the patient and their family members regarding their care. This involves listening to how well they understand the disease and its prognosis [30]. A psychological model [29] which was highly focussed on support, communication and mutual understanding, helped patients and their family members to cope with managing cancer. This was not purely focussed on the patient but on both the patient and family caregiver, to address their concerns and allow for individual support sessions where needed [29].

Component 3: collaborative effort to establish a multi-dimensional treatment plan

The involvement of patients in the treatment plan and care process is based on the preferences of the patients [30]. Models were described as using a patient-centred approach to treatment planning, which sometimes involved an multidisciplinary conference about home care including palliative care team, nurses, primary care physician and psychologist where palliative care needs were discussed, and a care plan was created [29]. This multidisciplinary aspect has the potential to be beneficial to patients and families and allows flexibility in care planning, based on the patient’s individual needs [29], however this was not tested in practice.

Component 4: review and evaluation of the treatment plan

One transition model [16] involved a team of medical professionals (medical doctors, nurse practitioners and registered nurses) from both the hospital and community, who communicated regularly to co-manage their patients with their oncology and primary care teams, to review patient’s treatment plans. The diverse clinical and interpersonal skillsets of this approach allowed tasks to be delegated to manage time-sensitive patient situations and crises as they occurred [19]. Another model had a psychology focus, with psychologists assessing patient’s needs monthly, they also collaborated with nurses and physicians based on the patient’s needs [29]. This allowed continual assessment and collaboration, which captured the dynamically changing nature of patient’s palliative care needs [29].

Component 5: identification of the end-of-life phase

The transition model [19] using ‘community bridge’ teams including both hospital and community healthcare professionals co-managing patient’s needs, were described as crisis managers. They often visited patients who they recognised were dying. Due to their good relationship with these patients built through collaboration in creating and reviewing their treatment, they were able to make appropriate and efficient changes to their care, often involving urgent home hospice referrals. A programme integrating outpatient palliative care into cancer care services demonstrated decreased hospitalisation at the end of life, and increased hospice utilization and length of stay, improving end of life care [18].

Facilitators of transitions and evidence for multiple and or consecutive components

Transition components were often poorly described across included studies. However, where described in a good level of detail, use of transition models resulted in increases in palliative care consultations, hospice referrals and reduction in 30-day hospital readmission rates [31] increasing the possibility of providing end-of-life care at home [19]. There is also evidence for transition models resulting in greater emotional and spiritual support of patients and families [27]. It is clear that there is no uniform model, and the specific configuration and composition of the transition model depends on the healthcare system where it is implemented. This may have implications for referral pathways.

Where there is a good level of reporting of multiple transition components within a model, there are insights into key facilitators, good practices and outcomes. Firstly, implementing multiple transition components requires coordination and collaboration between professional groups and services – commonly including physicians, nurses, but also social workers [31], physiotherapists and occupational therapists [23]. Coordination and collaboration facilitate working relationships [26], transition management and helps to navigate healthcare systems in a manner that is consistent with goals of care and available resources [22]. Noble et al. [26] highlight how a non-hierarchical dynamic across all professional groups and a willingness to learn from each other are key facilitators. Furthermore, the importance of ownership and oversight provided by a key person was highlighted, for example, by nurse-led case management to promote continuity and access to services as needed [28].

Linked to multidisciplinary working, communication was also reported to be key [25, 28]. Others highlight how poor communication created challenges for multidisciplinary working, and this was cited as a particular challenge in the context of services based in rural locations [20]. Such is its importance; some studies highlight the role of training and education in communication [22].

One commonly cited mechanism of communication was accessible information throughout the process [22] and for all involved. There is evidence of this including accessible information to professionals based on patient’s goals of care and advance care plans [28, 31]. In one instance, this included using patient-held medical records and advance care plans in electronic records accessible to relevant professional groups [22].

Discussion

Collaboration, coordination and communication as key facilitators and mechanisms

Collaboration, coordination and communication are the key concepts of Pal-Cycles, as once palliative care needs have been identified (Pal-Cycles component 1), there is emphasis on ensuring compassionate communication with patients and family (Pal-Cycles component 2) throughout the transition process, including end-of-life discussions in the terminal phase (Pal-Cycles component 5). There is also a large focus on collaboration and co-ordination when creating a care plan, including multidisciplinary input, and also involving the patients and family (Pal-Cycles component 3). This is also the case when healthcare professionals review the plan with the patient (Pal-Cycles component 4). Collaboration and coordination are key elements during the end-of-life phase (Pal-Cycles component 5), when considering patient and family wishes at the end of life, which may involve multidisciplinary collaboration when considering things like spiritual needs alongside social, physical and psychological. These three elements to ensure patient-centred care, as multidisciplinary collaboration enables all healthcare professionals involved to understand the care plan and give consistent information to the patient and family members, to ensure they feel supported by the whole care team and can build up a level of trust and understanding [32].

Collaboration, coordination and communication were commonly cited as facilitators of transition models, and this has implications for multidisciplinary working in healthcare systems where palliative care provision may not be fully integrated or may be considered to work in silos with little pre-existing coordination and collaboration between professional groups [33]. Alongside the importance of collaboration, coordination and particularly communication, some include training and education as a key component, though there is little reported on the design of these development opportunities.

It is important to note that collaboration, coordination and communication does not just focus on professional providers, but also patients and families. Accessible information is a key mechanism for patients and families. This can promote involvement in developing goals of care that reflect their preferences and wider sense of empowerment and control, and given their importance, may be regarded as three major facilitators of transitional models. Though there are clear gaps in the evidence base, these facilitators of transition models are consistent with recent revised EAPC Norms and Standards for Palliative Care across Europe [3]. Specifically, it has been agreed that integrated multidisciplinary networks, collaboration, coordination and accessible information are important to enable people to receive care and die at home if they so wish [3]. However, based on this review, there is a need to examine practice, implementation and research in these areas.

Effective transition models as indicators of person-centred care

Taking this body of literature as whole, it is apparent that effective transition models are an indicator and perhaps, even a central pillar of person-centred care. Earlier in this paper we highlighted how person-centred care requires fast access to reliable advice, effective treatment, clear information, communication and support, involvement in decisions and respect for preferences, involvement and support for family and carers, emotional support, empathy and respect and attention to physical and environmental needs [1–3, 5, 6]. Many of these areas are apparent in the literature, many explicitly as being central features of transitions models.

Collaboration, coordination and communication between multidisciplinary teams and patients and families, underpins and acts as a thread through these transitional elements. Some highlight communication, and also relationships, as being central to person-centred care [1].

Eight of the fourteen studies present evidence for at least four of the components described. Only two studies have a focus on all five components, both from the USA. The first four components are presented in four studies, one in Singapore and three in Europe (Denmark, Norway and Sweden). This is of interest because it suggests that models with a focus on care transitions with advanced cancer that are subject to research in Europe may not adequately focus on the identification of the terminal phase and establish preferences around treatment, place of death, legal and culturally sensitive issues. Evidence in this vital area that can facilitate or present a barrier to high quality care coordination, transitions and home care is therefore underdeveloped. The extent with which evidence is mixed also suggests there may be issues with developing sustainable approaches to embedding transition models into routine practice, with this being cited as an issue in some less developed healthcare systems [30].

Two studies from, the UK [26] and Japan [25] evidence the final four components, although not the first component. Given the focus on care transitions for patients with advanced cancer, and that studying this issue will invariably have meant identifying patients at some stage, it may be that identifying a patient at hospital discharge with palliative and supportive care needs was not explicitly part of the study but was part of the model. However, equally it is ultimately unclear when patients in these studies were identified as having palliative and supportive care needs. Not including or adequately focusing on the first stage suggests that the authors are either not reporting this step or are not adequately integrated in order to identify patients at discharge from across their respective healthcare systems.

Despite this inconsistent evidence base, there is some evidence of transition models having beneficial outcomes. However, successful implementation cannot be considered straightforward and must consider the specific nuances of local healthcare systems.

Strengths and limitations

This review provides an overview of literature related to transitions in care, and the five components of the Pal-Cycles programme, for advanced cancer patients with palliative care needs. The current review has highlighted that research on transition models is mixed and often unclear and uncomprehensive due to inconsistent reporting. However, it is possible to synthesize and present some interesting and informative findings that are mostly based on research published since 2015.

Through using a scoping review method, no formal quality appraisal method was applied during record selection. However, the Hawker et al. [16] quality appraisal method was used when assessing completeness of information. Furthermore, this review only included records that were in English language. The current review also identified many records which related to one of the components described, however these were excluded as they did not provide sufficient relevant detail to answer review aims.

Implications for practice and opportunities for further research

Teams tasked with establishing and implementing transitions in care should think about how to develop and maintain collaboration, coordination and communication as central pillars of their practice and transition pathways. This is likely to require careful planning and be tailored to the specifics of each healthcare system. Furthermore, high quality and accessible information is important for all professional, patient and family stakeholders. It is highly likely that what constitutes high quality information will vary, be dependent on stakeholder group, and making this accessible for all within a transitional model will likely come with challenges. It is important that these elements are implemented appropriately, aligning with the Picker Principles [6] of person-centred care.

Further research should aim to develop the evidence base further using implementation research to test models in practice. Another avenue for further research is to implement and deliver a transitions model across different countries in order to begin to compare and learn about some of the mechanisms, barriers and facilitators that are highlighted in this paper across different cultures, countries and healthcare systems. The Pal-Cycles project seeks to address some of these gaps.

Conclusion

This scoping review, focussed on the components of the Pal-Cycles programme, has found evidence that collaboration, coordination and communication are central mechanisms for transitional models for patients with advanced cancer. Existing evidence for transitions models is far from comprehensive and, given this is an emerging field, there is a need for further research is this area.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Review supported by John Barbrook, Specialist Librarian, Lancaster University.

Author contributions

JH, SP, NP designed the study. RH, SP, DB, JEC-M, AH and NP conducted the scoping review and analysed data. RH, SP, JEC-M, AH and NP contributed to writing the manuscript. JH is the funded project lead. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The Pal-Cycles project is funded by the Horizon Europe programme of the European Union grant agreement number 101057243. Horizon Europe Guarantee UKRI Reference Number: 10038822.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The search string which is presented in the appendices.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was not required for this study, as no participants were recruited.

Consent for publication

No consent for publication was necessary, as no individual person’s data is presented.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.WHO. Palliative care. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/palliative-care. Published 2024. Accessed June 6, 2024.

- 2.McCormack B, van Dulmen S, Eide H, Skovdahl K, Eide T. Person-centredness in healthcare policy, practice and research. Pers Healthc Res. 2017:3–17. 10.1002/9781119099635.CH1

- 3.Payne S, Harding A, Williams T, Ling J, Ostgathe C. Revised recommendations on standards and norms for palliative care in Europe from the European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC): a Delphi study. Palliat Med. 2022;36(4):680–97. 10.1177/02692163221074547/ASSET/IMAGES/LARGE/10.1177_02692163221074547-FIG1.JPEG 10.74547/ASSET/IMAGES/LARGE/10.1177_02692163221074547-FIG1.JPEG [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vahdat S, Hamzehgardeshi L, Hessam S, Hamzehgardeshi Z. Patient involvement in health care decision making: a review. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2014;16(1):12454. 10.5812/IRCMJ.12454 10.5812/IRCMJ.12454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCormack B, McCance T. The person-centred nursing framework. Pers Nurs Res Methodol Methods Outcomes. 2021:13–27. 10.1007/978-3-030-27868-7_2

- 6.Picker. The picker principles of person centred care. https://picker.org/who-we-are/the-picker-principles-of-person-centred-care/. Published 2023. Accessed June 6, 2024.

- 7.den Herder-van, der Eerden M, Hasselaar J, Payne S, et al. How continuity of care is experienced within the context of integrated palliative care: a qualitative study with patients and family caregivers in five European countries. Palliat Med. 2017;31(10):946–55. 10.1177/0269216317697898/ASSET/IMAGES/LARGE/10.1177_0269216317697898-FIG1.JPEG 10.1177/0269216317697898/ASSET/IMAGES/LARGE/10.1177_0269216317697898-FIG1.JPEG [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanratty B, Lowson E, Grande G, et al. Transitions at the end of life for older adults – patient, carer and professional perspectives: a mixed-methods study. Heal Serv Deliv Res. 2014;2(17):1–102. 10.3310/HSDR02170 10.3310/HSDR02170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hui D, Nooruddin Z, Didwaniya N, et al. Concepts and definitions for actively dying, end of life, terminally ill, terminal care, and transition of care: a systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;47(1):77. 10.1016/J.JPAINSYMMAN.2013.02.021 10.1016/J.JPAINSYMMAN.2013.02.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Siouta N, Van Beek K, Van Der Eerden ME, et al. Integrated palliative care in Europe: a qualitative systematic literature review of empirically-tested models in cancer and chronic disease. BMC Palliat Care. 2016;15(1):1–16. 10.1186/S12904-016-0130-7/TABLES/3 10.1186/S12904-016-0130-7/TABLES/3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Payne SA, Hasselaar J. Exploring the concept of transitions in advanced cancer care: the European Pal_Cycles project. J Palliat Med. 2023;26(6):744–5. 10.1089/JPM.2023.0149 10.1089/JPM.2023.0149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peterson J, Pearce PF, Ferguson LA, Langford CA. Understanding scoping reviews: definition, purpose, and process. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2017;29(1):12–6. 10.1002/2327-6924.12380 10.1002/2327-6924.12380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73. 10.7326/M18-0850/SUPPL_FILE/M18-0850_SUPPLEMENT.PDF 10.7326/M18-0850/SUPPL_FILE/M18-0850_SUPPLEMENT.PDF [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73. 10.7326/M18-0850 10.7326/M18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hawker S, Payne S, Kerr C, Hardey M, Powell J. Appraising the evidence: reviewing disparate data systematically. http://dx.doi.org/101177/1049732302238251. 2002;12(9):1284–99. 10.1177/1049732302238251 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A et al. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews a product from the ESRC methods programme peninsula medical school, Universities of Exeter and Plymouth. 2006.

- 18.Blackhall LJ, Read P, Stukenborg G, et al. CARE track for advanced cancer: impact and timing of an outpatient palliative care clinic. https://home.liebertpub.com/jpm. 2015;19(1):57–63. 10.1089/JPM.2015.0272 10.1089/JPM.2015.0272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Calton BA, Thompson N, Shepard N et al. She would be flailing around distressed: the critical role of home-based palliative care for patients with advanced cancer. https://home.liebertpub.com/jpm 2017;20(8):875–8. 10.1089/JPM.2016.0354 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Casotto V, Rolfini M, Ferroni E, et al. End-of-life place of care, health care settings, and health care transitions among cancer patients: impact of an integrated cancer palliative care plan. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;54(2):167–75. 10.1016/J.JPAINSYMMAN.2017.04.004 10.1016/J.JPAINSYMMAN.2017.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duffy AP, Bemben NM, Li J, Trovato J. Facilitating home hospice transitions of care in oncology: evaluation of clinical pharmacists’ interventions, hospice program satisfaction, and patient representation rates. 2018;35(9):1181–1187. 10.1177/1049909118765944 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Malmström M, Klefsgård R, Johansson J, Ivarsson B. Patients’ experiences of supportive care from a long-term perspective after oesophageal cancer surgery – A focus group study. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2013;17(6):856–62. 10.1016/J.EJON.2013.05.003 10.1016/J.EJON.2013.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johansen ML, Ervik B. Talking together in rural palliative care: a qualitative study of interprofessional collaboration in Norway. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22(1):1–9. 10.1186/S12913-022-07713-Z/TABLES/3 10.1186/S12913-022-07713-Z/TABLES/3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ko W, Deliens L, Miccinesi G, et al. Care provided and care setting transitions in the last three months of life of cancer patients: a nationwide monitoring study in four European countries. BMC Cancer. 2014;14(1):1–10. 10.1186/1471-2407-14-960/TABLES/4 10.1186/1471-2407-14-960/TABLES/4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murakami N, Tanabe K, Morita T, et al. Process evaluation of the regional referral clinical pathway for home-based palliative care and outreach program: a questionnaire survey of the medical staff and bereaved families. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2022;39(9):1029–38. 10.1177/10499091211055901/SUPPL_FILE/SJ-PDF-2-AJH-10.1177_10499091211055901.PDF 10.55901/SUPPL_FILE/SJ-PDF-2-AJH-10.1177_10499091211055901.PDF [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Noble B, King N, Woolmore A, et al. Can comprehensive specialised end-of-life care be provided at home? Lessons from a study of an innovative consultant-led community service in the UK. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2015;24(2):253–66. 10.1111/ECC.12195 10.1111/ECC.12195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nordly M, Skov Benthien K, Vadstrup ES et al. Systematic fast-track transition from oncological treatment to dyadic specialized palliative home care: DOMUS – a randomized clinical trial. 2018;33(2):135–49. 10.1177/0269216318811269 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Tan WS, Lee A, Yang SY et al. Integrating palliative care across settings: a retrospective cohort study of a hospice home care programme for cancer patients. 2016;30(7):634–41. 10.1177/0269216315622126 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Von Heymann-Horan AB, Puggaard LB, Nissen KG, et al. Dyadic psychological intervention for patients with cancer and caregivers in home-based specialized palliative care: the Domus model. Palliat Support Care. 2018;16(2):189–97. 10.1017/S1478951517000141 10.1017/S1478951517000141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zemplényi AT, Csikós Á, Csanádi M, et al. Implementation of palliative care consult service in Hungary-integration barriers and facilitators. BMC Palliat Care. 2020;19(1):1–12. 10.1186/S12904-020-00541-0/FIGURES/5 10.1186/S12904-020-00541-0/FIGURES/5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adelson K, Paris J, Horton JR, et al. Standardized criteria for palliative care consultation on a solid tumor oncology service reduces downstream health care use. J Oncol Pract. 2017;13(5):e431–8. 10.1200/JOP.2016.016808/ASSET/IMAGES/LARGE/JOP.2016.016808APP1.JPEG 10.1200/JOP.2016.016808/ASSET [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dahlke S, Hunter KF, Reshef Kalogirou M, Negrin K, Fox M, Wagg A. Perspectives about interprofessional collaboration and patient-centred care. Can J Aging / La Rev Can du Vieil. 2020;39(3):443–55. 10.1017/S0714980819000539 10.1017/S0714980819000539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brown R, Chambers S, Rosenberg J. Exploring palliative care nursing of patients with pre-existing serious persistent mental illness. Prog Palliat Care. 2019;27(3):117–21. 10.1080/09699260.2019.1619964 10.1080/09699260.2019.1619964 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The search string which is presented in the appendices.