Abstract

Panax notoginseng and Panax quinquefolium are important economic plants that utilize dried roots for medicinal and food dual purposes; there is still insufficient research of their stems and leaves, which also contain triterpenoid saponins. The extraction process was developed with a total saponin content of 12.30 ± 0.34% and 12.19 ± 0.64% for P. notoginseng leaves (PNL) and P. quinquefolium leaves (PQL) extracts, respectively. PNL and PQL saponin extracts showed good antioxidant, antihypertensive, hypoglycemic, and anti-inflammatory properties in vitro and RAW264.7 cells. A total of 699 metabolites were identified in PNL and PQL saponin extracts, with the majority being triterpenoid saponins, flavonoids and amino acids. Fourteen ginsenosides, 18 flavonoids or alkaloids, and 16 amino acids were enriched in both saponin extracts. Overall, the utilization of saponins from medicinal plants PNL and PQL has been developed to facilitate systematic research in the functional food and natural product industries.

Keywords: Antihypertensive, Anti-inflammatory, Antioxidant, Panax notoginseng, Panax quinquefolium, Triterpenoid saponin

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Panax notoginseng and Panax quinquefolium leaves are rich in bioactive metabolites.

-

•

Experiment optimized the extraction process of saponin extract from P. notoginseng and P. quinquefolium leaves.

-

•

Saponin extract showed bioactive in vitro and in proinflammatory RAW 264.7 cell.

-

•

Experiment analyzed bioactive metabolites in saponin extract by metabolomics and HPLC.

1. Introduction

Members of the Panax genus from the Araliaceae family are commonly used in traditional herbal medicines. Their dried roots contain multiple bioactive ingredients, including triterpenoid saponins, flavonoids, amino acids, volatile oils, polyacetylenes, polysaccharides, and other constituents (Liu, Lu, et al., 2020; Liu, Xu, & Wang, 2020). Among them, Panax notoginseng and Panax quinquefolium are predominately distributed in eastern Asia and northern America (Wang et al., 2022;). Panax quinquefolium Radix, an important medicinal plant, has vasodilatory, antioxidant, antihyperlipidemic, angiogenic, anti-inflammatory, antiangiogenetic, and antiviral activities (Zheng et al., 2022); it is widely used to treat diseases of the nervous and immune systems (Yang et al., 2021). The medical use of P. notoginseng has >400 years of history (Mancuso & Santangelo, 2017). P. notoginseng and P. quinquefolium are now widely used throughout the world and recognized globally as important resources for traditional medicines and functional foods.

The non-medicinally utilized parts, namely, P. notoginseng leaves (PNL) and P. quinquefolium leaves (PQL), are also rich in bioactive ingredients, especially triterpenoid saponins and flavonoids. According to previous reports, the saponin contents of PNL and PQL are higher than those of the roots (Zhang et al., 2021). About 226 ginsenosides comprising mostly Ra2, Rb2, Rb3, Rc, and notoginseng Fa have been identified in PNL (Cao et al., 2019). Therefore, extracting saponins from by-products of traditional Chinese medicine shows promise as a cost-effective approach. In recent years, several products have been developed using stems and leaves of P. notoginseng, e.g., raw materials for local foods of Yunnan Province, China, P. notoginseng stem-leaf tea (Cai et al., 2021), fermented foods (Yang et al., 2022) and instant beverages (Liang et al., 2023). Furthermore, PQL is used to prepare rare ginsenosides, such as Rh1, Rg3, Rh2, and compound K (Xiao et al., 2019). PQL has a total saponin content of 12.62%, which comprises mostly ginsenosides Rb1, Rb2, Rb3, Rd, Re, Rg1, Rg2, Rg3, PF11, Rh1, F2 and pseudoginsenoside RT5 (Chen et al., 1981). As a result, PQL has been considered as a possible source of pro-health bioactive phytochemical and function food ingredients (Szczuka et al., 2019). However, there are few reports on the extraction technology for saponins from PNL and PQL. In addition, the metabolite composition and biological activity of PNL and PQL saponins is unclear, thus necessitating further research.

Saponins are a broad category of complex compounds extensively distributed in the plant kingdom. They are distinguished by their characteristic structure, which contains a triterpene or steroid aglycone combined with one or more sugar chains and have been known for >80 years (Campbell & Peerbaye, 1992). Because of their diverse physicochemical and biological characteristics, saponins are utilized in various conventional and industrial applications such as soaps, surfactants, functional foods, drugs, cosmetics, and the pharmaceutical industry (Zhang et al., 2023). Growing evidence of their biological activity, such as anticancer, hemolytic, and hypocholesterolemic properties, has led to their commercial significance in response to consumer demand for functional foods (Zeng et al., 2022). Currently, there are two different methods for obtaining saponins: one involves finding and altering functional genes and using microbes to generate saponins, and the other involves extracting and preparing saponins from natural plant materials (Mohanan et al., 2023). While saponins are well-known for their beneficial effects on health and functional properties, their use is nevertheless restricted by the high expense of removing and processing them from natural plant sources.

In this study, we optimized the extraction process of PNL and PQL saponins. We then analyzed the antioxidant, antihypertensive, hypoglycemic, and anti-inflammatory activity of the extracted saponins in vitro and in proinflammatory RAW264.7 cells. On the basis of these findings, metabolomic techniques were used to analyze the chemical composition of the PNL and PQL saponin extracts. The content of monomeric saponins, flavonoids or alkaloids, and amino acids in the PNL and PQL saponin extracts were determined using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). This study aimed to provide systematic research on the industrial utilization of PNL and PQL in the field of function food, which are well-known by-products of traditional Chinese medicine.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Single-factor selection of technological parameters for saponin content of PNL and PQL extracts

The total saponin contents of PNL and PQL were detected by UV–Vis spectrophotometry based on colorimetric 5% vanillin–perchloric acid–77% sulfuric acid aqueous solution reaction at 548 nm (Zhang & Huang, 2018). The samples were extracted in three replicates, and their extracts were analyzed twice each. The content of total saponin was calculated by Eq. 1. To prepare saponin extracts from PNL and PQL, this study optimized stable extraction technologies using a combination of single-factor and response surface methodology (SF-RSM) to prepare total saponins from PNL and PQL, respectively. In brief, in each single-factor experiment, 1 g of samples was extracted using a single-factor experiment including ethanol concentrations of 0%, 20%, 40%, 60%, 80%, and 99.70% (v/v); solid-liquid ratios of 1: 5, 1: 10, 1: 15, 1: 20, 1: 25, and 1: 30 (g: mL); and extraction times of 12, 24, 36, 48, 60, and 72 h.

| (1) |

2.2. Response surface methodology design and analysis

The saponin extraction rates of PNL and PQL were influenced by three main factors using single-factor experiments. These factors were ethanol concentration (A), solid–liquid ratio (B), and extraction time (C). These variables were chosen as independent variables to optimize the saponin extraction process parameters. A three-factor, three-level Box–Behnken design (BBD) model was developed using Design Expert® software (https://www.statease.com/software/design-expert). The model includes factors such as ethanol concentration, solid–liquid ratio, and extraction time. For PNL, the optimal extraction system chosen had ethanol concentrations of 20% (−1), 40% (0), and 60% (+1); solid–liquid ratios of 1:20 (−1), 1:25 (0), and1:30 (+1); and extraction times of 40 h (−1), 56 h (0), and 72 h (+1). As for PQL, the optimal extraction system chosen had ethanol concentrations of 0% (−1), 20% (0), and 40% (+1); solid–liquid ratios of 1:15 (−1), 1:20 (0), and 1:25 (+1); and extraction times of 36 h (−1), 48 h (0), and 60 h (+1). The saponin extraction rates of PNL and PQL were used as the response value. The BBD model comprises 17 randomized runs with five replicates as the center points and proposes a predictive extraction process (Table S1, S2). The response surface 3D contour maps showed the interaction effects of experiment factors A, B, and C (Fig. S1). Consequently, we verified the reliability through demonstration tests and finally established the final saponin extraction process for PNL and PQL.

2.3. Antioxidant activity

The antioxidant activities of PNL and PQL saponin extracts were evaluated in vitro. The scavenging capacities for DPPH and ABTS free radicals, as well as total antioxidant capacity (TAC) of PNL and PQL saponin extracts, were determined using commercial kits (Grace Biotechnology Co. Ltd., Suzhou, China) according to the manufacturer's instructions, and Trolox solution was used as the positive control. The half-maximal inhibitory concentrations (IC50) for the scavenging activities were analyzed to evaluate the antioxidant activities. The scavenging rates of ABTS and DPPH free radicals and the TAC were calculated by Eq. 2, Eq. 3, and Eq. 4 respectively.

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

In Eqs. (2), (3), (4), AS is the absorbance value of the PNL and PQL saponin extract group, AC is the absorbance value of control groups, AB is the absorbance value of blank groups, W is the weight of PNL and PQL saponin extract samples, and D is the dilution ratio, with undiluted being 1-fold.

2.4. In vitro assays of ACE inhibition activity

The ACE inhibition experiment adopted an ELISA-based double antibody one-step sandwich kit. Samples (PNL and PQL saponin extracts), standards, and horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-labeled test antibodies were added to the coated wells, which were pre-coated with ACE antibodies, incubated for 60 min, and washed thoroughly. The chromogenic substrate 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) was used for color development; TMB turns blue under the catalysis of peroxidase, and then yellow under the action of acids. The depth of color in the solutions was positively correlated with the ACE inhibitor in the samples. The absorbance (OD value) was read with a microplate reader at a wavelength of 450 nm, and the rates of ACE inhibition in PNL and PQL saponin extracts were calculated. All measurements were conducted according to the manufacturer's instructions, and the ACE inhibition rate was calculated by Eq. 5.

| (5) |

AS is the absorbance treated by PNL and PQL saponin extracts, and AB is the absorbance of the reagent blank group.

2.5. Inhibition capacity of α-glucosidase activity

α-Glucosidase activity is one of the key indicators affecting glycemic index. In this study, the inhibitory abilities of PNL and PQL saponin extracts for α-glucosidase were investigated to examine the hypoglycemic activities of the two samples, with acarbose used as the positive control. The experiments included a sample processing group (AS), a sample blank group (ASB), a control group (AC), and a reagent blank group (AB). In brief, PNL and PQL saponin extracts were dissolved in PBS at pH 6.8. The concentrations used were 0.04, 0.08, 0.16, 0.31, 0.63, 1.25, 2.50, and 5.00 mg/mL. First, we transferred 100 μL of PNL and PQL saponin extract solutions at each concentration separately, added 50 μL (10 mmol/mL) of 4-nitrophenyl-β-D-glucopyranoside PBS solution, placed the mixture in a 96-well ELISA plate, and incubated it at 37 °C for 25–30 min. Second, 5 μL of α-glucosidase PBS solution (27.3 units/mL) was added to the sample processing group, which was then placed in a constant-temperature incubator and allowed to react fully for 1 h at 37 °C. Finally, 50 μL of Na2CO3 solution (1 mol/L) was added to each plate to stop the reaction. We then placed the ELISA plate on an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay reader and measured the absorption values at a wavelength of 405 nm. The inhibition rate of α-glucosidase on PNL and PQL saponin extracts was calculated using Eq. 6:

| (6) |

In Eq. (6), AC is the control group, AB is the reagent blank group, AS is the sample processing group, and ASB is the sample blank group.

2.6. Anti-inflammatory assays

To evaluate cytotoxicity, PNL and PQL saponin extract aqueous solutions were used to feed RAW264.7 cells, and the cell viabilities were determined using methyl thiazolyl tetrazolium (MTT) colorimetric assay. In brief, the experimental process was as follows. The RAW264.7 cells were plated onto 24-well plates at a density of 2 × 104 cells per well and cultured for 24 h. Next, PNL and PQL saponin extract aqueous solutions at 0, 4, 20, 100, 500, and 1000 μg/mL were added into each well for 24 h to feed the cells. Subsequently, 20 μL of MTT (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) was added to each well, and the plates were incubated for 4 h at 37 °C. Next, 50 μL of hydrochloric acid was added into each well, and the plates were left for 10 min. The absorption values were measured using a microtiter plate reader (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) at a wavelength of 450 nm.

The levels of inflammatory cytokines were detected using an ELISA kit. In brief, RAW264.7 cells in the exponential phase were inoculated onto 24-well plates at 1 × 106 cells per well. They were then pre-treated with LPS at 10 μg/mL for 12 h. The amounts of proinflammatory cytokines released into the medium were assessed. Next, 10, 20, 40, 80, and 160 μg/mL of PNL and PQL saponin extract aqueous solutions were added to 24-well plates, and then cotreated with LPS for another 12 h. The supernatant was collected by centrifugation. The inhibition effects of the samples (PNL and PQL saponin extracts) on the release of cytokines TNF-α and IL-6 from RAW264.7 cells were evaluated using ELISA according to the manufacturer's recommendations (Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai). All experiments were performed in triplicate, and each repetition was analyzed twice. Values were expressed relative to that of vehicle-treated cells and normalized to 100%.

2.7. Metabolomic analysis of PNL and PQL saponin extracts

2.7.1. Sample preparation

Fifty-milligram aliquots of individual PNL and PQL saponin extracts sample were precisely weighed and then transferred to an Eppendorf tube. Afterward, 700 μL of extract solution (3:1 methanol/water ratio, precooled at −40 °C, containing internal standard) was added. After vortexing for 30 s, the samples were homogenized at 40 Hz for 4 min and sonicated for 5 min in an ice-water bath. Homogenization and sonication were repeated three times. At 4 °C, the samples were dissolved thoroughly with stirring overnight at 12,000 rpm for 15 min. They were centrifuged for 15 min at 12,000 rpm (RCF = 13,800 g, R = 8.6 cm). The supernatant was carefully filtered through a 0.22 μm microporous membrane. The Supernatants were diluted 10 times with a methanol/water mixture (3:1, v: v, containing internal standard) and vortexed for 30 s, and then transferred to 2 mL glass vials. Each sample was diluted to 50 mL and pooled as QC sample. All samples were kept at 80 °C until UHPLC-MS analysis was completed.

2.7.2. UHPLC–MS analysis

The UHPLC separation was performed using an ExionLC System (Sciex). The mobile phase A consisted of 1% formic acid in water, while the mobile phase B consisted of acetonitrile. The temperature in the column was fixed at 40 °C. The temperature of the autosampler was 4 °C, and the injection volume was 2 μL. The Sciex QTrap 6500+ (Sciex Technologies) was utilized for test development, with an ion spray voltage of +5500/−4500 V, curtain gas set at 35 psi, temperature maintained at 400 °C, and ion source gas 1 at 60 psi, ion source gas 2 at 60 psi, and DP of 100 V were typical ion source settings.

2.7.3. Data preprocessing and annotation

The Sciex Analyst Workstation Software (version 1.6.3) was used to collect and process MRM data. Using MS converter, we transformed files in the MS raw data (.wiff) format into TXT files. Peak detection and annotation were done using a custom R algorithm and database.

2.8. HPLC analysis of PNL and PQL saponin extracts

Fourteen triterpene saponins, namely, ginsenoside Rb1 (G-Rb1, compound CID: 9898279), ginsenoside Rb2 (G-Rb2, compound CID: 6917976), ginsenoside Rb3 (G-Rb3, compound CID: 12912363), ginsenoside Rg1 (G-Rg1, compound CID: 441923), ginsenoside Rg3 (G-Rg3, compound CID: 9918693), ginsenoside Rg5 (G-Rg5, compound CID: 11550001), ginsenoside CK (CK, compound CID: 9852086), ginsenoside Rh2 (G-Rh2, compound CID: 119307), notoginsenoside R1 (NG-R1, compound CID: 441934), notoginsenoside Fa (NG-Fa, compound CID: 75054973), notoginsenoside Fc (NG-Fc, compound CID: 75412556), notoginsenoside Fe (NG-Fe, compound CID: 90657714), and notoginsenoside Fd (NG-Fd, compound CID: 15574810) in PNL and PQL saponin extracts, were analyzed by HPLC (Agilent 1260, USA) according to our previously reported methods (Liang et al., 2022).

Eighteen flavonoids or alkaloids, namely, catechin (C, compound CID: 9064), gallic acid (GA, compound CID: 370), epicatechin (EC, compound CID: 72276), epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG, compound CID: 65064), epicatechin-3-gallate (ECG, compound CID: 65056), Gallocatechin (GC, compound CID: 65084), catechin gallate (CG, compound CID: 5276454), quercetin (Qc, compound CID: 5280343), theophylline (compound CID: 2153), epigallocatechin (EGC, compound CID: 72277), caffeic acid (CA, compound CID: 689043), gallocatechin gallate (GCG, compound CID: 5276890), taxifolin (compound CID: 439533), rutin (compound CID: 5280805), ellagic acid (compound CID: 5281855), myricetin (compound CID: 5281672), luteolin (compound CID: 5280445), kaempferol (compound CID: 5280863) were detected by HPLC (Agilent 1200, USA) according to our previously reported methods (Nian et al., 2019).

Furthermore, 17 amino acids, namely, alanine (Ala, compound CID: 5950), arginine (Arg, compound CID: 6322), aspartic acid (Asp, compound CID: 5960), cystine (Cys, compound CID: 67678), glutamic acid (Glu, compound CID: 33032), glycine (Gly, compound CID: 750), histidine (His, compound CID: 6274), isoleucine (Ile, compound CID: 6306), leucine (Leu, compound CID: 6106), serine (Ser, compound CID: 5951), threonine (Thr, compound CID: 6288), tyrosine (Tyr, compound CID: 6057), valine (Val, compound CID: 6287), methionine (Met, compound CID: 6137), phenylalanine (Phe, compound CID: 6140), proline (Pro, compound CID: 145742) and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA, compound CID: 119) were quantitatively analyzed by HPLC (Agilent 1200, USA) using previously reported methods (Zhao et al., 2013).

2.9. Data analysis

The data were analyzed using Statistical Software Package for Social Science version 26.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), and the results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (). The rapid identification of the main metabolites in PNL and PQL saponin extracts were carried out using https://app.rawgraphs.io. The results from the antioxidant activity and ELISA assays were analyzed and plotted using GraphPad Prism 8.3.0. Heat maps of the chemical ingredients were plotted with TB Tools v 0.068. P < 0.05 was statistically significant.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Single-factor experiments

To optimize the content of PNL and PQL saponin extracts, single-factor experiments including an ethanol concentrations of 0% (pure water), 20%, 40%, 60%, 80%, and 99.70% (absolute alcohol); solid–liquid ratios of 1:5, 1:10, 1:15, 1:20 1:25, and 1:30 (g: mL); and extraction times of 12, 24, 36, 48, 60, and 72 h (Fig. 1) were developed. As the ethanol concentration increased from 0% to 40%, the content of PNL saponin extract increased from 7.19% ± 0.96% to the highest value of 7.95% ± 0.60% and then decreased as the ethanol concentration increased (Fig. 1A). The content of PQL saponin extract was the highest at 8.50% ± 0.57% when the ethanol concentration was 0%, which was not significantly different from the content extracted using a 20% ethanol concentration (Fig. 1C). The content of PNL saponin extract significantly increased with the increase in solid–liquid ratio, which was raised from 1:5 to 1:30 (g/mL), and reached 5.36% ± 0.44% as the solid–liquid ratio reached 1:30, which was not significant with the content that was extracted at 1:20 and 1:25 ratios (Fig. 1B). For PQL, the content of saponin extract increased from 3.04% ± 0.90% to 5.19 ± 0.25% as the solid-liquid ratio was raised from 1:10 to 1:30 (Fig. 1E). The extraction time had significant effects on PNL from 12 h to 72 h, with the content of saponin extracts increasing from 3.62% ± 0.43% to 8.49% ± 0.16% (Fig. 1C). From 12 h to 72 h, it had significant effects on the PQL saponin extract content from 7.36% ± 0.64% to 12.14% ± 1.33% (Fig. 1F). According to the analysis by synthesis of the single-factor conditions, the optimal ethanol concentrations for PNL and PQL were 40% and 20%, the optimal solid–liquid ratio was 1:25 (g/mL), and the optimal extraction time was 60 h. The optimal extraction conditions for PNL and PQL saponins extract still need to be further optimized using RSM models.

Fig. 1.

Single-factor extraction process for PNL and PQL saponin extracts. (A–C) optimized content of PNL saponin extracts and (D—F) optimized content of PQL saponin extracts. Different letters indicate significant differences in PNL and PQL saponin extracts at the level of 95%.

3.2. RSM was used to optimize the content of PNL and PQL saponin extracts

According to the optimized extraction results of RSM, the contents of PNL saponin extract were 8.27%–9.75% (Table S1). Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed on the above regression model, and the results are presented in Table 1. The P-value for the PNL saponin extraction model was 0.0013, which indicates that the model was highly significant and could be used to monitor the optimization of saponin extraction technology. In the present study, the lack-of-fit P-value (0.12) was higher than 0.05 (not significant), which indicates that the regression model correctly modeled the experimental findings. In the regression model, the secondary terms A 2 and C 2 were highly significant (P < 0.01). According to a comparison of F-values, extraction time was found to be more important than ethanol concentration, and ethanol concentration was more important than solid–liquid ratio for PNL saponin extract content. Considering the results of this regression, it appears that the linear correlation is highly significant (P < 0.0001). Based on the established solvent system, this regression model could be used to analyze and predict PNL saponin extract content. Consequently, the regression eq. (Y) of PNL saponin extract content was fitted as Eq. 7:

| (7) |

Table 1.

ANOVA (Box–Behnken design matrix)-based optimization for the content of PNL and PQL saponin extracts.

| RSM based Optimization of PNL saponin extract content (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F-value | P-value | Differential test |

| Model | 3.39 | 9 | 0.3769 | 8.98 | 0.0043 | ** |

| A-Ethanol concentration | 0.1375 | 1 | 0.1375 | 3.28 | 0.1132 | |

| B-Solid-liquid ratio | 0.0090 | 1 | 0.0090 | 0.2144 | 0.6574 | |

| C-Extraction time | 0.0528 | 1 | 0.0528 | 1.26 | 0.2991 | |

| AB | 0.0047 | 1 | 0.0047 | 0.1127 | 0.7470 |  |

| AC | 0.0134 | 1 | 0.0134 | 0.3191 | 0.5898 | |

| BC | 0.0001 | 1 | 0.0001 | 0.0027 | 0.9598 | |

| A2 | 1.00 | 1 | 1.00 | 23.93 | 0.0018 | |

| B2 | 0.4585 | 1 | 0.4585 | 10.92 | 0.0130 | |

| C2 | 1.40 | 1 | 1.40 | 33.29 | 0.0007 | |

| Residual | 0.2938 | 7 | 0.0420 | |||

| Lack of Fit | 0.1190 | 3 | 0.0397 | 0.9079 | 0.5121 | not significant |

| Pure Error | 0.1748 | 4 | 0.0437 | |||

| Cor Total | 3.69 | 16 | ||||

| Fit Statistics | R2 = 0.9203, Adjusted R2 = 0.8178, Predicted R2 = 0.4093, Adeq Precision = 7.7577 | |||||

| RSM based Optimization of PQL saponin extract content (%) | ||||||

| Source | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F-value | P-value | Differential test |

| Model | 21.48 | 9 | 2.39 | 9.56 | 0.0035 | ** |

| A-Ethanol concentration | 0.1808 | 1 | 0.1808 | 0.7240 | 0.4230 | |

| B-Solid-liquid ratio | 0.0249 | 1 | 0.0249 | 0.0998 | 0.7613 | |

| C-Extraction time | 0.1044 | 1 | 0.1044 | 0.4180 | 0.5385 | |

| AB | 0.0266 | 1 | 0.0266 | 0.1067 | 0.7534 |  |

| AC | 0.0136 | 1 | 0.0136 | 0.0547 | 0.8218 | |

| BC | 0.6186 | 1 | 0.6186 | 2.48 | 0.1595 | |

| A2 | 4.04 | 1 | 4.04 | 16.20 | 0.0050 | |

| B2 | 7.34 | 1 | 7.34 | 29.39 | 0.0010 | |

| C2 | 7.02 | 1 | 7.02 | 28.10 | 0.0011 | |

| Residual | 1.75 | 7 | 0.2497 | |||

| Lack of Fit | 0.1165 | 3 | 0.0388 | 0.0952 | 0.9587 | not significant |

| Pure Error | 1.63 | 4 | 0.4078 | |||

| Cor Total | 23.23 | 16 | ||||

| Fit Statistics | R2 = 0.9248, Adjusted R2 = 0.8280, Predicted R2 = 0.8100, Adeq Precision = 7.9917 | |||||

Note. ** Highly significant (P < 0.01); * Significant (P < 0.05).

According to the response surface 3D maps between the variables, the interaction between A and C has the greatest impact on the PNL saponin extract content (Fig. S1). The response surface 3D map results were consistent with the results of ANOVA, and PNL saponin extract content had an important positive correlation with ethanol concentration and extraction time.

Because of the desirability of reducing the sample consumption and reagents in experiments, as a result of applying the BBD model to economic development and environmental protection requirements, we were able to determine the optimal factors. The BBD model suggests that the maximum value of PNL saponin extract content might reach 8.97% when A is 46.88%, B is 1:27.68 (g/mL), and C is 66.71 h. The reliability and accuracy of the model were verified in three duplicate experiments. Consequently, the PNL saponin extract content was 11.28% ± 0.84%. To further investigate the practical availability in industrial applications, 100 g of PNL was extracted using the methods suggested above. As a result, 44.56 ± 1.19 g of PNL saponin extract was obtained, with a PNL saponin extract content of 12.30% ± 0.34% (Table S1, Fig. S1A—C). This is in good agreement with the predicted values.

On another hand, the content of PQL saponin extract was 6.84%–10.76%, which was extracted by response surface BBD optimization model (Table S2). ANOVA provided information about the effect of independent parameters of the content of PQL saponin extract (Table 1). Furthermore, linear quadratic coefficients (A 2, B 2, and C 2) are highly significant (P < 0.01). A, B, and C are clearly related to the content of PQL saponin extract. These results could also be verified by analyzing the 3D response surfaces and contours in Fig. S1. It is worth mentioning that the P-value (0.9587) for “lack of fit” of the equation in this experiment is not significant, indicating that the equation matched properly with the test and could be used to analyze and predict the results of PQL saponin extract content. The order of factors affecting the saponin extraction rates from high to low is extraction time > solid–liquid ratio > ethanol concentration. Finally, PQL saponin extract content is the function response value (Y), which is related to variables encoded by the following second-order polynomial in Eq. 8:

| (8) |

Thus, as A is at 20.00%, B is at 1:20.00 (g/mL), and C is 48.00 h, it might be possible to achieve 9.93% saponin extract content by using the BBD model suggestion. Triplicate experiments were used to verify the model's reliability and accuracy. Consequently, PQL saponin extract content was 8.50% ± 0.26%. Furthermore, 100 g of PQL was extracted using the suggested method to investigate its practical availability in industrial applications. As a result, 43.53 ± 1.10 g of PQL saponin extract was obtained (Table S2, Fig. S1D—F), with 12.19% ± 0.64% of PQL saponin extract content, indicating good agreement between the results and the predictions.

3.3. Antioxidant and antihypertensive activities of PNL and PQL saponin extracts

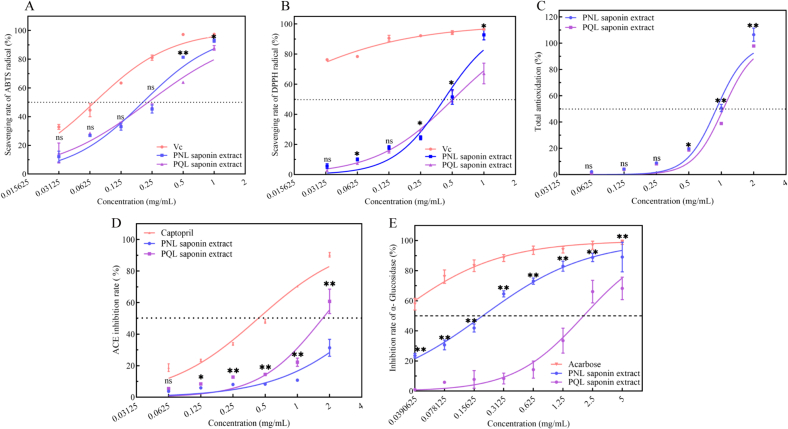

The free radical kits from ABTS, DPPH, and TAC were used to assess the antioxidant properties of PNL and PQL saponin extracts in vitro. In PNL and PQL saponin extracts (1.00 mg/mL), ABTS free radicals were scavenged at rates of 92.97% ± 1.15% and 87.93% ± 1.61% (P < 0.05), respectively, with IC50 of 0.20 and 0.23 mg/mL (Fig. 2A), respectively. Consequently, PQL saponin extract's ability to scavenge free radicals using ABTS was somewhat worse than that of PNL extracts. Within the dosage range of 0.03125–1.00 mg/mL, DPPH free radical scavenging increased in a dose-dependent manner for PNL and PQL saponin extracts (Fig. 2B); the IC50 for PNL and PQL extracts were 0.42 and 0.51 mg/mL (P < 0.05), respectively. Furthermore, the TAC of PNL and PQL saponin extracts at 1.00 mg/mL were 92.76% ± 3.30% and 67.13 ± 6.85% (P < 0.05), respectively. In addition, at a concentration of 2 mg/mL, the TAC of PNL and PQL saponin extracts were 106.52% ± 5.06% and 97.87% ± 50.93%, respectively (Fig. 2C), and they differed considerably (P < 0.05). Previous studies have verified that a number of flavonoids, ginsenosides, and polysaccharides are responsible for antioxidant activity in Panax genus (Kim et al., 2019).

Fig. 2.

Antioxidant, antihypertensive, and hypoglycemic capacity analysis of PNL and PQL saponin extracts. (A) Scavenging rate for ABTS free radical of PNL and PQL saponin extracts. (B) Scavenging rate for DPPH free radical of PNL and PQL saponin extracts. (C) Total antioxidant capacity analysis of PNL and PQL saponin extracts. (D) Inhibition rate of ACE I with PNL and PQL saponin extracts. (E) α-Glucosidase inhibitory activities of PNL and PQL saponin extracts. * indicates P < 0.05, ** indicates P < 0.01, and ns indicates no significant difference between PNL and PQL extracts with the paired sample t-test.

The antihypertensive properties of PNL and PQL saponin extracts were assessed in vitro using an ACE inhibition kit. At doses of 0.0625 to 2.00 mg/mL for PNL and PQL saponin extracts, the ACE inhibition rates rose in a dose-dependent manner. The ACE inhibition rate at doses of >0.25 mg/mL was substantially lower in PNL than in PQL saponin extracts (P < 0.05), with IC50 of 5.09 and 1.72 mg/mL, respectively (Fig. 2D). Therefore, PQL saponin extract inhibits ACE more effectively than PNL saponin extract. ACE inhibitors are a class of biologically active peptides that bind specifically to ACE, inhibiting angiotensin-I conversion to angiotensin-II and thus resulting in a decrease in blood pressure (Li et al., 2023). Previous reports have confirmed that ginsenoside Rb1 shows antihyperlipidemic effects in zebrafish (Li et al., 2020). Therefore, the ACE inhibition capacity of PNL and PQL saponin extracts are worthy of further research.

As the concentration of the sample increased from 0.04 mg/mL to 5.00 mg/mL, the inhibitory activities of the two samples on α-glucosidase activity increased in a dose-dependent manner. When the concentration of PNL saponin extract exceeded 0.15 mg/mL, the inhibitory rate of α-glucosidase activity approached 50%, with an IC50 of 0.19 mg/mL, which was significantly different from the inhibitory activity of PQL saponin extract at this concentration (P < 0.01) (Fig. 2E). As a representative medicinal plant of the Panax genus, the stems and leaves of P. notoginseng also show a hypoglycemic effect. Ginsenosides derived from the roots and rhizomes of P. ginseng inhibit α-glucosidase activity and show various hypoglycemic mechanisms (Wang et al., 2023). Thus, the PNL saponin extract, which contains bioactive ingredients similar to those of P. ginseng, shows significant promise in treating diabetes mellitus. As the concentration of PQL saponin extract exceeded 1.25 mg/mL, the inhibitory ability for α-glucosidase activity significantly increased, with an IC50 of 2.03 mg/mL, which was significantly different from that of PNL saponin extract (P < 0.01) (Fig. 2E). Previous research has confirmed that dammarane saponin from P. quinquefolius total saponins can inhibit α-glucosidase activity (Han et al., 2020). Thus, both samples extracted from P. notoginseng leaves and P. quinquefolius leaves are important resources for the treatment of diabetes mellitus.

3.4. Anti-inflammatory activities of PNL and PQL saponin extracts

In this experiment, RAW264.7 cell viability showed a significant upward trend upon treatment with PNL and PQL saponin extracts at concentrations of 0–10 μg/mL (Fig. 3A). As shown in previous studies, saponins from PQL ameliorate hepatotoxicity and enhance cell vitality (Xu et al., 2017). Similarly, P. notoginseng flower water extract significantly induces cell proliferation at 200–500 μg/mL, while G-Rh2 promotes RAW264.7 cell proliferation at a maximum concentration of 500 μg/mL (Ma et al., 2017). However, as the concentration of PNL and PQL saponin extracts exceeded 100 μg/mL, RAW264.7 cells growth were inhibited in a dose-dependent manner, and a significant difference compared to the control group was seen after 24 h (P < 0.01) (Fig. 3A), similar to a previous report of high doses of saponins exhibiting cytotoxic activity (Podolak et al., 2023).

Fig. 3.

Anti-inflammatory activities of PNL and PQL saponin extracts on pro-inflammatory RAW264.7 cells. (A) Effects of PNL and PQL saponin extracts on cell viability and (B) inhibition abilities of PNL and PQL saponin extracts on proinflammatory factor TNF-α. (C) Inhibition abilities of PNL and PQL saponin extracts on proinflammatory factor IL-6. Different letters indicate significant differences in the treatment effects of different concentrations of PNL and PQL saponin extracts (P < 0.05).

If RAW264.7 cells are stimulated physiologically, then they produce excessive amounts of the cytokines TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-10, which are linked with inflammation. LPS-treated cells significantly stimulated the production of IL-6 and TNF-α compared with the control groups after 24 h of culture (P < 0.001), whereas PNL and PQL saponin extracts significantly inhibited the production of TNF-α and IL-6 compared with the LPS-treated group. Specifically, PNL and PQL saponin extracts at 10 μg/mL suppressed TNF-α levels by 59.16% and 45.27%, respectively, while PNL and PQL saponin extracts at 20 μg/mL significantly inhibited TNF-α secretion by 59.28% and 53.28%, respectively (Fig. 3B). The comparison of positive inflammatory cytokine secretion from LPS-treated RAW264.7 cells revealed that the production IL-6 was inhibited at rates of 71.03% and 32.34% when the concentrations of PNL and PQL saponin extracts were 10 μg/mL, respectively. At 20 μg/mL, PNL and PQL saponin extracts inhibited IL-6 production at rates of 77.23% and 77.61%, respectively. At 40 μg/mL, PNL and PQL saponin extracts inhibited IL-6 production at rates of 80.23% and 79.81%, respectively (Fig. 3C).

A series of studies have reported that among the abundant ginsenosides in Panax, the anti-inflammatory properties of G-Rb1, G-Rb2, CK, G-Rd, G-Re, G-Rg1, G-Rg3, G-Rg5, G-Rh1 and G-Rh2 could be attributed to their capability to suppress the production of proinflammatory cytokines and regulate inflammatory signaling pathways, such as those produced by NF-κB and activator protein-1 (Kim et al., 2017). Previous studies have indicated that NG-R1 could potentially target TNF-α, making it a promising candidate for treating allergic rhinitis (Shao et al., 2023). In addition, notoginsenoside Fd significantly suppresses the production of nitric oxide and the inflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-10, interferon-inducible protein 10, and IL-1β, and it shows moderate anti-inflammatory activity (Li, Chen, et al., 2019; Li, Wang, et al., 2019). Our results indicate that PNL and PQL saponin extracts inhibit the production of inflammatory factors TNF-α and IL-6 in a dose-dependent manner, suggesting a good anti-inflammatory effect in vitro. These positive effects may be due to the presence of abundant ginsenosides, flavonoids, alkaloids, and amino acids.

3.5. Identification and content analysis of metabolites in PNL and PQL saponin extracts

3.5.1. Rapid identification of metabolites in PNL and PQL saponin extracts

To rapidly identify the composition of metabolites in the PNL and PQL saponin extracts, this experiment compared the LC-TOF–MS/MS and MRM scan information of metabolites with multiple databases (Biotree database, KEGG database, HMDB database, etc.). Metabolites were quantitatively assessed through the utilization of Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM) model after the acquisition of secondary data, and the extracted ion chromatogram (EIC) were represented with their specific m/z. The plot showed multiple peaks detected in metabolites using MRM mode. Our results displayed the ion current profile of several compounds, with the x-axis showing the retention time (RT) of the metabolites and the y-axis representing the ion current intensity measured in counts per second (cps) (Fig. S2). A standard total ion current (TIC) plot for a single quality control (QC) sample is depicted in Fig. S3. Our results provided a continuous representation of the combined intensity of all ions present in the mass spectrum at various time intervals (Fig. S3). Consequently, 699 metabolites were identified in the PNL and PQL saponin extracts (Table S3). According to the PCA, the total score of PC1 and PC2 is 53.8%. The two sets of PNL and PQL saponin extracts samples showed significant separation and difference (P < 0.05) (Fig. 4A). In the PNL saponin extract, the relative content of 50 components was twofold that in the PQL saponin extract. In addition, the relative content of 97 components in PQL was higher than that of the PNL saponin extract, with a fold change >2 and a P-value <0.05 for differential metabolites in 27 class categories (Fig. 4B, Table S4). The main components in the PNL saponin extract were Rapanone, N,N-Dimethyl-1,4-phenylenediamine, Rubusoside, 2-Hydroxy-3-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-propanoic acid, 2-Phenylacetamide, Myricitrin, Adenosine, Tricetin, 2-Picolinic acid, Jasmonic acid and Guanine; while the main components in the PQL saponin extract were concentrated on trans-Zeatin, Matairesinol, Thymidine, Indole-3-carboxaldehyde, L-Valine, 5-oxoproline, N-((−)-jasmonoyI)-S-isoleucine, Benzocaine and 5-Hydroxyindole-3-acetic acid according to the screening criteria of VIP > 1 and P < 0.05 (Fig. 4C). Previous research showed that the main bioactive components of Panax genus were triterpene saponin, flavonoids, and amino acids.

Fig. 4.

Metabolite hierarchical cluster analysis of PNL and PQL saponin extracts. (A) Overview of principal component analyses (PCAs) of PNL saponin extract and PQL extract revealed that the total variance explained by PC1 + PC2 was 53.8%, indicating significant differences between the two extracts (P < 0.05). (B) Beeswarm plots comparing the levels of differentially expressed metabolites in PNL saponin extract and PQL extract (fold-changes >2 or < 0.5, VIP > 1, and P-values <0.05). (C) The main components in PNL and PQL saponin extracts which analyzed by random forest analysis method with the conditions of fold-changes >2 or < 0.5, VIP > 1, and P-values <0.05.

3.5.2. Qualitative and quantitative analysis of bioactive metabolites of PNL and PQL saponin extract profiling by HPLC

Triterpenoid saponin. Triterpenoid saponins are indispensable ingredients in the Panax genus. According to the analysis of metabolomic techniques (UPLC–MS), ganoderol B, limonin, notoginsenoside Fc, ginsenoside F₁, ginsenoside Rb2, dammarenediol II, ginsenoside Rd, Cauloside A, and panaxynol are the main triterpenoid components in PNL and PQL saponin extracts (Fig. 5A). To explore the content of the main triterpenoid saponins in PNL and PQL saponin extracts, 14 triterpenoid saponin were quantitatively analyzed by HPLC (Agilent 1260, USA). In the PNL saponin extract, the most abundant ginsenosides are G-Rb₃ at 178.80 ± 0.41 mg/g, NG-Fd at 8.66 ± 0.05 mg/g, NG-Fc at 5.20 ± 0.03 mg/g, NG-Fa at 3.23 ± 0.05 mg/g, and G-Rb₂ (Fig. 5B). Previous studies have confirmed that the main ginsenosides in the P. notoginseng leaves are G-Rb3 (22.08 ± 11.71 mg/g), G-Rb2 (16.90 ± 11.04 mg/g), G-Rb1 (8.83 ± 4.57 mg/g), NG-Fd (1.05 ± 0.11 mg/g), NG-Fa (6.62 ± 2.65 mg/g), and G-F1 (63.30 ± 2.24 mg/g) (Liang et al., 2022). PNL also contains trace amounts of G-Rg5, NG-Fa, NG-Fc, NG-Fd, and NG-Fe. As a result of the optimized extraction processes, most ginsenosides were enriched in the PNL saponin extracts. These results may lead to good antioxidant capacities of PNL saponin extracts. According to the reference, the IC50 of P. notoginseng leaf instant beverage for OH− radicals is 0.58 mg/mL, 0.50 mg/mL for O2− radicals, 0.83 mg/mL for DPPH radicals, and 0.64 mg/mL for ABTS radicals (Liang et al., 2022), consistent with the results of this study. On the other hand, the constituents including G-Rb₃ at 10.18 ± 0.20 mg/g, G-Rg₁ at 5.84 ± 0.27 mg/g, NG-Fd at 3.88 ± 0.0 mg/g, and G-Rb₂ at 1.57 ± 0.05 mg/g were the main ginsenosides in the PQL saponin extract (Fig. 5B, Fig. S4). In the previous study, researchers characterized 173 saponins from the stem leaf of P. notoginseng, and the most important ginsenosides were malonyl-Rb1, Rb1, Ro, and m-Rb2, with malonyl-Rb1 or isomer being the most important bioactive ingredients (Wang et al., 2019). During the processing of P. ginseng, the content of total amino acids and saponins decreases, while the content of total polyphenols and flavonoids increases significantly. This increase is particularly noticeable in terms of ABTS radical, DPPH radical, and hydroxyl radical scavenging capacities, indicating an overall improvement in antioxidant capacity. Li et al. have conducted research on the content of the main pharmacological components in P. quinquefolium roots, specifically, ginsenoside Rb1, Rg1, and Re. They found that the content of these components gradually decreased as the processing temperature increased from 30 °C to 50 °C (Li, Chen, et al., 2019; Li, Wang, et al., 2019).

Fig. 5.

Qualitative and quantitative analysis of the main bioactive constituents of PNL and PQL saponin extracts. (A) Triterpenoid saponin in PNL and PQL saponin extracts identified by LC–MS, (B), The content of 14 ginsenosides in the PNL and PQL saponin extracts detected by HPLC, (C) A total of 25 flavonoids identified in the PNL and PQL saponin extracts, (D) Flavonoids and alkaloids detected in the PNL and PQL saponin extracts, (E) A total of 20 amino acids and their derivatives identified in the PNL and PQL extracts, and (F) 16 amino acids detected in the PNL and PQL extracts. * indicates P < 0.05, ** indicates P < 0.01, and ns indicates that the content in the PNL and PQL extracts shows no significant difference.

Flavonoids and alkaloids. According to the analysis of metabolomic data, 25 components that belong to flavonoids and alkaloids share high relative content in PNL and PQL saponin extracts, of which catechin (C), epicatechin (EC), taxifolin, rutin, quercetin, kaempferol-3-O-rutinoside, theophylline, protocatechuic aldehyde, octyl gallate, isoquercitrin, guercetin 3-O-neohesperidoside, and L-epicatechin show relative high content in the PNL saponin extract (Fig. 5C). To verify the content of flavonoids and alkaloids, 18 ingredients were quantitatively analyzed by HPLC. In PNL, GCG (6.38 ± 0.07 mg/g), ECG (6.14 ± 0.07 mg/g), CA (2.55 ± 0.02 mg/g), theophylline (2.42 ± 0.02 mg/g), and GC (2.37 ± 0.06 mg/g) contents in the PNL extract are higher than that in the PQL extract. In the PQL extract, GCG (16.69 ± 0.34 mg/g), GC (5.97 ± 1.03 mg/g), and rutin (2.63 ± 0.01 mg/g) were the main components (Fig. 5D, Fig. S5). These results indicate that the relative content of flavonoids and alkaloids in the PNL and PQL saponin extracts is different, thus resulting in variations in their bioactivity.

Amino acids and derivatives. In the PNL and PQL saponin extracts, 20 amino acids and their derivatives should be detected by non-targeted metabolomics techniques. They mainly consist of N-heterocyclic non-protein amino acids, including N-acetyl aspartate (N-Acetyl Asp), N-acetyl-L-glutamic acid (N-Acetyl-L-Glu), phenylacetyl-l-glutamine (Phenylacetyl-L-Glu), 2-chloro-DL-phenylalanine (2-Chloro-DL-Phe), L-tyrosine (L-Tyr), L-valine (L-Val), and D-α-aminobutyric acid (D-α-GABA) (Fig. 5E). A previous report suggests that amino acids and derivatives showed a significant role in biotic and abiotic stress responses that regulate numerous aspects of plant growth and development and exist in the form of short peptides or peptides (Cai & Aharoni, 2022). Thus, in PNL and PQL saponin extracts, most amino acids may undergo acetylation and phenylacetyl reactions. L-Phenylalanine and L-tyrosine, which are aromatic amino acids, are used for the synthesis of proteins and may be used as precursors of natural products in plants (Maeda & Dudareva, 2012). They play an important role in the quality formation of Chinese herbal medicine.

Amino acids are the most important nutrients in food or functional foods, for the development of prodrugs, amino acids could enhance the efficacy of drug bioavailability, sensitivity, and target delivery (Vale et al., 2018). To verify the content of amino acid monomers, this experiment further determined 16 amino acids by HPLC in the PNL and PQL saponin extracts. The most abundant main amino acid components in the PNL extract were GABA (426.73 ± 67.28 μg/g), Gly (18.22 ± 7.12 mg/g), Arg (11.10 ± 0.65 mg/g), Glu (9.91 ± 0.83 mg/g), and Asp (9.16 ± 2.07 mg/g). For Radix Notoginseng, Arg (7.80–1.14 mg/g), Asp (5.30–7.43 mg/g), Glu (5.15–6.64 mg/g), and Gly (1.82–2.47 mg/g) are the most abundant amino acids (Chen et al., 2003). On the other hand, GABA (579.05 ± 104.62 μg/g), His (58.22 ± 24.72 mg/g), Met (30.64 ± 4.56 mg/g), Ala (22.46 ± 1.94 mg/g), and Arg (16.24 ± 2.13 mg/g) were the main amino acids in the PQL extract (Fig. 5F, Fig. S6). The products arginyl-fructose and arginyl-fructosyl-glucose enhance the antioxidant activity of P. quinquefolium, an important member of Panax genus, during the thermal process.

Although P. ginseng, P. notoginseng, and P. quinquefolium have a long history of being artificially cultivated and used for medicinal purposes for hundreds of years, historical medical books and prescriptions indicate that their main medicinal parts are the dried rhizomes (Liu, Xu, & Wang, 2020). It is gratifying that the 2020 edition of the Pharmacopoeia of the People's Republic of China has already included P. ginseng leaves as medicinal materials. However, the development and utilization of P. notoginseng leaves (PNL) and P. quinquefolium leaves (PQL) are still lacking. Up to now, researchers have conducted systematic research on the components of PNL and PQL, which mainly focuses on various medicinal and nutritional components. These include triterpenoid saponins, flavonoids, panaxynol, amino acids, and vitamins (Sun et al., 2023). This indicates that the PNL and PQL are highly valuable for development and utilization. However, there is currently no stable, economical, and efficient extraction and preparation process for saponins from PNL and PQL. In addition, there is still insufficient research on the chemical composition and biological activity of saponin extracts from these plant parts. On the basis of these issues, the extraction process of saponins from PNL and PQL, which may serve as high-quality methods for the preparation of saponins, can be optimized.

4. Conclusion

A single factor combined with the response surface method was optimized for extracting saponin from PNL and PQL. Both extracts showed high antioxidant activities, as well as antihypertensive and anti-inflammatory properties. PNL and PQL saponin extracts were enriched with triterpenoid saponins, flavonoids, alkaloids, and amino acids. The contents of 14 ginsenosides, 18 flavonoids and alkaloids, and 16 amino acids were further quantitatively analyzed. This analysis demonstrated the potential applications of these ingredients as sources of function food or natural medicines. This study is a prime example of transforming agricultural by-products into valuable industrial resources of function food or natural medicines.

Fundings

This work was supported by National Key Research and Development Plan of China (2021YFD1601003), Independent Research Fund of Yunnan Characteristic Plant Extraction Laboratory (2022YKZY001), National Natural Science Foundation of China (32160248 & 81860676), and Major Special Science and Technology Project of Yunnan Province (202102AA310048).

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Yan-Hui Guan: Investigation, Data curation. Zheng Lv: Writing – original draft, Software, Methodology. Sheng-Chao Yang: Project administration. Guang-Hui Zhang: Funding acquisition. Yin-He Zhao: Supervision. Ming Zhao: Writing – review & editing, Data curation. Jun-Wen Chen: Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fochx.2024.101642.

Contributor Information

Ming Zhao, Email: zhaoming02292002@aliyun.com.

Jun-Wen Chen, Email: cjw31412@hotmail.com.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Cai J., Aharoni A. Amino acids and their derivatives mediating defense priming and growth tradeoff. Current Opinion in Plant Biology. 2022;69 doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2022.102288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai S.X., Zou J.L., Xu Y.Y., Wang D.Q. Optimization of enzymatic hydrolysis process of Panax notoginseng stem-leaf tea by response surface methodology. Sichuan Food and Fermentation. 2021;57(2):108–114. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1674-506X.2021.02-016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell J.B., Peerbaye Y.A. Saponin. Research in Immunology. 1992;143(5) doi: 10.1016/0923-2494(92)80064-r. 526-530, 577-578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao J., Ma L., Wang S., Deng Y., Wang Y., Li P., Wan J. Comprehensively qualitative and quantitative analysis of ginsenosides in Panax notoginseng leaves by online two-dimensional liquid chromatography coupled to hybrid linear ion trap Orbitrap mass spectrometry with deeply optimized dilution and modulation system. Analytica Chimica Acta. 2019;1079(11):237–251. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2019.06.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S.E., Staba E.J., Taniyasu S., Kasai R., Tanaka O. Further study on dammarane-saponins of leaves and stems of American Ginseng. Panax quinquefolium. Planta Medica. 1981;42(8):406–409. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-971664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z.J., Sun Y.Q., Dong T.X., Zhan H.Q., Cui X.M. Comparison of amino acid contents in Panax notoginseng from different habitats. Journal of Chinese Medicinal Materials. 2003;26(2):86–88. doi: 10.3321/j.issn:1001-4454.2003.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han S.W., Shi S.M., Zou Y.X., Wang Z.C., Wang Y.Q., Shi L., Yan T.C. Chemical constituents from acid hydrolyzates of Panax quinquefolius total saponins and their inhibition activity to alpha-glycosidase and protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B. Chinese Herbal Medicines. 2020;12(2):195–199. doi: 10.1016/j.chmed.2020.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.H., Yi Y.S., Kim M.Y., Cho J.Y. Role of ginsenosides, the main active components of Panax ginseng, in inflammatory responses and diseases. Journal of Ginseng Research. 2017;41(4):435–443. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2016.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M.S., Jeon S.J., Youn S.J., Lee H., Park Y.J., Kim D., O.,... Baik, M. Y. Enhancement of minor ginsenosides contents and antioxidant capacity of American and Canadian ginsengs (Panax quinquefolius) by puffing. Antioxidants. 2019;8(11):527. doi: 10.3390/antiox8110527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F., Wu Z., Sui X. Biotransformation of ginsenoside Rb1 with wild Cordyceps sinensis and Ascomycota sp. and its antihyperlipidemic effects on the diet-induced cholesterol of zebrafish. Journal of Food Biochemistry. 2020;44(6) doi: 10.1111/jfbc.13192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Wang R.F., Zhou Y., Hu H.J., Yang Y.B., Yang L., Wang Z.T. Dammarane-type triterpene oligoglycosides from the leaves and stems of Panax notoginseng and their antiinflammatory activities. Journal of Ginseng Research. 2019;43(3):377–384. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2017.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M., Chen Y., Wang X., Cheng S., Liu F., Huang L. Determination of drying kinetics and quality changes of Panax quinquefolium L. dried in hot-blast air. LWT. 2019;116 doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2019.108563. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Yang N., Shi F., Ye F., Huang J. Isolation and identification of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitory peptides from Tartary buckwheat albumin. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 2023;103(10):5019–5027. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.12573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Z., Liu K., Li R., Ma B., Zheng W., Yang S.…Zhao M. An instant beverage rich in nutrients and secondary metabolites manufactured from stems and leaves of Panax notoginseng. Frontiers in Nutrition. 2022;9 doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.1058639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Z.W., Wang X.M., Liu X.S., Zhang S.Y., Ma Y., Chen J.W.…Zhao M. Extraction technology and antioxidant activity analysis of stem and leaves of Panax notoginseng-Polygonatum kingianum instant powder. Food and Fermentation Industries. 2023;49(02):1–11. doi: 10.13995/j.cnki.11-1802/ts.030025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Lu X., Hu Y., Fan X. Chemical constituents of Panax ginseng and Panax notoginseng explain why they differ in therapeutic efficacy. Pharmacological Research. 2020;161(11) doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2020.105263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L., Xu F.R., Wang Y.Z. Traditional uses, chemical diversity and biological activities of Panax L. (Araliaceae): A review. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2020;263 doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2020.112792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L., Liu F., Zhong Z., Wan J. Comparative study on chemical components and anti-inflammatory effects of Panax notoginseng flower extracted by water and methanol. Journal of Separation Science. 2017;40(24):4730–4739. doi: 10.1002/jssc.201700641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda H., Dudareva N. The shikimate pathway and aromatic amino acid biosynthesis in plants. Annual Review of Plant Biology. 2012;63:73–105. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042811-105439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancuso C., Santangelo R. Panax ginseng and Panax quinquefolius: From pharmacology to toxicology. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 2017;107(Pt A):362–372. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2017.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohanan P., Yang T.J., Song Y.H. Genes and regulatory mechanisms for ginsenoside biosynthesis. Journal Of Plant Biology. 2023;66(1):87–97. doi: 10.1007/s12374-023-09384-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nian B., Chen L., Yi C., Shi X., Jiang B., Jiao W.…Zhao M. A high performance liquid chromatography method for simultaneous detection of 20 bioactive components in tea extracts. Electrophoresis. 2019;40(21):2837–2844. doi: 10.1002/elps.201900154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podolak I., Grabowska K., Sobolewska D., Wróbel-Biedrawa D., Makowska-Wąs J., Galanty A. Saponins as cytotoxic agents: an update (2010–2021). Part II—Triterpene saponins. Phytochemistry Reviews. 2023;22(1):113–167. doi: 10.1007/s11101-022-09830-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shao R., Li W., Chen R., Li K., Cao Y., Chen G., Jiang L. Exploring the molecular mechanism of notoginsenoside R1 in sepsis-induced cardiomyopathy based on network pharmacology and experiments validation. Frontiers in Pharmacology. 2023;14:1101240. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2023.1101240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X., Deng H., Shu T., Xu M., Su L., Li H. Study on chemical constituents of Panax notoginseng leaves. Molecules. 2023;28(5):2194. doi: 10.3390/molecules28052194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szczuka D., Nowak A., Zaklos-Szyda M., Kochan E., Szymanska G., Motyl I., Blasiak J. American ginseng (Panax quinquefolium L.) as a source of bioactive phytochemicals with pro-health properties. Nutrients. 2019;11(5):1041. doi: 10.3390/nu11051041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vale N., Ferreira A., Matos J., Fresco P., Gouveia M.J. Amino acids in the development of prodrugs. Molecules. 2018;23(9):2318. doi: 10.3390/molecules23092318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Zhang C., Zuo T., Li W., Jia L., Wang X.…Yang W. In-depth profiling, characterization, and comparison of the ginsenosides among three different parts (the root, stem leaf, and flower bud) of Panax quinquefolius L. by ultra-high performance liquid chromatography/quadrupole-Orbitrap mass spectrometry. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry. 2019;411(29):7817–7829. doi: 10.1007/s00216-019-02180-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H.P., Fan C.L., Lin Z.Z., Yin Q., Zhao C., Peng P.…Wang Z.B. Screening of potential alpha-glucosidase inhibitors from the roots and rhizomes of Panax ginseng by affinity ultrafiltration screening coupled with UPLC-ESI-Orbitrap-MS method. Molecules. 2023;28(5):2069. doi: 10.3390/molecules28052069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z.H., Wang X.F., Lu T., Li M.R., Jiang P., Zhao J.…Li L.F. Reshuffling of the ancestral core-eudicot genome shaped chromatin topology and epigenetic modification in Panax. Nature Communications. 2022;13(1):1902. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-29561-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Y., Liu C., Im W., Chen S., Zuo K., Yu H.…Jin F. Dynamic changes of multi-notoginseng stem-leaf ginsenosides in reaction with ginsenosidase type-I. Journal of Ginseng Research. 2019;43(2):186–195. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2017.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X.Y., Hu J.N., Liu Z., Zhang R., He Y.F., Hou W.…Li W. Saponins (ginsenosides) from the leaves of Panax quinquefolius ameliorated acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in mice. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2017;65(18):3684–3692. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.7b00610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang M., Tao L., Zhao C.C., Wang Z.L., Yu Z.J., Zhou W.…Sheng J. Antifatigue effect of Panax notoginseng leaves fermented with microorganisms: In-vitro and in-vivo evaluation. Frontiers in Nutrition. 2022;9 doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.824525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Ju Z., Yang Y., Zhang Y., Yang L., Wang Z. Phytochemical analysis of Panax species: A review. Journal of Ginseng Research. 2021;45(1):1–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2019.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng M., Zhang R., Yang Q., Guo L., Zhang X., Yu B.…Lu B. Pharmacological therapy to cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury: Focus on saponins. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2022;155 doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2022.113696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F., Tang S., Zhao L., Yang X., Yao Y., Hou Z., Xue P. Stem-leaves of Panax as a rich and sustainable source of less-polar ginsenosides: Comparison of ginsenosides from Panax ginseng, American ginseng and Panax notoginseng prepared by heating and acid treatment. Journal of Ginseng Research. 2021;45(1):163–175. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2020.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q.Q., Huang Q. Revised method for determining Ganoderma lingzhi terpenoids by UV-vis spectrophotometry based on colorimetric vanillin perchloric acid reaction. Mycosystema. 2018;37(12):1792–1801. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Li C., Hu W., Abdel-Samie M.A., Cui H., Lin L. An overview of tea saponin as a surfactant in food applications. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 2023;1-13 doi: 10.1080/10408398.2023.2258392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao M., Ma Y., Dai L., Zhang D., Li J., Yuan W.…Zhou H. A high-performance liquid chromatographic method for simultaneous determination of 21 free amino acids in tea. Food Analytical Methods. 2013;6(1):69–75. doi: 10.1007/s12161-012-9408-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Y.R., Fan C.L., Chen Y., Quan J.Y., Shi L.Z., Tian C.Y.…Liu J.S. Anti-inflammatory, anti-angiogenetic and antiviral activities of dammarane-type triterpenoid saponins from the roots of Panax notoginseng. Food & Function. 2022;13(6):3590–3602. doi: 10.1039/d1fo04089h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.