Abstract

Background.

Following historically low influenza activity during the 2020–2021 season, the United States saw an increase in influenza circulating during the 2021–2022 season. Most viruses belonged to the influenza A(H3N2) 3C.2a1b 2a.2 subclade.

Methods.

We conducted a test-negative case-control analysis among adults ≥18 years of age at 3 sites within the VISION Network. Encounters included emergency department/urgent care (ED/UC) visits or hospitalizations with ≥1 acute respiratory illness (ARI) discharge diagnosis codes and molecular testing for influenza. Vaccine effectiveness (VE) was calculated by comparing the odds of influenza vaccination ≥14 days before the encounter date between influenza-positive cases (type A) and influenza-negative and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)–negative controls, applying inverse probability-to-be-vaccinated weights, and adjusting for confounders.

Results.

In total, 86 732 ED/UC ARI-associated encounters (7696 [9%] cases) and 16 805 hospitalized ARI-associated encounters (649 [4%] cases) were included. VE against influenza-associated ED/UC encounters was 25% (95% confidence interval (CI), 20%–29%) and 25% (95% CI, 11%–37%) against influenza-associated hospitalizations. VE against ED/UC encounters was lower in adults ≥65 years of age (7%; 95% CI, −5% to 17%) or with immunocompromising conditions (4%; 95% CI, −45% to 36%).

Conclusions.

During an influenza A(H3N2)-predominant influenza season, modest VE was observed. These findings highlight the need for improved vaccines, particularly for A(H3N2) viruses that are historically associated with lower VE.

Keywords: influenza, COVID-19, bias, test-negative design, vaccine effectiveness

Seasonal influenza annually resulted in an estimated 9.3–41 million symptomatic illnesses, 140 000–710 000 hospitalizations, and 12 000–52 000 deaths in the United States during the decade preceding the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic [1]. With implementation of nonpharmaceutical interventions aimed at reducing the spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the virus that causes COVID-19, influenza activity fell to historically low levels during the 2020–2021 season [2, 3]. The 2021–2022 United States influenza season saw prolonged influenza activity with a bimodal peak that inversely correlated with SARS-CoV-2 activity, but a low overall burden of illness [4]. Almost all viruses belonged to an influenza A(H3N2) 3C.2a1b subclade (2a.2) that was genetically similar but antigenically different from the A(H3N2) 3C.2a1b subclade (2a.1) vaccine strain [4, 5].

VISION is a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)-sponsored multistate network of health systems with integrated electronic clinical, laboratory, and vaccination records. Participating health systems capture medically attended encounters of patients with acute respiratory illness (ARI) who receive clinician-ordered testing for respiratory viruses including SARS-CoV-2. The network performs ongoing evaluations of COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness (VE) [6, 7]. VISION health systems with regular clinician-ordered testing for influenza by molecular assay (eg, reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction [RT-PCR]) and integrated influenza vaccination record systems participated in this analysis to assess the effectiveness of 2021–2022 influenza vaccines.

The primary aim of this analysis was to evaluate influenza VE using electronic health record (EHR) data from VISION across a range of settings, including emergency department (ED) and urgent care (UC) encounters and hospitalizations. A secondary objective was to evaluate potential bias in influenza VE estimates associated with the inclusion of SARS-CoV-2–positive controls to inform the selection of controls for future VE analyses.

METHODS

Patients, Settings, and Study Design

This study included EHR data (hospitalization, ED, and UC visits) for adults (≥18 years of age) at 3 VISION sites: Kaiser Permanente Northern California, Intermountain Healthcare in Utah, and HealthPartners in Minnesota and Wisconsin, representing 59 hospitals and 115 ED or UC sites. VISION methods have been described previously [6]. This study protocol was reviewed and approved by the institutional review boards at participating sites or under a reliance agreement with the Westat, Inc institutional review board and by CDC.

We conducted a test-negative case-control analysis of VE against influenza-associated ARI resulting in an ED/UC visit or hospitalization during periods of influenza circulation based on clinical testing data. The VISION network uses a COVID-19–like illness case definition to perform evaluations of COVID-19 VE [6]. To evaluate influenza VE, we adopted a narrowed ARI case definition defined as a medical encounter associated with 1 or more International Classification of Disease, 10th Revision (ICD-10) discharge codes for an acute respiratory clinical diagnosis (eg, pneumonia) or respiratory sign or symptom (eg, cough) (Supplementary Table 1).

Patients received clinician-initiated molecular testing for both influenza and SARS-CoV-2 (to exclude controls with COVID-19 from the primary analysis). Cases had ARI and a positive molecular test for influenza ≤10 days before and up to 72 hours after an ED/UC visit or hospital admission date. Additional information on influenza virus type was extracted when available (influenza A subtype was not available for most cases). Control patients had ARI-associated encounters with negative molecular testing for influenza. Data on hospital readmissions within 30 days after discharge, repeat ED visits within 24 hours, or repeat visits to UC clinics within 24 hours were combined and analyzed as single medical visits within each setting. For each encounter, we extracted patient demographic data and underlying medical conditions based on ICD-10 codes associated with the index encounter from EHRs.

Current season influenza vaccination status, including date of vaccine administration and vaccine product, was determined from EHRs, state immunization information systems, and claims data. A patient was classified as vaccinated if they received ≥1 dose of an influenza vaccine beginning 1 August 2021, and at least 14 days before an index date, defined as the earlier date of the most recent influenza test results or ED/UC visit or admission date. A patient was considered unvaccinated if there was no record of receiving influenza vaccination on or after 1 August 2021, or if the date of administration was after the index date.

ARI-associated encounters were excluded if the index date occurred before sustained influenza activity (which we defined as 2 consecutive weeks of ≥1 case within a site and care setting) or after the last influenza case within a site and care setting through 31 July 2022, if molecular testing for influenza and SARS-CoV-2 was not performed or was indeterminant, if testing was performed >10 days before or ≥72 hours after the encounter or admission, if influenza vaccination was received 1–13 days before the index date, or if the encounter had negative influenza testing but an ICD-10 code for influenza illness or influenza pneumonia (due to uncertainty in case status). Several influenza type B cases were excluded to focus the VE estimate against influenza A(H3N2) viruses that predominated. Encounters among patients who tested negative for influenza but positive for SARS-CoV-2 were excluded as controls from the primary analysis.

Statistical Analysis

For ED/UC and hospital encounters, characteristics by vaccination status and case/control status were described using counts and percentage, along with standardized mean differences (SMDs) across comparison groups. Influenza VE and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated using multivariable logistic regression by comparing the odds of influenza vaccination in cases versus controls, calculated as VE = (1 – adjusted odds ratio [OR]) × 100%). Models were adjusted for patient age, study site, and calendar time. We applied inverse propensity-to-be-vaccinated weights using generalized boosted regression trees based on facility characteristics, demographics, and underlying medical conditions truncated at the 99th percentile. Any covariate with a SMD of 0.20 or larger was included in the weighted multivariable logistic regression model to minimize residual confounding.

Overall influenza A VE was estimated by setting (ED/UC and hospitalization). Separate models were fit to evaluate VE by age group (18–64 and ≥65 years old), site (HealthPartners, Intermountain Healthcare, and Kaiser Permanente Northern California), time since vaccination (vaccinated 14–119 days before index date vs unvaccinated, vaccinated ≥120 days before index date vs unvaccinated), and presence of a likely immunocompromising condition, as previously defined [8]. A sensitivity analysis was performed restricting case patients to those with discharge diagnosis codes for influenza pneumonia and/or influenza disease.

In an analysis assessing the bias associated with use of SARS-CoV-2–positive patient encounters as controls, a secondary analysis was completed including controls with a positive SARS-CoV-2 molecular test and negative influenza molecular test. Analyses were conducted using SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute) or R software, version 4.1.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

RESULTS

Epidemic Curves, ARI Illness by Influenza Case Status, and Vaccine Types

Epidemic curves of PCR-positive influenza cases included in the analysis by site and care setting are shown in Supplementary Figure 1A-1F A bimodal peak in early-season and late-season activity was observed with variation across sites. Influenza activity correlated with local influenza percent positivity data from local laboratory surveillance [9]. In the ED/UC setting, site-specific season start dates for the analysis ranged from 6 November to 27 November 2021, and season end dates ranged from 29 June to 10 July 2022. For hospitalizations, site-specific start dates ranged from 27 November to 4 December 2021, and end dates from 12 June to 2 July 2022. Among cases, the most common codes included those for influenza disease (63%), upper respiratory tract infection (31%), and acute respiratory signs or symptoms (28%) (Supplementary Table 2). Among controls, the most common codes included those for acute respiratory signs or symptoms (35%), upper respiratory tract infection (32%), and bacterial pneumonia (18%).

Combining ED/UC and hospital encounters, 28 860 (64%) vaccinated patients had information on vaccine type (Supplementary Table 3). Of these 28 860, 10 559 (37%) received standard-dose quadrivalent inactivated influenza vaccine (IIV4), 5879 (20%) received high-dose inactivated vaccine, and 11721 (41%) received an adjuvanted vaccine. Among 9814 vaccinated adults 18–64 years of age with vaccine type known, most (9205, 94%) received standard-dose IIV4. Among adults ≥65 years of age, of 19 046 with vaccine type known, most (17 692, 93%) received a product other than standard-dose IIV4, most commonly an adjuvanted (11 563, 61%) or high-dose inactivated vaccine (5849, 31%).

ED/UC Encounters

Of 160 434 ARI-associated ED/UC visits among adults aged ≥18 years during periods of influenza circulation, 102 593 (64%) had an influenza molecular test (Supplementary Figure 2). After applying additional exclusion criteria, 86 732 ARI-associated encounters were included in the primary ED/UC analysis. Influenza testing was positive in 7696 (9%) encounters and negative in 79 036 (91%) (Table 1). Overall, 35 650 (41%) patients (31% of cases vs 42% of controls) were vaccinated against influenza, ranging from 36% to 52% across sites (Table 1). Coverage was higher in adults ≥65 years of age (64% vaccinated, including 63% of cases and 64% of controls) compared to adults 18–64 years of age (31% vaccinated, including 23% of cases and 32% of controls), SMD = 0.65. Overall, 32% of encounters occurred in adults ≥65 years of age, 59% in women, and 36% in patients with 1 or more underlying medical conditions documented from the encounter.

Table 1.

Characteristics of ED and UC Encounters Among Adults With Influenza–Like Illness by Influenza Vaccination Status and Influenza Test Result—November 2021–July 2022

| Characteristic | Total, No. (Col. %) |

Influenza Vaccination Status | SMD | Influenza Test Result | SMD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unvaccinated, No. (Row %) |

Vaccinated, No. (Row %) |

Negative, No. (Row %) |

Positive, No. (Row %) |

||||

| All ED/UC events | 86 732 (100) | 51 082 (59) | 35 650 (41) | 79 036 (91) | 7696 (9) | ||

| Influenza vaccination status | |||||||

| Overall | |||||||

| Unvaccinated | 51 082 (59) | 51 082 (100) | 0 (0) | 45 750 (90) | 5332 (10) | ||

| Vaccinated | 35 650 (41) | 0 (0) | 35 650 (100) | 33 286 (93) | 2364 (7) | ||

| Age 18–64 y | |||||||

| Unvaccinated | 41 027 (69) | 41 027 (100) | 0 (0) | 36 238 (88) | 4789 (12) | ||

| Vaccinated | 18 123 (31) | 0 (0) | 18 123 (100) | 16 689 (92) | 1434 (8) | ||

| Age 65+ y | |||||||

| Unvaccinated | 10 055 (36) | 10 055 (100) | 0 (0) | 9512 (95) | 543 (5) | ||

| Vaccinated | 17 527 (64) | 0 (0) | 17 527 (100) | 16 597 (95) | 930 (5) | ||

| Immunocompromised | |||||||

| Unvaccinated | 1523 (50) | 1523 (100) | 0 (0) | 1465 (96) | 58 (4) | ||

| Vaccinated | 1553 (50) | 0 (0) | 1553 (100) | 1499 (96) | 54 (4) | ||

| Nonimmunocompromised | |||||||

| Unvaccinated | 49 559 (59) | 49 559 (100) | 0 (0) | 44 285 (89) | 5274 (11) | ||

| Vaccinated | 34 097 (41) | 0 (0) | 34 097 (100) | 31 787 (93) | 2310 (7) | ||

| Month of encounter | 0.22 | 0.71 | |||||

| November 2021 | 10 365 (12) | 7297 (70) | 3068 (30) | 10 290 (99) | 75 (1) | ||

| December 2021 | 18 737 (22) | 11 790 (63) | 6947 (37) | 17 420 (93) | 1317 (7) | ||

| January 2022 | 11 148 (13) | 6414 (58) | 4734 (42) | 10 577 (95) | 571 (5) | ||

| February 2022 | 5742 (7) | 3146 (55) | 2596 (45) | 5402 (94) | 340 (6) | ||

| March 2022 | 10 209 (12) | 5864 (57) | 4345 (43) | 8306 (81) | 1903 (19) | ||

| April 2022 | 9472 (11) | 5163 (55) | 4309 (45) | 8065 (85) | 1407 (15) | ||

| May 2022 | 10 366 (12) | 5629 (54) | 4737 (46) | 9128 (88) | 1238 (12) | ||

| June 2022 | 9599 (11) | 5233 (55) | 4366 (45) | 8806 (92) | 793 (8) | ||

| July 2022 | 1094 (1) | 546 (50) | 548 (50) | 1042 (95) | 52 (5) | ||

| Sites | 0.32 | 0.05 | |||||

| HealthPartners | 8631 (10) | 4205 (49) | 4426 (51) | 7784 (90) | 847 (10) | ||

| Intermountain Healthcare | 57 920 (67) | 37 245 (64) | 20 675 (36) | 52 761 (91) | 5159 (9) | ||

| Kaiser Permanente Northern California | 20 181 (23) | 9632 (48) | 10 549 (52) | 18 491 (92) | 1690 (8) | ||

| Age groups | 0.65 | −0.32 | |||||

| 18–64 y | 59 150 (68) | 41 027 (69) | 18 123 (31) | 52 927 (89) | 6223 (11) | ||

| ≥65 y | 27 582 (32) | 10 055 (36) | 17 527 (64) | 26 109 (95) | 1473 (5) | ||

| Biological sex | 0.07 | 0.03 | |||||

| Male | 35 927 (41) | 21 925 (61) | 14 002 (39) | 32 853 (91) | 3074 (9) | ||

| Female | 50 775 (59) | 29 127 (57) | 21 648 (43) | 46 160 (91) | 4615 (9) | ||

| Other | 3 (0) | 3 (100) | 0 (0) | 2 (67) | 1 (33) | ||

| Unknown | 27 (0) | 27 (100) | 0 (0) | 21 (78) | 6 (22) | ||

| Race, regardless of ethnicity | 0.12 | 0.20 | |||||

| White | 67 927 (78) | 39 449 (58) | 28 478 (42) | 62 460 (92) | 5467 (8) | ||

| Black | 4768 (5) | 3252 (68) | 1516 (32) | 4265 (89) | 503 (11) | ||

| Othera | 7325 (8) | 4113 (56) | 3212 (44) | 6555 (89) | 770 (11) | ||

| Unknown | 6712 (8) | 4268 (64) | 2444 (36) | 5756 (86) | 956 (14) | ||

| Ethnicity, regardless of race | 0.13 | 0.23 | |||||

| Hispanic | 12 554 (14) | 8220 (65) | 4334 (35) | 10 844 (86) | 1710 (14) | ||

| Non-Hispanic | 65 393 (75) | 37 385 (57) | 28 008 (43) | 60 186 (92) | 5207 (8) | ||

| Unknown | 8785 (10) | 5477 (62) | 3308 (38) | 8006 (91) | 779 (9) | ||

| Underlying chronic condition | 0.20 | −0.39 | |||||

| Chronic condition | 30 829 (36) | 16 131 (52) | 14 698 (48) | 29 311 (95) | 1518 (5) | ||

| None | 55 903 (64) | 34 951 (63) | 20 952 (37) | 49 725 (89) | 6178 (11) | ||

| Chronic respiratory condition | 0.15 | −0.31 | |||||

| Yes | 20 682 (24) | 10 794 (52) | 9888 (48) | 19 696 (95) | 986 (5) | ||

| No | 66 050 (76) | 40 288 (61) | 25 762 (39) | 59 340 (90) | 6710 (10) | ||

| Chronic nonrespiratory condition | 0.17 | −0.34 | |||||

| Yes | 21 144 (24) | 10 871 (51) | 10 273 (49) | 20 180 (95) | 964 (5) | ||

| No | 65 588 (76) | 40 211 (61) | 25 377 (39) | 58 856 (90) | 6732 (10) | ||

| Immunosuppressive condition at discharge | 0.07 | −0.14 | |||||

| Yes | 3076 (4) | 1523 (50) | 1553 (50) | 2964 (96) | 112 (4) | ||

| No | 83 656 (96) | 49 559 (59) | 34 097 (41) | 76 072 (91) | 7584 (9) | ||

| Death | 0.01 | −0.02 | |||||

| Yes | 32 (0) | 16 (50) | 16 (50) | 31 (97) | 1 (3) | ||

| No | 86 696 (100) | 51 063 (59) | 35 633 (41) | 79 002 (91) | 7694 (9) | ||

| Unknown | 4 (0) | 3 (75) | 1 (25) | 3 (75) | 1 (25) | ||

Abbreviations: Col., column; ED, emergency department; SMD, standardized mean difference; UC, urgent care.

Other race defined as any one of the following responses: Asian, Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, American Indian or Alaska Native, other, multiple races.

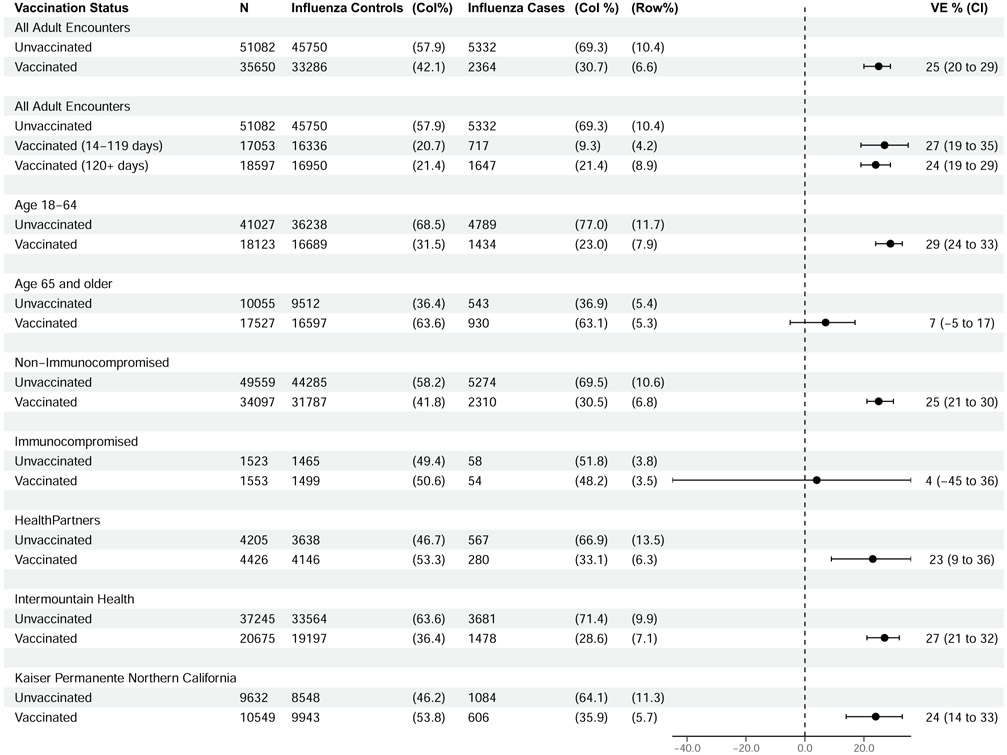

Overall VE against influenza-associated ED/UC encounters was 25% (95% CI, 20%–29%), including 29% (95% CI, 24%–33%) among adults aged 18–64 years and 7% (95% CI, −5% to 17%) among adults ≥65 years (Figure 1). Among adults ≥65 years of age, estimates were similar among those 65–79 years (5%; 95% CI, −9% to 17%) and those ≥80 years of age (15%; 95% CI, −4% to 30%). VE was similar at 14–119 days (27%; 95% CI, 19–35) and ≥120 days postvaccination (24%; 95% CI, 19–29) and across sites, with point estimates ranging from 23% to 27%. VE was 4% (95% CI, −45% to 36%) among patients with likely immunocompromising conditions, compared to 25% (95% CI, 21%–30%) among patients without immunocompromising conditions. In a sensitivity analysis restricting cases to those with codes for influenza pneumonia or influenza disease, results were highly similar (Supplementary Figure 3).

Figure 1.

Influenza vaccine effectiveness against emergency department- or urgent care-associated influenza illness. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; Col, column; VE, vaccine effectiveness.

Hospitalizations

Of 34 799 ARI-associated hospitalizations among adults aged ≥18 years during periods of influenza circulation, 21 805 (63%) had an influenza molecular test (Supplementary Figure 4). After applying additional exclusion criteria, 16 805 ARI-associated hospitalizations among patients aged ≥18 years were included in the primary analysis. Influenza testing was positive in 649 (4%) hospital encounters and negative in 16 156 (96%) (Table 2). Vaccination was received by 9486 (56%) patients (46% of cases vs 57% of controls), ranging from 46% to 62% across sites (Table 2), with higher coverage in adults ≥65 years of age (64% vaccinated, including 56% of cases and 65% of controls) compared to adults 18–64 years of age (40% vaccinated, including 30% of cases and 41% of controls). Among hospital encounters, 68% occurred in patients who were ≥65 years of age, 52% in women, and 98% in patients with 1 or more underlying medical conditions.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Hospitalizations With Influenza-Like Illness Among Adults by Influenza Vaccination Status and Influenza Test Result—November 2021–July 2022

| Characteristic | Total, No. (Col. %) |

Influenza Vaccination Status | SMD | Influenza Test Result | SMD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unvaccinated, No. (Row %) |

Vaccinated, No. (Row %) |

Negative, No. (Row %) |

Positive, No. (Row %) |

||||

| All hospitalizations | 16 805 (100) | 7319 (44) | 9486 (56) | 16 156 (96) | 649 (4) | ||

| Influenza vaccination status | |||||||

| Overall | |||||||

| Unvaccinated | 7319 (44) | 7319 (100) | 0 (0) | 6969 (95) | 350 (5) | ||

| Vaccinated | 9486 (56) | 0 (0) | 9486 (100) | 9187 (97) | 299 (3) | ||

| Age 18–64 y | |||||||

| Unvaccinated | 3246 (60) | 3246 (100) | 0 (0) | 3079 (95) | 167 (5) | ||

| Vaccinated | 2198 (40) | 0 (0) | 2198 (100) | 2128 (97) | 70 (3) | ||

| Age 65+ y | |||||||

| Unvaccinated | 4073 (36) | 4073 (100) | 0 (0) | 3890 (95) | 183 (5) | ||

| Vaccinated | 7288 (64) | 0 (0) | 7288 (100) | 7059 (97) | 229 (3) | ||

| Immunocompromised | |||||||

| Unvaccinated | 1631 (39) | 1631 (100) | 0 (0) | 1591 (97) | 40 (3) | ||

| Vaccinated | 2553 (61) | 0 (0) | 2553 (100) | 2500 (98) | 54 (2) | ||

| Nonimmunocompromised | |||||||

| Unvaccinated | 5688 (45) | 5688 (100) | 0 (0) | 5378 (94) | 310 (6) | ||

| Vaccinated | 6933 (55) | 0 (0) | 6933 (100) | 6687 (96) | 246 (4) | ||

| Month of encounter | 0.11 | 0.45 | |||||

| November 2021 | 239 (1) | 118 (49) | 121 (51) | 238 (100) | 1 (0) | ||

| December 2021 | 2989 (18) | 1409 (47) | 1580 (53) | 2912 (97) | 77 (3) | ||

| January 2022 | 2536 (15) | 1142 (45) | 1394 (55) | 2481 (98) | 55 (2) | ||

| February 2022 | 1872 (11) | 825 (44) | 1047 (56) | 1835 (98) | 37 (2) | ||

| March 2022 | 2308 (14) | 1031 (45) | 1277 (55) | 2175 (94) | 133 (6) | ||

| April 2022 | 2423 (14) | 993 (41) | 1430 (59) | 2311 (95) | 112 (5) | ||

| May 2022 | 2584 (15) | 1073 (42) | 1511 (58) | 2456 (95) | 128 (5) | ||

| June 2022 | 1824 (11) | 719 (39) | 1105 (61) | 1721 (94) | 103 (6) | ||

| July 2022 | 30 (0) | 9 (30) | 21 (70) | 27 (90) | 3 (10) | ||

| Sites | −0.32 | 0.43 | |||||

| HealthPartners | 2574 (15) | 967 (38) | 1607 (62) | 2499 (97) | 75 (3) | ||

| Intermountain Healthcare | 5566 (33) | 3021 (54) | 2545 (46) | 5226 (94) | 340 (6) | ||

| Kaiser Permanente Northern California | 8665 (52) | 3331 (38) | 5334 (62) | 8431 (97) | 234 (3) | ||

| Age groups | 0.46 | −0.09 | |||||

| 18–64 y | 5444 (32) | 3246 (60) | 2198 (40) | 5207 (96) | 237 (4) | ||

| ≥65 y | 11 361 (68) | 4073 (36) | 7288 (64) | 10 949 (96) | 412 (4) | ||

| Biological sex | 0.07 | 0.09 | |||||

| Male | 8115 (48) | 3671 (45) | 4444 (55) | 7830 (96) | 285 (4) | ||

| Female | 8684 (52) | 3642 (42) | 5042 (58) | 8320 (96) | 364 (4) | ||

| Unknown | 6 (0) | 6 (100) | 0 (0) | 6 (100) | 0 (0) | ||

| Race, regardless of ethnicitya | 0.13 | 0.11 | |||||

| White | 12 175 (72) | 5182 (43) | 6993 (57) | 11 686 (96) | 489 (4) | ||

| Black | 1211 (7) | 656 (54) | 555 (46) | 1170 (97) | 41 (3) | ||

| Other | 2086 (12) | 860 (41) | 1226 (59) | 2025 (97) | 61 (3) | ||

| Unknown | 1333 (8) | 621 (47) | 712 (53) | 1275 (96) | 58 (4) | ||

| Ethnicity, regardless of race | 0.17 | 0.14 | |||||

| Hispanic | 1979 (12) | 914 (46) | 1065 (54) | 1879 (95) | 100 (5) | ||

| Non-Hispanic | 12 138 (72) | 4997 (41) | 7141 (59) | 11 670 (96) | 468 (4) | ||

| Unknown | 2688 (16) | 1408 (52) | 1280 (48) | 2607 (97) | 81 (3) | ||

| Underlying chronic condition | 0.14 | −0.20 | |||||

| Chronic condition | 16 532 (98) | 7124 (43) | 9408 (57) | 15 915 (96) | 617 (4) | ||

| None | 273 (2) | 195 (71) | 78 (29) | 241 (88) | 32 (12) | ||

| Chronic respiratory condition | 0.10 | −0.30 | |||||

| Yes | 13 571 (81) | 5754 (42) | 7817 (58) | 13 127 (97) | 444 (3) | ||

| No | 3234 (19) | 1565 (48) | 1669 (52) | 3029 (94) | 205 (6) | ||

| Chronic nonrespiratory condition | 0.20 | −0.23 | |||||

| Yes | 16 147 (96) | 6867 (43) | 9280 (57) | 15 558 (96) | 589 (4) | ||

| No | 658 (4) | 452 (69) | 206 (31) | 598 (91) | 60 (9) | ||

| Immunosuppressive condition | 0.11 | −0.28 | |||||

| Yes | 4184 (25) | 1631 (39) | 2553 (61) | 4091 (98) | 93 (2) | ||

| No | 12 621 (75) | 5688 (45) | 6933 (55) | 12 065 (96) | 556 (4) | ||

| ICU during visit | −0.03 | −0.24 | |||||

| Yes | 2766 (16) | 1253 (45) | 1513 (55) | 2708 (98) | 58 (2) | ||

| No | 14 039 (84) | 6066 (43) | 7973 (57) | 13 448 (96) | 591 (4) | ||

| Death | −0.01 | −0.15 | |||||

| Yes | 970 (6) | 429 (44) | 541 (56) | 952 (98) | 18 (2) | ||

| No | 15 835 (94) | 6890 (44) | 8945 (56) | 15 204 (96) | 631 (4) | ||

Abbreviations: Col., column; ICU, intensive care unit; SMD, standardized mean difference.

Other race defined as any one of the following responses: Asian, Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, American Indian or Alaska Native, other, multiple races.

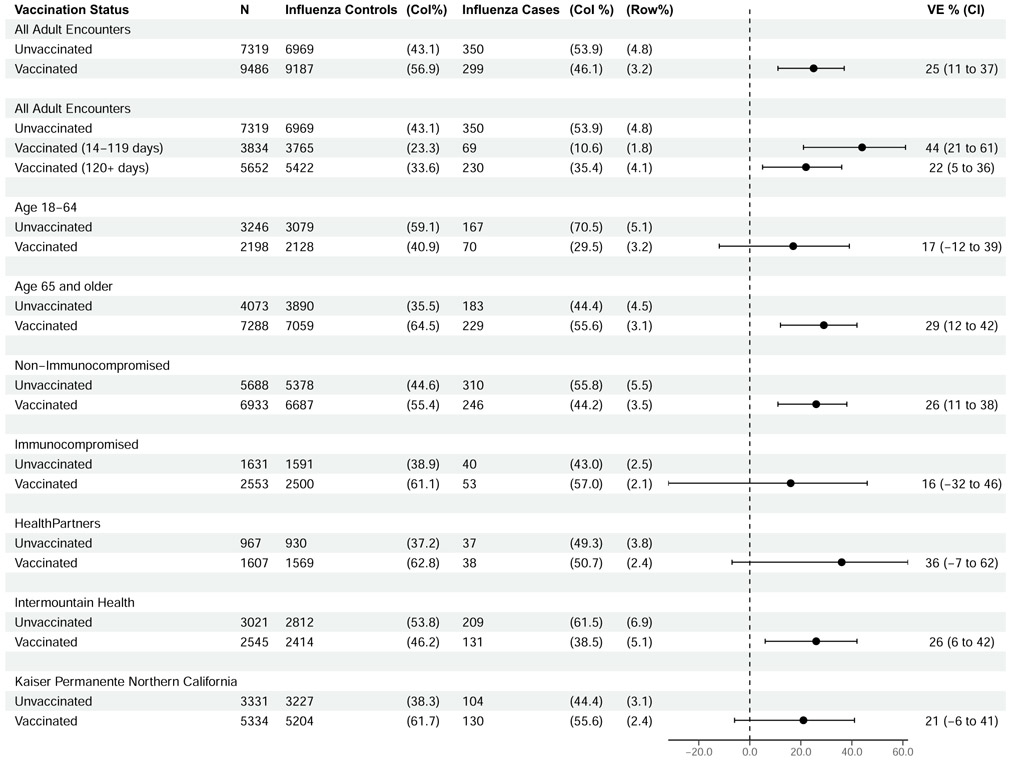

VE against influenza-associated hospitalization was 25% (95% CI, 11%–37%), including 17% (95% CI, −12% to 39%) among adults aged 18–64 years and 29% (95% CI, 12%–42%) among adults aged ≥65 years with overlapping confidence intervals (Figure 2). Among adults ≥65 years of age, estimates were similar among those 65–79 years (24%; 95% CI, −2% to 44%) and those ≥80 years of age (36%; 95% CI, 14%–53%). VE was higher at 14–119 days (44%; 95% CI, 21%–61%) compared to ≥120 days postvaccination (VE = 22%; 95% CI, 5%–36%) but with overlapping confidence intervals. VE was 16% (95% CI, −32% to 46%) among patients with likely immunocompromising conditions, compared to 26% (95% CI, 11%–38%) among patients without immunocompromising conditions. Restricting cases to those with codes for influenza pneumonia or influenza disease, similar VE results were observed (Supplementary Figure 5).

Figure 2.

Influenza vaccine effectiveness against hospitalized influenza illness. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; Col, column; VE, vaccine effectiveness.

Bias Analysis

In a secondary bias analysis, for ED/UC encounters 12 936 of 91 972 (14%) influenza-negative controls were SARS-CoV-2 positive. For hospitalizations, 4709 of 20 865 (23%) controls were SARS-CoV-2 positive. Inclusion of SARS-CoV-2–positive controls (Supplementary Figure 2 and Supplementary Figure 4) resulted in a reduction in VE estimates across settings, from 25% to 22% for influenza-associated ED/UC events and from 25% to 17% for influenza-associated hospitalizations (Supplementary Figure 6 and Supplementary Figure 7).

DISCUSSION

During an influenza season with predominant A(H3N2) virus circulation, we found that seasonal influenza vaccination provided modest protection of 25% against illness in both ED/UC and hospital inpatient settings. VE estimates were similar to influenza A(H3N2) estimates from prior seasons [10-12]. Most influenza vaccines distributed in the United States are egg grown and are prone to altered hemagglutinin (HA) antigenicity, diverted antibody response caused by mutations acquired during egg adaptation that result in loss of glycosylation sites on the HA head, or induction of antibodies against an egg-associated glycan. Heterogeneity in VE was notable across population subgroups, including by age group and presence of likely immunocompromising conditions within ED/UC settings. Findings from this analysis, including a low overall VE against A(H3N2) and no VE observed in certain groups at increased risk for severe influenza such as those with immunocompromising conditions, highlight the need for improved influenza vaccines. This could include development of universal vaccines or vaccines that can be quickly developed and administered to target actively circulating viruses and are not prone to altered HA antigenicity or egg-adaptive changes like commonly used egg-based vaccines (eg, mRNA vaccines) [13, 14]. Early clinical testing coupled with timely initiation of influenza antiviral therapy also remain important for reducing the risk of severe influenza.

This study adapted electronic data sources and methods used to assess COVID-19 VE to evaluate influenza VE during the 2021–2022 season across geographically diverse sites. Among patients who met ARI criteria by ICD-10 discharge codes while influenza was locally circulating, clinical testing was observed in almost two-thirds of encounters, suggesting the ARI definition generally captured patients for whom testing was indicated. Despite differences in populations, sources of data, and potentially in local testing practices, VE was similar and consistent across sites, particularly in ED/UC settings, supporting the validity of observed estimates. Furthermore, in a sensitivity analysis restricting cases to those with influenza pneumonia or influenza disease discharge codes, VE was highly similar to results from the primary analysis.

Evidence to strongly support within-season waning was not observed, in contrast to a number of previous studies [15-17]. Ferdinands et al found an average 7% decline in A(H3N2) VE per month across multiple influenza seasons in an adult hospital-based VE network [15]. In an integrated health system in California, across 7 seasons (2010–2011 to 2016–2017) Ray et al found that persons vaccinated 42 to 69 days prior to receiving influenza molecular testing had 1.32 times the odds of testing positive for influenza compared to those vaccinated 14 to 41 days earlier, with an odds ratio that increased linearly with increasing time since vaccination [16]. Reasons for a lack of strong evidence to support within-season waning during the 2021–2022 season could include similarities in A(H3N2) viruses circulating throughout the season, a low incidence of infection during the first peak of activity without a depletion of susceptible hosts, or unmeasured or residual confounding in VE models (eg, timing of influenza vaccination may have differed based on factors associated with risk of influenza illness and associated complications).

Differences in VE by age group (18–64 years vs ≥65 years) were observed across ED/UC and hospital settings. For ED/UC encounters, VE was modest among younger adults, but a nonsignificant VE was observed among older adults. The ambulatory United States Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness (Flu VE) Network found similar VE among adults 18–49 years of age in outpatient settings during the 2021–2022 influenza season as observed in our study in ED/UC settings (32% for 18–49 year olds vs 29% for 18–64 year olds in our study) [18]. The Flu VE Network study also found a nonsignificant VE in adults ≥50 years of age. Findings in our study of nonsignificant VE against influenza A(H3N2) viruses in the ED/UC setting despite most older adults receiving high-dose or adjuvanted vaccines may include birth cohort effects from early life exposure to non-A(H3N2) viruses [19], immunosenescence associated with aging [20], or effects of repeat vaccination [21-23]. These findings were not replicated in the hospital setting, where VE point estimates were similar across age group and with overlapping confidence intervals. Differences in VE by settings might be due to differences in patient characteristics, residual confounding, differences in testing practices, or a limited sample size of hospital encounters with low precision in hospital estimates.

As observed in a prior simulation study [24], our VE estimates were lower when SARS-CoV-2–positive controls were included in influenza VE analyses, with 3% and 8% lower estimates for ED/UC encounters and hospitalizations, respectively, compared to primary estimates that excluded SARS-CoV-2–positive controls. These findings are hypothesized to be related to the correlation between seasonal influenza vaccination and COVID-19 vaccination behaviors. Namely, individuals who do not receive COVID-19 vaccination are less likely to be vaccinated against influenza [25]. These individuals also have lower protection against COVID-19 than those who received COVID-19 vaccination and may therefore represent a sizable proportion of ED/UC and hospital ARI encounters when SARS-CoV-2 is circulating. Future studies that evaluate influenza VE should account for SARS-CoV-2, either by excluding SARS-CoV-2–positive controls or controlling for prior COVID-19 vaccination.

This analysis was subject to several limitations. First, although we included 3 health systems with integrated health records and robust vaccination linkage [26], influenza vaccination may have been underascertained at some sites. Vaccination coverage, particularly among older adults hospitalized with ARI, was lower than observed during previous seasons in some VE networks [27-29]. However, the COVID-19 pandemic, increased vaccine hesitancy from COVID-19 vaccines influencing influenza vaccine uptake, as well as lower influenza activity in the United States since 2020 may have influenced vaccination behaviors [25]. Underascertainment is unlikely to have resulted in marked bias unless this occurred differentially among cases and controls. Second, low levels of influenza activity limited statistical power, particularly for hospital estimates. Third, unmeasured or residual confounding is possible. Fourth, patients across 4 included states may not be representative of the entire United States population and influenza testing practices may have been different within included health systems. Furthermore, the complement of vaccine products used within participating health care settings may not be representative of vaccines used in other health systems and could impact VE. Some evidence of differences in immunogenicity and relative VE have been observed between influenza vaccine types, such as recombinant and cell-culture based vaccines not commonly used in this study [30-32].

CONCLUSIONS

During the 2021–2022 United States influenza season, we observed modest VE against influenza A(H3N2) in ED/UC and hospital settings and heterogeneity across population subgroups. There is a need to improve influenza vaccines against influenza A(H3N2) viruses, which are associated with a high burden of severe disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We acknowledge the contributions of the VISION Network, especially the following individuals: HealthPartners Institute (Inih Essien, OD, Linda Fletcher, MPH, Sunita Thapa, MPH, and Sheryl Kane, BS); Westat (Akintunde Akinseye, MSPH, MPH, Elizabeth Bassett, BA, Jewel Bernard-Hunte, MPH, Bria Berry, MPH, Rebecca Birch, MPH, Kristen Butterfield, MPH, Kevin Cheng, BS, Sumanthi Croos, BA, Jonathan Davis, PhD, Maria Demarco, PhD, Rebecca Fink, MPH, Carly Hallowell, MPH, Nina Hamburg, MBA, Alex Hughes, PhD, Jean Keller, MS, Salome Kiduko, MPH, Magdalene Kish, BS, Victoria Lazariu, PhD, Yong Lee, BSEE, Matthew Levy, PhD, Yessie Martinez, MPH, Vanessa Masick, MS, Thomas Mienk, MPA, Patrick Mitchell, ScD, Jean Opsomer, PhD, Weijia Ren, PhD, John Riddles, MS, Sarah Reese, PhD, Elizabeth Rowley, DrPH, Anna Rukhlya, MA, Kristin Schrader, MA, Patricia Shifflett, MS, Talia Spark, PhD, Brenda Sun, MS, Hansong Wang, PhD, Donald Warden, MPH, Steph Wraith, PhD, and Yan Zhuang, PhD); Regenstrief Institute (Ashley Wiensch, MPH, and Amy Hancock, MPA); University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus (Health Data Compass—David Mayer, BS, Bryant Doyle, Briana Kille, PhD, and Catia Chavez, MPH); Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research (Padma Dandamudi, MPH); and Vanderbilt University Medical Center (Allison B. McCoy, PhD, Donald Sengstack, MS, Coda L. Davison, MPA).

Financial support.

This study was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (contract numbers 75D30120C07986 to Westat and 75D30120C07765 to Kaiser Foundation Hospitals).

Footnotes

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at The Journal of Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copy-edited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Disclaimer. The findings and conclusions of this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Potential conflicts of interest. S. R. received grants from GlaxoSmithKline. A. L. N. received grants from Pfizer and Vir Biotechnology. C. M. received grants from AstraZeneca. N. P. K. received grants from Pfizer, Merck, GlaxoSmithKline, and Sanofi Pasteur. All other authors report no potential conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Disease burden of flu. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/burden/index.html. Accessed 3 October 2022.

- 2.Olsen SJ, Winn AK, Budd AP, et al. Changes in influenza and other respiratory virus activity during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, 2020–2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021; 70:1013–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olsen SJ, Azziz-Baumgartner E, Budd AP, et al. Decreased influenza activity during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, Australia, Chile, and South Africa, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020; 69:1305–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Merced-Morales A, Daly P, Abd Elal AI, et al. Influenza activity and composition of the 2022–23 influenza vaccine—United States, 2021–22 season. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2022; 71:913–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chung JR, Kim SS, Kondor RJ, et al. Interim estimates of 2021–22 seasonal influenza vaccine effectiveness—United States, February 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2022; 71:365–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thompson MG, Stenehjem E, Grannis S, et al. Effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines in ambulatory and inpatient care settings. N Engl J Med 2021; 385:1355–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thompson MG, Natarajan K, Irving SA, et al. Effectiveness of a third dose of mRNA vaccines against COVID-19-associated emergency department and urgent care encounters and hospitalizations among adults during periods of Delta and Omicron variant predominance—VISION network, 10 States, August 2021–January 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2022; 71:139–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Embi PJ, Levy ME, Naleway AL, et al. Effectiveness of 2-dose vaccination with mRNA COVID-19 vaccines against COVID-19-associated hospitalizations among immunocompromised adults—nine states, January September 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021; 70:1553–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Weekly U.S. influenza surveillance report. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/weekly/index.htm. Accessed 3 October 2022.

- 10.Belongia EA, McLean HQ. Influenza vaccine effectiveness: defining the H3N2 problem. Clin Infect Dis 2019; 69: 1817–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Belongia EA, Simpson MD, King JP, et al. Variable influenza vaccine effectiveness by subtype: a systematic review and meta-analysis of test-negative design studies. Lancet Infect Dis 2016; 16:942–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Russell K, Chung JR, Monto AS, et al. Influenza vaccine effectiveness in older adults compared with younger adults over five seasons. Vaccine 2018; 36:1272–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zost SJ, Parkhouse K, Gumina ME, et al. Contemporary H3N2 influenza viruses have a glycosylation site that alters binding of antibodies elicited by egg-adapted vaccine strains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2017; 114:12578–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu NC, Zost SJ, Thompson AJ, et al. A structural explanation for the low effectiveness of the seasonal influenza H3N2 vaccine. PLoS Pathog 2017; 13:e1006682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferdinands JM, Fry AM, Reynolds S, et al. Intraseason waning of influenza vaccine protection: evidence from the US influenza vaccine effectiveness network 2011–12 through 2014–15. Clin Infect Dis 2017; 64:544–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ray GT, Lewis N, Klein NP, et al. Intraseason waning of influenza vaccine effectiveness. Clin Infect Dis 2019; 68: 1623–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Young B, Sadarangani S, Jiang L, Wilder-Smith A, Chen MI. Duration of influenza vaccine effectiveness: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression of test-negative design case-control studies. J Infect Dis 2018; 217:731–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Price AM, Flannery B, Talbot HK, et al. Influenza vaccine effectiveness against influenza A(H3N2)-related illness in the United States during the 2021–2022 influenza season. Clin Infect Dis 2022; ciac941. 10.1093/cid/ciac941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Budd AP, Beacham L, Smith CB, et al. Birth cohort effects in influenza surveillance data: evidence that first influenza infection affects later influenza-associated illness. J Infect Dis 2019; 220:820–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aw D, Silva AB, Palmer DB. Immunosenescence: emerging challenges for an ageing population. Immunology 2007; 120:435–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Skowronski DM, Chambers C. Pooling and the potential dilution of repeat influenza vaccination effects. Clin Infect Dis 2017; 65:353–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Skowronski DM, Chambers C, De Serres G, et al. Serial vaccination and the antigenic distance hypothesis: effects on influenza vaccine effectiveness during A(H3N2) epidemics in Canada, 2010–2011 to 2014–2015. J Infect Dis 2017; 215:1059–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones-Gray E, Robinson EJ, Kucharski AJ, Fox A, Sullivan SG. Does repeated influenza vaccination attenuate effectiveness? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Respir Med 2022; 11:27–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Doll MK, Pettigrew SM, Ma J, Verma A. Effects of confounding bias in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and influenza vaccine effectiveness test-negative designs due to correlated influenza and COVID-19 vaccination behaviors. Clin Infect Dis 2022; 75:e564–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leuchter RK, Jackson NJ, Mafi JN, Sarkisian CA. Association between COVID-19 vaccination and influenza vaccination rates. N Engl J Med 2022; 386:2531–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Groom HC, Crane B, Naleway AL, et al. Monitoring vaccine safety using the vaccine safety datalink: assessing capacity to integrate data from immunization information systems. Vaccine 2022; 40:752–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tenforde MW, Chung J, Smith ER, et al. Influenza vaccine effectiveness in inpatient and outpatient settings in the United States 2015–2018. Clin Infect Dis 2021; 73:386–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tenforde MW, Talbot HK, Trabue CH, et al. Influenza vaccine effectiveness against hospitalization in the United States 2019–2020. J Infect Dis 2021; 224:813–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grijalva CG, Feldstein LR, Talbot HK, et al. Influenza vaccine effectiveness for prevention of severe influenza-associated illness among adults in the United States 2019–2020: a test-negative study. Clin Infect Dis 2021; 73:1459–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Izurieta HS, Lu M, Kelman J, et al. Comparative effectiveness of influenza vaccines among US Medicare beneficiaries ages 65 years and older during the 2019–2020 season. Clin Infect Dis 2021; 73:e4251–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Izurieta HS, Chillarige Y, Kelman J, et al. Relative effectiveness of influenza vaccines among the United States elderly 2018–2019. J Infect Dis 2020; 222:278–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gaglani M, Kim SS, Naleway AL, et al. Effect of repeat vaccination on immunogenicity of quadrivalent cell-culture and recombinant influenza vaccines among healthcare personnel aged 18–64 years: a randomized, open-label trial [published online ahead of print 29 August 2022]. Clin Infect Dis 10.1093/cid/ciac683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.