Abstract

Adenovirus (Ad) E4orf6/7, one of the early gene products of human Ads, forms a stable complex with the cellular transcription factor E2F to activate transcription from the Ad E2 promoter. E2F cDNAs have growth-promoting and apoptosis-inducing activities when overexpressed in cells. We cloned Ad5 E4orf6/7 cDNA in both simian virus 40- and human cytomegalovirus-based expression vectors to examine its transforming and apoptotic activities. The cloned E4orf6/7 collaborated with a retinoblastoma protein (RB)-nonbinding and therefore E2F-nonreleasing mutant of Ad5 E1A (dl922/947) to morphologically transform primary rat cells, suggesting that E2F is an important cellular protein functioning downstream of E1A for transformation. In a G418 colony formation assay, E4orf6/7 was shown to suppress growth of untransformed rat cells. Moreover, a recombinant Ad expressing Ad5 E4orf6/7 induced apoptosis in rat cells when coinfected with wild-type p53-expressing Ad. Mutational analysis of E4orf6/7 revealed that both of the domains required for growth inhibition and transformation by E4orf6/7 lay in the C-terminal region, which is essential for transactivation from the upstream sequence of an E2a promoter containing E2F-binding sites. However, the smallest mutant of E4orf6/7, encoding the C-terminal 59 amino acids, failed to complement the RB-nonbinding dl922/947 mutant despite showing growth inhibition and E2F transactivation activities. Thus, it is suggested that a subregion of E4orf6/7 which is required for growth inhibition and transformation in collaboration with dl922/947 overlaps the transactivation domain of E4orf6/7.

Many viruses encode their own antiapoptotic genes, which can suppress premature death of infected cells, thereby prolonging the survival of lytically infected cells and maximizing the production of viral progeny (56). When adenovirus (Ad) infects cells, immediate-early genes in the E1A transcription unit are expressed first, and then E1A activates expression of the other Ad early genes from the E1B, E2A, E2B, E3, E4, and L1 (early) transcription units (2). Among Ad early gene products, E1A possesses both growth-promoting and apoptotic activities (42, 69).

Ad E1A induces cellular DNA synthesis (26, 51, 80), immortalizes primary rodent cells (25), and transforms the cells in collaboration with Ad E1B19K, Ad E1B55K, Ad E4orf6, Bcl2, or activated Ras (40, 50, 54, 58, 61, 66). Three discontinuous domains, the N-terminal region and conserved region 1 (CR1) and CR2 of E1A, are required for ras-collaborative transformation by E1A (14, 17, 71, 72). The N-terminal region and part of CR1 are required for complex formation by E1A with p300/CBP (5, 14, 37, 72), and CR1 and CR2 are required for complex formation by E1A with retinoblastoma protein (RB) family members (14, 70).

Ad E1A also possesses strong p53-dependent apoptosis-inducing activity (11, 60). All viral and cellular genes which collaborate with E1A for transformation have antiapoptotic activity (22, 35, 50, 68) and/or inhibit the transactivation activity of p53 (13, 24, 77, 78). Ad E1A stabilizes the p53 tumor suppressor protein (7, 11, 36). In rat cells stably transfected with E1A plus the temperature-sensitive p53 gene, apoptosis is rapidly induced when p53 has changed from mutant to wild type (wt) (11). The domains of E1A required for induction of apoptosis overlap those necessary to induce cellular DNA synthesis, either CR1 and CR2 or the N-terminal region and part of CR1 (41, 67).

The Ad E4 region also contains multiple open reading frames which modulate transformation and apoptosis. E4 open reading frame 1 (E4orf1) of Ad serotype 9 (Ad9) and Ad10 (subgroup D), encoding a 14-kDa polypeptide, is responsible for estrogen-dependent mammary tumors in female rats (3, 4, 28–31). Moreover, when overexpressed, E4orf1 of not only Ad9 but also Ad2/5 and Ad12 can induce morphological transformation in rat cells (63, 64, 65). E4orf6, which has a transforming ability similar to that E1B19K or E1B55K, binds the C-terminal region of p53 and inhibits transactivation of p53 by inhibiting the ability of p53 to bind TAFII31, a TFIID component (13, 40). On the other hand, E4orf4, which binds protein phosphatase 2A and interferes with various mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways, was recently reported to affect cell viability and induce cell death, even in the absence of endogenous p53 (57). E4orf4-mediated apoptosis could be induced even in the presence of caspase inhibitor and in a p53-independent manner (34).

Another E4 gene product, E4orf6/7, was shown to form a stable complex with E2F on the E2F-binding sites in the Ad E2 promoter to induce transcription of E2 genes (27, 38, 45, 48, 52). In this study, we cloned Ad5 E4orf6/7 cDNA into the expression plasmids and an Ad vector to examine its growth-promoting and apoptotic activities. It was shown that the E4orf6/7 collaborated with an RB-nonbinding E1A mutant to transform primary rat cells and induced growth inhibition of rodent cells in the presence of wt p53. The functional domain of E4orf6/7 for growth inhibition and transformation was analyzed by constructing deletion mutants.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids.

pcD2-12S and pCMV-12S were constructed by inserting the 12S cDNA of Ad5 E1A (79) into the simian virus 40 (SV40)-based expression vector pcD2-Y (8, 46) and into the human cytomegalovirus (HCMV)-based expression vector pCMV-NeoBam (6), respectively. Plasmid pCMV-19K contains the Ad5 small E1B (E1B19K) (66). pcD2-598 and pcD2-922/947 were constructed by inserting E1A12S mutants NTdl598 and dl922/947 (72) separately into pcD2-Y. p5XbaC is a plasmid carrying the Ad5 E4 region (21). pJM17 (39), a plasmid containing the genomic sequence of Ad5, was purchased from Microbix Biosystems Inc. (Toronto, Ontario, Canada). pAdCMV·BglII was made from pAd-BglII (kindly provided by M. Imperiale, Michigan University) by inserting the HCMV early promoter-multiple cloning site-poly(A) signal sequence of bovine growth hormone prepared from pRc/CMV (Invitrogen). This pRc/CMV-derived unit is flanked by Ad5 E1 sequences (nucleotides [nt] 1 to 356 and 3329 to 5788 [62]) (59) in pAdCMV·BglII. pAdCMV-p53, pAdCMV-E1A, and pAdCMV-E4orf6/7 were constructed by inserting each cDNA fragment of wt p53 (1.8-kb BamHI fragment of pC53-SN3 [32]), Ad5 E1A12S (from pCMV-12S) (79), and E4orf6/7, respectively into pAdCMV·BglII. pE2(ATF−)-CAT, containing the chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) gene under the Ad E2 promoter from which an ATF site was deleted, was kindly provided by J. R. Nevins (Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C.).

Cell culture and transfection.

Human 293 cells, which express Ad5 E1A and E1B, were derived from human embryonic kidney cells (20) and were used for construction and propagation of recombinant Ads. Primary cultures of baby rat kidney (BRK) and rat embryo fibroblast (REF) cells were prepared from F-344 rat embryonic kidney and whole embryos, respectively, as described previously (75). 3Y1 cells were derived from Fisher rat embryonic fibroblasts. 10(1) cells, derived from BALB/c mouse embryonic fibroblasts, are deficient for p53 expression (23). NRK cells (immortalized rat [Rattus norvegicus] kidney cells) were used for flow cytometry. CV1 cells, derived from African green monkey kidney, were used for CAT assay. Cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS), streptomycin (40 μg/ml), and penicillin (100 U/ml) except where noted otherwise. DNA transfection was performed by the standard calcium phosphate coprecipitation technique described by Graham and van der Eb (19), with a slight modification. Five hours after transfection, transfected cells were exposed to 15% glycerol in HEPES buffer for 1 min (73).

Cloning of Ad5 E4orf6 and E4orf6/7 cDNAs.

Total cellular RNA was isolated from KBIII cells infected with Ad5 (Adenoid 75 strain) 4 h after infection. cDNA was synthesized from 5 μg of RNA by using Rous-associated virus-2 (RAV) reverse transcriptase (TaKaRa Biomedicals), and then E4orf6 and E4orf6/7 were specifically amplified by Expand High Fidelity (Boehringer Mannheim) with specific primer pairs. Sense primer E4orf6fw (5′-GCC GAA TTC AAT ATG ACT ACG TCC GGC GT-3′ [Ad2 E4 nt 8444 to 8428 [62]) and antisense primer E4orf6rv (5′-GGC GGA TCC CGC CTA CAT GGG GGT AGA GT-3′ [Ad2 E4 nt 7557 to 7576 [62]) were used for amplification of E4orf6. Sense primer E4orf6fw and antisense primer E4orf7rv (5′-GGC GGA TCC AAC TCA CAG AAC CCT AGT AT-3′ [Ad2 E4 nt 7281 to 7297 [62]) were used for amplification of E4orf6/7 (EcoRI and BamHI sites are underlined). The amplified DNA fragments were cleaved with EcoRI and BamHI and inserted into the pUC19 vector. Cloned DNAs were evaluated by the dideoxy-chain termination method using a Sequenase version 2.0 DNA sequencing kit (United States Biochemical) and an Applied Biosystems model 373S DNA sequencing system (Perkin-Elmer).

Construction of Ad5 E4orf6/7 mutants.

All Ad5 E4orf6/7 mutants constructed in this study were designated according to the two deletion endpoints (Fig. 1). Four deletion mutants, dl9/115, dl9/274, dl285/451, and dl309/451, were constructed by PCR, using primer pairs E4dl9/115fw (5′-GCC GAA TTC AAT ATG ACT ACG GCT ACC ATA CTG GAG GAT CAT-3′)-E4orf7rv for dl9/115, E4dl9/274fw (5′-GCC GAA TTC AAT ATG ACT ACG GGG GAG TTT ATT AAT ATC ACT-3′)-E4orf7rv for dl9/274, E4orf6fw-E4dl285/451rv (5′-GGC GGA TCC AAC TCA AAT AAA CTC CCC GGG CAG CTC ACT TAA-3′) for dl285/451, and E4orf6fw-E4dl309/451rv (5′-GGC GGA TCC AAC TCA AGC CAA ACG CTC ATC AGT GAT A) for dl309/451. The other two mutants, dl177/241 and dl240/310, were constructed by cleaving the E4orf6/7 cDNA fragment with restriction enzyme pairs MluI-PvuII and PvuII-TaqI, respectively, filling in the ends with Klenow polymerase, and ligating the blunt ends with T4 DNA ligase. All of the mutant constructs were cleaved with EcoRI and BamHI and inserted into pUC19. After the deletion sites were confirmed by DNA sequencing, they were cloned into the expression vectors pcD2-Y and pCMV-NeoBam. The structures of E4orf6/7 mutants are shown in Fig. 1.

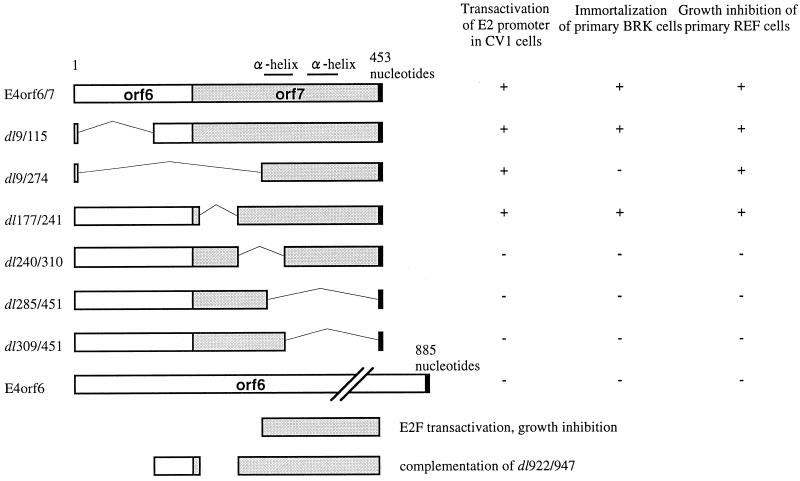

FIG. 1.

Schematic diagram of wt and mutant E4orf6/7 constructs and wt E4orf6. E4orf6/7 consists of 453 nt (the top diagram). Two putative α helices in the C terminus of E4orf6/7 are indicated by horizontal bars above wt E4orf6/7. Amino acid-encoding regions are indicated by empty and shaded boxes, and deletion sites are marked by circumflex bars. Two C-terminus deletion mutants, dl285/451 and dl309/451, also have a TGA stop codon at the 3′ end (indicated by black boxes). Deletion sites of dl9/115, dl9/274, and dl177/241 are identical to those of some mutants designed by O’Connor and Hearing (49).

Immunoblotting.

The wt and mutant E4orf6/7 cDNAs were fused with hemagglutinin epitope (HA) and cloned into the expression vector pcDNA3. SV40 large-T-expressing 293T cells were transfected in 10-cm-diameter plates with 16 μg of the vectors by calcium phosphate coprecipitation and harvested at 48 h posttransfection. Cells were lysed in 400 μl of lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 150 mM NaCl, 0.02% sodium azide, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, aprotinin [1 μg/ml], leupeptin [1 μg/ml], phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (100 μg/ml]). Lysates were boiled in sodium dodecyl sulfate loading buffer and applied to a 15% polyacrylamide gel for electrophoresis. After transfer to an Immobilon-P transfer membrane (Millipore), protein expression was detected with mouse monoclonal anti-HA antibody 12CA5 (Boehringer Mannheim). Proteins were then detected with a goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G second antibody conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (Promega) by visualizing by fluorography using enhanced chemiluminescence Western blotting detection reagents (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

Construction of recombinant Ads.

Recombinant Ad-LacZ was kindly provided by M. Imperiale. Ad-p53, Ad-E1A, and Ad-E4orf6/7 are recombinants which express wt p53, Ad5 E1A12S, and Ad5 E4orf6/7, respectively (76). To generate recombinants Ad-p53, Ad-E1A, and Ad-E4orf6/7, 293 cells were cotransfected with pJM17 and each of pAdCMV-p53, pAdCMV-E1A, and pAdCMV-E4orf6/7 by using LipofectAMINE (GIBCO BRL) and cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 3% FBS for 2 to 4 weeks. Each virus was cloned from a single plaque formed in 293 cells. 293 cells infected with Ad-LacZ, Ad-p53, Ad-E1A, or Ad-E4orf6/7 were collected with cultured medium, freeze-thawed, aliquoted into serum tubes, and frozen as viral stocks until use. Viral titers (5 × 108 to 10 × 108 PFU/ml) were determined by infecting 293 cells with diluted viral stocks.

Flow cytometry.

NRK cells (5 × 105 in 6-cm-diameter dishes) were infected with Ad-LacZ, Ad-p53, Ad-E1A, and Ad-E4orf6/7 (10 PFU/cell) and cultured for 48 h. Cells were harvested, washed in ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4), and fixed briefly in ice-cold 70% ethanol (5 ml). Cells were then washed once with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline and treated with RNase A (500 U/ml; Sigma) at 37°C for 15 min prior to propidium iodide (50 μg/ml; Sigma) staining. The apoptotic cell fraction in 2 × 104 cells was quantified by flow cytometry using a FACScan instrument (Becton Dickinson) with Consort 30 software (Becton Dickinson).

G418 colony assay.

Primary REF, 3Y1, and 10(1) cells (5 × 105 of each in 6-cm-diameter dishes) were transfected with 5 μg of pCMV-NeoBam and pAdCMV·BglII, p5XbaC, or pAdCMV-E4orf6/7, split into two to five 10-cm-diameter dishes, and cultured in DMEM containing 5% FBS and 350 μg of G418 (GIBCO BRL) per ml for 14 days. After the cells had been fixed with methanol and stained with Giemsa stain, the number of G418-resistant colonies was counted. E4orf6/7 mutational analysis using primary REF cells was performed in the same manner.

CAT assay.

CAT assay was performed by the method of Gorman et al. (18). CV1 cells cultured subconfluently in 10-cm-diameter dishes were transiently transfected by the calcium phosphate coprecipitation method with 5 μg of pE2(ATF−)-CAT, 5 μg of pCMV-12S, and 5 μg of p5XbaC (whole E4) or 5 μg of pCMV-E4orf6, pCMV-E4orf6/7, or one of the pCMV-E4orf6/7 mutants. The total amount of transfected DNA was adjusted to 15.0 μg by adding pCMV-NeoBam. Cells were cultured for 48 h at 37°C. Cellular extracts were prepared and assayed for CAT activity. The conversion rates were determined with an image analyzer (Fuji BAS2000).

RNA preparation and reverse transcriptase-mediated PCR (RT)-PCR.

Total RNA was isolated by the acid guanidinium-phenol-chloroform method (9) and was reverse transcribed with RAV-2 reverse transcriptase (TaKaRa Biomedicals) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. For the detection of E4orf6/7, E4orf6/7 mutant, and rat β-actin, 1/10 volume of cDNA (5 μl) was used for PCR amplification. Primers E4orf6fw and E4orf7rv were used for detection of E4orf6/7 and dl177/241; were used for detection of dl9/115 primers E4dl9/115fw and E4orf7rv. The β-actin-specific primers were rβa-1 (forward) (5′-AGC CAT GTA CGT AGC CAT CC-3′ [nt 2182 to 2202] [47]) and rβa-2 (reverse) (5′-CAT TGC CGA TAG TGA TGA CC-3′ [nt 2549 to 2529] [47]).

RESULTS

Cloning of Ad5 E4orf6 and E4orf6/7 cDNAs.

We cloned Ad5 E4orf6 and E4orf6/7 cDNAs into the EcoRI-BamHI site of pUC19; the resultant plasmids were designated pUC-E4orf6 and pUC-E4orf6/7, respectively, and their sequences were determined. In the cloned E4orf6, six nucleotides, at codons 29, 36, 85, 134, 244, and 245, were different from the Ad2 sequence reported (62) without amino acid changes. The E4orf6 in pUC19 was subcloned into the expression vector pCMV-NeoBam. In the cloned E4orf6/7, four nucleotides, at codons 29, 36, 62, and 88, were different from the prototype Ad2 sequence (62) without amino acid changes, but glutamic acid at codon 68 (GAG in prototype Ad2) (62) was replaced by lysine (AAG in our clone). The E4orf6/7 in pUC19 was subcloned into the expression vectors pcD2-Y and pCMV-NeoBam and also into the vector pAdCMV·BglII. A recombinant containing Ad5 E4orf6/7 was constructed as described in the Materials and Methods.

E4orf6/7 enhances E2 transactivation.

In addition to E1A, E4 is known to function as a transactivator of the E2 promoter (43, 53). The experiment shown in Fig. 2A demonstrates the role of the E4 gene in transactivation of the E2 promoter. When p5XbaC (Ad5 E4 fragment) was cotransfected with pE2(ATF−)-CAT and pCMV-12S into CV1 cells, CAT activity was 8.9-fold greater than that without p5XbaC (Fig. 2A, lanes 1 and 2). To investigate whether the cloned E4s were biochemically functional, pE2(ATF−)-CAT was cotransfected with pCMV-12S, pCMV-E4orf6/7, or pCMV-E4orf6 into CV1 cells. pCMV-12S alone enhanced pE2(ATF−)-CAT activity about threefold (Fig. 2B and C, lanes 1 and 2). When pCMV-E4orf6/7 was cotransfected with pE2(ATF−)-CAT and pCMV-12S, CAT activity was 6.5-fold greater than that without E4orf6/7 (Fig. 2B and C, lanes 2 and 3). pCMV-E4orf6 had a negative effect on CAT activity (Fig. 2B and C, lane 4). These results confirmed that the cloned E4orf6/7 transactivates the E2 promoter as reported by Neill et al. (43).

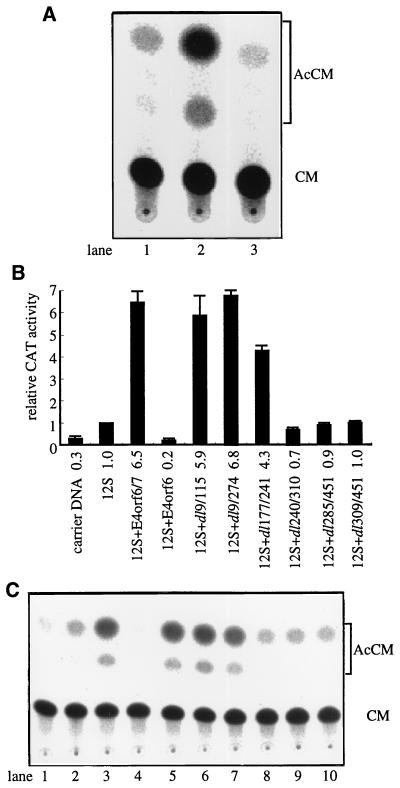

FIG. 2.

Effects of wt and mutant E4s on pE2(ATF−)-CAT expression. (A) Representative result of CAT assay. CV1 cells were cotransfected with 5.0 μg of pE2(ATF−)-CAT, 5.0 μg of pCMV-12S, and 5.0 μg of p5XbaC. Lanes: 1, pCMV-12S; 2, pCMV-12S plus p5XbaC; 3, pCMV-NeoBam. (B) Diagrammatic representation of E2F-dependent CAT assay. (C) Representative result of CAT assay. CV1 cells were cotransfected with 5.0 μg of pE2(ATF−)-CAT, 5.0 μg of pCMV-12S, and 5.0 μg each of the pCMV-E4 genes. The results are expressed as CAT activities relative to that of pE2(ATF−)-CAT plus pCMV-12S (lane 2). Other lanes: 1, pCMV-NeoBam; 3, pCMV-12S plus pCMV-E4orf6/7; 4, pCMV-12S plus pCMV-E4orf6; 5, pCMV-12S plus pCMV-dl9/115; 6, pCMV-12S plus pCMV-dl9/274; 7, pCMV-12S plus pCMV-dl177/241; 8, pCMV-12S plus pCMV-dl240/310; 9, pCMV-12S plus pCMV-dl285/451; 10, pCMV-12S plus pCMV-dl309/451. AcCM, acetylchloramphenicol; CM, chloramphenicol.

We then examined the effect of E4orf6/7 mutants on E1A-induced E2 transactivation and determined the minimum region within E4orf6/7 sufficient for this function. When dl9/115, dl9/274, and dl177/241, whose products encompass at least the C-terminal 59 amino acids of E4orf6/7, were cotransfected with pE2(ATF−)-CAT and pCMV-12S, CAT activity was increased as effectively as that of wt E4orf6/7 (4.3- to 6.8-fold [Fig. 2B and C, lanes 5 to 7). Meanwhile, dl240/310, dl285/451, and dl309/451, which lacked all or part of the C-terminal region, did not enhance CAT activity (Fig. 2B and C, lanes 8 to 10). The same tendency was observed in experiments with 293T, HeLa, and 10(1) cells (data not shown). These observations indicate that the C-terminal 59 amino acids of E4orf6/7 are essential and sufficient for the enhancement of E1A-induced E2 transactivation.

Expression of wt and mutant E4orf6/7 constructs.

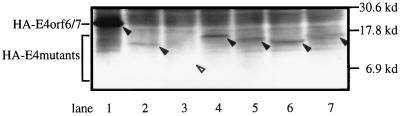

Introduction of substantial deletions might greatly influence protein stability. To examine whether wt and mutant E4orf6/7 constructs were expressed as proteins in transfected cells, the initial methionine plus the HA epitope were fused in frame to the N termini of the E4 cDNAs, and levels of protein expression were investigated by immunoblotting. The expression of E4orf6/7 was easily detected as band of reasonable size (18.3 kDa), (Fig. 3, lane 1), suggesting that E4orf6/7 protein was stably expressed in the cells. E4orf6/7 mutants were also expressed in transfected cells, but to a level lower than that of wt E4orf6/7 (Fig. 3, lanes 2 to 7). In particular, the expression of dl9/274 in cells was not visually detectable as a clear band even though its translated protein and transactivation activity were confirmed by HA-tagged plasmids in an in vitro transcription-translation system (Promega) and by CAT assay, respectively (data not shown). These findings strongly suggest that small quantities of wt E4orf6/7 as well as C-terminally conserved E4orf6/7 mutants (dl9/115 and dl9/274) may be enough for its transactivation and that the disappearance of transactivation in C-terminal deletion mutants (dl285/451 and dl309/451) may be attributable not to the instability of these mutant proteins but to lack of a transactivation domain.

FIG. 3.

Expression of HA-tagged E4 proteins. 293T cells were transfected with 16.0 μg each of expression plasmids carrying each gene. HA-tagged E4 proteins are indicated by black arrowheads. Expression of dl9/274 in cells is not visually detectable; the empty arrowhead indicates the putative size of this protein. Constructs tested were E4orf6/7 (18.3 kDa; lane 1), dl9/115 (14.2 kDa; lane 2), dl9/274 (8.4 kDa; lane 3), dl177/241 (16.0 kDa; lane 4), dl240/310 (15.7 kDa; lane 5), dl285/451 (11.9 kDa; lane 6), and dl309/451 (12.8 kDa; lane 7).

Complementation of RB-nonbinding E1A mutant by E4orf6/7.

E1A transactivates E2F site-containing promoters by forming a complex with RB to release E2F, while E4orf6/7 can enhance E2F-dependent transcription by its ability to form a stable complex with E2F on the E2F-binding sites (43, 48). To test whether E4orf6/7 could complement the RB-binding function of E1A, primary BRK cells were transfected with E4orf6/7 and an RB-nonbinding mutant of Ad5 E1A (dl922/947) with or without E1B19K (Table 1). Primary BRK cells did not produce G418-resistant colonies after transfection with pcD2-Y (empty vector), E1B19K, E4orf6/7, or E4orf6/7 plus E1B19K. E1A (Ad5 12S cDNA) and a combination of p300/CBP-nonbinding NTdl598 and RB-nonbinding dl922/947 produced G418-resistant colonies, some of which were established into cell lines. Cotransfection of E1B19K (E1A-E1B19K and NTdl598-dl922/947-E1B19K) increased G418-resistant colony formation. None of the BRK cell clones generated after transfection of NTdl598, NTdl598-E1B19K, dl922/947, dl922/947-E1B19K, NTdl598-E4orf6/7, or NTdl598-E4orf6/7-E1B19K could be established into cell lines. On the other hand, BRK cells transfected with dl922/947-E4orf6/7 and BRK cells transfected with dl922/947-E4orf6/7-E1B19K produced G418-resistant colonies which were also established into cell lines (designated BRK-922/E4 and BRK-922/E4/19K) (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Colony formation of primary BRK cells transfected with adenovirus genesa

| Plasmid(s) | No. of G418-resistant colonies

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Expt 1 | Expt 2 | Total | |

| pcD2Y (control) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| E1B19K | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| E1A | 19 | 15 | 34b |

| E1A + E1B19K | 34 | 78 | 112b |

| NTdl598 (p300/CBP nonbinding) | 6 | 6 | 12c |

| NTdl598+E1B19K | 13 | 15 | 28c |

| dl922/947 (RB nonbinding) | 6 | 6 | 12c |

| dl922/947+E1B19K | 9 | 18 | 27c |

| E4orf6/7 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| E4orf6/7+E1B19K | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| NTdl598+dl922/947 | 13 | 13 | 26b |

| NTdl598+dl922/947+E1B19K | 73 | 87 | 160b |

| NTdl598+E4orf6/7 | 1 | 1 | 2c |

| NTdl598+E4orf6/7+E1B19K | 2 | 2 | 4c |

| dl922/947+E4orf6/7 | 9 | 9 | 18b |

| dl922/947+E4orf6/7+E1B19K | 12 | 16 | 28b |

pcD2Y, E1A (pcD2-12S), NTdl598 (pcD2-598), dl922 (pcD2-922/947), and E4orf6/7 (pcD2-E4orf6/7) contain G418-resistant genes. Primary BRK cells in 10-cm-diameter dishes were transfected with plasmid(s) (5.0 μg of each), split to four dishes, and cultured in medium containing G418 (150 μg/ml) for 3 weeks.

Cell line was established from G418-resistant colonies for further analysis.

Colonies were not established into cell lines.

These BRK cell lines showed a morphology indistinguishable from that E1A-transformed cell line BRK-12S (data not shown). Mean saturation densities of BRK-12S and BRK-922/E4 were less than 105 cells/cm2, while those of BRK-12S/19K and BRK-922/E4/19K were higher than 1.5 × 105 cells/cm2. Thus, E4orf6/7 was shown to complement the RB-nonbinding E1A mutant to immortalize and transform primary BRK cells, and the resulting cell lines possessed a phenotype similar to that of E1A- or E1A-19K-expressing cells.

The C terminus of E4orf6/7 is essential for complementation of the RB-binding function of E1A.

We also investigated the effect of E4orf6/7 mutants on the complementation of RB-nonbinding E1A mutant. Combinations of dl922/947 plus E4dl9/115 and dl922/947 plus E4dl177/241 were able to produce G418-resistant colonies which were transferable as cell lines in the presence of E1B19K (designated BRK-922/dl9/115 and BRK-922/dl177/241, respectively) (Table 2). None of the combinations of dl922/947 plus one of the E4orf6/7 mutants with a deleted C terminus could produce transferable colonies, even in the presence of E1B19K (Table 2). dl9/274, which carries intact C terminus and enhances E1A-induced E2 transactivation, failed to complement the RB-nonbinding E1A mutant for immortalization (Table 2; Fig. 1).

TABLE 2.

Immortalization of primary BRK cells by RB-nonbinding E1A and E4orf6/7 mutants

| Plasmid dl922/947 + E1B19K +: | No. of G418-resistant colonies | Establishment of cell line | Designation of cell line established |

|---|---|---|---|

| E4orf6/7 | 61 | + | BRK-922/E4 |

| E4orf6 | 1 | − | |

| dl9/115 | 39 | + | BRK-922/dl9/115 |

| dl9/274 | 1 | − | |

| dl177/241 | 46 | + | BRK-922/dl177/241 |

| dl240/310 | 2 | − | |

| dl285/451 | 2 | − | |

| dl309/451 | 1 | − |

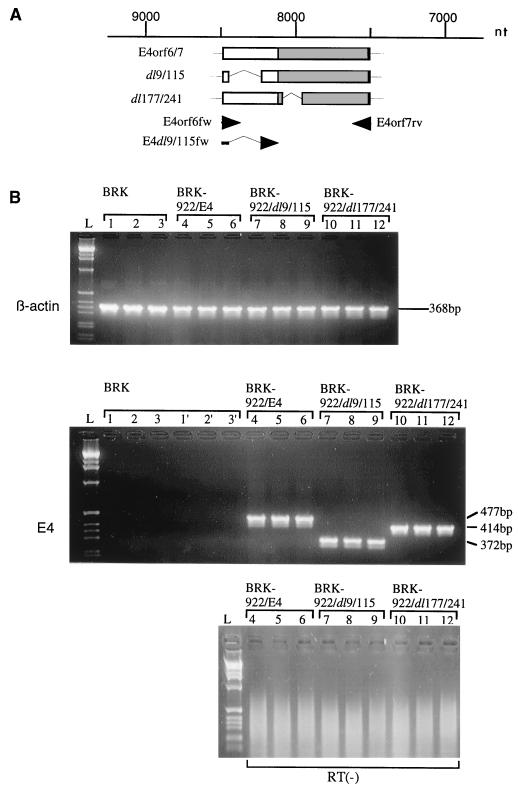

To examine whether the transfected viral genes were transcribed in the established BRK-922/E4, BRK-922/dl9/115, and BRK-922/dl177/241 cell lines, we prepared cytoplasmic RNA from the BRK cell lines and performed RT-PCR with E4-specific primer pairs (Fig. 4B). From the BRK-922/E4 cells, PCR using E4orf6fw plus E4orf7rv was expected to amplify a 477-bp fragment which represents E4orf6/7 mRNA. Similarly, from the BRK-922/dl9/115 and BRK-922/dl177/241 cell lines, E4dl9/115fw-E4orf7rv and E4orf6fw-E4orf7rv were expected to amplify 372- and 414-bp fragments representing the dl9/115 and dl177/241 mRNAs, respectively. As expected, RT-PCR detected 477, 372, and 414-bp bands from BRK-922/E4, BRK-922/dl9/115, and BRK-922/dl177/241 cell lines, respectively (Fig. 4B).

FIG. 4.

RT-PCR analysis of E4 transcripts in immortalized BRK cell lines. (A) Schematic structure of wt and mutant E4orf6/7 mRNAs (see also Fig. 1). Nucleotide numbering is based on the DNA sequences determined by van Ormondt and Galibert (62). Arrowheads represent the 3′ ends of the primers. (B) Lane L, GIBCO 1-kb ladder; lanes 1 to 3, primary BRK cells as a negative control using the E4orf6fw-E4orf7rv primer set; lanes 1′ to 3′, primary BRK cells as a negative control using the E4dl9/115fw-E4orf7rv primer set; lanes 4 to 6, BRK-922/E4 cells as a positive control; lanes 7 to 9, BRK-922/dl9/115 cells; lane 10 to 12, BRK-922/dl177/241 cells.

E4orf6/7 cDNA inhibits colony formation and induces apoptosis.

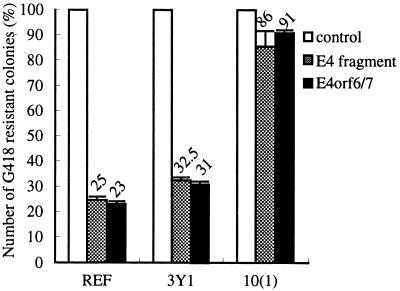

E2F cDNAs can induce apoptosis when overexpressed (33), which suggests that Ad5 E4orf6/7, as well as E1A, may promote a pathway involving E2F to induce apoptosis in the presence of wt p53. To test whether E4orf6/7 could induce growth inhibition or apoptosis, we examined the effect of E4orf6/7 on cell viability in REF, 3Y1, and 10(1) cells (Fig. 5). We found that cloned E4orf6/7 cDNA showed growth inhibition of cells at almost the same level as the Ad5 E4 fragment (p5XbaC). Growth-inhibitory activity of E4orf6/7 was observed in primary REF and 3Y1 cells, while no remarkable effects were seen in p53-null 10(1) cells, suggesting that the inhibition of cell growth by E4orf6/7 was dependent on wt p53.

FIG. 5.

Abilities of Ad5 genes to inhibit colony formation in vitro. Primary REF, 3Y1, and 10(1) cells were transfected with 5.0 μg each of expression plasmids carrying each gene and selected by G418. The experiment was performed twice, and the mean was evaluated by ratio compared to the control (pAdCMV·BglII plus pCMV-NeoBam) E4 fragment, p5XbaC plus pCMV-NeoBam, E4orf6/7, pAdCMV-E4orf6/7 plus pCMV-NeoBam.

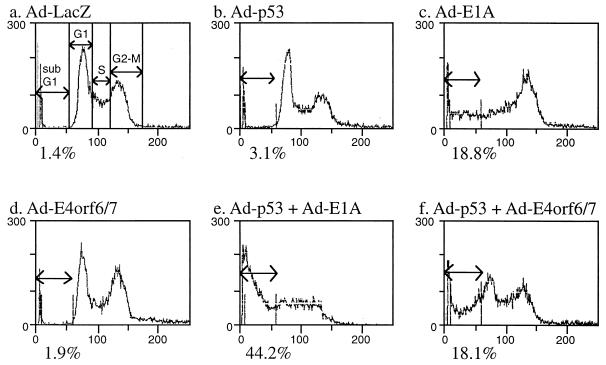

To test whether the growth inhibition of E4orf6/7 is due to apoptotic cell death, we quantified by flow cytometry the cell distribution in populations infected with the E4orf6/7-expressing recombinant Ad-E4orf6/7 along with wt p53-expressing Ad-p53 (Fig. 6). E1A alone induced apoptosis in NRK cells (Fig. 6c), while wt p53 and E4orf6/7 could generate only background levels of a sub-G1 fraction (Fig. 6b and d). However, if wt p53 is overexpressed by coinfection with Ad-p53, E4orf6/7 can induce apoptosis at the same level as E1A (Fig. 6f). This result suggests that E4orf6/7 has the potential to induce apoptosis when wt p53 is overexpressed.

FIG. 6.

Flow cytometric analysis of NRK cells upon recombinant Ad infection. NRK cells were infected with recombinant Ad expressing E1A12S, p53, and E4orf6/7. The percentage of cells displaying a DNA content less than that of G1 cells in the analysis is quantified as an apoptotic index. Ad-LacZ served as a negative control.

Growth inhibition by E4orf6/7 requires E2F binding to the E4orf6/7 C terminus.

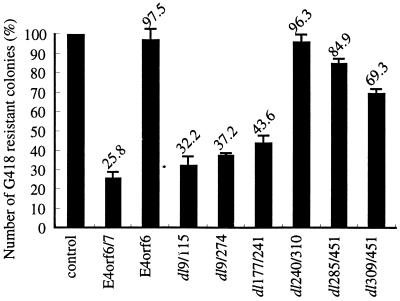

The results described above showed p53-dependent apoptotic activity of E4orf6/7. To determine the structural domains of E4orf6/7 necessary for the induction of p53-dependent apoptosis, we examined the effect of E4orf6/7 mutants on the growth of cells by G418 colony formation assay (Fig. 7). When E4orf6/7 or one of the mutants containing the C-terminal region (dl9/115, dl9/274, and dl177/241) was transfected, colony formation in primary REF cells was suppressed. However, little suppression was detected in a mutant which lacked the C-terminal region (dl309/451). Thus, it is strongly suggested that the C-terminal 59 amino acids within E4orf7 contain a structural domain necessary not only for the transactivation of E2F-containing promoters and complementation of RB-nonbinding E1A mutants for transformation but also for p53-dependent apoptosis.

FIG. 7.

Abilities of wt and mutant E4s to inhibit colony formation in vitro. Primary REF cells were transfected with 5.0 μg each of pCMV-NeoBam plasmids carrying each gene and selected by G418 in vitro. The experiment was performed three times, and the mean was evaluated by ratio compared to the control (pCMV-NeoBam). E4orf6/7, pCMV-E4orf6/7; E4orf6, pCMV-E4orf6; dl9/115, pCMV-dl9/115; dl9/274, pCMV-dl9/274; dl177/241, pCMV-dl177/241; dl240/310, pCMV-dl240/310; dl285/451, pCMV-dl285/451; dl309/451, pCMV-dl309/451.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we cloned Ad5 E4orf6/7 cDNA and studied its biological and biochemical activities. The 58 amino acid residues from the N terminus, which constitutes 40% of E4orf6/7, are identical to those of E4orf6, while the 92 amino acid residues from the C terminus, which constitutes 60% of E4orf6/7, are specific for E4orf6/7 (10) (Fig. 1). The Ad2/5 E4orf6/7 has been reported to form a stable complex with transcription factor E2F on the E2F-binding sites (27, 38, 45, 48, 52) through a putative double α-helix motif in the C-terminal region of the E4orf6/7 polypeptide (44, 49). In an experiment using deletion mutants, the transactivation domain of E4orf6/7 was mapped within the double α-helix structure in its C-terminal region (44, 49). We also mapped the transactivation domain of E4orf6/7 to the smaller 59 amino acids of its C terminus, which was sufficient for E2 transactivation enhancement (Fig. 1 and 2).

Unlike Ad2 E4orf6/7, Ad5 E4orf6/7 has a significant amino acid change at codon 68 (glutamic acid to lysine). C-terminal deletion of Ad2 E4orf6/7 has been reported to reduce transactivation activity even in the presence of conserved codon 68 (49). However, no significant difference in transactivation activity between wt E4orf6/7 and its internal mutant with deletion of 21 amino acid residues (codons 60 to 80) was observed in the case of Ad2 (49). Our investigation using Ad5 E4orf6/7 and its deletion mutants showed the same tendency (Fig. 2B). These findings strongly suggest that the amino acid change in E4orf6/7 at codon 68 between Ad2 and Ad5 is not essential for the transactivation activity of E4orf6/7.

We found that like E1A, E4orf6/7 had both growth-promoting and growth-inhibitory activities. Although E4orf6/7 alone did not immortalize primary rat cells or induce morphological transformation, it could complement an RB-nonbinding E1A mutant, dl922/947, to induce immortalization and morphological transformation of primary BRK cells (Fig. 1; Table 1). Since the C-terminal region containing discontinuous segments from amino acid residues 39 to 59 and from amino acid residues 81 to 150 of E4orf6/7 could complement RB-nonbinding E1A mutant dl922/947 to transform BRK cells and no complementation of p300-nonbinding E1A mutant NTdl598 by E4orf6/7 was detectable, it is likely that the E2F-binding ability of E4orf6/7 is responsible for its collaborative transforming activity. Growth-inhibitory activity of Ad5 E4orf6/7 was shown in primary and established rat cells at the same efficiency as for the Ad5 E4 fragment (Fig. 5). Since these activities were not detectable in Ad5 E4orf6 (Fig. 1 and 7; Table 2), both activities may be localized in the E4orf6/7 C-terminal region. The smallest mutant of E4orf6/7, dl9/274, which encoded only the C-terminal 59 amino acids, showed both E2F transactivation and growth-inhibitory activities at levels the same as or higher than those of other mutants (Fig. 2 and 7), suggesting that growth inhibition of E4orf6/7 may be mediated through E2F fixation on E2F-binding sites of cellular genes which might promote G1/S transition. However, the relevance of the association of E2F with the C terminus of E4orf6/7 to transactivation or growth inhibition is still unclear. Gel shift assay or coimmunoprecipitation may clarify this matter.

Meanwhile, complementation of the RB-nonbinding mutant of Ad5 E1A was detected in dl9/115 and dl177/241 but not in the smallest mutant, dl9/274 (Table 1). It is believed that Ad E1A immortalizes primary rodent cells by forming complexes with cellular proteins including p300/CBP and RB family members (42, 69). In addition to these cellular proteins, Ad E1A binds cyclin A/cdk2 and cyclin E/cdk2 through CR1 and CR2 (15, 16). Therefore, complementation of the RB-nonbinding mutant of E1A, dl922/947, may require multiple functions including complex formation with RB and cyclin/cdk family members, and it is suggested that the E4orf6/7 C terminus may not have all functions necessary for this complementation.

Our results also suggest that the inability of dl9/274 to transform cells may be due to its lower level of protein expression. As described in Results, the expression of dl9/274 in cells was not visually detected as a clear band. In addition, the expression level of wt E4orf6/7 and the C-terminally conserved mutants seemed to affect the efficiency of colony formation or the establishment of transformed cells (Fig. 3; Table 2). These findings imply that E4orf6/7 may complement the RB-nonbinding mutant of E1A through some unknown function other than E2F fixation. Further study to resolve this question is in progress.

The heterologous combination of dl922/947 and E4orf6/7 seems to transform BRK cells with a lower efficiency than the homologous combination of E1A mutants NTdl598 and dl922/947 (Table 1). Cotransfection of E1B19K with this heterologous combination did not enhance BRK transformation to the level of cotransfection of NTdl598, dl922/947, and E1B19K (Table 1). In the homologous combination of E1A mutants, E2F might be released from the RB-E2F complex by the RB-binding function of NTdl598. Meanwhile, in the heterologous combination, E4orf6/7 might stabilize E2F on the cellular promoters containing E2F-binding sites. The results suggest that the E2F-releasing function of E1A may contribute more efficiently than the E2F fixation function of E4orf6/7 to transformation of primary BRK cells.

It has been reported that one member of the E2F family, E2F-1, can form a complex with E4orf6/7 and transactivate the E2 promoter (48). It has also been reported that E2F-1 can induce both p53-dependent apoptosis in fibroblasts (33, 74) and p53-independent apoptosis in myocytes (1). Although cell growth inhibition by E4orf6/7 was observed in REF cells (Fig. 5), E4orf6/7 alone did not induce a sub-G1 fraction in NRK, 3Y1, or even REF cells (Fig. 6 for NRK; data not shown for 3Y1 and REF). Therefore, a high level of p53 expression may be necessary for E4orf6/7-induced apoptosis, and the apoptotic activity of E4orf6/7 itself may be very weak.

Cellular genes which are required for G1/S progression contain E2F-binding sites in their upstream regulatory sequence (45). Among these genes, the promoters for those encoding cyclin A and cyclin E also have E2F-binding sites. Increased expression and activity of the cyclin A and cyclin E genes have been reported to be inducible by the ectopic expression of E2F-1 (12). The result of the cyclins and associated kinase activity may be, at least in part, responsible for releasing more E2F-1 through phosphorylation of RB and for consequent S-phase entry (15). However, E2F-1 apoptosis seems to require full activation of the E2F-1 function. Although no apoptotic activity was detected in DP-1 alone, coexpression of DP-1 with E2F-1 significantly augmented the percentage of apoptotic cells (55). Like DP-1, which is capable of forming a heterodimer with E2F-1, E4orf6/7 seems to facilitate E2F-1 induction of apoptosis (Fig. 2 and 5). Consistent with these findings, our results imply that the molecular function of Ad2/5 E4orf6/7 could be a clue to elucidate the mechanism of E2F-1-induced apoptosis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank B. Vogelstein for providing pC53-SN3, E. White for pCMV-19K, Y. Sawada for p5XbaC, M. J. Imperiale for pAd-BglII and Ad-LacZ, and J. R. Nevins for pE2(ATF−)-CAT.

This work was supported in part by a grant-in-aid from The Ministry of Education, Science and Culture of Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agah R, Kirshenbaum L A, Abdellatif M, Truong L D, Chakraborty S, Michael L H, Schneider M D. Adenoviral delivery of E2F-1 directs cell cycle reentry and p53-independent apoptosis in postmitotic adult myocardium in vivo. J Clin Investig. 1997;100:2722–2728. doi: 10.1172/JCI119817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akusjarvi G. Proteins with transcription regulatory properties encoded by human adenoviruses. Trends Microbiol. 1993;1:163–170. doi: 10.1016/0966-842x(93)90085-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ankerst J, Jonsson N, Kjellen L, Norrby E, Sjogren H O. Induction of mammary fibroadenomas in rats by adenovirus type 9. Int J Cancer. 1974;13:286–290. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910130303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ankerst J, Jonsson N. Adenovirus type 9-induced tumorigenesis in the rat mammary gland related to sex hormonal state. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1989;81:294–298. doi: 10.1093/jnci/81.4.294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arany Z, Newsome D, Oldread E, Livingston D M, Eckner R. A family of transcriptional adaptor proteins targeted by the E1A oncoprotein. Nature. 1995;374:81–84. doi: 10.1038/374081a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baker S J, Markowitz S, Fearon E R, Willson J K, Vogelstein B. Suppression of human colorectal carcinoma cell growth by wild-type p53. Science. 1990;249:912–915. doi: 10.1126/science.2144057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braithwaite A, Nelson C, Skulimouski A, McGovern J, Pigott D, Jenkins J. Transactivation of the p53 oncogene by E1a gene products. Virology. 1990;177:595–605. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90525-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen C, Okayama H. High-efficiency transformation of mammalian cells by plasmid DNA. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:2745–2752. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.8.2745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cutt J R, Shenk T, Hearing P. Analysis of adenovirus early region 4-encoded polypeptides synthesized in productively infected cells. J Virol. 1987;61:543–552. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.2.543-552.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Debbas M, White E. Wild-type p53 mediates apoptosis by E1A, which is inhibited by E1B. Genes Dev. 1993;7:546–554. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.4.546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeGregori J, Kowalik T, Nevins J R. Cellular targets for activation by E2F1 transcription factor include DNA synthesis- and G1/S-regulatory genes. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:4215–4224. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.8.4215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dobner T, Horikoshi N, Rubenwolf S, Shenk T. Blockage by adenovirus E4orf6 of transcriptional activation by the p53 tumor suppressor. Science. 1996;272:1470–1473. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5267.1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Egan C, Jelsma T N, Howe J A, Bayley S T, Ferguson B, Branton P E. Mapping of cellular protein-binding sites on the products of early-region 1A of human adenovirus type 5. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:3955–3959. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.9.3955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Faha B, Harlow E, Lees E. The adenovirus-associated kinase consists of cyclin E-p33cdk2 and cyclin A-p33cdk2. J Virol. 1993;67:2456–2465. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.5.2456-2465.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giordano A, Whyte P, Harlow E, Franza B R, Jr, Beach D, Draetta G. A 60 kd cdc2-associated polypeptide complexes with the E1A proteins in adenovirus-infected cells. Cell. 1989;58:981–990. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90949-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giordano A, McCall C, Whyte P, Franza B R., Jr Human cyclin A and the retinoblastoma protein interact with similar but distinguishable sequences in the adenovirus E1A gene product. Oncogene. 1991;6:481–485. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gorman C M, Moffat L F, Howard B H. Recombinant genomes which express chloramphenicol acetyltransferase in mammalian cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1982;2:1044–1051. doi: 10.1128/mcb.2.9.1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Graham F L, van der Eb A J. A new technique for the assay of infectivity of human adenovirus 5 DNA. Virology. 1973;52:456–467. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(73)90341-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Graham F L, Smiley J, Russell W C, Nairn R. Characteristics of a human cell line transformed by human adenovirus type 5. J Gen Virol. 1977;36:59–72. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-36-1-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Halbert D N, Cutt J R, Shenk T. Adenovirus early region 4 encodes functions required for efficient DNA replication, late gene expression, and host cell shutoff. J Virol. 1985;56:250–257. doi: 10.1128/jvi.56.1.250-257.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Han J, Sabbatini P, Perez D, Rao L, Modha D, White E. The E1B 19K protein blocks apoptosis by interacting with and inhibiting the p53-inducible and death-promoting Bax protein. Genes Dev. 1996;10:461–477. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.4.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harvey D M, Levine A J. p53 alteration is a common event in the spontaneous immortalization of primary BALB/c murine embryo fibroblasts. Genes Dev. 1991;5:2375–2385. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.12b.2375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Horikoshi N, Usheva A, Chen J, Levine A J, Weinmann R, Shenk T. Two domains of p53 interact with the TATA-binding protein, and the adenovirus 13S E1A protein disrupts the association, relieving p53-mediated transcriptional repression. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:227–234. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.1.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Houweling A, van den Elsen P J, van der Eb A J. Partial transformation of primary rat cells by the leftmost 4.5% fragment of adenovirus 5 DNA. Virology. 1980;105:537–550. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(80)90054-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Howe J A, Mymryk J S, Egan C, Branton P E, Bayley S T. Retinoblastoma growth suppressor and a 300-kDa protein appear to regulate cellular DNA synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:5883–5887. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.15.5883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang M, Hearing P. The adenovirus early region 4 open reading frame 6/7 protein regulates the DNA binding activity of the cellular transcription factor, E2F, through a direct complex. Genes Dev. 1989;3:1699–1710. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.11.1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Javier R, Raska K, Jr, Macdonald G J, Shenk T. Human adenovirus type 9-induced rat mammary tumors. J Virol. 1991;65:3192–3202. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.6.3192-3202.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Javier R, Raska K, Jr, Shenk T. Requirement for the adenovirus type 9 E4 region in production of mammary tumors. Science. 1992;257:1267–1271. doi: 10.1126/science.1519063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Javier R, Shenk T. Mammary tumors induced by human adenovirus type 9: a role for the viral early region 4 gene. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1996;39:57–67. doi: 10.1007/BF01806078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Javier R T. Adenovirus type 9 E4 open reading frame 1 encodes a transforming protein required for the production of mammary tumors in rats. J Virol. 1994;68:3917–3924. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.6.3917-3924.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kawamura M, Yamashita T, Segawa K, Kaneuchi M, Shindoh M, Fujinaga K. The 273rd codon mutants of p53 show growth modulation activities not correlated with p53-specific transactivation activity. Oncogene. 1996;12:2361–2367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kowalik T F, DeGregori J, Schwarz J K, Nevins J R. E2F1 overexpression in quiescent fibroblasts leads to induction of cellular DNA synthesis and apoptosis. J Virol. 1995;69:2491–2500. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.4.2491-2500.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lavoie J N, Nguyen M, Marcellus R C, Branton P E, Shore G C. E4orf4, a novel adenovirus death factor that induces p53-independent apoptosis by a pathway that is not inhibited by zVAD-fmk. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:637–645. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.3.637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lin H J, Eviner V, Prendergast G C, White E. Activated H-ras rescues E1A-induced apoptosis and cooperates with E1A to overcome p53-dependent growth arrest. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:4536–4544. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.8.4536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lowe S W, Ruley H E. Stabilization of the p53 tumor suppressor is induced by adenovirus 5 E1A and accompanies apoptosis. Genes Dev. 1993;7:535–545. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.4.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lundblad J R, Kwok R P, Laurance M E, Harter M L, Goodman R H. Adenoviral E1A-associated protein p300 as a functional homologue of the transcriptional co-activator CBP. Nature. 1995;374:85–88. doi: 10.1038/374085a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marton M J, Baim S B, Ornelles D A, Shenk T. The adenovirus E4 17-kilodalton protein complexes with the cellular transcription factor E2F, altering its DNA-binding properties and stimulating E1A-independent accumulation of E2 mRNA. J Virol. 1990;64:2345–2359. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.5.2345-2359.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McGrory W J, Bautista D S, Graham F L. A simple technique for the rescue of early region I mutations into infectious human adenovirus type 5. Virology. 1988;163:614–617. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(88)90302-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moore M, Horikoshi N, Shenk T. Oncogenic potential of the adenovirus E4orf6 protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:11295–11301. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mymryk J S, Shire K, Bayley S T. Induction of apoptosis by adenovirus type 5 E1A in rat cells requires a proliferation block. Oncogene. 1994;9:1187–1193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mymryk J S. Tumour suppressive properties of the adenovirus 5 E1A oncogene. Oncogene. 1996;13:1581–1589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Neill S D, Hemstrom C, Virtanen A, Nevins J R. An adenovirus E4 gene product trans-activates E2 transcription and stimulates E2F binding through a direct association with E2F. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:2008–2012. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.5.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Neill S D, Nevins J R. Genetic analysis of the adenovirus E4 6/7 trans activator: interaction with E2F and induction of a stable DNA-protein complex are critical for activity. J Virol. 1991;65:5364–5373. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.10.5364-5373.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nevins J R. E2F: a link between the Rb tumor suppressor protein and viral oncoproteins. Science. 1992;258:424–429. doi: 10.1126/science.1411535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nishikawa T, Yamashita T, Yamada T, Kobayashi H, Ohkawara A, Fujinaga K. Tumorigenic transformation of primary rat embryonal fibroblasts by human papillomavirus type 8 E7 gene in collaboration with the activated H-ras gene. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1991;82:1340–1343. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1991.tb01802.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nudel U, Zakut R, Shani M, Neuman S, Levy Z, Yaffe D. The nucleotide sequence of rat cytoplasmic beta-actin gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 1983;11:1759–1771. doi: 10.1093/nar/11.6.1759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Obert S, O’Connor R J, Schmid S, Hearing P. The adenovirus E4-6/7 protein transactivates the E2 promoter by inducing dimerization of a heteromeric E2F complex. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:1333–1346. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.2.1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.O’Connor R J, Hearing P. The C-terminal 70 amino acids of the adenovirus E4-ORF6/7 protein are essential and sufficient for E2F complex formation. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:6579–6586. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.23.6579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rao L, Debbas M, Sabbatini P, Hockenbery D, Korsmeyer S, White E. The adenovirus E1A proteins induce apoptosis, which is inhibited by the E1B 19-kDa and Bcl-2 proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:7742–7746. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.16.7742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rawls J A, Pusztai R, Green M. Chemical synthesis of human papillomavirus type 16 E7 oncoprotein: autonomous protein domains for induction of cellular DNA synthesis and for trans activation. J Virol. 1990;64:6121–6129. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.12.6121-6129.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Raychaudhuri P, Bagchi S, Neill S D, Nevins J R. Activation of the E2F transcription factor in adenovirus-infected cells involves E1A-dependent stimulation of DNA-binding activity and induction of cooperative binding mediated by an E4 gene product. J Virol. 1990;64:2702–2710. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.6.2702-2710.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Reichel R, Neill S D, Kovesdi I, Simon M C, Raychaudhuri P, Nevins J R. The adenovirus E4 gene, in addition to the E1A gene, is important for trans-activation of E2 transcription and for E2F activation. J Virol. 1989;63:3643–3650. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.9.3643-3650.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ruley H E. Adenovirus early region 1A enables viral and cellular transforming genes to transform primary cells in culture. Nature. 1983;304:602–606. doi: 10.1038/304602a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shan B, Farmer A A, Lee W H. The molecular basis of E2F-1/DP-1-induced S-phase entry and apoptosis. Cell Growth Differ. 1996;7:689–697. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shen Y, Shenk T E. Viruses and apoptosis. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1995;5:105–111. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(95)90061-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shtrichman R, Kleinberger T. Adenovirus type 5 E4 open reading frame 4 protein induces apoptosis in transformed cells. J Virol. 1998;72:2975–2982. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.4.2975-2982.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Subramanian T, Tarodi B, Chinnadurai G. Functional similarity between adenovirus E1B-19kDa protein and proteins encoded by Bcl-2 proto-oncogene and Epstein-Barr virus BHRF1 gene. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1995;199:153–161. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-79496-4_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Takahashi M, Ilan Y, Chowdhury N R, Guida J, Horwitz M, Chowdhury J R. Long term correction of bilirubin-UDP-glucuronosyltransferase deficiency in Gunn rats by administration of a recombinant adenovirus during the neonatal period. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:26536–26542. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.43.26536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Teodoro J G, Shore G C, Branton P E. Adenovirus E1A proteins induce apoptosis by both p53-dependent and p53-independent mechanisms. Oncogene. 1995;11:467–474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.van den Elsen P, Houweling A, van der Eb A J. Expression of region E1b of human adenoviruses in the absence of region E1a is not sufficient for complete transformation. Virology. 1983;128:377–390. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(83)90264-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.van Ormondt H, Galibert F. Nucleotide sequences of adenovirus DNAs. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1984;110:73–142. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-46494-2_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Weiss R S, McArthur M J, Javier R T. Human adenovirus type 9 E4 open reading frame 1 encodes a cytoplasmic transforming protein capable of increasing the oncogenicity of CREF cells. J Virol. 1996;70:862–872. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.2.862-872.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Weiss R S, Lee S S, Prasad B V, Javier R T. Human adenovirus early region 4 open reading frame 1 genes encode growth-transforming proteins that may be distantly related to dUTP pyrophosphatase enzymes. J Virol. 1997;71:1857–1870. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.3.1857-1870.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Weiss R S, Gold M O, Vogel H, Javier R T. Mutant adenovirus type 9 E4 ORF1 genes define three protein regions required for transformation of CREF cells. J Virol. 1997;71:4385–4394. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.6.4385-4394.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.White E, Cipriani R. Role of adenovirus E1B proteins in transformation: altered organization of intermediate filaments in transformed cells that express the 19-kilodalton protein. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:120–130. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.1.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.White E, Cipriani R, Sabbatini P, Denton A. Adenovirus E1B 19-kilodalton protein overcomes the cytotoxicity of E1A proteins. J Virol. 1991;65:2968–2978. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.6.2968-2978.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.White E, Sabbatini P, Debbas M, Wold W S M, Kusher D I, Gooding L R. The 19-kilodalton adenovirus E1B transforming protein inhibits programmed cell death and prevents cytolysis by tumor necrosis factor alpha. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:2570–2580. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.6.2570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.White E. Regulation of p53-dependent apoptosis by E1A and E1B. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1995;199:34–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Whyte P, Buchkovich K J, Horowitz J M, Friend S H, Raybuck M, Weinberg R A, Harlow E. Association between an oncogene and an anti-oncogene: the adenovirus E1A proteins bind to the retinoblastoma gene product. Nature. 1988;334:124–129. doi: 10.1038/334124a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Whyte P, Ruley H E, Harlow E. Two regions of the adenovirus early region 1A proteins are required for transformation. Virology. 1988;62:257–265. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.1.257-265.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Whyte P, Williamson N M, Harlow E. Cellular targets for transformation by the adenovirus E1A proteins. Cell. 1989;56:67–75. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90984-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wigler M, Pellicer A, Silverstein S, Axel R, Urlaub G, Chasin L. DNA-mediated transfer of the adenine phosphoribosyltransferase locus into mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:1373–1376. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.3.1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wu X, Levine A J. p53 and E2F-1 cooperate to mediate apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:3602–3606. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.9.3602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yamashita T, Segawa K, Fujinaga Y, Nishikawa T, Fujinaga K. Biological and biochemical activity of E7 genes of the cutaneous human papillomavirus type 5 and 8. Oncogene. 1993;8:2433–2441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yamashita, T., H. Tonoki, D. Nakata, S. Yamano, K. Segawa, and T. Moriuchi. Adenovirus type 5 E1A immortalizes primary rat cells expressing wild-type p53. Microbiol. Immunol., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 77.Yew P R, Berk A J. Inhibition of p53 transactivation required for transformation by adenovirus early 1B protein. Nature. 1992;357:82–85. doi: 10.1038/357082a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yew P R, Liu X, Berk A J. Adenovirus E1B oncoprotein tethers a transcriptional repression domain to p53. Genes Dev. 1994;8:190–202. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.2.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zerler B, Moran B, Maruyama K, Moomaw J, Grodzicker T, Ruley H E. Adenovirus E1A coding sequences that enable ras and pmt oncogenes to transform cultured primary cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1986;6:887–899. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.3.887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zerler B, Roberts R J, Mathews M B, Moran E. Different functional domains of the adenovirus E1A gene are involved in regulation of host cell cycle products. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:821–829. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.2.821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]