Summary

The 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) agenda has committed to ‘ensuring that no one is left behind’. Applying the right to health of non-citizens and international migrants is challenging in today's highly polarized political discourse on migration governance and integration. We explore the role of a priority setting approach to help support better, fairer and more transparent policy making in migration health. A priority setting approach must also incorporate migration health for more efficient and fair allocation of scarce resources. Explicitly recognizing the trade-offs as part of strategic planning, would circumvent ad hoc decision-making during crises, not well-suited for fairness. Discussions surrounding decisions about expanding services to migrants or subgroups of migrants, which services and to whom should be transparent and fair. We conclude that a priority setting approach can help better inform policy making by being more closely aligned with the practical challenges policy makers face towards the progressive realization of migration health.

Keywords: Migration and health, Priority setting, Health policy, Fairness

Key messages.

-

•

Attaining Universal health Coverage and ensuring migrant groups are not left behind is challenging in today's highly polarized political discourse on migration governance and integration.

-

•

Established forums and decision-making processes must include those affected by decisions, including migrant voices.

-

•

For better, transparent policy making as well as more efficient and fair allocation of scarce resources, a priority setting approach should be applied for migration health.

-

•

Explicitly recognizing the trade-offs as part of strategic planning, would circumvent ad hoc decision-making during crises, not well-suited for fairness.

-

•

For the progressive realization of a priority setting approach a closer alignment with the practical challenges policy faced by policy makers is essential.

-

•

Empirical research to review health policies and understand how country-level priority setting processes incorporate migration health is needed.

-

•

Long-term trends in policy making must be monitored and analyzed to guide the continuous development of health and welfare systems at country level.

Introduction

Climate Change, covid-19 and conflict are global health challenges that have drawn attention to the health of people on the move. The views and preferences of policy makers on migration are diverse and governance is increasingly politicised.1,2 Migration is not only an independent determinant of health and health inequities, but health of migrants is heavily influenced by a range of interacting social, political and economic determinants.3,4 In the context of the Sustainable Development Goals, the right to health is captured in SDG 3.8 (Universal Health Coverage) within the broader promise to ‘Leave no one behind’.5 In reality, ensuring that no one is left behind and applying the right to health of non-citizens and international migrant categories, is challenging in today's highly polarised political discourse on migration governance and integration.2 In this health policy paper, we examine migration health through a priority setting lens, based on relevant literature. We illustrate the application of this approach with a case study at the country level (Norway). We highlight some of the priority setting dilemmas for migration health in Europe and explore how this approach can inform health policy in the European context. Ultimately, we aim to provide recommendations on priority setting in the context of migration and health to support better, fairer and more transparent policies for migrant groups.

The priority setting approach

In health care systems worldwide, there is a resource gap: in decisions and choices regarding health and health care, beneficial options for preventive services and treatment often exceed what the budget allows.6, 7, 8 Though more efficiency and higher budgets may increase the availability of resources, the overall budget or resources will always be limited relative to health needs.6 Priorities, prioritization and priority setting, though all related, are not synonymous for health care policies. Priorities indicate a ranking or hierarchical order sorted according to importance, urgency and usefulness. Prioritizing is the process of using resources to give best possible results. Priority setting is understood as a notional approach, includes principles and criteria to inform and promote legitimacy for decisions. Priority setting discussions have focused on questions such as which services should be provided to whom, and how much should they pay for them.7,9

Priority setting thus arises from the fundamental challenge of fairly allocating health resources. The reality is that prioritisation in health care is being made by decision makers, at different levels of the health system, all the time—either implicitly or explicitly. Hence, it is critical to acknowledge this reality and ensure that the decision-making process is, as far as possible, transparent, fair and legitimate. Explicit priority setting approaches is increasingly considered a valuable tool to support the delivery of the Universal Health Coverage agenda in an efficient and fair way, across high-income, middle-income, and low-income settings.6 From a migration health perspective, priority setting discussions are especially relevant for issues such as health promotion, disease prevention and treatment.

As illustrated by WHOs Universal Health Coverage Cube (Fig. 1), priority discussions relevant to migration health arise on three critical dimensions: 1) whom to cover (‘if and whether migrants or subgroups of migrants should have access?’), 2) to which services (‘should migrants have access to all or some types of diagnostics and treatment?’), and 3) at what cost (‘if and how much should migrants pay for such services?’).10,11

Fig. 1.

Three dimensions of Universal Health Coverage.

Source: WHO 2010.

The priority setting approach also put emphasis on public participation, accountability and fair decision-making processes. People should not only be recipients of services, but also agents actively shaping the health system and decision making.7 This is relevant for migration health, as migrant voices may not be included in such processes.4 Box 1 provides a country case study on migration health policies and the priority setting process in practice, using the example of Norway.

Box 1. Case study priority setting and migration and health policies in Norway.

Despite high standards of living and amongst the highest per capita health care expenditure in the world, Norway has some significant and growing social and economic inequities as indicated in the 2023 Marmot Report.12 Health policies governing health and care services are explicit about equity, which is reflected in legislation, strategies and action plans. There is broad political support for reducing social inequalities in health.13 In line with the values of the Norwegian welfare state, the Government has launched several national health strategies and measures over recent years with the aim of reducing social inequalities in health. However, despite the existing evidence and a long tradition of reducing these inequities through welfare policies and structural measures, the implementation of policies has been slow and inequities in health are widening, in particular for disadvantaged groups.12

While the first half of the 20th century saw net emigration from Norway, in the last 50 years the proportion of migrants has risen from 1% (1970) to over 18.5% (2021). The migration flows over this period have been fragmented, reflecting global events. Over the last decade, most immigrants have migrated from eastern European countries, except for 2015 when Syrians were the largest group. It is, therefore, not a surprise that migrants are a heterogenous group as they originate from 221 countries. Norway has not been a first choice as a destination country and reasons for migration vary (39% family reunification, 31% labour, 22% refugees and 6% education). Despite a growing, solid body of evidence on the health needs of migrants, in relation to the increasing numbers of migrants, migrant health has not been a policy priority in Norway. A review of migrant health policies in Norway revealed a fragmentation and lack of coordination between the situation analysis of the health challenges and the proposed measures. Action remains inadequate; where policies exist, evidence on the effectiveness of policy implementation is almost absent. A review of migration health policies in Norway revealed a fragmentation and lack of coordination between the situation analysis of the health challenges and the proposed measures. Action remains inadequate; where policies exist evidence on the effectiveness of policy implementation is almost absent.14

Building on Lorant and Bhopal's work applying Margaret Whitehead's framework to compare policies tackling ethnic inequities in health in Belgium and Scotland,15 an analysis in Norway found that policies and measures are ad hoc, small scale and have not been mainstreamed.14 For example, while there is adequate evidence, recognition and acknowledgement of mental health of migrants as a public health challenge, migrant health has not been adequately mainstreamed into any mental health or national health initiatives. Lack of progression may be attributed to denial, indifference, but the reasons remain unclear. By contrast, female genital mutilation has received policy priority across different welfare policies, including health and violence. Despite limited evidence on the magnitude of the issue, strong political will for action led to the development, follow-up and implementation of comprehensive and coordinated policies, supported by legislation, action plans and budgets.

In 2007, Norway established a unique initiative to institutionalise fair and transparent priority setting in the Norwegian health system through establishing the National Council on Quality and Prioritization in the Health and Care Services. This systematic approach, building on previous work, was visible, brought leaders and decision makers from across the health sector–including users and patient organizations - to undertake priority setting as a collegium and collectively inform health care polices in Norway. During its first 10 years the Council twice prioritized migrant health policies. On the first occasion, in 2011, a decision was made that data on public health and health determinants should include immigrant group, and that such data must be aggregated on a regular basis. Data should have been available from the January 2012, however, over a decade later the implementation has been piecemeal. On the second occasion, in 2015, there was a discussion in the Council regarding Health Screening for Refugees & Asylum Seekers in response to the influx of Syrian refugees. As evidence to fulfil criteria for screening and/or priority was deemed inadequate it was agreed that the evidence base should be strengthened. Again, there has been little change and data limitations have been raised recently in relation to the current Ukraine Crisis.

On a policy level, the Norwegian Government launched the Immigrant Health Policy in 2011 (2013–2017) to much acclaim in Norway and abroad. There are very few examples of such policies, especially in Europe. However, this was short-lived. After a change of government in 2013, the strategy was not followed up with an action plan, nor adequate resources to implement this policy. No new strategy was developed after it expired in 2017. This highlights the politicisation of migration health in the Norwegian context.

One of the key instruments to mapping migrants’ access to health care has been international assessments such as the Migration Integration Policy Index (MIPEX) in Europe (2015) (expanded globally in 2020).16 MIPEX are important metrics studying the integration of migrants and the other sectors, such as education, that the health priority setting agenda links to. Notwithstanding methodological constraints, it is noteworthy that Norway held a high score at rank #2 (MIPEX 2015). Norway, like most countries in Europe, has not yet participated in the Migration Governance Index (MGI) exercise. Migrant Health in Norway has also been mapped by the EU project Joint Action Health Equity (JAHEE 2019).17 While a discussion of the role and impact of MIPEX, and JAHEE are beyond the scope of this paper, such exercises are important for awareness on migration health is among Norwegian health policy makers. Though, policies and strategies may have stalled, there is growing body of research and some of the evidence is being put into practice, especially at the local level. The Pandemic Declaration (2022) clearly indicates progress in research there is a need for strategies, resources and user involvement.18

Migration health and priority setting dilemmas in Europe

Migration is political. Policy debates taking centre stage in public debates, parliamentary sessions and mainstream media focus on issues such as immigration and border control, measures deterring irregular migrants through land and sea routes, rising ultra-nationalism, and ‘othering’ and anti-immigrant rhetoric.1,4 Health is not usually addressed in these fora. When debated at all, issues include the (supposed) overutilization of healthcare services or (unfounded) claims that asylum seekers have better access to healthcare services compared to the local populations. Understanding the positive impacts of migration, such as community development, the economic contribution migrants make in sectors, such as health care and essential services,4 and dispelling the migrant myths are seldom taken into consideration in public debates, nor in priority setting discussions. At the country level, health policies have not been mainstreamed within the migration governance agenda. Furthermore, migration health has rarely been included in health priority setting, as outlined in the Norwegian case study in Box 1. While equity in all policies implicitly includes migrants, migrants or subgroups of migrants are seldom explicitly included.

The European region has seen an increasing numbers of migrants. In 2020, 87 million international migrants accounting for 31% of the world's international migrants, lived in Europe, of which 44 million were born in Europe and living elsewhere in the region.19 Within Europe, there is large variation in both typology of migrants and reasons for migration. There is large intra-European migration for work-related reasons and greater economic opportunities; some countries in the region have seen waves of migrants due to war and conflicts in neighbouring countries, thus policy making at a country level is contingent upon a wide range of factors. On a global scale, climate change, recognized as a driver for migration, will oblige people to leave their habitual homes, either temporarily or permanently, within their country or abroad.4 Though numbers are uncertain, there is little doubt that this will result in an increase of the number of people on the move reaching Europe (Boxes 2 and 3).

Box 2. Tools to facilitate migration health policies—migration governance index.

Tools to facilitate Migration Health policies such as MIPEX (referred to earlier) could enable countries to make progress. The MGI (Migration Governance Indicators) initiative is a tool created by the International Organisation for Migration (IOM) and developed with Economist Impact to help governments in assessing the comprehensiveness of their migration governance structures through 94 questions divided into six domains.33 Since 2016, MGI assessments have been rolled out in 92 countries and 51 local jurisdictions, and they have also informed the development of migration policies and capacity-building activities in many of those territories. In Europe, the roll out has been slow—only one fifth of countries (10/52) have used MGI.33

Box 3. Recommendations to promote fairness in priority setting on migration health in European countries.

-

✔

Population subgroups, such as migrants or subgroups of migrants, must be included in efforts to achieve universal health coverage at country level.

-

✔

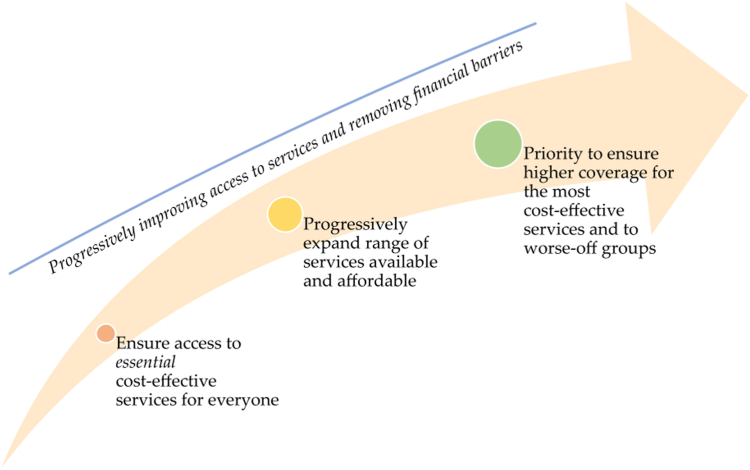

Countries can progressively realise migration health (Fig. 2). A priority setting approach can help advance the global agendas, initiatives and actions on Migration and Health into regional and country level policies.

-

✔

Established forums and decision-making processes must include those affected by decisions, including migrant voices.

-

✔

Policy making through a ‘Health in all policies’ approach must include inter-ministerial and intersectoral collaboration to identify and act on the broader determinants of health.

-

✔

Tools such as Migration Governance Indicators need to be used and rolled out to inform priority setting processes. This must be supplemented by improved data collection and use of existing data.

-

✔

Empirical research to review health policies and understand how country-level priority setting processes incorporate migration health is needed.

-

✔

Analysis on long-term trends in migration health to supplement MGI/MIPEX analysis should be taken forward as health and welfare systems are developed at the regional and country level.

Europe has for long been a region affected by and contributing to migration. Health care service provision is largely tax based, or insurance based in Europe and as such not designed to include and extend services to cater to rapid movements of people from Ukraine to Poland or Moldova, from Afghanistan and Syria to Turkey, and from northern Africa to Greece or Italy, to name a few. Though the initial humanitarian health response has been largely driven by NGOs, international organisations with engagement from formal health systems being minimal, ultimately health services will have to meet the needs of these groups.

The covid-19 pandemic demonstrated how already existing restrictions in access to health services for migrants also restricted access to Covid-19 interventions. International migrants are also care workers, essential workers, and health workers and were critical to health systems in EU. Hargraves et al. (2020) highlighted early in the pandemic that these restrictions could harm the overall covid-19 response.20 Crawshaw et as examined the covid-19 vaccine roll-out in Europe and showed how migration specific barriers were associated with vaccine uptake and under vaccination.21 Migration health policies in Europe so far have only addressed downstream issues and will benefit from a priority setting discussion, illustrated by recent examples such as pandemic preparedness and fair financing of health services. For example, continuing to build trust in public health systems, including amongst migrants, will be central to pandemic preparedness. Pooling finances and, where necessary, personnel, within the European Union region could also help to supporting public health systems, meet health needs, and maintain public and political support. Excluding migrants and not paying adequate attention to migration health policies will jeopardize the attainment of UHC and the WHO triple billion targets.22

Is the priority setting approach relevant for migration health?

The priority setting approach has several methodological strengths. It explicitly acknowledges that there are insufficient resources for all potential interventions and provides a framework to assist in identifying and prioritising different alternatives. This transparency allows relevant ‘trade-offs’ to be identified. Priority setting analysis can thereby help policy makers navigate ‘real-world’ problems and identify the best options or outcomes in a non-ideal situation. The systematic approach of priority setting at country level can help shift policy making from a ‘crisis management’ mindset to a ‘long term strategic planning’ approach, combining top-down and bottom-up approaches. This is relevant for migration health, where national or local efforts happen both as responses to work-related migration, as well as unpredictable (but not wholly unexpected) movements of people between, or within, countries.

While the priority setting literature has been useful for policy makers in low-, middle- and high-income countries—including the fair financing of UHC packages of essential health services—it has some shortcomings relevant for the migration health perspective.7,23,24 Firstly, priority setting frameworks works best with well-defined and delineated populations, budgets and some level of agreement on relevant criteria for priority setting processes. Migrant populations–encompassing refugees, asylum seekers, trafficked persons, undocumented migrants, families seeking reunification, international students, temporary or long-term labour migrants–may be at the margins of what can be understood as “well-defined” populations. The different sub-groups may have different legal and ‘real-life’ access to health and other welfare services.

Secondly, the priority setting approach typically focuses on health care services.7,9 The existing priority setting frameworks have to a lesser extent identified and compared investments in health promotion and disease prevention which are central to migration health. Thirdly, while priority setting places emphasis on reducing health inequities through a fair distribution of resources, it does not generally address the social determinants of health. This is a general limitation relevant from a migration health policy perspective, given the important role of social, legal and other health determinants outside of the heath sector in shaping migration health.25

Fourthly, in practice, priority setting frameworks towards achieving UHC are enacted in a political context which may overlook migrants. Many countries have explicitly stated before international human rights bodies that they cannot, or do not wish to, ensure health protection, including the provision of essential health services to certain categories international migrants, and especially to irregular migrants—priority setting makes these decisions explicit.26 These shortcomings primarily relate to the implementation of priority setting, rather than fundamental flaws in the approach. We contend that priority setting—both in theory and in practice—could be improved through greater engagement from migration health scholars and practitioners.

The progressive realisation of migration health policy and the health of migrants

The WHO framework Making Fair Choices Towards Universal Health Coverage, provides guidance on how countries should set priorities at the population level.7 To promote fairness, it is recommended that priority is given to interventions that maximise health benefits, help the worse-off and provide financial risk protection. Striking a fair balance between these principles can be challenging but expanding access to essential services to all should be considered a priority (Fig. 1). The case study from Norway (Box 1) illustrates that a priority setting approach cannot be taken without the requisite political will or engagement of policy makers. Evidence-informed decision making on migration and health is inherently political; better data do not necessarily lead to better outcomes.27 In reality, the most rigorous evidence can be disregarded by populist politicians who seek to appease the anxieties and prejudices of select constituencies.

Most countries are far from realising Universal Health Coverage, for the general population as well as migrants or sub-groups of migrants. This contrasts the international commitments on migration and UHC to ‘leave no one behind’.28, 29, 30 Building on the WHO ‘Making Fair Choices Towards Universal Health Coverage’ we suggest the pursuit of a ‘progressive realization of migration health’. It can be seen as a continuum between the status quo in a country, towards a fully integrated, tailored service responding to migrants' health needs (Fig. 2). First, ensuring expanding access to essential cost-effective services to the whole population; second, progressively expanding the range of services accessible and affordable for migrants and subgroups of migrants, ensuring low levels of co-payment to avoid financial hardship; and third, setting priorities to maximise coverage of the most cost-effective services with special attention to the needs of the worst-off, before coverage is expanded for less effective services.

Fig. 2.

The progressive realisation of migration health.

The potential contribution of priority setting to migration health policy

International and regional human rights instruments such as the European Social Charter and the Charter of Fundamental Rights address health as a fundamental human right regardless of migration status; governments are obliged to uphold this right in the interest of good public health governance.4,16 The EU has since issued a number of legally binding directives that impinge on migrant health: the racial equality directive, the long-term residents directive and the directive laying down minimum standards for the reception of asylum seekers, to name a few, and the European Commission supports several migration health projects.4,31 While the recognition and acknowledgement of these fundamental principles are commendable, they do not necessarily translate into policy or implementation of policy at the National level. At the end of 2017, no Ministries of Health of EU Member States had an ongoing health strategy or action plan to target migrants and people of migrant descent.16,31 Member States with National Health Strategies in place hardly make any reference to migrant health and accessibility of healthcare for migrants.16,31

The pandemic exposed pre-existing cracks and gaps in migrant health policy, it has not yet brought together the fragmented European migrant health policy landscape.18 The war in Ukraine has brought Europe into, yet again, crisis mode for migration and health.32 This surge in academic and policy interest has not translated into binding treaties or implementation efforts at regional level or within countries, resulting in a gaping void among lofty goals, national policies, and practices locally. Globally, a range of governance agendas on the domains of migration and health have developed in recent years, providing important opportunities for garnering political support for intervention.28, 29, 30 These agendas bridge the fields of migration governance, development and global health governance, and include: the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration; the Global Compact on Refugees; the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs); UHC; World Health Assembly processes; disease prevention and control programmes (including for malaria, HIV and TB); and the Global Health Security Agenda.

Priority setting requires strategic leadership and investment to build alliances between migration management systems and the health sector within the country across sectors and levels of governance. Target 3.8 of the SDGs calls for universal health coverage (UHC), providing a strategic opportunity to improve responses to migration and health. Yet, as discussed herein, certain migrant groups remain unaccounted or missed in discussions at the country level [1, 2].

A priority setting approach can help think through the practical challenges policy makers face, and explicitly address the trade-offs at stake. Ensuring effective knowledge-to-policy translation must not only focus on rigorous data but also harness this evidence to inform health diplomacy, strategic media communication, ethics, and understanding ‘the other’. Research suggests that for public perceptions of migration to change, the narrative must change and this cannot be done without political will or the media.4 To drive the political will necessary to promote migrant-sensitive policies, a coordinated strategy for media and community engagement is a must. Data can be impactful when linked to specific issues of direct concern to the public and framed within a clear narrative.

Migration health approaches and policies have been in the crisis mode because of manmade or natural disasters. Effective long-term policy requires a paradigm shift from ‘firefighting’ and being ‘reactive’. Besides emergencies, migration health policies have been largely driven by the political agenda and the economic arguments. In addition, the policy debates often ignore the migrant integration–migration health nexus. Given the competition for shrinking resources and the commonplace perception of migrants being a burden to the health system, all health policies should include migration health. ‘Mainstreaming’ migration health, reiterated by Joint Action Health Equity Europe as a key recommendation, suggests moving away from a target-group, target disease, siloed approach. This should be a bottom up, needs-based, rather than group-based, approach would consider migrants' specific needs and avoid treating migrants as a uniform group.17 This would be in line with other efforts to achieve universal health coverage, but in an approach that includes migrants. Thus, there is a need for both, mainstreaming migration health i.e. health policies in general must be ‘diversity sensitive’ as well as targeting where needs of migrants are unmet by the mainstream approaches.

Priority setting frameworks, such as WHOs framework Making Fair Choices Towards Universal Health Coverage, can provide guidance on essential services that must be expanded, including to migrants or subgroups of migrants.7,10 This is especially relevant at the country level, where limited resources underpin the political (though often scapegoated) challenge of providing health for all.

Ultimately, this exercise should be done based on local and national contexts. Specific targeting of migrants or subgroups of migrants is relevant from the perspective of inclusiveness and equitable access to services but can also contribute to stigma or discrimination. Promoting migrant sensitive health services and/or explicit targeting of migrants or subgroups of migrants should be carefully considered with emphasis on the local context.21 A finding emerging from the analysis of the sub-national dataset of Migration Governance Index is the fact that local administrative jurisdiction, such as towns and municipalities, have more inclusive health integration policies than federal authorities. It is critical for those engaged in priority setting exercises (usually undertaken at federal level) to ensure meaningful engagement of sub-national structures critical for enabling migrant integration at the local level.33 Further research on priority setting for migration health ais now vital for long term strategic planning in migration and health which is efficient and fair.34

Conclusion

Migration health policies and migration governance are shaped by the political context and an array of non-health factors; actions on the social and political determinants of health are, therefore, critical for improving migration health.2 There is a role for expanding a priority setting approach, already widely used in Europe, to incorporate migration health in the future and aide a more efficient and fair allocation of scarce resources (Fig. 2). Ad hoc decision making on migration health during crises is not well-suited for fair decision making. More transparent discussions surrounding decisions about expanding services to migrants or subgroups of migrants, which services and to whom, acknowledging the challenging decisions faced by policy makers. Ultimately, more explicitly recognising the trade-offs at stake can better inform policy making towards the progressive realisation of migration health.

Search strategy and selection criteria.

The references for this review were collected from searches of PubMed, Scopus and UN databases with the search ‘priority setting’, ‘migration health’, ‘policy’ and ‘Europe’ from 2013 to 2023. Relevant articles and reports were also identified through consultation with WHO focal points in the WHO Euro Region and the authors' own files to capture the breadth of migration and health research published in the grey literature. Reference lists of key peer-reviewed studies such as the UCL–Lancet Commission on Migration and Health, the MIPEX report and the WHO Report on the health of refugees and migrants in the WHO European Region were also consulted. Only papers published in English were reviewed, except for the Norway case study for which policy documents were reviewed in Norwegian. The finalized reference list was compiled according to originality and relevance to the broad scope of the review. As far as possible we have replaced book chapters with articles by the same authors.

Contributors

Bernadette N Kumar (BNK) and Kristine Husøy Onarheim (KHO) had the idea for the paper's theme, design and structure. BNK and Karl Blanchet (KB) discussed the theme, outline and its relevance to the series. BNK and KHO developed the draft. Anand Singh Bhopal (ASB) and Kolitha Wickramage (KW) commented on the draft.

BNK, ASB, KB, KW and KHO all participated in contributing and the revision of the draft and agreed to the proposed recommendations and the final version.

Declaration of interests

The authors have no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Maria Cristina Profili, Senior Regional Migration Health Advisor, International Organization for Migration (IOM), Regional Office for the European Economic Area, the European Union and NATO, for inputs to the concept of the publication. We thank Dr Sneha Ojha for technical support. We thank three anonymous reviewers for constructive feedback in the review.

References

- 1.Wickramage K., Annunziata G. Advancing health in migration governance, and migration in health governance. Lancet. 2018;392(10164):2528–2530. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32855-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ingleby D. Moving upstream: changing policy scripts on migrant and ethnic minority health. Health Policy. 2019;123(9):809–817. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2019.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Castañeda H., Holmes S.M., Madrigal D.S., Young M.E.D., Beyeler N., Quesada J. Immigration as a social determinant of health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2015;36:375–392. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abubakar I., Aldridge R.W., Devakumar D., et al. The UCL–lancet commission on migration and health: the health of a world on the move. Lancet. 2018;392(10164):2606–2654. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32114-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.United Nations . A Shared UN System framework for Action; 2017. Leaving No one behind: equality and non-discrimination at the heart of sustainable development.https://www.unsceb.org/CEBPublicFiles/CEB%20equality%20framework-A4-web-rev3.pdf Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 6.Norheim O.F. Ethical priority setting for universal health coverage: challenges in deciding upon fair distribution of health services. BMC Med. 2016;14(1):75. doi: 10.1186/s12916-016-0624-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; 2014. Making fair choices on the path to universal health coverage: final report of the WHO consultative group on equity and universal health coverage. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daniels N., Sabin J.E. Accountability for reasonableness: an update. BMJ. 2008;337:a1850. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jamison D.T., Gelband H., Horton S., et al. 3rd ed. 2017. Disease control priorities: improving health and reducing poverty. Washington (DC) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Onarheim K.H., Melberg A., Meier B.M., Miljeteig I. Towards universal health coverage: including undocumented migrants. BMJ Glob Health. 2018;3(5) doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001031. https://gh.bmj.com/content/3/5/e001031 Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Onarheim K.H., Wickramage K., Ingleby D., Subramani S., Miljeteig I. Adopting an ethical approach to migration health policy, practice and research. BMJ Glob Health. 2021;6(7) doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-006425. https://gh.bmj.com/content/6/7/e006425 Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Institute of Health Equity Rapid review of inequalities in health and wellbeing in Norway since 2014. https://www.instituteofhealthequity.org/resources-reports/rapid-review-of-inequalities-in-health-and-wellbeing-in-norway-since-2014 [cited 2023 Jul 27]; Available from:

- 13.Arntzen A., Bøe T., Dahl E., et al. 29 recommendations to combat social inequalities in health. The Norwegian Council on Social Inequalities in Health. Scand J Public Health. 2019;47(6):598–605. doi: 10.1177/1403494819851364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spilker R.S. 2012. Public health challenges among immigrants in norway a content analysis of health policy documents.https://www.duo.uio.no/bitstream/handle/10852/30290/Binder-Spilker.pdf?sequence=5 Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whitehead M. A typology of actions to tackle social inequalities in health. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007;61(6):473–478. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.037242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ingleby D., Petrova-Benedict R., Huddleston T., Sanchez E. The MIPEX Health strand Consortium. The MIPEX health strand: a longitudinal, mixed-methods survey of policies on migration health in 38 countries. Eur J Public Health. 2019;29(3):458–462. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cky233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bucciardini R., Zetterquist P., Rotko T., et al. Addressing health inequalities in Europe: key messages from the Joint Action Health Equity Europe (JAHEE) Arch Publ Health. 2023;81(1):89. doi: 10.1186/s13690-023-01086-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kumar B.N., Eikemo T.A., Diaz E. Migration and Health: time for a new research agenda. Scand J Public Health. 2023;51(3):309–311. doi: 10.1177/14034948231172320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization . World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe; Copenhagen: 2020. Regional Office for Europe. Collection and integration of data on refugee and migrant health in the WHO European Region: technical guidance.https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/337694 [cited 2023 Sep 18]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hargreaves S., Kumar B.N., McKee M., Jones L., Veizis A. Europe's migrant containment policies threaten the response to covid-19. BMJ. 2020;368:m1213. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crawshaw A.F., Farah Y., Deal A., et al. Defining the determinants of vaccine uptake and under vaccination in migrant populations in Europe to improve routine and COVID-19 vaccine uptake: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22(9):e254–e266. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00066-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Triple billion dashboard - WHO. https://www.who.int/data/triple-billion-dashboard [cited 2023 Jul 27]. Available from:

- 23.Kapiriri L., Norheim O.F., Martin D.K. Priority setting at the micro-, meso- and macro-levels in Canada, Norway and Uganda. Health Policy. 2007;82(1):78–94. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Watkins D.A., Jamison D.T., Mills A., et al. In: Disease control priorities: improving health and reducing poverty. 3rd ed. Jamison D.T., Gelband H., Horton S., et al., editors. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank; Washington (DC): 2017. Universal health coverage and essential packages of care.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK525285/ [cited 2023 Jul 27]. Available from: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Juárez S.P., Honkaniemi H., Dunlavy A.C., et al. Effects of non-health-targeted policies on migrant health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7(4):e420–e435. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30560-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.International Organization for Migration (IOM) 2013. International migration, health and human rights.https://publications.iom.int/books/international-migration-health-and-human-rights [cited 2023 Jul 27]; Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crisp J., Refugees The ‘Better Data’ panacea for refugees and Migrants: a reality check. 2018. https://deeply.thenewhumanitarian.org/refugees/community/2018/03/12/the-better-data-panacea-for-refugees-and-migrants-a-reality-check.htm [cited 2023 Jul 28]; Available from:

- 28.United Nations. UNHCR Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees Part II - Global compact on refugees. 2018. https://www.unhcr.org/media/report-united-nations-high-commissioner-refugees-part-ii-global-compact-refugees [cited 2023 Jul 28]; Available from:

- 29.United Nations . Marrakech, Morocco, 10 and 11 December 2018. Item 10 of the provisional agenda. United Nations; 2018. Intergovernmental conference to adopt the global compact for safe, orderly and regular migration.https://www.un.org/en/conf/migration/ [cited 2023 Jul 28]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 30.World Health Organization . 2019. Promoting the health of refugees and migrants: global action plan, 2019–2023.https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/WHA72-2019-REC-1 [cited 2023 Jul 28]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 31.World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe . World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe; Copenhagen: 2018. Report on the health of refugees and migrants in the WHO European Region: No public health without refugee and migrant health.https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/311347 [cited 2023 Sep 18]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ioffe Y., Abubakar I., Issa R., Spiegel P., Kumar B.N. Meeting the health challenges of displaced populations from Ukraine. Lancet. 2022;399(10331):1206–1208. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00477-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.International Organization for Migration (IOM) 2022. Migration governance Indicators data and the global Compact for Safe, orderly and regular migration: a baseline report.https://publications.iom.int/books/migration-governance-indicators-data-and-global-compact-safe-orderly-and-regular-migration Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baltussen Rob, Mwalim Omar, Blanchet Karl, et al. Decision-making processes for essential packages of health services: experience from six countries. BMJ Glob Health. 2023;8(Suppl 1) doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2022-010704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]