Abstract

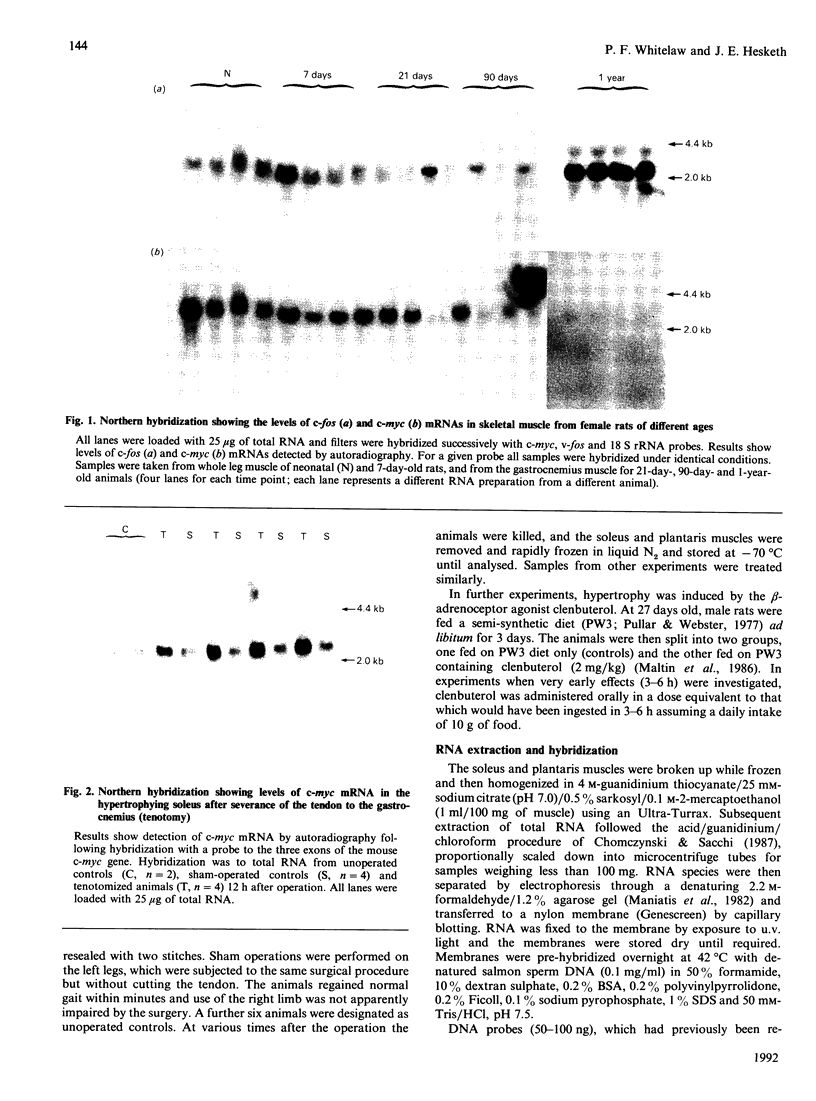

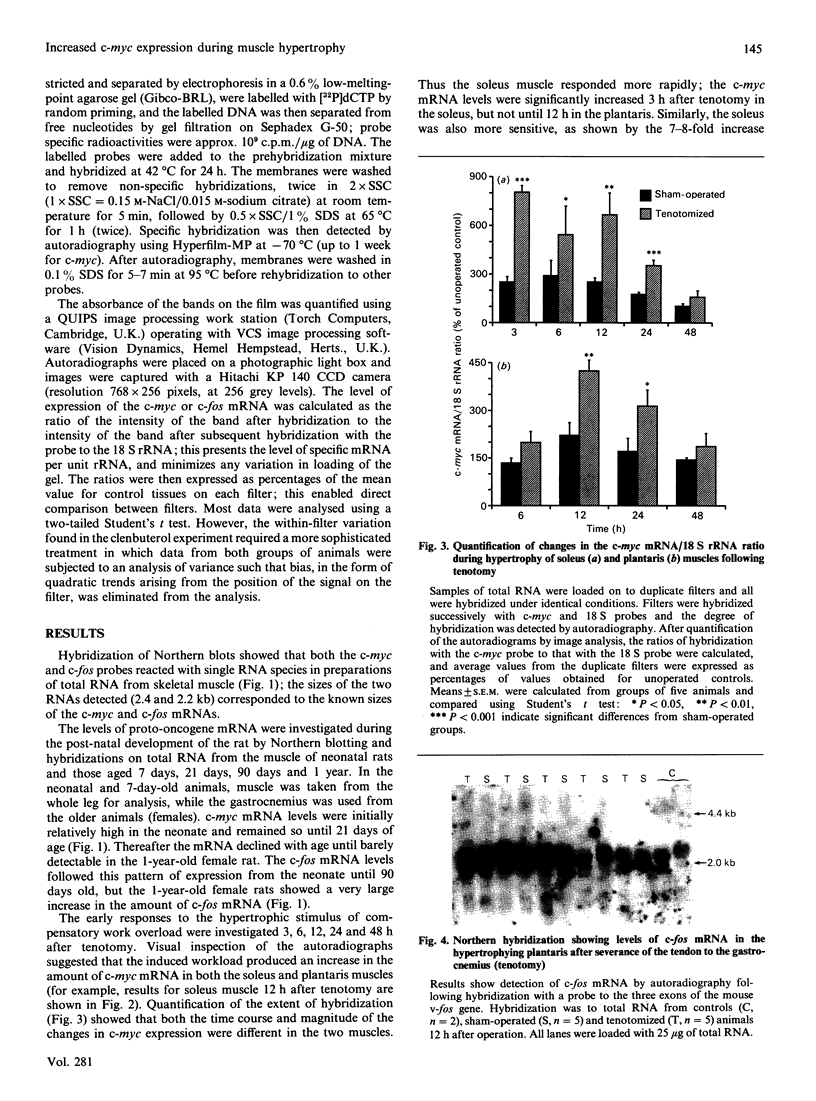

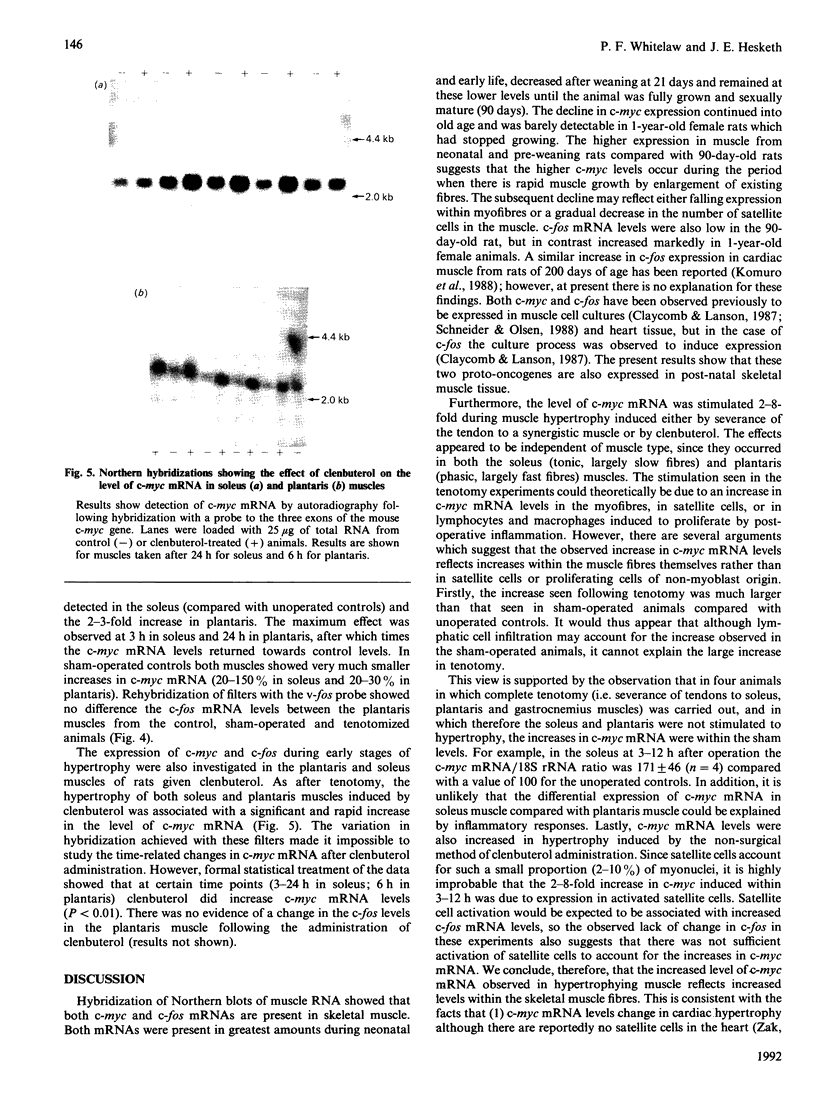

The levels of c-myc and c-fos mRNA were investigated in rat skeletal muscle by Northern hybridization. During post-natal development in the rat, c-myc mRNA levels were similar at birth and at 7 and 21 days of age, but then declined at 90 days and were barely detectable at 1 year. c-fos mRNA levels followed this pattern of expression until 90 days, but showed a large increase at 1 year. Hypertrophy of soleus and plantaris muscles was induced either by severance of the tendon to the synergistic gastrocnemius (tenotomy) or by administration of the beta-adrenoceptor agonist clenbuterol. In both cases hypertrophy was associated with a rapid increase in c-myc mRNA levels. Following tenotomy the increase was both greater (8-fold) and more rapid (3 h) in soleus than in plantaris (2-3 fold, 12 h). Similar effects were observed during clenbuterol administration. Neither treatment caused any alteration in c-fos mRNA levels in the plantaris muscle. The results show that increased c-myc mRNA levels are an early event in the response of skeletal muscle to hypertrophic stimuli; it is argued that this occurs within the differentiated skeletal muscle fibres.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Alemá S., Tató F. Interaction of retroviral oncogenes with the differentiation program of myogenic cells. Adv Cancer Res. 1987;49:1–28. doi: 10.1016/s0065-230x(08)60792-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campisi J., Gray H. E., Pardee A. B., Dean M., Sonenshein G. E. Cell-cycle control of c-myc but not c-ras expression is lost following chemical transformation. Cell. 1984 Feb;36(2):241–247. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90217-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chomczynski P., Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987 Apr;162(1):156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claycomb W. C., Lanson N. A., Jr Proto-oncogene expression in proliferating and differentiating cardiac and skeletal muscle. Biochem J. 1987 Nov 1;247(3):701–706. doi: 10.1042/bj2470701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran T., Peters G., Van Beveren C., Teich N. M., Verma I. M. FBJ murine osteosarcoma virus: identification and molecular cloning of biologically active proviral DNA. J Virol. 1982 Nov;44(2):674–682. doi: 10.1128/jvi.44.2.674-682.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVol D. L., Rotwein P., Sadow J. L., Novakofski J., Bechtel P. J. Activation of insulin-like growth factor gene expression during work-induced skeletal muscle growth. Am J Physiol. 1990 Jul;259(1 Pt 1):E89–E95. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1990.259.1.E89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo T., Nadal-Ginard B. Transcriptional and posttranscriptional control of c-myc during myogenesis: its mRNA remains inducible in differentiated cells and does not suppress the differentiated phenotype. Mol Cell Biol. 1986 May;6(5):1412–1421. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.5.1412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson J. M., Rushford C. L., Dorney D. J., Wilson G. N., Schmickel R. D. Structure and variation of human ribosomal DNA: molecular analysis of cloned fragments. Gene. 1981 Dec;16(1-3):1–9. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(81)90055-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freytag S. O. Enforced expression of the c-myc oncogene inhibits cell differentiation by precluding entry into a distinct predifferentiation state in G0/G1. Mol Cell Biol. 1988 Apr;8(4):1614–1624. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.4.1614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izumo S., Nadal-Ginard B., Mahdavi V. Protooncogene induction and reprogramming of cardiac gene expression produced by pressure overload. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988 Jan;85(2):339–343. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.2.339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson T., Allard M. F., Sreenan C. M., Doss L. K., Bishop S. P., Swain J. L. The c-myc proto-oncogene regulates cardiac development in transgenic mice. Mol Cell Biol. 1990 Jul;10(7):3709–3716. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.7.3709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komuro I., Kurabayashi M., Takaku F., Yazaki Y. Expression of cellular oncogenes in the myocardium during the developmental stage and pressure-overloaded hypertrophy of the rat heart. Circ Res. 1988 Jun;62(6):1075–1079. doi: 10.1161/01.res.62.6.1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau L. F., Nathans D. Identification of a set of genes expressed during the G0/G1 transition of cultured mouse cells. EMBO J. 1985 Dec 1;4(12):3145–3151. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb04057.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence J. B., Taneja K., Singer R. H. Temporal resolution and sequential expression of muscle-specific genes revealed by in situ hybridization. Dev Biol. 1989 May;133(1):235–246. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(89)90314-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maltin C. A., Delday M. I., Reeds P. J. The effect of a growth promoting drug, clenbuterol, on fibre frequency and area in hind limb muscles from young male rats. Biosci Rep. 1986 Mar;6(3):293–299. doi: 10.1007/BF01115158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan M. J., Loughna P. T. Work overload induced changes in fast and slow skeletal muscle myosin heavy chain gene expression. FEBS Lett. 1989 Sep 25;255(2):427–430. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)81138-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulvagh S. L., Michael L. H., Perryman M. B., Roberts R., Schneider M. D. A hemodynamic load in vivo induces cardiac expression of the cellular oncogene, c-myc. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1987 Sep 15;147(2):627–636. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(87)90977-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murre C., McCaw P. S., Baltimore D. A new DNA binding and dimerization motif in immunoglobulin enhancer binding, daughterless, MyoD, and myc proteins. Cell. 1989 Mar 10;56(5):777–783. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90682-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadal-Ginard B. Commitment, fusion and biochemical differentiation of a myogenic cell line in the absence of DNA synthesis. Cell. 1978 Nov;15(3):855–864. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(78)90270-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Periasamy M., Gregory P., Martin B. J., Stirewalt W. S. Regulation of myosin heavy-chain gene expression during skeletal-muscle hypertrophy. Biochem J. 1989 Feb 1;257(3):691–698. doi: 10.1042/bj2570691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pullar J. D., Webster A. J. The energy cost of fat and protein deposition in the rat. Br J Nutr. 1977 May;37(3):355–363. doi: 10.1079/bjn19770039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider M. D., Olson E. N. Control of myogenic differentiation by cellular oncogenes. Mol Neurobiol. 1988 Spring;2(1):1–39. doi: 10.1007/BF02935631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starksen N. F., Simpson P. C., Bishopric N., Coughlin S. R., Lee W. M., Escobedo J. A., Williams L. T. Cardiac myocyte hypertrophy is associated with c-myc protooncogene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986 Nov;83(21):8348–8350. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.21.8348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapscott S. J., Davis R. L., Thayer M. J., Cheng P. F., Weintraub H., Lassar A. B. MyoD1: a nuclear phosphoprotein requiring a Myc homology region to convert fibroblasts to myoblasts. Science. 1988 Oct 21;242(4877):405–411. doi: 10.1126/science.3175662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zak R. Cell proliferation during cardiac growth. Am J Cardiol. 1973 Feb;31(2):211–219. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(73)91034-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]