Abstract

In this study, we evaluated the relative role of the structural and nonstructural proteins of the Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) in inducing protective immunities and compared the results with those induced by the inactivated JEV vaccine. Several inbred and outbred mouse strains immunized with a plasmid (pE) encoding the JEV envelope protein elicited a high level of protection against a lethal JEV challenge similar to that achieved by the inactivated vaccine, whereas all the other genes tested, including those encoding the capsid protein and the nonstructural proteins NS1-2A, NS3, and NS5, were ineffective. Moreover, plasmid pE delivered by intramuscular or gene gun injections produced much stronger and longer-lasting JEV envelope-specific antibody responses than immunization of mice with the inactivated JEV vaccine did. Interestingly, intramuscular immunization of plasmid pE generated high-avidity antienvelope antibodies predominated by the immunoglobulin G2a (IgG2a) isotype similar to a sublethal live virus immunization, while gene gun DNA immunization and inactivated JEV vaccination produced antienvelope antibodies of significantly lower avidity accompanied by a higher IgG1-to-IgG2a ratio. Taken together, these results demonstrate that the JEV envelope protein represents the most critical antigen in providing protective immunity.

Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) is a serious mosquito-borne flavivirus that causes 35,000 cases of encephalitis and 10,000 deaths in humans each year in southern and eastern Asia (31). The majority of JEV infection is subclinical. However, among those with clinical symptoms, the fatality rate ranges from 10 to 50%. Both inactivated (13) and live-attenuated (46) JEV vaccines have been used in Asian countries with measurable success. However, the inherent risks of a live viral vaccine and the adverse effects of the mouse brain-derived inactivated vaccine, most notably allergic reactions (31), have become less well tolerated in areas where JEV disease rates have been greatly reduced. Other major problems associated with the use of inactivated JEV vaccine are the relatively high cost for production and lack of long-term immunity. At least three doses of inactivated JEV vaccine are recommended to increase seroconversion rates, to raise antibody titers, and to lengthen the duration of antibody persistence in vaccinees (15).

The JEV genome contains a single-stranded, positive-sense RNA of approximately 11 kb in length (4). The single open reading frame contained in the genome is translated into a polyprotein which is cleaved co- and posttranslationally into structural and nonstructural proteins (4). The JEV virion contains three structural proteins: an envelope protein (E), a membrane protein (M; precursor M [preM]), and a capsid protein (C). At least seven nonstructural proteins, NS1, NS2A, NS2B, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, and NS5, can be identified in JEV-infected cells. In flaviviruses, the E protein appears to play an important role in inducing protective immunity against virus infection. Monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) to the E protein can provide protection against JEV infection (16, 28). Immunization with extracellular particles composed of preM and E proteins was shown to induce neutralizing antibody and protective immunity (20, 21). Recombinant vaccinia viruses expressing preM and E proteins or E protein alone were highly effective at eliciting protection against JEV challenge in immunized mice (14, 29) and pigs (19). In addition to the structural preM and E proteins, the nonstructural NS1 protein also evoked a strong antibody response which protected the host against challenge with flavivirus, presumably through an Fc-dependent complement-mediated pathway (36). Although the humoral responses to flaviviruses were mainly directed to the E and NS1 proteins, cell-mediated immunities, however, appeared to be directed mainly against other nonstructural proteins. It was previously reported that several dominant cytotoxic T-cell epitopes were identified in the flavivirus NS3 protein (27), and the NS5 protein was able to elicit a strong CD4+-T-cell response in some mouse strains (23). The role of these NS protein-specific T-cell immune responses in viral protection is less clear. A novel vaccination approach that can efficiently induce cellular immune responses is required to address this question.

A recently described vaccine technology, termed nucleic acid vaccine or DNA vaccine, uses DNA instead of protein in the vaccine formulation (40, 41). The expression vectors used for DNA vaccines contain the gene(s) for an antigenic portion of a virus under the transcriptional control of a viral promoter. Direct injection of the plasmid DNA in vivo results in the synthesis of viral proteins in the host and may thus mimic the action of attenuated vaccines. In fact, immunization with antigen-encoding plasmid DNA has been demonstrated in animals ranging from mice to nonhuman primates to induce a broad range of immune responses, including antibodies, CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes, CD4+ helper T lymphocytes, and protective immunity against challenge with the pathogen (9, 11). From these preclinical studies, DNA vaccination seems to be a broadly acceptable technique for generating protective immune responses against infectious pathogens. In addition, the ability of DNA immunization to elicit both antibody and cytotoxic T-cell responses make it an ideal vaccination approach to evaluate the protective efficacy of potential candidate genes.

In the present study, we constructed plasmid vectors encoding various JEV structural and nonstructural proteins and delivered them by both intramuscular and gene gun injection. We found that the plasmid encoding the envelope protein but not other structural and nonstructural proteins elicited a high level of protection against lethal JEV challenge. The protective rate of the E protein-encoding DNA vaccine was equivalent to that induced by the inactivated vaccine. Moreover, DNA vaccination produced much stronger and longer-lasting E-specific antibody responses than those induced by the inactivated JEV vaccine.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Viruses and animals.

The JEV strain Beijing-1 was maintained in suckling mouse brain for preparation of a virus stock used for cloning of the JEV genes as well as for setting up a JEV challenge model. Female BALB/c mice were obtained from the Laboratory Animal Facility, Institute of Biomedical Sciences, Academia Sinica, Taipei, Taiwan. Female C3H/HeN and ICR mice were purchased from National Laboratory Animal Breeding and Research Center, Taipei, Taiwan. Mice were housed at the Laboratory Animal Facility, Institute of Biomedical Sciences, Academia Sinica. To determine the 50% lethal dose (LD50) of the various mouse strains aged 12 to 14 weeks, groups of mice were injected intraperitoneally with a 10-fold serial dilution of JEV Beijing-1 followed by an intracerebral inoculation of 30 μl of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (sham inoculation). The combination of peripheral inoculation of JEV and sham intracerebral inoculation served to increase the susceptibility of mice to a central nervous system infection (26). The LD50s of 12- to 14-week-old C3H/HeN, BALB/c, and ICR mice to JEV Beijing-1 were calculated to be 6.0 × 105, 6.4 × 105, and 3.2 × 105 PFU, respectively. For a lethal challenge experiment, C3H/HeN, BALB/c, and ICR mice were intraperitoneally inoculated with JEV Beijing-1 at a dose of 50 times the LD50 for the respective mouse strain, followed by a sham intracerebral inoculation. The JEV-challenged mice were observed for symptoms of viral encephalitis and death every day for 30 days.

Construction of expression vectors.

The cDNAs of JEV C, E, NS1-2A, NS3, and NS5 proteins were obtained by reverse transcription and PCR amplification of the genomic RNA derived from JEV Beijing-1. Viral RNA was isolated from JEV-infected suckling mouse brain by using RNeasy (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and converted to single-strand cDNA by random hexamers and Moloney leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.). The double-strand cDNA of the various JEV genes were obtained by PCR using appropriate primer sets. The upstream primers contain a BamHI site and an ATG start codon, and the downstream primers contain a stop codon and an EcoRI site, except for the NS5 downstream primer which contains a XhoI site. The PCR products were ligated into pCR-Blunt vector (Invitrogen, San Diego, Calif.) for sequencing and enzyme mapping. The identified plasmids were then digested with appropriate restriction enzymes to release the DNA fragments containing JEV genes and reinserted into pcDNA3 vector (Invitrogen) to produce plasmids pC (bases 96 to 477), pE (bases 933 to 2477), pNS1-2A (bases 2478 to 4214), pNS3 (bases 4608 to 6464), and pNS5 (bases 7677 to 10391) (Fig. 1A). These eukaryotic expression vectors contain the cytomegalovirus early promoter-enhancer sequence and the polyadenylation and the 3′-splicing signals from bovine growth hormone. Plasmid DNA was purified from transformed Escherichia coli DH5α by Qiagen Plasmid Giga Kits in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions and stored at −70°C as pellets. The DNA was reconstituted in sterile saline at a concentration of 1 mg/ml for experimental use.

FIG. 1.

(A) Schematic diagram of plasmid constructs encoding various JEV structural and nonstructural proteins. The first and last nucleotide positions of each gene are shown above the JEV genome. (B) Immunoblot analysis. Cellular proteins of transfected cells were subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by blotting onto nitrocellulose. Nitrocellulose strips were reacted with anti-E, anti-NS1, and anti-NS3 MAbs as indicated and detected with HRP-conjugated second-step antibodies. (C) In vitro-coupled transcription-translation reaction. The gene products produced from various plasmid constructs in the presence of [35S]methionine were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and exposed to X-ray film.

Cell transfection and expression of JEV gene products.

BHK-21 cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) plus 5% bovine calf serum (BCS) in a six-well tissue culture plate until the cells reached approximately 60 to 80% confluence. Plasmid DNA transfection was performed with Lipofectamine (Gibco BRL) as specified by the manufacturer. Briefly, 3 μg of plasmid DNA was mixed with 10 μl of Lipofectamine in 200 μl of OPTI-MEM medium (Gibco BRL) at room temperature. Following a 20-min incubation, the DNA-liposome complexes were diluted in 800 μl of OPTI-MEM and slowly added to cells which had been prewashed twice with 2 ml of PBS. After a 6-h incubation, 2 ml of complete growth medium was added to each well, and incubation was continued for another 48 h. Permanent cells were also generated by culturing transfected cells in complete growth medium containing 500 μg of G418 (Calbiochem-Novabiochem, La Jolla, Calif.) per ml.

Immunoblot analysis was performed as previously described with some modifications (7). In brief, the transiently transfected cells were washed twice with cold PBS and lysed by addition of 300 μl of Nonidet P-40 lysis buffer (1% Nonidet P-40, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris [pH 8.0], protease inhibitor cocktail [Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany]). Following centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C, the lysates were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE [12.5% polyacrylamide]) and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane in transfer buffer (0.1% SDS, 25 mM Tris [pH 8.4], 192 mM glycine, 20% methanol) for 2 h at 50 mA. The filters were first treated with blocking buffer (5% skim milk, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris [pH 8.0]) for 2 h and then incubated with JEV anti-E MAb E3.3 (1 μg/ml) (44), anti-NS1 MAb (5), or anti-NS3 MAb (5) for 1 h at room temperature. Following four 5-min washings in washing buffer (0.05% Tween 20, 1% skim milk, 150 mM Tris [pH 8.0]), the membranes were incubated for 1 h with goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) Fc-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (1:1,000; Cappel, Organon Teknika, Veedijk, Belgium) in PBS-bovine serum albumin (1%). After six 5-min washings, the blots were developed by an enhanced chemiluminescence Western blot detection system (Amersham, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom) and exposed to X-ray film.

For immunofluorescent analysis, the permanently transfected cells were fixed in 10% formalin for 15 min and permeabilized with 0.1% Nonidet P-40 in PBS for another 15 min followed by incubation with MAb E3.3 (5 μg/ml) for 45 min at room temperature. After washing, the cells were further treated with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG Fc (1:200; Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) and fluorescence-positive cells were examined under a Leitz fluorescence microscope.

Analysis of JEV gene products by in vitro-coupled transcription translation.

For some JEV proteins that do not have specific antibodies for use in immunoblot analysis, the gene product of the plasmid DNA was verified by a coupled transcription-translation reaction (Promega, Madison, Wis.) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 1 μg of each plasmid DNA was added to 10 μl of TNT T7 Quick Master Mix and labeled with 10 μCi of [35S]methionine (Amersham, Buckinghamshire, England) per ml in a total volume of 12.5 μl. After a 90-min incubation at 30°C, the translation products were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. The dried gels were then exposed to X-ray film.

Immunization.

For intramuscular DNA immunization, all mice were immunized at 6 to 8 weeks of age as previously described with some modifications (7). In brief, groups of five mice were anesthetized and injected three times at 3-week intervals with 50 μg of DNA bilaterally into each quadricep muscle pretreated 1 week earlier with 100 μl of 10 μM cardiotoxin (Sigma). For some experiments, animals received an intramuscular injection of one or two doses of DNA vaccine at 3-week intervals.

A hand-held, helium-driven Helios gene delivery system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.) was used for gene gun DNA immunization. Plasmid DNA was precipitated onto gold particles with a 1.6-μm average diameter as specified by the manufacturer. The inner surface of a Tefzel tubing was coated with the DNA-gold particle preparation with a tube loader (Bio-Rad), and the tubing was cut into 0.5-inch segments to result in delivery of 0.5 mg of gold and 1 μg of plasmid DNA per shot. Each animal received a gene gun injection into the abdominal epidermis three times at 3-week intervals with a helium pressure setting of 500 lb/in2.

For mice immunized with the inactivated vaccine, a formalin-inactivated mouse brain-derived JEV reference vaccine (Beijing strain) obtained from Tanabe Seiyaku Co. (Osaka, Japan) was used. Each animal was given an intraperitoneal injection of 100 μl (1/10 of a recommended adult dose) of the inactivated vaccine and boosted with the same dose 3 weeks later. A sublethal live virus immunization was performed by intraperitoneal injection of 6.0 × 105 PFU of JEV Beijing-1 without a sham intracerebral inoculation and boosted with the same amount of virus 3 weeks later. All mice survived such treatment without neurologic symptoms.

Antibody assay.

Serum samples were collected by tail bleeding at different time points and analyzed for the presence of JEV E-specific antibodies. Microtiter plates were coated with formalin-inactivated or live JEV produced by Vero cells in roller bottle cultures. After incubation with 200 μl of 5% powdered milk in PBS in each well for 2 h at 37°C to prevent nonspecific binding, 50 μl of a serial dilution of the test serum was added to each well and incubated overnight at 4°C. After the samples were washed three times with PBS-Tween 20 (0.05%) and five times with PBS, bound proteins were detected with HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG Fc (1:1000; Cappel). Color was generated by adding 2,2′-azino-bis(ethylbenzthiazoline sulfonic acid) (Sigma), and the absorbance at 405 nm was measured on an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) reader. The readings were referenced to a standard serum pooled from five mice given intraperitoneal injections of inactivated JEV with aluminum hydroxide at weeks 0 and 2 and bled at week 4. The standard curve was generated by using the pooled anti-JEV sera, and results were expressed as arbitrary units per milliliter (1 U = 50% maximum optical density). The concentration of 1 U/ml is equal to 22 ng of anti-E antibody/ml. For measurement of IgG1 and IgG2a anti-E isotypes, biotin-conjugated rat anti-mouse IgG1 (1:1,000; PharMingen, San Diego, Calif.) and rat anti-mouse IgG2a (1:1000, PharMingen) were used as detectors. Avidin-HRP (1:2,000; PharMingen) was then added. Color was developed as described above. End-point titers were defined as the highest serum dilution that resulted in an absorbance value two times greater than that of nonimmune serum with a cutoff value of 0.05. Samples below the limit of detection were assigned a value of 10, since the tested serum was diluted starting from a dilution of 1:10.

The avidity of the anti-E antibody was determined by antigen competition as previously described (8) with some modification. Briefly, the E-specific titer of each tested serum sample was predetermined by ELISA as described above, and the dilution of each serum giving an optical density of 0.8 was used in the following competition assay. First, serial dilutions of inactivated JEV in 25 μl of BCS-PBS were made in the antigen-coated plates, leaving one set of wells without free viral particles as a positive control. Then, 25 μl of the appropriate dilution of each serum sample was added to each well and the plates were incubated at 37°C for 2 h. After washing, HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG was added and the ELISA was processed as described above. The percent inhibition was plotted against the reciprocal of free antigen dilution added to the well, and the reciprocal of free antigen dilution required for 50% inhibition (I50) was taken as a measure of avidity.

The neutralization test was carried out by the 50% plaque reduction technique with BHK-21 cells. A twofold dilution of serum was prepared in 5% BCS–PBS. Dilutions were incubated at 56°C for 30 min to inactivate the complement and then mixed with equal volumes of infectious JEV in minimum essential medium (MEM) supplemented with 5% BCS to yield a mixture containing approximately 1,000 PFU of virus/ml. The virus-antibody mixtures were incubated at 4°C for 18 to 21 h and then added to triplicate wells of six-well plates containing confluent monolayers of BHK-21 cells. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 1 h with gentle rocking every 15 min. The wells were then overlaid with 2 ml of 1% methyl cellulose prepared in MEM supplemented with 5% BCS and incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 3 days. Plaques were stained with naphthol blue black and counted. The neutralizing antibody titer was calculated as the reciprocal of the highest dilution resulting in a 50% reduction of plaques compared to that of a control of virus with no added antibody.

Statistical analysis.

The statistical significance of differential findings between experimental groups of animals was determined by Fisher’s exact test. Data was considered statistically significant if P was ≤0.05.

RESULTS

Construction and characterization of expression vectors.

The JEV genome contains a large open reading frame that is translated into three structural and seven nonstructural proteins (4). To evaluate the relative role of these structural and nonstructural proteins in inducing protective immunity against JEV, the genetic fragments corresponding to the core, envelope, NS1-2A, NS3, and NS5 proteins were inserted into a eukaryotic expression vector, pcDNA3, to produce plasmids pC, pE, pNS1-2A, pNS3, and pNS5 (Fig. 1A), respectively. BHK-21 cells were transiently transfected with plasmid pE, pNS1-2A, or pNS3 with the parental plasmid serving as a negative control. At 2 days after transfection, the protein products in the transfected cells were analyzed by immunoblotting techniques. It was found that plasmids pE and pNS3 directed the synthesis of apparently authentic E and NS3 proteins, respectively, with apparent molecular masses (Ms) of 56 kDa for E and 70 kDa for NS3 (Fig. 1B). The control vector did not produce protein products recognized by either anti-E or anti-NS3 MAbs. Plasmid pNS1-2A expressed a protein product with an apparent molecular mass close to that of NS1 (Ms ∼ 45 kDa) but not that of NS1-2A (Ms ∼ 67 kDa) (Fig. 2B), indicating that the newly synthesized NS1-2A protein was quickly subjected to protease-mediated cleavage in the transfected cells. We also used an indirect immunofluorescence assay to demonstrate that the transfected E protein was localized mainly in the cytoplasmic region (data not shown). Since the core- and NS5-specific antibodies were not available for us to perform immunoblotting analysis, we used an in vitro-coupled transcription and translation reaction to analyze the gene products produced by plasmids pC and pNS5. As shown in Fig. 1C, plasmids pC, pNS3, and pNS5 were able to express proteins of their respective authentic size; in contrast, the parental pcDNA3 vector did not produce detectable protein product in this reaction.

FIG. 2.

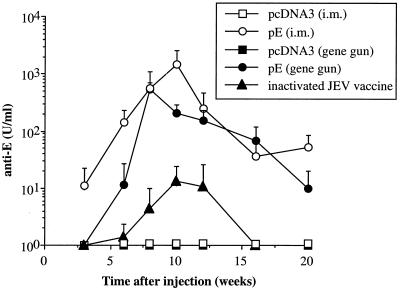

Kinetics of anti-E antibodies in C3H/HeN mice immunized with DNA or inactivated JEV vaccines. C3H/HeN mice were given intramuscular (i.m.) or gene gun injections of plasmid pE or pcDNA3 three times at 3-week intervals. The inactivated JEV vaccine was administered intraperitoneally and boosted once 3 weeks later. Sera were obtained at different time points and assayed for the presence of JEV E-specific antibodies. The concentration of anti-E antibodies was calculated from the standard curve generated from serially diluted control antibodies and expressed as units per milliliter. The data are presented as means ± standard deviations for five animals per time point.

Protective immunities induced by various JEV structural and nonstructural genes.

To verify which gene products can provide protective immunity against JEV infection, female C3H/HeN mice were immunized by intramuscular or gene gun injection with plasmids encoding various JEV structural and nonstructural proteins and followed by a lethal JEV challenge. C3H/HeN mice were initially chosen in this challenge study because they were reported to be more sensitive to JEV infection than other inbred mouse strains (30). For intramuscular DNA immunization, a total of 100 μg of DNA was delivered, while the gene gun immunization used only 1 μg of DNA per dose. Following primary immunization, animals were boosted twice with the same amount of DNA at 3-week intervals with the same immunization method and challenged 2 weeks after the last immunization with a high dose (3 × 107 PFU; 50 LD50s) of JEV. The animals were monitored daily for morbidity and mortality. Table 1 summarizes results obtained from two to three independent experiments. Mice immunized with the control plasmid pcDNA3 were not protected against viral challenge, with only one animal surviving in the many experiments performed. Similarly, plasmids encoding the core, NS1-2A, or NS3 proteins administered by either route of DNA immunization did not produce significant protection. In sharp contrast, immunization of plasmid pE by either the intramuscular or gene gun route resulted in a high level of protection, with 89% (25 of 28, P < 0.0001) and 91% (21 of 23, P < 0.0001) of animals, respectively, surviving the challenge (>30 days after viral challenge). Plasmid pNS5 delivered by gene gun injection produced a low (27%, 3 of 11) but significant level of protection (P < 0.05), whereas intramuscular injection of the same plasmid resulted in no long-term survivors. These results clearly demonstrate that the E protein is the single most important protective antigen among the many JEV structural and nonstructural proteins.

TABLE 1.

Summary of survivor rate of C3H/HeN mice immunized with DNA vaccines encoding various JEV structural and nonstructural proteins after a lethal challenge

| Immunogena | Intramuscular injection

|

Gene gun injection

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of survivors/total no. | % Of survivorsb | No. of survivors/total no. | % Of survivors | |

| pcDNA3 | 1/28 | 3 | 0/22 | 0 |

| pC | 0/10 | 0 | 0/10 | 0 |

| pE | 25/28 | 89c | 21/23 | 91c |

| pNS1-2A | 2/13 | 15 | 1/16 | 6 |

| pNS3 | 1/10 | 10 | 0/11 | 0 |

| pNS5 | 0/10 | 0 | 3/11 | 27d |

C3H/HeN mice were immunized with plasmid DNA by intramuscular or gene gun injections at a dose of 100 or 1 μg, respectively, three times at 3-week intervals. Mice were challenged 2 weeks after the last immunization with 50 LD50s of JEV Beijing-1 and monitored for mortality for 30 days.

Results are presented as a summary of two to three independent experiments.

Statistically significant at a P of <0.0001 by Fisher’s exact test compared to the value for the pcDNA3 group.

Statistically significant at a P of <0.05 by Fisher’s exact test compared to the value for the pcDNA3 group.

Comparative analysis of immunities induced by plasmid pE and the inactivated JEV vaccine.

We then performed a time course study of the antibody titers to compare the vaccine efficacies of the inactivated JEV vaccine and the DNA vaccine encoding the JEV E protein. The plasmid DNA was delivered intramuscularly by a syringe or epidermally by a gene gun three times at 3-week intervals as described in the above section. The inactivated viral vaccine was administered intraperitoneally at a dose of 100 μl (1/10 of a recommended adult dose) and boosted once 3 weeks later. Serum from each mouse obtained at different time intervals following injection was analyzed for JEV E-specific antibody response. As shown in Fig. 2, mice immunized with the control plasmid pcDNA3 by intramuscular or gene gun injection did not produce any anti-E antibodies in any of the serum samples tested. In contrast, mice immunized intramuscularly with plasmid pE first revealed IgG anti-E antibodies at week 3 along with a 60% seroconversion rate. All of these mice had seroconverted at week 6, and the E-specific antibody titers significantly increased following each immunizing boost. Mice that received pE by gene gun immunization showed slower antibody responses than those that received intramuscularly injected DNA. At week 3, none of the mice that received gene gun immunization of pE produced detectable E-specific antibodies. Nonetheless, at week 6 following one booster gene gun immunization, a significant amount of anti-E antibodies was detected in all pE-immunized mice and at week 8 the mean titer was further increased to a level similar to that obtained by intramuscular DNA immunization. We found that mice immunized with the inactivated viral vaccine produced anti-E antibody titers that were greatly inferior to those obtained in DNA-immunized mice. At week 6 following one booster immunization, the anti-E titers generated by the inactivated viral vaccine and the DNA vaccine via intramuscular or gene gun injection were 1.4, 142.8, and 11.6, respectively. Analysis of peak antibody titers showed that intramuscular and gene gun DNA immunization produced 111- and 41-fold more antibodies, respectively, than that of the inactivated JEV vaccine. DNA immunization also induced longer-lasting antibody titers than the inactivated viral vaccine. At week 20, significant titers of anti-E antibodies were still present in animals that received DNA immunization intramuscularly or via gene gun (Fig. 2). In contrast, no E-specific antibodies were detected in the viral vaccine-immunized group at week 16.

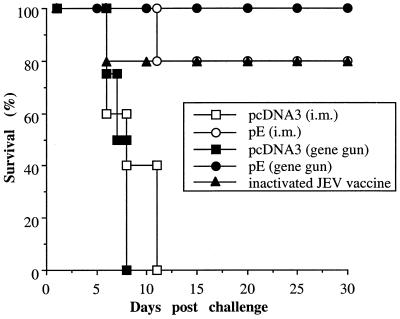

The DNA immunization was then compared to the conventional inactivated viral vaccine for its efficacy in inducing protection against a lethal JEV challenge. Mice were immunized with pE by intramuscular or gene gun inoculation or with the inactivated JEV vaccine as described in the previous section and challenged 2 weeks after the last immunization. One representative result is shown in Fig. 3. Mice of the control groups, immunized with pcDNA3 by intramuscular or gene gun injection, began to show symptoms of paralysis as early as day 5 following JEV infection, and all animals succumbed to challenge by day 11. In contrast, none of the mice immunized with plasmid pE by gene gun showed any symptom of viral encephalitis and all survived the viral challenge. The intramuscular injection of pE also resulted in 80% long-term survivors, which was comparable to that achieved by the inactivated viral vaccine. The challenge experiments were performed several times, and similar results were observed in each case. Overall, 92% (24 of 26) of animals immunized with the inactivated viral vaccine survived the viral challenge. This ratio of protection was similar to that achieved by DNA immunization with plasmid pE (89% for intramuscular injection and 91% for gene gun injection) (Table 1).

FIG. 3.

Mice immunized with DNA or inactivated viral vaccines protected from lethal JEV challenge. Groups of C3H/HeN mice were immunized with the inactivated JEV vaccine or plasmid pE or pcDNA3 by intramuscular (i.m.) or gene gun injections as detailed in the legend to Fig. 2. Two weeks after the last immunization, mice were challenged with 50 LD50s of JEV Beijing-1 as described in Materials and Methods. Following challenge, mice were observed for 30 days and the percentage of survivors was calculated.

Characterization of antibody responses induced by DNA and conventional JEV vaccines.

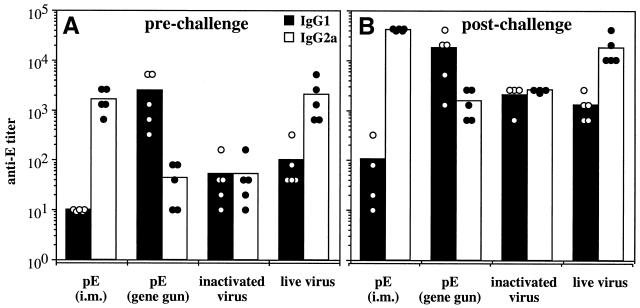

The different vaccination approaches and the route of antigen delivery can affect the antibody isotype and T-helper cell type of an immune response. IgG2a is produced as a consequence of Th1-cell activation, whereas Th2-cell activation enhances the production of IgG1 and suppresses IgG2a (1, 32). We analyzed the IgG isotype profiles produced by intramuscular and gene gun DNA immunization and compared them with profiles generated by two conventional methods of vaccination, the inactivated virus vaccination and a sublethal live virus immunization. To reflect immunity elicited by subclinical infection with JEV, the live virus immunization was performed by intraperitoneal injection of 6.0 × 105 PFU of JEV Beijing-1 without a simultaneous intracerebral inoculation of PBS. The sublethal JEV infection induced high titers of anti-E antibodies (298 ± 112 U/ml [mean ± standard deviation]) relative to those produced by either method of DNA immunization (195 ± 142 and 537 ± 157 U/ml for intramuscular and gene gun injections, respectively). The inactivated viral vaccine produced only low titers of anti-E antibodies. With regards to the IgG subclass profiles, the sublethally immunized mice produced more IgG2a than IgG1 anti-E antibody, while the inactivated virus-vaccinated mice generated low but equal titers of IgG1 and IgG2a antibody (Fig. 4A). Plasmid pE delivered by intramuscular injection generated almost exclusively IgG2a anti-E antibody in every immunized animal, whereas IgG1 antibody was not detectable (<1:10). In contrast, gene gun DNA immunization produced mostly IgG1 anti-E antibody, with only low titers of IgG2a antibody induced. These results suggest that the two modes of JEV DNA immunization induced different subsets of helper-T-cell responses. We also found that the isotype profiles generated by the initial immunization were stable. A lethal JEV challenge of the immunized mice increased the quantity of the antibody responses but did not alter the isotype nature of mice in the different immunized groups (Fig. 4B).

FIG. 4.

Isotypes of anti-E antibodies generated by DNA or conventional viral vaccines. Groups of C3H/HeN mice were immunized with DNA or inactivated JEV vaccines as described in the legend to Fig. 2 or were sublethally immunized twice at 3-week intervals with 6.0 × 105 PFU of JEV Beijing-1 as described in Materials and Methods. Two weeks after the last immunization, mice were challenged with 50 LD50s of JEV Beijing-1. Sera were collected prechallenge (A) and 2 weeks postchallenge (B) and analyzed for the presence of IgG1 and IgG2a anti-E antibodies. Concentrations of IgG1 and IgG2a anti-E antibodies were presented as end-point titers defined as the highest serum dilution that resulted in an absorbance value two times greater than that of nonimmune serum with a cutoff value of 0.05. Samples below the limit of detection were assigned a value of 10. The titer of individual animals and the mean titers of each immunized group are presented. i.m., intramuscular.

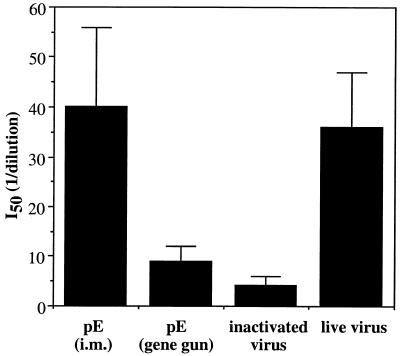

We then measured the avidities of the anti-E antibody generated by intramuscular and gene gun DNA immunizations and compared them with those induced by live or inactivated JEV vaccines. The anti-E avidity of each serum sample was determined by calculating the concentration of inactivated JE viral proteins required to inhibit the ELISA reactivity by 50% during the linear part of the response curve (I50). As shown in Fig. 5, the avidity of the anti-E antibody elicited by intramuscular DNA immunization was comparable to that elicited by live virus immunization but was about 10-fold higher than that elicited in the serum samples from mice immunized with the inactivated JEV vaccine. Surprisingly, we found that gene gun DNA immunization generated anti-E antibody of significantly lower avidity than that generated by intramuscular DNA immunization, although both methods produced equivalent titers of total IgG anti-E antibody (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Avidity of anti-E antibodies generated by DNA or conventional viral vaccines. Mice were immunized as described in the legend to Fig. 4. Sera collected two weeks after the last immunization were analyzed for antibody avidity. The tested sera from each group were adjusted to contain equal anti-E titers before use. The avidity is reported as the reciprocal dilution of inactivated JEV particles added to the well that resulted in a 50% binding inhibition of each immune serum sample (I50). Data represent the mean I50 ± standard deviation for five animals in each group from one representative experiment of three performed. i.m., intramuscular.

The ability of the antiserum of the different immunized groups to neutralize JEV infection in vitro was carried out by plaque reduction neutralization tests (PRNT). The prechallenge PRNT titers were not detectable (<1:10) in mice immunized with the inactivated viral vaccine or the pE DNA vaccine delivered by intramuscular or gene gun injection (Table 2). Nonetheless, most of the mice in these groups survived a lethal JEV challenge and displayed low PRNT titers (1:40) at 2 weeks postchallenge. Mice immunized with the sublethal JEV infection had low PRNT titers (1:40) in their prechallenge sera, and the neutralization activity was significantly increased (1:320) in the postchallenge sera.

TABLE 2.

Plaque reduction neutralization titers in pre- and postchallenge sera obtained from mice immunized with DNA or conventional JEV vaccines

| Immunogena | Routeb | Dose | Wk of immunization | PRNT titerc

|

Survivald | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prechallenge | Postchallenge | |||||

| pE | i.m. | 100 μg | 0, 3, 6 | <1:10 | 1:40 | 7/8 |

| pE | g.g. | 1 μg | 0, 3, 6 | <1:10 | 1:40 | 8/8 |

| Inactivated virus | i.p. | 100 μl | 0, 3 | <1:10 | 1:40 | 4/5 |

| Live virus | i.p. | 6.0 × 105 PFU | 0, 3 | 1:40 | 1:320 | 10/10 |

C3H/HeN mice were immunized and challenged as described in the legend to Fig. 4.

i.m., intramuscular; g.g.; gene gun; i.p., intraperitoneal.

Represented as the serum dilution yielding 50% reduction in plaque number.

Number of survivors divided by total number of mice tested 30 days after challenge with 50 LD50s of JEV Beijing-1.

DNA vaccination is highly effective in induction of protective immunities in different mouse strains.

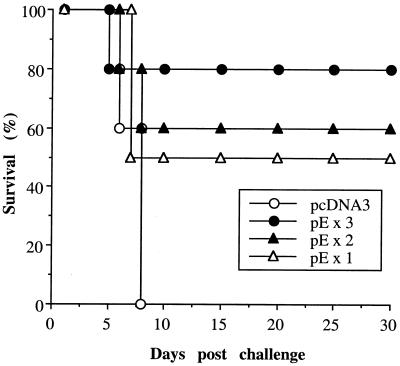

To determine the minimal number of injections of plasmid DNA required to induce protective immunities, plasmid pE was administered intramuscularly to groups of C3H/HeN mice once, twice, or three times at 3-week intervals. The plasmid pcDNA3-immunized group served as a negative control. Mice that received one DNA immunization were challenged at week 3 with 50 LD50s of JEV, and those that received two or three DNA inoculations were challenged 2 weeks following the last immunization. As expected, none of the mice in the control group survived the JEV challenge, whereas for the mice in the pE-immunized group, a dose response of protection was observed with increasing numbers of vaccinations (Fig. 6). Administration of one, two, or three doses of DNA vaccines resulted in 50, 60, and 80% long-term survivors, respectively. These values are not significantly different from one another but are significantly different from the survival value of mice immunized with the control vector (P < 0.05).

FIG. 6.

Effect of injection numbers on DNA vaccine-induced protective immunities. C3H/HeN mice were given an intramuscular injection of pE either one, two, or three times at 3-week intervals. Mice immunized intramuscularly with pcDNA3 three times at 3-week intervals served as negative controls. Animals that received one dose of DNA immunization were challenged with 50 LD50s of JEV Beijing-1 at week 3, and those that received two or three DNA inoculations were challenged 2 weeks after the last immunization. Following challenge, mice were observed for 30 days and the percentage of survivors was calculated.

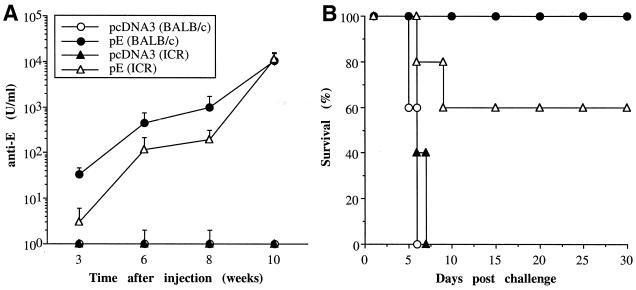

The ability of DNA vaccines to induce antibody responses and protective immunities was also evaluated in an outbred mouse strain, ICR, and another inbred strain, BALB/c. Groups from each strain of animals were injected intramuscularly with three doses of either pcDNA3 or pE at 3-week intervals and challenged 2 weeks following the last immunization. As shown in Fig. 7A, immunization with pE but not the control pcDNA3 plasmid resulted in E-specific antibody responses in both ICR and BALB/c mice. However, the results in BALB/c mice were superior to those in ICR mice in both the rate of appearance and the titers of specific antibodies. At week 3 following one dose of immunization, all BALB/c mice had seroconverted in comparison to a 60% seroconversion rate in ICR mice. Following each immunizing boost, specific antibody titers were significantly increased in both BALB/c and ICR mice. However, like what was found in the C3H/HeN mice, we could not detect PRNT titers in the prechallenge sera of these two mouse strains. With respect to protection, despite the fivefold-higher anti-E titers found in BALB/c than in ICR mice before challenge, there was no significant difference in viral protection between the two mouse strains (P > 0.05). Immunization with plasmid pE resulted in 100 and 60% long-term survivors in BALB/c and ICR mice, respectively, while none of the animals immunized with the control plasmid survived the challenge (Fig. 7B).

FIG. 7.

Anti-E antibody and protective immunity induced by JEV DNA vaccination in different mouse strains. Groups of BALB/c and ICR mice were immunized intramuscularly with plasmid pE or pcDNA3 and challenged with a lethal dose of JEV as detailed in the legend to Fig. 3. The anti-E antibody at different time points (A) and the percentage of survivors (B) in each immunized group are shown.

DISCUSSION

DNA vaccines represent a novel vaccination technique that shows great promise to elicit potent humoral and cytotoxic cellular immune responses (9, 11). In addition, the inherent simplicity of DNA immunization should allow the rapid identification of protective antigens from the genome of a pathogen for production of multivalent vaccines. In this study, we constructed plasmid vectors encoding several different JEV structural and nonstructural proteins and evaluated their capacity to elicit protective immunity in a mouse challenge model. We found that plasmids encoding the envelope protein but not core, NS1-2A, NS3, or NS5 proteins elicited a high level of protection against a lethal JEV challenge. Compared to the currently used inactivated JEV vaccine, immunization with plasmid pE produced not only an equivalent level of protection but also a much stronger and longer-lasting antibody response. This result remained true when these two vaccines were administered on the same immunization schedule.

The E glycoprotein is the major virion antigen responsible for a number of important processes, including virion assembly, receptor binding, and membrane fusion, and is the principal target for neutralization in vitro and in vivo by specific antibodies (17, 39). Virus-like particles composed of preM and E proteins (20, 21) and recombinant vaccinia viruses expressing preM and E proteins (14, 19, 29) were shown to induce neutralizing antibodies and protective immunities. In the present study, we show that DNA vaccination using a plasmid encoding the E protein alone confers a high level of protection. In C3H/HeN mice, a highly sensitive JEV challenge model (30), intramuscular and gene gun DNA immunization resulted in 89 and 91% rates of protection (Table 1), respectively, compared to 92% achieved by conventional inactivated vaccines. Similar protective immunity produced by plasmid pE was also observed in another inbred population and in an outbred ICR strain (Fig. 7). We also provided evidence that even a single dose of DNA immunization was able to elicit protective immunities against a high dose of JEV challenge (Fig. 6). Taken together, these results demonstrate that DNA vaccination using a plasmid encoding the E protein alone is a highly effective means of protection against JEV infection.

In contrast to the high level of protective immunity induced by the E gene, all of the other JEV genes tested in this study produced no significant protection except the NS5 gene, which yielded a low but significant level of protection (27%) when delivered by gene gun (Table 1). This is a somewhat surprising result, particularly for the plasmid encoding the NS1-2A protein. Previous reports showed that NS1-specific antibodies either passively delivered or induced by immunization of the NS1 protein were able to protect the host against challenge with flaviviruses (42). Moreover, a plasmid DNA (pJNS1) encoding the JEV NS1 protein alone was reported to be highly effective in inducing robust protection (25). Compared to plasmid pJNS1, our pNS1-2A construct produced much less NS1 protein in transiently transfected cells (data now shown), possibly due to the presence of the additional NS2A sequence. One explanation is that the low amount of NS1 protein produced by plasmid pNS1-2A renders this DNA vaccine ineffective. However, we have recently performed a side-by-side study to compare the relative protective efficacies of plasmids encoding the E, NS1, or NS1-2A proteins. Our results showed that plasmids carrying the NS1 or NS1-2A genes conferred little protection against a high-dose (50-LD50) JEV challenge, while a high percentage of mice immunized with plasmid pE survived the challenge (unpublished data). NS3 and NS5 proteins are highly conserved among flaviviruses and are considered to be involved in viral genome replication (4). It was reported that cell-mediated immunities, including both CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes, were directed mainly against these conserved nonstructural proteins (23, 27). Since DNA vaccination is considered to be extremely effective in inducing cellular immunities, the failure of plasmid pNS3 and pNS5 to confer protection against JEV suggests that the T-cell responses to these two proteins do not play significant protective roles. Taken these results together, we believe that the E protein is the single most important protective antigen among the many JEV structural and nonstructural proteins.

It was previously reported that in the JEV challenge model the level of protection was correlated to the production of neutralizing antibodies (29). Surprisingly, we could not detect the prechallenge PRNT titers (<1:10) in mice immunized with plasmid pE by intramuscular or gene gun injection (Table 2), even though both DNA vaccination approaches generated high titers of anti-E antibodies that were able to recognize JE viral particles in an ELISA. The inactivated JEV vaccine also did not produce detectable PRNT titers before viral challenge. Only mice immunized with the live JEV vaccine were able to produce neutralizing antibodies in the prechallenge sera (Table 2). Analysis of the anti-E antibodies in individual mice immunized with the various JEV vaccines showed no direct correlation between viral protection and the antibody titers. Similarly, the low to nonexistent PRNT titers observed in sera of the prechallenged animals suggest that sterilized immunity was not achieved by vaccination. Indeed, we found that the anti-E titers were greatly increased (Fig. 4 and Fig. 7A) and the neutralization antibodies were induced or expanded following viral challenge (Table 2). These results suggest that DNA and conventional viral vaccinations induced priming of neutralization responses that did not completely block JEV infection, but the titers resulting from these vaccinations were quickly boosted following viral challenge to a level that was able to provide protection. Another possible protective mechanism that may be induced by plasmid pE immunization is the E-specific T-cell immunity. However, our preliminary data showed that adoptive transfer of splenocytes or T cells from animals immunized with DNA vaccine did not provide protection against viral challenge. This result strongly suggests that T-cell immunity does not play a significant role in providing protection against JEV challenge.

It was previously demonstrated that cosynthesis of preM was required for proper folding, membrane association, and assembly of the flavivirus E protein (18). Further support for the requirement of coordinated synthesis of the preM protein came from the observation that preM and E proteins were present as heterodimers in the cell-associated forms of West Nile virus (43). pE, the plasmid used in the present study, encodes the full-length E protein with only 15 amino acids from the C-terminal end of the M protein serving as a signal sequence. It is likely that the pE-encoded E protein does not adopt a proper structural conformation and thus may explain the low PRNT titer generated by this particular JEV DNA vaccine. By using recombinant vaccinia viruses, it was previously demonstrated that only the virus that expressed the preM in addition to the E and NS1 proteins produced extracellular forms of E and induced a better protective immunity (29). It is thus reasonable to speculate that a plasmid vector encoding both preM and E proteins may serve as a better DNA vaccine. Recent studies by Lin et al. (25) and Konishi et al. (22) showed that plasmids encoding preM and E proteins have the ability to induce protective immune responses against a lethal JEV challenge. A direct comparison of plasmids expressing preM and E or E alone is currently ongoing in our laboratory to elucidate the role of preM on the efficacy of a JEV DNA vaccine.

It has been previously reported that gene gun DNA immunization uses, in general, 100- to 1,000-fold less DNA than intramuscular DNA immunization to generate an equivalent antibody response (33). In the present study, we confirm these previous findings by showing that gene gun delivery of the JEV DNA vaccine into epidermis was a very efficient method of immunization, achieving protection with 100 times less DNA than direct intramuscular inoculation of purified DNA in saline (Fig. 3 and Table 1). In addition, there are striking differences in the isotype profile and avidity of the specific antibodies induced by these two DNA vaccination approaches. Plasmid pE delivered by intramuscular injection generated almost exclusively IgG2a anti-E antibody, while gene gun DNA immunization produced mostly IgG1 antibody (Fig. 4). Since the isotype profile of an antibody response is a reflection of the T-helper cell types (1, 32), our results suggest that intramuscular and gene gun JEV DNA immunizations induce Th1- and Th2-type T-cell responses, respectively. Other studies also demonstrated that the route (intramuscular versus intradermal injection) (3, 38), method (needle versus gene gun injection) (10), antigen location (secreted versus cell associated) (2, 12), and interval between immunizations (24) were important factors that influenced the relative levels of IgG1 and IgG2a antibodies. The underlying mechanism for generation of these different immune responses by DNA-based immunization is not clear at present but may be related to the presence of certain cytokines at the site of primary antigen stimulation of naive cells, the effective concentration of antigen presented to T cells, and the nature of antigen-presenting cells. Indeed, we and others have demonstrated that codelivery of cytokine genes with the DNA vaccines can substantially influence the differentiation of T-helper cells as well as the nature of an immune response (6, 37, 45). Another interesting finding observed in the present study is that the avidity of the anti-E antibody elicited by intramuscular DNA immunization was significantly higher than that generated by gene gun DNA immunization or the inactivated JEV vaccine (Fig. 5). Boyle et al. (3) recently reported that immunization with a plasmid encoding ovalbumin by intramuscular or intradermal inoculation dramatically enhanced the avidity of the antibody in comparison with that resulting from soluble ovalbumin immunization. However, the avidity of the antibody produced by alum-precipitated ovalbumin was equivalent to that generated by DNA immunization. It is thus likely that the higher avidity of the anti-E antibody elicited by intramuscular DNA immunization relative to that elicited by gene gun immunization in the present study was due to the adjuvant activity of the high-dose DNA used in the intramuscular vaccination approach. More experiments are needed to prove this hypothesis.

In summary, we have shown that a DNA vaccine containing the JEV envelope gene is highly effective in inducing protective immunity equal to that induced by the currently used conventional inactivated JEV vaccine. Other groups have also reported that immunization with DNA vaccines expressing the JEV preM and E proteins (22) was able to provide protection against a lethal JEV challenge. DNA vaccines against other members of the family Flaviviridae, including St. Louis encephalitis virus (34) and dengue virus (35), have also been recently reported. In addition to their ability to induce a full spectrum of long-lasting humoral and cellular immune responses, DNA vaccines possess other advantages compared to conventional inactivated or live attenuated vaccines, including high-temperature stability, low cost for mass production, and relative safety in application. Taking these results together, we believe that the DNA vaccine approach is well suited to the development of an effective flavivirus vaccine.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

H.-W. Chen and C.-H. Pan contributed equally to this work.

We thank Mei-Shang Ho and Wenlii Lin for many helpful discussions.

This work was supported by grant DOH86-HR-605 from National Health Research Institutes, Taiwan, Republic of China.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abbas A K, Murphy K M, Sher A. Functional diversity of helper T lymphocytes. Nature. 1996;383:787–793. doi: 10.1038/383787a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boyle J S, Koniaras C, Lew A M. Influence of cellular location of expressed antigen on the efficacy of DNA vaccination: cytotoxic T lymphocyte and antibody responses are suboptimal when antigen is cytoplasmic after intramuscular DNA immunization. Int Immunol. 1997;9:1897–1906. doi: 10.1093/intimm/9.12.1897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boyle J S, Silva A, Brady J L, Lew A M. DNA immunization: induction of higher avidity antibody and effect of route on T cell cytotoxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:14626–14631. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chambers T J, Hahn C S, Galler R, Rice C M. Flavivirus genome organization, expression, and replication. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1990;44:649–688. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.44.100190.003245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen L K, Liao C L, Lin C G, Lai S C, Liu C I, Ma S H, Huang Y Y, Lin Y L. Persistence of Japanese encephalitis virus is associated with abnormal expression of the nonstructural protein NS1 in host cells. Virology. 1996;217:220–229. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chow Y H, Chiang B L, Lee Y L, Chi W K, Lin W C, Chen Y T, Tao M H. Development of Th1 and Th2 populations and the nature of immune responses to hepatitis B virus DNA vaccines can be modulated by codelivery of various cytokine genes. J Immunol. 1998;160:1320–1329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chow Y H, Huang W L, Chi W K, Chu Y D, Tao M H. Improvement of hepatitis B virus DNA vaccines by plasmids coexpressing hepatitis B surface antigen and interleukin-2. J Virol. 1997;71:169–178. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.1.169-178.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Devey M E, Bleasdale K, Lee S, Rath S. Determination of the functional affinity of IgG1 and IgG4 antibodies to tetanus toxoid by isotype-specific solid-phase assays. J Immunol Methods. 1988;106:119–125. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(88)90279-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donnelly J J, Ulmer J B, Shiver J W, Liu M A. DNA vaccines. Annu Rev Immunol. 1997;15:617–648. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feltquate D M, Heaney S, Webster R G, Robinson H L. Different T helper cell types and antibody isotypes generated by saline and gene gun DNA immunization. J Immunol. 1997;158:2278–2284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gregoriadis G. Genetic vaccines: strategies for optimization. Pharmaceut Res. 1998;15:661–670. doi: 10.1023/a:1011950415325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haddad D, Liljeqvist S, Stahl S, Perlmann P, Berzins K, Ahlborg N. Differential induction of immunoglobulin G subclasses by immunization with DNA vectors containing or lacking a signal sequence. Immunol Lett. 1998;61:201–204. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(97)00171-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoke C H, Nisalak A, Sangawhipa N, Jatanasen S, Laorakapongse T, Innis B L, Kotchasenee S, Gingrich J B, Latendresse J, Fukai K, Burke D S. Protection against Japanese encephalitis by inactivated vaccines. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:608–614. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198809083191004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jan L R, Yang C S, Henchal L S, Sumiyoshi H, Summers P L, Dubois D R, Lai C J. Increased immunogenicity and protective efficacy in outbred and inbred mice by strategic carboxyl-terminal truncation of Japanese encephalitis virus envelope glycoprotein. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1993;48:412–423. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1993.48.412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Juang R F, Okuno Y, Fukunaga T, Tadano M, Fukai K, Baba K, Tsuda N, Yamada A, Yabuuchi H. Neutralizing antibody responses to Japanese encephalitis vaccine in children. Biken J. 1983;26:25–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kimura-Kuroda J, Yasui K. Protection of mice against Japanese encephalitis virus by passive administration with monoclonal antibodies. J Immunol. 1988;141:3606–3610. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kimura-Kuroda J, Yasui K. Topographical analysis of antigenic determinants on envelope glycoprotein V3(E) of Japanese encephalitis virus, using monoclonal antibodies. J Virol. 1983;45:124–132. doi: 10.1128/jvi.45.1.124-132.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Konishi E, Mason P W. Proper maturation of the Japanese encephalitis virus envelope glycoprotein requires cosynthesis with the premembrane protein. J Virol. 1993;67:1672–1675. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.3.1672-1675.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Konishi E, Pincus S, Paoletti E, Laegreid W W, Shope R E, Mason P W. A highly attenuated host range-restricted vaccinia virus strain, NYVAC, encoding the prM, E, and NS1 genes of Japanese encephalitis virus prevents JEV viremia in swine. Virology. 1992;190:454–458. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)91233-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Konishi E, Pincus S, Paoletti E, Shope R E, Burrage T, Mason P W. Mice immunized with a subviral particle containing the Japanese encephalitis virus prM/M and E proteins are protected from lethal JEV infection. Virology. 1992;188:714–720. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90526-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Konishi E, Win K S, Kurane I, Mason P W, Shope R E, Ennis F A. Particulate vaccine candidate for Japanese encephalitis induces long-lasting virus-specific memory T lymphocytes in mice. Vaccine. 1997;15:281–286. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(96)00180-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Konishi E, Yamaoka M, Khin-Sane-Win, Kurane I, Mason P W. Induction of protective immunity against Japanese encephalitis in mice by immunization with a plasmid encoding Japanese encephalitis virus premembrane and envelope genes. J Virol. 1998;72:4925–4930. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.6.4925-4930.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kulkarni A B, Mullbacher A, Parrish C R, Westaway E G, Coia G, Blanden R V. Analysis of murine major histocompatibility complex class II-restricted T-cell responses to the flavivirus Kunjin by using vaccinia virus expression. J Virol. 1992;66:3583–3592. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.6.3583-3592.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leitner W W, Seguin M C, Ballou W R, Seitz J P, Schultz A M, Sheehy M J, Lyon J A. Immune responses induced by intramuscular or gene gun injection of protective deoxyribonucleic acid vaccines that express the circumsporozoite protein from Plasmodium berghei malaria parasites. J Immunol. 1997;159:6112–6119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin Y L, Chen L K, Liao C L, Yeh C T, Ma S H, Chen J L, Huang Y L, Chen S S, Chiang H Y. DNA immunization with Japanese encephalitis virus nonstructural protein NS1 elicits protective immunity in mice. J Virol. 1998;72:191–200. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.1.191-200.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin Y L, Liao C L, Yeh C T, Chang C H, Huang Y L, Huang Y Y, Jan J T, Chin C, Chen L K. A highly attenuated strain of Japanese encephalitis virus induces a protective immune response in mice. Virus Res. 1996;44:45–56. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(96)01343-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lobigs M, Arthur C E, Mullbacher A, Blanden R V. The flavivirus nonstructural protein NS3 is a dominant source of cytotoxic T cell peptide determinants. Virology. 1994;202:195–201. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mason P W, Dalrymple J M, Gentry M K, McCown J M, Hoke C H, Burke D S, Fournier M J, Mason T L. Molecular characterization of a neutralizing domain of the Japanese encephalitis virus structural glycoprotein. J Gen Virol. 1989;70:2037–2049. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-70-8-2037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mason P W, Pincus S, Fournier M J, Mason T L, Shope R E, Paoletti E. Japanese encephalitis virus-vaccinia recombinants produce particulate forms of the structural membrane proteins and induce high levels of protection against lethal JEV infection. Virology. 1991;180:294–305. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90034-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miura K, Onodera T, Nishida A, Goto N, Fujisaki Y. A single gene controls resistance to Japanese encephalitis virus in mice. Arch Virol. 1990;112:261–270. doi: 10.1007/BF01323170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Monath T P, Heinz F X. Flaviviruses. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, editors. Fields virology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1996. pp. 961–1034. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mosmann T R, Coffman R L. Heterogeneity of cytokine secretion patterns and functions of helper T cells. Adv Immunol. 1989;46:111–147. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60652-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pertmer T M, Eisenbraun M D, McCabe D, Prayaga S K, Fuller D H, Haynes J R. Gene gun-based nucleic acid immunization: elicitation of humoral and cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses following epidermal delivery of nanogram quantities of DNA. Vaccine. 1995;13:1427–1430. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(95)00069-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Phillpotts R J, Venugopal K, Brooks T. Immunisation with DNA polynucleotides protects mice against lethal challenge with St. Louis encephalitis virus. Arch Virol. 1996;141:743–749. doi: 10.1007/BF01718332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Porter K R, Kochel T J, Wu S J, Raviprakash K, Phillips I, Hayes C G. Protective efficacy of a dengue 2 DNA vaccine in mice and the effect of CpG immuno-stimulatory motifs on antibody responses. Arch Virol. 1998;143:997–1003. doi: 10.1007/s007050050348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schlesinger J J, Foltzer M, Chapman S. The Fc portion of antibody to yellow fever virus NS1 is a determinant of protection against YF encephalitis in mice. Virology. 1993;192:132–141. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sin J I, Kim J J, Ugen K E, Ciccarelli R B, Higgins T J, Weiner D B. Enhancement of protective humoral (Th2) and cell-mediated (Th1) immune responses against herpes simplex virus-2 through co-delivery of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor expression cassettes. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:3530–3540. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199811)28:11<3530::AID-IMMU3530>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Syrengelas A D, Chen T T, Levy R. DNA immunization induces protective immunity against B-cell lymphoma. Nat Med. 1996;2:1038–1041. doi: 10.1038/nm0996-1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Takegami T, Miyamoto H, Nakamura H, Yasui K. Biological activities of the structural proteins of Japanese encephalitis virus. Acta Virol. 1982;26:312–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tang D C, DeVit M, Johnston S A. Genetic immunization is a simple method for eliciting an immune response. Nature. 1992;356:152–154. doi: 10.1038/356152a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ulmer J B, Donnelly J J, Parker S E, Rhodes G H, Felgner P L, Dwarki V J, Gromkowski S H, Deck R R, DeWitt C M, Friedman A, Hawe L A, Leander K R, Martinez D, Perry H C, Shiver J W, Montgomery D L, Liu M A. Heterologous protection against influenza by injection of DNA encoding a viral protein. Science. 1993;259:1745–1749. doi: 10.1126/science.8456302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Venugopal K, Gould E A. Towards a new generation of flavivirus vaccines. Vaccine. 1994;12:966–975. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(94)90329-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wengler G, Wengler G. Cell-associated West Nile flavivirus is covered with E+pre-M protein heterodimers which are destroyed and reorganized by proteolytic cleavage during virus release. J Virol. 1989;63:2521–2526. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.6.2521-2526.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wu S C, Lian W C, Hsu L C, Liau M Y. Japanese encephalitis virus antigenic variants with characteristic differences in neutralization resistance and mouse virulence. Virus Res. 1997;51:173–181. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1702(97)00098-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xiang Z, Ertl H C. Manipulation of the immune response to a plasmid-encoded viral antigen by coinoculation with plasmids expressing cytokines. Immunity. 1995;2:129–135. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(95)80001-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xin Y Y, Ming Z G, Peng G Y, Jian A, Min L H. Safety of a live-attenuated Japanese encephalitis virus vaccine (SA14-14-2) for children. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1988;39:214–217. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1988.39.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]