Abstract

Faba bean necrotic yellows virus (FBNYV) belongs to the nanoviruses, plant viruses whose genome consists of multiple circular single-stranded DNA components. Eleven distinct DNAs, 5 of which encode different replication initiator (Rep) proteins, have been identified in two FBNYV isolates. Origin-specific DNA cleavage and nucleotidyl transfer activities were shown for Rep1 and Rep2 proteins in vitro, and their essential tyrosine residues that catalyze these reactions were identified by site-directed mutagenesis. In addition, we showed that Rep1 and Rep2 proteins hydrolyze ATP, and by changing the key lysine residue in the proteins’ nucleoside triphosphate binding sites, demonstrated that this ATPase activity is essential for multiplication of virus DNA in vivo. Each of the five FBNYV Rep proteins initiated replication of the DNA molecule by which it was encoded, but only Rep2 was able to initiate replication of all the six other genome components. Furthermore, of the five rep components, only the Rep2-encoding DNA was always detected in 55 FBNYV samples from eight countries. These data provide experimental evidence for a master replication protein encoded by a multicomponent single-stranded DNA virus.

Rolling-circle replication (RCR) of DNA appears particularly well suited for the multiplication of genetic information stored in the form of single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) (29). Genetic entities that multiply their DNA via RCR range from ssDNA plasmids of Archaebacteria (57) and Eubacteria (31, 82), ssDNA phages (e.g., φX174) (7), ssDNA viruses of plants (gemini- and nanoviruses) (19, 44, 52) to circoviruses and ssDNA viruses of birds (8, 62) and mammals (34, 60, 76). There is also a linear variant of RCR in the form of a rolling hairpin, a mechanism by which the single-stranded linear genome of parvoviruses is multiplied (11, 21). Common denominators of all these examples are specific replication initiator (Rep) proteins encoded by their own respective plasmid or the virus DNA and their interaction with a target sequence that, in many cases, may form a particular secondary structure, for instance, a hairpin (33, 36, 52, 54, 56).

Unlike the ssDNA plasmids, phages, and circoviruses, the genetic information of some geminiviruses is distributed over two DNAs, and that of the nanoviruses is distributed over at least six different DNAs. This creates the need for the Rep proteins to ensure multiplication of several different DNA molecules. In addition, the apparent redundancy of nanovirus DNAs encoding similar yet distinct Rep proteins raises questions about their respective specific roles in the replication process of the multiple component genome of the nanoviruses.

Nanoviruses (formerly referred to as “plant circoviruses”) have only recently been established as a separate genus of plant viruses with a genome consisting of multiple circular ssDNAs, each about 1 kb in size (67). Six to 11 different DNA components have so far been identified in the four assigned nanovirus species, such as the banana bunchy top virus (BBTV), faba bean necrotic yellows virus (FBNYV), milk vetch dwarf virus (MDV), and subterranean clover stunt virus (SCSV) (13, 14, 50, 70). With a single exception, each DNA appears to contain only one gene (9, 10). Each ssDNA is individually encapsidated into small isometric virions, and virus transmission is accomplished only by insects (aphids). The lack of an alternative experimental infection system has so far precluded the identification of the entire set of DNAs that represent the complete genome of a nanovirus.

In contrast, geminiviruses, the first ssDNA plant viruses described (30, 37), are well characterized in biological and molecular terms (12). They differ from the nanoviruses by their twin (geminate) particles, their genome organization, and insect vector (55). Geminivirus replication proteins bind specifically to double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) motifs in the origin region (1, 24, 26) and have a site-specific in vitro cleavage and joining activity on single-stranded oligonucleotides (40, 54) that represent part of the viral replication origin sequences (39, 64, 71). In addition, they possess an ATPase activity essential for virus replication (22, 35). The protein domains and amino acids responsible for the various activities of Rep proteins have been genetically or biochemically identified (18, 22, 42, 46, 53, 65, 66).

However, little is known about the molecular details of nanovirus replication. Minus-strand DNA synthesis of BBTV is primed by virion-associated primers (32), and a Rep protein was inferred to be encoded by one of the six BBTV genome components (36), based on the presence of amino acid motifs conserved among RCR initiator proteins (44). For this protein, a cleavage and joining activity of oligonucleotides corresponding to the inverted repeat sequence of the viral replication origin has been shown in vitro (33). A more complex picture emerged, however, when four further Rep-encoding DNAs (rep components) were identified from a Taiwanese isolate of BBTV (79, 80) and two and four rep components were described for the 7- and 10-component genomes of SCSV (13) and MDV (70), respectively.

For FBNYV, the object of this study, 11 distinct ssDNA components (C1 to C11) have been identified (48–50). Each of them encodes a single protein, such as the virus capsid protein (48), a cell cycle-link protein (4, 5), and four other proteins of as yet unknown function. C1, -2, -7, -9, and -11 encode different but closely related Rep proteins, each of about 33 kDa. The presence in two FBNYV isolates of five DNAs encoding distinct Rep proteins along with (at least) six DNAs encoding other viral proteins immediately raised two questions: whether all rep components are required and which of them are essential for the multiplication of the other genome components.

Here we describe the first biochemical and genetic analyses of FBNYV Rep1 and Rep2 protein activities along with the proof that each of five replication proteins is functional in vivo, i.e., supports autonomous replication of its coding component. Furthermore, we show that only one Rep protein, Rep2, has the capability and is sufficient to initiate in trans the replication of all other genome components of FBNYV that encode no Rep. This demonstrates the existence of a master replication protein in a multipartite ssDNA virus.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Clones of FBNYV DNAs.

The DNA sequences of the FBNYV-Sy isolate SV292-88 were previously described (48–50), and their EMBL/GenBank accession numbers are as follows: X80879 (C1), Y11405 to Y11409 (C2 to C6), and AJ005964 to AJ005967 (C7 to C10). C1 and C2 of this isolate are referred to here as C1-Sy and C2-Sy, respectively. Clones of C2 to C10 of the Egyptian isolate EV1-93 were obtained after PCR amplification by Pfu DNA polymerase by using primers designed to create unique restriction sites at the ends of the amplified DNA (see Tables 1 and 2 for details). In this way, all components, except C5 and C7, were cloned in the corresponding sites of pBluescript IISK(+) (Stratagene). To clone C5, two overlapping fragments were amplified by using the combination of the primer pairs P6 and P7 or P18 and P19 (Table 1). Both fragments were then digested with Asp718 and PvuII, ligated, cut by XbaI, and inserted into the XbaI site of pUC19 (81). Since for subsequent replication assays in plant tissue the binary vector pBin19 was used (28), the 1-kb amplification product of C7 had to be circularly permutated prior to insertion into pBin19. Therefore, the DNA was digested by PvuI, self-ligated, cut by HindIII, and inserted into the HindIII site of pUC19. Similarly, a clone of FBNYV C11 (FBNYV C1-Eg in reference 50), available as a PstI insertion in pUC19, was liberated by digestion with PstI, ligated, digested again by XbaI, and inserted into the XbaI site of pUC19.

TABLE 1.

Sequences of the primers used in this study

| Primer name | Sequence |

|---|---|

| C2HindIII(+) | ACGAAGCTTCGAGGAGTATGTTAATTACGG |

| C2HindIII(−) | TCGAAGCTTCGTGGAAAGTCGAAGAGCACT |

| C3EcoRI(+) | GTCTGAATTCGTTGAAGAGTCTTCTCC |

| C3EcoRI(−) | TCAACGAATTCAGACTTGTGTTCTTCA |

| C4BamHI(+) | AATACTGGATCCGTTTTTTGAATTTATGTATTG |

| C4BamHI(−) | TCAAAAAACGGATCCAGTATTAGGTTGACTTGC |

| C6PstI(+) | GAAGGCCTGCAGGACTTGTATGATTACGGT |

| C6PstI(−) | CAAGTCCTGCAGGCCTTCTGTATTTCTGAC |

| C7PvuI(+) | AGACGATCGAACAGGAACCAGATGACCGTA |

| C7PvuI(−) | GTTCGATCGTCTTCAACAATTCATCCTGCC |

| C8HindIII(+) | AACAAGCTTATGCTTTTAACGTTTATAAATAA GTTTCTCTT |

| C8HindIII(−) | CATAAGCTTGTTGGGCACGAAAGCATCTGC |

| C9PstI(+) | TGTCTGCAGTGAACTGGGTTTTCACGTTGA |

| C9PstI(−) | TCACTGCAGACATTCTCTCTCTTCTTTCTC |

| C10HincII(+) | ATTGTCAACTGCAGTGAATTGGATAAATTA |

| C10HincII(−) | GCAGTTGACAATCATACCGTCTTCGTATGT |

| P6 | CACTTCAACATAAACTCT |

| P7 | ATAGCCATTGGATTGTAA |

| P18 | ACTAACTCTCCAGGAGCCAT |

| P19 | CTTATTGTTAAATGTAATTCACCTAT |

| rep1-SalI | TAAAAAGTCGACTCAACAATTGATAAT |

| rep1-SphI | CATAAAGCATGCATGGCTTGTTCGAAT |

| rep2-SalI | GATCACGTCGACTCACGCATATACATA |

| rep2-SphI | ATTGAAGCATGCATGGCTCGGCAAGTT |

| rep1Y78F(+) | TCAGCTTTTGTTCAGAAAGAAGAAACTAGAGTT |

| rep1Y78F(−) | ACTCCAGGGACCTGCAACTCTAGTTTCTTCTTT CTGAACAAAAGCTGA |

| rep2Y79F(+) | GAAGCTAGGGCCTTTTCAATGAAAGAA |

| rep2Y79F(−) | TTCTTTCATTGAAAAGGCCCTAGCTTC |

| rep1K177A(+) | GGAGGAGAAGGCGCATCGATGTTC |

| rep1K177A(−) | GAACATCGATGCGCCTTCTCCTCC |

| rep2K187A(+) | GGCCCACAAGGTGGAGAAGGCGCAACCTCTTAC |

| rep2K187A(−) | GTAAGAGGTTGCGCCTTCTCCACCTT |

TABLE 2.

Cloning of FBNYV components

| FBNYV componenta | Cloning vector/site | Primers used for PCR amplification | Dimer obtained in vector/siteb | Dimer in Bin19 binary vector/siteb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1-Sy | pGEM-3Zf(+)/HindIII | Direct cloning | pUC19/HindIII | EcoRI-PvuII fragment from pUC19:C1-Sy-dimer inserted into Bin19 cut by EcoRI and SmaI |

| C2-Sy | pGEM-3Zf(+)/HindIII | Direct cloning | pUC19/HindIII | EcoRI-PvuII fragment from pUC19:C2-Sy-dimer inserted into Bin19 cut by EcoRI and SmaI |

| C2 | pBSKIIc/HindIII | C2HindIII(+), C2HindIII(−) | pBSKII/ApaI-EcoRI fragment from Bin19:C2-dimer | Direct repeat of C2 inserted into HindIII |

| C3 | pBSKII/EcoRI | C3EcoRI(+), C3EcoRI(−) | pBSKII/EcoRI | XbaI-KpnI fragment from pBSKII:C3-dimer |

| C4 | pBSKII/BamHI | C4BamHI(+), C4BamHI(−) | pBSKII/BamHI | XbaI-KpnI fragment from pBSKII:C4-dimer |

| C5 | pUC19/XbaI | P6+P7 and P18+P19 | pUC19/XbaI | BamHI-SalI fragment from pUC19:C5-dimer |

| C6 | pBSKII/PstI | C6PstI(+), C6PstI(−) | pBSKII/PstI | BamHI-SalI fragment from pUC19:C6-dimer |

| C7 | pUC19/HindIII | C7PvuI(+), C7PvuI(−) | pBSKII/ApaI-EcoRI fragment from Bin19:C7-dimer | Direct repeat of C7 inserted into HindIII |

| C8 | pBSKII/HindIII | C8HindIII(+), C8HindIII(−) | pBSKII/ApaI-EcoRI fragment from Bin19:C8-dimer | Direct repeat of C8 inserted into HindIII |

| C9 | pBSKII/PstI | C9PstI(+), C9PstI(−) | pBSKII/PstI | BamHI-EcoRI fragment from pBSKII:C9-dimer |

| C10 | pBSKII/HincII | C10HincII(+), C10HincII(−) | pBSKII/HincII | BamHI-KpnI fragment from pBSKII:C10-dimer |

| C11 | pUC19/XbaI | Direct cloning | pBSKII/EcoRI-SalI fragment from Bin19:C11-dimer | Direct repeat of C11 inserted into XbaI |

C1-Sy and C2-Sy were from the Syrian isolate SV292-88, and C2 to C11 were components from the Egyptian isolate EV1-93.

The DNA fragment was transferred into the plasmid digested by the corresponding endonucleases.

pBluescript IISK(+).

Rep expression in E. coli and protein purification.

Rep1 and Rep2 proteins were expressed in Escherichia coli with an N-terminal hexahistidine tag by using plasmid pQE30 (QIAGEN). DNA of C1-Sy and C2-Sy, cloned in the HindIII site of pGEM-3Zf(+), was released by HindIII and self-ligated, and the respective rep1 and rep2 genes were amplified by PCR with Pfu DNA polymerase and the following primer pairs: rep1 by using oligonucleotides rep1-SphI as the 5′-end primer and rep1-SalI as the 3′-end primer and rep2 by using oligonucleotides rep2-SphI as the 5′-end primer and rep2-SalI as the 3′-end primer (see Table 1 for details). The SphI and SalI restriction sites at the 5′ and 3′ ends of the amplified rep gene DNAs served for insertion into the corresponding sites of plasmid pQE30. The resulting plasmids, pQE30-rep1 and pQE30-rep2, were introduced into E. coli BL21(DE3)-recA (2, 75) harboring plasmid pRep4 (Qiagen) and expressing a high level of lac repressor to guarantee a tight control of protein synthesis. Bacteria were grown at 28°C in M9 minimal medium supplemented with 0.1% Casamino Acids, 2% glucose, and 0.1% thiamine, to an optical density at 600 nm of about 0.5, and induced by addition of 0.5 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside for 2 h. After centrifugation, the pellets were resuspended in 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 8.0) containing 300 mM NaCl and 10% glycerol (5 ml of buffer for the bacterial pellet from 250 ml of culture) and frozen. Bacteria were lysed for 30 min with lysozyme (0.5 mg/ml) in the presence of 0.5% Tween 20 and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride at 0°C, sonicated for 3 min, and further incubated for 30 min on ice with DNase and RNase (5 μg/ml). After clarification of the bacterial lysate by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 30 min, the supernatant was loaded onto a TALON (Clontech) metal affinity resin column (Co2+ as a chelating ion), and the Rep1 and Rep2 proteins were eluted with 250 mM imidazole. The two Rep proteins were sufficiently pure for all subsequent biochemical assays; the yield of Rep2 protein was consistently about 10 times higher than that of Rep1.

Site-directed mutagenesis of the rep1 and rep2 genes.

Mutagenesis to change tyrosine residues into phenylalanine (Y78 of Rep1 or Y79 of Rep2) and the lysine residues into alanine (K177 of Rep1 or K187 of Rep2) was performed with plasmids pBSKII:C1-Sy and pBSKII:C2-Sy or directly with expression plasmids pQE30-rep1 and pQE30-rep2 by applying the “Quik Change” site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). The primers rep1Y78F(+) and rep1Y78F(−) and rep2Y79F(+) and rep2Y79F(−) were used to change the respective tyrosine residues, and rep1K177A(+) and rep1K177A(−) and rep2K187A(+) and rep2K187A(−) were used to change the respective lysine residues.

DNA cleavage and nucleotidyl transfer assay.

Approximately 50 to 500 ng of Rep1 or Rep2 protein was incubated with 50 fmol of 32P-labeled (and nonlabeled) substrate DNA in a total volume of 20 μl for 20 min at 37°C in a reaction buffer containing 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 75 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM MnCl2, and 2.5 mM dithiothreitol. The reaction was stopped by adding 2 μl of 0.5 M EDTA, lyophilized, resuspended in formamide, and analyzed on 12% sequencing gels (68), which were then dried and autoradiographed.

ATPase assay.

About 100 ng of Rep1 or Rep2 protein was incubated at room temperature with 5 nM [γ-32P]ATP and various (5 to 50 μM) concentrations of nonlabeled ATP in a 10-μl reaction mixture containing 50 mM PIPES-NaOH (pH 7.0), 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, and 0.02% NP40. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 1 μl of 0.5 M EDTA. The reaction products were separated on thin-layer chromatography-polyethyleneimine cellulose (TLC-PEI) plates (Schleicher & Schuell) with 0.5 M LiCl–1 M formic acid as running buffer. The amount of 32Pi liberated was quantified with a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics).

Replication of FBNYV components in N. benthamiana.

For replication assays, redundant copies (direct repeats) of the FBNYV C1-Sy, C2-Sy, C3, C4, C5, C6, C9, and C10 were first constructed as dimers in pUC19 or pBluescript IISK(+) (Table 2). The redundant copies were released by using suitable restriction endonucleases (Table 2) and inserted into the binary vector pBin19, which contains a DNA fragment from the T region of Agrobacterium tumefaciens Ti plasmid (T-DNA) (41). Dimers of C2, -7, and -8, as well as of the mutated C1-Sy and C2-Sy (see the section above on site-directed mutagenesis), were directly assembled in the HindIII site of pBin19; a dimer of C11 in the XbaI site of pBin19 was obtained in the same way. Because of a severe toxicity of Rep9 protein in agrobacteria, the redundancy of C9 had to be reduced to 1.1. A 100-bp PvuII-ApoI fragment of C9 was treated with the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase I to obtain blunt ends prior to cloning in the AccI site of pBluescript IISK(+), which had been similarly filled in. The unique AccI site in the FBNYV DNA served to accept a full-length copy of C9 (liberated from pBSKII:C9 by digestion with PstI and circularly permuted by ligation and subsequent cleavage with AccI). The 1.1-mer of C9 was transferred as a BamHI-KpnI fragment into pBin19.

Viral DNA replication was assayed in leaf discs of Nicotiana benthamiana following agroinoculation. pBin19 derivatives carrying redundant copies of the respective FBNYV DNAs were transferred into A. tumefaciens LBA 4404 (41, 63) by electroporation (61). The agrobacteria were used to inoculate leaf discs of N. benthamiana as described previously (43). One week after inoculation, total DNA was isolated from the leaf tissue and fractionated on 1% agarose gels containing 0.3 μg of ethidium bromide per ml (1.5 V/cm in 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA buffer at 4°C). Viral DNA replicative forms were identified by Southern hybridization (68).

Dot blot hybridization assays for rep components in FBNYV samples from different countries.

The samples of FBNYV-infected legumes from Egypt, Ethiopia, Jordan, Morocco, and Syria, kept as desiccated leaf tissue at 4°C, were those described previously (27). In addition, FBNYV samples from virus surveys in Ethiopia, Pakistan, and Turkey in 1997 (kindly provided by K. M. Makkouk, ICARDA, Aleppo, Syria) and from Algeria (provided by Linda Allala, INA, El-Harrach, Algeria) were also included. Infection by FBNYV was determined by polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies to the virus in double- and triple-antibody sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (27). Fresh and dried samples extracted at 1:20 (wt/vol) and 1:200 (wt/vol), respectively, with 20× SSPE (3 M NaCl, 0.2 M Na2HPO4, 20 mM EDTA [pH 7.4]) were dotted as 100-μl aliquots onto positively charged nylon membranes (Boehringer Mannheim) by using a 96-well vacuum manifold (Gibco BRL). 32P-labeled rep component-specific probes (from nucleotide [nt] 598 to nt 929 for C1, 136 to 969 for C2, 67 to 814 for C7, 456 to 972 for C9, and 69 to 436 for C11) were prepared by PCR with primers derived from the respective coding regions and viral DNA of FBNYV-Sy, except for the C11 probe, for which FBNYV-Eg DNA served as template. Random-primed probe labeling with [α-32P]dCTP was carried out with the Megaprime kit (Amersham). Hybridization was conducted essentially as described in reference 68 by incubating the membranes at 42°C and washing the membranes at high stringency (0.1× SSPE and 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate at 65°C).

RESULTS

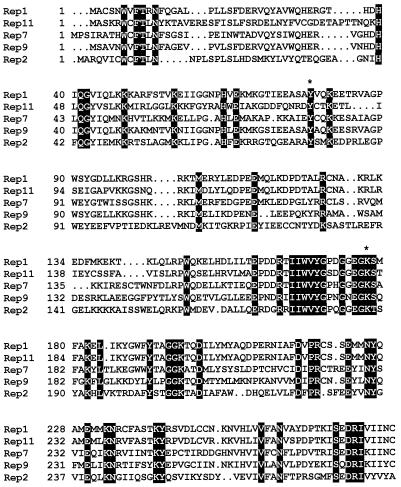

The FBNYV isolate SV292-88 from Syria (FBNYV-Sy), whose DNA sequence had been assembled mostly from partial clones and PCR-amplified DNA, is no longer available as an aphid-transmissible virus isolate. Therefore, full-sized genome components of an FBNYV isolate, EV1-93, from Egypt (FBNYV-Eg) that is serologically indistinguishable from FBNYV-Sy (27) and maintained by continuous insect transmission on fava bean (Vicia faba) were cloned, and their DNA sequences were determined (EMBL/GenBank accession no. AJ132179 to AJ132187 [C2 to C10] and AJ005968 [C11]). Whereas most of the components of both FBNYV isolates were very similar (>94% nucleotide identity), there was a striking difference in both coding (61% amino acid identity) and noncoding regions (68% nucleotide identity) between the rep1 component of FBNYV-Sy and its closest homologue in FBNYV-Eg (50). Therefore, the latter was designated C11. Furthermore, the encoded Rep protein (Rep11) turned out to be functionally distinct from Rep1 (see below). A sequence comparison of the five different Rep proteins encoded by the respective rep components (C1, C2, C7, C9, and C11) and the active site amino acids of Rep1 and Rep2 altered by site-directed mutagenesis are shown in Fig. 1.

FIG. 1.

Sequence comparison of FBNYV Rep proteins. Amino acid sequences of Rep1 (FBNYV-Sy) and Rep2, -7, -9, and -11 (FBNYV-Eg) were aligned by using PileUp of the UWGCG sequence analysis software package. Amino acids identical in all five Rep proteins are shown in black. Tyrosine and lysine residues that were altered by site-directed mutagenesis are marked by an asterisk (Y78 and K177 in Rep1 and Y79 and K187 in Rep2).

FBNYV DNAs encoding Rep proteins replicate autonomously.

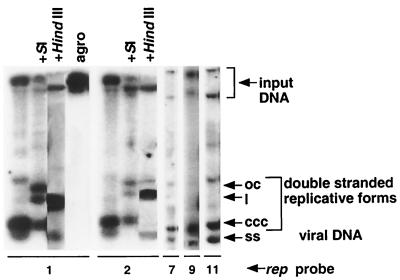

The association with FBNYV of five apparently distinct DNAs encoding putative Rep proteins raised the question of whether all of these Rep proteins were functional. Therefore, the capacity of each rep component to replicate autonomously in leaf discs of N. benthamiana was examined. Leaf discs were inoculated with agrobacteria carrying redundant copies of each of the five rep components (C1, C2, C7, C9, and C11) in the binary T-DNA vector pBin19. One week after agroinoculation, total DNA was isolated from the infected tissue and probed for replicative forms of viral DNA by Southern hybridization analyses (Fig. 2). The results indicated that each of the five rep components replicated autonomously, which means they expressed a functional Rep protein that acts on its cognate component to initiate DNA replication.

FIG. 2.

FBNYV DNAs encoding Rep proteins replicate autonomously in N. benthamiana. Southern hybridization of total DNA extracted from N. benthamiana leaf discs inoculated with agrobacteria carrying pBin19 with redundant copies of a respective FBNYV rep component indicated below each blot (rep1, rep2, rep7, and rep11 components were cloned as dimers, and rep9 was cloned as a 1.1-mer). Component-specific probes were used as indicated (rep probe). + S1, DNA was digested with nuclease S1 to digest the ssDNA; + HindIII, DNA was digested with HindIII to linearize rep1 or rep2 DNAs. agro, DNA extracted from agrobacteria used for inoculation. ss, ssDNA; ccc, covalently closed circular DNA; l, linear DNA; oc, open circular DNA. The DNA bands that migrate slower than double-stranded open circular DNA represent dimers and oligomers of replicative forms as they disappeared after digestion by HindIII.

FBNYV Rep1 and Rep2 proteins cleave origin DNA in vitro and have nucleotidyl transfer activity.

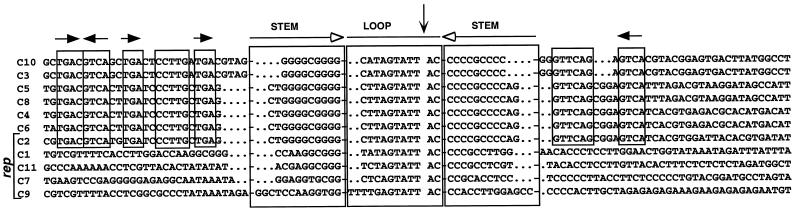

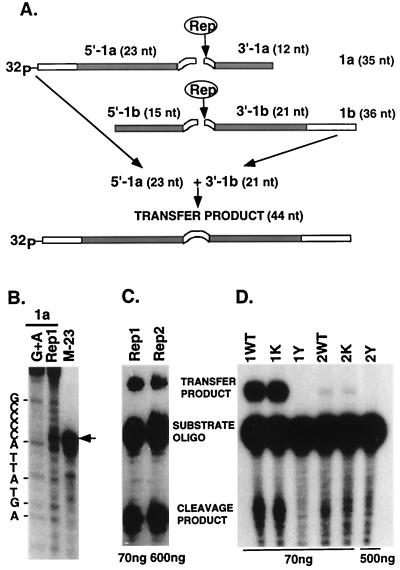

The noncoding region of all identified FBNYV DNA components contains GC-rich inverted repeats flanking a highly conserved AT-rich sequence of 11 nt (48) (Fig. 3), sequences that potentially form a stem-loop on ssDNA and are supposed to be part of the origin for initiation of RCR. To prove that the FBNYV Rep proteins possess origin DNA cleavage and nucleotidyl transfer activity, the Rep1 and Rep2 proteins were expressed in E. coli, purified, and used for in vitro assays. Oligonucleotides corresponding to the inverted repeat sequences in the ori regions of rep1 and rep2 components of FBNYV-Sy were used as substrates for the cleavage by purified Rep proteins. The precise position of the cleavage was determined by incubating a 5′-end-labeled ori1-specific oligonucleotide, 1a, with Rep1 protein. The results presented in Fig. 4B demonstrate that cleavage occurred between bases 7 and 8 of the consensus nonamer TAGTATT↓AC. The cleavage product migrated to the same position as a synthetic marker oligonucleotide with a 3′-OH, representing the 23-nt sequence from the 5′ end of the substrate to the presumed cleavage position. Both migrated slightly slower than the corresponding Maxam and Gilbert fragment carrying a phosphate at its 3′ end. Hence, we infer that the cleavage product has a free 3′ hydroxyl group. Figure 4A schematically illustrates the nucleotidyl transfer reaction. When 5′-labeled oligonucleotide 1a and nonlabeled oligonucleotide 1b were incubated with Rep1 or Rep2 protein, two labeled products appeared (Fig. 4C). These are the 5′ cleavage product of oligonucleotide 1a and a new recombinant oligonucleotide, corresponding to the joining of the labeled 5′ cleavage product of oligonucleotide 1a and the 3′ cleavage product of oligonucleotide 1b (transfer product). In addition, Fig. 4C illustrates that both Rep1 and Rep2 proteins cleave the ori1 substrate and that approximately 10-fold more Rep2 than Rep1 was required to obtain comparative amounts of reaction products. At the moment, we cannot be sure whether this difference reflects intrinsic features of the two proteins or whether it results from the strong overproduction of Rep2 and a concomitant partial inactivation of the protein due to aggregation or misfolding. Nevertheless, both Rep proteins showed similar in vitro DNA cleavage and nucleotidyl transfer efficiencies on sets of oligonucleotides corresponding to the replication origins of the rep1 and rep2 components, as well as on substrate oligonucleotides representing the tomato yellow leaf curl geminivirus (TYLCV) origin of replication (data not shown). The cleavage reaction was strictly dependent on the presence of divalent cations (2.5 mM Mg2+ or Mn2+). The addition of 10 μM ATP neither stimulated nor inhibited the reaction (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Comparison of the replication origin sequences of 11 FBNYV DNAs. The origin DNA sequences of 11 FBNYV components (C1 of FBNYV-Sy and C2 to C11 of FBNYV-Eg) are aligned. Inverted repeat sequences (open horizontal arrows) potentially forming a stem-loop are boxed. The vertical arrow indicates the position of cleavage by Rep protein. Conserved sequences shared by C2, C3, C4, C5, C6, C8, and C10 are indicated by small boxes, and the orientation of iteron-like sequence repeats is indicated by horizontal solid arrows. FBNYV component designations are on the left.

FIG. 4.

FBNYV Rep1 and Rep2 proteins possess in vitro cleavage and nucleotidyl transfer activities. (A) Scheme of the cleavage and nucleotidyl transfer reactions. The 5′ 32P-labeled oligonucleotide 1a (35 nt [TGGACCAAGGCGGGTATAGTATTACCCCGCCTTGG]) (underlined inverted repeat sequences are indicated in the figure by filled boxes) is cleaved by Rep protein giving rise to a 5′ 23-nt labeled and a 3′ 12-nt nonlabeled product. Analogously, nonlabeled oligonucleotide 1b (36 nt [GGCGGGTATAGTATTACCCCGCCTTGGAACACCCTC]) is cleaved to yield a 5′ product of 15 nt and a 3′ product of 21 nt. When both oligonucleotides 1a and 1b are treated simultaneously with Rep protein, their 5′ and 3′ cleavage products are joined, giving rise to the recombinant molecules of the nucleotidyl transfer reaction, the larger of which is 44 nt and carries the 5′ 32P label. (B) Identification of FBNYV origin cleavage position. The 5′ 32P-labeled oligonucleotide 1a was subjected to the G+A-specific chemical cleavage according to Maxam and Gilbert (58) or incubated with Rep1 protein. The fragment indicated by an arrow represents the Rep1-specific 5′-terminal cleavage product. M-23 (TGGACCAAGGCGGGTATAGTATT) is a 32P-labeled oligonucleotide identical to the 5′ cleavage product. (C) Separation of Rep-mediated DNA cleavage and nucleotidyl transfer products by denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. A mixture of labeled oligonucleotide 1a and nonlabeled oligonucleotide 1b was incubated with 70 ng of Rep1 or 600 ng of Rep2 protein. The products of the resulting cleavage and nucleotidyl transfer reactions are indicated. (D) Alteration of the catalytic tyrosine Y78F or Y79F abolishes cleavage and nucleotidyl transfer activity of the Rep1 or Rep2 proteins, respectively. Cleavage and nucleotidyl transfer reactions were performed with labeled oligonucleotide 1a and nonlabeled oligonucleotide 1b by using the following Rep proteins: 1WT and 2WT, wild-type Rep1 and Rep2 proteins; 1Y and 2Y, Rep1Y78F and Rep2Y79F proteins; 1K and 2K, Rep1K177A and Rep2K187A proteins, respectively. Since Rep2K187A protein was available in a limited amount, only 70 ng of wild-type Rep2 or Rep2K187A protein was used in this assay. Hence only faint bands represent cleavage and transfer products. To ensure that Rep2Y79F has no cleavage and nucleotidyl transfer activity, 500 ng of protein was used for this reaction. It is noteworthy that Rep2K187A has the same (low) specific cleavage and joining activities as wild-type Rep2 protein.

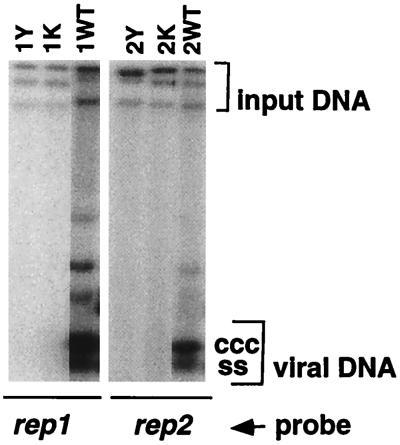

Sequence comparisons of Rep proteins of different nanoviruses, including FBNYV, reveal a putative active site tyrosine in a conserved amino acid environment (YxxK) similar to that of replication initiator proteins of bacteriophages, prokaryotic plasmids, and the Rep proteins of geminiviruses (44). To verify whether Y78 of Rep1 and Y79 of Rep2 of FBNYV (Fig. 1) are active site amino acids in the cleavage and nucleotidyl transfer reaction, their respective tyrosines were changed to phenylalanine by site-directed mutagenesis. Mutant Rep proteins were expressed, purified, and tested in vitro as described for the wild-type Rep proteins. Neither Rep1Y78F nor Rep2Y79F was active in cleavage and nucleotidyl transfer (Fig. 4D). In order to assess the effect of amino acid changes Y78F in Rep1 and Y79F in Rep2 proteins on the replication of their coding DNAs, we introduced the respective mutations into the corresponding rep1 and rep2 components and assayed their replication in N. benthamiana leaf discs. The results of a typical replication experiment are shown in Fig. 5. Mutant rep1 and rep2 components did not replicate, proving that tyrosine 78 of Rep1 and tyrosine 79 of Rep2 protein are essential for DNA replication in vivo.

FIG. 5.

Replication of mutated rep components in N. benthamiana leaf discs. Southern hybridization of total DNA extracted from N. benthamiana leaf discs, inoculated with agrobacteria carrying pBin19 with redundant copies of FBNYV rep components. 1WT and 2WT, wild-type rep1 and rep2 components, respectively (FBNYV-Sy); 1Y and 2Y, rep1 and rep2 components expressing Rep1Y78F and Rep2Y79F proteins, respectively; 1K and 2K, rep1 and rep2 components expressing Rep1K177A and Rep2K187A proteins, respectively. DNA forms are marked the same way as in Fig. 2.

FBNYV Rep1 and Rep2 proteins possess ATPase activity essential for DNA replication.

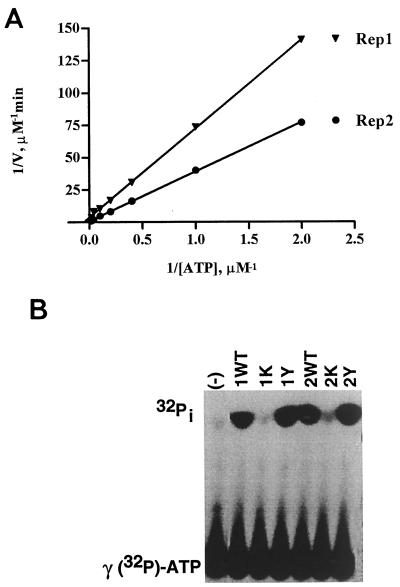

The deduced amino acid sequence of the FBNYV Rep proteins contains putative nucleoside triphosphate (NTP)-binding motifs GxxGxxGKT/S (see Fig. 1) that differ slightly from the canonical P-loop sequence GxxxxGKT/S (77). In order to determine whether the proteins possess ATPase activity, the hydrolysis of [γ-32P]ATP by purified Rep1 or Rep2 proteins was assayed. Both proteins were shown to possess ATPase activity with a Km in the micromolar range similar to that of TYLCV Rep protein (22). Km and Vmax values for ATP hydrolysis are shown in Fig. 6A. Rep2 protein was a more active ATPase than Rep1. The ATPase activity of both proteins was not stimulated by ssDNA (data not shown). When the lysine residues in the P-loop of the NTP binding site of Rep1 protein (K177) or Rep2 protein (K187) were altered by site-directed mutagenesis into alanine, the ATPase activities of both proteins dropped below the level of detection (Fig. 6B). However, the DNA cleavage and nucleotidyl transfer activity of the mutant Rep proteins was not influenced by the alterations in the P-loop (Fig. 4D).

FIG. 6.

FBNYV Rep1 and Rep2 proteins possess ATPase activity. About 100 ng of Rep1 or Rep2 protein was incubated at room temperature with 5 nM [γ-32P]ATP and various (5 to 50 μM) concentrations of nonlabeled ATP and incubated for 5 min (A). Assays of panel B were incubated for 20 min with 10 μM ATP as nonlabeled substrate; the resulting products were separated on TLC-PEI plates. (A) Determination of Km and Vmax for ATP hydrolysis. The amount of 32Pi liberated was calculated upon analysis of chromatograms with a PhosphorImager. The velocity of the reactions is measured as the amount of total ATP hydrolyzed per minute and is displayed in a double-reciprocal Lineweaver-Burk plot against the ATP concentration (1/[ATP]). The Km of Rep1 was 15 ± 5 μM, and the Vmax was 25 ± 10 nmol min−1 mg−1. The Km of Rep2 was 80 ± 10 μM and the Vmax was 150 ± 30 nmol min−1 mg−1. (B) Alteration of the conserved lysine in the P-loop abolishes ATPase activity of Rep1 and Rep2 proteins. Autoradiography of a chromatogram of ATP hydrolysis by the following proteins was done: 1WT and 2WT, wild-type Rep1 and Rep2, respectively; 1K and 2K, Rep1K177A and Rep2K187A proteins, respectively; 1Y and 2Y, Rep1Y78F and Rep2Y79F proteins, respectively. (−), no protein added.

The mutations leading to the expression of Rep proteins with an altered P-loop (K177A in Rep1 and K187A in Rep2) were also introduced into the full-length rep1 and rep2 DNAs by site-directed mutagenesis, and their replication was assayed. The results shown in Fig. 5 demonstrate that mutant rep1 and rep2 components do not replicate, indicating that the Rep-associated ATPase is required for DNA replication in vivo.

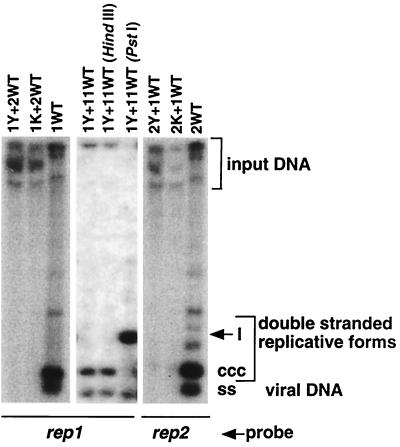

Rep1 and Rep2 proteins do not functionally cross-complement.

Since Rep2 protein in vitro cleaved oligonucleotides corresponding to the rep1 component origin (Fig. 4) and vice versa (data not shown), we determined whether a given Rep protein also initiates in trans the replication of a heterologous rep component. We used a mixture of two Agrobacterium strains, one carrying a mutated rep1 component (Y78F or K177A) and the other carrying a wild-type rep2 component, and vice versa, to inoculate N. benthamiana leaf discs. Total DNA was isolated 7 days after inoculation and probed for replication of the respective rep components by Southern hybridization. As is evident from Fig. 7, Rep1 protein could not replace a mutant Rep2 to initiate replication and, conversely, Rep2 protein could not substitute for a mutant Rep1. Moreover, rep11 also failed to complement a mutated rep1 component, indicating that the two Rep proteins are functionally distinct.

FIG. 7.

Complementation assays with combinations of wild-type and mutant FBNYV rep components. Different pairs of agrobacteria carrying pBin19 with redundant copies of wild-type and mutant rep1 and rep2 components (FBNYV-Sy) or rep11 were used to coinoculate N. benthamiana leaf discs. The designations of the respective mutant rep components are as in Fig. 5. The blots were hybridized with probes specific for rep1 and rep2 components as indicated. Because rep11 shares sequence identity with the rep1 probe, total DNA was treated prior to electrophoresis with HindIII or PstI, which specifically linearized either rep1 or rep11 DNA, respectively. The appearance of a linear fragment upon PstI treatment proves that only rep11 DNA replicated when coinoculated with the mutant (Y78F) rep1 component.

Only FBNYV Rep2 protein triggers replication of other viral genome components and only rep2 DNA is always associated with different virus isolates.

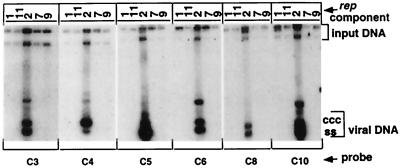

Sequence comparison of the noncoding regions of 11 FBNYV DNAs revealed conserved sequences of about 70 nt shared by rep2 and all DNAs encoding proteins other than Rep (non-rep components) (Fig. 3). Apart from the inverted repeat sequence, there is only limited similarity in the origin region between the rep2 component and the other rep components. This observation suggested that Rep2 protein might specifically recognize targets in the origin sequences common to all FBNYV DNAs except the rep1, -7, -9, and -11 components. To verify this hypothesis, we tested whether replication of the non-rep components of FBNYV could be initiated in trans by coinoculating each of them in pairwise mixtures with one of the five rep components to N. benthamiana leaf discs. Agroinoculation of the various combinations of DNAs to be tested, DNA extraction, and probing for replication by Southern hybridization were done as described above. Figure 8 shows the summary of a series of replication assays. Only when coinoculated with agrobacteria carrying the rep2 component, was replication of each of the six other FBNYV components observed. Coinoculations with each of the four other rep components did not lead to replication of any non-rep DNA. This proves that only Rep2 protein catalyzes the initiation of DNA replication of all FBNYV genome components that encode viral proteins other than Rep. Therefore, Rep2 is the master Rep protein of FBNYV.

FIG. 8.

Rep2 protein mediates replication of other (non-rep) FBNYV components. Shown are Southern blots of DNAs extracted from leaf discs coinoculated with pairwise combinations of agrobacteria carrying the respective FBNYV DNA to be assayed for replication (indicated at the bottom) and agrobacteria carrying the respective rep component (indicated at the top). All DNAs, except C1-Sy, are from FBNYV-Eg. Membranes were hybridized with probes specific for the components indicated below each blot.

The identification of five distinct rep components from two geographical isolates of FBNYV (50) raised the question as to what extent these rep components are associated with other isolates of FBNYV. Therefore, 55 FBNYV samples from Algeria, Egypt, Ethiopia, Jordan, Morocco, Pakistan, Syria, and Turkey were analyzed by dot-blot hybridization with probes specific for each of the five rep components. As a result (Table 3), only a rep2-like component was detected in every sample. Variable combinations of rep1-, rep7-, rep9-, and rep11-like components were found in 33 samples, whereas 22 samples did not contain any of them. Hence, this analysis corroborates the results of the replication assays obtained with the cloned DNAs and supports the finding that rep2 encodes the master Rep protein of FBNYV.

TABLE 3.

Dot hybridization reactions of 55 FBNYV-infected samples from eight countries

| Country | No. of samplesa | Result with probe specific to rep componentb:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1c | C2 | C7 | C9 | C11 | ||

| Algeria | 5 | + | ++ | ++ | − | − |

| Egypt | 1 | − | + | − | + | ++ |

| 1 | − | ++ | − | ++ | ++ | |

| 1 | − | ++ | − | − | − | |

| 1 | − | ++ | − | − | ++ | |

| 1 | − | ++ | ++ | + | − | |

| 2 | − | ++ | − | ++ | − | |

| Ethiopia | 9 | − | ++ | − | − | − |

| 2 | − | ++ | − | + | − | |

| Jordan | 3 | ++ | ++ | − | − | − |

| 4 | − | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | |

| 1 | − | ++ | − | − | − | |

| 2 | − | ++ | − | ++ | − | |

| 1 | − | ++ | − | ++ | ++ | |

| Morocco | 5 | − | ++ | − | − | − |

| 1 | − | + | − | − | − | |

| Pakistan | 1 | − | ++ | + | − | − |

| 1 | − | + | + | + | + | |

| Syria | 1 | − | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| 2 | + | ++ | − | − | ++ | |

| 1 | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | + | |

| 2 | − | ++ | − | ++ | ++ | |

| 5 | − | ++ | − | − | − | |

| Turkey | 2 | − | ++ | ++ | − | − |

| Controls | ||||||

| FBNYV-Sy (SV292-88) | ++ | ++ | + | + | − | |

| FBNYV-Eg (EV1-93) | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | |

Number of samples giving similar reaction patterns.

Hybridization reactions were classed as − (none), + (weak), and ++ (intermediate to strong).

The 332-bp rep1-specific probe had 85% identity with the rep11 DNA. This may explain the slight cross-hybridization with FBNYV-Eg (EV1-93), a sample in which rep1 DNA of FBNYV-Sy is definitely not present (50). However, the absence of a hybridization signal when using the rep1 probe, as is the case for other samples that clearly hybridized with the rep11 probe, may reflect a higher degree of sequence divergence between the rep1 probe and rep11-like DNA molecules present in the respective samples.

DISCUSSION

All FBNYV rep components encode functional replication initiator proteins.

The recent characterization of the nanoviruses FBNYV and MDV has led to the identification of the largest number of different DNA components among the nanoviruses and, most strikingly, of four (MDV) and five (FBNYV) different DNAs that potentially code for replication initiator proteins (50, 70) (Fig. 1). This prompted us to study whether all five FBNYV rep components encode functional Rep proteins and, if so, which of these Rep proteins supports replication initiation of the other genome components. Here, we have shown that, in fact, all rep components direct the synthesis of functional replication initiator proteins capable of triggering the autonomous replication of their respective DNA component in plant cells (Fig. 2). Moreover, the formation of ssDNA indicates that nanoviruses, here represented by FBNYV, also replicate via a rolling-circle mechanism.

The enzymatic properties of at least two FBNYV Rep proteins, Rep1 and Rep2, resemble in some respects those of the geminivirus Rep proteins (12, 52). The finding that both Rep1 and Rep2 proteins possess an origin-specific DNA cleavage and nucleotidyl transfer activities and that a conserved tyrosine (Y78 of Rep1 and Y79 of Rep2) is essential for these reactions (Fig. 4 and 5) underline this similarity. Similar origin cleavage and nucleotidyl transfer activities have been reported for Rep protein of another nanovirus, BBTV, but active site amino acids were not identified (33).

Whereas the role of these Rep activities for virus replication is evident, the biological significance of the second common feature, the ATPase activity of the nanovirus and geminivirus Rep proteins, remains elusive. We have shown that in vitro ssDNA origin cleavage and joining activity of FBNYV Rep1 and Rep2 proteins requires no ATP (Fig. 4D); however, their ATPase function is required for viral DNA replication in vivo (Fig. 5), similar to the geminivirus Rep proteins (22, 35, 40, 54, 65). Replication initiator proteins of some animal viruses, such as Rep proteins of parvoviruses and large T-antigen of simian virus 40 (SV40) and other polyomaviruses, are also helicases that require ATP hydrolysis for the unwinding of dsDNA (45, 73), and, consequently, mutants with mutations in their NTP-binding site are defective in viral replication (6, 16, 21, 38, 59). Whether in gemini- and nanovirus Rep proteins as well the ATPase is part of a helicase function remains unknown.

The controlled formation of hexameric complexes in an ATP-dependent manner is a common feature of animal virus replication initiator proteins: for instance, the AAV Rep78 or SV40 large T-antigen (15, 72). Moreover, formation of multiprotein complexes consisting of replication-associated proteins and other host or viral proteins is a general prerequisite for origin recognition prior to replication initiation. Examples are represented by the interaction of SV40 large T-antigen with replication protein A and DNA polymerase α-primase (78), by association of AAV Rep78 with high-mobility-group protein HMG1 (20), or by the papillomavirus E1 protein interaction with E2 (69). For the latter, ATP modulates this interaction, and it appears to be an attractive hypothesis that the ATPase associated with the nano- and geminivirus Rep proteins may play a comparable role in the replication of these plant viruses.

Nanovirus replication is triggered by a master Rep protein.

One of the key steps during the initiation of DNA replication is origin recognition (51). Geminivirus Rep proteins specifically recognize the origin of their cognate genome and do not initiate DNA replication of other geminivirus genomes, as has been shown for two different geminiviruses with a single genomic DNA, TYLCV (46) and beet curly top virus (BCTV) (18, 74). Such recognition specificity is particularly relevant for the geminiviruses with a bipartite genome. Their two genomic DNAs (DNA-A and -B) share a common region that contains the replication origin and multiple Rep protein binding sites. The binding sites are recognized by a given Rep protein and have been mapped to a 13-bp element containing 5-bp direct repeats (iterons) for tomato golden mosaic virus (24) and BCTV (17, 74). The iterons have to be identical on a given pair of DNA-A and -B to warrant correct replication initiation and multiplication of both DNAs (25); they differ, however, among different geminiviruses (1, 3, 74).

Here, we have demonstrated the same for a nanovirus: wild-type Rep1 protein of FBNYV could not substitute for a mutated Rep2 protein to initiate replication of rep2 DNA and vice versa, which is entirely in line with the specificity requirements of origin recognition by a given Rep protein (Fig. 7). The concept of a modular arrangement of specificity elements and a common initiation signal, recognized and acted on by Rep proteins in a two-step process, is easily transferable from the bipartite genome of some geminiviruses to the multipartite genome of the nanoviruses. As long as a nanovirus genome component contains a specific signal recognized by a given Rep protein, that particular Rep protein initiates its multiplication. This is exactly what we observed in replication assays, when we pairwise combined each of the six FBNYV DNAs coding for proteins other than a Rep with one of the five different rep components: only Rep2 initiated the replication of all non-rep components in addition to its cognate DNA (Fig. 8). None of the other Rep proteins was able to trigger replication of any DNA other than its cognate. The observation that DNA sequence motifs flanking the conserved inverted repeat element are shared by rep2 and the other six genome components, whose replication depends on the action of Rep2 protein (Fig. 3), further suggests that such common sequences may contain specificity elements of Rep2 recognition.

These molecular genetic findings were further supported by the results of the hybridization analysis of 55 FBNYV samples from eight countries with rep component-specific probes (Table 3). Only a rep2 component was detected in all samples, thus providing independent evidence for this DNA encoding a master Rep protein. Comparably, a single Rep-encoding DNA (DNA-1) was found in BBTV isolates from 10 countries (47). Remarkably, of all nanovirus Rep proteins, Rep1 of BBTV is most similar (55% amino acid identity) to Rep2 of FBNYV (50). In contrast, rep1, -7, -9, and -11 components were frequently detected in various combinations in the 55 samples and were even absent from an appreciable number of FBNYV-infected samples. No pattern of geographic distribution could be associated with the presence or absence of one or more of these rep components; the erratic distribution of the rep1, -7, -9, and -11 components in the geographically diverse FBNYV samples rather suggests that they may not be integral parts of the FBNYV genome. Because in addition to being autonomously replicating satellites, depending for various functions (e.g., encapsidation into virus particles and dissemination by insects) on FBNYV, no information concerning their influence on disease symptoms is as yet available, it remains unknown if they are defective interfering molecules. An interesting example of a DNA satellite has recently been described for tomato leaf curl virus (TLCV), a monopartite geminivirus (23). Unlike the FBNYV rep components, the TLCV satellite DNA carries only a replication origin and depends for multiplication on the Rep protein of its helper virus, and it has no obvious phenotypic effect on infection.

The intriguing question about the significance of rep DNAs that, in addition to a master Rep-encoding DNA, are frequently associated with FBNYV and other nanoviruses, will only be answered by the experimental reproduction of the full biological infection cycle of a nanovirus by using infectious cloned copies of the complete genomic DNA. The challenge to fulfill Koch’s postulates for any nanovirus remains open.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank L. Allala (INA, El-Harrach, Algeria) and K. M. Makkouk (ICARDA, Aleppo, Syria) for supplying FBNYV samples, L. Troussard for DNA sequencing, and J. Leung for critical comments on the manuscript. T. Timchenko is grateful to the Institute of Cytology and Genetics, Russian Academy of Sciences, Novosibirsk, for granting her a leave of absence.

This work was supported by the European Commission under the INCO-DC Programme (ERBIC18-CT96-0121).

REFERENCES

- 1.Akbar Behjatnia S A, Dry I B, Ali Rezaian M. Identification of the replication-associated protein binding domain within the intergenic region of tomato leaf curl geminivirus. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:925–931. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.4.925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angulo J F, Rouer E, Mazin A, Mattei M G, Tissier A, Horellou P, Benarous R, Devoret R. Identification and expression of the cDNA of KIN17, a zinc-finger gene located on mouse chromosome 2, encoding a new DNA-binding protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:5117–5123. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.19.5117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Argüello-Astorga G R, Guevara-Gonzalez R G, Herrera-Estrella L R, Rivera-Bustamante R F. Geminivirus replication origins have a group-specific organization of iterative elements: a model for replication. Virology. 1994;203:90–100. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aronson M, Timchenko T, Meyer A, de Kouchkovsky F, Katul L, Vetten H-J, Gronenborn B. Proceedings of the Fifth McGill University International Conference on Regulation of Eukaryotic DNA Replication. Quebec, Canada: St. Sauveur; 1998. CLINK, a cell cycle link protein from ssDNA plant virus; p. 56. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aronson, M. N., A. D. Meyer, J. Györgyey, L. Katul, H. J. Vetten, B. Gronenborn, and T. Timchenko. Clink, a nanovirus encoded protein binds both pRB and SKP1. Submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Auborn K, Guo M, Prives C. Helicase, DNA-binding, and immunological properties of replication-defective simian virus 40 mutant T antigens. J Virol. 1989;63:912–918. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.2.912-918.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baas P D, Jansz H S. Single-stranded DNA phage origins. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1988;136:31–70. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-73115-0_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bassami M R, Berryman D, Wilcox G E, Raidal S R. Psittacine beak and feather disease virus nucleotide sequence analysis and its relationship to porcine circovirus, plant circoviruses, and chicken anaemia virus. Virology. 1998;249:453–459. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beetham P R, Hafner G J, Harding R M, Dale J L. Two mRNAs are transcribed from banana bunchy top virus DNA-1. J Gen Virol. 1997;78:229–236. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-1-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beetham P R, Harding R M, Dale J L. Banana bunchy top virus DNA-2 to 6 are monocistronic. Arch Virol. 1999;144:89–105. doi: 10.1007/s007050050487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berns K I. Parvovirus replication. Microbiol Rev. 1990;54:316–329. doi: 10.1128/mr.54.3.316-329.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bisaro D M. Geminivirus DNA replication. In: DePamphilis M L, editor. DNA replication in eukaryotic cells. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1996. pp. 833–854. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boevink P, Chu P W, Keese P. Sequence of subterranean clover stunt virus DNA: affinities with the geminiviruses. Virology. 1995;207:354–361. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burns T M, Harding R M, Dale J L. The genome organization of banana bunchy top virus: analysis of six ssDNA components. J Gen Virol. 1995;76:1471–1482. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-76-6-1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Castellino A M, Cantalupo P, Marks I M, Vartikar J V, Peden K W C, Pipas J M. trans-Dominant and non-trans-dominant mutant simian virus 40 large T antigens show distinct responses to ATP. J Virol. 1997;71:7549–7559. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.10.7549-7559.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chejanovsky N, Carter B J. Mutation of a consensus purine nucleotide binding site in the adeno-associated virus rep gene generates a dominant negative phenotype for DNA replication. J Virol. 1990;64:1764–1770. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.4.1764-1770.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choi I R, Stenger D C. The strain-specific cis-acting element of beet curly top geminivirus DNA replication maps to the directly repeated motif of the ori. Virology. 1996;226:122–126. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choi I R, Stenger D C. Strain-specific determinants of beet curly top geminivirus DNA replication. Virology. 1995;206:904–912. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chu P W G, Boevink P, Surin B, Larkin P, Keese P, Waterhouse P M. Non-geminated single-stranded DNA plant viruses. In: Singh R P, Singh U S, Kohmoto K, editors. Pathogenesis and host specificity in plant diseases. III. Viruses and viroids. Elmsford, N.Y: Pergamon Press; 1995. pp. 311–341. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Costello E, Saudan P, Winocour E, Pizer L, Beard P. High mobility group chromosomal protein 1 binds to the adeno-associated virus replication protein (Rep) and promotes Rep-mediated site-specific cleavage of DNA, ATPase activity and transcriptional repression. EMBO J. 1997;16:5943–5954. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.19.5943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cotmore S E, Tattersall P. Parvovirus DNA replication. In: DePamphilis M L, editor. DNA replication in eukaryotic cells. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1996. pp. 799–813. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Desbiez C, David C, Mettouchi A, Laufs J, Gronenborn B. Rep protein of tomato yellow leaf curl geminivirus has an ATPase activity required for viral DNA replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:5640–5644. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.12.5640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dry I B, Krake L R, Rigden J E, Rezaian M A. A novel subviral agent associated with a geminivirus: the first report of a DNA satellite. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:7088–7093. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.13.7088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fontes E P, Eagle P A, Sipe P S, Luckow V A, Hanley-Bowdoin L. Interaction between a geminivirus replication protein and origin DNA is essential for viral replication. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:8459–8465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fontes E P, Gladfelter H J, Schaffer R L, Petty I T, Hanley-Bowdoin L. Geminivirus replication origins have a modular organization. Plant Cell. 1994;6:405–416. doi: 10.1105/tpc.6.3.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fontes E P, Luckow V A, Hanley-Bowdoin L. A geminivirus replication protein is a sequence-specific DNA binding protein. Plant Cell. 1992;4:597–608. doi: 10.1105/tpc.4.5.597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Franz A, Makkouk K M, Katul L, Vetten H J. Monoclonal antibodies for the detection and differentiation of faba bean necrotic yellows virus isolates. Ann Appl Biol. 1996;128:255–268. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frisch D A, Harris-Haller L W, Yokubaitis N T, Thomas T L, Hardin S H, Hall T C. Complete sequence of the binary vector Bin 19. Plant Mol Biol. 1995;27:405–409. doi: 10.1007/BF00020193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gilbert W, Dressler D. DNA replication: the rolling circle model. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol. 1968;33:473–484. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1968.033.01.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goodman R M. Infectious DNA from a whitefly-transmitted virus of Phaseolus vulgaris. Nature. 1977;266:54–55. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gruss A, Ehrlich S D. The family of highly interrelated single-stranded deoxyribonucleic acid plasmids. Microbiol Rev. 1989;53:231–241. doi: 10.1128/mr.53.2.231-241.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hafner G J, Harding R M, Dale J L. A DNA primer associated with banana bunchy top virus. J Gen Virol. 1997;78:479–486. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-2-479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hafner G J, Stafford M R, Wolter L C, Harding R M, Dale J L. Nicking and joining activity of banana bunchy top virus replication protein in vitro. J Gen Virol. 1997;78:1795–1799. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-7-1795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hamel A L, Lin L L, Nayar G P S. Nucleotide sequence of porcine circovirus associated with postweaning multisystemic wasting syndrome in pigs. J Virol. 1998;72:5262–5267. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.6.5262-5267.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hanson S F, Hoogstraten R A, Ahlquist P, Gilbertson R L, Russell D R, Maxwell D P. Mutational analysis of a putative NTP-binding domain in the replication-associated protein (AC1) of bean golden mosaic geminivirus. Virology. 1995;211:1–9. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harding R M, Burns T M, Hafner G, Dietzgen R G, Dale J L. Nucleotide sequence of one component of the banana bunchy top virus genome contains a putative replicase gene. J Gen Virol. 1993;74:323–328. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-74-3-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harrison B D, Barker H, Bock K R, Guthrie E J, Meredith G, Atkinson M. Plant viruses with circular single-stranded DNA. Nature. 1977;270:760–762. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hassel B A, Brinton B T. SV40 and polyomavirus DNA replication. In: DePamphilis M L, editor. DNA replication in eukaryotic cells. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1996. pp. 639–677. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heyraud F, Matzeit V, Schaefer S, Schell J, Gronenborn B. The conserved nonanucleotide motif of the geminivirus stem-loop sequence promotes replicational release of virus molecules from redundant copies. Biochimie. 1993;75:605–615. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(93)90067-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Heyraud-Nitschke F, Schumacher S, Laufs J, Schaefer S, Schell J, Gronenborn B. Determination of the origin cleavage and joining domain of geminivirus Rep proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:910–916. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.6.910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hoekema A, Hirsch P R, Hooykaas P J J, Schilperoort R A. A binary plant vector strategy based on separation of vir- and T-region of Agrobacterium tumefaciens Ti-plasmid. Nature. 1983;303:179–180. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hoogstraten R A, Hanson S F, Maxwell D P. Mutational analysis of the putative nicking motif in the replication-associated protein (AC1) of bean golden mosaic geminivirus. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1996;9:594–599. doi: 10.1094/mpmi-9-0594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Horsch R B, Rogers S G, Fraley R T. Transgenic plants. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol. 1985;50:433–437. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1985.050.01.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ilyina T V, Koonin E V. Conserved sequence motifs in the initiator proteins for rolling circle DNA replication encoded by diverse replicons from eubacteria, eucaryotes and archaebacteria. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:3279–3285. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.13.3279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Im D S, Muzyczka N. The AAV origin binding protein Rep68 is an ATP-dependent site-specific endonuclease with DNA helicase activity. Cell. 1990;61:447–457. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90526-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jupin I, Hericourt F, Benz B, Gronenborn B. DNA replication specificity of TYLCV geminivirus is mediated by the amino-terminal 116 amino acids of the Rep protein. FEBS Lett. 1995;362:116–120. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00221-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Karan M, Harding R M, Dale J L. Evidence for two groups of banana bunchy top virus isolates. J Gen Virol. 1994;75:3541–3546. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-75-12-3541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Katul L, Maiss E, Morozov S Y, Vetten H J. Analysis of six DNA components of the faba bean necrotic yellows virus genome and their structural affinity to related plant virus genomes. Virology. 1997;233:247–259. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Katul L, Maiss E, Vetten H J. Sequence analysis of a faba bean necrotic yellows virus DNA component containing a putative replicase gene. J Gen Virol. 1995;76:475–479. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-76-2-475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Katul L, Timchenko T, Gronenborn B, Vetten H J. Ten distinct circular ssDNA components, four of which encode putative replication-associated proteins, are associated with the faba bean necrotic yellows virus genome. J Gen Virol. 1998;79:3101–3109. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-79-12-3101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kornberg A, Baker T A. DNA replication. 2nd ed. New York, N.Y: W. H. Freeman; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Laufs J, Jupin I, David C, Schumacher S, Heyraud-Nitschke F, Gronenborn B. Geminivirus replication: genetic and biochemical characterization of Rep protein function, a review. Biochimie. 1995;77:765–773. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(96)88194-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Laufs J, Schumacher S, Geisler N, Jupin I, Gronenborn B. Identification of the nicking tyrosine of geminivirus Rep protein. FEBS Lett. 1995;377:258–262. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)01355-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Laufs J, Traut W, Heyraud F, Matzeit V, Rogers S G, Schell J, Gronenborn B. In vitro cleavage and joining at the viral origin of replication by the replication initiator protein of tomato yellow leaf curl virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:3879–3883. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.9.3879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lazarowitz S G. Geminiviruses: genome structure and function. Crit Rev Plant Sci. 1992;11:327–349. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mankertz A, Mankertz J, Wolf K, Buhk H J. Identification of a protein essential for replication of porcine circovirus. J Gen Virol. 1998;79:381–384. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-79-2-381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Marsin S, Forterre P. A rolling circle replication initiator protein with a nucleotidyl-transferase activity encoded by the plasmid pGT5 from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus abyssi. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:1183–1192. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00759.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Maxam A M, Gilbert W. Sequencing end-labeled DNA with base-specific chemical cleavages. Methods Enzymol. 1980;65:499–560. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(80)65059-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McCarty D M, Ni T-H, Muzyczka N. Analysis of mutations in adeno-associated virus Rep protein in vivo and in vitro. J Virol. 1992;66:4050–4057. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.7.4050-4057.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Meehan B M, Creelan J L, McNulty M S, Todd D. Sequence of porcine circovirus DNA: affinities with plant circoviruses. J Gen Virol. 1997;78:221–227. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-1-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mozo T, Hooykaas P J. Electroporation of megaplasmids into Agrobacterium. Plant Mol Biol. 1991;16:917–918. doi: 10.1007/BF00015085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Niagro F D, Forsthoefel A N, Lawther R P, Kamalanathan L, Ritchie B W, Latimer K S, Lukert P D. Beak and feather disease virus and porcine circovirus genomes: intermediates between the geminiviruses and plant circoviruses. Arch Virol. 1998;143:1723–1744. doi: 10.1007/s007050050412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ooms G, Hooykaas P J, Van Veen R J, Van Beelen P, Regensburg-Tuink T J, Schilperoort R A. Octopine Ti-plasmid deletion mutants of Agrobacterium tumefaciens with emphasis on the right side of the T-region. Plasmid. 1982;7:15–29. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(82)90023-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Orozco B M, Gladfelter H J, Settlage S B, Eagle P A, Gentry R N, Hanley-Bowdoin L. Multiple cis elements contribute to geminivirus origin function. Virology. 1998;242:346–356. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.9013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Orozco B M, Hanley-Bowdoin L. Conserved sequence and structural motifs contribute to the DNA binding and cleavage activities of a geminivirus replication protein. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:24448–24456. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.38.24448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Orozco B M, Miller A B, Settlage S B, Hanley-Bowdoin L. Functional domains of a geminivirus replication protein. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:9840–9846. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.15.9840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pringle C R. Virus taxonomy—San Diego 1998. Arch Virol. 1998;143:1449–1459. doi: 10.1007/s007050050389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sanders C M, Stenlund A. Recruitment and loading of the E1 initiator protein: an ATP-dependent process catalysed by a transcription factor. EMBO J. 1998;17:7044–7055. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.23.7044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sano Y, Wada M, Hashimoto Y, Matsumoto T, Kojima M. Sequences of ten circular ssDNA components associated with the milk vetch dwarf virus genome. J Gen Virol. 1998;79:3111–3118. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-79-12-3111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sanz-Burgos A P, Gutiérrez C. Organization of the cis-acting element required for wheat dwarf geminivirus DNA replication and visualization of a Rep protein-DNA complex. Virology. 1998;243:119–129. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Smith R H, Spano A J, Kotin R M. The Rep78 gene product of adeno-associated virus (AAV) self-associates to form a hexameric complex in the presence of AAV ori sequences. J Virol. 1997;71:4461–4471. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.6.4461-4471.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Stahl H, Droge P, Knippers R. DNA helicase activity of SV40 large tumor antigen. EMBO J. 1986;5:1939–1944. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04447.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Stenger D C. Replication specificity elements of the Worland strain of beet curly top virus are compatible with those of the CFH strain but not those of the Cal/Logan strain. Phytopathology. 1998;88:1174–1178. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO.1998.88.11.1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Studier F W, Rosenberg A H, Dunn J J, Dubendorff J W. Use of T7 RNA polymerase to direct expression of cloned genes. Methods Enzymol. 1990;185:60–89. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)85008-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tischer I, Gelderblom H, Vettermann W, Koch M A. A very small porcine virus with circular single-stranded DNA. Nature. 1982;295:64–66. doi: 10.1038/295064a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Walker J E, Saraste M, Runswick M J, Gay N J. Distantly related sequences in the alpha- and beta-subunits of ATP synthase, myosin, kinases and other ATP-requiring enzymes and a common nucleotide binding fold. EMBO J. 1982;1:945–951. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1982.tb01276.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Weisshart K, Taneja P, Fanning E. The replication protein A binding site in simian virus 40 (SV40) T antigen and its role in the initial steps of SV40 DNA replication. J Virol. 1998;72:9771–9781. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.12.9771-9781.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wu, R. Y., and L. R. You. Nucleotide sequence of DNA III and DNA IV associated with banana bunchy top virus and their relation to other closely related virus DNAs. GenBank accession no. U12586 and U12587.

- 80.Wu R Y, You L R, Soong T S. Nucleotide sequences of two circular single-stranded DNAs associated with banana bunchy top virus. Phytopathology. 1994;84:952–958. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yanisch-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 1985;33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yasukawa H, Hase T, Sakai A, Masamune Y. Rolling-circle replication of the plasmid pKYM isolated from a gram-negative bacterium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:10282–10286. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.22.10282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]