Abstract

This cross-sectional study identifies and quantifies state-level shortages in community-based perinatal psychiatry care in the US.

Introduction

In the US, 86% of women will become mothers and approximately 20% will experience a peripartum mood episode.1 Despite perinatal mental health accounting for substantial maternal mortality, 3 in 4 women do not receive treatment.2 One challenge for patients is finding psychiatric treatment. Nonpsychiatrist physicians have historically expressed a lack of training and confidence regarding mental health treatment of pregnant individuals, and many psychiatrists express similar hesitation. Meanwhile, long wait times for evaluation worsen depression and increase risk of self-harm ideation.3 Access to perinatal psychiatry subspecialists in academic centers is limited,4 yet the landscape of access in the community has not been well studied. This cross-sectional study identified and quantified state-level shortages in community-based perinatal psychiatry care.

Methods

Perinatal psychiatrist deficit by state was estimated using the equation:

| Deficit = [(0.22 × Annual State Births) – (No. of Perinatal Psychiatrists × Patient Panel Size)]/Patient Panel Size |

Number of perinatal psychiatrists was defined as psychiatrists indicating “pregnancy, prenatal, postpartum” as an issue they treat on Psychology Today as of November 11, 2022. Births per state were obtained from US Census data. The equation incorporates the point prevalence of positive postpartum depression screening results during the first postpartum year1 and existing estimates of community psychiatry patient panel size range.5 Density of perinatal psychiatrists was defined as the number per 5000 births in the state. Google Trends provided the relative predominance by state of the search term postpartum depression from November 11, 2021, to November 11, 2022; abortion restrictiveness as of November 15, 2022, was defined by the Guttmacher Institute. Spearman correlations were performed among variables of care density, postpartum depression searches, and abortion restrictiveness. Hypothesis tests were 2-sided (α = .05). Data analysis was performed using Prism, version 9.3.1, software. Exemption of institutional review board review was granted by Mass General Brigham. Informed consent was not required because the study used publicly accessible deidentified data. eMethods in Supplement 1 provides additional details. This study followed the STROBE reporting guidelines. Data on race were not available in the dataset, and data on ethnicity were not collected to mimic a maximally flexible search.

Results

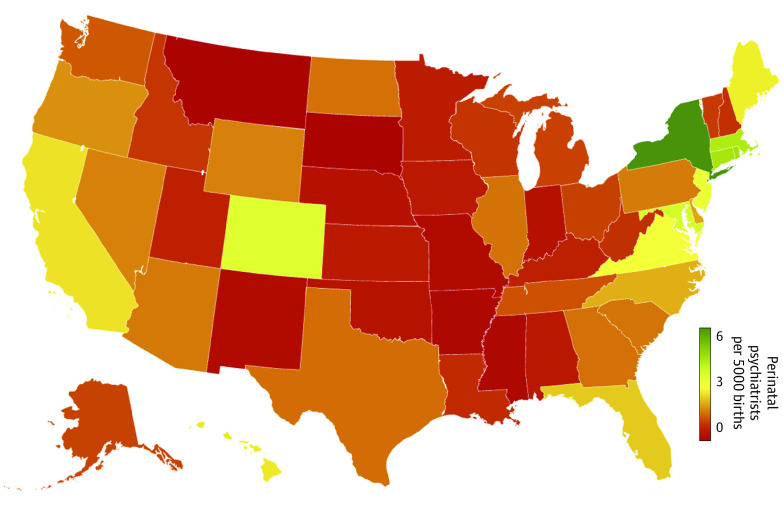

Twenty-one states had a ratio of less than 1 psychiatrist offering peripartum treatment per 5000 births (Figure). South Dakota, Montana, and Mississippi demonstrated the lowest density, while New York, Connecticut, and Rhode Island demonstrated the highest (Table); many states were estimated to require dozens to hundreds of additional specialists to fully meet projected needs. Where the density of perinatal psychiatrists was lower, Google searches for postpartum depression were more prevalent (R = −0.49; P < .001). More restrictive state policies on abortion were correlated with lower density of perinatal psychiatrists (R = −0.56; P < .001) and higher prevalence of Google searches (R = 0.55; P < .001).

Figure. Heatmap of Perinatal Psychiatrist Density in the US.

Data are based on the number of psychiatrists on the Psychology Today website indicating “pregnancy, prenatal, postpartum” as an issue they treat.

Table. Perinatal Psychiatrist Density in the US.

| State | Annual births in 2020 | Perinatal psychiatrists per 5000 births | Estimated deficit of perinatal psychiatrists |

|---|---|---|---|

| Montana | 10 791 | 0.00 | 5-24 |

| South Dakota | 10 960 | 0.00 | 5-24 |

| Mississippi | 35 473 | 0.14 | 15-77 |

| Arkansas | 35 251 | 0.14 | 14-76 |

| Missouri | 69 285 | 0.22 | 22-144 |

| New Mexico | 21 903 | 0.23 | 9-51 |

| Indiana | 78 616 | 0.38 | 30-168 |

| Nebraska | 24 291 | 0.41 | 9-51 |

| Oklahoma | 47 623 | 0.42 | 17-101 |

| Alabama | 57 647 | 0.52 | 21-123 |

| Iowa | 36 114 | 0.55 | 12-75 |

| Kansas | 34 376 | 0.58 | 9-70 |

| Minnesota | 63 443 | 0.63 | 21-133 |

| Utah | 45 702 | 0.66 | 13-94 |

| Kentucky | 51 668 | 0.68 | 15-106 |

| Louisiana | 57 328 | 0.78 | 17-118 |

| New Hampshire | 11 791 | 0.85 | 3-24 |

| West Virginia | 17 323 | 0.87 | 5-35 |

| Wisconsin | 60 594 | 0.91 | 19-125 |

| Idaho | 21 533 | 0.93 | 8-46 |

| Vermont | 5133 | 0.97 | 1-10 |

| Ohio | 129 191 | 1.04 | 30-257 |

| Alaska | 9469 | 1.06 | 2-19 |

| Michigan | 104 074 | 1.06 | 21-204 |

| Tennessee | 78 689 | 1.21 | 16-154 |

| Washington | 83 086 | 1.26 | 15-161 |

| Texas | 368 190 | 1.44 | 30-678 |

| Georgia | 122 473 | 1.47 | 8-223 |

| North Dakota | 10 059 | 1.49 | 3-21 |

| Illinois | 133 298 | 1.50 | 18-252 |

| South Carolina | 55 704 | 1.53 | 8-106 |

| Arizona | 76 947 | 1.56 | 0-135 |

| Pennsylvania | 130 693 | 1.57 | 11-241 |

| Wyoming | 6128 | 1.63 | 2-12 |

| Nevada | 33 653 | 1.63 | 7-66 |

| Oregon | 39 820 | 1.76 | 7-77 |

| Delaware | 10 392 | 1.92 | 1-19 |

| North Carolina | 116 730 | 2.01 | 18-224 |

| Florida | 209 671 | 2.27 | 0-360 |

| California | 420 259 | 2.47 | 0-671 |

| Hawaii | 15 785 | 2.53 | 0-28 |

| Maine | 11 539 | 2.60 | 1-21 |

| Virginia | 94 749 | 2.85 | 0-160 |

| New Jersey | 97 954 | 3.16 | 0-141 |

| Colorado | 61 494 | 3.33 | 0-103 |

| Maryland | 68 554 | 3.57 | 0-100 |

| Massachusetts | 66 428 | 4.22 | 0-100 |

| Connecticut | 33 460 | 4.33 | 0-43 |

| Rhode Island | 10 101 | 4.46 | 0-14 |

| New York | 209 338 | 5.92 | 0-194 |

Discussion

When attempting to self-refer in the community, individuals in most states confront a shortage of psychiatrists advertising peripartum care. Herein, we assumed optimal circumstances regarding insurance coverage and psychiatrist appointment availability and did not restrict the search to psychiatrists with additional formal training or credentials; however, prospective patients would encounter barriers to accessing care corresponding to a deficit of hundreds to thousands of perinatal psychiatrists nationwide. One study limitation is that no approach can be comprehensive in assessing the psychiatrist workforce, and some patients may receive treatment from obstetricians or nonphysician health care professionals. However, the data reflect what perinatal patients may encounter when seeking a psychiatrist. States with restrictive abortion policies are likely to see higher levels of psychological distress and suicidality6 in the peripartum population yet are underserved with regards to community access to perinatal psychiatry. Potential solutions for inadequate and unequal access to evidence-based perinatal psychiatric care include improving education regarding mental health treatment during pregnancy for general psychiatrists and obstetricians and minimizing geographic constraints on access to treatment.

eMethods. Acquisition and Analysis of Data

eReferences.

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Wisner KL, Sit DKY, McShea MC, et al. Onset timing, thoughts of self-harm, and diagnoses in postpartum women with screen-positive depression findings. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(5):490-498. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Byatt N, Levin LL, Ziedonis D, Moore Simas TA, Allison J. Enhancing participation in depression care in outpatient perinatal care settings: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126(5):1048-1058. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koire A, Nong YH, Cain CM, Greeley CS, Puryear LJ, Van Horne BS. Longer wait time after identification of peripartum depression symptoms is associated with increased symptom burden at psychiatric assessment. J Psychiatr Res. 2022;152:360-365. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2022.06.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morain SR, Fowler LR, Boyd JW. A pregnant pause: system-level barriers to perinatal mental health care. Health Promot Pract. 2023;24(5):804-807. doi: 10.1177/15248399221101373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McQuistion HL, Zinns R. Workloads in clinical psychiatry: another way. Psychiatr Serv. 2019;70(10):963-966. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201900125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zandberg J, Waller R, Visoki E, Barzilay R. Association between state-level access to reproductive care and suicide rates among women of reproductive age in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2023;80(2):127-134. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.4394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods. Acquisition and Analysis of Data

eReferences.

Data Sharing Statement