Abstract

Background.

Since 2000, the incidence of syphilis has been increasing, especially among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (MSM) in the United States. We assessed temporal trends and associated risk factors for newly diagnosed syphilis infections among human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–infected patients during a 16-year period.

Methods.

We analyzed data from the HIV Outpatient Study (HOPS) cohort participants at 10 US HIV clinics during 1999–2015. New syphilis cases were defined based on laboratory parameters and clinical diagnoses. We performed Cox proportional hazards regression analyses of sociodemographic, clinical, and behavioral risk factors for new syphilis infections.

Results.

We studied 6888 HIV-infected participants; 641 had 1 or more new syphilis diagnoses during a median follow-up of 5.2 years. Most participants were male (78%), aged 31–50 years, and 57% were MSM. The overall incidence was 1.8 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.6–1.9) per 100 person-years (PY) and it increased from 0.4 (95% CI, .2–.8) to 2.2 (95% CI, 1.4–3.5) per 100 PY during 1999–2015. In multivariable analyses adjusting for calendar year, risk factors for syphilis included age 18–30 years (hazard ratio [HR], 1.3 [95% CI, 1.1–1.6]) vs 31–40 years, being MSM (HR, 3.1 [95% CI, 2.4–4.1]) vs heterosexual male, and being non-Hispanic black (HR, 1.6 [95% CI, 1.4–1.9]) vs non-Hispanic white.

Conclusions.

The increases in the syphilis incidence rate through 2015 reflect ongoing sexual risk and highlight the need for enhanced prevention interventions among HIV-infected patients in care.

Keywords: syphilis, HIV, sexually transmitted disease, incidence, men who have sex with men

The incidence of syphilis has been increasing, especially among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (MSM) in the United States since the early 2000s [1–5]. Syphilis is more common among human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–infected than HIV-uninfected MSM, an indicator of unprotected sexual contact, and is associated with incident HIV infection [6–8]. Annual screening for syphilis among HIV-infected persons is the standard of care, but several studies suggest that more frequent testing is both cost-effective and more efficient at identifying infection [9–11].

Identifying and characterizing those at greatest risk for incident new and recurrent syphilis may lead to more targeted management and prevention as well as new approaches to syphilis control. Because HIV-infected persons who face barriers or challenges to consistent condom use may also face similar challenges in adhering to antiretroviral therapy (ART), syphilis infection, either new or recurrent, may be a marker of poor adherence to ART and may thus identify individuals more likely to transmit HIV due to viremia resulting from nonadherence (notwithstanding the biologic effects of syphilis on HIV replication due to inflammation or chronic immune activation) [12–17]. A 2007 study found that longer duration of HIV treatment is associated with a greater risk of incident syphilis, possibly due to improved health and perceived lower transmission risk [18]. Poor control of HIV may be associated with higher treatment failures for syphilis, although this is controversial [19–22]. Whether syphilis infection affects control of HIV infection is less clear [17, 23].

Understanding the current risk behaviors associated with new incident and recurrent cases of syphilis may better define who should be screened and at what frequency. Specifically, we sought to assess the temporal trends in and the risk factors for incident syphilis infections among HIV-infected patients in routine outpatient HIV care, and put them in the context of changing syphilis testing rates.

METHODS

The HIV Outpatient Study

The HIV Outpatient Study (HOPS) is an ongoing, prospective observational cohort study of HIV-infected adults receiving care at 9 specialty HIV clinics in 6 US cities (Chicago, Illinois; Denver, Colorado; Stony Brook, New York; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Tampa, Florida; and Washington, District of Columbia) since 1993. Patient data, including demographic and social characteristics, diagnoses, prescribed medications, and laboratory values, are abstracted from medical records and entered by trained staff into a single electronic database (Discovere©; Cerner Corporation, Kansas City, Missouri). These data were reviewed for quality and analyzed centrally. Data quality assurance measures include supervisory reviews of randomly selected charts to ascertain accuracy and completeness of abstracted data, and centralized checks of data files to resolve discrepancies. The HOPS protocol has been reviewed and approved annually by the institutional review boards of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Atlanta, Georgia) and each local site. The study protocol conforms to the guidelines of the US Department of Health and Human Services for the protection of human participants in research, and all participants provided written informed consent. The present analysis is based on the HOPS data through 31 December 2015.

Study Design, Population, Independent Variables, and Outcomes of Interest

We included HOPS participants who received care at an active HOPS site between 1 January 1999 and 30 June 2015. Patients with <2 visits recorded ever in the HOPS or <1 visit during the timeframe of this analysis were excluded. The start of observation for participants was considered to be the later of either 1 January 1999 or their first HOPS visit, hereafter referred to as the baseline date. The observation was discontinued at the earliest of death, last HOPS contact, inactive status date, or 30 June 2015.

We defined incident cases of syphilis based on the evidence of any of the following: a 4-fold increase in rapid plasma reagin (RPR) titer, a positive qualitative syphilis screen with a prior negative result, or both a documented syphilis diagnosis and record of treatment for syphilis. In addition, if a participant’s first recorded syphilis test result was positive, and there was no prior test history, but there was corroborative concurrent syphilis diagnosis or treatment evidence, then the participant was considered to have syphilis. Participants were considered to have been treated for syphilis if they had any of the following medications ordered with indication for syphilis: penicillin, bicillin, amoxicillin, doxycycline, tetracycline, ceftriaxone, or azithromycin. However, if a participant had a positive RPR with a prior negative RPR and had syphilis in the past, then he or she was additionally required to have either a syphilis diagnosis or be treated for syphilis to be considered a new case of syphilis.

Syphilis resolution was defined as a 4-fold decrease in RPR, a reduction of RPR to 0, or a negative qualitative screen with a previous positive screen.

Statistical Analysis

We categorized cohort participants by their HIV transmission risk group, defined as MSM, heterosexual males, heterosexual females, and men and women in other/unknown risk group. We then described these participants by their sociodemographic and HIV-related characteristics, all defined at the baseline date unless otherwise noted. These characteristics included age, sex (at birth), race/ethnicity, being a person who injects drugs (PWID), health insurance, AIDS status, chronic hepatitis B (HBV) infection status, chronic hepatitis C (HCV) infection status, calendar period of observation, CD4 cell count, and public vs private site of care (ie, HOPS clinic institution). HBV and HCV infection status as well as chlamydia and gonorrhea were all established based on a combination of laboratory test results and diagnoses available in the medical record. We compared these characteristics for differences by HIV transmission risk group using the Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables and χ2 or Fisher exact tests for categorical variables where appropriate. We also tested for bivariate differences in baseline characteristics between participants who ultimately were diagnosed with incident syphilis compared to those who were not diagnosed with syphilis. For participants who were diagnosed with incident syphilis, we compared their CD4 cell count, HIV RNA load, gonorrhea status, and chlamydia status at the time of the diagnosis according to HIV transmission risk group.

To contextualize our analyses of temporal trends in incidence of syphilis, we first analyzed temporal trends in syphilis testing in the HOPS during 1999–2015. Syphilis testing rates per 100 person-years (PY) of observation and associated 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were determined based on the presence of any treponemal or nontreponemal (whether diagnostic or screening) syphilis test in each given calendar year when a patient was under HOPS observation. Incident syphilis rates per 100 PY with 95% CIs were calculated by considering in the numerator all incident cases of syphilis (allowing multiple events per individual) during participants’ observation in this analysis. For syphilis incidence calculations, the denominator was not restricted by any syphilis screening requirements because some HOPS patients presented and were diagnosed with symptomatic syphilis but had no accompanying syphilis tests captured in the available medical record.

We calculated syphilis incidence rates first overall and then stratified by baseline characteristics: age group, sex at birth, race/ethnicity, HIV transmission risk group, and payor. To test for differences in incident syphilis rates, we conducted univariate and multivariable Poisson regression adjusting for baseline factors, including age, sex, race/ethnicity, HIV transmission risk group, PWID, insurance, CD4 cell count, use of antibiotic prophylaxis, HOPS site type, and calendar period of observation. Characteristics were included in the multivariable model using a stepwise selection with a cutoff of P = .05 at each stage. All analyses were conducted in SAS version 9.4 software (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina). Statistical results with P < .05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Cohort Characteristics

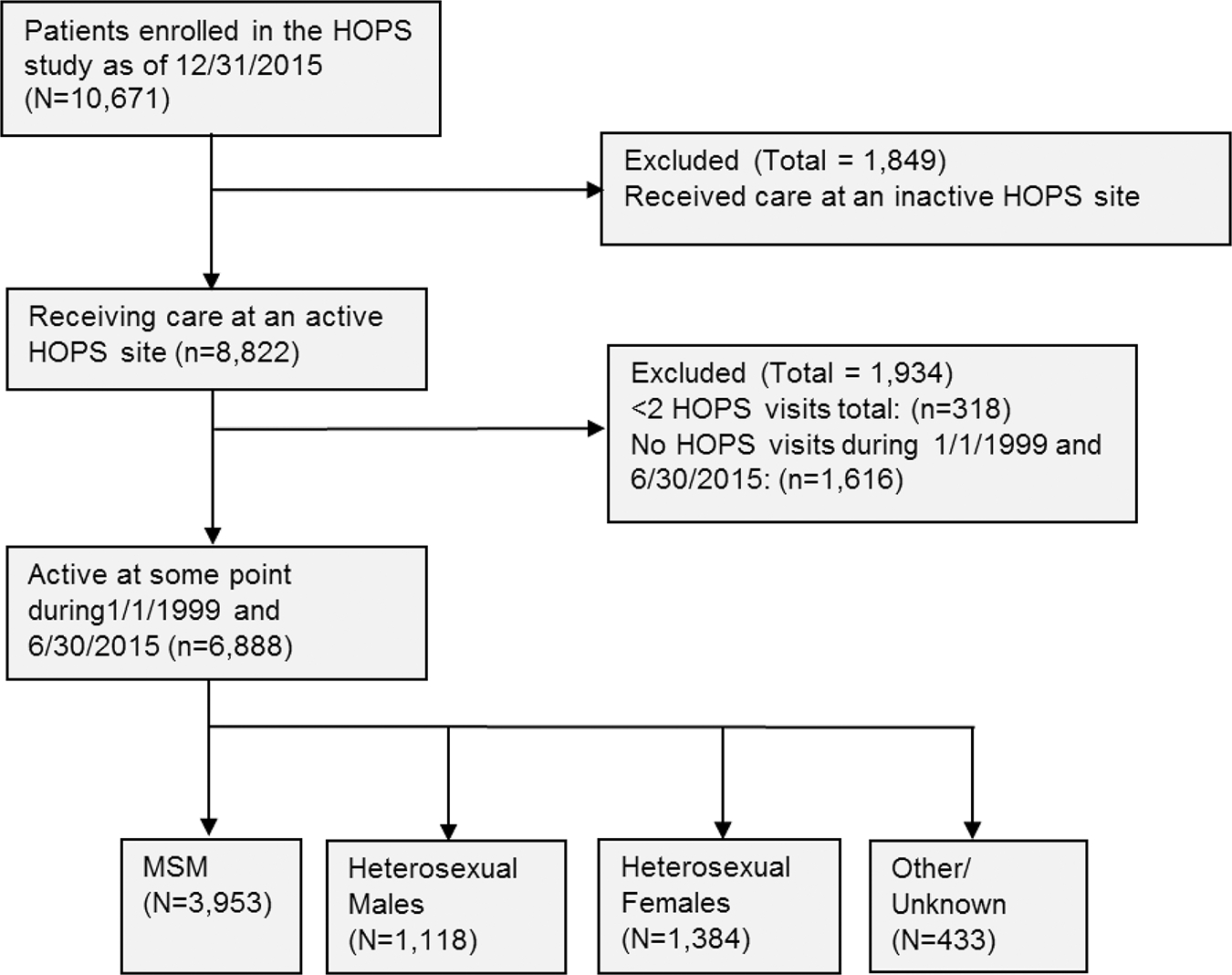

Among the 10 671 participants enrolled in the HOPS as of 31 December 2015, we excluded 3783 for the following reasons: 1849 patients received care at currently inactive HOPS sites, 318 had <2 HOPS visits total, and 1616 had no HOPS visits between 1 January 1999 and 30 June 2015 (Figure 1). Among the 6888 eligible participants included in this analysis, who were active between 1 January 1999 and 30 June 2015, most were MSM (57%), whereas 16% were heterosexual males and 20% were heterosexual females. Comparing the 1934 excluded to the 6888 included participants (Figure 1), excluded participants were more likely to be male (83% excluded vs 78% included, P < .001), white (64% excluded vs 49% included, P < .001), and have MSM risk (61% excluded vs 56% included) or injection drug use risk (15% excluded vs 10% included) (P < .001 for the HIV risk factors).

Figure 1.

Cohort selection flowchart, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) Outpatient Study, 1999–2015. Abbreviations: HOPS, HIV Outpatient Study; MSM, men who have sex with men.

Characteristics of Persons With and Without Syphilis

We identified 641 (9.3%) participants who had 1 or more new syphilis diagnoses (a total of 799 diagnoses) during a median follow-up of 5.2 (interquartile range [IQR], 2.0–10.8) years. Median time from baseline to first syphilis diagnosis was 3.5 (IQR, 1.0–6.9) years. The sociodemographic characteristics of the cohort and the groups with and without incident syphilis are presented in Table 1. The largest age group was 31–40 years old (37.8%) and 42.4% of incident syphilis diagnoses were in that age group (P < .001). The majority of participants were male (78.0%), and men represented 94.7% of persons with incident syphilis (P < .001); nearly half of the patients were non-Hispanic white (49.3%), and nearly half of the syphilis cases were white (49.8%), followed by non-Hispanic black (34.7% overall, 36.8% with syphilis) and Hispanic/Latino (12.3% overall, 9.4% with syphilis). The majority of participants (57.4%) were MSM, and MSM comprised 82.8% of the syphilis cases (P < .001). Whereas 52.2% of study participants had private insurance, private insurance was more common (63.5%) among those with syphilis; 38.1% overall had public insurance, and 22.0% among syphilis cases (P < .001). More than half of the study participants were enrolled in the HOPS before 2002 (56.4%) and 47.6% had a baseline CD4 count ≥350 cells/μL; of syphilis cases, 56.1% had a CD4 cell count ≥350 cells/mm3 (P < .001). Nearly half of the cohort (48.6%) had an AIDS diagnosis, and AIDS diagnosis was less common (39.8%) among persons who had incident syphilis.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics Among Those With and Without Syphilis Diagnosis, and by Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) Risk Category, HIV Outpatient Study, United States, 1999–2015 (N = 6888)

| Characteristics at Baseline Datea | Overall (n = 6888) | No Incident Syphilis (n = 6247) | Incident Syphilis (n = 641) | P Valueb | Incident Syphilis: MSM (n = 531) | Incident Syphilis: All Other (n = 110) | P Valueb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Age at baseline, y | <.001 | .16 | |||||

| 18–30 | 1160 (16.8) | 1003 (16.1) | 157 (24.5) | 138 (26.0) | 19 (17.3) | ||

| 31–40 | 2605 (37.8) | 2333 (37.3) | 272 (42.4) | 223 (42.0) | 49 (44.5) | ||

| 41–50 | 2204 (32.0) | 2031 (32.5) | 173 (27.0) | 141 (26.6) | 32 (29.1) | ||

| ≥51 | 919 (13.3) | 880 (14.1) | 39 (6.1) | 29 (5.5) | 10 (9.1) | ||

| Sex at birth | <.001 | ||||||

| Female | 1513 (22.0) | 1479 (23.7) | 34 (5.3) | ||||

| Male | 5375 (78.0) | 4768 (76.3) | 607 (94.7) | ||||

| Race/ethnicity | .10 | <.001 | |||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 3398 (49.3) | 3079 (49.3) | 319 (49.8) | 301 (56.7) | 18 (16.4) | ||

| Non-Hispanic black | 2390 (34.7) | 2154 (34.5) | 236 (36.8) | 166 (31.3) | 70 (63.6) | ||

| Hispanic/Latino | 847 (12.3) | 787 (12.6) | 60 (9.4) | 46 (8.7) | 14 (12.7) | ||

| Other/unknown | 253 (3.7) | 227 (3.6) | 26 (4.1) | 18 (3.4) | 8 (7.3) | ||

| HIV transmission risk group | <.001 | ||||||

| MSM | 3953 (57.4) | 3422 (54.8) | 531 (82.8) | ||||

| Heterosexual male | 1118 (16.2) | 1063 (17.0) | 55 (8.6) | ||||

| Heterosexual female | 1384 (20.1) | 1350 (21.6) | 34 (5.3) | ||||

| Other/unknown | 433 (6.3) | 412 (6.6) | 21 (3.3) | ||||

| PWID | 690 (10.0) | 666 (10.7) | 24 (3.7) | ||||

| Insurance | <.001 | <.001 | |||||

| Private | 3596 (52.2) | 3189 (51.0) | 407 (63.5) | 372 (70.1) | 35 (31.8) | ||

| Public | 2624 (38.1) | 2483 (39.7) | 141 (22.0) | 85 (16.0) | 56 (50.9) | ||

| Self pay/none | 409 (5.9) | 341 (5.5) | 68 (10.6) | 57 (10.7) | 11 (10.0) | ||

| Other/unknown | 259 (3.8) | 234 (3.7) | 25 (3.9) | 17 (3.2) | 8 (7.3) | ||

| Clinic type | .07 | <.001 | |||||

| Private | 4303 (62.5) | 3881 (62.1) | 422 (65.8) | 393 (74.0) | 29 (26.4) | ||

| Public (academic) | 2585 (37.5) | 2366 (37.9) | 219 (34.2) | 138 (26.0) | 81 (73.6) | ||

| Prior AIDS diagnosis | 3348 (48.6) | 3093 (49.5) | 255 (39.8) | <.001 | 194 (36.5) | 61 (55.5) | <.001 |

| Chronic HBV infection | 398 (5.8) | 345 (5.5) | 53 (8.3) | .005 | 38 (7.2) | 15 (13.6) | .040 |

| Chronic HCV infection | 876 (12.7) | 832 (13.3) | 44 (6.9) | <.001 | 22 (4.1) | 22 (20.0) | <.001 |

| Calendar period of baseline | <.001 | .002 | |||||

| 1999–2002 | 3884 (56.4) | 3598 (57.6) | 286 (44.6) | 222 (41.8) | 64 (58.2) | ||

| 2003–2006 | 1326 (19.3) | 1176 (18.8) | 150 (23.4) | 125 (23.5) | 25 (22.7) | ||

| 2007–2010 | 1021 (14.8) | 880 (14.1) | 141 (22.0) | 124 (23.4) | 17 (15.5) | ||

| 2011–2015 | 657 (9.5) | 593 (9.5) | 64 (10.0) | 60 (11.3) | 4 (3.6) | ||

| CD4 count at baselinec, cells/μL | <.001 | .002 | |||||

| <50 | 588 (8.5) | 552 (8.8) | 36 (5.6) | 26 (4.9) | 10 (9.1) | ||

| 50–199 | 1016 (14.8) | 937 (15.0) | 79 (12.3) | 65 (12.2) | 14 (12.7) | ||

| 200–349 | 1272 (18.5) | 1156 (18.5) | 116 (18.1) | 90 (17.0) | 26 (23.6) | ||

| 350–499 | 1182 (17.2) | 1046 (16.7) | 136 (21.2) | 117 (22.0) | 19 (17.3) | ||

| ≥500 | 2094 (30.4) | 1870 (29.9) | 224 (34.9) | 199 (37.5) | 25 (22.7) | ||

| Unknown | 736 (10.7) | 686 (11.0) | 50 (7.8) | 34 (6.4) | 16 (14.6) | ||

| Median CD4 count at baseline, cells/μL (IQR) (n = 6152) | 371 (191–581) | 366 (185–580) | 411 (250–587) | <.001 | 429 (264–597) | 337 (189–527) | .004 |

| Viral load at baseline <200 copies/mL (n = 6805) | 2598 (38.2) | 2357 (38.2) | 241 (37.7) | .83 | 206 (38.9) | 35 (32.1) | .22 |

| Median log10 viral load at baseline, copies/mL (IQR) (n = 6805) | 3.25 (1.70–4.65) | 3.24 (1.70–4.65) | 3.45 (1.67–4.69) | .55 | 3.41 (1.40–4.70) | 3.56 (2.30–4.64) | .23 |

| ART history at baseline | <.001 | .62 | |||||

| Experienced | 4442 (64.5) | 4082 (65.3) | 360 (56.2) | 302 (56.9) | 58 (52.7) | ||

| Naive | 2118 (30.7) | 1849 (29.6) | 269 (42.0) | 220 (41.4) | 49 (44.6) | ||

| Unknown | 328 (4.8) | 316 (5.1) | 12 (1.9) | 9 (1.7) | 3 (2.7) | ||

| CD4 count closest to syphilis case, cells/μL | .005 | ||||||

| <50 | 10 (1.6) | 5 (0.9) | 5 (4.5) | ||||

| 50–199 | 63 (9.8) | 48 (9.0) | 15 (13.6) | ||||

| 200–349 | 123 (19.2) | 103 (19.4) | 20 (18.2) | ||||

| 350–499 | 154 (24.0) | 126 (23.7) | 28 (25.5) | ||||

| ≥500 | 265 (41.3) | 231 (43.5) | 34 (30.9) | ||||

| Unknown | 26 (4.1) | 18 (3.4) | 8 (7.3) | ||||

| Viral load closest to syphilis case, copies/mL | .036 | ||||||

| 0–199 | 383 (59.8) | 329 (62.0) | 54 (49.1) | ||||

| 200–999 | 55 (8.6) | 40 (7.5) | 15 (13.6) | ||||

| 1000–99 999 | 131 (20.4) | 103 (19.4) | 28 (25.5) | ||||

| ≥100 000 | 35 (5.5) | 31 (5.8) | 4 (3.6) | ||||

| Unknown | 37 (5.8) | 28 (5.3) | 9 (8.2) | ||||

| Gonorrhea prior to syphilis case | 77 (12.0) | 70 (13.2) | 7 (6.4) | .045 | |||

| Chlamydia prior to syphilis case | 53 (8.3) | 45 (8.5) | 8 (7.3) | .68 | |||

| Chronic HBV prior to syphilis case | 75 (11.7) | 55 (10.4) | 20 (18.2) | .020 | |||

| Chronic HCV prior to syphilis case | 74 (11.5) | 46 (8.7) | 28 (25.5) | <.001 | |||

Data are presented as No. (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; IQR, interquartile range; MSM, men who have sex with men; PWID, people who inject drugs.

Baseline date is the later of first HIV Outpatient Study visit or 1 January 1999.

Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables, χ2 test for categorical variables.

Closest value to baseline from values documented 6 months prior to 3 months after the baseline date.

Compared with participants who did not have incident syphilis during observation, those who had incident syphilis were more likely to be younger, male, MSM, have private insurance, be coinfected with chronic HBV, have been seen in clinic in a more recent calendar period, and have received care at a private institution. They were also less likely to be PWID, diagnosed with AIDS, have chronic HCV coinfection, and be ART experienced (P < .05 for all; Table 1).

Among the 641 participants who were diagnosed with incident syphilis, most (85%) had CD4 counts ≥200 cells/μL at the time of infection (Table 1). MSM tended to have higher CD4 cell counts at the time of infection compared with other HIV transmission risk groups. MSM also had lower HIV RNA loads. Although the majority of persons with syphilis had fully suppressed viral load, there were still >25% of syphilis cases who had a proximal viral load of ≥1000 copies/mL, suggesting occurrence of condomless sex in the setting of syphilis coinfection and possible heightened HIV transmission risk. Recent or concurrent gonorrhea and chlamydia were uncommon in this group, and chronic HBV and chronic HCV were less prevalent among MSM than other HIV transmission risk groups (Table 1).

Syphilis Testing

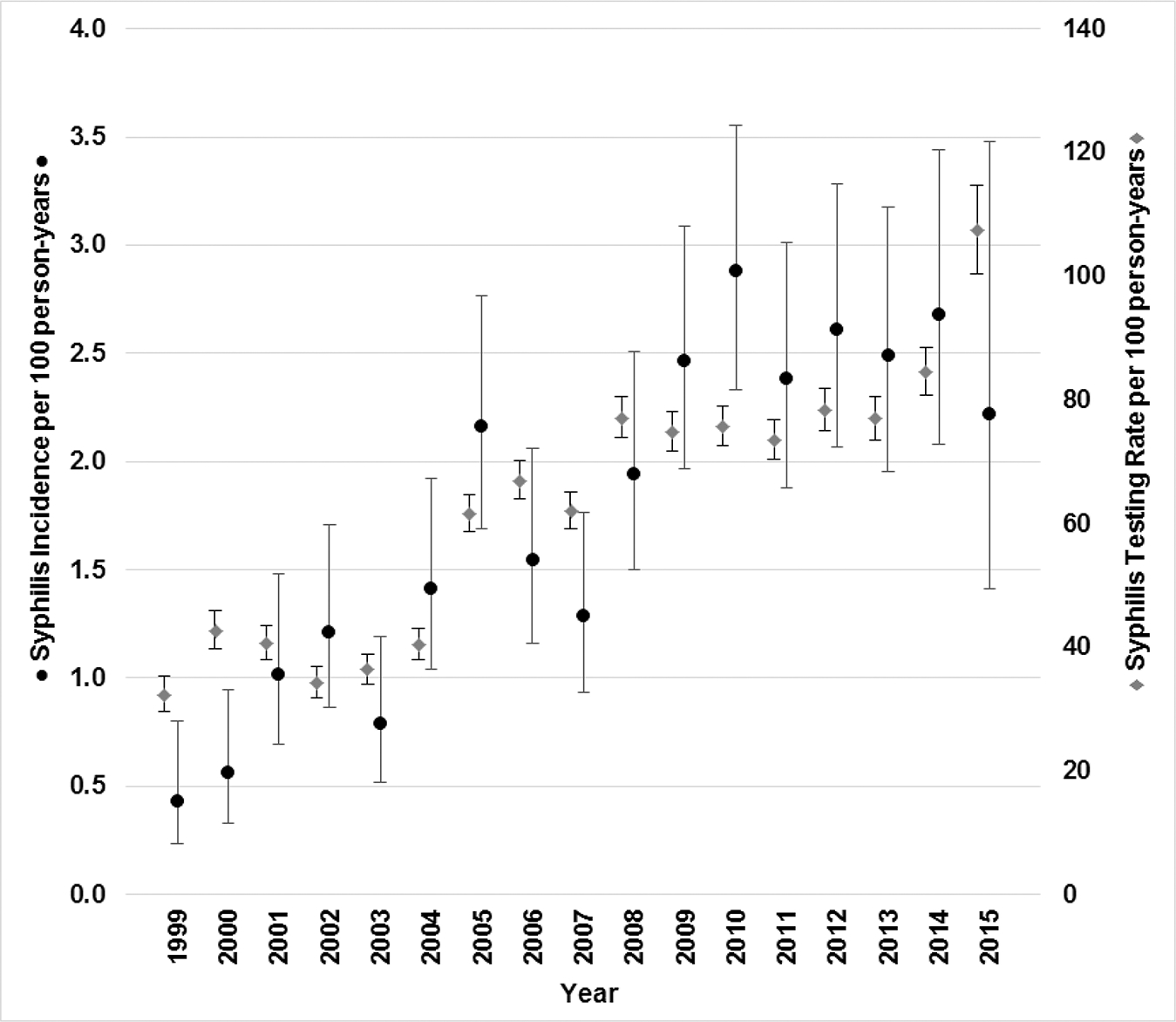

We analyzed syphilis testing rates and compared these to syphilis incidence rates by HIV risk group. Overall, testing rates (determined by presence of RPR or fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption) were 54 tests per 100 PY, and were lower among MSM (53 tests per 100 PY) compared with heterosexual males (59 tests per 100 PY) or heterosexual females (54 tests per 100 PY) (P < .001; Table 2). Syphilis testing was significantly higher among those whose insurance coverage status was “self pay/none” or on public insurance compared to privately insured persons. There was a coincident increase in syphilis testing rates and syphilis incidence rates over time; syphilis incidence rates increased from 0.43 (95% CI, .23–.80) per 100 PY to 2.22 (95% CI, 1.41–3.47) per 100 PY during 1999–2015 (Figure 2).

Table 2.

Unadjusted Syphilis Testing Rates and Syphilis Incidence Rates by Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) Transmission Category, HIV Outpatient Study, United States, 1999–2015

| Overall | MSM | Heterosexual Males | Heterosexual Females | Other/Unknown | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Characteristic | (n = 6888) | (n = 3953) | (n = 1118) | (n = 1384) | (n = 433) |

|

| |||||

| Syphilis testing rate (95% CI) | |||||

| Overall | 54 (53–55) | 53 (52–54) | 59 (57–60) | 54 (53–56) | 48 (46–51) |

| Age at baseline date, y | |||||

| 18–30 | 67 (65–69) | 76 (73–79) | 61 (55–68) | 56 (53–60) | 57 (51–65) |

| 31–40 | 52 (51–53) | 52 (51–53) | 58 (55–61) | 51 (49–54) | 49 (45–53) |

| 41–50 | 52 (51–53) | 49 (48–51) | 59 (56–62) | 57 (54–60) | 48 (43–53) |

| ≥51 | 49 (48–51) | 45 (43–47) | 59 (55–64) | 56 (52–61) | 39 (34–45) |

| Sex at birth | |||||

| Female | 53 (52–55) | NA | NA | 54 (53–56) | 47 (42–52) |

| Male | 54 (53–55) | 53 (52–54) | 59 (57–61) | NA | 49 (46–52) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 48 (47–49) | 47 (47–48) | 50 (47–54) | 49 (46–52) | 43 (40–47) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 63 (61–64) | 67 (64–69) | 64 (61–66) | 59 (56–61) | 59 (54–65) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 60 (58–63) | 70 (67–74) | 60 (56–64) | 50 (46–53) | 52 (45–60) |

| Other/unknown | 51 (48–55) | 59 (54–65) | 45 (36–55) | 50 (42–60) | 38 (32–46) |

| Insurance | |||||

| Private | 49 (48–50) | 49 (48–50) | 52 (49–55) | 47 (45–50) | 40 (37–44) |

| Public | 60 (59–62) | 63 (61–65) | 61 (59–64) | 58 (56–60) | 59 (54–64) |

| Self-pay/none | 71 (68–75) | 75 (71–80) | 72 (65–81) | 61 (55–69) | 48 (37–64) |

| Other/unknown | 52 (48–55) | 58 (52–64) | 68 (55–84) | 35 (29–42) | 50 (43–57) |

| HOPS site type | |||||

| Private | 44 (43–45) | 46 (45–47) | 38 (35–41) | 33 (31–35) | 41 (38–44) |

| Public | 73 (71–74) | 89 (86–92) | 67 (65–70) | 65 (63–67) | 70 (64–77) |

| Syphilis incidence rate (95% CI) | |||||

| Overall | 1.8 (1.6–1.9) | 2.5 (2.3–2.7) | 1.0 (.8–1.3) | 0.4 (.3–.6) | 0.9 (.6–1.3) |

| Age at baseline date, y | |||||

| 18–30 | 3.0 (2.6–3.5) | 5.1 (4.4–5.9) | 1.8 (1.0–3.4) | 0.4 (.2–.8) | 0.9 (.3–2.3) |

| 31–40 | 1.8 (1.7–2.0) | 2.5 (2.2–2.8) | 1.2 (.8–1.7) | 0.5 (.3–.8) | 1.2 (.7–2.1) |

| 41–50 | 1.5 (1.3–1.7) | 2.0 (1.8–2.4) | 0.9 (.6–1.3) | 0.3 (.2–.7) | 0.9 (.4–1.8) |

| ≥51 | 0.8 (.6–1.0) | 1.1 (.8–1.6) | 0.5 (.2–1.2) | 0.2 (.1–.8) | 0.4 (.1–1.7) |

| Sex at birth | |||||

| Female | 0.4 (.3–.5) | NA | NA | 0.4 (.3–.6) | |

| Male | 2.2 (2.0–2.3) | 2.5 (2.3–2.7) | 1.0 (.8–1.3) | NA | 1.3 (.9–1.9) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 1.6 (1.5–1.8) | 2.0 (1.8–2.2) | 0.6 (.3–1.1) | 0.1 (.0–.4) | 0.9 (.5–1.5) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 2.1 (1.9–2.4) | 4.6 (4.0–5.2) | 1.2 (.9–1.7) | 0.6 (.4–.9) | 1.0 (.5–2.1) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 1.3 (1.0–1.6) | 2.7 (2.0–3.5) | 0.8 (.4–1.4) | 0.1 (.0–.5) | 0.8 (.2–2.4) |

| Other/unknown | 2.1 (1.5–3.0) | 3.2 (2.1–4.8) | 1.5 (.5–4.6) | 0.9 (.2–3.4) | 0.9 (.3–2.9) |

| Insurance | |||||

| Private | 2.0 (1.8–2.1) | 2.3 (2.1–2.6) | 1.2 (.8–1.7) | 0.1 (.0–.4) | 0.9 (.5–1.6) |

| Public | 1.1 (1.0–1.3) | 2.4 (2.0–2.9) | 0.6 (.4–1.0) | 0.5 (.4–.8) | 0.8 (.4–1.6) |

| Self-pay/none | 3.6 (2.9–4.4) | 5.1 (4.1–6.4) | 2.5 (1.4–4.7) | 0.4 (.1–1.7) | NA |

| Other/unknown | 1.8 (1.2–2.6) | 2.6 (1.6–4.1) | 2.4 (.8–73) | 0.3 (.0–2.2) | 1.3 (.5–3.0) |

| HOPS site type | |||||

| Private | 1.9 (1.7–2.1) | 2.2 (2.0–2.4) | 0.7 (.3–1.5) | 0.1 (.0–.5) | 0.6 (.3–1.5) |

| Public | 1.7 (1.5–1.8) | 3.1 (2.8–3.4) | 1.0 (.8–1.3) | 0.5 (.3–.6) | 1.0 (.7–1.6) |

Rates are reported as per 100 person-years. There were statistical differences in distribution by human immunodeficiency virus transmission risk group for each variable category in the table (all P < .001).

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HOPS, HIV Outpatient Study; MSM, men who have sex with men; NA, not applicable.

Figure 2.

Syphilis incidence and testing rates by year, human immunodeficiency virus Outpatient Study, 1999–2015 (N = 6888).

Syphilis Incidence and Risk Factors

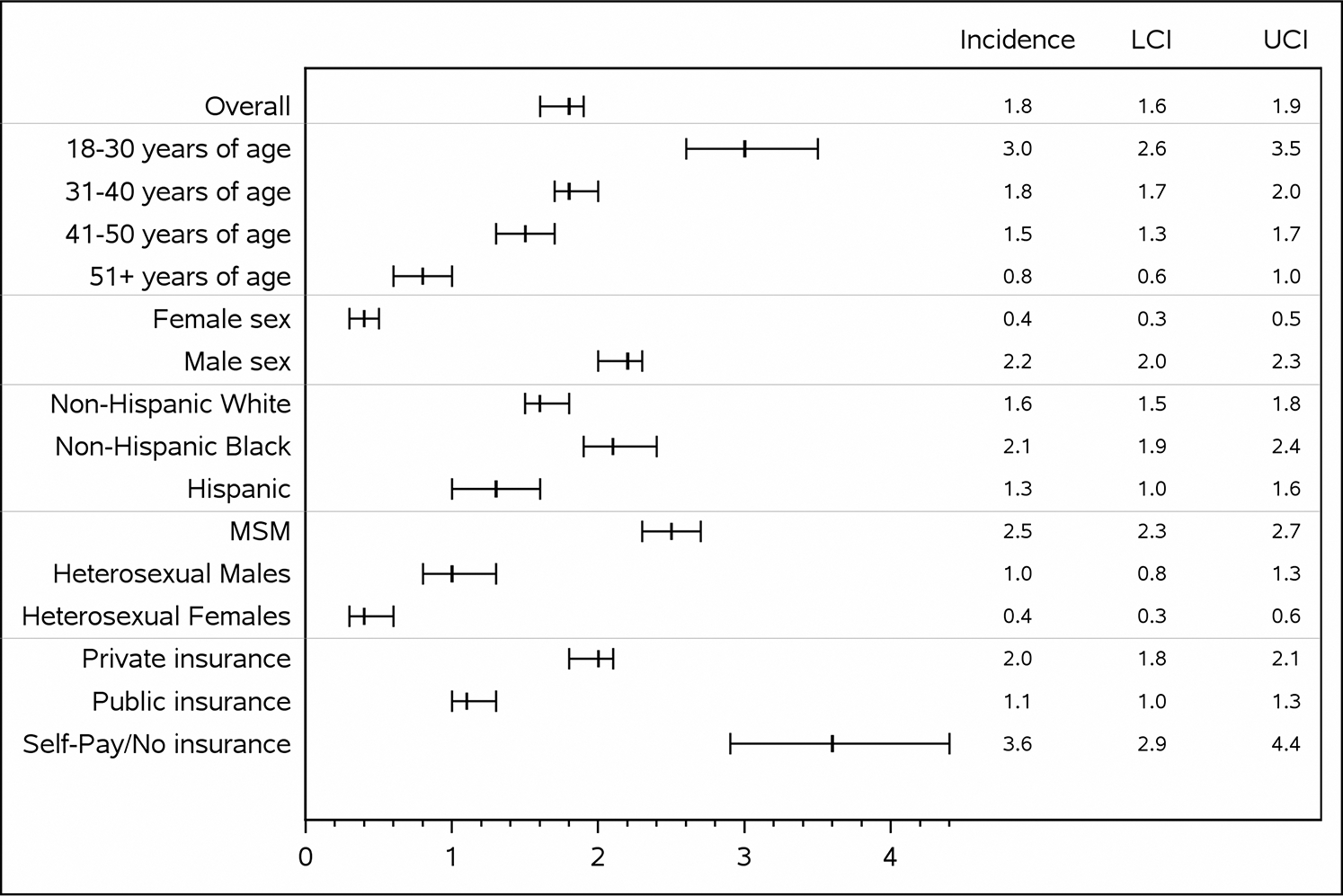

There were a total of 799 syphilis diagnoses among 641 participants, for an overall incidence of 1.8 (95% CI, 1.6–1.9) per 100 PY (Table 2; Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Syphilis incidence rates per 100 person-years with 95% confidence interval bars, the HIV Outpatient Study, 1999–2015 (N = 6888). Abbreviations: HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; LCI, lower confidence interval; MSM, men who have sex with men; UCI, upper confidence interval.

For MSM the rate was the highest, at 2.5 (95% CI, 2.3–2.7, P < .001) per 100 PY, and it was particularly high for MSM who were aged 18–30 years (5.1 [95% CI, 4.4–5.9]), non-Hispanic black (4.6 [95% CI, 4.0–5.2]), and whose insurance status was “self pay/none” (5.1 [95% CI, 4.1–6.4]).

Incident syphilis cases were disproportionately represented by young, black MSM. There were 256 and 312 (3.7% and 4.5% of the 6888 participant total, respectively) 18- to 30-year-old and 31- to 40-year-old black MSM participants in our study. Among those with syphilis, there were 70 and 61 (10.9% and 9.5% of 641, respectively) 18- to 30-year-old and 31- to 40-year-old black MSM participants.

We examined correlates of incident syphilis by computing incidence rate ratios for a number of independent variables in univariate and multivariate analysis (Table 3). Age 18–30 years was an independent risk factor for syphilis with an adjusted relative risk (aRR) of 1.33 in multivariate analysis (95% CI, 1.10–1.61) compared with the age group 31–40 years. Non-Hispanic blacks were disproportionately at risk with an aRR of 1.62 (95% CI, 1.37–1.91) relative to non-Hispanic whites. Compared with heterosexual males, MSM were at increased risk for incident syphilis (aRR, 3.11 [95% CI, 2.38–4.06]) as were those who began observation in the later calendar years (Table 3).

Table 3.

Syphilis Incidencea Rate Ratios Among Active Participants Receiving Care From 1999 to 2015, Human Immunodeficiency Virus Outpatient Study, United States (N = 6888)

| Independent Variables | Univariate RR (95% CI) | P Value | Multivariable aRR (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Age group, y | ||||

| 18–30 | 1.69 (1.36–2.09) | <.001 | 1.33 (1.10–1.61) | .003 |

| 31–40 | Referent | Referent | ||

| 41–50 | 0.82 (.66–1.01) | .058 | 0.80 (.67–.95) | .011 |

| ≥51 | 0.41 (.29–.58) | <.001 | 0.43 (.31–.60) | <.001 |

| Female sex | 0.17 (.12–.24) | <.001 | ||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic white | Referent | Referent | ||

| Non-Hispanic black | 1.30 (1.08–1.57) | .005 | 1.62 (1.37–1.91) | <.001 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 0.78 (.58–1.05) | .097 | 0.86 (.66–1.13) | .28 |

| Other/unknown | 1.28 (.84–1.97) | .25 | 1.44 (.99–2.09) | .054 |

| HIV transmission risk group | ||||

| MSM | 2.63 (1.97–3.50) | <.001 | 3.11 (2.38–4.06) | <.001 |

| Heterosexual males | Referent | Referent | ||

| Heterosexual females | 0.41 (.27–.64) | <.001 | 0.35 (.23–.52) | <.001 |

| Other/unknown | 0.92 (.54–1.57) | .76 | 0.87 (.54–1.38) | .55 |

| Injection drug use | 0.31 (.21–.47) | <.001 | ||

| Insurance | ||||

| Private | Referent | |||

| Public | 0.57 (.46–.70) | <.001 | ||

| Self pay/none | 1.87 (1.40–2.50) | <.001 | ||

| Other/unknown | 0.90 (.59–1.37) | .61 | ||

| CD4 count at baseline date, cells/μL | ||||

| <200 | 0.71 (.56–.90) | .005 | ||

| 200–349 | 0.81 (.63–1.03) | .088 | ||

| 350–499 | 1.12 (.89–1.43) | .34 | ||

| ≥500 | Referent | |||

| Unknown | 0.54 (.39–.74) | <.001 | ||

| Antibiotic prophylaxisb | 0.39 (.28–.54) | <.001 | ||

| HOPS site type | ||||

| Private | 1.14 (.96–1.35) | .13 | ||

| Public | Referent | |||

| Calendar period of baseline date | ||||

| 1999 | Referent | |||

| 2000–2004 | 1.81 (1.44–2.26) | <.001 | 1.48 (1.22–1.80) | <.001 |

| 2005–2009 | 3.49 (2.80–4.34) | <.001 | 2.08 (1.57–2.74) | <.001 |

| 2010–2015 | 5.57 (4.11–756) | <.001 | 4.19 (3.15–5.58) | <.001 |

Stepwise selection was used to choose variables for inclusion in the multivariable model with a P = .05 cutoff.

Abbreviations: aRR, adjusted rate ratio; CI, confidence interval; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HOPS, HIV Outpatient Study; MSM, men who have sex with men; RR, rate ratio.

There were 799 cases of incident syphilis among 641 participants in this analysis.

Antibiotic prophylaxis includes azithromycin and/or Bactrim given as prophylaxis prior to the baseline date.

DISCUSSION

Over a 16-year period of observation, we noted a steady increase in both testing for syphilis and incident syphilis cases in our multisite cohort of patients in HIV care. The rates of syphilis infections were elevated among young patients who were non-Hispanic black, MSM, and those without health insurance. Our findings are consistent with national and regional trends in syphilis among MSM [1, 2, 7, 24].

Surveys of sexual behavior among HIV-infected MSM have documented increasing frequency of condomless sex in the past decade [25, 26]. Some HIV-infected men may be more likely to “serosort” by seeking sexual partners of the same HIV status, and this behavior may influence their sexual networking choices [27–29], which in turn can influence their risk of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) [30]. The established association of syphilis and HIV transmission in itself indicates that serodiscordant transmission of syphilis must occur [13]. As others have observed, syphilis may be a marker of poor adherence to HIV therapy and may identify individuals more likely to transmit their HIV infections [12–15]. We similarly found that >25% of patients with syphilis had suboptimal control of their HIV RNA load. There is widespread debate as to the effect of antiretrovirals used for HIV prevention (ie, pre-exposure prophylaxis, postexposure prophylaxis) on the incidence of STIs such as syphilis [31–33]. The fact that 75% of syphilis cases in our cohort occurred in the setting of well-controlled HIV infection is notable. It is likely, however, that the smaller fraction of HIV-infected persons with poor virologic control and syphilis infection are contributing to ongoing HIV transmission.

The rates of syphilis testing differed by demographic factors but in general increased over time for all groups. Although the increased syphilis screening may have contributed to the increased new syphilis diagnoses, it reflects the growing recognition of increasing syphilis burden in the HIV-infected and MSM populations [34].

Our findings are subject to limitations. Our data were obtained from chart abstraction of patients in HIV care; testing for syphilis (both diagnostic for symptomatic cases, and screening for asymptomatic patients) was conducted as per prevailing practices at the clinic sites, and there were no regular periodic STI screening assessments. We did not have consistent information on the stage of syphilis (primary, secondary, etc). About 7% of the diagnoses were made at the patients’ baseline visit (ie, the first visit in the HOPS in the timeframe of our analysis), and while they fit our definition of an incident case, which includes treatment as such by the treating clinician, we cannot exclude the possibility that some of these cases may be latent. If a fraction of these few baseline cases did not represent new cases of syphilis (ie, were misclassified), then the overall syphilis rates in our analysis would be overestimated, by no more than about 10%. Conversely, we cannot exclude the possibility that some patients were diagnosed with syphilis outside of our clinics, which would lead us to underestimate syphilis rates in our cohort. Furthermore, patients with syphilis frequently were referred or opted to receive follow-up care and treatment outside of the HOPS clinics, and therefore we could not reliably study the rates of syphilis treatment and cure. Both syphilis testing and syphilis incidence increased over time, likely due to increased recognition of risk. Trends in syphilis incidence may reflect in part improved screening and detection of asymptomatic syphilis cases.

In conclusion, we noted steady increases in the syphilis incidence rate through 2015, particularly among HIV-infected patients who are younger, non-Hispanic/Latino, and MSM, reflecting ongoing sexual risk among HIV-infected patients in care. These results support the need for ongoing syphilis testing and comprehensive sexual risk reduction interventions in this population.

Financial support.

This work was supported by the CDC (contract numbers 200-2001-00133, 200-2006-18797, and 200-2011-41872).

HIV Outpatient Study Investigators

Kate Buchacz and Marcus D. Durham, Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention, National Center for HIV, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Atlanta, Georgia; Harlen Hays, Rachel Hart, Thilakavathy Subramanian, Carl Armon, Stacey Purinton, Dana Franklin, Cheryl Akridge, Nabil Rayeed, and Linda Battalora, Cerner Corporation, Kansas City, Missouri; Frank J. Palella, Saira Jahangir, Conor Daniel Flaherty, and Patricia Bustamante, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, Chicago, Illinois; John Hammer, Kenneth S. Greenberg, Barbara Widick, and Rosa Franklin, Rose Medical Center, Denver, Colorado; Bienvenido G. Yangco and Kalliope Chagaris, Infectious Disease Research Institute, Tampa, Florida; Douglas J. Ward, Troy Thomas, and Cheryl Stewart, Dupont Circle Physicians Group, Washington, D.C.; Jack Fuhrer, Linda Ording-Bauer, Rita Kelly, and Jane Esteves, State University of New York, Stony Brook; Ellen M. Tedaldi, Ramona A. Christian, Faye Ruley, Dania Beadle, and Princess Davenport, Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Richard M. Novak and Andrea Wendrow, University of Illinois at Chicago; Benjamin Young, Mia Scott, Barbara Widick, and Billie Thomas, APEX Family Medicine, Denver, Colorado.

Footnotes

Potential conflicts of interest. R. H. has received payments from the National Institutes of Health. R. M. N. has received fees for expert testimony from Wilson, Sonsini, Goodrich, and Rosati. All other authors report no potential conflicts. Authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

Disclaimer. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Notes from the field: repeat syphilis infection and HIV coinfection among men who have sex with men—Baltimore, Maryland, 2010–2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2013; 62:649–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abara WE, Hess KL, Neblett Fanfair R, Bernstein KT, Paz-Bailey G. Syphilis trends among men who have sex with men in the United States and Western Europe: a systematic review of trend studies published between 2004 and 2015. PLoS One 2016; 11:e0159309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Branger J, van der Meer JT, van Ketel RJ, Jurriaans S, Prins JM. High incidence of asymptomatic syphilis in HIV-infected MSM justifies routine screening. Sex Transm Dis 2009; 36:84–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ganesan A, Fieberg A, Agan BK, et al. ; Infectious Disease Clinical Research Program HIV Working Group. Results of a 25-year longitudinal analysis of the serologic incidence of syphilis in a cohort of HIV-infected patients with unrestricted access to care. Sex Transm Dis 2012; 39:440–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2015. Atlanta, GA: CDC, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buchacz K, Greenberg A, Onorato I, Janssen R. Syphilis epidemics and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) incidence among men who have sex with men in the United States: implications for HIV prevention. Sex Transm Dis 2005; 32:S73–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buchacz K, Klausner JD, Kerndt PR, et al. HIV incidence among men diagnosed with early syphilis in Atlanta, San Francisco, and Los Angeles, 2004 to 2005. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2008; 47:234–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horberg MA, Ranatunga DK, Quesenberry CP, Klein DB, Silverberg MJ. Syphilis epidemiology and clinical outcomes in HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected patients in Kaiser Permanente Northern California. Sex Transm Dis 2010; 37:53–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bissessor M, Fairley CK, Leslie D, Howley K, Chen MY. Frequent screening for syphilis as part of HIV monitoring increases the detection of early asymptomatic syphilis among HIV-positive homosexual men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2010; 55:211–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trubiano JA, Hoy JF. Taming the great: enhanced syphilis screening in HIV-positive men who have sex with men in a hospital clinic setting. Sex Health 2015; 12:176–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tuite AR, Burchell AN, Fisman DN. Cost-effectiveness of enhanced syphilis screening among HIV-positive men who have sex with men: a microsimulation model. PLoS One 2014; 9:e101240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cooley LA, Pearl ML, Flynn C, et al. Low viral suppression and high HIV diagnosis rate among men who have sex with men with syphilis—Baltimore, Maryland. Sex Transm Dis 2015; 42:226–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pathela P, Braunstein SL, Blank S, Shepard C, Schillinger JA. The high risk of an HIV diagnosis following a diagnosis of syphilis: a population-level analysis of New York City men. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 61:281–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peterman TA, Newman DR, Maddox L, Schmitt K, Shiver S. High risk for HIV following syphilis diagnosis among men in Florida, 2000–2011. Public Health Rep 2014; 129:164–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taylor MM, Li WY, Skinner J, Mickey T. Viral loads among young HIV-infected men with early syphilis. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care 2014; 13:501–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taylor MM, Newman DR, Schillinger JA, et al. Viral loads among HIV-infected persons diagnosed with primary and secondary syphilis in 4 US cities: New York City, Philadelphia, PA, Washington, DC, and Phoenix, AZ. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2015; 70:179–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kofoed K, Gerstoft J, Mathiesen LR, Benfield T. Syphilis and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-1 coinfection: influence on CD4 T-cell count, HIV-1 viral load, and treatment response. Sex Transm Dis 2006; 33:143–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park WB, Jang HC, Kim SH, et al. Effect of highly active antiretroviral therapy on incidence of early syphilis in HIV-infected patients. Sex Transm Dis 2008; 35:304–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ghanem KG, Moore RD, Rompalo AM, Erbelding EJ, Zenilman JM, Gebo KA. Antiretroviral therapy is associated with reduced serologic failure rates for syphilis among HIV-infected patients. Clin Infect Dis 2008; 47:258–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hopkins S, Bergin C, Mulcahy F. HIV status does not contribute to response to syphilis treatment. Int J STD AIDS 2009; 20:593; author reply 593–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jinno S, Anker B, Kaur P, Bristow CC, Klausner JD. Predictors of serological failure after treatment in HIV-infected patients with early syphilis in the emerging era of universal antiretroviral therapy use. BMC Infect Dis 2013; 13:605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spagnuolo V, Poli A, Galli L, et al. Predictors of lack of serological response to syphilis treatment in HIV-infected subjects. J Int AIDS Soc 2014; 17:19654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sadiq ST, McSorley J, Copas AJ, et al. The effects of early syphilis on CD4 counts and HIV-1 RNA viral loads in blood and semen. Sex Transm Infect 2005; 81:380–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Torrone EA, Bertolli J, Li J, et al. Increased HIV and primary and secondary syphilis diagnoses among young men—United States, 2004–2008. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2011; 58:328–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kalichman SC, Price D, Eaton LA, et al. Diminishing perceived threat of AIDS and increasing sexual risks of HIV among men who have sex with men, 1997–2015. Arch Sex Behav 2017; 46:895–902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paz-Bailey G, Mendoza MC, Finlayson T, et al. ; NHBS Study Group. Trends in condom use among MSM in the United States: the role of antiretroviral therapy and seroadaptive strategies. AIDS 2016; 30:1985–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grewal R, Allen VG, Gardner S, et al. ; OHTN Cohort Study Research Team. Serosorting and recreational drug use are risk factors for diagnosis of genital infection with chlamydia and gonorrhoea among HIV-positive men who have sex with men: results from a clinical cohort in Ontario, Canada. Sex Transm Infect 2017; 93:71–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khosropour CM, Dombrowski JC, Kerani RP, Katz DA, Barbee LA, Golden MR. Changes in condomless sex and serosorting among men who have sex with men after HIV diagnosis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2016; 73:475–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Truong HM, Truong HH, Kellogg T, et al. Increases in sexually transmitted infections and sexual risk behaviour without a concurrent increase in HIV incidence among men who have sex with men in San Francisco: a suggestion of HIV serosorting? Sex Transm Infect 2006; 82:461–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hotton AL, Gratzer B, Mehta SD. Association between serosorting and bacterial sexually transmitted infection among HIV-negative men who have sex with men at an urban lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health center. Sex Transm Dis 2012; 39:959–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kojima N, Davey DJ, Klausner JD. Pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV infection and new sexually transmitted infections among men who have sex with men. AIDS 2016; 30:2251–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marcus JL, Glidden DV, Mayer KH, et al. No evidence of sexual risk compensation in the iPrEx trial of daily oral HIV preexposure prophylaxis. PLoS One 2013; 8:e81997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Solomon MM, Mayer KH, Glidden DV, et al. ; iPrEx Study Team. Syphilis predicts HIV incidence among men and transgender women who have sex with men in a preexposure prophylaxis trial. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 59:1020–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stenger MR, Baral S, Stahlman S, Wohlfeiler D, Barton JE, Peterman T. As through a glass, darkly: the future of sexually transmissible infections among gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men. Sex Health 2017; 14:18–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]