Abstract

BACKGROUND

Variation in degenerative mitral morphology may contribute to suboptimal repair rates. This study evaluates outcomes of a standardized mitral repair technique.

METHODS

An institutional clinical registry was used to identify 1036 consecutive patients undergoing robotic mitral surgery between 2005 and 2020: 87% (n = 902) had degenerative disease. Calcification, failed transcatheter repair, and endocarditis were excluded, leaving 582 (68%) patients with isolated posterior leaflet and 268 (32%) with anterior or bileaflet prolapse. Standardized repair comprised triangular resection and true-sized flexible band in posterior leaflet prolapse. Freedom from greater than 2D moderate mitral regurgitation stratified by prolapse location was assessed using competing risk analysis with death as a competing event. Median follow-up was 5.5 (range 0–15) years.

RESULTS

Of patients with isolated posterior leaflet prolapse, 87% (n = 506) had standardized repairs and 13% (n = 76) had additional or nonresectional techniques vs 24% (n = 65) and 76% (n = 203), respectively, for anterior or bileaflet prolapse (P < .001). Adjunctive techniques in the isolated posterior leaflet group included chordal reconstruction (8.6%, n = 50) and commissural sutures (3.4%, n = 20). Overall, median clamp time was 80 (interquartile range, 68–98) minutes, 17 patients required intraoperative re-repair, and 6 required mitral replacement. Freedom from greater than 2D regurgitation or reintervention at 10 years was 92% for posterior prolapse (vs 83% for anterior or bileaflet prolapse). Anterior or bileaflet prolapse was associated with late greater than 2D regurgitation (hazard ratio, 3.0; 95% confidence interval, 1.3–7.0).

CONCLUSIONS

Posterior leaflet prolapse may be repaired in greater than 99% of patients using triangular resection and band annuloplasty, with satisfactory long-term durability. Increased risk of complex repairs and inferior durability highlights the value of identifying anterior and bileaflet prolapse preoperatively.

Individual surgeon and institutional repair rates for degenerative mitral regurgitation vary from near 100% to under 50%.1,2 A contributing factor is the wide variation in degenerative mitral morphology, which is characterized by a spectrum of lesions ranging from limited single segment prolapse in small valves, to large Barlow’s valves with multisegment bileaflet prolapse and leaflet redundancy.3 The lack of a standardized approach to mitral repair contributes to reduced repair rates and repair durability. This is particularly relevant to young patients, and patients without class I indications for surgical intervention such as symptoms, heart failure or left ventricular dysfunction, who are least well served by mitral valve replacement.4–6 This analysis was therefore designed to evaluate the outcomes and limitations of a standardized repair technique applied across the spectrum of degenerative mitral regurgitation.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

PATIENT POPULATION.

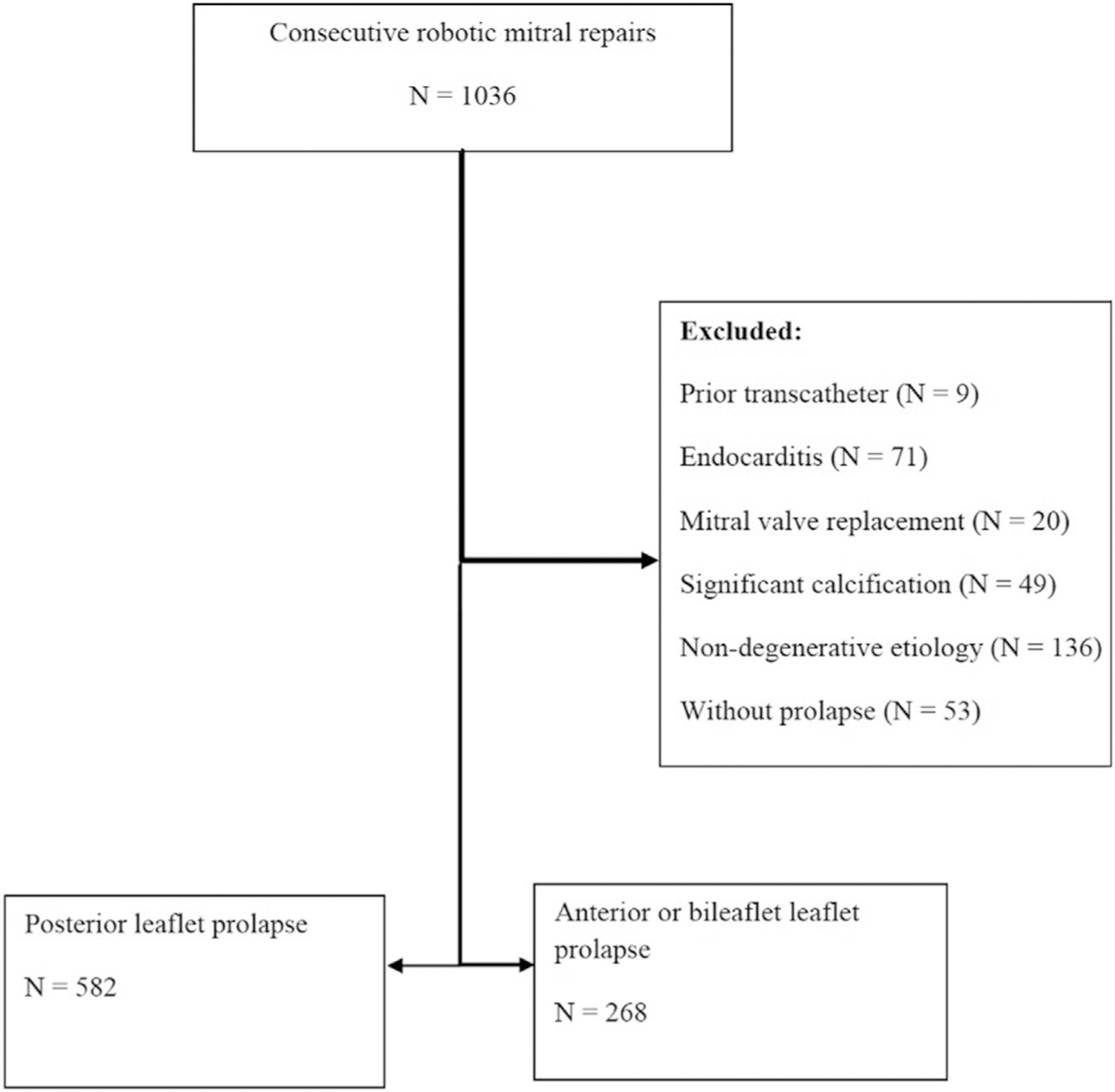

A retrospective cohort analysis was conducted on outcomes of 1036 consecutive patients undergoing robotic mitral surgery between 2005 and 2020 age 18 years or older, by 5 surgeons at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center. During this same 15-year time frame 129 patients by this same group of operating surgeons underwent sternotomy for degenerative mitral regurgitation with 100% repair rate. Of the patients that underwent sternotomies, 80% of these were done in the first 5 years of the study period; since then robotic surgery has become the default option for isolated degenerative mitral repair in patients without contraindications, specifically inability to tolerate single lung ventilation, significant mitral annular calcification, substantial aortic or femoral calcification on noncontrast computerized tomography, or more than moderate aortic insufficiency. Severe pectus deformity is a relative contraindication as visualization of the ascending aorta is challenging. From 1036 patients undergoing robotic mitral surgery, operative reports were used to identify 902 patients with degenerative mitral regurgitation. After excluding 186 (21%) patients with leaflet calcification (4.7%, n = 49), failed transcatheter repair (0.9%, n = 9), and endocarditis (6.9%, n = 71), 582 (68%) patients with isolated posterior leaflet vs 268 (32%) with anterior or bileaflet prolapse comprised the study cohort of 850 patients (Table 1, Figure 1). Baseline comorbidities, surgical details, and operative outcomes were identified using variables provided in The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Adult Cardiac Database (version 2.4–2.81), and individual patient chart review. This study was approved by the institutional review boards of Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, the California Department of Public Health, and the Office for State Public Health Departments of California. The approval included a waiver of informed consent.

TABLE 1.

Basic Demographics and Baseline Echocardiographic Findings Stratified by Location of Leaflet Prolapse

| Patient Characteristics | All Patients (n = 1036) | Posterior Prolapse (n = 582) | Anterior or Bileaflet Prolapse (n = 268) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 34 (352) | 28.2 (164) | 42.2 (113) | <.0001 |

| Age, y | 62 (53–69.1) | 61 (53–69) | 62 (54–70) | .59 |

| Age ≥80 y | 5.4 (56) | 5.5 (32) | 6.0 (16) | .78 |

| Hypertension | 48.2 (499) | 49 (285) | 42.9 (115) | .1 |

| Diabetes | 4.9 (51) | 5 (29) | 2.6 (7) | .11 |

| Coronary artery disease | 6.8 (66) | 6.6 (36) | 4.0 (10) | .15 |

| Prior myocardial infarction | 1.9 (20) | 0.5 (3) | 1.5 (4) | .11 |

| Prior stroke | 3 (31) | 1.2 (7) | 2.6 (7) | .13 |

| Recent atrial fibrillation or Atrial flutter | 23.8 (247) | 19.6 (114) | 29.9 (80) | .0009 |

| Ejection fraction | 62 (60–66) | 62 (60–66) | 62 (58–66) | .14 |

| Moderate or greater tricuspid regurgitation | 23.9 (229) | 22 (119) | 23.4 (59) | .67 |

Values are % (n) or median (interquartile range).

FIGURE 1.

CONSORT diagram showing characteristics of included and excluded patients.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE.

The intention in all patients was to perform a mitral repair: consequently, the replacements in this series represent intraoperative conversion to replacement after failed attempt at repair, major intraoperative complication, or unanticipated pathology (eg, leaflet calcification). Standardized mitral repair was defined as a true-sized flexible annuloplasty band with simple triangular posterior leaflet resection performed using the same sequence of steps without sliding plasty or other adjunctive techniques. Quadrangular resection was occasionally used, almost exclusively in the early phase of the study period. This technique has been previously described in detail.7 After leaflet repair any additional or residual prolapse was evaluated by direct inspection and a saline test, which was also repeated after annuloplasty. Adjunctive and alternative techniques used according to the presence of residual prolapse included chordal transfer, neochords, edge-to-edge repair, and commissural sutures. All procedures were performed via a 5- to 8- cm right thoracotomy with robotic assistance, under del Nido cardioplegic arrest instituted on cardiopulmonary femorofemoral bypass with a Chitwood clamp (an endoclamp was used for 5 cases early in the experience). There were 5 operating surgeons during this time frame. Robotic mitral repair was established by 1 surgeon (A.T.) who performed 92.7% (n = 788) of the operations in this series and trained the other 4 surgeons, 3 of whom performed 7.3% (n = 62) of the operations in this series. It is our routine practice for robotic cases to be performed by 2 attending surgeons to maximize team experience: consequently, all robotic surgeons at our institution have each participated in over 150 robotic mitral repairs.

PRIMARY AND SECONDARY OUTCOMES.

The primary outcome was freedom from greater than 2+ mitral regurgitation or reintervention. Secondary outcomes included all-cause mortality, residual and recurrent mitral regurgitation, neurological complications (stroke or transient ischemia), respiratory failure requiring reintubation, renal failure requiring dialysis, any cardiac reoperation, and any reoperation for bleeding. Permanent stroke was defined according to The Society of Thoracic Surgeons criteria as any confirmed neurological deficit of abrupt onset caused by a disturbance in blood supply to the brain that did not resolve within 24 hours.

FOLLOW-UP.

All patients were prospectively followed annually with structured phone surveys. Mortality data for the cohort were obtained from national vital statistics death records, with record linkage by Social Security number. Echocardiogram reports were obtained from cardiology and primary care physicians. Additionally, statewide mandatory discharge and vital statistics databases linked with the hospital registry were used to identify any statewide postoperative hospital admission and deaths in 651 of 719 patients with social security numbers and state administrative data. Record linkage to the Office for State Public Health Departments of California was performed using probabilistic linkage with the following variables: birth date, patient zip code, admission date, discharge date, race, and sex, with successful linkage of 90% of patients. Median clinical follow-up was 100% complete with duration of 5.5 (range 0–15) years, and median echocardiographic follow-up was 1.7 (range 0–15) years and 94% complete (date of last follow-up: January 30, 2021): 652 (77%) patients had institutional echocardiographic follow-up, 151 (17.8%) had outside echocardiographic report follow-up, and 5.5% lacked echocardiographic follow-up.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS.

For descriptive analysis, continuous variables were reported as mean ± or median (interquartile range [IQR]) depending on distribution, and categorical variables were reported as proportions. For continuous variables with missing data, observations with less than 1% of missing data were excluded from analysis. Categorical variables missing less than 5% were marked as unknown, and eliminated if greater than 5% were missing. The Student’s t test or Wilcoxon ranksum test for continuous variables and chi-square test were used as appropriate to compare demographics and operative techniques according to prolapse groups. We used competing risk analysis with death as a competing event for analysis of freedom from greater than 2+ mitral regurgitation, recurrent mitral regurgitation, or mitral reintervention. The Cox proportional hazards model was used to identify risk factors associated with freedom from greater than 2+ mitral regurgitation or reintervention. In multivariable analysis we controlled for mitral morphology, age, sex, baseline comorbidities, and the repair technique. Variables with P values of less than .1 in the initial model (Supplemental Table 1) were entered into the final model and included age, sex, prolapse location, and surgery year. Proportional hazards assumption was checked using Martingale residuals and was not violated. All tests were 2-tailed, and an alpha level of 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

STUDY POPULATION.

A total of 850 patients (median age 62 [IQR, 53–69] years), 67% (n = 573) male met the study inclusion criteria, of whom 582 (68%) had isolated posterior leaflet prolapse. Patient characteristics stratified by leaflet morphology are shown in Table 1. Patients with isolated posterior leaflet prolapse were more likely to be male (72%, n = 418) compared with those with anterior leaflet prolapse (58%, n = 155), and recent atrial fibrillation was significantly less common in patients with posterior leaflet prolapse (20%, n = 114) compared with anterior or bileaflet prolapse (30%, n = 80). There were no other significant differences in baseline characteristics between the study groups.

OPERATIVE OUTCOMES.

Operative approaches are summarized in Table 2. A total of 87% (n = 506) patients underwent standardized repair, and 7% (n = 39) required additional techniques, vs 24% (n = 65) and 41% (n = 109), respectively, for patients without isolated posterior leaflet prolapse (P < .001). Triangular resection was the predominant technique used, representing 78% (n = 666 of 850) patients in the latter phase of the study period. Adjunctive and alternate techniques included neochords (16%, n = 138), commissural sutures (11%, n = 94), and chordal transfer (8%, n = 65) (Table 2). Median clamp time was 76 (IQR, 66–93) minutes in the isolated posterior prolapse group vs 85 minutes (IQR, 74 to 104) minutes in the anterior or bileaflet group. A second clamp time was needed in 17 patients for re-repair, including 11 for repair of residual greater than 2+ mitral regurgitation: 3 patients required removal or revision of neochords, 3 required additional sutures to the leaflet closure line, 1 mitral replacement was performed, 1 patient required removal of sutures to address circumflex territory ischemia, and 1 aortic valve replacement was performed for aortic insufficiency. One patient in the isolated posterior leaflet prolapse group had abnormal systolic anterior motion documented on postbypass transesophageal echocardiography, which subsequently resolved with pharmacological management, without revision of the repair. No patients had second clamp times for abnormal systolic anterior leaflet motion, and no other patients had systolic anterior motion on postbypass transeophageal echocardiography or posoperative echocardiography that remained on follow-up. Mitral valve replacements were performed for 6 patients: these were unplanned, and performed for unanticipated leaflet calcification (n = 3), failure to achieve a competent repair despite second clamp time (n = 2), and ventricular rupture after repair (n = 1). Three patients required conversion to median sternotomy, 1 for repair of right ventricle laceration, 1 for iatrogenic aortic dissection, and 1 for impaired visibility due to pectus deformity. When analyzed by individual surgeon, there were no significant differences in the proportion of isolated posterior vs bileaflet or anterior leaflet prolapse, or the repair techniques: the primary surgeon performed isolated resections with band annuloplasty in 67% (n = 528 of 788) of patients compared with 69.4% (n = 43 of 62) of patients for the other surgeons.

TABLE 2.

Operative Techniques Stratified by Location of Leaflet Prolapse

| Variable | All Patients (n = 1036) | Posterior Prolapse (n = 582) | Anterior or Bileaflet Prolapse (n = 268) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Operative techniques | ||||

| Triangular resection | 73.4 (760) | 87.1 (507) | 59.3 (159) | <.0001 |

| Quadrangular resection | 5.6 (58) | 6.5 (38) | 5.6 (15) | .6 |

| Isolated resection with band | 61.6 (638) | 24.3 (65) | 86.9 (506) | <.0001 |

| Neochords | 15.6 (162) | 4.8 (28) | 41 (110) | <.0001 |

| Chordal transfer | 7.2 (75) | 3.8 (22) | 16 (43) | <.0001 |

| Commissural suture | 11.4 (118) | 3.4 (20) | 27.6 (74) | <.0001 |

| Edge-to-edge repair | 0.1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0.37 (1) | .32 |

| Band size, mm | 35 (33–37) | 35 (33–37) | 37 (35–39) | <.0001 |

| Concomitant procedure | ||||

| Left atrial appendage closure | 61.7 (639) | 61.5 (358) | 67.5 (181) | .09 |

| Cryomaze | 20.4 (211) | 17 (99) | 23.5 (63) | .025 |

| Patent foramen ovale closure | 15.4 (159) | 15.6 (91) | 17.5 (47) | .48 |

| Tricuspid annuloplasty | 6.2 (64) | 5.7 (33) | 6.3 (17) | .7 |

| Operative times | ||||

| Clamp time, min | 80 (68–98) | 76 (66–93) | 85 (74–104) | <.0001 |

| Bypass time, min | 122 (107–145) | 118 (105–138) | 130 (113–150) | <.0001 |

Values are % (n) or median (interquartile range).

CLINICAL OUTCOMES.

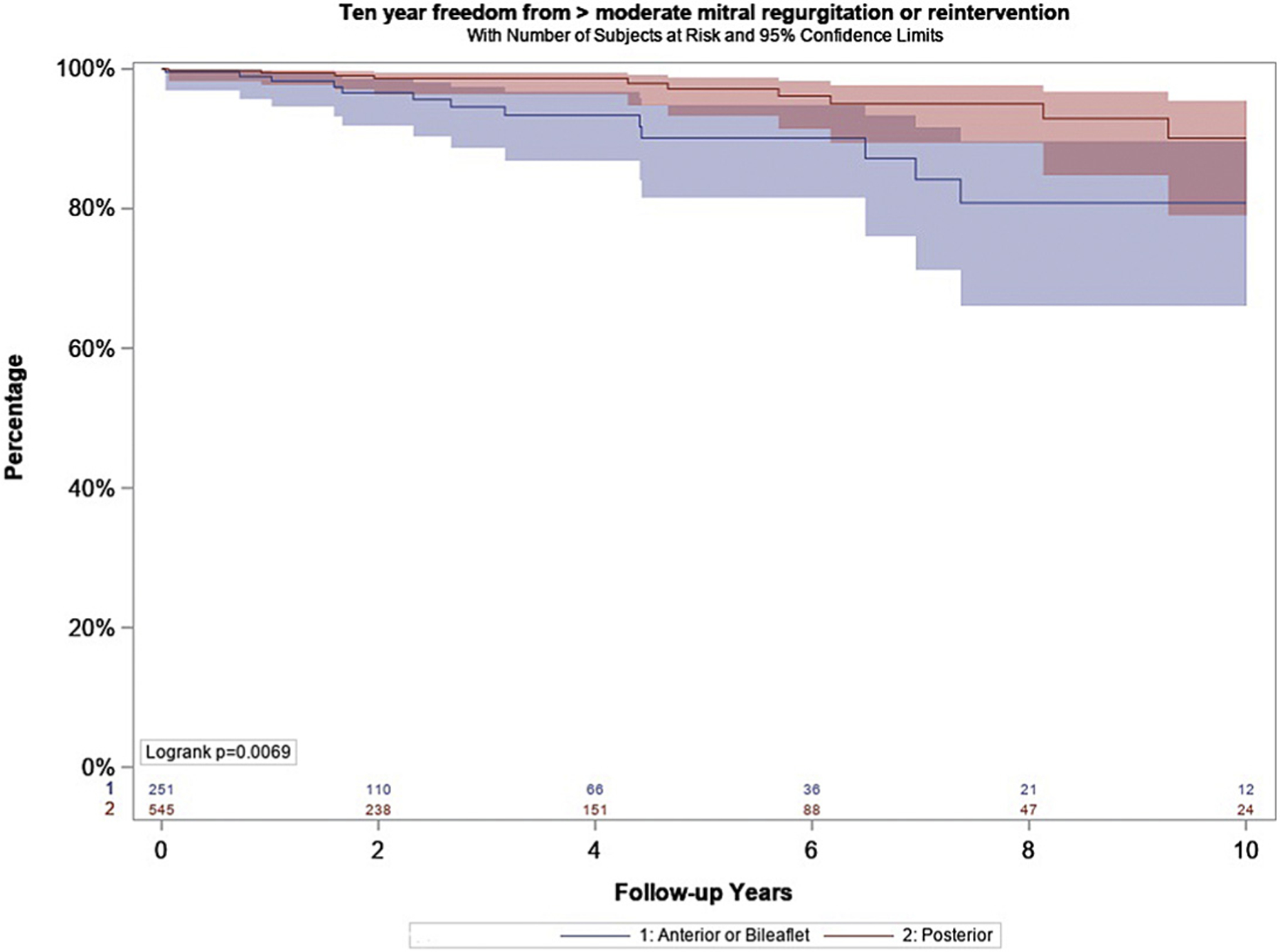

The incidence of 30-day or in-hospital mortality was 0.4% (n = 4). Freedom from all-cause mortality at 10-year follow-up was 91% (95% confidence interval [CI], 87%−94%) in the isolated posterior leaflet group vs 87% (95% CI, 78%−93%) in the anterior or bileaflet group (P = .19). Operative morbidity is shown in Table 3. Unadjusted 10-year freedom from greater than 2+ moderate regurgitation or reintervention was 91% for patients with isolated posterior leaflet prolapse vs 83% for anterior or bileaflet prolapse (Figure 2). In long-term follow-up of the entire cohort, 23 patients underwent repeat surgical or transcatheter mitral intervention, 17 patients after exclusion criteria. Mean time to reintervention was 2.6 years (range 22 days to 10.3 years) with reintervention including 3 MitraClips (Abbott Vascular, Santa Clara, CA), 4 redo repairs (1 went on to later require replacement), and 10 replacements. In multivariate analysis, anterior or bileaflet leaflet prolapse was a significant predictor of late moderate regurgitation (hazard ratio, 3.0; 95% CI, 1.3–7). Freedom from progression to greater than 2+ moderate regurgitation or reintervention with mortality as a competing risk was 92.4% (95% CI, 85.5%−96.7%) for isolated posterior prolapse vs 84.3% (95% CI, 73.9%−92.2%) for anterior or bileaflet prolapse (P = .005). Repair durability improved with experience across the study period, with earlier surgery year associated with late moderate regurgitation (hazard ratio, 1.3; 95% CI, 1.1–1.5) (Table 4).

TABLE 3.

Operative Outcomes Stratified by Location of Leaflet Prolapse

| All Patients (n = 1036) | Posterior Prolapse (n = 582) | Anterior or Bileaflet Prolapse (n = 268) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In-hospital mortality | 0.3 (3) | 0 (0) | 0.37 (1) | .32 |

| Morbidity | ||||

| Stroke | 1 (10) | 1.2 (7) | 0.37 (1) | .18 |

| Transient ischemic attack | 0.1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 |

| Reintubation | 1.2 (12) | 0.86 (5) | 0.75 (2) | 1 |

| Renal failure requiring dialysis | 0.5 (5) | 0.17 (1) | 0.75 (2) | .23 |

| Reoperation for bleeding | 1.8 (19) | 1.9 (11) | 0.37 (1) | .12 |

| Index hospitalization reoperation for valvular dysfunction | 0.4 (4) | 0.17 (1) | 0.17 (1) | .53 |

| Sepsis | 0.2 (2) | 0 (0) | 0.37 (1) | .32 |

| Length of stay, d | 5 (4.6–6.5) | 5 (4.5–6) | 5 (5–6) | .36 |

Values are % (n) or median (interquartile range).

FIGURE 2.

Unadjusted incidence rates of freedom from > 2 + moderate mitral regurgitation or reintervention stratified by location of leaflet prolapse.

TABLE 4.

Factors Associated with >2+ Residual or Recurrent Mitral Regurgitation

| Parameter | Value | P Value | Hazard Ratio | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prolapse location | Anterior or bileaflet | .0096 | 3.04 | 1.311–7.053 |

| Female | No | .018 | 3.734 | 1.254–11.123 |

| Surgery Year | … | .0113 | 1.274 | 1.056–1.536 |

| Age | … | .0182 | 1.048 | 1.008–1.09 |

CI, confidence interval.

COMMENT

This analysis demonstrates firstly that degenerative mitral regurgitation caused by a wide spectrum of posterior leaflet morphology can be repaired reliably and durably in around 90% of cases with a relatively simple standardized technique consisting of a true-sized flexible annuloplasty band and triangular leaflet resection without adjunctive techniques. Second, these data suggest that this standardized approach may allow robotic-assisted and less invasive mitral repair to be performed with acceptable early and midterm clinical and echocardiographic outcomes. Finally, increased need for adjunctive techniques and poorer long-term outcomes seen in patients with bileaflet and anterior leaflet prolapse highlights the importance of identifying this patient population preoperatively in order to tailor surgical strategy.

ISOLATED POSTERIOR LEAFLET PROLAPSE.

In the cohort of over 500 with isolated posterior leaflet prolapse, 5 surgeons were able to achieve a competent repair in over 99% of cases, with greater than 2+ mitral regurgitation observed in fewer than 9% of patients at 10 years using a flexible annuloplasty and simple leaflet resection, without adjunctive techniques. Long-term freedom from significant mitral regurgitation in these patients was comparable to that achieved with more complex reconstructive strategies such as routine sliding plasty with quadrangular resection, or more frequent and extensive use of chordal, commissural, and cleft closure repair techniques.8–10 Careful patient selection informed by echocardiographic and direct inspection is an important part of applying a standardized surgical strategy. For example, the presence of multiple jets on echocardiography may indicate additional lesions that may not be addressed by simple leaflet resection. Importantly, careful direct inspection to identify normal supporting chords that define the boundaries of the leaflet resection,and precise repair of the resected margins to ensure a smooth coaptation zone is essential. Intraoperative saline testing is helpful to identify residual prolapse; however, the goal is not aggressively pressurizing the ventricle because distension in diastole does not provide a true physiologic assessment of mitral competency.

We observed anterior or bileaflet leaflet prolapse to be associated with increased risk of moderate mitral regurgitation or reintervention in long-term follow-up. More than half of these patients required adjunctive techniques, primarily chordal reconstruction with GORE-TEX (W. L. Gore and Associates, Newark, DE) neochords or occasionally chordal transfer, and commissural sutures to achieve satisfactory repairs. Our findings confirm the results of several other series, underlining the importance of identifying anterior leaflet prolapse preoperatively.10–13 This is because, depending on individual surgeon experience, the presence of anterior leaflet prolapse may inform consent regarding the feasibility, the durability, and potentially the timing of repair particularly in patients without class I indications for surgery. For example, current consensus statements suggest degenerative patients requiring anterior or bileaflet prolapse repair may benefit from referral to comprehensive (level 1) valve centers able to offer additional expertise, experience and resources compared with primary (level 2) valve centers.4–6 These consensus documents suggest that individual surgeon case volume thresholds for defining expertise in this context are an annual minimum of 25 mitral cases and additionally note that improved outcomes have been reported at centers with surgeons that have an individual annual case volume over 50 based on a multicenter analysis that correlated repair rates and repair durability with higher individual surgeon case volume.1,4–6

OTHER TECHNICAL CONSIDERATIONS.

We attribute the less than 1% incidence of abnormal systolic motion in our series to a strategy of using true-sized flexible annuloplasty bands measured and implanted from commissure to commissure (not trigone to trigone). This contrasts with the incidence of systolic anterior motion of 5% to 15% reported in series using a wide variety of repair techniques: it remains to be seen whether this difference in repair strategy impacts long-term repair durability.14–16 Broadly, reliable, simple repair techniques greatly facilitate mitral repair including through small incisions. The advantages of robotic assistance including substantially improved visualization and ability to work through potentially smaller nonsternotomy incisions come with constraints including loss of tactile feedback that is partially compensated for by enhanced visual feedback. Consequently, economy of movement becomes a more important factor in the efficiency with which a repair may be carried out. These data suggest that standardizing mitral repair technique facilitates economies of movement that mean robotic repair may be performed reliably, and without excessively long clamp times.

LIMITATIONS.

The main advantages of this analysis are that a single-institution dataset with prospective echocardiographic follow-up and linkage to statewide registries allows detailed analysis of operative techniques and outcomes used by 5 surgeons. The main limitation of the analysis is the relatively small number of echocardiograms routinely available in long-term follow-up: a higher proportion of late echocardiograms may be symptom driven, which reduces the ability to draw conclusions about the long-term outcomes of this strategy, particularly repair durability, which may be underestimated. Additionally, 18% of our echocardiographic follow-up was obtained from outside our institution: substantial variability has been documented in the quality and reliability of echocardiography, which may have affected the accuracy with which we detected recurrent mitral regurgitation, and data on leaflet coaptation and gradients was missing in 15% of late echocardiograms in this series.17 Although this is a standardized approach with a simple technical component, the success depends on accurate assessment of valve morphology, which requires experience. Next, although this study was linked to statewide admission and discharge database, we cannot assure that these patients had reoperations or procedures out of state. One way that this was addressed was using our routine annual clinical follow-up survey to try to capture as many of these out-of-state procedures as possible. Finally, it is conceivable that referral bias may have played a role distributing mitral pathology most amenable to repair within this cohort. This seems unlikely given the prevalence of anterior and bileaflet pathology in this series is similar to that reported in other single center series, and multicenter registries including The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Database.9–13,18

CONCLUSION.

Almost all posterior leaflet prolapse morphology may be effectively repaired using a 2-step technique consisting of isolated triangular or quadrangular leaflet resection with true-sized flexible annuloplasty, without abnormal systolic anterior motion or residual mitral regurgitation. Correctly applied, this simple standardized strategy may improve degenerative repair rates and durability, and facilitate minimally invasive approaches. The increased prevalence of complex repairs with inferior durability highlights the value of identifying anterior leaflet prolapse preoperatively so that surgical strategy can be appropriately modified. Furthermore, this series highlights the importance of established surgeons when adopting new surgical practices especially when mitral pathology involves anterior or bileaflet prolapse.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by an Advanced Heart Disease Research National Institutes of Health training grant (NIH grant T32HL116273).

Footnotes

Presented at the Fifty-seventh Annual Meeting of The Society of Thoracic Surgeons, Virtual Meeting, Jan 29–31, 2021.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chikwe J, Toyoda N, Anyanwu AC, et al. Relation of mitral valve surgery volume to repair rate, durability, and survival. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;69: 2397–2406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Badhwar V, Vemulapalli S, Mack MA, et al. Volume-outcome association of mitral valve surgery in the United States. JAMA Cardiol 2020;5:1092–1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adams DH, Rosenhek R, Falk V. Degenerative mitral valve regurgitation: best practice revolution. Eur Heart J 2010;31:1958–1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Otto C, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA Guideline for the Management of Patients with Valvular Heart Disease. A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2021;77:450–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonow RO, Gara PT, Adams DH, et al. 2020 Focused Update of the 2017 ACC Expert Consensus Decision pathway on the Management of Mitral Regurgitation. A Report of the American College of Cardiology Solution Set Oversight Committee. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020;75:2236–2270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nishimura RA, O’Gara PT, Bavaria JE, et al. 2019 AATS/ACC/ASE/SCAI/STS Expert Consensus Systems of Care Document: A Proposal to Optimize Care for Patients With Valvular Heart Disease: A Joint Report of the American Association for Thoracic Surgery, American College of Cardiology, American Society of Echocardiography, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and The Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Ann Thorac Surg 2019;107:1884–1910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramzy D, Trento A, Cheng W, et al. Three hundred robotic-assisted mitral valve repairs: the Cedars-Sinai experience. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2014;147:228–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gardner MA, Hossack KF, Smith IR. Long-term results following repair for degenerative mitral regurgitation-analysis of factors influencing durability. Heart Lung Circ 2019;28:1852–1865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.David TE, Armstrong S, McCrindle BW, Manlhiot C. Late outcomes of mitral valve repair for mitral regurgitation due to degenerative disease. Circulation. 2013;127:1485–1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lazam S, Vanoverschelde JL, Tribouilloy C, et al. Twenty-year outcome after mitral repair versus replacement for severe degenerative mitral regurgitation: analysis of a large, prospective, multicenter, international registry. Circulation. 2017;135:410–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suri RM, Schaff HV, Dearani JA, et al. Survival advantage and improved durability of mitral repair for leaflet prolapse subsets in the current era. Ann Thorac Surg 2006;82:819–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Speziale G, Moscarelli M, Di Bari N, et al. A simplified technique for complex mitral valve regurgitation by a minimally invasive approach. Ann Thorac Surg 2018;106:728–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Borger MA, Kaeding AF, Seeburger J, et al. Minimally invasive mitral valve repair in Barlow’s disease: early and long-term results. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2014;148:1379–1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ashikhmina E, Schaff HV, Daly RC, et al. Risk factors and progression of systolic anterior motion after mitral valve repair. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2021;162:567–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Loulmet D, Yaffee DW, Aursomanno PA, et al. Systolic anterior motion of the mitral valve: a 30-year perspective. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2014;148:2787–2793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Varghese R, Anyanwu AC, Itagaki S, Milla F, Castillo J, Adams DH. Management of systolic anterior motion after mitral valve repair: an algorithm. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2012;143:S2–S7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thaden JJ, Tsang MY, Ayoub C, et al. Association between echocardiography laboratory accreditation and the quality of imaging and reporting for valvular heart disease. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017;10:e006140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gammie JS, Chikwe J, Badhwar V, et al. isolated mitral valve surgery: The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Adult Cardiac Surgery Database analysis. Ann Thorac Surg 2018;106:716–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.