Abstract

Background

Bacterial vaginosis is an imbalance of the normal vaginal flora with an overgrowth of anaerobic bacteria and a lack of the normal lactobacillary flora. Women may have symptoms of a characteristic vaginal discharge but are often asymptomatic. Bacterial vaginosis during pregnancy has been associated with poor perinatal outcomes and, in particular, preterm birth (PTB). Identification and treatment may reduce the risk of PTB and its consequences.

Objectives

To assess the effects of antibiotic treatment of bacterial vaginosis in pregnancy.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register (31 May 2012), searched cited references from retrieved articles and reviewed abstracts, letters to the editor and editorials.

Selection criteria

Randomised trials comparing antibiotic treatment with placebo or no treatment, or comparing two or more antibiotic regimens in pregnant women with bacterial vaginosis or intermediate vaginal flora whether symptomatic or asymptomatic and detected through screening.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed trials for inclusion, trial quality and extracted data. We contacted study authors for additional information.

Main results

We included 21 trials of good quality, involving 7847 women diagnosed with bacterial vaginosis or intermediate vaginal flora.

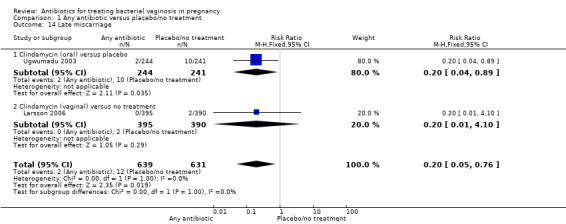

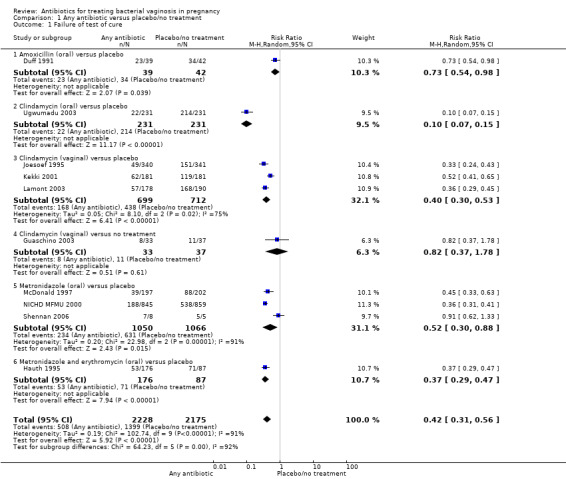

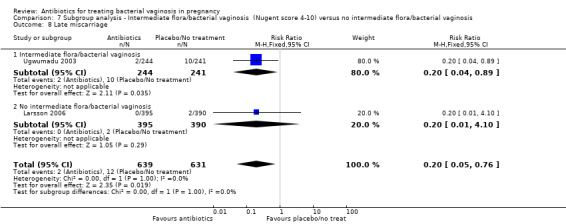

Antibiotic therapy was shown to be effective at eradicating bacterial vaginosis during pregnancy (average risk ratio (RR) 0.42; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.31 to 0.56; 10 trials, 4403 women; random‐effects, T² = 0.19, I² = 91%). Antibiotic treatment also reduced the risk of late miscarriage (RR 0.20; 95% CI 0.05 to 0.76; two trials, 1270 women, fixed‐effect, I² = 0%).

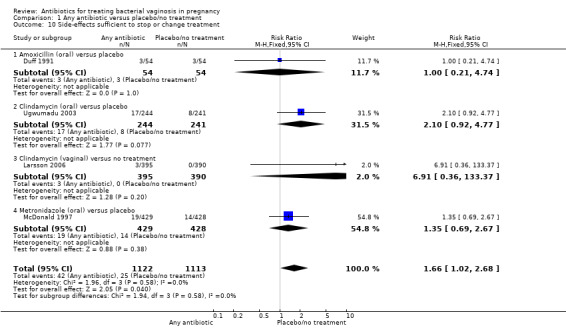

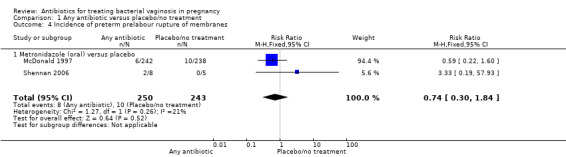

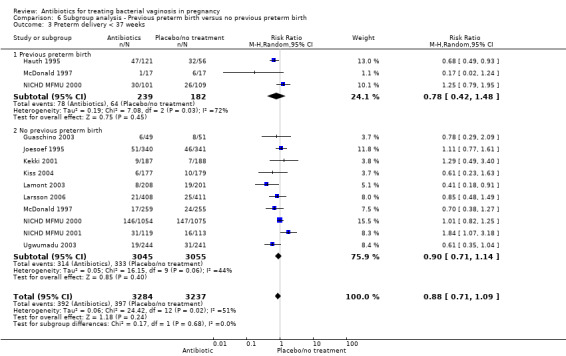

Treatment did not reduce the risk of PTB before 37 weeks (average RR 0.88; 95% CI 0.71 to 1.09; 13 trials, 6491 women; random‐effects, T² = 0.06, I² = 48%), or the risk of preterm prelabour rupture of membranes (RR 0.74; 95% CI 0.30 to 1.84; two trials, 493 women). It did increase the risk of side‐effects sufficient to stop or change treatment (RR 1.66; 95% CI 1.02 to 2.68; four trials, 2323 women, fixed‐effect, I² = 0%).

In this updated review, treatment before 20 weeks' gestation did not reduce the risk of PTB less than 37 weeks (average RR 0.85; 95% CI 0.62 to 1.17; five trials, 4088 women; random‐effects, T² = 0.06, I² = 49%).

In women with a previous PTB, treatment did not affect the risk of subsequent PTB (average RR 0.78; 95% CI 0.42 to 1.48; three trials, 421 women; random‐effects, T² = 0.19, I² = 72%).

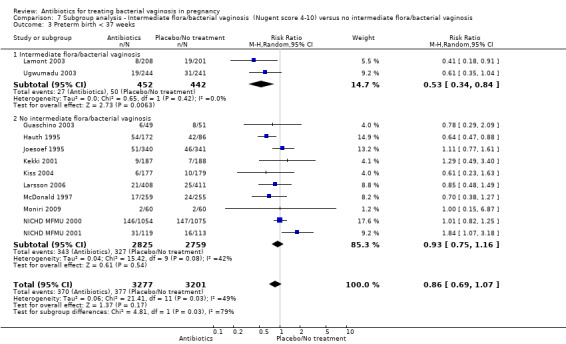

In women with abnormal vaginal flora (intermediate flora or bacterial vaginosis), treatment may reduce the risk of PTB before 37 weeks (RR 0.53; 95% CI 0.34 to 0.84; two trials, 894 women).

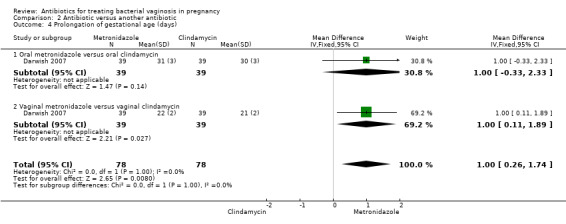

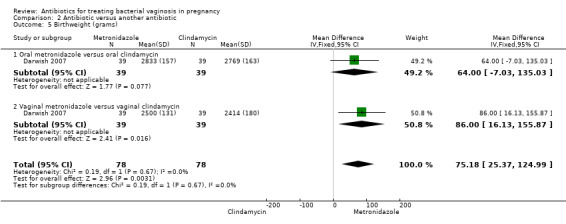

One small trial of 156 women compared metronidazole and clindamycin, both oral and vaginal, with no significant differences seen for any of the pre‐specified primary outcomes. Statistically significant differences were seen for the outcomes of prolongation of gestational age (days) (mean difference (MD) 1.00; 95% CI 0.26 to 1.74) and birthweight (grams) (MD 75.18; 95% CI 25.37 to 124.99) however these represent relatively small differences in the clinical setting.

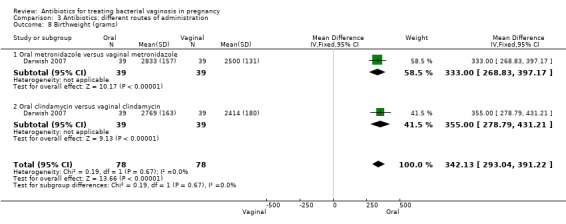

Oral antibiotics versus vaginal antibiotics did not reduce the risk of PTB (RR 1.09; 95% CI 0.78 to 1.52; two trials, 264 women). Oral antibiotics had some advantage over vaginal antibiotics (whether metronidazole or clindamycin) with respect to admission to neonatal unit (RR 0.63; 95% CI 0.42 to 0.92, one trial, 156 women), prolongation of gestational age (days) (MD 9.00; 95% CI 8.20 to 9.80; one trial, 156 women) and birthweight (grams) (MD 342.13; 95% CI 293.04 to 391.22; one trial, 156 women).

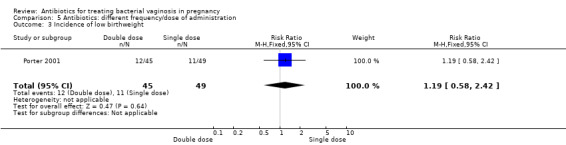

Different frequency of dosing of antibiotics was assessed in one small trial and showed no significant difference for any outcome assessed.

Authors' conclusions

Antibiotic treatment can eradicate bacterial vaginosis in pregnancy. The overall risk of PTB was not significantly reduced. This review provides little evidence that screening and treating all pregnant women with bacterial vaginosis will prevent PTB and its consequences. When screening criteria were broadened to include women with abnormal flora there was a 47% reduction in preterm birth, however this is limited to two included studies.

Keywords: Female; Humans; Pregnancy; Anti‐Bacterial Agents; Anti‐Bacterial Agents/therapeutic use; Fetal Membranes, Premature Rupture; Fetal Membranes, Premature Rupture/prevention & control; Pregnancy Complications, Infectious; Pregnancy Complications, Infectious/drug therapy; Premature Birth; Premature Birth/prevention & control; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Vaginosis, Bacterial; Vaginosis, Bacterial/drug therapy

Plain language summary

Antibiotics for treating bacterial vaginosis in pregnancy

Bacteria are normally present in the birth canal and are useful in maintaining the health of the vagina. However, if the numbers of some of the bacteria increase, this is called bacterial vaginosis. For some women, there are no symptoms but for others it may cause an unpleasant discharge and may cause some babies to be born too early. These babies can suffer from problems related to their immaturity both in the weeks following birth such as breathing difficulty, infection and bleeding within the brain as well as problems when growing up such as poor growth, chronic lung disease and delayed development.

The review looked to see whether the use of antibiotics in women with bacterial vaginosis reduced the symptoms for women and reduced the incidence of babies being born too early. We identified 21 trials, involving 7847 women. We found that antibiotics given to pregnant women reduced this overgrowth of bacteria, but did not reduce the numbers of babies who were born too early. There were adverse effects sufficient to stop treatment or have the treatment changed when antibiotics were used and this needs further investigation. The effect of screening and treating women with abnormal flora needs to be studied in further trials and the effects of screening and treating proven vaginal infections is the subject of another Cochrane review.

Background

Description of the condition

Bacterial vaginosis is an imbalance of vaginal flora caused by a reduction of the normal lactobacillary bacteria, and a heavy overgrowth of mixed anaerobic flora including Gardnerella vaginalis, Mycoplasma hominis and Mobiluncus species. Why these organisms multiply, many of which are normally present in small numbers in the vagina, while the usually prevalent lactobacilli decrease, is not clear. The role of hydrogen peroxide‐producing lactobacilli appears to be important in preventing overgrowth of anaerobes in normal vaginal flora (Hillier 1993). Bacterial vaginosis does not appear to be sexually transmitted but may be associated with sexual activity.

Bacterial vaginosis is often asymptomatic but may result in a vaginal discharge which can be grey in colour with a characteristic 'fishy' odour. It is not associated with vaginal mucosal inflammation and rarely causes vulval itch.

The classical diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis is confirmed by fulfilling three out of four criteria (Amsel 1983). These are (i) a vaginal pH greater than 4.7, (ii) the presence of 'clue cells' on a Gram stain or wet mount of the vaginal discharge, (iii) the presence of a thin homogenous discharge and (iv) the release of a fishy odour when potassium hydroxide is added to a sample of the discharge. The use of these criteria for diagnosis, however, is complex and time consuming in some settings. Use of a Gram stain of a vaginal swab with semi‐quantification of the microbial flora has high sensitivity and specificity and is an accepted alternative method which has been used in many studies due to ease of standardisation, ability to be read at a later date and potential to be blinded (Nugent 1991). In the Nugent system, the numbers of different bacterial morphotypes in Gram stained smears are counted in high power fields using microscopy with a 1000x magnification. The points achieved from the number of different bacterial morphotypes are added together, with a total score of zero to three considered normal and a score of seven to 10 consistent with bacterial vaginosis. A score of four to six is classified as intermediate.

Natural history in pregnancy

Bacterial vaginosis is present in up to 20% of women during pregnancy (Lamont 1993). The majority of these cases will be asymptomatic. The natural history of bacterial vaginosis is such that it may spontaneously resolve without treatment although most women identified as having bacterial vaginosis in early pregnancy are likely to have persistent infection later in pregnancy (Hay 1994).

Association with adverse outcomes

There is now a substantial body of evidence associating bacterial vaginosis in pregnancy with poor perinatal outcome, in particular an increased risk of preterm birth (Hay 1994a; Hillier 1995; Kurki 1992; McGregor 1990), with potential neonatal sequelae due to prematurity. A recent meta‐analysis of adverse outcomes associated with bacterial vaginosis and including over 30,000 women from 32 studies (Leitich 2007) showed that bacterial vaginosis approximately doubled the risk of preterm delivery in asymptomatic patients (odds ratio (OR) 2.16, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.56 to 3.00) as well as significantly increased the risks of late miscarriage (OR 6.32, 95% CI 3.65 to 10.94) and maternal infection (OR 2.53, 95% CI 1.26 to 5.08). There is also evidence associating intermediate flora with adverse pregnancy outcome (Donders 2009; Hay 1994a; Leitich 2007). Although intra‐amniotic infection has a clear causal relationship with preterm delivery mediated via pattern recognition receptors, chemokines or inflammatory cytokines (Lamont 2011b), the exact mechanism by which by which the organisms associated with bacterial vaginosis may effect the initiation of preterm labour remains unclear. It is also unclear why bacterial vaginosis is associated with preterm birth in some women but not in others with recent studies suggesting individual immune responses (Jones 2010; Lamont 2011a) or specific gene polymorphisms (Annells 2004; Annells 2005; Simhan 2003; Witkin 2003) are responsible for individual susceptibility. Whilst a number of other genital micro‐organisms such as Escherichia coli, Listeria monocytogenes and Viridans streptococci may be involved in chorioamnionitis, carriage of these organisms during early to mid‐pregnancy has not been associated with an increased risk of preterm labour. Although maternal carriage of group B Streptococcus increases the risk of neonatal sepsis due to this organism, there is conflicting evidence about whether carriage during pregnancy increases the risk of preterm birth. Infections during pregnancy for which there is good evidence of an increased risk of preterm birth and preterm prelabour rupture of the membranes, include asymptomatic bacteriuria, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis, Trichomonas vaginalis and bacterial vaginosis. The opportunity therefore exists to reduce the preterm birth rate by treatment of these infections during pregnancy.

Description of the intervention

Antibiotics used to treat bacterial vaginosis cover anaerobic organisms. Different antibiotics have differing specificity for the organisms present. Commonly used antibiotics for bacterial vaginosis are metronidazole and clindamycin.

How the intervention might work

Antibiotic treatment aims to reduce the overgrowth of the abnormal anaerobic bacteria, restore the balance of the protective lactobacillary bacteria and prevent the development of an inflammatory response and the initiation of preterm labour.

Why it is important to do this review

Bacterial vaginosis is relatively common, even in populations of women at low risk of adverse events and it is amenable to treatment (Burtin 1995; Fischbach 1993; McDonald 1994). Identification during pregnancy and treatment may present a rare opportunity to reduce the preterm birth rate, and resulting risk of prematurity to the newborn. Such treatment may also reduce other adverse perinatal outcomes such as postpartum infection. Much evidence exists to support the association of bacterial vaginosis with preterm birth, however, the exact underlying mechanisms remain unclear. The results of randomised controlled trials of treatment are needed to provide more direct evidence of the role of bacterial vaginosis in preterm birth.

Objectives

To determine whether the use of antibiotics for bacterial vaginosis in pregnancy can: (a) improve maternal symptoms; (b) decrease incidence of adverse perinatal outcomes.

To determine if antibiotics are helpful and which antibiotic regimens are the most effective.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All randomised controlled trials that compare (i) one antibiotic regimen with placebo or no treatment or (ii) two or more alternative antibiotic regimens in pregnant women with bacterial vaginosis (however defined).

Types of participants

Women of any age, at any stage of pregnancy with a diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis regardless of method of diagnosis (detected because of symptoms or asymptomatic as part of a screening programme). Co‐infection with other sexually transmitted infections is not a reason to exclude a study from the review. Women classified as Nugent score four to six (intermediate flora) are included.

Types of interventions

Any antibiotic (any dosage regimen, any route of administration) compared with either placebo or no treatment. Any two antibiotic regimens compared.

Types of outcome measures

The outcome measures in this review are as follows.

Primary outcomes

Maternal symptoms

Failure to eradicate bacterial vaginosis on examination (failure to achieve 'microbiological cure').

Incidence of pregnancy loss up to 24 weeks' gestation (late miscarriage).

Neonatal outcomes

Clinical

Perinatal death including stillbirth after 24 weeks' gestation and neonatal death, up to 28 days after birth.

Neonatal sepsis (defined as definite symptoms or positive cultures from a sterile site ‐ positive culture of gastric aspirates alone will not be sufficient).

Birth less than 37 weeks' gestation.

Birth less than 34 weeks' gestation.

Birth less than 32 weeks' gestation.

Incidence of low birthweight (however defined).

Birthweight (not a prespecified outcome).

Prolongation of gestation age (not a prespecified outcome).

Maternal side‐effects

Side‐effects sufficient to stop or change treatment.

Other side‐effects not sufficient to stop or change treatment.

Secondary outcomes

Maternal symptoms

Clinical report by women of failure of symptoms to improve.

Incidence of preterm prelabour rupture of membranes.

Incidence of fever during labour or delivery.

Incidence of chorioamnionitis treated with antibiotics.

Incidence of postpartum fever.

Incidence of postpartum uterine infection.

Neonatal outcomes

Clinical

Severe neonatal morbidity (moderate to severe respiratory distress syndrome ‐ defined as any ventilatory support, intraventricular haemorrhage, necrotising enterocolitis, chronic lung disease).

Cerebral palsy at childhood follow‐up.

Moderate/severe visual impairment at childhood follow‐up.

Moderate/severe hearing impairment at childhood follow‐up.

Economic

Total duration of ventilatory support.

Admission to neonatal unit.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register by contacting the Trials Search Co‐ordinator (31 May 2012).

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register is maintained by the Trials Search Co‐ordinator and contains trials identified from:

monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE;

weekly searches of EMBASE;

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Details of the search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE and EMBASE, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service can be found in the ‘Specialized Register’ section within the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Trials identified through the searching activities described above are each assigned to a review topic (or topics). The Trials Search Co‐ordinator searches the register for each review using the topic list rather than keywords.

Searching other resources

We applied no language restrictions. We searched cited references from retrieved articles for additional studies and reviewed abstracts and letters to the editor to identify randomised controlled trials that have not been published. We also reviewed editorials, indicating expert opinion, to identify and ensure that no key studies were missed for inclusion in this review.

Data collection and analysis

For the methods used when assessing the trials identified in the previous version of this review, seeAppendix 1.

For this update, we used the following methods when assessing the reports identified by the updated search.

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently assessed for inclusion all the potential studies that were identified as a result of the search strategy. We resolved any disagreement through discussion.

Data extraction and management

A data extraction form was designed. For eligible studies, two review authors extracted the data using the agreed form. We resolved discrepancies through discussion. We entered the data into Review Manager software (RevMan 2011) and checked for accuracy.

When information regarding any of the above was unclear, we attempted to contact authors of the original reports to provide further details.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed the risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We resolved any disagreement by discussion or by involving a third assessor.

(1) Sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups.

We assessed the method as:

low risk of bias (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator);

high risk of bias (any non‐random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number);

unclear risk of bias.

(2) Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to conceal the allocation sequence and determined whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during recruitment, or changed after assignment.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

high risk of bias (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth);

unclear risk of bias.

(3.1) Blinding of participants and personnel (checking for possible performance bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We considered that studies are at low risk of bias if they were blinded, or if we judged that the lack of blinding could not have affected the results. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed the methods as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias participants;

low, high or unclear risk of bias for personnel.

(3.2) Blinding of outcome assessment (checking for possible detection bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind outcome assessors from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed methods used to blind outcome assessment as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias.

(4) Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias due to the amount, nature and handling of incomplete outcome data)

We described for each included study, and for each outcome or class of outcomes, the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We stated whether attrition and exclusions were reported, the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomised participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. Where sufficient information was reported, or could be supplied by the trial authors, we re‐included missing data in the analyses which we undertook. We assessed methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. no missing outcome data; missing outcome data balanced across groups);

high risk of bias (e.g. numbers or reasons for missing data imbalanced across groups; ‘as treated” analysis done with substantial departure of intervention received from that assigned at randomisation);

unclear risk of bias.

(5) Selective reporting (checking for reporting bias)

We described for each included study how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (where it is clear that all of the study’s pre‐specified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review have been reported);

high risk of bias (where not all the study’s pre‐specified outcomes have been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified; outcomes of interest are reported incompletely and so cannot be used; study fails to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported);

unclear risk of bias.

(6) Other sources of bias (checking for bias due to problems not covered by (1) to (5) above)

We described for each included study any important concerns we have about other possible sources of bias.

We assessed whether each study was free of other problems that could put it at risk of bias:

low risk of other bias;

high risk of other bias;

unclear whether there is risk of other bias.

(7) Overall risk of bias

Where applicable, we made explicit judgements about whether studies are at high risk of bias, according to the criteria given in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). With reference to (1) to (6) above, we assessed the likely magnitude and direction of the bias and whether we considered it was likely to impact on the findings. We explored the impact of the level of bias through undertaking Sensitivity analysis.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous data, we have presented results as summary risk ratio with 95% confidence intervals.

Continuous data

For continuous data, we used the mean difference if outcomes were measured in the same way between trials. We used the standardised mean difference to combine trials that measure the same outcome, but used different methods.

Dealing with missing data

For included studies, we noted levels of attrition. We explored the impact of including studies with high levels of missing data in the overall assessment of treatment effect by using sensitivity analysis.

For all outcomes, we carried out analyses, as far as possible, on an intention‐to‐treat basis, i.e. we attempted to include all participants randomised to each group in the analyses, and all participants were analysed in the group to which they were allocated, regardless of whether or not they received the allocated intervention. The denominator for each outcome in each trial was the number randomised minus any participants whose outcomes were known to be missing.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed statistical heterogeneity in each meta‐analysis using the T², I² and Chi² statistics. We regarded heterogeneity as substantial if the T² was greater than zero and either the I² was greater than 30% or there was a low P value (less than 0.10) in the Chi² test for heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

Where 10 or more studies reported a particular outcome in the meta‐analysis, we investigated reporting biases (such as publication bias) using funnel plots. We assessed funnel plot asymmetry visually.

Data synthesis

We carried out statistical analysis using the Review Manager software (RevMan 2011). We used fixed‐effect meta‐analysis for combining data where it was reasonable to assume that studies were estimating the same underlying treatment effect: i.e. where trials are examining the same intervention, and the trials’ populations and methods are judged sufficiently similar. If there was clinical heterogeneity sufficient to expect that the underlying treatment effects differed between trials, or if substantial statistical heterogeneity was detected, we used random‐effects meta‐analysis to produce an overall summary if an average treatment effect across trials was considered clinically meaningful. The random‐effects summary was treated as the average range of possible treatment effects and we discussed the clinical implications of treatment effects differing between trials. If the average treatment effect was not clinically meaningful we did not combine trials.

Where we used random‐effects analyses, the results were presented as the average treatment effect with its 95% confidence interval, and the estimates of T² and I².

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Where we identified substantial heterogeneity, we investigated it using subgroup analyses and sensitivity analyses.

We performed the following subgroup analyses.

Women with previous preterm birth.

Women with intermediate flora or bacterial vaginosis.

Treatment prior to 20 weeks' gestation.

In addition to the subgroups above, we also investigated the effect of different types of antibiotics, although this was not a subgroup pre‐specified in the protocol. We did not restrict subgroups of antibiotics to particular outcomes.

Subgroup analyses were restricted to the following outcomes for prespecified subgroups.

Failure of test of cure.

Perinatal death.

Preterm birth before 37, before 34 and before 32 weeks' gestation.

Incidence of low birthweight.

Neonatal sepsis.

Side‐effects.

Late miscarriage.

Admission to neonatal unit.

We assessed differences between subgroups by interaction tests available in RevMan 2011.

Sensitivity analysis

We undertook sensitivity analyses as part of investigation of heterogeneity in various analyses.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

This review is now comprised of 21 included studies, involving 13,209 women, of which 7847 were bacterial vaginosis or intermediate flora positive. Twenty studies are excluded and one study is ongoing (Subtil 2008), seeCharacteristics of ongoing studies.

Included studies

See table of Characteristics of included studies for further details of the 21 included studies.

Nine trials used oral metronidazole alone (Darwish 2007; McDonald 1997; Mitchell 2009; Moniri 2009; Morales 1994; NICHD MFMU 2000; NICHD MFMU 2001; Odendaal 2002; Shennan 2006), one used oral metronidazole plus erythromycin (Hauth 1995), one used oral clindamycin (Darwish 2007), one amoxicillin (Duff 1991), and one used vaginal metronidazole gel (Darwish 2007), whilst nine used intravaginal clindamycin (Vermeulen 1999; Darwish 2007; Giuffrida 2006; Guaschino 2003; Joesoef 1995; Kekki 2001; Kiss 2004; Lamont 2003; Larsson 2006). Sixteen trials performed microbiological follow‐up and 11 trials gave a second course of treatment (seven only if bacterial vaginosis was not eradicated). One trial (Porter 2001) compared different antibiotic regimens (once daily versus twice daily vaginal metronidazole).

Two trials (Lamont 2003; Ugwumadu 2003), which used intermediate vaginal flora (Nugent score four to six) as well as bacterial vaginosis as the basis for recruitment, have been included as a separate comparison (Analysis 7).

Excluded studies

For details of the 20 excluded studies, seeCharacteristics of excluded studies.

Risk of bias in included studies

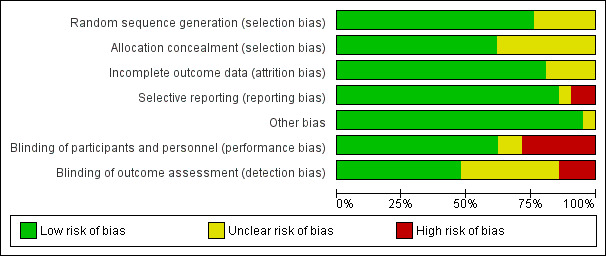

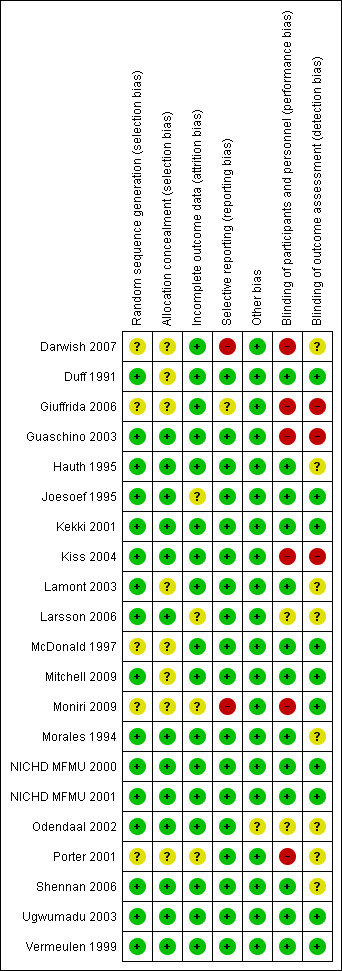

Overall, the majority of included studies performed well in a 'Risk of bias' analysis, as detailed below. See Figure 1; Figure 2 for summaries of risk of bias in included studies.

1.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

2.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Overall, the reporting of the method of random sequence generation was good, with all but five studies (Darwish 2007; Giuffrida 2006; McDonald 1997; Moniri 2009 ; Porter 2001) reporting adequate methods of random sequence generation. These studies did not report their method of random sequence generation, and therefore, the risk of selection bias was unclear.

Reporting of the method of allocation concealment was much less consistent. Thirteen studies reported an adequate method (Guaschino 2003; Hauth 1995; Joesoef 1995; Kekki 2001; Kiss 2004; Larsson 2006; Morales 1994; NICHD MFMU 2000; NICHD MFMU 2001; Odendaal 2002; Shennan 2006; Ugwumadu 2003; Vermeulen 1999). The remaining seven studies did not report their method of allocation concealment: (Darwish 2007; Duff 1991; Giuffrida 2006; Lamont 2003; McDonald 1997; Mitchell 2009; Porter 2001).

Blinding

When the intervention is a medication, as in the trials in this review, it is reasonable to expect trials to use a placebo control, which is identical in appearance to the active intervention, and for participants, clinicians and outcome assessors to be blinded to which treatment was given.

It should also be noted that although blinding was considered adequate for the majority of the included studies (for both participants and personnel and outcome assessment), for those studies that rescreened and therefore retreated some women there may be a potential risk of unblinding.

Blinding of participants and personnel

The majority of studies were adequately blinded (13/21).

Blinding methods were assessed as low risk in 13 studies: Duff 1991 (placebo group, triple‐blind); Hauth 1995 (placebo group, double‐blind); Joesoef 1995 (placebo group, double‐blind); Kekki 2001 (placebo group, triple‐blind); Lamont 2003 (placebo group, double‐blind); McDonald 1997 (placebo group, triple‐blind); Mitchell 2009 (placebo group, double‐blind); Morales 1994 (placebo group, double‐blind); NICHD MFMU 2000 (placebo group, double‐blind); NICHD MFMU 2001 (placebo group, double‐blind); Ugwumadu 2003 (placebo group, double‐blind); Vermeulen 1999 (placebo group, double‐blind);Shennan 2006 (placebo group, double blind).

Blinding methods were unclear (e.g. due to failure to report method) in the following studies: Larsson 2006 (complicated method of blinding; see 'Risk of bias' table for this trial); Odendaal 2002 (blinding not reported, placebo not identical).

Blinding methods were high risk in the following studies: Darwish 2007 (no placebo, different modes of administration so unable to blind participants/clinicians); Giuffrida 2006 (no placebo group, no reporting of blinding); Guaschino 2003 (no placebo group; no reporting of blinding); Kiss 2004 (no placebo group, no blinding); Porter 2001 (blinding not done, since comparison between two frequencies of administration and no placebo used) and Moniri 2009 (no placebo, no blinding).

Blinding of outcome assessment

Blinding of outcome assessment was reported and assessed as low risk in 10 studies (Duff 1991; Joesoef 1995; Kekki 2001; McDonald 1997; Mitchell 2009; NICHD MFMU 2000; NICHD MFMU 2001; Ugwumadu 2003; Vermeulen 1999;Moniri 2009), not reported and assessed as unclear in eight studies (Darwish 2007; Hauth 1995; Lamont 2003; Larsson 2006; Morales 1994; Odendaal 2002; Porter 2001; Shennan 2006) and high risk in three studies, where it was clear that blinding was not undertaken (Giuffrida 2006; Guaschino 2003; Kiss 2004).

Incomplete outcome data

Overall reporting of outcome data for all participants was done well, with 17/21 trials assessed as low risk: (Darwish 2007; Duff 1991; Giuffrida 2006; Guaschino 2003; Hauth 1995; Kekki 2001; Kiss 2004; Lamont 2003; McDonald 1997; Mitchell 2009; Morales 1994; NICHD MFMU 2000; NICHD MFMU 2001; Odendaal 2002; Shennan 2006; Ugwumadu 2003; Vermeulen 1999).

Three trials were assessed as being at unclear risk of attrition bias: Joesoef 1995 (please refer to 'Risk of bias' table for explanation); Larsson 2006 (please refer to 'Risk of bias' table for explanation); Porter 2001 (abstract only) and Moniri 2009 (please refer to 'Risk of bias' table for explanation) .

Selective reporting

Eighteen of the 21 trials were assessed as being at low risk of reporting bias: (Duff 1991; Guaschino 2003; Hauth 1995; Joesoef 1995; Kiss 2004; Kekki 2001; Lamont 2003; Larsson 2006; McDonald 1997; Mitchell 2009; Morales 1994; NICHD MFMU 2000; NICHD MFMU 2001; Odendaal 2002; Porter 2001; Shennan 2006; Ugwumadu 2003; Vermeulen 1999). The Giuffrida 2006 trial was judged to be at unclear risk due to not adequately labelling results tables (unclear as to whether mean values were being reported) and a small number of outcomes being reported. Darwish 2007 was judged to be at high risk of selective reporting bias due to inadequate statistical analysis and inadequate reporting of outcomes. Moniri 2009 was also assessed as high risk only reporting one of the three prespecified outcomes.

Other potential sources of bias

All studies apart from Odendaal 2002 were assessed as being at low risk of other sources of bias. In the case of Odendaal 2002, in which primigravidae and multigravidae groups were analysed separately, the baseline characteristics were significantly different between groups in the multigravidae women, with significant differences present in age, percentage antenatal antibiotic use and percentage asymptomatic bacteriuria. It is possible but not necessary that these differences could significantly influence the outcomes of the study.

Effects of interventions

Twenty‐one trials involving 7847 women with bacterial vaginosis or intermediate flora were included.

This updated review has restructured the comparisons analysed to assess outcomes for the following groups: 1) antibiotic versus placebo/no treatment; 2) antibiotic versus another antibiotic; 3) antibiotics: different routes of administration; 4) antibiotic versus another treatment; 5) antibiotics: different frequency/dose of administration.

The following subgroup analyses were also undertaken: 1) whether the women had experienced a previous preterm birth; 2) whether the women had intermediate vaginal flora (including bacterial vaginosis); and 3) treatment before 20 weeks' gestation.

Separate comparisons

1. Any antibiotic versus placebo/no treatment

Primary outcomes

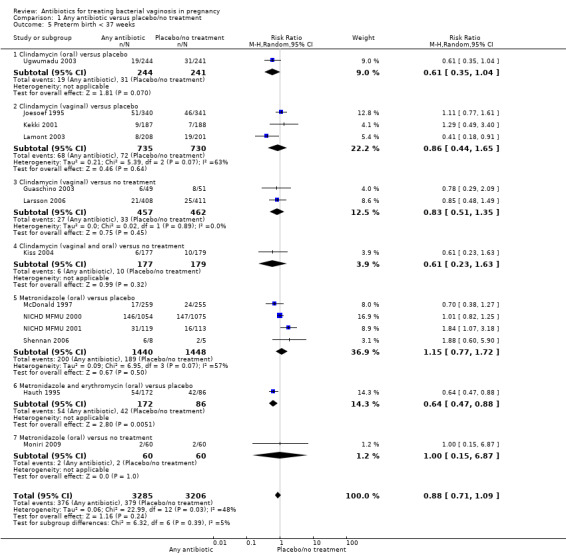

In terms of preterm births before 37 weeks, there is overall no significant advantage for antibiotics when compared to placebo/no treatment, from 13 trials with 6491 participants (average risk ratio (RR) 0.88; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.71 to 1.09, T² = 0.06, I² = 48% (Analysis 1.5)). However, there is substantial heterogeneity in this result (I² of 48%). The one trial comparing two oral antibiotics (metronidazole + erythromycin) against placebo (Hauth 1995) shows a significant benefit (RR 0.64; 95% CI 0.47 to 0.88; one trial 258 women). The test for subgroup differences to investigate heterogeneity present for preterm births before 37 weeks was not significant (P = 0.39, I² = 5.1%, (Analysis 1.5).

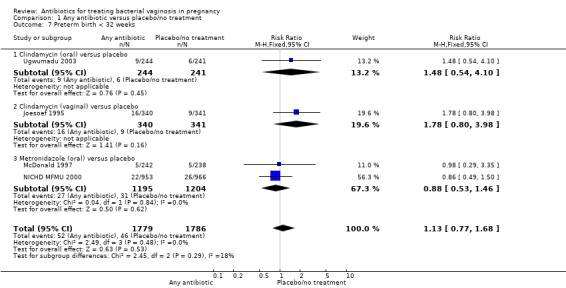

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any antibiotic versus placebo/no treatment, Outcome 5 Preterm birth < 37 weeks.

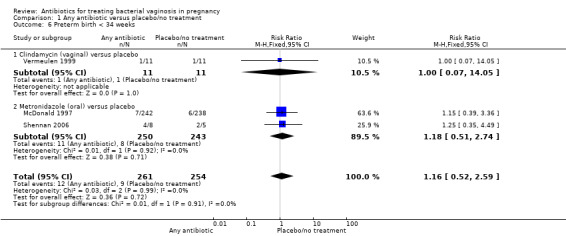

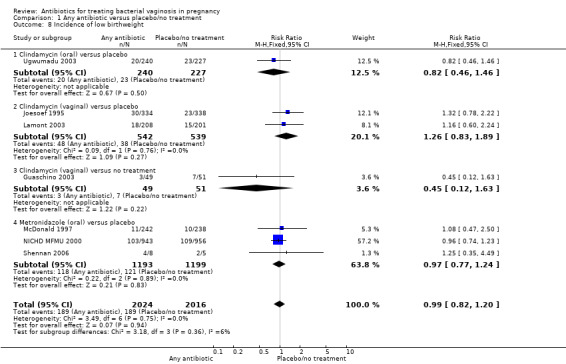

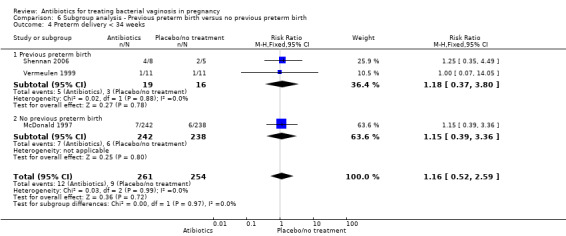

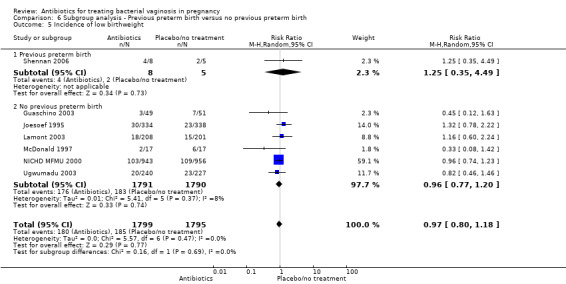

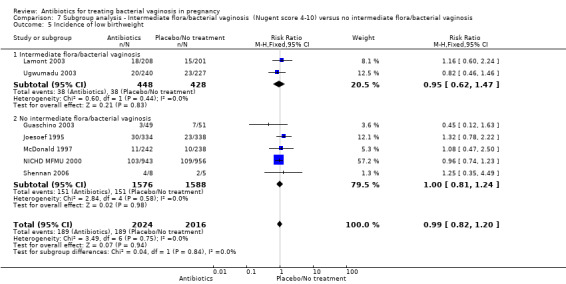

Similarly, there is no overall significant advantage for antibiotics when compared to placebo/no treatment for preterm births before 34 weeks (RR 1.16; 95% CI 0.52 to 2.59; three trials, 515 women (Analysis 1.6). There is also no indication of benefit from antibiotics when compared to placebo/no treatment for preterm births before 32 weeks (Analysis 1.7) or for low birthweight (RR 0.99; 95% CI 0.82 to 1.20; seven trials, 4040 women (Analysis 1.8)).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any antibiotic versus placebo/no treatment, Outcome 6 Preterm birth < 34 weeks.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any antibiotic versus placebo/no treatment, Outcome 7 Preterm birth < 32 weeks.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any antibiotic versus placebo/no treatment, Outcome 8 Incidence of low birthweight.

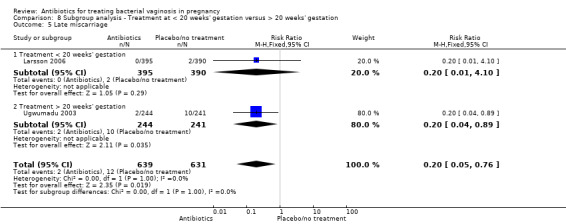

There was a significant benefit in reduction of late miscarriage for antibiotics compared with placebo/no treatment with very low heterogeneity for this result (RR 0.20; 95% CI 0.05 to 0.76; two trials,1270 women (Analysis 1.14)).

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any antibiotic versus placebo/no treatment, Outcome 14 Late miscarriage.

Overall, 10 trials with 4403 women indicated that antibiotics are generally beneficial, when compared to placebo/no treatment, with respect to failure of test of cure (average RR 0.42; 95% CI 0.31 to 0.56; T² = 0.19, I² = 91% (Analysis 1.1)). The very high level of heterogeneity in this analysis (I² = 91%) could be due to the differences in treatment effects between different antibiotics. The test for subgroup differences is significant (P < 0.00001, I² = 92.2%, (Analysis 1.1), and does appear to indicate this.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any antibiotic versus placebo/no treatment, Outcome 1 Failure of test of cure.

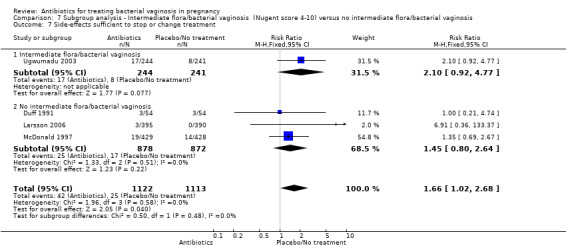

There were significantly higher rates of side‐effects sufficient to stop or change treatment in the antibiotics groups overall (RR 1.66; 95% CI 1.02 to 2.68; four trials, 2235 women (Analysis 1.10)).

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any antibiotic versus placebo/no treatment, Outcome 10 Side‐effects sufficient to stop or change treatment.

Secondary outcomes

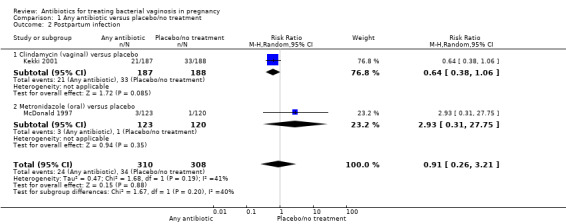

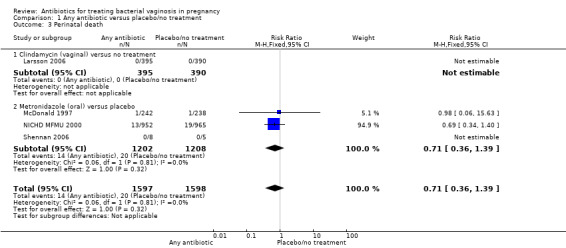

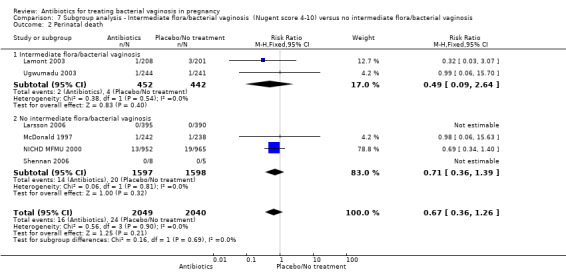

There was no statistically significant advantage for antibiotics when compared to placebo/no treatment, with respect to postpartum infection (average RR 0.91; 95% CI 0.26 to 3.21; two trials, 618 participants; T² = 0.47, I² = 41% (Analysis 1.2)) or in terms of perinatal death from four trials with 3195 participants (RR 0.71; 95%; CI 0.36 to 1.39 (Analysis 1.3)).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any antibiotic versus placebo/no treatment, Outcome 2 Postpartum infection.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any antibiotic versus placebo/no treatment, Outcome 3 Perinatal death.

Similarly, there was no statistically significant advantage for antibiotics when compared to placebo/no treatment, with respect to the incidence of preterm prelabour rupture of membranes from two trials (McDonald 1997; Shennan 2006) with 493 participants (RR 0.74; 95% CI 0.30 to 1.84 (Analysis 1.4)). Please see Table 1 for information regarding reporting of preterm prelabour rupture of membranes in the included studies.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any antibiotic versus placebo/no treatment, Outcome 4 Incidence of preterm prelabour rupture of membranes.

1. Reporting of rupture of membranes in included trials.

| Trial | Was PPROM reported? | What outcome was reported regarding ROM? |

| Darwish 2007 | no | PROM |

| Duff 1991 | no | PROM |

| Giuffrida 2006 | no | PROM |

| Guaschino 2003 | no | PROM |

| Hauth 1995 | no | DNR |

| Joesoef 1995 | no | DNR |

| Kekki 2001 | no | DNR |

| Kiss 2004 | no | DNR |

| Lamont 2003 | no | DNR |

| Larsson 2006 | no | DNR |

| McDonald 1997 | yes | PPROM |

| Mitchell 2009 | no | DNR |

| Morales 1994 | no | PROM |

| NICHD MFMU 2000 | no | preterm SROM |

| NICHD MFMU 2001 | no | preterm membrane rupture |

| Odendaal 2002 | no | DNR |

| Porter 2001 | no | SROM |

| Shennan 2006 | yes | PPROM |

| Ugwumadu 2003 | no | DNR |

| Vermeulen 1999 | no | DNR |

DNR = did not report PROM = prelabour rupture of membranes PPROM = preterm prelabour rupture of membranes SROM = spontaneous rupture of membranes

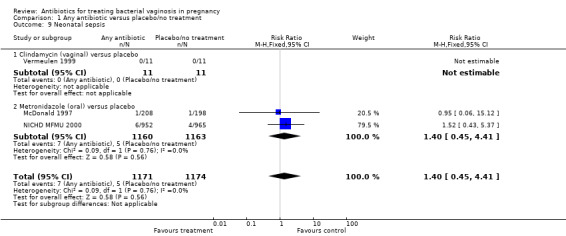

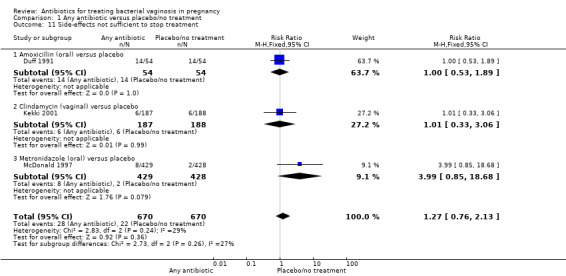

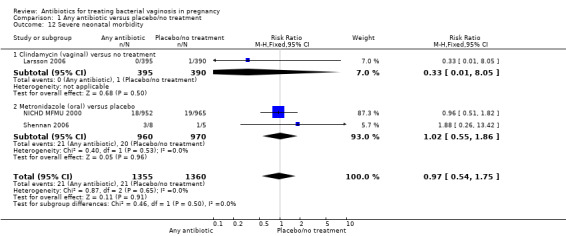

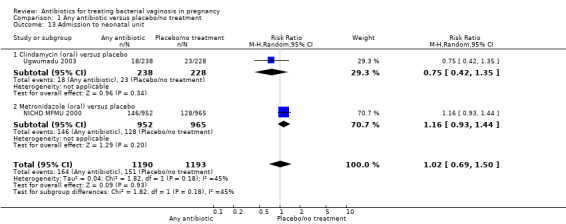

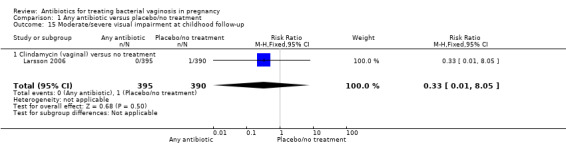

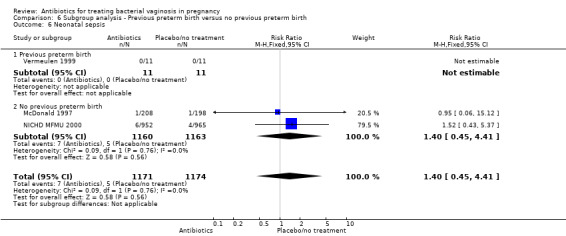

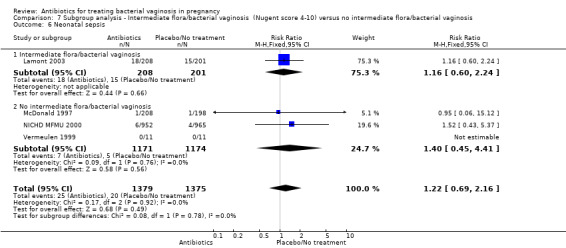

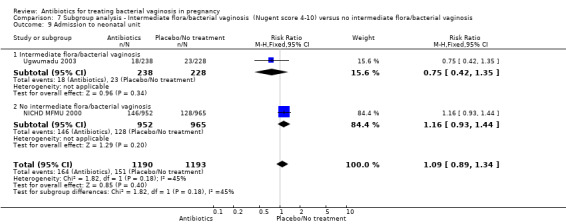

There was no significant difference between antibiotics and placebo/no treatment in terms of: neonatal sepsis (RR 1.40; 95% CI 0.45 to 4.41; three trials, 2345 women (Analysis 1.9)); side‐effects not sufficient to stop or change treatment (RR 1.27; 95% CI 0.76 to 2.13; three trials,1340 women (Analysis 1.11)); severe neonatal morbidity (RR 0.97; 95% CI 0.54 to 1.75; three trials, 2715 women (Analysis 1.12)); admission to neonatal unit (average RR 1.02; 95% CI 0.69 to 1.50; two trials, 2383 women; T² = 0.04, I² = 45% (Analysis 1.13)); and moderate/severe visual impairment at childhood follow‐up (RR 0.33; 95% CI 0.01 to 8.05; one trial, 785 women (Analysis 1.15)).

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any antibiotic versus placebo/no treatment, Outcome 9 Neonatal sepsis.

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any antibiotic versus placebo/no treatment, Outcome 11 Side‐effects not sufficient to stop treatment.

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any antibiotic versus placebo/no treatment, Outcome 12 Severe neonatal morbidity.

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any antibiotic versus placebo/no treatment, Outcome 13 Admission to neonatal unit.

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any antibiotic versus placebo/no treatment, Outcome 15 Moderate/severe visual impairment at childhood follow‐up.

2. Antibiotic versus another antibiotic

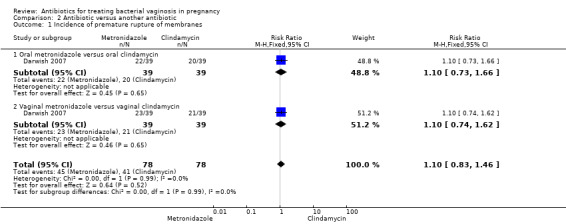

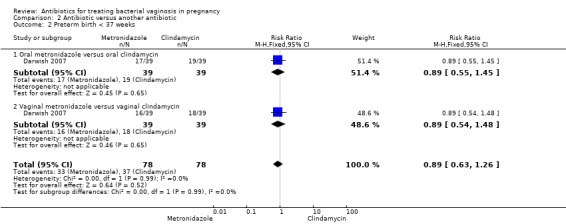

There was no significant difference between metronidazole and clindamycin in relation to the incidence of premature rupture of membranes (RR 1.10; 95% CI 0.83 to 1.46 (Analysis 2.1)), preterm birth before 37 weeks (RR 0.89; 95% CI 0.63 to 1.26 (Analysis 2.2)), or admission to neonatal unit (RR 0.97; 95% CI 0.67 to 1.40 (Analysis 2.3)). Prolongation of gestational age (days) (mean difference (MD) 1.00; 95% CI 0.26 to 1.74 (Analysis 2.4)) and birthweight (grams) (MD 75.18; 95% CI 25.37 to 124.99 (Analysis 2.5)) were significantly higher with metronidazole when compared with clindamycin. However, these data are from a single trial (Darwish 2007) with 156 participants and although statistically significant represent less significance clinically.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Antibiotic versus another antibiotic, Outcome 1 Incidence of premature rupture of membranes.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Antibiotic versus another antibiotic, Outcome 2 Preterm birth < 37 weeks.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Antibiotic versus another antibiotic, Outcome 3 Admission to neonatal unit.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Antibiotic versus another antibiotic, Outcome 4 Prolongation of gestational age (days).

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Antibiotic versus another antibiotic, Outcome 5 Birthweight (grams).

3. Antibiotics: different routes of administration

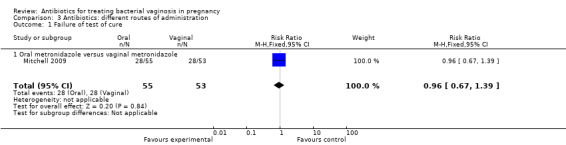

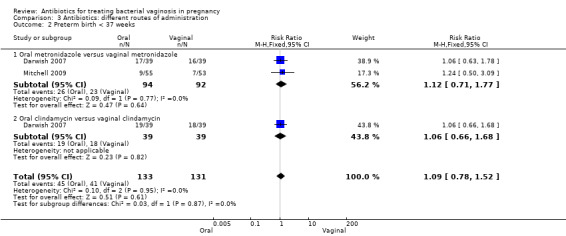

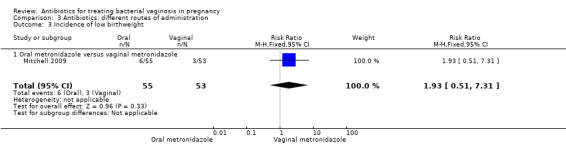

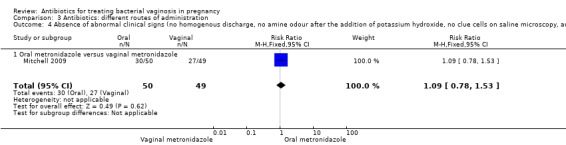

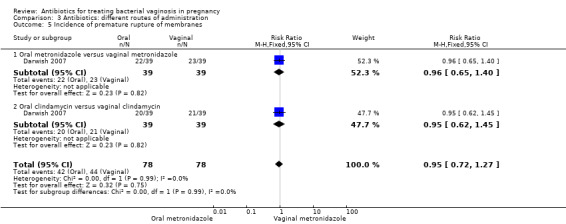

There was no significant difference between oral and vaginal antibiotics in relation to the eradication of bacterial vaginosis on examination (RR 0.96; 95% CI 0.67 to 1.39; one trial, 108 women (Analysis 3.1)), preterm birth before 37 weeks (RR 1.09; 95% CI 0.78 to 1.52; two trials, 264 women (Analysis 3.2)), incidence of low birthweight (RR 1.93; 95% CI 0.51 to 7.31; one trial, 108 women (Analysis 3.3), absence of abnormal clinical signs (RR 1.09; 95% CI 0.78 to 1.53; one trial, 99 women (Analysis 3.4)), or incidence of premature rupture of membranes (RR 0.95; 95% CI 0.72 to 1.27; one trial, 156 women (Analysis 3.5)).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Antibiotics: different routes of administration, Outcome 1 Failure of test of cure.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Antibiotics: different routes of administration, Outcome 2 Preterm birth < 37 weeks.

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Antibiotics: different routes of administration, Outcome 3 Incidence of low birthweight.

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Antibiotics: different routes of administration, Outcome 4 Absence of abnormal clinical signs (no homogenous discharge, no amine odour after the addition of potassium hydroxide, no clue cells on saline microscopy, and PH<4.5).

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Antibiotics: different routes of administration, Outcome 5 Incidence of premature rupture of membranes.

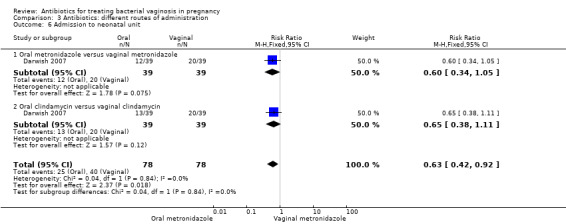

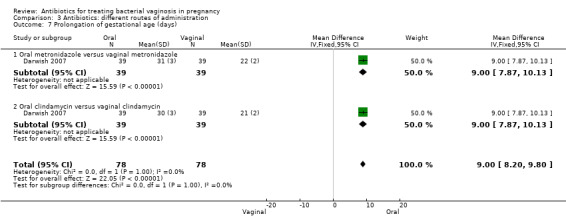

However, there was an advantage for oral antibiotics over vaginal antibiotics (whether metronidazole or clindamycin) with respect to admission to neonatal unit (RR 0.63; 95% CI 0.42 to 0.92; two trials with 156 women (Analysis 3.6), prolongation of gestational age (MD 9.00; 95% CI 8.20 to 9.80; one trial, 156 women (Analysis 3.7)) and birthweight (grams) (MD 342.13; 95% CI 293.04 to 391.22; one trial, 156 women (Analysis 3.8)).

3.6. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Antibiotics: different routes of administration, Outcome 6 Admission to neonatal unit.

3.7. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Antibiotics: different routes of administration, Outcome 7 Prolongation of gestational age (days).

3.8. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Antibiotics: different routes of administration, Outcome 8 Birthweight (grams).

4. Antibiotic versus another treatment

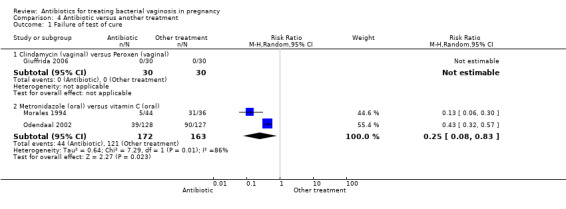

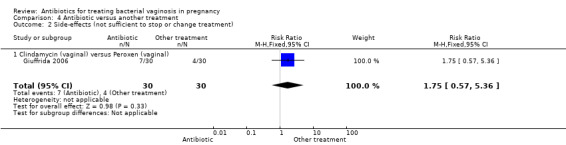

Only three trials compared antibiotic treatments with non‐antibiotic treatments; one of these trials (Giuffrida 2006) compared vaginal clindamycin with vaginal peroxen (hydrogen peroxide 0.5%), and the other two trials (Morales 1994; Odendaal 2002) compared oral metronidazole with oral vitamin C. Vitamin C was classified as a placebo by both of these trials, although vitamin C has potential anti‐infective properties (Hemilä 2007) so this group was separately analysed in this review.

Treatment with oral metronidazole was significantly more likely to result in eradication of bacterial vaginosis on microbiological examination (decreased failure of test of cure) compared with oral vitamin C (average RR 0.25; 95% CI 0.08 to 0.83; two trials, 335 women; T² = 0.64, I² = 86%). The Giuffrida 2006 trial also reported failure of test of cure, but no events of failure of test of cure were reported for this study, so no RR was calculable (Analysis 4.1). Giuffrida 2006 reported no significant difference in side‐effects (not sufficient to stop or change treatment), RR 1.75; 95% CI 0.57 to 5.36, 60 women, (Analysis 4.2).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Antibiotic versus another treatment, Outcome 1 Failure of test of cure.

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Antibiotic versus another treatment, Outcome 2 Side‐effects (not sufficient to stop or change treatment).

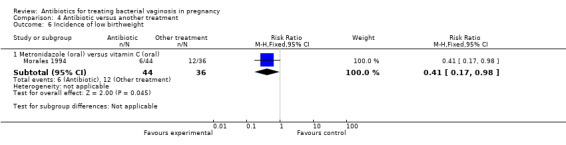

Morales 1994 only reported the incidence of low birthweight, with lower numbers of low birthweight infants in the group treated with oral metronidazole versus the group treated with vitamin C, although this was only just significant (RR 0.41; 95% CI 0.17 to 0.98, one trial, 80 women (Analysis 4.6)).

4.6. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Antibiotic versus another treatment, Outcome 6 Incidence of low birthweight.

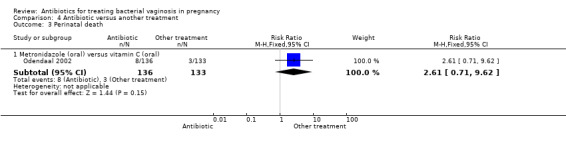

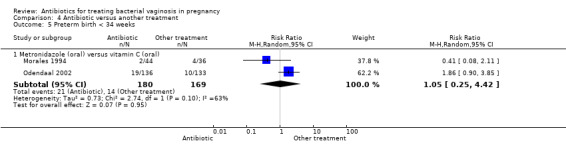

Odendaal 2002 only reported rates of perinatal death, although the result did not show any significant difference (RR 2.61; 95% CI 0.71 to 9.62; one trial, 269 women (Analysis 4.3)). Similarly, the results for preterm birth before 37 weeks or 34 weeks overall were not significantly different (Analysis 4.4; Analysis 4.5).

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Antibiotic versus another treatment, Outcome 3 Perinatal death.

4.4. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Antibiotic versus another treatment, Outcome 4 Preterm birth < 37 weeks.

4.5. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Antibiotic versus another treatment, Outcome 5 Preterm birth < 34 weeks.

Significant heterogeneity was seen for the analyses that included the Morales 1994 and Odendaal 2002 data. This likely relates to the differing study settings, timing of treatment and exclusion criteria for the trials.

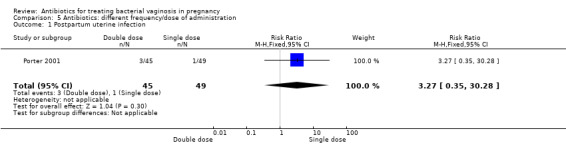

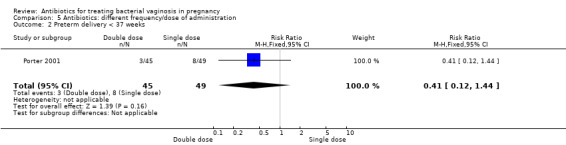

5. Antibiotics: different frequency/dose of administration

Results from a single trial (Porter 2001, n = 94) comparing outcomes of use of vaginal metronidazole gel in once daily versus twice daily dosing regimens, indicated that there was no significant benefit for a double dose over a single dose with respect to postpartum uterine infection (RR 3.27; 95% CI 0.35 to 30.28; one trial, 94 women (Analysis 5.1)), preterm delivery before 37 weeks (RR 0.41; 95% CI 0.12 to 1.44; one trial, 94 women (Analysis 5.2)) or incidence of low birthweight (RR 1.19; 95% CI 0.58 to 2.42; one trial, 94 women (Analysis 5.3)).

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Antibiotics: different frequency/dose of administration, Outcome 1 Postpartum uterine infection.

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Antibiotics: different frequency/dose of administration, Outcome 2 Preterm delivery < 37 weeks.

5.3. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Antibiotics: different frequency/dose of administration, Outcome 3 Incidence of low birthweight.

Subgroup analyses

Sugroup analyses have been performed only on studies from the main comparison of any antibiotic versus placebo/no treatment. There were insufficient studies included in the remaining comparisons (Analysis 2; Analysis 3; Analysis 4; Analysis 5) to shed any light on differences between subgroups.

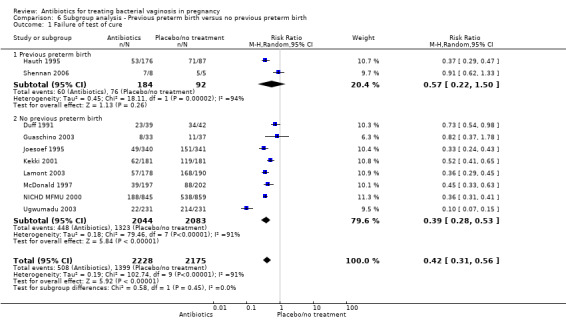

6. Previous preterm birth versus no previous preterm birth

The use of antibiotics was beneficial in terms of failure of test of cure in comparison with placebo/no treatment for the subgroup of women with no previous preterm birth (no previous preterm birth: average RR 0.39; 95% CI 0.28 to 0.53; eight trials, 4127 women; random‐effects, T² = 0.18, I² = 91%), however no difference was observed for women with a history of previous preterm birth: average RR 0.57; 95% CI 0.22 to 1.50; two trials; 276 women; random‐effects, T² = 0.45, I² = 94% (Analysis 6.1)). Substantial heterogeneity was apparent in both subgroups (I² = 94%; I² = 91%) and in the overall analysis (I² = 91%). There was no evidence of any subgroup differences (P = 0.45; I² = 0%, Analysis 6.1).

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Subgroup analysis ‐ Previous preterm birth versus no previous preterm birth, Outcome 1 Failure of test of cure.

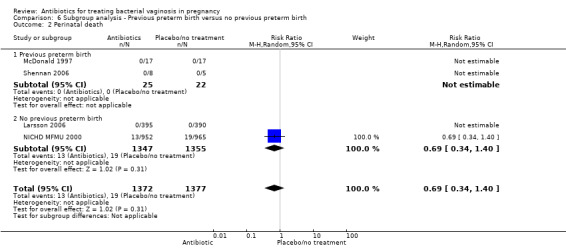

For all other subgroup analyses, there were no evidence of an effect for any of the outcomes examined (perinatal death; preterm delivery less than 37 weeks; preterm delivery less than 34 weeks; low birthweight; neonatal sepsis) and no evidence of a difference between subgroups (Analysis 6.2; Analysis 6.3; Analysis 6.4; Analysis 6.5; Analysis 6.6).

6.2. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Subgroup analysis ‐ Previous preterm birth versus no previous preterm birth, Outcome 2 Perinatal death.

6.3. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Subgroup analysis ‐ Previous preterm birth versus no previous preterm birth, Outcome 3 Preterm delivery < 37 weeks.

6.4. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Subgroup analysis ‐ Previous preterm birth versus no previous preterm birth, Outcome 4 Preterm delivery < 34 weeks.

6.5. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Subgroup analysis ‐ Previous preterm birth versus no previous preterm birth, Outcome 5 Incidence of low birthweight.

6.6. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Subgroup analysis ‐ Previous preterm birth versus no previous preterm birth, Outcome 6 Neonatal sepsis.

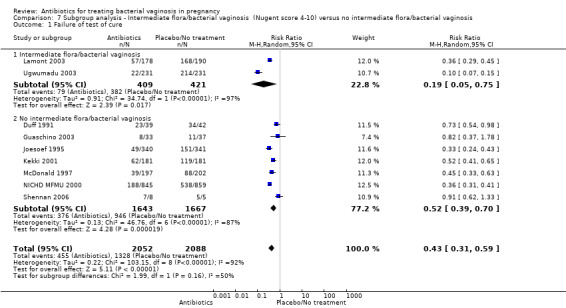

7. Women with intermediate flora or bacterial vaginosis (Nugent score four to 10) versus women with no intermediate flora or bacterial vaginosis

Only two trials reported outcomes for the subgroup of patients diagnosed with either intermediate flora or bacterial vaginosis (Nugent score four to 10).These trials were Ugwumadu 2003, with 485 participants, and Lamont 2003, with 409 participants.

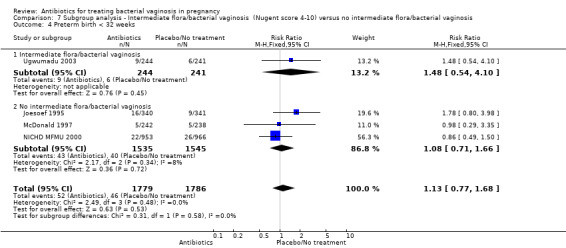

In the subgroup of women with intermediate flora or bacterial vaginosis, the use of antibiotics was associated with a significant reduction in preterm birth less than 37 weeks (average RR 0.53; 95% CI 0.34 to 0.84; two trials 894 women; random‐effects T² = 0.00, I² = 0% (Analysis 7.3). There was no significant difference in preterm birth less than 37 weeks in the subgroup of studies with no intermediate flora or bacterial vaginosis (average RR 0.93; 95% CI 0.75 to 1.16; 10 trials 5584 women; random‐effects T² = 0.04, I² = 42% (Analysis 7.3). There was evidence for a difference in subgroups (P = 0.03; I² = 79.2%, Analysis 7.3); however, this should be interpreted with caution because there were only two studies in the intermediate flora or bacterial vaginosis subgroup.

7.3. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Subgroup analysis ‐ Intermediate flora/bacterial vaginosis (Nugent score 4‐10) versus no intermediate flora/bacterial vaginosis, Outcome 3 Preterm birth < 37 weeks.

There were no significant differences between antibiotic and placebo/no treatment groups for any of the outcomes examined for any of the subgroups (failure of test of cure; perinatal death; preterm birth less than 32 weeks; incidence of low birthweight; side‐effects not sufficient to stop treatment; late miscarriage; admission to neonatal unit) and no evidence of a difference between subgroups for any of these outcomes (Analysis 7.1; Analysis 7.2; Analysis 7.4; Analysis 7.5; Analysis 7.6; Analysis 7.7; Analysis 7.8; Analysis 7.9).

7.1. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Subgroup analysis ‐ Intermediate flora/bacterial vaginosis (Nugent score 4‐10) versus no intermediate flora/bacterial vaginosis, Outcome 1 Failure of test of cure.

7.2. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Subgroup analysis ‐ Intermediate flora/bacterial vaginosis (Nugent score 4‐10) versus no intermediate flora/bacterial vaginosis, Outcome 2 Perinatal death.

7.4. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Subgroup analysis ‐ Intermediate flora/bacterial vaginosis (Nugent score 4‐10) versus no intermediate flora/bacterial vaginosis, Outcome 4 Preterm birth < 32 weeks.

7.5. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Subgroup analysis ‐ Intermediate flora/bacterial vaginosis (Nugent score 4‐10) versus no intermediate flora/bacterial vaginosis, Outcome 5 Incidence of low birthweight.

7.6. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Subgroup analysis ‐ Intermediate flora/bacterial vaginosis (Nugent score 4‐10) versus no intermediate flora/bacterial vaginosis, Outcome 6 Neonatal sepsis.

7.7. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Subgroup analysis ‐ Intermediate flora/bacterial vaginosis (Nugent score 4‐10) versus no intermediate flora/bacterial vaginosis, Outcome 7 Side‐effects sufficient to stop or change treatment.

7.8. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Subgroup analysis ‐ Intermediate flora/bacterial vaginosis (Nugent score 4‐10) versus no intermediate flora/bacterial vaginosis, Outcome 8 Late miscarriage.

7.9. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Subgroup analysis ‐ Intermediate flora/bacterial vaginosis (Nugent score 4‐10) versus no intermediate flora/bacterial vaginosis, Outcome 9 Admission to neonatal unit.

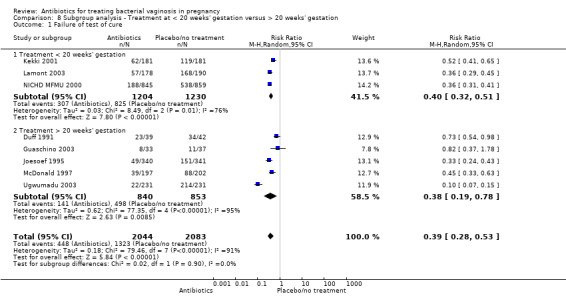

8. Treatment before 20 weeks' gestation versus treatment after 20 weeks' gestation

In both subgroups of women, the use of antibiotics were beneficial in terms of failure of test of cure in comparison with placebo/no treatment (treatment before 20 weeks': average RR 0.40; 95% CI 0.32 to 0.51; three trials, 2434 women; random‐effects, T² = 0.03, I² = 76%; and treatment after 20 weeks': average RR 0.38; 95% CI 0.19 to 0.78; five trials; 1693 women; random‐effects, T² = 0.62, I² = 95% (Analysis 8.1). However, substantial heterogeneity was apparent in both subgroups (I² = 76%; I² = 95%) and in the overall analysis (I² = 91%). There was no evidence of any subgroup differences (P = 0.90; I² = 0%, Analysis 8.1).

8.1. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Subgroup analysis ‐ Treatment at < 20 weeks' gestation versus > 20 weeks' gestation, Outcome 1 Failure of test of cure.

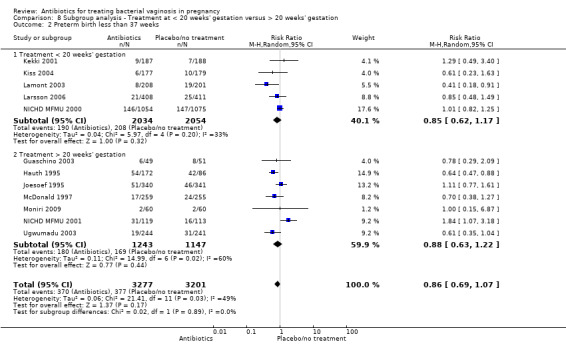

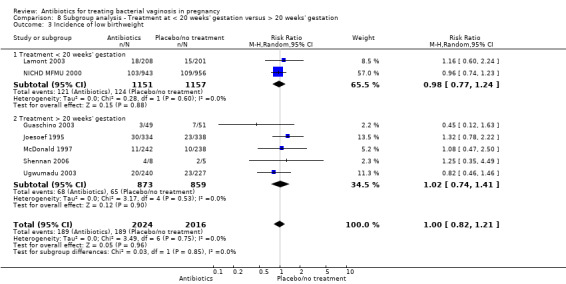

For all other subgroup analyses, there were no evidence of an effect for any of the outcomes examined (preterm delivery less than 37 weeks; low birthweight; side‐effects not sufficient to stop treatment; late miscarriage) and no evidence of a difference between subgroups (Analysis 8.2; Analysis 8.3; Analysis 8.4; Analysis 8.5).

8.2. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Subgroup analysis ‐ Treatment at < 20 weeks' gestation versus > 20 weeks' gestation, Outcome 2 Preterm birth less than 37 weeks.

8.3. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Subgroup analysis ‐ Treatment at < 20 weeks' gestation versus > 20 weeks' gestation, Outcome 3 Incidence of low birthweight.

8.4. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Subgroup analysis ‐ Treatment at < 20 weeks' gestation versus > 20 weeks' gestation, Outcome 4 Side‐effects not sufficient to stop treatment.

8.5. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Subgroup analysis ‐ Treatment at < 20 weeks' gestation versus > 20 weeks' gestation, Outcome 5 Late miscarriage.

Assessment of reporting biases

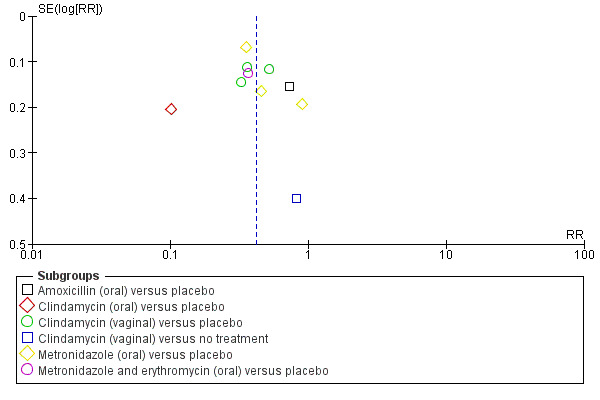

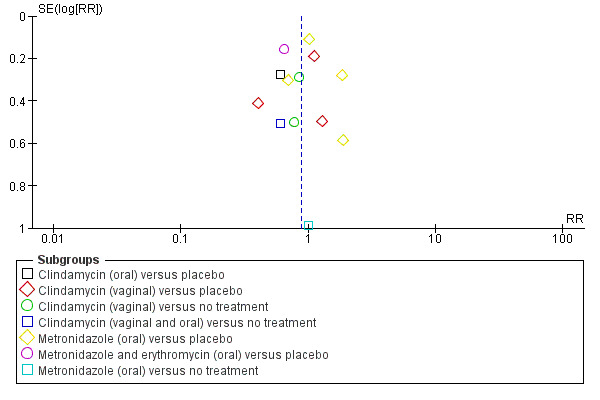

Only two outcomes were reported in 10 or more studies, so publication bias was assessed for these outcomes using funnel plots. Funnel plots were constructed for Analysis 1.1, (failure of test of cure; antibiotic versus placebo/no treatment) Figure 3 and for Analysis 1.5 (preterm birth before 37 weeks; antibiotic versus placebo/no treatment) Figure 4.

3.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Any antibiotic versus placebo/no treatment, outcome: 1.1 Failure of test of cure.

4.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Any antibiotic versus placebo/no treatment, outcome: 1.5 Preterm birth < 37 weeks.

On visual inspection of the funnel plot for failure of test of cure, (seeFigure 3) there appears to be a risk of reporting bias for this outcome, as indicated by an asymmetrical plot.

The funnel plot for preterm birth before 37 weeks, (seeFigure 4) should be interpreted with caution, given that the studies that reported the outcome of preterm birth were of similar sample size (similar standard errors of intervention effect estimates) (see Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions section 10.4.3.1). On visual inspection of the funnel plot, there appears to be a low risk of reporting bias for this outcome.

Discussion

Summary of main results

Twenty‐one trials involving 13,209 women were included (of which 7847 women were bacterial vaginosis or intermediate flora positive). Many of the prespecified outcomes for this review were not assessed by the included trials. The available evidence from these trials suggests that antibiotic treatment given to women with bacterial vaginosis in pregnancy is highly effective at eradicating bacterial vaginosis infection (risk ratio (RR) 0.42; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.31 to 0.56; 10 trials of 4403 women). There was significant heterogeneity between trials for many of the comparisons; therefore, random‐effects analyses were used where necessary.

There was no statistically significant decrease in the risk of preterm birth (PTB) at less than 37 weeks' gestation for any antibiotic treatment versus no treatment or placebo (average RR 0.88; 95% CI 0.71 to 1.09; 13 trials, 6491 women). There was also no evidence of an effect on birth before 34 weeks (RR 1.16; 95% CI 0.52 to 2.59; three trials of 515 women), nor for an effect on birth before 32 weeks (RR 1.13; 95% CI 0.77 to 1.68; four trials of 3565 women). The effect of treatment on the incidence of low birthweight suggests no difference (RR 0.99; 95% CI 0.82 to 1.2; seven trials of 4040 women). Antibiotics were not associated with a decrease in the risk of preterm prelabour rupture of membranes (RR 0.74; 95% CI 0.30 to 1.84; two trials of 493 women).

In this updated review, treatment before 20 weeks' gestation did not reduce the risk of PTB less than 37 weeks and in women with a previous PTB, again, there was no reduction in the risk of subsequent PTB. However, in women with abnormal vaginal flora (intermediate flora or bacterial vaginosis), the evidence from two trials suggests that treatment may reduce the risk of PTB before 37 weeks.

Very few perinatal deaths were reported and only one trial (NICHD MFMU 2000 unpublished) reported substantive measures of neonatal morbidity or economic outcomes such as health service utilisation. There was, however, a substantial reduction in late miscarriage with the use of antibiotics (RR 0.20; 95% CI 0.05 to 0.76; two trials with 1270 women), but also an increase in side‐effects sufficient to stop treatment (RR 1.66; 95% CI 1.02 to 2.68; four trials, 2235 women).

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

There is now a substantial body of evidence that associates bacterial vaginosis in pregnancy with a poor perinatal outcome, in particular an increased risk of preterm birth (Donders 2009; Hay 1994a; Hillier 1995; Kurki 1992; Lamont 2011a; Leitich 2007; McGregor 1990). This strong association between bacterial vaginosis and preterm birth has led many researchers and clinicians to believe that bacterial vaginosis may be the cause of preterm birth in these women.

The results of trials that treat bacterial vaginosis in pregnancy, however, are not encouraging. This updated review now includes six additional trials, one from this update (Moniri 2009) and five from the previous update (Darwish 2007; Giuffrida 2006; Larsson 2006; Mitchell 2009; Shennan 2006) and continues to show no significant reduction in preterm birth from 13 trials involving 6491 women. The review has been restructured to make it clearer to see the differences between trials in terms of antibiotic used, frequency and route and whether compared with placebo or another treatment. Subgroup analyses have also been re‐done for the subgroups of women with previous preterm birth, intermediate flora or bacterial vaginosis or treatment prior to 20 weeks' gestation. The evidence does not now suggest any differential effect between subgroups of women with a previous/no previous preterm birth or treatment before 20 weeks's gestation/after 20 weeks' gestation for the outcomes examined. There is some suggestion that in women identified as having abnormal vaginal flora (intermediate flora or bacterial vaginosis), treatment may reduce the risk of PTB before 37 weeks; however, this result comes from only two studies of 894 women.

Interestingly, there is a benefit from antibiotics in terms of an 80% reduction in late miscarriage. This result is from only two trials but does involve 1270 women. Both studies used clindamycin. This finding may be consistent with the increasing evidence that for treatment to be effective it needs to be started early.

In this update however, for the subgroup of women treated before 20 weeks' gestation, there was no evidence of an effect for any of the outcomes examined (preterm delivery less than 37 weeks; low birthweight; side‐effects not sufficient to stop treatment; late miscarriage). As there have been no head‐to‐head comparisons of early versus late treatment, trials in this area are warranted. The only trial large enough to stratify their results by early or later treatment failed to show any difference in effect when comparing earlier versus later treatment, although it could be argued that even in the early group, treatment was not started early enough. A recent meta‐analysis of clindamycin treatment of bacterial vaginosis prior to 22 weeks' gestation included five of the studies assessed in this review and demonstrated a significantly reduced risk of preterm birth and late miscarriage (Lamont 2011b). Their results remained significant when sensitivity analysis was performed including two further studies.

The two trials of women with abnormal vaginal flora, i.e. intermediate flora or bacterial vaginosis (Lamont 2003; Ugwumadu 2003), showed significantly decreased rates of preterm birth less than 37 weeks' gestation with treatment, which the authors postulate may be due to the earlier gestation of treatment in both these studies (13 to 20 weeks for Lamont 2003 and 12 to 22 weeks (mean 15.6) (for Ugwumadu 2003). When analysed as a separate category, antibiotic treatment of abnormal flora resulted in a significant decrease in preterm birth. However, their inclusion in meta‐analysis of all the trials has not made a substantial difference to the overall picture.

Additional information on neonatal sepsis from the large NICHD MFMU trial is included in the analysis but provides no evidence of a reduction in neonatal sepsis.

Significant heterogeneity was found in several analyses; in the 'failure of test of cure' analysis this is probably due to differences in the timing of the test of cure and the method for determining test of cure. Also, trials in this review have used several different methods of diagnosing bacterial vaginosis or abnormal genital flora (Amsel or clinical criteria, Gram stain criteria, and abnormal Nugent score four to 10).

Limitations of the trials

The trial protocols differ in a number of ways such as the method for diagnosing bacterial vaginosis, timing of screening, timing of treatment, and the period between screening and treatment. Most trials have tested treatment in the second trimester; some as late as 28 weeks' gestation. This may be too late to prevent the consequences of any ascending infection and may be one of the main reasons for the observed lack of a statistically significant effect on the preterm birth rates. The efficacy of antibiotic treatment in long‐term eradication of bacterial vaginosis is at best 80%. The subgroups of women in whom bacterial vaginosis was successfully eradicated, and those with recurring bacterial vaginosis, need to be identified and studied more closely in future trials.

Most trials have concentrated on the timing of birth and have made the assumption that the later in gestation a baby is born, the greater are its chances of disability‐free survival. This may not be the case, however. Neonatal well being and measures of maternal postpartum morbidity were each reported by two trials. However, the majority of outcomes we considered important for this review were not mentioned.

Since the first publication of the earlier Cochrane review in 1998 (Brocklehurst 1998), the number of women in this meta‐analysis has more than trebled, largely due to the inclusion of the NICHD MFMU 2000 and NICHD MFMU 2001 studies with 2132 women. This fourth review has increased the trial numbers by 1294. There remains no clear evidence that screening and treating all women with bacterial vaginosis in the antenatal period will have a major impact on the consequences of preterm birth, however the area of screening and treating abnormal flora deserves further investigation.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The evidence to date does not suggest any benefit in screening and treating all pregnant women for asymptomatic bacterial vaginosis to prevent preterm birth. The lack of a significant effect despite large numbers of women in the included trials may be due to many differences within the trials regarding diagnosis, timing of treatment and antibiotic choice. In considering the implications for clinical practice it should be remembered, however, that many of the trials excluded women with symptomatic bacterial vaginosis due to treatment of their symptoms with antibiotics. These women, especially those with recurrent or persistent bacterial vaginosis, may be at highest risk of associated adverse outcomes. Unfortunately, from studies to date we know almost nothing about the impact of these interventions on the health of the baby.

At the present time, there seems little justification for initiating a policy of screening for asymptomatic bacterial vaginosis in pregnancy. Any impact may be dependent upon early detection and treatment.

Implications for research.

The consequences of preterm birth to the individuals concerned and the health services are of major importance. Any intervention with the potential to decrease the risk of mortality and morbidity associated with neonatal immaturity, therefore, needs prompt and appropriate evaluation so that any benefits may be maximised. The focus of current research is to identify those subgroups of pregnant women who are at highest risk for adverse sequelae of bacterial vaginosis. These subgroups include women with recurrent or persistent bacterial vaginosis. Individual susceptibility to preterm birth may also be increased by the presence of specific gene polymorphisms, producing a heightened inflammatory response to vaginal or intrauterine infection. In addition, recent findings suggest future studies may need to focus on earlier detection and treatment of bacterial vaginosis in the first trimester of pregnancy, or even preconception.

What then remains to be demonstrated is that a policy for screening and treatment for asymptomatic bacterial vaginosis in pregnancy can reduce substantive measures of morbidity associated with neonatal immaturity, and that this results in cost savings to families and the health services. Large trials are needed which can determine the effect of a screening programme on neonatal mortality and major measures of morbidity such as intracranial damage and chronic lung disease. For example, in the NICHD MFMU trial, to reduce the incidence of neonatal morbidity by 25% (1.9% to 1.4%) with 90% power, significant at the 5% level, would require recruitment of at least 28,000 women.

Identification of specific subgroups who may benefit most from treatment may be improved further by an individual patient data analysis of the trials included in this review. If the detection and treatment of bacterial vaginosis can be shown to improve neonatal outcome, further trials will be necessary to determine the most effective antibiotic regimen.

Feedback

Klebanoff, October 2005

Summary

I have a couple of minor technical corrections. First, the NICHD trial (NICHD MFMU 2000) randomised women from 16 to 24 weeks, not from 18 to 24 weeks. In fact, these women were randomised not much later than those in Ugwumadu 2003.

Second, women with bacterial vaginosis plus Trichomonas were not eligible for the NICHD study included in this review. However, they were randomised into a parallel NICHD Trichomonas study .(1] In that study, we presented results separately for women who had Trichomonas only and women who had Trichomonas plus bacterial vaginosis. Since many other bacterial vaginosis trials did not screen for Trichomonas, and therefore probably randomised some women who had both, there is no reason to exclude such women recruited to our second study from your review.

Finally, our original draft of the paper for NICHD MFMU 2000 included data on neonatal mortality and morbidity. This table was removed at the request of the NEJM Editor. If you wish, I can investigate whether we can provide you with this additional data.

Reference (1] Klebanoff MA, Carey JC, Hauth JC, Hillier SL, Nugent RP, Thom EA, et al. Failure of metronidazole to prevent preterm delivery among pregnant women with asymptomatic Trichomonas vaginalis infection. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:487‐93.

(Summary of comments from Mark Klebanoff, October 2005)

Reply

Thank you very much for your comments. We have addressed each of your points in this update as follows: (1) the information about NICHD MFMU 2000 is now correct, women were enrolled between 16 to 24 weeks; (2) we have included the published data from the NICHD Trichomonas study (NICHD MFMU 2001); (3) data from NICHD MFMU 2000 on neonatal mortality and morbidity supplied by the authors have been included.

(Summary of response from Helen McDonald, November 2006)

Contributors

Mark Klebanoff

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 31 May 2012 | New search has been performed | Search updated 31 May 2012. |

| 31 May 2012 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Six new trials incorporated into the review (Darwish 2007; Giuffrida 2006; Larsson 2006; Mitchell 2009; Moniri 2009; Shennan 2006). Subgroup analyses re‐done. For this update there is no evidence for a difference between subgroups of women with previous preterm birth/no previous preterm birth or in women treated prior to 20 weeks' gestation/treated after 20 weeks' gestation for preterm pre‐rupture of membranes or in preterm birth before 37 weeks' gestation. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 3, 1997 Review first published: Issue 4, 1998

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 21 June 2011 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | New authors helped to prepare this review update. |

| 18 November 2010 | Amended | Search updated. Eleven new reports added to Studies awaiting classification. |

| 21 June 2010 | New search has been performed | Search updated ‐ no new trials identified. Eleven trial reports identified in the earlier search have been incorporated into the review. Four new studies have been included (Darwish 2007; Giuffrida 2006; Larsson 2006; Mitchell 2009) and four new studies have been excluded (Kurtzman 2008; Mitchell 2009a; Schoeman 2005; Ugwumadu 2006). One new study is ongoing (Subtil 2008) and additional reports were identified for McDonald 1997 and Shennan 2006. One trial, (Shennan 2006) previously excluded is now an included study due to unpublished relevant outcome data. This review is now comprised of 20 included studies, 20 excluded studies and one ongoing study. |

| 29 April 2008 | Amended | Corrected data input error for Morales 1994 for comparison 08.04. |

| 29 April 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 13 November 2006 | Feedback has been incorporated | Response to feedback from Mark Klebanoff added. |

| 25 September 2006 | New search has been performed | (1) Search updated May 2006. (2) Addition of co‐author Dr Adrienne Gordon. (3) Addition of extra neonatal data in NICHD MFMU 2000 study. (4) Addition of three new studies (NICHD MFMU 2001 with parallel data to NICHD MFMU 2000; Lamont 2003; Kiss 2004). (5) Analysis of clindamycin trials. (6) Analysis of abnormal vaginal flora trials (recruited on the basis of Nugent score 4‐10). (7) Analysis of treatment at less than 20 weeks' gestation. |

| 25 September 2006 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

Acknowledgements

Professor Mary Hannah, Women's College Hospital, University of Toronto, Ontario, Canada: co‐author on the first review.

Dr Rasiah Vigneswaran, deceased: co‐author to 2002.

Helen McDonald, was the contact author from 2003 to 2006, and was responsible for performing searches; personal communications with researchers; extracted and entered data; revised text and responded to comments, etc, for the second and third reviews.

Jacqueline Parsons: co‐author on the 2005 review.

Professor Caroline Crowther, Discipline of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, The University of Adelaide, for editorial advice.

Thanks to Elena Intra for translating the Giuffrida 2006 article from Italian into English.

As part of the pre‐publication editorial process, this updated review has been commented on by two peers (an editor and referee who is external to the editorial team), a member of the Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's international panel of consumers and the Group's Statistical Adviser.

Leanne Jones for her contributions to the revisions made to the final version of the 2012 update in response to editorial feedback.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Methods used to assess trials included in previous versions of this review

We selected all potential trials for eligibility according to the criteria specified in the protocol. Each of the review authors independently abstracted the information necessary for the review from the report and, where necessary, we sought additional information from the authors.

We assessed all trials for methodological quality using the standard Cochrane criteria. As there are a sufficient number of trials in the review, we stratified the trials by quality to explore the robustness of the findings. We calculated summary Peto odds ratios when appropriate (i.e. there was no evidence of significant heterogeneity) using the Cochrane Review Manager software (RevMan 2003).

Stratified analysis

As there are sufficient trials in the review, the comparisons are stratified to explore the effect of the intervention on the outcomes by the following factors:

oral versus vaginal antibiotics;

women with a previous preterm birth;

women with intermediate flora/bacterial vaginosis;

clindamycin versus placebo treatment;

treatment before 20 weeks' gestation.

It was not possible to stratify results into symptomatic versus asymptomatic bacterial vaginosis because in most trials, women with symptoms were treated with antibiotics and were therefore excluded.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Any antibiotic versus placebo/no treatment.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Failure of test of cure | 10 | 4403 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.42 [0.31, 0.56] |

| 1.1 Amoxicillin (oral) versus placebo | 1 | 81 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.73 [0.54, 0.98] |

| 1.2 Clindamycin (oral) versus placebo | 1 | 462 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.10 [0.07, 0.15] |

| 1.3 Clindamycin (vaginal) versus placebo | 3 | 1411 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.40 [0.30, 0.53] |

| 1.4 Clindamycin (vaginal) versus no treatment | 1 | 70 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.82 [0.37, 1.78] |

| 1.5 Metronidazole (oral) versus placebo | 3 | 2116 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.52 [0.30, 0.88] |

| 1.6 Metronidazole and erythromycin (oral) versus placebo | 1 | 263 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.37 [0.29, 0.47] |

| 2 Postpartum infection | 2 | 618 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.91 [0.26, 3.21] |

| 2.1 Clindamycin (vaginal) versus placebo | 1 | 375 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.64 [0.38, 1.06] |