Abstract

Objective

To assess the effect of lateral episiotomy, compared with no episiotomy, on obstetric anal sphincter injury in nulliparous women requiring vacuum extraction.

Design

A multicentre, open label, randomised controlled trial.

Setting

Eight hospitals in Sweden, 2017-23.

Participants

717 nulliparous women with a single live fetus of 34 gestational weeks or more, requiring vacuum extraction were randomly assigned (1:1) to lateral episiotomy or no episiotomy using sealed opaque envelopes. Randomisation was stratified by study site.

Intervention

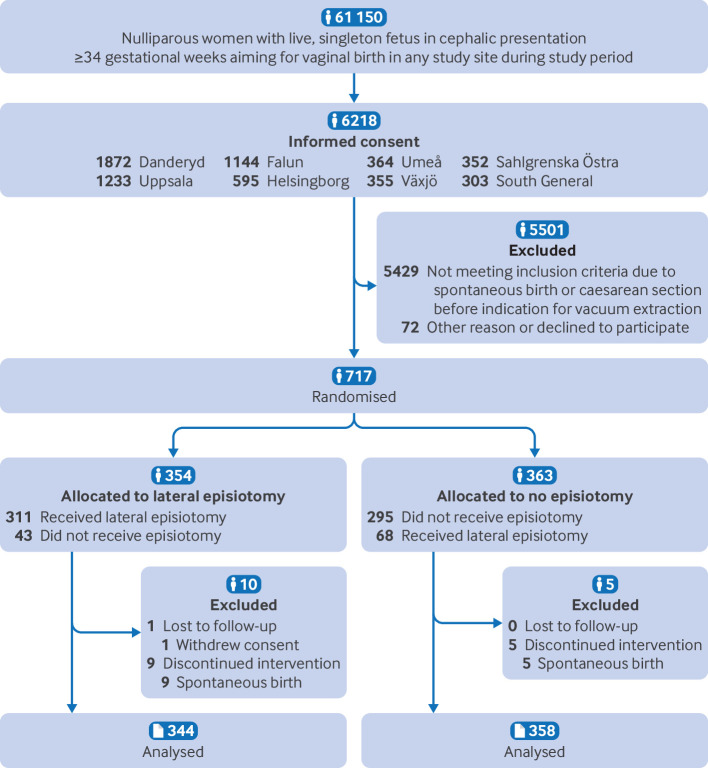

A standardised lateral episiotomy was performed during the vacuum extraction, at crowning of the fetal head, starting 1-3 cm from the posterior fourchette, at a 60° (45-80°) angle from the midline, and 4 cm (3-5 cm) long. The comparison was no episiotomy unless considered indispensable.

Main outcome measures

The primary outcome of the episiotomy in vacuum assisted delivery (EVA) trial was obstetric anal sphincter injury, clinically diagnosed by combined visual inspection and digital rectal and vaginal examination. The primary analysis used a modified intention-to-treat population that included all consenting women with attempted or successful vacuum extraction. As a result of an interim analysis at significance level P<0.01, the primary endpoint was tested at 4% significance level with accompanying 96% confidence interval (CI).

Results

From 1 July 2017 to 15 February 2023, 717 women were randomly assigned: 354 (49%) to lateral episiotomy and 363 (51%) to no episiotomy. Before vacuum extraction attempt, one woman withdrew consent and 14 had a spontaneous birth, leaving 702 for the primary analysis. In the intervention group, 21 (6%) of 344 women sustained obstetric anal sphincter injury, compared with 47 (13%) of 358 women in the comparison group (P=0.002). The risk difference was −7.0% (96% CI −11.7% to −2.5%). The risk ratio adjusted for site was 0.47 (96% CI 0.23 to 0.97) and unadjusted risk ratio was 0.46 (0.28 to 0.78). No significant differences were noted between groups in postpartum pain, blood loss, neonatal outcomes, or total adverse events, but the intervention group had more wound infections and dehiscence.

Conclusions

Lateral episiotomy can be recommended for nulliparous women requiring vacuum extraction to significantly reduce the risk of obstetric anal sphincter injury.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02643108.

Introduction

Obstetric anal sphincter injury is a serious complication to vaginal birth causing anal incontinence1 and reduced quality of life.2 Primiparity and instrumental birth are two major risk factors of obstetric anal sphincter injury.3 The obstetric anal sphincter injury rate in primiparous women varies between countries, with rates of 0.1-4% for spontaneous births and 6-24% for instrumental births in Europe, Canada, and the United States.4 5

The preventive effect of an episiotomy, an incision made in the tissue between the vaginal opening and the anus during childbirth, on obstetric anal sphincter injury is not clear. A Cochrane review of randomised controlled trials has concluded that routine episiotomy may increase the risk of obstetric anal sphincter injury in non-instrumental birth,6 while lateral or mediolateral episiotomy might prevent obstetric anal sphincter injury in vacuum extraction in nulliparous women, based on results from pooled observational studies.7 8 9 10 The most recent meta-analysis, published in 2022, which included 23 observational studies and two underpowered randomised controlled trials, reported an adjusted odds ratio of 0.51 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.42 to 0.84) for obstetric anal sphincter injury when a lateral or mediolateral episiotomy was performed compared with no episiotomy.7 However, other observational studies reported no effect,11 or the opposite effect.12 Episiotomy has also been associated with an increased risk of postpartum haemorrhage and pain.13 As such, some national guidelines state that a lateral or mediolateral episiotomy should be considered in nulliparous women requiring vacuum extraction,14 15 but also that the decision should be tailored to the circumstances,14 making the decision to do an episiotomy provider dependent. This uncertainty regarding treatment effect size and adverse effects is reflected in the internationally varying rates of episiotomy in instrumental births, from 17.1% in Denmark to 97.2% in Poland.4

Observational studies come with limitations. For instance, the differences in effect can be due to lack of standardisation regarding the type of episiotomy, where the angle and incision point have been deemed the most important traits.16 17 18 To date, no adequately sized randomised controlled trial on the protective effect of episiotomy on obstetric anal sphincter injury in vacuum extraction has been published.19 20 Hence, the Cochrane Collaboration and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence’s Evidence Search, among others, have stated that the protective effect of lateral or mediolateral episiotomy in vacuum extraction should be investigated in an adequately sized randomised controlled trial.6 8 13 Accordingly, we hypothesised that a routine lateral episiotomy reduces the risk of obstetric anal sphincter injury in nulliparous women requiring vacuum extraction. We performed a randomised controlled trial to assess the effect of lateral episiotomy compared with no episiotomy on obstetric anal sphincter injury in nulliparous women requiring vacuum extraction.

Methods

Study design

The Episiotomy in Vacuum Assisted delivery (EVA) trial was a randomised, parallel, open label, controlled trial comparing the effect of lateral episiotomy with no episiotomy (1:1), on obstetric anal sphincter injury in nulliparous women requiring vacuum extraction. Eight hospitals in Sweden conducted the study between 1 July 2017 and 15 February 2023. The study protocol has been published previously.21 The trial was approved by the regional ethical review board of Stockholm before the start (2015/1238-31/2) with amendments to approve additional participating hospitals (2017/1005-32, 2018/775-32, 2018/2291-32, 2019-02758, 2019-02758, and 2019-04427) and retrieval of data from the Swedish pregnancy register and the Swedish neonatal quality register (2023-02301-02). The trial was monitored by the Karolinska Trial Alliance 2017-20 and by two independent monitors 2021-23. The trial was registered in www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02643108) on 30 December 2015.

Results are reported according to CONSORT 2010 guidelines22 and TIDieR checklist.23

Participants

Inclusion criteria were nulliparous women with a singleton, live, cephalic presenting fetus at 34 gestational weeks or more, requiring vacuum extraction. Exclusion criteria were previous surgery for urinary or anal incontinence or for genital prolapse. Women here refers to people of female sex. All genders were eligible. Informed written and oral consent was obtained by attending midwives or physicians after gestational week 18, including during labour if the woman had adequate pain relief and time to reflect, based on the healthcare provider’s judgement.

Randomisation and masking

The decision to perform a vacuum extraction was made by the attending physician on obstetric indications independent of trial participation. This instruction was clearly made to physicians during trial education and to patients in the consent form, to avoid biased trial inclusion. Randomisation took place after the decision. The randomisation sequence was produced by Karolinska Trial Alliance using computer-based random permuted blocks of two to eight stratified by site. The allocation was done at a 1:1 ratio using consecutive opaque sealed envelopes to facilitate inclusion in medically urgent situations. After informed consent was confirmed, the sealed envelope was opened by the assisting nurse, midwife, or physician, and the allocation was read out loud in the delivery room. No masking was possible.

Procedures

In all women, the vacuum extraction procedure was prepared according to clinical routine, including intermittent bladder catheterisation, and ensuring pain relief in the form of epidural, pudendal, or local anaesthesia, or a combination of these. The extraction was done by the attending physician synchronously with maternal contractions and pushing until the fetal head was crowning, when a lateral episiotomy was done by the physician or midwife. The trial intervention was a standardised lateral episiotomy, beginning 1-3 cm from the posterior fourchette, at a 60° (45-80°) angle from the midline, and 4 cm (3-5 cm) long (fig 1), based on consensus16 and suggested protective trigonometric properties.17 18 The clinical staff at all sites received education on several occasions on how to perform the standardised lateral episiotomy before trial start. The comparison was no episiotomy unless considered indispensable. All women received verbal guidance and manual perineal support to prevent obstetric anal sphincter injury according to clinical routine, including intended slow delivery of the fetal head, hands-on perineal support, and warm compresses. Examination and suturing of vaginal and perineal injuries were managed according to clinical routine. Postnatal care was supplied according to clinical routine. In addition, perineal pain was assessed once between day one and seven after childbirth using a numerical rating scale (from 0=no pain to 10=worst possible pain) and a questionnaire covering complications was sent out at two months after childbirth (supplementary table S3).

Fig 1.

Illustration of a standardised lateral episiotomy in the EVA trial

Outcomes

The primary outcome was obstetric anal sphincter injury, defined as a third or fourth degree perineal injury involving the external or internal anal sphincter muscles, or both, as defined by the diagnoses O702 and O703, requiring surgical repair, in the Swedish version of the International Classification of Diseases 10th edition. Obstetric anal sphincter injury was the primary outcome in the published meta-analyses,7 8 and carries well known risks of both short and long term pelvic floor sequelae.24 Obstetric anal sphincter injury rate is also an established marker of quality of care, comparable between hospitals and countries.4 6 25 The diagnosis was made clinically by the attending physician on site through visual inspection and digital vaginal and rectal examination immediately after childbirth, according to Swedish guidelines.15 Exploratory maternal outcomes were vaginal or perineal injury other than obstetric anal sphincter injury (ie, intact perineum, first degree injury, and second degree perineal injury including episiotomy, allocated or not), duration of hospital stay (days), perineal pain (once between days one and seven after delivery reported on a numerical rating scale from 0=no pain to 10=worst imaginable pain), and birth experience (once between days one and seven after delivery reported on a numerical rating scale from 1=worst possible overall experience to 10=best possible overall experience). Perineal pain of 7 or more was used as an arbitrary indicator of severe pain. Childbirth experience of 3 or less was used as an indicator of a negative childbirth experience.26 From the two month questionnaire, questions regarding perineal pain, surgical wound problems, infections, and re-admission were included (supplementary material). Secondary outcomes are patient reported outcomes collected at 12 months, with results anticipated in 2025.21

Exploratory neonatal outcomes were an Apgar score of less than 7 at 5 mins, metabolic acidosis defined as umbilical artery pH of less than 7.05 or base deficit of 12 mmol/L or more, admission to neonatal intensive care, shoulder dystocia, scalp haematoma, fetal fracture, obstetric brachial plexus palsy, hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy, and neonatal seizures. Safety maternal outcomes were postpartum haemorrhage (blood loss of ≥1000 mL) and severe perineal pain (numerical rating scale of ≥7, measured once between days one and seven).

Demographics, maternal and childbirth characteristics, and outcomes were retrieved from the Swedish pregnancy register.27 Data not available in the register were registered in an electronic case report form for each participant. Second stage duration was defined as the time between full cervical dilatation and birth. Neonatal data were retrieved from the Swedish pregnancy register and the Swedish neonatal quality register.28 Data for vaginal and perineal injuries were registered in the electronic case report form. The primary outcome of obstetric anal sphincter injury was cross checked with data from the Swedish pregnancy register. Two individuals had discrepant results. In both cases, an erroneous procedure code in the Swedish pregnancy register did not match the diagnostic codes or text in the medical record. Therefore, the outcome obstetric anal sphincter injury was based on the electronic case report form.

Adverse and serious adverse events

An adverse event was defined as a complication to the trial intervention or perineal injury including perineal wound infection, dehiscence, granuloma or symptomatic scarring, severe perineal pain (requiring opioids), or fistula formation in the vagina, anus, or perineum during the first eight weeks postpartum. A serious adverse event was any event resulting in maternal death within 42 days postpartum or neonatal death within 28 days after birth, or that was life threatening, required admission to intensive care unit, or that resulted in persistent or significant disability. Participants were instructed to contact the hospital where they gave birth in case of symptoms of adverse events. Adverse events were thus identified through self-referral. In addition to this, medical records were screened for adverse events up to two months after childbirth and self-reported complications were collected from the questionnaire at two months.

Statistical analyses

The original sample size was based on the meta-analysis by Lund and colleagues,8 reporting a 50% reduction of obstetric anal sphincter injury in vacuum extraction in nulliparous women, when a lateral or mediolateral episiotomy was performed. We used mean rate of obstetric anal sphincter injury in vacuum extraction in Sweden in 2015, according to the Swedish medical birth register, to hypothesise that a 50% reduction of obstetric anal sphincter injury from 12.4% to 6.2% could be detected with 80% power and a P<0.05 with 344 women in each group using a two sided χ2 test. With an estimated 3% loss to follow-up, 355 women in each group (total n=710) was needed. After the Swedish network for national clinical studies in obstetrics and gynaecology (www.snaks.se) advised that a smaller difference could be clinically important, we applied for ethical approval for an amendment in 2017, after the trial had started, to include 1400 women to show a 30% reduction from 12.4% to 7.8%. In 2019, we aimed for the initial sample size (710 women) due to slow recruitment. An interim analysis was done in 2020 according to prespecified criteria to detect a difference in line with van Bavel and colleagues,21 29 reporting a reduction from 14.0% to 2.5% of obstetric anal sphincter injury with episiotomy in nulliparous women requiring vacuum extraction. To show this difference with 80% power and P<0.01, 350 women were needed, a total which was attained in 2020. In case this difference was found, we had a priori decided to stop the trial. Stopping criteria were not met.

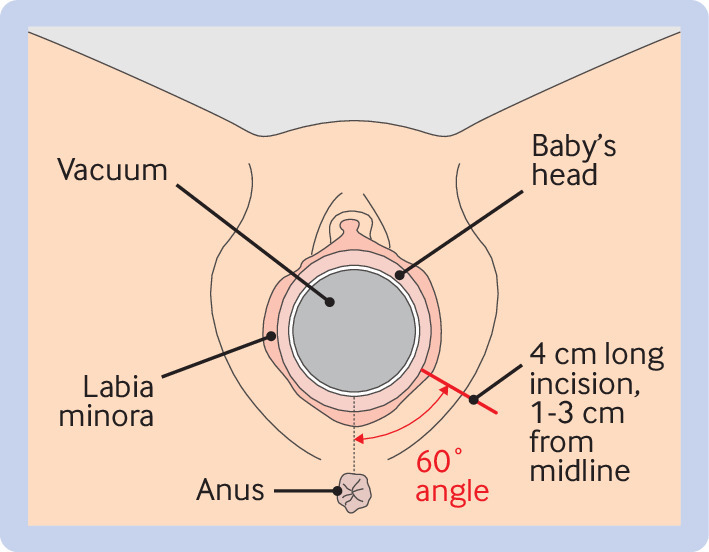

For the main comparative analyses, we used a modified intention-to-treat population, defined as all consenting randomised women with vacuum extraction or vacuum extraction attempt. A vacuum extraction attempt was defined as having the vacuum cup applied to the fetal head. One woman withdrew consent before the vacuum cup was applied and was excluded. Women who had been randomised but had a spontaneous birth before the vacuum cup was applied were also excluded (fig 2). This modification to the intention-to-treat population was motivated by the primary objective of the trial, because women with spontaneous birth were deemed to have lost the main inclusion criterium (vacuum assisted delivery). The primary analysis was based on allocation regardless of received treatment. We also analysed the outcome of obstetric anal sphincter injury on the total intention-to-treat (all consenting women), per protocol (consenting women delivered with vacuum extraction who received the assigned treatment), as treated (consenting women with attempted or successful vacuum extraction), and safety populations (all consenting women as treated).

Fig 2.

CONSORT flowchart of the modified intention-to-treat population

Baseline characteristics are presented with medians and ranges or numbers and proportions. The prespecified primary efficacy analysis was the unadjusted comparison of the primary outcome obstetric anal sphincter injury in the lateral episiotomy group compared with the no episiotomy group on the modified intention-to-treat population with a two sided χ2 test. Due to the performed interim analysis, P<0.04 was deemed necessary for the primary outcome of obstetric anal sphincter injury to account for multiple testing. The risk difference and risk ratio between the groups were calculated with 96% CI using the method of Miettinen and Nurminen.30 Risk differences of less than 0 and risk ratios of less than 1 indicated lower risks for the outcome in the intervention group versus the control group. Since the randomisation was stratified by site, adjustment for site effects was done by using a mixed effects Poisson regression model to estimate the risk ratio with 96% CI, with site and site × treatment as random effects. The interaction term was included to account for treatment effect heterogeneity across sites. Site specific treatment effects were calculated using the best linear unbiased predictions of the random effects and visualised in a forest plot. In a prespecified sensitivity analysis, we also adjusted for maternal age, height, body mass index, country of birth, fetal position, and operator skills (categorised into resident, specialist gynaecologist, or specialist obstetrician), by inclusion as covariates in the mixed effects Poisson model. Number needed to treat were calculated with 96% CI and number needed to harm were calculated with 95% CI.

Maternal and neonatal categorical exploratory outcomes were compared with two sided χ2 test, or Fisher’s exact test for rare events, and t test for continuous variables. Maternal safety outcomes, including adverse events and serious adverse events, were calculated for the modified intention-to-treat population based on allocated treatment and for the safety population based on received treatment. All analyses except the primary outcome were unadjusted, P<0.05 was considered significant, and risk difference and risk ratio with 95% CI were calculated. A detailed statistical analysis plan was set before data lock on 27 June 2023 and is available as supplementary information. Changes from the protocol included the use of Poisson regression to estimate the relative risk instead of logistic regression to estimate the odds ratio. Analyses were performed by independent, endpoint masked statisticians using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC, USA).

Patient and public involvement

At the initiation of this trial, patient or public involvement was not a compulsory requirement and, at the time, no relevant patient organisations existed. Therefore, layperson patients or the public were not directly involved in the design or conduct of this trial. However, in 2015 the Swedish government commissioned the healthcare regions, research councils, and authorities to improve prevention of obstetric anal sphincter injury. The Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services (SBU), with the contribution of patient representatives, published a report in 2018 of prioritised research areas within the field of maternal birth injuries. The report stated that preventative measures against obstetric anal sphincter injury was one of the most important research questions.31 In addition, along the conduct of this trial, a qualitative research project assessed the views of consenting and non-consenting women regarding the recruitment process.32 To increase the impact of the results from this trial, both for care providers and researchers, as well as for patients and public, the results will be disseminated in conference presentations, posters, and mass media, and shared across social media, pregnancy podcasts, and companion blogs to involve pregnant women and their families.

Results

During the recruitment period of 1 July 2017 to 15 February 2023, 61 150 women were eligible at the eight study sites, of which 6218 women consented to participate if vacuum extraction was required. Of these, a total of 717 women required vacuum extraction and were randomly assigned by 255 different physicians. In all, 354 (49%) women were allocated to lateral episiotomy and 363 (51%) women were allocated to no episiotomy (fig 2). One woman from the intervention group withdrew consent before the vacuum extraction and was excluded. Spontaneous birth occurred before the vacuum was applied in nine women allocated to lateral episiotomy and in five women allocated to no episiotomy. These women were also excluded from the modified intention-to-treat population. Therefore, the modified intention-to-treat population included 344 (49%) women allocated to lateral episiotomy and 358 (51%) women allocated to no episiotomy (fig 2).

Of the 344 women allocated to lateral episiotomy, 310 (90%) received a lateral episiotomy and 34 (10%) received no episiotomy. Of 358 women allocated to no episiotomy, 291 (81%) received no episiotomy, while 67 (19%) received a lateral episiotomy. The two allocation groups were similar regarding maternal (table 1) and childbirth characteristics (table 2). Among women allocated to lateral episiotomy, 22 (6%) were delivered by caesarean section after vacuum extraction was unsuccessful, of which four received an episiotomy before conversion. Among women allocated to no episiotomy, five (1%) were delivered by caesarean section after vacuum extraction was unsuccessful. None of these women received an episiotomy.

Table 1.

Maternal demographic and baseline characteristics (modified intention-to-treat population)

| Characteristics | Lateral episiotomy (n=344) | No episiotomy (n=358) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years), median (range) | 31 (19-43) | 31 (21-47) |

| Age (years): | ||

| <19 | 1 (<1) | 0 |

| 20-24 | 22 (6) | 20 (6) |

| 25-29 | 100 (29) | 115 (32) |

| 30-34 | 149 (43) | 134 (37) |

| ≥35 | 72 (21) | 89 (25) |

| Country of birth: | ||

| Sweden | 266 (77) | 286 (80) |

| Other European | 33 (10) | 20 (6) |

| Outside Europe | 23 (7) | 26 (7) |

| Missing | 22 (6) | 26 (7) |

| Educational level: | ||

| None or less than nine years | 1 (<1) | 2 (1) |

| Compulsory school (nine years) | 7 (2) | 11 (3) |

| Upper secondary school (gymnasium) | 104 (30) | 76 (21) |

| University/college | 205 (60) | 231 (65) |

| Missing | 27 (8) | 38 (11) |

| Height (cm): | ||

| Median (range) | 166 (150-185) | 167 (147-182) |

| <160 | 34 (10) | 44 (13) |

| Missing | 4 (1) | 7 (2) |

| Body mass index: | ||

| Median (range) | 23.7 (17.7-50.1) | 23.7 (16.6-44.5) |

| ≤18.4 | 6 (2) | 8 (2) |

| 18.5-24.9 | 207 (60) | 207 (58) |

| 25.0-29.9 | 88 (26) | 99 (28) |

| 30.0-4.9 | 23 (7) | 20 (6) |

| ≥35.0 | 11 (3) | 15 (4) |

| Missing | 9 (3) | 9 (3) |

| Pregnancy complications: | ||

| PROM/PPROM | 50 (15) | 60 (17) |

| Hypertensive disease/pre-eclampsia | 33 (10) | 38 (11) |

| Gestational and pregestational diabetes mellitus | 20 (6) | 26 (7) |

| Intrauterine growth restriction/oligohydramniosis | 11 (3) | 12 (3) |

| Accelerated growth/macrosomia | 9 (3) | 12 (3) |

| Study site: | ||

| Uppsala University Hospital | 92 (27) | 92 (26) |

| Danderyd University Hospital | 80 (23) | 83 (23) |

| Falun Hospital | 69 (20) | 78 (22) |

| Helsingborg Hospital | 37 (11) | 33 (9) |

| Umeå University Hospital | 15 (4) | 20 (6) |

| South General Hospital | 19 (6) | 16 (5) |

| Östra Sahlgrenska University Hospital | 14 (4) | 19 (5) |

| Växjö Hospital | 18 (5) | 17 (5) |

Data are number (percentage), unless otherwise specified.

PROM=prelabour rupture of membranes; PPROM=preterm, prelabour rupture of membranes.

Table 2.

Childbirth characteristics (modified intention-to-treat population)

| Childbirth characteristics | Lateral episiotomy (n=344) | No episiotomy (n=358) |

|---|---|---|

| Gestational age at randomisation: | ||

| Days, median (range) | 283 (249-296) | 284 (250-296) |

| ≥40 weeks | 226 (66) | 247 (69) |

| Mode of onset: | ||

| Induction | 133 (39) | 154 (43) |

| Spontaneous | 211 (61) | 204 (57) |

| Epidural anaesthesia | 312 (91) | 324 (91) |

| Oxytocin augmentation | 334 (97) | 346 (97) |

| Second stage duration: | ||

| hh:min, median (range) | 3:41 (00:06-10:07) | 3:39 (00:06-08:46) |

| Indication for vacuum extraction*: | ||

| Fetal distress | 156 (45) | 169 (47) |

| Labour dystocia/no progression | 174 (51) | 164 (46) |

| Maternal exhaustion | 68 (20) | 77 (22) |

| Correction of fetal position | 3 (1) | 3 (1) |

| Other | 0 | 4 (1) |

| Fetal station: | ||

| At ischial spines | 7 (2) | 8 (2) |

| Below ischial spines | 89 (26) | 86 (24) |

| Above pelvic floor | 177 (52) | 199 (56) |

| At pelvic floor | 71 (21) | 65 (18) |

| Fetal position: | ||

| Occiput anterior | 288 (84) | 307 (86) |

| Occiput posterior | 28 (8) | 31 (9) |

| Other | 8 (2) | 6 (2) |

| Missing | 8 (2) | 6 (2) |

| Operator skills: | ||

| Resident | 133 (39) | 154 (43) |

| Specialist Gynaecologist | 69 (20) | 66 (18) |

| Specialist Obstetrician | 142 (41) | 138 (39) |

| No of pulls: | ||

| <6 | 316 (92) | 327 (91) |

| ≥6 | 27 (8) | 31 (9) |

| Missing | 1 (<1) | 0 |

| Vacuum cup detachment, any | 37 (11) | 30 (8) |

| Conversion to caesarean section | 22 (6) | 5 (1) |

| Birthweight (g): | ||

| Median (range) | 3565 (2260-5025) | 3580 (2438-4850) |

| Mean (SD) | 3573 (461) | 3591 (454) |

| ≥4000 | 60 (17) | 59 (17) |

| Head circumference (cm): | ||

| Median (range) | 36 (31-40) | 35 (31-44) |

| Mean (SD) | 35.4 (2.2) | 35.5 (1.6) |

| ≥38 | 4 (1) | 9 (3) |

Data are number (percentage), unless otherwise specified.

More than one indication optional.

Obstetric anal sphincter injury occurred in 21 (6%) of the women allocated to lateral episiotomy and in 47 (13%) of the women allocated to no episiotomy (P=0.002), with a risk difference of −7.0% (96% CI −11.7% to −2.5%) and risk ratio of 0.46 (96% CI 0.28 to 0.78). The adjusted risk ratio (adjusted for study site) was 0.47 (96% CI 0.23 to 0.97) (table 3). Results were largely consistent across sites, although the crude event rates were numerically larger in the episiotomy group for two of eight sites (supplementary figure S1). Similar results were also observed in a prespecified sensitivity analysis adjusting for maternal age, height, body mass index, country of birth, fetal position, and operator skills (adjusted risk ratio 0.49 (96% CI 0.24 to 0.99)). Number needed to treat with episiotomy was 14.3 (96% CI 8.6 to 40.0) to avoid one obstetric anal sphincter injury. In the per protocol population, obstetric anal sphincter injury occurred in 20 (6%) of 311 women who received lateral episiotomy and 38 (13%) of 295 women with no episiotomy (risk difference −6.5% (95% CI −11.4% to −1.8%); risk ratio 0.50 (95% CI 0.30 to 0.84)). Obstetric anal sphincter injury for the total intention-to-treat population had consistent results with the modified intention-to-treat and per protocol analyses. In the as treated population, obstetric anal sphincter injury occurred in 29 (8%) of 377 women with lateral episiotomy and 39 (12%) of 325 women with no episiotomy, which did not reach statistical significance (risk difference −4.3% (95% CI −8.9% to 0.2%)) (supplementary table S1).

Table 3.

Primary and exploratory outcomes (modified intention-to-treat population)

| Outcomes | Lateral episiotomy, no (%) (n=344) | No episiotomy, no (%) (n=358) | P value | Risk difference, %* | Risk ratio* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome | |||||

| OASI | 21 (6) | 47 (13) | 0.002 | −7.0 (−11.7 to −2.5) | 0.46 (0.28 to 0.78) |

| OASI adjusted† | - | - | 0.031 | — | 0.47 (0.23 to 0.97) |

| Exploratory outcomes, maternal | |||||

| Intact perineum | 12 (4) | 6 (2) | 0.16 | 1.8 (−0.6 to 4.5) | 2.08 (0.79 to 5.48) |

| Caesarean section | 12 | 4 | — | — | — |

| First degree injury | 8 (2) | 46 (13) | <0.001 | −10.5 (−14.6 to −6.7) | 0.18 (0.09 to 0.38) |

| Caesarean section | 5 | 1 | — | — | — |

| Second degree injury or episiotomy | 303 (88) | 259 (72) | <0.001 | 15.7 (9.9 to 21.4) | 1.22 (1.13 to 1.31) |

| Caesarean section | 5 | 0 | — | — | — |

| Postpartum haemorrhage ≥1000 mL | 51 (17) | 60 (19) | 0.54 | −1.8 (−7.8 to 4.1) | 0.90 (0.64 to 1.26) |

| Postpartum haemorrhage (mL), mean (SD) | 647 (436) | 654 (510) | 0.86 | — | — |

| Missing | 37 | 33 | — | — | — |

| Perineal pain‡, NRS ≥7 | 144 (49) | 142 (45) | 0.44 | 3.1 (−4.8 to 11.0) | 1.07 (0.90 to 1.27) |

| Pain‡, median (range) | 6 (1-10) | 6 (1-10) | 0.20 | — | — |

| Missing | 47 | 45 | — | — | — |

| Birth experience‡, NRS ≤3 | 32 (12) | 42 (14) | 0.32 | −2.8 (−8.3 to 2.8) | 0.81 (0.52 to 1.24) |

| Birth experience‡, median (range) | 7 (1-10) | 7 (1-10) | 0.39 | — | — |

| Missing | 66 | 64 | — | — | — |

| Hospital stay ≥3 days | 64 (19) | 76 (22) | 0.37 | −2.8 (−8.7 to 3.2) | 0.87 (0.65 to 1.17) |

| Hospital stay, days, mean (SD) | 2.25 (1.22) | 2.36 (1.32) | 0.23 | — | — |

| Missing | 5 | 7 | — | — | — |

| Exploratory outcomes, neonatal | |||||

| Apgar <7 at 5 min | 6 (2) | 12 (3) | 0.18 | −1.6 (−4.3 to 0.8) | 0.52 (0.20 to 1.37) |

| Missing | 0 | 1 | - | - | - |

| Metabolic acidosis§ | 22 (9) | 26 (10) | 0.69 | −1.1 (−6.5 to 4.4) | 0.90 (0.52 to 1.54) |

| Missing | 108 | 108 | - | - | - |

| NICU admission | 31 (9) | 34 (10) | 0.61 | −0.5 (−4.8 to 3.9) | 0.94 (0.60 to 1.51) |

| Shoulder dystocia | 0 | 3 (1) | 0.09 | −0.8 (−2.4 to 0.3) | n/a |

| Scalp haematoma | 19 (6) | 11 (3) | 0.11 | 2.4 (−0.6 to 5.7) | 1.79 (0.87 to 3.71) |

| Fracture | 3 (1) | 1 (<1) | 0.30 | 0.6 (−0.8 to 2.3) | 3.11 (0.33 to 29.79) |

| OBPP | 1 (<1) | 0 | 0.31 | 0.3 (−0.8 to 1.6) | n/a |

| HIE | 1 (<1) | 1 (<1) | 0.98 | 0.3 (−0.8 to 1.6) | 1.04 (0.07 to 16.57) |

| Seizures | 1 (<1) | 2 (1) | 0.59 | −0.3 (−1.5 to 1.0) | 0.52 (0.05 to 5.71) |

CI=confidence interval; HIE=hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy; NICU=neonatal intensive care unit; NRS=numerical rating scale (1-10); OASI=obstetric anal sphincter injury; OBPP=obstetric brachial plexus palsy; SD=standard deviation.

Primary outcome had 96% confidence intervals and exploratory outcomes had 95% confidence intervals.

Adjusted for study site.

Pain and birth experience were assessed by numerical rating scales in the postnatal ward (pain 0-10, where 0=no pain to 10=worst imaginable pain and birth experience 1-10, where 1=worst possible overall experience and 10=best possible overall experience).

Metabolic acidosis is defined as umbilical artery pH <7.05 or base deficit 12.0 mmol/L or more.

Intact perineum was rare and most of these participants gave birth by caesarean section. In the intervention group, first degree injuries were significantly less frequent and second degree injuries including episiotomy (allocated or not) were significantly more frequent, compared with the comparison group. No statistically significant differences were noted for postpartum haemorrhage, postpartum perineal pain, birth experience, hospital stay, or neonatal outcomes (table 3).

Self-referral of wound infection and dehiscence were significantly more common in the intervention group than in the control group. Number needed to harm was 21.7 (95% CI 12.5 to 125) for infection and 16.9 (10.2 to 41.7) for wound dehiscence. Total self-referred adverse events did not differ significantly between the groups and no significant difference was noted in surgical treatment such as wound re-suturing or extirpation of granuloma. Serious adverse events and persistent incapacity were rare and did not differ significantly between groups (table 4). The differences in wound complications increased in the safety population (supplementary table S2).

Table 4.

Adverse events and serious adverse events (self-referral) (modified intention-to-treat population)

| Outcomes | Lateral episiotomy, no (%) (n=344) | No episiotomy, no (%) (n=358) | P value | Risk difference, % (95% CI) | Risk ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adverse events | |||||

| Wound infection | 32 (9) | 17 (5) | 0.02 | 4.6 (0.8 to 8.5) | 1.96 (1.11 to 3.46) |

| Wound dehiscence | 32 (9) | 12 (3) | 0.001 | 6.0 (2.4 to 9.8) | 2.78 (1.45 to 5.30) |

| Granuloma or scarring | 14 (4) | 21 (6) | 0.27 | −1.8 (−5.2 to 1.5) | 0.69 (0.35 to 1.34) |

| Surgical treatment* | 25 (7) | 20 (6) | 0.36 | 1.7 (−2.0 to 5.5) | 1.30 (0.74 to 2.30) |

| Severe pain | 21 (6) | 26 (7) | 0.54 | −1.2 (−4.9 to 2.6) | 0.84 (0.48 to 1.47) |

| Fistula formation | 1 (<1) | 0 | 0.31 | 0.3 (−0.8 to 1.6) | N/A |

| Any of the above | 74 (22) | 62 (17) | 0.16 | 4.2 (−1.7 to 10.0) | 1.24 (0.92 to 1.68) |

| Serious adverse events | |||||

| Maternal death between days 0-42 | 0 | 0 | N/A | 0 | N/A |

| Maternal critical care† | 1 (<1) | 1 (<1) | 0.98 | 0.0 (−1.3 to 1.4) | 1.04 (0.07 to 16.57) |

| Persistent incapacity‡ | 4 (1) | 1 (<1) | 0.37 | 0.9 (−0.6 to 2.7) | 4.16 (0.47 to 37.06) |

| Neonatal death between days 0-28 | 0 | 0 | N/A | 0 | N/A |

N/A=not applicable.

Including re-suturing of wound or extirpation of granuloma.

One woman who required intensive care due to extreme blood loss and deranged coagulation because she refused to take blood for religious reasons; and one woman with septicaemia.

Persistent incapacity is defined as still ongoing after one year or with sequelae and were in these five cases one woman who required intensive care due to extreme blood loss and deranged coagulation because she refused to take blood for religious reasons; one woman with fistula formation; and two women with wound dehiscence; and one with granuloma that the site principal investigator deemed had recovered but with sequelae.

For self-reported complications within two months after childbirth, no significant difference in pain assessment was noted but women in the intervention group significantly more often used analgesics after discharge from the hospital. No significant difference was noted in duration of analgesics use. Similar to the results from self-referral, the intervention group reported more wound complications, including wound infection and wound re-suturing (table 5).

Table 5.

Self-reported complications within two months after childbirth (modified intention-to-treat population)

| Complications | Lateral episiotomy(n=252) | No episiotomy (n=245) | P value | Risk difference, % (95% CI) | Risk ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain, NRS, mean (SD) | 2.3 (1.7) | 2.2 (1.6) | 0.82 | — | — |

| Pain, NRS ≥7 | 10 (4) | 7 (3) | 0.50 | 1.1 (−2.3 to 4.6) | 1.39 (0.54 to 3.59) |

| Analgesics* | |||||

| Analgesics, any use | 215 (85) | 178 (73) | <0.001 | 12.7 (5.5 to 19.7) | 1.17 (1.07 to 1.29) |

| Days, mean (SD) | 14.7 (9.0) | 13.7 (8.3) | 0.26 | — | — |

| Duration ≥7 days | 146 (68) | 120 (67) | 0.92 | 0.5 (−8.7 to 9.8) | 1.01 (0.88 to 1.16) |

| Wound complication† | 75 (30)† | 43 (18)§ | 0.001 | 12.2 (4.7 to 19.5) | 1.70 (1.22 to 2.36) |

| Caesarean section | 3 | 1 | — | — | — |

| Re-suturing | 14 (6) | 3 (1) | 0.01 | 4.3 (1.1 to 8.0) | 4.54 (1.32 to 15.59) |

| Fistula formation | 1 (<1) | 0 | 0.19 | 0.3 (−0.8 to 1.6) | — |

| Infection, any of below | 42 (17) | 34 (14) | 0.39 | 2.8 (−3.6 to 9.1) | 1.20 (0.79 to 1.82) |

| Urinary tract infection | 5 (2) | 9 (4) | 0.25 | −1.7 (−5.0 to 1.4) | 0.54 (0.18 to 1.58) |

| Genital infection | 9 (4) | 12 (5) | 0.45 | −1.3 (−5.2 to 2.4) | 0.72 (0.31 to 1.69) |

| Wound infection | 24 (9) | 11 (5) | 0.03 | 5.0 (0.5 to 9.7) | 2.11 (1.05 to 4.20) |

| Endometritis | 5 (2) | 10 (4) | 0.17 | −2.1 (−5.6 to 1.1) | 0.48 (0.17 to 1.39) |

| Sepsis | 1 (<1) | 1 (<1) | 0.98 | 0 (−1.9 to 1.8) | 0.97 (0.06 to 15.34) |

| Other infection | 7 (3) | 8 (3) | 0.74 | −0.5 (−3.8 to 2.8) | 0.84 (0.31 to 2.29) |

| Re-admission | 27 (11) | 29 (12) | 0.67 | −1.1 (−6.7 to 4.4) | 0.90 (0.55 to 1.47) |

Data are number (percentage), unless otherwise specified. Unadjusted risk difference and risk ratio are presented.

NRS=numerical rating scale (1-10).

After discharge.

Wound complication was defined as an affirmative answer to “describe your discomfort/complication by choosing the area/areas affected”: ticked box “wound” (supplementary material).

Discussion

Principal findings

In this randomised trial of 702 nulliparous women requiring vacuum extraction, the rate and risk of obstetric anal sphincter injury was more than halved in women allocated to lateral episiotomy compared with no episiotomy. No significant differences were noted in blood loss, perineal pain, birth experience, hospital stay duration, short term neonatal outcomes, or total adverse events. Women allocated to lateral episiotomy had more wound infections, dehiscence, and re-suturing, but when including extirpation of granulomas, surgical treatment did not significantly differ between groups.

Strengths and limitations

This study is the first adequately sized randomised controlled trial to assess the effect of episiotomy in nulliparous women requiring vacuum extraction, filling the previous knowledge gap.6 8 13 Other strengths of this trial are the small differences between results in the modified intention-to-treat, intention-to-treat, per protocol, and as treated analyses, the excellent protocol adherence, and the representative population and staff from eight hospitals evenly distributed over Sweden.

A limitation of this trial is that the obstetric anal sphincter injury diagnosis was not masked for the allocation because this was deemed impossible as an episiotomy would be apparent. Instead, the sites followed Swedish guidelines recommending a joint assessment of two care providers when diagnosing perineal injuries.15 One of these providers was often the same physician who performed the vacuum extraction. This reflects clinical practice but could infer a risk of detection bias, especially if the provider had a strong opinion of the effect of episiotomy. Since vacuum extraction was performed unplanned at all hours, an independent investigator was not deemed feasible. Ultrasound immediately after childbirth to objectively assess obstetric anal sphincter injury was neither considered feasible,33 nor is it recommended.34 Nevertheless, to check the diagnostic accuracy, as is recommended in the postnatal period in high risk births,34 an ongoing substudy blinded for allocation in four sites using 3D endoanal and endovaginal ultrasound at 6-12 months postpartum is expected to have results in 2025.21

Comparison with other studies

Two previous randomised controlled trials have assessed the effect of episiotomy in operative vaginal delivery.19 20 Neither of these was adequately sized to confirm or refute an effect. The level of risk reduction and number needed to treat in our trial confirm the results of pooled observational studies.7 8 Nevertheless, the confidence interval for number needed to treat was wide, which may be due to a limited sample size or a variation in effect also seen in observational studies.8 24 The average number needed to treat may be difficult to interpret because the average does not refer to a particular individual, which may carry a higher or lower baseline risk of obstetric anal sphincter injury. However, the average number needed to treat should be acceptable also in settings where episiotomy is used restrictively.35 The rate of obstetric anal sphincter injury in the total study population is also consistent with the current rate among Swedish primiparous women delivered with vacuum extraction.36

Episiotomy has been associated with greater blood loss and perineal pain,13 although this was not confirmed in our trial. Likewise, no clear evidence suggests that lateral episiotomy significantly affected birth experience, hospital stay duration, or short term neonatal outcomes. However, the confidence intervals were wide which makes equipoise for these outcomes uncertain. Women allocated to episiotomy reported more wound infection, coherent with previous observational studies.37 38 This complication might have been prevented if prophylactic antibiotics had been given, as shown in the ANODE trial from 2019.38 During our trial, Swedish guidelines recommended prophylactic antibiotics only for obstetric anal sphincter injury,15 which potentially could have imbalanced wound complications in the groups. Given the results from the ANODE trial and our trial, prophylactic antibiotics should be given in vacuum extraction.38

The major objection against routine episiotomy is the risk of an unnecessary cut, perhaps causing a larger injury than needed. Our study supports that routine lateral episiotomy will result in a higher proportion of women sustaining a second degree injury, instead of a first degree injury or obstetric anal sphincter injury. The proportion of women with intact perineum was similar in both groups, partly due to more conversions to caesarean section in the intervention group. Conversion to caesarean section was in most cases done before the intervention, therefore, this difference was deemed to result from chance. It is also not plausible that episiotomy would increase the risk of failed vacuum extraction.

A potential pitfall in this trial is the uneven non-adherence to allocated treatment, which was more common in the no episiotomy group. Episiotomy was in these cases usually motivated by fetal distress or imminent tearing, as restrictive practice implies. In comparison with previous trials,19 20 the protocol adherence in the no episiotomy group was excellent. Notably, the clinical judgement of who did and did not need an episiotomy did not improve the reduction of obstetric anal sphincter injury as seen in the as treated analysis. This effect is consistent with a previous meta-analysis reporting that an episiotomy rate of over 75% had a greater protective effect.8 Admittedly, it seems possible to maintain a low rate of episiotomy and a low rate of obstetric anal sphincter injury in some settings,20 which suggests that other factors, such as operator skills, may contribute.39

Conclusions and policy implications

Until now, guidelines have advised clinicians to consider episiotomy in nulliparous women requiring vacuum extraction, without a clear recommendation. With the results of our study, a lateral episiotomy can be recommended for nulliparous women requiring vacuum extraction to significantly lower the risk of obstetric anal sphincter injury. However, before recommending routine lateral episiotomy in nulliparous women requiring vacuum extraction, more evidence is needed regarding long term patient reported outcomes. For example, outcomes such as quality of life and pelvic floor function after vacuum extraction with and without lateral episiotomy. These outcomes will be assessed in the planned follow-up of the EVA trial. The follow-up results can inform the design of an optimal prophylactic strategy.

What is already known on this topic

Obstetric anal sphincter injury is a serious complication to vaginal birth, leading to anal incontinence and reduced quality of life, and is more common in nulliparous women delivered with vacuum extraction

Lateral or mediolateral episiotomy might reduce obstetric anal sphincter injury in nulliparous women delivered with vacuum extraction by approximately 50%

The effect of a lateral or mediolateral episiotomy in instrumental births in nulliparous women has been called on to be investigated in an adequately sized randomised controlled trial

What this study adds

This trial provides evidence that the rate of obstetric anal sphincter injury in nulliparous women requiring vacuum extraction can be significantly reduced with a lateral episiotomy

No differences were noted between groups in postpartum pain, blood loss, neonatal outcomes, or total adverse events, but episiotomy was significantly associated with an increase in wound infection and dehiscence

Lateral episiotomy can be recommended in nulliparous women requiring vacuum extraction to reduce the rate of obstetric anal sphincter injury

Acknowledgments

We thank all the women who consented to participate in this trial. We thank the Swedish Research Council (2016-00526), the Stockholm Region (FoUI-960261/2021), the Uppsala-Örebro Research Council (RFR-939428), clinical staff, management, study coordinators at the trial sites, the Swedish pregnancy register, the Swedish neonatal quality register, and the Swedish Network for National Clinical Studies in Obstetrics and Gynaecology (www.snaks.se) for facilitating this trial. We also thank the statisticians Nils-Gunnar Pehrsson, Mattias Molin, and Henrik Imberg at Statistiska Konsultgruppen Sweden AB.

Web extra.

Extra material supplied by authors

Web appendix: Extra material supplied by authors

Contributors: SBW conceived the research idea and led the trial. SBW, HKK, MJ, and SH attained funding for the trial. All authors were principal investigators or investigators and contributed to the completion of the trial. SB, MJ, SH, and SBW are responsible for the statistical analysis plan. SB, VA, MJ, SH, ACW, ER, ÅL, HF, and SBW checked the original data. SB and SBW directly accessed and verified the underlying data and analyses. SB wrote the first draft of the manuscript with input from MJ, SH, ÅL, HKK, and SBW. All authors approved of the submitted version. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted. SBW acts as a guarantor.

Funding: The trial was funded by the Swedish Research Council (2016-00526), the Stockholm Region (FoUI-960261/2021), and the Uppsala-Örebro Research Council (RFR-939428). The funders had no role in the study design or in the collection, analysis, interpretation of data, writing of the report, or decision to submit the article for publication.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/disclosure-of-interest/ and declare: funding from the Swedish Research Council (2016-00526), the Stockholm Region (FoUI-960261/2021), and the Uppsala-Örebro Research Council (RFR-939428); no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; and no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Transparency: SBW affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned and registered have been explained.

Dissemination to participants and related patient and public communities: The results were partly presented for the first time on 28 August 2023 in Trondheim, Norway, at a meeting organised by the Nordic Federation of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, to invited laypersons, obstetricians, gynaecologists, and midwives. The results were partly presented a second time on 11 October 2023 in Paris, France, at a congress organised by the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, to invited patient association representatives as well as decision makers, obstetricians, gynaecologists, and midwives. We plan to disseminate results to the public through the media departments and websites of the authors’ institutions, and by sharing the results across social media, pregnancy podcasts, and companion blogs to involve pregnant women and their families in discussing the implications and further research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Ethical approval

The trial was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board of Stockholm before start (2015/1238-31/2) with amendments to approve additional participating hospitals (2017/1005-32, 2018/775-32, 2018/2291-32, 2019-02758, 2019-02758, 2019-04427) and retrieval of data from the Swedish pregnancy register and the Swedish neonatal quality register (2023-02301-02).

Data availability statement

The study protocol and the statistical analysis plan is available with publication as supplementary material. Deidentified individual participant data and a data dictionary defining each field in the set will be made available to others for meta-analysis with investigator support after approval of a proposal (sophia.brismar-wendel@regionstockholm.se) and with a signed data access agreement.

References

- 1. Bols EM, Hendriks EJ, Berghmans BC, Baeten CG, Nijhuis JG, de Bie RA. A systematic review of etiological factors for postpartum fecal incontinence. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2010;89:302-14. 10.3109/00016340903576004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services. SBU Systematic Review Summaries. Anal sphincter injuries: a systematic review and assessment of medical, social and ethical aspects. Stockholm: Swedish Council on Health Technology Assessment (SBU). 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pergialiotis V, Bellos I, Fanaki M, Vrachnis N, Doumouchtsis SK. Risk factors for severe perineal trauma during childbirth: An updated meta-analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2020;247:94-100. 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2020.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Blondel B, Alexander S, Bjarnadóttir RI, et al. Euro-Peristat Scientific Committee . Variations in rates of severe perineal tears and episiotomies in 20 European countries: a study based on routine national data in Euro-Peristat Project. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2016;95:746-54. 10.1111/aogs.12894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ramm O, Woo VG, Hung YY, Chen HC, Ritterman Weintraub ML. Risk factors for the development of obstetric anal sphincter injuries in modern obstetric practice. Obstet Gynecol 2018;131:290-6. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jiang H, Qian X, Carroli G, Garner P. Selective versus routine use of episiotomy for vaginal birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;2:CD000081. 10.1002/14651858.CD000081.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Okeahialam NA, Wong KW, Jha S, Sultan AH, Thakar R. Mediolateral/lateral episiotomy with operative vaginal delivery and the risk reduction of obstetric anal sphincter injury (OASI): A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Urogynecol J 2022;33:1393-405. 10.1007/s00192-022-05145-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lund NS, Persson LK, Jangö H, Gommesen D, Westergaard HB. Episiotomy in vacuum-assisted delivery affects the risk of obstetric anal sphincter injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2016;207:193-9. 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2016.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ankarcrona V, Zhao H, Jacobsson B, Brismar Wendel S. Obstetric anal sphincter injury after episiotomy in vacuum extraction: an epidemiological study using an emulated randomised trial approach. BJOG 2021;128:1663-71. 10.1111/1471-0528.16663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Desplanches T, Marchand-Martin L, Szczepanski ED, et al. Mediolateral episiotomy and risk of obstetric anal sphincter injuries and adverse neonatal outcomes during operative vaginal delivery in nulliparous women: a propensity-score analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022;22:48. 10.1186/s12884-022-04396-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schreiber H, Mevorach N, Sharon-Weiner M, Farladansky-Gershnabel S, Shechter Maor G, Biron-Shental T. The role of mediolateral episiotomy during vacuum-assisted vaginal delivery with soft cup devices. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2021;303:885-90. 10.1007/s00404-020-05809-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Frenette P, Crawford S, Schulz J, Ospina MB. Impact of Episiotomy During Operative Vaginal Delivery on Obstetrical Anal Sphincter Injuries. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2019;41:1734-41. 10.1016/j.jogc.2019.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sagi-Dain L, Sagi S. Morbidity associated with episiotomy in vacuum delivery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG 2015;122:1073-81. 10.1111/1471-0528.13439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Murphy DJ, Strachan BK, Bahl R, Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists . Assisted Vaginal Birth: Green-top Guideline No. 26. BJOG 2020;127:e70-112. 10.1111/1471-0528.16336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.LÖF. www.backenbottenutbildning.se [Pelvic floor education] [Web-based education]. Swedish Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Swedish Association of Midwives, Swedish patient insurance (LÖF); 2019 updated 2022.

- 16. Kalis V, Laine K, de Leeuw JW, Ismail KM, Tincello DG. Classification of episiotomy: towards a standardisation of terminology. BJOG 2012;119:522-6. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2011.03268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gonzalez-Díaz E, Fernández Fernández C, Gonzalo Orden JM, Fernández Corona A. Which characteristics of the episiotomy and perineum are associated with a lower risk of obstetric anal sphincter injury in instrumental deliveries. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2019;233:127-33. 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2018.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Stedenfeldt M, Pirhonen J, Blix E, Wilsgaard T, Vonen B, Øian P. Episiotomy characteristics and risks for obstetric anal sphincter injuries: a case-control study. BJOG 2012;119:724-30. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2012.03293.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Murphy DJ, Macleod M, Bahl R, Goyder K, Howarth L, Strachan B. A randomised controlled trial of routine versus restrictive use of episiotomy at operative vaginal delivery: a multicentre pilot study. BJOG 2008;115:1695-702, discussion 1702-3. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.01960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sagi-Dain L, Kreinin-Bleicher I, Bahous R, et al. Is it time to abandon episiotomy use? A randomized controlled trial (EPITRIAL). Int Urogynecol J 2020;31:2377-85. 10.1007/s00192-020-04332-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bergendahl S, Ankarcrona V, Leijonhufvud Å, et al. Lateral episiotomy versus no episiotomy to reduce obstetric anal sphincter injury in vacuum-assisted delivery in nulliparous women: study protocol on a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2019;9:e025050. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D, CONSORT Group . CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ 2010;340:c332. 10.1136/bmj.c332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ 2014;348:g1687. 10.1136/bmj.g1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Okeahialam NA, Sultan AH, Thakar R. The prevention of perineal trauma during vaginal birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2023;230. 10.1016/j.ajog.2022.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fernando R, Sultan A, Freeman R, et al. Green-top Guideline No. 29. Third- and Fourth-degree Perineal Tears, Management London. Royal College of Obstetricians & Gyneacologists, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Falk M, Nelson M, Blomberg M. The impact of obstetric interventions and complications on women’s satisfaction with childbirth a population based cohort study including 16,000 women. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2019;19:494. 10.1186/s12884-019-2633-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Stephansson O, Petersson K, Björk C, Conner P, Wikström AK. The Swedish Pregnancy Register - for quality of care improvement and research. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2018;97:466-76. 10.1111/aogs.13266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Norman M, Källén K, Wahlström E, Håkansson S, SNQ Collaboration . The Swedish Neonatal Quality Register - contents, completeness and validity. Acta Paediatr 2019;108:1411-8. 10.1111/apa.14823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. van Bavel J, Hukkelhoven CWPM, de Vries C, et al. The effectiveness of mediolateral episiotomy in preventing obstetric anal sphincter injuries during operative vaginal delivery: a ten-year analysis of a national registry. Int Urogynecol J 2018;29:407-13. 10.1007/s00192-017-3422-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Miettinen O, Nurminen M. Comparative analysis of two rates. Stat Med 1985;4:213-26. 10.1002/sim.4780040211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services. SBU) . Prioritised research areas within the fields of prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of maternal birth injuries. Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ericson J, Anagrius C, Rygaard A, Guntram L, Brismar Wendel S, Hesselman S. Women’s experiences of receiving information about and consenting or declining to participate in a randomized controlled trial involving episiotomy in vacuum-assisted delivery: a qualitative study. Trials 2021;22:658. 10.1186/s13063-021-05624-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Huber M, Larsson C, Harrysson M, et al. Use of endoanal ultrasound in detecting obstetric anal sphincter injury immediately after birth. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2023;102:389-95. 10.1111/aogs.14514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bellussi F, Dietz HP. Postpartum ultrasound for the diagnosis of obstetrical anal sphincter injury. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM 2021;3(6s):100421. 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2021.100421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ankarcrona V, Hesselman S, Kopp Kallner H, Brismar Wendel S. Attitudes and knowledge regarding episiotomy use and technique in vacuum extraction: A web-based survey among doctors in Sweden. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2022;269:62-70. 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2021.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Socialstyrelsen. Statistik om graviditeter, förlossningar och nyfödda [Statistics on pregnancies, births, and newborns]. Stockholm, Sweden: National Board of Health and Welfare. 2023. https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/statistik-och-data/statistik/alla-statistikamnen/graviditeter-forlossningar-och-nyfodda/.

- 37. Jones K, Webb S, Manresa M, Hodgetts-Morton V, Morris RK. The incidence of wound infection and dehiscence following childbirth-related perineal trauma: A systematic review of the evidence. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2019;240:1-8. 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2019.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Knight M, Chiocchia V, Partlett C, et al. ANODE collaborative group . Prophylactic antibiotics in the prevention of infection after operative vaginal delivery (ANODE): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2019;393:2395-403. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30773-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bergendahl S, Lindberg P, Brismar Wendel S. Operator experience affects the risk of obstetric anal sphincter injury in vacuum extraction deliveries. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2019;98:787-94. 10.1111/aogs.13538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Web appendix: Extra material supplied by authors

Data Availability Statement

The study protocol and the statistical analysis plan is available with publication as supplementary material. Deidentified individual participant data and a data dictionary defining each field in the set will be made available to others for meta-analysis with investigator support after approval of a proposal (sophia.brismar-wendel@regionstockholm.se) and with a signed data access agreement.