Abstract

Background

Checkpoint inhibitor therapy has demonstrated overall survival benefit in multiple tumor types. Tumor mutational burden (TMB) is a predictive biomarker for response to immunotherapies. This study evaluated the efficacy of nivolumab+ipilimumab in multiple tumor types based on TMB status evaluated using either tumor tissue (tTMB) or circulating tumor DNA in the blood (bTMB).

Patients and methods

Patients with metastatic or unresectable solid tumors with high (≥10 mutations per megabase) tTMB (tTMB-H) and/or bTMB (bTMB-H) who were refractory to standard therapies were randomized 2:1 to receive nivolumab+ipilimumab or nivolumab monotherapy in an open-label, phase 2 study (CheckMate 848; NCT03668119). tTMB and bTMB were determined by the Foundation Medicine FoundationOne® CDx test and bTMB Clinical Trial Assay, respectively. The dual primary endpoints were objective response rate (ORR) in patients with tTMB-H and/or bTMB-H tumors treated with nivolumab+ipilimumab.

Results

In total, 201 patients refractory to standard therapies were randomized: 135 had tTMB-H and 125 had bTMB-H; 82 patients had dual tTMB-H/bTMB-H. In patients with tTMB-H, ORR was 38.6% (95% CI 28.4% to 49.6%) with nivolumab+ipilimumab and 29.8% (95% CI 17.3% to 44.9%) with nivolumab monotherapy. In patients with bTMB-H, ORR was 22.5% (95% CI 13.9% to 33.2%) with nivolumab+ipilimumab and 15.6% (95% CI 6.5% to 29.5%) with nivolumab monotherapy. Early and durable responses to treatment with nivolumab+ipilimumab were seen in patients with tTMB-H or bTMB-H. The safety profile of nivolumab+ipilimumab was manageable, with no new safety signals.

Conclusions

Patients with metastatic or unresectable solid tumors with TMB-H, as determined by tissue biopsy or by blood sample when tissue biopsy is unavailable, who have no other treatment options, may benefit from nivolumab+ipilimumab.

Trial registration number

Keywords: Combination therapy, Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor, Biomarker, Circulating tumor DNA - ctDNA, Tumor mutation burden - TMB

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

Tumor mutational burden (TMB) represents the total number of somatic mutations in the tumor genome and is a predictive marker for immunotherapies for many types of solid tumors. TMB can be assessed from tumor tissue (tTMB) or circulating tumor DNA in the bloodstream (bTMB). Although blood samples are easier to collect and process than tissue samples, some tumors may not shed a sufficient amount of DNA to allow TMB assessment from blood. Some studies have demonstrated an association between high bTMB and improved outcomes, but further research is needed to characterize its clinical utility and concordance with tTMB.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

Nivolumab+ipilimumab showed clinical efficacy and a manageable safety profile in patients with advanced or metastatic solid tumors with high (≥10 mut/Mb) tTMB or bTMB that were refractory to standard therapies. Objective response rates were greatest in patients with high-tTMB tumors. bTMB continues to be evaluated as a biomarker; analytical factors, such as tumor fraction, influence the overall bTMB score and need to be further defined.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

This study suggests that nivolumab+ipilimumab is a potential treatment option for patients with advanced or metastatic high-TMB solid tumors, as determined by tissue biopsy, or by blood sample when tissue biopsy is unavailable, who have no available treatment options.

Introduction

The tumor mutational landscape refers to the genetic mutations present in a tumor, which may include alterations in DNA sequences that lead to changes in the function of genes, which can drive tumor growth, metastasis, and resistance to treatment.1,3 Tumor mutational burden (TMB) represents the total number of somatic mutations in the tumor genome and is generally defined as the number of somatic mutations (mut) per megabase (Mb) in tumor cells.1 TMB correlates with neoantigen load, thus tumors with high TMB (TMB-H) are expected to be more immunogenic and responsive to immunotherapies than tumors with low TMB (TMB-L).4 5 Clinical studies have demonstrated that TMB is a predictive biomarker for immunotherapies across a range of solid tumors.6,13 In June 2020, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved pembrolizumab for the treatment of patients with solid tumors with TMB-H (≥10 mut/Mb),14 as determined from tumor tissue biopsies, based on data from the KEYNOTE-158 trial.6

TMB can be determined from tumor tissue (tTMB) or from circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) extracted from blood samples (bTMB).15 16 Although tissue samples allow for assessment of tissue architecture, disease stage, and tumor microenvironment, as well as screening for multiple biomarkers by different methods, they may be difficult to obtain and may not represent the intratumoral and intertumoral heterogeneity.16 Blood samples are easier to collect and process by clinicians, and the sampling procedure is less invasive for patients16; however, they do not allow for disease staging and histologic assessment. Additionally, certain tumors, although classified as tTMB-H through tissue biopsy, may not shed a sufficient amount of DNA into the circulation to be detected as bTMB-H. Results from B-F1RST and B-FAST, two studies that prospectively evaluated bTMB as a predictive biomarker for first-line atezolizumab monotherapy in patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), showed that although bTMB≥16 mut/Mb was associated with improved outcomes, the results were not statistically significant.17 18 Further research is needed to better understand the utility of bTMB, to establish concordance between bTMB and tTMB, and to determine the cutoffs that allow their use as predictive biomarkers of response to immunotherapies.

To address these questions, we present here efficacy and safety analyses from the final database lock (June 2022) of CheckMate 848 (NCT03668119), a prospective, randomized, noncomparative, open-label, phase 2 study of nivolumab with or without ipilimumab in patients with metastatic or unresectable solid tumors with tTMB-H and/or bTMB-H who were refractory to standard therapies.

Methods

Study design and participants

The study consisted of prescreening, screening, randomization, treatment, and follow-up phases (online supplemental figure 1A). Eligible patients were immunotherapy-naïve and had metastatic or unresectable, histologically, or cytologically confirmed solid tumors that were refractory to standard therapies per local treatment guidelines or had no available standard treatment, that is, patients were in the salvage setting. Patients had tTMB≥10 mut/Mb, assessed by FoundationOne® CDx (Foundation Medicine, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA), as described previously,11 and/or bTMB≥10 mut/Mb assessed by a Clinical Trial Assay (Foundation Medicine) and validated by Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments, as described previously (online supplemental figure 1B).19 Prior results of tTMB-H/bTMB-H obtained with these assays were acceptable for eligibility purposes. If the only available result was tissue based, a blood sample was provided for central TMB testing, and if the only available result was blood based, a tissue sample was provided for central TMB testing. If neither a tTMB nor bTMB result was available, both tissue and blood samples were provided for central TMB testing. TMB results obtained from any other assays were not acceptable for eligibility.

Other eligibility criteria included age ≥12 years, an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of ≤1 (patients >16 years old with solid tumors), Karnofsky Performance Score ≥80 (patients >16 years with primary CNS tumors), or Lansky Performance Score ≥80 (patients aged 12–16 years only). Patients must have had measurable disease for response assessment per RECIST V.1.1 for solid tumors other than CNS20 and Response Assessment in Neuro-Oncology (RANO) criteria for primary CNS malignancies.21

Patients were excluded if they had melanoma, NSCLC, or renal cell carcinoma because immunotherapy treatment options are generally widely available for these populations. Patients with hematological malignancy were also excluded. Patients with brain metastases were eligible if there was no MRI evidence of progression for at least 4 weeks after prior treatment completion and within 28 days prior to first dose of study drug. There must have been no requirement for immunosuppressive doses of systemic corticosteroids (>10 mg/day prednisone equivalent for adults or >0.25 mg/kg daily prednisone equivalent for adolescents) for at least 2 weeks prior to study drug administration.

Patients were randomized 2:1 to receive either nivolumab 240 mg every 2 weeks+ipilimumab 1 mg/kg every 6 weeks or nivolumab 480 mg every 4 weeks (online supplemental figure 1). Treatment continued for up to 24 months. Patients treated with nivolumab 480 mg every 4 weeks had the option to receive nivolumab 240 mg every 2 weeks and ipilimumab 1 mg/kg every 6 weeks following disease progression.

Outcomes

The dual primary endpoints were objective response rate (ORR) assessed by blinded independent central review (BICR) in patients with tTMB-H or bTMB-H tumors treated with nivolumab+ipilimumab. The primary endpoint efficacy criterion for a positive outcome was an ORR estimate with the lower bound of the two-sided 95% CI being >10% in the tTMB-H or bTMB-H populations (10% was considered a typical response rate for standard of care chemotherapy in this patient population at the time the study was planned). The study was not designed for comparisons between treatment arms. Secondary endpoints included but were not limited to, duration of response (DOR), time to response, overall survival (OS), progression-free survival (PFS), and investigator-assessed DOR and ORR. ORRs in patients grouped according to programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression (PD-L1 expression ≥1% or PD-L1 expression <1%) or microsatellite instability (MSI) status (high MSI [MSI-H] or non-MSI-H) were also evaluated as exploratory endpoints. Safety endpoints included rate of adverse events (AEs), immune-mediated AEs, and deaths.

Assessments

For solid tumors, response was assessed using RECIST V.1.1, whereas response in CNS tumors was assessed using RANO criteria. Safety was assessed per Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v.5.0 continuously throughout treatment and for at least 100±7 days after treatment discontinuation.

Statistical analysis

The final primary endpoint analysis was performed ≥12 months after all patients with tTMB-H and/or bTMB-H in the salvage setting had been randomized. Enrolment into the bTMB-H cohort closed in December 2019, after which no further patients, regardless of bTMB status, were included in the bTMB-H analysis population. Safety, PFS, and OS analyses were also reported after ≥12 months’ follow-up, per the study protocol. The safety population included all patients who received ≥1 dose of study drug.

For the primary endpoint, BICR-assessed ORR in the nivolumab+ipilimumab treatment arm was analyzed by response rates and their corresponding two-sided 95% exact CIs using the Clopper-Pearson method. The clinically meaningful target ORR was assumed as 40% for patients with TMB-H treated with nivolumab+ipilimumab. This was based on ORRs of 45.3% (CheckMate 227) and 46% (CheckMate 032) seen in previous studies in patients with lung cancer and TMB-H treated with nivolumab+ipilimumab.11 13 A total of 76 TMB-evaluable patients treated with nivolumab+ipilimumab were required for each of the tTMB-H and bTMB-H populations to give 95% CIs for ORR, with 10% for the lower bound (typical for standard of care chemotherapy in this refractory population). In addition, 76 TMB-H evaluable patients treated with nivolumab+ipilimumab in each of the tTMB-H and bTMB-H populations allowed for a more precise estimation of DOR. Thus, sample size determination was based primarily on providing precise estimates of ORR for patients with tTMB-H or bTMB-H treated with nivolumab+ipilimumab, rather than based on power considerations. The nivolumab monotherapy arm was a non-comparative arm enrolled to evaluate contribution of components. A 2:1 randomization ratio was chosen because it was expected that nivolumab+ipilimumab would be more effective than nivolumab monotherapy, and this ratio would limit the number of patients receiving nivolumab monotherapy. Given the expected ~40% concordance between bTMB-H and tTMB-H observed in this study, ~183 patients were planned to be randomized to nivolumab+ipilimumab or nivolumab monotherapy in a 2:1 ratio to have sufficient patients in the primary efficacy populations.

Patients were stratified using a TMB cut-off of ≥16 mut/Mb to ensure an even distribution of patients with relatively low or TMB-H and to allow further analysis based on TMB cutoffs. Patients were also stratified by prior lines of therapy to ensure even distribution of patients who had failed first-line treatment versus second-line treatment and beyond between the two arms.

Results

Baseline characteristics and patient disposition

Of the 1954 prescreened patients, 212 were randomized, with 201 in the salvage setting. All 201 patients were included in the primary analysis population (patients with ≥12 months of follow-up); 135 had tTMB-H and 125 had bTMB-H; 82 patients had both tTMB-H and bTMB-H (online supplemental figure 2 and online supplemental table 1). Of the patients with tTMB-H, 88 were randomized to receive nivolumab+ipilimumab and 47 to receive nivolumab monotherapy. Of the patients with bTMB-H, 80 were randomized to nivolumab+ipilimumab and 45 to nivolumab monotherapy. Patient demographics and baseline characteristics are summarized in table 1, and tumor types are summarized in online supplemental tables 2 and 3. No pediatric patients were randomized. Patients received a median of two lines of prior therapy. The most common cancer types were colorectal (10.8%), cervical (7.5%), small cell lung (7.5%), breast (7.1%), and uterine (7.1%). Minimum follow-up was 12.4 and 28.5 months in patients with tTMB-H and bTMB-H, respectively.

Table 1. Patient demographics and baseline characteristics in the primary analysis population.

| tTMB-H (n=135)* | bTMB-H (n=125)* | |||

| NIVO+IPI (n=88) | NIVO (n=47) | NIVO+IPI (n=80) | NIVO (n=45) | |

| Age—years | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 59.8 (11.2) | 57.2 (13.6) | 59.5 (11.7) | 56.6 (10.7) |

| Median (range) | 61.5 (33–81) | 58 (22–82) | 61 (30–79) | 58 (37–74) |

| Sex—no (%) | ||||

| Male | 39 (44.3) | 23 (48.9) | 39 (48.8) | 17 (37.8) |

| Female | 49 (55.7) | 24 (51.1) | 41 (51.3) | 28 (62.2) |

| Region—no (%) | ||||

| Europe | 54 (61.4) | 33 (70.2) | 51 (63.8) | 34 (75.6) |

| North America | 5 (5.7) | 1 (2.1) | 9 (11.3) | 1 (2.2) |

| Rest of the world | 29 (32.9) | 13 (27.6) | 20 (25.1) | 10 (22.2) |

| Patients with prior systemic therapy—no (%) | 83 (94.3) | 45 (95.7) | 80 (100) | 44 (97.8) |

| Number of prior systemic regimens—no (%) | ||||

| 1 | 36 (40.9) | 18 (38.3) | 22 (27.5) | 15 (33.3) |

| 2 | 17 (19.3) | 8 (17.0) | 25 (31.3) | 8 (17.8) |

| 3 | 8 (9.1) | 10 (21.3) | 9 (11.3) | 9 (20.0) |

| ≥4 | 22 (25.0) | 9 (19.1) | 24 (30.0) | 12 (26.7) |

| Median (range) | 2.0 (0–10) | 2.0 (0–8) | 2.0 (1–9) | 2.0 (0–7) |

201 patients were in the primary analysis population; 82 patients had both tTMB-H and bTMB-H, and the bTMB-H population was randomized before December 20, 2019. bTMB-H, high blood ; IPI, ipilimumab; NIVO, nivolumab; , standard deviation; tTMB-H, high tissue

bTMB-Hhigh blood tumor mutational burdenIPIipilimumabNIVOnivolumabtTMB-Hhigh tissue tumor mutational burden

In patients with tTMB-H, median duration of treatment was 5.1 and 4.6 months with nivolumab+ipilimumab and nivolumab monotherapy, respectively; 13.6% and 36.2% of patients with tTMB-H, respectively, received subsequent therapy after disease progression, including 25.5% who crossed over to nivolumab+ipilimumab.

In patients with bTMB-H, median duration of treatment was 2.4 and 3.7 months with nivolumab+ipilimumab and nivolumab monotherapy, respectively; 13.8% and 40.0% of patients with bTMB-H, respectively, received subsequent therapy after disease progression, including 28.9% who crossed over to nivolumab+ipilimumab.

Efficacy

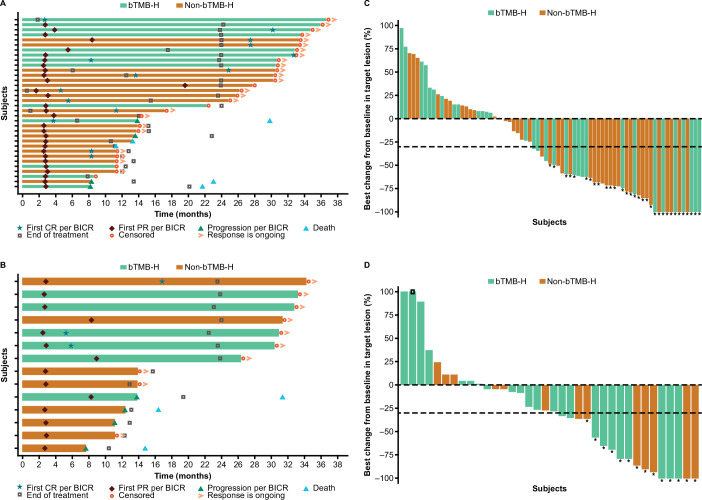

The primary endpoint was met in both the tTMB-H and bTMB-H cohorts. In patients with tTMB-H, ORR was 38.6% (95% CI 28.4% to 49.6%) and 29.8% (95% CI 17.3% to 44.9%) in those treated with nivolumab+ipilimumab and nivolumab monotherapy, respectively (table 2). Early and durable responses were observed in patients with tTMB-H regardless of bTMB-H status in both treatment arms (figure 1, table 2).

Table 2. BOR, ORR, and DOR by treatment arm and tTMB-H or bTMB-H status in the primary analysis population.

| tTMB-H (n=135)* | bTMB-H (n=125)* | |||

| NIVO+IPI (n=88) | NIVO (n=47) | NIVO+IPI (n=80) | NIVO (n=45) | |

| BOR—no (%) | ||||

| CR | 13 (14.8) | 3 (6.4) | 4 (5.0) | 2 (4.4) |

| PR | 21 (23.9) | 11 (23.4) | 14 (17.5) | 5 (11.1) |

| SD | 13 (14.8) | 4 (8.5) | 8 (10.0) | 6 (13.3) |

| PD | 30 (34.1) | 21 (44.7) | 41 (51.3) | 20 (44.4) |

| Non-CR/PD | 1 (1.1) | 0 | 1 (1.3) | 1 (2.2) |

| UTD | 10 (11.4) | 8 (17.0) | 12 (15.0) | 11 (24.4) |

| ORR—(%), 95% CI | 34 (38.6) 28.4–49.6 | 14 (29.8) 17.3–44.9 | 18 (22.5) 13.9–33.2 | 7 (15.6) 6.5–29.5 |

| DOR—months | ||||

| Median (95% CI) | NA | NA | NA (10.2 to NA) | NA (5.5 to NA) |

| Range | 5.4–33.9+ | 5.0–31.4+ | 5.4–33.9+ | 5.5–30.6+ |

| Events—no/no (%) | 6/34 (17.6) | 4/14 (28.6) | 5/18 (27.8) | 1/7 (14.3) |

| Patients with DOR of at least: | ||||

| 9 months—% (95% CI) | 90 (73 to 97) | 78 (46 to 92) | 83 (55 to 94) | 86 (33 to 98) |

| 12 months—% (95% CI) | 78 (57 to 90) | 70 (38 to 88) | 76 (47 to 90) | 86 (33 to 98) |

201 patients were in the primary analysis population; 82 patients had both tTMB-H and bTMB-H.BOR, best overall response; bTMB-H, high blood ; , confidence interval; CR, complete response; DOR, ; IPI, ipilimumab; NA, not available; NIVO, nivolumab; ORR, ; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; , stable disease; tTMB-H, high tissue ; UTD, unable to determine.

BORbest overall responsebTMB-Hhigh blood tumor mutational burdenCRcomplete responseDORduration of responseIPIipilimumabNAnot availableNIVOnivolumabORRobjective response ratePDprogressive diseasePRpartial responseSDstable diseasetTMB-Hhigh tissue tumor mutational burdenUTDunable to determine

Figure 1. DOR in patients with tTMB-H treated with (A) nivolumab+ipilimumab or (B) nivolumab monotherapy, and best change from baseline in target lesion size in patients with tTMB-H treated with (C) nivolumab+ipilimumab or (D) nivolumab. Horizontal bars in A, B represent progression-free survival. Asterisks in C, D represent responders. Square symbol in D represents percent change truncated to 100%. Dashed horizontal reference lines in C and D indicate a 30% reduction, consistent with a RECIST V.1.1 response. BICR, blinded independent central review; bTMB-H, high blood TMB; CR, complete response; DOR, duration of response; PR, partial response; tTMB-H, high tissue tumor mutational burden.

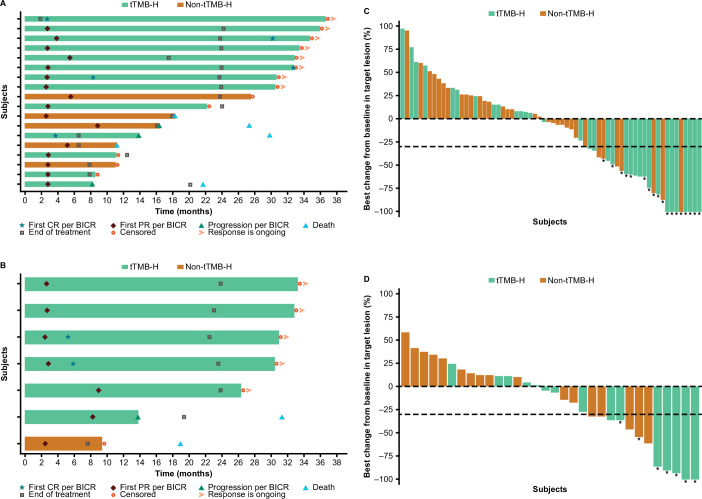

In patients with bTMB-H, ORRs were numerically lower than those in patients with tTMB-H; ORR was 22.5% (95% CI 13.9% to 33.2%) and 15.6% (95% CI 6.5% to 29.5%) with nivolumab+ipilimumab and nivolumab monotherapy, respectively (table 2). Early and durable responses in both treatment arms were most common among patients with dual bTMB-H/tTMB-H status (figure 2, table 2).

Figure 2. DOR in patients with bTMB-H treated with (A) nivolumab+ipilimumab or (B) nivolumab monotherapy, and best change from baseline in target lesion size in patients with bTMB-H treated with (C) nivolumab+ipilimumab or (D) nivolumab monotherapy. Horizontal bars in A, B represent progression-free survival. Asterisks in C, D represent responders. Dashed horizontal reference lines in C, D indicate a 30% reduction, consistent with a RECIST V.1.1 response. BICR, blinded independent central review; bTMB-H, high blood tumor mutational burden; CR, complete response; DOR, duration of response; PR, partial response; tTMB-H, high tissue tumor mutational burden.

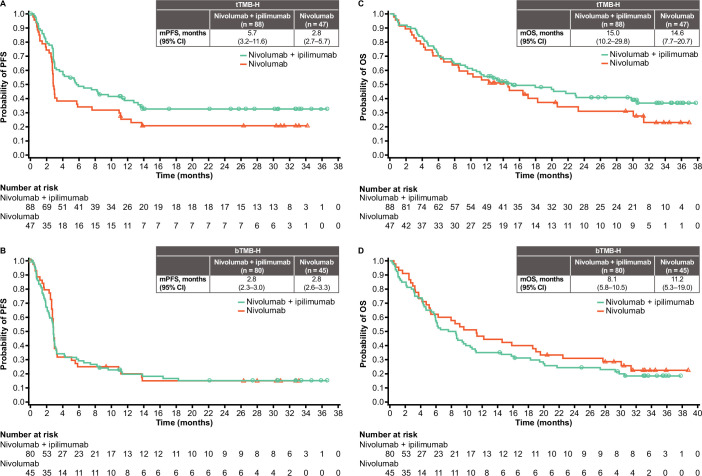

There was a trend toward longer median PFS and OS in patients with tTMB-H versus those with bTMB-H in the nivolumab+ipilimumab arm (figure 3). Median OS in patients with tTMB-H was 15.0 (95% CI 10.2 to 29.8) and 14.6 (95% CI 7.7 to 20.7) months in the nivolumab+ipilimumab and nivolumab monotherapy arms, respectively; in patients with bTMB-H, median OS was 8.1 (95% CI 5.8 to 10.5) and 11.2 (95% CI 5.3 to 19.0) months, respectively.

Figure 3. PFS (per BICR) in patients with (A) tTMB-H and (B) bTMB-H tumors, and OS in patients with (C) tTMB-H and (D) bTMB-H tumors. BICR, blinded independent central review; bTMB-H, high blood tumor mutational burden; (m)OS, (median) overall survival; (m)PFS, (median) progression-free survival; tTMB-H, high tissue tumor mutational burden.

When increasing cut-offs were used to determine bTMB-H, the likelihood of the patient also having tTMB-H increased (online supplemental figure 3). The proportion of patients with bTMB-H having dual bTMB-H/tTMB-H increased from 47.2% at a bTMB cut-off of ≥10 mut/Mb to 59.0% with a bTMB cut-off of ≥13 mut/Mb, 70.5% with a bTMB cut-off of ≥16 mut/Mb, and 81.0% with a bTMB cut-off of ≥20 mut/Mb. Across both treatment arms, there was a trend toward increased ORR with increasing cut-off for tTMB or bTMB (≥13 mut/Mb, ≥16 mut/Mb, ≥20 mut/Mb), although patient numbers at higher cutoffs are small (online supplemental table 4).

ORR interpretations in patients grouped by PD-L1 expression (≥1% or <1%) or MSI status (MSI-H or non-MSI-H) were not conclusive because of small patient numbers (online supplemental table 4). Similarly, although responses were observed across tumor types, sample sizes were too small to derive meaningful conclusions by tumor type, and the study was not designed for such assessment.

Safety

In patients with tTMB-H and those with bTMB-H, the safety profiles of nivolumab+ipilimumab and nivolumab monotherapy were consistent with prior reports and were manageable. In the nivolumab+ipilimumab arm, any grade (grade 3 or 4) treatment-related AEs (TRAEs) were reported in 83.0% (28.7%) of patients with tTMB-H and in 78.3% (37.3%) of patients with bTMB-H (table 3). In the monotherapy arm, any grade (grade 3 or 4) TRAEs were reported in 54.0% (8.0%) of patients with tTMB H and in 59.6% (2.1%) of patients with bTMB-H. In the nivolumab+ipilimumab arm, any grade (grade 3 or 4) serious AEs (SAEs) occurred in 47.9% (30.9%) of patients with tTMB H and in 61.4% (38.6%) of patients with bTMB-H. In the nivolumab monotherapy arm, any grade (grade 3 or 4) SAEs occurred in 32.0% (20.0%) of patients with tTMB H and in 34.0% (21.3%) of patients with bTMB-H. Across the study, there was one treatment-related death: hyperglycemia in a patient with tTMB-H and bTMB-H treated with nivolumab+ipilimumab.

Table 3. Summary of safety and immune-mediated AEs in the safety analysis population*.

| n (%) | NIVO+IPI (n=135) | NIVO (n=76) | ||||||||||

| tTMB-H (n=94) | bTMB-H (n=83) | tTMB-H (n=50) | bTMB-H (n=47) | |||||||||

| Any grade | Grade 3/4 | Grade 5 | Any grade | Grade 3/4 | Grade 5 | Any grade | Grade 3/4 | Grade 5 | Any grade | Grade 3/4 | Grade 5 | |

| All causality | 93 (98.9) | 50 (53.2) | 10 (10.6) | 82 (98.8) | 47 (56.6) | 14 (16.9) | 50 (100.0) | 19 (38.0) | 6 (12.0) | 45 (95.7) | 19 (40.4) | 4 (8.5) |

| Drug-related AE | ||||||||||||

| 30 days | 78 (83.0) | 27 (28.7) | – | 64 (77.1) | 28 (33.7) | – | 27 (54.0) | 4 (8.0) | – | 28 (59.6) | 1 (2.1) | – |

| 100 days | 78 (83.0) | 27 (28.7) | – | 65 (78.3) | 31 (37.3) | – | 27 (54.0) | 4 (8.0) | – | 28 (59.6) | 1 (2.1) | – |

| SAE | 45 (47.9) | 29 (30.9) | 10 (10.6) | 51 (61.4) | 32 (38.6) | 14 (16.9) | 16 (32.0) | 10 (20.0) | 6 (12.0) | 16 (34.0) | 10 (21.3) | 4 (8.5) |

| AE leading to discontinuation | 25 (26.6) | 19 (20.2) | 3 (3.2) | 32 (38.6) | 23 (27.7) | 4 (4.8) | 6 (12.0) | 4 (8.0) | 1 (2.0) | 4 (8.5) | 3 (6.4) | 0 |

| Non-endocrine imAE | ||||||||||||

| Pneumonitis | 1 (1.1) | – | – | – | – | – | 1 (2.0) | – | – | – | – | – |

| Diarrhea/colitis | 7 (7.4) | 4 (4.3) | – | 5 (6.0) | 4 (4.8) | – | 4 (8.0) | – | – | 1 (2.1) | – | – |

| Hepatitis | 6 (6.4) | 4 (4.3) | – | 5 (6.0) | 2 (2.4) | – | 1 (2.0) | 1 (2.0) | – | – | – | – |

| Nephritis and renal dysfunction | 1 (1.1) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Rash | 10 (10.6) | 2 (2.1) | – | 7 (8.4) | 1 (1.2) | – | 3 (6.0) | – | – | 1 (2.1) | – | – |

| Hypersensitivity | 2 (2.1) | 1 (1.1) | – | 1 (1.2) | – | – | 1 (2.0) | – | – | 2 (4.3) | – | – |

| Endocrine imAE | ||||||||||||

| Adrenal insufficiency | 4 (4.3) | – | – | 6 (7.2) | 3 (3.6) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Hypothyroidism | 13 (13.8) | – | – | 9 (10.8) | 1 (1.2) | – | 8 (16.0) | – | – | 8 (17.0) | – | – |

| Thyroiditis | 2 (2.1) | – | – | 3 (3.6) | 1 (1.2) | – | 1 (2.0) | – | – | 1 (2.1) | – | – |

| Diabetes mellitus | – | – | † | – | – | † | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Hyperthyroidism | 10 (10.6) | 1 (1.1) | – | 8 (9.6) | 2 (2.4) | – | 1 (2.0) | – | – | 1 (2.1) | – | – |

| Hypophysitis | 2 (2.1) | 1 (1.1) | – | 3 (3.6) | 2 (2.4) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

The safety analysis population comprises the 211 patients who received at least one dose of study drug; the tTMB-H and bTMB-H populations overlap. One who was in both the tTMB-H and bTMB-H cohorts was hospitalized due to Grade 4 hyperglycemia on Study Day 24 after initiation of nivolumab ( mg) and ipilimumab ( mg) combination therapy. The subsequently died of hyperglycemia. AE, adverse event; bTMB-H, high blood tissue mutational burden; imAE, immune-mediated AE; IPI, ipilimumab; NIVO, nivolumab; SAE, serious adverse event; tTMB-H, high tissue

One patient who was in both the tTMB-H and bTMB-H cohorts was hospitalized due to Grade 4 hyperglycemia on Study Day 24 after initiation of nivolumab (240 mg) and ipilimumab (122 mg) combination therapy. The patient subsequently died of hyperglycemia.

AEadverse eventbTMB-Hhigh blood tissue mutational burdenimAEimmune-mediated AEIPIipilimumabNIVOnivolumabSAEserious AEtTMB-Hhigh tissue tumor mutational burden

Discussion

This study evaluated the efficacy and safety of nivolumab with or without ipilimumab in patients with advanced metastatic solid tumors in the salvage setting with tTMB-H and/or bTMB-H. Enrolled patients had solid tumors across ~40 different disease types, had received a median of two prior lines of therapy, and were selected for TMB-H. The study met its primary endpoint, with the lower bound of the 95% CI for ORR being >10% in both the tTMB-H and bTMB-H populations treated with nivolumab+ipilimumab. The finding that tumors with a high mutational burden may be more immunogenic than tumors with comparatively low mutational burden is supported by the increased ORRs seen in both the combination and monotherapy arms when increased tTMB/bTMB cut-offs were used.

The approval of pembrolizumab for the treatment of patients with tTMB-H solid tumors was based on a retrospective, exploratory analysis of data from the multicenter, single-arm KEYNOTE-158 trial in patients with previously treated solid tumors. The analysis showed ORRs of 29% (95% CI 21% to 39%) in patients with tTMB-H and 6% (95% CI 5% to 8%) in patients with non-tTMB-H.6 The ORRs in the current study were similar for nivolumab monotherapy in patients with solid tumors and tTMB-H (29.8%; 95% CI 17.3% to 44.9%), but numerically higher in the nivolumab+ipilimumab arm (38.6%; 95% CI 28.4% to 49.6%). In both, the tTMB-H and bTMB-H patient groups, the lower bound of the 95% CI for the ORR in the combination therapy arm overlapped with the point estimate for the monotherapy arm. However, the ORRs were numerically higher in the nivolumab+ipilimumab arm versus the nivolumab monotherapy arm (the study was not powered for comparisons between treatment arms). The finding that patients with tTMB-H may benefit from nivolumab+ipilimumab is supported by previously published results from clinical studies in NSCLC, small cell lung cancer, melanoma, and urothelial carcinoma.911 13 22,24

Early and durable responses to treatment with nivolumab+ipilimumab were seen in patients with tTMB-H or bTMB-H. Although the study was not designed to compare the clinical utility of tTMB with bTMB, treatment responses in this study appeared to be driven by tTMB status (online supplemental table 4). As such, determining TMB status by tissue sampling may be preferred. However, the association between bTMB and tTMB status improved when cut-offs to determine bTMB were increased from ≥10 mut/Mb to ≥20 mut/Mb. This suggests that bTMB may serve as a meaningful surrogate in cases where tTMB may not be evaluable. In a separate analysis of the overall samples taken during screening for the current study (June 2021 database lock), there was a correlation between tTMB and bTMB (Spearman’s rank correlation, r=0.48), with a higher correlation (r=0.54; p<0.0001) seen in samples with maximum somatic allele frequency ≥1%.3

ctDNA detection and subsequent bTMB evaluation can depend on the degree of tumor shedding, which differs across tumor types and disease stages.25 Tumor DNA shedding is highly variable, with the fraction of plasma ctDNA in total cell-free DNA (cfDNA) ranging from <0.01% to the majority.25 26 Although the low amount of ctDNA present in plasma samples may decrease the sensitivity of plasma-based assays, the advantages of using blood samples over tissue samples include deferral of invasive biopsies, determination of a more current genomic profile than that seen with archival tissue samples, more prompt retrieval of results, and determination of the intratumoral and intertumoral heterogeneity of a tumor.26

As expected, treatment with nivolumab+ipilimumab was associated with a higher rate of AEs compared with nivolumab monotherapy, but the safety profile of nivolumab+ipilimumab was manageable and there were no new safety signals. The dosages of nivolumab used in this study, that is, flat-dose nivolumab 240 mg every 2 weeks and flat-dose NIVO 480 mg every 4 weeks, have been evaluated across multiple studies and have been shown to have comparable benefit/risk profiles.27,30

Although the study suggested treatment benefit with immunotherapy for patients with TMB-H, it had several limitations. The prevalence of TMB-H across tumor types is low (~12% to 15%),31,33 which limits the feasibility of a large, randomized trial by tumor type. Furthermore, as this was a pan-tumor study, the number of patients with specific tumor types was not large enough to enable analyses specific to disease subtypes. Another possible limitation of the study is that patients who progressed on nivolumab monotherapy could cross over to the combination-treatment arm following disease progression. In both, the tTMB-H and bTMB-H patient groups, more nivolumab monotherapy recipients received subsequent therapy, including crossover to combination therapy, than did nivolumab+ipilimumab recipients. This may be one factor that contributed to the longer OS seen with nivolumab monotherapy than with nivolumab+ipilimumab in patients with bTMB-H. However, in the tTMB-H group, despite more patients in the monotherapy arm receiving subsequent therapy than patients in the combination therapy arm, median OS was numerically longer with combination therapy, further supporting the greater clinical benefit observed with nivolumab+ipilimumab in the tTMB-H population compared with the bTMB-H population. The study was not powered for PFS or OS analysis, thus limiting interpretation of these results. A final limitation is the lack of a cohort of patients with TMB-L, which would have allowed direct comparison of efficacy of nivolumab+ipilimumab in patients with TMB-H vs TMB-L.

In conclusion, nivolumab+ipilimumab demonstrated clinical efficacy with a manageable safety profile in patients with advanced or metastatic tTMB-H and/or bTMB-H solid tumors that were refractory to standard therapies, with higher ORR observed in patients with tTMB-H tumors. bTMB continues to be evaluated as a biomarker, both analytically and clinically. Analytical factors, such as tumor fraction (proportion of ctDNA relative to total cfDNA), influence the overall bTMB score and need to be further defined before the clinical implications of these results can be fully understood. Patients with malignancies who have experienced disease progression on all available therapies have limited treatment options, representing a high unmet medical need. The results of this study suggest that nivolumab+ipilimumab is a potential treatment option for some patients with TMB-H, as determined by tissue biopsy, or by blood sample when tissue biopsy is unavailable, who have no available treatment options, and should be explored further.

supplementary material

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the patients and families who made this study possible and the clinical teams who participated. We also thank Bristol Myers Squibb (Princeton, NJ) and Ono Pharmaceutical Company Ltd. (Osaka, Japan). DSPT is supported by the Singapore National Medical Research Council (NMRC) Clinician Scientist Award (CSASI21jun-003). Medical writing support and editorial assistance were provided by Keri Wellington, PhD, and Agata Shodeke, PhD, of Spark Medica Inc, according to Good Publication Practice guidelines, funded by Bristol Myers Squibb.

Footnotes

Funding: The study was supported by Bristol Myers Squibb.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not applicable.

Ethics approval: This study involves human participants and this was an international, clinical trial with 60 study sites worldwide. Listing every review board or ethics committee that approved the study at each location would, therefore, not be feasible. This trial was approved by the institutional review board or ethics committee at each site and was conducted according to Good Clinical Practice guidelines, defined by the International Conference on Harmonisation. The study was conducted in compliance with the protocol. The protocol and any amendments and the participant informed consent received approval/favorable opinion by the Institutional Review Board/Independent Ethics Committee (IRB/IEC), and regulatory authorities according to applicable local regulations prior to initiation of the study. Study locations can be found listed on ClinicalTrials. gov (https://classic.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/study/NCT03668119). All the patients provided written informed consent that was based on the Declaration of Helsinki principles. Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

Data availability free text: Bristol Myers Squibb will honor legitimate requests for clinical trial data from qualified researchers with a clearly defined scientific objective. Data sharing requests will be considered for phases II–IV interventional clinical trials that completed on or after January 1, 2008. In addition, primary results must have been published in peer-reviewed journals and the medicines or indications approved in the USA, EU, and other designated markets. Sharing is also subject to protection of patient privacy and respect for the patient’s informed consent. Data considered for sharing may include non-identifiable patient-level and study-level clinical trial data, full clinical study reports, and protocols. Requests to access clinical trial data may be submitted using the enquiry form at https://vivli.org/ourmember/bristol-myers-squibb/.

Contributor Information

Michael Schenker, Email: mike_schenker@yahoo.com.

Mauricio Burotto, Email: mauricioburotto@gmail.com.

Martin Richardet, Email: martinonco@hotmail.com.

Tudor-Eliade Ciuleanu, Email: tudor_ciuleanu@hotmail.com.

Anthony Gonçalves, Email: goncalvesa@ipc.unicancer.fr.

Neeltje Steeghs, Email: n.steeghs@nki.nl.

Patrick Schoffski, Email: patrick.schoffski@uzleuven.be.

Paolo A Ascierto, Email: paolo.ascierto@gmail.com.

Michele Maio, Email: mmaiocro@gmail.com.

Iwona Lugowska, Email: iwona.lugowska@pib-nio.pl.

Lorena Lupinacci, Email: lorena.lupinacci@gmail.com.

Alexandra Leary, Email: alexandra.leary@gustaveroussy.fr.

Jean-Pierre Delord, Email: delord.jean-pierre@iuct-oncopole.fr.

Julieta Grasselli, Email: julieta.grasselli@gmail.com.

David S P Tan, Email: david_sp_tan@nuhs.edu.sg.

Jennifer Friedmann, Email: jennifer.friedmann.ccomtl@ssss.gouv.qc.ca.

Jacqueline Vuky, Email: vukyja@ohsu.edu.

Marina Tschaika, Email: Marina.Tschaika@bms.com.

Somasekhar Konduru, Email: Somasekhar.Konduru@bms.com.

Sai Vikram Vemula, Email: SaiVikram.Vemula@bms.com.

Ruta Slepetis, Email: rutajslep@gmail.com.

Georgia Kollia, Email: georgia.kollia@bms.com.

Misena Pacius, Email: misena.pacius@bms.com.

Quyen Duong, Email: quyen.duong@bms.com.

Ning Huang, Email: ning.huang@bms.com.

Parul Doshi, Email: parul.doshi@bms.com.

Jonathan Baden, Email: jonathan.baden@bms.com.

Massimo Di Nicola, Email: massimo.dinicola@istitutotumori.mi.it.

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request. Data may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available.

References

- 1.Schumacher TN, Schreiber RD. Neoantigens in cancer immunotherapy. Science. 2015;348:69–74. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa4971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kandoth C, McLellan MD, Vandin F, et al. Mutational landscape and significance across 12 major cancer types. Nature. 2013;502:333–9. doi: 10.1038/nature12634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.He J, Kalinava N, Doshi P, et al. Evaluation of tissue- and plasma-derived tumor mutational burden (TMB) and genomic alterations of interest in CheckMate 848, a study of nivolumab combined with ipilimumab and nivolumab alone in patients with advanced or metastatic solid tumors with high TMB. J Immunother Cancer. 2023;11:e007339. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2023-007339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cao J, Yang X, Chen S, et al. The predictive efficacy of tumor mutation burden in immunotherapy across multiple cancer types: a meta-analysis and bioinformatics analysis. Transl Oncol. 2022;20:101375. doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2022.101375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Snyder A, Makarov V, Merghoub T, et al. Genetic basis for clinical response to CTLA-4 blockade in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:2189–99. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1406498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marabelle A, Fakih M, Lopez J, et al. Association of tumour mutational burden with outcomes in patients with advanced solid tumours treated with pembrolizumab: prospective biomarker analysis of the multicohort, open-label, phase 2 KEYNOTE-158 study. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:1353–65. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30445-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Valero C, Lee M, Hoen D, et al. The association between tumor mutational burden and prognosis is dependent on treatment context. Nat Genet. 2021;53:11–5. doi: 10.1038/s41588-020-00752-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Samstein RM, Lee C-H, Shoushtari AN, et al. Tumor mutational load predicts survival after immunotherapy across multiple cancer types. Nat Genet. 2019;51:202–6. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0312-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ready N, Hellmann MD, Awad MM, et al. First-line nivolumab plus Ipilimumab in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (CheckMate 568): outcomes by programmed death ligand 1 and tumor mutational burden as biomarkers. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:992–1000. doi: 10.1200/JCO.18.01042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carbone DP, Reck M, Paz-Ares L, et al. First-line nivolumab in stage IV or recurrent non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:2415–26. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1613493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hellmann MD, Ciuleanu T-E, Pluzanski A, et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab in lung cancer with a high tumor mutational burden. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2093–104. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1801946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Friedman CF, Hainsworth JD, Kurzrock R, et al. Atezolizumab treatment of tumors with high tumor mutational burden from MyPathway, a multicenter, open-label, phase IIa multiple basket study. Cancer Discov. 2022;12:654–69. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-21-0450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hellmann MD, Callahan MK, Awad MM, et al. Tumor mutational burden and efficacy of nivolumab monotherapy and in combination with ipilimumab in small-cell lung cancer. Cancer Cell. 2018;33:853–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2018.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marcus L, Fashoyin-Aje LA, Donoghue M, et al. FDA approval summary: pembrolizumab for the treatment of tumor mutational burden-high solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2021;27:4685–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-21-0327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fenizia F, Pasquale R, Roma C, et al. Measuring tumor mutation burden in non-small cell lung cancer: tissue versus liquid biopsy. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2018;7:668–77. doi: 10.21037/tlcr.2018.09.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ossandon MR, Agrawal L, Bernhard EJ, et al. Circulating tumor DNA assays in clinical cancer research. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018;110:929–34. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djy105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim ES, Velcheti V, Mekhail T, et al. Blood-based tumor mutational burden as a biomarker for atezolizumab in non-small cell lung cancer: the phase 2 B-F1Rst trial. Nat Med. 2022;28:939–45. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01754-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peters S, Dziadziuszko R, Morabito A, et al. Atezolizumab versus chemotherapy in advanced or metastatic NSCLC with high blood-based tumor mutational burden: primary analysis of BFAST cohort C randomized phase 3 trial. Nat Med. 2022;28:1831–9. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01933-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gandara DR, Paul SM, Kowanetz M, et al. Blood-based tumor mutational burden as a predictor of clinical benefit in non-small-cell lung cancer patients treated with atezolizumab. Nat Med. 2018;24:1441–8. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0134-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1) Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leao DJ, Craig PG, Godoy LF, et al. Response assessment in neuro-oncology criteria for gliomas: practical approach using conventional and advanced techniques. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2020;41:10–20. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A6358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hodi FS, Wolchok JD, Schadendorf D, et al. TMB and inflammatory gene expression associated with clinical outcomes following immunotherapy in advanced melanoma. Cancer Immunol Res. 2021;9:1202–13. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-20-0983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chang H, Sasson A, Srinivasan S, et al. Bioinformatic methods and bridging of assay results for reliable tumor mutational burden assessment in non-small cell lung cancer. Mol Diagn Ther. 2019;23:507–20. doi: 10.1007/s40291-019-00408-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Galsky MD, Saci A, Szabo PM, et al. Nivolumab in patients with advanced platinum-resistant urothelial carcinoma: efficacy, safety, and biomarker analyses with extended follow-up from CheckMate 275. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26:5120–8. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-4162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bettegowda C, Sausen M, Leary RJ, et al. Detection of circulating tumor DNA in early- and late-stage human malignancies. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:224ra24. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheng ML, Pectasides E, Hanna GJ, et al. Circulating tumor DNA in advanced solid tumors: clinical relevance and future directions. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:176–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.21650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bi Y, Liu J, Furmanski B, et al. Model-informed drug development approach supporting approval of the 4-week (Q4W) dosing schedule for nivolumab (Opdivo) across multiple indications: a regulatory perspective. Ann Oncol. 2019;30:644–51. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Long GV, Tykodi SS, Schneider JG, et al. Assessment of nivolumab exposure and clinical safety of 480 mg every 4 weeks flat-dosing schedule in patients with cancer. Ann Oncol. 2018;29:2208–13. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhao X, Shen J, Ivaturi V, et al. Model-based evaluation of the efficacy and safety of nivolumab once every 4 weeks across multiple tumor types. Ann Oncol. 2020;31:302–9. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2019.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Samlowski W, Robert NJ, Chen L, et al. Real-world nivolumab dosing patterns and safety outcomes in patients receiving adjuvant therapy for melanoma. Cancer Med. 2023;12:2378–88. doi: 10.1002/cam4.5061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang S, Fang Y, Jiang N, et al. Comprehensive genomic profiling of rare tumors in China: routes to immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 2021;12:631483. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.631483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kang Y-J, O’Haire S, Franchini F, et al. A scoping review and meta-analysis on the prevalence of pan-tumour biomarkers (dMMR, MSI, high TMB) in different solid tumours. Sci Rep. 2022;12:20495. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-23319-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shao C, Li G, Huang L, et al. Prevalence of high tumor mutational burden and association with survival in patients with less common solid tumors. JAMA Netw Open . 2020;3:e2025109. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.25109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request. Data may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available.