Abstract

Travelers to areas with Zika virus transmission are at risk of infection and of transmitting the virus after returning home. While protective behaviors during and after travel can reduce these risks, information about traveler practices or underlying views is limited. We examined these issues using data from the first representative poll of travelers from US states to Zika-affected areas, including US territories and Miami, Florida, conducted December 1 to 23, 2016. We analyzed results among all travelers (n = 1,285) and 2 subgroups at risk for pregnancy-related complications: (1) travelers in households where someone was pregnant or considering pregnancy (n = 72), and (2) other travelers of reproductive age (n = 631). We also examined results among those with different levels of awareness and knowledge about Zika virus. Results show that in households where someone was pregnant or considering pregnancy, awareness of Zika in the destination, concern about infection, and adoption of protective behaviors was relatively high. That said, sizable shares of travelers as a whole did not know information about asymptomatic and sexual transmission or post-travel behaviors. Further, concern about getting infected during travel was low among travelers as a whole, including other travelers of reproductive age. Few travelers consistently adopted protective behaviors during or after travel. Even among travelers who were aware of Zika in their destination and knew how to protect themselves, adoption of protective behaviors was only slightly higher. Findings from this poll suggest communications may be more effective if tailored to different levels of true and perceived risk. To address gaps in knowledge about transmission and post-travel protective behaviors, messaging should include facts and acknowledge the complexities of novel information and social context. Consideration should also be given to emphasizing other benefits of Zika protective behaviors or prioritizing behaviors that are most feasible.

Keywords: Infectious diseases, Risk communication, Travel, Zika

People who travel to areas with active Zika virus transmission are at risk of infection and of contributing to the spread of Zika virus when they return home, either through sexual transmission or by serving as a host in areas where mosquitoes capable of transmitting the virus live. From 2015 to 2018, more than 5,400 travel-associated cases of symptomatic Zika virus disease were reported in the continental United States, with 231 cases reported due to local mosquito-borne transmission in Miami-Dade County, Florida, and Brownsville, Texas.1–4 The emergence of Zika virus among travelers and through local transmission in US states poses a significant threat to public health, particularly in light of its potential negative effects on pregnancies and developing fetuses. While there has been no local mosquito-borne Zika virus transmission reported in the continental United States since 2017, Zika remains a risk in many places around the world, including popular tourist destinations.5

To reduce the risks of infection and subsequent transmission, there are protective behaviors travelers can adopt during their trip and after returning home, including mosquito-bite prevention (eg, wearing insect repellent, wearing long-sleeved shirts and pants) and sexual transmission prevention (eg, using condoms or abstaining from sex),6,7 but these may be difficult to motivate. First, recommended behaviors may be unappealing. Wearing long sleeves and pants in hot climates, such as those of many areas affected by Zika virus, may be uncomfortable, and the difficulties of motivating condom use have been shown with other sexually transmitted infections.8 Second, because the negative health effects of Zika virus disease are largely associated with pregnancy, it may be difficult to motivate adoption of protective behaviors among those who are at no personal risk of harm from pregnancy-specific sequelae—such as those who cannot get pregnant. It may also be difficult to motivate those who perceive they are at low personal risk because they are not pregnant or actively considering pregnancy.9

Given the challenges of motivating behavior adoption to protect against Zika infection, it is all the more important to reach travelers with messages that are based on data about their views, including knowledge of the disease and transmission, risk perceptions, and perceived barriers.10 Yet, data about the views of travelers to Zika-affected areas during the relevant timeframe is quite limited, in part because this is a difficult population to survey with representative methodologies. As far as we are aware, existing studies have largely approached this challenge by relying on very small sample sizes of travelers,11,12 by focusing on convenience samples of populations who may be likely to travel,13 or by surveying similar populations that are easier to recruit with representative methodologies. Examples of such populations include people who plan to travel to Zika-affected areas but have not actually done so14,15 and people who have traveled broadly outside the United States but not necessarily to Zika-affected areas specifically.16,17 Only 1 study that we are aware of used a representative sample of adult travelers to Zika-affected areas, and this was focused only on travelers to countries outside the United States and did not include Zika-affected US territories or states.18

Drawing from these studies, there is evidence that these subsets or related populations show relatively low behavioral response to Zika virus and low levels of awareness and critical knowledge.18 For example, awareness of Zika virus transmission in the areas where they traveled was low among pregnant women who were sent for Zika virus testing in New York.12 Further, having traveled to Zika-endemic regions was not associated with increased knowledge about Zika virus transmission among a convenience sample of New Yorkers.16 Among those who plan to travel, there are key gaps in knowledge about such topics as sexual transmission and limited concern about the risks of infection during future travel.14,15

These worrisome findings reinforce the need for robust evidence about actual experiences from among a representative sample of travelers to Zika-affected areas in order to guide the range of traveler-specific communications. It is essential to ask questions about awareness, knowledge, behaviors, and reasoning among a range of travelers in order to understand factors that may contribute to their behavior response and provide insights into the possible differences among key subgroups, including those with different true and perceived risks.

In this study, we aim to fill this gap in understanding by using data from the first representative study of adults who traveled from US states to Zika-affected areas, including other countries, territories, and Miami, Florida, during the peak of transmission. First, we examine awareness of the virus, knowledge about transmission and prevention, concern, and key behaviors during and after travel among all travelers in the poll. Second, we examine these issues among 2 subgroups at risk for pregnancy-related complications from Zika: travelers who were in households where someone was pregnant or considering getting pregnant at the time of their trip and travelers who were not in those households but of reproductive age. Third, to understand possible barriers to action beyond knowledge, we examine self-described reasons for not adopting protective behaviors during travel among those who knew of Zika cases in their destination and had basic knowledge of protective behaviors.

Methods

Researchers at Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health (HSPH, Boston, MA) designed and analyzed a poll conducted December 1 to 23, 2016, among a representative sample of 1,285 travelers to areas with active Zika virus transmission (Zika-affected areas). “Travelers” were defined as adults aged 18 and older who lived in a US state and (1) had visited another country or territory (including Puerto Rico or the US Virgin Islands) with a travel advisory issued by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) due to reported local mosquito-borne transmission of Zika virus through March 1, 2016, or (2) had visited Miami, FL, since the issuance of a travel advisory on August 1, 2016 (not including Florida residents) (see Appendix at https://www.liebertpub.com/suppl/doi/10.1089/hs.2019.0008). SSRS (Glen Mills, PA) oversaw field operations, including pretesting of the questionnaire, as well as data management and statistical analyses.

The sample was drawn using an online methodology designed to address challenges of reaching this specialized population quickly while still grounding the approach in probability sampling. First, a core sample was drawn randomly from a probability-based, online panel: GfK Knowledge Panel (New York, NY). The GfK panel is nationally representative and covers both online and offline populations in the United States, because GfK provides internet access for households that do not have computer or internet access prior to joining.19 Second, to add more probability-based sample, an additional nationally representative sample was drawn from the SSRS probability online panel. Third, to enhance the sampling by reaching more speakers of languages other than English or Spanish (consistent with the profile of countries/regions affected by Zika virus) and to boost overall sample size, supplemental samples were drawn from 2 non-probability online sample sources: Critical Mix (Westport, CT) and Paradigm (Port Washington, NY).

For all samples, participants were invited through online invitations and were screened using information about their travel without knowing the specific purpose of the study, in order to reduce the risk of response bias. Qualified respondents were offered incentives for completing the poll that ranged from $1 to $20 in direct payment or equivalents. Responses were submitted to an extensive set of respondent-level validity checks before being included in final analyses (details of checks in Appendix). The completion rate for the probability panels was 54% for GfK and 6% for SSRS. As is standard, response rates are substantially lower (<5%) on online probability panels once accounting for participation in the panel as a whole.20–22

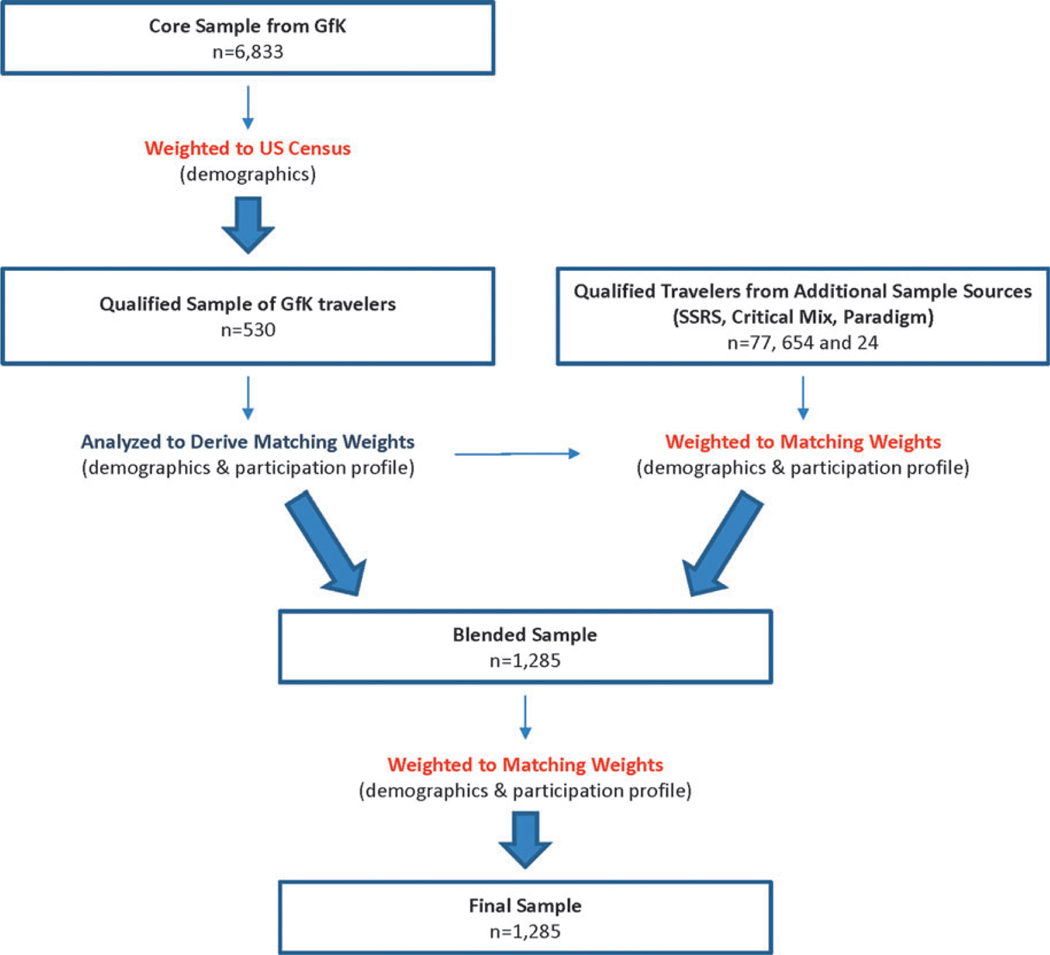

To build on best practices in reducing the risk of non-response bias in surveys among the public using online panels, we weighted the data in stages beginning with the core sample from GfK (Figure 1).14,15,17 This core sample (including those who did and did not qualify as travelers) was weighted to the US Census with respect to key demographics, including gender, age, race/ethnicity, census region, education, and household income.23 Subsequent analysis focused on the subset of qualified travelers.

Figure 1.

Samples and Weighting Process

To merge all samples of travelers, we then applied 2 sets of “matching” weights (derived from the qualified travelers) to the non-GfK samples. Matching weights included the traveler-specific prevalence of key demographics (ie, gender, age, race/ethnicity, census region, education, and household income). Matching weights also included traveler-specific prevalence of attitudinal and behavioral parameters associated with online survey participation developed by GfK (TV watching habits, internet use, frequency of political expression, and willingness to try new products).19 The weighted samples from SSRS, Critical Mix, and Paradigm were merged with the GfK data, and this blended sample was weighted again to these same parameters in order to achieve the final sample. (Details of weighting parameter variables can be found in the Appendix.)

To assess the results of these weighting procedures with respect to overall validity and reasonableness, the final sample was compared to an independent random sample of respondents qualifying as travelers and recruited through a traditional random digit dial (RDD) approach concurrently with our online poll. Results suggest our data is in line with this source with respect to demographics and areas traveled (details of comparisons in Appendix).

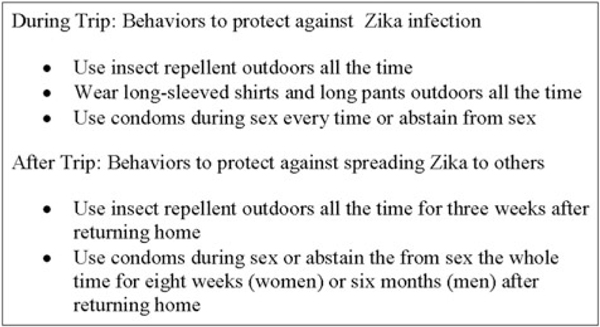

The questionnaire included approximately 50 questions. It included questions about knowledge of Zika symptoms, transmission, and complications; awareness of Zika cases in the traveler’s destination; concern about Zika virus; awareness of information about protective behaviors during and after travel; and adoption of these behaviors during and after travel (question wording shown in tables). Questions also asked about key behaviors recommended by CDC in 2016 to protect against Zika infection during travel and transmitting it to others after travel (Figure 2).6,7 Among those who adopted a given behavior, questions asked whether avoiding infection with Zika virus was a reason for doing so; among those who did not adopt a given behavior, respondents were asked to specify reasons for not doing so. The questionnaire was informed by studies concerning travelers’ views of health risks,24–26 Zika virus–related opinion polls among the general public,27–29 and studies of public response to other disease outbreaks.30–32 The questionnaire was translated into Spanish, Portuguese, and Haitian-Creole. It was tested with a small number of participants (n = 66) to assess logic and flow.

Figure 2.

CDC-Recommended Behaviors in 2016 Asked About in Poll

We first analyzed univariate results among the full sample. We then examined results among 2 subgroups at risk for pregnancy-related complications. The first is defined as all respondents who indicated “Yes,” a member of their household was pregnant or considering getting pregnant at the time of the trip. For ease, this group is referred to as “household pregnancy” (“HP”) travelers. The comparison group is all those who were not in households where someone was pregnant or considering getting pregnant at the time of the trip (“non-HP”).

The second pregnancy-related complications risk group is defined as respondents who were of reproductive age but did not say a member of their household was pregnant or considering pregnancy at the time of the trip. Reproductive age was considered to be 18 to 44 years of age for women and 18 to 54 years for men, as these ages reflect the sex-specific age range of parents for 99% of births in the United States.33 For ease, this second group is referred to as “reproductive age” (“RA”) travelers. The comparison group (“non-RA”) is all those who were not in the reproductive age range and also did not say a member of their household was pregnant or considering getting pregnant at the time of the trip.

Finally, to better understand barriers to behaviors beyond basic factual knowledge, we examined non-adoption of Zika protective behaviors (eg, failure to use insect repellent, wear long-sleeved shirts and long pants, or consistently use condoms during sex) among those who were aware of Zika cases in their destination and knew the relevant Zika protective behavior (termed “knowledgeable travelers”). We compared each behavior among the group of knowledgeable travelers and those without the identified knowledge. Among knowledgeable travelers who did not adopt each behavior, we examined their reported reasons for not doing so.

Statistical Analysis

Although approximately half of the poll’s sample originated from non-probability samples, the mixed-sample design facilitated weighting corrections (see above) that allowed the non-probability component to reflect the same distributions as the probability component. In view of this, the sample as a whole is treated as a probability sample for the purposes of statistical difference tests.34,35 Comparisons between subgroups were made using tests of proportion that account for the design effect of weighted data. Results with a p-value of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistically significant differences are shown in the tables, though only significant differences of at least 10 percentage points were considered meaningful for communications strategy planning and are thus described in the text.36–39 All statistics were calculated using Mentor 3.0 (Survox Inc, San Francisco, CA). The study was approved under an “exempt” determination by HSPH’s Office of Human Research Administration.

Results

Demographics

Proportions of male and female travelers were equal (50% male and 50% women) (Table 1). Approximately half of travelers were white non-Hispanic/Latino (55%), and approximately a quarter were Hispanic/Latino (27%), with smaller fractions belonging to other racial/ethnic groups. Nearly half (46%) had an annual income of $100,000 or more, and only 10% had an income less than $25,000. Approximately 4 in 10 (42%) had at least a college degree, and about a quarter (28%) had a high school education or less. Few were under 25 years old (11%) or over 65 (14%); the majority were split between ages 25 to 44 (42%) and 45 to 64 (33%). A small share (5%) were HP travelers, while more than half (56%) were RA travelers.

Table 1.

Respondent Demographics: Travelers from US States to Zika-Affected Areas

| Total (%) (n =1,285) | |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 50 |

| Female | 50 |

| Age | |

| 18–24 | 11 |

| 25–44 | 42 |

| 45–64 | 33 |

| 65+ | 14 |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White non-Hispanic/Latino | 55 |

| Black non-Hispanic/Latino | 9 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 27 |

| Other non-Hispanic/Latino | 8 |

| Income | |

| Less than $25K | 10 |

| $25–49.9K | 15 |

| $50–74.9K | 15 |

| $75–99.9K | 14 |

| $100K or more | 46 |

| Education | |

| High school or less | 28 |

| Some college | 30 |

| College or more | 42 |

| Household pregnancy (HP) status a | |

| HP | 5 |

| Non-HP | 95 |

| Reproductive age (RA) status b | |

| RA | 56 |

| Non-RA | 39 |

Household pregnancy (HP): Travelers who responded “Yes” to the question, “As far as you know, was anyone in your household pregnant or considering getting pregnant at the time of your trip to [destination]?” Non-HP: Travelers who responded “No,” “Don’t know,” or refused the question.

Reproductive age (RA): Female travelers 18–44 and male travelers 18-54 who responded “No,” “Don’t know,” or refused the question, “As far as you know, was anyone in your household pregnant or considering getting pregnant at the time of your trip to [destination]?” Non-RA: Female travelers 45+ and male travelers 55+ who responded “No,” “Don’t know,” or refused the question.

Note: Results shown are weighted. Responses of “don’t know”/refused <2% not shown.

Findings Among All Travelers

Knowledge of Zika symptoms, transmission, and complications:

A majority of travelers correctly identified key common symptoms of Zika, including fever (69%) and headache (52%), but less than half mentioned any other symptom (Table 2). Approximately a third (35%) said, incorrectly, that “coughing and sneezing” are common symptoms.

Table 2.

Knowledge of Zika Symptoms, Complications, Transmission, and Prevention Among Travelers from US States to Zika-Affected Areas

| If a person infected with Zika virus does get symptoms, what symptoms are most common? | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (%) (n = 1,285) | HPa (%) (n = 72) | Non-HPa (%) (n = 1,213) | RAb (%) (n = 631) | Non-RAb (%) (n = 582) | |

| Fever | 69 | 87c | 68 | 66 | 72 |

| Headache | 52 | 70c | 51 | 49 | 55 |

| Joint pain | 45 | 63c | 45 | 44 | 45 |

| Rash | 35 | 61c | 34 | 33 | 35 |

| Coughing and sneezing | 35 | 57c | 34 | 39c | 27 |

| Conjunctivitis or red/pink eyes | 22 | 62c | 20 | 24c | 15 |

| To the best of your knowledge, can a person get infected with Zika virus in each of the following ways? | |||||

| Total (%) (n = 1,285) | HPa (%) (n = 72) | Non-HPa (%) (n = 1,213) | RAb (%) (n = 631) | Non-RAb (%) (n = 582) | |

| Through mosquito bites | 90 | 87 | 90 | 86 | 95c |

| Through blood transfusions | 57 | 74c | 56 | 61c | 48 |

| Through vaginal or anal sex without a condom | 53 | 73c | 52 | 53 | 52 |

| Through oral sex without a condom or dental dam | 40 | 57c | 39 | 40 | 37 |

| Through contact with urine or saliva of someone who has Zika virus | 37 | 44 | 37 | 37 | 37 |

| By being sneezed or coughed on by someone who has Zika virus | 22 | 46c | 21 | 21 | 20 |

| Through which of the following ways, if any, can a person protect themselves from getting Zika virus? | |||||

| Total (%) (n = 1,285) | HPa (%) (n = 72) | Non-HPa (%) (n = 1,213) | RAb (%) (n = 631) | Non-RAb (%) (n = 582) | |

| Avoid travel to places where Zika virus is present | 86 | 81 | 86 | 82 | 93c |

| Use insect repellent when going outdoors | 85 | 87 | 85 | 80 | 92c |

| Wear long-sleeved shirts and long pants when going outdoors | 82 | 90 | 82 | 76 | 90c |

| Eliminate standing water from the house and yard | 81 | 82 | 81 | 73 | 92c |

| Use screens on open doors or windows, or use air conditioning | 78 | 71 | 79 | 72 | 87c |

| Consistently use condoms during sex | 58 | 70 | 58 | 57 | 59 |

| Wash hands | 50 | 61 | 50 | 47 | 53 |

| Avoid people who are coughing and sneezing | 40 | 62c | 39 | 39 | 40 |

| Avoid having sex | 37 | 54c | 36 | 38 | 34 |

| Wear a mask | 32 | 67c | 31 | 33 | 28 |

| Avoid unpasteurized meat and milk products | 25 | 51c | 23 | 26c | 19 |

| To the best of your knowledge, in order to spread Zika virus, does a person need to show symptoms or can a person spread Zika virus without showing symptoms? | |||||

| Total (%) (n = 1,285) | HPa (%) (n = 72) | Non-HPa (%) (n = 1,213) | RAb (%) (n = 631) | Non-RAb (%) (n = 582) | |

| Does not need to show symptoms | 65 | 50 | 66c | 62 | 71c |

| Incorrect/don’t know (NET) | 32 | 50c | 31 | 33 | 28 |

| Does need to show symptoms | 9 | 42c | 7 | 10c | 4 |

| Don’t know | 22 | 8 | 23c | 22 | 24 |

| Have never heard of Zika virus | 3 | 0 | 3 | 5c | 1 |

| How likely is it that someone who gets infected with Zika virus will have any symptoms? | |||||

| Total (%) (n = 1,285) | HPa (%) (n = 72) | Non-HPa (%) (n = 1,213) | RAb (%) (n = 631) | Non-RAb (%) (n = 582) | |

| Very likely | 18 | 47c | 17 | 17 | 16 |

| Somewhat likely | 41 | 32 | 41 | 37 | 46c |

| Not very likely | 19 | 13 | 19 | 20 | 18 |

| Not at all likely | 2 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Don’t know | 17 | 3 | 18c | 19 | 16 |

| Have never heard of Zika virus | 3 | 0 | 3 | 5c | 1 |

| To the best of your knowledge, have each of the following health complications been associated with Zika virus? | |||||

| Total (%) (n = 1,285) | HPa (%) (n = 72) | Non-HPa (%) (n = 1,213) | RAb (%) (n = 631) | Non-RAb (%) (n = 582) | |

| A birth defect in babies born to infected mothers, where the baby’s head is unusually small and can be a sign of incomplete brain development, also called “microcephaly” | 78 | 80 | 78 | 72 | 87c |

| Other kinds of brain damage or physical problems in babies born to infected mothers where the baby’s head is not unusually small | 48 | 64c | 47 | 44 | 51 |

| A form of paralysis, also called “Guillain-Barré Syndrome” | 23 | 54c | 22 | 22 | 22 |

| An infection of the lungs, also called pneumonia | 23 | 45c | 22 | 24c | 17 |

Household pregnancy (HP): Travelers who responded “Yes” to the question, “As far as you know, was anyone in your household pregnant or considering getting pregnant at the time of your trip to [destination]?” Non-HP: Travelers who responded “No,” “Don’t know,” or refused the question.

Reproductive age (RA): Female travelers 18–44 and male travelers 18–54 who responded “No,” “Don’t know,” or refused the question, “As far as you know, was anyone in your household pregnant or considering getting pregnant at the time of your trip to [destination]?” Non-RA: Female travelers 45+ and male travelers 55+ who responded “No,” “Don’t know,” or refused the question.

Percentage is statistically greater than comparison group.

Note: Results shown are weighted. Responses of refused <5% not shown.

Nine in 10 travelers (90%) identified mosquito bites as a mode of Zika virus transmission. Far fewer identified blood transfusions (57%), modes related to sexual contact (vaginal or anal sex without a condom [53%] or oral sex without a condom or dental dam [40%]). About a third (37%) noted, incorrectly, that someone could get infected from contact with urine or saliva (37%), and nearly a quarter (22%) said, again incorrectly, that a person can get infected by being sneezed or coughed on by someone who has Zika.

A large majority of travelers was aware of key Zika protective measures, including avoiding travel to Zika-affected areas (86%), and those pertaining to mosquito protection during travel to areas with Zika: using insect repellent (85%), wearing long-sleeved shirts and pants (82%), eliminating standing water (81%), or using screens or air conditioning (78%). Substantially fewer noted protective measures against sexual transmission: consistently using condoms during sex (58%) or avoiding having sex (37%). Further, sizable shares of travelers incorrectly believed that washing hands (50%), avoiding people who are coughing and sneezing (40%), wearing a mask (32%), or avoiding unpasteurized meat and milk products (25%) protect against Zika virus.

Most travelers (65%) said a person does not need to show symptoms in order to spread Zika virus, but a sizable share (32%) said they did not know about asymptomatic transmission or said, incorrectly, that an infected person does need to show symptoms to spread Zika virus. About a fifth of travelers (18%) thought it was “very likely” someone infected with Zika virus will have symptoms.

Most travelers (78%) were aware that microcephaly is associated with Zika virus infection, but only about half (48%) were aware of the association between infection and other health outcomes in children, and even fewer (23%) were aware of the association with Guillain-Barré syndrome. About a quarter (23%) incorrectly indicated pneumonia is associated with Zika virus infection.

Awareness of Zika cases:

Only two-thirds of all travelers (66%) were aware that there were Zika cases in their destination (Table 3).

Table 3.

Awareness of Zika Cases in Destination Among Travelers from US States to Zika-Affected Areas

| As far as you knew before your trip, were there… | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (%) (n = 1,285) | HPa (%) (n = 72) | Non-HPa (%) (n = 1,213) | RAb (%) (n = 631) | Non-RAb (%) (n = 582) | |

| Any cases of Zika virus in [destination] (NET) | 66 | 82c | 65 | 69c | 60 |

| A lot of cases of Zika virus in [destination] | 11 | 41c | 9 | 11c | 6 |

| A few cases of Zika virus in [destination] | 55 | 41 | 56 | 57 | 54 |

| No cases of Zika virus in [destination] | 29 | 18 | 30 | 25 | 38c |

| Have never heard of Zika virus | 3 | 0 | 3 | 5c | 1 |

Household pregnancy (HP): Travelers who responded “Yes” to the question, “As far as you know, was anyone in your household pregnant or considering getting pregnant at the time of your trip to [destination]?” Non-HP: Travelers who responded “No,” “Don’t know,” or refused the question.

Reproductive age (RA): Female travelers 18–44 and male travelers 18–54 who responded “No,” “Don’t know,” or refused the question, “As far as you know, was anyone in your household pregnant or considering getting pregnant at the time of your trip to [destination]?” Non-RA: Female travelers 45+ and male travelers 55+ who responded “No,” “Don’t know,” or refused the question.

Percentage is statistically greater than comparison group.

Note: Results shown are weighted. Responses of refused <5% not shown.

Concern about Zika virus:

Concern about Zika virus among travelers as a whole was low, with approximately a quarter (24%) saying they were “very” or “somewhat” concerned about getting infected during their trip, and fewer (14%) saying the same about spreading the virus to others after their trip (Table 4).

Table 4.

Concern About Zika Virus Among Travelers from US States to Zika-Affected Areas

| During your stay in [destination], overall, how concerned were you that you (or someone traveling with you) would get infected with Zika virus? | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (%) (n = 1,285) | HPa (%) (n = 72) | Non-HPa (%) (n = 1,213) | RAb (%) (n = 631) | Non-RAb (%) (n = 582) | |

| Very/somewhat concerned (NET) | 24 | 72c | 22 | 28c | 13 |

| Very concerned | 8 | 45c | 6 | 8c | 3 |

| Somewhat concerned | 17 | 27 | 16 | 20c | 11 |

| Not very concerned | 36 | 17 | 37c | 32 | 45c |

| Not at all concerned | 36 | 11 | 37c | 34 | 41 |

| Have never heard of Zika virus | 3 | 0 | 3 | 5c | 1 |

| After your trip, how concerned were you that you could spread Zika virus to other people? | |||||

| Total (%) (n = 1,285) | HPa (%) (n = 72) | Non-HPa (%) (n = 1,213) | RAb (%) (n = 631) | Non-RAb (%) (n = 582) | |

| Very/somewhat concerned (NET) | 14 | 55c | 12 | 17c | 6 |

| Very concerned | 5 | 34c | 4 | 6c | 1 |

| Somewhat concerned | 9 | 20c | 8 | 11c | 5 |

| Not very concerned | 20 | 22 | 19 | 20 | 19 |

| Not at all concerned | 62 | 23 | 64c | 58 | 73c |

| Have never heard of Zika virus | 3 | 0 | 3 | 5c | 1 |

Household pregnancy (HP): Travelers who responded “Yes” to the question, “As far as you know, was anyone in your household pregnant or considering getting pregnant at the time of your trip to [destination]?” Non-HP: Travelers who responded “No,” “Don’t know,” or refused the question.

Reproductive age (RA): Female travelers 18–44 and male travelers 18–54 who responded “No,” “Don’t know,” or refused the question, “As far as you know, was anyone in your household pregnant or considering getting pregnant at the time of your trip to [destination]?” Non-RA: Female travelers 45+ and male travelers 55+ who responded “No,” “Don’t know,” or refused the question.

Percentage is statistically greater than comparison group.

Note: Results shown are weighted. Responses of refused <5% not shown.

Awareness of information about protective behaviors:

About half of all travelers (54%) had heard or seen information before their trip about how to protect themselves or other travelers from Zika virus (Table 5). When asked about awareness of specific precautions to prevent the spread of Zika virus after a trip to a Zika-affected area, a majority (63%) had heard that people should see a doctor if they have symptoms of Zika after the trip, while far fewer had heard others: that men should use a condom every time during sex or abstain from sex for at least 6 months after travel to a Zika-affected area (26%), that women should do the same for at least 8 weeks (25%), or that a person should use insect repellent for 3 weeks (21%).

Table 5.

Awareness of Protective Information and Post-Travel Recommendations Among Travelers from US States to Zika-Affec ted Areas

| Before your trip, did you hear or see any information about how to protect yourself or other travelers from Zika virus? | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (%) (n = 1,285) | HPa (%) (n = 72) | Non-HPa (%) (n = 1,213) | RAb (%) (n = 631) | Non-RAb (%) (n = 582) | |

| Yes | 54 | 87c | 52 | 50 | 56 |

| No | 42 | 13 | 44c | 45 | 43 |

| Have never heard of Zika virus | 3 | 0 | 3 | 5c | 1 |

| Had you heard or seen any of the following specific precautions people can take to prevent spreading Zika virus to other people after a trip? | |||||

| Total (%) (n = 1,285) | HPa (%) (n = 72) | Non-HPa (%) (n = 1,213) | RAb (%) (n = 631) | Non-RAb (%) (n = 582) | |

| See a doctor if you have symptoms of Zika virus | 63 | 55 | 63 | 61 | 66 |

| Men should use a condom every time during sex or abstain from sex for at least 6 months after travel to an area with Zika virus | 26 | 29 | 26 | 27 | 25 |

| Women should use a condom every time during sex or abstain from sex for at least 8 weeks after travel to an area with Zika virus | 25 | 25 | 25 | 26 | 23 |

| Use insect repellent for 3 weeks after travel to an area with Zika virus | 21 | 43c | 20 | 23c | 16 |

| Refused | 12 | 5 | 12 | 11 | 14 |

| Have never heard of Zika virus | 3 | 0 | 3 | 5c | 1 |

Household pregnancy (HP): Travelers who responded “Yes” to the question, “As far as you know, was anyone in your household pregnant or considering getting pregnant at the time of your trip to [destination]?” Non-HP: Travelers who responded “No,” “Don’t know,” or refused the question.

Reproductive age (RA): Female travelers 18–44 and male travelers 18–54 who responded “No,” “Don’t know,” or refused the question, “As far as you know, was anyone in your household pregnant or considering getting pregnant at the time of your trip to [destination]?” Non-RA: Female travelers 45+ and male travelers 55+ who responded “No,” “Don’t know,” or refused the question.

Percentage is statistically greater than comparison group.

Note: Results shown are weighted. Responses of refused <5% not shown.

Adoption of protective behaviors during travel and after travel:

Relatively small fractions of travelers consistently adopted each protective behavior during their trip. Approximately a fifth of travelers (21%) said they used insect repellent outdoors “all the time,” and an additional 18% used it “most of the time” (Table 6a). Just 14% of travelers said they wore both long-sleeved shirts and pants “all the time” when they were outdoors, and an additional 12% said they did this “most of the time.” Among travelers who were with a sexual partner during their trip, 43% reported using condoms “every time” (14%) or not having sex (29%). Most travelers who adopted these behaviors “all the time” or “every time” said protecting themselves from Zika virus was a “major reason” for doing so. More said this was a “major reason” for using insect repellent “all the time” than wearing long-sleeved shirts and pants “all the time” or using condoms “every time” (79% vs 60% and 57%, respectively; data not shown).

Table 6a.

Protective Behaviors During Travel Among Travelers from US States to Zika-Affected Areas

| During your stay in [destination], how often did you use insect repellent outdoors? | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (%) (n = 1,285) | HPa (%) (n = 72) | Non-HPa (%) (n = 1,213) | RAb (%) (n = 631) | Non-RAb (%) (n = 582) | |

| All the time | 21 | 55c | 20 | 22 | 17 |

| Most of the time | 18 | 15 | 18 | 18 | 19 |

| About half the time | 11 | 14 | 10 | 12 | 8 |

| Not very often | 16 | 12 | 16 | 19 | 13 |

| Never | 33 | 4 | 35c | 29 | 43c |

| During your stay in [destination], how often did you wear both long-sleeved shirts and long pants when you were outdoors? | |||||

| Total (%) (n = 1,285) | HPa (%) (n = 72) | Non-HPa (%) (n = 1,213) | RAb (%) (n = 631) | Non-RAb (%) (n = 582) | |

| All the time | 14 | 51c | 12 | 15c | 9 |

| Most of the time | 12 | 8 | 13 | 13 | 12 |

| About half the time | 14 | 10 | 14 | 15 | 13 |

| Not very often | 28 | 18 | 29 | 28 | 30 |

| Never | 31 | 13 | 32c | 29 | 35 |

| During your stay in [destination], how often did you use condoms during sex? (among those who say they were with a sexual partner during the trip) | |||||

| Total (%) (n = 917) | HPa (%) (n = 67) | Non-HPa (%) (n = 850) | RAb (%) (n = 441) | Non-RAb (%) (n = 409) | |

| Used condoms every time or did not have sex (NET) | 43 | 42 | 44 | 41 | 47 |

| Did not have sex during the trip | 29 | 1 | 31c | 21 | 44c |

| Used condoms every time | 14 | 40c | 13 | 20c | 3 |

| Used condoms most of the time | 6 | 23c | 5 | 8c | 1 |

| Used condoms about half the time | 4 | 6 | 4 | 6c | 1 |

| Used condoms not very often | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 2 |

| Never used condoms | 43 | 26 | 44c | 41 | 48 |

Household pregnancy (HP): Travelers who responded “Yes” to the question, “As far as you know, was anyone in your household pregnant or considering getting pregnant at the time of your trip to [destination]?” Non-HP: Travelers who responded “No,” “Don’t know,” or refused the question.

Reproductive age (RA): Female travelers 18–44 and male travelers 18–54 who responded “No,” “Don’t know,” or refused the question, “As far as you know, was anyone in your household pregnant or considering getting pregnant at the time of your trip to [destination]?” Non-RA: Female travelers 45+ and male travelers 55+ who responded “No,” “Don’t know,” or refused the question.

Percentage is statistically greater than comparison group.

Note: Results shown are weighted. Responses of refused <5% not shown.

Only 1 in 10 travelers (9%) used insect repellent outdoors “all the time” in the 3 weeks after their return home (or since they returned home, if it had been less than 3 weeks) (Table 6b). Among those who were with a sexual partner after the trip, only a fifth (19%) used condoms during sex or abstained from sex “the whole time” for the recommended period after their return home (8 weeks for women and 6 months for men). Many of those travelers said preventing the spread of Zika virus was a “major reason” for adopting these behaviors, though more said that this was a “major reason” for using insect repellent as compared to using condoms or abstaining from sex (66% and 47%, respectively; data not shown).

Table 6b.

Protective Behaviors after Travel Among Travelers from US States to Zika-Affected Areas

| (In the time since you returned home/In the three weeks after you returned home), how often did you use insect repellent outdoors? | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (%) (n = 1,285) | HPa (%) (n = 72) | Non-HPa (%) (n = 1,213) | RAb (%) (n = 631) | Non-RAb (%) (n = 582) | |

| All the time | 9 | 43c | 7 | 9c | 3 |

| Most of the time | 11 | 23c | 10 | 12 | 8 |

| About half the time | 9 | 8 | 9 | 12c | 5 |

| Not very often | 19 | 3 | 20c | 19 | 21 |

| Never | 52 | 23 | 53c | 47 | 62c |

| (In the time since you returned home/In the eight weeks after you returned home/In the six months since you returned home), how often did you use condoms during sex or abstain from sex? (among those who say they were with a sexual partner after the trip) | |||||

| Total (%) (n = 954) | HPa (%) (n = 69) | Non-HPa (%) (n = 885) | RAb (%) (n = 518) | Non-RAb (%) (n = 367) | |

| The whole time | 19 | 46c | 17 | 21c | 10 |

| Most of the time | 10 | 19c | 9 | 13c | 3 |

| About half the time | 6 | 7 | 6 | 9c | 1 |

| Not very often | 6 | 0 | 7 | 9c | 3 |

| Never | 57 | 26 | 59c | 46 | 80c |

Household pregnancy (HP): Travelers who responded “Yes” to the question, “As far as you know, was anyone in your household pregnant or considering getting pregnant at the time of your trip to [destination]?” Non-HP: Travelers who responded “No,” “Don’t know,” or refused the question.

Reproductive age (RA): Female travelers 18–44 and male travelers 18–54 who responded “No,” “Don’t know,” or refused the question, “As far as you know, was anyone in your household pregnant or considering getting pregnant at the time of your trip to [destination]?” Non-RA: Female travelers 45+ and male travelers 55+ who responded “No,” “Don’t know,” or refused the question.

Percentage is statistically greater than comparison group.

Note: Results shown are weighted. Responses of refused <5% not shown.

Findings Among Household Pregnancy (HP) Travelers

Knowledge of Zika symptoms, transmission, and complications:

HP travelers were generally more knowledgeable about Zika virus disease than non-HP travelers, but they were also more likely to have incorrect information (Table 2). For example, while HP travelers were more likely to correctly identify common symptoms of Zika such as fever, headache, and joint pain, they were also more likely to say incorrectly that coughing and sneezing are common symptoms (57% vs 34%). HP travelers were also less likely to know that Zika virus can be transmitted without symptoms compared to non-HP travelers (50% vs 66%). HP travelers were also more likely to say, incorrectly, that someone infected with Zika virus will “very likely” have symptoms compared to non-HP travelers (47% vs 17%).

Awareness of Zika cases:

HP travelers were more likely than non-HP travelers to be aware of Zika cases in their destination (82% vs 65%) (Table 3).

Concern about Zika virus:

HP travelers were much more likely to be concerned (“very” or “somewhat”) about getting infected during travel than non-HP travelers (72% vs 22%) and more likely to be “very” concerned specifically (45% vs 6%) (Table 4).

Awareness of information about protective behaviors:

HP travelers were more likely than non-HP travelers to report having heard or seen protective information before their trip (87% vs 52%) (Table 5). Fewer than half of HP travelers were aware that a person should use insect repellent for 3 weeks after travel to a Zika-affected area (43%), though awareness was greater than among non-HP travelers (20%). They were no more aware of the other post-travel recommendations compared to non-HP travelers.

Adoption of protective behaviors during travel and after travel:

HP travelers were much more likely to adopt 2 of the behaviors asked about: wearing insect repellent outdoors “all the time” (55% vs 20%) and wearing long-sleeved shirts and pants outdoors “all the time” (51% vs 12%) (Table 6a). HP travelers who had a sexual partner during their trip were no more likely to be protected from sexual transmission (by either not having sex or by using condoms during sex “every time”). When asked about post-travel behavior, HP travelers were more likely than non-HP travelers to have used insect repellent outdoors “all the time” in the 3 weeks after their return home (43% vs 7%) (Table 6b). Among those who had a sexual partner after the trip, HP travelers were also more likely than non-HP travelers to say they used condoms or abstained from sex “the whole time” during the recommended period (46% vs 17%).

Findings Among Reproductive Age (RA) Travelers

Knowledge of Zika symptoms, transmission, and complications:

RA travelers were more likely than non-RA travelers to incorrectly name coughing and sneezing as a common Zika symptom (39% vs 27%) (Table 2). They were also less likely to be aware of several ways to protect from mosquito transmission of Zika virus, including using insect repellent (80% vs 92%) and wearing long-sleeved shirts and pants outdoors (76% vs 90%). They were also less likely than non-RA travelers to be aware of microcephaly as a complication of Zika virus (72% vs 87%).

Awareness of Zika cases:

RA travelers were no more likely than non-RA travelers to have been aware of Zika cases in their destination (Table 3).

Concern about Zika virus:

RA travelers were more likely than non-RA travelers to be concerned (“very” or “somewhat”) about Zika virus infection during travel (28% vs 13%), but there were not meaningful differences with regard to being “very” concerned specifically (Table 4).

Awareness of information about protective behaviors:

RA travelers were no more likely than non-RA travelers to have been aware of travel-related protective information or of post-travel recommendations (Table 5).

Adoption of protective behaviors during travel and after travel:

There were few behavioral differences between RA travelers and non-RA travelers during travel or after (Tables 6a and 6b). The only exception was that, among those who had a sexual partner after the trip, RA travelers were more likely than non-RA travelers to say they used condoms or abstained from sex “the whole time” during the recommended period (21% vs 10%).

Behaviors and Reasoning Among Knowledgeable Travelers

More than half of all travelers (60%) were aware there were Zika cases in their destination and knew that using insect repellent can protect against Zika virus (data not shown). Among this group of knowledgeable travelers, a quarter (27%) reported using insect repellent “all the time” during their trip, which is slightly more than those without this knowledge (13%) (Table 7).

Table 7.

Behaviors and Reasoning Among “Knowledgeable” Travelers from US States to Zika-Affected Areas

| During your stay in [destination], how often did you use insect repellent outdoors? | ||

|---|---|---|

| Knowledgeablea (%) (n = 803) | Not Knowledgeablea (%) (n = 482) | |

| All the time | 27c | 13 |

| Not all the time (NET) | 73 | 87c |

| Most of the time | 21c | 13 |

| About half the time | 11 | 9 |

| Not very often | 15 | 18 |

| Never | 26 | 45c |

| What are the reasons that you did not use it outdoors all the time in [destination]? (among those who say they did not use insect repellent all the time) | ||

| Knowledgeablea (%) (n = 531) | ||

| Low Perceived Risk (NET) | 59 | |

| Was not in places with a lot of mosquitoes | 58 | |

| No Zika threat in the area when I was there | 1 | |

| Hassle (NET) | 43 | |

| Don’t like the way it smells or feels | 21 | |

| Too difficult to remember to put it on | 13 | |

| Difficult to bring it on flights | 10 | |

| Too much of a bother | 10 | |

| Too expensive | 4 | |

| Does not work well | 3 | |

| Other | 7 | |

| During your stay in [destination], how often did you wear both long-sleeved shirts and long pants when you were outdoors? | ||

| Knowledgeableb (%) (n = 769) | Not Knowledgeableb (%) (n = 516) | |

| All the time | 18c | 8 |

| Not all of the time (NET) | 82 | 92c |

| Most of the time | 14 | 10 |

| About half the time | 14 | 13 |

| Not very often | 26 | 30 |

| Never | 27 | 37c |

| What are the reasons you did not do this all the time in [destination]? (among those who say they did not wear both long-sleeved shirts and long pants when outdoors all the time) | ||

| Knowledgeableb (%) (n = 601) | ||

| Comfort (NET) | 78 | |

| It was too hot | 74 | |

| Long-sleeved shirts and pants are uncomfortable | 15 | |

| Low Perceived Risk (NET) | 40 | |

| Was not in places with a lot of mosquitoes | 40 | |

| Appearance (NET) | 25 | |

| Wanted to get a tan | 17 | |

| What are the reasons you did not do this all the time in [destination]? (among those who say they did not wear both long-sleeved shirts and long pants when outdoors all the time) | ||

| Knowledgeableb (%) (n= 601) | ||

| Few people in [destination] wear long-sleeved shirts and pants | 9 | |

| Long-sleeved shirts and pants do not look good | 5 | |

| Hassle (NET) | 4 | |

| Long-sleeved shirts and pants take up too much room in my suitcase | 4 | |

| Other | 5 | |

| During your stay in [destination], how often did you use condoms during sex? (among those who say they had sex during the trip) | ||

| Knowledgeabled (%) (n = 288) | Not Knowledgeabled (%) (n = 358) | |

| Every time | 31c | 12 |

| Not every time (NET) | 68 | 86c |

| Most of the time | 9 | 7 |

| About half the time | 5 | 6 |

| Not very often | 1 | 7c |

| Never | 52 | 66c |

| What are the reasons that you did not use them every time in [destination]? (among those who say they did not condoms every time) | ||

| Knowledgeabled (%) (n =173) | ||

| Being in a Committed Relationship (NET) | 55 | |

| I/my partner was in a committed relationship | 55 | |

| Low Perceived Risk (NET) | 54 | |

| Used another kind of contraception/birth control | 22 | |

| Did not think I/my partner was infected with Zika virus | 21 | |

| I/my partner was not pregnant | 17 | |

| Unable to get pregnant | 4 | |

| Hassle (NET) | 8 | |

| Partner does not like to use them | 6 | |

| Uncomfortable/decrease sexual pleasure | 3 | |

| Too much of a bother | 1 | |

| I/my partner wanted to get pregnant | 5 | |

| Too expensive | 2 | |

| Religious reasons | 2 | |

| Could not get them | 1 | |

| Other | 1 | |

Travelers who knew there were Zika cases in their destination and knew people can protect themselves from getting Zika virus by using insect repellent when going outdoors; Not knowledgeable: All other travelers.

Travelers who knew there were Zika cases in their destination and knew people can protect themselves from getting Zika virus by wearing long-sleeved shirts and long pants when going outdoors; Not knowledgeable: All other travelers.

Percentage is statistically greater than comparison group.

Travelers who knew there were Zika cases in their destination and knew people can protect themselves from getting Zika virus by consistently using condoms during sex; Not knowledgeable: All other travelers.

Note: Results shown are weighted. Responses of don’t know or refused <5% not shown.

Among the 73% of knowledgeable travelers who did not consistently use insect repellent, reasons for not adopting this behavior can be grouped into several themes. Most (59%) cited reasons related to a low perceived risk of Zika virus infection, including 58% who said they were not in places with “a lot of” mosquitoes and an additional 1% who said there was no Zika virus threat in the area during their visit. Approximately 4 in 10 (43%) gave reasons relating to the hassle of insect repellent, including not liking the way it smells or feels (21%), finding it too difficult to remember to put it on (13%), finding it difficult to bring on flights (10%), or considering it too much of a bother (10%). Only 4% indicated cost was a barrier, and just 3% cited belief that it does not work well.

More than half of all travelers (57%) were aware there were Zika cases in their destination and knew that wearing long-sleeved shirts and pants can protect against Zika virus (data not shown). Among this group of knowledgeable travelers, only 18% reported wearing long-sleeved shirts and pants “all the time.” Reports of this protective behavior were higher than among those without this knowledge (8%). Among the 82% of knowledgeable travelers who did not consistently wear protective clothing, approximately three-quarters (78%) cited reasons relating to comfort, including 74% who said it was because it was too hot and 15% who said it was because long-sleeved shirts and pants are uncomfortable. Four in 10 (40%) said they felt they were not in places with “a lot of” mosquitoes, suggesting low perceived risk of infection. A quarter (25%) cited reasons related to appearance, such as wanting to get a tan (17%); that few people in their destination wear long-sleeved shirts and pants (9%); or that such clothes do not look good (5%). Few cited the hassle of bringing these items: only 4% said it was because long-sleeved shirts and pants take up too much room in a suitcase.

Approximately 4 in 10 travelers (41%) were aware there were Zika cases in their destination and knew using condoms consistently can protect against Zika virus (data not shown). Among this group of knowledgeable travelers who also said they had sex during the trip, only 31% reported using a condom “every time,” compared to 12% of those without this knowledge.

Among the 68% of knowledgeable travelers who did not consistently use condoms, about half (55%) said it was because they were in a committed relationship. A majority also (54%) mentioned reasons related to low perceived risk of infection or pregnancy-related complications, including using another kind of birth control (22%), not thinking they were or their partner was infected with Zika virus (21%), they or their partner not being pregnant (17%), and being unable to get pregnant (4%). Fewer mentioned other reasons like the hassle of condom use (8%), a desire to get pregnant (5%), or cost (2%).

Discussion

Data from this study provide important insights into awareness, knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors among those who traveled from US states to areas with active Zika virus transmission during the peak of global transmission. Given that Zika remains a risk in many popular tourist destinations around the world,5 findings have important implications for communication and mobilization efforts targeting travelers to those areas.

At the fore, data point to key successes and opportunities among travelers in households where someone was pregnant or considering getting pregnant at the time of the trip. By multiple measures, these travelers were more aware, more knowledgeable, and more concerned and adopted more protective behaviors. This suggests receptivity among this small, but high-risk, population and may imply the utility of segmented and tailored communication approaches.40

Findings also show several areas of concern. First, sizable shares of travelers were not aware of Zika cases in their destination and did not know basic information about asymptomatic transmission, sexually related modes of virus transmission, or post-travel protective behaviors. Insofar as creating a knowledge base is often a foundational piece of a communication campaign, addressing these particular gaps is important. Beyond reaching more travelers with these facts, it may be important to account for the complexity of recommendations, which may make it difficult for travelers to take in the information.41 For example, as Zika virus is the first virus known to have both mosquito and sexual transmission routes, this fact may be difficult for travelers to understand.36 It may therefore be important to emphasize consistently in broad communications to travelers that there are 2 major routes of transmission—even if a given communication piece is primarily focused on 1 or the other mode.

Second, multiple data points suggest that levels of concern and risk perception about Zika virus infection and transmission were low among all traveler groups apart from travelers in households where someone was pregnant or considering becoming pregnant at the time of the trip. Travelers of reproductive age who are not considering pregnancy may nonetheless be at risk of unintended pregnancy and thus Zika-associated birth defects, and those who are not at risk personally may still be able to bring back the virus.42 Tailoring risk-related messaging to these groups with low levels of perceived and actual risk for pregnancy-related outcomes may be needed.9 For example, if pregnancy-related outcomes feel irrelevant to some people, motivating action may be more effective if communications emphasize short-term health consequences of Zika or other risks not directly related to infection—like the risk of itchy bug bites.43

Third, findings show that few travelers adopted protective behaviors during or after their trip, and adoption is low even among travelers who knew there were Zika cases in the area and what actions they could take. This suggests that reasons for not adopting behaviors are based on considerations beyond the facts about Zika virus. This idea is reinforced when looking directly at reasons travelers said they did not adopt behaviors. For example, many knowledgeable travelers said this was because the protective measures are a hassle. These findings reinforce the importance of ensuring that communication campaigns take social context into account.

Fourth, we note that adoption of behaviors that are predictably less appealing—like wearing long-sleeved shirts and pants in hot climates—was particularly low. Thus, with tight resource constraints for public health communication efforts, it may be worth prioritizing more palatable or feasible protective measures (eg, using repellent) in order to have a stronger impact on behavioral response overall.44

The study has limitations. First, the data are cross-sectional, and thus causal links cannot be made between awareness, knowledge, or attitudes with behaviors. Second, all data are self-reported. Despite efforts to minimize social desirability bias through question wording and order, self-reported behavior, in particular, may be inflated compared to observed behavior. Third, the sample of travelers in households where someone is pregnant or considering becoming pregnant was small. Though reported findings were statistically significant and sizable on an absolute scale (10pp or more), we note the smaller size nonetheless. Fourth, the findings may not apply to nonrespondents, who may be less likely to take actions in general, which could also inflate estimated behavior response. A fifth limitation relates to the non-probability source for part of the sample; because non-probability panel respondents may be more motivated to participate in surveys and in other activities than other people, this could also inflate behavior estimates. Because all of these limitations may inflate behavior estimates, they ultimately underscore the study’s overall findings of low behavioral response. Finally, the specific guidance for timing of abstinence or condom use post-travel has changed from 6 months to at least 3 months for men with female partners who are not pregnant, and this could not be reflected in the questionnaire.5 There may be more willingness to adopt these measures for a shorter amount of time, but we do not anticipate much change given the relatively low adoption during travel, when time spans were often shorter and the immediate risk may have seemed greater.

Despite these limitations, we believe the findings provide evidence about the challenges and opportunities related to motivating travelers to adopt protective behaviors during and after their trips to Zika-affected areas. Effective communication may benefit from a long-term approach in which messages are tailored to those with different levels of actual and perceived risk. Such communication needs to address gaps in knowledge about asymptomatic and sexual transmission risk and post-travel protective behaviors. Information needs to go beyond facts and take into account the complexities of recommendations and the social context of behaviors. There may also need to be priority placed on reaching the highest-risk segments, on behaviors that are easier or more appealing, or on the costs/benefits of behaviors beyond Zika virus protection.

Beyond the implications for communicating about Zika virus specifically, these findings have implications for communicating effectively about infectious disease outbreaks when the public is less familiar with a pathogen. Findings reinforce the potential challenges of motivating protective behaviors when scientific knowledge is evolving and when the risks of an illness are not distributed equally across the population. The study also reinforces the importance of collecting high-quality data about how people understand and respond to such infectious disease outbreaks. Such data can immediately help adapt communication strategies during the course of the outbreak in order to contain outbreaks as quickly as possible and reduce the health impacts on the population. Publication of these data later can then create a foundation to guide planning and early communications in future outbreaks. Most broadly, this study suggests the need for more support for public health communication related to emerging infectious diseases in the United States.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was conducted through a cooperative agreement between CDC and the National Public Health Information Coalition (NPHIC), who subsequently subcontracted to HSPH. Researchers at HSPH led the study design, questionnaire design, and analysis of de-identified data. Staff at CDC and NPHIC contributed to questionnaire design and provided subject matter expertise. None of the authors were involved directly in data collection. All authors were involved in manuscript development and all approved the decision to submit the manuscript. All authors acted in a personal capacity. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of CDC, any other portion of the government of the United States, NPHIC, HSPH, or SSRS. The authors are grateful for the contributions of Allie Caccamo, Blanche Collins, Joanne Cox, Angela Colson, Katherine Lyon Daniel, Alan Dowell, Sascha Elington, Stefanie Erskine, Laura Espina, Alina Flores, Fred Fridinger, Ronnie Henry, Rachel Kachur, Betsy Mitchell, Megan O’Sullivan, Sue Partridge, Laura Pechta, Kara Polen, Alfonso Rodriguez, Alina Shaw, Lynn Sokler, Jo Stryker, Carolina Uribe, and Cathy Young to the questionnaire and Linda Lomelino, Rebecca Sevem, and Emily Hachey to data analysis.

Contributor Information

Gillian K. SteelFisher, Harvard Opinion Research Program.

Hannah Caporello, Harvard Opinion Research Program.

Robert J. Blendon, Department of Health Policy and Management, Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA..

Eran N. Ben-Porath, Public Opinion Research, SSRS, Glen Mills, PA..

Keri Lubell, Division of Emergency Operations, Center for Preparedness and Response.

Allison L. Friedman, Travelers’ Health Branch, Division of Global Migration & Quarantine, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases.

Kelly Holton, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA..

Belinda J. Smith, Health Communication Specialist, McKing Consulting Corporation, Atlanta, GA..

Ericka McGowan, Infectious Disease Preparedness, Association for State and Territorial Health Officials, Arlington, VA..

Thomas Schafer, National Public Health Information Coalition, Marietta, GA..

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Zika cases in the United States. Last reviewed March 13, 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/zika/reporting/case-counts.html. Accessed July 24, 2019.

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Advice for people living in or traveling to South Florida. Last reviewed June 4, 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/zika/intheus/florida-update.html. Accessed July 24, 2019.

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Advice for people living in or traveling to Brownsville, Texas. Last reviewed June 4, 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/zika/intheus/texas-update.html. Accessed July 24, 2019.

- 4.Armstrong P, Hennessey M, Adams M, et al. Travel-associated Zika virus disease cases among U.S. residents—United States, January 2015-February 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65(11):286–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Zika travel information. Last reviewed June 28, 2019. https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/page/zika-travel-information. Accessed July 24, 2019.

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevent mosquito bites. Last reviewed August 24, 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/zika/prevention/prevent-mosquito-bites.html. Accessed July 24, 2019.

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexual transmission and prevention. Last reviewed May 21, 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/zika/prevention/sexual-transmission-prevention.html. Accessed July 24, 2019.

- 8.Fisher JD, Fisher WA. Changing AIDS-risk behavior. Psychol Bull 1992;111(3):455–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brewer NT, Chapman GB, Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, McCaul KD, Weinstein ND. Meta-analysis of the relationship between risk perception and health behavior: the example of vaccination. Health Psychol 2007;26(2):136–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reynolds B, W Seeger M. Crisis and emergency risk communication as an integrative model. J Health Commun 2005; 10(1):43–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berenson AB, Hirth JM, Guo F, Fuchs EL, Weaver SC. Prevention practices among United States pregnant women who travel to Zika outbreak areas. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2018; 98(1):178–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Whittemore K, Tate A, Illescas A, et al. Zika virus knowledge among pregnant women who were in areas with active transmission. Emerg Infect Dis 2017;23(1):164–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Teich A, Lowenfels AB, Solomon L, Wormser GP. Gender disparities in Zika virus knowledge in a potentially at-risk population from suburban New York City. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2018;92(4):315–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Squiers L, Herrington J, Kelly B, et al. Zika virus prevention: U.S. travelers’ knowledge, risk perceptions, and behavioral intentions—a national survey. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2018; 98(6):1837–1847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vielot NA, Stamm L, Herrington J, et al. United States travelers’ concern about Zika infection and willingness to receive a hypothetical Zika vaccine. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2018;98(6):1848–1856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Samuel G, DiBartolo-Cordovano R, Taj I, et al. A survey of the knowledge, attitudes and practices on Zika virus in New York City. BMC Public Health 2018;18(1):98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Omodior O, Luetke MC, Nelson EJ. Mosquito-borne infectious disease, risk-perceptions, and personal protective behavior among U.S. international travelers. Prev Med Rep 2018;12:336–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nelson EJ, Luetke MC, McKinney C, Omodior O. Knowledge of the sexual transmission of Zika virus and preventive practices against Zika virus among U.S. travelers. J Community Health 2019;44(2):377–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.KnowledgePanel®: A Methodological Overview. Palo Alto, CA: GfK; 4 p. [Google Scholar]

- 20.DiSogra C, Callegaro M. Computing response rates for probability-based web panels. Paper presented at: Joint Statistical Meetings (JSM); Aug 1–6, 2009; Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 21.American Association for Public Opinion Research. Online panels. https://www.aapor.org/Education-Resources/ElectionPolling-Resources/Online-Panels.aspx. Accessed July 24, 2019.

- 22.Hays RD, Liu H, Kapteyn A. Use of internet panels to conduct surveys. Behav Res Methods 2015;47(3):685–690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.U.S. Census Bureau. Current population survey. Annual social and economic supplement. Last revised March 6, 2018. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/cps/data-detail.html. Accessed July 24, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hamer DH, Connor BA. Travel health knowledge, attitudes and practices among United States travelers. J Travel Med 2004;11(1):23–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Genderen PJ, van Thiel PP, Mulder PG, Overbosch D; Dutch Schiphol Airport Study Group. Trends in the knowledge, attitudes and practices of travel risk groups toward prevention of hepatitis B: results from the repeated cross-sectional Dutch Schiphol Airport Survey 2002–2009. Travel Med Infect Dis 2014;12(2):149–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zimmermann R, Hattendorf J, Blum J, Nuesch R, Hatz C. Risk perception of travelers to tropical and subtropical countries visiting a Swiss travel health center. J Travel Med 2013;20(1):3–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dennis B, Sun LH, Clement S. Americans were more worried about Ebola than they are about Zika. Washington Post June 30, 2016. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/to-your-health/wp/2016/06/30/americans-were-more-worried-about-ebola-than-they-are-about-zika/?utm_term=.e48bce3981e1. Accessed July 24, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harvard Opinion Research Program. Zika virus and the election season. Boston: Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health; 2016. https://cdn1.sph.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/94/2016/08/STAT-Harvard-Poll-August2016-Zika.pdf. Accessed July 24, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rainie L, Funk C. Half of Americans say threats from infectious diseases are growing. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center; 2016. http://assets.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/14/2016/07/PS_2016.07.07_Zika_FINAL.pdf. Accessed July 24, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 30.SteelFisher GK, Blendon RJ, Bekheit MM, Lubell K. The public’s response to the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic. N Engl J Med 2010;362(22):e65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.SteelFisher GK, Blendon RJ, Lasala-Blanco N. Ebola in the United States—public reactions and implications. N Engl J Med 2015;373(9):789–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rubin GJ, Amloˆt R, Page L, Wessely S. Public perceptions, anxiety, and behaviour change in relation to the swine flu outbreak: cross sectional telephone survey. BMJ 2009;339:b2651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJK, Curtin SC,Mathews TJ. Births: final data for 2013. Natl Vital Stat Rep 2015;64(1). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.SteelFisher GK, Blendon RJ, Bekheit MM, et al. Novel pandemic A (H1N1) influenza vaccination among pregnant women: motivators and barriers. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2011; 204(6 Suppl 1):S116–S123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fahimi M, Barlas F, Gross W, Thomas R. Towards a new math for non-probability sampling alternatives. Presented at: 69th AAPOR Annual Conference; May 15–18, 2014; Anaheim, CA. [Google Scholar]

- 36.SteelFisher GK, Benson JM, Caporello H, et al. Pharmacistviews on alternative methods for antiviral distribution and dispensing during an influenza pandemic. Health Secur 2018; 16(2):108–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.SteelFisher GK, Blendon RJ, Guirguis S, et al. Threats to polio eradication in high-conflict areas in Pakistan and Nigeria: a polling study of caregivers of children younger than 5 years. Lancet Infect Dis 2015;15(10):1183–1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.SteelFisher GK, Blendon RJ, Brulé AS, Ben-Porath EN, Ross LJ, Atkins BM. Public response to an anthrax attack: a multiethnic perspective. Biosecur Bioterror 2012;10(4):401–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.SteelFisher G, Blendon R, Ross LJ, et al. Public response to an anthrax attack: reactions to mass prophylaxis in a scenario involving inhalation anthrax from an unidentified source. Biosecur Bioterror 2011;9(3):239–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Slater MD. Choosing audience segmentation strategies and methods for health communication. In: Maibach E, Parrott RL, eds. Designing Health Messages: Approaches from Communication Theory and Public Health Practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 1995:186–198. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Parrott RL. Motivation to attend to health messages: presentation of content and linguistic considerations. In Maibach E, Parrott RL, eds. Designing Health Messages: Approaches from Communication Theory and Public Health Practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 1995: 7–23. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Finer LB, Zolna MR. Declines in unintended pregnancy in the United States, 2008–2011. N Engl J Med 2016;374(9): 843–852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Floyd DL, Prentice-Dunn S, Rogers RW. A meta-analysis of research on protection motivation theory. J Appl Soc Psychol 2000;30(2):407–429. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sallis JF, Owen N. Ecological models of health behavior. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K, eds. Health Behavior: Theory, Research, and Practice. 5th ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2015:43–64. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.