Description

We present a case involving an 82-year-old woman who has been experiencing bilateral progressive visual impairment for the past 2 years. She has a medical history of a 20-year progressive chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), which has recently transformed into myelofibrosis.

The patient underwent a comprehensive ophthalmic assessment, which included visual field tests, neurophysiological visual evaluations, cranial magnetic resonance imaging, full-body computerized tomography, a bone marrow biopsy, and various retinal imaging tests such as autofluorescence (AF) imaging, fundus fluorescein angiography (FFA), and spectral-domain macular optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT).

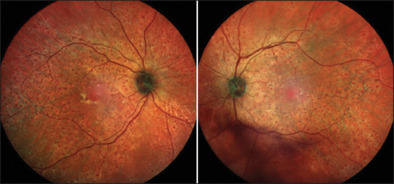

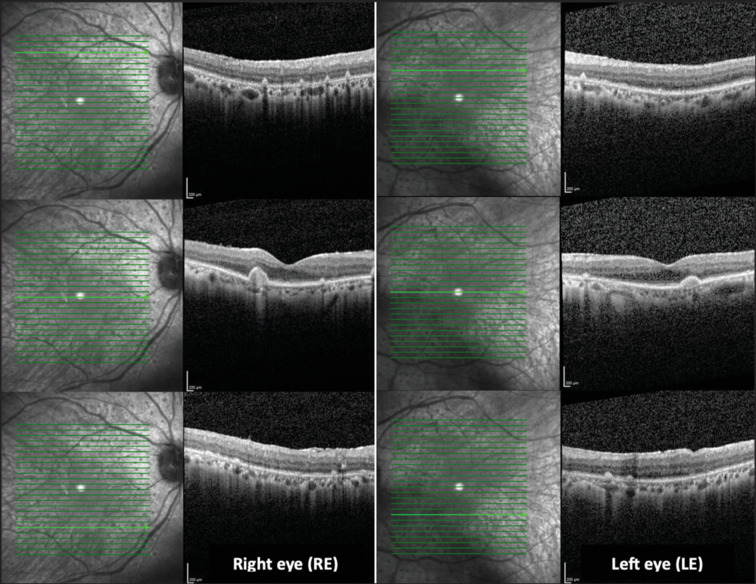

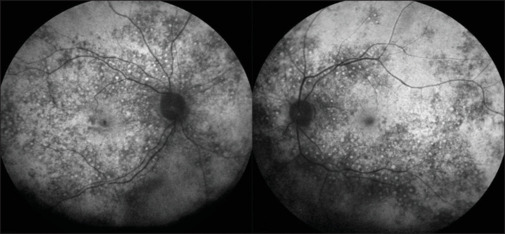

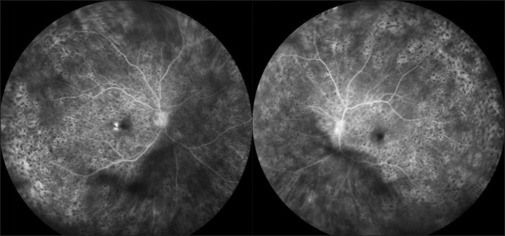

Her examination revealed normal pupil responses and proper external eye movement control. Her visual acuity was measured at 20/120 in her right eye and 20/60 in her left eye. She had successfully undergone bilateral cataract surgery, with intraocular pressure within the normal range. Bilateral small melanocytic-like nodules at the posterior pole, with minor involvement in the foveal area, were observed during the fundoscopic eye examination [Figure 1]. SD-OCT showed irregular damage to the retinal external segments, as well as drusen-like deposits above the retinal pigment epithelium [Figure 2]. AF and FFA revealed areas of hyper-AF and hypofluorescence spots, respectively, not objectifying leakage, neovascularization, or ischemia in FFA [Figures 3 and 4]. These findings raised suspicion of a bilateral diffuse melanocytic proliferation (BDUMP), leading to a comprehensive systemic evaluation that did not reveal any abnormalities. Neurophysiological and visual field tests exhibit bilateral impairment.

Figure 1.

Fundus retinography of both eyes

Figure 2.

Spectral-domain optical coherence tomography

Figure 3.

Autofluorescence images

Figure 4.

Fundus fluorescein angiography in both eyes

In an effort to reach a prognostication, a diagnostic vitrectomy was performed, but the results were inconclusive (IL-10 vitreous sample: 54.3 pg/ml; IL-10/IL-6 vitreous sample index: 1.38 pg/ml; flow cytometry results; monocytes at 64.6, NK cells at 7.7%, T-lymphocytes at 27.6%; CD4/CD8 index of 4.92, with absence of B-lymphocytes). After ruling out the possibility of primary vitreoretinal (PVR) lymphoma, and with the positive presence of anti-recoverin antibodies in a blood sample, the patient was diagnosed with a leopard-spot sign of fearsome cancer-associated retinopathy (CAR) in an evolved CML.[1]

The presence of leopard-spot retinopathy, as observed in this case, is an exceptionally rare finding.[2] It may be associated with primary ophthalmic conditions such as chronic central serous chorioretinopathy, idiopathic uveal effusion syndrome, or PVR lymphoma.[2,3,4] However, it can also serve as an ophthalmic indicator of a systemic and life-threatening illness including conditions like central nervous system lymphoma, malignant solid organ neoplasms and acute/chronic leukemia, presenting as either an autoimmune-like CAR or a BDUMP case[1,2,5] In such situations, it is crucial to conduct an exhaustive systemic evaluation, and the choice of treatment depends on the underlying etiopathology. When it signifies as a paraneoplastic signal, it portends a poor prognosis for both the patient’s overall health and vision.[2]

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patient has given her consent for her images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patient understands that her name and initials will not be published, and due efforts will be made to conceal her identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Yoon YH, Cho EH, Sohn J, Thirkill CE. An unusual type of cancer-associated retinopathy in a patient with ovarian cancer. Korean J Ophthalmol. 1999;13:43–8. doi: 10.3341/kjo.1999.13.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jabbarpoor Bonyadi MH, Ownagh V, Rahimy E, Soheilian M. Giraffe or leopard spot chorioretinopathy as an outstanding finding: Case report and literature review. Int Ophthalmol. 2019;39:1405–12. doi: 10.1007/s10792-018-0948-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iida T, Spaide RF, Haas A, Yannuzzi LA, Jampol LM, Lesser RL. Leopard-spot pattern of yellowish subretinal deposits in central serous chorioretinopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120:37–42. doi: 10.1001/archopht.120.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Casady M, Faia L, Nazemzadeh M, Nussenblatt R, Chan CC, Sen HN. Fundus autofluorescence patterns in primary intraocular lymphoma. Retina. 2014;34:366–72. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e31829977fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robert MP, Faure C, Reman O, Miocque S. Leopard spot retinopathy: An early clinical marker of leukaemia recurrence? Ann Hematol. 2008;87:927–9. doi: 10.1007/s00277-008-0510-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.