Abstract

Ophthalmic examination of a patient with active COVID-19 infection can be challenging. We describe a woman with active COVID-19 infection who was misdiagnosed initially as having conjunctivitis and later presented with acute angle-closure attack in both eyes. Intraocular pressure (IOP) on presentation was about 40 mmHg in both eyes. She was on multiple medications for her COVID-19 infection. A nonpupillary block mechanism of secondary angle closure was suspected and laser iridotomy was avoided. Her IOP was well controlled with medications. Due to significant cataract, phacoemulsification with IOL was performed using femto-assisted rhexis in lieu of the postdilatation IOP spike. There was good IOP control and 6/6 vision postoperatively. Bilateral angle closure of probable multifactorial cause can occur in COVID-19-positive patients.

Keywords: Bilateral angle closure, COVID-19, glaucoma

Introduction

The novel coronavirus is well-known to infect the human respiratory system. However, a number of ophthalmic manifestations also have been reported, namely conjunctivitis, scleritis, retinal vascular occlusions, papilledema, and anterior ischemic optic neuropathy.[1] While the exact incidence is unknown, angle-closure glaucoma (bilateral in this case) in a COVID-19-positive patient is relatively rare. The etiopathogenesis of the above is probably multifactorial. Here, we report a case of bilateral angle closure in a woman recovering from corona-related respiratory infection.

Case Report

A 64-year-old woman, known hypertensive presented to us with complaints of redness, watering, and headache of 10-day duration. She also gave a history of contracting coronavirus infection from her husband. She had developed fever and was admitted in a tertiary care hospital and discharged after 1 week. She was recommended 10 days of isolation and presented to us on the 5th day.

This happened during the first wave of the coronavirus pandemic when guidelines about eye examination were still evolving. To reduce the risk of transmission, a torch light examination was done and she was treated for conjunctivitis with antibiotics and lubricants. The next day, she presented with eye pain, cloudy vision, and nausea. Her vision was 2/60 in oculus dexter (OD) and 1/60 in oculus sinister (OS). Slit-lamp examination in OD showed circumcorneal congestion with diffuse microcystic epithelial corneal edema, anterior chamber was shallow with peripheral anterior chamber depth (PACD) <1/4 corneal thickness (CT). The pupil was 5 mm mid dilated sluggishly reacting to light, Grade 1 nuclear sclerosis. OS had similar findings. There was no clear view of the fundi. IOP by applanation tonometry using sterile precautions was 38 mmHg in the right eye and 40 mmHg in the left eye. Investigations requiring contact such as gonioscopy and B-scan ultrasonography were deferred. She was admitted and given 20% intravenous mannitol 200 ml and oral acetazolamide 250 mg 3 times a day. She was also given betamethasone eye drops 4 times a day, dorzolamide 2% eye drops, and a combination of 0.5% timolol maleate and 0.2% brimonidine eye drops. Postmannitol, her IOP was 26 mmHg in OD and 30 mmHg in OS. A careful review of systemic medication used to treat the COVID-19 infection was done. She had received vitamin supplements, intravenous heparin, cilnidipine 5 mg, domperidone 10 mg, pantoprazole 40 mg, and a combination of amoxicillin and clavulanate 375 mg. There was no history of prone positioning.

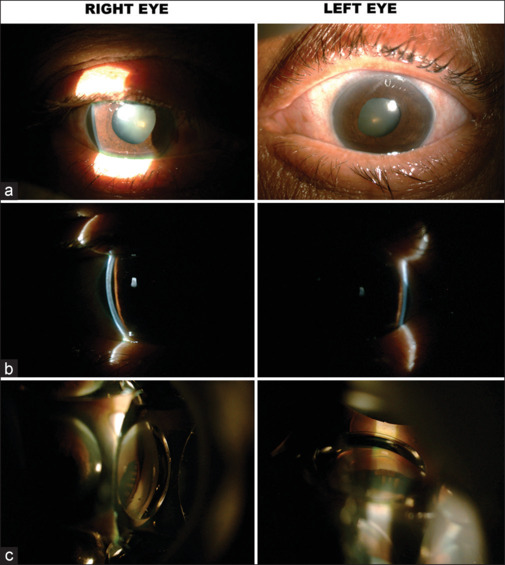

The following day slit-lamp examination revealed a clearer cornea with faint edema, shallow anterior chamber PACD ¼ TO ½ CT, and mid-dilated sluggish pupil [Figure 1]. Fundus examination showed hyperemic disc with blurring of disc margins. There was no choroidal detachment. Vision improved to 6/24 and 6/9 in OD and OS, respectively. IOP was 16 and 18 mmHg with topical antiglaucoma medications. Laser iridotomy was deferred suspecting a nonpupillary block mechanism and due to adequate IOP control with medications.

Figure 1.

(a) Slit lamp photograph of right and left eye showing congestion, shallow anterior chamber, middilated pupil and nuclear sclerosis grade 1. (b) Optical section of cornea showing Peripheral anterior chamber depth<1/4 Corneal Thickness. (c) Indirect gonioscopy 4 mirror lens: no angle structures visible, ciliary processes seen through dilated pupil

After 2 weeks, best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) in OD declined to 6/60 OS 6/12. The eye was quiet, anterior chamber remained shallow, and PACD ¼–½ CT. Cataracts had progressed in both eyes. Her IOP was under good control with three medications. Disc edema was reduced and cup–disc ratio was 0.3. Axial length measured by optical biometry was 22.78 mm in OD and 22.81 mm in OS. She underwent phacoemulsification with IOL implantation for both eyes sequentially in 1 week. On the day of surgery, postdilatation IOP recorded was 28 mm Hg in OD and 30 mm Hg in OS. After administering hyperosmotic agents, phacoemulsification was done. Capsulorhexis was performed using femtolaser (Catalys System®). Surgical peripheral iridectomy was done. No intraoperative complication was noted.

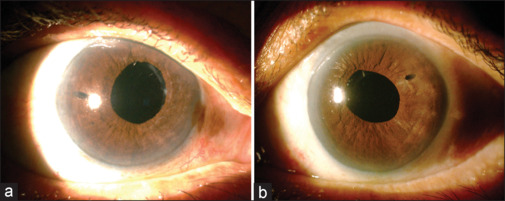

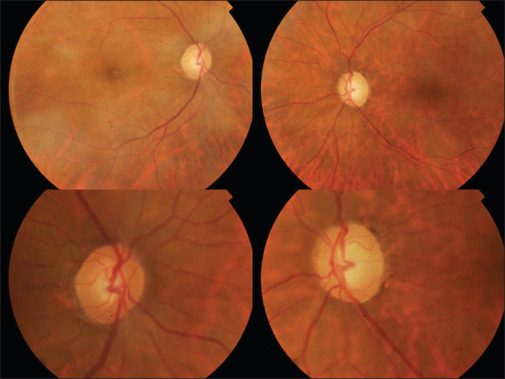

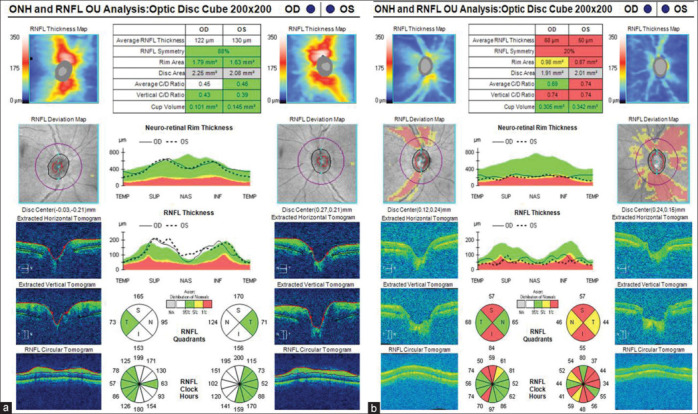

At the end of 1 week, BCVA was 6/6 in both eyes. Anterior chamber had deepened. IOP was 14 in OD and 16 mmHg in OS with timolol maleate 0.5% BD in both eyes [Figure 2]. Her optic nerve head showed mild temporal pallor with cup–disc ratio of 0.6 and 0.7 in OD and OS, respectively [Figure 3]. Optical coherence tomography of the retinal nerve fiber layer (OCT RNFL) centered around optic nerve head had shown increased retinal nerve fiber layer thickness due to disc edema during the phase of acute IOP rise [Figure 4a]. OCT was repeated at 1-month postcataract surgery. It showed bipolar thinning in both eyes [Figure 4b]. Her IOP and OCT RNFL parameters remained stable at the end of 6 months and 1 year of follow-up.

Figure 2.

Slit-lamp photograph of (a) right eye (b) left eye: clear cornea, patent surgical iridectomies, posterior chamber intraocular lenses

Figure 3.

Fundus photograph: Right eye media haze due to asteroid hyalosis, average sized disc, cup–disc ratio 0.6 sloping cup margins, left eye shows clear media, average sized disc with temporal palor, and cup disc ratio of 0.7 sloping cup margins

Figure 4.

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) of retinal nerve fiber layer (a) taken during first week of acute angle closure showing increased nerve fiber layer thickness due to disc edema. (b) OCT taken during last visit showing significant thinning in superior and inferior quadrants consistent with glaucomatous damage

Discussion

Bilateral angle-closure attack is a relatively rare ophthalmic emergency. Primary angle closure is unilateral in 80%–90% of patients. Bilateral attack is more commonly associated with idiosyncratic reaction secondary to ciliochoroidal effusion and increased iridolenticular contact.[2] Drugs such as topiramate, chlorothiazide, and sulfonamides are implicated. Furthermore, drugs which cause pupillary dilatation can cause pupillary block in eyes with already narrow anterior chamber angles.[3] A careful review of our patient’s medical record did not reveal the usage of such medications.

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic. The exact mechanism by which the eye is involved is unknown. The virus has been isolated intracellularly from tissues of conjunctiva, iris, and trabecular meshwork of patients even in the recovery phase of the infection by immunofluorescence studies[4] that detects the nucleocapsid protein antigen of the virus. This confirms that apart from the lungs, the eye is also a target for infection. The mortality and morbidity due to corona infection have been showing a declining trend. However, the disease prevalence was estimated to be 45 million worldwide between February and March 2023 by the World Health Organization in its epidemiological update. Although the pandemic might have ended, COVID-19 will remain a recurrent disease that healthcare professionals have to manage.[5]

Infection with SARS-CoV-2 has been associated with the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion[6] causing electrolyte abnormalities notably hyponatremia.[7] Just as hypertonic mannitol decreases IOP by dehydrating the vitreous due to the osmotic gradient, a low plasma osmolality may have the opposite effect hydrating the vitreous and may also lead to fluid migration to the extracellular suprachoroidal space. This choroidal expansion may worsen the angle closure in eyes with crowded anterior chambers. The axial length was relatively short in our patient. Hence, it is likely that bilateral angle closure in our patient had a multifactorial etiology. Prompt treatment with both systemic and topical medications reduced the IOP significantly, giving us time to execute an uneventful cataract extraction. She had good visual recovery with minimal disc damage and IOP well controlled with two medications. Her infectious state at the presentation precluded the performance of investigations such as ultrasound biomicroscopy. Laser iridotomy was deliberately avoided. This limits our ability to decipher the cause of the acute bilateral angle-closure attack. Bilateral angle closure can occur in coronavirus infection probably due to a multifactorial etiology. Prompt diagnosis and appropriate management can limit the morbidity from this potentially blinding ocular emergency.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Sen M, Honavar SG, Sharma N, Sachdev MS. COVID-19 and eye: A review of ophthalmic manifestations of COVID-19. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2021;69:488–509. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_297_21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lachkar Y, Bouassida W. Drug-induced acute angle closure glaucoma. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2007;18:129–33. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e32808738d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lai JS, Gangwani RA. Medication-induced acute angle closure attack. Hong Kong Med J. 2012;18:139–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yan Y, Diao B, Liu Y, Zhang W, Wang G, Chen X. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 nucleocapsid protein in the ocular tissues of a patient previously infected with coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2020;138:1201–4. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2020.3962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murray CJ. COVID-19 will continue but the end of the pandemic is near. Lancet. 2022;399:417–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00100-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yousaf Z, Al-Shokri SD, Al-Soub H, Mohamed MF. COVID-19-associated Siadh: A clue in the times of pandemic! Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2020;318:E882–5. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00178.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krawitz BD, Sirinek P, Doobin D, Nanda T, Ghiassi M, Horowitz JD, et al. The challenge of managing bilateral acute angle-closure glaucoma in the presence of active SARS-CoV-2 infection. J Glaucoma. 2021;30:e50–3. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0000000000001763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]