Abstract

Colorectal cancer is the third most common cancer among men and the second among women. In the United States alone, there are 150,000 cases diagnosed each year. Colonoscopy remains the best method for identifying, evaluating, and intervening on patients with precancerous lesions. Multiple guidelines and techniques are available to assist the endoscopist with accurate diagnosis of these lesions. These include the Paris, Narrow-Band Imaging (NBI) International Colorectal Endoscopic (NICE), Japan NBI Expert Team (JNET), Kudo, Hiroshima, and Shudo classifications which utilize techniques such as chromoendoscopy, narrow-band imaging, and endocytoscopy to evaluate pit pattern and surface morphology. Utilization of these tools can help the endoscopist predict the cytology of a colonic lesion and select the most appropriate method for resection while maximizing organ preservation.

Keywords: endoscopy, classification, techniques, colon, polyp

Colorectal cancer is one of the most common cancers encountered in the world. In the United States there are 150,000 cases of colorectal cancer diagnosed a year with around 100,000 of those being colon and 50,000 rectal cancers. 1 Colorectal cancer is becoming more common among patients under the age of 50. The incidence was noted to decrease by 3.3% annually for individuals aged 65 and older from 2011 to 2016 and inversely increased by 2% for those 50 years and under. 2 As a result, the United States Preventive Services Task Force and American Cancer Society have both recommended screening starting at age 45. Common altered genetic pathways in colorectal cancer are the WNT, MAPK, PI3K, TGF-B, and p53. APC, a tumor suppressor, is the most common gene mutated in colorectal cancer making up approximately 72% of cancers. Around half of colorectal cancers involve mutations in RAS (KRAS/NRAS); these cancers have worse response to antiepidermal growth factor receptor agents. Another is the epithelial to mesenchymal transition pathway which allows the cells to develop an ability to change their architecture and become invasive. Most tumors have multiple mutations and knowing the different genetic mutations associated with these lesions can help guide treatment and predict outcomes. 3 Colorectal cancer most often develops from the adenoma-carcinoma genetic sequence. Because of this, studies have shown that the use of colonoscopy with removal of adenomas can reduce the incidence of colorectal cancer and death from colorectal cancer by 40 to 60%. 4

Predicting Cancer Risk

When performing endoscopic procedures, a clear understanding of which polyps have a high risk of submucosal invasion allows clinicians to select the appropriate method for resection and improve patient care.

There are several features of polyps that can be used to predict risk of submucosal invasion. Polyp size is a known risk factor for submucosal invasion. Both pedunculated and sessile polyps have a progressive increase in risk of harboring submucosal invasion with increasing size. In a study by Dr. Kudo, both pedunculated and sessile polyps 5 mm or less have shown 0% having carcinoma in 5,400 polyps examined. At 11 to 15 mm, 8% harbored submucosal invasion and at 21 mm or more nearly 30% of the polyps of that size were noted to have submucosal invasion. 5 Other studies have found that polyps > 25 mm in size carried a risk of around 40% for harboring malignancy, 5 6 and that polyps > 10 mm in size had a hazard ratio of 3.11 for having submucosal invasion. 7

The morphology of the lesion in question is also a predictive risk factor for submucosal invasion. Polypoid lesions have a lower risk of submucosal invasion when compared with excavated lesions. A study evaluating 321 adenomas found polypoid lesions <5 mm in size carried near 0% risk of submucosal invasion, whereas lesions that were excavated and >15 mm had nearly a 90% risk of submucosal invasion. 3

Finally, laterally spreading tumors are lesions that are superficial nonpolypoid lesions measuring >10 mm. These can be classified as either granular or nongranular with the former being subclassified as homogenous or mixed. Superficial spreading granular lesions that are homogenous have a low risk of submucosal invasion with granular of higher risk and the nongranular type with the highest risk of submucosal invasion. 3

Other characteristics that can be utilized to assess risk for a colonic lesion include color of the lesion, surface pit pattern, vascular morphology, and cell matrices. This will be further discussed in the coming sections.

Paris Classification

The Paris classification is a standardized morphologic classification that was developed by a team gathered in Paris to discuss superficial neoplastic lesions of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. There are six subtypes that were based on endoscopic appearance from the Japanese-Borrmann classification as follows:

Type 0: superficial polypoid, flat or depressed, or excavated tumors.

Type 1: polypoid carcinomas typically on a wide base.

Type 2: ulcerated carcinomas with sharply demarcated borders and raised margins.

Type 3: ulcerated, infiltrating carcinomas without defined limits.

Type 4: nonulcerated and diffusely infiltrating carcinomas.

Type 5: unclassifiable advanced carcinomas. 4

Superficial lesions (type 0) are lesions that by appearance do not have a depth of penetration further than the submucosa; they are split between the polypoid and nonpolypoid lesions. Polypoid lesions protrude above the surrounding surface. Polypoid can be classified as type 0-Ip or type 0-Is. Type 0-Ip is a protruded and pedunculated lesion which has a height greater than twice the thickness of the adjacent mucosa and a base that is narrower than the top. Type 0-Is is a sessile polyp in which the base and top of the lesion have the same diameter. The nonpolypoid lesions are classified under four subtypes. The flat lesions are grouped into three of those subtypes with ulcerated lesions making up the fourth. Type 0-IIa lesion is a superficial elevated lesion that has a slight elevation above the surrounding mucosa; however, is not greater than twice the thickness of the surrounding mucosa. Type 0-IIb describes a flat lesion that is even in height with the surrounding mucosa. Type 0-IIc is a flat lesion that is lightly sunken in from the surrounding mucosa without signs of ulceration. The last nonpolypoid lesion is type 0-III which describes an excavated or ulcerated lesion. Polyps can also fall under a mixed type, which has characteristics of two of the subtypes. For example, a 0-IIa + IIc is an elevated lesion with a central depression. One of the methods described for assisting with the classification of these lesions is using a closed biopsy forceps measuring 2.5 mm in height. If the lesion is of a greater height than the closed forceps tip then it falls under the classification of 0-Ip or Is. If less than the height of the forceps tip then it falls under 0-IIa, IIb, IIc, or III pending on if it is ulcerated or not. 5

The distribution of the lesions found in the colon has been studied under this classification system in 3,680 polyps. Type 0-I lesions make up around 50% of the lesions found with pedunculated (0-Ip) amounting to nearly 75% of those lesions. Types 0-IIa and IIb are the next most frequent lesion at 44%; type IIa lesions make up the vast majority of these (98%). Type IIc made up around 5% of the lesions with many of the IIc lesions being of a mixed type. In these data there were no 0-III lesions. 5

The depth of invasion into the submucosa can be estimated by the diameter of the lesion as well as its subtype. A study by the Red Cross Hospital in Akita and Showa Norther Hospital in Yokohama from 1985 to 2003 showed size directly correlated to submucosal invasion in each lesion subtype. Type 0-I lesions had 0% submucosal invasion in lesions 5 mm or less, and 30% submucosal invasion in lesions 21 mm or greater. Type 0-IIa/b also showed a similar result with <0.1% submucosal invasion at 5 mm or less and 23% submucosal invasion at 21 mm or larger. Unsurprisingly, 0-IIc lesions showed higher rates of submucosal invasion in smaller lesions with 7% at 5 mm or less, 44% at 6 to 10 mm, 67% at 11 to 15 mm, 90% at 16 to 20 mm, and 87% at 21 mm or more. Again, in this study there were zero type 0-III lesions. 5

High-Definition Endoscopy

High-definition white-light endoscopy (HD-WLE) allows a resolution of over 1 million pixels, compared with standard definition (SD), which has an image resolution of around 400,000 pixels. 8 Multiple studies have been performed evaluating the use of HD-WLE compared with SD-WLE. One study comparing Olympus 190C HD to Olympus 160C SD found a significant decrease in adenoma miss rates from 30.2 to 16.6%. In addition, they also found an increase in adenoma detection rate of 43.8% versus 36.5%. 9 This advancement in technology has also provided a closer look at colonic lesions, and has opened new doors for differentiating these lesions. Previously, gross morphology had to be used under systems such as the Paris classification; however, now we can look at lesions in a new light classifying them using pit patterns, vascular morphology, and even cellular matrices as described in the following sections.

Narrow-Band Imaging

Narrow-band imaging (NBI) uses blue light optical imaging. This light format helps to visualize mucosal detail, vascular structures, and microvascular density. NBI assists the endoscopist in two main ways: (1) light does not penetrate as deeply through the mucosa and provides a better superficial detail of mucosal structures and (2) the hemoglobin within superficial capillaries absorb the light resulting in better visualization of the capillaries. This technique has been helpful in differentiating nonadenomatous polyps (commonly hyperplastic) from adenomas. Nonadenomatous polyps are more likely to have a “light” vascular color index than adenomas (71% for nonadenomatous vs. 29% for adenomas). In the same study, endoscopists receiving training were able to accurately differentiate between adenomatous and nonadenomatous lesions 87% of the time using NBI versus 77% with WLE. 10 A systematic review and meta-analysis found the sensitivity of NBI for diagnosis of these lesions was 91% and specificity was 83%. 11 This has led some researchers to recommend a “resect and discard” strategy for hyperplastic polyps identified using NBI, where these polyps would be removed but not sent for pathology. This remains controversial because studies to date have not shown that NBI-assisted optical diagnosis can achieve a 95% sensitivity for detecting adenomatous polyps. 12

Kudo's Classification

The Kudo classification was developed and published in 1994 to better associate lesion pit patterns and histology. They used a magnifying endoscope with a zoom range of 1 to 100 magnification and contrast to better visualize the pits. They then developed a series of pit patterns that were correlated with histopathology. Of 4,329 patients who underwent removal of a polyp, 1,413 underwent endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) and 237 had surgical resection. 13

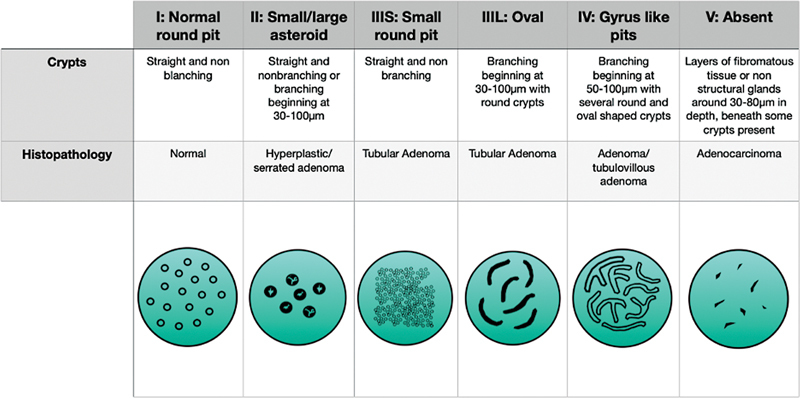

In the study, they describe seven pit patterns: (1) normal round pit, (2) small round pit, (3) small asteroid, (4) large asteroid, (5) oval, (6) gyrus-like pits, and (7) absent. Normal round pit polyps were histopathologically normal in 100% of the samples obtained. Small round pit pattern showed 72% were borderline malignant lesions and 28% were adenocarcinoma. They further described the lesions as being more often depressed lesions than protruding ones. Small asteroid pit pattern polyps were hyperplastic in 100% of the lesions. Large asteroid pit pattern were hyperplastic lesions or serrated adenoma after histologic review. Oval pit pattern were diagnosed as adenomas in 100% of the samples. On a macroscopic level they were more often protruding lesions than depressed lesions. Gyrus-like pit pattern were diagnosed as adenomas in 100% of the lesions. Furthermore, they were almost all tubulovillous adenomas and were also more often protruding lesions. Nonpit pattern polyps were further separated into three subtypes of straight, nonbranching, and branching crypts. In this pit pattern group the pathology resulted as malignant cells and were adenocarcinoma in 100%. Based on these results, Kudo et al created the classification of type I (normal round pit), type II (a combination of small and large asteroid pits), type IIIS (small round pit), type IIIL (oval pit), type IV (gyrus pit), and type V (nonpit pattern). 13

Studies have been performed to look at this method of classification outside of Kudo and his group. A study by Tanaka et al looked at 457 colorectal adenomas and early carcinomas. They used the classification system designed by Kudo with the split of group V into Va and Vn. Group Va involved irregular arrangement and sizes of IIIL, IIIS, and IV patterns and group Vn was the amorphous or nonstructural pit pattern ( Fig. 1 ). They found the rates of submucosal invasion with each pattern to be 1% for IIIL, 5% for IIIS, 8% for IV, 14% for Va, and 80% for Vn. They also evaluated the rates of submucosal invasion > 400 µm with each pattern and found them to be 0% for IIIL, 0% for IIIs, 4% for IV, 5% for Va, and 72% for Vn. They found higher rates of submucosal invasion in depressed-type lesions of Paris IIc. They further compared the two higher groups of Va and Vn on their rates of depth > 1,500 µm, and found 0% of the Va group had an invasive depth greater than that and 67% of the Vn group did. These results further support the use of evaluation of pit patterns as a useful tool for identifying malignant lesions. 14

Fig. 1.

The Kudo classification system.

Narrow-Band Imaging International Colorectal Endoscopic Classification

The NBI International Colorectal Endoscopic (NICE) classification was developed to make a practical, simple, and internationally applicable classification for determination of colorectal polyp histology using NBI. NICE was also developed with the idea that magnification imaging is not always readily available, so they hoped to develop a system that could be utilized without magnification. It was developed using the color, vessels, and surface patterns of polyps to classify endoscopic findings without optical magnification.

Type 1: lesions are the same or lighter in color than the background mucosa, vessels are not seen or isolated lacy vessels may be present, and the surface pattern is dark or white spots of uniform size or homogeneous absence of pattern. Type 1 lesions are hyperplastic.

Type 2: lesions are a darker brown relative to the background, vessels are seen surrounding the white structures, and then have oval, tubular, or branched white structures surrounded by brown vessels for the pattern. These lesions are adenomatous polyps.

Type 3: lesions are also brown to dark brown relative to the background and can sometimes have patchy whiter areas. The vessels have areas of disrupted or missing vessels and the surface pattern is amorphous or has an absent surface pattern. Type 3 lesions are suggestive of deep submucosal invasion. 15

Studies have looked at using this classification system and comparing its use to histologic evaluation. A study by Hamada et al used experienced endoscopists to evaluate polyps using the NICE criteria and found the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), and accuracy for each type to be: 86.0, 99.6, 94.9, 98.8, and 98.5% for NICE type 1; 99.2, 85.2, 98.3, 92.0, and 97.8% for NICE type 2; and 81.8, 99.6, 81.8, 99.6, and 99.3% for NICE type 3. 15 Wang et al also showed similar results using experienced endoscopists with findings of 84.6, 94.9, and 93.9% in type 1, 91.4, 86.3, and 90.7% in type 2, and 91.7, 97.0, and 96.8% in type 3 for sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy, respectively. 16 Another study looked at the utility of the NICE classification with a range of medical experience from medical students to GI fellows. They found endoscopically naive individuals were able to use the criteria with a kappa value of 0.67, 0.60, and 0.48 for vessels, surface pattern, and color. The GI fellows were able to significantly better perform with values of 0.72, 0.75, and 0.68, respectively. 17 This supports the view that with further experience the utility of the NICE criteria improves.

Japan Narrow-Band Imaging Expert Team Classification

The Japan NBI Expert Team (JNET classification) was created by a team of 38 members in Japan to help establish a universal NBI magnifying endoscopic classification of colorectal tumors. The issues the JNET team saw that needed to be corrected was the existence of multiple terms for the same magnifying findings, necessity of including surface patterns in magnifying endoscopic classifications, and differences in the NBI magnifying findings in elevated and superficial lesions. 18 In this classification system type 1 lesions are hyperplastic lesions/sessile serrated polyps, type 2A are low-grade intramucosal neoplasia including intramucosal cancer with low-grade structural atypia, type 2B are high-grade intramucosal neoplasia/shallow submucosal invasive cancer, and type 3 included deep submucosal invasive cancers. In the JNET classification, lesions are grouped into the different types based on vessel pattern and surface pattern using NBI. Type 1 involved an invisible vessel pattern and regular dark or white spots or similar to surrounding normal mucosa. Type 2A lesions had regular caliber vessels and regular distribution, and the surface pattern was regular with tubular/branched/papillary pattern. Type 2B involved variable caliber vessels and irregular distribution, and the surface pattern was irregular or obscure. Lastly, type 3 had loose vessel areas and interrupted thick vessels, and the surface pattern involved amorphous areas. 18

A study of 1,402 lesions was evaluated using the JNET classification by Kobayashi et al. From this evaluation they retrospectively compared the JNET classification of each lesion with the final histological pathology. Findings ultimately were favorable for the JNET classification with sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, and accuracy for each JNET classification as: type 1, 75, 96, 74, 96, and 93%; type 2a, 91, 70, 92, 67, and 87%; type 2b, 42, 95, 26, 98, and 93%; and type 3, 35, 100, 93, 98, and 98%. From these data JNET 2b had the lowest sensitivity likely secondary to it being classified as having both high-grade intramucosal neoplasia and shallow submucosal invasive cancer. To better differentiate this, pit pattern evaluation can be used to make a better assessment. Type 3 lesions were found to have a high specificity of 100% to help with diagnosis for endoscopists. 19

Endocytoscopy

Endocytoscopy is a method of obtaining a high-resolution magnified image of lesions that allows visualization of cellular structures to obtain the so-called “virtual histology” or “optical biopsy” of a lesion in question. This technique is able to evaluate cellular matrices, nuclei, and vasculature through the use of stains at the time of the colonoscopy. The endocytoscope is also able to magnify images up to 380× to 520 × . 14 20 21 22

To perform this method the endoscopist will often stain the lesion first, commonly with crystal violet and methylene blue. Once the lesion is stained, the scope tip is applied to the target lesion and a magnified image is obtained. Classification systems have been developed similar to the pit pattern classifications. 14 Kudo et al describe a system in a paper published by his team in 2011. This system classified normal mucosa as EC1a, hyperplastic as EC1b, dysplasia as EC2, and invasive submucosal cancers as EC3b. In this review of 213 specimens collected and classified, they found they could differentiate nonneoplastic and neoplastic with 100% sensitivity and specificity. They further describe that with 90.1% sensitivity and 99.2% specificity, this method is able to differentiate between submucosal cancers and other neoplastic lesions. 21

To further assist with differentiation of lesions by endocytoscopy, computer-aided systems have been developed to evaluate patterns and develop predictions concerning the lesions. One of these programs was described by Takeda et al. 22 An endocytoscopy-computer-aided design was used and evaluated 296 features from the imaging (8 from the nuclei and 288 from texture analysis) to further categorize the lesions as nonneoplastic, adenoma, and submucosal invasive cancer. A total of 188 images were evaluated and they found the sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, PPV, and NPV to be 89.4, 98.9, 94.1, 98.8, and 90.1% respectively. 23 This further supports that endocytoscopy and computer learned programs can help predict nonneoplastic from neoplastic colonic lesions.

Computer-aided programs are being developed to help the endoscopist with classifying and differentiating lesions based on a computer learned recognition software. Another study performed by Spadaccini et al conducted a meta-analysis to compare computer-aided programs to standard HD-WLE in adenoma detection rates. They found that the computer-aided programs' adenoma detection rate was 7.4% higher than using HD-WLE. 24 Computer-aided programs are relatively rare and are not a widely available option.

Conclusion

Colonoscopy is a valuable tool for screening and identifying colonic lesions. Multiple tools are available to differentiate lesions that are at high or low risk for submucosal invasion. This information is critical to select the best modality for resection, which may include polypectomy, EMR, endoscopic submucosal dissection, or surgical segmental resection with lymphadenectomy. These techniques will be discussed in further detail in the following chapters.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest None declared.

References

- 1.Siegel R L, Miller K D, Fuchs H E, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin. 2022;72(01):7–33. doi: 10.3322/caac.21708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel R L, Miller K D, Goding Sauer A et al. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70(03):145–164. doi: 10.3322/caac.21601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steele S, Hull T L, Hyman N, Maykel J A, Read T E, Whitlow C B. Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2022; 2022. The Ascrs Textbook of Colon and Rectal Surgery. 4th ed. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brenner H, Stock C, Hoffmeister M. Effect of screening sigmoidoscopy and screening colonoscopy on colorectal cancer incidence and mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials and observational studies. BMJ. 2014;348:g2467. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g2467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.The Paris endoscopic classification of superficial neoplastic lesions: esophagus, stomach, and colon: November 30 to December 1, 2002 Gastrointest Endosc 200358(6, suppl):S3–S43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland . Williams J G, Pullan R D, Hill J et al. Management of the malignant colorectal polyp: ACPGBI position statement. Colorectal Dis. 2013;15 02:1–38. doi: 10.1111/codi.12262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Halfter K, Bauerfeind L, Schlesinger-Raab A et al. Colonoscopy and polypectomy: beside age, size of polyps main factor for long-term risk of colorectal cancer in a screening population. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2021;147(09):2645–2658. doi: 10.1007/s00432-021-03532-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sami S S, Subramanian V, Butt W M et al. High definition versus standard definition white light endoscopy for detecting dysplasia in patients with Barrett's esophagus. Dis Esophagus. 2015;28(08):742–749. doi: 10.1111/dote.12283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zimmermann-Fraedrich K, Groth S, Sehner S et al. Effects of two instrument-generation changes on adenoma detection rate during screening colonoscopy: results from a prospective randomized comparative study. Endoscopy. 2018;50(09):878–885. doi: 10.1055/a-0607-2636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rogart J N, Jain D, Siddiqui U D et al. Narrow-band imaging without high magnification to differentiate polyps during real-time colonoscopy: improvement with experience. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68(06):1136–1145. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McGill S K, Evangelou E, Ioannidis J P, Soetikno R M, Kaltenbach T. Narrow band imaging to differentiate neoplastic and non-neoplastic colorectal polyps in real time: a meta-analysis of diagnostic operating characteristics. Gut. 2013;62(12):1704–1713. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-303965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rees C J, Rajasekhar P T, Wilson A et al. Narrow band imaging optical diagnosis of small colorectal polyps in routine clinical practice: the Detect Inspect Characterise Resect and Discard 2 (DISCARD 2) study. Gut. 2017;66(05):887–895. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kudo S, Hirota S, Nakajima T et al. Colorectal tumours and pit pattern. J Clin Pathol. 1994;47(10):880–885. doi: 10.1136/jcp.47.10.880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tanaka S, Haruma K, Nagata S, Oka S, Chayama K. Diagnosis of invasion depth in early colorectal carcinoma by pit pattern analysis with magnifying endoscopy. Dig Endosc. 2001;13:S2–S5. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hamada Y, Tanaka K, Katsurahara M et al. Utility of the narrow-band imaging international colorectal endoscopic classification for optical diagnosis of colorectal polyp histology in clinical practice: a retrospective study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2021;21(01):336. doi: 10.1186/s12876-021-01898-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang Y, Li W K, Wang Y D, Liu K L, Wu J. Diagnostic performance of narrow-band imaging international colorectal endoscopic and Japanese narrow-band imaging expert team classification systems for colorectal cancer and precancerous lesions. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2021;13(01):58–68. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v13.i1.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hewett D G, Kaltenbach T, Sano Y et al. Validation of a simple classification system for endoscopic diagnosis of small colorectal polyps using narrow-band imaging. Gastroenterology. 2012;143(03):599–6070. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sano Y, Tanaka S, Kudo S E et al. Narrow-band imaging (NBI) magnifying endoscopic classification of colorectal tumors proposed by the Japan NBI Expert Team. Dig Endosc. 2016;28(05):526–533. doi: 10.1111/den.12644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kobayashi S, Yamada M, Takamaru H et al. Diagnostic yield of the Japan NBI Expert Team (JNET) classification for endoscopic diagnosis of superficial colorectal neoplasms in a large-scale clinical practice database. United European Gastroenterol J. 2019;7(07):914–923. doi: 10.1177/2050640619845987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wada Y, Kudo S E, Kashida H et al. Diagnosis of colorectal lesions with the magnifying narrow-band imaging system. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70(03):522–531. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takamaru H, Wu S YS, Saito Y. Endocytoscopy: technology and clinical application in the lower GI tract. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5:40. doi: 10.21037/tgh.2019.12.04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takeda K, Kudo S E, Mori Y, Misawa M, Kudo T, Wakamura K, Katagiri A, Baba T, Hidaka E, Ishida F, Inoue H, Oda M, Mori K. Accuracy of diagnosing invasive colorectal cancer using computer-aided endocytoscopy. Endoscopy. 2017;49(08):798–802. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-105486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abad M RA, Shimamura Y, Fujiyoshi Y, Seewald S, Inoue H. Endocytoscopy: technology and clinical application in upper gastrointestinal tract. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5:28. doi: 10.21037/tgh.2019.11.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spadaccini M, Iannone A, Maselli R et al. Computer-aided detection versus advanced imaging for detection of colorectal neoplasia: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;6(10):793–802. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(21)00215-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]