Abstract

Introduction

Segmental spinal deformity results from vertebral compression fracture (VCF) and progressive collapse of the fractured vertebral body (VB). The VB stenting (VBS) systemⓇ comprises a balloon-assisted, expandable, intrasomatic, metal stent that helps maintain the restored VB during balloon removal and cement injection, which minimizes cement leakage. We performed a prospective, multicenter, clinical trial of the VBS system in Japanese patients with acute VCF owing to primary osteoporosis.

Methods

Herein, 88 patients, 25 men and 63 women aged 77.4±8.3 years, with low back pain, numerical rating scale (NRS) score of ≥4, and mean VB compression percentage (VBCP) of <60% were enrolled. The primary endpoints were the VBCP restoration rate and reduction in low back pain 1 month and 7 days after VBS surgery, respectively. Secondary endpoints included changes in VBCP, NRS pain score, Beck index, kyphosis angle, and quality of life according to the short form 36 (v2) score. Safety was assessed as adverse events, device malfunctions, and new vertebral fractures.

Results

Overall, 70 patients completed the study. VBS surgery increased the restoration rates of anterior and midline VBCP by 31.7%±26.5% (lower 95% confidence intervals (CI): 26.8) and 31.8%±24.6% (lower 95% CI: 27.2), respectively, and the reduction in NRS pain score was −4.5±2.4 (upper 95% CI: −4.0). As these changes were greater than the predetermined primary endpoint values (20% for VBCP and −2 for NRS score), they were judged clinically significant; these changes were maintained throughout the 12-month follow-up (p<0.001). Likewise, significant improvement was observed in the Beck index, kyphosis angle, and quality of life score, which were maintained throughout the follow-up. There were three serious adverse events. New fractures occurred in 12 patients-all in the adjacent VB.

Conclusions

VBS surgery effectively restored the collapsed VB, relieved low back pain, and was tolerable in patients with acute osteoporotic VB fracture.

Keywords: clinical study, low back pain, primary osteoporosis, vertebral body compression percentage, vertebral body stenting, vertebral fracture

Introduction

Vertebral compression fractures (VCFs) are the most common complication of osteoporosis1), causing pain, and, in several cases, progressive collapse of the fractured vertebral body (VB), leading to segmental spinal deformity2). VCF-induced spinal deformity worsens a patient's quality of life (QOL), physical function, mental health, and survival3,4). As conservative therapy cannot restore the fractured VB height (VBH) and relieve pain, vertebroplasty was introduced in 19875). Although this approach provided pain relief, it did not restore VBH6,7), and there is a risk of cement leaks beyond the confines of the bone6,7). These problems prompted the development of balloon kyphoplasty (BKP)8), which involves the inflation of a balloon catheter inside the collapsed VB to restore VBH and create a cavity into which bone cement can be injected to stabilize the restored VB. As more viscous cement and lower injection pressures are used, BKP is anticipated to reduce cement leakage9,10). Unfortunately, the recovery of VBH can be partially lost with BKP after deflation and balloon removal11,12). To circumvent this problem, a VB stenting (VBS) system has been developed13,14). This system comprises an expandable metal device for percutaneous vertebral augmentation. Moreover, the system employs a balloon that when inflated enables the stent to expand by up to 400%. This restores the VB and creates a cavity that remains stable even after deflation and balloon removal. Furthermore, VBH can be restored by injecting highly viscous bone cement into the cavity. This system has been proven to provide increased restoration of VBH and relieve pain with less cement leakage compared with BKP15,16). This study was conducted to clarify whether the VBS system can restore the collapsed VBH and relieve low back pain in Japanese patients with acute VCF owing to primary osteoporosis and to obtain approval for the application of the VBS system from the regulatory authority in Japan.

Materials and Methods

Study devices

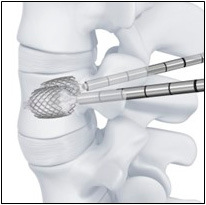

The VBS system (Synthes GmbH, Oberdorf, Switzerland) evaluated herein comprises two parts, i.e., one is an expandable (by inflating a balloon), intrasomatic, cobalt-chromium alloy device and the other is for injection of bone cement (polymethylmethacrylate; PMMA)17). With VBS, the stent remains within the newly created vertebral cavity, and the balloon can be removed after deflation while preventing the VB from collapsing. In the ideal scenario, a virtually physiological VBH and shape can be restored and preserved (Fig. 1). The cavity is then filled with PMMA.

Figure 1.

Vertebral body stenting system.

Study design

This was a prospective, multicenter, single-arm study involving patients with acute osteoporotic VCF. The effectiveness of the VBS system was evaluated based on the VBS-induced restoration rate of the injury-caused loss of the target VBH and improvement in low back pain. The safety of the VBS system was evaluated based on reports of adverse events (AEs), device malfunctions, and the presence or absence of new fractures on radiography. The study was registered at the UMIN Clinical Trials Registry, and the Japanese regulatory authority approved the VBS system.

Participants

The study participants were Japanese men and women aged ≥40 years with magnetic resonance imaging-confirmed acute VCF due to primary osteoporosis who provided written informed consent.

Inclusion criteria

Patients who met all of the following inclusion criteria were enrolled in the study: bone mineral density of the lumbar spine by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry <80% that of the mean for young adults or bone atrophy≥ grade 1 assessed on the lateral X-ray view and painful acute VCF in one thoracic or lumbar vertebra from the fifth thoracic vertebra (T5) to the fifth lumbar vertebra (L5) and anterior VBH (AVBH) or midline VBH (MVBH) of the fractured VB ≤80% of the mean of the AVBH or MVBH of the most proximal nonfractured VB above and below the fractured VB. When the fractured VB was L5, the required VBH was ≤80% of the most proximal unfractured VB above the fractured VB. Additional inclusion criteria were as follows: ≤2 fractured VBs other than the target VB, persistent low back pain for 3 months despite conservative therapy or intolerance to conservative therapy, pain with a numerical rating scale (NRS) score≥ 4 at screening, and eligibility judged by the principal investigator or subinvestigator.

Exclusion criteria

Patients who met any of the following conditions were excluded: previous spine surgery; vertebral fractures that technically preclude VBS surgery (i.e., fracture of a pedicle or the posterior wall of the VB); low back pain due to causes other than primary osteoporosis; pre-existing VCF-unrelated neurological abnormality or radiculopathy or neurological symptoms due to spinal complications; hemorrhagic diathesis or anticoagulant therapy; systemic infection or local infection of the fractured VB; unfit for general anesthesia; hypersensitivity to bone cement (PMMA), imaging agents, or cobalt-chromium alloy; and contraindicated for magnetic resonance imaging (Table 1).

Table 1.

Criteria for Enrollment.

| Inclusion criteria | |

| Criteria | |

| 1 | Bone density of the lumbar spine (L2–L4) measured using DEXA was <80% of the young adult mean or bone atrophy was assessed as Grade 1 or higher on lateral radiographs, and there was a painful acute compression fracture of one thoracic or lumbar vertebra (T5–L5). To confirm that all acute fractures were fresh fractures before enrollment, MRI was performed. |

| 2 | Vertebral height measured at the anterior border or the central part of the indicated vertebral body was decreased to 80% or lower of the mean of the most proximal normal (unfractured) vertebral bodies above and below the indicated vertebral body. Nevertheless, if the indicated vertebral body was the fifth lumbar vertebra (L5), the vertebral height measured at the anterior border or the central part of the indicated vertebral body had to be decreased to 80% or lower of the most proximal normal (unfractured) vertebral body above the indicated vertebral body. |

| 3 | No more than two fractured vertebral bodies other than the indicated vertebral body. |

| 4 | Low back pain was not relieved despite 3 months (12 weeks) of conservative therapy after onset (including patients for whom low back pain continued for at least 3 months [12 weeks] without treatment). The following patients who did not respond to conservative therapy were considered eligible even if the onset was within 3 months (12 weeks): |

| a) Patients for whom conservative therapy could not be continued due to the pain that was not reduced by maximum medication (NRS ≥ 4). | |

| b) Patients for whom back bracing could not be continued. | |

| c) Patients who could not tolerate or had adverse reactions to analgesic medications. | |

| 5 | NRS pain score of ≥4 for low back pain at screening. |

| 6 | Either gender. |

| 7 | Age ≥40 years and provision of written informed consent. |

| 8 | Treatment with SJ-11001-A and SJ-11001-B was deemed possible by the primary investigator/subinvestigator. |

| Exclusion criteria (patients meeting any of the following conditions were excluded) | |

| 1 | Previous spinal surgery |

| 2 | Difficulty using SJ-11001-A and SJ-11001-B due to the status of the spinal fracture (e.g., the upper endplate of the indicated vertebral body was located below the pedicle). |

| 3 | Pedicle fracture of the indicated vertebral body. |

| 4 | Fracture of the posterior wall of the indicated vertebral body confirmed by X-ray, CT, or MRI. |

| 5 | Pre-existing (but unrelated to the fracture of the indicated vertebral body) abnormal neurological findings or radiculopathy with unstable symptoms. |

| 6 | Low back pain that was difficult to resolve due to causes other than the target disease. |

| 7 | Spinal fracture due to vertebral or spinal neoplastic disease or multiple myeloma. |

| 8 | Spinal fracture due to secondary osteoporosis. |

| 9 | Inability to withdraw anticoagulant therapy. |

| 10 | Systemic infection, local infection of a fractured vertebral body, or hemorrhagic diathesis. |

| 11 | Inability to tolerate general anesthesia. |

| 12 | History of hypersensitivity to bone cement (PMMA) or contrast agents. |

| 13 | Inability to complete a QOL survey due to dementia or other disorders. |

| 14 | Inability to walk or stand before the injury occurred (walking with assistance was permitted). |

| 15 | Contraindications to MRI. |

| 16 | Pregnancy or planning to become pregnant during the study period. |

| 17 | Current participation in another clinical trial or participation in another clinical trial in the past 3 months. |

| 18 | Contraindications to spinal reconstruction with internal fixation. |

| 19 | Known hypersensitivity to cobalt–chromium alloys. |

| 20 | Study participation deemed inappropriate by the primary investigator/subinvestigator. |

CI, confidence interval; CT, computed tomography; DEXA, dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry; L, lumbar vertebra; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NRS, numerical rating scale; QOL, quality of life; T, thoracic vertebra; VB, vertebral body; vertebral body stenting

Conservative therapy

The analgesics comprise nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) at less than or equal to the maximum daily dose for each drug, depending on patient response and tolerability.

Efficacy assessment

Primary endpoints

The primary endpoints included (1) restoration rate of the fractured VBH 1 month after VBS surgery compared with presurgery using standing or sitting X-ray images and (2) changes in the degree of low back pain assessed by the NRS pain scores from screening to 7 days after VBS surgery.

Secondary endpoints

Changes in VBH before and 1, 3, 6, and 12 months after VBS surgery. We evaluated changes in the collapse rate (compression rate), restoration rate, and Beck index. Moreover, perioperative changes in the VBH during VBS surgery were assessed at VBS implantation, after removal of the deflated balloon, and after bone cement filling. The following parameters and their changes before and 1, 3, 6, and 12 months after VBS surgery were also evaluated: local kyphosis angle (Cobb angle) on lateral X-ray images, QOL according to the short form 36 (v2) score, low back pain according to the NRS pain score, NSAID dosage, and duration of hospitalization (from the date of surgery to the date of discharge). Specialists independent of those participating in collecting the radiographic data evaluated the X-ray images.

Safety assessment

AEs and malfunctions of the VBS devices were evaluated from the date of written consent to the completion of the study on the basis of the patients' reports, irrespective of causality related to the study device. Using the medical dictionary (version 17.1) for regulatory activities, the AEs were coded.

Statistical analyses

Summary statistics and one-sided 95% CIs were calculated to evaluate efficacy. Regarding the primary endpoint, the restoration rate of the fractured VBH was calculated using the following equation: ([fractured VBH postsurgery]−[fractured VBH presurgery])/([reference VBH]−[fractured VBH presurgery])×100%. According to previous studies18,19), we estimated VBS surgery-induced changes (mean±standard deviation) in the target VBH as 34%±47%. Considering a clinically significant rate change of 20% and assuming a one-sided type I error rate of 0.05, these observations indicate that the required number of participants was 72. The other primary endpoint, changes in the NRS low back pain score from presurgery to 7 days postsurgery, was evaluated using the estimated number of participants (72). Assuming an NRS pain score change of 3.5±2.0, a clinically significant rate of change of 2.0, and a type I error rate of 0.05, the sample size of 72 patients provided a statistical power of 0.99 for the NRS pain score. Given a dropout rate of 10% with BKP 7 days after surgery, we set the number of patients at 80. Nevertheless, 1 month after VBS surgery, we found that 10 of 60 patients had missing data for the other primary endpoint; thus, the final number of patients enrolled was set at 87. For the secondary endpoints, the collapse rate of the fractured VB was calculated as follows: (AVBH/posterior VBH)×100% for AVBH and (MVBH/posterior VBH)×100% for MVBH. To analyze the changes in the NRS pain score, the short form 36 (v2) score and one-sample t-test were employed. Using Wilcoxon's test, changes in the NSAID dosage to treat low back pain from screening to each postoperative time point were analyzed. The incidences of AEs and device malfunctions were estimated by type based on the rate of occurrence (%) and 95% CI. The number of new fractures and the rate of occurrence was tabulated by evaluation time point, site, and patient.

This study was conducted based on the principles of the Helsinki Declaration and in compliance with the Pharmaceutical Affairs Law, Medical Device Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and the study protocol, which was reviewed and approved by the Review Board of each institution. All participants in this study provided written informed consent.

Results

Patients

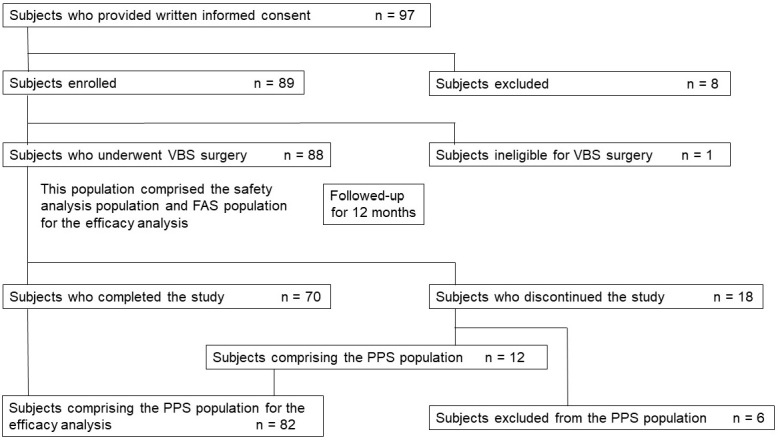

A total of 97 patients agreed to participate in the study, 89 of whom were enrolled in nine institutions (Fig. 2). Among the 89 enrolled patients, 88 underwent VBS surgery and 1 did not undergo surgery due to ineligibility after the start of the study. All 88 patients were included in the safety analysis population and encompassed the full analysis set population for the efficacy analysis. Among the 88 patients, 70 completed the study, and 18 discontinued the study because of accident or morbidity (three patients), new spinal compression fracture (13 patients), or difficulty to fully co-operate in the study (two patients). Among the 18 patients, 12 were included in the per protocol set (PPS) population for the efficacy evaluation besides the 70 patients who completed the study. The remaining six patients were excluded from the PPS population: five, due to significant violation of or deviation from the protocol and one, due to missing data for the primary endpoints. The full analysis set population was utilized as the primary target of analysis; nevertheless, the PPS population was also employed for the sensitivity analysis.

Figure 2.

Study flow chart.

PPS, per protocol set; FAS, full analysis set; VBS, vertebral stenting system

Demographic and other baseline characteristics

Table 2 summarizes the patients' background characteristics. The patients comprised 25 men and 63 women aged 77.4±8.3 years with a low VB compression percentage (VBCP) of the target VB for VBS. Among the 88 patients, 70 (79.5%) had an anterior vertebral body compression percentage (AVBCP) or posterior VBCP of <60%, and 60 patients (68.2%) had an midline vertebral body compression percentage (MVBCP) of <60%. Therefore, most of the patients were categorized as grade III based on the semiquantitative method20), indicating that most patients had severe compression fractures.

Table 2.

Subject Background.

| Item | Category | Number (%) or summary statistics | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subjects, n | 88 | ||

| Sex, n (%) | Male | 25 (28.4) | |

| Female | 63 (71.6) | ||

| Age, years old | <65 | 6 (6.8) | |

| 65 – 75 | 20 (22.7) | ||

| ≥75 | 62 (70.5) | ||

| Mean±SD | 77.4±8.3 | ||

| Minimum, median, and maximum | 51, 79.0, and 92 | ||

| Reasons to apply VBS, n (%) | Low back pain was not alleviated by conservative treatment for 3 months from onset | 40 (45.5) | |

| Conservative treatment discontinued | 48 (54.5) | ||

| (Duplicated tabulation) | Pain with score of ≥4 persisted despite the maximum dose of NSAID | 27 (56.3) | |

| Intolerable to conservative treatment (allergy or adverse events) | 13 (27.1) | ||

| Unable to continue external fixation of the trunk | 8 (16.7) | ||

| Days of conservative treatment | Mean±SD | 101.8±103.2 | |

| Minimum, median, and maximum | 5, 74.0, and 566 | ||

| Days from injury to VBS consent | Mean±SD | 98.2±99.7 | |

| Minimum, median, and maximum | 5, 74.0, and 566 | ||

| Bone densitometry (duplicated tabulation) | DEXA | 8 (9.1) | |

| Determination of the degree of bone atrophy using lateral radiography | 85 (96.6) | ||

| Bone density [g/cm2] (DEXA) | Mean±SD | 0.8640±0.1985 | |

| Bone atrophy [degree] (lateral radiograph) | Degree I | 21 (24.7) | |

| Degree II | 54 (63.5) | ||

| Degree III | 10 (11.8) | ||

| Posture of radiography (at screening) | Standing | 72 (81.8) | |

| Sitting | 16 (18.2) | ||

| Pre-existing fracture site (Duplicated tabulation) | T5 | 1 (1.1) | |

| T6 | 2 (2.3) | ||

| T7 | 3 (3.4) | ||

| T8 | 1 (1.1) | ||

| T9 | 1 (1.1) | ||

| T10 | 0 (0.0) | ||

| T11 | 6 (6.8) | ||

| T12 | 6 (6.8) | ||

| L1 | 5 (5.7) | ||

| L2 | 3 (3.4) | ||

| L3 | 5 (5.7) | ||

| L4 | 4 (4.5) | ||

| L5 | 2 (2.3) | ||

| Number of pre-existing fractures | 0 | 58 (65.9) | |

| 1 | 21 (23.9) | ||

| 2 | 9 (10.2) | ||

| VBS target sites | T10 | 2 (2.3) | |

| T11 | 6 (6.8) | ||

| T12 | 28 (31.8) | ||

| L1 | 27 (30.7) | ||

| L2 | 17 (19.3) | ||

| L3 | 5 (5.7) | ||

| L4 | 1 (1.1) | ||

| L5 | 2 (2.3) | ||

| NRS score (at screening) | Mean±SD | 6.7±1.8 | |

| Minimum, median, and maximum | 4, 7.0, 10 | ||

| Distribution of collapse rate immediately before VBS surgery in 88 patients | |||

| Vertebral body | Collapse rate | Number of subjects, n (%) | |

| Anterior VH/posterior VH | <20% | 8 (9.1) | 70 (79.5) |

| 20%≤<40% | 34 (38.6) | ||

| 40%≤<60% | 28 (31.8) | ||

| 60%≤<80% | 13 (14.8) | ||

| 80%≤ | 5 (5.7) | ||

| Midline VH/posterior VH | <20% | 0 (0.0) | 60 (68.2%) |

| 20%≤<40% | 12 (13.6) | ||

| 40%≤<60% | 48 (54.5) | ||

| 60%≤<80% | 23 (26.1) | ||

| 80%≤ | 5 (5.7) | ||

L. lumber vertebra; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; NRS, numerical rating scale; SD, standard deviation; VH, vertebral height; VBS, vertebral body stenting

Radiographical data

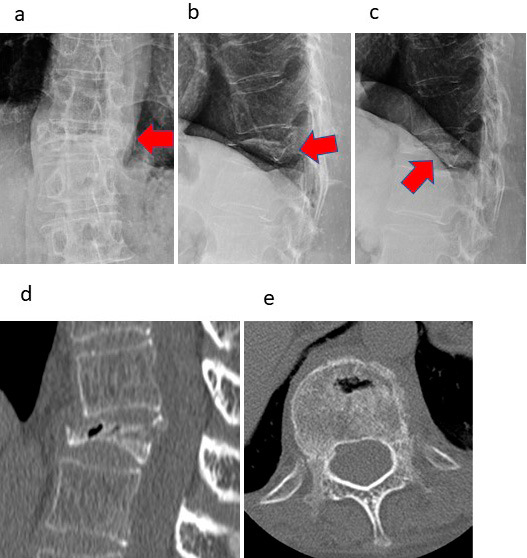

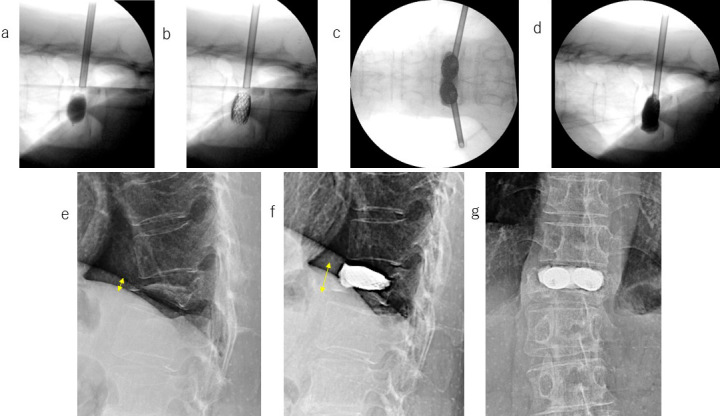

Fig. 3, 4 show the radiographical data of a typical patient (female, 65 years old) before and after VBS surgery. Even 4 months after the injury, the fractured T12 remained severely compressed (Fig. 3a), and the patient had persistent pain, with an NRS score of 6. The VB deformation was unchanged, even in the dorsal position (Fig. 3b and c). Computed tomography (CT) images indicated the rigid nature of the injured VB (Fig. 3d and e). During VBS surgery, inflation of the balloon dilated the compressed VB (Fig. 4a), which was maintained by the implanted stent (Fig. 4b) and followed by PMMA injection (Fig. 4c and d). One week after VBS surgery, the patient was pain free, and the restored VB was stable (Fig. 4e-g).

Figure 3.

Case presentation.

This 65-year-old female patient had a T12 fracture. Radiographs show that T12 remained severely compressed (a, b) even 4 months after the injury. Additionally, the patient had persistent pain, with an NRS score of 6. As the patient moved to the supine position, a small vacuum cleft sign became visible at the affected vertebra (c); nevertheless, dilation was poor. The red arrows indicate the severely fractured vertebra. These findings were also confirmed by CT (d, e). Radiographs: (a) frontal view, (b) lateral view, (c) lateral view (supine position) of the affected vertebra. CT images: (d) sagittal section, (e) transverse section.

T12, 12th thoracic vertebra; NRS, numerical rating scale; CT, computed tomography

Figure 4.

Case presentation (continued). Radiographs showing the compressed vertebral body before, during, and after VBS surgery.

When the stent was expanded by inflating the balloon, the compressed vertebral body was dilated (a), and the dilation was sustained after balloon removal (b) and PMMA injection (c, d). VBS surgery increased the severely compressed T12 body height (e) to a subnormal level (f, g). One week after the VBS surgery, the patient was pain-free. Radiographic findings: (a) fractured vertebral body expanded by balloon inflation; (b) maintenance of vertebral body height by the stent; (c) cement-injected vertebral body (frontal view); (d) cement-injected vertebral body (lateral view). The yellow arrows in images (e) and (f) indicate the collapsed and restored vertebral body height, respectively.

VBS, vertebral body stenting; T12, 12th thoracic vertebra; PMMA, polymethylmethacrylate

Primary endpoints

The restoration rate of VBCP 1 month after the surgery is summarized in Table 3. The restoration rate of the AVBCP and MVBCP were 31.7%±26.5% and 31.8%±24.6%, respectively. The lower 95% CIs for the restoration rates were 26.8% and 27.2%, respectively, surpassing the 20% value set for the endpoints and confirming that VBS surgery provided clinically significant benefits. The change in NRS pain score from screening to 7 days after VBS surgery was −4.5±2.4. The upper 95% CI of the mean value was −4.0, which was greater than the predefined value of −2.0 for efficacy, demonstrating clinically significant pain reduction.

Table 3.

Primary Endpoints.

| a. Restoration rate of vertebral height 1 month after VBS surgery | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vertebral body | Number | Restoration rate of vertebral height (%) | 95%CI (Lower) | |||||

| subjects | Mean | SD | Minimum | Median | Maximum | |||

| Anterior | 81 | 31.7 | 26.5 | −109.1 | 34.8 | 82.5 | 26.8 | |

| Midline | 78 | 31.8 | 24.6 | −77.2 | 33.0 | 97.9 | 27.2 | |

| b. Changes in the NRS pain score after VBS surgery | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time after VBS | Number of subjects | Changes in the NRS score after VBS surgery | 95%CI (upper) | One sample t-test | ||||||||

| Mean | SD | Minimum | Median | Maximum | ||||||||

| 7 days | 88 | −4.5 | 2.4 | −9 | −5.0 | 1 | −4.0 | p<0.001 | ||||

| 1 month | 86 | −5.2 | 2.3 | −10 | −5.0 | 2 | −4.7 | p<0.001 | ||||

| 3 months | 79 | −5.0 | 2.7 | −10 | −5.0 | 3 | −4.5 | p<0.001 | ||||

| 6 months | 75 | −5.2 | 2.5 | −10 | −5.0 | 1 | −4.7 | p<0.001 | ||||

| 12 months | 70 | −5.4 | 2.7 | −10 | −5.5 | 1 | −4.9 | p<0.001 | ||||

NRS, numerical rating scale; CI, confidence interval; VBS, vertebral body stenting; SD, standard deviation

Secondary endpoints

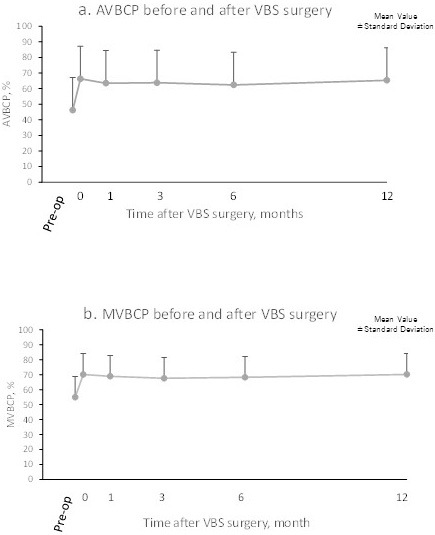

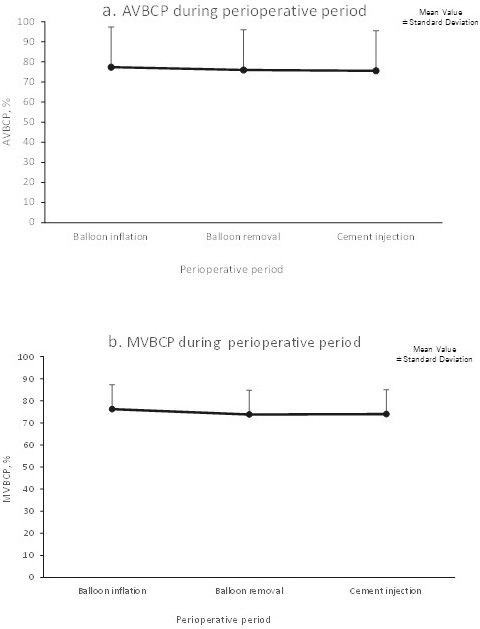

Fig. 5 shows the time course of changes in VBH before and after VBS surgery. Both AVBCP and MVBCP were significantly restored after surgery, and the results were maintained during the 12-month follow-up (p<0.001 at each postoperative time point). VBS-induced augmentation of the collapsed VBH was well maintained during the perioperative period (Fig. 6). The Beck index and kyphosis angle were also significantly enhanced via VBS surgery, and the results were maintained during the 12-month follow-up (Table 4). The patients' QOL also improved and was maintained throughout the follow-up (data not shown).

Figure 5.

VBS surgery resulted in sustained changes in the vertebral body compression percentages.

(a) AVBCP (anterior vertebral body compression percentage) and (b) MVBCP (midline vertebral body compression percentage). Each point and bar represents the mean and standard deviation.

VBS, vertebral body stenting; Pre-op, presurgery; 0, immediately postsurgery.

Figure 6.

Restored vertebral body height was maintained during the VBS surgery.

(a) AVBCP (anterior vertebral body compression percentage) and (b) MVBCP (midline vertebral body compression percentage). Each point and bar represents the mean and standard deviation.

VBS, vertebral body stenting; Pre-op, presurgery; 0, immediately postsurgery.

Table 4.

Amount of Changes in Beck Index and Kyphosis Angle (Cobb Angle) after VBS Surgery.

| a. Beck index | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time after VBS | Number of subjects | Changes in Beck index after VBS surgery | 95%CI (upper) | One sample t-test | ||||

| Mean | SD | Minimum | Median | Maximum | ||||

| Anterior/posterior | ||||||||

| Immediately | 87 | 0.210 | 0.142 | −0.04 | −0.210 | 0.58 | 0.185 | p<0.001 |

| 1 month | 85 | 0.177 | 0.153 | −0.15 | −0.160 | 0.67 | 0.149 | p<0.001 |

| 3 months | 77 | 0.173 | 0.161 | −0.24 | −0.140 | 0.57 | 0.142 | p<0.001 |

| 6 months | 73 | 0.158 | 0.165 | −0.18 | −0.140 | 0.53 | 0.126 | p<0.001 |

| 12 months | 69 | 0.177 | 0.171 | −0.21 | −0.160 | 0.62 | 0.143 | p<0.001 |

| Midline/posterior | ||||||||

| Immediately | 87 | 0.151 | 0.117 | −0.07 | 0.140 | 0.42 | 0.130 | p<0.001 |

| 1 month | 85 | 0.132 | 0.128 | −0.12 | 0.130 | 0.59 | 0.109 | p<0.001 |

| 3 months | 77 | 0.118 | 0.117 | −0.16 | 0.110 | 0.40 | 0.096 | p<0.001 |

| 6 months | 73 | 0.118 | 0.116 | −0.20 | 0.110 | 0.41 | 0.096 | p<0.001 |

| 12 months | 69 | 0.134 | 0.122 | −0.12 | 0.130 | 0.44 | 0.110 | p<0.001 |

| b. Change in the kyphosis angle (Cobb angle) after VBS surgery | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time after VBS | Number of subjects | Changes in kyphosis angle after VBS surgery | 95%CI (upper) | One sample t-test | ||||

| Mean | SD | Minimum | Median | Maximum | ||||

| Immediately | 72 | −7.27 | 6.02 | −28.4 | −6.90 | 5.3 | −6.09 | p<0.001 |

| 1 month | 70 | −2.23 | 5.87 | −17.9 | −1.70 | 10.6 | −1.06 | p<0.002 |

| 3 months | 63 | −1.59 | 6.12 | −21.3 | −1.70 | 12.9 | −0.31 | p<0.043 |

| 6 months | 59 | −1.78 | 6.27 | −16.5 | −1.80 | 19.6 | −0.42 | p<0.033 |

| 12 months | 56 | −2.01 | 7.35 | −20.5 | −1.80 | 15.7 | −0.37 | p<0.045 |

| c. Kyphosis angle (Cobb angle) after VBS surgery | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time after VBS | Number of subjects | Mean | SD | Minimum | Median | Maximum | 95%CI (upper) | |

| Pre-op | 73 | 26.91 | 13.18 | 0.5 | 28.10 | 58.3 | 29.48 | |

| Immediately | 72 | 19.96 | 10.49 | 0.7 | 20.90 | 43.5 | 22.02 | |

| 1 month | 70 | 24.87 | 12.33 | 1.0 | 24.95 | 61.4 | 27.33 | |

| 3 months | 63 | 24.75 | 12.83 | 1.5 | 24.50 | 65.9 | 27.45 | |

| 6 months | 59 | 25.04 | 12.92 | 0.0 | 24.60 | 68.6 | 27.85 | |

| 12 months | 56 | 23.78 | 11.41 | 0.4 | 23.80 | 43.6 | 26.33 | |

CI, confidence interval; SD, standard deviation; VBS, vertebral body stenting; Pre-op, presurgery

AEs

There were three serious AEs for which a causal relationship with surgery using the VBS system could not be ruled out: spinal compression fracture, infective spondylitis, and spinal fracture. Malfunctions of the VBS device occurred in 13 patients (14.8%) (15 cases) and comprised breakage of provided peripheral equipment (five cases), balloon damage and PMMA leakage (four cases each), and failure of stent expansion and partial coloration of the catheter tube (one case each). No patient developed pulmonary infarction due to cement leakage.

New fractures occurred in 12 patients (13.6%) within 12 months after the VBS surgery; the new fractures occurred from days 4 to 37 in seven patients, from days 38 to 104 in four patients, and from days 105 to 210 in one patient. No new fractures were reported from days 211 to 425. All new fractures occurred at adjacent VBs; none occurred at nonadjacent VBs.

Discussion

The results demonstrated clinically significant restoration of the deformity and height of the collapsed VBs and relief of low back pain. As this was a single-arm study, direct comparison of our data with that of other studies is not possible; nevertheless, it may still be worthwhile to discuss the differences. Kato et al. compared the effects of rigid and soft bracing during conservative therapy for acute osteoporotic VCF in a prospective, randomized, multicenter study21). The AVBCP and MVBCP were 72.2%±13.5% and 71.4%±14.3% for the rigid and soft brace groups, respectively, at the start of the study, and 55.5%±16.2% and 53.0%±17.3%, respectively, after 48 weeks of treatment, showing that AVBCP and MVBCP decreased by approximately 17%-18%21). In contrast, in this study, VBS surgery increased AVBCP from 45.2%±20.9% to 66.3%±17.1% (an increase of 21.1%±14.1%) immediately after surgery, and the results were maintained for 12 months (65.4%±20.0% after 12 months). Two factors may have contributed to the significant restoration and maintenance of VBH. One factor is the expandable intrasomatic stent, which stably and uniformly restored the collapsed VB column by balloon inflation, enabling preservation of the restored VB during balloon deflation and removal and subsequent cement injection. The other factor is the minimum leakage of injected bone cement from the VB owing to the expanded stent, which helped maintain the restored VB. These two features are the hallmarks of the VBS system and are lacking in BKP13,14,22).

One of the reasons for the good reduction observed in this study may be that the balloon of the VBS system inflates without prolongation of the length, unlike BKP, which favors the restoration of the VB in the craniocaudal direction. Moreover, the side-opening cannula in the VBS system allows adjustment of the cement filling direction, which may minimize cement leakage.

Herein, new vertebral fractures occurred at the adjacent VB in 12 (13.6%) cases, whereas none occurred at nonadjacent VBs during the 12-month follow-up after VBS surgery. Two recent studies reported similar rates of new fracture after VBS surgery; one study reported a new fracture rate of 9% at adjacent VBs and 4% at nonadjacent VBs16), and the other reported new fracture rate of 17% at adjacent or nonadjacent VBs15). Likewise, a Japanese clinical trial of BKP reported a new fracture rate of 9.9% at adjacent VBs during 24 months of follow-up19). Because altered disk pressure profiles after vertebral fracture is a known risk factor for adjacent VB fracture23), VBS surgery may have restored the ability of the disk to distribute load evenly to the adjacent vertebral segment, thereby reducing the fracture risk in our patients.

The limitations of our study include the lack of a control group, small number of patients, and a relatively short observation period of 1 year. Longer-term studies are required. Nevertheless, the present study clearly demonstrated the efficacy and tolerability of VBS surgery for the treatment of acute VCF due to primary osteoporosis in Japanese patients.

Disclaimer: Yoshiharu Kawaguchi is one of the Editors of Spine Surgery and Related Research and on the journal's Editorial Committee. He was not involved in the editorial evaluation or decision to accept this article for publication at all.

Conflicts of Interest: Ryuichi Takemasa participated in the multicenter clinical trial as a medical expert and received an honorarium from Depyu Synthes Japan. The other authors declare that they have no relevant conflicts of interest.

Sources of Funding: This clinical trial was funded by Johnson and Johnson K.K, Medical Company.

Author Contributions: Ryuichi Takemasa: Medical advisor during clinical trials (designed the study, wrote the manuscript, etc.)

Other authors: Investigators of this clinical trial

Clinical Trial Registration Number: UMIN 000048506

Ethical Approval: The review board of each institute reviewed and approved the protocol of this study.

1) IRB of Kochi Medical School Hospital (Approval code: 1222601)

2) IRB of Nagasaki Rosai Hospital (Approval code: NA, Approved at the IRB held on February 9, 2012)

3) IRB of Wakayama Medical University Hospital (Approval code: 1-23023A)

4) IRB of Toyama University Hospital (Approval code: 2012-02-A001G)

5) IRB of Kanto Rosai Hospital (Approval code: NA, Approved at the IRB held on July 11, 2012)

6) IRB of Shimonoseki City Hospital (Approval code: NA, Approved at the IRB held on June 13, 2012)

7) IRB of Keio University Hospital (Approval code: 24-002)

8) IRB of Chubu Rosai Hospital (Approval code: R-297)

9) IRB of Teikyo University Chiba Medical Center (Approval code: 534)

Informed Consent: All patients who participated in the study provided written informed consent.

Acknowledgement

Funding from Johnson and Johnson K.K, Medical Company is gratefully acknowledged.

References

- 1.Ballane G, Cauley JA, Luckey MM, et al. Worldwide prevalence and incidence of osteoporotic vertebral fractures. Osteoporos Int. 2017;28(5):1531-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnell O, Kanis JA. An estimate of the worldwide prevalence and disability associated with osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int. 2006;17(12):1726-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rhyne AL 3rd, Banit D, Laxer E, et al. Kyphoplasty: report of eighty-two thoracolumbar osteoporotic vertebral fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2004;18(5):294-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Teng GG, Curtis JR, Saag KG. Mortality and osteoporotic fractures: is the link causal, and is it modifiable? Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2008;26(5 Suppl 51):S125-37. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Galibert P, Deramond H, Rosat P, et al. Preliminary note on the treatment of vertebral angioma by percutaneous acrylic vertebroplasty. Neurochirurgie. 1987;33(2):166-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heini PF, Wälchli B, Berlemann U. Percutaneous transpedicular vertebroplasty with PMMA: operative technique and early results. A prospective study for the treatment of osteoporotic compression fractures. Eur Spine J. 2000;9(5):445-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McGirt MJ, Parker SL, Wolinsky JP, et al. Vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty for the treatment of vertebral compression fractures: an evidenced-based review of the literature. Spine J. 2009;9(6):501-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khurjekar K, Shyam AK, Sancheti PK, et al. Correlation of kyphosis and wedge angles with outcome after percutaneous vertebroplasty: a prospective cohort study. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2011;19(1):35-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Komemushi A, Tanigawa N, Kariya S, et al. Percutaneous vertebroplasty for osteoporotic compression fracture: multivariate study of predictors of new vertebral body fracture. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2006;29(4):580-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ren H, Shen Y, Zhang YZ, et al. Correlative factor analysis on the complications resulting from cement leakage after percutaneous kyphoplasty in the treatment of osteoporotic vertebral compression fracture. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2010;23(7):e9-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Al-Nakshabandi NA. Percutaneous vertebroplasty complications. Ann Saudi Med. 2011;31(3):294-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rotter R, Martin H, Fuerderer S, et al. Vertebral body stenting: a new method for vertebral augmentation versus kyphoplasty. Eur Spine J. 2010;19(6):916-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ishiguro S, Kasai Y, Sudo A, et al. Percutaneous vertebroplasty for osteoporotic compression fractures using calcium phosphate cement. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2010;18(3):346-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Distefano D, Scarone P, Isalberti M, et al. The ‘armed concrete’ approach: stent-screw-assisted internal fixation (SAIF) reconstructs and internally fixates the most severe osteoporotic vertebral fractures. J Neurointerv Surg. 2021;13(1):63-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vanni D, Galzio R, Kazakova A, et al. Third-generation percutaneous vertebral augmentation systems. J Spine Surg. 2016;2(1):13-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diel P, Röder C, Perler G, et al. Radiographic and safety details of vertebral body stenting: results from a multicenter chart review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2013;14:233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.VBS. Vertebral body stenting system surgical technique guide [Internet]. Oberdorf (Switzerland): Synthes Gmbh. 2021 [cited 2022 Aug 27]. Available from: http://synthes.vo.llnwd.net/o16/LLNWMB8/INT%20Mobile/Synthes%20International/Product%20Support%20Material/legacy_Synthes_PDF/176837.pdf

- 18.Ledlie JT, Renfro M. Balloon kyphoplasty: one-year outcomes in vertebral body height restoration, chronic pain, and activity levels. J Neurosurg. 2003;98(1):36-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.KYPHON BKP System. Summary documents accompanying a written application for the manufacturers and sales approval of medical devices [Internet]. Osaka (Japan): Medtronic Sofamor Danek, Co. Ltd. 2015 [cited 2022 Aug 27]. Available from: https://www.pmda.go.jp/medical_devices/2009/M200900011/index.html

- 20.Vertebral fracture benchmark (revised 2012). Osteoporosis Japan. 2013;21(1):25-32. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kato T, Inose H, Ichimura S, et al. Comparison of rigid and soft-brace treatments for acute osteoporotic vertebral compression fracture: a prospective, randomized, multicenter study. J Clin Med. 2019;8(2):198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Feltes C, Fountas KN, Machinis T, et al. Immediate and early postoperative pain relief after kyphoplasty without significant restoration of vertebral body height in acute osteoporotic vertebral fractures. Neurosurg Focus. 2005;18(3):e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tzermiadianos MN, Renner SM, Phillips FM, et al. Altered disc pressure profile after an osteoporotic vertebral fracture is a risk factor for adjacent vertebral body fracture. Eur Spine J. 2008;17(11):1522-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]