Abstract

Uric acid and uracil were released at constant rates (0.95 and 0.4 nmol/min per g respectively) by the perfused rat hindlimb. Noradrenaline, vasopressin or angiotensin II further increased the release of these substances 2-5-fold, coinciding with increases in both perfusion pressure (vasoconstriction) and O2 uptake. The hindlimb also released, but in lesser amounts, uridine, hypoxanthine, xanthine, inosine and guanosine, and all but hypoxanthine and guanosine were increased during intense vasoconstriction. Uric acid and uracil releases were increased by noradrenaline in a dose-dependent manner. However, the release of these substances did not fully correspond with the dose-dependent increase in O2 uptake and perfusion pressure, where changes in the latter occurred at lower doses of noradrenaline. Sciatic-nerve stimulation (skeletal-muscle contraction) did not increase the release of uracil, uric acid or uridine, but instead increased the release of inosine (7-fold) and hypoxanthine (2-fold). Since the UTP content as well as the UTP/ATP ratio are higher in smooth muscle than in skeletal muscle, it is proposed that release of uric acid and uracil arises from increased metabolism of the respective adenosine and uridine nucleotides during intense constriction of smooth muscle.

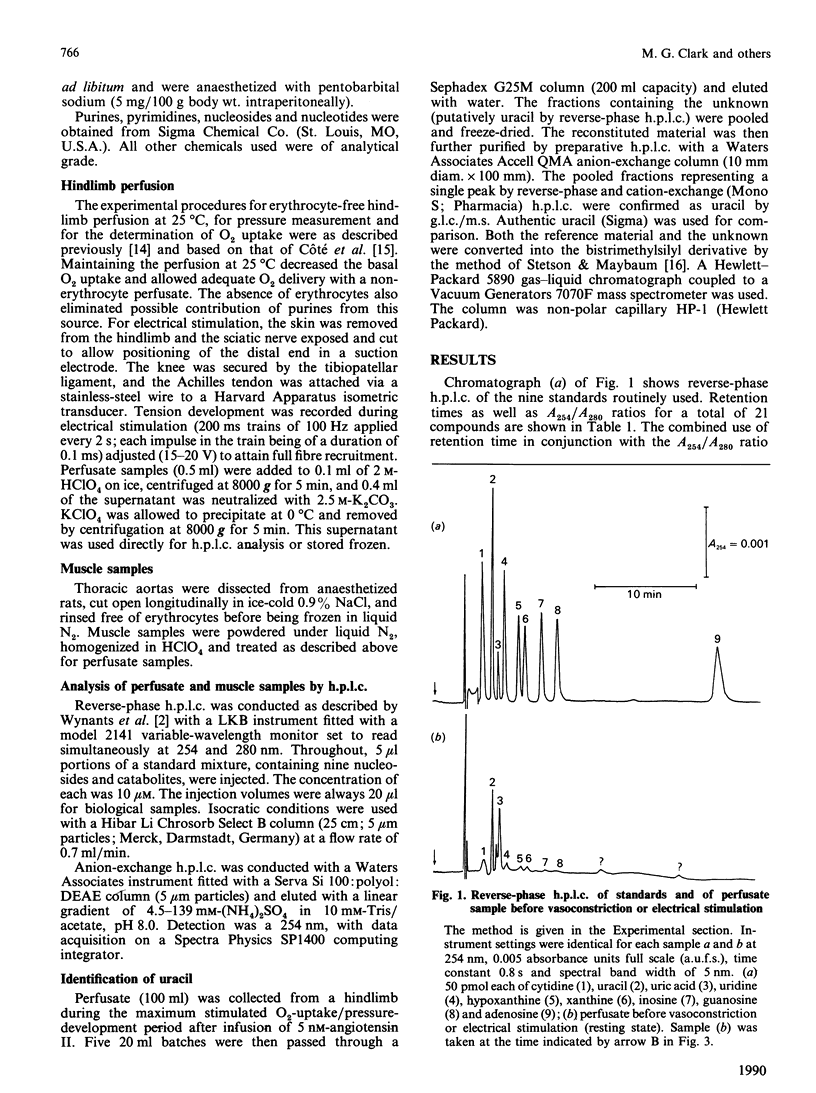

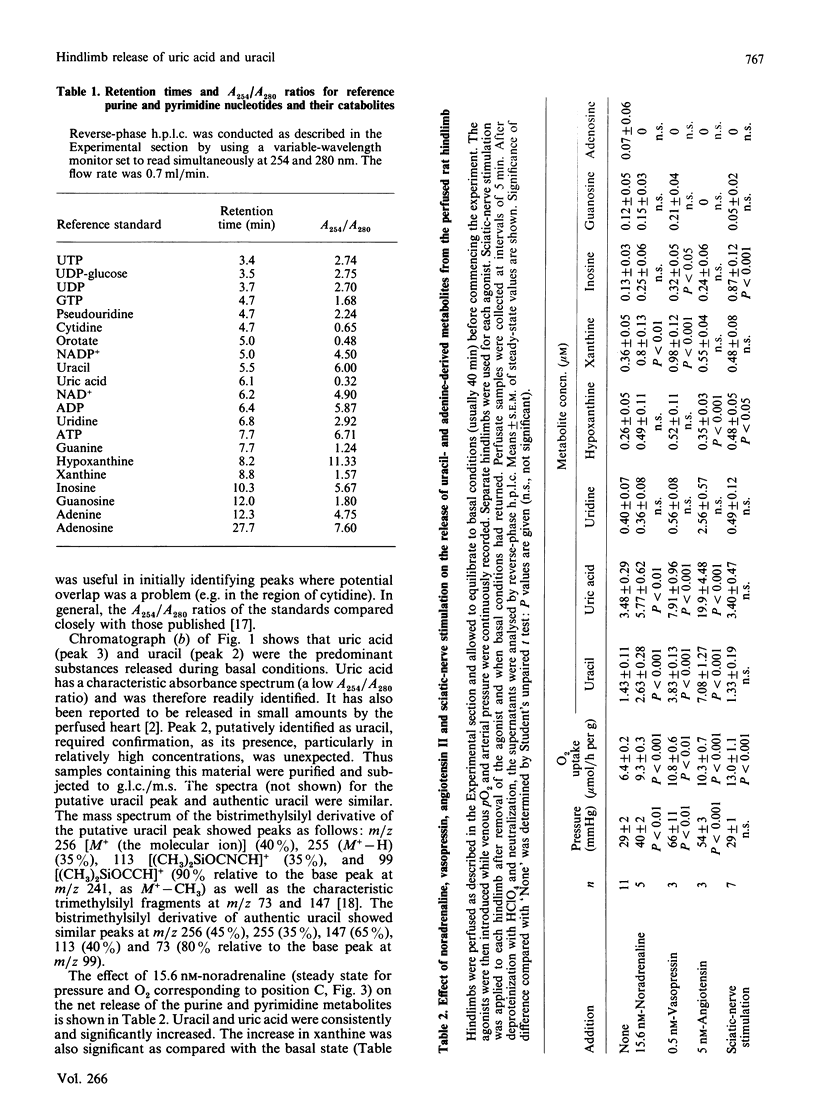

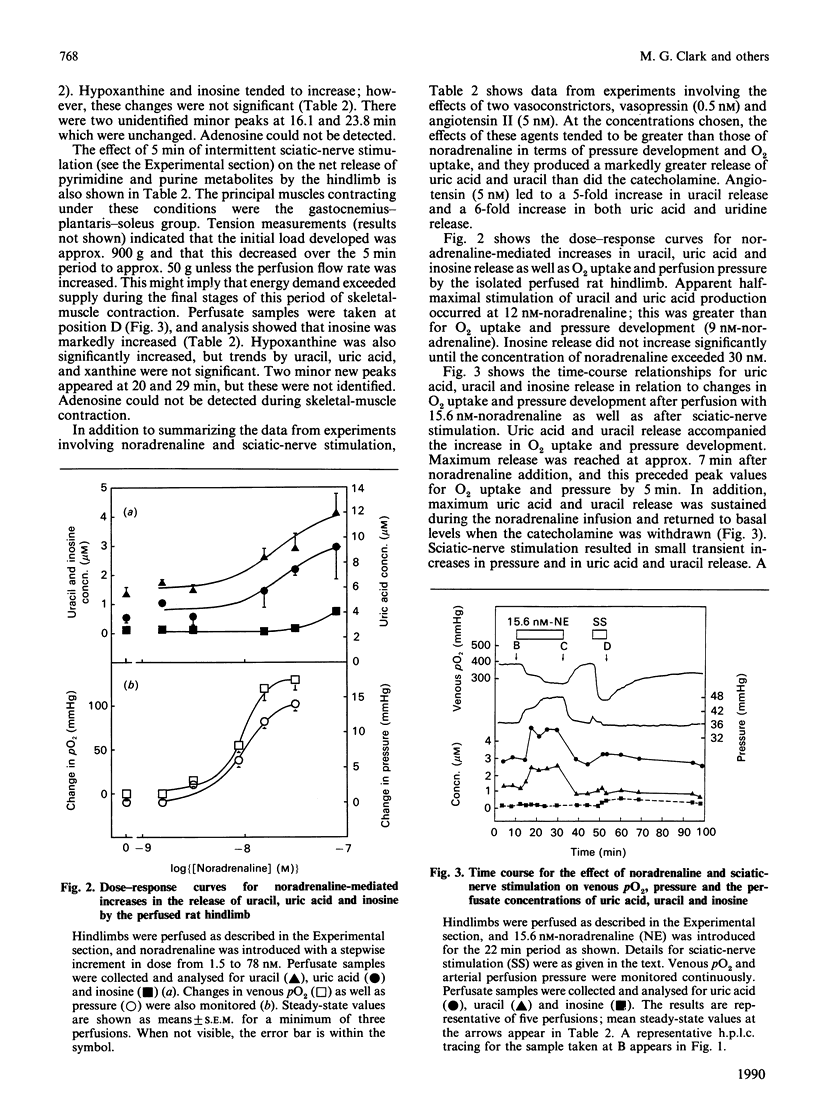

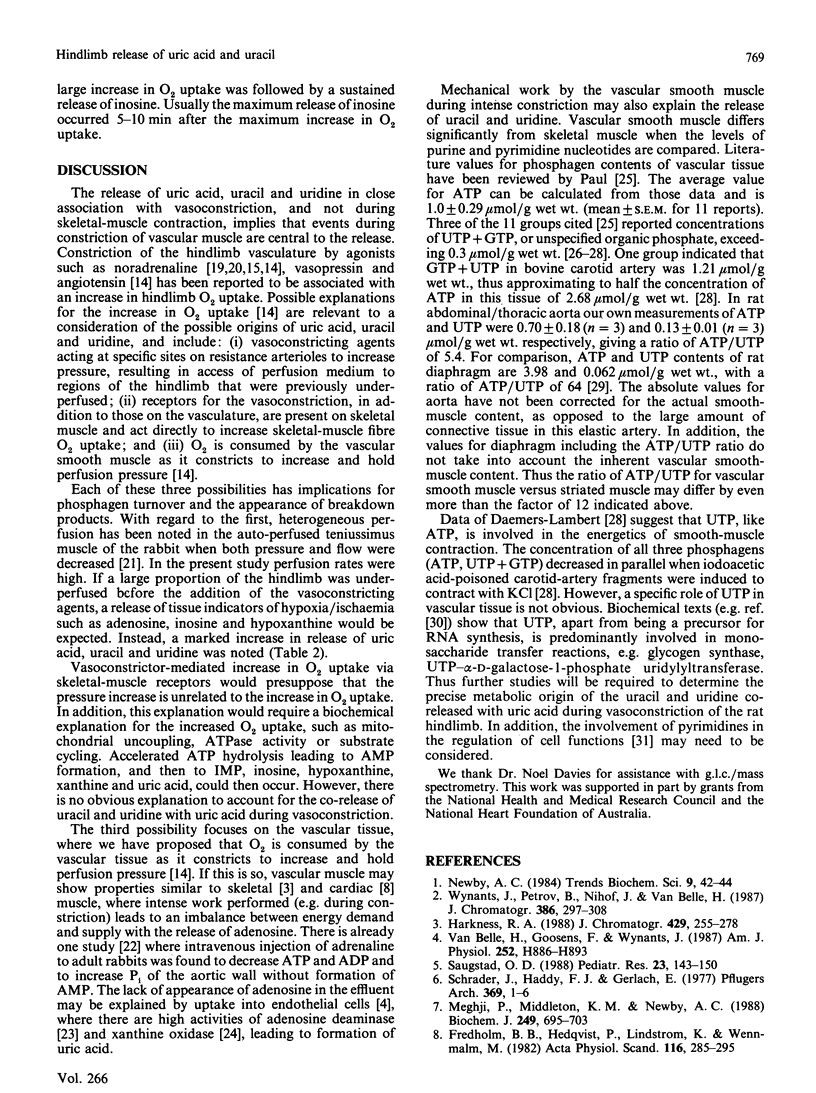

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Chapman A. G., Atkinson D. E. Stabilization of adenylate energy charge by the adenylate deaminase reaction. J Biol Chem. 1973 Dec 10;248(23):8309–8312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung L., Bridger W. A. Activation of rabbit cardiac AMP aminohydrolase by ADP: a component of a mechanism guarding against ATP depletion. FEBS Lett. 1976 May 1;64(2):338–340. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(76)80323-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffee C. J., Solano C. Rat muscle 5'-adenylic acid aminohydrolase. Role of K+ and adenylate energy charge in expression of kinetic and regulatory properties. J Biol Chem. 1977 Mar 10;252(5):1606–1612. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colquhoun E. Q., Hettiarachchi M., Ye J. M., Richter E. A., Hniat A. J., Rattigan S., Clark M. G. Vasopressin and angiotensin II stimulate oxygen uptake in the perfused rat hindlimb. Life Sci. 1988;43(21):1747–1754. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(88)90487-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Côté C., Thibault M. C., Valliéres J. Effect of endurance training and chronic isoproterenol treatment on skeletal muscle sensitivity to norepinephrine. Life Sci. 1985 Aug 26;37(8):695–701. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(85)90538-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAEMERS-LAMBERT C. ACTION DU CHLORURE DE POTASSIUM SUR LE M'ETABOLISME DES ESTERS PHOSPHOR'ES ET LE TONUS DU MUSCLE ART'ERIEL (CAROTIDE DE BOVID'E) Angiologica. 1964;1:249–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredholm B. B., Hedqvist P., Lindström K., Wennmalm M. Release of nucleosides and nucleotides from the rabbit heart by sympathetic nerve stimulation. Acta Physiol Scand. 1982 Nov;116(3):285–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1982.tb07142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harkness R. A. Hypoxanthine, xanthine and uridine in body fluids, indicators of ATP depletion. J Chromatogr. 1988 Jul 29;429:255–278. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(00)83873-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry J. C., Gautheron D., Gras J., Frey J. Variations des nucléotides adényliques et des fractions phosphorylées du tissu aortique sous l'influence de l'adrénaline. Bull Soc Chim Biol (Paris) 1965;47(11):1941–1950. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarasch E. D., Bruder G., Heid H. W. Significance of xanthine oxidase in capillary endothelial cells. Acta Physiol Scand Suppl. 1986;548:39–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LUNDHOLM L., MOHME-LUNDHOLM E. The effects of adrenaline and glucose on the content of high-energy phosphate esters in substrate-depleted vascular smooth muscle. Acta Physiol Scand. 1962 Oct;56:130–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1962.tb02490.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakings D. B., Adamson R. H. Quantitative analysis of 5-fluorouracil in human serum by selected ion monitoring gas chromatography--mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr. 1978 Nov 1;146(3):512–517. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(00)81214-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindbom L., Arfors K. E. Mechanisms and site of control for variation in the number of perfused capillaries in skeletal muscle. Int J Microcirc Clin Exp. 1985;4(1):19–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MANDEL P., KEMPF E. [Free nucleotides of the aortic tissue]. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1961 Jul 22;51:184–186. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(61)91035-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meghji P., Middleton K. M., Newby A. C. Absolute rates of adenosine formation during ischaemia in rat and pigeon hearts. Biochem J. 1988 Feb 1;249(3):695–703. doi: 10.1042/bj2490695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meghji P., Middleton K., Hassall C. J., Phillips M. I., Newby A. C. Evidence for extracellular deamination of adenosine in the rat heart. Int J Biochem. 1988;20(12):1335–1341. doi: 10.1016/s0020-711x(98)90001-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer R. A., Terjung R. L. AMP deamination and IMP reamination in working skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol. 1980 Jul;239(1):C32–C38. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1980.239.1.C32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter E. A., Ruderman N. B., Galbo H. Alpha and beta adrenergic effects on metabolism in contracting, perfused muscle. Acta Physiol Scand. 1982 Nov;116(3):215–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1982.tb07133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saugstad O. D. Hypoxanthine as an indicator of hypoxia: its role in health and disease through free radical production. Pediatr Res. 1988 Feb;23(2):143–150. doi: 10.1203/00006450-198802000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrader J., Haddy F. J., Gerlach E. Release of adenosine, inosine and hypoxanthine from the isolated guinea pig heart during hypoxia, flow-autoregulation and reactive hyperemia. Pflugers Arch. 1977 May 6;369(1):1–6. doi: 10.1007/BF00580802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seifert R., Schultz G. Involvement of pyrimidinoceptors in the regulation of cell functions by uridine and by uracil nucleotides. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1989 Sep;10(9):365–369. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(89)90009-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stetson P. L., Maybaum J., Shukla U. A., Ensminger W. D. Simultaneous determination of thymine and 5-bromouracil in DNA hydrolysates using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry with selected-ion monitoring. J Chromatogr. 1986 Feb 14;375(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(00)83686-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Belle H., Goossens F., Wynants J. Formation and release of purine catabolites during hypoperfusion, anoxia, and ischemia. Am J Physiol. 1987 May;252(5 Pt 2):H886–H893. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1987.252.5.H886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wynants J., Petrov B., Nijhof J., Van Belle H. Optimization of a high-performance liquid chromatographic method for the determination of nucleosides and their catabolites. Application to cat and rabbit heart perfusates. J Chromatogr. 1987 Jan 16;386:297–308. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(01)94606-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]