Abstract

Shared decision-making (SDM) and multidisciplinary team-based care delivery are recommended across several cardiology clinical practice guidelines. However, evidence for benefit and guidance on implementation are limited. Informed consent, the use of patient decision aids, or the documentation of these elements for governmental or societal agencies may be conflated as SDM. SDM is a bidirectional exchange between experts: patients are the experts on their goals, values, and preferences, and clinicians provide their expertise on clinical factors. In this Expert Panel perspective, we review the current state of SDM in team-based cardiovascular care and propose best practice recommendations for multidisciplinary team implementation of SDM.

Key words: shared decision-making, cardiovascular disease, interventional cardiology, electrophysiology, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, prevention, chest pain, heart failure, cardiac imaging, valvular heart disease, structural heart

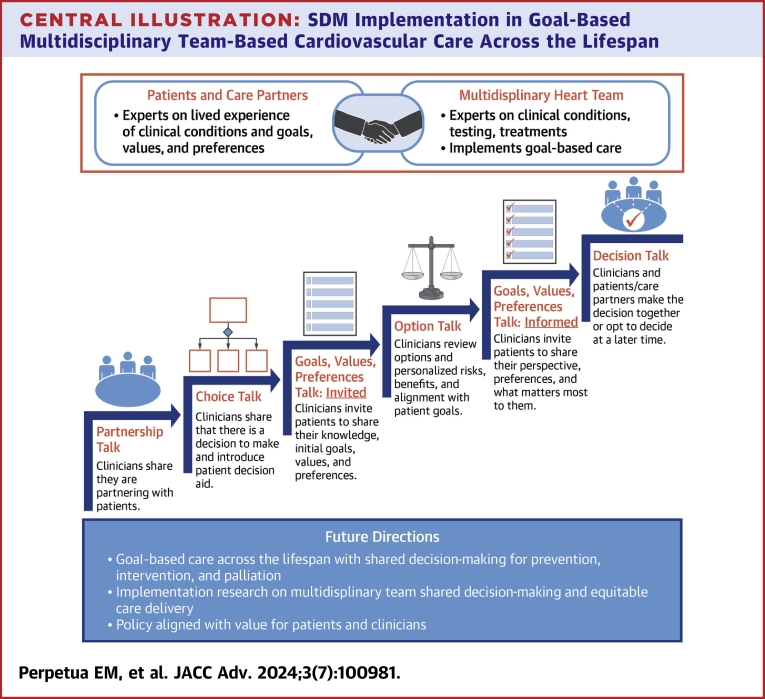

Central Illustration

Highlights

-

•

Evidence for SDM implementation is limited, and adoption is influenced by complex interpersonal, organizational, and environmental factors.

-

•

SDM is an ethical right in which the patient is the expert on their goals, values, and preferences and partners with clinical experts in CV care.

-

•

SDM in goal-based CV care must be implemented with a multidisciplinary, team-based approach, considering the attitudes, competencies, and processes that support success.

-

•

Future research efforts must assess the efficacy and effectiveness of team-based SDM to improve adoption and further guide implementation.

Shared decision-making (SDM) is a collaborative process in which a patient’s goals of care, values, and preferences are incorporated into informed health care choices.1 Professional society recommendations, quality registry surveillance, and regulatory requirements aim to increase SDM adoption in cardiovascular (CV) care.2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 However, limited evidence for SDM implementation and complexity at the interpersonal, organizational, and environmental levels may turn SDM into nothing more than a “checkbox.”10 The opportunity lies in transforming SDM from an unfunded, poorly implemented mandate into a well-defined, efficient, and effective process aligning clinicians and patients for the lifetime management of CV conditions.

Expert panel

This expert panel is comprised of clinicians and patients across CV medicine subspecialties, particularly in areas in which there is a Class I recommendation, payer policy, or quality registry surveillance for SDM. While recognizing there is no silver bullet for SDM adoption, we provide an operating definition, principles, and strategies for SDM with a patient-centered, team-based approach. Practical examples of adaptable workflows, scripts, and tools are offered for broad applicability and site-specific customization, which are aligned with the patient and tiered to the condition and decision at hand. Informing this effort is the Practical, Robust Implementation and Sustainability Model, a framework for facilitating SDM adoption at the participant, organizational, and system level; adapting protocols at the local level and sharing best practices; and encouraging spread and sustainability.11 Recommendations to generate the evidence base and evaluate the effectiveness of SDM are also discussed.

Turning the aspirational into the operational: a primer for implementation

Operating principles for SDM in CV team-based care

-

1.SDM is a conversation between experts. The patient is the expert on their goals, values, preferences, needs, well-being, personal risks, and desired outcomes. Clinicians provide expertise on clinical factors and risks/net benefit.

- a.

-

b.A conversation includes an invitation. If the patient does not share goals and preferences, this important knowledge is not available to clinicians. Clinicians can avoid “misdiagnosing” patient preferences by helping patients prepare for these conversations and expressly inviting patients to share what matters most.15

-

2.

While research on implementation is needed, SDM should not be judged on whether it produces better health outcomes. Patients have inherent self-determination and an ethical right to be provided with information and to make decisions collaboratively with clinicians.16 It simply means for the patient, “No decision about me without me.”17

-

3.

While incorporation of SDM into practice has been shown to be facilitated or limited by multiple factors (Figure 1), favorable clinician attitudes are more important for SDM adoption than skills, and skills are more important than tools including patient decision aids (PDAs).18

-

4.Contemporary models for SDM integrate patient goals, values, preferences, and PDAs in a patient-centered, team-based approach.19, 20, 21

-

a.Competencies for SDM are listening skills, language skills (ie, use of native language and the ability to modulate from power laden disciplinary vocabulary to plain language appropriate for age and literacy level), emotional intelligence, nonverbal skills, cultural and age-appropriateness, and attitudinal skills including awareness of bias.22

- b.

-

a.

-

5.

SDM and SDM policy should aim to reduce not worsen health disparities. Patients with a clinical indication for evidence-based, guideline-directed therapies should be able to access treatment options for which they are eligible and have SDM conversations about these treatment options. To that end, SDM may also help ensure that patients do not receive inappropriate or unwanted care.

Figure 1.

Factors Influencing Shared Decision Making Adoption and Implementation

CV = cardiovascular; MDT = multidisciplinary team; PDA = patient decision aid; SDM = shared decision-making.

Defining the intervention

What is SDM?

SDM is an interpersonal communication intervention contextualized in the organizational and systems environment. In CV care, a multidisciplinary heart team (MDHT) may include nurses, advanced practice nurses, physician associates, pharmacists, social workers, allied health professionals, and physicians. Members of the MDHT deliberate with patients for point-in-time decisions along a continuum of noninvasiveness or invasiveness: surveillance, therapeutic lifestyle changes, and pharmacological, catheter-based, surgical, palliative (symptoms/stress relief, and spiritual support) therapies (Table 1). The implications of these decisions must incorporate the patient’s evolving goals and preferences, lifetime management considerations, access to care, and social determinants of health (SDOH).

Table 1.

Examples of Lifetime Shared Decision-Making in Team-Based Cardiovascular Care

| Condition | Shared Decision-Making Examples Across the Lifespan |

Team-Based Care |

|---|---|---|

| Risk for ischemic heart disease (ie, familial dyslipidemia, early coronary artery disease, hypertension) and/or heart failure |

|

Primary care, general cardiology, interventional cardiology |

| Chest pain |

|

Primary care, general cardiology, interventional cardiology |

| Obstructive coronary artery disease, symptomatic |

|

Primary care, general cardiology interventional cardiology, cardiac surgery |

| Peripheral arterial disease |

|

Primary care, general cardiology interventional cardiology, interventional radiology, vascular surgery, podiatry, wound clinic, palliative care, tobacco cessation counselor, physical/occupational therapy |

| Atrial fibrillation |

|

Primary care, general cardiology, electrophysiology, interventional cardiology, surgery |

| Ventricular arrhythmias |

|

Primary care, general cardiology, electrophysiology, cardiology genetics |

| Valvular heart disease |

|

Primary care, general cardiology, interventional cardiology cardiac surgery, heart failure, palliative care |

| Heart failure |

|

Primary care, general cardiology, advanced heart failure/transplant, interventional cardiology, cardiac surgery, palliative care |

| Congenital heart disease |

|

Primary care, general cardiology, congenital heart disease (pediatrics, adult), heart failure, interventional cardiology, cardiac surgery, palliative care |

| Women’s health |

|

Primary care, general cardiology, women’s health, obstetrics |

| Cardio-oncology |

|

Primary care, general cardiology, oncology, interventional cardiology, cardiac surgery, palliative care |

Goals of care

Goals of care, or the overarching aims of the patient’s own stated values, preferences, and priorities for their health and wellbeing, have been found to be the most meaningful outcome measure for patients.12, 13, 14 Patients may say, “I want to feel better,” “I want to live longer,” “I just want to go home,” “I want this other treatment but my heart has to be taken care of first,” “I want to take care of my spouse/partner/family member,” and “I want to be able to go to or do (a specific activity or event)”.12,25 Goal-based care incorporates these goals and preferences into the treatment plan and uses plain language to prevent bias, unintentional influence, and impedance of patient choice.13,14 While goals of care assessment and conversations are core competencies for nursing, advanced practice nurses, physician associates, and the specialty of palliative care, they have not been traditionally considered core competencies for cardiologists.23,24,26,27

The explicit assessment of patient-stated goals and whether the patient perceives these goals to be met may serve as an important patient-reported quality indicator for SDM. Expressly inviting the patient to share their goals and evaluating feasibility and achievement of these goals can demonstrate positive regard for the patient and their self-determination. Skilled, ongoing assessment of patients’ goals, values, preferences, and SDOH to deliver goal-based care may also reduce broad cultural stereotyping and lead the way to reducing health inequities.

Patient decision aids

PDAs are visual tools that aim to reduce ambiguity in terms, augment patient knowledge, simplify complex pathophysiologic processes, and propose diagnostics or therapeutics. Through visuals and depictions, patient preferences may be aligned with benefits and risks. International PDA Standards Collaboration Guidelines name 5 key elements a PDA must cover: situation or diagnosis, choice awareness, option clarification, discussion of harm and benefits, and deliberation of patient preferences.28 Many studies have demonstrated that PDAs increase patient knowledge and engagement while reducing decisional conflict.29 This finding extends to diverse groups and those with lower health literacy.30 A PDA that has not been formally validated or developed according to the International PDA Standards Collaboration standards may not align with the bidirectional exchange of SDM.

Participant perspectives

Patients and Clinicians

Patient- and clinician-level factors serve as facilitators and barriers for SDM. These include biophysiological, psychosocial, and cognitive factors, developmental stage, psychological safety, assessment of health and numerical literacy, teaching/learning needs and style, emotional intelligence, language, communication, perceived power, current health status, perceived well-being, and situational factors.31 One study found up to 50% of patients struggled to answer basic questions about treatment choices because of 1 or more of these factors.31 Moreover, clinicians inquired about patients’ preferences less than one-third of the time. Clinicians assess preferences less frequently in patients with lower literacy or education, a potential driver of health disparities in those who potentially need the most information to make decisions about treatment choices.31

Clinician variables that positively and negatively impact routine adoption of SDM include: perception of and actual time to treat,32,33 lack of applicability due to patient or clinical characteristics,32 racial and/or language discordance between clinician and patient,34 belief it is already part of routine practice,1,35 lack of physician training,36 and the belief that regulatory requirements are a means to contain costs through reduced utilization.37 SDM may be oversimplified to the legally required common denominator of informed consent, predisposing clinicians to believe SDM is reserved only for procedures or completed when a form is signed14 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Informed Consent vs Shared Decision Making

SDOH and health disparities

Social context is a primary driver of CV outcomes in many instances.38 SDOH, or the “conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age”39 include aspects like race/ethnicity, social support and structure, culture and language, access to care, education, income, transportation, food security, insurance status, and the social and residential environment.40 To achieve health equity, clinicians should be aware of the ways in which these social and structural factors can lead to racism, bias, mistreatment, and exclusion often outside of the patient’s control. SDM frameworks currently do not consider SDOH but must incorporate and inquire about them, given the extent to which patients’ lived environment impacts health, preferences, and outcomes.

Models for implementation

There are many well-known SDM models in the literature. The principles and steps synthesized into the Central Illustration and tools were informed by the Goal-Based Three Talk Model, the Agency for Health Care Research and Quality SHARE Model, and the Canadian Interprofessional SDM Model.14,41, 42, 43

Central Illustration.

SDM Implementation in Goal-Based Multidisciplinary Team-Based Cardiovascular Care Across the Lifespan

A multidisciplinary team implements goal-based cardiovascular care. Goals talk is added to the classic SDM elements of choice talk, option talk, preference talk, and decision talk. Together, goal-based care and action planning are possible and iterative. Team agreements and clinical pathways support the success of SDM in conversations across the lifespan for prevention, intervention, and palliation. The organizational and environmental contexts are aligned to cultivate successful SDM in clinical care, policy, and research. Adapted with permission from Elwyn G, Durand MA, Song J, et al. A three-talk model for shared decision making: multistage consultation process. BMJ. 2017;359:j4891. SDM = shared decision-making.

Team and goals talk

The patient and clinicians acknowledge there are preference-sensitive options for treatment, and a decision between them must be made. The clinicians expressly invite the patient and desired care partner(s) into the conversation. The clinicians state that their roles are: 1) to provide necessary information about the disease state or condition and the risks and benefits of the treatment options; 2) to understand the patient’s knowledge, goals, values, preferences in this situation, SDOH, and their overall goals of well-being; and 3) to support the patient in the decision-making process based on how much the patient would like to participate. The patient clarifies their goals, role, and participation for themselves and their care partners.

Option talk

The clinician shares unbiased, evidence-based information on a disease state or condition and the risks and benefits of available treatment options. This includes individualized patient education using validated tools, evidence-based risk assessments related to the diagnosis or condition, and SDM tools such as PDAs.

Decision talk

The clinicians support the patient and care partners in making informed, preference-based decisions. The SDM conversation may continue another time, at the patient and care partner’s request and/or for certain treatment decisions, following a MDHT conference. This scenario may apply for complex coronary artery disease revascularization, valvular heart disease therapies, congenital heart disease therapies, advanced heart failure therapies, chronic limb-threatening ischemia, and cardio-oncology treatment (see Table 1).

Organizational Perspectives

Evidence and policies

Best practice recommendations for SDM implementation are proposed; however, there is limited evidence to guide MDHT implementation. PDAs are the most well-studied aspect of SDM processes, particularly in patients with chest pain at low- to intermediate risk for obstructive coronary artery disease who have the options of observation and diagnostic imaging vs discharge from the emergency room for outpatient follow-up.44 SDM in these patients has a Class I recommendation, Level of Evidence: A, the highest level reserved for randomized clinical trials.3,45 SDM does not have a Level of Evidence: A for any other CV population or health care choice (Table 2). PDAs are often lacking in many areas of cardiology, even when they are sorely needed. For example, coronary artery revascularization for stable ischemic heart disease is one of the most frequently performed procedures in the United States but the sole validated PDA has been minimally adopted.25,53 Studies have demonstrated patients with coronary artery disease and peripheral arterial disease want a shared or autonomous role in decision-making but have decisional conflict or discordance with their clinicians (ie, their choice is not aligned with their provider).46,47 This is largely attributed to the lack of SDM tools.

Table 2.

State-of-the-Art of Shared Decision-Making in Cardiovascular Care

| Cardiovascular Subspecialty | Population and Decision | SDM in Guideline | CORa | LOEa | Validated PDA | SDM in CMS NCDg,h,i | SDM in Quality Registryj,k |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General | Chest pain, cardiac testing, or outpatient evaluationa | YES | I | A | YES | No NCD for cardiac testing or imaging | -- |

| Interventional cardiology | Coronary artery disease, any revascularizationb | YES | I | C | YES | No NCD for coronary revascularization | -- |

| Valvular heart disease | Aortic valve disease, bioprosthetic valve, SAVR, or TAVRc | YES | I | C | YES |

|

SDM and PDA for TAVR monitored in TVT Registry |

| Aortic valve disease, bioprosthetic or mechanical valvec | YES | I | C | NO |

|

SDM and PDA for TAVR monitored in TVT Registry | |

| Mitral regurgitation, secondary and heart failure, TEER, SMVR/r, GDMT, and advanced HF therapyc,d | YES | I | - | NO |

|

SDM and PDA for TEER monitored in TVT Registry | |

| Electrophysiology | Atrial fibrillation, LAAO or anticoagulatione | YES | I | - | YES | SDM with PDA required with nonimplanting MD in LAAO NCD | SDM and PDA for LAAO monitored in LAAO Registry |

| Ventricular arrhythmia or risk of sudden cardiac death, ICDd | YES | I | C | YES | SDM required with competent member of the team in ICD NCD | SDM and PDA for ICD monitored in ICD Registry | |

| Heart failure | End-stage heart failure, LVAD or palliative caref | YES | I | C | YES | No SDM in LVAD NCD; palliative care required on team | -- |

In many guidelines, SDM carries a COR I (green); however high-quality evidence and validated PDAs may be lacking (yellow, red). The requirement of SDM by governmental agencies and monitoring by quality registry does not appear to be driven by quality of evidence, prevalence of disease, or treatment but by cost containment in preference-sensitive decisions. COR/LOE: I, highest level recommendation; LOE, A, strongest evidence from randomized clinical trials; B, Moderate quality evidence (randomized or nonrandomized); C, Observational or Registry Studies.

SDM = shared decision making; COR = Class of Recommendation; LOE = Level of Evidence; PDA = patient decision aid; CMS NCD = Center for Medicare Services National Coverage Determination; SAVR = surgical aortic valve replacement; TAVR = transcatheter aortic valve replacement; TEER = transcatheter edge-to-edge repair; SMVR/r = surgical mitral valve replacement or repair; LAAO = left atrial appendage occlusion; ICD = implantable cardioverter-defibrillator.

Gulati M, Levy PD, Mukherjee D, et al. 2021 AHA/ACC/ASE/CHEST/SAEM/SCCT/SCMR guideline for the evaluation and diagnosis of chest pain: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;78(22):e187-e285.

Lawton JS, Tamis-Holland JE, Bangalore S, et al. 2021 ACC/AHA/SCAI guideline for coronary artery revascularization: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on clinical practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79(2):e21-e129.

Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on clinical practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77(4):e25-e197.

Heidenreich PA, Bozkurt B, Aguilar D, et al. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79(17):e263-e421.

January CT, Wann LS, Calkins H, et al. 2019 AHA/ACC/HRS focused update of the 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74(1):104-132.

Al-Khatib SM, Stevenson WG, Ackerman MJ, et al. 2017 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(14):e91-e220.

Centers for Medicare Services. Transcatheter Edge-to-Edge Repair (TEER) for Mitral Valve Regurgitation. 2021. Accessed January 20. 2024. https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/view/ncd.aspx?NCDId=363.

Centers for Medicare Services. National coverage determination for left atrial appendage occlusion. 2016. Accessed January 20, 2024. https://www.cms.gov/medicarecoverage-database/view/ncd.aspx?NCDId=367.

Centers for Medicare Services. National coverage determination for implantable automatic defibrillators. 2018. Accessed January 20, 2024. https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coveragedatabase/view/ncd.aspx?NCDId=110.

STS/ACC TVT Registry. STS/ACC TVT registry data collection forms v.3.0. Accessed January 20, 2024. https://www.ncdr.com/WebNCDR/tvt/publicpage/data-collection.

American College of Cardiology National Cardiovascular Data Registries. Left Atrial Appendage Occlusion NCDR Data Form v1.2. 2022. Accessed January 20, 2024. https://cvquality.acc.org/NCDR-Home/registries/hospital-registries/laaoregistry.

Use of PDAs is increasingly coupled with policy and quality registry monitoring to improve SDM adoption.48 Validated PDAs are available from American College of Cardiology CardioSmart (https://www.cardiosmart.org/topics/decisions/decision-aids) and partner Colorado Program for Patient Centered Decisions (https://patientdecisionaid.org/decision-aids/) for implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs) in patients with heart failure and/or risk for sudden cardiac death and anticoagulation and left atrial appendage occlusion (LAAO) for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation. It is noted that PDAs are tools that may co-exist with, but alone do not equate to SDM. More robust evidence is needed to support implementation policies on SDM.

Team-based CV care

SDM in CV care involves the MDHT members best suited to facilitate a high-quality decision with the patient. However, the principles of effective team-based care—clear roles, shared goals, mutual trust, effective communication, and measurable processes and outcomes—can be difficult to implement in an inherently hierarchal health care system.2,49 SDM competencies and specific training programs are not routinely standardized or mandated.20 Nonetheless, many SDM education programs exist, mainly focused on physician training; over 148 programs were identified in a scoping review.50

The MDHT has since expanded from the dyad of interventional cardiologist and cardiothoracic surgeon partnering in landmark trials for coronary and valvular heart disease. The contemporary MDHT approach to SDM incorporates the physicians, advanced practice clinicians (APCs), nurses, and allied health providers best equipped to support and engage in conversation with the patient and care partners.2,23,24 Competencies for APCs in Adult CV Medicine include the interpersonal and communication skills to “engage patients in SDM based upon balanced presentations of risks, benefits, and alternatives, factoring in patients’ values and preferences.”26 A recent Expert Panel perspective on the MDHT recommends APCs as part of the MDHT and SDM processes for the treatment of coronary artery disease, valvular heart disease, and heart failure.2 An example of the MDHT approach to SDM for a clinical encounter is depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Multidisicplinary Heart Team Encounter for Shared Decision Making

PDA = patient decision aid; SDM = shared decision-making.

Novel MDHT approaches to SDM involve innovative clinical encounter models and research. In 1 model, patients and care partners considering the same decision meet in a group clinic (ie, n = 6-8). This group clinic brings patients and care partners together with the MDHT, followed by one-on-one meetings with the clinicians, allied health staff, and schedulers. To begin, the MDHT provides patient education and leads sharing exercises. During this presentation, a medical assistant, nurse, APC, physician, and research coordinator use videos, PDAs, and facilitated discussion to elicit values and goals. Patients and care partners share goals, values, preferences, and questions with one another and the MDHT. A physician and/or APC then meet one-on-one with each patient and care partner to confirm the decision, finalize the plan, or invite the patient to return for a typical clinical encounter. The nurse, scheduler, and research coordinator meet one-on-one with patients and care partners to schedule the next steps.51

It is important to assess and acknowledge factors that influence the adoption and implementation of a team approach to SDM.36 In a small study, cardiologists and cardiac surgeons on MDHTs for heart valve disease reported they would engage in SDM if they had time, resources, and well-informed patients.52 Interestingly, physicians also ranked the MDHT, PDAs, and education of nurses and allied health professionals in SDM as the least important SDM facilitators.52 This finding suggests that there is an opportunity to cultivate an environment primed for SDM and engage physicians in the expanded MDHT approach.

Throughout clinical practice and research it is noted that CV team members assess patient goals, values, and preferences; review PDAs; evaluate risk using validated tools; educate patients on treatment options; and participate in or lead team-based SDM.51,53,54 In a survey of U.S. structural heart centers, nurses and allied health respondents (N = 165) reported that their primary responsibilities for transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) included assessing patient goals of care, communicating patient goals of care and social needs to the team, and responsibility for compliance with payer policy and quality registries, which now encompass SDM.54 Further, in studies examining what matters most to patients in SDM, nurse-led research is prominent and well-cited.51,55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60 As the front line of patient care, coordination, and communication, nurses, APC, and allied health professionals are uniquely positioned to participate with physician colleagues in the SDM process.

Implementing SDM without considering these real-world team-based care dynamics and workflows can be fraught with challenges. Nichols et al25 sought to evaluate the impact of a PDA (an Option Grid) in a SDM encounter with an interventional cardiologist, car diac surgeon, and patient. Barriers to enrollment were aligning the 2 physician schedules to deliver the PDA and the lack of consensus between the cardiologists and surgeons. These challenges ultimately resulted in termination of the study (Treatment decisions for Multi-vessel coronary artery disease: option Grid guiding treatment decisions; NCT02611050).25 Often, it is the nurse or APC who presents the PDA and engages in these conversations with patients, and the MDHT assures continuity with goal-based care and policy.25,51 Thus, subsequent studies on SDM now incorporate the team-based care approach.46,51 In PCI Choice, 25% of the clinicians performing SDM in percutaneous coronary intervention for stable ischemic heart disease were nonphysicians.53 In studies involving pharmacologic intervention, a nonphysician MDHT member may have more time and unique training to engage the patient in discussion. For example, a pharmacist might be best positioned to provide a thorough conversation regarding the risk-benefit calculus of anticoagulation with atrial fibrillation.61 A team-based approach may facilitate operational success of SDM and skill-task-aligned, top-of-license practice.

Some of the challenges unique to SDM in CV care may impact decisional urgency including: 1) acuity and triage considerations germane to the specialty; 2) preprocedural time constraints including acuity affecting SDM; 3) incorporation of diagnostic findings that must be available to inform the decision and may be affected by the patient’s inability to participate due to sedation; 4) lack of relationship with the proceduralist; and 5) recognition that a staged decision and time for the patient to process the choice may be favorable and require follow-up.

Environmental considerations

The health care environment and ecosystem stakeholders influence how SDM is implemented. Organizational and governmental policy, professional society guidelines, and current and emerging research shape the rules and resources for SDM. These considerations impact implementation spread and sustainability.

Involve Stakeholders in the development of policy for SDM

CV stakeholders are often not well represented in the development of policies for SDM and treatment. Policies involving SDM in CV care aim to protect the selection of patients with demonstrated treatment benefits, promote safe and rational dispersion, improve quality, and contain costs. In the United States, the Center for Medicare Services’ National Coverage Determinations specify requirements for hospital use of certain therapies, including TAVR, transcatheter edge-to-edge repair, LAAO, ICD, and left ventricular assist devices, to receive payment or reimbursement. These policies may contribute to disparities in patient care when treatment options for a disease are regulated differently. Take, for example, atrial fibrillation with a high risk for bleeding and stroke or symptomatic severe aortic stenosis, which have transcatheter and surgical approaches to treatment. Patient access and SDM on certain options may depend upon policy or the referral process, which may create or promulgate treatment disparities.

If SDM is part of policy, the impact on access to care and quality of these processes must also be monitored. For certain treatments, governmental and societal policies drive prescriptive delivery of SDM. Societal quality registries require data submission on SDM performance and PDA use for LAAO, ICD, TAVR, transcatheter edge-to-edge repair, transcatheter mitral valve replacement, and transcatheter tricuspid replacement.9,62 Policies for hospital reimbursement of certain procedures in the U.S. also impact clinical workflows and may influence patient access to treatment. The Centers for Medicare Services National Coverage Determination for LAAO specifies that SDM must be performed by a nonimplanting physician, presumably the referring physician/primary care provider. This physician may not be well equipped to assess an individual’s risks and the net benefit of stroke prevention with an LAAO procedure, as compared to anticoagulation or no treatment. On the other hand, the implanting physician may not be the best suited to assess and align treatment options with patient goals and disease trajectory across the lifespan.6 A responsibility often in the domain of nurses and APCs in CV care is aligning meaningful SDM, policy, and optimal patient care and coordination across the referring physician, proceduralists, and the primary care provider.51,63 In recognition of this gap with the LAAO policy, the subsequent SDM mandate in the Centers for Medicare Services National Coverage Determination for ICDs specifically identifies all clinicians suited to have SDM conversations including nurse practitioners, clinical nurse specialists, and physician associates.8 If SDM is part of policy, there must also be monitoring for its impact on access to and quality of care.

Create policy that values MDHT SDM

Policy needs to reflect SDM implementation in team-based clinical workflows. SDM conversations often occur between multiple team members and patients. However, patient visits involving SDM with multiple cardiology clinicians on the same day may not be reimbursed by payers, despite the unique knowledge and skillset each CV subspecialty provides. These payer reimbursement policies aim to contain costs but fail to capture the value and time of a MDHT.6, 7, 8 Moreover, payer policies that specify the team members and processes needed for SDM in complex patients may undermine MDHT efforts to schedule and coordinate team-based care on the same day (ie, streamlined visits for patients and care partners who may have personal and logistical challenges to health care access). Teams aim to improve collaboration and communication and reduce the patient and family burden of accessing health care.2,49 Payer policies may affect patient-centered practices that aim to improve care coordination and reduce care fragmentation.6, 7, 8,11,30

Despite efforts to accelerate the transition to a value-based payment model, progress has been slow, and health care largely remains in a fee-for-service model. Reimbursement models are misaligned with policy for SDM in CV care and the complexity and volume of patients in need. Capacity and support must be prioritized, as patients and CV subspecialties tend to crossover many disciplines and care delivery areas. Alignment of policy with organizational and health care system resources and patient-centered clinical pathways are recommended to support SDM adoption.

Step-by-step implementation of SDM in team-based CV care

This panel proposes that implementing team-based clinical pathways involving the full CV care team can cultivate SDM adoption and success.64 Implementation involves a logic model blueprinting the inputs, activities, outputs, and outcomes. The MDHT must understand the contextual factors (inputs) and determine site-specific ways to implement the proposed processes (activities). Together, the goal is to meet the Quintuple Aim of improving quality, experience for patients and the team, costs, access, and equity of care (outputs and outcomes).64

-

•

Identify shared goals (outputs) for the CV care team and create a scorecard or dashboard (ie, 100% of the time, the team invites and documents incorporation of patient knowledge, goals, values, and preferences in clinical touchpoints; uses a PDA; collects quality and registry data on SDM; reviews patient satisfaction measures).

-

•Determine the agreed-upon definitions and components of SDM.

-

oComplete team education/training on SDM (eg, the Agency for Health Care Research and Quality SHARE model, which has free modules) and the relevant risk assessment tools and treatment options.

-

oDetermine the SDM model or framework to use (Central Illustration) and validate or agree upon PDAs (American College of Cardiology CardioSmart, Colorado Program for Patient Decisions, Ottawa Hospital PDAs) and their workflows.

-

oProvide examples of best practice and scripting, aligned to the patient and clinician involved (Table 3).

-

oConsensus on the explicit invitation to the patient to share their knowledge about the options and their goals, values, and preferences.

-

o

-

•

Delineate clear roles for SDM, in which each member of the team performs different but complementary responsibilities (Table 4, Figure 3), as appropriate to the setting (ie, inpatient or outpatient).

-

•

Consensus on SDM templates, related workflows, and monitoring (Tables 4 and 5).

-

•

Engage in ongoing quality assessment and performance improvement (eg, SDM quality assessment review as an audit form of the above items) with operational meetings to discuss experience and address deficits including unmet goals.

Table 3.

Depicting Steps and Scripting Examples of Clinician Conversation: What Does Shared Decision Making Look and Sound Like?

| What Does Shared Decision Making Look Like? | What Does Shared Decision Making Sound Like? |

|---|---|

Seek your patient’s participation

|

|

Help your patient explore and compare their treatment options

|

|

Assess your patient’s goals, values, and preferences

|

|

Reach a decision with your patient

|

|

Evaluate the decision with your patient

|

|

Elwyn et al 2003, 2020; Joseph-Williams et al 2017; Makoul et al 2006; Agency of Healthcare Quality and Research 2022.

Table 4.

Multidisciplinary Heart Team Shared Decision-Making in the Clinical Pathway From Referral to Follow-Up

| Referral | Consultation | Post Consultation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient | Before consultation, reflect upon or consider coaching to deliberate:

|

|

|

| Scheduling coordinator |

|

|

|

| Registry coordinator |

|

|

|

| Nurse coordinator |

|

|

|

| Advanced practice clinician (ie, advanced practice nurse practitioner or clinical nurse specialist, physician associate, pharmacist) |

|

|

|

| Consulting physician |

|

|

|

| Leadership administration |

|

|

|

APC = advanced practice clinician; EHR = electronic health record; ICD = implantable cardioverter-defibrillation; LAAO = left atrial appendage occlusion; NCD = national coverage determination; PDA = patient decision aid(s); SDM = shared decision making; SDOH = social determinants of health; TAVR = transcatheter aortic valve replacement; TEER = transcatheter edge to edge repair; TMVR = transcatheter mitral valve replacement; TTVR = transcatheter tricuspid valve replacement; TVT = transcatheter valve therapies.

Table 5.

Examples of Documentation in the Electronic Health Record

| Example A: Sample Documentation of SDM Encounter |

|---|

| “At today's visit, we discussed aortic valve stenosis, treatment options including medical therapy, SAVR, palliation, and TAVR. The patient-stated goals are “breathe again; stay out of the hospital, hopefully live longer, and get home to my husband.” We discussed the intricacies of each approach and the rationale for considering one vs another. We also reviewed the data suggesting equipoise between a surgical approach and a transcatheter. The patient states her preference to move forward with TAVR if feasible following review of CTA.” |

| Example B: Sample Documentation of SDM in Goal-Based Care |

|---|

|

ACC/AHA stage of valvular disease severity: D1 – High Gradient Symptomatic Severe Aortic Stenosis. Echocardiogram demonstrates an AVA of 0.6 cm2, mean gradient of 40 mm Hg, peak velocity of 4 m/s. Preserved left ventricular size and function with no other significant valve disease or pulmonary hypertension. STS predicted risk of mortality with SAVR: 5.76% Imaging studies: Anatomically feasible for transfemoral approach with current transcatheter valve therapy. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline recommendation scenarios for SAVR vs TAVR (Class I recommendation; Level of Evidence: A) For symptomatic patients with severe AS who are 65 to 80 years of age with no anatomic contraindication to transfemoral TAVR, either SAVR or transfemoral TAVR is recommended after shared decision-making. Patient decision aid: CardioSmart Patient Decision Aid for TAVR vs SAVR in patients at low to intermediate surgical risk was provided to patient in advance of today’s visit. PDA was used to invite the patient to share goals and guide the conversation. Patient-stated goals, values, preferences, SDOH: The patient's goal is to return to baseline activity: “walking to the store” and “caring for grandchildren.” After deliberation with the patient, we think this can be best achieved with TAVR. For periprocedural and follow-up care, she reports adequate support from her husband Max, who drives, and 2 adult children who live in the same town. Daughter Maya is most involved; she has 3 children: Sam 9, Sara 11, and Kelly 18. Risk/benefit discussion: Discussed in detail with the patient and family who were available at the bedside. We discussed aortic valve stenosis and treatment options including medical therapy, surgical aortic valve replacement, palliation, and transcatheter aortic valve replacement. We discussed the intricacies of each approach and the rationale for considering one vs another. Preference discussion and decision: After all estimated risks/benefits of each option or no treatment were reviewed, the patient and family members had the opportunity to ask questions, which were answered to their satisfaction. She verbalizes understanding of her valve disease, treatment options, and risks/benefits. She clearly expresses her preference for TAVR. Plan: Schedule TAVR within 2-4 weeks with follow-up at 2-4 weeks and 1 year. Evaluate/reassess patient goals and progress toward patient goals/goals met or not met at follow-up visits. |

ACC = American College of Cardiology; AHA = American Heart Association; AVA = aortic valve area; PDA = patient decision aid; SAVR = surgical aortic valve replacement; SDOH = social determinants of health; STS = Society of Thoracic Surgeons; TAVR = transcatheter aortic valve replacement.

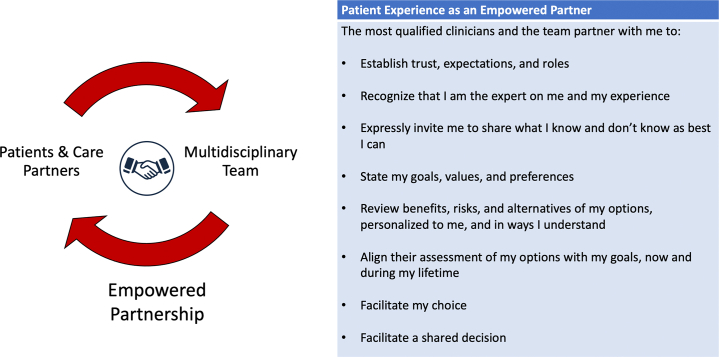

These strategies to improve process, quality, and implementation of SDM are ongoing in the continuous improvement cycle. By starting with 1 or 2 targeted changes, a feedback loop of communication and data collection can begin, and small wins may be accumulated. Teams may select different components of SDM to implement, finding ease in using PDAs, inviting the patient as a partner to the conversation, routinely assessing health literacy, SDOH, and patient-stated goals, and finding personal meaning and human connection in the SDM elements necessary for payer and quality monitoring. Through these efforts, MDHT may build the flywheel for widespread adoption of SDM and an empowered clinician-patient partnership (Figure 4). The paradigm is a patient-centered approach to decision-making, independent of the clinical assessment of treatment equipoise.

Figure 4.

Empowered Patient-Clinician Partnership

Future research needs and priorities

Population considerations

Oversimplifying the complexity of SDM and patient/clinician-level factors that allow for authentic conversation pose a risk of widening existing health disparities. Of particular importance will be to establish whether SDM actually improves health outcomes, patient-reported outcomes, and equity in diverse populations and women.65 Studies must be intentionally designed to recruit diverse and often underrepresented populations, and thus must have investigators and leadership that represent these groups.66

Design and methodology considerations

Research must focus on optimal SDM implementation and establish valid measures of success in diverse populations and treatment decisions. Interventions should be collaboratively developed and delivered involving patients and MDHT members representative of diverse demographics and disciplines. Real-world pragmatic implementation must be studied, and PDAs require validation. Certain elements should be standardized such as clinician training, expressed invitation of the patient to participate as a partner, explicit assessment of patient’s stated goals of care, and the use of validated tools and processes. Research and funding that includes development and implementation of the intervention should be made available. Taken together, these strategies and tactics will ensure we are conscientious of furthering old or introducing new biases that are not relevant to the patient and their lifespan.

Outcomes considerations

The research question should not be whether SDM improves health outcomes, but rather whether SDM meets the patient’s desired goals. Patient self-determination means a patient may decide on an option based on their prioritization of certain risks or benefits over others. Research should also investigate the impact of literacy, SDOH, and the use of technology to improve SDM use and efficacy.61 The Randomized Evaluation of Decision Support Intervention for Atrial Fibrillation study exemplifies 1 type of research design and outcomes for future study in the SDM domain.67 Another is the Aortic Valve Improved Treatment Approaches Trial for SDM implementation.51 Ideally, there would be alignment of interventions to outcomes that are patient-centered and team-based, as well as evaluation of a SDM model for cognitive and behavioral outcomes. Interventions to remove barriers to SDM can include education/training, resource and process optimization, audit feedback, and performance incentives.68 Program evaluation and quality improvement will also be important elements of understanding and optimizing SDM implementation at the local level.

Conclusions

SDM is a collaborative process in which clinicians and patients provide their respective expertise to partner in health care choices. Ideally this partnership is facilitated in an environment that contributes to optimal health outcomes and health care equity. The patient is the expert on their lived experience and is expressly invited and empowered to share their goals of care, values, and informed preferences. SDOH, individual risks and benefits for the decision at hand, and potential future decisions are explicitly assessed. Clinicians on the MDHT use their expertise to integrate patient-generated data with the evidence, guidelines, and assessment of patient net benefit with the available treatment options. The ideal SDM environment includes validated tools that assist in the development of informed patient preferences and aid in communication between clinicians, patients, and care partners. SDM will require innovation and reconsideration of the standard clinic visit, using helpful models and frameworks for implementation not only in a single encounter but along the continuum of care. Well-defined measures of a successful multidisciplinary SDM process are needed, as well as continued research on the impact of SDM on patient, MDHT, and health system outcomes.

Funding support and author disclosures

Dr Perpetua has been a consultant for Edwards Lifesciences and is a consultant for Abbott Vascular. Ms. Palmer is a consultant for Edwards Lifesciences. Dr Beckman is a consultant for Norvartis, Janssen, and JanOne. Dr Keegan is a consultant for Edwards Lifesciences and Abbott Vascular. Dr Guibone is a consultant for Medtronic and Abbott Vascular. Dr Lauck is a consultant for Edwards Lifesciences. Dr Le has received research grant funding from Janssen and is a consultant for Novartis. Dr Lindman is supported by R01AG073633 from the National Institutes of Health and has been a consultant for and received investigator-initiated research grants from Edwards Lifesciences. Dr Wyman has been a consultant for Edwards Lifesciences and Boston Scientific. Dr Gulati has been a consultant for Esperion, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Medtronic. There was no funding support for this expert panel. All other authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

Acknowledgments

For their support and advice in this publication, the authors gratefully acknowledge Abby Cestoni, Michael Hargrett, and the American College of Cardiology Academic Council, Section, and Council Leadership.

Footnotes

The authors attest they are in compliance with human studies committees and animal welfare regulations of the authors’ institutions and Food and Drug Administration guidelines, including patient consent where appropriate. For more information, visit the Author Center.

References

- 1.Hess E.P., Coylewright M., Frosch D.L., Shah N.D. Implementation of shared decision making in cardiovascular care: past, present, and future. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2014;7(5):797–803. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.113.000351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Batchelor W.B., Anwaruddin S., Wang D.D., et al. The multidisciplinary heart team in cardiovascular medicine. JACC Adv. 2023;2(1) doi: 10.1016/j.jacadv.2022.100160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gulati M., Levy P.D., Mukherjee D., et al. 2021 AHA/ACC/ASE/CHEST/SAEM/SCCT/SCMR guideline for the evaluation and diagnosis of chest pain: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on clinical practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;78(22):e187–e285. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.07.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lawton J.S., Tamis-Holland J.E., Bangalore S., et al. 2021 ACC/AHA/SCAI guideline for coronary artery revascularization: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on clinical practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79(2):e21–e129. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Otto C.M., Nishimura R.A., Bonow R.O., et al. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on clinical practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77(4):e25–e197. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Medicare Services National coverage determination for left atrial appendage occlusion. 2016. https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/view/ncd.aspx?NCDId=367

- 7.STS/ACC TVT Registry STS/ACC TVT registry data collection forms v.3.0. https://www.ncdr.com/WebNCDR/tvt/publicpage/data-collection

- 8.Centers for Medicare Services National coverage determination for implantable automatic defibrillators. 2018. https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/view/ncd.aspx?NCDId=110

- 9.American College of Cardiology National Cardiovascular Data Registries Left Atrial Appendage Occlusion NCDR Data Form v1.2. 2022 https://cvquality.acc.org/NCDR-Home/registries/hospital-registries/laao-registry [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joseph-Williams N., Elwyn G., Edwards A. Knowledge is not power for patients: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of patient-reported barriers and facilitators to shared decision making. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;94(3):291–309. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2013.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matlock D.D., Fukunaga M.I., Tan A., et al. Enhancing success of Medicare's shared decision making mandates using implementation science: examples applying the pragmatic robust implementation and sustainability model (PRISM) MDM Policy Pract. 2020;5(2) doi: 10.1177/2381468320963070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coylewright M., Palmer R., O'Neill E.S., Robb J.F., Fried T.R. Patient-defined goals for the treatment of severe aortic stenosis: a qualitative analysis. Health Expect. 2016;19(5):1036–1043. doi: 10.1111/hex.12393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scalia P., van Deen W.K., Engel J.A., et al. Eliciting patients' healthcare goals and concerns: do questions influence responses? Chronic Illn. 2022;18(3):708–716. doi: 10.1177/17423953211067417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elwyn G., Vermunt N. Goal-based shared decision-making: developing an integrated model. J Patient Exp. 2020;7(5):688–696. doi: 10.1177/2374373519878604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mulley A.G., Trimble C., Elwyn G. Stop the silent misdiagnosis: patients' preferences matter. BMJ. 2012;345 doi: 10.1136/bmj.e6572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.United States Preventive Services Task Force Collaboration and shared decision-making between patients and clinicians in preventive health care decisions and US preventive services task Force recommendations. JAMA. 2022;327(12):1171–1176. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.3267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coulter A., Collins A. Kings Fund; 2011. Making Shared Decision Making a Reality. No Decision About Me, Without Me; pp. 1–56. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elwyn G., Laitner S., Coulter A., Walker E., Watson P., Thomson R. Implementing shared decision making in the NHS. BMJ. 2010;341 doi: 10.1136/bmj.c5146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elwyn G., Edwards A., Wensing M., Hood K., Atwell C., Grol R. Shared decision making: developing the OPTION scale for measuring patient involvement. Qual Saf Health Care. 2003;12(2):93–99. doi: 10.1136/qhc.12.2.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Légaré F., Politi M.C., Drolet R., Desroches S., Stacey D., Bekker H. Training health professionals in shared decision-making: an international environmental scan. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;88(2):159–169. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality The SHARE approach—Essential steps of shared decision-making: Quick reference guide. 2020. https://www.ahrq.gov/health-literacy/professional-training/shared-decision/index.html

- 22.Oshima Lee E., Emanuel E.J. Shared decision making to improve care and reduce costs. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(1):6–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1209500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.American Association of Colleges of Nursing Essentials of nursing practice. 2020. https://www.aacnnursing.org/Portals/0/PDFs/Publications/Essentials-2021.pdf

- 24.American Association of Physician Assistants Competencies for the PA profession. 2021. https://www.aapa.org/download/90503/

- 25.Nichols E.L., Elwyn G., DiScipio A., et al. Cardiology providers' recommendations for treatments and use of patient decision aids for multivessel coronary artery disease. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2021;21(1):410. doi: 10.1186/s12872-021-02223-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rodgers G.P., Linderbaum J.A., Pearson D.D., et al. 2020 ACC clinical competencies for nurse practitioners and physician assistants in Adult cardiovascular medicine: a Report of the ACC competency management Committee. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75(19):2483–2517. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.United States Medical Licensing Exam . 2022. USMLE Competencies and Tasks. Federation of State Medical Boards of the United States, Inc. (FSMB), and National Board of Medical Examiners® (NBME®) [Google Scholar]

- 28.Elwyn G., O'Connor A., Stacey D., et al. Developing a quality criteria framework for patient decision aids: online international Delphi consensus process. BMJ. 2006;333(7565):417. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38926.629329.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stacey D., Bennett C.L., Barry M.J., et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(10):Cd001431. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001431.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coylewright M., Branda M., Inselman J.W., et al. Impact of sociodemographic patient characteristics on the efficacy of decision AIDS: a patient-level meta-analysis of 7 randomized trials. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2014;7(3):360–367. doi: 10.1161/HCQ.0000000000000006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zikmund-Fisher B.J., Couper M.P., Singer E., et al. The decisions study: a Nationwide survey of United States adults regarding 9 common medical decisions. Med Decis Making. 2010;30(5_suppl):20–34. doi: 10.1177/0272989X09353792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Legare F., Ratte S., Gravel K., Graham I.D. Barriers and facilitators to implementing shared decision-making in clinical practice: update of a systematic review of health professionals' perceptions. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;73(3):526–535. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yahanda A.T., Mozersky J. What's the role of time in shared decision making? AMA J Ethics. 2020;22(5):E416–E422. doi: 10.1001/amajethics.2020.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Traylor A.H., Schmittdiel J.A., Uratsu C.S., Mangione C.M., Subramanian U. Adherence to cardiovascular disease medications: does patient-provider race/ethnicity and language concordance matter? J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(11):1172–1177. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1424-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Joseph-Williams N., Lloyd A., Edwards A., et al. Implementing shared decision making in the NHS: lessons from the MAGIC programme. BMJ. 2017;357 doi: 10.1136/bmj.j1744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Coylewright M., O'Neill E., Sherman A., et al. The learning Curve for shared decision-making in symptomatic aortic stenosis. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5(4):442–448. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2019.5719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Merchant F.M., Dickert N.W., Jr., Howard D.H. Mandatory shared decision making by the centers for Medicare & Medicaid services for cardiovascular procedures and other Tests. JAMA. 2018;320(7):641–642. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.6617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Havranek E.P., Mujahid M.S., Barr D.A., et al. Social determinants of risk and outcomes for cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2015;132(9):873–898. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.World Health Organization . 2020. Social Determinants of Health.https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health#tab=tab_1 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Turkson-Ocran R.N., Ogunwole S.M., Hines A.L., Peterson P.N. Shared decision making in cardiovascular patient care to address cardiovascular disease disparities. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.120.018183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Légaré F., Stacey D., Pouliot S., et al. Interprofessionalism and shared decision-making in primary care: a stepwise approach towards a new model. J Interprof Care. 2011;25(1):18–25. doi: 10.3109/13561820.2010.490502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ottawa Hospital Research Institute Patient decision aids: implementation Toolkit. https://decisionaid.ohri.ca/implement.html

- 43.Hargraves I.G., Fournier A.K., Montori V.M., Bierman A.S. Generalized shared decision making approaches and patient problems. Adapting AHRQ's SHARE Approach for Purposeful SDM. Patient Educ Couns. 2020;103(10):2192–2199. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2020.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hsia R.Y., Hale Z., Tabas J.A. A national study of the prevalence of Life-threatening Diagnoses in patients with chest pain. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(7):1029–1032. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.2498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hess E.P., Hollander J.E., Schaffer J.T., et al. Shared decision making in patients with low risk chest pain: prospective randomized pragmatic trial. BMJ. 2016;355 doi: 10.1136/bmj.i6165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shah A.M., Siddiqui E., Cuenca C., et al. Trends in the utilization and reimbursement of coronary revascularization in the United States Medicare population from 2010 to 2018. Cathet Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;98(2):E205–E212. doi: 10.1002/ccd.29649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Provance J.B., Spertus J.A., Decker C., Jones P.G., Smolderen K.G. Assessing patient preferences for shared decision-making in peripheral artery disease. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2019;12(8) doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.119.005730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Beneficiary engagement and incentives models: shared decision making model. 2016. https://innovation.cms.gov/webinars-and-forums/bene-sdmloi

- 49.Mitchell P., Wynia R., Golden B., et al. 2012. Core principles and values of effective team-based health care. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Singh Ospina N., Toloza F.J.K., Barrera F., Bylund C.L., Erwin P.J., Montori V. Educational programs to teach shared decision making to medical trainees: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2020;103(6):1082–1094. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2019.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Col N.F., Otero D., Lindman B.R., et al. What matters most to patients with severe aortic stenosis when choosing treatment? Framing the conversation for shared decision making. PLoS One. 2022;17(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0270209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lindeboom J.J., Coylewright M., Etnel J.R.G., Nieboer A.P., Hartman J.M., Takkenberg J.J.M. Shared decision making in the heart team: current team attitudes and review. Struct Heart. 2021;5(2):163–167. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Coylewright M., Dick S., Zmolek B., et al. PCI choice decision aid for stable coronary artery disease: a randomized trial. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2016;9(6):767–776. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.116.002641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Perpetua E.M., Clarke S.E., Guibone K.A., Keegan P.A., Speight M.K. Surveying the Landscape of structural heart disease coordination: an exploratory study of the coordinator role. Struct Heart. 2019;3(3):201–210. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lauck S.B., Baumbusch J., Achtem L., et al. Factors influencing the decision of older adults to be assessed for transcatheter aortic valve implantation: an exploratory study. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2016;15(7):486–494. doi: 10.1177/1474515115612927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Olsson K., Näslund U., Nilsson J., Hörnsten Å. Experiences of and Coping with severe aortic stenosis Among patients Waiting for transcatheter aortic valve implantation. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2016;31(3):255–261. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0000000000000231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Olsson K., Näslund U., Nilsson J., Hörnsten Å. Patients' decision making about Undergoing transcatheter aortic valve implantation for severe aortic stenosis. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2016;31(6):523–528. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0000000000000282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Olsson K., Näslund U., Nilsson J., Hörnsten Å. Patients’ experiences of the transcatheter aortic valve implantation trajectory: a grounded theory study. Nurs Open. 2018;5(2):149–157. doi: 10.1002/nop2.124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pel-Littel R.E., Snaterse M., Teppich N.M., et al. Barriers and facilitators for shared decision making in older patients with multiple chronic conditions: a systematic review. BMC Geriatr. 2021;21(1):112. doi: 10.1186/s12877-021-02050-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lytvyn L., Guyatt G.H., Manja V., et al. Patient values and preferences on transcatheter or surgical aortic valve replacement therapy for aortic stenosis: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2016;6(9) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chung M.K., Fagerlin A., Wang P.J., et al. Shared decision making in cardiac Electrophysiology procedures and Arrhythmia management. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2021;14(12) doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.121.007958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.National Cardiovascular Data Registy (NCDR) EP device implant registry generator and leads v_2.3. 2023. https://cvquality.acc.org/NCDR-Home/registries/hospital-registries/ep-device-implant-registrycoverage-database/view/ncd.aspx?NCDId=367

- 63.Brush J.E., Jr., Handberg E.M., Biga C., et al. 2015 ACC health policy Statement on cardiovascular team-based care and the role of advanced practice providers. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65(19):2118–2136. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.03.550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nundy S., Cooper L.A., Mate K.S. The Quintuple aim for health care improvement: a new Imperative to advance health equity. JAMA. 2022;327(6):521–522. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.25181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tan N.Q.P., Volk R.J. Addressing disparities in patients' opportunities for and competencies in shared decision making. BMJ Qual Saf. 2022;31:75–78. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2021-013533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Reza N., Gruen J., Bozkurt B. Representation of women in heart failure clinical trials: barriers to enrollment and strategies to close the gap. Am Heart J. 2022;13 doi: 10.1016/j.ahjo.2022.100093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jones A.E., McCarty M.M., Brito J.P., et al. Randomized evaluation of decision support interventions for atrial fibrillation: Rationale and design of the RED-AF study. Am Heart J. 2022;248:42–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2022.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bauer M.S., Damschroder L., Hagedorn H., Smith J., Kilbourne A.M. An introduction to implementation science for the non-specialist. BMC Psychol. 2015;3(1):32. doi: 10.1186/s40359-015-0089-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]