Abstract

Ovarian cancers are still largely treated with platinum-based chemotherapy as the standard of care, yet few biomarkers of clinical response have had an impact on clinical decision making as of yet. Two particular challenges faced in mechanistically deciphering platinum responsiveness in ovarian cancer have been the suitability of cell line models for ovarian cancer subtypes and the availability of information on comparatively how sensitive ovarian cancer cell lines are to platinum. We performed one of the most comprehensive profiles to date on 36 ovarian cancer cell lines across over seven subtypes and integrated drug response and multiomic data to improve on our understanding of the best cell line models for platinum responsiveness in ovarian cancer. RNA-seq analysis of the 36 cell lines in a single batch experiment largely conforms with the currently accepted subtyping of ovarian cancers, further supporting other studies that have reclassified cell lines and demonstrate that commonly used cell lines are poor models of high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma. We performed drug dose response assays in the 32 of these cell lines for cisplatin and carboplatin, providing a quantitative database of IC50s for these drugs. Our results demonstrate that cell lines largely fall either well above or below the equivalent dose of the clinical maximally achievable dose (Cmax) of each compound, allowing designation of cell lines as sensitive or resistant. We performed differential expression analysis for high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma cell lines to identify gene expression correlating with platinum-response. Further, we generated two platinum-resistant derivatives each for OVCAR3 and OVCAR4, as well as leveraged clinically-resistant PEO1/PEO4/PEO6 and PEA1/PEA2 isogenic models to perform differential expression analysis for seven total isogenic pairs of platinum resistant cell lines. While gene expression changes overall were heterogeneous and vast, common themes were innate immunity/STAT activation, epithelial to mesenchymal transition and stemness, and platinum influx/efflux regulators. In addition to gene expression analyses, we performed copy number signature analysis and orthogonal measures of homologous recombination deficiency (HRD) scar scores and copy number burden, which is the first report to our knowledge applying field-standard copy number signatures to ovarian cancer cell lines. We also examined markers and functional readouts of stemness that revealed that cell lines are poor models for examination of stemness contributions to platinum resistance, likely pointing to the fact that this is a transient state. Overall this study serves as a resource to determine the best cell lines to utilize for ovarian cancer research on certain subtypes and platinum response studies, as well as sparks new hypotheses for future study in ovarian cancer.

Introduction

Ovarian cancers, of which high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma (HGSOC) is the most common subtype, account for 5% of all cancer deaths in females in the United States1. Current standard of care for HGSOC is platinum-based chemotherapy (carboplatin, cisplatin + taxane)2, but over half of patients are diagnosed with Stage IV HGSOC and face a dismal 31.5% five-year survival rate3. Overall, the progression free interval for first-line OvCa is ~18 months, and around 80% of patients are considered sensitive to platinum-based chemotherapy4. However, patients initially sensitive to platinum-based chemotherapy display decreased progression-free intervals and response rates on platinum with each subsequent recurrence5. OvCa patients often undergo prolonged periods of remission following initial response to surgery and platinum-based chemotherapy before ultimately recurring, frequently with chemoresistance6. Currently, the only way to determine if a patient is responsive to platinum-based chemotherapy is to treat them and wait up to six months to determine response.

Platinum-based chemotherapies work by binding to DNA to form inter- and intrastrand cisplatin-DNA adducts that block DNA synthesis, leading to cell cycle arrest and induction of apoptosis7. These DNA adducts are repaired by a variety of DNA repair mechanisms. These adducts are predominantly cleared by nucleotide excision repair (NER), which involves the nuclease heterodimer ERCC1-XPF8. Increased expression of ERCC1 has been identified as a predictor of cisplatin resistance9. Other DNA repair mechanisms involved in detecting and repairing cisplatin-DNA adducts include mismatch repair (MMR), non-homologous end joining (NHEJ), and homologous recombination repair (HRR)10. Deficiencies in these DNA repair pathways have also been implicated in predicting response to platinum therapies11. The proteins BRCA1 and BRCA2 are major proteins involved in maintaining the integrity of HRR processes12, and epithelial ovarian cancers with deficiencies in BRCA1/2 show increased sensitivity to platinum therapy13. Cisplatin is known to cause an accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), causing oxidative stress which, in addition to genotoxic stress, can trigger induction of apoptosis14. Another predominant mechanism of multidrug resistance, which is applicable to platinum resistance as well, is the upregulation of drug efflux or inhibition of drug influx, effectively decreasing the intracellular concentrations of the active molecule. In addition, a host of other oncogenic signaling pathways have been implicated in resistance to platinum, which are reviewed elsewhere15.

It is important that cell line models are accurately classified and reflect the molecular characteristics of their assigned subtypes. The cell lines SKOV3 and A2780 are the two most cited cell lines in OvCa studies, and while much of OvCa research is focused on HGSOC, these two subtypes have been determined to be poor models of HGSOC and are likely ovarian clear cell carcinoma (OCCC) and endometrioid ovarian carcinoma (EOC), respectively16,17. As classifications of ovarian cancer have evolved over the last two decades, multiple recent studies have sought to accurately classify commercially available OvCa cell lines based on their molecular characteristics16–19. However, there remains an unmet need in the field for a robust review of OvCa cell lines and their sensitivities to platinum therapies and robust model systems in which to examine naturally developed mechanisms of platinum resistance. Our study sought to define the platinum sensitivity of 36 OvCa cell lines and their corresponding genetic and gene expression signatures. Further, we leveraged seven isogenic platinum-resistant cell line pairs derived from four initially platinum sensitive counterparts to more robustly determine mechanisms. Our results indicate that common themes of platinum resistance are predominated by innate immunity/STAT activation, epithelial to mesenchymal transition and stemness, and platinum influx/efflux regulators. This work serves as a resource to the ovarian cancer community for more appropriate and well-defined platinum-responsiveness across multiple cell types in the aim that the field of platinum-responsiveness in ovarian cancer can be accelerated by using more appropriate model systems.

Methods

Cell culture

Cell lines used in this study and the media preparations used for culture are described in Supplemental Table 1. All cell lines were cultured in a humidified 37°C incubator with 5% CO2. All culture medium was supplemented with 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco). Cell line authentication was performed through the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Translational Research Initiatives in Pathology (TRIP) Lab. Mycoplasma testing was performed using the MycoAlert™ Mycoplasma Detection Kit (Lonza).

Drug dose response assay

Cells were plated in 50μL of the appropriate culture medium in a white opaque-walled 96-well tissue culture plate (Corning), and the number of cells plated per well for each cell line is detailed in Supplemental Table 1. The cells were allowed to attach for 24 hours before cisplatin (Cayman Chemical Company, cat. 13119) treatment, when the final volume in each well was brought to 100μL. Each cell line was tested at 10-doses that ranged between 400uM to 60nM depending on the sensitivity of the cell line. Cells were incubated on cisplatin treatment for 72-hours and analyzed by adding 50μL of CellTiter-Glo 2.0 reagent (Promega) to each well and incubated according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Luminescence was read using a BioTek Cytation 5 Cell Imaging Multi-mode Reader (Agilent). The cisplatin IC50 was determined for each cell line by normalizing treatments to the vehicle control and plotting the data in GraphPad Prism 9.

RNA-sequencing

Total RNA was extracted from cell pellets using a Quick DNA/RNA Miniprep Plus Kit (Zymo Research) per manufacturer’s instructions with the optional on-column DNase digestion and frozen at −80°C until use. RNA quality was assessed using RNA High Sensitivity ScreenTapes and Reagents and analyzed on a TapeStation 4200 instrument (Agilent). The RNA concentration for each sample was quantified using a Qubit™ RNA Broad Range Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s protocol and read on a Qubit™ Flex instrument. cDNA library prep was performed using the KAPA mRNA HyperPrep Kit (Roche) according to manufacturer’s directions with 300ng input and the following modifications: RNA fragmentation at 94°C for 6 minutes, 10 cycles of PCR amplification. Libraries were quantified using a Qubit™ 1x dsDNA High Sensitivity Kit and average fragment size determined using High Sensitivity D1000 ScreenTapes and Reagents and analyzed on a TapeStation 4200 instrument. Libraries were equimolarly pooled to 750pM loading concentration. Sequencing was performed on a NextSeq 1000 P2 100 cycle cartridge according to Illumina protocols. For all RNA-seq experiments, the same library pool was sequenced over multiple runs to achieve the necessary level of sequencing depth.

RNA-sequencing analysis

BCL to FASTQ conversion was performed on instrument using Illumina’s DRAGEN DRAGEN BCL Convert v3.8.4 for NextSeq 1000/2000. FASTQ files were then used as input into the NextFlow (v22.04.520) pipeline nf-core/rnaseq pipeline (v3.8.121) using genome GRCh38 for alignment and annotation. From pipeline reports of sequencing QC, aligned reads ranged from 25.7 – 40.6 million paired-end reads (mean: 34.4M, standard deviation +/− 3.3M).

Subsequent analysis was performed on the Salmon gene count matrix. Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed with the DESeq2::plotPCA command on Salmon counts transformed using DESeq2::vst to determine if any likely sample swaps existed, as well as to confirm the consensus subtypes inferred from the literature. Data was plotted with ggplot2.

Differential analysis was performed separately for each sensitive/resistant pair of cell lines, using DESeq2::DESeq with model design ~ Cell line + Replicate. Genes that were differentially expressed with an adjusted p value < 0.05 were designated as differentially up/down regulated genes. Subsequently, gene ontology was performed using clusterProfiler to determine which of the GO biological pathways were overrepresented in the differentially expressed genes (considering up/down regulated genes separately). Finally, Revigo’s rrvgo package was used to cluster and summarize the overrepresented pathways.

Copy number signature analysis

Copy number signatures were calculated using previously characterized methods and signatures22. We applied this to publicly available copy number data for all ovarian cancer cell lines from the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE) project, as obtained from DepMap. Specifically, ABSOLUTE copy number data (CCLE_ABSOLUTE_combined_20181227) was used, as this is the latest version of copy number data that provides segment means for all chromosome positions, rather than arm- or gene-level values. HS178T and OC316 were removed due to known contamination of these samples with other cell lines. The CCLE data was input into SigProfilerMatrixGeneratorR (v1.2)23, which produces a mutational matrix for the set of samples. This matrix was then the input for SigProfilerAssignmentR (v0.0.23)24 using the cosmic_fit() function. After this, copy number signatures 1 through 24, as specified by the Catalogue Of Somatic Mutations in Cancer (COSMIC), were grouped based on similar etiology as follows: changes in ploidy, chromothripsis associated amplification, focal loss of heterozygosity, chromosomal loss of heterozygosity, tandem duplication and homologous recombination deficiency, unknown, and profile oversegmentation. Weighted and unweighted copy number signatures were plotted; weighted signatures were generated by summing the unweighted scores and adjusting the fraction of contributions of each score out of 100% of the sum.

Oncoprints

Mutation and gene copy number data was obtained from cBioPortal using the “CCLE Broad, 2019” dataset. Ovarian cell lines were selected for OncoPrinter plotting. Genes selected were known homologous recombination deficiency genes (from review25). For the associated supplemental table, known allele fractions were obtained from DepMap for single nucleotide polymorphisms, as well as amplifications and deletions. Custom tracks were imported into the OncoPrinter tool, including our cisplatin and carboplatin IC50 values, fraction copy number altered and scarHRD scores (as described below).

scarHRD

Homologous recombination deficiency scores were calculated using the scarHRD R package (v0.1.1)26. ABSOLUTE copy number data (CCLE_ABSOLUTE_combined_20181227) was obtained from DepMap. scar_score() was run with the following parameters: reference = “grch37”, seqz=FALSE, ploidy = TRUE, chr.in.names = FALSE. The sum of the 3 HRD scores was used as the “scarHRD” score.

Ploidy and Fraction Copy Number Altered

Ploidy values for cell lines were obtained from DepMap ABSOLUTE analysis from the 20181227 dataset of the CCLE cell lines. Segtab data was used to calculate fraction copy number altered, as follows: sum of the length of regions with copy number alterations that Modal_Total_CN deviated from a value of 2 over the length of all regions measured.

Generation of Cisplatin resistant OVCAR3 and OVCAR4 cell lines

OVCAR3 and OVCAR4 isogenic platinum-resistant cell lines were generated by treating each cell line with 1uM cisplatin for 4 hours. After treatment, cells were provided with fresh medium and allowed to recover until the cells resumed their typical growth rate for at least two passages (typically about 2 weeks). The same treatment process was then repeated at the same concentration, and after recovery of the second treatment, the cisplatin dose was increased by 1uM and the process repeated. This process was continued over a period of 9 months. Two independent platinum resistant cell lines were generated for both the OVCAR3 and OVCAR4 lines designated ResA or ResB. The cells are not maintained in cisplatin containing medium.

Flow Cytometry

Cells were harvested using PBS, pH 7.4 + 5mM EDTA to preserve cell surface proteins. Cells were stained (1:50 dilution) with a CD133-APC conjugated antibody (Miltenyi Biotec, cat. 130-113-184) and ALDH activity assessed using an ALDEFLUOR kit (STEMCELL technologies) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Mouse IgG2b-APC (Miltenyi Biotec, cat. 130-122-932) and single stain controls were performed. Cells were imaged on a CytoFLEX benchtop cytometer (Beckmam Coulter) and data analyzed using FlowJo. A minimum of two independent replicates were performed for all flow cytometry, and the reported ranges reflect the consensus of the experimental values.

Tumorsphere Culture

Cells were incubated with tumorsphere medium consisting of Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium/F12 (Gibco), B27 supplement (Gibco), Human Recombinant Basic Fibroblast Growth Factor (STEMCELL technologies), Human Epidermal Growth Factor (PEPROTECH), Human Recombinant Insulin (Gibco) and Bovine Serum Albumin (Sigma) in an ultra-low attachment 6-well plate for 1–2 weeks. When tumorspheres were ready to be passaged, the contents of the wells were transferred to a 15mL conical tube using a 5mL serological pipet. The well was rinsed with 1000uL of tumorsphere medium. Cells were incubated for 10–15 minutes to allow them to settle to the bottom of the tube. The supernatant was removed without disturbing the pellets before 0.05% Trypsin-EDTA was added to break the tumorspheres apart. The tumorspheres were incubated for 3 minutes and then pipetted up and down a few times to help break up the tumorspheres. Media containing serum was utilized to inhibit trypsin activity and the cells were centrifuged for 5 minutes at 400rcf at room temperature. Supernatant was removed, fresh tumorsphere media was added, and the cells were plated in an ultra-low attachment 6-well plate.

Western Blotting

For cisplatin treated samples, cell lines were treated with their respective IC50s for 72 hours before being harvested into pellets. Proteins were extracted from cell lines using a 9M urea extraction buffer (9M urea, 4% CHAPS, 0.5% IPG buffer, 50mM DTT) according to the standard protocols. Fifteen μg protein was subsequently loaded per well onto NuPage 4–12% Bis-Tris gels (Invitrogen) and then transferred to PVDF membranes. Fluorescent detection blots were blocked in 5% skim milk in TBST for 1 hour at room temperature and subsequently probed for a housekeeping gene for 1 hour at room temperature. Following incubation, the blots were probed with a primary antibody for the protein of interest overnight at 4°C. The blots were incubated with secondary antibodies (LiCor #926-32211 and #926-68070) at 1:20,000 for 1 hour at room temperature and scanned on Li-Cor CLx. Primary antibodies: CD133 (Abcam ab19898), ALDH1 (BD Biosciences #611195), Actin (Thermo Fisher Scientific #MA5-15739), GAPDH (Cell Signaling Technology #5174S).

Wound Healing Assays

Cell lines were plated in their respective culture media in a 6-well tissue culture plate and were seeded at a density that would reach 70–80% confluence after 24 hours of incubation. The densities used range from 3×105 to 1×106 cells per well depending on the cell line and the rate of growth. Cells attached to the bottom of the plate for 24 hours before staining with 10uM final working concentration of CellTracker Green CMFDA dye (Invitrogen). After 30 minutes of incubation, a vertical line was manually scratched into the cell layer, using a 1000uL pipette tip. The scratch was imaged on a Cytation 5 with Biospa microscope at 4x magnification at 0hr, 24hr, 48hr, and 72hr. The width of the scratch was measured at each timepoint on the Cytation 5 with Biospa microscope (Agilent).

Resource Availability

Lead Contact –

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Dr. Jessica D. Lang (jessica.lang@wisc.edu).

Materials Availability –

Isogenic cell lines developed in this study are available for use by the community by direct contact with the corresponding author.

Data and code Availability –

Gene expression data will be made available through GEO at time of acceptance following peer review. Code used for our analysis is deposited at our GitHub repository: https://github.com/jessicalanglab/ovarian_cancer_cisplatin_response_manuscript/.

Results

Selection of OvCa cell line panel for analysis

We selected a panel of 36 ovarian cancer cell lines for this study, based on representativeness across a wide variety of ovarian cancer histotypes (Table 1). We extensively examined the literature on these cell lines, including the original literature on the tumors the cell lines were generated from, where available, and recent genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic analyses comparing cell lines and tumors of different histotypes (5–8) to determine the current consensus (Table 1). We made the decision not to include some extensively used cell lines, including A2780 and OVCAR5, as these cell lines have been characterized as potentially problematic in recent multi-omic publications. A2780 lacks characteristic TP53 mutations and high copy number alteration observed in HGSOC, the presumed subtype, and based on gene expression, clusters with lung and liver cancer cell lines16. Two other studies support the classification of A2780 as Endometrioid Carcinoma17,19. However, these studies did not compare A2780 to non-ovarian cancers. OVCAR5 was determined to be a gastrointestinal cancer origin based on gene expression and pathology review27. Therefore, to avoid drawing conclusions on cell lines not well representative of patient tumors, we decided to better characterize less used, but more characteristic cell lines.

Table 1.

Summary of cell line subtype classification from literature review.

| Cell Line | Tumor Type | Isolated From | Patient Treatment Pre-isolation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original Published Histology | Current Classification | |||

| 59M | Endometrioid carcinoma with clear cell components119 | Likely LGSC17,18, or possible HGSC16 | Ascites119 | None119 |

|

| ||||

| BIN67 | SCCOHT120,121 | SCCOHT122 | Metastatic pelvic nodule120 | Not specified |

|

| ||||

| CAOV3 | Adenocarcinoma123 | HGSOC16,17,19 | Primary tumor123 | Not specified |

|

| ||||

| CAOV4 | Adenocarcinoma123 | HGSOC16,17 | Fallopian tube metastasis123 | Not specified |

|

| ||||

| COV362 | Endometrioid124 | HGSOC16,17 | Pleural effusion124 | Not specified |

|

| ||||

| COV434 | Granulosa cell tumor124 | SCCOHT125 | Primary tumor124 | Not specified |

|

| ||||

| EFO21 | Serous adenocarcinoma126 | OCCC17 | Ascites126 | Not specified |

|

| ||||

| EFO27 | Serous papillary adenocarcinoma126 | Endometrioid17 | Solid omental metastasis126 | Not specified |

|

| ||||

| ES2 | Clear cell carcinoma127 | Likely LGSC17,18, or possible HGSC16, or Endometrioid19 Endometrioid | Not specified | Not specified |

|

| ||||

| IGROV1 | carcinoma with clear cell and undifferentiated components128 | Mixed endometrioid/OCCC16,17,19 | Primary tumor128 | Cobalt therapy to cervix and vagina128 |

|

| ||||

| JHOC5 | Clear cell adenocarcinoma129 | OCCC17,19 | Recurrent pelvic tumor129 | Cisplatin and cyclophosphamide129 |

|

| ||||

| JHOC9 | Clear cell carcinoma* | OCCC19 | Not specified | Not specified |

|

| ||||

| JHOS2 | Serous adenocarcinoma130 | HGSOC16,17 | Primary tumor130 | None130 |

|

| ||||

| JHOS4 | Serous cystadenocarcinoma* | HGSOC16,17 | Not specified | Not specified |

|

| ||||

| KURAMOCHI | Undifferentiated ovarian carcinoma131 | HGSOC16,17,19 | Not specified | Not specified |

|

| ||||

| OAW28 | Ovarian Adenocarcinoma119 | HGSOC16,17 | Ascites119 | Cisplatin, Melphalan119 |

|

| ||||

| OAW42 | Serous papillary cystadenocarcinoma | OCCC17 | Ascites129 | Cisplatin129 |

|

| ||||

| OV90 | Serous papillary cystadenocarcinoma 132 | Mucinous17,19 | Ascites132 | None32 |

|

| ||||

| OVCAR3 | Papillary adenocarcinoma133 | HGSOC16,17,19 | Ascites133 | Cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, cisplatin133 |

|

| ||||

| OVCAR4 | Adenocarcinoma134 | HGSOC16,17,19 | Ascites135 | Cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, cisplatin136 |

|

| ||||

| OVCAR8 | Adenocarcinoma134 | LGSC17

Possibly of lung origin16 |

Not specified | Carboplatin137 |

|

| ||||

| OVISE | Clear cell adenocarcinoma138,139 | OCCC17, possibly endometrioid19 | Pelvic bone metastasis139 | Cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, cisplatin138 |

|

| ||||

| OVK18 | Endometrioid carcinoma140 | Dedifferentiated Carcinoma/Endometrioid17,125 | Ascites140 | Unspecified chemotherapy and radiation140 |

|

| ||||

| OVMANA | Clear cell adenocarcinoma138 | OCCC17 | Primary tumor138 | Cisplatin138 |

|

| ||||

| OVSAHO | Serous papillary adenocarcinoma138 | HGSOC16,17 | Abdominal* metastasis138 | 5-fluorouracil, mitomycin C, chromomycin A3, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, cisplatin138 |

|

| ||||

| OVTOKO | Clear cell adenocarcinoma139 | OCCC17,19 | Splenic metastasis139 | Cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, cisplatin138 |

|

| ||||

| PEA1 | Adenocarcinoma39 | HGSOC40 | Pleural effusion39 | None39 |

|

| ||||

| PEA2 | Adenocarcinoma39 | HGSOC40 | Ascites39 | Cisplatin and prednimustine39 |

|

| ||||

| PEO1 | Serous adenocarcinoma39 | HGSOC141 | Ascites39 | 5-fluorouracil, cisplatin, chlorambucil39 |

|

| ||||

| PEO4 | Serous adenocarcinoma39 | HGSOC141 | Ascites39 | 5-fluorouracil, cisplatin, chlorambucil39 |

|

| ||||

| PEO6 | Serous adenocarcinoma39 | HGSOC141 | Ascites39 | 5-fluorouracil, cisplatin, chlorambucil39 |

|

| ||||

| RMGI | Clear cell 142 carcinoma142 | OCCC17 | Ascites142 | Not specified |

|

| ||||

| SKOV3 | Adenocarcinoma143 | OCCC17, possibly Endometrioid19 | Ascites143 | Thiotepa119 |

|

| ||||

| TOV112D | Endometrioid carcinoma32 | Dedifferentiated Carcinoma/Endometrioid17,19,125 | Primary tumor32 | None32 |

|

| ||||

| TOV21G | Clear cell 32 carcinoma32 | OCCC4,10 | Primary tumor32 | None32 |

|

| ||||

| TYKnu | Undifferentiated ovarian carcinoma144 | Likely LGSC17,18, or possible HGSC16 | Primary tumor144 | Not specified |

Detail not found in published data but stated in information provided by the cell line supplier.

Where literature was uncertain or disagreed, we also consulted DepMap’s Celligner to compare cell lines to TCGA tumors, which are predominantly HGSOC28. Further, we generated RNA-seq data in all 36 cell lines in a single pooled library to allow direct comparison of gene expression with no batch effects. Our final subtype calls from the literature review are supported by the Principal Component Analysis (PCA) clustering based on gene expression (Figure 1). The first principal component (PC1) largely discriminates HGSOC and OCCC from other subtypes, and PC2 separates HGSOC from OCCC. Of the 500 genes with the most variance in our dataset used to construct the PCA plot, top ranked features in PC1 included a number of genes biologically relevant to epithelial ovarian cancers. These genes include MUC16, PAX8, and many epithelial cell markers (EPCAM, KRT19, KRT7, KRT8, CDH6, CDH1). The top 20 contributors for each principal component are shown in Figure 1B.

Figure 1.

Principal component analysis (PCA) on gene expression across 36 ovarian cancer cell lines included in the study. (A) PCA plot of the first two principal components (PC1 and PC2). Color coding represents the literature-supported subtype classifications. Subtype abbreviations are: DDEC = Dedifferentiated Endometrial Carcinoma, EOC = Endometrioid Carcinoma, HGSOC = High-Grade Serous Ovarian Carcinoma, LGSOC = Low-Grade Serous Ovarian Carcinoma, MUC = Mucinous, OCCC = Ovarian Clear Cell Carcinoma, SCCOHT = Small Cell Carcinoma of the Ovary, Hypercalcemic Type. (B) Top 20 contributing genes to each of the first two PCs. Loadings were ranked by absolute value for each PC, and the corresponding loading rank for each gene in the reciprocal principal component is shown.

Copy number signature analysis

We performed copy number signature analysis on publicly available genomic copy number data from the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia29 to examine patterns of copy number variant etiologies, as ovarian cancers, and in particular HGSOCs, have high focal copy number variation30,31. From this analysis, a large proportion of the attributed copy number signatures were of unknown origin (CN18-21). The second most frequent etiology was from signatures that indicate focal loss of heterozygosity (LOH; CN9, CN10, and CN12), which occurred most frequently in cell lines presumed to be HGSOC, but also in OCCC cell lines SKOV3, EFO21, and JHOC5, LGSOC cell lines OVCAR8, 59M, and TYKNU, and Mucinous cell lines MCAS and OV90.

Homologous recombination deficiency (HRD) signatures were found in twelve cell lines examined. Of these, seven of them (58%; SNU119, OVCAR4, 59M, KURAMOCHI, OVISE, DOV13, and SNU8) lacked biallelic loss in genes attributed to HRD (Figure 2 and Supplemental Table 2), and occurred in various different subtypes. Scar HRD scores were also applied to the copy number data, and generally overlapped cell lines with HRD called from the copy number signature analysis (Supplemental Figure 1A and Supplemental Table 2). CN1 corresponds to diploidy, and CN2 corresponds to tetraploidy; these signatures very closely aligned to reported ploidy of the cell lines (Supplemental Figure 1B and Supplemental Table 2). HGSOC cell lines had a surprisingly low frequency of tetraploidy-associated signatures (15%), suggesting that copy number signature analysis did not perform well for this subtype, as this contradicts the established etiology of HGSOC. Chromothripsis signatures were infrequently found in ovarian cancer cell lines, and were limited to HGSOC and OCCC cell lines SNU119, EFO21, RMGI, DOV13, and CAOV4. Chromosomal LOH was only found in TOV112D, where it was the only attributed copy number signature. These data are low confidence, as these two cell lines had the lowest total assignments of activities (Supplemental Fig 1C). In fact, TOV112D has been described to be hyperdiploid, with 52 chromosomes, including gains in all or parts of chromosomes X, 1, 2, 9, 12, and 15 and 1732, and has not previously been described to have chromosomal LOH. However, the reported ploidy score for TOV112D indicates a ploidy of 1 (Supplemental Figure 1B and Supplemental Table 2).

Figure 2.

Copy number signature analysis and homologous recombination deficiency (HRD) gene oncoprint for ovarian cancer cell lines in CCLE dataset. The stacked bar plot (top panel) summarizes the weighted contributions of each copy number signature to the overall genomic profile. Copy number signatures are colored by shared etiologies, as described in figure legend to the right. The oncoprint (bottom panel) displays known mutations to HRD genes corresponding to the cell lines in the top panel. IC50 values for cisplatin and carboplatin in our own assays are also shown as a bar graph, as well as calculated HRD score (HRD.sum) and fraction genome altered (fraction_CNV). Percentages on the left summarize the fraction of cell lines carrying an alteration to each gene. Subtype is summarized based on our literature review.

Sensitivity of ovarian cancer cell line panel to platinum-based chemotherapies

For our panel of 36 cell lines, we evaluated the platinum sensitivity of all cell lines by determining the 72-hour IC50 values for both cisplatin and carboplatin (Figure 3A & 3B, Supplemental Table 3A). The majority of our cell lines are classified as either HGSOC, LGSOC, or OCCC, and each of those subtypes displayed a broad range of sensitivity to platinum reagents. Between cisplatin and carboplatin, trends in sensitivity generally were similar. For determining relative platinum sensitivity for the purposes of downstream assays, the cells were deemed platinum sensitive within a subtype if their cisplatin 72-hour IC50 fell below the SEM, intermediate if it fell within the SEM, and resistant if above the SEM. The range of values for the cell lines determined to be sensitive or intermediate is consistent with clinical Cmax: 58.4–87.4uM for 15–30 minutes of carboplatin infusion at AUC 5–633–35, and 4.1uM and 6.6uM for 1 and 2 hour infusions with cisplatin at 50–80 mg/m2 36–38.

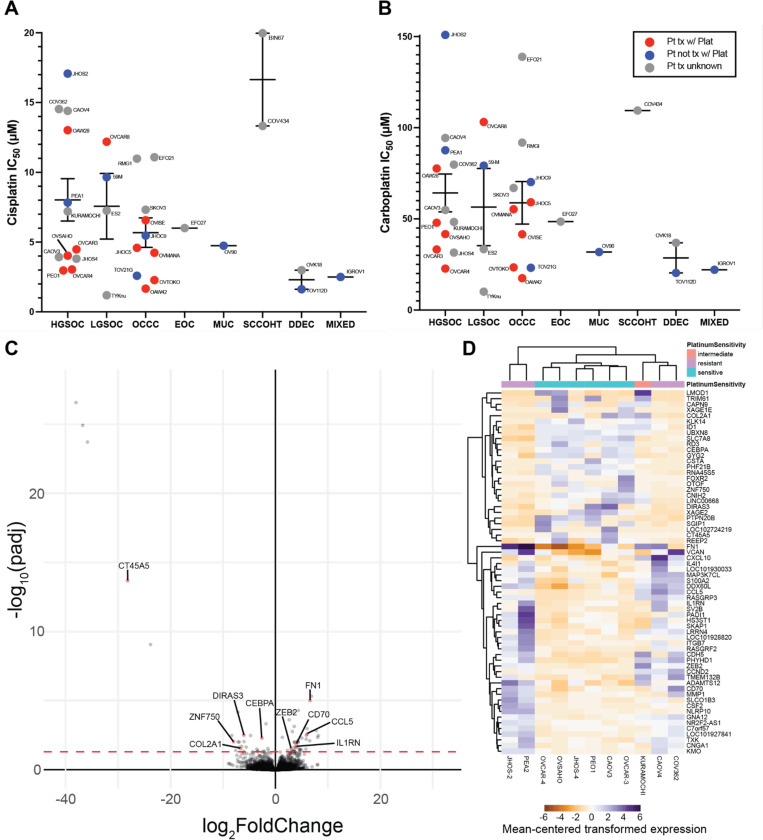

Figure 3.

Sensitivity of ovarian cancer cell line panel to platinum-based chemotherapies and resistance-associated gene expression signatures of HGSOC. (A) Cisplatin and (B) carboplatin IC50 values for 33 ovarian cancer cell lines of various subtypes. Line and error bars for each subtype show the mean +/− standard error of the mean. (C) Volcano plot and (D) heat map showing differentially expressed genes between HGSOC cell lines based on platinum sensitive, intermediate, and resistant classifications from our data in (A) and (B). Genes with demonstrated roles in platinum-resistance in the literature are labeled in the volcano plot. Values in the heatmap for each gene are centered on the mean of the transformed expression across the eleven cell lines.

High-grade serous ovarian carcinoma gene expression associated with resistance

Based on the established in vitro sensitivity to cisplatin and carboplatin, we used the HGSOC cell lines subsetted into platinum resistant (JHOS-2, PEA2, CAOV4, COV362), intermediate (KURAMOCHI), and sensitive (OVCAR-3, OVCAR-4, OVSAHO, JHOS-4, PEO1, CAOV3) groups to perform differential expression analysis. Only the HGSOC subtype was used for differential expression analysis to avoid finding differentially expressed genes that were related to subtype variations instead of resistance. This resulted in 64 differentially expressed genes, with 37 up-regulated and 27 down-regulated (Figure 3C, Supplemental Table 3B). While some genes were consistently up or down in their respective response groups, others were only up or down in a subset of cell lines, resulting in clustering of CAOV4 and COV362 closer to sensitive cell lines (Figure 3D).

Of the 56 differentially expressed genes, ten of these had some prior evidence of connection to platinum-resistance. We excluded genes associated with adaptive immune responses, as the conditions under which platinum-resistance was examined in our experiments lacked immune components. The five upregulated genes were CCL5, FN1, CD70, IL1RN, and ZEB2, and the five downregulated genes were CEBPA, DIRAS3, COL2A1, ZNF750, and CT45A5.

Differential expression of HGSOC isogenic platinum-resistant pairs

To further explore genes related to platinum resistance, we generated isogenic platinum-resistant pairs of the HGSOC cell lines OVCAR3 and OVCAR4 through pulse-treatment of the cells with cisplatin until the IC50 value for the cell line increased at least 3-fold. Two independent isogenic pairs were generated for both cell lines (OVCAR3/4 ResA & ResB). In addition, commercially available isogenic platinum sensitive and resistant HGSOC cell lines derived from the same patient were utilized (PEO1/4/6 and PEA1/2)39. Collectively, the resistant pairs showed a 1.7–4.8-fold increase in cisplatin resistance (Figure 4A, Supplemental Figure 2A, and Supplemental Table 3A) and a 1.3–4.5-fold increase in carboplatin resistance (Figure 4B and Supplemental Table 3A). We performed RNA-seq on the parental sensitive and isogenic resistant pairs in triplicate to determine gene expression changes associated with resistance in a single batch experiment. PCA demonstrates that most differences in gene expression are attributed to unique characteristics of the parental cell lines, rather than from overall shared gene expression influences on platinum resistance (Supplemental Figure 2B). There was not a clear set of genes contributing the most to either dimension (data not shown). Gene ontology analysis revealed a number of resistance-related mechanisms (Figure 4C). Many of the identified pathways were not shared across isogenic pairs, and instead were either only found in a few pairs, or were differentially enriched in different pairs.

Figure 4.

Characterization of isogenic platinum resistant HGSOC cell lines. (A) IC50 values for cisplatin and (B) carboplatin comparing the parental platinum sensitive cell line (left) to its isogenic resistant pair(s) (right). Line and error bars for the sensitive cell lines and resistant pairs show mean +/− standard error of the mean. (C) Gene ontology analysis showing overrepresented pathways in the differentially expressed genes found when comparing the sensitive and resistant isogenic pairs individually. Gene ontology results are aggregated by semantic space to shared pathways, where the number of individual gene ontology terms is indicated in the label in parentheses. Each isogenic pair is color-coded independently, as indicated in the legend. (D) Wound healing assay for the PEA1/PEA2 isogenic pair (N = 3 independent replicates). Error bars represent standard deviation. * indicates p-value < 0.05 in paired t-tests and ns indicates non-significant p-value > 0.05.

We layered publicly available annotation database15 of genes implicated in platinum resistance on volcano plots in our isogenic pairs to determine whether there was a predominance of key resistance pathways (Supplemental Figure 3C). The seven major, non-mutually exclusive, resistance pathways were oncogenic signaling, DNA damage repair, apoptosis inhibition, extracellular matrix modifications, platinum influx/efflux, metabolic changes, and hypoxia responses. At the gene expression level, there is predominance of oncogenic signaling and extracellular matrix modifications as most strongly modified in the direction of contribution to resistance, compared to other mechanism categories. Generally, individual isogenic resistant cell lines from the same parental cell line had more diversity in gene expression contributions to resistance between individual resistant lines than the clinical pair (PEO4/6). This is consistent with clonal ancestry analyses on PEO4 and PEO6 concluding that these were derived from a shared clone40.

Of the most dynamically expressed genes known to be associated with platinum resistance, a predominance of Wnt signaling, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), intrinsic inflammatory responses, and platinum influx/efflux were predominant across models. Wnt signaling and EMT related gene expression changes include SOX17, CASP14, KRT5 in OVCAR3 ResB, ANKRD1, MMP10 in OVCAR4 ResA, and EPCAM in PEA2. STAT signaling and innate inflammation-related changes include CD44 in OVCAR3 ResB and OVCAR4 ResB, BIRC3 in OVCAR4 ResA, CXCL12, STAT5B and IL6 in OVCAR4 ResB, and ERBB4, CCL5 in PEO4 and PEO6. Changes to platinum influx and efflux occurred to ABCC3 in OVCAR3 ResB and OVCAR4 ResB, ANXA4, ATP7A in OVCAR4 ResA, and SLC22A3 in PEO4 and PEO6.

Other shared differential gene expression with the highest magnitude of change included GPRC5A (OVCAR3 ResA, PEA2), MAL (OVCAR3 ResA, OVCAR3 ResB, PEA2), S100A9 (OVCAR3 ResB, OVCAR4 ResB, PEA2), SUSD2 (OVCAR3 ResB, PEO4), CLU (PEO4, PEO6), and THBS1 (PEO4, PEO6). 274 genes were differentially expressed in the same direction in five or more isogenic pairs, with 137 up and 137 down. Notable upregulated genes include HDAC6, IER5, IL6, IFIT2, and ITGB8.

Since wound healing was a significant pathway in a few platinum-resistant HGSOC cell lines, we performed scratch assays isogenic platinum-resistant cell lines. Scratch closure was significantly increased for PEA2, OVCAR3 ResA (24h), OVCAR3 ResB (72h) (Figure 4D and Supplemental Figure 4). The most prominent change was in PEA2, which was consistent with the increase in gene ontology pathway enrichment scores for this cell line (Figure 4C). OVCAR4 ResB had significant early delay in scratch closure.

Stemness markers in isogenic resistant pairs

As cancer stem cell or quiescent states have been implicated in the development of resistance to platinum-based chemotherapy, we examined whether the isogenic platinum-resistant cell lines exhibited more stemness markers compared to their sensitive counterpart. Differential expression analysis of isogenic pairs revealed that PEO4 and PEO6 had increased “regulation of hair follicle development”, PEO6 had decreased “regulation of stem cell proliferation”, and PEA2 and OVCAR4 ResA had increased “regulation of stem cell proliferation” (Figure 4C), suggesting involvement of these pathways in cisplatin resistance in these pairs. We examined expression of the two most reliable markers of ovarian cancer stemness phenotype, CD133 and Aldehyde Dehydrogenase (ALDH) by both western blot and flow cytometry in all of our isogenic pairs (Table 2, Supplemental Figures 5 & 6). While we anticipated the resistant cell lines having higher expression of these marks, notably, they were nearly always lower in the resistant cell lines compared to their sensitive counterparts. This was also consistent with the ability of each cell line to form tumorspheres. PEO1 had high CD133 expression and ALDH activity, but PEO4 had markedly decreased expression and activity, and could not form tumorspheres. OVCAR3 had higher tumorsphere formation ability than resistant cell line counterparts, which seems to be most correlated with a decrease in CD133 expression for OVCAR3 ResA and a decrease in ALDH activity for OVCAR4 ResB. OVCAR4 resistant clones had partial to complete loss of CD133, but minimal change to ALDH activity, but tumorsphere formation was largely unaffected. PEA2 resistant cells were the only isogenic resistant line to demonstrate increased tumorsphere formation, which correlates with increased ALDH activity in this cell line. Overall, isogenic platinum-resistant cell lines appear to be poor models of stemness as a feature promoting resistance.

Table 2.

Summary of stemness markers and phenotypes for platinum-resistant isogenic pair cell lines. For western blot, relative expression of CD133 and ALDH1 are shown.

| Cell Line | Western Blot | Flow Cytometry | Tumorspheres | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD133 | ALDH1 | CD133 | ALDEFLUOR | ||

| PEO1 | +++ | − | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| PEO4 | − | − | + | + | − |

| PEA1 | − | − | + | + | + |

| PEA2 | − | − | + | ++ | +++ |

| OVCAR3 | + | +++ | + | + | +++ |

| OVCAR3ResA | − | +++ | − | + | + |

| OVCAR3ResB | + | ++ | + | − | + |

| OVCAR4 | +++ | + | +++ | + | +++ |

| OVCAR4ResA | ++ | + | ++ | + | +++ |

| OVCAR4ResB | + | − | + | + | +++ |

For flow cytometry: − less than 2x negative control, + 2x negative control-30% positive cells, ++ 30%–70%, +++ >70%. For tumorspheres: − for no tumorsphere formation, + for no tumorspheres surviving passaging, +++ for tumorspheres forming for at least 2 passages.

Discussion

Ovarian cancer cell lines have more recently come under scrutiny for the suitability of representation of commonly used models for the current subtype classifications. In this study, we contribute to the growing body of literature on reclassification using our gene expression data from a single-batch assay of 36 cell lines. Our RNA-seq data recapitulates the most recent reclassifications of cell lines16–19. Genes that contributed to the most variation between subtypes included known biomarkers and master regulators of ovarian cancer subtypes (MUC16 and PAX8) and many keratin and cadherin genes (KRT19, KRT7, KRT8, CDH6, and CDH1). We further examined copy number signatures, as ovarian cancer subtypes differ substantially in their chromosomal instability and aberrations. On one end of the spectrum, HGSOCs have exceptionally high copy number alteration30,31, whereas SCCOHT are genomically quiescent at both the copy number and mutation standpoint41. Copy number signatures have been previously applied to TCGA and other tumor data, but have not yet been reported for cell lines. Ovarian cell line copy number signature analysis identified heterogeneous etiologies even within a subtype. Yet, focal copy number signatures were common features in HGSOC cell lines, which aligns with current understanding that subsequent to TP53 loss in HGSOC, early genomic instability results in genome doubling and subsequent focal copy number alterations. However, not all HGSOC cell lines displayed signatures or ploidy estimates consistent with genome doubling. Outliers to the genome doubling hypothesis include JHOS4, COV504, CAOV3, RMUGS, COV362, JHOS2, OVKATE, JHOM2B, and COLO704, which appear to be near-diploid by these estimates. Further, the HRD-related copy number signature is generally associated with the computed scarHRD score, but some discrepant cell lines were found between these predictors. CAOV3, JHOS4, and OAW28 had high scarHRD scores, but no HRD copy number signature, whereas OVISE, DOV13, and SNU8 had low scarHRD scores, but presence of HRD copy number signatures. Notably in these discrepant cell lines, the cell lines with high scarHRD had deleterious mutations to BRCA genes (either deletions or truncating mutations), but those with presence of only the HRD copy number signature were wildtype for BRCA genes or carried unknown missense mutations or amplifications.

Ovarian cancer cell lines have long been used to study therapeutic response, yet a comprehensive examination of platinum-response in equivalent experimental setup has not been robustly reported in this many cell line models. To our knowledge, the most similar study examined 39 cell lines for three platinum compounds, but this study only reported visualization of relative sensitivity in a heatmap format, and did not contextualize sensitivity to clinically achievable doses42. We robustly examined response to both cisplatin and carboplatin using the same method across 36 different ovarian cancer cell lines that were examined by RNA-seq analysis. IC50s generally diverged into values that were either above or below the established Cmax of cisplatin and carboplatin. Thus we are confident that there is a clinically translatable resistance level in the models we have examined. Interestingly, cell lines of certain subtypes displayed variable platinum sensitivity. HGSOC and LGSOC displayed a wide range of sensitivity, with cell lines spanning platinum doses above and below the Cmax. EOC, OCCC, Mixed, and DDEC cell lines were largely sensitive to platinum. SCCOHT cell lines were exclusively resistant to platinum, which is consistent with the clinical observations that high-dose chemotherapy is most effective for these patients43.

Within HGSOC cell lines, of which we had twelve that clustered well together, we performed differential expression analysis and found only a select set of genes previously implicated in platinum resistance. The five upregulated genes were CCL5, FN1, CD70, IL1RN, and ZEB2. While CCL5 is generally a chemoattractant to recruit immune cells, it has been implicated in ovarian cancer resistance through activation of pathways in cells directly, either through local secretion that causes STAT2 and PI3K/Akt activation44 or through activation subsequent to BRCA1 inactivation which can lead to STING activation to promote inflammation45. FN1 is a fibronectin glycoprotein that has been implicated in inducing cisplatin resistance and correlating with patient outcome in ovarian and other cancers46–49. CD70 is a TNF-family cytokine that is typically found on activated T and B cells, but is known to be over-expressed in platinum-resistant A2780 cells50 and is associated with poor survival and chemoresistance51. IL1RN is an interleukin 1 family member that inhibits IL-1. Lower abundance of IL1RN in ascites is associated with improved overall survival outcomes52. ZEB2, a transcriptional repressor, has been associated with epithelial to mesenchymal transition in ovarian cancer53 and is re-expressed in models of chemoresistant ovarian cancer54.

The five downregulated genes were CEBPA, DIRAS3, COL2A1, ZNF750, and CT45A5. Low expression of the CEBPA transcription factor is associated with poorer overall survival and growth and progression phenotypes in ovarian cancer cell lines, and has been shown to repress WNT signaling55. DIRAS3 is a member of the Ras super-family that is an imprinted tumor suppressor gene. Its loss, which occurs in more than half of ovarian cancers, has been associated with reduced autophagy and cisplatin resistance56,57. COL2A1, a component of type II collagen, has been shown to positively correlate with higher sensitivity to platinum in HGSOC58. ZNF750 is a transcription factor normally associated with epidermis differentiation whose expression is positively correlated with increased sensitivity to chemoradiotherapy in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma59. While it has not been implicated in ovarian cancer, it is consistent with a loss of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) phenotype that is associated with chemoresistance. CT45A5 is one of a cluster of homologous genes that encode the CT45 cancer/testis antigen. CT45 has been implicated in inhibiting DNA damage repair and is more highly expressed in platinum-sensitive tumors59.

In addition, we used seven total platinum-resistant isogenic pairs, including three well established isogenic pairs from clinical platinum resistance39, and four novel resistant cell lines derived from pulse-treatment of platinum-sensitive OVCAR3 and OVCAR4 cells to cisplatin. The choice of pulse-treatment was based on previous work that demonstrates that this most closely recapitulates selection pressure observed in patients60. Again, we found a predominance of innate immunity/STAT activation, EMT, and platinum influx/efflux regulators in the differentially expressed genes between resistant and sensitive cell lines. Wnt signaling and EMT related gene expression changes were predominantly found in OVCAR3 ResB, OVCAR4 ResA and PEA2. SOX17, CASP14, KRT5, ANKRD1, MMP10, EPCAM. SOX17, which is decreased in some resistant lines, is notable because it has been proposed to be a master regulator in ovarian cancer61 and inhibits WNT3A-stimulated transcription through degradation of beta-catenin62. Downregulation of SOX17 also allows higher expression of DNA damage repair genes63, and its expression is generally associated with increased cisplatin sensitivity63–65 though this has not been described for ovarian cancers. CASP14 and KRT5 are associated with keratinization, and have been implicated in resistance to lung and ovarian cancers66–68. ANKRD1, a transcription factor target of TGF-beta and Wnt signaling is necessary for resistance to platinum, and its expression is associated with poorer outcomes in ovarian cancer69. Endoplasmic reticulum stress has also been posited to play a role in ANKRD1-related platinum resistance70. MMP10, a matrix metalloproteinase that degrades gelatins and fibronectin is over-expressed in platinum-resistant A2780 cells71 and is also thought to activate canonical Wnt signaling through preventing Wnt5A-mediated noncanonical signaling72. EPCAM, an epithelial adhesion protein, has an intracellular domain shown to induce Wnt signaling when cleaved. Expression of EPCAM is increased in platinum-resistance and associated with EMT73, and high expression is associated with poorer prognosis74, however this is not supported by TCGA data75.

STAT signaling and innate inflammation-related changes were mostly found in OVCAR3 ResB, OVCAR4 ResA, OVCAR4 ResB, PEO4, and PEO6. CD44, IL6, BIRC3, CXCL12, STAT5B, ERBB4, CCL5 were notable STAT-related gene expression changes. CD44, a receptor for hyaluronic acid, is a cancer stem cell marker frequently associated with chemoresistance that can activate STAT3. Autocrine signaling of the interleukin IL6 has been associated with platinum resistance in many cancers76–80, including ovarian cancer81. IL6 upregulates HIF-1alpha through STAT3 activation82. BIRC3, a E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase that regulates NFkB activation and anti-apoptotic caspase regulation can be induced by IL-6 treatment in ovarian cancer cells83. Over-expression of BIRC3 is observed in platinum-resistant A2780 cells84 and in response to RUNX3 OE in A2780, which occurs in resistant derivatives85. CXCL12, also known as Stromal cell-derived factor 1 is a chemokine that activates CXCR4 and increases intracellular calcium and chemotaxis. CXCL12 treatment of SKOV3 makes them more resistant to cisplatin86 and induces Wnt/beta-catenin pathways and EMT87. In lung cancer, CXCL12 activates JAK2/STAT3 signaling to mediate resistance to cisplatin88. STAT5B, a transcription factor effector of inflammatory signaling, can be activated downstream of ERBB4 and IL-11 to induce resistance to platinum89,90 and can be targeted with the STAT5 inhibitor dasatinib to restore sensitivity to platinum91. ERBB4, an epithelial growth factor receptor family member, has also been shown to activate Ras/MEK/ERK, PI3K/AKT, STAT3 and STAT5, with high expression associated with poor survival in ovarian cancer92. Chemokine CCL5 has been demonstrated to desensitize ovarian cancer cells to cisplatin through expansion of cancer stem cells93, and promotes resistance to cisplatin through STAT3 and PI3K/AKT activation44.

Changes to platinum influx and efflux were frequent in OVCAR3 ResB, OVCAR4 ResA, OVCAR4 ResB, PEO4, and PEO6. ABCC3, ANXA4, ATP7A, and SLC22A3 were particularly notable examples of platinum influx/efflux changes. ABCC3 is a well known multidrug transporter channel involved in the efflux of many drugs out of cells. ANXA4, or Annexin A4, promotes membrane fusion and exocytosis and is involved in platinum resistance in OCCC94,95. Notably, we observe ANXA4 increased in HGSOC in this study. ATP7A is a copper-transporting ATPase 2 that exports copper out of cells and has also been shown to mediate resistance to platinum agents96,97. Cation transporter SLC22A3 is involved in influx of cisplatin into cell, but may not transport carboplatin1691455998. Decreased SLC22A3 expression is associated with poorer prognosis99,100.

Other genes with shared differential gene expression across multiple models with high or frequently shared differential expression were GPRC5A, MAL, S100A9, SUSD2, HDAC6, IER5, IFIT2, and ITGB8. GPRC5A is a marker of poor outcome in HGSOC101. MAL, which is involved in vesicular trafficking and lipid raft organization, is generally associated with resistance and poor outcomes102,103, and MAL promoter hypomethylation is associated with increased expression of MAL in resistant tumors104. S100A9 is more highly expressed in resistant tumors105–107, and its increase is evident following acute treatment with neoadjuvant chemotherapy108. Sushi-domain containing membrane protein receptor SUSD2’s expression promotes chemotherapy resistance109. HDAC6, which was upregulated in all isogenic pairs except PEA2 and OVCAR3 ResB is a histone deacetylase that interacts with DNA damage repair factors in HGSOC110. High HDAC6 is associated with poor prognosis and chemoresistance in patients with HGSOC111. IER5, whose expression was up in all but the OVCAR4 ResA and ResB lines, is associated with poor disease-free intervals and has been shown to be induced by platinum112. IFIT2, upregulated in all but PEA2 and OVCAR3 ResB, has been associated with chemoresistance previously in HGSOC113. Its expression is induced by interferon signaling. ITGB8, an integrin beta subunit, was upregulated in all but OVCAR3 ResA and ResB and has been shown to be regulated by noncoding RNAs to mediate stemness and therapy response114,115.

While we anticipated seeing that resistant cells would have higher positivity for markers of stemness, this was generally not the case, indicating that stemness phenotypes must be a transient state through which resistant cells pass, not a selected trait. This is consistent with the persister cell hypothesis116. Notably, as described above, despite the lack of clear canonical markers of stemness phenotype and function, we do see some gene expression changes to EMT and stemness genes that may contribute to resistance. Our overall conclusion from the stemness assays is that isogenic platinum-resistant cell lines are not a good model of the transitory state of platinum resistance development, but represent the states that likely exist in a steady-state resistant population.

We note some limitations of the design of our study. It is known from other studies that immune responses and stromal interactions are quite important for overall response of tumors to therapy, and we recognize that these were inadequately represented by our study. While we made attempts to compare the cell lines representing diverse subtypes of ovarian cancer to clinical tumor RNA-seq data, a comprehensive dataset including a representative set of each of these tumors was not publicly available. Inspired by CASCAM117, we attempted to batch correct several subtype-specific datasets and integrate with our own data using and ComBat118, but we found that we were unable to resolve the clustering by dataset without sacrificing clustering by ovarian cancer subtype. Since most studies are predominated by a single subtype, batch correction not only normalized experiment-to-experiment variability in datasets, but also the intersubtype variability in expression (i.e. the gene expression that contributes to subtype identity). Future studies with RNA-seq data evenly representing different ovarian cancer subtypes would aid in building a foundation upon which we could better assess cell lines against patient tumor subtypes.

Our data suggest multi-mechanism contributions to resistance even within a single resistant cell line that continue to be a challenge to tease apart. Future work will quantitatively determine individual mechanisms to resistance. Yet, the robustness of the cell lines chosen and the number of isogenic pairs examined is a strength compared to similar studies on gene expression changes with resistance in ovarian cancer cell models, which have mostly relied on A2780 and SKOV3 derivatives. Further, applying the differential gene expression changes to a clinical transcriptomic dataset with well-annotated platinum-free intervals (PFI) would greatly improve the biomarker implications of our findings, but even TCGA lacks robust numbers of tumors with both RNA-seq and PFI information available (on the order of 40 tumors). In the future, we plan to build on our gene expression networks through the integration of shared master regulators and epigenetic organization to develop a more integrated picture of upstream targets with pleiotropic effects that converge to promote resistance.

Acknowledgements

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number R00CA234391 to JDL.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Siegel R. L., Miller K. D., Wagle N. S. & Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA A Cancer J Clinicians 73, 17–48 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herzog T. J. & Armstrong D. K. First-line chemotherapy for advanced (stage III or IV) epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, and peritoneal cancer. in UpToDate (ed. Post T. W.) (UpToDate, Waltham, MA, 2023). [Google Scholar]

- 3.SEER*Explorer: An interactive website for SEER cancer statistics. Surveillance Research Program, National Cancer Institute https://seer.cancer.gov/statistics-network/explorer/ (2023).

- 4.Oza A. M. et al. Progression-free survival in advanced ovarian cancer: a Canadian review and expert panel perspective. Curr Oncol 18 Suppl 2, S20–27 (2011). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wagner U. et al. Final overall survival results of phase III GCIG CALYPSO trial of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin and carboplatin vs paclitaxel and carboplatin in platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer patients. Br J Cancer 107, 588–591 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giornelli G. H. Management of relapsed ovarian cancer: a review. SpringerPlus 5, 1197 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tchounwou P. B., Dasari S., Noubissi F. K., Ray P. & Kumar S. Advances in Our Understanding of the Molecular Mechanisms of Action of Cisplatin in Cancer Therapy. J Exp Pharmacol 13, 303–328 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferry K. V., Hamilton T. C. & Johnson S. W. Increased nucleotide excision repair in cisplatin-resistant ovarian cancer cells: role of ERCC1-XPF. Biochem Pharmacol 60, 1305–1313 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Du P., Wang Y., Chen L., Gan Y. & Wu Q. High ERCC1 expression is associated with platinum-resistance, but not survival in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer. Oncol Lett 12, 857–862 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rocha C. R. R., Silva M. M., Quinet A., Cabral-Neto J. B. & Menck C. F. M. DNA repair pathways and cisplatin resistance: an intimate relationship. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 73, e478s (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stefanou D. T., Souliotis V. L., Zakopoulou R., Liontos M. & Bamias A. DNA Damage Repair: Predictor of Platinum Efficacy in Ovarian Cancer? Biomedicines 10, 82 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Venkitaraman A. R. Cancer susceptibility and the functions of BRCA1 and BRCA2. Cell 108, 171–182 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dann R. B. et al. BRCA1/2 mutations and expression: response to platinum chemotherapy in patients with advanced stage epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol 125, 677–682 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Previati M. et al. Cisplatin-induced apoptosis in human promyelocytic leukemia cells. Int J Mol Med 18, 511–516 (2006). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang D. et al. A highly annotated database of genes associated with platinum resistance in cancer. Oncogene 40, 6395–6405 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Domcke S., Sinha R., Levine D. A., Sander C. & Schultz N. Evaluating cell lines as tumour models by comparison of genomic profiles. Nat Commun 4, 2126 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barnes B. M. et al. Distinct transcriptional programs stratify ovarian cancer cell lines into the five major histological subtypes. Genome Med 13, 140 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coscia F. et al. Integrative proteomic profiling of ovarian cancer cell lines reveals precursor cell associated proteins and functional status. Nat Commun 7, 12645 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anglesio M. S. et al. Type-specific cell line models for type-specific ovarian cancer research. PLoS One 8, e72162 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Di Tommaso P. et al. Nextflow enables reproducible computational workflows. Nat Biotechnol 35, 316–319 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ewels P. A. et al. The nf-core framework for community-curated bioinformatics pipelines. Nat Biotechnol 38, 276–278 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steele C. D. et al. Signatures of copy number alterations in human cancer. Nature 606, 984–991 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bergstrom E. N. et al. SigProfilerMatrixGenerator: a tool for visualizing and exploring patterns of small mutational events. BMC Genomics 20, 685 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Díaz-Gay M. et al. Assigning mutational signatures to individual samples and individual somatic mutations with SigProfilerAssignment. Bioinformatics 39, btad756 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamamoto H. & Hirasawa A. Homologous Recombination Deficiencies and Hereditary Tumors. Int J Mol Sci 23, 348 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sztupinszki Z. et al. Migrating the SNP array-based homologous recombination deficiency measures to next generation sequencing data of breast cancer. NPJ Breast Cancer 4, 16 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blayney J. K. et al. Prior knowledge transfer across transcriptional data sets and technologies using compositional statistics yields new mislabelled ovarian cell line. Nucleic Acids Res 44, e137 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Warren A. et al. Global computational alignment of tumor and cell line transcriptional profiles. Nat Commun 12, 22 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ghandi M. et al. Next-generation characterization of the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia. Nature 569, 503–508 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harbers L. et al. Somatic Copy Number Alterations in Human Cancers: An Analysis of Publicly Available Data From The Cancer Genome Atlas. Front Oncol 11, 700568 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zack T. I. et al. Pan-cancer patterns of somatic copy number alteration. Nat Genet 45, 1134–1140 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Provencher D. M. et al. Characterization of four novel epithelial ovarian cancer cell lines. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim 36, 357–361 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oguri S. et al. Clinical pharmacokinetics of carboplatin. J Clin Pharmacol 28, 208–215 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gaver R. C. et al. The disposition of carboplatin in ovarian cancer patients. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 22, 263–270 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Joerger M. et al. Population pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of paclitaxel and carboplatin in ovarian cancer patients: a study by the European organization for research and treatment of cancer-pharmacology and molecular mechanisms group and new drug development group. Clin Cancer Res 13, 6410–6418 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nagai N. et al. Population pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of cisplatin in patients with cancer: analysis with the NONMEM program. J Clin Pharmacol 38, 1025–1034 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ikeda K. et al. Pharmacokinetics of cisplatin in combined cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil therapy: a comparative study of three different schedules of cisplatin administration. Jpn J Clin Oncol 28, 168–175 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bonetti A. et al. Cisplatin pharmacokinetics in elderly patients. Ther Drug Monit 16, 477–482 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Langdon S. P. et al. Characterization and properties of nine human ovarian adenocarcinoma cell lines. Cancer Res 48, 6166–6172 (1988). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cooke S. L. et al. Genomic analysis of genetic heterogeneity and evolution in high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma. Oncogene 29, 4905–4913 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Auguste A. et al. Small Cell Carcinoma of the Ovary, Hypercalcemic Type (SCCOHT) beyond SMARCA4 Mutations: A Comprehensive Genomic Analysis. Cells 9, 1496 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Beaufort C. M. et al. Ovarian cancer cell line panel (OCCP): clinical importance of in vitro morphological subtypes. PLoS One 9, e103988 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Witkowski L. et al. The influence of clinical and genetic factors on patient outcome in small cell carcinoma of the ovary, hypercalcemic type. Gynecol Oncol 141, 454–460 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhou B. et al. Cisplatin-induced CCL5 secretion from CAFs promotes cisplatin-resistance in ovarian cancer via regulation of the STAT3 and PI3K/Akt signaling pathways. Int J Oncol 48, 2087–2097 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bruand M. et al. Cell-autonomous inflammation of BRCA1-deficient ovarian cancers drives both tumor-intrinsic immunoreactivity and immune resistance via STING. Cell Rep 36, 109412 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu W. J., Wang Q., Zhang W. & Li L. [Identification and prognostic value of differentially expressed proteins of patients with platinum resistance epithelial ovarian cancer in serum]. Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi 51, 515–523 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yoshihara M. et al. Ovarian cancer-associated mesothelial cells induce acquired platinum-resistance in peritoneal metastasis via the FN1/Akt signaling pathway. Int J Cancer 146, 2268–2280 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huang G.-X., Qi M.-F., Li X.-L., Tang F. & Zhu L. Involvement of upregulation of fibronectin in the pro-adhesive and pro-survival effects of glucocorticoid on melanoma cells. Mol Med Rep 17, 3380–3387 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gao W., Liu Y., Qin R., Liu D. & Feng Q. Silence of fibronectin 1 increases cisplatin sensitivity of non-small cell lung cancer cell line. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 476, 35–41 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Aggarwal S. et al. Immune modulator CD70 as a potential cisplatin resistance predictive marker in ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol 115, 430–437 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu N., Sheng X., Liu Y., Zhang X. & Yu J. Increased CD70 expression is associated with clinical resistance to cisplatin-based chemotherapy and poor survival in advanced ovarian carcinomas. Onco Targets Ther 6, 615–619 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mustea A. et al. Decreased IL-1 RA concentration in ascites is associated with a significant improvement in overall survival in ovarian cancer. Cytokine 42, 77–84 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Momeny M. et al. Inhibition of bromodomain and extraterminal domain reduces growth and invasive characteristics of chemoresistant ovarian carcinoma cells. Anticancer Drugs 29, 1011–1020 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dong Y.-J., Feng W. & Li Y. HOTTIP-miR-205-ZEB2 Axis Confers Cisplatin Resistance to Ovarian Cancer Cells. Front Cell Dev Biol 9, 707424 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang L.-M., Li M., Tian C.-C., Wang T.-T. & Mi S.-F. CCAAT enhancer binding protein α suppresses proliferation, metastasis, and epithelial-mesenchymal transition of ovarian cancer cells via suppressing the Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Neoplasma 68, 602–612 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Blessing A. M. et al. Elimination of dormant, autophagic ovarian cancer cells and xenografts through enhanced sensitivity to anaplastic lymphoma kinase inhibition. Cancer 126, 3579–3592 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Washington M. N. et al. ARHI (DIRAS3)-mediated autophagy-associated cell death enhances chemosensitivity to cisplatin in ovarian cancer cell lines and xenografts. Cell Death Dis 6, e1836 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ganapathi M. K. et al. Expression profile of COL2A1 and the pseudogene SLC6A10P predicts tumor recurrence in high-grade serous ovarian cancer. Int J Cancer 138, 679–688 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Coscia F. et al. Multi-level Proteomics Identifies CT45 as a Chemosensitivity Mediator and Immunotherapy Target in Ovarian Cancer. Cell 175, 159–170.e16 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.McDermott M. et al. In vitro Development of Chemotherapy and Targeted Therapy Drug-Resistant Cancer Cell Lines: A Practical Guide with Case Studies. Front Oncol 4, 40 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nameki R. A. et al. Rewiring of master transcription factor cistromes during high-grade serous ovarian cancer development. bioRxiv 2023.04.11.536378 (2023) doi: 10.1101/2023.04.11.536378. [DOI]

- 62.Li L., Yang W.-T., Zheng P.-S. & Liu X.-F. SOX17 restrains proliferation and tumor formation by down-regulating activity of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway via trans-suppressing β-catenin in cervical cancer. Cell Death Dis 9, 741 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kuo I.-Y. et al. SOX17 overexpression sensitizes chemoradiation response in esophageal cancer by transcriptional down-regulation of DNA repair and damage response genes. J Biomed Sci 26, 20 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lozano E. et al. MRP3-Mediated Chemoresistance in Cholangiocarcinoma: Target for Chemosensitization Through Restoring SOX17 Expression. Hepatology 72, 949–964 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang Y. et al. SOX17 increases the cisplatin sensitivity of an endometrial cancer cell line. Cancer Cell Int 16, 29 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fang H.-Y. et al. Caspase-14 is an anti-apoptotic protein targeting apoptosis-inducing factor in lung adenocarcinomas. Oncol Rep 26, 359–369 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Corr B. R. et al. Cytokeratin 5-Positive Cells Represent a Therapy Resistant subpopulation in Epithelial Ovarian Cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer 25, 1565–1573 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ricciardelli C. et al. Keratin 5 overexpression is associated with serous ovarian cancer recurrence and chemotherapy resistance. Oncotarget 8, 17819–17832 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Scurr L. L. et al. Ankyrin repeat domain 1, ANKRD1, a novel determinant of cisplatin sensitivity expressed in ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res 14, 6924–6932 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lei Y., Henderson B. R., Emmanuel C., Harnett P. R. & deFazio A. Inhibition of ANKRD1 sensitizes human ovarian cancer cells to endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis. Oncogene 34, 485–495 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Solár P. & Sytkowski A. J. Differentially expressed genes associated with cisplatin resistance in human ovarian adenocarcinoma cell line A2780. Cancer Lett 309, 11–18 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mariya T. et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-10 regulates stemness of ovarian cancer stem-like cells by activation of canonical Wnt signaling and can be a target of chemotherapy-resistant ovarian cancer. Oncotarget 7, 26806–26822 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Latifi A. et al. Cisplatin treatment of primary and metastatic epithelial ovarian carcinomas generates residual cells with mesenchymal stem cell-like profile. J Cell Biochem 112, 2850–2864 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tayama S. et al. The impact of EpCAM expression on response to chemotherapy and clinical outcomes in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer. Oncotarget 8, 44312–44325 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Iżycka N. et al. Cancer Stem Cell Markers-Clinical Relevance and Prognostic Value in High-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer (HGSOC) Based on The Cancer Genome Atlas Analysis. Int J Mol Sci 24, 12746 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tu B. et al. Mesenchymal stem cells promote osteosarcoma cell survival and drug resistance through activation of STAT3. Oncotarget 7, 48296–48308 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Han X.-G. et al. TIMP3 Overexpression Improves the Sensitivity of Osteosarcoma to Cisplatin by Reducing IL-6 Production. Front Genet 9, 135 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wang Y. et al. Autocrine production of interleukin-6 confers cisplatin and paclitaxel resistance in ovarian cancer cells. Cancer Lett 295, 110–123 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gao J., Zhao S. & Halstensen T. S. Increased interleukin-6 expression is associated with poor prognosis and acquired cisplatin resistance in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oncol Rep 35, 3265–3274 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Duan S. et al. IL-6 signaling contributes to cisplatin resistance in non-small cell lung cancer via the up-regulation of anti-apoptotic and DNA repair associated molecules. Oncotarget 6, 27651–27660 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lund R. J. et al. DNA methylation and Transcriptome Changes Associated with Cisplatin Resistance in Ovarian Cancer. Sci Rep 7, 1469 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Xu S. et al. IL-6 promotes nuclear translocation of HIF-1α to aggravate chemoresistance of ovarian cancer cells. Eur J Pharmacol 894, 173817 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cohen S. et al. Platinum-resistance in ovarian cancer cells is mediated by IL-6 secretion via the increased expression of its target cIAP-2. J Mol Med (Berl) 91, 357–368 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hahne J. C. et al. Immune escape of AKT overexpressing ovarian cancer cells. Int J Oncol 42, 1630–1635 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Barghout S. H. et al. RUNX3 contributes to carboplatin resistance in epithelial ovarian cancer cells. Gynecologic Oncology 138, 647–655 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Dai J.-M. et al. Cancer-associated fibroblasts contribute to cancer metastasis and apoptosis resistance in human ovarian cancer via paracrine SDF-1α. Clin Transl Oncol 25, 1606–1616 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zhang F. et al. Cancer-associated fibroblasts induce epithelial-mesenchymal transition and cisplatin resistance in ovarian cancer via CXCL12/CXCR4 axis. Future Oncol 16, 2619–2633 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wang M. et al. CXCL12 suppresses cisplatin-induced apoptosis through activation of JAK2/STAT3 signaling in human non-small-cell lung cancer cells. Onco Targets Ther 10, 3215–3224 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zhou W. et al. Autocrine activation of JAK2 by IL-11 promotes platinum drug resistance. Oncogene 37, 3981–3997 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lee H. et al. Poziotinib suppresses ovarian cancer stem cell growth via inhibition of HER4-mediated STAT5 pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 526, 158–164 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Jinawath N. et al. Oncoproteomic analysis reveals co-upregulation of RELA and STAT5 in carboplatin resistant ovarian carcinoma. PLoS One 5, e11198 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Saglam O. et al. ERBB4 Expression in Ovarian Serous Carcinoma Resistant to Platinum-Based Therapy. Cancer Control 24, 89–95 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Casagrande N. et al. In Ovarian Cancer Multicellular Spheroids, Platelet Releasate Promotes Growth, Expansion of ALDH+ and CD133+ Cancer Stem Cells, and Protection against the Cytotoxic Effects of Cisplatin, Carboplatin and Paclitaxel. Int J Mol Sci 22, 3019 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kim A. et al. Enhanced expression of Annexin A4 in clear cell carcinoma of the ovary and its association with chemoresistance to carboplatin. Int J Cancer 125, 2316–2322 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Mogami T. et al. Annexin A4 is involved in proliferation, chemo-resistance and migration and invasion in ovarian clear cell adenocarcinoma cells. PLoS One 8, e80359 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]